DEVELOPING A GROWTH STRATEGY FOR SITUATIONAL

BY DAVID W. NORTON

EXPLORING THE STRATEGY LIFECYCLE MAGAZINE 2024 | ISSUE 39

32 ILLUSTRATING “WHAT IS A SOUND STRATEGY SYSTEM?” 28 ENHANCING SWOT ANALYSIS FOR AN ACTIONABLE PLAN 12 GETTING “STRATEGY” INTO YOUR “STRATEGY FRAMEWORK” DOWNLOAD OR PRINT THIS MAGAZINE

Be a part of the Global Home for Strategy Professionals.

Become a Member, Today!

Gain a competitve advantage from exposure to the best thinking and guidance in formulating and executing winning strategies.

IASP is a non-profit professional society whose mission is to lead and support people and organizations through the promotion of a holistic approach to strategy management and by setting standards for strategy through thought leadership, professional development and certification.

Being a member of IASP Means –

• Opportunities to meet and learn from international strategy experts and network with peers across the globe

• Volunteer and collaboration opportunities with chapter and global committees and communities of practice

• Exclusive, member-only discounts on global conference, webinars, and educational opportunities

Membership levels range from individual to corporate group options. Visit www.strategyassociation.org and JOIN TODAY!

Strategy Magazine is a publication

the International

for

It is brought to you in collaboration with Craig Kelman & Associates Ltd. 3rd Floor – 2020 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, MB R3J 0K4 Tel: 866-985-9780 Fax: 866-985-9799 www.kelmanonline.com CONTENTS FEATURES EDITORIAL International Association for Strategy Professionals (IASP)

Editor’s Column Pierre Hadaya 4 President’s Message Monica Allen 6 USING EVALUATIVE THINKING TO ACHIEVE BETTER RESULTS Lewis Atkinson and Barbara A. Collins 8 GETTING “STRATEGY” INTO YOUR “STRATEGY FRAMEWORK”

Compo 12 EMOTIONS AND PURPOSE: HOW TO CREATE A STRATEGIC PLAN THAT PEOPLE REALLY CARE ABOUT Tim Kelley 18 DEVELOPING A GROWTH STRATEGY FOR SITUATIONAL MARKETS David W. Norton 24 FROM INSIGHT TO ACTION: ENHANCING SWOT ANALYSIS FOR AN ACTIONABLE PLAN Christian Rusteberg 28 ILLUSTRATING WHAT IS A SOUND STRATEGY SYSTEM? A SYSTEMS THINKING PERSPECTIVE Pierre Hadaya and L. Martin Cloutier 32 Advertiser Product & Service Centre 35 THE MISSION OF STRATEGY MAGAZINE IS TO PUBLISH THEORY-BASED PRACTICAL ARTICLES TO HELP EXECUTIVES, STRATEGISTS, MANAGERS, AND OTHER PROFESSIONALS BETTER FORMULATE, IMPLEMENT, EXECUTE, ENGAGE, AND GOVERN STRATEGIES. ISSN 2995-1291 © International Association for Strategy Professionals, 2024. All rights reserved. SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39

of

Association

Strategy Professionals (www.strategyassociation.org).

37637 Five Mile Road, #399 Livonia, MI 48154 | United States E: info@strategymagazine.org W: www.strategymagazine.org

Peter

IPIERRE HADAYA, EDITOR, STRATEGY MAGAZINE

IPIERRE HADAYA, EDITOR, STRATEGY MAGAZINE

The Metaphor of the Perfect Free-Standing Handstand

recently read Invent and Wander: The Collected Writings of Jeff Bezos, with an Introduction by Walter Isaacson

There is a great passage in Amazon’s 2017 shareholder annual letter that I would like to share with the readers of Strategy Magazine. In this part of the annual letter, Bezos emphasizes the following two things required to achieve high standards in a particular domain:

1) Recognizing what good looks like in one domain, and 2) Having realistic expectations for how hard it should be (how much work it will take) to achieve that result – the scope. To make this point clearly, he first uses the metaphor of the perfect free-standing handstand which goes like this:

“A close friend recently decided to learn to do a perfect free-standing handstand. No leaning against a wall. Not for just a few seconds. Instagram good. She decided to start her journey by taking a handstand workshop at her yoga studio. She then practiced for a while but wasn’t getting the results she wanted. So, she hired a handstand coach. Yes, I know what you’re thinking, but evidently this is an actual thing that exists. In the very first lesson, the coach gave her some wonderful advice. “Most people,” he said, “think that if they work hard, they should be able to master a handstand in about two weeks. The reality is that it takes about six months of daily practice. If you think you should be able to do it in two weeks, you’re just going to end up quitting.” Unrealistic beliefs on scope – often hidden and undiscussed – kill high standards. To achieve high standards yourself or as part of a team, you need to form and

proactively communicate realistic beliefs about how hard something is going to be – something this coach understood well.”

After putting forth this metaphor, Bezos uses the example of writing Amazon’s natively structured six-page memos. These memos, introduced by Bezos in 2004, have become the standard for communicating effectively at Amazon, whether to present ideas or conduct meetings. Bezos writes…

“In the handstand example, it’s pretty straightforward to recognize high standards. It wouldn’t be difficult to lay out in detail the requirements of a well-executed handstand, and then you’re either doing it or you’re not. The writing example is very different. The difference between a great memo and an average memo is much squishier. It would be extremely hard to write down the detailed requirements that make up a great memo, I find that much of the time, readers react to great memos very similarly. They know it when they see it. The standard is there, and it is real, even if it’s not easily describable.

Here’s what we’ve figured out. Often, when a memo isn’t great, it’s not the writer’s inability to recognize the high standard, but instead a wrong expectation on scope: they mistakenly believe a high-standard, six-page memo can be written in one or two days or even a few hours, when really it takes a week or more! They’re trying to do the perfect handstand in just two weeks, and we’re not coaching them right.

The great memos are written and re-written, …, set aside for a couple

of days, and then edited again with a fresh mind. They simply can’t be done in a day or two. The key point here is that you can improve results through the simple act of teaching scope –that a great memo should probably take a week or two.”

When I read this passage, it immediately made me think of how we tend to underestimate all that is required to write a great Strategy Magazine article. Indeed, the requirements that make up a great article are not easy to write down. A great theory-based practical article in strategy will not only vary from one subject to the next but also according to the theory or theoretical concepts upon which the article is anchored. Furthermore, writing a Strategy Magazine article is more than having an idea and swiftly putting it on paper/computer. In addition to taking creativity and strong writing skills, creating a well-structured and tightly knit piece with great content and insight in less than 2,000 words, which strategy practitioners can easily read, reflect on, and put into action, takes much more discipline, time, and patience than we initially estimate.

To support authors in this endeavor, I’ve implemented an effective and efficient collaborative process with authors that maximizes the quality and impact of our articles with the least amount of time and effort as possible (to write a great piece). This process encompasses four major steps: (1) Identifying a sound or promising idea, along with the theoretical concepts to anchor it, as well as determining the “practical” objective and contribution of the article; (2) Structuring the paper and its sections to ensure flow; (3) Writing the paragraphs; and (4) Adjusting, improving and finalizing the paper. And I’m happy to say that executing this process in

Editor’s Column

4 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE RETURN TO CONTENTS

collaboration with great authors has led to the publication of six excellent articles in the current issue that should propel Strategy Magazine toward becoming the standard for theory-based practical research in strategy management.

In the first article, Using Evaluative Thinking to Achieve Better Results, Lewis Atkinson and Barbara A. Collins propose a novel method of inquiry based on evaluative thinking that can aid leaders in explaining how and why a particular combination of strategic actions are working in the way that they intended.

In the second article, Getting “Strategy” into Your “Strategy Framework,” Peter Compo clarifies the difference between a strategy and a strategy framework and introduces the strategybottleneckaspiration triad, the design of which is a valuable first step for incorporating a strategy into a strategy framework.

In the third article, Emotions and Purpose: How to Create a Strategic Plan that People Really Care About, Tim Kelley proposes an emotionally-based,

purpose-driven method to create strategic plans that maximize motivation.

In the fourth article, Developing a Growth Strategy for Situational Markets, David W. Norton explains the concept of a situational market, distinct from the traditional concept of a market, and proposes an approach for sizing situational markets. This approach enables companies to build new market strategies that create far more revenue.

In the fifth article, From Insight to Action: Enhancing SWOT Analysis for an Actionable Plan, Christian Rusteberg describes SWOT and its limitations, and introduces a new method that addresses the traditional framework’s shortcomings so it can reach its full potential.

The last article is the result of popular demand. Indeed, these last few years, I’ve been asked by several readers and colleagues for more details as to what a sound strategy management system actually is. To answer this important question, I’ve teamed up with my friend, colleague and expert in business dynamics, Martin Cloutier.

Our explanation is summarized in our article Illustrating What is a Sound Strategy System? A Systems Thinking Perspective. To conclude, I would like to thank all those who have contributed to the publication of this issue, especially my associate editor, Tamara Highsmith, and Katie Woychyshyn from Craig Kelman & Associates, without whom bringing this issue to publication would not have been possible. Together, we hope that you’ll enjoy this issue as much as we enjoyed preparing it.

If you have any comments or suggestions on this or upcoming issues or would like to volunteer to help Strategy Magazine in implementing and executing its mission, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

PIERRE HADAYA , PHD, ASC Editor, Strategy Magazine pierre.hadaya@strategymagazine.org

PIERRE HADAYA , PHD, ASC Editor, Strategy Magazine pierre.hadaya@strategymagazine.org

EXPLORING THE STRATEGY LIFECYCLE

Call for Ideas

The mission of Strategy Magazine is to publish theory-based practical articles to help executives, strategists, managers, and other professionals better formulate, implement, execute, engage, and govern strategies. The magazine is dedicated to helping executives, strategists, managers, and other professionals make their strategy work. Topics relevant for our readership include, but are not limited to:

• Novel and proven ideas and practices (e.g. methods, techniques and tools) to support the formulation, implementation, execution, engagement and governance of sound strategies.

• Thought provoking case studies and summary survey findings in the field of strategy.

If you are interested in joining the leading practitioners and researchers that provide quality articles that will shape the future of the field of strategy, please complete the idea form on our website (www.strategymagazine.org) and send it to us by email at pierre.hadaya@strategymagazine.org.

Best wishes,

PIERRE HADAYA , PHD, ASC Editor, Strategy Magazine

PIERRE HADAYA , PHD, ASC Editor, Strategy Magazine

MAGAZINE

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 5 RETURN TO CONTENTS

AMONICA ALLEN, IASP PRESIDENT

AMONICA ALLEN, IASP PRESIDENT

Reestablishing Our Strategic Direction

s I think about our work at the International Association for Strategy Professionals (IASP), I want to thank each of you for reading this message. You are volunteers, contributors, supporters, cheerleaders, and believers in the work of IASP. And for that, I am grateful as your President. You each have made this association amazing.

As we look to the future of IASP, I am excited and energized by some of the recent work we have done. When I became President in the summer of 2023, one of the first tasks I needed to focus on was to rally the Board to work on the 2024-2026 strategic plan for IASP. I am happy to say that we completed and approved our new strategic plan and are in the implementation process.

A little about the development of this plan…

During the 2023 summer Board retreat, it became apparent to many of us that we should embrace parts of the 2020-2022 strategic plan, focus on the future, and identify new and fresh ways to complement the last strategic plan. As such, we landed on three priority areas that shape and frame our work. Those areas are:

1. Membership: IASP attracts and retains members globally and cultivates an environment where members serve as ambassadors for IASP

2. Connections: IASP offers highquality content and networks that connect and engage IASP and its stakeholders

3. Organizational Sustainability: IASP has effective management and adequate resources (financial and HR) to achieve its mission and strategic goals

With membership, we want to grow and retain members globally while leveraging the work identified in the connections priority area. That work will consist of having a better focus on the Communities of Practice (CoPs), which, for our new members, are spaces for likeminded or like-sector persons to come together in various ways such as webinars, table talks, general conversation, or other fun things to share and do. We also want to continue supporting the chapters across the globe and expand the number of chapters into places we are not currently in but may have members who are in those places. Also, another key thing for us is to think of ways to build new relationships and partnerships with colleges and

In addition to completing a strategic plan, we also have other accomplishments:

• Started new chapters in the UK, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia – thus expanding our global reach.

• Re-engaged potential partners of the association.

• Completed the 2024 Member Survey in January. Thank you to those who responded. We received a great amount of feedback from you and will share results with the full membership once all the data is analyzed.

• Certified 79 individuals since July 1, 2023 as either Strategic Management Professional (SMP) or Strategic Planning Professional (SPP).

“ AS WE LOOK TO THE FUTURE OF IASP, I AM EXCITED AND ENERGIZED BY SOME OF THE RECENT WORK WE HAVE DONE.

universities, develop and implement a content management strategy, and enhance and expand our global webinar offerings. Lastly, what we do in the membership and connection arena leads us to organizational sustainability, which includes working with current and new partners, evaluating and identifying methods to increase revenue and/or decrease costs from existing knowledge assets, and reviewing our HR and governance models and frameworks.

By focusing on those three priority areas, our association will be stronger. Having seen significant increases in membership growth numbers in recent months, we want to be positioned to meet member needs as well as clarify who we are, what we do, and why we do it.

While the first year of my presidency has focused on reestablishing our strategic direction and being intentional about what we need to focus on, please know that IASP is doing well and has a lot of great volunteers and partners behind the association.

I look forward to seeing you and meeting you in Calgary in June! Our planning team has worked tirelessly to prepare and deliver a wonderful conference.

I want to thank the IASP Board of Directors, including Pierre Hadaya, PhD, ASC, the Editor of this publication.

All the best,

MONICA R. ALLEN, PHD 2023-2025 IASP President

President’s Message

6 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE RETURN TO CONTENTS

• June 6 & 7 at the two-day exam prep workshop “The Systems Thinking Approach® to Strategic Management” lead by Valerie MacLeod, MBA, SMP, IASP Pioneer and Global Partner at The Haines Centre for Strategic Management; and Dr. Lewis Atkinson, Global Partner at The Haines Centre for Strategic Management. Join this global team to learn a Systems Thinking approach to strategic planning and execution.

• At our dynamic booth in the Exhibitor Hall for additional learning opportunities.

• Go to www.systemsthinkingpress.com for cutting edge resources based on the systems thinking approach®

To register for the original IASP certification preparation workshop: www.valeriemacleod.com/sta-to-sm-iasp-exam-prep-2024-conference Use code IASPHAINESCENTRE at checkout for 10% discount.

BY LEWIS ATKINSON AND

All strategy is a hypothesis and its implementation is an experiment in execution (Atkinson and Collins, 2023). Strategic actions selected for implementation are those with the greatest likelihood of moving the organization closer to achieving its vision, mission, and values. Unfortunately, when making decisions about strategy, most leaders rely too heavily on intuition and their causal reasoning may be flawed (Lovallo and Kahneman, 2003). The objective of this article is to propose a novel method of inquiry based on evaluative thinking that can aid leaders in explaining how and why a particular combination of strategic actions are working in the way that they intended. The proposed method can also help them gradually improve the quality of evidence supporting their causal claims (e.g., increasing advertising increases sales).

USING EVALUATIVE THINKING TO ACHIEVE BETTER RESULTS

This sort of thinking is also known as causal inference. The desired results or ends are what we aim to achieve, and the means are the way in which we choose to achieve them. Put differently, strategic action A causes result B, mediated by conditions C and D.

EVALUATIVE THINKING: WHAT WORKS, FOR WHOM AND UNDER WHICH CONDITIONS

The strategic question we are concerned with is: What is the causal effect of a strategic action

To understand causality, strategy professionals and their leaders must adopt a disciplined approach to testing and adapting each strategic action as a theory, rather than a fact. The evaluation should consider how things will change (i.e., hypothesised causal mechanism), including forensic analysis of assumptions about the conditions necessary for the intended result to be achieved. This discipline, called evaluative thinking, necessitates “thinking about your thinking” – the way one reasons, plans, and acts. It involves examining potential flaws in one’s own causal reasoning, motivation, biases and wishes, and learning from failures as well as successes.

observed result a direct consequence of the action. There are conditions such as capabilities and resources and causal mechanisms, or a combination of underlying enabling tactics and business models, processes, or structures, that also impact observed results. Therefore, the cause must be inferred from observed evidence and causal reasoning. Evaluative thinking begins with a clear articulation of the evidence that would indicate the emergence of the desired outcomes from the selected means.

In practice, confidence in causal claims increases by stepping up the rungs of a “hierarchy of causation” (Pearl, 2000) as shown in Table 1.

METHOD FOR USING EVALUATIVE THINKING TO ACHIEVE BETTER RESULTS

A strategic management system (SMS) is a comprehensive “system” that allows leaders to “transform the organization in an effective, efficient

DOWNLOAD OR PRINT THIS ARTICLE 8 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE RETURN TO CONTENTS

LEVEL OF CAUSAL HIERARCHY REAL-WORLD EXAMPLES OF INCREASING LEVELS OF CAUSAL UNDERSTANDING

1. Association (Seeing: what is?)

2. Intervention (Doing: what if?)

(Understanding: why?)

“Every day in the US, thousands of kids still pick up a tobacco product for the first time” (Anonymous II). This observation does not tell us anything about the cause of what we observe; no causal understanding.

Causes that are hypothesized to influence teen smoking include parents who smoke, peer pressure, smoking as a form of rebellion, seeking altered states, clever marketing, etc. These are simply ideas about possible causes of what we observe, without evidence to support any of these hypotheses (alternate causal explanations).

Through A/B testing on matched samples, it was determined that parents who smoke are more influential on teen smoking behaviour than clever advertising alone. Testing and validation help increase our understanding of cause, which strategic action has greater effect, under what mediating conditions and why (evidence confirms causal mechanisms that describe how it is that the strategic action contributes to observed results).

THREE LEVELS OF INCREASING CAUSAL UNDERSTANDING (1 LOW TO 3 HIGH)

and agile manner” (Hadaya, Stockmal , 2023). This transformation results from achieving three goals underpinned by three universal premises (see Table 2) which guide the enterprise-wide implementation of the SMS (Haines and McCoy, 1995).

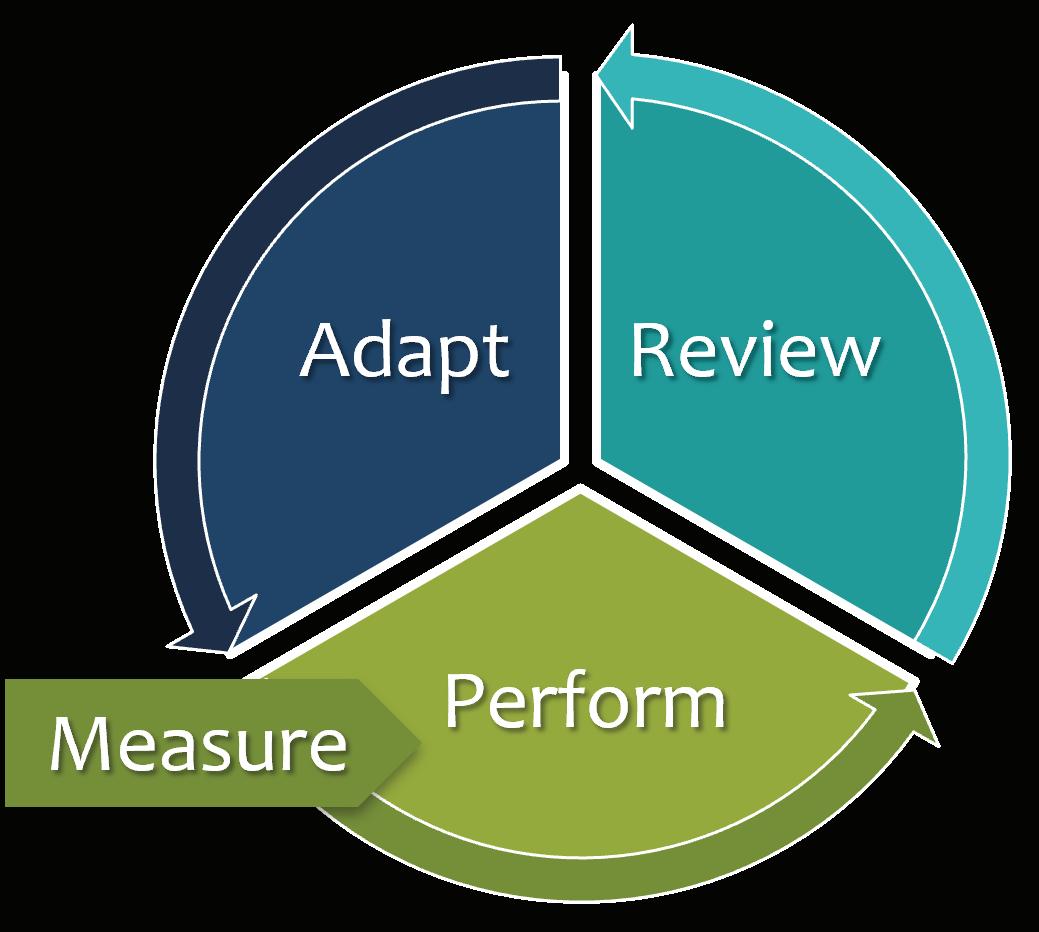

The five-phase method proposed ties the activities of strategy formulation implementation, and execution together in an iterative cycle of continuous improvement, even though presented linearly. The following paragraphs describe each phase for which the objective, a description, techniques, and linkage to the relevant SMS goal or premise are presented.

Phase 1: Achieve a Shared Understanding of Vision, Goals, and Strategy Mechanisms

The objective of this phase is to create a shared understanding of the organization or program vision, goals, and causal mechanisms. The most effective way to do this is through a technique called Parallel Stakeholder Engagement, whereby those implementing the strategy are involved in its formulation. This early and frequent involvement enhances engagement with underlying logic and hypothesised causal mechanisms and assumptions, thereby creating a sense of ownership necessary for successful execution; a key premise of the SMS (see Table 2).

Phase 2: Quantify Shared Understanding by Identifying Evidence of Achievement

The objective of this phase is to identify clear and measurable results (the ends) for the organization or program. This involves translating detailed definitions of the shared vision, mission, and values into tangible evidence of achievement that is clearly understood by both the Board and executives. Two techniques help participating stakeholders focus and agree on customer-centric measures of success: the mission triangle and the customer value-added star. The mission triangle technique asks three clarifying questions in sequence: Who is the customer we serve? What needs do they have that we want to fulfill? What do we do to meet those needs? The customer value added star technique is then used to rank relative competitive positioning of what the organization does for the customer across five criteria: cost, responsiveness, choice, service, and quality. Quantification of these ends can only come after SMS Goal #1 has been achieved. Only then can the means of achieving these ends be formulated.

Phase 3: Select Strategic Actions That Have the Greatest Likelihood of Achieving Results/Ends

This is where the formulation of the means to achieve desired ends begins. The objective of this phase is to select

GOAL/PREMISE WHY IT WORKS AS PART OF A STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

Goal #1 Achieve clarity of purpose and direction

Goal #2 Ensure successful transformation

Goal #3 Sustain high performance over the long term

Premise #1 Planning and change are the primary job of leadership

Premise #2 People support what they help create

Premise #3 Systems thinking – focus on outcomes – that serve the customer

TABLE 2: THREE GOALS AND THREE PREMISES OF STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT

and prioritise strategic actions to transform the operating model by building on strengths and leveraging partnerships to fill capability gaps. Strategists can use a technique called current state assessment here, which includes internal and external analyses to determine what is working now and the best alternative use of resources in the form of new strategic actions. This phase contributes to the achievement of SMS Goal #2 because it prioritises strategic actions, which transform the existing operating model and realign it to the new strategy.

Phase 4: Map Strategic Actions to the Relevant Results/Ends in a Matrix of Causal Relationships

The objective of this phase is to be very explicit about the hypothesised, causal relationships that connect actions to results. These connections, devised in Phase 3, are tested/validated by the Board and executives in Phase 5. This phase maps the action/result connection to show the extent (i.e., casual strength and over what timeframe [short-term vs. long-term]) each strategic action is expected to contribute to a change in each result. A simple matrix can be used to map actions (means) to results (ends) (Figure 1). This work allows the achievement of SMS Goal #3 because it provides a test bed for the experiment of execution.

Phase 5: Test and Resolve the Validity of Hypothesised Causal Relationships in the Matrix

The objective of this phase is to not only test and validate but to also refine the story of how each strategic action actually caused an observed change in result(s), whereby successive trial and error ensures that the best possible combination of interrelated strategic actions (means) evolves over

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 9 RETURN TO CONTENTS

time to best serve changing customer needs, translating to better results (ends). For each cell mapped in the matrix, stakeholder insights are used to validate and resolve possible causal mechanisms and the contribution of the strategic action to the observed changes in results. During this phase, the Board and executives are asked: “In light of the multiple factors influencing a result, has this strategic action made a noticeable contribution to an observed result and in what way?” The technique used to develop the story is called contribution analysis (Mayne, 2001). The purpose of this technique is to prove or disprove causality, or imagining and eliminating alternative explanations. It uncovers conditions, causal mechanisms, and/or associated feedback loops (both positive and/or negative reinforcing) between strategic actions in the matrix. Another useful technique is sensitivity analyses, which involves analyses of how sensitive the results are to variations in the levels of assumptions about prevailing mediating conditions (e,g., low, medium, or high). The sensitivity can be modelled for each causal claim to estimate the extent the observed results would change at each level, or if at all. The work done in this phase is guided by the SMS Premise #1, which entails building an internal management capability to support successful execution (buy-in) and ownership (stay-in) for implementation.

To demonstrate how this method can be applied, the example of a causal claim that “more beef industry advertising increases demand for beef in Australia” (see Anonymous III for more case study details). To this end, Aggressive promotion of Beef in the Australian market was a strategic action chosen by Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA). It invested approximately $29.5 million in beef industry promotional campaigns in Australia between 2004-2005 and 2009-2010. The intent was to increase the value of beef sales in the Australian market by $300 million each year, over six years. The example is an important demonstration of the application of evaluative thinking:

Phase 1 confirmed a shared vison and common goal of increasing value of beef sales. The MLA Board and cattle industry levy-payer representatives

THE CROSS-TAB RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROGRAMS AND POPULATION RESULTS

Program 1

e.g. Job Training Program 2

e.g. Trash Recycling

Program 3

e.g. Child Care Program 4

e.g.

Program 5

e.g.

Program 6

e.g.

Program etc.

e.g.

FIGURE 1: GENERIC MEANS/ENDS MATRIX

discussed ways to achieve this. Based on their shared understanding they proposed the following hypothesis; “increasing beef industry advertising by $4.9 million per year increases value of beef sales by $300 million per year.”

Phase 2 sought to identify a clear and measurable increase in beef sales value arising from this $4.9 million per year advertising strategy. The MLA Board and executives decided to track the monthly change in the dollar-value of beef expenditure per buyer as a consequence of advertising. The monthly promotional campaign schedule during 2005-2010 was compared to a time-series of AC Neilsen Homescan beef expenditure data over the same period in 2004-2005 and 2009-2010.

Phase 3 considered the likelihood of the advertising strategy actually increasing beef sales value.

The observed changes in monthly expenditure per buyer provided no evidence of any increase in the value of beef sales in the period after any of the scheduled dates for promotional campaigns, nor was there any evidence of a sustained long-term trend of increasing value of sales. This concerning result was confirmed by traders actually selling beef in the market (meat packing companies, supermarkets and retail butchers). The finding was further reinforced by evidence provided by traders that the $29.5 million spend by

MLA was quite small relative to their own advertising spent over the same period. Yet, they did believe that beef industry advertising was complementary, albeit in a relatively small way, to their own private company marketing strategies. So, the MLA Board and cattle levy-payer representatives funding the strategy, agreed with marketing executives to re-configure the beef industry advertising strategy. It built on the strengths of the existing strategy and leveraged partnerships with traders in order to get better results from future beef industry advertising.

Phase 4 mapping advertising strategy to relevant results. The analysis in Phase 3 identified two new strategic mechanisms thought to be at work at an all-of-marketsystem level: consumer awareness and channel engagement (Figure 2). The plausible alternative hypothesis to be tested was that the consumer campaigns (Figure 2, yellow section) could be re-configured to support the entire beef category by helping to maintain awareness of the positive attributes of beef among consumers. This heightened awareness of positive attributes could then be leveraged by traders advertising private-brands to increase the value of their own beef sales. It was also posited that complimentary channel engagement activities (Figure 2, grey section) could maintain market penetration/share for

Prosperous

Safe Communities Result

Strong Families

etc.

Result 1

Economy Result 2 Clean Environment Result 3

4

Result 5

Result 6 etc.

DIRECT SHORT-TERM INDIRECT SHORT-TERM DIRECT LONG-TERM INDIRECT LONG-TERM

10 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE RETURN TO CONTENTS

the traders’ private brands by increasing the amount retail shelf space for beef and thus increasing the opportunity for consumers to choose beef for purchase. Phase 5 testing and resolving the validity of plausible causal relationships. New insights generated in Phase 4 enabled MLA Board and cattle levy-payer representatives funding the strategy to develop a new result for future beef industry advertising; “counter pressures (economic, health, environmental) to reduce red meat consumption by contributing to maintaining consumer expenditure on beef at $6.6 Billion.” The MLA marketing executives then worked to refine the story of how the hypothesised effect of the interaction between these two new strategic mechanisms combined to achieve this new all-of-market-system level result. Ongoing review and adjustment to beef industry advertising strategy now occurs in partnership with traders so that the best possible combination of interrelated strategic actions evolves over time contributing to achieving this all-ofmarket-system result.

CONCLUSION

This paper proposes a novel method of inquiry based on evaluative thinking. Evaluative thinking is a key part of

systemic management of strategy and crucial to more accurately defining strategies and removing human biases. Strategists wanting to include this method as part of their practice should not be discouraged by initial resistance from their Board and executives. Human nature, optimism, and confirmation seeking biases and in some cultures a tendency towards “saving face” means that leaders will rarely be inclined to invest in seeking reasons for why their chosen strategic action is not working as intended. However, careful facilitation of leaders and their Boards to help them “think about their thinking” and the way(s) they reason, plan, and act will enable organisations to benefit from better learning from failures as well as successes.

REFERENCES

Anonymous I (2023) Evaluative Thinking. Better Evaluation. www.betterevaluation.org

Anonymous II (2023) Smoking Facts American Lung Association. www.lung.org/quit-smoking/ smoking-facts

Anonymous III (2023) Aggressive Promotion in the Domestic Market (Beef). Meat & Livestock Australia.

ABOVE-THE-LINE ADVERTISING EARNED MEDIA

Atkinson, L., and Collins, B. (2023) Is This Strategy Working?: The Essential Guide to Strategy Development, Evaluation, and Goal Achievement. Systems Thinking Press.

Hadaya, P., Stockmal, J., et. al. (2023) IASPBOK 3.0: Guide to Strategy Management Body of Knowledge International Association for Strategy Professionals.

Haines, S. and McCoy, K. (1995) SUSTAINING High Performance: The Strategic Transformation to A Customer-Focused Learning Organization. CRC Press.

Lovallo, D. and Kahneman, D. (2003) Delusions of Success: How Optimism Undermines Executives’ Decisions. Harvard Business Review, 81(7).

Mayne J. (2001) Addressing Attribution Through Contribution Analysis: Using Performance Measures Sensibly. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 16(1), 1-24.

Pearl, J. (2009) Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference Cambridge University Press, New York.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr Lewis Atkinson (CEng, CChem, BSc, PhD (Chem Eng), MBA, PSM) is a Global Partner with the Haines Centre for Strategic Management Limited (t/a The Systems Thinking Approach®) and has government, private, and non-profit clients in Australia and internationally. Lewis is a unique innovation professional with a solid technical and financial grounding, which, combined with his systems-thinking superpowers, enables him to see patterns, pathways, and solutions that others do not.

E: lewis@hainescentreaustralia.com.au

Barbara A. Collins (B.A. (Soc. Psy.), M.S. (Education), SMP Pioneer #019) has more than 20 years of experience as a manager and department head in both government and private organizations and more than 30 years’ experience in organization development and strategic planning as both an internal and external consultant.

E: barbaracollins36@me.com

FIGURE 2: REINFORCING STRATEGIC MECHANISMS AT WORK AT A WHOLE-OF-MARKET SYSTEM LEVEL MLA BEEF PROMOTIONAL PROGRAM STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK CONSUMER CAMPAIGN CHANNEL ENGAGEMENT GROWS

BEEF

SHELF SPACE) BELOW-THE-LINE POINT-OF-SALE

FOODSERVICE MENU INSPIRATION

PHYSICAL AVAILABILITY OF

(DISTRIBUTION,

MATERIAL,

GROWS MENTAL AVAILABILITY OF BEEF (SALIENCE, CONSIDERATION) RefneStrategy SeasonalMeal Campai g n s Supply ChainCollaboration C a t e go r y Development

& PR

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 11 RETURN TO CONTENTS

GETTING “STRATEGY” INTO YOUR “STRATEGY FRAMEWORK”

BY PETER COMPO

BY PETER COMPO

Most people would presumably agree that a strategy framework, often called a strategic plan, is essential for making change and innovating. A strategy framework consists of various choices and combinations of vision, mission, goals, priorities, initiatives, pillars, plans, tactics, diagnosis, metrics and so on. Yet, the one component that is most often missing in a strategic framework, is a strategy. One reason for this absence is confusion about what strategy is, including the belief that the framework with all of its components –often including long lists – is itself the strategy. The objective of this article is to clarify the difference between a strategy and a strategy framework and introduce the strategybottleneckaspiration triad, the design of which is a valuable first step for incorporating a strategy into a strategy framework.

STRATEGY: THE CENTRAL RULE OF A STRATEGY FRAMEWORK

Figure 1 presents and defines each of the components of a full, but simpler, strategy framework. Each component

DOWNLOAD OR PRINT THIS ARTICLE RETURN TO CONTENTS 12 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE

has a unique role in bringing the organization or system from a current state to a future state. Note that only large and complex endeavours will require the use of every framework component. Of particular importance is the role of rules, sometimes called policies, which provide real-time guidance for making choices and taking action during framework implementation. The strategy component is the central rule that guides and unifies all actions and choices towards overcoming what is in the way of the organization’s aspiration, in other words, for “busting” the bottleneck to your aspiration. Tactics are rules that apply to smaller scopes of the endeavor. Busting means to lessen, get around, or eliminate what is in the way of the aspiration. The aspiration determines the scope and aim of the endeavor.

DESIGNING A STRATEGYBOTTLENECK ASPIRATION TRIAD

The strategybottleneckaspiration triad, shown in Figure 2, is the core of the strategy framework. The triad is derived from an influence-diagram model of adaptive systems. It is written with back-arrows to indicate that the bottleneck is derived from the organization’s capabilities relative to the aspiration, and the strategy is derived from the bottleneck, not from the aspiration directly. The fluted shape indicates that when working backwards from an aspiration, the required number of choices and actions grows dramatically. The strategy must unify all of these choices and actions. The triad is aligned to varying extents with the

COMPONENTS ROLE

TWO EXAMPLES OF EACH Values

Statement of that which has intrinsic worth or cannot be violated

Aspirations Vision Mission Goals

Diagnosis Propositions

External constraints

Scenarios

Bottleneck

Rules

Strategy (central) Tactics

Plans/Initiatives

Projections

Metrics

Milestone adherence

Description of your (believed to be) desired future state

Analysis of the dynamics of the internal and external world in which you operate

Real-time guidance for taking actions and decisions to bust bottlenecks

Feedforward simulations and intended actions for coordination, synchronization, and reality testing

Feedback to understand how the system is evolving

works of Rumelt (2011, 2022), Sull and Eisenhardt (2015), Goldratt (1990), and Xiu-bao Yu (2021).

The following four activities introduce the basics of desiging a triad and incorporating the results into the strategy framework using an emergent approach. Such an approach uses an agile design process that begins with a minimum essential draft that is then refined, not a buildup in sequential steps. Think of it as solving a puzzle guided by design principles.

Value: Low carbon footprint/integrity before profits.

Vision: Grow in Africa/NGOs with limited technical skills enabled to use Al.

Mission: Change the organization’s culture/ create a new premium product line.

Goal: Reduce Inventory by 40% in 15 months/ increase gross margin by 20% in two years.

Prop: 20% cost advantage/brand recognition.

Ext. Const: Cannot sell to Russia/ environmental regulation.

Scenarios: Prime rate at 2% and at 6%/ competitors abandon China.

Bottleneck: Product line is too complicated/ organization unaligned.

Strategy: Stop investing in the product line XYZ/migrate to fully digital operation stepwise over five years.

Tactic: Outsource product testing/ new hiring policy.

Plan: Complete stability testing by 4/15/2026 or set up new sales office in Nigeria by 9/15/2025.

Projection: African market will grow 15%/year for five years/we will increase capacity by 90% in three years.

Metric: Average quarterly sales price in Africa/policy adherence by product group.

Activity 1: Draft the Triad

The strategy team drafts a triad by working backwards from an aspiration to articulate possible bottlenecks and strategies for busting the bottlenecks. Like everything else in agile strategy design, an aspiration may change as the overall framework evolves and as the implications of the envisioned future state become clear. The one exception is if leadership supplies non-negotiable marching orders. All three types of aspiration – vision, mission, specific goal – are not needed. Choose the type that best captures the aim of the endeavor.

An aspiration can range from a massive vision or mission for creating an entire new business or product platform to improvement of an existing one. The need for improvement can range from the desire to capture new opportunities to dissatisfaction with current performance, up to response to a crisis. In every case, the design approach is the same and it is the aspiration, not the strategy, that sets the scope and time horizon for the endeavor. Strategy is not just for long term. It is for achieving any future state that has uncertainty and requires tradeoffs to acheive.

FIGURE 1: A STRATEGY FRAMEWORK (STRATEGIC PLAN) SHOWING STRATEGY AS ONE COMPONENT

Aspiration (Believed to be) desired in future state

What

in the way

Bottleneck

is

BOTTLENECKASPIRATION TRIAD

Central rule that guides choices and actions Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Choices Actions Actions Actions Actions Actions Actions Actions Actions Actions Choices

FIGURE 2: THE

STRATEGY

Strategy

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 13 RETURN TO CONTENTS

Consider the example of a product line that has grown at a good rate over several years but leadership is dissatisfied with its profitability. A team is formed to design a strategy framework to achieve raising gross margin by 12% in two years. Figure 3 shows this aspiration (a specific goal) along with the team’s initial brainstormed ideas for possible bottlenecks and strategies. They do this without too much concern for design principles, knowing the ideas will be refined.

When brainstorming, be expansive in exploring what the bottleneck could be using the following list as thought starters. The natural impulse is to consider traditionally measurable factors and outside influences, but bottlenecks come in many varieties and require a hard self-critical look at reality. For example:

• Culture

• Emotions

• Intelligence (market, competition, government)

• Process capability

• Digital capability

• Assets or equipment

• Methods

• Procedures

• Capital

• Complexity

• Lack of alignment or common language

• Bad or missing strategy framework

• Bad or missing tactical policy

Activity 2: Refine the Diagnose of the Bottleneck

Once an aspiration, possible bottlenecks, and strategies are identified, the team can focus on debating and discovering which is truly in the way of the aspiration – the dominant bottleneck. While there is no simple formula for doing so, three guidelines can help determine if the bottleneck selected is the correct one. The first guideline is that the bottleneck should not be extremely easy or impossibly hard to bust. For example, the bottleneck in Figure 3, “We have not communicated the margin imperative,” is in many cases trivial because the team can just go do it. The bottleneck, “Our factories are in a high-cost region,” might be impossibly hard to bust and therefore not useful either if, for instance,

Strategy? Bottleneck? Aspiration

1. Reduce raw material and supply chain cost by 15%, increase yields by 5% and first pass quality by 15%, and raise prices for highest cost products

2. Launch fewer new products but spend more time on designing them for lower cost

3. Change the product line to the right balance between features for customers and cost

4. Create three initiatives: raw material cost reduction, supply-chain simplification, and customer understanding

• Marketing is used to getting whatever they want

• Marketing ignores the cost of the product features they demand and manufacturing is accused of not being “customer-focused” if they object

• Our factories are located in a high-cost region

• Our culture is growth at any cost

• Our profitability is in the bottom quartile of our industry

• We haven't communicated the margin imperative

relocating the factories will cost more than five years of earnings.

The second guideline is that the bottleneck should not be simply a restatement of the aspiration or the reason for the aspiration. “Our profitability is in the bottom quartile of our industry,” in Figure 3, may be a more vivid description of the need for improved margins, but the team already knows that profitability is lacking. The third guideline is that the bottleneck should not be a list of items because listing drives the thinking away from discovering what is the dominant bottleneck in the way of the full aspiration. There will always be multiple secondary bottlenecks, but it is the role of tactics to bust these. Working to identify the dominant bottleneck is invaluable because identifying the problem is a problem half solved, as the adage goes.

The other brainstormed bottlenecks, shown in Figure 3, pass these three guidelines. Each could be the right one to bust. Only further investigation of the organization and value chain can lead to determining which is truly limiting progress.

After debate and investigation, the team agrees that the true bottleneck in Figure 3 is “Marketing ignores the cost of the product features they demand and manufacturing is accused of not being ‘customer focused’ if they object.” It’s concluded that there’s no selfish intent, just a naive organizational belief that 'if customer are happy, profit will follow.'

Raise gross margin by 12% in two years

Activity 3: Refine the Strategy

The strategy designed to bust the “Marketing ignores the cost” bottleneck identified during Activity 2 was also articulated in Figure 3: “Launch fewer new products but spend more time on designing them for lower cost.” The strategy team believes this rule will bust the bottleneck because launching fewer products will allow time for the organization to learn the sweet spot between features for customers and product cost.

This rule illustrates an essential feature of a strategy, that it must be somewhat abstract. The strategy does not say which products to produce or which detailed choices to make. Rather, it establishes the boundaries, or “guardrails” as Rumelt says (2011), within which choices and actions will be guided.

There is no magic recipe for finding the strategy rule, or any framework component for that matter. Just as there are for bottlenecks, however, there are design principles and guidelines to help. In particular, there is a set of strategy tests called the Five Disqualifiers – opposite, list, number, duplicate, and excluded – which enable clarity. The focus here will be on the first three disqualifiers.

If the opposite of a statement is absurd, it is at best a goal, but often a cliché because there are no tradeoffs associated with it. A tradeoff is a sacrifice in one area that enables an even greater benefit in another. All strategies must have

RETURN TO CONTENTS

FIGURE 3: DRAFT TRIAD IDEAS FOR THE ASPIRATION OF INCREASING PROFITABILITY

14 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE

tradeoffs. Consider the proposed strategy, from Figure 3, “Launch fewer new products.” The opposite is quite reasonable. However, the third strategy alternative, “Change the product line to the right balance…” fails the opposite disqualifier because it is an aspiration. Who would want the wrong balance?

A list of choices of pillars, priorities, goals, plans, or initiatives is not a strategy. Yet the vast majority of “strategies” are just lists. Lists are popular because they circumvent the need for tradeoffs. “We’re going to do everything that’s important.” But when everything matters, nothing matters. Writing down everything that might be important to achieve a given aspiration obscures what must be done: busting the bottleneck. The fourth strategy alternative from Figure 3, “Create three new initiatives: raw material cost reducation, supply-chain customization, and customer understanding” fails the list disqualifier.

Finally, if the statement has numbers, it is usually a goal and sometimes a tactic. The first strategy alternative fails both the list and the numbers disqualifier.

If a compelling strategy is not 'emerging from the triad,' the team may need a Strategy Alternative Matrix (SAM) for the systematic development and evolution of strategy

framework alternatives. The SAM is a special type of decision matrix that enables exploration of full frameworks each with a unique strategy rule. In fact, in most endeavors, a SAM is recommended. The SAM enables both clearer articulation of the fitness criteria by which strategy alternatives are judged – both objective and subjective using words and numbers – and greater creative tension for discovering new alternatives.

Activity 4: Integrate into Strategy Framework

Once the triad is complete (remember, this will not be sequential in a real situation), the other necessary framework components can be designed, including plans, tactics, and metrics for implementation (Figure 4). Most endeavors will require a more complete diagnosis beyond simply stating the bottleneck. Additionally, the inclusion of values and additional tiers of aspirations may be required. Organizations with hierarchies and multiple functions need subunits such as IT, HR, operations, and R&D to have strategies tailored to achieve their unique aspirations while aligning with the overall corporate aspiration. This technique is called Nested Strategy Frameworks and it ensures that not only are lower-level frameworks properly, and minimally, constrained by higher-level

GOAL RAISE GROSS MARGIN BY 12% IN 2 YEARS

Diagnosis

Bottleneck: marketing ignores the cost of the constant stream of products they demand and manufacturing is shut down if they push back

Strategy Launch fewer new products but spend more time on designing them for lower cost

Plans • Product manager: socialize the new product strategy broadly by April 15 (hopefully all departments were involved in the strategy design process)

• Sales leader: inform early-adopter customers of the extended product timeline by May 1. Determine by June 1 if the product JSB.1685, scheduled for 3Q launch, can be delayed until 4Q.

• R&D: complete evaluation of new flexible raw materials for existing products by October

• Operations director: hire or engage consultant with lean expertise to simplify the supply chain (2Q)

ones, but that peer frameworks are consistent with each other. Recognize that no matter how compelling the framework, when implementation begins, new choices will be needed, including choices around the specifics of product design, manufacturing, and target customer segments. It is the strategy rule and the rest of the framework that guides these choices. Furthermore, frameworks require modification during implementation. If the metrics are designed properly, including the measurement of adherence to the rules, not just results, the team will be triggered to modify the framework if new information or insight demands it.

CONCLUSION

A strategy is the central rule of a strategic framework, not the framework itself. This short article presents the basics of the strategybottleneckaspiration triad, which serves not only as an excellent illustration of the function of the strategy rule but an excellent starting point for full strategy framework design. For full details of all the concepts presented here, see Compo (2022 and 2024).

REFERENCES

Compo, P. (2022) The Emergent Approach to Strategy Business Expert Press.

Compo, P. (2024) The Five Task Sets, a Guidebook to the Emergent Approach. www.emergentapproach.com

Goldratt, E. M. (1990) Theory of Constraints. North River.

Rumelt, R. (2011) Good Strategy/ Bad Strategy. Crown Currency.

Rumelt, R. (2022) The Crux. Profile Books.

Sull, D. and Eisenhardt, K. (2015) Simple Rules: How to Thrive in a Complex World. Houghton.

Yu, X. (2021) The Fundamental Elements of Strategy. Springer.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Tactics

Metrics

• Institute that all product developments will be managed through a new Agile-Lean protocol, with representation from all departments; R&D director to lead

• Segmentation rules will determine which customers will be allowed highercost products (Product Manager)

• Business director audit if all departments are adhering to the new strategy and tactics (monthly, then quarterly if audits are positive)

• Raw material flexibility milestones met? (quarterly)

• Cycle time and yields by product (monthly)

FIGURE 4: EXAMPLES OF FRAMEWORK COMPONENTS FOR THE MARGIN IMPROVEMENT ASPIRATION

Peter Compo, PhD, is the author of the book, The Emergent Approach to Strategy: Adaptive Design and Execution (www.emergentapproach. com). He was formerly the director of integrated business management at E.I. DuPont. E: pcompo@emergentapproach.com

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 15 RETURN TO CONTENTS

Develop foresight internally. Find out what Natural Foresight® offers over established strategic tools. Full textbook available for free at: tfsx.com/guide

EXPLORING NATURAL FORESIGHT: TFSX Certifcation, Training, and Consulting

Aforesight-empowered framework will change the way you practice strategy.

“For those of us who are trained strategists, adding foresight to our toolkit is a game-changer,” says Yvette Montero Salvatico, Co-Founder and Managing Director of TFSX. “Futures thinking allows us to level up in a way we haven’t seen in the strategy field for a long time.”

Strategic Foresight broadens mindsets to understand emerging issues across multiple futures and pulls multi-faceted insights to the present, informing everyday decisions. It views futures as non-linear, uncertain worlds of possibility unlocked through global trends research and participatory innovation. Strategists who make Strategic Foresight decisions create resiliency for the organization in a VUCA environment.

TFSX’s Natural Foresight® Framework takes a practical approach to Strategic Foresight, leveraging the complexity evident throughout natural systems.

Professional strategists can start embracing complexity through considering the future as a spectrum with two ends – the push and the pull. Trends we see today, such as machine learning or radical life extension, collide into new problems and opportunities that push society into the future. On the other end of the spectrum, short- and long-term decisions act as a “pull,” so the organization moves toward a desired future ambition, or more accurately, pulls the future to today.

“TFSX’S NATURAL FORESIGHT® FRAMEWORK TAKES A PRACTICAL APPROACH TO STRATEGIC FORESIGHT, LEVERAGING THE COMPLEXITY EVIDENT THROUGHOUT NATURAL SYSTEMS.

“In essence, we’re all creating the future every day with the actions we take,” says Yvette. “The tools of Natural Foresight allow us to do that more consciously, collaboratively, and transparently.”

The Natural Foresight framework has four facets with the following goals:

• Discover: Recognize cognitive biases that distort our present and future strategic decision making, countering our subconscious judgment for improved performance.

• Explore: Identify insights using a structured process of trend, value, implications, and pattern identification, translating this outside-in data into actionable strategy.

• Map: Reframe long-term strategies and cope with uncertainty by developing multiple scenarios that ultimately increase organizational resilience, adaptation, and transformation.

• Create: Integrate the opportunities and challenges into today’s organizational processes to fuel futureempowered executive development, strategic planning, strategy design, and ultimately culture change. Yvette and TFSX Co-Founder Frank Spencer have proof that this framework is a great addition to any strategist’s toolkit. Natural Foresight is the most widely used foresight framework in the world, and was developed as a by-product of decades of consultative work. After initially delivering results for Walt Disney Company’s first futurist workforce, the framework is now the body of competency and knowledge for the only Strategic Foresight certification pathway. “It’s a new vehicle by which strategists can practice their craft and overcome organizational inertia that prevents change, which strategists battle every day,” says Yvette.

“A strategist may have the most carefully thought-out plan in the world, and it can tell you exactly what’s going to happen and what the company should do,” she states. “But if you can’t get anyone to buy in, it just sits in a binder collecting dust on a shelf. If you allow for executives and leadership to witness the change and feel that they also have ownership in deciding how the future is run, not just for their companies, but for the larger world – that completely changes how the strategy conversation occurs.”

Foresight is not about putting ideas in a time capsule and looking back in 2035 to see if they were accurate. Instead, it’s about imagining futures that are rooted in those we want to create today. Based on those visions, we determine what it will take to pull those aspirations to the present.

SPONSORED CONTENT

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 17 RETURN TO CONTENTS

EMOTIONS AND PURPOSE:

HOW TO CREATE A STRATEGIC PLAN CARE ABOUT

THAT PEOPLE REALLY

DOWNLOAD OR PRINT THIS ARTICLE 18 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE RETURN TO CONTENTS

BY TIM KELLEY

In today’s rapidly evolving business environment, a clear, strategic plan is paramount. Without one, organizations risk being overtaken by market, technological, and geopolitical changes. Unfortunately, most strategic plans fail to deliver their full potential (Butler, 2022), which can be attributed to overlooking a key factor in human decision-making: emotions (Damasio, 1994). After all, humans will make the decisions about strategy adoption, implementation, and execution. This paper proposes an emotionally-based, purpose-driven method to create strategic plans that maximize motivation.

A HIGHER PURPOSE TO MAXIMIZE EMOTIONS

Traditional strategic plans include a vision, mission, goals and objectives, a SWOT analysis, KPIs, and an action plan. A vision is a description of a desired future state; usually a bigger, more successful version of the company. The mission expresses what the company does, but not the purpose, more commonly known as the “why.”

A well-articulated purpose describes why the company exists. A higher purpose transcends functionality and taps into emotion and motivation, helping employees find value in their work. Research shows that 73% of employees in purpose-driven companies are engaged (Vaccaro, 2018), in contrast to the global average of 23% (Gallup, 2023). This is the tangible impact of a higher purpose.

According to the somatic marker hypothesis (Damasio, 2003), emotions start as physical sensations before being interpreted by the emotional, or limbic, brain. While thoughts occur in the cerebral cortex, emotions involve the body, limbic brain, and cerebral cortex. This leads to defining “emotion” as “a physical sensation plus context” (Barrett, 2017). The process of decisionmaking starts in the emotional brain and moves to the rational brain, or the prefrontal cortex (Damasio, 1994; De Martino, 2008; Lim, 2011). Therefore, emotions have a much greater impact on decision-making than thoughts. People often make decisions driven

by emotions first and then use logic to justify them. Hence the importance of emotion in strategy.

Employees constantly make emotionally-based decisions about how to spend their time and effort. In a rational, emotionless strategic plan, emotions will be ignored. Weaving a higher purpose into the process creates a strategic plan that captures emotions and increases commitment.

EMOTIONALLY-BASED PURPOSE-DRIVEN METHOD

The emotionally-based, purposedriven strategy method we propose encompasses three phases, and a total of 10 steps, to maximize motivation by engaging emotions. The following paragraphs detail the steps in each of the phases and focus on creating a purpose and vision.

Phase I: Create a Compelling Purpose

The objective of the first phase is to create a purpose that evokes strong emotions, which requires establishing an objective that transcends profit and business success. The phase comprises five steps.

The first step, Engage Employees, starts with the CEO announcing the purpose-finding process. All employees should be invited to participate voluntarily. This gives the strategy team a broad cross-section of the company to help develop the purpose and who will become emotionally connected through their work on the purpose. It is important for the CEO to communicate to the team and the organization the value of having a purpose. The organization should not be surprised by the eventual announcement of the purpose.

techniques for gathering purpose data. The first poses questions to the participants that almost ask about the purpose, such as, “What is the greatest contribution this organization could make to the world?” A lesser-known technique is to seek unconscious purpose information using guided visualization, a form of meditation. This method produces more powerful purpose statements, but it requires much more skill to facilitate. Using either technique yields many responses, most of them uninspiring and useless.

In the third step, Create Purpose Statements, the strategy team analyzes the draft purpose data to extract relevant information. This entails searching the data to identify two key elements: objectives and repeatable activities. An objective, or mission, has an endpoint, such as, “end climate change” or “eliminate poverty in Washington DC.” Once achieved, it cannot be repeated. A repeatable activity, in turn, has no endpoint, e.g., “help people live fulfilling lives” or “show people a better version of themselves.” Repeatable activities are used to create purpose statements.

An objective is written: “Our mission is to…”

A repeatable activity is written: “Our purpose is to…”

The strategy team’s task is to put all objectives and activities into these formats. Deleting ANY data at this stage can ruin the entire process.

During the fourth step, Test Purpose Statements, the participants rate the purpose and mission statements solely for emotional impact, not realism

“ PEOPLE OFTEN MAKE DECISIONS DRIVEN BY EMOTIONS FIRST AND THEN USE LOGIC TO JUSTIFY THEM. HENCE THE IMPORTANCE OF EMOTION IN STRATEGY.

In the second step, Gather Purpose Data, participants generate a large amount of draft purpose information. Quantity is more important than quality. Brainstorming or creative writing techniques to generate purpose statements does not work. The brain simply does not handle “why” questions well. We rather propose two effective

or potential use. The scale presented in Table 1 should be used.

If the group meets in person, each statement should be read aloud in unison. If the group meets via videoconference, mute everyone and have them read a statement aloud. Then each person scores their emotional reaction to that statement from -5 to +5.

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 19 RETURN TO CONTENTS

Use a spreadsheet to capture individual votes and calculate and record scores. Use the mean of the absolute value of the individual votes to calculate the score. In other words, eliminate the sign (+ or -), then average the numbers. A score of at least 4.0 indicates a strong purpose and/or mission statement. You can try different wording to see what produces stronger reactions, but editing statements to remove objections will weaken them. Test ALL edits. If one of the best statements is a repeatable activity and another is an objective, both can be used as a purpose statement and a mission statement. Otherwise, simply use the strongest scoring statement, regardless of type. In the fifth and last step of the first phase, Publish the Purpose, the CEO communicates the new purpose and/or mission to the employees, ideally eliciting emotional reactions through voting. It’s essential to aim for a score of at least 4.0, as the emotions generated by the purpose will power the remainder of the process.

brainstorm in response to the question, “If the purpose and/or mission were manifested successfully, what would be the best possible outcomes for society and the world?” Encourage them to be aggressive and unreasonable, writing down their ideas and reading them aloud to each other. Keep everything that

“ STRATEGIC PLANS THAT IGNORE EMOTIONS OFTEN YIELD DIMINISHED MOTIVATION AND ARE LESS LIKELY TO BE IMPLEMENTED SUCCESSFULLY.

LEADERS MUST CONSIDER THE CRITICAL ROLE OF EMOTIONS IN DECISION-MAKING.

Phase II:

Create Purpose-Centric Visions

The objective of the second phase, Create Purpose-centric Visions, is to create visions that mirror the emotional power of the purpose and/or mission. This phase comprises three steps. During the first step, Create Visions Based on the Purpose, two visions are generated from the purpose. Typically, visions are about the company’s success or its impact on its customers and lack emotional resonance. Employees aren’t inspired to “grow profits by 20%.” A purposecentric vision rather focuses on how the industry, country, or world will be changed by the company successfully manifesting its purpose and/or mission. People care about this in the same way they do about non-profit causes.

This phase uses the strategy team for most of the activities. Have them

elicits an emotional response from the group. Have one or two people organize the “keeper” sentences into a coherent order. The resulting vision could be a paragraph or several pages in length. This is the final vision for the world.

The strategist now asks the group, “What would have to be true about the company for it to create this change in the world?” The responses will yield a picture of business growth much bolder than typical goals. Repeat the process, testing individual sentences aloud with the group and having someone organize the ones that elicit emotional responses into a coherent order (the final vision for the company).

You now have two visions: one for the world the company will create, and another for the company that will create that world. Both should seem audacious to the point of arrogance.

During the second step, Test for Emotions, take the two visions to the participants in phase one. Using the scale presented in Table 1, measure their reactions to the visions. Again, an average reaction score of at least 4.0 is best. Removing sentences that score poorly will raise the average. In the third step, Publish the Visions, publish the new visions to the entire company. Ideally, ask for and measure reactions.

Phase III: Create a Strategic Plan

The objective of the third and last phase, Create a Strategic Plan, is to use the visions and purpose to create an emotionally-based plan. This phase comprises three steps. During the first step, Create Strategic Goals, choose key features of both visions and frame them as goals and objectives. Emotions are generated primarily by the impact of the company on others. In the second step, Test for Emotions, the strategy team tests the goals and objectives using the emotional reaction scale. Articulate the context first: these goals must be achieved for the company to manifest its visions and purpose. Avoid goals not connected to the visions and purpose unless they are needed for the company’s health and survival. During the third step, Finalize the Strategic Plan, create a complete strategic plan (SWOT, KPIs, action plan, etc.) Have the strategy team members rate their emotional reactions to the completed plan. Plan elements unrelated to the visions and purpose will lower the

STRENGTH OF REACTION EMOTIONAL REACTION TYPE EXAMPLE EMOTIONS

positive reaction

reaction Mild interest 0 No reaction -1 Mild negative reaction Irritation, dislike -2 -3 Moderate negative reaction Strong distaste, discomfort -4 -5 Strong negative reaction Fear, hatred, disgust

+5 Strong

Passion, joy, awe +4 +3 Moderate positive reaction Happiness, strong interest +2 +1 Mild positive

TABLE 1: THE SCALE USED TO RATE THE EMOTIONAL REACTION TO PURPOSE STATEMENTS

20 SPRING 2024 | ISSUE 39 | STRATEGY MAGAZINE RETURN TO CONTENTS

ACTIVITY

Phase 1: Create a Compelling Purpose

Step 1.1: Engage employees

SPECIFIC COMPANY EXAMPLE

2/3 of the employees found their personal higher purpose

Step 1.2: Gather purpose data 100% of employees participated in a series of in-person meetings

Step 1.3: Create purpose statements “Our purpose is to inspire people to walk their true path”

Step 1.4: Publish the purpose

Phase 2: Create Purpose-centric Visions

Step 2.1: Create visions based on the purpose World: Create a critical mass in a shift of consciousness in the population. Company: Focus on inspiration in collaboration with top mentors using meditation as the means

Step 2.2: Test for emotions

Step 2.3: Publish the visions

Phase 3: Create a Strategic Plan

Step 3.1: Create strategic goals

Step 3.2: Test for emotions

Step 3.3: Finalize the strategic plan

score. Depending on the planning methodology used, it may be necessary to alter or combine these last two steps.

Following these steps with care and ensuring that rationality does not dilute the outputs will result in a plan in which people are emotionally invested. Leaders should periodically remind employees of the purpose and visions; don’t expect them to remember why they were excited a year ago.

To illustrate the use of the proposed method, we can use the example of an Israeli hightech company that sells software to therapists, counselors, and coaches. With eight years of flat revenue and negative cash flow, the employees were close to giving up. The CEO, however, had found his purpose and wanted to use purpose techniques to jump-start the company’s performance. About half of the employees found their purpose before the strategy process began. Once the emotionallybased purpose-driven method was followed (see main findings in Table 2), the CEO reported that the new product line took off, cash flow turned positive, and revenue grew

Positive cash flow

1M customers by the end of the following year

Focus on the US market Partner with leading mentors Abandon existing product lines CEO to spend one week per month in the US

1226% over the next four years. Clients grew from 4500 to 2.5 million. Table 2 summarizes the process described above with key points from the example high-tech company.

CONCLUSION

Strategic plans that ignore emotions often yield diminished motivation and are less likely to be implemented successfully. Leaders must consider the critical role of emotions in decisionmaking. Furthermore, many consumers and employees, particularly Millennials and Gen Z, prioritize companies with a higher purpose. Neglecting this evolving trend can pose challenges in attracting and retaining young talent and customers. Consequently, future strategic plans should be centered around an inspiring, audacious purpose.

REFERENCES

Barrett, L. F. (2017) How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of Feelings. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Butler, J. (2022) 90% of Organizations Fail to Execute Their Strategies Successfully. IntelliBridge. Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Penguin Books, New York.

Damasio, A. R. (2003) Feeling the Way Through: Learning to Connect with the Wisdom of the Body. Harcourt.

De Martino, B., Kumaran, D., Seymour, B., and Dolan, R.J. (2008) Frames, Biases, and Rational Decision-Making in the Human Brain. Science, 321(5892), 1164-1168.

Gallup. (2023) Global Indicator: Employee Engagement.

Lim, S. L., Padmala, S., and Pessoa, L. (2011) The Neural Correlates of Metacognitive Confidence and Decision Making: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Cerebral Cortex, 21(10), 2161-2170.

Vaccaro, A. (2018) How a Sense of Purpose Boosts Engagement. Inc.com.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tim Kelley works with leaders, companies and countries to create inspiring higher purposes and visions. He has trained over 1000 consultants, coaches and therapists in his methods and works with such clients as Oracle, Deloitte & Touche, Price Waterhouse Coopers, three presidential candidates, and the State of California. W: www.newparadigmgloballeader.com E: timk@transcendentsolutions.com

STRATEGY MAGAZINE | ISSUE 39 | SPRING 2024 21 RETURN TO CONTENTS

TABLE 2: STEPS OF THE PROCESS

Take the Next Step towards Your One Destination

Helping You Escape the Multiple Destination Trap

The biggest challenge that we see organizations face is the “Multiple Destination Trap”. The team members have different ideas of what success looks like and are working on different projects to get there. Or worse, the team can’t decide or get aligned on the common destination, so the targets change from day to day and month to month. This causes uncertainty, frustration, and a lack of progress.

Aligning Your Team Around One Destination

In order to escape the Multiple Destination Trap your team needs to be aligned on both strategic elements like your Vision, Mission, Values, Priorities, Goals, and Actions as well as operational components like: How do we communicate? Who is doing what? And how are we going to track progress?

Building the Capacity for Strategy Implementation

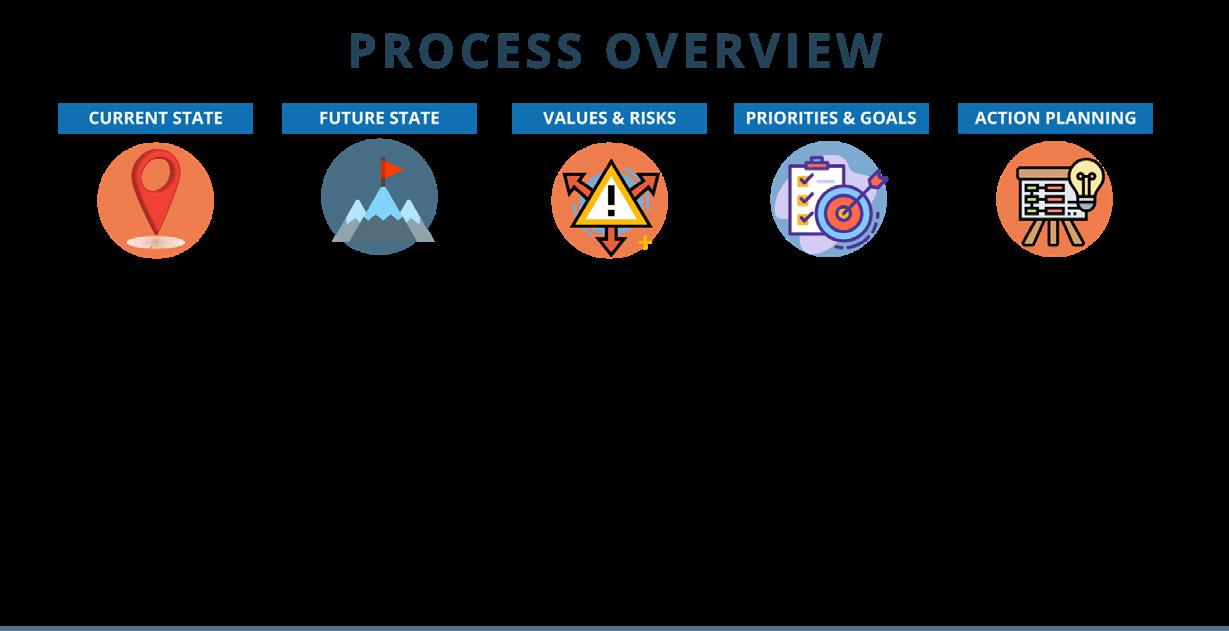

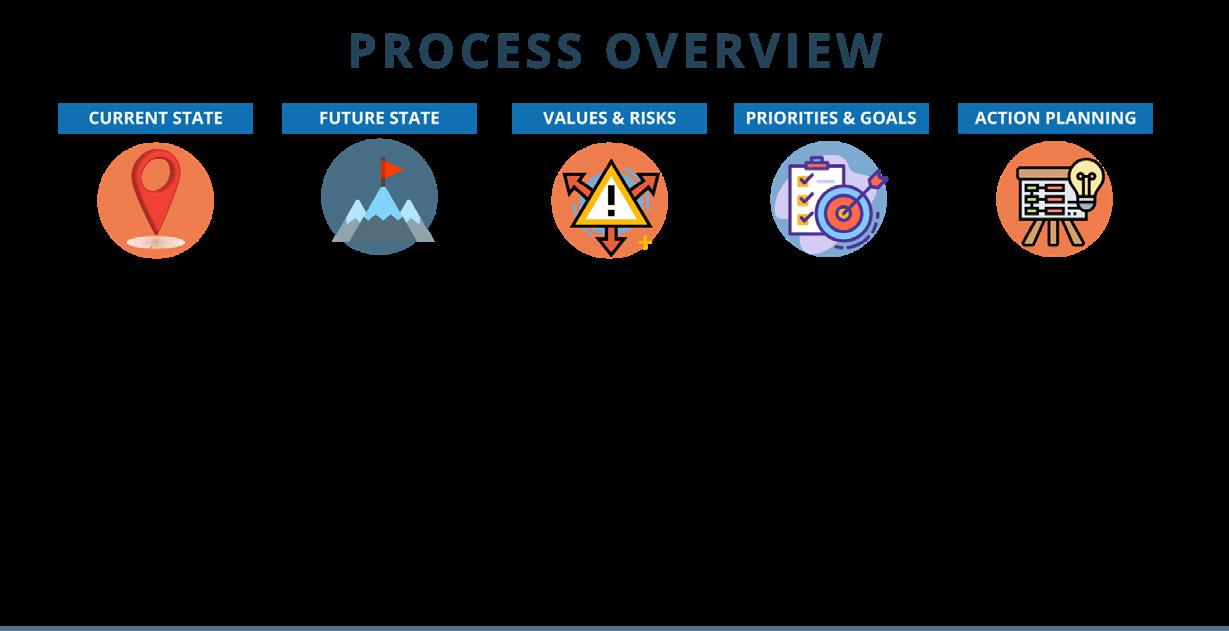

Strategic Planning Process

Getting clarity and alignment as a group is systemic when you have a clear and specific process. Our strategic planning process follows a 5-step process that we go through over two or three days in person.

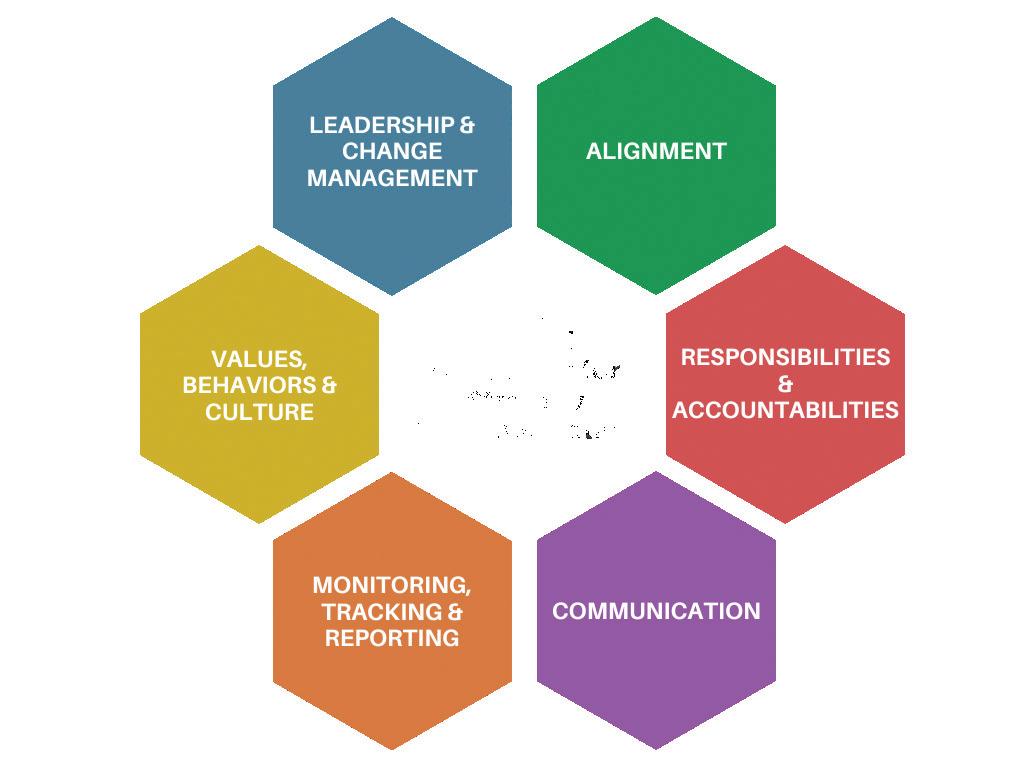

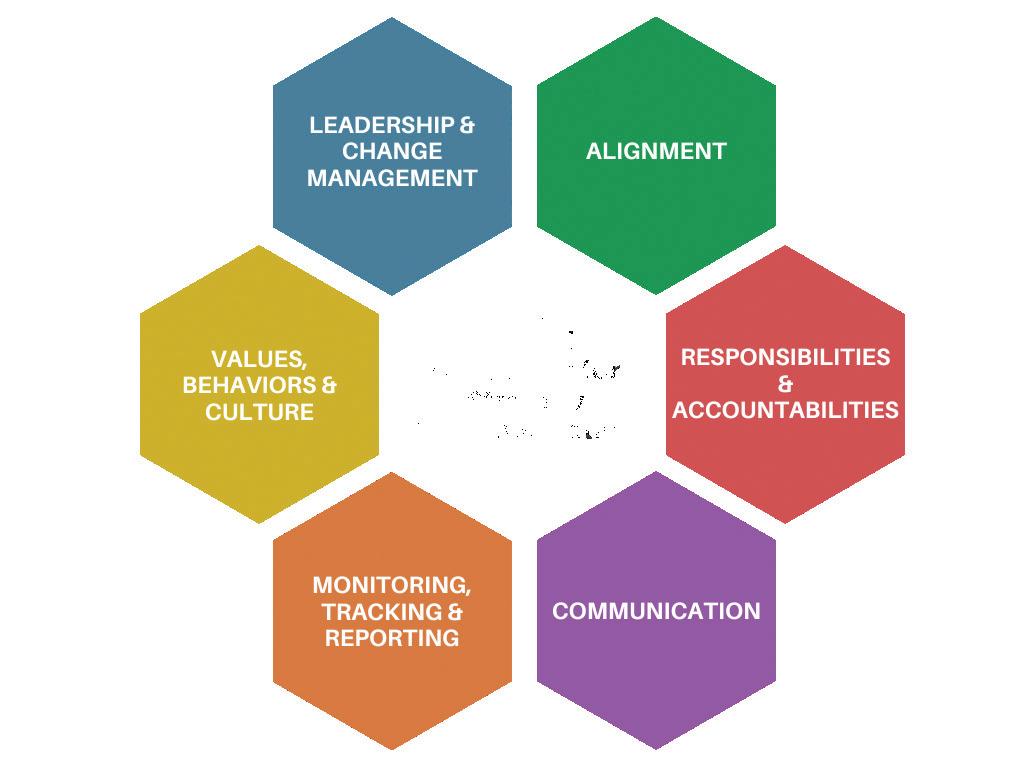

Once your team is aligned on strategic elements of your plan, it’s critical that you schedule in time to review your plan so that it stays top of mind and doesn’t get put on the back burner as the urgent day to day (operational) work takes over. Moreover, the more closely you can tie your big picture strategic work to the operational, the greater progress you will make towards your long term goals. In our implementation packages, we provide accountability, coaching and training within these 6 areas to help your plan moving forward while elevating your team’s capacity and aptitude.

Learn more about SME Strategy's approach. www.SME strategy.net/IASP

SIX

Critical Capacities for Strategy Implementation

A REFRESHING APPROACH TO ALIGNMENT: SME Strategy Consulting

“We understand that senior managers and middle managers are often too engrossed in the day-to-day operations to effectively work on the bigger picture. So, when these leaders get a chance to step back and address these crucial issues, it’s a breath of fresh air,” empathizes Anthony Taylor, CEO of SME Strategy Consulting. When leadership teams collectively zoom out together, they can more effectively see the problems and opportunities within their organizations.

“SME STRATEGY CONSULTING EMPOWERS VARIOUS STAKEHOLDERS AND LEADERS WITHIN ORGANIZATIONS TO ALIGN TOWARDS A CLEAR AND COMMON FUTURE – A FUTURE WITH A SHARED COMPANY MISSION, VISION, AND VALUES.

Most organizations that come to SME Strategy are stuck in what they call the “Multiple Destination Trap,” when different individuals or groups are unclear about where they are headed as an organization, what their priorities and goals are, or who is accountable or responsible for a certain initiative or project. This misalignment causes uncertainty, frustration, and wasted resources within the respective teams and individuals.

SME Strategy Consulting empowers various stakeholders and leaders within organizations to align towards a clear and common future – a future with a shared company mission,

vision, and values. They apply a people-first approach, fostering a sense of contribution and buy-in from all participants. This approach not only aligns teams but also instills a sense of capability and control in the process.

“We guide these groups through a structured process, enabling them to understand each other’s perspectives and align on shared outcomes,” says Anthony. “We then support accountability, follow-up, and training to ensure they reach their desired destination. Most of the time, the shift is from implied to explicit, which helps teams feel secure in their decisions to move forward as a group. Without that explicit conversation and decision-making, a lot is left in a ‘grey area.’”