FEATURING 304 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

FEATURING 304 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

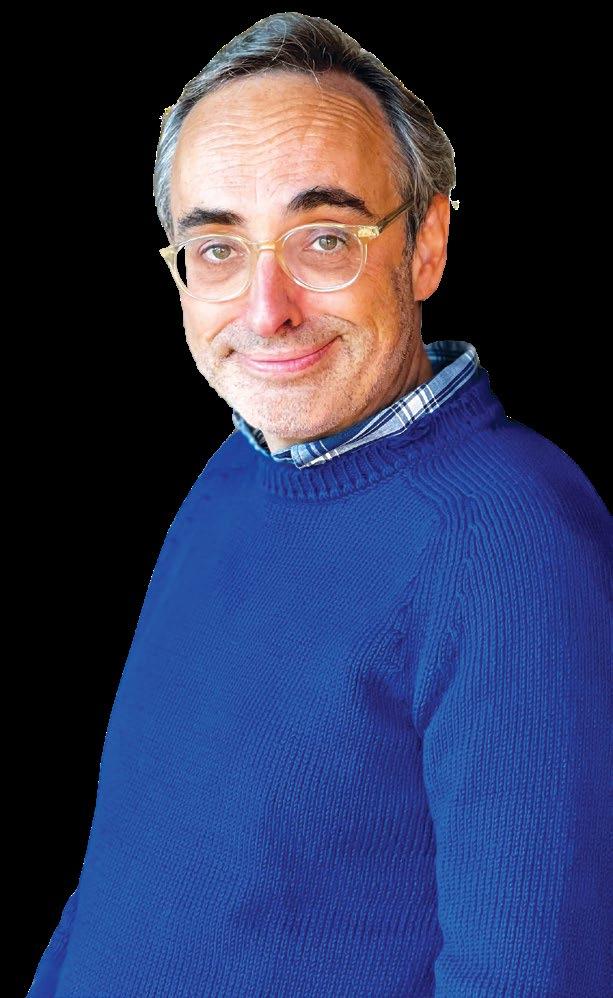

The author reflects on his new novel, Vera, or Faith, and a long career

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

HUMOR GETS NO RESPECT.

Funny novels aren’t easy to write— you try keeping the jokes coming for a few hundred pages—but when they succeed, they give readers unrivaled delight. Occasionally, awards juries surprise everybody and reward such books: Paul Beatty’s provocative satire about race in America, The Sellout, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction 2016, and in 2018, Andrew Sean Greer took home a Pulitzer Prize for Less, about a midlist gay novelist having a midlife crisis. More often these books are championed by booksellers and book clubs, passed from hand to hand by passionate readers in the know.

Gary Shteyngart, who appears on the cover of this issue, has been writing funny novels (and one uproarious

memoir) since The Russian Debutante’s Handbook in 2001. His latest is Vera, or Faith (Random House, July 8), narrated by a precocious 10-year-old whose observations of the dysfunctional adult world around her are both comic and touching. Shteyngart’s best-known novel, Super Sad True Love Story (2010), took home the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize, a U.K. award given to a book that’s “captured the comic spirit of P.G. Wodehouse.” In that madcap vein, the winner receives a jeroboam of champagne, a set of books by Wodehouse, and a Gloucestershire Old Spot pig named for the winning book. Just Google “Gary Shteyngart pig.”

Six of Shteyngart’s seven books to date have received Kirkus stars (pigs not

Frequently Asked Questions: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/faq

Fully Booked Podcast: www.kirkusreviews.com/podcast/

Advertising Opportunities: www.kirkusreviews.com/book-marketing

Submission Guidelines: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/publisher-submission-guidelines

Subscriptions: www.kirkusreviews.com/magazine/subscription

Newsletters: www.kirkusreviews.com

For customer service or subscription questions, please call 1-800-316-9361

included)—a pretty good track record. On page 16, he reflects on his career with contributor Marion Winik and teases some upcoming projects. Until his next book comes along, here are some recent comic novels that will keep readers laughing.

Blob: A Love Story by Maggie Su (Harper/ HarperCollins, January 28): The premise of this debut novel tells you all you need to know: A college dropout on the rebound from a failed relationship finds a pile of goop in the alley behind a bar, brings it home to her apartment, and discovers that it’s sentient. Why can’t it be molded into the perfect boyfriend? Our reviewer calls it a “funny, tender, unexpected— though somewhat flimsy—bildungsroman.”

Sky Daddy by Kate Folk (Random House, April 8): If romance with a sentient blob isn’t bizarre enough for you, the narrator of this first novel (“Call me Linda,” she begins) loves airplanes. I mean really loves airplanes—longing for “whichever plane would

finally recognize my worth and claim me as his bride in orgasmic catastrophe”— what regular folks “‘vulgarly’ refer to as a ‘plane crash.’” Our starred review calls it an “utterly confident and endearing portrait of a woman unlike anyone readers have met before.”

The Greatest Possible Good by Ben Brooks (Avid Reader Press, July 15): As this dryly funny novel opens, the lives of the Candlewicks are about to go pear-shaped. A package addressed to 15-year-old Emil is discovered to contain LSD and MMDA, while 17-year-old Evangeline, deep in a book about “effective altruism,” finds her well-off parents falling short. Then dad Arthur imbibes the drugs, reads the book, and decides to give away their fortune—much to the dismay of all concerned. “The pleasures of this novel’s writing, characters, and plot are fully equal to its good intentions,” according to our starred review.

ISBN: XXX-X-XX-XXXXXX-X

Co-Chairman

HERBERT SIMON

Publisher & CEO

MEG LABORDE KUEHN mkuehn@kirkus.com

Chief Marketing Officer

SARAH KALINA skalina@kirkus.com

Publisher Advertising & Promotions

RACHEL WEASE rwease@kirkus.com

Indie Advertising & Promotions

AMY BAIRD abaird@kirkus.com

Author Consultant

KEELIN FERDINANDSEN kferdinandsen@kirkus.com

Lead Designer KY NOVAK knovak@kirkus.com

Magazine Compositor

NIKKI RICHARDSON nrichardson@kirkus.com

Director of Kirkus Editorial ROBIN O’DELL rodell@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor

MARINNA CASTILLEJA mcastilleja@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Production Editor

ASHLEY LITTLE alittle@kirkus.com

Copy Editors

ELIZABETH J. ASBORNO

LORENA CAMPES

NANCY MANDEL

BILL SIEVER

Mysteries Editor

THOMAS LEITCH

Co-Chairman

MARC WINKELMAN

Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER tbeer@kirkus.com

President of Kirkus Indie

CHAYA SCHECHNER cschechner@kirkus.com

Fiction Editor

LAURIE MUCHNICK lmuchnick@kirkus.com

Nonfiction Editor

JOHN McMURTRIE jmcmurtrie@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

LAURA SIMEON lsimeon@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

MAHNAZ DAR mdar@kirkus.com

Editor at Large

MEGAN LABRISE mlabrise@kirkus.com

Senior Indie Editor

DAVID RAPP drapp@kirkus.com

Indie Editor

ARTHUR SMITH asmith@kirkus.com

Senior Editorial Assistant

NINA PALATTELLA npalattella@kirkus.com

Senior Indie Editorial Assistant

DAN NOLAN dnolan@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant

KATARINA YERGER kyerger@kirkus.com

Contributing Writers

GREGORY McNAMEE

MICHAEL SCHAUB

Contributors

Nada Abdelrahim, Colleen Abel, Jill Adams, Mahasin Aleem, Reina Luz Alegre, Jeffrey Alford, Autumn Allen, Paul Allen, Jenny Arch, Kent Armstrong, Mark Athitakis, Kit Ballenger, Audrey Barbakoff, Carole Bell, Nell Beram, Elizabeth Bird, Ariel Birdoff, Christopher A. Biss-Brown, Elissa Bongiorno, Sally Brander, Jessica Hoptay Brown, Kevin Canfield, Tobias Carroll, Sonia Charales, Alec B. Chunn, Amanda Chuong, Adeisa Cooper, Jeannie Coutant, Kim Dare, Michael Deagler, Cathy DeCampli, Dave DeChristopher, Elise DeGuiseppi, Suji DeHart, Lisa Dennis, Amanda Diehl, Anna Drake, Robert Duxbury, Jacob Edwards, Gina Elbert, Elaine Elinson, Lisa Elliott, Lily Emerick, Chelsea Ennen, Brooke Faulkner, Eiyana Favers, Rodney Fierce, Katie Flanagan, Catherine Foster, Cynthia Fox, Mia Franz, Ayn Reyes Frazee, Jenna Friebel, Jackie Friedland, Roberto Friedman, Omar Gallaga, Jackie Garcia, Laurel Gardner, Cierra Gathers, Sydney Geyer, Chloé Harper Gold, Carol Goldman, Emily A. Gordon, Michael Griffith, Vicky Gudelot, Sean Hammer, Peter Heck, Ralph Heibutzki, Mara Henderson, Shannan Hicks, Loren Hinton, Zoe Holland, Natalia Holtzman, Abigail Hsu, Kathleen T. Isaacs, Darlene Ivy, Matt Jakubowski, Jayashree Kamblé, Deborah Kaplan, Marcelle Karp, Lavanya Karthik, Ivan Kenneally, Colleen King, Katherine King, Priti Krishtel, Susan Kusel, Christopher Lassen, Tom Lavoie, Judith Leitch, Seth Lerer, Elsbeth Lindner, Corrie Locke-Hardy, Barbara London, Patricia Lothrop, Sawyer Lovett, Georgia Lowe, Wendy Lukehart, Michael Magras, Joan Malewitz, Mitu Malhotra, Thomas Maluck, Michelle H Martin, Gabriela Martins, J. Alejandro Mazariegos, Zoe McLaughlin, Don McLeese, Cari Meister, Carol Memmott, Clayton Moore, Andrea Moran, Gary Moskowitz, Molly Muldoon, Liza Nelson, Randall Nichols, Dan Nolan, Tori Ann Ogawa, Hannah Onstad, Mike Oppenheim, Nick Owchar, Emilia Packard, Andrea Page, Nina Palattella, Hal Patnott, Bethanne Patrick, Deb Paulson, Tara Peck, Alea Perez, John Edward Peters, Jim Piechota, Christofer Pierson, Shira Pilarski, Cathy Poland, Margaret Quamme, Carolyn Quimby, Kristy Raffensberger, Matt Rauscher, , Stephanie Reents, Sarah Rettger, Nancy Thalia Reynolds, Jasmine Riel, Amy Robinson, Lizzie Rogers, Soumi Roy, Lloyd Sachs, Bob Sanchez, Julia Sangha, Caitlin Savage, Gretchen Schulz, Jerome Shea, Madeline Shellhouse, Linda Simon, Laurie Skinner, Leena Soman, Margot E. Spangenberg, Andria Spencer, Allison Staley, Daneet Steffens, Mathangi Subramanian, Deborah Taylor, Ella Teevan, Lenora Todaro, David L. Ulin, Bijal Vachharajani, Francesca Vultaggio, Audrey Weinbrecht, Kimberly Whitmer, Wilda Williams, Vanessa Willoughby, John Wilwol, Marion Winik, Adam Winograd, Jean-Louise Zancanella

WITH SUMMER REACHING its peak, maybe what you need is a short book— something you can read in a weekend or even a long, languorous day—to give you a feeling of accomplishment. A sense of humor would help, too. Here are a few suggestions.

Bring the House Down by Charlotte Runcie (Doubleday, July 8): Set in Edinburgh during the annual arts festival, Runcie’s novel centers on a negative review—so maybe I’m the target audience? When Alex Lyons writes a scathing takedown of a one-woman show, he doesn’t think twice about sleeping with the performer, whom he meets in a bar later that night. Of course,

she hasn’t read the review yet, and once she does, she’ll rename her show The Alex Lyons Experience and devote herself to taking him down. But there’s much more to the book than that, and “the clarity of Runcie’s narration and her ability to consider both sides of an argument…[make] for an unusual, thought-provoking, multilayered read.”

Vera, or Faith by Gary Shteyngart (Random House, July 8): Vera Bradford- Shmulkin is an intensely smart 10-year-old with a Russian Jewish immigrant father, a New England WASP stepmother, a long-gone Korean mother, and an anxious need to hold her family together. The book is set in a

near-future where a proposed constitutional amendment would give an “enhanced vote” to “those who landed on the shores of our continent before or during the Revolutionary War but were exceptional enough not to arrive in chains.” Our starred review says that “Shteyngart is doing his most important work ever, illuminating the current tragedy with humor, smarts, and heart.” (Read our interview with the author on p. 16.)

Maggie; or, a Man and a Woman Walk Into a Bar, by Katie Yee (Summit, July 22): The narrator and her husband have two young children, so she’s excited when he suggests they get a babysitter and go out for dinner at an all-you-can-eat Indian buffet. But then he tells her he’s having an affair, and a few days later,

she’s diagnosed with breast cancer. In between she tries to console herself by listing everything she finds annoying about her husband (“If he’s not in his work button-downs, he’s always wearing his Ivy League college sweatshirt”) and trying to make her kids think she’s funnier than he is. “The comedy here is never dark or desperate or manic,” our starred review says. “Instead, the narrator’s dignity and strength make this a novel that crackles with heartfelt intelligence and wit.”

An Oral History of Atlantis by Ed Park (Random House, July 29): This collection of short stories by Pulitzer finalist Park plays literary games with password prompts (“First time you had sex and did it count”), DVD bonus commentary, and other minutiae of contemporary life. “But Park isn’t just playing with unusual premises for their own sake,” according to our review.

“He’s looking for the ways that human idiosyncrasies manage to poke up to the surface even while technology tries to keep us tidy and algorithm friendly….A collection that revels in its quirks, smart and sensitive in equal measure.”

Laurie Muchnick is the fiction editor.

Two young Indian writers discover their conjoined destinies by leaving home, coming back, connecting, disconnecting, and swimming in the ocean at Goa. Sonia’s grandfather, the lawyer, and his friend, the Colonel, are connected by a weekly chess game and a local tradition of families sharing food, “paraded through the neighborhood in tiffin carriers, in thermos flasks, upon plates covered in napkins tied in rabbit ears.” Shortly after Desai’s magnificent third novel opens, the two families are also connected by a marriage proposal. Upon hearing that Sonia is feeling lonely at college in Vermont— loneliness? Is there anything more un-Indian?—and unaware that she is romantically involved with a much older, very famous painter, her elders deliver a hilariously

lukewarm letter proposing that she be introduced to Sonny, the Colonel’s grandson. Sonny is living in New York working as a copy editor at The Associated Press, and he, too, has a partner no one knows about. Sonny’s family feels they are being asked to give up their son to balance out some long-ago bad investment advice from the Colonel; on the other hand, they would very much like to get the other family’s kebab recipe. The fate of this half-hearted arranged marriage unfurls over many years and almost 700 delicious pages that the author has apparently been working on since the publication of The Inheritance of Loss (2006), which won the Booker Prize and National Book Critics Circle Award. You can almost feel the decades passing as the novel becomes increasingly

concerned with the process of novel-writing; toward the end, Sonia can’t stop thinking about whether, if she writes all the stories she knows, “these stories [would] intersect and make a book? How would they hold together?” Desai’s trust in her own process pays off, as vignettes of just a page or two (Sonia’s headspinning tour of a museum with the great artist; Sonny’s

lightning-strike theory that only people who have cleaned their own toilet can appreciate reading novels) intersect with the novel’s central obsessions—love, family, writing, the role of the U.S. in the Indian imagination, the dangers faced by a woman on her own—and come to a perfectly satisfying close. A masterpiece.

Residents of a dingy apartment building grapple with the meaning of life.

Ackerman, Elliot | Knopf (304 pp.) $29 | August 5, 2025 | 9780593803851

Sheepdogs boost a jet in the service of America’s off-thebooks armies. What’s in a name? asked Shakespeare. Quite a bit, apparently. Take sheepdogs, for example. As a man named Cheese explains to his wife, there are three types of people in the world: sheep, who don’t believe in evil; wolves, who prey upon them, and sheepdogs, who “understand violence, except they use that understanding to protect others.” He’s a sheepdog: an Afghan and a skilled pilot who works for a shadowy organization known as the Office and hopes to settle with his pregnant wife in America. He partners with Skwerl, an ex-Marine whose name would be Squirrel except that “Marines can’t spell for shit.” Nicknames are all assigned to them, and their real names don’t much matter anyway. The capital S Sheepdog hires them to go to Uganda and repossess—or steal, depending on one’s viewpoint—a Challenger 600 luxury jet and fly it to Marseille in exchange for a $1 million commission. Strangely, the main characters don’t know Sheepdog’s identity. Plenty of action ensues, of course, but the story is more caper than thriller, and protecting innocent lambs hardly seems the main thrust here. Don’t expect lots of gore or high body counts, even though the Russia-Ukraine war lurks in the background. A grizzly bear, a dominatrix named Mistress S, and a set of

plates commissioned by Marie Antoinette keep the tone relatively light. Those fancy plates might be worth more than the plane even after they’ve broken a few, but not everyone is motivated by money. All Cheese really wants is not to have to work at the Esso station anymore. All that Ali Safi wants is to find the man responsible for his brother’s death. There are vivid images: “Just Shane” comes out of a shower wearing just a towel and a ski mask; Mistress S has tattoos on her wrist that record— ahem— how far she’s gone with clients. Author Ackerman is a skilled storyteller, weaving an unlikely set of details and making them look like they belong together. Compare this to the deadly serious 2034, which he co-authored with Admiral James Stavridis in 2021. A fun read, loony in spots.

Kirkus Star

Adrian, Emily | Little, Brown (224 pp.) $28 | August 12, 2025 | 9780316584517

A pretentious academic couple engenders the wrath of a jealous grad student at an elite college in upstate New York. This terrifically inventive matryoshka doll of a novel opens with a title page indicating we are reading the thesis project of Roberta Green, MFA candidate. Yet the narrative blending that follows is so layered that even by the end it begs an unraveling of which fiction is which. The outline is simple: Simone is an

anomaly—a glamorous academic—and happily married to Ethan, a fellow English professor. Though Ethan worships his wife, he has a fling with the rumpled Abigail, the department’s secretary. Meanwhile, Simone is having an emotional entanglement with grad student Roberta. As her advisor, Simone should be guiding Roberta on this MFA project we are reading, but instead they are training for a marathon and wandering around Simone and Ethan’s house in states of sweaty undress. When Simone discovers Ethan’s affair, the couple embarks on an impromptu cross-country journey. The work has two remarkably distinct registers: It’s a tender portrait of an enviable marriage balanced by a delightfully smarmy tone with laugh-out-loud passages of humor. As Roberta dates a girl on campus while fantasizing about Simone and the revenge she will be taking in the form of this novel, Ethan and Simone are left wondering what their marriage means. But what is the truth? A novel that makes authorial control so visible— Roberta’s comically biased character portraits; the midpage shifting between third- and first-person narration; the conclusion rewritten to first reflect Roberta’s fantasy and then the “reality”—could have left the whole enterprise as simply a jewel to be admired. Happily, it is all much more than a Borgesian experiment: It is a finely observed work on love. A masterful exploration on the varieties of truth, and the stories we craft about ourselves.

Aeschbacher, Tobias | Trans. by Andrew Shields | Helvetiq (128 pp.) | $24.95 June 3, 2025 | 9783039640874

Residents of a dingy apartment building grapple with the meaning of life as violence unfolds in this pulpy noir tale. A family urn is stolen and three armed gangsters set off to retrieve it.

They trace the urn back to two thieves who live in a three-story, six-unit apartment building in a small town, but complications quickly arise, and what could have been a simple task quickly spirals out of control. As they drive into town, the three armed men should be organizing their strategy, going over their plan to get the urn back. But instead they argue about trivial things: Why would you name your gun after your first girlfriend? Why does the youngest of the three always have to sit in the back seat like a child? Violence is coming, but they’re blissfully distracted by completely irrelevant side topics. The distractions continue as they enter the building. Each resident they encounter steers them away from their task by posing simple yet existential questions like: What is good and what is evil? When bad decisions are made, who deserves to die? When is it okay to end a life? What does it mean to be a good neighbor? As the gangsters and tenants debate these issues, bullets quickly start to fly and the blood flows. Everyone in the apartment building finds themselves on one end of a gun barrel. And before the triggers get pulled, each person reckons with essential notions of fairness, righteousness, and loneliness. Aeschbacher draws the story like a modern-day Adventures of Tintin, with scrappy, hand-drawn lines; subdued shades of mahogany and aubergine maintain the deadpan gloom of the tale. He takes a Richard Scarry approach to detail: His sketches of the apartment building include small elements of ceilings and furniture that fill each panel. There are no new beginnings for the people in the apartment building. Death—and perhaps a brief moment of enlightenment—beckons for them all.

A comic—and esoteric—gangster story, full of bad choices and inevitable violence.

Appelbaum, Lauren | Forever (352 pp.) | $17.99 paper September 16, 2025 | 9781538757864

An unexpected inheritance invites a reluctant heroine to step out of her shell. At her grandmother Lottie’s funeral, sad and sticky in the Florida heat, Mallory Rosen can’t wait to get back to her comfortable and very routine life in Seattle. But shortly after she returns, she learns that Lottie willed Mallory a house in Reina Beach along with a request to look after Gramps, now alone in an independent living community. Mallory is avoidant and at first tries to handle property ownership and grandparent connection long distance, but a friend talks sense into her, convincing her to appear in person. A few days turns into a week, then longer, as she builds a sweet relationship with the delightful and believable Gramps and a potentially steamy one with her property manager, Daniel. Given how small she has kept herself and her life in Seattle, Mallory is surprisingly game to meet new people and try new things—shuffleboard, kayaking, an exercise class with the retirees that is quite funny. She even, after a bit of resistance, proves a dab hand at home improvement. So it’s slightly mystifying why she seems so dedicated to returning to the Pacific Northwest. Nonetheless, the slow burn of her falling for Daniel as well as Florida is full of lush and lovely scenes, and

Mallory is a pleasurable narrator who readers will root for.

Like a good soak in a hot tub near the beach.

Kirkus Star

Banville, John | Knopf (320 pp.) | $30 October 7, 2025 | 9780593801161

A trip to Venice takes a dark turn for a British writer and his American wife. Evelyn Dolman introduces himself to the readers of Banville’s latest, set in the late Victorian era, as “a man of letters,” initially hoping for a career that will cement him as “a lord of language,” regarded more highly than Tolstoy and Shakespeare. Alas, the Briton has become a mere “Grub Street hack,” with one bright spot in his life: He has recently married Laura Rensselaer, the daughter of an American oil magnate who has hired Evelyn to write his biography. After Laura’s father dies in a riding accident, Evelyn learns that she was disinherited, and he and his bride go to Venice so that she might recover from her loss. Shortly after arriving at an apartment in the city, Evelyn, at Laura’s suggestion, pays a visit to a cafe, where he runs into a man named Freddie, who claims to have been a schoolmate of Evelyn’s. Evelyn is skeptical, but his doubts are cast aside when he meets Freddie’s beautiful sister, Francesca, with whom he is instantly taken. Evelyn returns to the apartment, drunk, and sexually assaults his wife;

An inheritance invites a reluctant heroine to step out of her shell. AN INTROVERT’S GUIDE TO LIFE AND LOVE

the two had seldom been intimate before, and Evelyn regards the attack as an act of revenge. The next morning, Laura is gone, and Evelyn suspects he’s either losing his mind or the victim of a mysterious scam: “Everything was a puzzle, everything a trap set to mystify and hinder me.” Banville once again proves himself a master of suspense, and he captures a noir version of Venice perfectly. Evelyn is a fascinating character: monstrous, certainly, but is he really being manipulated? Is he manipulating the reader? It’s an open question, and a testament to Banville’s considerable skill as a storyteller. Dark, twisty, and consistently smart: vintage Banville.

Bowen, Rhys | Lake Union Publishing (399 pp.)

$28.99 | August 5, 2025 | 9781662527180

As the winds of war blow over Europe, an English woman embarks on a nostalgic trip to the French Riviera.

Ellie Endicott, who has two grown sons she rarely sees, has spent her entire married life catering to the needs of her husband, a pompous banker. So she’s flabbergasted when Lionel tells her he wants a divorce. Now that he’s met a younger woman he wants to marry, he thinks he can bulldoze Ellie into a settlement favorable to him. Standing up for herself, she obtains a fair settlement, plans a trip to France, and encourages Mavis Moss, the cleaning lady whose husband beats her, to come along. They’re joined by Miss Smith-Humphries, a pillar of the community, who’s dying and wants to revisit the happy places of her youth. Taking Lionel’s Bentley, they set off for France. Ellie’s fluent French proves especially useful when, while stopping for gas, they rescue Yvette, a pregnant girl who claims she’s being kidnapped. Forced to stop in the tiny seaside village of Saint-Benet when the Bentley

develops problems, they stay at Pension Victoria, which is owned by an English couple. They’re aided by handyman Louis and Nico, a mysterious, roughly attractive fisherman, and welcomed by other villagers and a resident gay English couple. Ellie is so intrigued by the shabby, mysterious Villa Gloriosa that she asks the owner to rent it to her. After much work, they’re ready to move in. When Yvette leaves with her baby, she takes some of their jewelry. In general, though, they enjoy several halcyon years until eventually the Nazis descend on the village. Can they survive and keep the dangerous secrets threatening members of the community hidden? A delightful story of a heroine whose inner strength triumphs over adversity.

Boyne, John | Henry Holt (496 pp.) | $29.99 September 9, 2025 | 9781250410368

Boyne’s ambitious novel powerfully explores the devastation of sexual abuse from four different perspectives.

“The elements— water, earth, fire, air—are our greatest friends, our animators. They feed us, warm us, give us life, and yet conspire to kill us at every juncture,” says Vanessa Carvin, who has fled to a remote island off the west coast of Ireland in the wake of a sex abuse scandal that led to her husband’s imprisonment, her alienation from her daughter, and public condemnation. Troubled Evan Keough, with his mother’s help, escapes this same island in the hopes of making a new life as a painter in England but instead finds himself on trial as an accomplice in the rape of a young woman. A juror on that trial, Dr. Freya Petrus, is a successful burn surgeon who deals with her childhood trauma by inflicting her pain on new victims. And her former resident–turned–child psychologist, Aaron Umber, seeks to heal his own damaged psyche by embarking on a life-changing journey back to Ireland

with his teenage son. Originally published in the U.K. as separate novellas (Water, Earth, Fire, Air), these four interconnected stories pack a wallop when combined in one volume. If the format at times feels too tidy and contrived (especially in the final section), it doesn’t lessen the emotional impact of deeply wounded characters struggling to overcome their guilt and find redemption in the wake of catastrophic trauma. Book clubs will find plenty to discuss in this meaty and challenging read.

Chaon, Dan | Henry Holt (288 pp.) | $28.99 September 23, 2025 | 9781250175236

Twin siblings run off to join the circus, which proves to be a dark carnival indeed. Bolt and Eleanor, the teenage twins at the center of Chaon’s brilliant fifth novel, are orphans who’ve fallen under the watch of “Uncle Charlie,” a con man and serial killer. They escape Charlie’s clutches with the assistance of a mysterious Mr. Jengling, who operates a circus and recruits them for his sideshow—which includes a strongwoman, dog-faced boy, and, most creepily, Rosalie, a woman with a second head growing out of the side of her neck and who can predict how and when you will die. For all that darkness, the brother and sister find a welcoming ersatz family; interstitial chapters explore the background of each performer and the unique talents Jengling detected in them. (Bolt and Eleanor’s own talents—telepathy and telekinesis—are only just emerging.) Chaon is focused on how we find our identities outside the ones the world wants to apply to us; as the title suggests, Chaon takes inspiration from Tod Browning’s 1932 film, Freaks, in which the sideshow performers chant

“one of us” as a sign of acceptance. Meanwhile, Chaon has also delivered a sharp thriller, as Uncle Charlie attempts to chase down the twins, leaving a bloody path along the way. Set mainly in 1915, the novel captures a vanished vaudeville world that Chaon resurrects in thoughtful detail, down to the era’s slang (ziggety, conflustered, woofits). But in its latter chapters, the novel is also powerfully otherworldly, deliberately warping assumptions about life, death, and the nature of souls. Bolt and Eleanor take divergent paths once they’ve joined the circus, but Chaon suggests that any path rooted in consideration of others is a valid one. A magic trick: a novel that’s both deeply unsettling and tenderhearted.

Kirkus Star

Chou, Elaine Hsieh | Penguin Press (352 pp.) $29 | August 19, 2025 | 9780593298381

A clutch of stories that starkly question assumptions about our identities.

Chou’s debut collection—following the novel Disorientation (2022)—is built on premises where characters’ sense of self is rattled. In “Carrot Legs,” a young woman discovers that her family tree doesn’t branch in ways she was raised to believe. In “Featured Background,” a man is determined to connect with his estranged daughter, an acclaimed movie director, by taking on an actor’s persona. “Happy Endings” imagines a future where sex work is outsourced to technology, with hellish consequences for one john. Chou is gifted at storytelling with a surrealistic bent: “The Dollhouse” plays with Barbie tropes, zooming into the plastic world of toys and back out into reality to expose how women are objectified, while “You Put a Rabbit on Me” is a variation on a doppelgänger story, as a

A magic trick: a novel that’s both deeply unsettling and tenderhearted.

ONE

US

young woman in France working as an au pair meets a woman bearing an unsettling resemblance to her. Chou can play these premises for laughs: “Mail Order Love®” turns on a man who’s disappointed with the purchase of the title. Is his new wife glitching, or just in possession of an independent mind, and how has technology fuzzed the line between the two? The closing novella, “Casualties of Art,” at first seems straightforward, almost blandly conventional—its setup involves four artists at a retreat and their flirtatious hothouse relationships. But Chou uses her lead character to play with the meaning of autofiction and the way we rewrite history to serve our most self-flattering images. The collection’s title is a classic microaggression—a way to box people as foreign or other. Nobody in the book actually utters the question, but throughout Chou cleverly exposes just how difficult humanity is to simplify, whatever our provenance. Sharp storytelling that bends and blurs genre expectations.

Church, Wendy | Severn House (256 pp.)

$29.99 | August 5, 2025 | 9781448315659

Murder is the least of the disruptions in Jesse O’Hara’s latest barnstormer. Giving a presentation at the International Conference on Law Enforcement and Investigation isn’t a first choice for Jesse, a forensic accountant with a “million-dollar brain and ten-cent personality.” But the scenic

location is certainly an enticement. So is her growing certainty that her mortal enemy Svetlana Ivashchenko, the ruthless head of Rusgaprom, knows that she’s been staying with her best friend, Salbatore “Sam” Hernandez, and could strike at any moment. So Jesse, Sam, and their partner, computer nerd Gideon Spielberg, take off for Greece, where they’re recruited by Eleftherios Karadimitropoulos, head of Special Projects for the Ministry of Citizen Protection, for a routine job that quickly morphs into another job, then another and another. The escalating stakes will draw Jesse—or Dr. O’Hara, as she’s constantly introducing herself—into an uncomfortably extended face-off with Platon, head of the antigovernment group the Megali Titans, who whisks Gideon away, summons Jesse and Sam to his hushhush retreat, and suavely forces them to break his valued associate Apollo out of a Turkish prison. The biggest treat here is Jesse’s yadda-yadda first-person voice as she reacts with impatience and annoyance but never fear to the bombing of her hotel, the improbable plot to rescue Apollo, the ritualistic juggling of allegiances, and the repeated return from the shadows of Svetlana and Jesse’s own father, whom she’s tuned out ever since his drunk driving killed her mother. So there’s no downtime, just one jolt after another, including a couple of murders, until readers are likely to feel just as overstimulated as the heroine. Part battle to the death, part tour guide.

A contemplative study of colonialism’s collapse, and its enduring legacy.

THE CARTOGRAPHER OF ABSENCES

Cook, Jeannine A. | Amistad/ HarperCollins (256 pp.) | $25

September 23, 2025 | 9780063430952

In this bildungsroman of middle age, an aspiring bookseller wrestles her fears for love and professional fulfillment. The aspiring Philadelphia bookstore proprietor at the center of this dreamily lyrical debut struggles with a phobia of touch that has long stymied her deepest desires. As the 40-year-old heroine—known only as “The Shopkeeper” for most of the novel—confesses to her writing-group classmates, she has never been kissed. And she’d like to change that. But more pressingly, the Shopkeeper—like the author, who is the proprietor of the real Harriett’s Bookshop in Philadelphia—is on the verge of fulfilling a lifelong dream of opening a bookstore named after her guide and inspiration, the legendary abolitionist and freedom fighter Harriet Tubman. But a shopkeeper who can’t come near her customers for fear of passing out is at a disadvantage. Since childhood, the Shopkeeper’s condition—haphephobia—has been so severe that a simple touch can cause her to feel a shock of electricity and lose consciousness. So she’s lived in her head, taking refuge in books—so much so that at times it’s hard for her (and for the reader) to distinguish what’s really happening from imagination. Now though, on the cusp of a new year, the Shopkeeper is determined; she has “declared this her year to conquer fear” and finally

open the doors of the store. Joining that purposeful writing group “designed to help slowly bring trauma to the surface in a controlled manner” is part of the plan. Falling for a mysterious bearded man who says he, too, can’t be touched because he’s in training to be a monk is not. But he keeps popping up like magic. With his help and that of family and friends, change is finally within reach. Romance is only part of the payoff in this quirky yet humane story of a lonely shopkeeper conquering her fears.

Cosby, S.A. | Flatiron Books (352 pp.) $25.99 | June 10, 2025 | 9781250832061

Deadly trouble awaits Roman Carruthers in his corrupt hometown when the Black wealth management whiz attempts to outwit a murderous drug gang threatening his family.

The Atlanta-based Roman’s weakwilled, strung out younger brother, Dante, and an ill-fated crony have incurred a sizable drug debt by consuming rather than dealing most of the Molly and heroin they obtained from the notorious Black Baron Boys. Led by the ruthless Torrent and his cooler-tempered sibling, Tranquil, the BBB have expressed their displeasure with Dante by running his father, founder of a family-run crematorium, off the road, leaving him in a coma. Having never encountered a situation he couldn’t wheel and deal his

way out of, the self-regarding Roman offers to cover the debt and much more by reinvesting the BBB’s money. Their immediate answer is to knock his teeth out. But with visions of using the crematorium (Dante’s inferno?) to burn up their victims, they go along with him—to a point. Roman, like his brother and sister, Neveah, is haunted by the disappearance of their mother when they were teens. To expiate his pain, he visits a dominatrix while Neveah—who increasingly believes rumors that her jealous father did her mother in—sleeps with a crooked cop. In making the transition from slick operator to coldblooded instigator of violence himself, Roman becomes the latest in a long line of fictional Southerners to strike a deal with the devil (as in the film Sinners, fire plays a big role). The plot sometimes wobbles—Roman pursues an unlikely romance with Torrent’s smart and warmly appealing half sister. But Cosby keeps things tense, making great use of the crematorium and freshening the genre with lofty philosophizing: “To Roman, it felt like life, existence, was a stygian wheel that had spun on a bitter axis.” Rarely has a crime fiction family been given a more bitter spin than this one.

Another strong outing by a modern noir master.

Couto, Mia | Trans. by David Brookshaw Farrar, Straus and Giroux (320 pp.) | $14.99 paper | September 30, 2025 | 9780374616311

A writer returns to his native Mozambique to reckon with his father’s history there.

The latest novel by veteran Mozambican author Couto is inspired by his own father, a journalist and poet who witnessed the abuses of Portugal’s colonial regime before the country gained independence in 1975. Here, the lead narrator is Diogo, who in 2019 is visiting the country as an honored poet.

The host, Liana, takes the opportunity to share with him a cache of files belonging to her grandfather Óscar, an agent of the colonial state police. Óscar detailed Diogo’s father, Adriano, under the pretext of collaborating with the anticolonial movement. But the story Couto unspools is more complicated than trumped-up accusations of plotting against the state. It is a story of racist state violence, centered on the 1973 massacre of Blacks in the town of Inhaminga by security forces. It is a story of the event’s consequences, particularly the death of Liana’s mother, alternately deemed a murder or suicide. It’s a story of Diogo sorting through the complexities of his father’s history, from poorly disclosed infidelities to attempts to counter the racist colonial forces. And as Liana and Diogo find their own relationship deepening, it’s an exploration of the possibilities for reconciliation. Couto’s narrative alternates between scenes in 2019, as Diogo revisits locations of his family’s past, and documents from Óscar’s archives that slowly reveal the truth about Inhaminga, Liana’s background, and his own conflicted feelings about state power. The formality of the documentation gives the novel a certain stiffness, and an approaching cyclone is a heavy-handed metaphor. But Couto’s storytelling is rich, while delivering a straightforward message: “When a regime starts arresting poets it is because that regime has lost its way.”

A contemplative study of colonialism’s collapse, and its enduring legacy.

Cranor, Eli | Soho Crime (384 pp.) | $29.95 August 5, 2025 | 9781641296977

freshman who’s backing up Matt Talley, a white star thrust to nationwide prominence by his success last season. So it’s not very likely that Moses will see much playing time—at least until Matt, fresh from his team’s latest victory, takes a header from a rooftop that ends his career, his life, and, thanks to the bag of money scattered around him, maybe his reputation. Mississippi state congressman Harry Christmas, whose years-long scheme to revitalize the region and incidentally enrich himself by paying to recruit and control top talent on the field, is furious that a distracted Matt didn’t throw the game, as Harry’s bagman, Eddie Pride Junior, had ordered him. But not so furious that he can’t turn on a dime and tender a similar deal to Moses. When the kid turns down the money, Harry threatens to call in Eddie’s crippling debts unless he persuades his daughter Ella May, who was with Matt on that roof moments before his hard landing, to offer herself to Moses, who’d resigned himself to losing that competition to Matt, too. Meanwhile, computer expert Rae Johnson, a rookie FBI agent whose father was a legendary football coach, is determined to look more closely into the star quarterback’s death, even though her much older partner, Frank Ranchino, keeps reminding her that their job description includes financial crimes, not murder. Cranor expertly keeps the pot simmering until a pervasive stench settles over virtually all parties. A powerful case for the proposition that “college football wasn’t a game at all; it was a business.”

Dang, Catherine | Simon & Schuster (288 pp.) $27.99 | August 12, 2025 | 9781668065570

Now that college athletes are finally getting paid, Cranor takes a deep dive into the days when they weren’t.

The University of Central Mississippi Chiefs quarterback Moses McCloud is a Black

An act of violence leaves a teenage girl hungry for more than revenge. Veronica “Ronny” Nguyen and her brother, Tommy—the family’s golden child—are embarking on what Tommy calls

“The Big Summer” as they get ready to enter high school and college, respectively. Americanized children of Vietnamese refugees, the siblings are pushing boundaries with their parents, M ẹ and Ba. When Tommy is killed in a car accident, the family is devastated and the gulfs among them—already filled with secrets and silences—begin to widen. When Ba’s brash and distant sister, Cô Mỹ, comes to stay, she brings with her stories from M ẹ and Ba’s past, as well as urban legends from Vietnam. While navigating unimaginable loss, Ronny tries her best to be a normal teenager by excitedly and nervously attending her first high school party. Unfortunately, this rite of passage turns into a nightmare when a classmate sexually assaults her—and something that had been dormant inside her awakens. As rumors swirl at school about Ronny, she finds it harder and harder to tamp down her rage and insatiable hunger for vengeance…and the sharp, salty, metallic taste of raw meat. As secrets about her parents and Tommy come to the surface, Ronny has to grapple with the realization that she has never seen the fullness of their lives: “I could only see them as what they showed me.” When Ronny embarks on her final act of revenge, she unexpectedly sets off a chain of events that brings her closer to her mother than she ever imagined. To move forward, they must do something they’ve never done before: unbury the past. Bound together with new understanding and tenderness, their relationship is forever changed. Balancing vulnerability, rage, horror, and compassion, the novel explores identity as both a blessing and curse. Brutal and poignant; Dang writes beautifully about the complexity of adolescence and generational trauma.

Dunic, Nina | Invisible Publishing (240 pp.) $17.95 paper | September 9, 2025

9781778430695

The second book by Canadian author Dunic is a story collection centered on people who get tripped up while just trying to go about their lives.

Dunic’s characters are all different sorts, at all different stages of life, dealing with tragedies, indignities, and other wild cards that cause them to lose their footing. In “The Apartment,” the persistent seen-through-the-window nudity of a woman living in the apartment across the street alters the relationship of the narrator and his platonic male roommate. In “Bodies,” a boy becomes something of a celebrity at his school after he discovers a dead body in a neighborhood park. In “Divorce”— with its ending worthy of O. Henry, it’s one of the collection’s standouts—a cash-strapped young couple’s purchase of a small oil painting has unforeseen significance. Some recurring motifs bring an organic-seeming cohesion to the collection: Several key characters have been on the receiving end of violence. Others have been widowed. Several protagonists are children. Dunic’s people discover that they are at a loss to make human connections or otherwise find meaning; as the subject of one story thinks at one point, “Her predicament now was the life she had left.” A few of the stories don’t completely gel—they seem to end a page too early, or maybe a page too late—but all the pieces are beautifully etched thanks to Dunic’s flair for the power-packed chiseled sentence. As the widow from whose perspective the story “Youth” is told thinks about the teenagers she has taken to observing, “There was something pure about them, like elements…hot and bright or dark and cold, sparking off each other, reactive and explosive.”

These stories give literary realism a good name.

Kirkus Star

Faulkner, Katherine | Scout Press/ Simon & Schuster (384 pp.) | $28.99 August 26, 2025 | 9781668024812

The aftereffects of a break-in chafe on a London mother, leading to her stubborn pursuit of unanswered questions in this hair-raising thriller. When a frightening man breaks into her London kitchen one evening, Alice Rathbone leaps into action. She’s hosting a playdate for her daughter and two other families, and when the intruder grabs a large kitchen knife and moves toward the room with the children in it, Alice goes into serious defense mode, grabbing a stool the man had kicked at her and fatally whacking him on the head. While waiting to hear from the police about whether she’ll be charged or cleared of any wrongdoing, Alice grapples with the randomness of the break-in, wanting to know more about her attacker. By all appearances, he was visibly under the effects of drugs or alcohol—or perhaps both—and had forced his way into a high-value home in a still-gentrifying neighborhood bent on destruction. But Alice can’t shake the desire to find out more about the person she killed, who turns out to be 18-year-old Ezra Jones. When, against her bail conditions, she wends her way into the life of Ezra’s family, things go spectacularly awry, even as Alice fends off anonymous phone calls and bitter, threatening online comments. The people closest to her—her husband, Jamie, a high-powered executive, and fellow school-focused mothers—beg her to move on, though one friend, Stella, a journalist, reluctantly agrees to assist with Alice’s investigation. Small items from Alice’s household go missing, the once-perfect nanny gives notice, and Alice’s life continues to fall apart. Skillfully spinning a taut, surprise-filled tale enlivened by multiple compelling characters, Faulkner keeps this highly

charged guessing game going until the final page.

A psychological thriller rife with pretzel-like twists, gaslighting galore, and revenge-fueled machinations.

Kirino, Natsuo | Trans. by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda Knopf (352 pp.) | $29 | September 9, 2025 9780307267580

Riki Ōishi still doesn’t know who she is or what she wants to do with her life. Will surrogacy be the answer? Without skills or a degree from a prestigious university, 29-year-old Riki is finding it hard to succeed in Tokyo, although she was keen to move there from her small town in rural Hokkaido. Working as a temp, lonely and broke, she’s living on boiled eggs and marked-down convenience food. So the idea of becoming an egg donor at a fertility clinic has its financial attractions. But Riki bears a close physical resemblance to Yuko Kusaoke, wife of ballet dancer Motoi. Because the couple can’t conceive, Riki is asked to become their surrogate through artificial insemination using her own eggs, in exchange for 10 million yen. Celebrated Japanese author Kirino’s dryly observed novel carefully considers the peculiarity of surrogacy: Is it just business, or exploitative, a transaction that takes advantage of “poor women selling their uteruses”? Over time, the characters all seem in two minds about the arrangement. Since surrogacy is illegal in Japan, Motoi and Yuko must divorce (on paper) and Motoi must marry Riki for the plan to go ahead. On a brief trip home, Riki ends up sleeping with an old lover. Then, back in Tokyo, she sleeps with another friend, so when she becomes pregnant (with twins), doubts arise over paternity. Yuko and Motoi start to grow apart, not least because Yuko has no interest in children that aren’t related to her. Motoi feels compromised about plans to raise infants if they’re not his. Multiple conversations ensue—sometimes

repetitively—about the options and ethics of the situation. Class, morality, obligation, and gender all come up for scrutiny as Kirino moves her figures through further emotional responses once the babies are born. The sifting concludes with Riki, who has matured (and suffered) enough, making a decision for all involved.

A curiously compelling debate about inequality and the complexity of choice.

Kraus, Chris | Scribner (320 pp.) | $29 October 7, 2025 | 9781668098684

The latest work of autofiction by an iconic Los Angeles writer. Kraus’ first novel in more than a decade meditates on her childhood in 1960s Connecticut and her middle age in LA and northern Minnesota, pinning down, in their contrasts and humming throughlines, “trace elements of a lost Americana.” Kraus records her days at these distinct points in her life, occasionally assuming the points-of-view of those close to her and, in the final portion, strangers. In the first section, “Milford,” Jasper and Emma Greene and their daughters, Catt and Carla, move from the Bronx to Milford, Connecticut, where Emma struggles to connect with her new community and parent Carla, who has a developmental disability, and Jasper works long hours and cultivates Catt’s literary sensibilities. The lens eventually shifts to Catt, the protagonist, as she tumbles into an adolescence of truancy, hitchhiking, and huffing office supplies. “Balsam” picks up four decades later, in Minnesota’s Iron Range. Catt is a well-regarded writer, living in Los Angeles. After a few summers spent in Minnesota, writing and escaping the claustrophobia of the art world, Catt and her partner, Paul Garcia, buy a cottage on a lake in Balsam to live in part-time. The Trump years bring personal as well as

political turmoil, as Catt and Paul face issues in their marriage and Catt confronts a wave of media attention from a new generation when her cult-classic first novel is adapted for TV. Then, in 2019, a shocking, meth-fueled murder near the cottage reels Catt into obsession with the four young people involved. “Harding” alternates between Catt’s life as she reaches for answers to this senseless crime and a fictionalized account of the events leading up to the real-life murder, based on Kraus’ research and interviews with those close to the case. Kraus’ deftness in planting events and swirls of thought in their respective places and times, revealing the rhythms of life with a subtle hand, transforms a series of anecdotes and a true-crime fixation into a stirring narrative of class, addiction, and the question of forgiveness in a cultural landscape increasingly hostile toward empathy and nuance. Kraus’ relentless curiosity is a gravitational force.

Lethem, Jonathan | Ecco/ HarperCollins (400 pp.) | $29.99 September 23, 2025 | 9780063388840

A late-midcareer retrospective, 30 stories spanning 35 years of work by a talented and celebrated writer. New-andselecteds tend to be miscellanies, and that can seem the case here: The stories vary widely

by genre, tone, and length (and to some extent by quality). But “miscellany” implies a catch-as-catch-can looseness that’s absent. These stories show off a versatility that rarely feels like randomness, because no matter where they go, they’re tethered to Lethem’s familiar nexus of themes (failure of connection, rivalry, the threats and depredations of technology, for a few examples) and techniques (mashup, flights of surrealism, talking animals, metafiction, humor, wordplay). As always, Lethem is broadly curious, genre-promiscuous, and genuinely unpredictable; he ranges, so his stories do, too. Highlights include “The Dystopianist, Thinking of His Rival, Is Interrupted by a Knock at the Door,” in which the title character conceives of a new peril, the Sylvia Plath Sheep, a despair-haunted creature that appears to be dangerous only to itself but is contagious, gradually “unwrapping its bleak gift of global animal suicide ”…and then he answers the door to find his ovine creation at the threshold; “Sleepy People,” in which we start with a narcoleptic spy affiliated with a bar (named “Quick’s Little Alaska” after its hyperactive AC) and proceed bewilderingly to a war involving marauding bands of talking dinosaurs…all within the frame of what feels like a psychological portrait of post-marriage loneliness; and “Access Fantasy,” which starts with the Julio Cortazar premise of a permanent traffic jam and then keeps doubling down. The spectacular “Pending Vegan” tells the story of a father, trying to kick antidepressants, who’s negotiating the moral and physical terrors of parenthood as exemplified by a trip with his wife and his fearful young

A compelling debate about inequality and the complexity of choice.

daughters to SeaWorld: flamingos, overpriced food, shark tanks, gift shops, hypocrisy, orcas, dispiritedness. Inventive, unpredictable fun.

Kirkus Star

Masad, Ilana | Bloomsbury (304 pp.) | $28.99 September 23, 2025 | 9781639737000

Three gripping narratives entwine as supernatural encounters and personal revelations transform lives in the 1960s and the present. This transporting novel brings multiple times and places to life through the storytelling of a researcher called the Archivist, whose nongendered pronouns are deployed gracefully. They’re consumed by two troves of records, both beginning in 1961 but radically different in detail and tone. In one, Barney and Betty Hill, rational civil servants in an interracial marriage, are astonished to see a spaceship as they’re driving down a dark highway. The sighting—and the encounter that follows—alters the course of their lives as they become ambivalent public figures amid a rising din of UFO spotters and disbelievers. (The Archivist knows something about alien visitors, too, but is even more reluctant to claim the association.) Through the second set of historical files, the Archivist tracks the life of Phyllis Egerton, a young writer driven from home when her parents discover her romance with her best friend, Rosa. Her new life in Boston is thrilling—Masad paints an electric picture of Phyllis’ double life as a newspaper copy

editor and a lesbian finding her people, sartorial style, and science-fiction writing voice—but necessarily clandestine, since this is the very real world of the ’60s: Public homosexuality is a criminal act. We get Phyllis’ story firsthand through her yearning, then defiant, letters to Rosa. In contrast, the Archivist takes more liberties with Barney and Betty Hill’s story, since their records are less personal. Without apology, the historian fills in the gaps for the reader, telling us both the facts and their elisions or outright inventions. It’s an education—they know the histories of civil and gay rights, and from experience, they “have always felt drawn to those who are ridiculed, misunderstood, shamed.” Miraculously, Masad makes this dense braid of stories easy to follow, elegantly blending serpentine sentences, endearing and intimately observed characters, natural dialogue, and playful, generous asides to keep the reader in enthralled suspense.

A dazzlingly original testament to companionship, curiosity, and faith in ourselves in times of fear and loneliness.

McAndrew, Tyler | Mad Creek/Ohio State Univ. Press (160 pp.) | $19.95 paper September 4, 2025 | 9780814259511

A collection reckons with big legal and moral questions. Just over halfway through McAndrew’s collection comes a story called “Crime and Punishment,” a title that would

accurately describe most of these tales, which often reckon with incarceration, guilt, and the aftereffects of violent acts. Sometimes that reaches baroque heights, as in “The Storyteller,” about a couple named Wayne and Nancy who buy “the house that had been the site of the famous Hobson murders.” The violent acts that took place there don’t return to the surface until the pair has divorced, with the house’s potential for supernatural visitations something Wayne taps into in conversations with his children. The young narrator of the title story sees an arm waving from a nearby prison and starts to wonder what its owner’s story might be: “at bedtime, my imagination unraveled like a scroll of every crime I’d ever heard of.” McAndrew has sympathy for many of his characters; Maria, protagonist of “The Familiar Dark,” has a penchant for casual burglary but winds up helping an older woman, Ania, who’s in the midst of a complicated grieving process. Late in the collection, McAndrew uses questions of crime and guilt to raise the stakes, placing his characters in places where they must try to understand the people in their lives—whether it’s a relative who committed a terrible act in “Letters From Toby” or a man with a penchant for unusual pets living in a halfway house in “How I Came To See the World.” McAndrew doesn’t shrink from asking big moral questions, and his fiction abounds with lived-in touches and a sense of scale.

Philosophical stories and memorable characters sure to spark debate.

McGinty, Patrick | Univ. of Wisconsin (286 pp.) $18.95 paper | September 23, 2025 9780299354244

An elusive young man struggles with the meaning of success.

Early on, McGinty says of his protagonist Kurt Boozel’s hometown that it’s “small, and there are eyes everywhere.” As the title

suggests, this is a story told in four parts as it follows Kurt from awkward adolescence to a degree of material success. Kurt’s academic skill prompts a coach at his high school to ask him to tutor TJ, an athlete whose grades are suffering. There’s a growing sexual tension between the two young men, which further isolates Kurt. He hasn’t come out to his family or friends, and his hesitancy to do so is one of the book’s ongoing threads. The novel follows Kurt to college, where he becomes enmeshed in fraternity life, and then to a career in finance, when he becomes obsessed with a Bitcoin purchase: “It took 24 whole minutes to walk to work, and in that time, Kurt missed an entire crypto opera.” The story is set in the recent past; McGinty references both the Occupy movement and Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection. We follow Kurt as he becomes more aware of his own desires and, later, develops a penchant for boxing. The prose style neatly evokes Kurt’s penchant for mental shorthand: “His brown eyes widening = I need you. Or = I’m dumb. Or = leave me alone.” But there’s a cautionary element there as well: Kurt is an ambitious young man drawn to the idea of success without understanding what it might cost; by the time he drives through a winter landscape to a family gathering, he’s on the brink of a crisis or a revelation— even if he hasn’t quite figured that out. An emotionally complex coming-ofage story.

McGuane, Thomas | Knopf (192 pp.) $26 | October 14, 2025 | 9780385350235

Nine stories of dead-end lives and wide-open spaces, set mainly in the American West. This slim collection from the Montana master seems like kind of a coda to his prolific career. It provides plenty

of bleak comedy, as morally compromised characters face mortality and determine that their lives haven’t amounted to much of anything, their existence seems as barren as the landscape surrounding it. In the opening “Wide Spot,” a cynical politician offers a first-person narrative in which a reunion leads to an inappropriate seduction attempt. In “Balloons,” a physician with a dying patient offers another firstperson narrative about the surprising retribution he faces for an affair that ended long before. From there, the perspective in these stories generally shifts to third person, but there’s nothing approaching omniscience. The protagonists, usually male, on the downside of middle age, are typically careless and often clueless. The natural splendor of their American West has been undermined by grifters: “Life in the West was a beautiful idea, best left in that state, a conviction not easily conveyed.…The place was infested with land speculators: house flippers, ranch flippers, and river flippers.” Two of the stories feature protagonists who have achieved some financial success, a good distance from Montana, and both are as miserable as the drifters and losers in the rest. In “Thataway,” a chain-store furniture magnate living in Palm Springs returns home for the funeral of one of his all-but-estranged sisters. The disastrous visit makes him realize that he has no home, and on the return trip to California “he had a fleeting hope that the plane would stay up in the air.” The concluding title story is the longest and perhaps the darkest, as a river trip fraught with tension and peril reveals the dysfunction of a tycoon’s family. Flinty and sharp-edged, these stories show no sign that the octogenarian McGuane is softening up.

Moss, Sarah | Farrar, Straus and Giroux (304 pp.) | $28

September 9, 2025 | 9780374609016

An elderly British emigrant in the west of Ireland narrates the birth of her nephew more than 50 years earlier. Edith, a woman in her early 70s, has made an enviable life for herself in County Clare. She lives alone in a cottage there, financially secure after getting divorced and selling property near Dublin. She has a lover and a cadre of friends, including Méabh, a local with whom Edith has found a deep rapport. And she’s found an even deeper rapport with Ireland itself, though she hails from a farm in Derbyshire in the north of England, raised by her farmer father and her “glamorous” French Jewish mother, whose own parents and sister were sent to Belsen during the war. Edith’s status as an outsider in Ireland means she has “learnt, as immigrants do…by keeping quiet, standing back, observing.” This sense of life on the periphery also connects her in memory to her past when, on the brink of attending Oxford, a 17-year-old Edith is sent to stay at a villa near Lake Como with her older sister, a ballerina. Elegant and cosmopolitan like their mother, Lydia is everything cerebral Edith feels she isn’t. Lydia is also eight months pregnant and opaque about the baby’s paternity, determined to give the baby up for adoption and return to her demanding life as a dancer. Moss switches back and forth between Edith’s present, told in close third person, and the past, told in first person and addressed to the baby that Edith and her sister await. Through these parallel narratives, and with her characteristically sinuous style, Moss is able to explore the idea of belonging: What does it mean to belong to a place? To a lineage? A family? A home? Moss directs her keen and graceful sensibility toward modern-day Ireland and 1960s Italy with equal aplomb.

At midcareer, the author has written his shortest—and sweetest—novel yet. It may also be his best.

BY MARION WINIK

TWENTY-FOUR YEARS AGO, a novel with the charmingly off-kilter title The Russian Debutante’s Handbook appeared in bookstores, announcing the arrival of what reviewers like to call a “bold new talent”: Gary Shteyngart, born Igor Semyonovich, who came to the U.S. from the Soviet Union at the age of 7. That ambitious, funny, intelligent debut, which featured a 20-something immigrant protagonist very much like the author, earned Shteyngart his first starred review from Kirkus.

At 53, Gary Shteyngart has just received his sixth star in seven books, this time for his shortest novel ever and his first with a child protagonist: Vera, or Faith. Vera is set in a dystopian near future, focusing on the trials of Vera Bradford-Shmulkin, a 10-year-old New Yorker with a lot on her plate as she tries to keep her Russian-born father and American stepmother together, learn what happened to her Korean-born mom, make her first real friend, prepare for a debate at school, and much more. The topic of the debate: a new anti-immigrant law decreasing the voting power of any American with a non-WASP background.

Our critic writes, “As the political situation in the United States evolves, Shteyngart’s particular flavor of black humor—Russian wry?—reconnects with its roots in sorrow and resistance and becomes essential and lifesaving.”

On a recent Zoom call, we asked Shteyngart to reflect on his career so far, and give us a hint of what’s to come.

As Shteyngart sees it, he began with two themes. “One is all the immigrant

Having a kid, being responsible for another human softenedbeing, me.

stuff,” he explains. “I was the first of my generation of Russian Americans to start getting published, and I wanted to get that experience down in the most interesting and entertaining way possible.” He continued this project in the novels that followed: 2006’s Absurdistan (“my funniest book,” he suggests) and 2010’s Super Sad True Love Story (“my biggest book”), in which the second theme, a fascination with speculative fiction and dystopias, fully emerged.

“Let me show you something,” he says, disappearing for a moment, then returning with a fanned-out stack of vintage Asimov’s Science Fiction magazines. “By the time I was Vera’s age, I was already in love with Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brave New World, and The Handmaid’s Tale, which was just coming out around then.” The future that he imagined in Super Sad, an authoritarian corporate regime driven by equal parts evil and stupidity, is a close relative of the world he gave Vera, “who is the same age as I was when I started reading Asimov’s.”

Shteyngart’s fourth book, the memoir Little Failure (2014), he sees as a watershed, the endpoint and “fire sale” of his Russian American immigrant experience: “Everything must go!” The sadder and more painful aspects of this adjustment, which he met with caustic humor in the novels, he faced directly and dead on.

The three books since occupy what his editor, David Ebershoff, half-jokingly calls his “middle period.” While the early novels have the feel of what Shteyngart calls “an angry young person waving at the sky,” these books possess a gentler soul, one he relates to becoming a father. (Shteyngart and his wife, Esther Won, welcomed a son in 2013.) “Having a kid, being responsible for another human being, softened me,” he says.

Lake Success (2018) is set during the lead-up to Trump’s first electoral victory. It follows hedge fund manager Barry Cohen on a cross-country Greyhound bus trip, fleeing, among other things, his conflicted feelings about fatherhood. Our Country Friends (2021), Shteyngart’s pandemic novel, is all about family, both biological and chosen.

And then comes Vera, featuring a “sensitive, intelligent kid, suffused by

anxiety,” not unlike the author at that age. By now it was clear that the “middle period” was marked not only by a change in tone but a change in process as well. Before Little Failure, says Shteyngart, “I had an idea, I wrote it. I took my time, and I got there. But each of the last three books was preceded by a 200-page draft of some other book that completely failed.”

He continues, “Before Vera, it was a spy novel. I did tons of research into the three different spy agencies in Moscow; my protagonist was a Russian spy planted in New York. I gave my editor the first 200 pages and he told me, ‘This is terrible.’” By now, Shteyngart knew the drill and thus he had a backup idea at the ready.

“On a long flight home from Tokyo, I rewatched Kramer vs. Kramer. I knew I wanted to do a divorce thing, but from the perspective of the child, like Henry James’ What Maisie Knew.” Shteyngart’s Vera is desperately trying to keep her warring parents together, delivering lists titled “Ten Great Things About Daddy and Why You Should Stay Together with Him,” and “Six Great Things About Mom.”

“I just started typing away—lately I seem to do all my best work on planes— and it came out really fast,” he says. “By the time I landed, I had finished the first chapter and started the second. In the first chapter you’re just trying to capture the voice, and it either works or it doesn’t. If you don’t capture the voice, then it’s back to square one. This time, there weren’t even many edits. I had it.”

Fifty-one days later, the draft was done—with a vestige of the original spy novel buried inside it, though stripped of all the research. “My usual process involves quite a bit of meandering,” he says, “but with Vera, I worked harder than I’ve ever worked in my life—so hard I began to get dizzy and went to the doctor to see if I’d developed some kind of vertigo. But when I finished the book, it immediately went away.”

There was just one problem. The completed draft was more than 100 pages shorter than any book he’d written before. “I was shocked, to the point where I felt super guilty,” he recalls. “Was this even a novel? I literally Googled, How long does a novel have to be? According to E.M.

Shteyngart, Gary

Random House | 256 pp. | $28 July 8, 2025 | 9780593595091

Forster, it’s 50,000 words minimum. My Word document was 50,022.”

Hard work and long flights have fueled two other works in progress. Coming next year is a collection of his much-loved essays from the New Yorker, the Atlantic, and elsewhere—his hilarious week on the world’s largest cruise ship; his encounters with capybaras the world over; his love letters to martinis, watches, and perfectly tailored suits.

“What’s most important to me is to live a good life, to find things I enjoy,” he says. “Of course it doesn’t always go well, and I write about that, too. The circumcision piece will be in there. That was the worst year of my life. As my wife put it, ‘I never thought that you would lose your sense of humor. But you have.’”

That much-discussed 2021 essay, about the botched procedure performed on him as a 7-year-old and a series of more recent treatments, inspires a downcast look from the writer. But he brightens as he explains that the other project is his first work for children, a chapter book about capybaras.

More about the snub-nosed, barrel-bodied South American rodent? There can never be too many capybaras, he assures me. “In a world of horrific human beings, I want to showcase the sweetest, kindest animal there is.”

Marion Winik is the author of The Big Book of the Dead and hosts the Weekly Reader podcast on NPR.

The author was known for his books chronicling the lives of gay men.

Edmund White, who wrote about the lives of gay men in more than a dozen novels, has died at 85, the New York Times reports.

White, a native of Cincinnati, Ohio, was raised in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois. He studied Chinese at the University of Michigan and worked as a journalist before making his literary debut in 1973 with the novel Forgetting Elena, followed five years later by Nocturnes for the King of Naples. In 1982, he published one of his best-known books, the autobio graphical novel

A Boy’s Own Story, now considered a classic of LGBTQ+ literature. That novel was the first in a trilogy that continued with The Beautiful Room Is Empty and The Farewell Symphony. His other novels include The Married

Man, A Saint From Texas, and The Humble Lover

He was the author of several works of nonfiction, including The Joy of Gay Sex, co-written with with Charles Silverstein; States of Desire ; The Burning Library ; and Genet: A Biography His memoirs include My Lives, City Boy, and, most recently, The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir, which was published in January by Bloomsbury.

White’s admirers paid tribute to him on social media. On the platform X, author Joyce Carol Oates posted, “Edmund White—the most gracious & witty of conversationalists whom Oscar Wilde himself would have much admired.”

—MICHAEL SCHAUB

For reviews of Edmund White’s books, visit Kirkus online.

The author was honored for “her transformative impact on literature.”

The Women’s Prize Trust announced that Bernardine Evaristo has won its Outstanding Contribution Award, a special one-off prize given in honor of the 30th anniversary of the Women’s Prize. The award, the trust said, “celebrates Bernardine’s body of work, her transformative impact on literature and her unwavering dedication to uplifting under-represented voices across the cultural landscape.” It comes with a cash prize of about $135,000.

Evaristo’s books include the novels The

For reviews of Bernardine Evaristo’s books, visit Kirkus online.

Emperor’s Babe, Soul Tourists, Blonde Roots, and Mr. Loverman, as well as the memoir Manifesto: On Never Giving Up. Her 2019 novel Girl, Woman, Other won the Booker Prize alongside Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments

In 2023, the Booker Prize launched a naming contest for the award’s trophy, and the name “Bernie”—a tribute to Evaristo—got the most votes. She declined that honor, and the trophy was named “Iris,” after author Iris Murdoch, instead. In a statement, Evaristo said, “Over the last three decades, I have witnessed with great admiration and respect how the Women’s Prize for Fiction has so bravely and brilliantly championed and developed women’s writing, always from an inclusive stance. The financial reward comes as an unexpected blessing in my life, and given the mission of the Women’s Prize Trust, it seems fitting that I spend this substantial sum supporting other women writers; more details on this will be forthcoming.”—M.S.

Muharrar, Aisha | Viking (336 pp.) | $30 August 12, 2025 | 9780593655849

A woman from LA heads to London in search of her on-again, off-again lover’s possessions after his untimely death.

Julia and Gabe meet in a summer arts program in Barcelona right before they head to college, after his mother, Leora, a poet who’s teaching in the program, introduces them, and they have a summer fling. However, the book opens with Julia at Gabe’s funeral, 12 years in the future. She has a successful jewelry-design business, and he is—well, was—an indie star known as Separate Bedrooms. She also tells us that just one month before Gabe died, they slept together, long after their first fling and unbeknownst to Gabe’s recent ex-girlfriend, Elizabeth, who lives in London and manages a bespoke floral studio as well as a hip restaurant. Readers will learn all of this as Julia sets off for London, prodded by Leora to rescue the older woman’s cherished guitar. At first Julia tries to appear blasé with Elizabeth, but after a series of blunders, they decide to join forces and find the three things Leora wants: the guitar, a baseball cap, and a piece of sheet music. Julia tries not to let on what she wants to find for herself: a medical bracelet she once made for Gabe, who had “situs inversus,” meaning his internal organs were reversed. Author Muharrar seems to want to show that Julia’s feelings are reversed, but it doesn’t work in the brief window the women have, just a couple of days until Julia’s return to the U.S. There isn’t enough time for us to understand Julia’s adult self, even with flashbacks to other times her life intersected with Gabe’s. Nor is there enough space for Elizabeth to come to life beyond her chic exterior. Muharrar’s fluid writing promises interesting future work, but this book might have remained a short story.

Poignant and well written, but with a slim premise and insufficient character development.

Mushtaq, Banu | Trans. by Deepa

And Other Stories (192 pp.) | $19.95 paper April 8, 2025 | 9781916751163

Sterling collection of short stories by South Indian writer Mushtaq. The first book of short stories to win the International Booker Prize, Mushtaq’s collection is also the first prizewinner to have been translated from Kannada, an Indian language whose flavor comes through in Bhasthi’s fluent translation, as when, in the first story, a newlywed woman ponders how to introduce her husband: “If I use the term yajamana and call him owner, then I will have to be a servant, as if I am an animal or a dog.” An attorney, activist, and sometime journalist, Mushtaq often writes of Muslim women in unhappy relationships. In one story, a woman returns home, facing shame for leaving an unfaithful husband forced on her in an arranged marriage, and chides her relatives for their role in her unhappiness: “I begged you not to make me stop studying. None of you listened to me. Many of my classmates aren’t even married, and yet I have become an old woman.” With five children to support, she desperately seeks a way out, with surprising consequences. In another story, a woman, maddened by a houseful of boisterous children on summer vacation, decides that the only way to get some peace and quiet is to enforce bedrest on the older boys—and that means enrolling them in a mass circumcision that is euphemistically billed as a celebration for the Muslim prophet Ibrahim, “a collective exercise in which children look forward to an event but end up screaming loudly together.” Mushtaq’s characters are

frequently at odds, and several have strange foibles, as with a religious teacher who becomes addicted to gobi manchuri, a cauliflower dish, which leads to some decidedly unsaintly behavior. The book is not without its flashes of sharp-edged, ironic humor, as when a woman seemingly caught in the throes of dementia is offered a Pepsi as “the drink of heaven,” but more often Mushtaq writes in near-documentary style of lives lived in constant struggle.

A memorable introduction to a gifted writer from whom we should hope to hear more.

Peck, Geoff | Univ. of Iowa (288 pp.) | $19 paper September 23, 2025 | 9781685970260

A young man reckons with some difficult truths. When this debut novel begins, the year is 2009. Nineteen-year-old Jeremy has just moved into his first apartment in Pittsburgh, which he shares with his film buff friend Scott. Jeremy struggles with his self-esteem; his old friend Kat is attending Carnegie Mellon University while he studies at community college. Jeremy’s relationship with his father, a former player for the Pittsburgh Pirates, has been strained ever since Jeremy quit playing baseball. A mysterious—and possibly sexual—encounter between Scott and Jeremy one night leaves the latter confused about his sexuality and his place in the world. His worldview is also expanding, with his coursework leading him to writers like B.H. Fairchild, John Steinbeck, and Thomas Bell. Kat’s growing political activism also has an effect on him, though her idealism sometimes manifests in statements like “Twitter’s going to change the world,” which may have been accurate in 2009 but feels more fraught in hindsight. Gradually, Jeremy becomes increasingly aware of Scott’s disdain for others and his racism—leading him to further question his life and his bonds

ZONE ROUGE