Literature Review

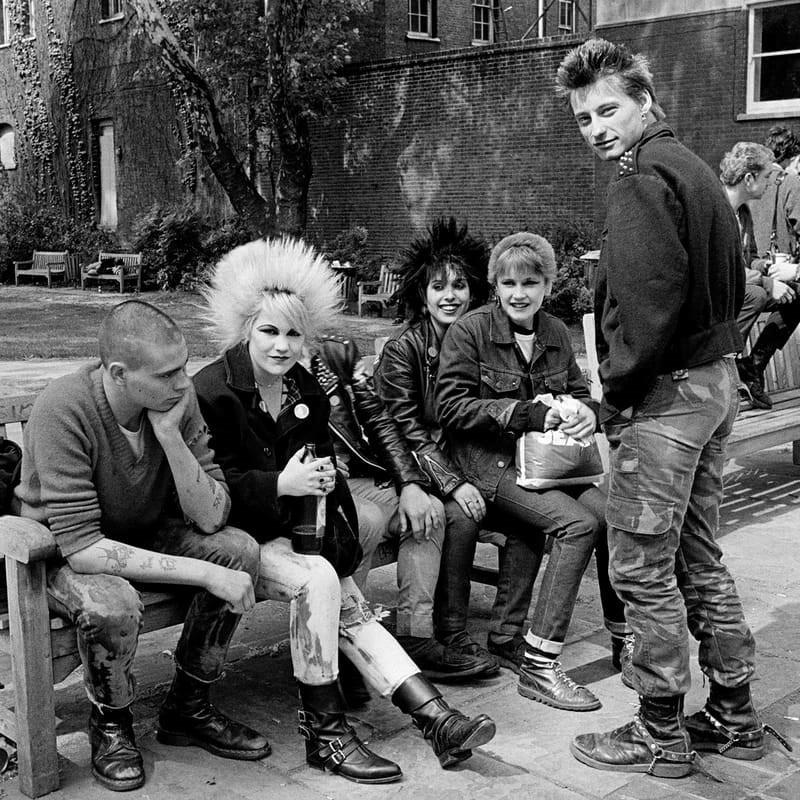

Fig 5

The relationship between fashion and identity has long been explored in cultural studies. Davis (1992) asserts that fashion is a communicative system used to articulate shifting identities and negotiate social belonging. This semiotic function of fashion allows wearers to send messages about their social, political, and cultural affiliations. However, as Hebdige (1997) notes, fashion is not simply clothing—it is a cultural phenomenon shaped by institutions, media, and economic systems. Thus, identity in fashion is both personal and institutional, emerging within broader structures of power and commerce.

Subcultures and symbolic resistance

Subcultures historically used fashion as a form of resistance, distinguishing themselves from the mainstream through distinctive dress, music, and ideology (Crane, 2000). Punk, goth, hip-hop, and grunge are examples of style-based subcultures that emerged with specific socio-political

motivations and anti-consumerist sentiments. According to Craik (2009), these subcultures constructed “symbolic boundaries” through clothing choices, positioning themselves against dominant fashion systems.

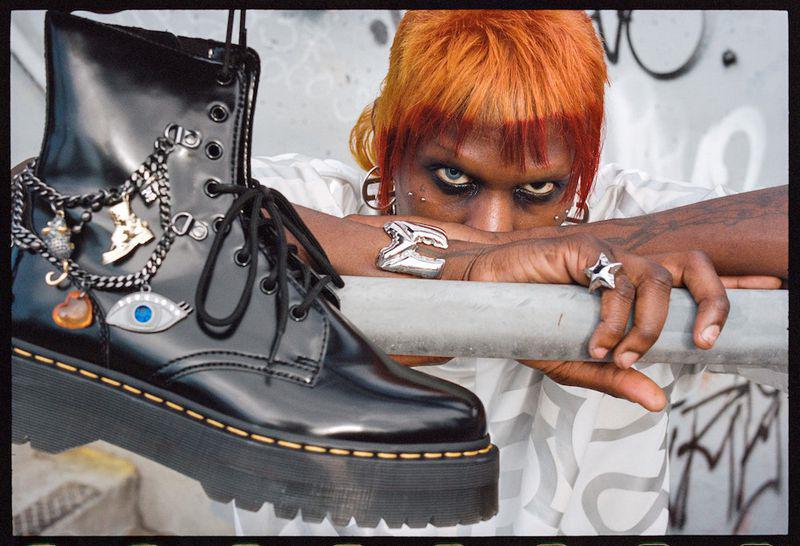

However, these expressions of resistance have increasingly been appropriated by fashion brands. Arvidsson (2006) discusses how brands mine cultural materials to generate symbolic value, effectively neutralising the radical origins of subcultural styles. This process transforms anti-mainstream expressions into profitable commodities devoid of their original meaning.

Rise of brand culture

In today’s fashion landscape, brands no longer just sell products—they sell identities. Banet-Weiser (2012) argues that authenticity itself has become a branding strategy. Fashion brands construct emotionally resonant narratives and offer curated lifestyles that appeal to consumers’ desire for 9.

individuality and belonging. This shift marks the emergence of “brand culture,” where identity is a consumable experience mediated through marketing and digital culture.

Moore and Birtwistle (2004) provide a clear example through their study of Burberry’s transformation. Once a symbol of British tradition, Burberry rebranded itself by appropriating street "Chav" aesthetics, aligning with the youth to re-enter relevance after ditching the iconic check print. This deliberate co-option of subcultural identity illustrates how branding strategies appropriate cultural symbols for economic gain.

Social media and aesthetic performance

Social media has accelerated the commodification of identity by fostering fast-moving, aesthetic-centered micro-trends. Trends such as “blokette-core,” “clean girl,” “mob wife aesthetic,” and “office siren” dominate TikTok and Instagram, promoting highly visual lifestyles rather than coherent ideologies. As highlighted by Vogue Business (2025), micro-trends are rapidly

giving way to “vibes”—fluid, consumable, and fleeting identities that align neatly with marketing goals.

Kaiser (2012) describes this as a form of “aesthetic labor,” where individuals are encouraged to visually perform identity through self-curated digital content. Yet, these performances are often shaped by brand influence and algorithmic visibility, limiting their authenticity. The result is a homogenised culture of visual sameness masquerading as diversity.

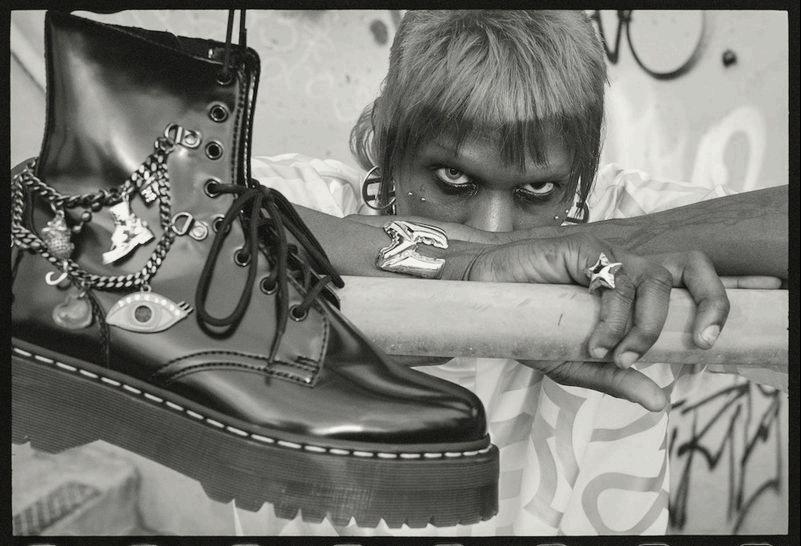

Fig 6

Greenwashing authenticity and values

Even sustainability and anti-consumerist ideologies are being co-opted by brands. Brydges and Hanlon (2020) critique how sustainability has been commodified, arguing that conscious consumption is often marketed without meaningful systemic change. Brands use language, imagery, and influencer partnerships to promote a façade of ethical fashion while continuing exploitative practices.

This greenwashing parallels the commodification of subcultural authenticity. Brands appropriate not just the look of subcultures but also their values —repackaging rebellion, individuality, and anti-establishment ideals into curated campaigns. As Tseëlon (2001) argues, marketing has the power to neutralise meaning, creating sanitised versions of complex cultural phenomena.

Fig 7

Methodology

For this research, I will adopt a qualitative approach to explore how fashion consumers perceive and respond to the commodification of identity through branding. A qualitative methodology is best suited to investigate social meaning, personal narratives, and cultural interpretation (Creswell, 2007), all of which are central to understanding subcultural fashion and self-expression.

I will use ethnographic strategy, combining both offline and online research tools to study how branded fashion identities are shaped, communicated, and internalised. A key component of this strategy is netnography, which I will use to observe and analyse digital communities and content on platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Pinterest. These platforms are central to the rise of aesthetic-driven micro-trends and offer insight into how identity is visually performed, consumed, and shaped by brands and algorithms.

In addition to online observation, I will conduct one-on-one interviews and carry out focus groups with fashion consumers that align themselves with a community/ culture. These will help me understand how participants connect with subcultural style, interpret branded content, and navigate ideas of authenticity in their personal fashion choices.

To analyse the qualitative data, I will use thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) to identify recurring patterns, tensions, and emerging narratives. I will also pay close attention to semiotic elements—including language, visuals, and symbols—that contribute to the construction of branded identity narratives (De Saussure, 1966). This methodology will be used to inform a creative output.

Fig 9

Rawat, K. (2025) 'CTRL+ALT Tactical plan.' Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham

SGen Z and younger millennials place high value on authenticity, individuality, and ethical consumption. However, their modes of expression are heavily influenced by online culture and branding, creating a tension between genuine identity exploration and curated self-presentation.

TBrands now build identities through interactive digital campaigns, influencer partnerships, and curated narratives, which blend seamlessly into consumers’ online experiences.

EWhile slow fashion aligns with anti-consumerist ethics, it often comes with a higher price point, making it less accessible economically. This creates a tension between ideological alignment and accessibility.

Many brands use environmental narratives as part of their identity without backing them up with meaningful change, contributing to greenwashing.

PEDiscussions around identity politics and cultural ownership influence how subcultures are represented in fashion. Brands that misrepresent or exploit cultural identity could face public and political backlash.

References

• Arvidsson, A. (2006) Brands: Meaning and Value in Media Culture. London: Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203640067

• Banet-Weiser, S. (2012) Authentic™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: NYU Press. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292845589_Authentic_The_p olitics_of_ambivalence_in_a_brand_culture

• Brydges, T. and Hanlon, M. (2020) ‘Selling sustainability: The commodification of conscious consumption in fashion’, Geoforum, 116, pp. 22–29. Avaiilable at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2068225

• Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), pp.77–101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

• Craik, J. (2009) Fashion: The Key Concepts. Oxford: Berg. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385804770_Fashion_The_Key_ Concepts

• Crane, D. (2000) Fashion and its social agendas: class, gender, and identity in clothing. Chicago Press. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vphcHONAXmwC&lpg=PP11&dq= identity%20and%20fashion&lr&pg=PP6#v=onepage&q&f=true

• Davis, F. (1992) Fashion, Culture, and Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr&id=p-KvoXTYtVoC

• Creswell, J.W. (2007) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

• De Saussure, Ferdinand. (1966). Course in General Linguistics (Edited by Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye, Translated by Wade Baskin). New York, Toronto, London: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

• Farmiloe, I. (2023) Are we living through a great subcultural renaissance? Dazed Digital. [online] Available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/61507/1/are-we-livingthrough-a-great-subcultural-renaissance

• Hebdige, D., (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. London: Routledge. Available at: https://www.erikclabaugh.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/18189984 7-Subculture.pdf

• Kaiser, S.B. and Green, D.N., 2022. Fashion and cultural studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=vphcHONAXmwC

• Kawamura, Y. (2005) Fashion-ology: An Introduction to Fashion Studies. Oxford: Berg. Available at:

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=muu-EAAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&ots=WN wrCVv1Et&dq=Kawamura%2C%20Y.%20(2005)%20Fashion-ology%3A%20&l r&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

• Ross, J. and Harradine, R. (2011), "Fashion value brands: the relationship between identity and image", Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 306-325. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021111151914

• Schofield, K. (2023) The death of subculture: Its TikTokification. Medium. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@katieschofield126/the-death-of-subculture-its-tiktoki fication-002ba0084f9e

• Schiele, K. and Venkatesh, A. (2016) ‘Regaining control through reclamation: how consumption subcultures preserve meaning and group identity after commodification’, Consumption Markets & Culture, 19(5), pp. 427–450. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2015.1135797.

• Titton, M. (2015) ‘Fashionable Personae: Self-identity and Enactments of Fashion Narratives in Fashion Blogs’, Fashion Theory, 19(2), pp. 201–220. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2752/175174115X14168357992391

• Tseëlon, E., (2023) Ethical fashion and fiction. In: A. Groppo and A. Rocamora, eds. Routledge Companion to Fashion Studies. London: Routledge. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003263753-17/e thical-fashion-fiction-efrat-tse%C3%ABlon

• Toomey, A. (2023) TikTok's trend cycle is changing the meaning of subculture. W Magazine. [online] Available at: https://www.wmagazine.com/fashion/tiktok-fashion-trends-subcultures-go ths

• Vogue Business (2025) ‘Micro-trends are dead. Long live the vibe.’

Available at: https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/fashion/micro-trends-are-dead-lon g-live-the-vibe (Accessed: 18 April 2025).

• Rawat, K. (2025) 'CTRL+ALT Tactical plan.' Nottingham

Image References

Rawat, K. (2025) CTRL+ALT shoot [photograph]

Schlossberg, M., 2016. R13's Spring 2017 Collection Featured a Model Dressed as Donald Trump. Fashionista. [online] 12 Sept. Available at: https://fashionista.com/2016/09/r13-spring-201 7-trump [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Coeval Magazine, 2024. Rick Owens SS25 Womenswear. [online] Coeval Magazine. Available at: https://www.coeval-magazine.com/coeval/r ick-owens-ss25-womens [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Kovarik, P./AFP/Ritzau Scanpix, n.d. Vivienne Westwood. [image] Available at: https://lex.dk/Vivienne_Westwood [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Fashion Law Journal, 2023. The punk movement: Rebellion and subversion in fashion. [online] Available at: https://fashionlawjournal.com/the-punk-mov ement-rebellion-and-subversion-in-fashion/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

BBC News, 2017. Why subcultures matter. [image] Available at:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainmen t-arts-41818169 [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Models.com, 2023. Dr. Martens x Marc Jacobs Collaboration featuring Yves Tumor. [image] Available at:

https://models.com/work/dr-martens-dr-ma rtens-x-marc-jacobs-collaboration-featuring -yves-tumor [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Bikerringshop, 2023. Chrome Hearts Jewelry and its Impact on Fashion. [online]

Available at:

https://www.bikerringshop.com/en-gb/blo gs/articles/chrome-hearts-jewelry-and-its-i mpact-on-fashion [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].

Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, 2022. The Invention of the Iconic Vans Skateboarding Shoe. [online]

Smithsonian Institution. Available at: https://invention.si.edu/invention-stories/inv ention-iconic-vans-skateboarding-shoe [Accessed 20 Apr. 2025].