A Place for Us

RECLAIMING IDENTITY AND AGENCY IN TRANSITIONAL SPACES

For my support system—Mom, Dad, Grandma, Azhar, Raisa and Kunza.

For the legacy we carry through our matriarchs— Mama Sal, Grandma, and the generations before.

Thank you.

“I know it’s not fair. But it’s our job to make it better.”

My mom, 2007

Growing up in Trinidad, I learned that stories aren’t just told—they’re lived experiences breathed into the spaces we inhabit. As a designer, I aim to use this understanding to craft experiences that resonate deeply with people, fostering a sense of belonging and well-being. I believe in the transformative power of spaces to reshape human experiences, inspire connections, and create lasting memories.

Trinidad’s vibrant intersections of cultures, materials, and traditions taught me how spaces act as agents of connection to one’s identity and history. There, courtyards hosted family storytelling, street corners transformed into impromptu soccer matches, and verandas became arenas for evening card games of “Truff Charles.” Kitchens and gardens were not merely functional spaces but workshops where recipes and herbal knowledge were passed down through generations.

These rituals—embedded in architecture—revealed design’s power to nurture cultural identity. My journey to find belonging after moving to the United States has instilled in me a relentless pursuit to create environments that enable others to discover their agency and sense of community while

in transit. In today’s divisive climate, my work deliberately challenges the status quo by designing spaces that celebrate local culture and heritage, fostering meaningful human connections across diverse experiences.

My practice stands firmly on three non-negotiable pillars: inclusivity, sustainability, and social impact. Beauty and thoughtful design must be accessible to all, regardless of background or ability—a conviction that drives me to actively confront biases while prioritizing local, environmentally conscious materials.

My design process begins with deep listening—to communities, materials, and history. I immerse myself in understanding not just how a space will function today but also how it will evolve and serve generations to come. Through curiosity-driven research and community engagement, each project becomes an opportunity to weave together cultural narratives with environmental responsibility, creating spaces that unite rather than divide.

Through my work, I’m committed to amplifying and honoring tradition, serving communities, and pioneering sustainable solutions for our shared future. My journey from Trinidad to the United States has opened a unique lens through which I view design. I channel this understanding into creating environments for all because, as my mother taught me, it’s our job to make them better.

CHAPTER TWO

In an era marked by unprecedented global displacement, the concept of “home” has become increasingly complex and contested. This thesis investigates how displaced individuals use homemaking practices, vernacular materials, and everyday objects to reclaim identity and create belonging within transition spaces. Moving beyond the metaphor of the waiting room, this research reconceives transitional spaces as a network of connected threshold environments—neither entirely temporary nor permanent, neither completely public nor private—where identities form and transform.

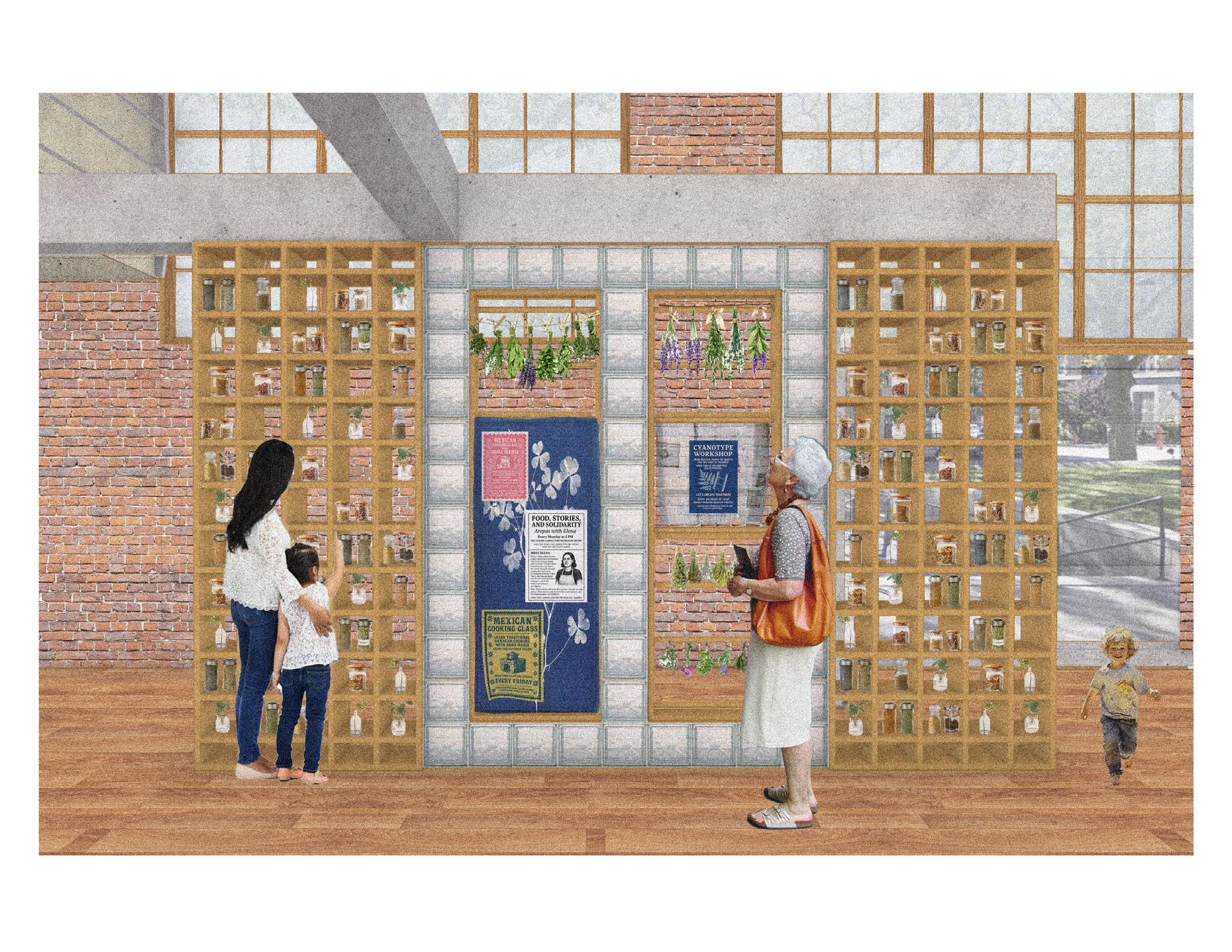

Using the Sunset Park Recreation Center—a once emergency shelter for migrants—as its primary case study, this thesis addresses the critical gap in migrant support during years 2-5 after arrival in the United States, when institutional support often diminishes precisely as needs shift from survival to belonging. Through programmatic interventions including community kitchens, sanctuary spaces, and memorialization areas, this work demonstrates how threshold spaces can transform bureaucratic processing environments into sites of cultural continuity, economic opportunity, and community formation.

Drawing on decolonial theory and participatory methods—centered around a collaborative cookbook project and complemented by photography and community-generated archives—this thesis centers migrants as

knowledge producers rather than subjects. The research examines how communal spaces foster spontaneous homemaking, how waiting becomes an opportunity for belonging, and how displaced individuals reclaim transitional interiors through rituals, objects, and spirituality to find joy and agency in their identity.

By highlighting the invisible emotional labor involved in maintaining cultural continuity, this work reframes waiting not as passive endurance but as active community formation. The proposed network for Sunset Park Recreation Center creates physical infrastructure for collective resilience, recognizing that displacement is an individual challenge and a shared experience requiring collaborative solutions. Through living archives like community cookbooks and participatory design processes, this thesis advances interior design as a decolonial practice that values experiential knowledge alongside professional expertise, transforming transitional spaces into thresholds of possibility where belonging emerges through collective memory-making, cultural production, and shared agency. migrants as knowledge producers rather than subjects. The research examines how communal spaces foster spontaneous homemaking, how waiting becomes an opportunity for belonging, and how displaced individuals reclaim transitional interiors through rituals, objects, and spirituality to find joy and agency in their identity.

TheDesign Methodology positions migrants as knowledge producers rather than research subjects. It uses decolonial design principles with participatory methods to recognize lived experience as expertise.

This approach centers on understanding displacement not as a static condition but as a complex temporal experience requiring both immediate interventions and sustained infrastructure for community resilience. The design process ensures that those most affected by displacement actively shape the outcomes through the use of food and photography as primary methods of engagement and knowledge production.

This year-long collaborative cookbook project engaged migrants in documenting culinary traditions, adaptation strategies, and the social significance of food in their displacement experience. Participants contributed recipes, food memories, and insights on how cooking creates a sense of home in transitional spaces. These stories directly informed kitchen design elements and programming decisions, prioritizing flexible configurations that support both cultural preservation and economic opportunity.

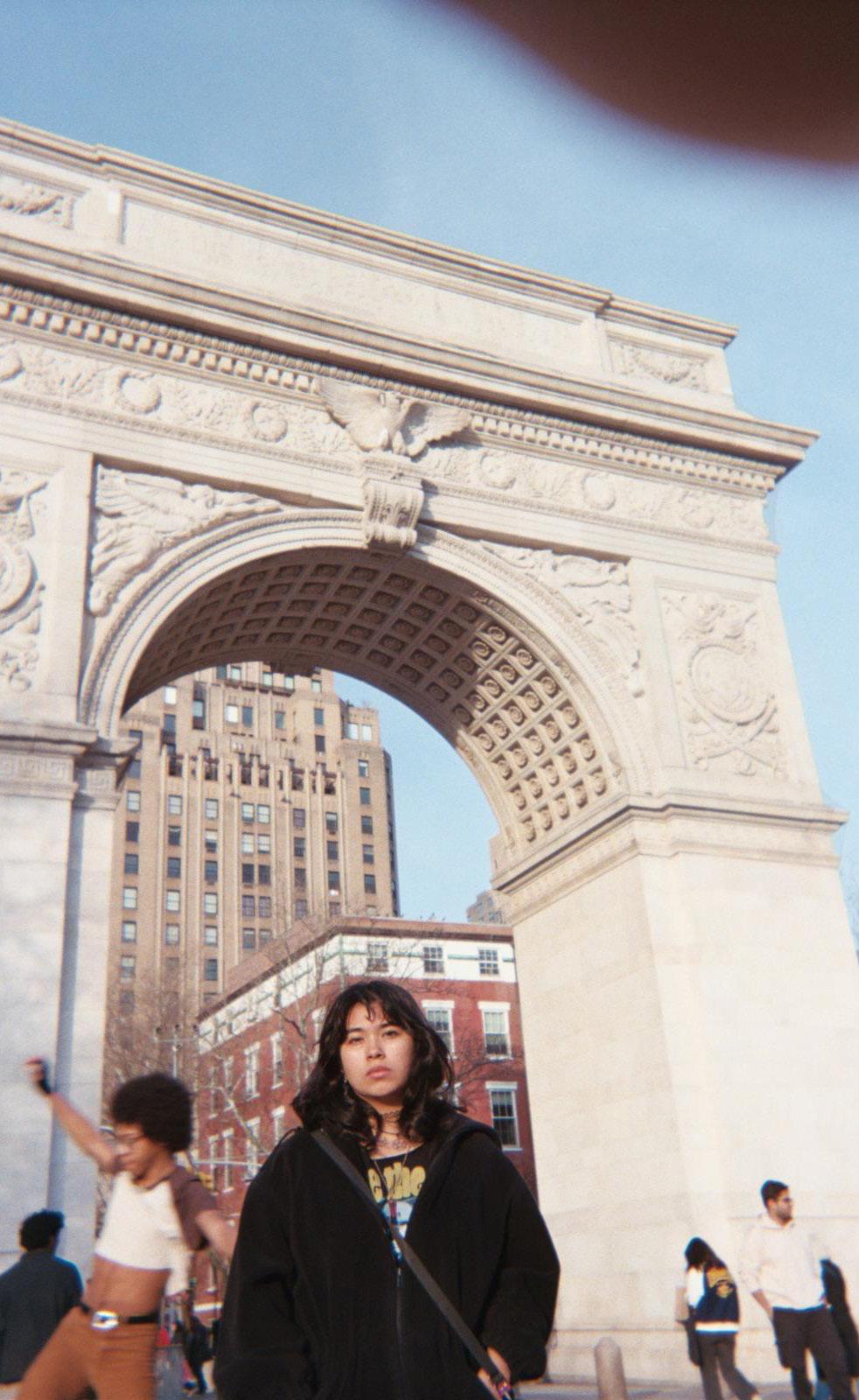

This collaborative photography project provided participants with cameras to document their spatial experiences and daily navigations. The resulting images revealed patterns of use, barriers to access, and informal gathering spaces that might otherwise remain invisible to conventional architectural analysis. These visual narratives directly shaped the design of threshold spaces, highlighting where privacy, visibility, and community connection are most needed.

• Collaborative Documentation: Working with community members to capture spatial experiences through disposable cameras, walking interviews, and informal gatherings

• Embodied Knowledge: Prioritizing lived experience over abstracted data, recognizing that displacement knowledge exists primarily in bodies, memories, and daily practices, as many statistics pertaining to displacement do not accurately reflect the demographic

• Temporal Awareness: Documenting how spaces transform across different times of day, days of the week, and seasons to capture the full spectrum of use

Threshold Analysis examines spaces that exist between public/private, permanent/temporary, and institutional/informal realms. This analysis identifies moments of spatial convergence where different uses and users overlap, documenting how thresholds function as sites of both conflict and possibility.

Patterns of Adaptation records how communities modify standard infrastructure to meet specific cultural and social needs. By analyzing spontaneous interventions as expressions of spatial agency and resistance, this framework helps identify transferable design strategies that emerge from community adaptations.

Circulation Studies map movement patterns that reveal how displaced people navigate between essential services. These studies identify physical and perceived barriers that fragment the migrant experience while documenting moments of pause, rest, and gathering within circulation networks.

Design Process

Proposed Implementation Strategy

• Phasing interventions to allow for adaptation and community input throughout the process

• Building capacity within the community to maintain and evolve the spaces over time

• Creating documentation systems that capture how spaces transform with use

Ethical Framework

This methodology explicitly rejects the extractive tendencies of traditional research and design practices. Instead, it:

• Acknowledges the inherent power dynamics in designer-community relationships and the effects of colonialism

• Compensates community members fairly for their knowledge and time

• Creates mechanisms for ongoing community governance of the spaces

• Embraces the unpredictability of collaborative processes

The resulting design interventions prioritize flexibility, layered programming, intuitive communication across language barriers, and carefully balanced visibility/privacy concerns. Each design decision is evaluated based on how it serves those most impacted by displacement, considering both immediate needs and long-term community resilience.

CHAPTER FOUR

Thisresearch positions itself at the intersection of architectural practice, migration studies, and critical theory. It emerges from the understanding that displacement is not merely a physical condition but a complex spatial, temporal, and psychological experience that fundamentally transforms how people relate to space. By examining transitional environments through the lens of multiple critical frameworks, this research challenges conventional approaches to migrant support that often prioritize efficiency and control over agency and belonging.

The project draws from four interrelated theoretical traditions that together illuminate the complex dynamics of space, power, and identity within displacement contexts.

Emerging from 20th-century social movements, feminist critical theory examines systemic power structures and gender dynamics. While pioneers like Simone de Beauvoir laid groundwork for understanding gender as a social construct, contemporary scholars such as bell hooks and Judith Butler have expanded this framework to interrogate intersectional oppression. The theory’s evolution mirrors a crucial shift from Western-

centric feminism to a more inclusive framework that acknowledges diverse experiences of gender oppression.

This research applies feminist critical theory by examining how transitional spaces can either perpetuate or disrupt power hierarchies. The shelter system, often designed with efficiency and surveillance as primary concerns, typically reinforces existing power dynamics—where migrants become passive recipients of aid rather than active agents in their own lives. By contrast, threshold spaces designed through feminist principles acknowledge the deeply personal nature of displacement and prioritize environments where people can reclaim control over their daily practices.

The kitchen spaces in “A Place for Us” particularly embody this feminist approach, recognizing that food preparation is both intimate cultural labor and potential economic empowerment. These spaces reject the binary between domestic work and public engagement, creating instead a permeable threshold where personal cultural practices can become community building and economic opportunity. This approach directly challenges the institutional tendency to separate “basic needs” from cultural expression and economic agency.

Building on post-colonial scholarship by Walter Mignolo, Irene Chang, and Anibal Quijano, decolonized design transcends mere critique to actively reconstruct design practices. Rather than simply opposing colonial influences, it seeks to resurrect and reimagine indigenous design methodologies. The framework examines how vernacular architecture and local craftsmanship embody cultural knowledge systems that preceded colonization. Contemporary manifestations of this approach are evident in social media’s role in cultural preservation, where traditional practices find new platforms for transmission and celebration. This theory fundamentally challenges Western design principles by demonstrating how indigenous materials and methodologies often offer more contextually appropriate and sustainable solutions.

This research applies decolonized design principles by recognizing that displaced communities bring valuable spatial knowledge that often remains invisible to institutional design approaches. The sanctuary spaces in “A Place for Us” exemplify this approach by incorporating elements like jali screens and textile partitions that reference spatial practices from various cultural contexts. These design choices are not simply aesthetic but functional—they create graduated privacy and facilitate non-Western approaches to community formation that don’t rely on rigid separations between public and private.

More fundamentally, the research methodology itself is an exercise in decolonized design—positioning migrants not as subjects to be studied but as knowledge producers whose lived experience constitutes expertise. This inverts the conventional power dynamic where the designer extracts information to develop “solutions” and instead creates a collaborative process where design emerges from shared knowledge production.

Maria S. Giudici’s “Counterplanning from the Kitchen” reconceptualizes domestic space as a site of political and social transformation. This theoretical framework extends beyond conventional architectural concerns to examine how spatial organization reflects and reinforces social relationships. By positioning homemaking as a political act, this theory reveals how domestic design can either perpetuate or challenge existing power structures.

The project applies this framework by recognizing that creating “home” within displacement is both a personal necessity and a political assertion of belonging. The cooking and memorialization spaces in “A Place for Us” particularly engage with homemaking as resistance—they transform institutional environments into spaces where cultural practices can be maintained and adapted. When Elena teaches other women to make arepas with American ingredients, or when Maya helps new arrivals contribute to the community archive, they are engaging in homemaking that transcends domestic boundaries to become community formation.

This approach challenges the temporary/permanent binary often imposed on displaced communities. Rather than treating transitional spaces as a temporary stopgap before “real” homemaking can occur elsewhere, the project recognizes that homemaking happens continuously—not as a final destination but as an ongoing process of creating belonging wherever one is located.

Harum Mukhayer’s innovative framework examines how political borders intersect with cultural continuity. This theory particularly illuminates how communities maintain identity and connection across imposed boundaries. Its application extends beyond literal borders to examine how cultural spaces persist within and despite physical constraints, offering crucial insights for understanding displaced communities’ spatial practices.

This research applies transboundary self-determination to understand how migrants navigate between multiple spatial realities—the physical environment of their current location, the remembered spaces of their origin, and the imagined spaces of their future. The threshold spaces in “A Place for Us” acknowledge this complex navigation by creating environments that support cultural continuity without imposing fixed notions of identity. The herb and seasoning archive, for example, allows residents to maintain sensory connections to homeland while adapting to new contexts.

More broadly, the network approach of the project embodies transboundary thinking by reconceptualizing urban infrastructure as a mesh of interconnected thresholds rather than discrete spaces with fixed functions. This perspective acknowledges that belonging emerges not from isolated interventions but through dynamic constellations of spaces, relationships, and practices that migrants orchestrate across fractured urban landscapes. The project’s distributed system of threshold environments—kitchen, sanctuary, forum, and memorial spaces—creates a network that migrants can navigate according to their specific needs, allowing for both collective solidarity and individual agency. By establishing physical infrastructure for cultural continuity that spans multiple sites and programs, “A Place for

Us” supports forms of self-determination that persist across institutional boundaries and temporal uncertainties. This approach recognizes that displaced communities already create informal networks of support that transcend conventional spatial categorizations—the design simply makes these existing networks more visible, accessible, and resilient.

This project positions itself within ongoing conversations about the ethics of design in contexts of forced displacement. While architectural responses to migration have often focused on emergency shelter or longterm housing, far less attention has been paid to the critical middle period where institutional support diminishes but integration remains distant. By focusing on this gap, the research contributes to an emerging discourse that views displacement not as a temporary crisis but as a structural condition requiring sustained spatial responses.

The project also engages with contemporary critiques of humanitarian design that often pathologize migrants as helpless victims rather than resilient agents. By centering migrant knowledge and agency, “A Place for Us” aligns with scholars and practitioners who advocate for more horizontal approaches to design in contexts of displacement.

The network conception of threshold spaces further contributes to emerging scholarship on urban infrastructure and migration. Rather than treating migrant spaces as exceptional or separate from broader urban systems, this approach examines how transitional environments interface with existing infrastructures and potentially transform them. This perspective suggests that designing for displacement is not merely about accommodating newcomers but about rethinking how cities function for all residents.

In focusing on years 2-5 of the displacement journey, this research addresses a critical gap in both scholarly literature and practical support systems. It recognizes that liminality is not a brief transition but often a prolonged state that requires its own spatial consideration. By developing design strategies specifically for this extended threshold period, the project

contributes to both theoretical understanding of liminality and practical approaches to supporting those who inhabit it.

The theoretical framework directly shapes the research methodology in several ways:

1. Knowledge Production: Following feminist and decolonial principles, the methodology positions migrants as knowledge producers rather than research subjects, using participatory methods that recognize lived experience as expertise.

2. Material Practices: Drawing from homemaking, the methodology engages with everyday material practices—cooking, prayer, document organizing, photography—as sites of spatial knowledge rather than focusing exclusively on formal architectural elements.

3. Threshold Mapping: Informed by transboundary self-determination, the research methods examine how people navigate between different spaces and states, mapping thresholds not just as physical transitions but as emotional and social boundaries.

4. Temporal Sensitivity: Recognizing that displacement experiences evolve over time, the methodology documents how spaces transform across days, seasons, and years rather than capturing static moments

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, the methodology strives to generate knowledge that is not only academically rigorous but ethically grounded and practically relevant to the communities it seeks to serve.

How does the act of waiting create opportunities for belonging? In what ways can waiting be recontextualized as a dynamic strategy for placemaking, allowing displaced individuals to forge social connections and a sense of belonging while addressing the emergent, adaptive needs of their communities?

The traditional lepay technique—a mixture of cow dung, clay, and water historically used in Trinidad and Tobago was considered to be ‘backward’ by the British and phased out of building methods.

Mohamed Hafez’s work “Unclaimed Baggage” explores his relationship with Syria, a country he left as a student and was only able to return in 2025 after the fall of the Syrian Regime.

The constellation diagram depicts the intricate relationship between experiences, concepts, and historical contexts related to diasporas and displacement. The diagram also introduces unique concepts like “the waiting room” - physical and digital - as transitional spaces.

British colonizers photographed Indian women and used their likenesses on postcards without their consent. This practice commodified their imag and contributed to the exoticization of Indian women, framing them as objects of fascination.

The term diaspora transcends simple geographic displacement—it embodies a complex web of cultural preservation, identity formation, and memory-making through time, space, and objects. As communities move away from their homelands, they create intricate networks of belonging that manifest through architecture, objects, and shared cultural practices. This interaction between physical space, material culture, and memory forms the foundation of diasporic identity preservation.

Architecture in diasporic communities serves as more than shelter— it becomes a vessel for memory and identity. This practice is evident in projects like Javier Bosques’s Extension Familiar, where architectural spaces actively preserve oral histories and objects of socio-historical significance.1 The project demonstrates how built environments can protect both tangible artifacts and intangible cultural heritage, creating living archives of community memory.

This architectural preservation of memory echoes in V.S. Naipaul’s “A House for Mr. Biswas,” where the protagonist’s quest for a home

1 https://storefrontstore.org/editions/extension-familiar

represents more than the search for physical shelter.2 The Lion House in Chaguanas, Trinidad, is a testament to this duality—a physical structure that embodies the cultural memory of Indo-Caribbean migration and adaptation. Like the spaces in Extension Familiar, it is a tangible link to ancestral journeys and new beginnings. It highlights the tension between cultural expectations inherited from India being recontextualized to a setting where land, property, and intergenerational living are at odds with the working system imposed by British colonization.

Within these architectural spaces, objects become crucial anchors for diasporic identity. From the cooking tools and recipes that maintain culinary traditions to the textiles that carry patterns and techniques from ancestral lands, these items form a material vocabulary of cultural memory.

The “A Place at the Table” collaborative cookbook project exemplifies this intersection of object and memory, where recipes serve as practical guides and symbolic artifacts connecting generations.

This idea of preservation of memory is powerfully expressed in Mohamad Hafez’s suitcase dioramas. His miniature recreations of war-torn Syrian interiors demonstrate how architecture and objects can capture and transmit cultural memory. The suitcase itself becomes a poignant symbol—a vessel of displacement that contains carefully preserved memories of home.3

Community hubs—beauty shops, faith-based shelters, and cultural centers—emerge as informal architectural spaces where diasporic individuals foster belonging. These spaces, like those documented in “After Belonging” by Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco, demonstrate how communities adapt and create environments that support cultural preservation while facilitating integration into new contexts.4

2 Naipaul, V S. 2001. A House for Mr. Biswas. New York: Vintage Books

3 “A Broken House” — Re-Creating the Syria of His Memories, through Miniatures. Directed by Jimmy Goldblum. The New Yorker, 2021.

4 Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco. 2016. After Belonging: The Objects,

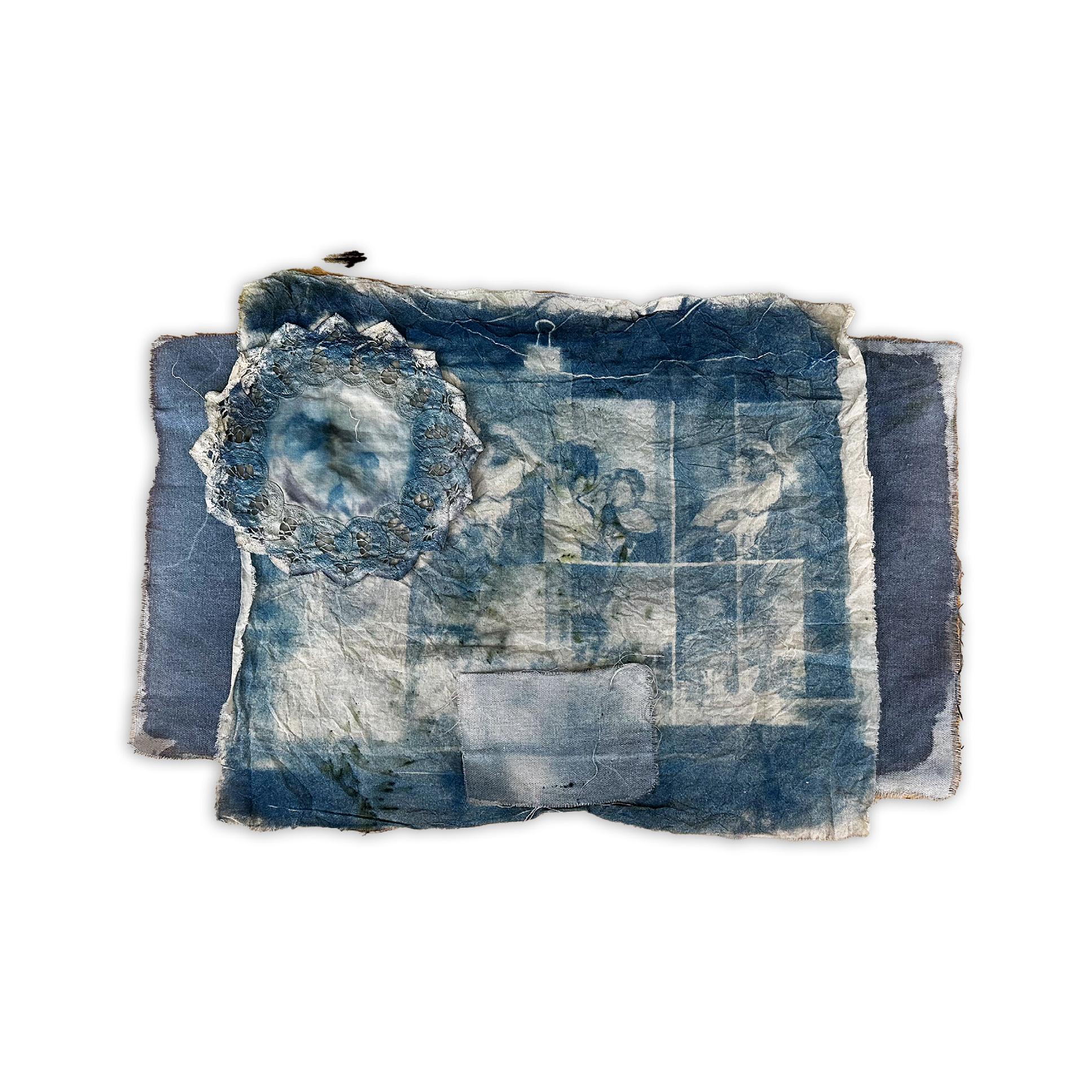

The “Traces of Displacement” exhibition at the Whitworth Art Gallery further illustrates this phenomenon, showing how displaced communities use various mediums—textiles, paintings, multimedia installations— to create spaces of memory and belonging. Mounira al Solh’s intimate portraits within the exhibition reveal how personal narratives become part of larger architectural and cultural spaces.5

Gaiutra Bahadur’s “Coolie Woman” illuminates how personal histories intersect with collective memory in diasporic communities. The stories of indentured women laborers, preserved through narrative and object, demonstrate how individual experiences contribute to broader cultural memory.6 The book becomes an architectural space—a repository for forgotten histories and preserved memories. It underscores the importance of archiving oral hostories into a form that can be passsed down,

The Welsh concept of “Marathi”—homesickness for a homeland that no longer or has never existed—underscores the importance of creating memory spaces in displacement. Projects like Hafez’s Suitcase Dioramas and Extension Familiar show how architecture can actively preserve and protect oral histories and objects of great socio-historical value, creating physical spaces where memories can be maintained and shared.7

Within these frameworks, objects take on heightened significance: - Family heirlooms become bridges between generations Spaces, and Territories of the Ways We Stay in Transit. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers.

5 Green, Leanne, Hannah Vollam, Ana Carden-Coyne, Chrisoula Lionis, and Angeliki Rousseau. 2022. Traces of Displacement: Exhibition Guide.

6 Bahadur, Gaiutra. 2013. Coolie Woman, the Odyssey of Indenture. University Of Chicago Press.

7 “A Broken House” — Re-Creating the Syria of His Memories, through Miniatures. Directed by Jimmy Goldblum. The New Yorker, 2021.

- Traditional implements preserve cultural practices

- Photographs and documents record community histories

- Artistic works interpret collective memories

Conclusion

The intersectionality of diaspora, architecture, and material culture reveals how communities maintain identity across borders and generations. Through projects like Extension Familiar, artistic works like Hafez’s dioramas, and literary expressions like “A House for Mr. Biswas,” we see how physical spaces and objects preserve cultural memory and enable cultural continuation.

This preservation occurs not just through grand architectural gestures or formal institutions, but through the everyday practices of homemaking, object preservation, and community gathering. Understanding these processes helps us appreciate the resilience of diasporic communities in maintaining their cultural heritage while adapting to new environments.

The architecture of memory, whether manifest in physical buildings, preserved objects, or created spaces, provides essential infrastructure for cultural preservation. It enables communities to maintain connections to their heritage while creating new identities in adopted homes. Through this balance of conservation and adaptation, diasporic communities continue to write their stories in space and objects, creating living archives of cultural memory that span generations and borders.

The Lion House, also known as Hanuman House, in V.S. Naipaul’s “A House for Mr Biswas,” provides a compelling case study for examining the intricate dynamics of gender and power within traditional Indian diasporic households in Trinidad and Tobago. This imposing structure represents a microcosm of postcolonial society, where women play a vital and crucial role in cultural preservation and family cohesion, a role that is often unacknowledged immense significance.

In Hanuman House, we witness how women, particularly the Tulsi women, are simultaneously powerful and powerless. They serve as the backbone of the household, orchestrating daily life and preserving traditions, yet their contributions are often overlooked or taken for granted. The novel reveals how Tulsi women are powerless outside the home because their traditional marriages bar them from doing much outside the house. However, they are not alone in their struggles. They are supported and connected inside the home because the women form Hanuman House’s core social unit, a bond that strengthens them in the face of adversity.

This paradoxical position of women in Hanuman House reflects broader themes of identity, belonging, and agency. Despite their limited autonomy, the silent strength of these women in maintaining the household provides a nuanced perspective on how displaced individuals, particularly women, navigate and reshape transitional spaces. Their experiences in Hanuman House offer insights into the complex process of home-making in displacement, highlighting the spiritual and emotional dimensions of creating a sense of belonging in interstitial spaces.

By examining the Lion House, we uncover how transitional spaces can become sites of oppression and potential empowerment for women.

“Among the tumbledown timber-and-corrugated-iron buildings in the High Street in Arwacas, Hanuman House stood there like an alien white fortress. The concrete walls looks as thick as they were, and when the narrow doors of the Tulsi Store on the ground floor were closed the House became bulky, impregnable and blank.” [Chapter 3]

The Lion House, known as Hanuman House in V.S. Naipaul’s “A House for Mr Biswas,” is a powerful symbol of collective memory, cultural preservation, and the complex dynamics of belonging in a postcolonial context.

This imposing structure, based on the real-life Anand Bhavan in Trinidad, represents a microcosm of the transitional and interstitial spaces central to the experiences of displaced individuals. As Mr. Biswas navigates his relationship with this communal dwelling, Naipaul explores themes of identity reclamation and agency that resonate deeply with the struggles of those caught between traditional values and modernizing forces.

The Lion House embodies the tension between collective identity and individual autonomy, serving as a refuge and a constraint for its inhabitants. It becomes a site of cultural preservation, where rituals and traditions are maintained, yet simultaneously representing the challenges faced by those seeking to forge their paths.

Through Mr. Biswas’s experiences within and attempts to escape from the Lion House, Naipaul illustrates the complex process of home-making in displacement, highlighting the spiritual and emotional dimensions of creating a sense of belonging in transitional spaces.

Here, the Tulsi women, daughters, and daughtersin-law prepare dinner together for their large family. Women take turns caring for babies and children and divide the tasks of setting the table and other chores.

The men are out or resting, waiting to be called for dinner.

2: eating

Only at meals do the roles of wife and mother step out of the shadows to serve husbands and feed children. Notably, in this scene, the emphasis is on the men and children, not on the quality of the food or the significant time it would’ve taken to make the dishes.

This underappreciation of the effort is a point of concern.

Once again, the women of Tulsi restored the kitchen and dining room to their normal and calm state. The men, however, chose to rest and refrain from helping with the housework, thereby perpetuating patriarchal norms.

As the main bedroom was shared among married couples, the women would sleep in the dining room for decency and privacy, allowing them to be safe together and build a sisterhood.

The Capildeo Family

The inspiration for ‘A House for Mr. Biswas’

What about Shama?

Mr. Biswas’ wife was the tie that kept the family and household from ruin, but she is seen as a passive, useless character.

CHAPTER SIX

critical theory illuminates how power structures and gender dynamics function within systems of oppression, particularly in contexts of displacement and homemaking. Through the work of scholars like Simone de Beauvoir, bell hooks, Judith Butler, Walter Mignolo, and Anibal Quijano, we can trace how colonial legacies shape both gender dynamics and cultural erasure. This intersection of feminist theory and decoloniality reveals how women’s homemaking practices serve as powerful acts of resistance and cultural preservation within displacement.

The integration of feminist critical theory with decolonial perspectives exposes complex power dynamics within displacement contexts. Patriarchal systems perpetuate gender inequality through institutional and social mechanisms, while colonial legacies continue to impact displaced communities.

Gaiutra Bahadur’s “Coolie Woman” offers compelling documentation of this resilience through its examination of indentured women’s experiences. Bahadur’s investigation of her great-grandmother’s journey from Bihar to

Guyana raises profound questions about agency, coercion, and survival.8 Her great-grandmother’s story—traveling alone and pregnant, promised her husband would follow—mirrors the experiences of countless others. The uncertainty surrounding such departures—whether fleeing abuse, falling victim to trafficking, or seeking opportunity—reflects the complex circumstances of women’s displacement. Through these narratives, Bahadur recovers the histories of approximately a quarter-million “coolie” women, revealing their strategies for maintaining cultural practices and building support networks under oppressive conditions.

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” explores similar themes through magical realism. Based on Margaret Garner’s escape from slavery, the novel examines women’s preservation of identity and community under extreme oppression.9 Morrison’s supernatural elements and temporal shifts capture trauma’s ongoing impact while highlighting how maternal practices and community networks enable cultural preservation. The novel’s exploration of intergenerational trauma parallels the experiences documented in “Coolie Woman,” demonstrating displacement’s multi-generational effects.

Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” contributes a crucial perspective on psychological displacement through its exploration of alienation under patriarchal authority. The poem’s personal narrative illuminates broader patterns of gender-based oppression and resistance, demonstrating how creative expression enables the reclamation of agency.10 This psychological dimension complements accounts of physical displacement, revealing the multiple levels at which women experience and resist oppression.

Maria S. Giudici’s “Counterplanning from the Kitchen” provides a theoretical framework for understanding domestic spaces as sites of resistance. While traditional views frame these spaces as locations of invisible, undervalued reproductive labor, feminist analysis reveals homemaking as a political

8 Bahadur, Gaiutra. 2013. Coolie Woman, the Odyssey of Indenture. University Of Chicago Press.

9 Morrison, Toni. (1987) 1987. Beloved. London: Vintage.

10 Plath, Sylvia. “ Daddy .” The Poetry Foundation., accessed 09/15/, 2024, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48999/daddy-56d22aafa45b2.

act through which women assert agency and preserve cultural practices.11

2Daily activities like cooking, storytelling, and crafting become powerful means of maintaining cultural identity and building community networks that support survival and resistance.

The analysis of waiting rooms as gendered spaces offers another vital perspective on women’s displacement experiences. Though often designed without consideration for women’s needs, these institutional spaces become sites where women perform essential emotional labor and construct informal support networks. Through these practices, women transform sterile institutional environments into vibrant centers of community formation and cultural preservation.

Contemporary efforts to decolonize design practices build on this understanding of space as simultaneously oppressive and resistant. By integrating indigenous design principles and prioritizing community engagement, these approaches create more inclusive and culturally responsive spaces. This work acknowledges spatial design’s crucial role in either supporting or hindering cultural preservation and community building.

While the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defines displaced women as those forced to flee their homes due to conflict, persecution, or violence, this definition only begins to capture their complex experiences. Despite facing gender discrimination and limited resources, women actively resist erasure through homemaking practices that support cultural preservation and community building.

These insights carry significant implications for both theory and practice. Understanding how women maintain cultural identity and build community through homemaking can inform more effective and culturally sensitive approaches to supporting displaced populations. This requires

11 Giudici, Maia S. (2018) Counter-planning from the kitchen: for a feminist critique of type, The Journal of Architecture, 23:7-8, 1203-1229, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2018.1513417

recognizing women’s agency while acknowledging structural constraints, working toward solutions that support both individual empowerment and collective resilience.

Conclusion

The ongoing relevance of these issues, from historical experiences of indenture to contemporary displacement, underscores the importance of documenting and supporting women’s resistance strategies and cultural preservation practices. This understanding challenges us to create more equitable approaches to displacement—approaches that recognize women’s agency while addressing the structural inequities that perpetuate displacement and gender-based oppression.

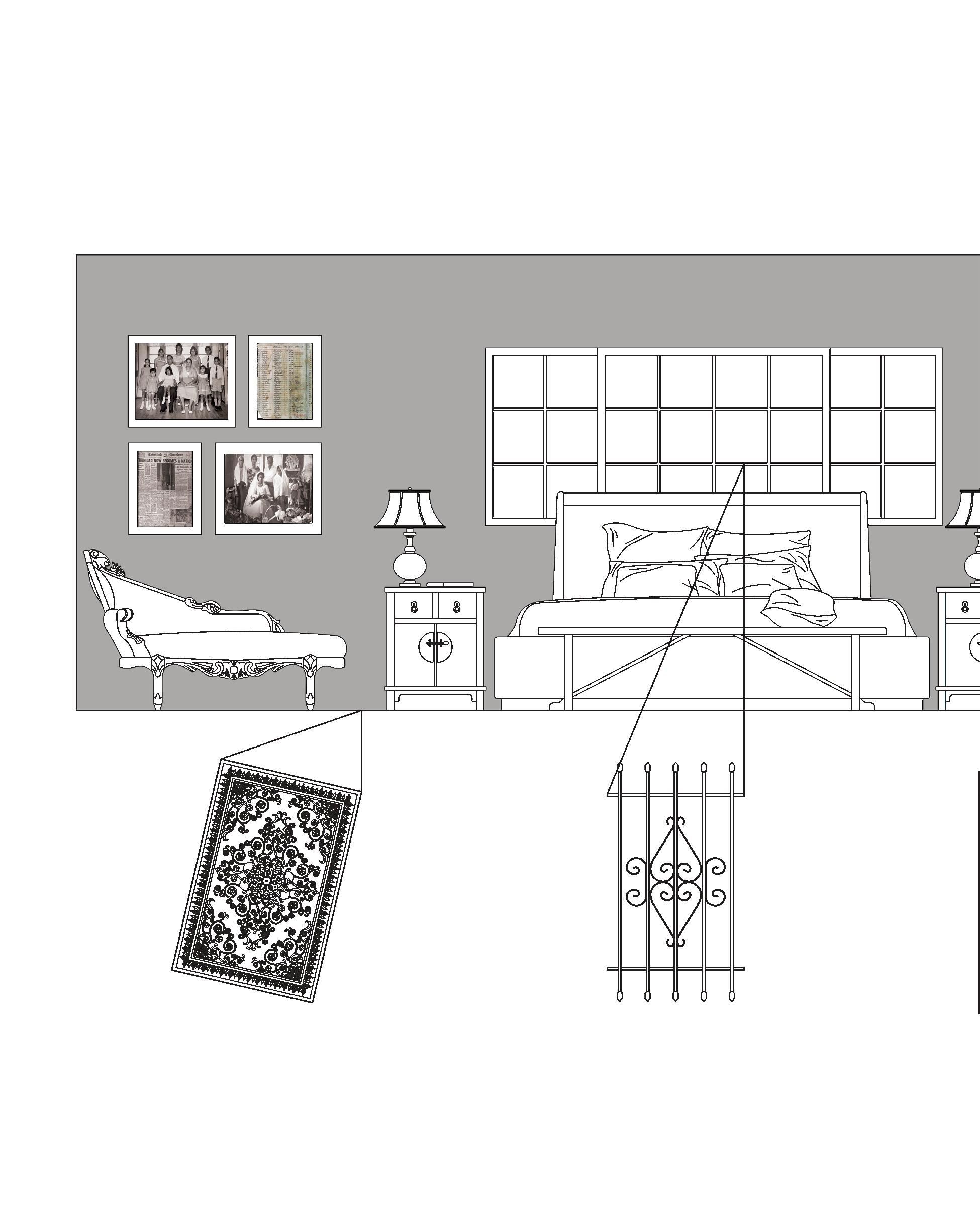

In this case study, we delve into two intimate spaces that embody themes of safety, tradition, and community: my grandmother’s bedroom and my childhood babysitter, Aunty Nicey’s kitchen. These spaces reveal how personal environments can reflect deeper cultural practices and values, and our exploration of them is instrumental in understanding the complex layers of cultural identity.

My grandmother’s bedroom is a testament to the preservation of memory and tradition. The wrought iron on the windows symbolizes a commitment to safety, creating a secure haven. Her prayer corner is a sacred space where tradition is actively practiced, surrounded by old photographs that serve as visual anchors to the past.

Aunty Nicey’s kitchen offers a unique perspective on safety and community. In unexpected places, money and valuables are hidden away, challenging typical notions of security. Aunty Nicey embodies this concept of personal safety, famously keeping her money tucked in her bra top—a practice known as body coding, where one’s body becomes the safest place. The large pots in her kitchen are not just for cooking; they symbolize community gatherings and the rebuilding of heritage, fostering a sense of belonging and shared history. This introduction sets the stage for a detailed analysis of how these spaces function as more than just physical locations—they are reflections of cultural identity and resilience.

After many years of sacrifice and hard work, my grandparents built this home when they moved from Surinam to Trinidad. The house was completed in 1978, and my grandma has lived there since. Something interesting to note about the floor plan is while other rooms in the house have changed, the master bedroom has remained the same, a testament to our family’s enduring traditions. It is also the only room behind two locked doors, reinforcing the physical appeal of feeling safe at home. It is where my grandma sleeps and calls her sanctuary, where she can feel safe in the years after my grandfather’s passing in 2016.

Security & Ritual Making; Affirmation of Traditional Values wrought iron Security & Protection; Physical Embodiment of Protection and Strength while still adding aesthetically to the home

hidden ‘Corners’ Security & Agency; Able to put valuables away in a place only she knows

Cookie tin Memories & Tradition- it was also her mom’s sewing kit and where she hid her valuables

Cookie tin

A place where Aunty Nicey hid her dowry in case she needed it to sell or melt for its gold contents.

hidden ‘Corners’ Security & Agency; Able to put valuables away in a place only she knows

money in bras Security & Agency; Body Coding; In this case, her body is the safest thing and what she can trust

ColleCtive kitChens Community empowerment; opportunity for women to meet; a safe space for many.

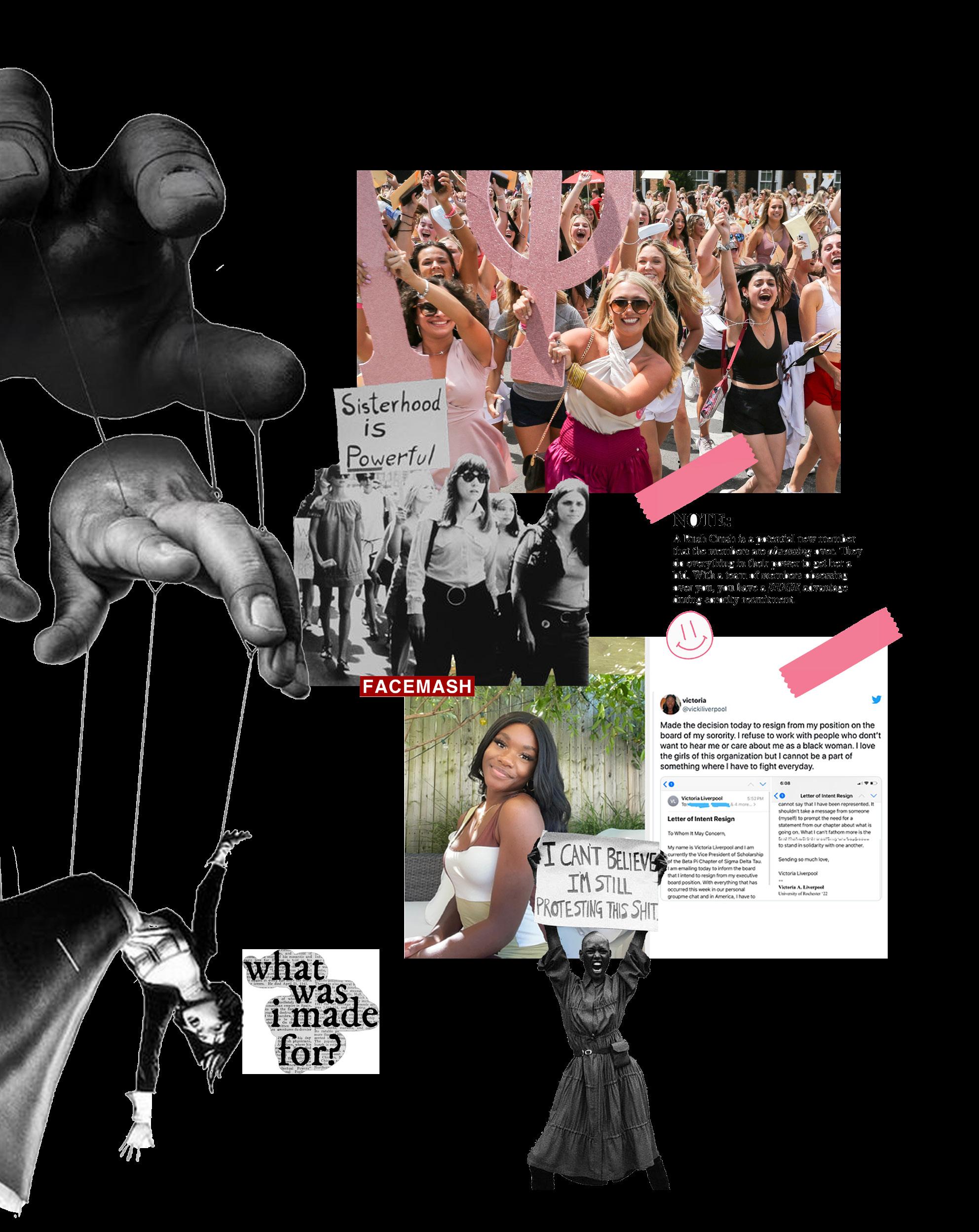

Case Study: Sororities, a Critique on the meaning of ‘Sisterhood.’

The concept of sisterhood within sororities is multifaceted and steeped in traditional and modern complexities. After watching Bama Rush and exploring the viral phenomenon of #rushtok, it becomes clear that these organizations, founded initially to empower and educate women, have evolved under the influence of societal expectations and patriarchal norms—what I refer to as the “male gaze.”Sororities promise a sense of belonging and legacy, offering young women a community where they can forge lifelong friendships.

However, beneath this veneer lies a more complicated reality. The desire to fit into these social constructs often leads to conformity, where individuality is sacrificed for acceptance. This duality is reflected in both the camaraderie and the challenges members face. My conversations with my mother, who attended an all-girls high school, further highlighted this tension. While there is undeniable strength in sisterhood, the social hierarchies within these groups can perpetuate exclusion and competition. The pressures to conform to certain ideals—often dictated by external societal standards— can lead to harmful behaviors such as eating disorders and vulnerability to issues like the date rape drug.

Moreover, the role of social media amplifies these pressures, creating an environment where appearance and perception are constantly scrutinized. Yet, women find solace in each other in this challenging landscape, forming bonds that provide safety and support against external threats. This paradoxical nature of sororities—where empowerment coexists with vulnerability—demands a critical examination of how these institutions can evolve to truly serve the interests of their members.of how these spaces function as more than just physical locations—they are reflections of cultural identity and resilience.

Founded on the concept of empowerment, sororities are meant to provide a safe space for growth and support. Fraternities reinforce this, highlighting the influence of patriarchy on perpetuating a sisterhood narrative convenient to their agenda.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Decolonizing design represents a crucial movement to dismantle colonial legacies embedded in architecture, material culture, and design practices. This approach extends beyond aesthetic considerations to challenge fundamental knowledge, power, and cultural value assumptions. The process of decolonization itself—achieving cultural, psychological, and economic freedom for previously colonized peoples—requires a fundamental reimagining of how we conceive, create, and inhabit spaces. By examining spaces from waiting rooms to cultural centers, we can understand how design perpetuates or resists colonial structures of power.

Aníbal Quijano’s seminal work, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America,” provides a crucial framework for understanding how colonial structures persist in modern systems. Quijano argues that colonialism didn’t end with formal decolonization but transformed into a pervasive power structure—coloniality—that continues to shape global hierarchies.12 This system organizes society along racial, economic, and

12 Quijano, Anibal, and Michael Ennis. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.”Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000): 533-580. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/23906.

epistemological lines, maintaining European knowledge systems and cultural values as supposedly superior. When we examine contemporary architectural spaces, we often find these colonial hierarchies reproduced in everything from spatial organization to material selection, manifesting in the privileging of certain aesthetic traditions, the dismissal of Indigenous building practices, and the perpetuation of power dynamics through spatial arrangements that subtly reinforce colonial authority.

Quijano’s critique of Eurocentrism as aframework reveals how European knowledge became positioned as universal while marginalizing other ways of knowing. Walter Mignolo’s “The Darker Side of the Renaissance” further explores this dynamic, demonstrating how European Renaissance ideals shaped modern knowledge systems and design practices, often dismissing vernacular approaches as backward or primitive.13 2The impact of this Eurocentric bias appears clearly in architectural education and training, where indigenous and traditional building techniques, spatial organizations, and the use of local materials often face dismissal as “primitive” despite their ecological wisdom and cultural significance.

The critique of bureaucratic spaces, such as waiting rooms and asylum intake centers, reveals how institutional design often perpetuates colonial power structures. These spaces frequently subject displaced individuals to dehumanizing processes rooted in hierarchical power dynamics. The layout of these spaces—from the arrangement of seating to the positioning of administrative desks—often reinforces power differentials and creates environments of surveillance and control. However, these same spaces also become sites of resistance where individuals and communities maintain dignity and cultural practices despite institutional constraints. Through subtle interventions and adaptations, displaced people transform hostile institutional environments into community and cultural preservation places.

Contemporary decolonial design practices emphasize the integration

13 Mignolo, Walter D. 1998. The Darker Side of the Renaissance. Ann Arbor: Univ. Of Michigan Press.

of vernacular materials and traditional techniques. Practices like lipay (using cow manure in floor finishing) represent indigenous knowledge systems that challenge Eurocentric design norms. The revival of vernacular techniques goes beyond mere aesthetic choices to embrace different ways of knowing and building. These practices often embody sustainable principles and deep cultural knowledge, offering alternatives to industrialized construction methods. Their incorporation into contemporary design represents a form of resistance to the homogenizing forces of global architecture.

Projects like the “A Place at the Table” collaborative cookbook and traditional textile work serve as archives of cultural memory, documenting practices that colonial systems attempted to erase. These initiatives demonstrate how design can support cultural continuity while challenging colonial hierarchies. The documentation and preservation of traditional practices through design projects maintain cultural knowledge across generations, challenge the supremacy of Western design traditions, create physical spaces that support cultural practices, and build community through shared knowledge and skills.

The relationship between coloniality and identity manifests clearly in how displaced communities navigate designed spaces. Design practices that support cultural preservation—from cooking to crafting—become acts of resistance against systemic erasure. These practices help maintain cultural identity amid displacement while challenging colonial narratives that exoticize or marginalize non-European identities. The role of design extends beyond physical space to encompass cultural gathering spaces, support for traditional practices, preservation of cultural memory, and resistance to assimilation pressures.

The 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale’s Brazilian Pavilion exemplifies contemporary approaches to decolonial design. This project demonstrates how design can actively support decolonization efforts by challenging historical narratives and architectural practices that have marginalized Indigenous and Quilombola communities. The integration of Indigenous

knowledge systems and cultural heritage into contemporary architecture provides: illustrating the importance of recognizing Indigenous spatial knowledge, integrating traditional building techniques, involving communities in design processes, ad challenging dominant architectural narratives.143

Contemporary decolonial design interventions take many forms, from spatial organization supporting multiple uses and communal activities to material choices incorporating local and traditional techniques. Community engagement becomes crucial, involving local populations in design processes, recognizing indigenous knowledge systems, and building collective ownership of spaces. These interventions create environments that support cultural preservation through spaces for traditional practices, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and community gatherings.

14 https://www.archdaily.com/1001311/earth-as-ancestral-and-future-technology-an-interview-with-gabriela-de-matos-and-paulo-tavares-curators-ofthe-brazil-pavilion-and-winners-of-the-golden-lion-at-the-2023-venice-biennale

Case Study: Sororities, a Critique on the meaning of ‘Sisterhood.’

The concept of sisterhood within sororities is multifaceted and steeped in traditional and modern complexities. After watching Bama Rush and exploring the viral phenomenon of #rushtok, it becomes clear that these organizations, founded initially to empower and educate women, have evolved under the influence of societal expectations and patriarchal norms—what I refer to as the “male gaze.”Sororities promise a sense of belonging and legacy, offering young women a community where they can forge lifelong friendships.

However, beneath this veneer lies a more complicated reality. The desire to fit into these social constructs often leads to conformity, where individuality is sacrificed for acceptance. This duality is reflected in both the camaraderie and the challenges members face. My conversations with my mother, who attended an all-girls high school, further highlighted this tension. While there is undeniable strength in sisterhood, the social hierarchies within these groups can perpetuate exclusion and competition. The pressures to conform to certain ideals—often dictated by external societal standards— can lead to harmful behaviors such as eating disorders and vulnerability to issues like the date rape drug.

Moreover, the role of social media amplifies these pressures, creating an environment where appearance and perception are constantly scrutinized. Yet, women find solace in each other in this challenging landscape, forming bonds that provide safety and support against external threats. This paradoxical nature of sororities—where empowerment coexists with vulnerability—demands a critical examination of how these institutions can evolve to truly serve the interests of their members.of how these spaces function as more than just physical locations—they are reflections of cultural identity and resilience.

Displacement fundamentally and often traumatically reshapes human experiences, encompassing both the physical act of being uprooted from one’s home and the profound emotional toll this displacement inflicts on individuals and communities. In this context, waiting rooms emerge as crucial sites of study—spaces that function both literally and metaphorically as zones of transition and uncertainty. Often designed to process and contain displaced populations, these spaces can also become unexpected sites of resistance and cultural preservation through homemaking practices.

The concept of the waiting room extends beyond its physical manifestation in places like Brigid’s Respite Center or asylum intake facilities. As explored in “Making Home(s) in Displacement: Critical Reflections on a Spatial Practice” (2022), these spaces represent complex environments where displaced individuals grapple with prolonged uncertainty about their legal status and future prospects. The book brings together scholars from architecture, urban studies, and migration studies to examine how displaced people worldwide create a sense of ‘home’ and belonging in transient spaces, particularly within contemporary geopolitical conflicts like the global refugee crisis and forced migration.15

15 Beeckmans, Luce, Alessandra Gola, Ashika Singh, and Hilde Heynen, eds. Making Home(s) in Displacement: Critical Reflections on a Spatial Practice. Leuven University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv25wxbvf.

Chapter 8, titled “Years in the Waiting Room,” provides particularly valuable insights as it explores waiting as both a spatial and temporal experience. The waiting room becomes a physical embodiment of liminality—a space situated between departure and arrival, past and future, belonging and exclusion.152 This analysis is further enriched by The Funambulist’s investigation of “waiting bodies in dictatorial and bordering regimes,” which reveals how the experience of waiting is often weaponized by those in power against people in transition, especially in migration and border control contexts.

The physical design of waiting rooms frequently exacerbates feelings of anxiety and powerlessness. Overcrowding, lack of privacy, and dehumanizing bureaucratic processes create environments that can intensify the trauma of displacement. These spaces, primarily designed for administrative efficiency rather than human dignity, often fail to address the complex emotional and cultural needs of displaced individuals.163 However, within these challenging environments, there are opportunities to reimagine these spaces as sites of healing and cultural affirmation by incorporating culturally sensitive design elements, vernacular materials, and storytelling installations.

Homemaking practices become essential tools for reclaiming agency within these liminal spaces. Through everyday acts such as cooking traditional meals or mending clothes, displaced individuals maintain vital connections to their heritage while adapting to new environments. These practices transform sterile institutional spaces into hubs for cultural preservation and community building. The diasporic cookbook project exemplifies this dynamic, documenting recipes not merely as cooking instructions but as acts of cultural preservation that link displaced individuals to their heritage and community.

The significance of these homemaking practices extends beyond mere survival or comfort. They represent active resistance against the erasure of cultural identity, often accompanying displacement. By creating familiar 15 Ibid.

16 Beeckmans, Luce, Alessandra Gola, Ashika Singh, and Hilde Heynen, eds. Making Home(s) in Displacement: Critical Reflections on a Spatial Practice. Leuven University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv25wxbvf.

environments within unfamiliar spaces, displaced individuals assert their agency and uphold cultural traditions despite institutional constraints. These acts of homemaking in waiting rooms and temporary shelters demonstrate how displaced individuals navigate the complex terrain between preservation and adaptation, maintaining cultural identity while forging new forms of belonging.

Contemporary scholarship on displacement increasingly recognizes the importance of these spatial practices in understanding how displaced populations create meaning and maintain dignity in transitional environments. The way individuals transform waiting rooms through homemaking practices reveals the resilience of displaced communities and highlights the potential for redesigning institutional spaces to better support cultural preservation and community building.

This understanding challenges designers and institutions to reconceptualize waiting spaces as not merely sites of passive containment but as active environments that support cultural preservation and community formation. By incorporating elements that acknowledge and facilitate homemaking practices—from communal kitchens to areas for storytelling and cultural celebration—waiting rooms can better address the complex needs of displaced populations while fostering dignity and cultural continuity.

The intersection of displacement, waiting, and homemaking practices highlights how displaced individuals navigate and transform spaces of uncertainty into sites of belonging. Through everyday acts of cultural preservation and community building, they challenge the traditional notion of waiting rooms as purely transitional spaces, creating environments that uphold individual dignity and collective resilience instead. This understanding offers crucial insights for designing more humane and culturally responsive institutional spaces.

This case study showcases women’s diverse resistance against patriarchal structures. The acts of defiance range from subtle everyday actions to explicit protests, highlighting the multifaceted nature of women’s resistance and the complexity and depth of the issue.

The first category explores the potency of collective rituals in everyday life, with a particular focus on the Russian banya. This seemingly mundane act, where women of all ages and backgrounds come together, transforms into a powerful symbol of solidarity. It serves as a potent reminder that resistance can be seamlessly woven into the fabric of daily life, offering opportunities for empowerment and connection that inspire with their strength.

The second category brings to light the significance of celebratory moments, such as henna parties before weddings. These women-only gatherings, where friends and family adorn the bride with henna, are not just about the celebration. They are powerful spaces for women to bond, support each other, and affirm their womanhood. Even in the face of challenges, such as those experienced by Syrian refugees, these events offer moments of joy and a powerful affirmation of womanhood that uplifts with their resilience.

The third category underscores the impact of explicit protests, as seen in the Roe v. Wade demonstrations. These protests are potent expressions of collective resistance, drawing attention to critical issues and demanding change. They highlight the ongoing struggle over women’s rights in American politics, particularly concerning bodily autonomy. Through these images and narratives, this visual archive illustrates how women navigate and challenge patriarchal structures in varied and profound ways. From the every day to the extraordinary, these acts of resistance underscore the resilience and solidarity inherent in women’s communities around the world.

Finding community and building solidarity in everyday activities that allow for conversation or vulnerable moments to be shared.

Celebratory moments are often before a milestone or life transition. These moments bring women together for a culturally accepted gathering or event.

Protests are the most obvious forms of resistance that stem from working together against a policy or event.

The Mundane: Solidarity in Everyday Ritual

Celebratory Moments

Seeking asylum in the United States is a complex process, characterized by bureaucratic, psychological, and social challenges. For displaced individuals arriving in cities like New York, the journey involves navigating unfamiliar systems, enduring prolonged waiting periods, and experiencing significant emotional strain.

Asylum seekers typically arrive at U.S. ports of entry, such as JFK Airport in New York City, where they are processed by Customs and Border Protection (CBP). This initial interaction involves documentation, health screenings, and the issuance of a Notice to Appear (NTA) for an immigration court hearing. Many migrants are then transported to New York City by bus or other means and directed to intake centers or temporary shelters. These places serve as transitional environments where migrants begin their journey through the U.S. asylum system.

Upon arrival in New York City, migrants are directed to facilities like Brigid’s Respite Center or the Roosevelt Hotel Asylum Intake Center. Brigid’s Respite Center, a repurposed Catholic school, functions as a temporary holding site where migrants receive basic necessities such as cots and food; however, they lack access to showers or laundry facilities. Overcrowding and minimal resources amplify feelings of liminality and discomfort. In contrast, the Roosevelt Hotel Asylum Intake Center serves as a centralized hub offering legal aid, health services, and temporary housing. Dubbed NYC’s “modern Ellis Island,” it symbolizes both hope and systemic failure, as its overcrowded conditions sharply contrast with its historical grandeur.

The asylum process is marked by extended waiting periods that can last months or years. During this time, migrants must file Form I-589 (Application for Asylum) within one year of their arrival and await immigration court hearings to determine their eligibility. Many face restrictions on employment authorization during this period, which compounds their financial instability. The waiting period often severely impacts mental health, with studies revealing high levels of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among asylum seekers due to prolonged uncertainty about their legal status, isolation from family and community.

The bureaucratic process for asylum seekers in the United States is can be considered messy due to systemic inefficiencies, resource limitations, and the overwhelming scale of need.

the power of lady liberty

Spaces like Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty historically symbolized hope and opportunity for immigrants coming to the United States.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, With conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

The Roosevelt Hotel, a Beaux-Arts landmark built in 1924, was repurposed in May 2023 as New York City’s first centralized asylum intake center. Once a symbol of luxury and sophistication, it now serves as a processing hub for migrants. It is often referred to as the modern day Ellis Island.

The city has recently introduced limits on how long migrants can stay at shelter sites (30 or 60 days), leading to faster turnover but also increased uncertainty for those affected.

Long lines regardless of season.

6. Waiting period: Like Brigid’s

Center, migrants experience a waiting period while their cases are processed or while they await placement in longer-term accommodations.

Migrants report sleeping on floors or in overcrowded rooms due to limited space.

1. arrival at the intake Center: Newly arrived asylum seekers are directed to the Roosevelt Hotel, which serves as a centralized intake center for New York City.

2. registration and identifiCation: Migrants are registered upon arrival. Information such as their name, family size, and immediate needs is collected. Wristbands are issued to track individuals within the building and ensure proper management.

3. health sCreenings: Migrants are led to a designated health clinic within the hotel for medical evaluations. This includes screenings for diseases, vaccinations, and mental health assessments. Over 70,000 vaccines have reportedly been administered since the center opened.

Despite its historical grandeur, the hotel has been transformed into a functional space prioritizing efficiency over comfort.

4. case management: Each migrant is assigned a case manager who helps them navigate next steps in their journey. This includes assistance with legal paperwork for asylum applications and connections to social services. If migrants have family or friends in other states, case managers coordinate transport.

5. temporary housing assignment: Migrants requiring shelter are assigned temporary housing either within the Roosevelt Hotel (up to 850 rooms) or in one of New York City’s many emergency shelters or humanitarian relief centers. Families and children are prioritized for available rooms within the hotel.

Located in the former St. Brigid’s Catholic School, the respite center was established in May 2023 to address the surge in migrants arriving in New York City. The building, previously closed since 2019, was repurposed as a temporary site for migrants awaiting placement in shelters or other accommodations

Brigid’s Respite Center operates as a transitional space, described as a “waiting room” for migrants. It provides cots for sleeping and basic necessities but lacks essential amenities such as showers or laundry facilities. Migrants are processed here and directed to other shelters or services, though overcrowding and limited resources results in confusion and frustration.

As a result of these diffi cult waiting times for being re-processed, many single migrants end up in cramped waiting areas or outside of respite centers.

Unlike the Roosevelt Hotel, Brigid’s Respite is far more grassroots, with volunteers assisting with to basic living necessities.

The landscape of displacement in New York City reveals complex intersections of power, community resilience, and spatial politics. This community and context research examines how bureaucratic spaces –from airports to social security offices – shape the experiences of displaced communities while simultaneously exploring how community-anchored spaces like mosques, churches, and beauty salons serve as sites of resistance and belonging.

The historical context of New York City as a gateway for immigrants has evolved from Ellis Island’s symbolic promise of opportunity to today’s network of processing centers and temporary shelters. This evolution reflects broader shifts in how the state manages and controls migration, mainly through what feminist scholar Sara Ahmed describes as “the politics of waiting.” The Roosevelt Hotel, now dubbed the “new Ellis Island,” exemplifies this transformation – from a symbol of luxury to a processing center where asylum seekers navigate complex bureaucratic systems.

When examining these spaces through a decolonial framework, it is apparent how institutional architecture reinforces power dynamics inherited from colonial systems. The design of social security offices, DMVs, and intake centers prioritizes surveillance and control over dignity and human connection. As mentioned in the case studies, design is not for the end user but rather for the sake of efficiency and control.

However, within this landscape of control, communities have created alternative spaces of care and resistance. Mosques and churches, particularly in neighborhoods in Brooklyn, serve as crucial nodes of support for displaced communities. These religious institutions often function beyond their spiritual role, becoming impromptu legal clinics, food distribution centers, funeral homes and gathering spaces where displaced individuals can maintain cultural practices and build new networks of support.

The spatial politics at play become evident when mapping these contrasting environments. While government-run facilities maintain rigid hierarchies through physical barriers, security checkpoints, and standardized processing procedures, community spaces emphasize collaborative relationships and flexible use of space. A mosque might transform from a prayer space to a makeshift shelter, demonstrating how community-driven design responds to immediate needs rather than bureaucratic protocols.

Economic structures significantly impact these spatial dynamics. While billions are spent on emergency shelters and processing centers,

community organizations operate on limited budgets, often relying on grassroot volunteer networks and donations.

Through participatory research methods that center on the experiences of displaced communities, this study starts by documenting oppressive nature of bureaucratic spaces and the transformative potential of communityanchored alternatives. By mapping and diagramming the process to belonging within these bureaucratic and constricting infrastructures, the aim is to better understand how design can reinforce or resist colonial power structures in the context of contemporary migration.

2. transPortation to nyC and initial PlaCement: Migrants are bused to NYC from border states like Texas as part of state relocation programs or through personal travel arrangements.

3. first stoP: Many migrants are directed to intake centers or temporary respite sites.

wristbands become a code by which migrants are referred.

4. registration and health sCreenings: Migrants undergo registration, where their personal details are recorded. They receive wristbands for tracking within the facility. Health screenings check for diseases and administer vaccinations. Mental health screenings for individuals showing signs of PTSD.

5. Case management and legal assistanCe: Migrants meet with caseworkers who help them understand their legal status and next steps in the asylum application process.

7. filing for asylum: Within one year of arrival in the U.S., migrants must submit Form I-589 (Asylum Application) to USCIS or during their first immigration court hearing. Filing triggers eligibility for an Employment Authorization Document (EAD), but work permits can take months to process due to backlogs.

8. waiting Period: After filing for asylum, migrants enter a prolonged waiting period that can last several months or years due to backlogged immigration courts, delays in processing work permits and asylum applications.

9. immigration Court hearings: Migrants attend hearings at immigration courts where they present their asylum cases before a judge. They must prove a credible fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Legal representation is critical but not guaranteed; many rely on nonprofit organizations.

10. deCision on asylum aPPliCation: ApprovAl: The migrant is granted asylum status, allowing them to apply for permanent residency after one year.

DeniAl: The migrant may appeal the decision or face deportation proceedings.

My maternal great-grandmother

Among the photographs collected during this research is one that carries particular weight: the only surviving image of my great-grandmother, captured on her wedding day. In 1924, she died from an at-home abortion performed by a midwife.

Already running a shop and raising seven children, an eighth pregnancy became an impossible burden. This single photograph preserves not just her image but a complex legacy of choice made under constraint. The silence that followed her death—the unspoken grief, the family’s dispersal, the erasure of her full humanity behind veils of shame—created its own form of displacement across generations.

Displacement often involves profound grief—not only for the physical loss of home but for the intangible losses of identity, community, and a sense of belonging. This grief is compounded by the circumstances under which many leave their homes: war, persecution, or economic instability.

Displaced individuals often mourn:

• Who they once were.

• The lives they left behind: Familiar routines, cultural practices, and relationships are disrupted.

• Loved ones: Many leave family members behind or lose them during migration.

This mourning process is unique because it occurs at a distance, often without closure. Unlike traditional mourning rituals that allow individuals to grieve collectively, those who are displaced must process their grief in isolation and in unfamiliar environments.

Objects play a complex role during displacement, balancing practical necessity with emotional significance. While displaced individuals prioritize essential items like documents and clothing, these objects often take on an important symbolic value relating to home and identity. For instance, a photograph can serve as a connection to loved ones left behind, while a cooking utensil allows for the recreation of familiar tastes and memories.

In the context of displacement, what is often lost is not just physical home but the ability to author one’s own narrative. Mainstream representations of migrants frequently oscillate between two problematic extremes: either as helpless victims requiring salvation or as threatening masses to be controlled. Both perspectives strip migrants of their complexity, agency, and individual stories. Photography—when placed in the hands of those experiencing displacement—disrupts this dynamic, creating what bell hooks calls “a site of resistance” where people can reclaim control over their representation and, by extension, their identity.

“Through the Lens” emerged as a core methodological component of this research, guided by the understanding that traditional architectural documentation often fails to capture the embodied experience of space. Disposable cameras were distributed to migrants living in Sunset Park, accompanied by simple prompts: What spaces feel most like home? How do you adapt spaces to reflect your culture? Where do you feel a sense of belonging? The resulting photographs constitute a powerful visual archive that challenges conventional architectural analysis in several ways. First, disposable cameras democratize the documentation process. Unlike professional equipment that creates distance between researcher and subject, these simple tools require no technical expertise and minimize

the power imbalance inherent in traditional photography. The grainy, immediate quality of the resulting images carries an authenticity that polished architectural photography often lacks—these are spaces as they are lived, not as they are idealized.

Second, this approach inverts the traditional gaze. Rather than an external observer documenting migrants in their environments, participants themselves decide what moments matter and which spaces hold significance. As Trinh T. Minh-ha notes, this shift “from being pictured to picturing” is fundamentally decolonial—it returns control of representation to those who have historically been objects rather than authors of documentation.

Most significantly, the photographs reveal aspects of space that conventional architectural analysis might overlook. A corner of a living room transformed into a prayer area. A public plaza where children play games from their home countries. A kitchen window sill where herbs from another continent grow in repurposed containers. These images capture not just physical adaptation but emotional investment—the subtle ways people claim space and embed meaning within it.

The photographs collected through this project reveal patterns of spatial adaptation that transcend individual experiences. Across different cultural backgrounds, ages, and migration circumstances, certain spatial practices emerged repeatedly:

Thresholds as Sites of Negotiation: Many photographs focused on spaces between public and private realms—stoops, window sills, fire escapes, park benches. These liminal zones often hosted the most vibrant cultural adaptations, suggesting that threshold spaces offer unique opportunities for migrant self-expression precisely because they exist outside rigid institutional or domestic constraints.

Temporary Permanence: Participants documented ingenious adaptations of ostensibly temporary spaces—adhesive hooks supporting

elaborate family photo displays, removable floor coverings transforming institutional tile, fabric partitions creating privacy within shared rooms. These interventions reveal how migrants navigate the tension between impermanence and the human need to create home.

Collective Memory Objects: Across many photographs, certain categories of objects appeared repeatedly—religious icons, textiles, cooking implements, plants, and photographs from home. These objects function not just as decorative elements but as material anchors of identity and memory, transforming generic spaces into culturally specific ones.

Ritual Adaptations: Many photographs documented adapted ritual practices—religious ceremonies performed in living rooms, traditional celebrations held in public parks, cultural practices maintained but transformed by new spatial constraints. These images reveal how cultural continuity persists through spatial adaptation rather than despite it.

Together, these visual narratives offer crucial insights into how migrants actively construct belonging through spatial practice, even within constrained environments. They challenge the notion that “proper” integration requires abandoning cultural practices and instead demonstrate how cultural preservation and adaptation happen simultaneously through everyday spatial negotiations.