August to October 2025

August to October 2025

Ready for a getaway that’ll tickle your artistic fancy and let your inner adventurer do a happy dance? Pack your bags for a two-night romp in the mountain-hugged, art-sprinkled haven of Issaquah, Washington—where Lake Sammamish shimmers, the Issaquah Alps beckon, and serendipity is just a fifteen-minute zip from downtown Seattle.

Set your calendar for three days of wonder! Kick off with the third annual Issaquah Film Festival—where popcorn meets passion at the Hilton Garden Inn and Longman Performing Arts Center. Then, get ready for a curtain call at the 22nd annual Festival of New Musicals, courtesy of the legendary Village Theatre. On Saturday night, let your curiosity lead the way as you waltz through the Art Walk and Music Stroll, weaving between art and tunes in the historic Creative District.

Issaquah becomes the ultimate fishy catwalk in autumn—salmon strut their stuff, leaping and swirling in a spectacle that’s equal parts nature documentary and dance-off. For a front-row seat, plan your visit September 12-14 for the Salmon on Sunset Celebration, and don’t forget to stroll to the nearby quilt show—where threads and creativity collide, all within the charming Creative District.

October 4 bring your littlest daredevils to the Take a Kid Mountain Biking Festival at Duthie Hill Mountain Bike Park. Issaquah’s legendary Salmon Days Festival takes over downtown October 4 & 5, with fish-themed fun and quirky crafts galore.

Feeling artsy? September 20th is your passport to atelier exploration! Wander the Issaquah Studio Tour, peeking into studios where artists conjure magic from canvas and clay. Wrap your adventure with a soul-soothing Sound Bath Experience at Lake Sammamish State Park, marking the autumn equinox with cosmic tranquility.

Between September 16 and October 19, fall head over heels for the enchanting romance of Brigadoon at Village Theatre. Grab your tickets at VillageTheatre.org and prepare for a musical journey that’ll sweep you right off your hiking boots.

As climate-changing carbon levels in the atmosphere rise, could Washington’s forests be the answer?

wri en by Daniel O’Neil

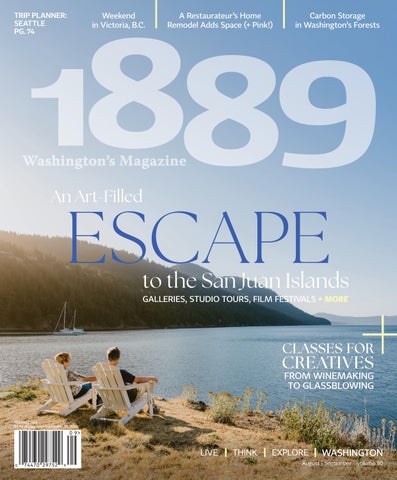

The San Juan Islands Museum of Art hosts Shapeshi ers, an exhibition showcasing contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous art, now through September 15. Take a tour through our pages to see some of the works on view.

wri en by Kerry Newberry

The San Juan Islands are teeming with creativity. Explore the artworks and culture of the islands, from galleries and studio tours to po ery and striking public art. wri en by Ryn Pfeu er

As an award-winning leader in small-ship cruising, UnCruise Adventures delivers unforgettable, all-inclusive voyages to the world’s most vibrant warm-weather destinations. Picture yourself aboard boutique vessels carrying just 22–86 guests: snorkeling in Baja’s crystalline Sea of Cortez, trekking through Costa Rica’s misty rainforests in search of scarlet macaws, tracking humpbacks

under Hawaiian sunsets, and even discovering Galápagos wildlife in timeless turquoise seas. Our all-inclusive fare wraps gourmet local dishes, handcrafted cocktails, expert-led excursions, and personalized service into every moment, making tropical exploration intimate, effortless and unforgettable.

(see “Where Creativity Meets the Current,” pg. 48)

Editor’s Le er Map of Washington Until Next Time 10 86 88

14 SAY WA?

The Sound of Music hits the stage in Leavenworth, Bremerton’s Blackberry Festival, a Pulitzer finalist.

18 FOOD + DRINK

No Boat Brewing Company, cra flour, Wenatchee’s Atlas Fare.

22 FARM TO TABLE

Washington-grown peas: tips and recipes.

28 HOME + DESIGN

A restaurateur from Sea le’s “first family of phở” brings her love of entertaining into her home remodel.

36 MIND + BODY

Figure skater Liam Kapeikis.

40 STARTUP

The Modern Dane’s eco-conscious linen bedding.

42 MY WORKSPACE

Bunny Dickson of Hama Hama Oyster Company.

46 GAME CHANGER

Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association.

68 TRAVEL SPOTLIGHT

The otherworldly trails of Hoh Rain Forest.

69 ADVENTURE

Cultural adventures in glass, culinary, music and more.

72 LODGING

Warm Springs Inn, Wenatchee.

74 TRIP PLANNER

Experience September in Sea le.

82 NW DESTINATION

Victoria, B.C.

JENNA LECHNER

Illustrator

Home + Design DIY

“What I love most about being an illustrator is collaborating with others to make a shared vision come to life. I try to infuse a feeling of joy and wonder into all my illustrations, which often involve nature and handcrafts. If I can bring my love of dogs, basketry or food into an illustration (as I did with the illustration for the DIY in this issue), then that’s an added bonus!” (pg. 34)

Jenna Lechner is a freelance illustrator in Portland. Her ink and watercolor illustrations have appeared on stationery, wallpaper, packaging and more. You can see more of her work on Instagram @jennamlechner.

WILL AUSTIN Photographer

Farm to Table

“Whidbey Island is my favorite location in Western Washington, so I was very excited to visit Rowdy Sprout Farm. Although I have photographed many ranches over the years, this was my first farm shoot. Kirsten and Tommy were wonderful hosts, and, naturally, I couldn’t resist sampling their delectable produce as I worked.” (pg. 22)

Will Austin’s award-winning photographic work has taken him around the world. Whether shooting from a saddle, a helicopter seat or the dizzying height of a tower crane, Austin enjoys the adventure of capturing people doing what they love. He lives in the Seattle area with his wife and son but hails from Colorado cowboy country.

RYN PFEUFFER Writer

Where Creativity Meets the Current

“I’ve been captivated by the San Juan Islands for nearly twenty years, and what keeps drawing me back is their stunning natural beauty and rich cultural heritage. I love how the land, sea and Coast Salish traditions inspire the local art and food—that sense of connection is everywhere. With so many passionate artists and community events, I see the islands as a living tapestry of history, creativity and community.” (pg. 48)

Ryn Pfeuffer’s work has appeared in AFAR, Business Insider, Cruise Critic, Men’s Health, National Geographic Traveler, The Seattle Times and Travel + Leisure. She lives on Whidbey Island with her partner and rescue puppy.

MELISSA DALTON

Writer

Home + Design

“I’ve worked on my own house remodel in Portland for many years and, throughout it, strived to balance function and personal meaning in every room. It was a joy to talk to Quynh-Vy Pham, a restaurateur from Seattle’s ‘first family of phở,’ about how she and SHED Architecture & Design achieved that balance in her own home. Plus, they used a lot of pink.” (pg. 28)

Melissa Dalton is a freelance design and architecture writer who covers a wide range of stories, from A-frames to passive homes, historic restorations and DIY projects. She lets her curiosity guide her life and writing.

EDITOR Kevin Max

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Allison Bye

WEB MANAGER Aaron Opsahl

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Joni Kabana

OFFICE MANAGER Cindy Miskowiec

DIRECTOR OF SALES Jenny Kamprath

BEERVANA COLUMNIST Jackie Dodd

C ONTRIBUTING WRITERS Cathy Carroll, Melissa Dalton, Rachel Gallaher, Joni Kabana, Lauren Kramer, Kerry Newberry, Daniel O’Neil, Ryn Pfeuffer, Ben Salmon, Corinne Whiting

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Will Austin, Jackie Dodd, James Harnois, Mac Holt, Jon Jonckers, Rafael Soldi

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS Jenna Lechner

Mail Headquarters

70 SW Century Dr. Suite 100-218 Bend, Oregon 97702

www.1889mag.com /subscribe @1889washington

592 N. Sisters Park Ct. Suite B Sisters, OR 97759

All rights reserved. No part of this publiCation may be reproduCed or transmitted in any form or by any means, eleCtroniCally or meChaniCally, inCluding photoCopy, reCording or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of Statehood Media. ArtiCles and photographs appearing in 1889 Washington’s Magazine may not be reproduCed in whole or in part without the express written Consent of the publisher. 1889 Washington’s Magazine and Statehood Media are not responsible for the return of unsoliCited materials. The views and opinions expressed in these artiCles are not neCessarily those of 1889 Washington’s Magazine, Statehood Media or its employees, staff or management.

IF WASHINGTON were a painting, oysters would be well represented on it. On page 42, we go behind the curtain at one of Washington’s iconic oyster farms, Hama Hama, but through the eyes of one of its mission-driven workers. Turn to My Workspace to learn how Bunny Dickson left San Francisco to follow her heart and conscience.

Late summer and early fall are the sweet spots for art festivals across the state. In this issue, we bring you a mini guide to art festivals and experiences in the San Juan Islands—from woven arts on San Juan Island to paintings and kinetic sculptures on Orcas Island, local art and artists are a great way to make a lasting connection and support artists. Turn to page 48.

While on San Juan Island, don’t miss the Shapeshifters exhibit at the San Juan Islands Museum of Art. Through September 15, explore contemporary Northwest Indigenous art through the lens of transformation, featuring the work of artists from Washington and British Columbia (pg. 62).

In “Growing Carbon” on page 56, join the debate about what we can best do for carbon reduction and storage to help mitigate the effects of global warming. One study of Washington’s west-side forests calculated that these trees currently hold nearly 830 million metric tons of carbon, the equivalent of 8.3 million train carloads of coal. What can we do to preserve these trees as a carbon sink?

In this issue, we see Seattle with new eyes for our Trip Planner (pg. 74). Maybe it’s the drawdown of summer visitors. Maybe it’s the cooling into fall to hop on a harbor cruise. Maybe it’s the prevalence of cool music events. Maybe it’s the discovery of a new menu from a favorite chef. Maybe it’s a bit of all of that. Make your plan to dive back into Seattle in September, when the Emerald City is at its best.

If you find something to celebrate, even if it’s just yourself, try this ingenious cocktail from the 108 Lounge—the champagne margarita (pg. 19). It is exactly what it sounds like and the antidote for a warm summer’s eve.

SAY WA? 14

FOOD + DRINK 18

FARM TO TABLE 22

HOME + DESIGN 28

MIND + BODY 36

Mount Rainier National Park is a place of transformation, where snowmelt fuels powerful waterfalls, and hiking trails reveal their vibrant beauty. Discover iconic cascades like the 72-foot-high Myrtle Falls, the Narada Falls, and the Christine Falls, with their rushing waters framed by lush greenery and dramatic rock formations. Each trail offers a chance to get close to the action, with the sound of waterfalls creating a backdrop for an unforgettable adventure. As you hike, look for blooming avalanche lilies along the trails, their bright white petals adding to the breathtaking scenery. The trails are alive with fresh air, stunning views, and the promise of discovery around every corner. Whether you’re chasing waterfalls or enjoying a peaceful walk, join us for an adventure that will leave you inspired and connected to the beauty of Mount Rainier.

written by Lauren Kramer

In August, Leavenworth’s hills come alive with The Sound of Music, as it continues its annual tradition at Leavenworth’s Ski Hill Amphitheater. Eleven performances are scheduled between August 2 and 30, bringing the endearing story of Maria von Trapp and her family to audiences at sunset.

www.leavenworthsummertheater.org/som

If you love the winelands, consider exploring them on an e-bike tour. Chelan Electric Bikes offers a back roads and winery tour of Manson where guests cycle 15 miles of country roads, stopping for tastings at three wineries along the way. The quiet back roads are dotted with magnificent lake and mountain views, and the four-hour experience is a pleasant, easy one where little exertion is required. The tours run through October.

www.chelanelectricbikes.com

Walla Walla Fair and Frontier Days

Walla Walla Fair and Frontier Days, Washington’s oldest fair, is August 27 through 31 and features demolition derbies, carnival rides, the PRCA rodeo and a performance by Foreigner, a 2024 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee. Tickets start at $12.

www.wallawalla fairgrounds.com

The Side Street Cashmere

Imagine a dilapidated, old fruit-packing warehouse reincarnated into a vibrant, communityfocused gathering spot and filled with an eclectic mix of interesting retail and dining options. That’s The Side Street in Cashmere, where a clothing and home decor boutique rubs shoulders with a secondhand bookstore, an arts and crafts supply store, a coffee shop, a cider shop and a venue for repurposed home building supplies.

www.sidestreet cashmere.com

Fort Vancouver Bicentennial Celebration

Absorb some state history at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on its 200th anniversary.

On August 16, entrance fees are waived, and visitors can participate in guided walks, demonstrations by costumed interpreters and music reminiscent of that period.

www.bit.ly/ fortvancouver bicentennial

Bremerton’s Blackberry Festival, August 30 to September 1, is an annual celebration held on the Bremerton boardwalk and 2nd Street. This fun event, a fundraiser for the Bremerton Rotary Foundation, includes 150+ vendors, bands, beer, blackberry wine and live music.

www.blackberryfestival.org

written by Ben Salmon

RACYNE PARKER is still figuring things out—just like you and me and everyone else.

Originally from Klamath Falls, Oregon, the 30-year-old singer-songwriter grew up around music. Her father played in local bands, and when she could, she’d sing alongside him at his gigs. She began writing songs “as a little bitty kid,” she said, and started playing guitar in the fifth grade.

“I knew (music) was something I always wanted to do, but chasing that dream has a lot of stigma associated with it,” she said. “I was pretty afraid to do it for a long time.”

As a teenager, Parker turned her focus away from music and toward sports, and she then went to Willamette University to study biology and prepare for medical school. But while in college, she rediscovered songwriting (“For real” this time, she said) and started playing out in public around town. at’s what felt right to her, but still, she was unsure.

“With some careers, there’s a ‘to-do’ list. You check things off : Get good grades. Go to college. Apply for a job,’” Parker said. “ ere’s a right path. And music feels like this very unclear and uncertain path.”

After graduation, though, she had accumulated some good songs, and her dad encouraged her to record them. At the same time, she started playing more gigs, and she was having a blast during them. She had an opportunity to relocate to Denver, and she decided to try to hit the ground running there—as a musician.

“I was like, ‘I’m going to move there. I’m going to go to everybody’s shows. I’m going to meet everybody. I’m going to start playing out,’” she said. “But it was March of 2020, so those

plans got put on hold (by the COVID-19 pandemic).”

Over the next five years, though, Parker’s plan unfolded just a little more slowly than expected. She did meet people, and she did play gigs, and she also wrote a bunch of songs that would eventually become her debut full-length album, Will You Go With Me?

Primarily recorded with Randall Kent at Deaf Dog Studios in Nashville, it’s an eleven-track collection of well-crafted and ultra-catchy Americana music that lives somewhere near the midpoint between Kacey Musgraves’ searching, starlit twang-pop and Miranda Lambert’s tough-talkin’ traditional country.

“ e whole theme of the record for me is just me trying to figure it out and asking people if they’ll come along with me as I do that, because I don’t want to do it alone,” Parker said. “It’s like, ‘I want to do this, and I hope somebody will do it with me.’ I was living that feeling for years, so I just wrote songs about it.”

About a year ago, Parker moved again, this time to Seattle, where she feels like she’s “starting over in a lot of ways,” she said. She took a step back from constant gigging and is focusing on playing meaningful shows—“saying ‘yes’ to things that are exciting,” she said. She’s also pursuing a lifelong interest by working part time at a bakery while she gets a band together and works to build community in her new city.

And she knows music will be there for her, always.

“Some days, I’m like, ‘I was born to do this and I’m going to do it no matter what.’ And other days, I’m like, ‘Well, that’s kind of crazy,’” Parker said. “But when I come back to it, I know I’m going to be making music regardless of who hears it. Forever.”

and Intertwining Cultures

A Sea le Pulitzer finalist discusses dialogue, tangents and her conceptual sandbox

interview by Cathy Carroll

THE NOVEL Mice 1961 by Sea le’s Stacey Levine was one of three finalists for this year’s Pulitzer Prize in fiction. Set in southern Florida at the height of the Cold War, it centers on two orphaned half-sisters, a boarder and the neighbors who orbit their world. The Pulitzer Prize jury lauded the book as “a stylized and startling depiction of lives lived at a high pitch of emotion in the shadow of global catastrophe.”

The story unfolds on a single day, tracing the charged relationship of the two sisters, as seen through the eyes of their obsessively observant lodger. A Greek chorus of neighborhood characters cavort and joke through a local party, and the arrival of an unse ling stranger spurs the three women toward momentous change.

Levine, who teaches creative writing and English composition at Sea le Central College, has earned many accolades for her other voice-driven works. Her short fiction collections include My Horse and Other Stories, which won a PEN Fiction Award, and The Girl with Brown Fur, which was shortlisted for the Washington State Book Award, as was her novel Frances Johnson

What inspires the sound and style of dialogue in your fiction?

I’ve been inspired by Jane Bowles, David Mamet and Brazilian author Clarice Lispector. I think it’s worth noting that most dialogue in fiction is not really how people literally speak. Real conversation is filled with uh, oh, wait, umm, whatchamacallit and lots of backtracking and physical gestures. So dialogue in most books, while we might call it realism, isn’t realistic. For this reason, I’m sometimes interested in recording actual phrases that people speak, which don’t always make clear sense or which sound comical. I’m also interested in creating characters that say exactly what they feel or think with no censors. That results in funny and brutally direct conversations.

by The Brooklyn Rail. They have really deep thinking interviewers. I guess when we’re first discovering creative writing, there’s a realization about how much life we can explore through a fictional lens. And that can be really breathtaking. Yes, I remember while I was working on my novel Mice 1961, still in the middle of it with so much more work to go, I did grow really excited about the book’s potential to the extent that I kind of felt sick! In other words, it was a li le overwhelming.

In an interview with The Brooklyn Rail, you described going o on descriptive tangents during a night class in essay writing and discovering a sensation you couldn’t let go. Do you still experience that when you write today?

Thanks for mentioning the interview questions put to me

Tell us how and why Florida—so di erent from the Northwest—became a “conceptual sandbox” for two of your novels so far. I think this is because I visited South Florida several times in my formative years and the culture seemed so out-there and cray to me, a separate location outside the bounds of my life and world. But if my creative/conceptual playspace hadn’t been south Florida, I’m positive it would have been some other place. Many novelists have favorite or repeated se ings or themes in their books which they o en return to.

written and photographed by Jackie Dodd

TUCKED JUST OFF Interstate 90 in Snoqualmie, a few miles from the trailheads of Rattlesnake Ridge and the base of Mount Si, No Boat Brewing Company is an unassuming but beloved outpost in the Northwest beer scene. Founded in 2016 by the Skiba family—David, Gary and Mary—the brewery quickly became a community fixture, known as much for its thoughtful beer as for its welcoming taproom and expansive outdoor space. With a name like No Boat, head brewer and co-founder David Skiba is asked more often than he’d like to count if he does, in fact, have a boat. He does not—and at this point, even if he wanted one, it probably wouldn’t happen purely out of exhaustion from having to explain it.

From the outside, No Boat doesn’t look like much. Located in a converted industrial building near a strip of auto shops and landscaping suppliers, it’s not a place you’re likely to stumble upon—it’s a destination you seek out. Follow the trail of hikers, dogs, strollers and wandering beer lovers past the parking lot-turned-beer garden, through the roll-up garage doors, and you’ll find a taproom with all the right elements: long tables for lingering conversations, a wall of rotating taps, staff who know your name (or, more likely, your dog’s name) and just enough fermentation tanks in the background to remind you this is where the magic happens. The space is massive, with more than enough room to host events—like the annual Lagerhead Fest, which benefits the conservation charity Washington Wild—as well as ample square footage to expand as they grow.

Skiba came to beer by way of wine. After working in the wine industry in both California and Washington, he shifted his focus to brewing, a background that helps explain No Boat’s balance between traditional brewing styles and more nuanced experimentation. On any given week, the tap list might include a crisp lager, a hop-forward pale, a dark and malty seasonal release or

something aged in oak. While No Boat doesn’t stake its identity on any one flagship beer, it has earned a reputation for crafting expressive ales and lagers with a Northwest sensibility.

With nearly ten years of brewery ownership and a background in winemaking, you might imagine Skiba to be older than he is. He started his alcohol endeavors as a mere babe and is now just into his early-mid 30s. He’s on the young side for someone planning the ten-year anniversary celebration of their own brewery.

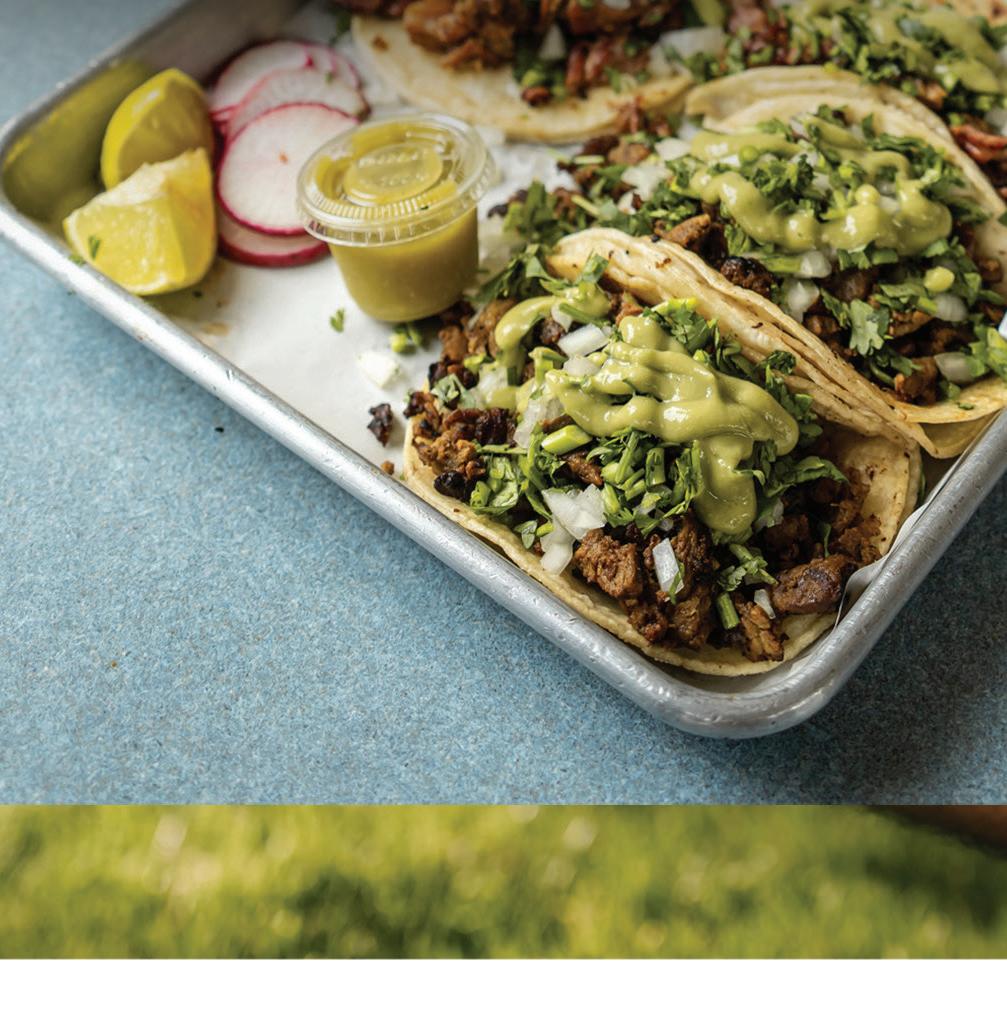

e taproom is open seven days a week, afternoons into the evening on weekdays, and from noon until late on weekends. It’s a rare day when the beer garden isn’t populated with young families, trail runners and a healthy number of dogs curled up in shady corners. ough there’s no in-house kitchen, No Boat partners with a rotating lineup of food trucks that serve everything from tacos and smash burgers to crispy chicken sandwiches and birria. Visitors can check the brewery’s website or social media for the daily truck schedule.

Community is central to No Boat’s identity. e staff is small and tight-knit, and many have been there for years. Regulars know them by name—Brittany, Kami, Nick, Liz, Zach—and

Combine tequila, lime juice, orange juice and agave in a shaker. Shake with ice, and pour into a salted-rim glass. Top with champagne, and garnish with lime. NO BOAT BREWING COMPANY 35214 SE CENTER ST. SNOQUALMIE www.noboatbrewing.com

most are happy to chat about what’s on tap, what’s coming next, or what trail to hit after your pint. e brewery is dog-friendly, kidfriendly and attitude-free.

at sense of inclusiveness extends to events, too. No Boat doesn’t try to be everything to everyone, but its calendar often includes thoughtful additions: collaborations with other local brewers, conservation-minded initiatives and special releases tied to causes they care about.

While No Boat isn’t trying to reinvent the brewery model, it does a lot of small things well—and that adds up to something unique. e brewery sources locally whenever possible, builds strong relationships with local nonprofits and shows up consistently for its customers and its community. e result is a brewery that feels less like a business and more like a shared backyard.

For those passing through Snoqualmie on the way to the mountains, No Boat is a natural stop. But for locals, it’s more than that—it’s part of the rhythm of daily life. e kind of place where you can meet a friend after work, show up in your hiking boots or spend a lazy Sunday trying something new on tap.

And no, there’s still no boat. But as it turns out, you don’t need one.

written by Lauren Kramer

WHEN KEVIN MORSE founded Cairnspring Mills ten years ago, his vision was craft flour: stone-milled flour made from sustainable, locally grown grains. The mill would prioritize locally grown food, deliver a fair margin to the farmers supplying the grain and mill the grain in small batches that preserved its nutritional integrity. A decade in, demand for Cairnspring flour is so strong that a second mill is in the planning.

While commodity-produced flour occupies more shelf space in grocery stores and tempts with cheaper prices, it’s milled in massive batches, stripped of its nutritional content and composed of mixed grains, their provenance unknown. By contrast, the team at Cairnspring selects specific grains, all derived from farms with regenerative farming practices, for their milling and baking quality, flavor and aroma. The grains are ground in a European-style stone mill that brings more flavor to the flour. “Flour is not just a ubiquitous, white product,” Morse said. “When you treat it like a fresh product, it tastes and performs better.” Serious bakers say they can taste the difference, vouching for the superior flavor Cairnspring’s flour brings to their bread, buns and pizza bases.

“Cairnspring is a testament to the power of community,” Morse said. “Here in Skagit County, we’ve built a business based on humanity, one that’s good for the people and the planet, and is founded on a wish to maintain a viable way of life here. This is about food safety, food security, good stewardship and prosperity, and it’s deeply personal. Yes, we’re milling flour, but what we’re really doing is revitalizing our community.”

11829 WATER TANK ROAD

BURLINGTON www.cairnspring.com

Convenience store meat snacks have long been subpar and far from tempting, but Bellingham’s Carnal restaurant is determined to up the ante. Its Michelin-trained chefs just launched Carnal Jerky, beef sticks infused with black truffles, fermented black garlic and proprietary spices. The portable gourmet snacks are sugar free and made with premium beef. www.carnaljerky.com

Cookies are seldom a lower-calorie choice, but Light Delight in Selah has a formula for great cookie snacks without the guilt. This small business avoids refined sugar and has many selections in gluten-free and dairy-free versions. Top sellers are caramel chocolate, chocolate chip and snickerdoodle, and if you prefer to bake at home, they offer mixes for select confections including cookies, brownies, carrot cake and cinnamon rolls.

117 E. 3RD AVE. SELAH www.lightdelight.net

Landsea Gomasio is the Pacific Northwest version of “everything but the bagel” seasoning, and it’s addictive, particularly when sprinkled on top of salads, rice, eggs and other proteins. The salty, nutty flavor of this Orcas Island-made blend consists of nutrientrich seaweed, nettles and sesame seeds. The company also offers Landsea Za’atar and Landsea Popcorn, and its seasonings are available at select grocery stores in the San Juan Islands and beyond (see its website for a full list).

www.landseagomasio.com

Lum Farm on Orcas Island, populated by a herd of Nubian goats and Friesian sheep, has nailed the formula for rich, creamy chèvre. The farm sells herbed and plain chèvre, feta cheese made from goat and sheep’s milk, sheep’s milk yogurt, goat’s milk ice cream and cajeta, a goat’s milk caramel. Shop straight from the farm store online, or visit them in person.

1071 CROW VALLEY ROAD EASTSOUND www.lumfarmorcas.com

Known for its butter-crusted fruit pies, wholegrain breads and incredible pastries, Anjou Bakery is an unexpected gem in Cashmere’s culinary scene. Look out for the almondine, a seductive almond cream confection, and the black bottom cupcake, a decadent chocolate cake filled with cream cheese. Arrive early, as baked goods sell out fast.

3898 OLD MONITOR ROAD CASHMERE www.anjoubakery.com

Nothing beats a light, refreshing sorbet on a warm day! Head to Clever Cow Creamery in Eastsound for a divine assortment of seasonal sorbet and ice cream from Lopez Island Creamery. Flavors like lemon drop and cucumber lime deliver a one-way ticket to blissville.

109 N. BEACH ROAD EASTSOUND www.clevercowcreamery.com

When hunger strikes in Vancouver, choose a nutrient-dense bowl packed with healthy ingredients. Mighty Bowl offers dishes with flavorful items like chipotle soy curls and cashew pesto, and also serves smoothies and toast, with a food cart, a food truck and a retail location.

108 W. 8TH ST. VANCOUVER www.themightybowl.com

On Orcas Island, don’t miss a brunch stop at the fabulous Cafe Aurora, which opened in summer 2024. Diners feast indoors or outside on the sunny patio, and the menu is filled with healthy, diverse options like oyster mushroom lettuce wraps, bananas foster waffles, homemade granola and avocado toast with harissa tahini.

123 N. BEACH ROAD EASTSOUND www.cafe-aurora.com

written by Lauren Kramer

LOCATED IN the century-old Metropolitan Building in downtown Wenatchee, Atlas Fare is one of the city’s hot spots, a restaurant with a modern, cosmopolitan feel and a diverse, globally flavored menu. Owners Top and Jenny Rojanasthien spent eighteen months renovating before opening in 2020, adding a white-tiled open kitchen, a wall with clocks depicting different time zones around the world, a sophisticated charcoal-and-white color scheme and 15-foot ceilings. The result is a popular restaurant that feels spacious, contemporary and sophisticated, seating up to seventy-eight between its dining room and bar.

Atlas Fare’s global infusion theme permeates the whole menu, from the southern-style shrimp and grits to the Italian-style paella and chicken risotto and the quintessentially Northwest crab chowder and salmon. There are options for vegetarians, vegans and those avoiding gluten on the menu.

We dined on a hot summer’s night, preferring lighter fare: a caesar salad featuring grilled romaine lettuce and a falafel entrée that arrived with pink flowers and was almost too pretty to eat. The chickpea fritters, served with quinoa and a cashew tzatziki, were a perfect antidote to the heat, while our furikake-crusted halibut, served on a bed of pea purée, was flaky and delicious, its Japanese-influenced wasabi peas and sesame seaweed topping adding a pleasantly spicy crunch to the dish.

“We love running the restaurant as a husbandwife team,” Jenny said. “We both have a pas sion for hospitality, and it’s really rewarding walking into the dining room and, instead of seeing cellphones out, seeing people genuinely enjoying our food and engaged in conversation.”

Atlas Fare is open for dinner Wednesday through Sunday, and reservations are recommended.

137 N. WENATCHEE AVE., #103 WENATCHEE www.atlasfare.com

The bright legume brings flavor and crunch to dishes from Tacoma to Whidbey Island written by Corinne Whiting | photography by Will Austin

KIRSTEN MURRAY and Tommy Contreras, owners and operators of Rowdy Sprout Farm, call peas “a gateway vegetable” since “they are so sweet and crunchy, even the most veg-resistant child reaches for more a er being encouraged to take a no-thank-you bite.” They love to eat peas fresh in the field, sweet and warmed by the sun. “The first meal we ever shared included a chilled wheat berry, carrot, radish, turnip, pea and feta salad,” Murray said. “We come back to that memorable recipe time and again.”

On their diversified collaborative farm, operating out of a 1-acre incubator plot at certified organic blueberry farm Mutiny Bay Blues on the south end of Whidbey Island, peas are one of the first crops to go in the ground as the fog of winter lifts. “The plants thrive in cool weather and yield from late spring through early summer,” Murray explained. “Washington’s generally temperate weather grants us a longer window in which to produce and enjoy them!”

The couple’s collaborative farm came to be out of a shared belief that diversity lends to sustainability. Both have backgrounds working with food in spaces such as school and community gardens and food banks. While one of them grows flowers, fiber and botanical dyes, the other grows mixed vegetables—like peas.

Sean Prater, culinary director at Captain Whidbey since October 2021, loves the versatility of peas. “They read spring, but in Washington they are more of a summer treat,” he said. “The plant is great because once you harvest all the pods, you can turn around and use the tendrils as sautéed greens. They are

hardy, and their flavor is very reminiscent of the little green gems that everyone waits for.”

On enchanting Whidbey Island, where they source from at Captain Whidbey depends on the peas, but they try to go the local route whenever possible. They bring in pea shoots from One Willow Farm, and collect pea blossoms from their own garden crop.

“Our vision for our culinary program is ever changing, but the focus is local,” Prater said. “Seasonality plays a huge part in the production, but the main event is the local fare. 17,000 acres of farmland on island produce the tastiest berries, most vibrant beets, creamiest cheeses and a secret stash of wild mushrooms that is the envy of foragers the world over.” At the charming island eatery, which Prater calls “an absolute gem,” they pay homage to these artisans, shouting out their families and farms on the menu. Though their local co-op does a lot of the leg work, they want to honor their craft and products the best way they can.

Back on the mainland, executive chef Dexter Mina of Tacoma’s Woven Seafood & Chophouse agreed that the versatility of peas “naturally adds a pop of freshness and brightens up any dish.” At his

scenic new outpost on the Ruston Way waterfront, Mina specifically chose to partner with Charlie’s Produce. Woven Seafood & Chophouse’s venue blends the rich culinary traditions of the Puyallup Tribe, Hawaii and the Philippines.

Prater also recognizes the versatility of peas to be used yearround. Think: split peas in the cold months, or young peas to make soups and sauces in the spring to pair with lamb. “Summer pea salads laden with stone fruit is the perfect accompaniment to a BBQ or eclectic winemaker dinner,” he added. “Pearls hidden within their shells.”

Prater advises not selecting peas that are parched (the pods will be wrinkly). Bulging pods are always a good sign. “When cooking the peas, it’s a good idea to blanch them first, and look out for any peas that float, as this is a sign of imperfect peas,” he said. He likes to add salt, as well as a dusting of baking powder

into his blanching water. “The soda raises the pH of the peas and makes it so they stay vibrant,” he explained. “Shocking them in ice water will help hold that vibrant color.”

Another tip: Don’t throw away the pods after shelling, since dozens of uses exist. Prater suggests blending them with a little water and wasabi or green chilies to make a fiery consommé to be paired with ceviche. Or blend them with sugar and freeze, and you can make a fluffy granita by scraping the frozen mixture with a fork—a perfect accompaniment to oysters on the half shell.

Murray offered wise words to those growing peas at home. “Animals love them as much as we do,” she said. “Protect your peas! Particularly just after seeding, you will get a lot of pest pressure from birds and rodents.” If you seed directly in your garden, she advised, be sure to apply a barrier to deter pest access to the ripening seeds. Examples of smart coverage: a chicken wire cover during the day or frost cloth at night. And if you seed in a greenhouse, also be sure to protect the seeds.

Pork Guisantes (Filipino-Style Pork ’n’ Peas)

Woven Seafood & Chophouse / TACOMA

Dexter Mina

SERVES 4-5

• 2 pounds pork belly, cut into ½-inch strips

• 2 pounds pork shoulder, cut into medium-size strips

• 1 yellow onion, small dice

• 4 tablespoons garlic, minced

• 2 tablespoons fish sauce*

• 2 tablespoons soy sauce (or tamari for a glutenfree option)

• 2 tablespoons tomato paste

• 4 tablespoons peppercorn, freshly cracked

• 4 bay leaves

• 1 to 2 cinnamon sticks (or 1 to 2 teaspoons ground cinnamon)*

• 2 red bell peppers, julienned

of the pork fat. Using the reserved fat, sauté the onion and garlic until fragrant. Next, add your pork belly and shoulder back into the pot, and stir to combine.

Deglaze the pot with fish sauce and soy sauce, and scrape the bottom of the pot to get all those flavorful bits. Add the tomato paste, cracked black peppercorn and bay leaf to the pot. Pour in enough water to cover, and bring to a boil.

While waiting for it to boil, in a separate pan or in the oven, toast the cinnamon sticks until they start to unravel and release their aroma. Add to the pot. (If using cinnamon powder, add when adding the black peppercorn and bay leaves.)

(Typically, peas are out of the danger zone after they reach a height of 2 to 3 inches.)

Prater leans heavily on Asian cuisine at home, so he’s fond of quick sautés using snap and snow peas. His crowd-pleasing appetizer involves tossing snap peas and shishito peppers with oil and salt, and then broiling them for several minutes until they bubble and blister. For the finale, a heavy dash of fish sauce mixed with sweet chili glaze.

“Green peas are best when they’re super fresh, so be sure to look for pods that are bright green and feel nice and full. If they look a little dull or feel soft, they’re probably past their prime,” Mina said. If planning to use peas within a couple of days, he said, after shelling they can be stored in an airtight container and kept in the fridge.

When green peas are in season, at home, Mina likes to add them as a last-minute garnish; this adds yet another layer of texture and brightness—something peas subtly, yet successfully, seem to do best.

• 2 cups fresh green peas (or frozen if not available)

• Salt, to taste

Start by cutting and preparing all pork and vegetables. If using fresh peas, shuck them, and set aside.

Add the pork belly to a large sauce pot, and render out the fat until the pork has been browned. Reserve some of the fat for later sautéing. Remove the pork belly, and add the pork shoulder. Render and sauté until browned, and then remove, leaving in some

Braise until the meat is tender. Once the meat is tender, add in the red bell peppers and green peas.

Season with salt, pepper and, if desired, additional fish sauce, to taste. (I recommend fish sauce.)

*Notes from chef Dexter Mina: I prefer cinnamon sticks over powder, as the powder is a little stronger in flavor than the sticks. You don’t want the dish to be too “cinnamon-y.”

For fish sauce, I prefer using the Vietnamese 3 Crabs brand as it’s a little stronger and pungent to even out the sweetness of the dish.

farm to table

Spice Waala / SEATTLE

Aakanksha Sinha and U am Mukherjee

SERVES 3-4

• 3 tablespoons vegetable oil or any other high-heat cooking oil

• 2 teaspoons cumin seeds

• 1 onion, diced

• 3 tomatoes

• 2 Thai green chilies, diced

• 1 tablespoon ginger paste

• 1 tablespoon garlic paste

• 1 tablespoon methi, crushed

• ½ teaspoon Kashmiri mirch

• 1 tablespoon coriander powder

• 1 tablespoon cumin powder

• 1 tablespoon garam masala

• 1 cup peas, at room temperature

• 1 12-ounce packet of paneer, at room temperature and cut into ½-inch cubes

• 2 strands coriander leaves, finely chopped

• Salt, to taste

On the stovetop, in a 12-inch-deep sauté pan, heat oil to 300 degrees over medium heat. Add cumin seeds to lightly fry for about 30 seconds (make sure it doesn’t turn deep brown).

Smoked Scallop Carpaccio with Glazed English Peas, Rhubarb Sriracha and Braised Daikon

Captain Whidbey / WHIDBEY ISLAND

Sean Prater

SERVES 4

FOR THE SMOKED SCALLOPS

• 12 diver scallops

• 2 teaspoons kosher salt

• 1 quart water

FOR THE BRAISED DAIKON

• 1 daikon radish, peeled and sliced into 1-inch rounds

Lower the flame to low-tomedium, and add the diced onions to the pan. Sauté until goldenbrown, about 10 minutes. Add the tomatoes, Thai chilies, ginger and garlic paste, and cook for about 10 minutes. (Add a few spoons of water if the pan is too dry).

Add all the spices (methi, Kashmiri mirch, coriander powder, cumin powder and garam masala).

If the spices make the ingredients in the pan too dry, add quarter cup of water, and let it all cook for about 10 minutes. Once the spices are cooked, add about 2 cups of water, and cook for about 10 minutes.

• 1 cup balsamic vinegar

• 1⅓ cup tamari soy sauce

• 1 cup brown sugar

FOR THE RHUBARB SRIRACHA

• 1 cup rhubarb, chopped

• 1 cup red wine vinegar

• 1 teaspoon cayenne

• 2 garlic cloves, chopped

• 1 cup sugar

FOR THE PEA PURÉE

• 3 cups English peas (later divided into 2 cups and 1 cup)

• 1 teaspoon sugar

• 2 teaspoons kosher salt

TO SERVE

• Olive oil

• Salt

Add the peas and paneer, and mix everything to coat the paneer and peas evenly. Cook on low flame for about 5 minutes, and switch o the stove. Add salt to taste. Garnish with fresh cilantro, and serve with hot basmati rice.

FOR THE BRAISED DAIKON

Peel the daikon, and ensure it is uniform in diameter. Cut into 1-inch rounds, and add to a medium pot with the balsamic, tamari and brown sugar.

Simmer on low for 45 minutes. Remove from heat, and allow the daikon to marinate in this mix overnight. Reserve a teaspoon of the braising liquid for serving.

• Pea shoots

• Edible flowers

FOR THE SMOKED SCALLOPS

Begin by cleaning the scallops and removing the li le side muscle that is a ached to each scallop. Make a brine by dissolving the salt in the water. Brine the scallops overnight or for 8 hours.

Drain the scallops, and pat dry. Allow the scallops to fully dry and become tacky—this will allow the smoke to adhere.

Smoke the scallops using a light wood (apple or peach) at 160 degrees or less for about 12 to 15 minutes.

Cool the scallops, and allow the smoke to mellow out and disperse.

FOR THE RHUBARB SRIRACHA

Chop up the rhubarb, and add to a medium pot with the vinegar, cayenne, chopped garlic cloves and sugar.

Simmer for 10 minutes or until the garlic is tender. Add this mixture to the blender, and blend on high until very smooth. Set aside, and allow to cool.

FOR THE PEA PURÉE

Blanch all the peas in salted water for 1 minute, and shock in ice water. Divide the peas into 2 cups and 1 cup.

Add the 2 cups of peas to the blender with ¾ cup of water, the sugar and salt. Blend on high until very smooth and not gri y or grainy. Set aside, and chill.

TO SERVE

To build the dish, slice each scallop into 5 or so slices, as thin as you can. Do the same for the daikon. Dress the remaining 1 cup of blanched peas in good olive oil, salt and a teaspoon of the braising liquid from the daikon.

Spread a thin layer of the pea purée across a plate, and top with the scallops and daikon slices, alternating each. Top with the dressed peas, and add some dollops of the sriracha on the plate, but to the side of the dish.

Top the dish with pea shoots and edible flowers, preferably pea or chive blossoms.

Restaurateur Quynh-Vy Pham finds vast open spaces in the modest square footage of a renovated house.

A Seattle restaurateur remodels her house to make space for family and friends written by Melissa Dalton | photography by Rafael Soldi

WHILE HER businesses and social life were on hold during COVID-19 lockdowns, Quynh-Vy Pham knew exactly what she wanted in a post-pandemic future. “A party house,” said Pham with a smile. No surprise there, as Pham comes from a family well-known for their hospitality.

In 1982, Pham’s parents opened Phở Bắc, the city’s first phở shop, in Seattle’s Little Saigon neighborhood. The restaurant soon became a popular local spot and added more locations, and forty years later, the Pham family was dubbed “the first family of phở” by The Seattle Times. Sometime in the aughts, that first restaurant acquired an assemblage of a leftover parade float shaped like a ship’s bow, to become colloquially known as “The Boat.”

The second generation, including Pham, one of her three sisters and their brother Khoa, since expanded their offerings to include a coffee shop, the Phở Bắc Súp Shop and a chicken and rice shop (the latter now in The Boat since 2022). There’s also a hidden bar called Phởcific Standard Time inside one of the Phở Bắc locations, where you can order a “Quynh Bee,” Pham’s take on the classic Queen Bee cocktail, made with jasmine-infused honey. “That’s my signature drink,” said Pham. “I make it for anyone who comes over.”

But in 2021, Pham had inherited her brother Khoa’s house, after his unexpected passing. He had been fixing it up off and on, adding skylights here, painting the siding charcoal and the window frame a bright fuchsia. Later that summer, Pham decided to continue what he had started. “Being in the restaurant biz, [the pandemic] was really tough, so I had a lot of free time on my hands,” said Pham. “I thought, might as well go ahead and start this project.”

The house is a familiar fixture in the Leschi neighborhood, and its existing, boxy facade belies a colorful past. Built in 1927, it was first an art studio for Louise Crow, a renowned portrait painter born in Seattle. In the 1940s, the home’s shingled exterior was painted white to become a Baptist church. By 2016, when Khoa bought it, it was about 1,000 square feet, on a petite 2,835-square-foot lot tucked tightly between two other houses. Pham wanted to update it in a way that paid homage to her personal history, as well as the neighborhood, so she reached out to SHED Architecture & Design for the job, noting that their office is kitty-corner to The Boat. “I just remember Khoa talking about it,” said Pham. “He said, ‘I’ll just reach out to SHED. They’ve been our neighbors for twenty years.’”

For the remodel, architect Rebecca Marsh and firm principal Prentis Hale used the fact that the house came with several non-conforming land-use

home + design

conditions to their advantage. Those conditions drove them to design a clipped flat roof at the second story, creating a soaring ceiling in the dining room, and two bedrooms and a bathroom. As might be expected given Pham’s family business and love of entertaining, the kitchen was enlarged and moved to the rear of the home, to connect to a new backyard patio via large sliding glass doors. “Quynh really wanted a home that would work well for entertaining,” said Marsh.

“She wanted a house that was expandable—that felt natural for her and one other person if they’re cooking, as well as a party of thirty people.”

Custom storage in unique configurations enhances the sense of expansiveness. A 40-foot-long bench by Space Theory lines the living and dining room walls, to act as media console, art display and seating at the table. High cabinets, also by Space Theory, accessed by a library ladder underscore the dining room’s tall ceiling, while a 12-foot-long kitchen island is perfect for accommodating family cooks at work and mingling guests. “This is a modest house in terms of square footage, but it is dynamic,” said Marsh.

Certain preserved pieces nod to the building’s past, such as the brass pendant light from the church

The soaring ceiling height in the dining room opens up to friends and family. Sizeable windows in the living room help create a naturally lit space that feels larger.

that hangs over the staircase. When the team installed a larger window on the front facade, the old one from Crow’s studio was worked into the redesign. “We were debating what to do with it—will it be an art piece, where will it go?” remembered Marsh. During a design meeting over drinks, Pham passed on a few concepts for the staircase, and the team “jokingly” suggested using the old fuchsia-painted window as the stair guard rail and an interior screen. Pham was all in, and upon review of the measurements the next day, it was a perfect fit. It’s now painted a paler pink, with reeded privacy glass, and incorporates seamless closet space at the entry.

Also preserved throughout? The family’s love for the color pink, now woven into the home from the front window to the kitchen cabinets. “When my parents first opened the restaurant in 1982, my dad painted the restaurant pink,” said Pham. “He just loved pink. Throughout the forty-something years, the restaurant has always been some version of pink, and pink has always been the theme through the business and translating into our lives.” Perhaps because, much like a good gathering of family and friends, food and drink, it’s a color that, said Pham, “just brightens everything up.”

“When my parents first opened the restaurant in 1982, my dad painted the restaurant pink. He just loved pink. Throughout the forty-something years, the restaurant has always been some version of pink, and pink has always been the theme through the business and translating into our lives.”

— Quynh-Vy Pham, homeowner

ABOVE The kitchen features a 12-foot-long island that also provides ample storage. AT FAR RIGHT, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT A brass pendant light illuminates a nook. An old window was repurposed for an interior stairway. The back patio is a peaceful respite.

illustration by Jenna Lechner

IF YOU’RE looking for a creative way to save some space in your kitchen (who isn’t?), this easy-to-make pot rack and shelf may just do the trick.

Cut a 1x12 board to 36 inches long. (The real dimensions of a 1x12 will be 3/4 inch x 111/4 inches wide.) Using 150-grit sandpaper, sand every plane of the board, making sure to buff the edges so they are not sharp. Stain or paint, and seal the shelf to the desired finish. Make sure all the steel plumber’s pipe and pieces have the same diameter, such as a ½ inch, so they will connect properly. Clean the metal pieces with all-purpose cleaner. Spray paint every piece for a consistent finish and to keep the pipe from rusting in the kitchen humidity.

Measure 2 inches from the sides of the shelf, and attach an L bracket

on either end. These brackets should be placed at 32 inches apart so that they will connect with the wall studs, which are typically spaced 16 inches apart on-center.

The shelf requires an additional wall support on either side. The supports are connected across the front with a 32-inch pipe. (This long pipe is where the kitchen utensils will hang from with hooks). Each support is constructed from two flanges, two pre-cut pipes in two lengths (6” and 8”) and a three-way elbow connector. Screw the 8-inch pipe into the wall flange. Attach the elbow at the other end. Screw in the 6-inch pipe so it runs vertically to meet the

underside of the shelf. Attach the flange to the end of the 6-inch pipe. This flange will be screwed into the underside of the shelf. Repeat for the other support.

Flip the shelf over, and lay it on the ground with the underside facing up. Put the back edge up against the wall so the L brackets are flush with the wall. Line up the flange that will be connecting to the shelf, so that it is in line with the L bracket. Slide the flange along the bottom of the shelf until the bottom flange is flush with the wall. This should put the upper flange at 2 inches from the side and front edge of the shelf, but the most important thing is that the support lines up with the L brackets. Mark the flange location on the board. Using a 3/4-inch screw, attach the flange to the board without tightening all the way. You want it to have some give when attaching the crosspiece. Repeat on the opposite side with the second side support.

Add the 32-inch crosspiece between the side supports, threading it into the remaining hole on the three-way elbow. Once the crosspiece is in place, tighten the flanges at the shelf so they are secure.

Use a stud finder to find the wall studs, and mark their location. Screw in one side, including both the L bracket and wall flange. Use a level to make sure the shelf is straight. Screw in the opposite side. Add S hooks, bending them so they fit tight around the pipe, otherwise they may fall off every time a pot is removed. Hang up kitchen utensils, the family cast iron or some herbs to dry, and marvel at your new functional, space-saving display.

Scott Hudson started Henrybuilt in Seattle in 2001, marrying American craft tradition with the look of sleek European kitchen systems, to become the first “American kitchen system.” In 2019, they opened Space eory, a new kitchen system line of cabinetry and more that’s simplified and affordable, but still high quality. Built in Seattle, the company’s offerings are known for their hyper-organizational capabilities and offer more than forty finish selections. www.spacetheory.com

e fun thing about the modular Alphabeta lighting system from Hem is that the shades come in eight shapes and a wide range of colors and can be customized to your preference. ( e company says there are 1,024 different configurations possible.) Which will be yours—monochrome, or a color combination only you can imagine?

www.hem.com/en-us

A utensil holder is an undersung, hardworking piece in the kitchen. Sure, you could use any old mason jar for the job—or, upgrade to the French Kitchen Marble Utensil Holder from Crate & Barrel. It will hold more tools, and look good doing it.

www.crateandbarrel.com

is 3-quart, enameled cast iron by Staub at Williams Sonoma is perfect for simmering sauces and soups or baking no-knead bread, as it’s oven safe up to 500 degrees. Plus, the enamel is available in fun colors for a bright spot on the stove. Why not pink?

www.williams-sonoma.com

BLAINE FIGURE SKATER Liam Kapeikis was surrounded by figure skaters growing up. His parents had met performing in Disney on Ice, and his two older sisters loved the sport, too. But until he turned 7, there were no boys figure skating in his hometown of Wenatchee. It wasn’t until 2011, when another boy joined the sport, that Kapeikis laced up his skates and began figure skating in earnest.

With his parents coaching him, success came quickly, and soon Kapeikis was winning competitions. The typical time frame for going from single to double axel is five years, but Kapeikis had his single at age 11 and, twelve months later, had nailed the double axel. “As I grew older, I fell in love with figure skating and just knew it was what I wanted to do,” he said. “I realized I could go places and travel the world with my skating. Who wouldn’t want to do that?”

At 15, Kapeikis moved to Surrey, B.C., to be closer to the Connaught Skating Club at the Richmond Olympic Oval, where he could train in a more serious environment. “Back home there were only two of us who could do triples,” he explained. “In Richmond, there are fifteen of us just in my group who do triples, and being surrounded by that is so inspiring.”

but no off-ice training, and competitions were by video. Kapeikis’ motivation plummeted, and he placed ninth in the U.S. Nationals that year. “It was terrible,” he recalled. “But I figured I could either give up, or work twice as hard. I chose the second option.”

Born: Wenatchee

Lives: Blaine

Age: 21

“I train five hours a day, six days a week. I work on the ice close to four hours a day and spend the remaining hour alternating between pilates, ballet and weight training.”

“I follow a healthy diet that’s heavy in carbohydrates, because I need the energy, and in red meat, because I’m anemic and need to supplement my iron. I try to avoid junk food.”

“My older sisters, figure skaters, too, really inspired me to work hard at figure skating when I was a child. My sister Kaela, 28, performs in Disney on Ice, and she can really control an audience. I’d love to perform like she does.”

In 2019, he placed fifth in the U.S. novice championships, and in 2020, he placed third in the U.S. Junior Nationals. That year he relocated to Blaine, from which he commutes six days a week to the Oval to train in a facility that’s nothing short of exceptional, he said. “The skating level at the Connaught Club is very competitive, and being surrounded by that is so inspiring. The Oval contains all the resources I need under one roof, and I get to train with Wesley Chiu, the 2024 Canadian champion!”

The year 2020 was hard for athletes, and Kapeikis was no exception. Everything shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic, and he was off the ice for three months. After that limited ice time was permitted,

His hard work paid off in 2022, when Kapeikis had one of the best performances of his career. Competing against Olympians in the Nationals’ senior division, he placed seventh. In 2023, he competed in Skate Canada, the Grand Prix in the U.S. and the Four Continents Championships. In 2024, he was at the Grand Prix in Finland, too.

“I love performing, showing an audience what I can do,” he said. “My favorite time at the competitions is the thirty-minute practice sessions we get in the days leading up to the competitions. That’s where we get to skate with the best skaters in the world, and their power and speed is incredible. When I watch those exceptional skaters, it inspires me to skate even better.”

Figure skaters usually retire from the sport between the ages of 25 and 30, so Kapeikis still has time to complete his goals: to compete in a World Championship, and in the Olympics. “The 2026 Olympics is a possibility for me, but it’s unlikely. So I’ll probably stick around until the 2030 Olympics,” he said.

In the meantime, he coaches other skaters in Bellingham and is studying engineering at Simon Fraser University. “Skating will always be a part of my life, and I love it, but I’ll know when it’s time to move on,” he said.

“I’m grateful for everything it has given me—discipline, with respect to setting goals and working hard to achieve them,” he continued. “The skating world is like a family, and it’s great to have that sense of community and support. It’s been especially important in the wake of the American Airlines’ plane crash in January, which claimed fourteen members of the figure skating community. We’re coming together to help each other get through this.”

Elite ice skater Liam Kapeikis strives to reach Olympic goals written by Lauren

Kramer

The Modern Dane offers transparently produced sustainable bedding with the environment—and consumer—in mind

written by Rachel Gallaher

LIKE MANY people living in the Puget Sound region, Jacob Andsager moved to Washington for a job in the tech industry. Originally from a small town in southern Denmark, Andsager—who launched a natural bedding company called The Modern Dane in 2019—landed in the United States in 2002 to study information architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology and then earned an MBA in marketing, finance and managerial analytics from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

“I wanted to be the online editor of Newsweek magazine,” Andsager said, “but instead I spent a couple of decades working for a series of Fortune 500 companies, including Amazon for ten years.” He remembers a tour he took in one of the online retailer’s fulfillment centers, watching the workers packing up orders from thousands of customers.

“The operations were really impressive,” he said, “but I felt a little nauseated by the consumerism [on display] and started thinking about my own role in that cycle. Was I going to work every day to help crank out more stuff?”

After his wake-up call, Andsager tried transferring to several different roles within the company, hoping to find something that had a better social impact, but ultimately walked away to pursue a venture that felt more aligned with his core values.

“I wanted to build my own thing and do it the right way,” he said. “I wanted something that would have a positive impact on both consumers and the environment and connect back to my roots.”

After exploring several options, Andsager landed on bedding—a category where he saw significant room for improvement. Learning in his Danish heritage (the Danes are known for their design aesthetic and high-quality products that enhance daily life) and environmental concerns, he introduced The Modern Dane, a line of duvet covers, pillowcases and sheets crafted from organic European flax linen grown in France and Belgium. In addition to a rich selection of neutral colors, the linens come in nature-inspired patterns reflective of the Scandinavian outdoors.

“A lot of what I saw out there was uninteresting on the good side,” Andsager said, “and on the bad side, full of chemicals and pesticides and produced with child labor. I saw this as an opportunity to do something that tied back to my values. … I believe that good design can improve our lives.”

Each item from The Modern Dane is hand-sewn in Portugal, which is considered the hub of European textile craft. To meet rigorous environmental standards, Andsager is committed to using only materials with the following certifications: GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard), OEKO-TEX and European Flax. This means that every step of the production process is held to strict standards, ensuring environmental and human safety. Andsager also noted that growing linen is a carbon sink, reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. The cotton industry, on the other hand, pumps chemicals in the environment and produces hundreds of millions of tonnes of carbon annually.

The Modern Dane’s products are currently available directly to consumers via the company’s website, a model Andsager says helps reduce price points. It doesn’t mean that the bedding is cheap—a full/queen duvet cover starts at $328—but for those concerned about their environmental or dollar-spend impact, it’s a high-quality, durable and transparently produced choice.

Andsager understands his consumers are a niche group, and he plans to launch towels, pajamas, bathrobes and shower curtains, all the company’s trademark organic European linen, as a more attainable option. “We’re not trying make something for the sake of it being a high-cost luxury good,” Andsager said. “We’re trying to make things the right way. It’s something that you put against your skin—an investment in your nightly sleep.”

Bunny Dickson has built her entire career on creating community through food sourcing and culinary experiences. “I’ve worked on farms, brickand-mortar restaurants, food trucks, cruise ships,” she said. “I search for companies aligned in similar values which I hold true for myself community, quality, sustainability and leaving something be er for the next generations.” Today, she focuses her energies as a plant operations manager at Hama Hama Oyster Company in Lilliwaup.

Dickson started working in the food industry as a produce clerk in 2008 while living in San Francisco. She especially enjoyed working with local farms within a 90-mile radius of her home. “I learned about the hard work ethic of our local farmers and what it takes to get food from the soil to one’s table,” she said. “From humble beginnings as a produce clerk, I wanted to dig my hands into the soil and sand to truly understand what it takes to be a part of our food cycle.”

Dickson started her job as a farm intern at Hama Hama Oyster Co. working closely with fourth-generation oyster farmers in all kinds of inclement weather, such as rain, snow and sleet, as well as on warm, sunny coastal days. Working hard is part of her innate values. “We work hard, long hours, in all conditions, with a big, fat smile on our faces,” she said. “It’s not easy work, but it sure is rewarding being able to say that I can work a night tide, operate a crane and shuck oysters!”

Strong teamwork is found at the pinnacle of Hama Hama, and Dickson appreciates the company she shares with her co-workers. “There are so many moving parts, and I am honored to work with my partners at Hama,” she said. When Dickson is not at work, you can find her riding her mountain bike, cooking on the grill with friends and family or hanging with her two cats, Stormy Bear and Mojo.

Take a free guided tour of our historic Washougal Mill. Get a behind-the-scenes peek at our process, from dyeing the wool to the finishing touches. Sign up online at pendleton-usa.com.

FIND OUR STORES A SHORT DRIVE FROM ANYWHERE IN WASHINGTON. Located in Washougal, Seattle, Tulalip, Centralia, North Bend and Spokane See more locations at: PENDLETON-USA.COM

WOVEN IN T HE NO RT HWE ST SINCE 1863

ALL ACROSS WASHINGTON, but especially in counties like Whatcom, salmon and steelhead form part of the community. For this reason, the Bellingham-based Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association (NSEA) endeavors to connect local people with local fish and watersheds. The benefits of such collaborative and restorative work are clear as an ideal spawning stream.

Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association brings a sense of community to restoration

written by Daniel O’Neil

Founded in 1990, NSEA, a nonprofit organization, is one of fourteen regional fishery enhancement groups in Washington. By focusing its e orts on Nooksack River tributaries in eastern Whatcom County, and le ing the Lummi and Nooksack tribes take on the large-scale work in the mainstem river, NSEA restores and monitors the critical areas where salmon and steelhead spawn and rear.

Most salmon recovery entities rely on numerous engineers and project leads to get things done, but they don’t always involve the community. Besides executing its own projects removing fish passage barriers and planting native vegetation, NSEA brings people of all ages and backgrounds to restoration sites where they not only do important work but also take away a deepened sense of place.

“ at is such a key integral part of promoting and sustaining this work,” said NSEA executive director Annitra Peck. “We all have to be taking care of our watersheds. at means we all need a working understanding of how important watersheds are and what their functions are, and then where salmon play a role in that and where we can play a role to give back in that system.”

NSEA’s salmon recovery partners appreciate this communitywide resource. For instance, when an entity has a large restoration project to undertake but lacks the community outreach to bring in necessary volunteer help, NSEA will partner in order to provide its legion of helpers. In doing so, NSEA also helps amplify the message of the important work being done.

Over the past thirty-five years, NSEA has hosted more than 1,300 volunteer work parties. From planting native trees and

plants in salmon habitat, to counting fish, NSEA teaches people how to help. Education events further develop understanding and spread the word. NSEA also heads to fourth-grade classrooms across Whatcom County and at the Lummi Nation School. is school program engages kids in the workings of fish, habitat and restoration, both in the classroom and in the field.

“We’re always finding new ways to do things and new ways to engage people, furthering the work and promoting more energy towards this sector,” Peck said. “We definitely need more young people interested in science and attending to climate change issues, and carrying on all the good work that’s been done.”

For John ompson, senior salmon recovery planner for Whatcom County, NSEA’s participation on all levels of salmon and steelhead restoration is indispensable. “NSEA brings a unique mix of community connections to landowners and agencies, a dedicated staff that takes action daily restoring habitat, and a supportive and innovative board of directors,” he said. “ ey are a leader among the regional fisheries enhancement groups that work across the state.”

e bulk of NSEA’s funding comes from government grants, a newly endangered species. With no funding available for projects in 2025, NSEA instead turned to community members for donations and volunteer hours to revisit 157 restoration

“legacy” sites that they hadn’t seen in more than twenty years. Relationships with landowners have been renewed, sites have been evaluated and even improved, and the connection between community and salmon country has expanded.

“We were operating out of a closet at one time, and now we have our own campus,” Peck said. “ is is different than any we’ve experienced, but we do have the resiliency that we’ve built through other challenges to help us navigate through this.”

NSEA doesn’t just help and teach about some of nature’s most perseverant species, salmon and steelhead. It has learned from those fish, too.

The artful allure of the San Juan Islands

written by Ryn Pfeuffer

The San Juan Islands have always had a creative pull—long before art studios dotted Friday Harbor or Lopez Village. Coast Salish peoples shaped this legacy through carving, weaving and storytelling rooted in place. Today, their in uence endures in striking public art, from Musqueam artist Susan Point’s Interaction house posts to contemporary works by Lummi Nation artists like Jewell James and Dan Friday.

Throughout the islands, creativity feels rooted and personal, whether it’s a painter interpreting the shi ing light on a dri wood-strewn beach or a glassblower capturing the movement of orcas in molten color. You’ll nd artist co-ops in historic buildings, galleries tucked into back gardens and studios that welcome curious visitors. And with annual events like the San Juan Island Studio Tour and the Friday Harbor Film Festival, there’s always a new story being told.

This is a place where art isn’t just decoration—it’s a means by which people connect to the natural world, to one another and the past. The San Juans don’t just attract artists—they shape them.

Whether you’re coming for the orcas or the oysters, San Juan Island has a nature-woven arts scene that’s as much a part of the landscape as the madrona trees and the sparkling Salish Sea. Step off the ferry into Friday Harbor, and you’re instantly immersed. is laid-back port town is the island’s cultural hub, where galleries, studios and public art are all easily explored on foot.

Begin at WaterWorks Gallery, a local institution since 1985 that leans into contemporary fine art and studio jewelry, often inspired by the Pacific Northwest’s light, water and line. Just around the corner, Arctic Raven Gallery provides a respectful and powerful showcase of Northwest Coast Indigenous art, featuring carved masks, silver bracelets etched with salmon and orca motifs and prints and sculptures by Coast Salish, Haida, Lummi and Tlingit artists. Here, you’re not just seeing art—you’re stepping into deep, place-rooted storytelling.

Plan your visit for a Saturday, if you can, when the Farmers Market brings out painters, potters and fiber artists alongside fresh-baked pies and live music. e town’s summer gallery walks also add a festive spin to the scene—follow the laughter and the lavender lemonade. Local gems, such as Luminous Gallery and Friday Harbor Atelier, welcome drop-ins and often host artist talks and demonstrations. Keep an eye out for public installations, too, like the monumental cedar house posts at Fairweather Park. Carved by Musqueam artist Susan Point, Interaction depicts the interconnection of humans and animals, standing as the island’s first formal acknowledgment of its tribal heritage.

To go deeper into the creative process, head just outside town to

Alchemy Art Center, where community ceramics, printmaking and artist residencies collide in the best way. eir seasonal “Art in the Park” popups bring tile murals and hands-on workshops to outdoor spaces, while June’s San Juan Island Artists’ Studio

“Whether

you’re coming for the orcas or the oysters, San Juan Island has a nature-woven arts scene that’s as much a part of the landscape as the madrona trees and the sparkling Salish Sea.”

Tour lets you step directly into more than twenty working studios. From sculptors and ceramicists to weavers and woodworkers, this is your chance to chat, watch and maybe even come home with something one-of-a-kind (and still warm from the kiln).

Once you’ve explored Friday Harbor’s artistic core, hop in the car and head north toward Roche Harbor for a change of pace. Here, the San Juan Islands Sculpture Park sprawls across 20 pastoral acres, where more than 150 sculptures peek out from meadows, woods and waterfront trails. You’re encouraged to wander, touch and even picnic among kinetic works, bronze wildlife and whimsical abstractions. Come spring, the iconic Daffodil Frolic event dazzles with more than 9,000 blooms in April and May, and summer brings the Summer Art Series—Sunday workshops where families can create site-specific pieces that blend into the parkscape.

Along the way, consider calling ahead to visit some of the island’s working artists. Ceramicist Paula West creates earthy, soda-fired pottery from a tucked-away studio. You’ll also find Doug Bison’s bronze sculpture K-5, honoring the killer whale “Sealth,” standing watch at the Ralph Munro Whale Watch Park, a tribute that blends his Lakota heritage with local marine lore.

And don’t count the island out in fall. October brings Artstock, a weekend art celebration with gallery openings and artist receptions. Later that month, the Friday Harbor Film Festival draws cinephiles and creatives from all over with a lineup of documentary films focused on conservation, exploration and stories that matter. Panels, pop-up art shows and filmmaker meet-and-greets round out the experience, making it clear: On San Juan Island, creativity doesn’t take a season off.

Don’t let Lopez Island’s slow vibe fool you. is place is brimming with local artistry, much of it quietly woven into village life and weekend rituals. With a car (or bike), you can uncover a charmingly unpolished, hyperlocal arts scene that feels more like being let in on a secret than walking into a gallery. Start your exploration in Lopez Village, the island’s tiny but mighty heart. Right behind Lopez Bookshop and Fine Mess Bakery, you’ll find Chimera Gallery, a long-running artist cooperative that showcases

work from painters, ceramicists, fiber artists and jewelers who call Lopez home. Everything here is made on the island, and you’ll often find the artists themselves tending shop and happy to chat. Just a short stroll away, Skarpari (Icelandic for “cutler”) offers a stunning mix of handcrafted knives, jewelry and metalwork in a rusticchic workshop setting. Come for the art, stay for a cup of their organic roasted coffee.

If you’re lucky enough to be visiting in early June, the Lopez Island Artist Guild & Studio Tour is a don’t-miss. Dozens of artists across the island open their studios for demonstrations and open house-style visits. It’s the

kind of event where you might end up sipping lemonade with a potter who just pulled a platter from the kiln or chatting beadwork techniques with a Coast Salish-inspired jewelry maker. Come summer weekends (through September 20), the creative energy spills into the Lopez Island Farmers Market, where painters, potters and jewelers set up under pop-up tents steps from stacks of fresh bread and goat cheese. ese stalls often rotate, so each visit brings something new— small-batch ceramics, nature-printed textiles and other island-crafted keepsakes that feel as rooted to the Salish Sea as the driftwood-strewn beaches just down the road.

Shaw Island may be the quietest of the ferry-served San Juans, but for those drawn to solitude and subtle beauty, it’s a well-kept secret. With no galleries or bustling art walks, its creative energy flows from mossy forests, ebbing tides and a stillness that invites reflection. e Little Red Schoolhouse & Historical Museum, open by appointment, shares a charming peek into island life. ink handmade quilts, faded photographs and island-crafted keepsakes. Shaw’s not about a formal arts scene; it’s about inspiration in its rawest form. Bring a journal, a camera or just your curiosity, and let the island reboot your creative drive.

“Shaw Island may be the quietest of the ferry-served San Juans, but for those drawn to solitude and subtle beauty, it’s a well-kept secret.”

“With its misty forests and winding mountain roads, Orcas Island practically begs to be painted, carved or sculpted. Fortunately, its artists have answered the call.”

With its misty forests and winding mountain roads, Orcas Island practically begs to be painted, carved or sculpted. Fortunately, its artists have answered the call. As you roll off the ferry at Orcas Landing, you’re already on the trail of island-made ceramics, paintings and kinetic sculptures tucked into every nook and neighborhood.

Your first stop is Eastsound, the island’s walkable hub and home to a thriving arts scene. Pop into Crow Valley Gallery for carved kitchen tools, wheel-thrown pottery and island prints. Just up the street, the Wandering Soul Art Gallery is worth the detour, with woodwork and mixed-media pieces displayed in a space that feels more like a garden hideaway than a gallery.