The Ornamental Oriental:

How Playboy used China Lee to Perpetuate Asian Stereotypes During the Vietnam War

Kelli Reitzfeld

AHIS 469: Critical Approaches to Photography

Professor Ellen Macfarlane April 27, 2020

China Doll, Lotus Blossom, Geisha. Exotic, Dragon Lady, Little Brown Fucking Machine Powered by Rice.

The “Asian Mystique” is not new, nor is it accidental. It is not harmless, natural, or scientific. It is, however, just one of many tools in the “vast control mechanism of colonialism, designed to justify and perpetuate European dominance.”1 This “fantasy of the exotic, indulging, decadent, sexual Orient [has led to Westerners perceiving] women of Asian heritage as docile and subservient.”2 From 17th century French novelist Flaubert, who publicized that “[Oriental women] never spoke for herself,”3 to 1970’s sexologist Howard S. Levy, who advertised that “[Japanese women were trained to] cater to male sexuality and egotism through her inculcated desire to please,”4 to the present-day, slew of “Japanese school girl,” “Asian teen,” and “Torture”5 pornography, these limited (but canonized) sources of Asian representation serves two purposes. First, to otherize Asian women,6 and second, to “maintain the supremacy of the dominant class.”7 Thus, the stereotype of Asian women being a glorified, hypersexual plaything for Western men continues to echo through space and time especially during the Vietnam War when an Asian woman’s “only utility to Westerners came from their sexual submission.”8 Moreover, American soldiers’ struggle with masculinity and conformity during the War called for a resurgence of the Asian fetish. And Playboy picked up. In August 1964, Playboy debuted China Lee, the first Chinese-American and woman-of-color Playmate model. This paper will

1 Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient” in The Politics of Vision: Nineteenth Century Art and Society (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991), 34.

2 Carrie Pitzulo, “Introduction” in Bachelors and Bunnies: The Sexual Politics Playboys (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 6.

3 Edward Said, “Introduction” in Orientalism (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1978), 6.

4 Howard S. Levy, “Introduction” in Oriental Sex Manners (Holborn, London: New English Library Limited from Barnard’s Inn, 1972), 7.

5 Sunny Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence” (Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice, 2008), 292.

6 Robin Zheng, “Why Yellow Fever Isn’t Flattering: A Case Against Racial Fetishes” (Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 2016), 408.

7 Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” 279.

8 Woan, 300.

specifically focus on her Playboy spreads to analyze and contextualize these sexist and racist stereotypes and argue that her inclusion in Playboy August 1964 and April 1965 were far from a progressive step towards diversity. Instead, China Lee’s photoshoots and corresponding literature preyed off the widespread sexually imperialistic mindset towards Asian/American women during the Vietnam War. In both her images and texts, Playboy deliberately highlighted her Eastern heritage and minimized her Western upbringing by subtly integrating callbacks of prejudice ideas against, and photographs of, Asian prostitutes. As a result, Playboy villainized Lee’s nudeness, and thus perpetuated the stereotype of the exotic “Mysterious Orient,” which made her (and thereby other Asian women) just obtainable enough to Western men.

Vietnam, Where East Met West

Before delving into Playboy and China Lee’s problematic photoshoots, it is first crucial to establish how deeply rooted the hatred and desire for Asian women was during the Vietnam War. Between 1955-1975, the United States shipped almost three million soldiers to Vietnam, and their presence made Saigon “an icon of the sex tour industry,”9 infamously dubbing it the “American Brothel.”10 One reason why the sex industry blossomed was because within these tight-knit groups of men, masculinity was proved and determined through sexual performance. Much like how he would earn his manhood though combat, “sexual violence against women [also functioned] as the fundamental ‘tool of war.’”11 Preparators didn’t feel guilty though. “Asian women could not be raped because she ‘enjoyed’ the sexual conquest,”12 they said; prostitution in Asia was justified because Asian societies were “less developed and sophisticated,

9 Woan, 281.

10 Amanda Boczar, “Uneasy Allies: The Americanization of Sexual Polices in South Vietnam” (The Journal of American-East Asian Relations, 2015), 220.

11 Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” 285.

12 Woan, 286.

and therefore inferior,”13 they argued. This attitude resulted in grim consequences. Rape and sexual violence against Asian women were tolerated, encouraged even, because of how rampant how causally it occurred.”14 Local sex workers repeatedly reported “being treated like a toy or a pig by American soldiers [who required them to do] ‘three holes’ (oral, vaginal, and anal), [which] reaffirmed the Westerner’s perception of Asian women as sex objects.”15

The photographs that came from South East Asian brothels depicted this oppression in two eerie ways. First, images like Gillies Carnon’s The Vietnam War (fig. 1) portrayed a grinning Vietnamese prostitute sitting on the lap of a blank-faced solider. She was so eager, so excited, so honored to kiss a Western man that she was blurry from moving too fast for the camera to capture. Meanwhile, his indifference to her implied that 1) these “sexual Oriental” women were so plentiful and willing that her extreme lust for him was just “business as usual,” and 2) he was in control. He was in power. He did not need to “woo” women here, like he presumably would with “picky” or “good moralled”16 women in the States because of how desirable he was to Asian women. The lack of Westerners used to be a cornerstone in “picturesque views of the Orient,”17 but now that he could be seen in the same photograph as her, she was obtainable conquerable. And, in this image, the woman was a mere prop to communicate this overarching, Western-dominating message.

Second, in Nik Wheeler’s American GIs and Vietnamese Prostitutes (fig. 2), an Asian woman’s “submission” and “hypersexuality,” as well as Saigon’s rape culture was reinforced. In this photograph, he surrounded her with a power stance notice his visible muscles, lunged leg,

13 Woan, 285.

14 Woan, 285.

15 Woan, 286.

16 Pitzulo, “Introduction,” 6.

17 Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 36.

and arm on the wall. Even if she was there willingly, she could not easily leave. Meanwhile, she passively “allowed” him to grope her breast, as her arms were to her sides and her posture slightly stiff. He knew his hand-positioning was crude though one could tell by his boyish smirk, the woman’s uncomfortable side-eye to the camera, and the un-intimateness of the publicly occupied space. Her smile was a bit off too, even disingenuous compared to the woman in fig. 1, as though she was silently screaming for Wheeler to help. Then, the backside of her hand subtly and politely pushed the G.I. back near his thigh hidden to not arouse anger in the men (especially given her inherently lower status and assumed consent) and impersonal to not arouse him. This incorrectly assumed consent was likely why neither him nor her were looking at each other and why his eyes were exclusively glued to her breast, only acknowledging the parts of her he had interest in. Still, despite her awkward body language and a perverted hand on her breast, the two people in the foreground continued their conversation as normal, and the two G.I.s outside smiled as they watched their fellow solider grope a Vietnamese woman. They found it entertaining that he used her like an object with which to take “humorous” photos. What these two photos had in common was its “attempt at documentary realism,” a symptom of Orientalism.18 These photographs were made to look like the “readily-available sexuality” of Asian women were factual and definite. Especially considering the Vietnam War was the first televised and widely photographed war, cameras were a symbol of news and objective truth. As if, American soldiers had tapped into a novel and legitimate resource that they were enthusiastic to share back home. Consequently, these images, amongst a plethora of artifacts, enabled American men to bring “back to the United States their stereotypes of Asian women as ‘cute, doll-like, and unassuming, with extraordinary sexual powers;”19 This “became

18 Nochlin, 33. 19 Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” 292.

an expectation White men had of all women of Asian descent.”20 As a result, half a century after the war subsided, “several million tourists from Europe and the United Stated visited Thailand annually, many of them specially for its sex industry”21 an industry that continues to boom today because of the same dangerously outdated stereotype against Asian women.

Magazines and Magazines: Playboy and the Vietnam War-Era

Attitudes

Playboy’s role in perpetuating this sexually imperialistic mindset was nothing to scoff at. But because of the magazine’s suggestive subject, many critics dismissed it as just another masturbatory aid. From there, Playboy gained the notorious reputation of “entrapping young American men [in a state-of-mind] where bachelorhood [was] a desired state and bikini-clad girls [were] overdressed, where life [was] a series of dubious sex thrills.”22 This sentiment mirrored the larger societal culture war between many American soldiers and conservative religious/civil leaders. These leaders “warned of the social dangers of moral laxity”23 that accompanied the “[beguiled] promise of indulgent and unabashed pleasure [overseas that caused young men to] throw off their work ethic.”24 Here, not only did moral conservatives highlight and make mainstream the stereotype that “promised” men sex from Asian women abroad, their perception also villainized these women too. Moral conservatives implied that it was her fault, her promiscuity, her evil seductiveness not his disgusting violence that would ultimately lead to his reduced work ethic and the eventual downfall of America.

Moreover, moral conservatives also blamed Playboy for propagating and promoting hypersexuality during tense wartimes. They protested that the magazine’s message would

20 Woan, 292.

21 Woan, 284.

22 Elizabeth Fraterrigo, “Introduction” in Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009), 1.

23 Fraterrigo, “Introduction,” 2.

24 Carrie Pitzulo, “The Pulchritudinous Playmates” in Bachelors and Bunnies: The Sexual Politics Playboys (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 60.

discourage men and women from “[fulfilling] their traditional duties as husband and wife [and] the country would lack the stability necessary to battle the Soviets.”25 Consequently, America found itself in a “crisis of masculinity.”26 Meanwhile, men faced social pressures to conform to the traditional pre-war wife/kids/picket fence status quo when many wanted to experiment with their masculinity via the casual sex which was uncoincidentally synonymous with Asian prostitutes that they read about in Playboy

However, the truth about Playboy’s following was much more complex. The nude models only accounted for a sliver of Playboy’s early popularity. Instead, its success among soldiers was largely contributed to the fact that the adamantly anti-war magazine gave dissatisfied and frustrated soldiers an outlet to vent about Vietnam.27 By luring men somewhat by nude photos but mostly through recognition, validation, and camaraderie, Hugh Hefner’s publication was able to connect with American soldiers in Vietnam and helped them understand society, culture, and politics in ways that appealed to them. In other words, the magazine provided a much-needed escape into affluence and extravagance and consumerism and mobility and gentlemanliness outside of service.28

In return, their loyal following elevated Hefner’s “girlie mag” into a dependable tastemaker, an authoritative teacher-of-life, and a role model of sorts. Thus, Playboy was not a trivial pornographic publication; men looked to Playboy for guidance in such uncertain and masculine-confused times. So, when “Playboy denounced conformity… [and espoused] the virtues of embracing sexuality”29 to men who learned to yearn for Hefner’s “revolutionary” sex-

25 Pitzulo, “Introduction,” 3. 26 Pitzulo, 3.

27 Amber Batura, “The ‘Playboy’ Way: ‘Playboy’ Magazine, Soldiers, and the Military in Vietnam,” (Liden, Netherlands: Brill, 2015), 225.

28 Batura, 223.

29 Batura, 222.

filled bachelor life, Playboy’s message was deeper than just intercourse. It was a lifestyle of reclaiming his powerful masculinity through multiple facets of life. With unnerving detail, Gentleman’s Quarterly (GQ)’s article titled “Oriental Girls” described how Western men used Asian women as a “lifestyle” to restore their toxic masculinity:

When you get home from another hard day on the planet, she comes into your existence, removes your clothes, bathes you and walks naked on your back to relax you…She’s fun you see, and so uncomplicated. She doesn’t go to assertiveness-training classes, insist on being treated like a person, fret about career moves, wield her orgasm as a non-negotiable demand…She’s there when you need shore leave from those angry feminist seas. She’s a handy victim of love or a symbol of the rape of third world nations, a real trouper.30

Therefore, China Lee’s nudes in the August 1964 issue was less about surface-level sexuality. Rather, it stood for the systemic oppression against “well-trained” Asian women, which made men feel dominant “in the home, workplace, and the world”31 though sex. His obsession with Asian women was likely “motivated by an antifeminist backlash in men who wished to return to traditional gender roles supposedly exemplified by the demure, obedient Asian woman.”32 On top of that, her soft features and shorter stature was “the perfect complement to the exaggerated masculinity of the White man.”33 At any rate, Playboy’s inclusion of an Asian-American woman, given the social climate, made China Lee and other Asian/American women a part of that “taboo” and “degenerative” rhetoric that much of society condemned.

China Lee in Playboy’s August 1964 Issue

Hugh Hefner framed China Lee’s addition in the August 1964 issue as progressive he declared that he “bucked social convention and chose to include any woman who met the

30 Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” 279.

31 Pitzulo, “Introduction,” 3.

32 Zheng, “Why Yellow Fever Isn’t Flattering: A Case Against Racial Fetishes,” 405.

33 Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” 279.

Playboy ideal of beauty, no matter their race.”34 Although, this did not explain why he chose China Lee, a Chinese-American model, specifically at this exact point-in-time, before, for example, Jennifer Jackson, the first Black (and second woman-of-color) Playmate who appeared in the March 1965 issue. While, “the conflation of Asian women with sexual availability was [already] firmly established in many readers’ mind”35 and on-brand with Playboy, upon deeper investigation, the answer was a bit more political.

As previously mentioned, many American soldiers used Playboy as a morale booster a much needed pick-me-up after it became clear that the Vietnam War was a “civil war, a nationalist movement, or an isolated Communist insurgency with no ties to the People’s Republic of China or the Soviet Union.”36 However, tensions escalated in Vietnam, climaxing when Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted Lyndon B. Johnson the ability “to bomb North Vietnam without a formal declaration of war.”37 During this time, many men already lost hope after they sacrificed everything for a seemingly unwinnable war few even wanted to participate in. So, when the government provoked the war further, it was demoralizing. This was where China Lee came in. Playboy provided these dispirited men with China Lee’s centerfold (fig. 3) that he could masturbate to whenever and however he wanted, for “the connection between sexual possession and murder [would give him] absolute enjoyment.”38 The logic was identical to why there was so much sexual violence in Saigon: “the [sexual] conquest of Asian women correlated with the conquest of Asia itself.”39 Thus, if these soldiers could not feel direct satisfaction and pride from defeating communism in Northern Vietnam (and indirectly

34 Batura. “The ‘Playboy’ Way: ‘Playboy’ Magazine, Soldiers, and the Military in Vietnam,” 229. 35 Batura, 229. 36 Batura, 232. 37 Batura, 229. 38 Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 43.

39 Woan, “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” 282.

People’s Republic of China) in real life, fig. 3 could at least provide him with a substitute that instantly gratified. That is to say, regardless of the War’s outcome, in his head, he won.

Figure 3, China Lee’s centerfold, is also worth formally exploring. Her pose and backdrop were uncannily close to the prostitute’s in fig. 2 to remind the viewer that Lee was powerless to his control. Like in fig. 2, she was pinned against a wall, but in this photo and unlike the other, her demeanor was much more relaxed. This told the viewer that she didn’t need a G.I. to threaten her from leaving because she wasn’t going anywhere nor would she (hypothetically) stop the viewer from touching her. Then, Posar, the photographer, invited the viewer in to stand next to her, allowing him to grope her like the G.I. in fig.2, by skewing China Lee to the left and leaving an empty space to the right. He would see that her breasts were in clear view; however, there was still some mystery. There was a miniscule air of secrecy between her hips and pelvis only hidden by an unsecured cloth she tenderly grasped with her fingertips, just barely out of reach of him. This maintained the distant “Mysterious Orient” stereotype: that Asia and Asian/Americans were forever foreigners who Westerners would never completely see or understand all of. Similarly, the translucent curtain in the background, too, made some objects (like the circular lighting fixture in the back) recognizable, yet what was beyond top-secret no matter how many gleaning peaks and glances Westerners took. That way, he could imagine the “Orient” and Asian women to be anything he wanted them to be. However, the literature attached to China Lee’s Playboy centerfold certainly didn’t mitigate any stereotypes either. First and foremost, her spread was titled “China Doll,” (fig. 4) a blanket slur used against (submissive) women of any Asian ethnicity. Although China Lee was of Chinese descent, she and her eight siblings were born-and-raised in Louisiana. She was of American nationality and identified at such; however, Playboy made sure to highlight her

“

Chineseness” when they called her “China Doll” and an “Oriental charmer”40 in the article’s subtitle. Both these “nicknames” were bizarre because even though her chosen stage name itself was rather derogatory already, the writer still did not call her by her preferred name as though she was subhuman (like the GQ excerpt suggested). Instead, they made her generic, identity-less by using offensively vague terms like “Oriental” when her ethnicity was literally in her name. In contrast, when Jennifer Jackson, the first Black model, got her spread the next year, “Playboy [got] praise because ‘not once was there mention of [Jackson’s] race…[and she thought] it was a blessing to see her treated as another citizen and human being.”41 Hence, this racist treatment was solely due to Lee’s Chinese heritage. Even though there are horribly pejoratives towards Black women like ‘Jezebel,’ Playboy opportunistically capitalized on the Vietnam War and the resulting heightened sexual imperialism of the “Mysterious Orient.”

Furthermore, the author of Lee’s accompanying literature tried to justify Playboy’s overt Orientalism by “insisting on [including a] plethora of authenticating details, especially on what might be called unnecessary ones.”42 Thereby, he reframed the “would-be” racism into an educational read as though China Lee spoke for all Asian/Americans. First, he quoted China Lee saying, “Though I was born in America, my folks still follow Oriental ways: They speak the old language, read the old books, and follow old customs”43 to reiterate how “the Oriental world [was] a world without change, a world of timeless, atemporal customs and rituals, untouched by the historical processes that were ‘improving’ Western societies.”44 Not only had the notion of “old” and “the Orient” been used to justify White-man’s-burden type of (sexual) imperialism in

40 “China Doll” in Playboy vol. 11 no. 8 (New York, NY: Playboy Press, 1964), 68.

41 Batura, “The ‘Playboy’ Way: ‘Playboy’ Magazine, Soldiers, and the Military in Vietnam,” 230.

42 Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 38.

43 “China Doll,” 68.

44 Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 35-36.

Asia, the author also included it because it qualified her “Americanness.” She noted that she was raised in the United States, and presumably had gone through the same American school system, brought up on the same American cultural references, and for all intents-and-purposes was as American as her Western reader. However, that clashed with her “Asian” look and messed with the “Asian aura” market appeal, so by mentioning her parents’ not her othering behaviors, some of the mystery was preserved. China Lee had been “successfully” exoticized. Her public perception was likely to be sufficiently Asian to perform the submissive sexual acts that Western men sought after, yet just American enough to conform into society as the bring-home-to-yourparents type woman the best of both worlds. Another peculiar way the author brought in China Lee’s parents as an attempt to otherize her was when he mentioned that she was the only one “not now in the Oriental restaurant line.”45 In addition to reinforcing the impression that “Oriental” people did not “evolve” by remarking her whole family worked the same job, this was also a subtle allusion to the bar girls in Vietnam that American soldiers often frequented. In Vietnam, it was a well-known fact that “restaurants” were used as a cover for brothels.46 Subsequently, because Lee’s parents operate in “old Oriental” ways, it was plausible that these soldiers connected the “restaurants” he knew in Vietnam with the Lee’s business. Thereby, this (incorrectly) reaffirmed his assumption that China Lee was just like any other Asian prostitute they had encountered in the War. Still, returning to the point that Orientalism often included unnecessary details to appear credible, it’s objectively weird that this article that prefaced her nude centerfold that men would masturbate to and fantasize about mentioned her family at all. Her parents, nonetheless. 45 “China Doll.” 68. 46 Boczar, “Uneasy Allies: The Americanization of Sexual Polices in South Vietnam,” 216.

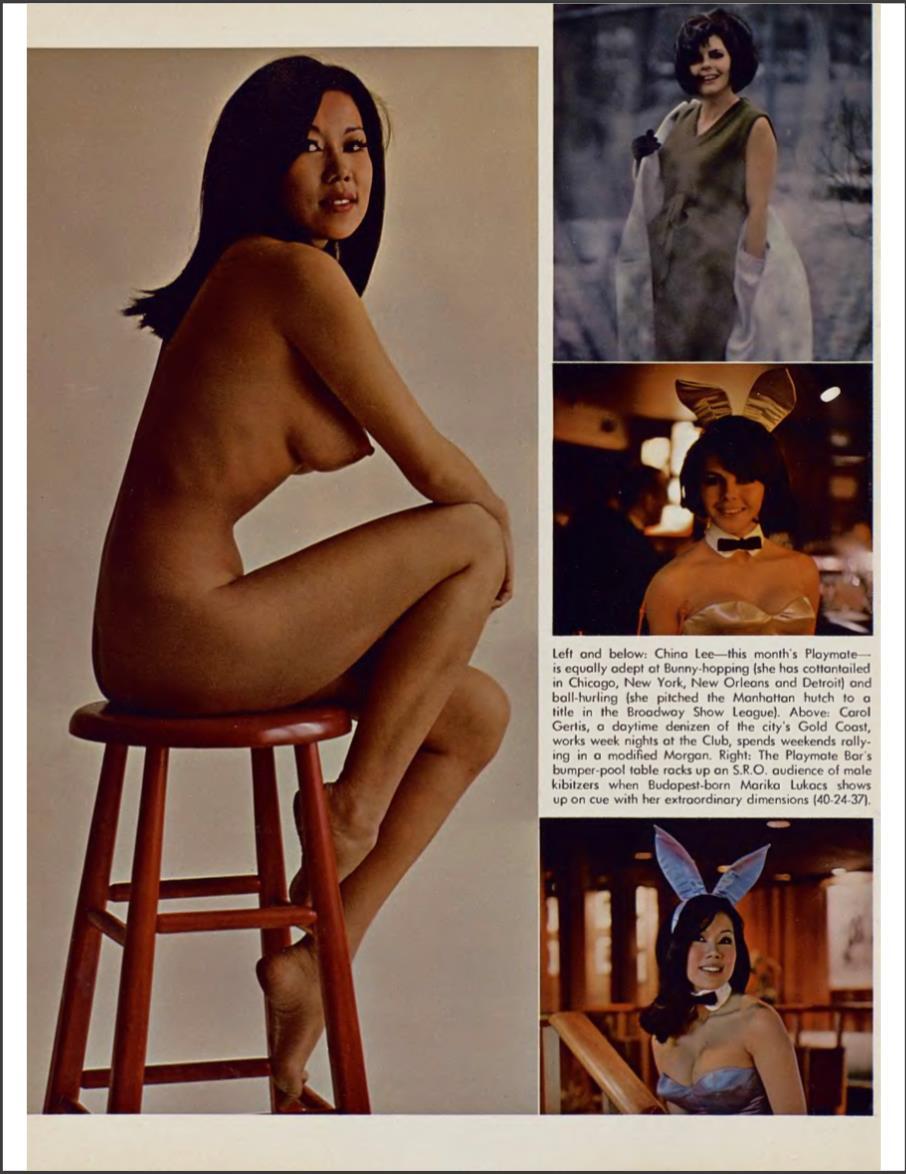

Then, later in the August 1964 issue of Playboy, China Lee emerged again in “The Bunnies of Chicago” feature (fig. 5) as the only nude model on the page. It’s kind of uncomfortable to look at. She looked out of place. But that’s what Playboy wanted their viewers to think. From her spread earlier, the reader learned that she came from an environment where “men [dominated] and females [were] forced into the background,”47 such that “for a Playmate like China Lee, rebellion meant taking her clothes off for a national men’s magazine.”48 So when men felt “wrong” for enjoying China Lee’s nudity, him and her shared a “dirty little secret.” This set of images brought back an exciting sense of upheaval on both sides. White men were still pressured to conform and settle down with a White wife (as interracial marriage had yet to be legalized) and she defied her family by posing nude and not working at the restaurant.49 That’s how the magazine “invited [viewers] to sexually identify with, yet morally distance himself from, his Oriental counterpart within the objectively inciting yet racially distancing space.”50 It maintained his perceived Western dominance (for HE is the one who needed the distance to save face) and her “Oriental inferiority.” In conclusion, Playboy cultivated a sense that Lee and the viewer both knew it was wrong to indulge in such (interracial) pleasures. However, this made her “Oriental” sexuality and life that much more tempting and within reach to Western audiences. And, that’s exactly the counterculture lifestyle Playboy promoted.

Playboy also sold this obtainable “Orient” and the forever foreigner stereotype in their August 1964 issue though advertisements, such as “Kanaka” (fig. 6), which capitalized on the new kitschy appreciation for Asian and Polynesian culture during the war.51 Interestingly, the

47 “China Doll,” 68. 48 Pitzulo, “The Pulchritudinous Playmates,” 61. 49 “China Doll,” 68. 50 Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 45. 51 Pitzulo, “The Pulchritudinous Playmates,” 60.

name “Kanaka” actually did specify a locale, even if the ad itself didn’t. Kanaka translated to “a person of Hawaiian descent” not some faraway exotic place the customer was let on to be. Just like when Playboy called China Lee “China Doll” and an “Oriental Charmer” despite her ethnicity clearly stated in her stage name, Kanaka substituted Hawaii for “islands” and “Polynesian” for what at this point was an American state. Symbolically, like China Lee and other Asian-Americans, no matter how “American” they may be, they would perpetually be exoticized and mythicized because of their Asian/Pacific Islander heritage. China Lee’s spread and ads like these made sure to keep the “Orient” distinct, yet conveniently at an arm’s reach, which maintained the mysticism and perpetuated the exotic stereotypes of the other China Lee in Playboy’s April 1965 Issue

China Lee made one more return to Playboy in April 1965 for their “Playmate Playoffs,” a competition in which three models vied for the title “Playmate of the Year.” As the first Chinese-American and woman-of-color, Lee’s name on the ballot may seem like a step towards recognition and representation, but Playboy’s sexually imperialistic ways did not change much from the year prior. For one, her name was written in a very subtle Wonton font, to communicate her quietly reserved stereotypical persona despite her famously talkative, outgoing, and social attitude. In contrast, the names of the two other White candidates were much livelier and louder and flamboyantly demonstrated her unique personality.

Then, on China Lee’s “campaign page,” she was quoted saying, “a vote for me would serve notice to the entire world that the popular image of the shy and retiring Oriental female is long overdue for a change.”52 However, given the two photos Posar took of China Lee (fig. 7), that stereotype was very much perpetuated. She didn’t want to be associated with being “shy,”

52 “Playmate Playoffs” in Playboy vol. 12, no. 4 (New York, NY: Playboy Press, 1965), 112.

but her reserved smile and the minimal lighting on her face in both images said otherwise. She was hidden, likely for Playboy to preserve that “long overdue” mystery of Asian/American women. And, her expression was seductive but not excitable. In the image on the left, she used the couch to coyly conceal her breast. And in the larger photograph to the right, her body was bashfully turned, to not give away her entire self. Even though China Lee was celebrated for being personable and her career in adult modeling was illustrative of her confidence, Playboy, once again, used her stereotypical “Asian-ness” to construct a more “palatable” narrative. Finally, China Lee had one final request: that her winning “would be to show every young Oriental girl how silly it is to hide her beauty for tradition’s sake,”53 which was ironic considering her face was enveloped by darkness. But to a larger point, China Lee said she wanted to use her fame and platform to elevate the self-esteem of young Asian women all over the world and show them that they were beautiful too. She had a point given Playboy’s and Western society’s historic obsession with blond-haired-blue-eyed models, the implied “inferior ugliness” was instilled into Asian/Americans like Lee. At any rate, China Lee had forgone her American nationality to highlight her Chinese heritage (though she did not particularly identity with it) in order to promote a legitimate, and unexpectedly wholesome, point. However, there was something unsettling here. Playboy’s main audience wasn’t young Asian/American females looking for role models; Playboy’s main message wasn’t necessarily for social justice. So, when Playboy conveyed her morals surrounded by her pornographic nudes, the delivery was off as though telling Asian/American women they were only beautiful if they posed naked for a world-wide gentlemen’s magazine. In other words, were of sexual use to Western men. Having known China Lee’s desire to redefine the Asian stereotype and having 53 “Playmate Playoffs,” 112.

read her wish, then finding out she wasn’t crowned “Playmate of the Year” also checked another box of Orientalist erotica: that her “nakedness was more pitied than censured.”54 One couldn’t help but feel sorry that she exposed her curves to express a virtuous objective in a not-sovirtuous competition presumably to tell young Asian/American women things she wished she was told growing up only to fall flat.

Conclusion

Playboy did not create the stereotype of submissive, sexually available Asian women that would be attributed to the centuries of justifying Western imperialism. However, Playboy did perpetuate it. The magazine used China Lee to bandwagon off the simultaneous hatred and lust for Asian/American women during the Vietnam War by constantly reminding the reader of her Chinese heritage and undermining her Western upbringing. Her spread was used to legitimize the “exotic Oriental” prejudice that penetrated every-day life for women of Asian descent, and her photographs operated as a proxy for American soldiers to feel masculine at the expense of said women. However, it’s hard to argue that Lee’s spread paved the way for progressive change and diversity. Since Playboy began in 1953, the publication would go on to only feature eight other Asian/American Playmates, each spread exhibiting similar, more grotesque, more flagrant symptoms of exoticism, Orientalism, and Western sexual imperialism of Asian/American women than the one before. Despite China Lee’s attempt to tackle these racist and sexist stereotypes, when Playboy purposefully stressed her Chinese heritage, the magazine only mainstreamed, and made obtainable, the “Mysterious Orient.” Lee was not a trailblazer, but rather a victim, for it seems like this outdated, age-old stereotype is not going anywhere.

54 Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” 44.