Gratitude in Action

A Jewish perspective on Thanksgiving

Rabbi Meets Doctor

A conversation about Torah and medicine

Healthier Kugel

A broccoli version of the Shabbos dish

Yiddishe Mama

12 facts about Rachel, the biblical matriarch

A Jewish perspective on Thanksgiving

Rabbi Meets Doctor

A conversation about Torah and medicine

Healthier Kugel

A broccoli version of the Shabbos dish

Yiddishe Mama

12 facts about Rachel, the biblical matriarch

Award-winning author

on

The Jewish outreach and education network of Southern Arizona 2443 E 4th Street, Tucson, AZ 85719

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Rabbi Yossie Shemtov

REBBETZIN

Chanie Shemtov

OUTREACH DIRECTOR

Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin

PROGRAM DIRECTOR

Feigie Ceitlin

Affiliates: Congregation Young Israel, Chabad at the University of Arizona, Chabad on River, Chabad of Oro Valley, Chabad of Sierra Vista, Chabad of Vail and Lamplighter Chabad Day School of Tucson

EDITOR

Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin

COPY EDITOR

Suzanne Cummins

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Zalman Abraham, Seymour Brody, Stuart H. Brody, Feigie Ceitlin, Faygie Levy Holt, Mendel Kalmenson, Menachem Posner, Mordechai Schmutter, Naftali Silberberg, Benjamin Weiss

PHOTOS

Unsplash.com

SPECIAL THANKS Chabad.org

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING

Phone: 520-881-7956 #12

Email: info@ChabadTucson.com

SUBSCRIPTION: ChabadTucson.com/SubscribePrint

Keeping Jewish is published in print periodically by Chabad Tucson and is distributed free in Tucson and Southern Arizona.

Chabad Tucson does not endorse the people, establishments, products or services reported about or advertised in Keeping Jewish unless specifically noted. The acceptance of advertising in Keeping Jewish does not constitute a recommendation, approval, or other representation of the quality of products or services, or the credibility of any claims made by advertisers, including, but not limited to, the kashrus of advertised food products. The use of any products or services advertised in Keeping Jewish is solely at the user’s risk and Chabad Tucson accepts no responsibility or liability in connection therewith.

Note: “G-d” and “L-rd” are written with a hyphen instead of an “o .” This is one way we accord reverence to the sacred divine name. This also reminds us that, even as we seek G-d, He transcends any human effort to describe His reality.

Recently, my 7-year-old son, Mendel, caught a few seconds of a doomsday political ad playing from one of our phones. “Did that really happen?” he wondered, his eyes wide with curiosity and mild alarm.

“No,” I replied, trying to navigate a minefield of truth, fiction, and “fake news” on a second-grade level. “It isn’t true.”

He blinked, baffled. “So … why did they lie?”

Ah, Mendel—how to explain smear campaigns, twisted truths, and political hyperbole in a single sentence? After all, it makes no sense that a cause or a candidate would hope to earn our trust by lying. And yet, that’s how it went down in the 2024 general election.

But Mendel has a point. From a young age, we teach our kids that lying is wrong. And indeed, Scripture has a lot to say about honesty. “He that practices deceit shall not dwell within my house; the speaker of lies shall have no place before my eyes,” King David says (Psalms 101:7).

Yet it’s interesting to note that there’s no straightforward commandment saying, “Thou shalt not lie.” We have “Do not murder,” “Do not steal,” and “Do not take revenge,” but lying isn’t directly labeled as a “Do Not.” (The instruction “You shall not lie, one man to his fellow” (Leviticus 19:11) is specifically about causing a financial loss through lying.)

Instead, the Torah tells us, “Distance

By Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin

yourself from falsehood” (Exodus 23:7).

Jewish sages explain that this choice of wording suggests more than just a prohibition against lying: it’s a call to build a life that naturally avoids deceit. Unlike a commandment not to lie, this imperative to distance ourselves from falsehood demands vigilance in many situations—not just in what we say but in what we don’t say— what we imply, omit, and “spin.” As the Yiddish saying suggests, a half-truth is a whole lie.

This ambiguous instruction also lends itself to mean that there are exceptions even to the honesty rule—times when an untruth can be told—like for peacekeeping purposes

or diplomacy, as the Talmud teaches. These, however, are the exception, not the rule.

It’s clear that cultivating honesty is considered a core trait, one essential for maintaining trust, integrity, and communal life. In fact, the Talmud compares lying to “warping the tongue”—a kind of ethical mutation with long-term effects.

Let’s get back to 2024. Imagine a campaign where candidates promoted their platforms without spin, exaggeration, or strategically vague soundbites. Maybe it’s idealistic, but imagine a world where politicians said, “Here’s what I hope to accomplish, here’s where I messed up before, and here’s what I still need to figure out.” In other words, imagine a world where candidates distanced themselves from falsehood and relied upon the truth of their opinions, plans, and platforms to promote themselves, allowing an educated electorate to decide for themselves what they prefer.

So why don’t they? For some, it might seem impossible to get ahead without stretching the truth. Yet honesty—like humility and patience—is a quality that requires longterm cultivation, whether in our kids, in ourselves, or, maybe one day, even in our politicians. In the meantime, I’ll be here, teaching Mendel to tell the truth (and reminding myself to do the same), while he continues to question why anyone would do otherwise.

- Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin is the Outreach Director of Chabad Tucson, the Jewish network of Southern Arizona

One of the 251 hostages taken by Hamas to Gaza on October 7, 2023, was Sasha Trufanov, an engineer of Annapurna Labs, a company owned by Amazon. com Inc. A month after Sasha was taken hostage, a computer chip that he worked on debuted at the Re:Invent conference of Amazon Web Services (AWS) in Las Vegas. Sasha’s missing presence and plight went unannounced.

A year later, Dr. Ruba Borno, a senior Vice President at AWS, invited people to their next conference, wearing a necklace with a map of the entirety of the Holy Land covered by a Palestinian flag and the words “From the River to the Sea Palestine” written in Arabic. Implicit in the slogan, of course, are genocidal designs against the 7.2 million Jews living in Israel.

The video has since been scrubbed from Amazon’s social media without any comment. But Jews in the tech industry say it should never have appeared to begin with.

“This was such a frustrating experience. These videos don’t just appear online, especially for AWS’s biggest event,” one Amazon insider said. “There are so many steps that could have flagged it. There is ordinarily great sensitivity around avoiding political statements. Seeing that video was just a horrible way to go into Yom Kippur.”

Amazon has internal employee messaging boards, including Wiki pages. “Some employees created a wiki page that was labeled ‘the situation in Palestine,’” or something like that, reports M., an Amazon employee. They used the Wiki page, she says, to accuse Israel of apartheid, genocide, and their hope that “this may be the moment Palestinians get their freedom.”

While Amazon did do an investigation of the page, M. says, the page remains

By Faygie Levy Holt - Chabad.org

up, and the company’s findings were not shared with its employees.

An Amazon spokesperson told Chabad. org, “We don’t tolerate any kind of discrimination or harassment, and when we learn of potentially inappropriate behavior, we investigate it with all the tools available to us and take action if we find that someone has violated our policies.”

Insiders point out that Amazon obviously did not see a problem with accusations that Israel is committing genocide. Others point out that Amazon is not the only company turning a blind eye to antisemitic language in the corporate environment.

In an incident that made headlines in January, “Free Palestine Kill All Jews” was seen scribbled in Google’s office in New York City. It prompted a number of

employees at major tech companies to report other disturbing incidents they feel have gone on with management failing to respond to the problems.

A Google employee recounted an incident in November when he arrived for work and went to the kitchen to grab a snack. On a whiteboard where people had drawn flags for the countries where employees are from, the Israeli flag had been erased and replaced with a “Palestinian flag with hearts.”

During a protest outside Google’s London office, a Jewish staffer was shoved by a pro-Palestinian Google employee. “I was horrified,” the Jewish Google employee shares. “At that point, I was banging on the table and begging leadership to send out some kind of statement that people need to leave politics behind in the workplace.” While no memo was issued, the

Jewish employee says the man who did the shoving was fired.

At Amazon, the silence has been deafening as Sasha Trufanov remains among the 101 people still being held hostage.

“I am not aware of any public statements about Sasha,” says a former Amazon employee who also asked to remain anonymous. “I’ve spoken to Jewish colleagues and non-Jewish colleagues I know who are supportive of Israel, and in some cases, these colleagues aren’t aware that an Amazon subsidiary employee is among the hostages.”

Jewish tech workers are not all sitting idly by ignoring what is going on around them. Many are reaching out to other Jews similarly situated.

This past March, a three-day trip/solidarity mission to Israel was organized jointly by Chabad’s Tech Tribe and various Employee Resource Groups. It was both uplifting and affirming.

The participants met counterparts working in the Israeli tech sector. They also bore witness to the horror and destruction suffered by Israelis along the Gaza border.

One of the most meaningful moments for the participants was meeting Trufanov’s mother, Elena Trufanov, and his girlfriend, Sapir Cohen. They had both been kidnapped by Palestinian terrorists before being released during the exchanges late last year. Trufanov’s father, Vitaly, was murdered during the initial attack.

Sapir Cohen has spoken since her release to bring awareness about the experience of the hostages and the continued plight of hostages like Sasha and others still in Hamas captivity. Perhaps her story will be on one of the Wiki pages at Amazon or Google one day.

On October 30, 2024, I traveled to Washington, DC, to receive the prestigious Grateful American Book Prize at a ceremony at the Smithsonian Art Museum for my recent work, Humphrey and Me.

The “Humphrey” in the title is, in fact, Hubert Humphrey, a distinguished U.S. Senator from Minnesota (1949-1964, 1971-1978), the 38th Vice President of the United States (1965-1969), and perhaps most notably, the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for president in the 1968 election.

By Stuart H. Brody

The “me” in the title is actually me. The book is based on my relationship with Hubert Humphrey as a fifteen-year-old Jewish boy growing up in a suburb of New York City.

The book is not a memoir but rather a work of historical fiction. I rendered it a fictional account because I wished to dramatize events to accentuate the meaning of the stormy relationship between a young man and his famous mentor: that despite setbacks, we must never conclude that our limitations are permanent.

In the book, as in real life, Humphrey lost

the presidency because he was excessively loyal to his president and patron, Lyndon B. Johnson. Despite his disagreement with Johnson’s policy in the Vietnam War, he secreted his personal sentiments and advocated enthusiastically for a stance he did not support. His failure has often been characterized as “loyalty to a fault.” In other words, even a virtue, when deprived of context and pushed to an extreme, can yield a breach of integrity.

The young boy -- the protagonist in this story-- was perplexed by Humphrey’s failure and broke with him, declaring

him a coward. The young man’s moral impulse to identify and reject Humphrey’s faulty judgment was itself extreme, lacking understanding and empathy for Humphrey’s excruciating moral choices. The characters in this novel, like most of us, try to push through the fog of our limitations to find a way to understand, forgive, and empathize.

Alignment with who we know ourselves to be is a deeply psychological journey, not an exercise in logic, and its course must run through unwieldy emotions. To state this in another way, human nature lies most

compellingly in our capacity to understand our own failings and forgive the flaws of others.

I think this message underscores the powerful themes of our recent holiday season of the month of Tishrei. Loss, error, and poor judgment are not the defining aspects of our lives; rather, reviewing how we missed the mark enables us to reform our lives and enrich them - or, in other words - teshuvah (return to G-d or repentance). Even Humphrey’s loss of the presidency to Richard Nixon—a divisive and controversial figure—does not define who Hubert Humphrey is. What defines him is the integrity with which he resumed his life of contribution after coming to grips with his limitations.

Similarly, the boy who reacted volcanically to what he viewed as the cowardice of his hero embarks on the painful process of sifting through his emotions and learns to substitute understanding and empathy for judgment and condemnation.

These themes are central to the High Holy Day experience. These holidays, taken together, provide the arc of teshuvah: we return to the place where we took an errant path, leading away from who we know ourselves to be or who we would like to become. And as rigorous as we must be with ourselves in making teshuvah on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, it gives way to Sukkot, a time to affirm ourselves, grant ourselves credit for the efforts we have made and appreciate the many ways we have aligned ourselves with G-d’s direction.

Teshuvah is no less important for a nation than for an individual. Without questioning our errors, and for that matter even our certainties, we can never truly be certain nor disposed to discern the meaning that G-d has for us; without teshuvah, we double down on our limitations, weaponize them, blame others, and create political

movements out of bitterness.

Our nations, both the nation of Israel and the nation of the United States, also face the challenge of teshuvah. In Israel, we may not know and may never know whether we actually “won” or “lost” the war with our enemies; the criteria will always be shifting as people clamor to make sense of the staggering loss of life and excruciating strategic decisions.

And although a winner may eventually be declared in our national elections on November 5, people will contest the result. We can be sure that the arguments that characterize the national debate following the election will be no different than the one preceding it: full of blame, recrimination, and denunciation, rather than returning to the place where we missed the mark, lost our way, and took a wrong turn on preserving our national patrimony.

As I prepare for a lengthy trip to Israel in January of 2025, perhaps a permanent one culminating in Aliyah, I plan to devote myself to studying. Familiarity with prayer

is long overdue. Throughout my life, I have straddled the fence between mere tribal affiliation—I volunteered to serve during the Yom Kippur War in 1973—and tefillah as a pathway to personal connection to G-d.

I have been propelled along this path by the patience and wisdom of Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin of Chabad Tucson, who has portrayed the awesome and elegant structure of tefillah to me. I have learned through this devotion that tefillah provides the spiritual fuel to make the return journey—teshuvah—to revisit the events in my life; not to declare them wins or losses, not to construct a narrative of justification, not even to reinterpret my mistakes and forgive myself. Instead, I have worked to train myself to penetrate the mystery of my uncertainties and to know that the work I do now, perhaps for the first time, is done with G-d at my side.

--Stuart H. Brody, an adjunct instructor at the University of Arizona and Senior Scholar at the Institute for Ethics in Public Life at the State University of New York, is the author of The Law of Small Things: Creating a Habit of Integrity in a Culture of Mistrust, and Humphrey and Me, recent winner of the Grateful American Book Prize. 5

All about the biblical matriarch whose yartzeit is this month

By Menachem Posner

1. Rachel is one of the four matriarchs Along with Sarah (wife of Abraham), Rebecca (wife of Isaac), and Leah (her sister and fellow wife of Jacob), Rachel is one of the four mothers of the Jewish people.

2. Her name means “sheep”

In Hebrew, the name Rachel means “sheep,” associated with her lovable, serene nature. And it is perhaps no accident that we read of how she would watch her father’s flocks.

3. The Bible describes her beauty Scripture sparsely depicts the physical appearance and features of the people whose stories are told. One of the few exceptions is Rachel, who we are told “had beautiful features and a beautiful complexion.”

4. She was the beloved wife of Jacob When Jacob came to her hometown of Padan Aram to search for a wife, he helped her water her father’s flock, and the two felt an immediate deep connection. Jacob so wished to marry Rachel that the seven years he had to work for her father, Laban, to earn her hand in marriage “were like a few days in his eyes.”

5. She sacrificed for her sister Laban deceptively decided to place his elder daughter Leah under the bridal canopy. Suspecting that Laban might pull a fast one, Jacob gave Rachel a prearranged password to identify herself. However, not wanting her sister to be shamed in public, Rachel gave Leah the secret sign and watched as she married the man of her dreams. After Jacob discovered the ruse, he agreed to work for seven more years if Laban would allow him to marry Rachel a week later.

6. She is associated with speech

Chassidic teachings explain that Leah’s soul stemmed from the world of thought, while Rachel’s soul was from the world of speech. Leah was introspective, a master of meditation and internal communication, while Rachel was charismatic and appealed to others. Together, they laid the foundation for our nation. Rachel instilled within us the strength to exude a powerful and far-reaching aura of influence. Leah gave us the strength to tug at our soul strings and talk to G-d with integrity.

7. She suffered from infertility

Soon after her marriage, Leah began to produce sons (she had six in total). Even Bilhah and Zilpah, their maids, had two

sons each. But Rachel’s “closed womb” caused her so much grief that she told her husband that to live without children was akin to death. Her pain was eased (but not erased) when she was blessed with a son, whom she named Yosef (Joseph), meaning “he shall add,” expressing her wish for yet another son.

8. She “stole” her father’s idols

As Jacob prepared to move back to his native Canaan (the future Land of Israel) with his wives and children, Rachel stole her father’s teraphim (idols) in a final effort to wean him from idol worship. When Laban confronted Jacob about the missing figurines, Jacob innocently declared that whoever had taken them should die.

9. She died in childbirth and was buried on the roadside

Jacob’s ill-spoken words came true, and Rachel died shortly after that while giving birth to her second son, Benjamin. Jacob buried her on the road near Bethlehem on the way to Efrat. She is the only matriarch not buried alongside the other matriarchs and their respective husbands in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron.

10. She cries for her long-lost children

Rachel, buried alone by the roadside, stands as the enduring Jewish mother, watching over her exiled children. The prophet Jeremiah describes her lament: “A voice is heard on high... Rachel weeping for her children, refusing comfort.” G-d reassures her: “Hold back your tears... they shall return from the enemy’s land... there is hope, and the children will return.” The sages envision her pleading with G-d, evoking her compassion for her sister, and ultimately, G-d agrees to return the exiles in response to Rachel’s heartfelt plea.

11. She is referred to as “Mamma Rochel”

Like the other matriarchs, she can be referred to as Rachel Immenu (Rachel Our Mother), even though she is technically only the mother of two out of the 12 tribes of Israel. In Yiddish, she is affectionately called Mamma Rochel, reflective of her special place in the hearts of the Jewish people.

12. Her passing is celebrated on 11 Cheshvan

Tradition places the anniversary of the passing of Rachel on the 11th of Cheshvan (Tuesday, November 12, 2024). Thousands flock to her tomb near Bethlehem, just south of Jerusalem, to pray, evoking her sacrifice and suffering and beseeching G-d to have mercy in her merit.

return.”

and

By Naftali Silberberg

We, the citizens of America, are a thankful lot. Our calendar is dotted with days when we express our gratitude to various individuals and entities.

On Veterans Day, we thank the Armed Forces members for their dedicated service. On Memorial Day, we show our gratitude to those courageous men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice while defending our liberties and democratic lifestyle. On

Labor Day, we express our appreciation to the industrious American workforce, the people who keep the wheels of our economy turning. On other selected days, we pause to thank different historic individuals who have made valuable contributions to our nation.

And then there is Thanksgiving. The day when we thank G-d for enabling all the above—and for all else He does for us. There is no doubt that this great country’s historically unprecedented success and prosperity is due to the fact that its Founding Fathers believed that there is a Supreme Being who provides and cares for every creature. They understood that since G-d sustains and gives life to every being, it follows that every being has certain “inalienable rights” upon which no government can impinge.

These strong morals upon which our republic was founded express themselves to this day in American life. Looking at the dollar bill and seeing “In God We Trust” reminds us that our history is built upon and credits this motto of faith.

As Jewish citizens of this land, we always look to the Torah for a deeper perspective and additional insight. What light does the Torah shed on the wonderful trait of thankfulness?

Actually, there is one particular mitzvah that is completely devoted to expressing gratitude—the mitzvah of bikkurim (Deuteronomy 26:1–12). During the Temple era, every farmer was commanded to bring the first fruits that ripened in his orchard to Jerusalem. There, he would recite a passage thanking G-d for the Land and its bountiful harvest, and the fruits were given

to the kohanim (priests). The Midrash extols the great virtue of this mitzvah, going so far as to say that the Land of Israel was given to the Jews as a reward for the mitzvah of bikkurim!

While the importance of expressing deserved gratitude is self-evident, it is difficult to comprehend the special significance of bikkurim. After all, every day, according to Jewish tradition, is jampacked with “thank you’s.”

The first words we utter when waking in the morning express our thanks to G-d for returning our souls to our bodies. Three times daily during the course of prayer, we thank G-d for everything imaginable. Before and after eating, we thank G-d for the food. There is even a blessing recited upon exiting the restroom, thanking G-d for normal bodily function!

With all the thanking that occurs on a daily basis, one might question the need for a specific mitzvah to emphasize the point.

The Rebbe points out one obvious difference between bikkurim and all the other ways we thank G-d: bikkurim involves more than just words—it requires a commitment. The gratitude must express itself in deeds. Bikkurim implies that our thankfulness to G-d cannot remain in the realm of emotions, thoughts, or even speech but must also move us to action. While the mitzvah of bikkurim in its plainest sense is not practical today, its lesson is timeless. Our gratitude to G-d must express itself in the actions of our daily life. Giving back the “first of our fruit,” the choicest share of our bounty, is the appropriate way to thank G-d for giving us all our fruit.

By Feigie Ceitlin

When you think of kugel, you probably imagine a delicious, carb-rich dish. Traditional kugel recipes often feature noodles or potatoes with a generous amount of oil. This broccoli kugel is a lighter, healthier twist, but it’s still a family favorite—especially among the adults!

It’s perfect as a warm dish on a chilly Friday night and can be enjoyed cold on Shabbos day as well.

INGREDIENTS:

24 oz frozen broccoli

1 cup non-dairy milk

4 tablespoons margarine or non-dairy butter substitute

1.5 tablespoons flour

2 tablespoons onion soup mix

2 tablespoons mayo

2 eggs

1/2 teaspoon pepper

1/2 teaspoon garlic powder

Salt, to taste

Crushed cornflakes

DIRECTIONS:

1. In a pot, steam the frozen broccoli with

the non-dairy milk and margarine until the broccoli is very soft.

2. Drain the broccoli mixture well, then add the flour, onion soup mix, mayo, eggs, pepper, garlic powder, and salt to taste.

3. Mix everything together. For a smoother consistency, mash all the ingredients together.

4. Pour the mixture into a greased 8x8inch pan, sprinkle the cornflake crumbs on top, and bake at 350°F for 45 minutes.

Enjoy!

* The Blessing on Vegetables

Baruch atah A-donay, Elo-heinu Melech Ha’Olam borei pri ha-adamah.

Blessed are You, L-rd our G-d, King of the universe who creates the fruit of the earth.

— Rebbetzin Feigie Ceitlin is the program director of Chabad Tucson and head of school of Lamplighter Chabad Day School.

ABR, CRS, GRI

By Benjamin Weiss

Over the holiday of Sukkos, a conversation was had between Rabbi Yossie Shemtov, Regional Director of Chabad Tucson, and Dr. Steven Wool, a primary care physician since 1985 and principal of Personalized HealthCare of Arizona.

The following are excerpts from their conversation.

Rabbi Shemtov: As a rabbi, we usually don’t want doctors stepping onto rabbinic matters. Similarly, doctors do not want rabbis to interfere with medical issues. Each has a distinct role. But in today’s world, I think it’s essential to explore the Torah’s perspective on medicine while leaving science to doctors.

Dr. Wool: Exactly. Torah’s guidance on

health isn’t about the science—that’s for doctors.

Rabbi Shemtov: In the Torah, there’s a commandment to listen to rabbis as “they instruct you” (Deuteronomy 17:10), but the Rebbe said that instruction also applied to listening to doctors, making that a mitzvah.

Dr. Wool: I think it is essential to see every interaction—doctor or rabbi—as a mitzvah. Medicine today often misses this personal aspect, focusing on efficiency. But true healing requires time, connection, and care. I think the emotional aspect of medicine is deeply spiritual.

Rabbi Shemtov: When my wife was pregnant, she needed a shoulder operation.

a this But connection, of operation.

They gave her the option of general or local anesthesia. We consulted with a senior rabbi who agreed to weigh in only because the doctor was OK with both options. He then favored local anesthesia based on the baby’s safety.

Dr. Wool: That’s a beautiful example of the Torah guiding medical decisions in partnership.

Rabbi Shemtov: A person once wrote to the Rebbe mentioning that he had researched his illness. The Rebbe advised him to focus on Torah study instead, saying the doctor should handle the research. What do you think of patients “self-diagnosing”?

Dr. Wool: Actually, I think it is positive— education empowers people. After all, “doctor” and “rabbi” both mean “teacher.” An ethical doctor is always learning, just like an ethical rabbi. We guide, inform, and help patients make their own informed choices. Teaching is central to both professions, and good medicine is also about listening and informing.

Rabbi Shemtov: Let’s talk about what is happening on the horizon. Advancements like gene therapy for leukemia now provide treatments without chemotherapy. There is a profound sense that medicine is on a great trajectory of discovery.

Dr. Wool: That’s the beauty of medicine—it is always evolving, offering these “gifts” from G-d. As Einstein said, studying nature is akin to religion; we’re discovering answers already in creation.

Rabbi Shemtov: Have you ever advised a patient who instinctively understood their condition in ways you could not have diagnosed without their insights?

Dr. Wool: Absolutely. Those moments remind me that our work often channels something greater than ourselves. But we’re touching on another point: patients need to listen to doctors, and doctors need to listen to patients. Both need to communicate openly. Have you read the short story by Sholem Aleichem titled “At the Doctor”? It captures the essence of doctor-patient interactions. It tells of a

patient who just wants the doctor to listen to him. It reminds us that not every doctor allows their patients to speak, but there are good doctors who genuinely care.

Rabbi Shemtov: When you treat patients, is it always according to the guidelines in the “book,” or is intuition also involved?

Dr. Wool: Oh my gosh, intuition is essential and happens all the time. That’s what we often contend with insurance companies about. Insurance companies have a rigid approach, but sometimes, you just know something needs to be done based on clues under the surface.

Rabbi Shemtov: It may be more difficult to defend medical intuition today than in the past, given the insurance companies’ demands. I was your patient 40 years ago, and it was a much more personal relationship.

Dr. Wool: Today, the focus has shifted to a more technical, complex system, especially with the introduction of primary care physicians as gatekeepers. That being said, a patient’s doctor can connect to the patient as an individual and be deeply involved in their wellbeing.

Rabbi Shemtov: In the past, it was just you and me. Now, the doctor often doesn’t know the patient personally. In Talmudic law, if someone is injured and needs medical care, the courts require fair payment to the doctor, suggesting that “a doctor who charges nothing is worth nothing.” However, this ideal doctor-patient relationship reflects a world where the doctor held authority, but today, corporate interests often dictate medical practices.

Dr. Wool: No question about that. Two weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal had an interesting article about how private equity enters healthcare. There are a lot of good doctors, but many of the people involved in care today are driven by either insurance companies or corporate-mandated efficiencies to cut costs.

Rabbi Shemtov: I read that. When you lose the personal touch and turn it into a financial transaction, it becomes

dangerous. Everyone talks about healthcare for all, Obamacare, insurance. But most people in the country don’t have a private doctor. Similarly, they often don’t feel they need a religious leader or counselor. It’s the same idea.

Dr. Wool: Right. Imagine how much healthier our community would be if people could have a personal relationship with their doctor and rabbi.

Rabbi Shemtov: What are your thoughts about Zoom Healthcare? Virtual care feels impersonal.

Dr. Wool: True. Zoom Healthcare works for some things, but it alone is insufficient for creating a personal connection.

Rabbi Shemtov: I fear that the lack of personal connection with physicians is also being driven by financial interests. I’ve read about private equity buying medical practices, and it’s alarming. It creates a situation where the practice owners care only about profits, not quality of care.

Dr. Wool: Your reason for being alarmed has a basis. And that’s where the real issue lies. We need to find a way to shift focus back to the personal aspects of care and trust. That’s true in both healthcare and religion. Just look at the challenges synagogues face in attracting people.

Rabbi Shemtov: Some survive because members left money to foundations, but that’s not a sustainable model. A synagogue ultimately cannot survive without people connected to its mission any more than

a medical practice can survive without serving patients.

Dr. Wool: Maybe we could work together to bring the personal connection back for both rabbi and doctor. We could organize health fairs at synagogues to promote health awareness and preventative care using the expertise of Jewish doctors. Imagine a minyan where there’s a blood pressure cuff available, or classes on healthy living.

Rabbi Shemtov: Yes, and if you lose weight, you could earn an aliyah!

Dr. Wool: Right! People enjoy the combination of spiritual and medical support in the same environment.

Rabbi Shemtov: In some religious communities, doctors and rabbis may be considered rivals, but that shouldn’t be the case.

Dr. Wool: We do need to emphasize collaboration.

Rabbi Shemtov: Hopefully, both of us will find a future with personal, caring relationships with our constituents!

Personalized Healthcare of Arizona 5210 E Farness Drive, Tucson, AZ 85712 520-525-9433

frontoffice@phcofaz.com www.phcofaz.com

Judaism has a very strange relationship with the pig. Technically, it is no less unkosher than any other non-kosher food. Yet, in Rabbinic literature and in the popular Jewish imagination, it has come to epitomize everything non-kosher. Even mentioning the pig by name was considered so repugnant to our Sages that it was simply referred to as “davar acher— the other thing.”

Even more strange is the fact that the letters that make up its name are encoded within a prophetically kosher future. According to its etymological root, chazir, the name for pig, means “to return”—“For our Sages teach us that it will return to become permitted in the future.”

That’s right—the time will come when pork will become kosher. The pig is, therefore, named not after its past or present status, but after its future state of being.

This begs the obvious question: How will the quintessential nemesis of everything kosher eventually become kosher itself? To answer this question, we first need to understand what makes an animal kosher in the first place.

The Torah distinguishes kosher mammals from others through two specifications: a kosher mammal must chew its cud and have split hooves. This disqualifies all mammals that possess neither or even only one of these characteristics.

The pig is explicitly mentioned in the Torah as the only mammal that has split hooves but does not chew its cud. It therefore appears kosher externally, but its internal reality renders it unkosher.

The Sages see in the pig’s biology a symbolic form of deceptive posturing. The pig tricks others into thinking that it is kosher by displaying its visibly kosher

By Mendel Kalmenson and Zalman Abraham

feature, its split hooves, without possessing the requisite inner feature, chewing its cud to back it up.

The pig, at present, thus represents a twofaced character—what you see is not what you get.

The Midrash describes Esau as having embodied this piggish nature. He would present himself to his father, Isaac, as pious and G-d-fearing, despite the fact that he was actively engaged in immoral behavior and idolatrous practices. He was, in effect, merely playing a role to satisfy

what he thought Isaac wanted to see from him.

Transparency is a central value in Judaism. The medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides lists misrepresenting oneself to others as a Torah prohibition, a form of theft—“stealing people’s minds”—even when it causes no monetary loss. In R. Gamliel’s yeshivah in the city of Yavneh, any student whose internal character and external conduct did not match was not permitted to enter the study hall. Even more strongly, the Talmud declares that any Torah scholar whose outward

expression of righteousness is insincere “should not be considered a Torah scholar.”

However, all hope is not lost for the pig. Reflecting the purpose of creation, which is to reveal the currently concealed presence of G-d within all, the future messianic age will be an age of transparency when whatever is concealed on the inside will be exposed, and the truth will become ubiquitous. No longer will it be possible to harbor insincere or hypocritical thoughts or behaviors.

Indeed, we are already seeing considerable advances in this area. Thanks in part to the explosion of public information, transparency has become a baseline value that we now expect from financial firms, companies, and elected officials. It is becoming increasingly harder to pretend that you are something other than what you truly are.

Adapting to this change in the world, rabbinical sources teach that the anatomy of the pig will evolve accordingly so that its inner and outer features are aligned, and, as a result, it will become kosher. The pig not chewing its cud will no longer be a source of deception - it will simply be a fact.

In the final analysis, the very animal that is the archetypal antithesis of all things kosher serves as the ultimate reminder that being kosher, rather than merely eating kosher, is a matter of character, not just consumption.

The Big Idea: In Jewish thought, it is not enough to eat kosher, one must also strive to be kosher in all that one does.

—An excerpt from People of the Word, by Mendel Kalmenson and Zalman Abraham, exploring 50 key Hebrew words that have been mistranslated and misunderstood for centuries.

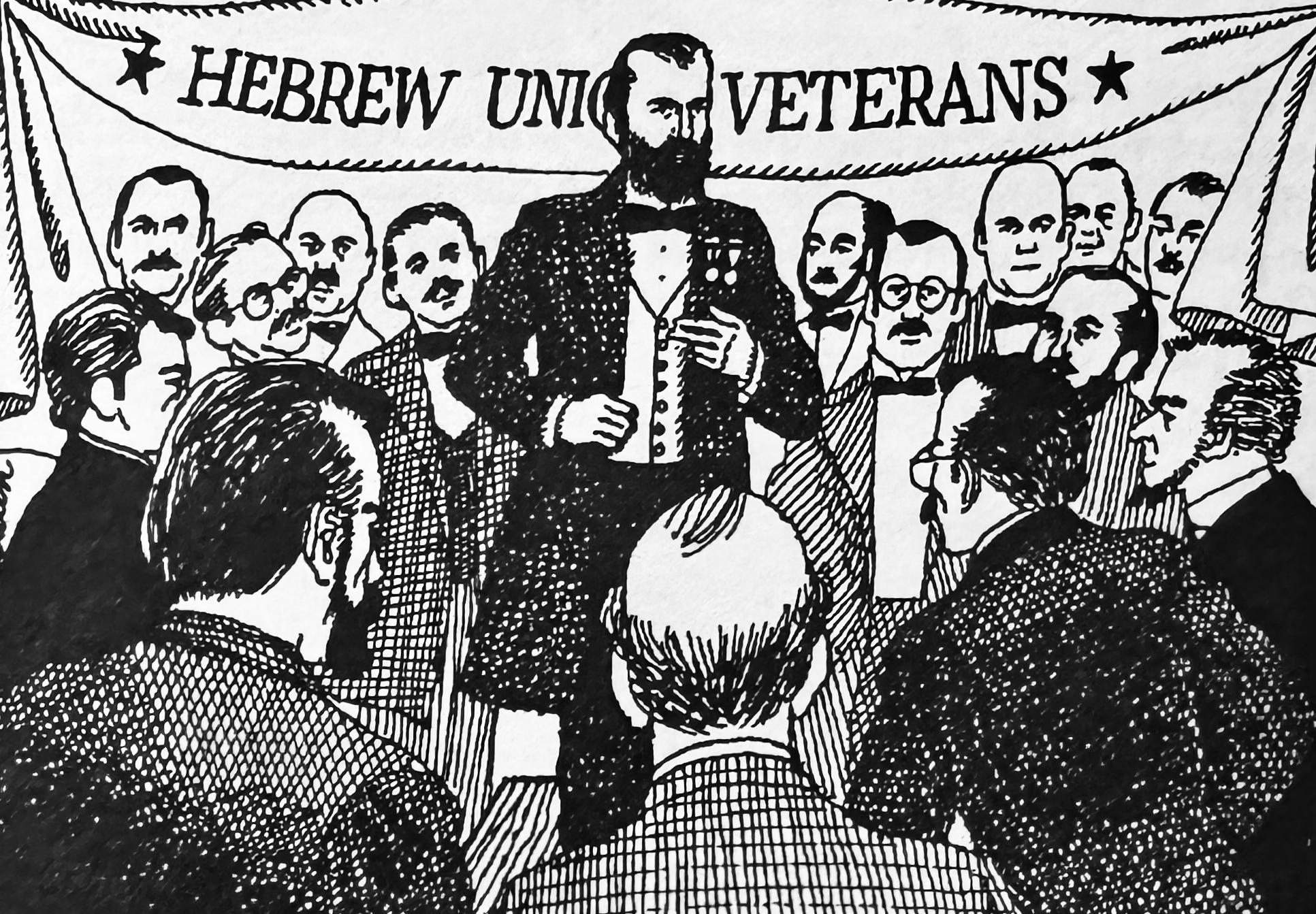

By Seymour Brody

When Mark Twain -along with the magazines Harper’s Weekly and North American Review- wrote that American Jews didn’t serve and fight in the Civil War, 78 Jewish veterans of the Union Army stood up to refute these lies.

Meeting in New York City’s Lexington Opera House on March 15, 1896, they organized the Hebrew Union Veterans, the precursor group to the Jewish War Veterans (JWV) of the USA.

These veterans had a right to be angry. More than 6,000 Jews served in the Grand Army of the Republic, with many of them being killed or wounded. Six Jews were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor; many others received various decorations and medals. A year later, Mark Twain apologized to the veterans for his antisemitic remarks.

The 78 Civil War veterans who met that day in 1896 made enduring and profound commitments. They pledged to maintain a steadfast allegiance to the United States; to combat antisemitism and to combat bigotry wherever it originated and whatever the target; to uphold the fair name of the Jew and fight his battles wherever unjustly assailed; to assist such comrades and their families as might stand in need of help; to gather and preserve the records of patriotic service performed by men of Jewish faith; and to honor the memories and shield from neglect the graves of heroic Jewish veterans.

Major accomplishments of the group include organizing a boycott of German goods (1933), effectively campaigning for the G.I. Bill (1944), and conducting a

successful drive to supply blood for our soldiers during the Korean War (1951).

It was the only national veterans’ organization that joined Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historic march on Washington (1963). They also spearheaded a drive in response to President Ronald Reagan’s 1985 visit to a German military cemetery in Bitburg, in which some Nazis are buried.

The Jewish War Veterans Museum in Washington, D.C., is the only museum in the country that houses the artifacts, memorabilia, and records of Jewish men and women who served and fought in the wars of the United States from Colonial times to the present.

The Jewish War Veterans of the USA is one of the oldest active veterans organizations in the country and the only active Jewish organization that has a Congressional charter. Over the years, its principles have been expanded to include support for Israel, Jewish Boy Scouts and Eagles, college scholarships, Soviet Jewry, and community collaboration for common goals and causes.

Thanks to the decisiveness of those 78 Jewish Civil War Veterans in 1896, the Jewish War Veterans organization continues to be visible and vocal so that nobody will ever again question whether Jews fought for our country.

- Originally published in Jewish Heroes & Heroines of America: 150 True Stories of American Jewish Heroism (Frederick Fell Publishers, Inc.)

By Mordechai Schmutter

Stiff necks are a real pain in the neck, and they always strike without warning. They often start while you’re sleeping – and before you can turn around, they’re upon you! And then you can’t turn around at all.

I recently read that at any given point, one out of twenty people has a stiff neck. So if you’re ever in a room with a whole bunch of people, look around. If you can’t, it’s you.

The worst part of having a stiff neck is that you can’t move your head. Even if you want to do something as simple as look at someone, you have to turn your whole body. You think you’re being all casual about it, but then the person you are looking at says, “Do you have a stiff neck?”

And this is not to mention how stiff necks can really affect your performance at your job, especially if you’re a bus driver, an air traffic controller, an aerobics instructor, a violinist, or anyone who swims for a living.

Also, sometimes you want to silently tell someone, “No,” but you can’t turn your head, so you have to do it with your entire body from the waist up. And you get the response, “Why are you dancing?”

I think if you’re a mother, a stiff neck isn’t as big of a deal because you have eyes in the back of your head. My wife does. I try to sneak food from the kitchen when she’s in the dining room, and she asks, “What are you noshing on?”

“How do you know I’m noshing on anything?”

“I have eyes in the back of my head.”

“If you have eyes in the back of your head, how do you not see what I’m noshing?”

So apparently, my wife has eyes in the back of her head, but they need glasses.

Sure, there are a lot of advice articles out there, but it’s not easy to tell which ones might help.

For example, one article I read said (and I am not making this up), “TIP #6 –Massage. STEP 1: Grasp your neck with your thumb on one side and your fingers on the other.”

Wait. Which two sides are we talking about? Care to be more specific? Am I

strangling myself here?

“STEP 2: Knead your neck by gently squeezing for 1-2 minutes.”

Yup.

I didn’t put a lot of stock in that article anyway because it was called “9 Home Remedies for a Stiff Neck,” and #8 was to call a chiropractor.

Plus, a lot of the advice these articles give seems contradictory. For example, a bunch of them said to “Apply heat and cold.” Won’t they cancel each other out? Can I just apply nothing?

And public opinion doesn’t help that much either. Whenever people hear that you have a stiff neck, they’re very quick to point out that you probably slept wrong. So I guess the best idea is to go back to bed and try again until you get it right. You never know.

The problem is that when you’re sleeping, you’re unconscious, so you have no idea that you’re sleeping wrong until you get up and you’re like, “Was that wrong? I was

like that for six hours!”

I have no idea if I’m sleeping wrong. I could be sleeping wrong every night. No one really ever taught me how to sleep. I went to school for like twenty years, and as far as I can tell, there’s no class for that. In fact, if you fall asleep in class, the teacher gets all judgy about it. He never says, “Oh, you’re doing it wrong; let me show you.” There should be official sleeping classes. What are you paying all that dorm money for? Just so your kid can take naps during lunch?

And anyway, if you take a nap during class, it’s on your arm, and you never wake up from that with a stiff neck anyway. At worst, you wake up with a dead arm and a deep red impression of your shirt button. So, I was never really taught how to sleep. I was left to figure it out on my own, and now I get it wrong and get stiff necks.

Maybe the secret to avoiding stiff necks is the same as avoiding anything painful in life: just keep turning a blind eye to it. As long as you can actually turn, that is.

By Menachem Posner

1. What’s the full name of this month?

A. Menachem-Cheshvan

B. Cheshvan-Sheni

C. Mar-Cheshvan

D. William T. Cheshvan

2. Which of the following is true?

A. Jews of Yemen start praying for rain on Cheshvan 7

B. Farmers (but not city folk) start praying for rain on Cheshvan 7

C. Jews in Israel start praying for rain on Cheshvan 7

D. Jews in the Diaspora start praying for rain on Cheshvan 7

3. Which holiday occurs in Cheshvan?

A. Sukkot

B. Simchat Torah

C. Chanukah

D. None of the above

4. Which famous Jewish mother’s passing is commemorated this month?

A. Rachel our Matriarch

B. Sarah, mother of Isaac

C. Hagit, mother of Salvo and Fortuna

D. Yetta, who made amazing chopped liver and played a mean mah jong

5. Counting from Nisan, Cheshvan is which month?

2nd

4th

6th

8th

Photo: Jaime Spaniol/Unsplash

6. What is the mazal (zodiac) of Cheshvan?

A. Akrav (Scorpio)

B. Moznayim (Libra)

C. Deli (Aquarius)

D. Torah (Taurus)

7. Which biblical event happened in Cheshvan?

A. The Great Flood has ceased

B. The spies returned from scouting Canaan

C. Moses finished writing the first Torah scroll

D. Solomon’s Temple was completed

8. How many days does Cheshvan have?

A. 28 or 29

B. 29 or 30

C. 30 or 31

D. 31

9. Which historic event happened during Cheshvan?

A. Death of Matityahu, leader of the Maccabean revolt (165 BCE)

B. Kristallnacht, considered the first act of the Holocaust (1938)

C. Assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (1995)

D. All of the above

10. Which month comes right after Cheshvan?

A. Tishrei

B. Elul

C. Kislev

D. Tevet

A-C, 2-D, 3-C, 4-D, 5-A, 5-8th, 6-A, 7-D, 8-B, 9-D, 10-C.

By Sari Kopitnikoff -