40 Painting

Essay by Peter Frank

Thank you, Bob

Wrestling With Something...

By Mara Blackwood

By Peter Frank

Simply put, I’ve spent the last 40 years learning how to paint. Of course, I can’t really put something so important to me that simply.

My evolution in becoming a painter, stands on a foundation of the years I spent making ceramic sculpture that began at the University of California, Davis in the “pot” shop from 1966 to 1968. These early days helped shape my aesthetic that twisted and turned, flip flopped, and disappeared only to reappear years later.

My earliest memory of making art still resonates. I wasn’t a child who drew or painted often, but when I did I held to my own strict rules. I allowed myself to paint something I thought was pretty, such as a flower, but there was another motivating intention. My flowers had to “do something”. Something useful for sure, such as what I might have been asked to do at that age like set the table, wash the dishes or another childhood task. These were my rules to draw by.

My self-imposed requirement of form and function was most likely an early stage of a lifelong wrestling with opposing forces to make sense of the world around us and compels me to make artwork that combines materials that have separate and unique qualities in themselves. Such as a digital print or computer-drawn lines, side-by-side with traditional hand painting, or oil on canvas with a steel sculpture.

Striving to combine these materials is my metaphor for seeking to comprehend the dualities life presents, such as body and soul, intellect and intuition, male and female, stillness and movement, familiarity and otherworldliness, stability and risk and most significantly, life and death. Wrestling for truth from an awareness of opposites also demands my empathy for differences.

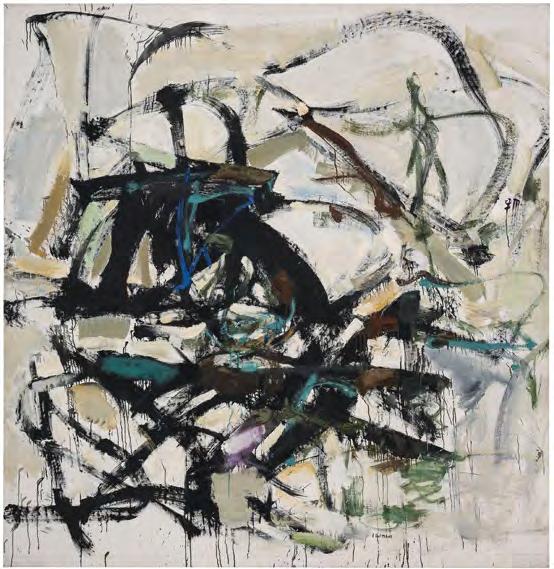

As I struggled to do what I thought was real painting, the Abstract Expressionists were my guiding light, most significantly Joan Mitchell and Willem de Kooning. I was attracted to their gestural marks, lines and smears, all in service of the poetry and music of abstraction that can feed the soul. Eventually, I became enamored with the various speeds of mark making, contrasting carefully controlled painting with fast gestural marks while pieces of the natural world - sticks, petals, a horizon line or sky - hatch out and become recognizable.

Searching to understand life, I assume that I’ll evolve and come full circle to a completely new place. That’s how it’s been. Sometimes I can feel the wind on my face before I can run.

Harmony Through Duality

BY MARA BLACKWOOD

In a time when there is so much conflict in the world, mixed-media artist Kim Thoman finds beauty in opposition. “I am always aware that duality exists in everything,” she explains. “Opposing forces inform the world around me—intellect and intuition, male and female, stillness and movement, body and soul, light and dark, the organized and chaotic, and of course, life and death. I strive to bring these dualities into balance, to present a ‘truth’ by showing its opposing energies.”

Viewers have felt this balancing force in Thoman’s work. The way she combines opposing colors, textures, and even art forms invokes a feeling of harmony that can create a sanctuary in any space.

Born and raised in Lincoln, Nebraska, Thoman began taking an interest in art when she was very young. She was a quiet child with a rich inner world and a sharp awareness of her surroundings, and it wasn’t long before she was expressing herself through drawing.

Some of her first works of art were imaginary “Moon Flowers,” which “were allowed to look fanciful, but they had to have some function that I deemed important on the moon—for holding gathered food or reaching around a corner, for example,” Thoman recalls. “Requiring that my drawings I enjoyed looking at but that the object drawn also had to have a functional value may have been an early indication of my later developed belief that opposites are in everything.”

Thoman grew up with five siblings, and her whimsical, abstract images often shared refrigerator space with her sister Marta’s more realistic art. “Most families would have identified [Marta] as the only family artist,” Thoman says, “but luckily, my mother’s natural psychological inclination allowed her to see some unusual potential in me.” Her family nurtured that potential throughout her formative years, and she has always felt that when she cre-

ates art, her studio reflects the joy and curiosity she experienced in her childhood playroom.

When she was about to start her senior year of high school, Thoman’s family relocated to Palo Alto, California. After graduation, she began college at the University of California at Davis and quickly discovered the ceramics shop. That was when she discovered that she wanted art to be more than a side pursuit. “I couldn’t get enough of the environment,” Thoman says, “although I was making sculptural objects that sometimes frustrated my instructors, such as a teapot that had no pouring spout or cup handles that were so thin they were completely non-functional. I’ve been a contrarian throughout my life and, initially, it always surprises people.”

Over the course of her studies, Thoman’s attention shifted from ceramics to drawing and painting, helping her develop a solid grasp of two dimensions as well as three. After earning her bachelor’s degree in fine arts from UC Berkeley, she sought

practical work. “I come from a long line of teachers,” she explains, “and that was the obvious career choice.”

Thoman continued to work in clay in her spare time while teaching art in elementary school for five years, then she entered San Francisco State’s fine arts master’s program. She felt like she was back where she belonged and relished the opportunity for further mentorship and growth.

Soon, her professors suggested a move to the painting department, “but at the time, I wasn’t interested,” Thoman says. “I wanted to ‘paint’ on the surfaces of my clay pieces, which began to get flatter and flatter so there was more space to paint!

The contrarian in me resisted my teacher’s suggestions.” Eventually, she produced a series of drawings and paintings with attached ceramic intestine-like forms, a precursor to her current mixed-media work.

After teaching community college art classes part time for several years, Thoman accepted a full time position at Merritt College and acquired tenure. During her years of teaching, she never abandoned her own artistic path. “Even with less studio time, my artwork continued to thrive because I’d developed the confidence to work through ideas more quickly,” Thoman says.

In fact, it was during her time as a professor that she began to develop the digital art techniques that have become such an essential part of her artistic development. “Using Photoshop, I make digital collages and print out on my large size 9600 Epson Printer on either paper or canvas,” she explains. “These collaged prints are made from scanning into the computer my own previously photographed artwork and using Photoshop to cut up, reshape, resize, etc. and rearrange bits to make a digital col-

*

lage. This, then, becomes an underpainting ready for my handwork.”

Though she often covers most, if not all, of the underpainting with traditional materials, such as oil pastel, graphite, soft pastel, acrylic, or oil paint, Thoman values this step as an important foundation for each piece. It provides her with material to react to, and it creates a layered effect that enhances the colors and textures.

Her interest in digital art has also led to the development of 3D printed sculptures, her evocative Emerging Venus series. These pieces allow her to experiment with creating images in three dimensions in a fresh, new way. She loves being able to twirl shapes around in digital art software and see how her paintings change as she wraps them onto a digital shape.

As Thoman developed her Emerging Venuses, she also began working with welded steel. At the time, she was recovering from a difficult illness: “While I was recuperating, my mind went to the desire for protection, support and strength. Well aware of the Terracotta Army, life-size sculptures of warriors made around 210 BC to be buried with a Chinese emperor for protection in the afterlife, I thought how wonderful to have an army of guardians for support in this life. I began the Sentinel Series.”

Thoman’s work has developed in distinct phases over the years, and her recent work has elements that harken back to these phases. As always, ideas about duality or opposing forces in all things dominate her expression.

“I feel extremely lucky to be creative and I require myself to learn from my creativity,” Thoman says, reflecting on her mission as an artist. “While I work abstractly, images from nature quite often hatch out—tree branches, leaves, sometimes petals of flowers or a horizon line and clouds. My work

teaches me about my connection to nature. For me, the practical application of duality requires that I live a life that takes into account ‘the other’ in hope of greater appreciation for and acceptance of diversity and differences among us. Whether any sliver of this seeps into the hearts and minds of my viewers—well, I should be so lucky!”

— Mara Blackwood

When I was ten, my father was a professor at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. A lasting memory was visiting the university art museum (now the Sheldon Art Museum) and seeing Elie Nadelman’s sculpture of a man leaning on or balancing himself on a skinny twig of a tree that would never hold his weight. I was smitten. In the 1990s, I ventured into mushy, squishy painting with an eye

to the Abstract Expressionists. It was Joan Mitchell’s work that modeled for me how a painting should look. Her colors and varied gestural marks felt familiar as if I’d met my future self. Willem de Kooning’s paintings were also a huge influence, but it took years for me to forgive him for his ugly women paintings.

In the 60s and 70s, clay was my medium. John Chamberlain’s crushed car sculptures were a favorite and remain a huge influence as I begin a journey combining steel sculptures with my paintings.

— Kim Thoman

* * * Untitled, John Chamberlain Painted tin-plated steel, 1961

Kim Thoman

BY PETER FRANK

Kim Thoman has long given graphic form – not simply pictorial body, but detailed, elaborately imagistic concretion – to philosophical and psychological concepts. Thoman is able to do this, especially with the persuasive force she so often musters, because she clearly maintains a visceral grasp of such concepts. They are not abstractions to her, but facts of human existence. And, in turn, the images Thoman creates, while technically “abstract,” do not feel distant or removed from experience; rather, they affect us like apparitions from vivid dreams, or like metamorphic variations on things we have seen – or think we have seen.

To be sure, they are expressions of the artist’s inner sensations. But they take on and build upon exterior forms, shapes and even objects we know from ordinary life – or even from extraordinary life.

Having emerged several decades ago as a kind of “comic abstractionist,” manifesting personal, indeed intimate, accounts in a funky cartoon language, Thoman subsequently developed what she identified as a “more universal” formal vocabulary. But in doing so she did not retreat into the reduced, stylized universalities of traditional non-objective art. Rather, she maintained her commitment to a highly charged kind of imagery, one that provides viewers with ready associations in the real world, “natural elements,” as Thoman professes, that symbolize her own personal and intellectual growth. “Perhaps I am simply an autobiographical artist,” she once mused, “documenting the process of my evolution – from the center outward.”

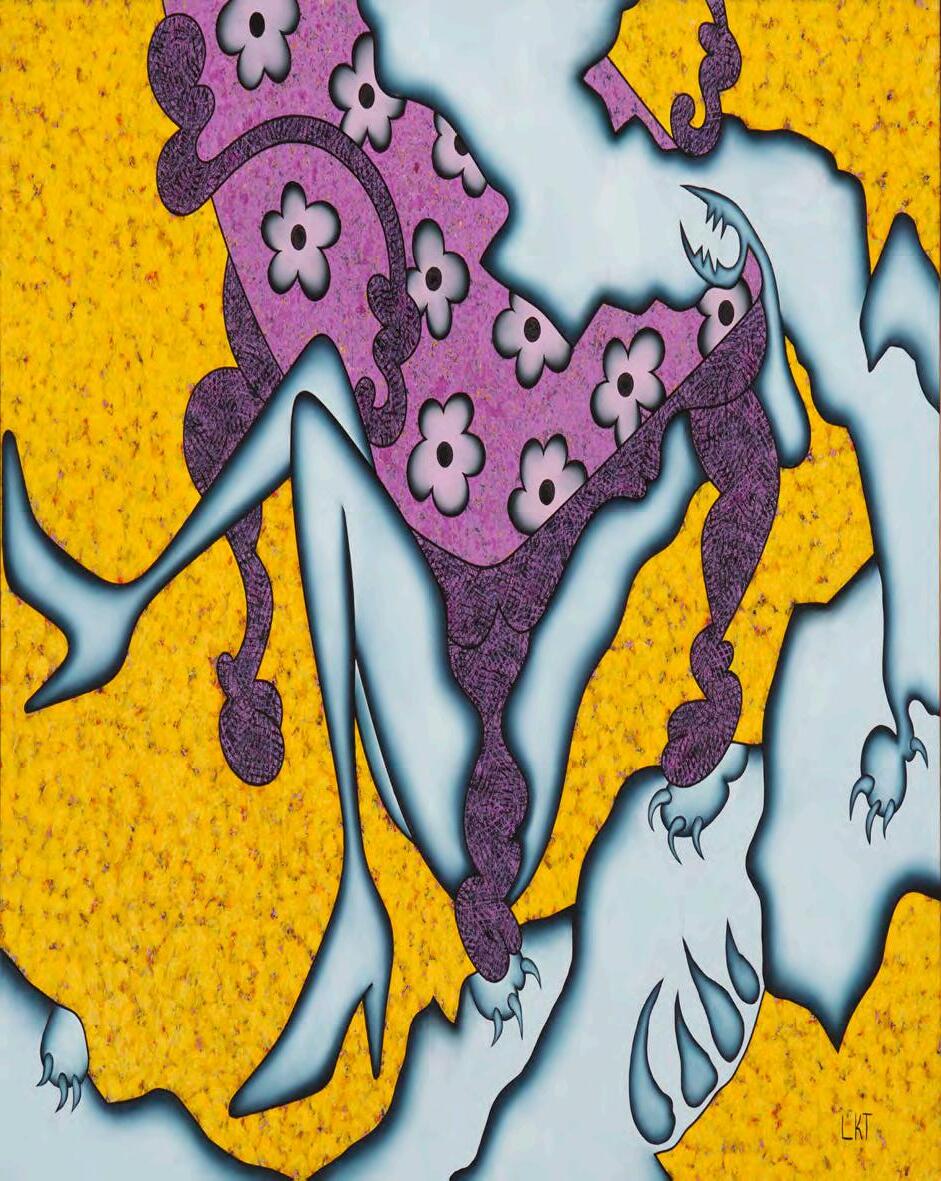

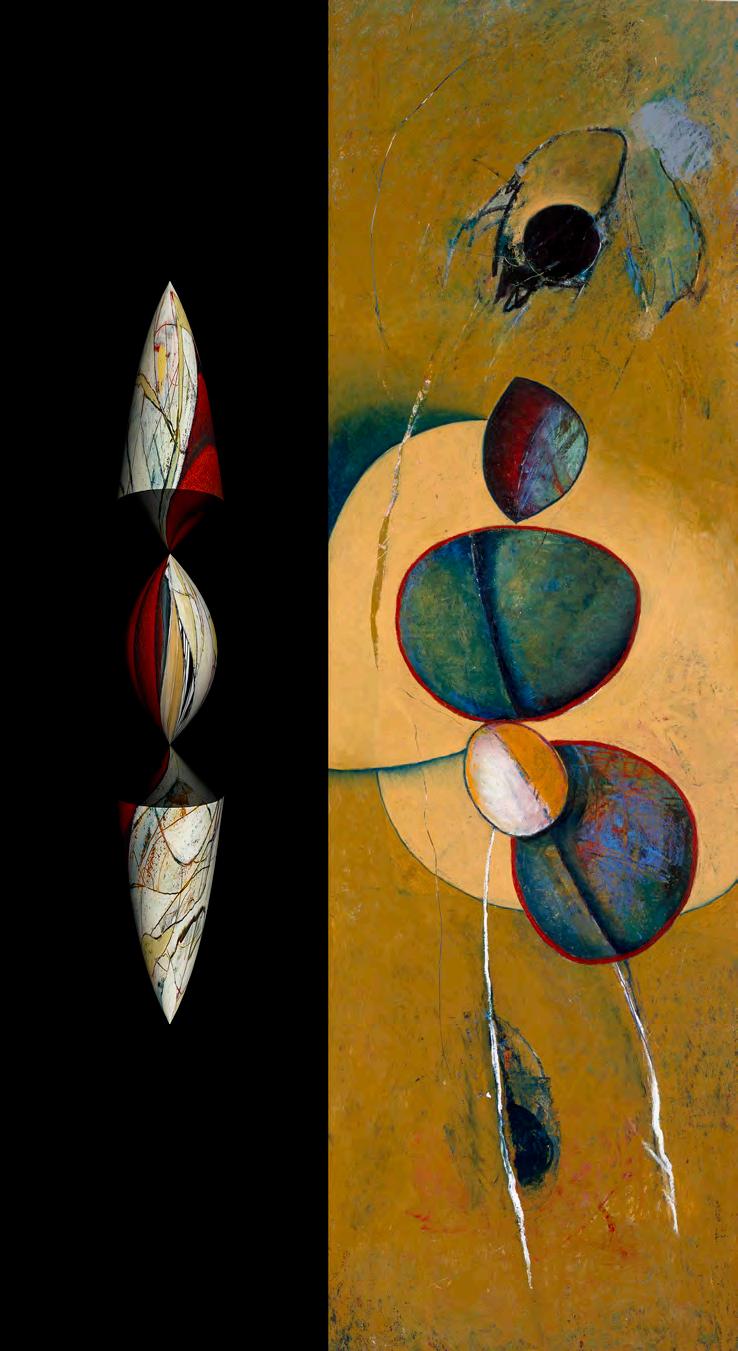

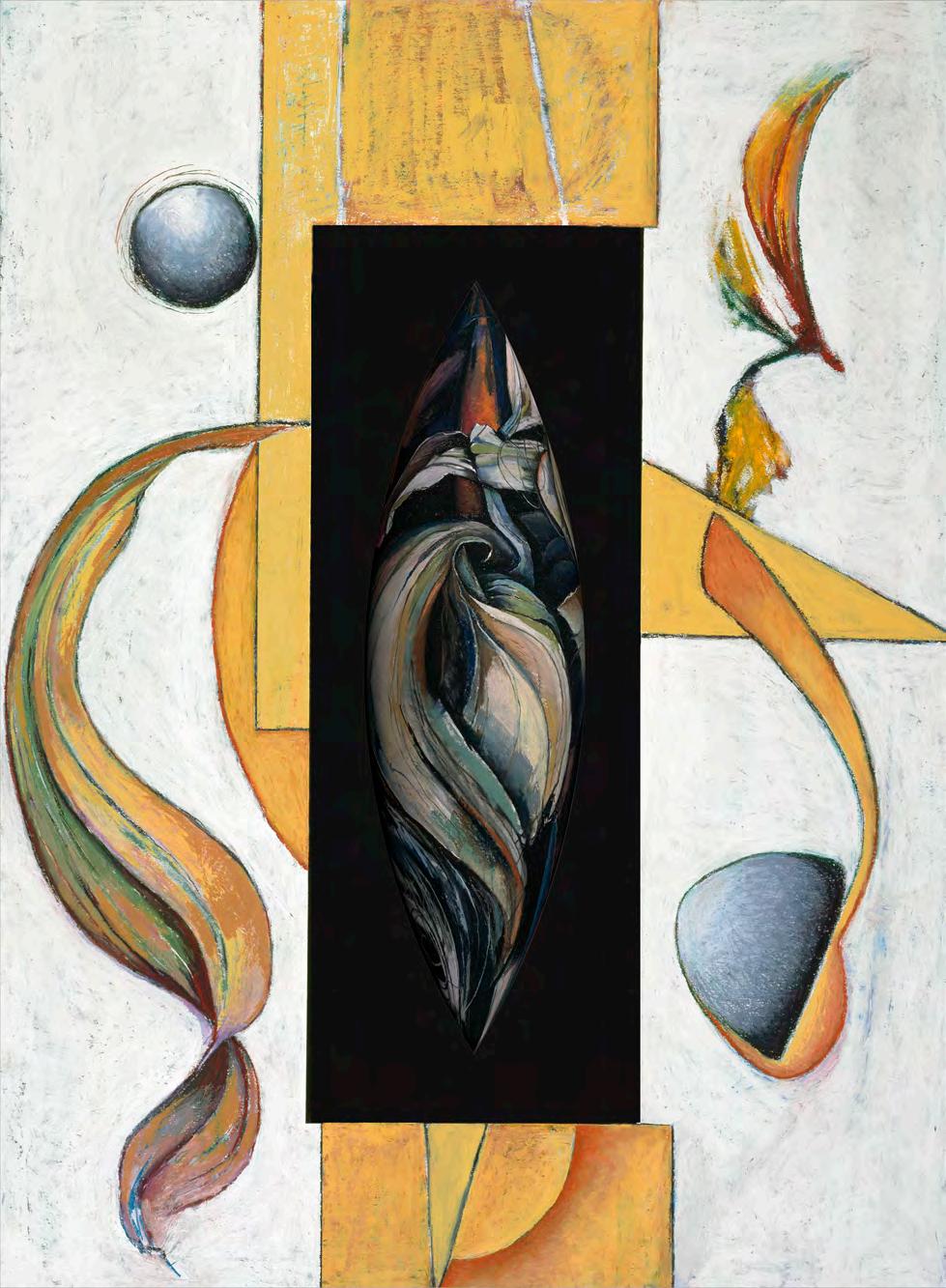

In her most recent series, including the Pod Series and Venus Series, Thoman troubles the notion of “center” upon which she had previously relied. To be sure, the floral forms and which she had previously nature-based images that have other predominated in her work for years still appear, and even dominate, and they still tend to conform to

round, orbital, symmetric shape. But now they are very frequently posited opposite equally intricate but natural-seeming forms who, for all their voluptuous curves, describe non-centric shafts. The duality here is fairly apparent, although Thoman does not belabor it. She does stress the condition of duality itself, however. The evident male/female contrast embodies only one aspect of the dialectical relationships Thoman senses throughout human and natural energy. She contrasts the hard with the soft, the organic with the inorganic, the dark with the light, the smooth with the rough, the vulnerable with the impenetrable, the efflorescent with the withdrawn, the supple with the brittle, the simple with the elaborate, and so forth. Any one of Thoman’s recent works can yield any number of these contrasting states. Indeed, the complexity of the formal relationships set in motion (not simply presented) by Thoman’s elegant and forceful style evolution invites viewer interpretation almost to the point of self-revelation. If Dr. Rorschach had devised a dualistic rather than singular format for his method, his forms could well have been the armatures on which Thoman builds her pictures.

As it is, Thoman’s pictures stir something primal in one. They posit dualisms, but they point at unities, as if prompting the eye to synthesize as quickly and thoroughly as possible the opposites before it. Is Thoman simply exploiting the human mind’s – or heart’s – desire for resolution? In fact, she is questioning that very desire, or at least the timidity it engenders. Don’t be afraid to grapple with conflicts, Thoman declares in her dualistic works; the resolution may in fact not lie in making peace between the opposed elements, but in making sense of their difference. They don’t have to merge, they don’t have to agree, they simply have to harmonize – and it’s up to your mind, your eye, your heart to find that harmony.

In this regard, Thoman’s Pods and Venuses may not resolve, but they do balance. She employs a range of media to produce these lucid, emphatic pictures, everything from obdurate oils to delicate archival inks, “marrying” the still-new digital technology to the centuries-old technology of panel painting. That in itself determines a dialectical tussle of sorts, a meeting and arguing of modalities originating in markedly different civilizations. But the civilization that gave us painting is the direct ancestor of our own digital culture, and the genes show. Thoman knows this, and demonstrates how the seeming disparity between the two methods works ultimately to the advantage of both. Similarly, the scrutiny, until the two sides of the equation, once seeming disparity between the charged image on one side of a typical Thoman composition and that on the other side slowly unwinds under continued seemingly unequal and described in totally unrelated visual languages, now seem like mirror images of each other.

If we can take away a moral and social lesson from Kim Thoman’s oeuvre, it is that conflict resolution lies within each of us. Thoman does not think of herself as wiser than the rest of us, only more fortunate by dint of her work with art to have discovered for herself the harmony of the universe. That harmony is not in the propitious alignment of forms and meanings, but in our discovery – or, shall we say, acceptance – of balance between haphazard pairings and contrapositions. Things don’t exist in opposition to other things, but only in balance with them. Finally, Thoman doesn’t resolve conflicts, but reveals their superficiality. At heart, everything is in union.

Peter Frank, Los Angeles, January 2012

1980s & 1990s

“Michael and I were hanging the work with the help of a custodian when all of a sudden, down at the end of the hall we heard a loud voice bellow, ‘What is this crap?’”

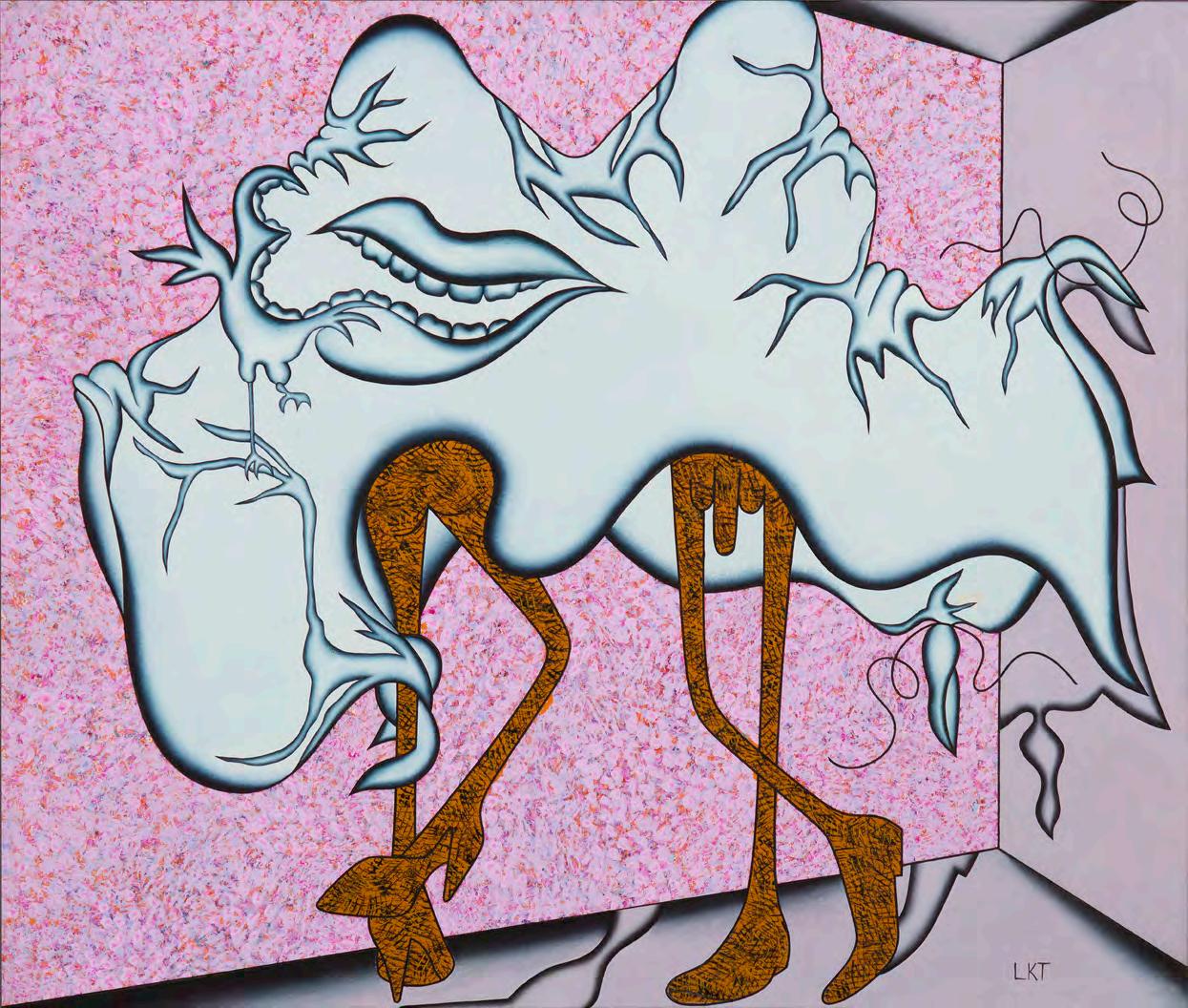

I’d been invited by the Director of Student Services to hang a series of my 1980s paintings at the California School for Professional Psychology (CSPP). A flap ensued beginning with the Dean’s loud bellowing demand and within days my works were anonymously taken down and turned to face the wall. I was asked to come retrieve my art as the institution felt unable to guarantee that the works would not be damaged.

In 1993, Richard Whittaker, Editor and Publisher of TSA (The Secret Alameda) interviewed me and wrote about the episode in the magazine’s publication #7. With his permission, I’ll quote from the article.

“Kim Thoman, a painter living in Oakland, had decided the time had come to find a place to exhibit a series of paintings she’d done over a threeyear period from 1983 to 86. This body of work was deeply personal and she’d been reluctant to exhibit it. The series of paintings had coincided with her entrance into a period of intense psychotherapy and were very much a part of her therapeutic work. Eventually, she felt she’d come to terms with the demons addressed in these paintings and she began to think about exhibiting them…The paintings were installed and a written statement by Thoman was posted with the exhibit that included her comments, ‘I’ve asked myself what I was doing when I painstakingly outlined each of these funny looking figures…My closest answer is that I was doing research. I was, however, both the researcher and the researched.’”

Besides Richard’s insightful article, which he wrote about this unforgettable episode in my art life, I was also interviewed for CSPP’s student newspaper. Unfortunately, although I very much enjoyed

the conversation with the student editor, it was never published. However, it was during this interview when I learned that it was possible a group of strong feminist students were the likely source of dissatisfaction over exhibiting my works – even beyond the Dean’s obvious objections. This was a heartache for me to have my work so deeply misunderstood by women with whom I most likely shared much of the same concerns, frustrations and confusion about a woman’s place in our culture. Yet, I was astounded at the irony of a training institution for psychologists having such an overreaction to stimulating visual images. Today, I look back at these paintings and am deeply proud of the young artist who dared to paint them and attempted to show them. Now, in my 70s, I am pleased to find the viewing public has a rich curiosity and interest in them.

— Kim Thoman

1990s

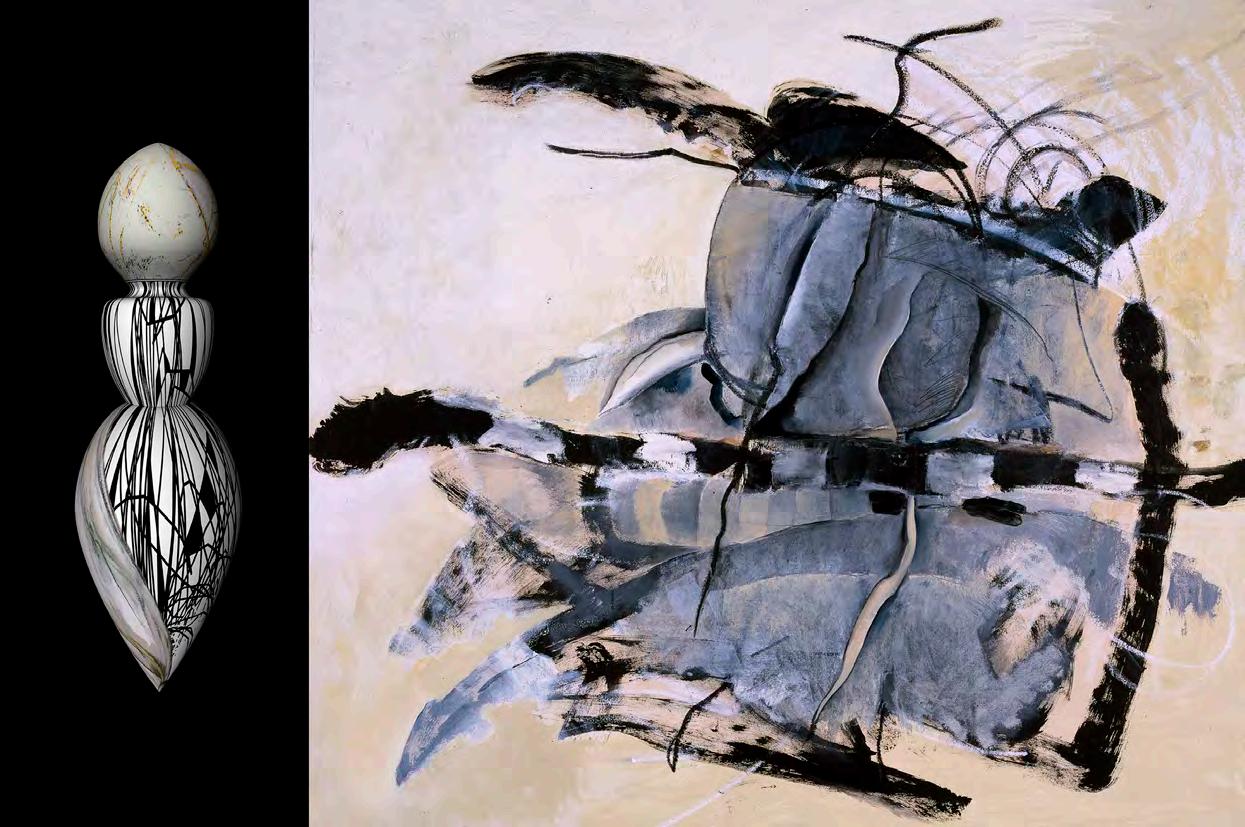

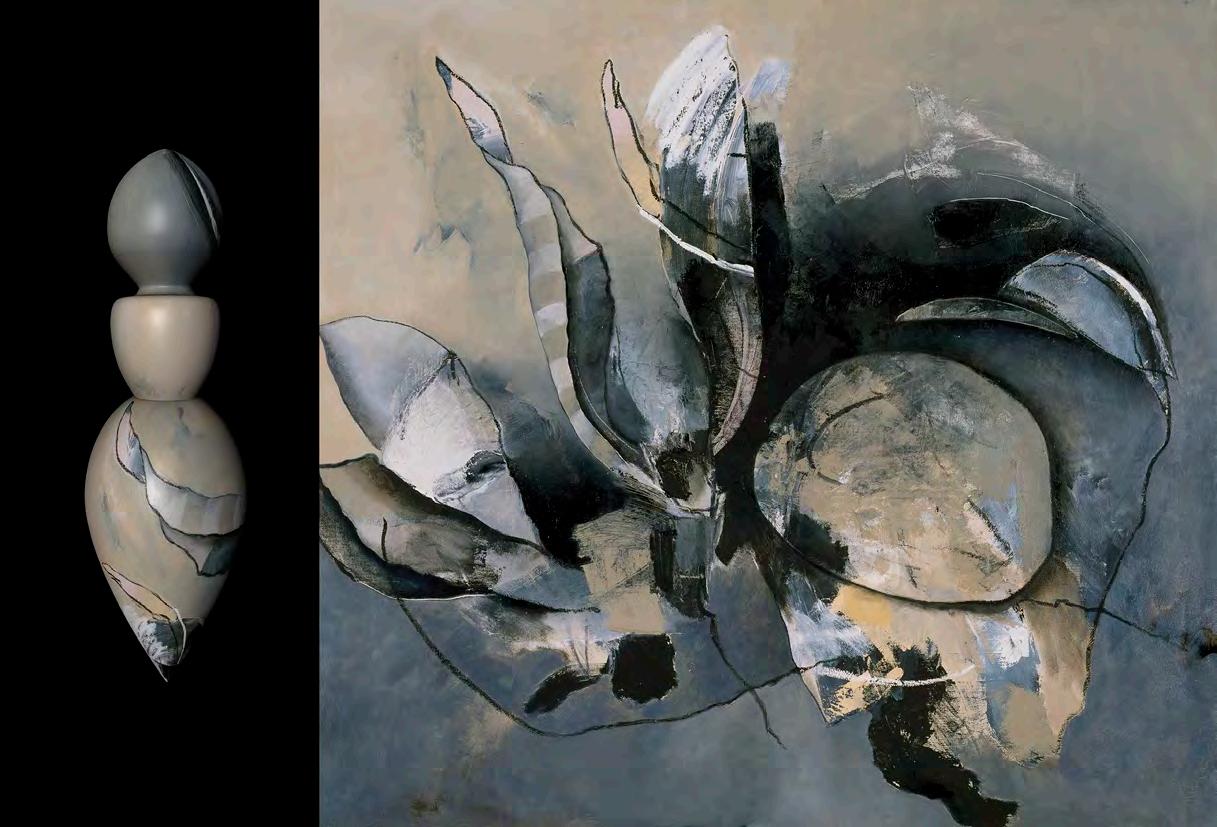

This decade was filled with experimentation. While sorting out what I wanted to paint, I was also exploring my painted mark. And, at the same time there were early hints at splitting the canvas and adding 3D elements – all to hatch out in later decades.

I was teaching art at a local community college and my dean asked me and two other art instructors to start up a multimedia department. We looked at each other and said, what’s that?

Joe Doyle and Peter Freund and I dove in.

I discovered two things that stuck. The computer would become for me an essential tool for my creative output for the next 35 years. Printing digital collages on paper or canvas as underpaintings for my handwork, or later as a panel for a diptych or triptych, became part of my working method. Secondly, I found that I wanted to teach only traditional studio art classes. Both of these came about.

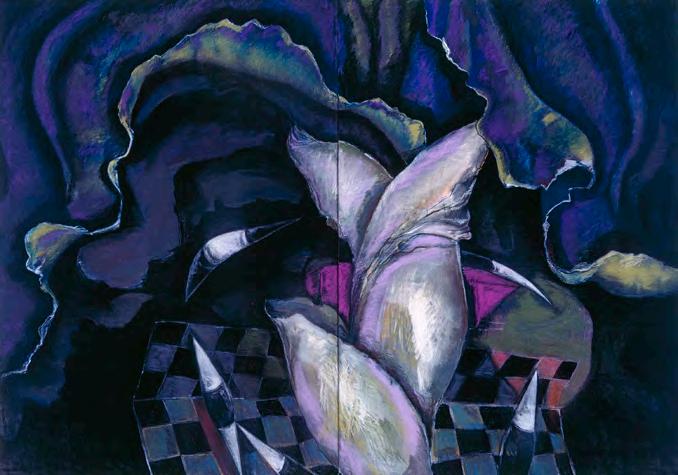

The images on the following pages show some of the directions I explored in the 1990’s that I expanded on in later years. For example, attaching 3D elements to the frame of my paintings (in this case wooden chair parts) later became ideas in steel. Diptychs have remained an interest for many years as I’ve searched for ways to explore different ideas that when placed side-by-side read as greater than individual panels. And, over the years, I’ve repeatedly paid homage to and learned from artists I’ve admired by including some parts of their images in my own work. In this case, I’ve lifted one of the irises from Pat Steir’s painting of 1982, Study for the Brueghel Series: Iris in Four Parts and titled my paintings, Pat’s Iris with Bowl and Pat’s Iris with Bean.

Years later, but before I began working in metal, I borrowed images of John Chamberlain’s crushed car parts sculptures to use in my mixed-media works on paper. I altered his images in Photoshop to an extent that they were unrecognizable as his, but the process of incorporating his work into mine was a way of honoring an artist who I greatly admired. At this point, I felt too intimidated to work in metal and secretly hoped that by using his images in my digital collages, I might gain some strength from him to eventually work in metal myself. That happened years later.

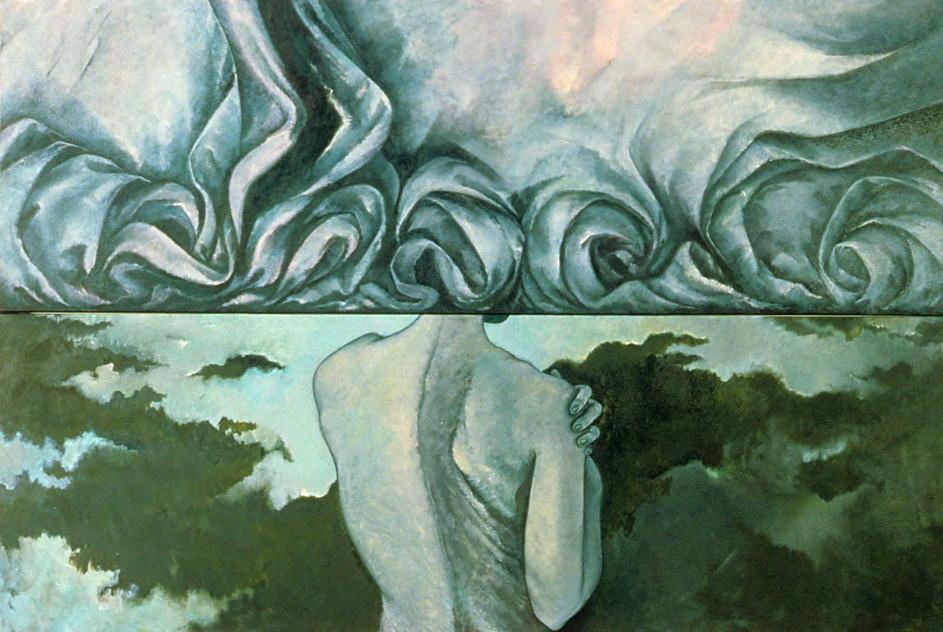

Self-Portrait, oil on two canvases 52” x 66” (132 x 168 cm), 1990s

Retreat Years 1999-2014

Motion Series

My first art retreat was to the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson, VT, in 1999. The experience working in a different location of the country was a take for me and for the next 14 years, I went every year to either an organized art retreat or I created my own. My rules for a retreat of my own making included a location where I knew at least one person, where there was a good art supply store and, if possible, a nearby college. It’s easy to contact a local gallery and explain I’m an artist from out of town looking for a studio to sublet. The networking takes off. I’ve always had wonderful experiences, made lasting connections and had generous offers. Many of the Motion Series pieces were made while I was in Blacksburg, VA, one of my first homemade retreats.

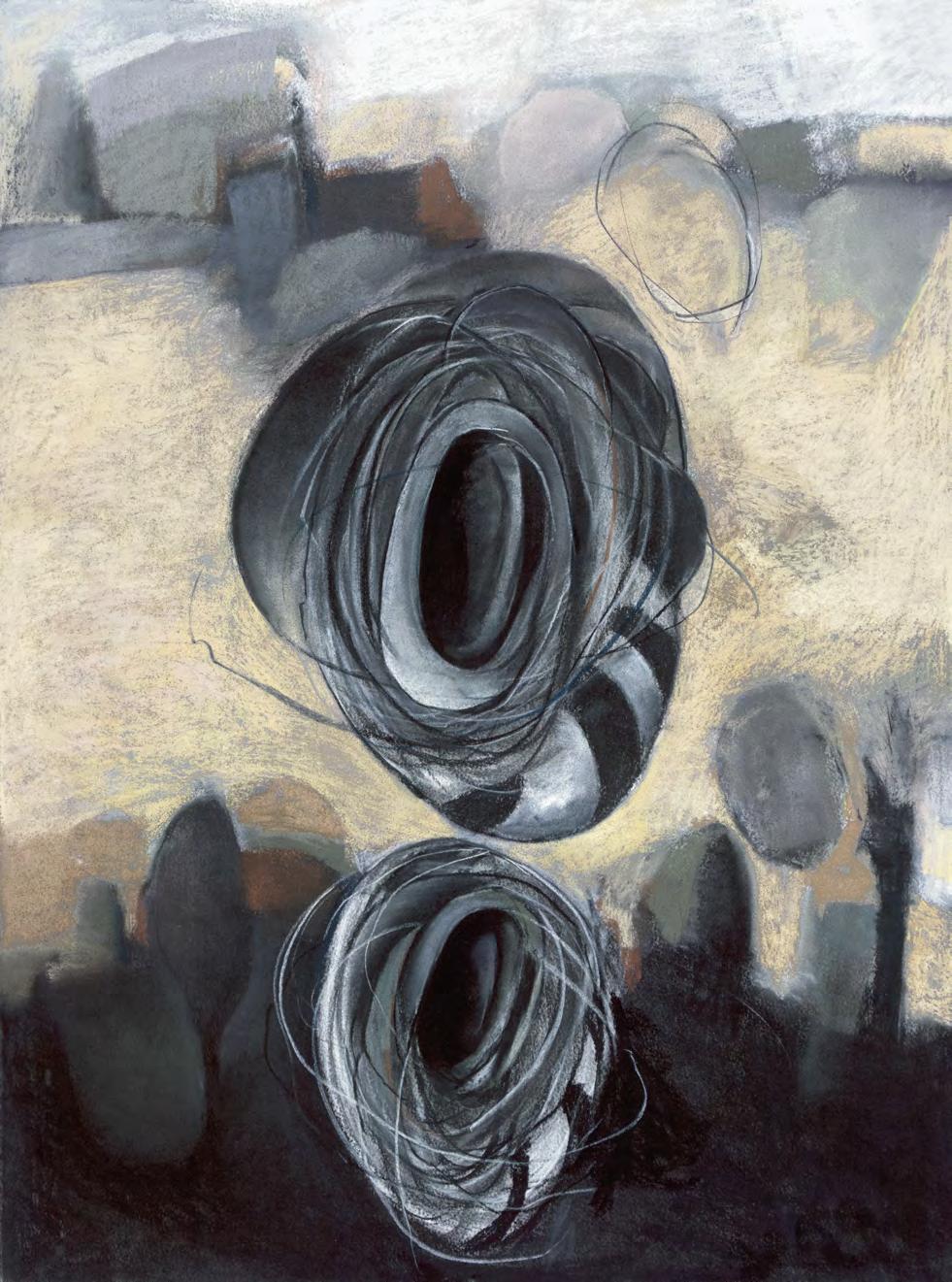

Spiral Series

I never stopped making art while I was teaching; however, my art retreats were in the summers. I had purchased a large-scale 9600 Epson printer to make limited edition prints and also to create digital collages as underpaintings. A large cardboard tube of rolled paper slept in the upper bunk while I mostly traveled by train to and from summer retreats. Spiral Series began at the Vermont Studio Center, Johnson VT and was completed during another retreat the following summer in in Santa Fe, NM.

Mother of Pearls Series

In the summer of 2006, my mother was living in Seattle and wasn’t well. Seattle became my destination for an art retreat and mom became the subject of this series.

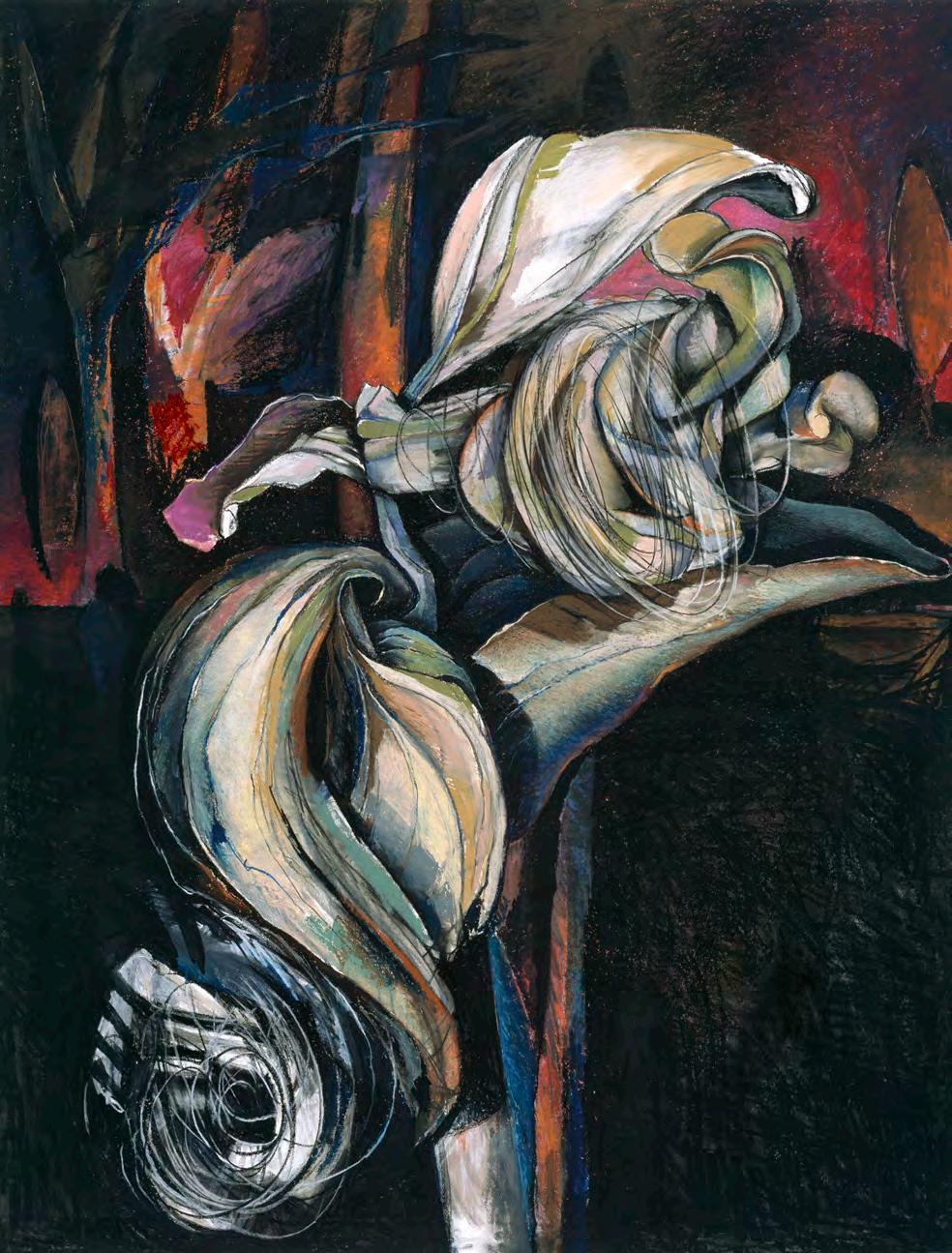

Iris Heart Series

In 2007, I received a Helene Wurlitzer Residency Grant in Taos, New Mexico.

These pieces started with parts of the iris in Motion Series 17. I used Photoshop to cut, alter and print the altered iris to make an underpainting.

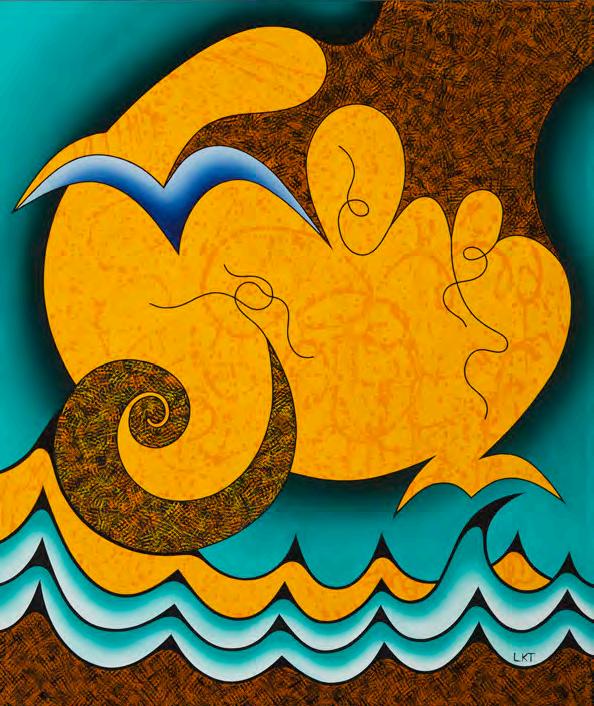

Pod Series

Exploration of the computer as an art tool continued during retreats to Taos, New Mexico over six or more summers. Shapes are designed in Cinema 4D software, and scanned paintings are used to digitally wrap around them. I called them pods.

Venus Series

Pod shapes were re-imagined with the Venus of Willendorf in mind. Venus of Tim is a memorial piece for a beloved nephew.

Emerging Venus Series

After working with 2D computer images of Venus, I was excited to see what they would look like in 3D. The new Venus pod shapes were created in Cinema 4D and digitally wrapped with my scanned paintings. It was crucial to find a 3D printer that could print in millions of colors. It wasn’t easy to locate a company with this type of printer that didn’t require an order of 10,000 instead of 10. A firm in Colorado that makes architectural models was happy to print for me. Working in steel was then used to create a structure to hang the Venus.

Parallel Universe: Green Trees, mixed-media on paper

Venus Series

BY PETER FRANK

Although known as a painter and digital printmaker, Kim Thoman received her MFA degree in ceramic sculpture. Her combination of two and three-dimensional elements in works that comprise the “Venus Series” can be seen as a resolution of Thoman’s twinned impulses to the graphic and the volumetric. And her recent engagement of 3D imaging can be regarded as a means of achieving a conceptual and visual continuity between the conditions of painting and drawing and those of sculpture. As Thoman observes, “The electronically created panels are a more intellectual process while I use an intuitive mark-making process on the oil-painted panels.”

The “Venus Series”, which pairs painted vegetal forms with elaborately inscribed symmetrical solids, thus posits a coupling of physically complementary factors – in accordance with Thoman’s philosophy that “duality exists in everything.” In effect, every phenomenon is a balance of opposites, a dialectical resolution of contradictions that reveals hidden harmonies between supposedly antagonistic forces. As the title of the series indicates, we can regard Thoman’s Venus works as gynocentric in expression, centered on the anima that defines the artist’s own gender. In her diptychs and triptychs, the three-dimensional element is depicted, and in the free-standing sculptures (the “Emerging Venus Series”), the two-dimensional element is applied to the surface of the sculptural. The three-dimensional element is invariably a curvaceous form, one all human beings would recognize as female. Indeed, it can be considered a direct descendant of the Neo-

lithic Venus of Willendorf, slimmed down, as it were, to fit modern concepts of health and beauty. But the “Venus Series” contains the masculine as well as the feminine. The series, attests Thoman, “was shaped by the landscape and sky of Taos, New Mexico,” where she spends part of each year. “The Taos Mountains offered a sense of security as the exuberant sky manifested surreal visions that left [me] ungrounded, but responsive to the huge mound of earth rising upwards.” In other words, in Taos Thoman viscerally grasped a synthesis between earth and sky – the original “female-male duality” – that undergirded her concept of the sculpted anima (= earth) and painted animus (= sky).

— Peter Frank

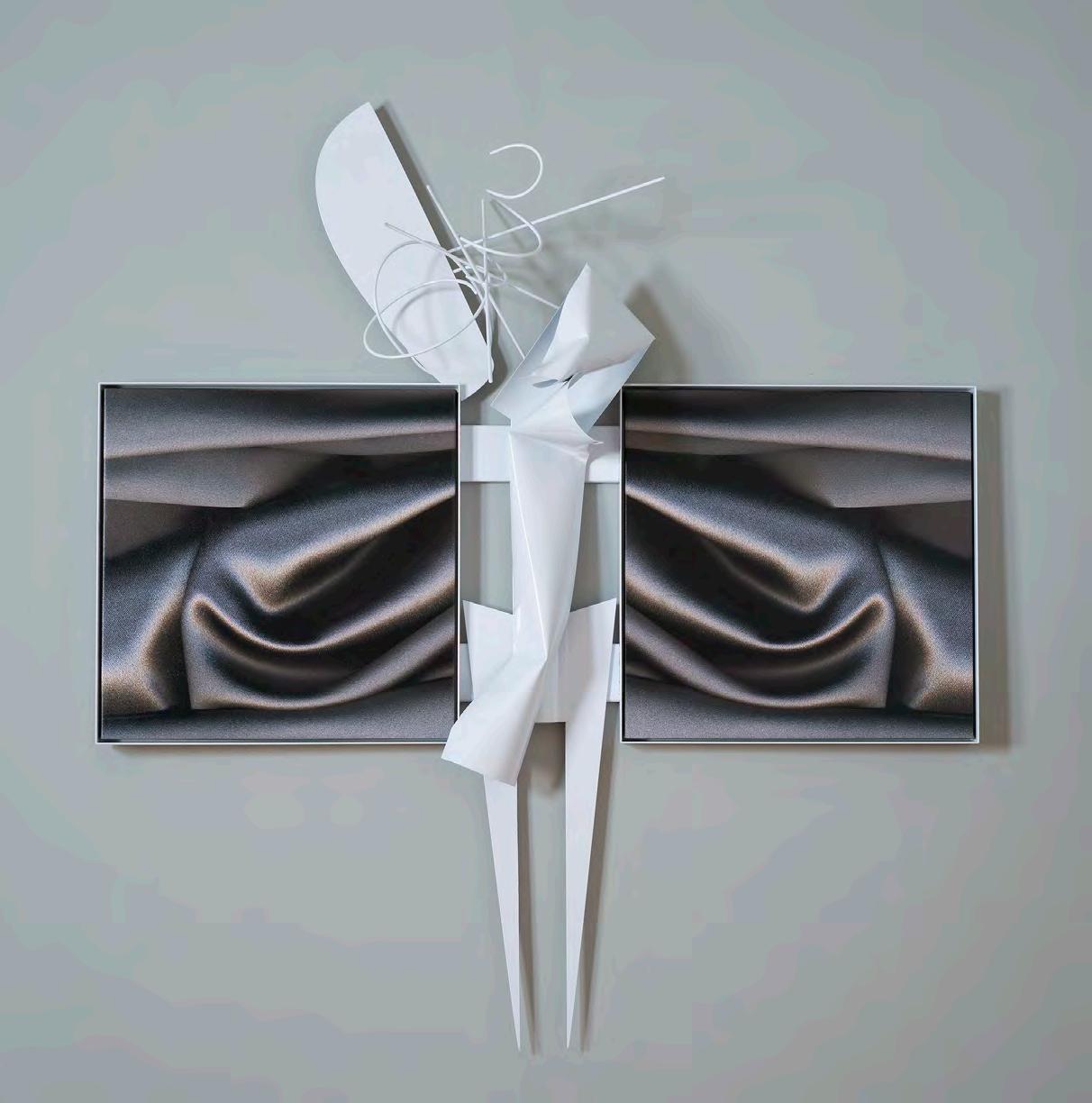

Gray Matters Series

The wild loincloths seen in crucifixion images of the 1500’s, such as a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, captured my attention.

Gray Matters

BY PETER FRANK

The “Gray Matters” series, dating back several years, presents Thoman’s concept of duality in the most literal terms, splitting the picture down the middle and setting the image in each left segment against that in each right segment. In each painting the images arranged left and right are notably similar to each other, inferring that the oppositions we see in the world are actually between like forces. We can extend that to the observation that our supposed “enemies,” the other people in the world against whom we think we compete, are in fact our equals and our allies.

The real enemy, you could say, is not the force that mirrors us, but the force that divides us – here embodied in the recessed panel at center. Thoman has designed this divisive element as a kind of crucifix, itself echoing the human body, especially if the painted angles atop each pair of panels can be read as embracing arms or wings. In this regard, then, even the element that separates us seeks to bring us back together, to enfold us all in a peaceful embrace. Thoman also regards the “arms” as proposing a “metaphor for the duality of human versus… divine.”

“Gray matter” refers not only to the predominance in this series of the “color” gray (which, as Thoman notes, is made by combining opposites on the color wheel), but, of course, to the human brain. That organ, source of our reasoning and our passions, our fear and our love, is itself formed as a duality. The images Thoman splays on either side of each gray recessed vertical do not closely resemble human brains. But they approximate our brain’s incessant churn of activity, the process of perception, analysis, and creativity that makes all of us, women and men alike, uniquely human.

— Peter Frank

Illness, Recovery, and Steel 2014-2019

Shortstop Revisisted Series

John Chamberlain’s crushed sculptures made from parts of cars are a huge influence. I downloaded pictures of Chamberlain’s sculptures, altered them in Photoshop and created digital underpaintings for the following works on paper, and can be seen on the top, bottom and sides of the images.

Shortstop, by John Chamberlain, crushed car parts, 1957

Nesting Series

Background, dripped acrylic paint, turned sideways.

Shortstop Revisited 5, mixed-media on paper

Revisited 5, mixed-media

Shortstop Revisited 16, mixed-media on paper

37” x 31” (94 x 79 cm), 2016

Shortstop Revisited 3, mixed-media on paper

Revisited 1, mixed-media on paper

Sentinel Series

While I was undergoing chemo, I recalled the Terracotta Warriors, life-size clay figures made for the Chinese Emperor in 200 BC to accompany him for protection in the afterlife.

I began the Sentinels for Health - body guards as protectors during life. Who doesn’t need a personal “army” to guard our health?

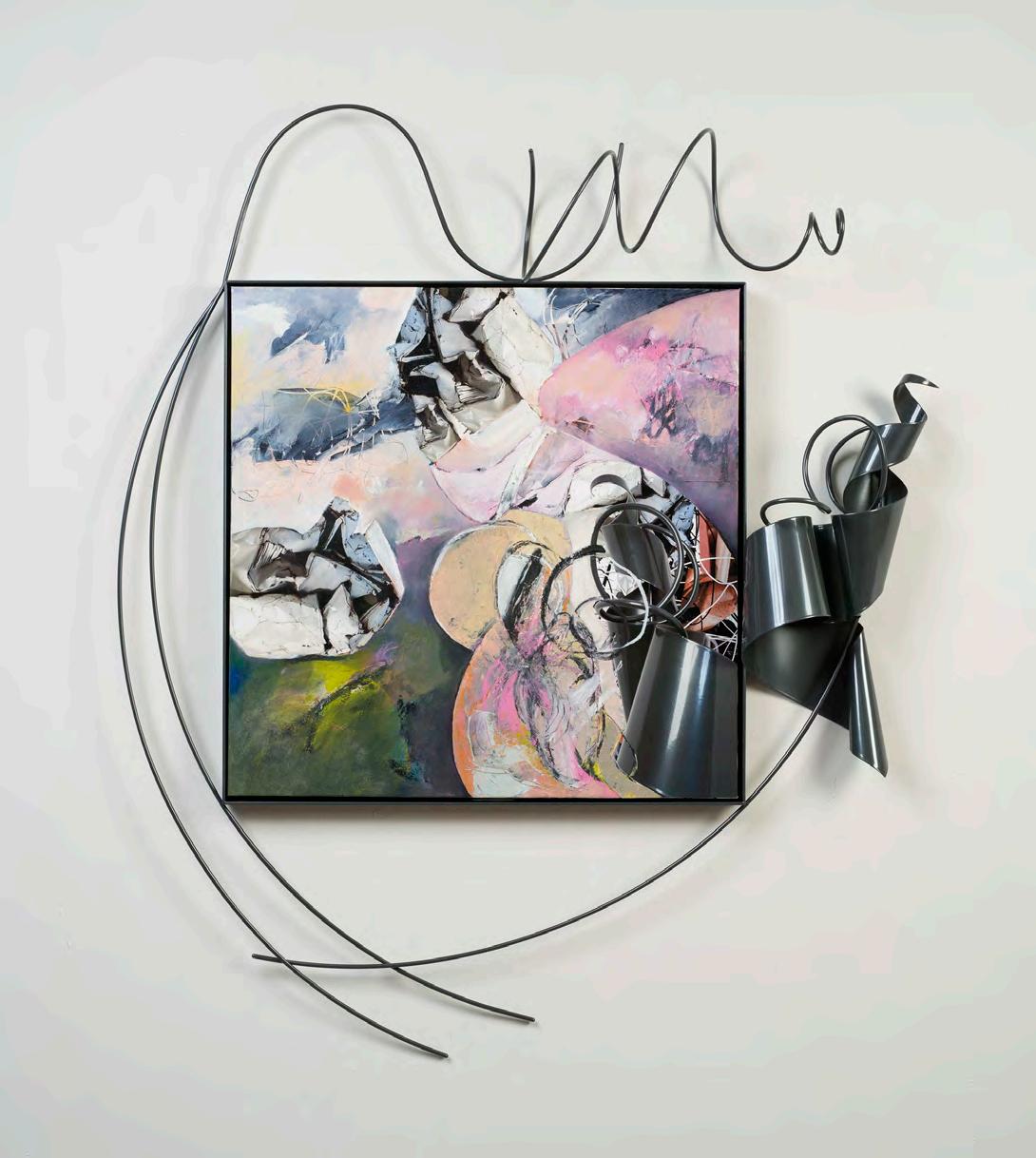

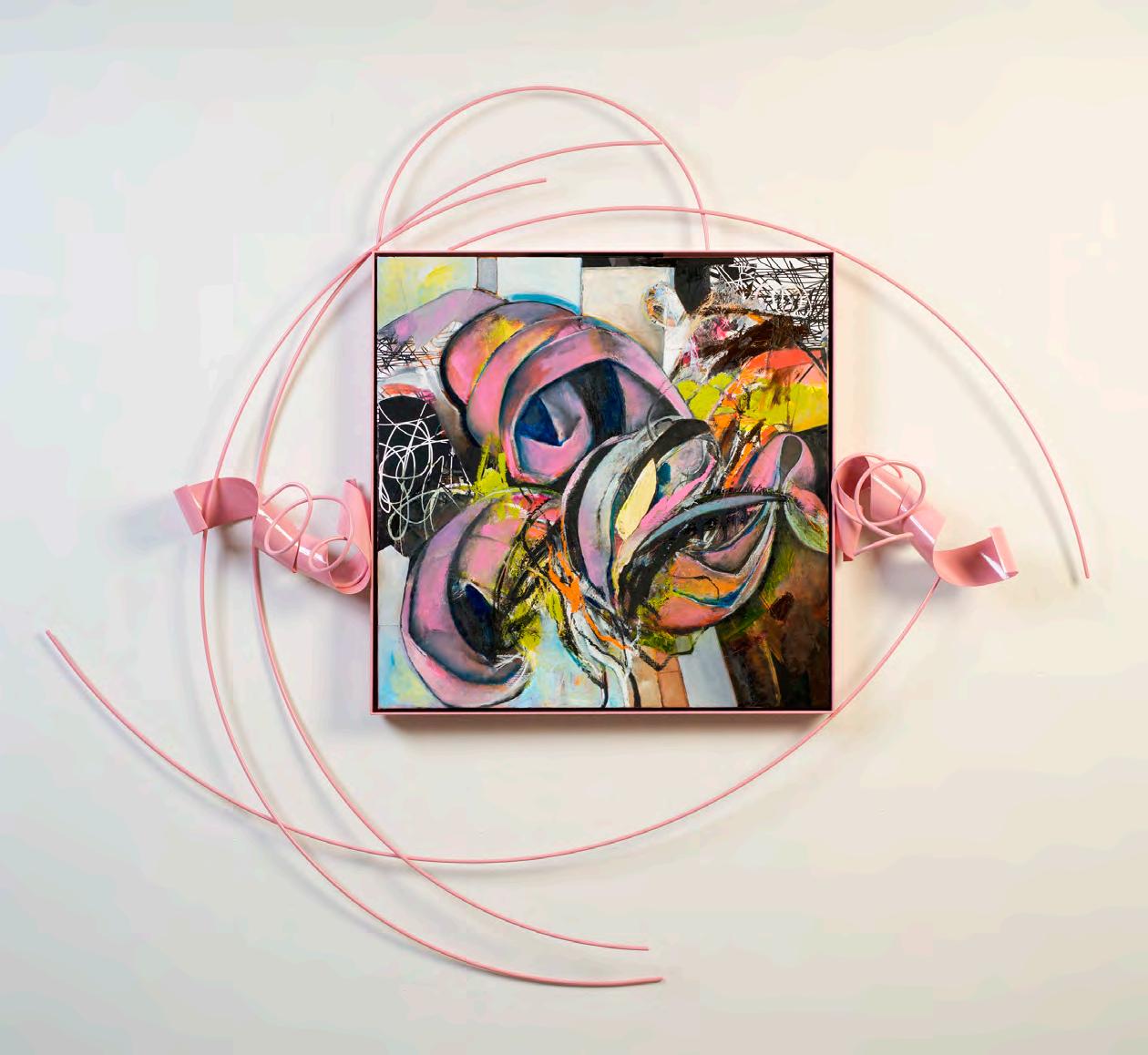

Entanglement Series

Sometimes the steel comes first and sometimes the painting is first.

Sentinel 6, oil and archival print on canvas and powder-coated steel

Sentinel 7, oil and archival print on canvas and powder-coated steel

Sentinel 8, oil and archival print on canvas and powder-coated steel

Sentinel 10, oil and archival print and welded steel

Entanglements

BY PETER FRANK

In particle physics, “entanglements” are interrelations between two widely separated particles – particles whose great distance from one another, in fact, would make such interrelations impossible in the finite universe postulated by Albert Einstein. A dubious Einstein referred to such entanglements, long postulated by quantum physicists, as “spooky actions at a distance.” But they were definitively proven by experiments conducted as late as last year. The idea that such a metaphorical, even poetic, condition could exist in the physical world strongly appeals to Thoman, who has devised a series of works combining two and three-dimensional elements under this rubric.

The Entanglements literalize the sense of the “tangled” while embodying the “spooky action at a distance,” creating a kind of push-and-pull between forms and gestures. The looping lines that comprise both the painted elements and the sculpted seem the very essence of “entanglement.” But it is a very coherent kind of tangle, one in which the painted line segues effortlessly into the sculpted, almost as if a sculptor’s drawings were turning into sculpture by themselves. The painted part of each “Entanglement” roils and fulminates on canvas, confined by the limits of the picture plane, but then seems to break free and fly into the air – like a photon hurtling away from its twin while retaining all the same characteristics, if embodied differently. Thoman’s formulations even include a subtle mirroring of on-canvas compositions by the “twinned” sculptural factors.

The “Tangled Witness Unseen” series manifests the concept of entanglement somewhat differently. Here, the painted and drawn elements, evincing the

physicality of Thoman’s hand, find their contrasting doppelgänger not in three-dimensional forms but in the hard, mechanical scumble of computer-generated lines. Thoman tucks these brittle black loops and meshes behind the quasi-floral, but also highly linear, images she paints and draws. She regards this contrast as giving form to another kind of metaphor, not physical or scientific so much as social and humanistic. As she writes, “Our brain has the ability to both remember and forget, creating a balancing act. I call this the tangled web of seeing.”

— Peter Frank

Entanglement 9, oil on canvas and welded steel

Entanglement 3, oil on canvas and welded steel

Entanglement 4, oil on canvas and welded steel

Entanglement 1, oil on canvas and welded steel

Entanglement 8, oil on canvas and welded steel

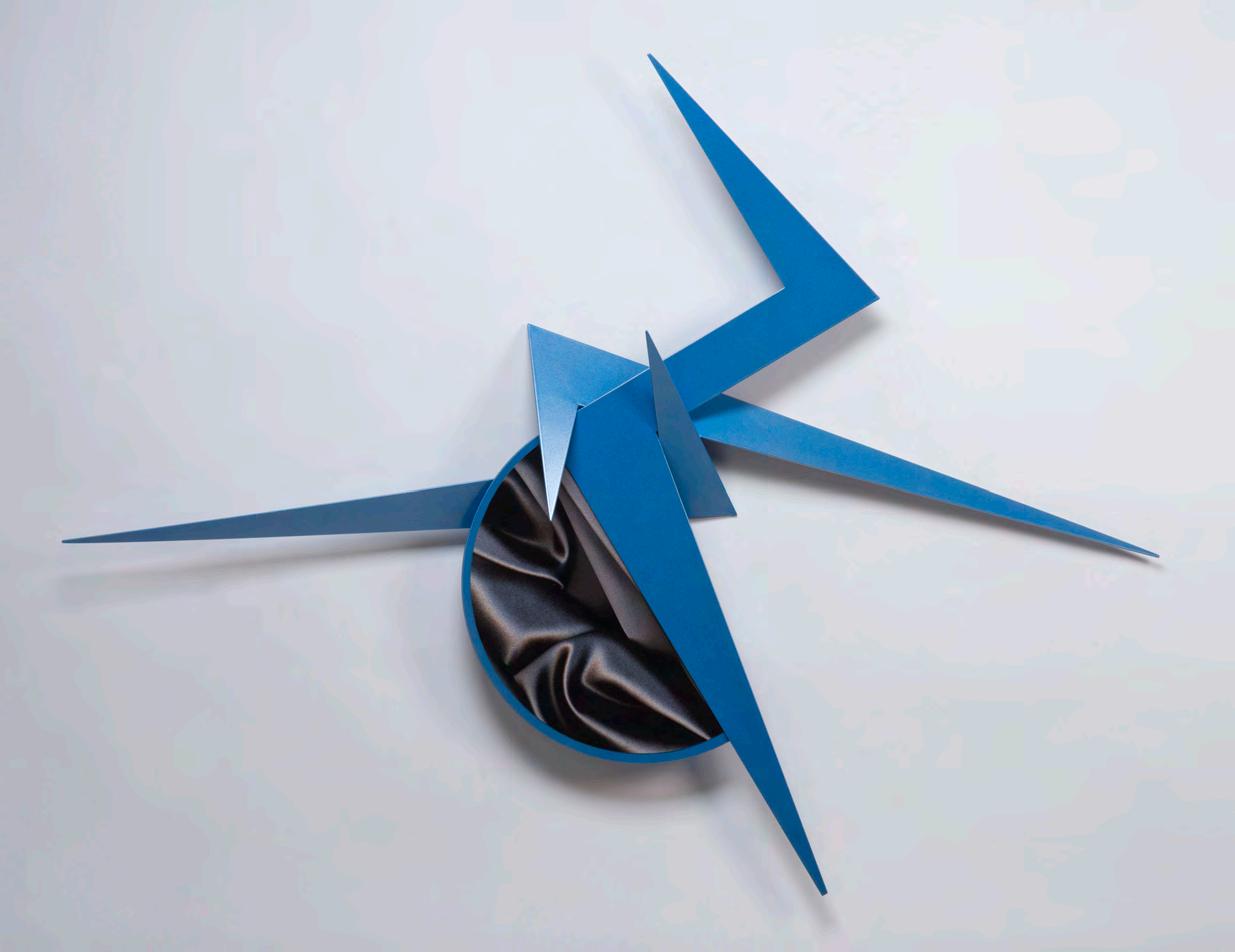

Love From Afar Series

Sometimes we love better from a distance.

Touching Ground 3, powder-coated steel and oil

Ground 1, powder-coated steel and oil

Touching Ground 2, powder-coated steel and oil

COVID and BEYOND

Grill Revisited Series

Slowly opening up from two years of COVID lockdown, I found a neon-orange liquid paint, unused, in my studio. It seemed the perfect metaphor for beginning to blossom.

Revisitation Series

Fully reworked canvases. After COVID, a gestural mark hatched out.

Gist Of It Series

Folds are never far from my work.

Revisited 6, mixed-media on paper

Revisited 11, mixed-media on paper

Revisited 8, mixed-media on paper

Revisited 10, mixed-media on paper

Grill Revisited 9, mixed-media on paper

Grill Revisited 2, mixed-media on paper

One-Wing Angel Series

A “body” between two paintings. An image I’d had about 35 years ago but was unable to bring forth until now. More of these to come.

After titling this series, One-Wing Angels, I encountered a wonderfully appropriate quote by Luciano De Crescenzo - “We are each of us angels with only one wing, and we can only fly by embracing one another.”

As devoted as I am to a stance of, “on the other hand…”, a friend mentioned that a one-winged angel alone would end up flying in circles. This makes me laugh.

A Visual Journey of 40 Years

BY JAN WURM

Moving through time, through the days and years and decades of long and fertile growth, Kim Thoman has led an art practice yielding vibrant images and shape-shifting forms.

To see her earliest paintings alongside her mature graphic work is to witness the seeds of an evolution. Already in her images of graphic figures grappling with womanhood, there is a centrifugal force whirling in a field both reductive and exuberantly patterned. It is that insistent mark that delineates, re-enforces, and then again, reasserts itself.

For a while Thoman suppressed the mark in service to a unified narrative, though it still found a way to persist with its energies lashing the surface. This mark rebounded like a coiled spring. With this propulsive force, the mark took on a physical presence asserting all the power and strength of the arm, the entire body. Though the hand of the artist can be recognized and noted just as the voice, in the work of Kim Thoman it is the whole artist stepping into the work. The length of the stroke, the speed of the directional shift, and the layering repetition – all of these echo the physicality of the artist’s practice.

The primacy of line in the mature work remains unchallenged: unchallenged by color, unchallenged by form, and unchallenged by texture. This is not to say that these fundamental elements do not occupy the artist – they certainly do and visibly animate the artwork. Still, whether painted or drawn or collaged, the line is the beating heart of the artwork.

A reductive palette of black and grey tones allows the pointed pinks – flesh, mauve, ruby, peach – to keep the human alive yet locked away. Cloaked or covered, persistently peeking through, the origins of these visual journeys root the image

to its genesis. In filigree, the activated surface carries an agitation that never detaches, that always summons and reconnects with the inner life.

Even as Thoman takes metal to task – through all the twists and turns the line still dominates to hold, contain, direct, and demand. There is a demand to look, come close, but not too close. The hard and cold structure extends, leaps, and taunts us with the promise of the soft and voluptuous just beyond.

— Jan Wurm

Afterword

BY MARY PACIOS

In the 1970s, when Kim Thoman, a ceramics student sitting in an art history class, saw splashed upon the screen a slide of a Crucifix painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Kim said her immediate thought was how interesting. But I think the 16th century painting was more than just interesting to Kim; that the image touched Kim in a much deeper, intuitive level. Kim focused on the central figure, Christ on the cross with his loin cloth unfolding, flowing in the unseen wind. Kim said a question popped into her head. Why? Why was the drapery unfurled like that? It wasn’t natural, it wasn’t normal.

If all of Kim’s paintings were laid side by side in chronological order, with one painting leading to the next, the continuity of her quest to answer the question provoked by Lucas Cranach the Elder would be laid bare. As Kim explored and tried to resolve her concern with duality, Cranach’s hidden influence would manifest itself, symbolically, growing stronger, changing form, sometimes almost obliterated, but always there, finally reaching a complete transformation in her OneWing Angel Series.

May of 2023, Kim Thoman and I sat in her studio, discussing the drafts of her catalog. We would burst into laughter every time I pointed out the often obscured or hidden drapery in her pieces. We had known each other for about 40 years, meeting in the 1980s when we both had live-work spaces in the Glascock Building near the Oakland Estuary. Seeing the Cranach image for the first time in the catalog, a whole new way of viewing Kim’s work hit me. I could write pages explaining my new awareness – the connection between two artists 500-years apart, the forces that drove them, but I think it is more exciting for viewers to reach their own conclusions. And so, I invite you to again wander through Kim’s catalog and view her work through the lens of Lucas Cranach the Elder.

— Mary Pacios

Wrestling by nature, the best

is yet to come...

A word of gratitude for the many many art students I have worked with over the years. They taught me how to teach. I was thrilled by their unique creative expressions while I hammered home the magic of composition.

Chronology

Born 1949, Lincoln, Nebraska

Studio: Emeryville, California

EDUCATION

University of California, Davis, California, 1966-68

University of California, Berkeley, California, BA, 1972

San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, MA, 1979

TEACHING

Merritt College, Oakland, CA, 2000-2013

Berkeley City College, Berkeley, CA, 1980-2000

California College of Arts, Extension Program, Oakland, CA, 1981

GRANTS and AWARDS

The Helene Wurlitzer Foundation Residency Grant, Taos, New Mexico, 2007 Vermont Studio Center Residency, Johnson, Vermont, 2003, 2000, 1999

Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Change Grant, New York, New York, 1993

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2024 Sentinels and Saviors, Richmond Art Center, California

2019 Gallery at 48 Natoma, Folsom, California

Natural Dualities, Hardin Center for the Arts, Gadsden, Alabama

Hidden Prints in Motion, San Pablo Art Gallery, San Pablo, California

2018 Equilibrium, Olive Hyde Art Gallery, Fremont, California

Natural Dualities, Goddard Center for Visual Arts, Ardmore, Oklahoma

2016 Natural Dualities, Peninsula Museum of Art, Burlingame, California

2015 The Mendocino Art Center, Mendocino, California

Natural Dualities, Anderson Center for the Arts, Anderson, Indiana

Natural Dualities, Lillian Davis Hogan Galleries, Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota, Winona, Minnesota

2013 Shadravan Gallery, Oakland, California

2010 Monterey Peninsula College Art Gallery, Monterey, California

2009 W Hotel Gallery, San Francisco, California

2008 SFMOMA Artists Gallery, San Francisco, California

Oakopolis Gallery, Oakland, California

2006 California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, California

2005 Stanford Art Spaces, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California

Dream Institute of Northern California, Berkeley, California

2003 Perspective Gallery, Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, Virginia.

1998 Quantum Corporation, Milpitas, California

1997 Gallery of the Center for Psychological Studies, Albany, California

1994 JFK University Art Gallery, Orinda, California

1993 Jung Institute of San Francisco, San Francisco, California California School for Professional Psychology, Alameda, California

1992 Graham and James Law Offices, San Francisco, California

1991 Bank of America World Headquarters, San Francisco, California

1990 SFMOMA Artists Gallery, San Francisco, California

1987 Djurovich Gallery, Sacramento, California

1985 Monterey Peninsula Museum, Monterey, California

1983 Chabot College Art Gallery, Oakland, California

1982 Berkeley Stage Theater, Berkeley, California

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2022 Fresh Coffee and a Fresh Start, Grand Theater for Arts, Tracy, California

2021 All About Women, Marin Society of Arts, Online Exhibition

A Digital Art Salon, San Luis Obispo Museum, San Luis Obispo, California

ConVERGEnce, Marin Museum of Art, Novato, California

35th Emeryville Celebration of the Arts, Emeryville, California

Inspirational Art in Mixed Media, The Healing Power of Art and Artists, (HPAA), Online Exhibition

2020 Rhythmix Cultural Works K Gallery, Alameda, California

The Spirit of Resilience, The Healing Power of Art, NY, NY. Award

2019 34th Emeryville Celebration of the Arts, Emeryville, California

2018 The Breakfast Group: Liberty Arts Gallery, Yreka, California

Generation, UC Berkeley Art Alumni Exhibition, Berkeley, California

Out of Darkness, Light, Santa Clara Exhibition, Santa Clara, California

2017 A Sculpture Exhibition, Marin Society of Artists, San Rafael, California

Guilty Pleasures, Jen Tough Gallery, Vallejo, California

2016 Printmaking Explored, San Pablo Art Gallery, San Pablo, California

One Plus One, Gray Loft Gallery, Oakland, California

Digital Fabrication Exhibit, Florida State College, Jacksonville, Florida

2015 International Digital Sculpture Exhibition, Sarofim Fine Arts Gallery, Southwestern University, Georgetown, Texas

2014 Adell McMillan Gallery, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon

25th Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium,

Etter-Harbin Alumni Center at the University of Texas in Austin, Texas

Real/Surreal, Sandra Lee Gallery, San Francisco, California

Return of the Thing: Artists and 3D Printing, CCC Gallery, San Pablo, California

The Breakfast Group, Richmond Art Center, Richmond, California

2013 Cherry Center for the Arts, Carmel, California

Uplift, Oakopolis Gallery, Oakland, California

2005 Dayle Dunn Gallery, Half Moon Bay, California

U.C. Berkeley Art Alumni Show, Berkeley, California

Art Concepts Gallery, Walnut Creek, California

Berkeley Art Center, Berkeley, California

Outnumbered: Works On Paper, Jackrabbit Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

2002 Reflections, San Pablo Arts Gallery, San Pablo, California

Contemporary Abstracts, Artisans Gallery, Mill Valley, California

Maxtor Corporation, San Jose, California

2001 Aspect Communications, San Jose, California

3Com Corporation, Santa Clara, California

2000 Synopsys Incorporated, Mountain View, California

1998 Womanscape: Body, Land, Ocean, Urban, Sun Gallery, Hayward, California

1997 Breakthrough Color, Editions Limited Gallery, Indianapolis, Indiana

Spirit of Nature, Diablo Valley College, Pleasant Hill, California

1996 Ahead of the Wave, Iris Arts, Berkeley, California

Zipzap, Online Magazine

Significants, Los Medanos College, Pittsburg, California

ADA: Women and Info Technology, Artemisia Gallery, Chicago, Illinois

1995 The World’s Women On-Line, United Nation 4th World Conference on Women, Beijing, China

Bayfront Gallery, San Francisco, California

1994 Joanne Chappell Gallery, San Francisco, California

1993 Pro Arts Gallery, Annual, Oakland, California

1991 3Com Corporation, Santa Clara, California

1988 Los Medanos College Art Gallery, Pittsburg, California

Pacific Grove Art Center, Pacific Grove, California

Gallery 44, Oakland, California

1987 Pro Arts Gallery, Oakland, California (catalogue).

Lawson Gallery, San Francisco, California

1986 San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery, San Francisco, California

1984 Lawson Gallery, San Francisco, California

Ralph L. Wilson Gallery, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

Berkeley Art Center, Berkeley, California

South of Market Cultural Center, San Francisco, California

1983 Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, Gatlinburg, Tennessee

Richmond Art Center, Richmond, California

Walnut Creek Civic Arts Gallery, Walnut Creek, California

Holy Names College Art Gallery, Oakland, California

1982 Coos Art Museum, Coos Bay, Oregon

Creative Growth Gallery, Oakland, California

1980 Contemporary Artisans Gallery, San Francisco, California

34th Annual San Francisco Arts Festival, San Francisco, California

1979 33rd Annual San Francisco Arts Festival, San Francisco, California

1978 Ligoa Duncan Gallery, New York, New York.

1977 Richmond Art Center, Richmond, California

OTHER ART RELATED EMPLOYMENT

Juror: RISE, Cal State East Bay Art Gallery, Student Show, Hayward, CA, 2018

Curator: Ruth and Me, Eddie Rhodes Gallery, CCC Gallery, San Pablo, CA, 2017

Juror: Mendocino Art Center Membership Juried Exhibition, Mendocino, CA, 2016

Curator: The Thing: Artists Use 3D Printing, CCC Gallery, San Pablo, CA, 2014

Juror: Oakland Art Association Exhibition, Oakland, CA, 2010

Slide Lecture: Sustaining A Creative Life, Rotary Club, Oakland, CA, 2010

Slide Lecture: California Institute for Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, 2006

Juror: Print and Video Festival, Berkeley City College, Berkeley, CA, 2005

Juror: Los Medanos Student Art Show, 2000, Los Medanos Gallery, Pittsburg, CA, 2000

Juror: Printmaking: People and Process, California Society of Printmakers, CA, 1997

Faculty Advisor: Milvia Street Art Magazine, Berkeley City College, CA, 1995-97

Juror: Ohlone College Art Student League Competition, Fremont, CA, 1995

Slide Lecture: Berkeley Art Center, Berkeley, CA, 1994

Slide Lecture: JFK University, Orinda, CA, 1994

Contributing Writer: “Art In Focus”, High School Textbook, Glencoe Publishing, CA, 1992

Contributing Writer: “Exploring Art”, Jr. High Textbook, Glencoe Publishing, CA, 1990

Art Department Chair, Berkeley City College, Berkeley, CA, 1990-92

Juror: 1985 Army Artist Contest, Presidio Army Base, San Francisco, CA, 1985

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Villagelife.com, The Gallery at 48 Natoma: “Pushing the Boundaries”, by S. Laird, Sep. 2019.

The San Mateo Daily Journal, “Natural Duality” by Susan Cohn, July 29, 2016. Mendocino Arts Magazine, 2015-16, by Michael Potts.

3DPrint.com, “What Things May Come: 3D Printing” by M. Matisons, February, 2015.

3DPrint.com, “Kim Thoman’s 3D Printed Sculptures” by M. Matisons, January, 23, 2015.

East Bay Express, Oakland, California, February 2008, “Drastic Park” by DeWitt Cheng. Tempo: Total Arts Gallery Review. Taos News, Taos, New Mexico, October 2007.

Palo Alto Weekly, Palo Alto, California, August 2005, “Art: Stanford Art Spaces.”

Oakland Tribune, Oakland, California, August 2005, “Art on Paper” by Monique Beeler. The Forum, California Community Colleges Publication, Sacramento, California, 1997.

TSA, Alameda, California, October 1993, “Unlikely Collision: Art at CSPP” by R. Whittaker.

Pacific Grove Monarch, California, October 1988, “Art Notes” by S. Colburn.

Contra Costa Times, California, May 1988, “Los Medanos” by Bonnie Ferguson. San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, California, January 1987, by Al Morch.

Oakland Tribune, California, December 1983, “Art Show Runs the Gamut” by C. Shere.

Oakland Tribune, California, August 1983, “Crowded Talented Show” by C. Shere.

Contra Costa Times, California, August 1983, Walnut Creek Exhibit, by Carol Fowler.

Numerous works in public and private collections.

website: www.kimthoman.com instagram.com/kim.thoman email: kim@kimthoman.com

Contributors

PETER FRANK is Associate editor for Visual Art Source and former Senior Curator at the Riverside (CA) Art Museum, He has served as Editor of THEmagazine Los Angeles and Visions Art Quarterly and as critic for the Huffington Post, Angeleno magazine, and the L.A. Weekly. Frank was born in 1950 in New York, where he wrote art criticism for The Village Voice and The SoHo Weekly News. He has written several books and numerous exhibition catalogues. Over his fifty-year career Frank has also organized dozens of theme, survey, and solo exhibitions for galleries and institutions in America and Europe.

ANN LANDI has been an art journalist for nearly 30 years, writing for publications like The Wall Street Journal, Smithsonian, The New York Times, Sculpture magazine and others. For more than two decades she was a contributing editor of ARTnews, and for six years the editor and publisher of Vasari21.com, a website for an audience of about 2,500 artists. She is the author of the four-volume Schirmer Encyclopedia of Art, and holds degrees in art history from Princeton and Columbia universities.

JAN WURM is an artist, educator, and curator engaged in expanding the community forum for contemporary art dialogue. Currently dividing her time between Berkeley and L.A., Wurm has lived in California and Europe honing an eye for social patterns and conventions. With one hand painting, the other drawing, Wurm examines daily encounters revealing contemporary culture. Infused with warmth, humor, and energetic line, her internationally exhibited work is in collections including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, New York Public Library Print Collection, Archiv Verein der Berliner Künstlerinnen, and Universität für angewandte Kunst in Vienna.

MARA BLACKWOOD worked at Xanadu Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona for 5 years, beginning in 2016. As their Art Communication Specialist, she wrote artist’s biographies, promotional material, and marketing copy, as well as assisted the owner, Jason Horejs with special projects.

MARY A. PACIOS Mary Pacios, the first single mother of children admitted to the Massachusetts College of Art (Mass Art) as a freshman, earned a BFA (1962). Pacios received her MA from California State University, Stanislaus (1977). The hand-rubbed, large linocuts of Pacios, shown throughout the United States and internationally, have received numerous prizes and awards and have been acquired by several museums. Pacios is the author of two books, Childhood Shadows: The Hidden Story of The Black Dahlia Murder (a New Expanded Edition is scheduled to be published by Talestorm, LLC in 2024), and Memoir of an Unintentional Feminist

ANDREW JURIS is a multimedia artist, musician and filmmaker based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has been Kim’s technical and design assistant since 2010.

ISBN: 979-8-218-40215-0

Copyright 2024

Kim Thoman

Cover Image: Gist Of It 4, mixed-media on canvas 44” x 60” (112 x 152 cm), 2022

Principal Photography Dana Davis

Printed at Edition One Books

If we can take away a moral and social lesson from Kim Thoman’s oeuvre, it is that conflict resolution lies within each of us. Thoman does not think of herself as wiser than the rest of us, only more fortunate by dint of her work with art to have discovered for herself the harmony of the universe. That harmony is not in the propitious alignment of forms and meanings, but in our discovery – or, shall we say, acceptance – of balance between haphazard pairings and contrapositions. Things don’t exist in opposition to other things, but only in balance with them. Finally, Thoman doesn’t resolve conflicts, but reveals their superficiality. At heart, everything is in union.