The story of the African Diaspora is one of unimaginable displacement and extraordinary resilience. Across oceans and centuries, African people carried with them not only the scars of forced migration but also the living seeds of languages, music, beliefs, and traditions that would take root in new lands. These cultural inheritances, transformed through struggle and creativity, remain among the most enduring legacies of human history.

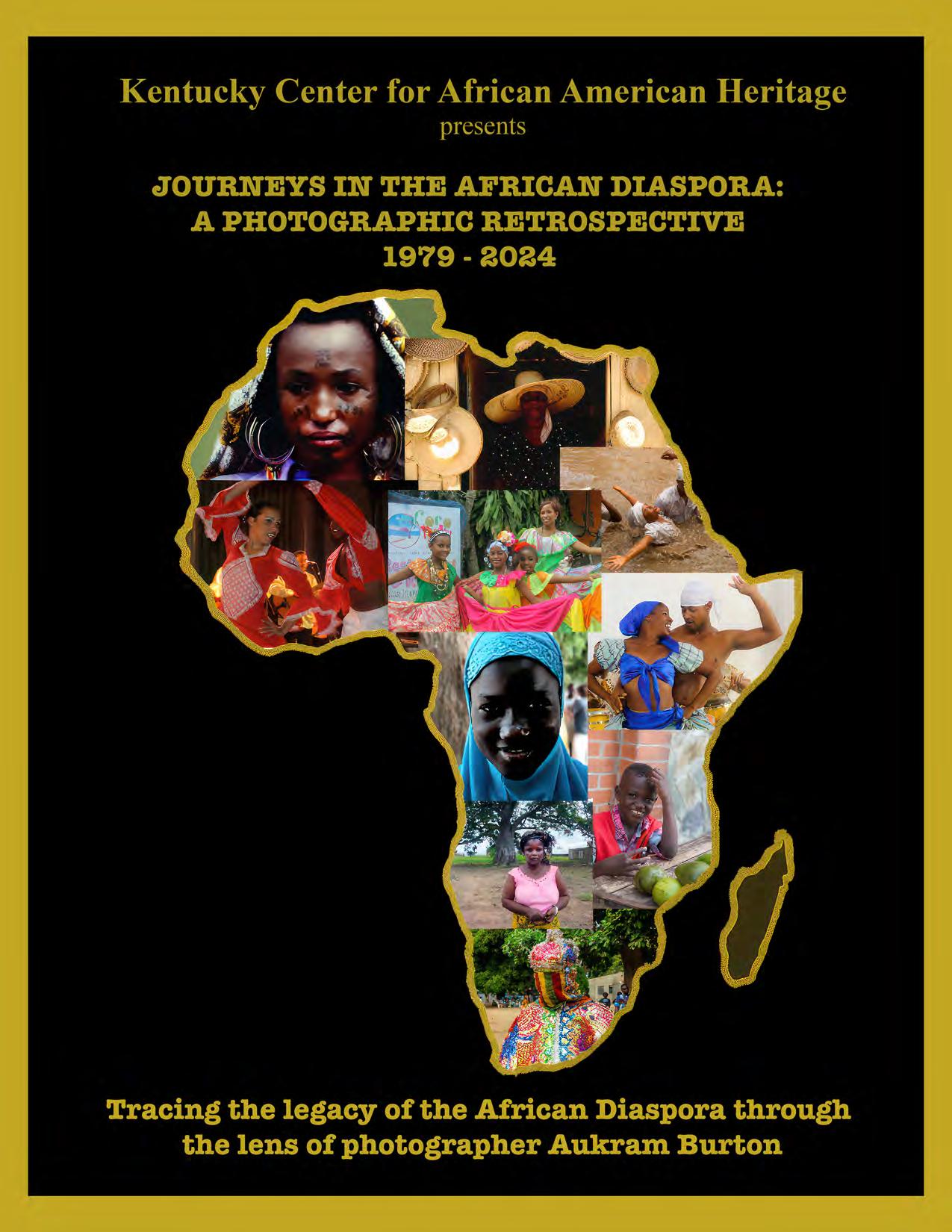

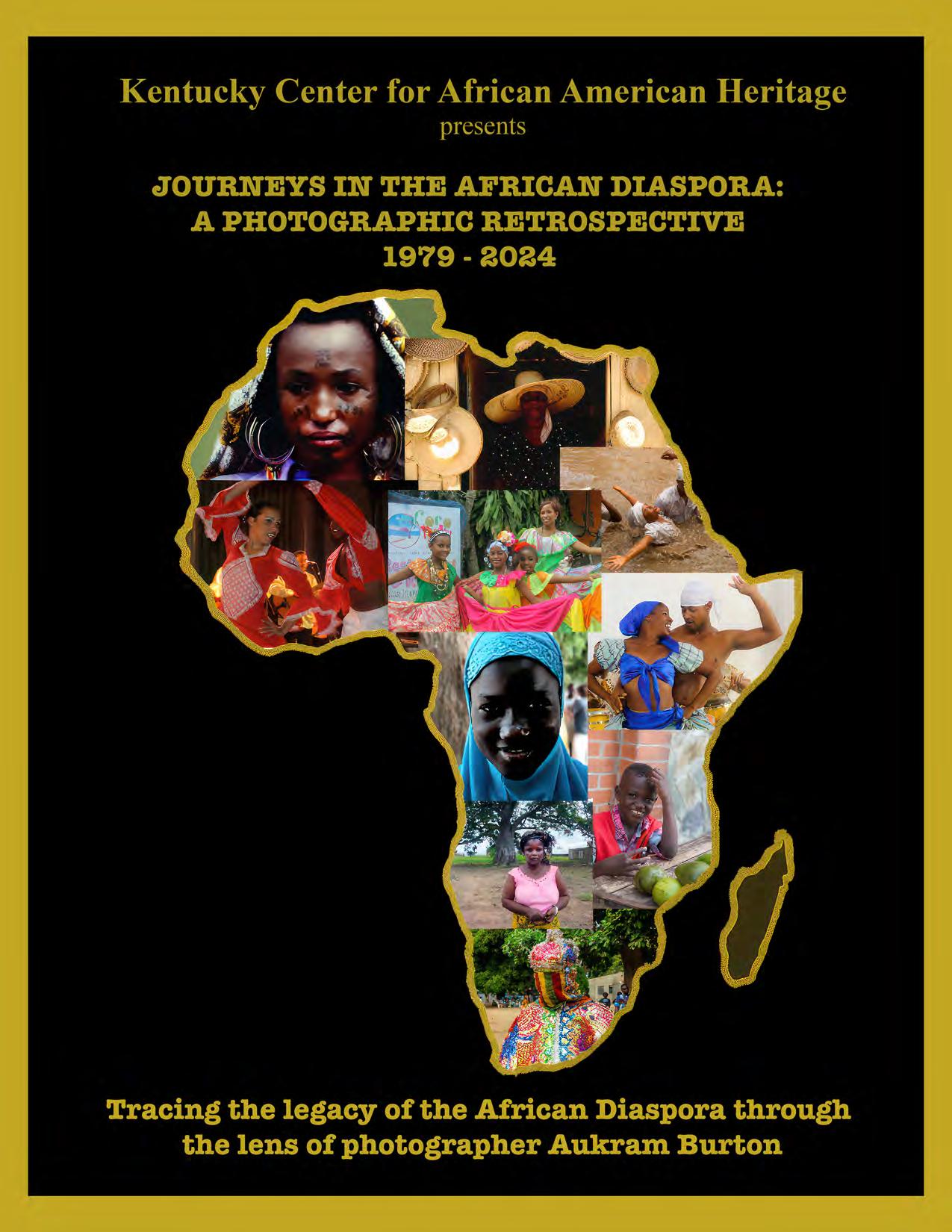

This exhibition, “Journeys in the African Diaspora: A Photographic Retrospective, 1979–2024, ” traces that legacy through the lens of artist Aukram Burton. Beginning with his first trip to Nigeria in 1979, Burton’s camera has documented the landscapes, rituals, and daily lives of Africandescended communities across four continents. His photographs illuminate the continuity of cultural memory from the historic slave dungeons of Ghana and the sacred pilgrimage grounds of Haiti, to the vibrant streets of Bahia in Brazil, the Congo-inspired dances of Cuba, and the enduring traditions of South Africa, Jamaica, Panamá, and Colombia.

The journey begins in West Africa, where the transatlantic slave trade uprooted millions of lives. In places like Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, and Benin, Burton captures both the deep trauma of that history and the cultural vitality that survived it. From the solemn courtyards of Cape Coast Castle to the joyous rhythms of Yoruba Òrìṣà festivals, these images testify to both loss and resilience.

Crossing the Atlantic, the exhibition highlights how African traditions were reshaped in the Americas. In Cuba and Brazil, Yoruba and Kongo spirituality flourished in Santería and Candomblé, while the polyrhythms of rumba and samba became languages of survival. In the Caribbean, African descendants created new cultural forms that combined memory and resistance whether through the conga traditions of Panamá, the freedom struggles of Barbados, or the spiritual processions of Haitian Vodou. In Colombia, maroon communities like San Basilio de Palenque preserved African languages and customs, while the children of Buenaventura embody resilience through games, dance, and music that still carry echoes of their ancestors.

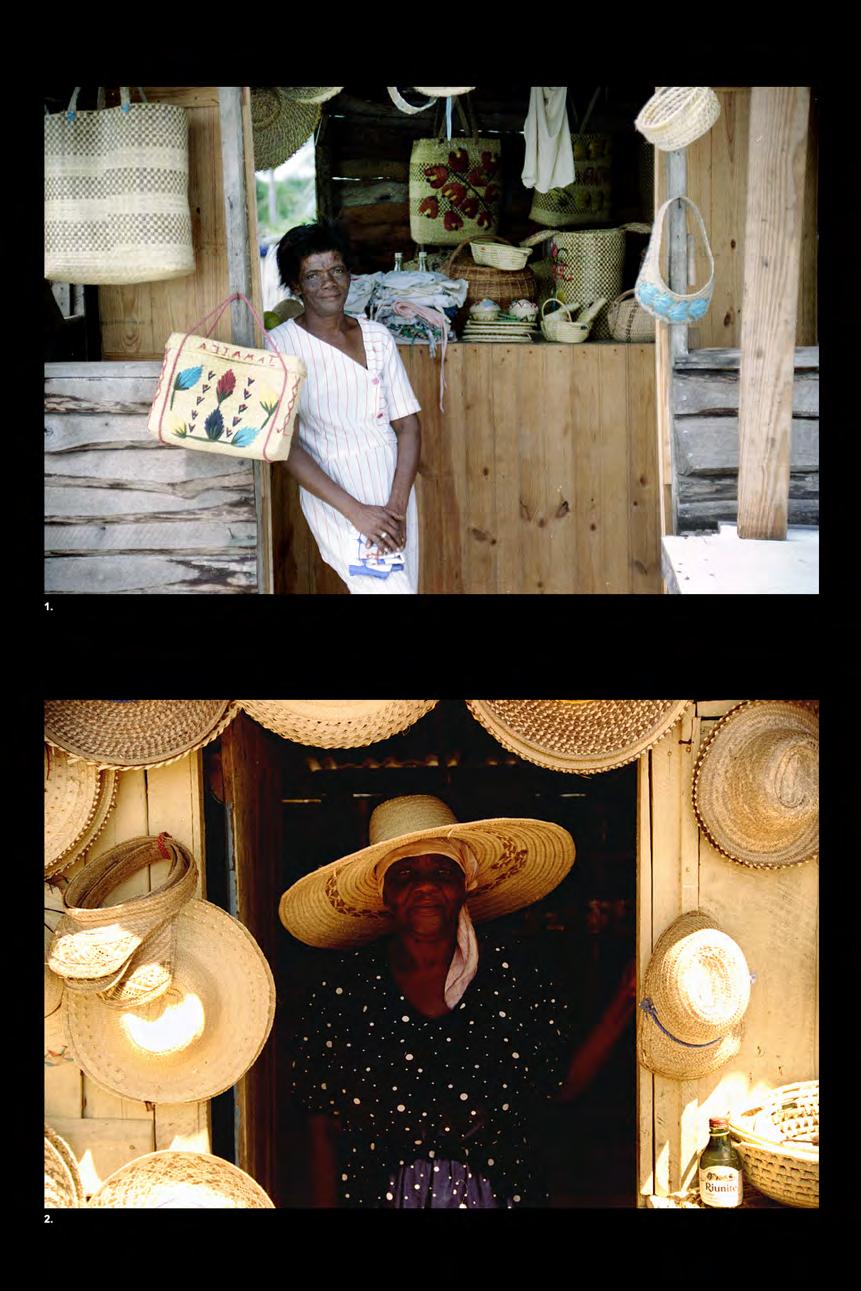

Equally powerful are the contemporary voices of South Africa, where traditional dress, dance, and spiritual practice affirm cultural pride while recalling the struggles of apartheid. In Jamaica, the weaving traditions of Negril speak to the survival of Indigenous and African crafts. Together, these stories create a living map of the Diaspora: diverse in form, yet united in spirit.

More than an exhibition of photographs, this retrospective is a meditation on connection. It invites us to see the Diaspora not as fragments scattered by history, but as a global community bound by memory, struggle, and creativity. Burton’s work challenges us to recognize the African presence not only as a legacy of survival but as an ongoing source of renewal, innovation, and pride.

In retracing these journeys, we honor the ancestors who endured the Middle Passage, the freedom fighters who resisted bondage, and the generations who continue to create beauty and meaning in the face of adversity. This catalog stands as a testament to the power of art to preserve history, celebrate resilience, and remind us that the story of the African Diaspora is not just one of survival, but of triumph.

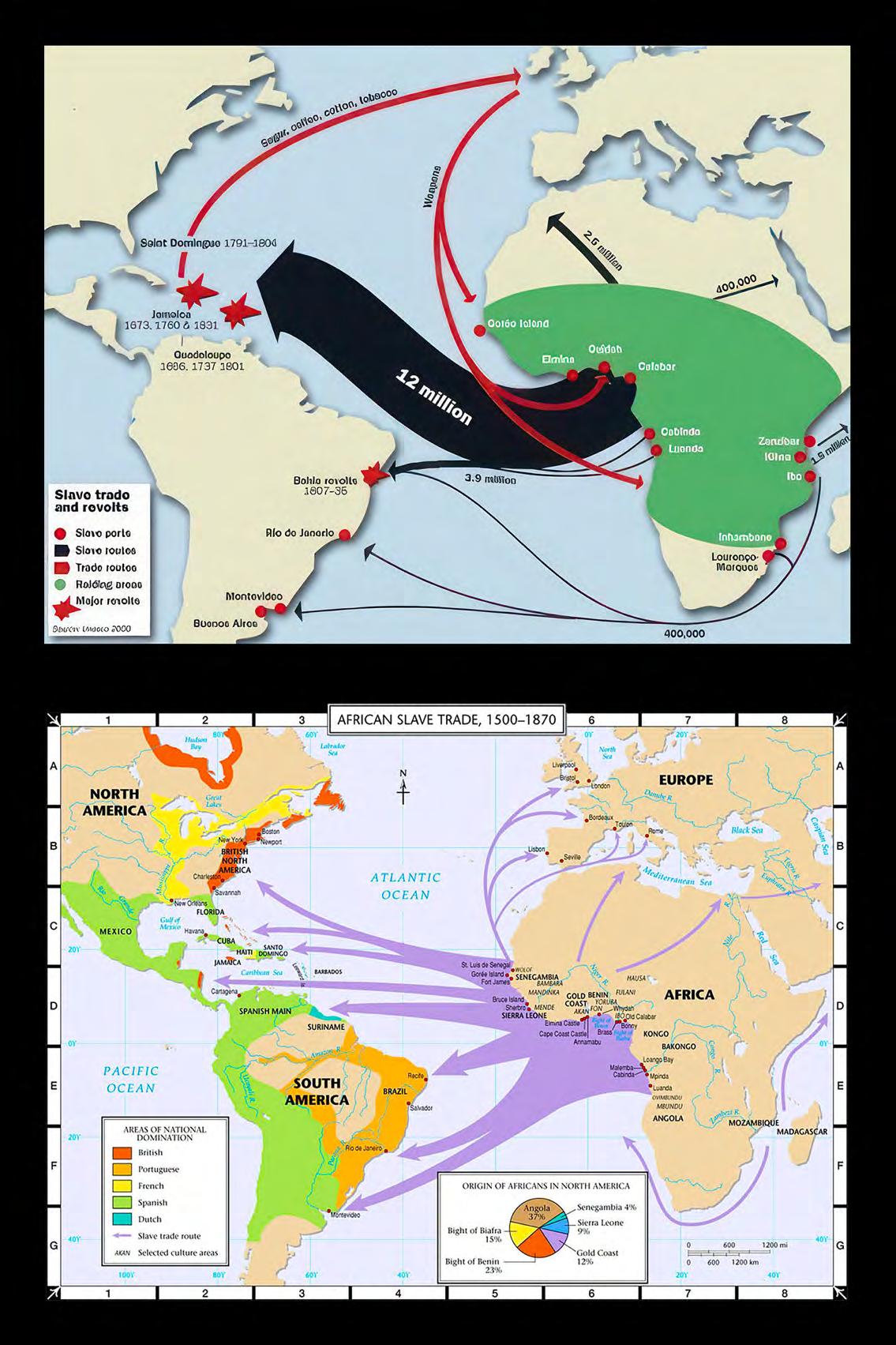

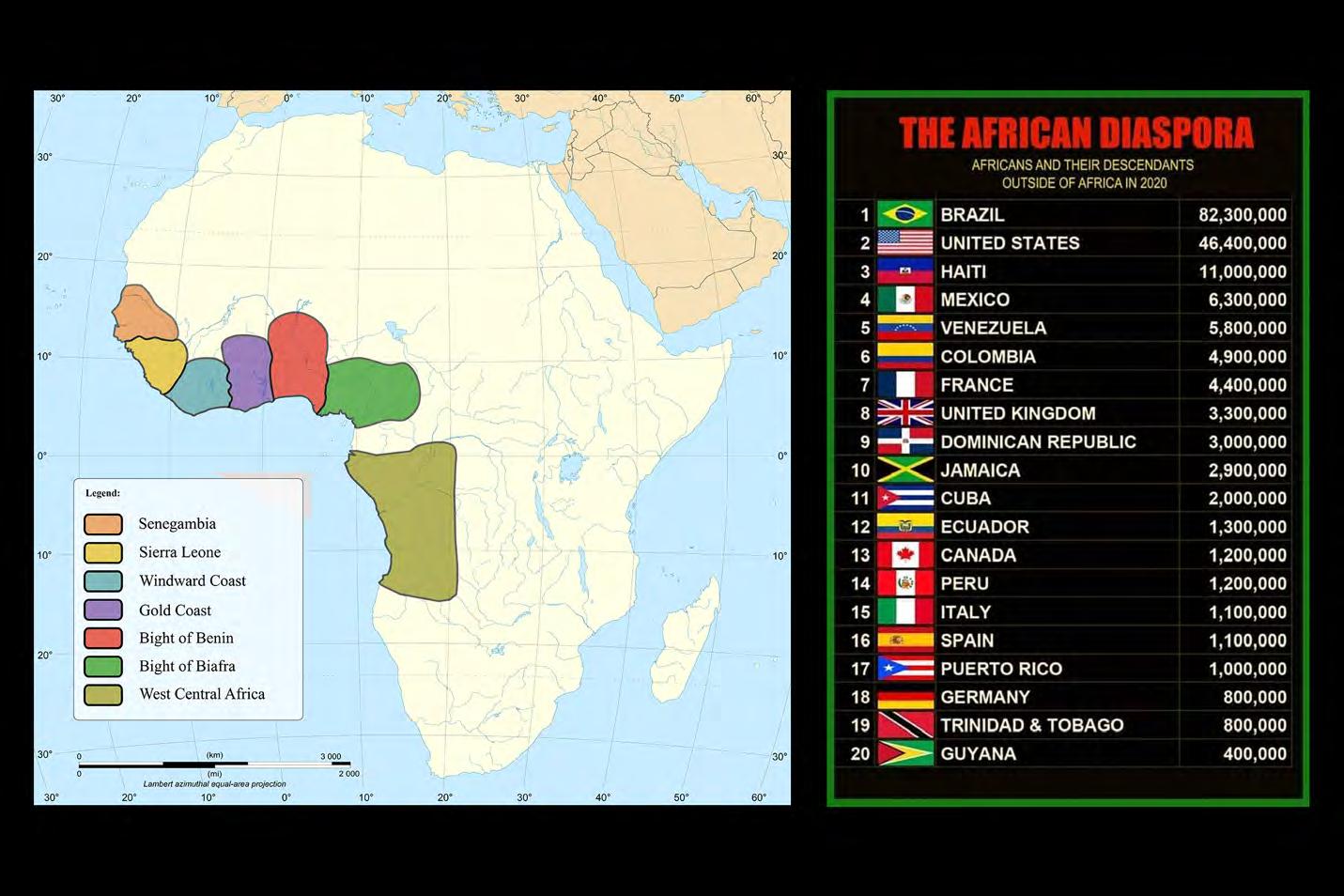

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, West Africa was the center of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. From ports in Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, and Benin, millions were forced onto ships bound for the Americas and Caribbean. They carried with them languages, spiritual practices, and traditions that adapted in new lands while remaining tied to their African origins. Today, the rhythms of the drum, call-and-response in song, vibrant markets, and strong family networks reflect a shared heritage that continues to thrive across the Diaspora.

An estimated 150–200 million people of African descent live outside the continent today. The Diaspora was forged through centuries of forced migration most dramatically the Transatlantic Slave Trade, which drew millions from regions including Senegambia, Sierra Leone, the Windward and Gold Coasts, the Bights of Benin and Biafra, and West Central Africa. More recent voluntary migrations for education, work, and refuge have added to its scope. Across the globe, African-descended communities continue to grow and sustain strong cultural, social, and economic ties to Africa.

My journey began in Nigeria, where I first witnessed the living roots of the African Diaspora. From the shores of West Africa, millions were taken across the Atlantic, carrying languages, beliefs, and traditions that endured and transformed in new lands. This exhibition honors both the pain of that history and the resilience that continues to shape African-descended communities worldwide.

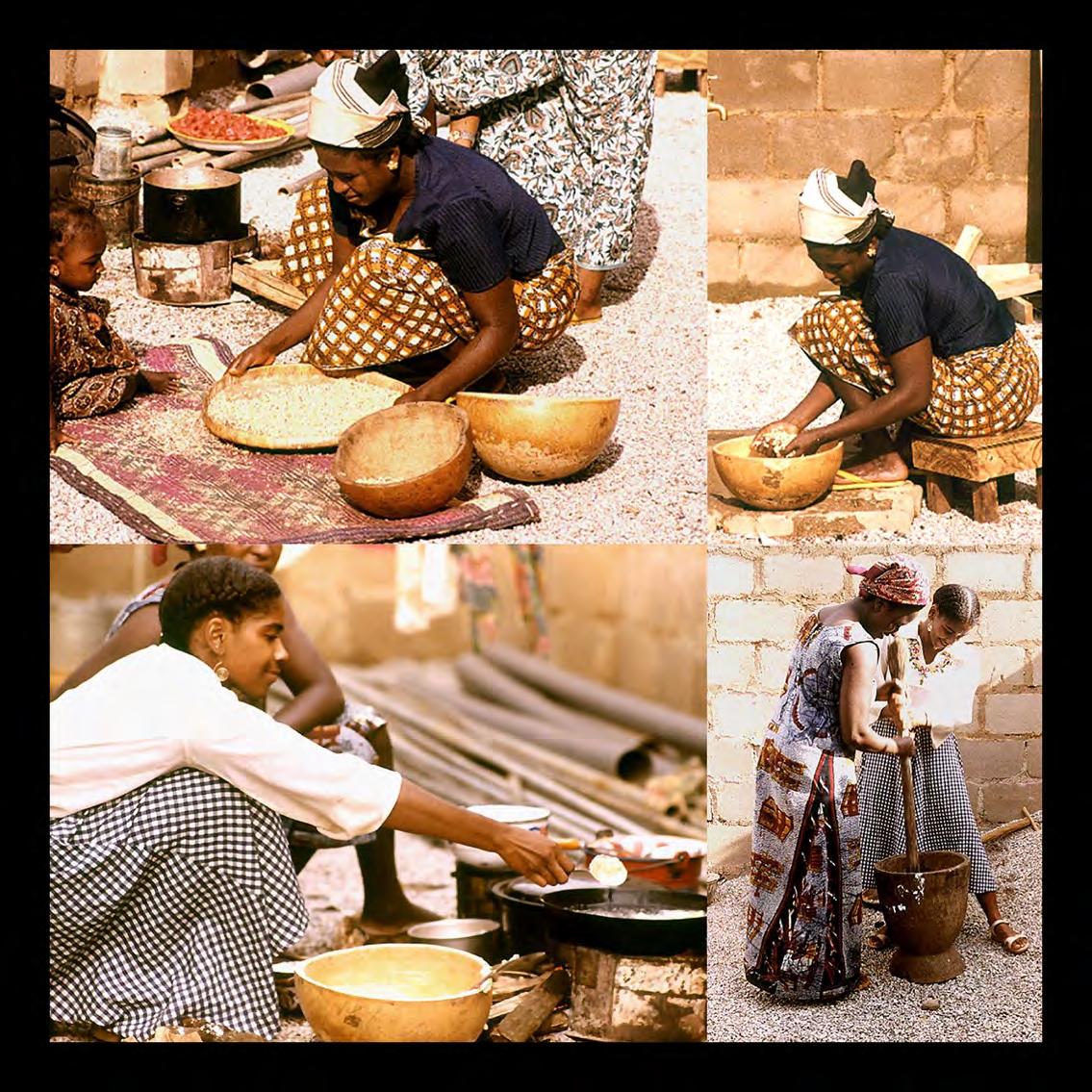

On our first trip to Nigeria in 1979, my wife, Nefertiti, and I were introduced to àkàrà crispy bean cakes that quickly became part of our own diet. Beloved across Nigeria and West Africa (also known as akara, accara, or koose in Ghana), àkàrà is more than food; it carries cultural and spiritual meaning.

Sold daily by street vendors, àkàrà is also prepared for ancestral remembrance, funerals, and festivals, especially in Yorùbá communities, where it symbolizes respect and continuity with the ancestors. Its popularity spans Yorùbá, Hausa, Igbo, and other ethnic groups, making it a unifying dish of Nigerian cuisine.

Enslaved Africans carried this tradition to Brazil, where it evolved into acarajé a sacred food in Afro-Brazilian religion (Candomblé), often offered to the Orisha.

The photos in this series show Nefertiti learning how to prepare àkàrà. Made from black-eyed peas, the beans are soaked, peeled, and ground into a thick paste, seasoned with onions, peppers, and spices. Shaped into balls or patties, they are deep-fried until golden crisp on the outside, soft within. Àkàrà remains a symbol of nourishment, heritage, and resilience across the African world.

Nigeria Series #1

Photography by Aukram Burton

Ibadan & Zaria, Nigeria 1979

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, is home to over 250 ethnic groups and 500 languages. The Yorùbá people, in particular, have had a lasting influence on the cultural and spiritual life of the Americas.

1. Fulani Woman, Zaria: Portrait of one of West Africa’s most widespread ethnic groups.

2. Yemọjá Priestess, Ibadan: A Yorùbá spiritual leader devoted to Yemọja, deity of rivers and the ocean, serving as healer and guide.

3. Human Confidence is Vanity, Ibadan: Proverbs inscribed on everyday objects carry moral lessons; this phrase warns against pride and calls for humility.

Nigeria Series #2

Photography By Aukram Burton

Ibadan & Kaduna, Nigeria, 1979

1. African Ping-Pong, Ibadan: A lively street game captures the energy and creativity of everyday life in Ibadan.

2. Kaduna Worker, Kaduna: Portrait of a laborer whose expression reflects the resilience and determination of Nigeria’s working class.

3. Happy To Be Nappy, Ibadan: A joyful affirmation of African beauty and pride in natural hair.

4. Woman Hold Up Half The Sky, Ibadan: A nod to the strength and essential role of women in sustaining family and community.

Nigeria Series #3

Photography by Aukram Burton

Katsina, Nigeria, 1979

These photos were taken during the Katsina Salah Festival, a celebration that takes place after Ramadan, the Islamic month of fasting. Katsina is located in northern Nigeria, where most residents are Muslim, and many belong to the Hausa ethnic group. The Hausa are one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa.

1. Emir of Katsina and Guards, Katsina: The Emir of Katsina rides with mounted armed guards in a display of pageantry and tradition.

2. Victory Salute, Katsina: A horseman salutes the Emir after winning one of the festival’s celebrated horse races.

3. Talking Drum Player, Katsina: A drummer plays the talking drum, whose pitch can mimic the tones of human speech.

4. Horseman, Zaria, Nigeria: A rider in traditional attire participates in the equestrian heritage of northern Nigeria.

ÒrìsàWorld, Ilé-Ifè, Nigeria

Photography by Aukram Burton

Ilé-Ifè, Nigeria, 2001

These images were taken during the 7th World Congress of Orìṣà Tradition in Ilé-Ifè, Nigeria, August 2001. The biannual Congress brings together practitioners from Africa, the Caribbean, the Americas, Europe, and beyond to honor the Yorùbá Orìṣà religion a centuries-old tradition carried across the Atlantic during the slave trade. In the Diaspora, it inspired practices such as Lucumí and Santería (Cuba), Shango Baptist (Trinidad), Umbanda, and Candomblé (Brazil).

1. Women of Òrìsà: Devotees in ceremonial attire honor the Orìṣà.

2. Ilé-Ifè Dancers: Traditional Yorùbá dances express cultural pride and devotion.

3. Ṣàngó Dancers: Dancers invoke Ṣàngó, Orìṣà of thunder and lightning.

4. Egúngún Dancers: Masked performers embody ancestral spirits, linking past to present.

Under the Vulture Tree

Photography by Aukram Burton Salaga, Ghana, 2010

Under this Baobab tree in Salaga is the "Slave Cemetery," where the bodies of Africans who died at the Salaga Slave market in northern Ghana were dumped for vultures to feast on. A white cloth is tied around the tree and reads:

IN EVERLASTING MEMORY OF THE ANGUISH OF OUR ANCESTORS MAY ALL OF THE DEPARTED SOULS FIND SOLACE AND PERFECT PEACE IN THE BOSOM OF OUR LORD AND FOR THOSE WHO RETURN, FIND THEIR ROOTS MAY HUMANITY NEVER EVER· PERPETRATE SUCH INJUSTICE AGAINST HUMANITY WE THE LIVING VOW TO UPHOLD THIS

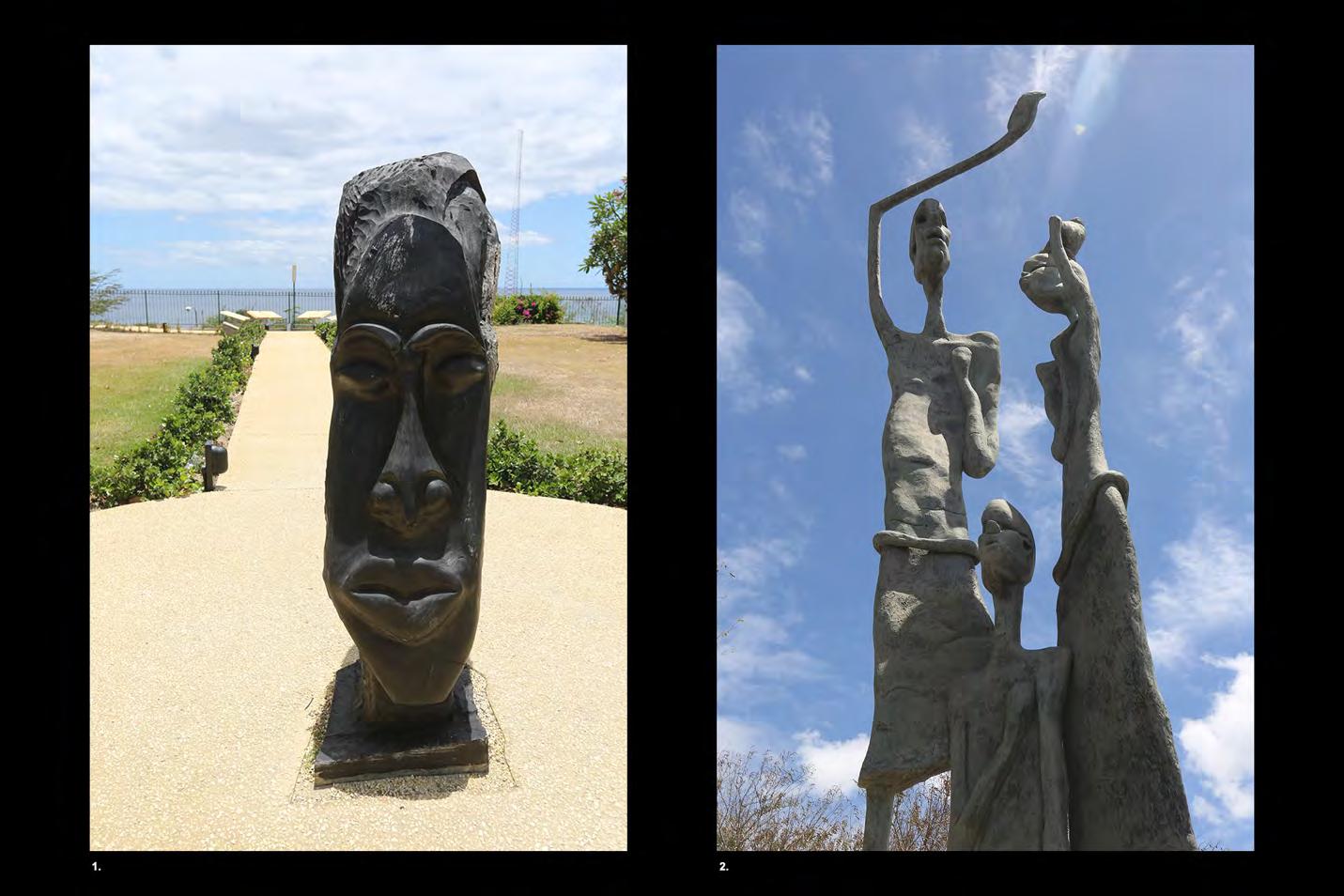

Ghana: The Citadel for Pan-Africanism

Photography by Aukram Burton

Accra, Ghana, 2010

1. Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park: Dedicated to Ghana’s first president and African liberator, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972), a leading advocate for Pan-African unity and independence.

2. Statue of President Kwame Nkrumah: Known as “The Father of Pan-Africanism,” Nkrumah championed global African solidarity, inspired by his studies in the U.S. and his vision of unity rooted in indigenous knowledge.

3. President Nkrumah Burial Site: Originally buried in his hometown of Nkroful, Nkrumah’s remains now rest in this mausoleum, visited daily by Ghanaians and tourists.

4. George Padmore Memorial: Memorial to George Padmore Trinidad-born Pan-Africanist, political thinker, and adviser to Nkrumah renowned for his global fight for African liberation.

5. George Padmore Research Library: Founded in 1961 as a monument to Pan-Africanism, this library holds Padmore’s and Nkrumah’s collections, preserving key African political and cultural history.

6. W.E.B. Du Bois Memorial Centre: Honoring W.E.B. Du Bois, civil rights leader and PanAfricanist, the center houses his manuscripts, library, and celebrates his lifelong fight for African unity.

7. W.E.B. Du Bois Grave Site: A national monument enshrining the remains of Du Bois and his wife, Shirley, ensuring their legacy endures for future generations.

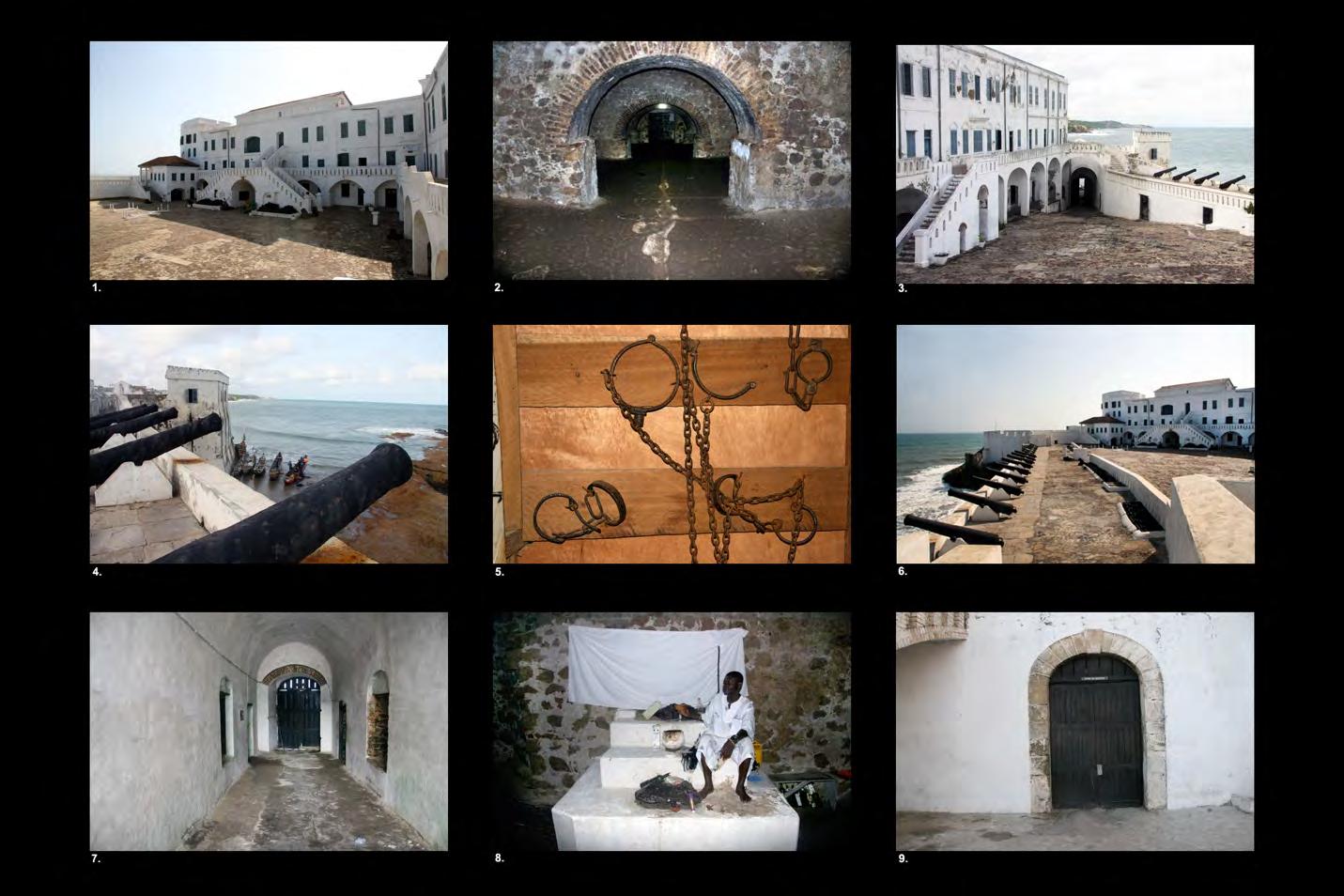

Cape Coast Holocaust Dungeons

Photography by Aukram Burton

Cape Coast, Ghana, 2010

1. Brick Courtyard Brick courtyard with two 18-foot water wells and four graves.

2. Dungeon Chambers: Five male dungeons held up to 1,000 men; two female dungeons held 300 women. Those who resisted were sent to the condemned cell to die slowly without food, water, or light.

3. Courtyard & Door of No Return Courtyard view with the Door of No Return, passage to slavery for millions over more than a century.

4. Cannons & Cannonballs Black cannons and cannonballs guarded the castle against seaborne attack.

5. Branding & Shackling: The strongest men were branded with hot irons, then chained and shackled together.

6. Fortress Defenses: Balustrades and cannons protected the British from rival European powers and pirates.

Elmina Holocaust Dungeons

Photography by Aukram Burton Elmina, Ghana, 2010

1. Expansion of Elmina: Elmina was enlarged to hold large numbers of African captives for the slave trade, eventually doubling in size.

2. Moat & Entrance: A drawbridge and stone bridge crossed the double moat leading to the castle’s main gate.

3. Governor’s Balcony: From this balcony, female captives were selected and often raped; those who refused were chained and exposed to the elements without food or water.

4. Courtyard & Church: The Portuguese church, rebuilt after battles, stood in a courtyard surrounded by dungeons holding men and women bound for the slave trade.

5. Life Outside the Dungeons: Nearby, fishing-related commerce took place alongside scenes of human suffering.

6. Condemned Cell: African rebels were confined here to starve in darkness. Nearby, a separate airy cell held misbehaving European soldiers, who were eventually freed.

7. Church Over Dungeons: Church services were held above dungeons for female captives. Churches profited from slavery, owning plantations and enslaved labor.

8. Male & Female Dungeons: Two main dungeons held up to 1,200 captives at a time before transport.

9. Transit Dungeon & Door of No Return: Captives were moved through twisting, lowceilinged dungeons to the Door of No Return, then ferried by canoe to slave ships bound for the New World.

Reenactment at the River Pra

by Aukram Burton

Assin Praso, Ghana, 2011

Local actors reenact the brutal conditions endured by Africans during captivity showing their sorting by age and gender, and the bartering process between slavers. Assin Praso was a key transit point where captives, forced to march barefoot from the north through the Ashanti Region, suffered starvation, abuse, and beatings on their way to Cape Coast and Elmina Castles.

2011 PANAFEST Candlelight Vigil

Photography by Aukram Burton

Cape Coast, Ghana, 2011

PANAFEST is a biennial festival celebrating Pan-African unity and using arts and culture to honor African history and resilience. In 2011, participants held a midnight candlelight vigil in Cape Coast, marching to the Castle and dungeons where enslaved Africans were once held. The ceremony, led by traditional and religious leaders, honored ancestors of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and concluded with music, poetry, and speeches from leaders across the African Diaspora.

1. Participants gather around the fire in the center of Cape Coast before the vigil begins.

2. & 3. Midnight Candlelight Vigil through the city of Cape Coast to the Cape Coast Castle and Dungeons.

4. The festival concluded with a candlelit procession to Cape Coast Castle, where leaders honored enslaved ancestors in the dungeons. The night ended with music, poetry, and speeches from scholars and leaders across the African Diaspora.

Owudo Aseiku, 10th

Photography by Aukram Burton

Assin Praso, Ghana, 2011

Nana Owudo Aseiku, 10th, Paramount Chief of Assin Jakai and Assin Praso. He leads a procession during the 2011 PANAFEST at Assin Praso Heritage Village. Historically, Assin Praso was a stop where captives from the north rested before being sent to Assin Manso, and then to Elmina or Cape Coast for sale. Ghana observes Emancipation Day to honor African resistance, liberation, and the fight for human rights.

Senegal: Gorée Island, Dakar’s vibrant street life. Senegal, located on the westernmost tip of Africa, has long been a crossroads of cultures, ideas, and trade. Shaped by a blend of Wolof, Serer, Pulaar, Jola, Mandinka, and other ethnic traditions, its history reflects both the resilience of its people and the enduring legacy of its role in global exchange from the medieval empires of West Africa to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, colonial encounters, and independence in 1960. Today, Senegal thrives as a hub of vibrant markets, dynamic music, rich Islamic scholarship, and a deep commitment to preserving cultural heritage while engaging with the modern world.

In the bustling streets of Dakar, a vendor sells hand-crafted dolls dressed in colorful fabrics, reflecting Senegal’s artistry and storytelling traditions. These dolls, often crafted from local textiles, embody both creativity and cultural pride, offering visitors a tangible piece of Senegalese identity to take home.

Gorée Island, Senegal

Photography by Aukram Burton Gorée Island, Senegal 2008

1. Gorée Island: As the boat leaves Dakar, capital of Senegal, it isn’t long before Gorée Island comes into view.

2. Door of No Return: The “Door of No Return” symbolizes the final separation from Africa for enslaved people. Whether used for transporting captives to departing ships, it now serves as a powerful site of reflection for the African Diaspora.

3. Maison des Esclaves: Located on Gorée Island, the Slave House is a memorial to the millions of Africans taken during the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978, it remains a global symbol of remembrance.

Photography by Aukram Burton

Dakar, Thiès, and Saint Louis, Senegal, 2007

These images were captured while walking the streets of Dakar, Thiès, and Saint Louis known as Ndar in Wolof revealing everyday life and cultural traditions in Senegal.

1. Confidence (Egg Vendor): A street vendor carries a tray of eggs balanced with skill and poise, embodying self-assurance in daily work.

2. Talibé Students: These boys are Talibés Muslim students living with a Marabout (Islamic religious teacher) to receive a traditional Quranic education. Often sent from rural areas by families of varied means, Talibés contribute labor in exchange for religious instruction, a path considered a rite of passage into adulthood.

3. Muslim Girl, Thiès: A portrait of a young girl in traditional attire, reflecting Senegal’s rich blend of faith and culture.

4. Kora Player, Saint Louis Jazz Festival: Ablaye Cissako performs with his band at the 15th Saint Louis Jazz Festival, an annual celebration showcasing jazz, blues, gospel, and related music, now central to Senegal’s cultural landscape.

Ouidah, on Benin’s Atlantic coast, was one of West Africa’s busiest slave ports between the 16th and 19th centuries. From here, over a million Africans began their forced journey to the Americas. The four-kilometer Slave Route to the Gate of No Return marks their final steps on African soil, lined with monuments such as the Tree of Oblivion, Memorial of Zoungbodji, and Tree of Return. Today, Ouidah stands as a place of remembrance and resilience, honoring the millions lost to the trade.

Photography by Aukram Burton Ouidah & Porto Novo, Benin

1. Door of No Return (2023): This concrete and bronze arch stands on the beach as a memorial to enslaved Africans who were taken from the port of Ouidah to the Americas.

2. Dada Daagbo Hounon Houna II, Ouidah (2020): Supreme Vodun spiritual chief, presiding over the UNESCO-backed Ouidah Festival of Vodun Arts and Culture.

3. De-Gbeze G Ayontinme Tofa IX, King of Porto Novo (2020): A leader in reconciliation efforts addressing the legacy of slavery.

4. Martine de Souza (2023): Descendant of Brazilian slave trader Francisco Félix de Souza, she has publicly expressed regret and asked forgiveness on behalf of her family.

Originating more than 6,000 years ago in what is now Benin, Vodun meaning “spirit” in the Fon and Ewe languages is practiced today by over 60 million people worldwide. It is the traditional religion of the Fon people of Benin and parts of Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria, with related forms in the African Diaspora such as Haitian Vodou, Brazilian Vodum, and Louisiana Voodoo.

Often misrepresented in popular culture, Vodun is rooted in healing, community, and ancestral reverence. Enslaved Africans carried these traditions across the Atlantic, where they became vital to cultural survival. In Benin, the annual Ouidah International Festival of Vodun Arts and Culture celebrates this heritage with music, dance, and colorful regalia honoring resilience, confronting the legacy of the slave trade, and fostering healing across the African world.

Vodun: Spirit and Survival

Photography by Aukram Burton

Ouidah & Porto Novo, Benin, 2023

1. Give the Drummers Some: Drum rhythms pulse throughout the week-long Vodun Festival, driving ritual dances and summoning the spirits.

2. Meko Koku Devotees: Devotees of Meko Koku, the Vodun deity of war, cover their hair and bodies with palm oil to invite his presence. Guided by sacred drum rhythms, they whirl into trances (Koku Houn), channeling the warrior’s power to perform feats of endurance and strength.

3. Devotee of Legba: Legba, a spirit of fertility and healing, is said to enjoy tobacco. To invoke his aid, a lit cigarette or cigar is placed in his mouth.

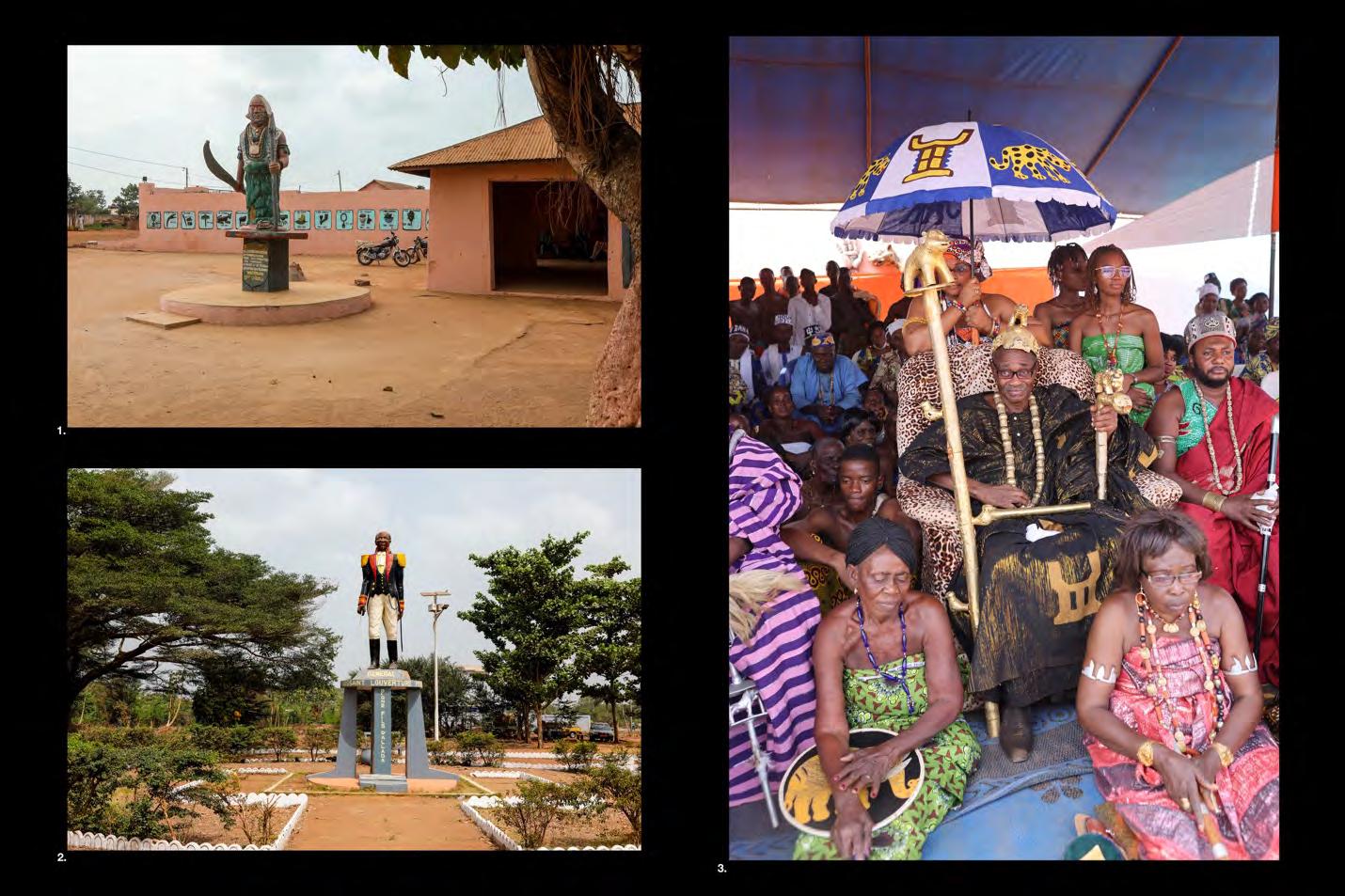

Allada: Legacy of a Kingdom

Allada, in southern Benin, is a historic Fon kingdom founded in the 13th century and revered as the ancestral homeland of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the hero of the Haitian Revolution. Today, its royal palace, memorial sites, and annual Vodun festivals honor both its deep ancestral roots and its enduring influence on the African Diaspora.

Allada: From Kingdom to Revolution #3

Photography by Aukram Burton

Allada, Benin

1. Royal Palace of Allada, 2020: A statue erected in the courtyard outside the Royal Palace of Allada. The writing in French says: “The kingdom of Allada was founded around the 13th century by the revered ancestor Adjahouto Yegou Debalato”.

2. Ancestral Homeland of Toussaint L’Ouverture, 2020: Allada is the birthplace of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian general and the most well-known leader of the Haitian Revolution. This is a memorial park dedicated to Toussaint L’Ouverture.

3. Kpodégbé Lanmanfan Toyi Djigla, King of Allada, 2023: The 16th king of the Fon State of Allada is celebrating the festivities of Allada’s Vodun Festival in central Benin.

Along Benin’s Ouidah Slave Route, monuments honor both the suffering endured and the courage shown in the face of oppression. At Zomachi Memorial Park “the fire that never goes out” in Fon a wall commemorates freedom fighters from Kwame Nkrumah to Harriet Tubman. In nearby Cotonou, a 100-foot statue of the Dahomey Agojie pays tribute to the kingdom’s legendary all-female regiment, whose skill and bravery defended their homeland for over two centuries. Together, these memorials connect past struggles to present resilience, ensuring that the spirit of resistance continues to inspire future generations.

Monuments to Resistance

Photography by Aukram Burton Ouidah, Benin

1. Zomachi Memorial and Place of Remembrance (2020): Honors enslaved Africans and freedom fighters of the Diaspora, including Nkrumah, Du Bois, Garvey, Boukman, Phillis Wheatley, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and Tubman.

2. Dahomey Agojie (2023): A towering statue of the famed all-female regiment of Dahomey, remembered for their fearlessness from the 17th to 19th centuries.

Women of South Africa: Traditional Dress

Photography by Aukram Burton

Traditional Dress, beadwork, and rituals reflect the cultural pride and heritage of South African women.

1. Asanda Mtyi is wearing Xhosa traditional dress. (2002)

2. Halejoetse Tsehlana is wearing Basotho traditional dress. (2002)

3. Kenevoe Ntabe is wearing Basotho traditional dress. She is holding a handmade hat called "mokorotlo," inspired by the Qiloane Mountain in Lesotho. (2002)

4. Dudu Dlamini from Swaziland is wearing traditional dress called "emahiya.” (2002)

5. Tandeka Ntlantsana is wearing a traditional Xhosa dress. Her head wrap is called "isithuthu," representing the Mfengu people. (2002)

6. Nosimo Zisiwe Balindlela, the former Premier of the Eastern Cape in South Africa, is wearing traditional Xhosa dress. (2004)

7. Xhosa woman with pipe: In the Eastern Cape, pipe smoking is a longstanding tradition. Hand-carved wooden pipes, often decorated with beads, symbolize social status and are smoked by men and elderly women during ceremonies. (2003)

8. Tembeka Mapetshana, beadwork artist: Umtata-based artist teaching traditional beadwork and leading women’s cooperatives for cultural preservation and economic empowerment. (2004)

Xhosa Traditional Dance

Photography by Aukram Burton Grahamstown, South Africa, 2005

1, 2, 3, & 4: This series of photographs documents a long tradition of dancing and music among the Xhosa people of South Africa. The Xhosa people are actually called the amaXhosa, and they speak isiXhosa, a Bantu language. They're one of the major ethnic groups in South Africa. Nelson Mandela is a Xhosa.

Photography by Aukram Burton Langa and Cape Town, South Africa

1.-3. Reverend Phiwe Daweti delivers a passionate Sunday sermon at Hlalani Ninoxolo Phakathi Kwenu Baptist Church in Langa township.(2003) Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Nobel Peace Prize laureate (1984), was the first Black Archbishop of Cape Town and a global voice against apartheid, racism, poverty, and injustice. (2005)

Cultural Survival & Transformation

Barbados: Freedom Footprint Tour #1

Photography by Aukram Burton, 2016

Dr. Henderson Carter, Professor of History at the Cave Hill Campus of the University of the West Indies, at the Newton Slave Burial Ground, as part of the Freedom Footprints Tour.

Barbados: Freedom Footprint Tour #2

1. Quaw's Quest: A Beacon of Resilience

Quaw, a 37-year-old African from Guinea, was enslaved and brought to Barbados, where he endured two decades of bondage. After Emancipation, he pursued education, family, faith, and dignity embodying the collective aspirations of his community. His story, commemorated at the Cave Hill Campus of the University of the West Indies, stands as a symbol of hope, resilience, and rebirth.

2. Rock Hall Freedom Village

Established in 1841 in St. Thomas, Rock Hall was Barbados’ first free village founded by freed slaves. A 20-foot bronze monument, unveiled in 2005, honors their resilience and new beginnings after Emancipation.

Barbados holds a powerful legacy of resistance to oppression, from Bussa’s 1816 rebellion against slavery to Clement Payne’s leadership in the Caribbean labor movement of the 1930s. Their sacrifices and vision helped shape the island’s path toward freedom, justice, and national identity legacies still honored and celebrated today.

Barbados: Freedom Footprint Tour #3

Photography by Aukram Burton, 2016

1. Clement Osbourne Payne: Born in Trinidad in 1904 to Barbadian parents, Clement Payne became a leading voice for social justice and the Caribbean trade union movement. He fought for workers' rights against the entrenched “plantocracy,” inspiring a legacy of resistance that endures to this day. Recognized as one of Barbados’ ten National Heroes in 1998, his memory lives on through the Clement Payne Cultural Center.

2. Bussa Emancipation Statue: Bussa Monument Born free in West Africa, Bussa led a major 1816 slave rebellion in Barbados before being killed in battle. Though suppressed, the uprising shaped the island’s path to freedom. Honored as a National Hero in 1998, Bussa is commemorated by the 1985 Emancipation Statue in St. Michael.

Òṣun: The Great Mother

Photography by Aukram Burton

Havana, Cuba, 2012

This dancer honors Òṣun, the Yorùbá Orìṣà of rivers, fertility, and love. With graceful, flowing movements, the dancer embodies her nurturing spirit and life-giving power, representing the nurturing force of beauty, healing, and renewal, revered as the divine mother of creation. This photo was taken at Palacio de la Rumba (Palace of Rumba), which promotes the rumba genre, declared in 2012 as Cultural Heritage of Cuba and in 2016 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Dance in Cuba symbolizes both celebration and survival an inheritance carried across the Atlantic from Africa. The rhythms of the Kongo and Yorùbá peoples persist in Cuban streets, festivals, and sacred spaces. Rumba, with its call-and-response chants and polyrhythms, evolved from Kongo traditions into one of Cuba’s most iconic cultural expressions. In sacred settings, Orìṣà dances of Santería honor deities such as Yemọjá, the mother of the sea, whose flowing movements resemble those of ocean waves. Together, these dances embody resilience, faith, and creativity, reaffirming Africa’s lasting influence on Cuban identity.

1. Rumba Guaguancó Dancers: Performing a rumba style with Kongo roots, guaguancó is a flirtatious couples’ dance marked by playful chase and evasion. Havana, Cuba, 2012.

2. Congo (Palo Monte) Dancer: A dance rooted in Central African Kongo spiritual traditions, these dances are vigorous and drum-driven, performed in circles or lines expressing daily life, spiritual possession, and ancestral invocation. The rhythms and movements have strongly influenced Cuban rumba and carnival traditions, Matanza, Cuba, 2013.

3. Ballroom Rumba Dancers: Performing the rumba, like other styles of rumbas, is known for its sensual and romantic feel, often described as mimicking courtship rituals. This style is closely related to the Cha-Cha. Havana, Cuba, 2007.

4. Dance of Yemọjá: Rooted in Yorùbá tradition, the dance of Yemọjá honors the Orìṣà of rivers and oceans. With sweeping, wave-like arm and torso movements and flowing skirts, it evokes the sea’s healing power and nurturing force. Havana, Cuba, 2012.

Malcolm and Martin in Cuba

Photography by Aukram Burton

Havana, Cuba, 2007

This Havana park situated on Avenida 23 in between Calle F and Calle E in Vedado, Havana, features a monument honoring Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., symbols of the global fight against racism a struggle that also resonates in Cuba. For years, Ms. Juanita Fernandez has cared for the site, proudly noting she was born the same day and year as Dr. King.

Haiti declared independence on January 1, 1804, becoming the first Black republic. It is the only nation born from a successful slave rebellion, defeating France, Britain, and Spain.

In Haiti, Vodou is not only a spiritual practice but also a living bridge to Africa and a foundation of national identity. Each Easter, the village of Souvenance becomes the heart of the country’s most sacred Vodou pilgrimage, where music, dance, and ritual affirm ties to African ancestors. Rooted in traditions carried from Dahomey (present-day Benin), ceremonies at Souvenance honor the spirits (Lwa), celebrate resilience, and preserve the collective memory of the Haitian people whose faith and courage gave birth to the world’s first Black republic.

Photography by Aukram Burton Souvenance, Haiti, 2016

Easter time in Souvenance, Haiti, is all about Rara. Throughout the country, these raucous bands on foot take to the streets and dusty roads, beating drums, chanting, and blowing cylindrical horns known as a vaccine. Souvenance on Easter Sunday is the site of Haiti's largest and most sacred Vodou pilgrimage, the ultimate destination for many of the Rara bands, attracting hundreds of followers. A parade of women dancers wearing vibrant clothes decorated with glitter and costumed characters, such as Queens, Presidents, Colonels, and other representatives, are key symbolic figures of Rara. Women dancers hike up their skirts as they strut to the blaring horns of the Rara band, baring their panties and bellies.

Venerating Ancestors, Preserving Roots #2

Photography by Aukram Burton, 2016

Souvenance, Haiti, 2016

1. Fernand Bien-Aime, spiritual leader of the Lakou, performs a ritual to Legba, marking the start of Haiti’s most sacred Vodou pilgrimage. Souvenance was founded by freed Africans from Dahomey (Benin).

2. Devotees bathe in sacred waters for spiritual renewal, tracing practices back to West Africa. Here, the Lwa Ogou (Ogun) is venerated, said to have inspired the Haitian Revolution. 3 & 4. Dressed in white, Vodou devotees honor the sacred Mapou tree, circling it to symbolize the Middle Passage. Preserved by elders, the Mapou is revered as a dwelling of spirits and a powerful symbol of African ancestry and resilience.

Weaving in Negril reflects the island’s deep Indigenous and African heritage. The Taino people, Jamaica’s first inhabitants, crafted clothing, baskets, and utensils from palm and coconut leaves techniques still practiced today. Enslaved Africans added new skills and patterns, blending traditions into a vibrant craft culture. Weaving remains a resilient cottage industry and a vital link to Jamaica’s past, honoring the creativity and survival of its people across generations.

Between 1561 and 1860, Brazil received nearly 5 million enslaved Africans, about 70 percent from Angola. This massive forced migration shaped Brazil’s cultural and spiritual life. Two major influences stand out: the Yorùbá Orìṣà traditions from Nigeria and Benin, and Central African practices. Out of this heritage emerged Candomblé, an African-Brazilian spiritual tradition practiced by the povo de santo (“people of the saint”). Rooted in the cities of Salvador and Cachoeira then key hubs of the slave trade Candomblé blends Yorùbá, Bantu, and other African traditions, creating one of the most enduring expressions of African spirituality in the Americas.

Mãe Beata de Yemanjá

Photography by Aukram Burton Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2005

Beatriz Moreira Costa, better known as Mãe Beata de Yemanjá (1931–2017), was the head priestess of a Candomblé temple in Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro. She was a spiritual leader, writer, and social and political activist. Mother Beata was a priestess of Yemọjá, rooted in the Yorùbá tradition of West Africa, and part of a lineage of Ialorixás (Mother of the Òrìṣà). Through her wisdom, she managed to unite tradition and modernity without losing the essence and values passed down by her ancestors.

Acarajé in Brazil

Photography by Aukram Burton Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2005

Acarajé: Sacred Street Food originating in West Africa as àkàrà (also called koose), this beloved dish traveled to Brazil with enslaved Africans. Made from black-eyed peas, shaped into balls, and deep-fried, acarajé is now a staple of Bahian street food, often served with spicy palm oil sauces. Beyond its flavor, acarajé holds spiritual significance in Candomblé, where it is offered to the Òrìṣà and eaten as a source of blessings and protection. Today, it remains both a cherished culinary tradition and a living link between Brazil and West Africa.

Modelo Market

Photography by Aukram Burton Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 2005

Mercado Modelo is Salvador’s most famous market, offering crafts, music, and African-Brazilian cuisine in a lively waterfront setting. Beneath its vibrant stalls lies a sobering past its underground chambers once held enslaved Africans during the colonial era.

Spirit of Bahia: Faith, Rhythm, and Resistance

Photography by Aukram Burton

Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 2005

1. Omolu Devotion: A worshiper of Omolu (São Lázaro), the Yorùbá Òrìsà of sickness and health, walks the streets of Salvador carrying popcorn, candles, and a statue of the deity. Such offerings, central to Candomblé rituals, reveal the city’s blend of Catholicism, African spirituality, and Indigenous traditions that make Salvador the heart of Afro-Brazilian religion.

2. Dique do Tororó: This lagoon is home to eight striking sculptures of the orixás Oxum, Ogum, Oxóssi, Xangô, Oxalá, Iemanjá, Nanã, and Iansã created by artist Tatti Moreno in 1998. Lit dramatically at night, the site reflects Salvador’s layered history as a former capital of Brazil and key port in the transatlantic slave trade.

3. Capoeira: A Warrior’s Dance: On a street corner, young men practice Capoeira, the AfroBrazilian martial art born of slavery. Combining self-defense, acrobatics, dance, and music, it is both a form of resistance and a ritual. A line of musicians plays berimbaus, drums, and bells, sustaining the rhythm of survival and freedom.

4. Youth Drum Corps: The Projeto Águas de Março ensemble exemplifies how youth programs in Bahia preserve Afro-Brazilian heritage, teaching the rhythms and dances that continue to inspire cultural pride and continuity.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, Cartagena became one of the largest slave ports in Spanish America, where Africans were brought to work in mines, plantations, and urban households. Many resisted enslavement by escaping to form independent maroon communities, the most famous being San Basilio de Palenque, which still preserves African traditions today.

Slavery was abolished in Colombia in 1851, but African Colombians continued to face economic hardship and discrimination. Today, they make up one of the largest African-descended populations in Latin America, concentrated along the Pacific and Caribbean coasts. Their cultural influence is profound, shaping Colombian music, dance, cuisine, and spiritual practices, while ongoing movements work for recognition, equality, and justice.

Children of Buenaventura #1

Photography by Aukram Burton Buenaventura, Colombia, 2018

On the shores of Colombia’s Pacific coast, the children of Buenaventura carry the echoes of Africa in their laughter, songs, and dances. Amid hardship, their rhythms rise like the tide voices of resilience, joy, and memory. In every step and beat, they honor their ancestors while dreaming of a brighter tomorrow. The children in #4 are playing a unique jump rope game called "Resorte-Chicle,” a traditional Colombian game. This game is played with an elastic band, requiring coordination, rhythm, and flexibility as the player navigates the elastic band at varying heights. Children leap through patterns inside a stretched band, which rises from their ankles to “heaven.” A test of rhythm, agility, and play.

Art, Struggle, and Identity in Buenaventura #2

Photography by Aukram Burton Buenaventura, Colombia, 2018

Buenaventura, Colombia’s main port and second-largest city in Valle del Cauca, has long been home to Afro-descendant, Indigenous, and campesino communities. Despite its cultural richness, the city faces persistent poverty, limited public services, poor healthcare, housing shortages, and educational challenges conditions that have deeply impacted daily life.

The walls and streets of Buenaventura are alive with vibrant mural art that conveys the rich African Colombian culture, including social commentary, historical characters, and cultural heritage. Throughout Buenaventura, walls are turned into political and historical showcases.

1. Temístocles Machado Rentería (Don Temis): This mural honors Don Temis, an African Colombian leader from Buenaventura who defended Black and Indigenous land rights and documented their displacement. A lawyer, activist, and member of the Civic Strike, he was assassinated in 2018.

2. Wake Up Time: This mural exposes Colombia’s legacy of racism, where colonial census systems ignored African Colombian identities and reinforced prejudice. It highlights ongoing debates about race and social inequality.

3. Fundación Tura Hip Hop: Founded in 2011, Tura Hip Hop is Buenaventura’s first hip-hop foundation, using urban culture for social change and youth empowerment. A local rapper’s anthem became the voice of the 2017 Civic Strike, which shut down the city’s port for 22 days.

4. Bridging the Gap in Education: The Vive la Educación (Live Education) program offers African Colombian students an ethnocentric model to close gaps, reduce illiteracy, and empower women. Here, students at Universidad del Valle engage with my exhibition Journeys in the African Diaspora

In Panamá, African heritage is deeply woven into national identity. Although 15% of the population identifies as African-Panamanian, nearly half of all Panamanians have African ancestry, shaped by two groups: descendants of enslaved Africans during the colonial period and West Indian migrants who came to build the Panamá Canal. Their communities, from Colón and Portobelo to Río Abajo and Bocas del Toro, remain vital centers of culture and tradition.

Aristela “Mama Ari” Blandón, cultural leader of Portobelo, teaches Congo dance to children, keeping alive the traditions of descendants of the Trans-isthmian Slave Trade. She embodies the espíritus ancestrales (ancestral spirit) to guide and inspire future generations.

Portobelo: Sacred Traditions, Living Culture #2

Photography by Aukram Burton Portobelo, Panamá, 2013

Portobelo, on Panamá’s northern coast, was once a major hub of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Today, the town is better known as the “Land of the Congos,” where African-descended traditions, spirituality, and cultural memory endure. Through faith, folklore, and community leadership, Portobelo honors its past while keeping its heritage alive for future generations.

1. Portobelo, Land of the Congos: Once a major slave-trading port, Portobelo’s history is often hidden behind myths of pirates and treasure. Today, it is remembered as the Land of the Congos, where African heritage and resistance remain at the heart of its identity.

2. The Black Christ, Portobelo: Every October 15, pilgrims from across Panamá gather at Iglesia de San Felipe to honor the Black Christ, a centuries-old tradition that reflects AfricanPanamanian faith and resilience.

3. Nolis Boris Góndola Solís: Author and cultural activist, Nolis Boris Góndola preserves maroon history and mentors youth through writing, education, and music in Portobelo.

4. Congo Mama Ari Performers: Members of Congo Mama Ari wear Pollera Conga attire, celebrating African-Panamanian folklore through music, dance, and storytelling.

African Descendants in Panamá #3

Photography by Aukram Burton Panamá City, Panamá, 2013

Beginning in the mid-19th century, thousands of Afro-Caribbean migrants from islands such as Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad came to Panamá to build the railroad and later the Panamá Canal. Their labor, communities, and cultural traditions continue to shape Panamá’s national identity today.

1. SAMAAP (Society of Friends of the West Indian Museum of Panamá): Founded in 1981, SAMAAP works to preserve Afro-Caribbean heritage and support the Afro-Antillean Museum in Panamá City.

2. The Afro-Antillean Museum of Panamá: Housed in a former Barbadian-built Christian Mission Church (1910), the museum documents the lives of West Indian immigrants who arrived to work on the railroad and canal.

3. Community Leadership: (R-L) Glenroy James, President of SAMAAP, with Melva Lowe de Goodin, scholar and former president of SAMAAP, alongside a colleague.

4–9 Calidonia Market, Panamá City: Scenes from the Calidonia market, a vibrant space reflecting the daily lives and cultural presence of African descendants in Panamá.

When I began my journey as a cultural photographer in Nigeria in 1979, I had no idea how profoundly it would impact my life. That first encounter with the living roots of the African Diaspora opened my eyes to the vast, interconnected web of traditions, rituals, and daily routines that have been carried across oceans and generations. Over the years, my camera has taken me to Ghana, Senegal, Benin, South Africa, Cuba, Brazil, Haiti, Colombia, Jamaica, Barbados, Panamá, and beyond each place offering new insights into the resilience and creativity of African-descended communities.

This exhibition, Journeys Through the African Diaspora: A Photographic Retrospective, 1979–2024, serves as both a record and a reflection. It captures sacred rituals and everyday moments, historic monuments, and contemporary struggles. My goal has always been to highlight the threads of cultural survival and transformation, showing how African heritage continues to shape identities and inspire resistance worldwide.

There are still places I long to visit to expand this story. Trinidad and Tobago, with its vibrant Carnival traditions rooted in African and Indian heritage; Mexico, where Afro-Mexican communities in Guerrero and Oaxaca continue to fight for recognition; and Australia, home to both African migrants and the rich history of Aboriginal peoples, who share parallels in resilience and struggle. I also want to explore Suriname, Belize, the Dominican Republic, St. Lucia, Guyana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia each with its own chapter in the African world story. The African Diaspora extends even further to places such as China, Japan, Canada, the United Kingdom, and France, where migration and identity are continually negotiated. The journey, truly, is ongoing.

For those who encounter my work, I hope it serves as more than just documentation. These photographs are intended to be tools for reflection and discovery. I encourage viewers to use them to ask questions about their own identities, histories, and connections. What does it mean to be African or of African descent in today’s world? How do traditions carried through the Middle Passage continue to thrive in music, dance, cuisine, spirituality, and community? How can we honor the struggles of those who came before us while imagining a future defined by dignity and unity? Educators can draw on these images to enrich conversations about history, culture, and social justice. Students can use them as starting points for research into their own heritage or into global struggles for equality. Activists may find in them a reminder that the fight for land, identity, and justice is shared across continents. And for members of the African Diaspora, I hope these images offer a mirror affirming both the diversity and the unity of our experiences.

The process of developing this exhibition has also brought me closer to a lifelong goal: publishing a book that gathers my photography into a comprehensive volume. Such a book will allow me to share a wider range of stories, images, and reflections than an exhibition alone can hold. It will be both an archive and a personal testimony a way of ensuring that these journeys, and the histories they represent, remain accessible for generations to come.

Ultimately, this work is about connection. The African Diaspora is not just a story of displacement; it is a story of resilience, creativity, and community across borders. By engaging with these images, I hope viewers leave with a deeper understanding of what it means to belong to a global African family and a renewed commitment to carrying that legacy forward.