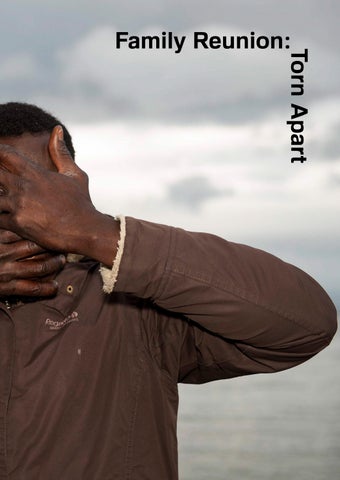

Family Reunion:Torn Apart

Family Reunion: Torn Apart

A project made in collaboration with people seeking asylum in Europe.

Text from Family Reunion Post-Brexit: No light at the end of the tunnel, a report published by Refugee Legal Support (July 2022) and spoken testimonies.

In solidarity with the people who risk so much in the hope of building a safe life on secure ground.

Photographs: Sarah Booker.

(left) Wall art, residential area. Patras, Greece. December 2021

(right) In the absence of safe routes many migrants are forced to make the irregular crossing across the Channel from the North coast of France to the South coast of England in small dinghies. France. October 2021

1 Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 4

(left) Wall art, residential area. Patras, Greece. December 2021

(right) In the absence of safe routes many migrants are forced to make the irregular crossing across the Channel from the North coast of France to the South coast of England in small dinghies. France. October 2021

1 Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 4

Family Reunification From Europe

The ability to be with our loved ones;

to spend time with them, to live with them, to eat with them and to go to sleep at night without worrying about them, is integral to all of our lives.

The importance of family cannot be understated, and the vital nature of communal and social ties for humans is something that all can recognise, in their lives and in the lives of others.

3

1

Limited opportunities for family reunion also exacerbates humanitarian crises

in countries such as Greece or Italy

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNHCR’s Response to the European Commission Green Paper on the Right to Family Reunification of Third Country Nationals Living in the Europe an Union (Directive 2003/86/ EC), February 2012), available online at https://www.unhcr. org/4f54e3fb13.pdf

Frances Nicholson/ UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), The “Essential Right” to Family Unity of Refugees and Others in Need of International Protection in the Context of Family Reunification, January 2018, 2nd edition, available online at https://www.refworld.org/ docid/5a902a9b4.html

British Refugee Council and Oxfam Joint Agency Briefing Note, Together Again – reuniting refugee families in safety – what the UK can do, February 2017, available online at https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ja-together-again-refugee-family-reunion-uk-280217-en.pdf

2 3 4 4

When families are suddenly or violently uprooted, the structures which provide individuals with comfort and community are ruptured.

2

Accessible and prompt family reunification procedures help to promote safe and legal avenues to safety for family members, thereby helping reduce their exposure to the dangers of irregular movement and reducing demand for smugglers and the risk of trafficking. 3

Home for two years to an undocumented Sudanese man unable to access support or employment in Greece since fleeing his country in 2018. He survives by washing car windscreens at traffic lights. Patras, Greece. December 2021

where displaced people arrive

in an attempt to join their families and end up trapped in squalid conditions, unable to exercise their rights.

4

(left) The twins. Derelict building and home to many unsupported migrants including children. Patras, Greece. December 2021 (next page) The twins.

Patras, Greece. December 2021

Extract taken from recorded conversation.

Zubair and Baseer

When Zubair and Baseer turned 10, their dad made arrangements to force them to join the Taliban. Their mother took the brave and distressing decision to sell her jewellery and smuggle them out of the country.

Suddenly ripped from their home, they had no one apart from each other as they made their way with smugglers over land. They eventually reached Turkey, where they worked in textile factories.

At 16, they managed to reach Greece. As with many other unaccompanied minors who have lost their childhoods to war and exploitation, they

were sent to the city of Patras. In Patras abandoned buildings are frequently used for shelter by unsupported migrants.

A ship leaves from Patras for Italy three times a week. Many migrants, including children, try to jump onto lorries to make it onto the ship, desperate to join family in Europe. Some have died trying to make this journey and several have been seriously injured.

The twins have survived living on their wits, relying on each other and young friends from their community.

7

(previous page) Road into port. Calais, France. October 2021

(left) Patras to Italy night crossing. December 2021

(right) Euro Tunnel, Folkstone to Calais. April 2022

(left) Patras to Italy night crossing. December 2021

(right) Euro Tunnel, Folkstone to Calais. April 2022

The dangers of irregular movement

Given the UK’s geographical position and the rising numbers of people faced with making a dangerous and potentially life-threatening crossing, family reunion is a key route to safe passage into the UK. 1

The tragedy of 27 people drowning in the Channel in November 2021 only serves to emphasise the real and present threats to life inherent

in being forced to enter the UK in this violent and perilous manner. 2

The report ‘Deadly Crossings and the Militarisation of Britain’s Borders’ estimates that

294 people have died at the British border with France between 1999 and October 2020.

Ferry from Calais. Dover, England. October 2021

Refugee Legal Support report, Family Reunion

From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, pages 4-5

Jamie Grierson, ‘Channel drownings: what happened and who is to blame?’ The Guardian, 25 November 2021, available online at https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2021/nov/25/ channel-drownings-what-happened-andwho-is-to-blame

Maël Galisson and the Institute of Race Relations, Deadly Crossings and the Militarisation of Britain’s Borders, 2020, available online at https://irr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Deadly-Crossings-Final.pdf

The devastating report, which seeks where possible to give an identity and a history to these ‘nameless bodies’ and ‘names without history’ contains many references to those who died crossing in an attempt to reach siblings or other family members in the UK. 3

1 2 3

15

(page before last) Jibi from Mauritania After he fled his country, Jibi witnessed countless acts of violence en route to Greece. With long periods without food or water, he and many others experienced the brutality of Libyan militias and had to pass through Syria during the civil war. He hid in forests and abandoned houses until crossing into Turkey and then onwards to Greece. His journey took him four years. Trapped in Greece, he lived in closed camp conditions with thousands of others on the move, enduring constant ID checks and intrusive surveillance.

Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

(previous page) View from the air.

December 2021

(right) S from Somalia. Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

SS was hounded by Al Shabaab and forced through extortion to pay money every month to Al Shabaab in order to protect his family including his parents.

One day his Mum told his Dad to go to the market and buy

fish for the family dinner. Al Shabaab blew up the market on that day and his Dad was killed in the market. S was able to identify his Dad only through blown up body parts next to the fish his Dad has bought for the family dinner. On arrival from Turkey to

Extract taken from recorded conversation.

20

Greece S hid in a forest to escape Greek police and militia who regularly hound ‘illegal’ arrivals in Greece to forcibly push them back in dinghies to Turkey and deny them the right to claim asylum in Greece. S successfully dodged them but was refused

his right to claim asylum in Greece on the basis that Greece said he should have claimed in Turkey and so his claim in Greece was ‘inadmissible’. S is still in Greece as he waits for the result of his appeal.

22

(left) As a non swimmer T from Côte d’Ivoire was terrified of open water. The rubber dinghy that he and others travelled in was intercepted in Greek waters by the Italian Coastguard working for Frontex. They rammed the dinghy which then began to sink. Assisted by 4 masked men they then transferred and packed all the people into a tiny dinghy, pushing it back into Turkish waters. They were rescued by the Turkish Coastguard.

Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

(right) Traveling with approximately twenty others, X from Côte d’Ivoire arrived from Turkey by dinghy to Lesvos and hid in a forest. They were hunted down throughout the night by people in balaclavas with dogs and torches. Gun shots rang out frequently. Together with W they made it to ‘new Moria’ where they registered their claim for asylum. The others were all captured, put on a dinghy and pushed back to Turkey.

Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

23

A lack of support in the country of application

Following the withdrawal of the UK from the EU in December 2020, the landscape of family reunion for those seeking asylum within Europe underwent a seismic shift.

Many families were left caught between two mechanisms of legal reunion,

without access to legal advice or representation, and without assistance to understand the requirements of so-called embassy proceedings —applications for entry clearance or leave to enter the UK via domestic legal provisions—

and in particular the narrow and prescriptive requirements of the Immigration Rules,

(previous page) Athens. December 2021

(left) Derelict building down by the port and ‘home’ to many unsupported migrants and children. Greece. December 2021

Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, pages 6,7

exceptionality

and the underpinning obligations of the Article 8 family life provisions of the ECHR. 1

which result in many applications having to be made outside the rules placing reliance on

1

27

(left) Hellenic Coast Guard for Frontex viewed from the main bus stop for Moria. The port of Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

(right) Ship moving across wall art in the port of Piraeus. Greece. May 2018

(left) Hellenic Coast Guard for Frontex viewed from the main bus stop for Moria. The port of Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

(right) Ship moving across wall art in the port of Piraeus. Greece. May 2018

(previous page)

Delves from Guinea-Bissau in the ruins of ‘old Moria’ camp. The camp burnt to the ground on 9 September 2020. An old military camp, it was transformed to house 3,000 migrants maximum. At the time of the fire there were 20,000 migrants living in the camp. Moria, Lesvos, Greece. December 2020

Delves

I am from Guinea-Bissau. I arrived in Lesvos with about 30 others in 2019 aged 17. I and a boy from Gambia were the only 2 Africans in the group and the only 2 to be detained.

The authorities tricked us and said they were taking myself and the Gambian boy to a hotel and instead they brought us to detention in Moria. I was 17 at the time but they said I was over 18.

We had to sign a paper in Greek to be detained. They said the detention was for 19 days but I didn’t understand anything as I spoke only Portuguese, Spanish and Fula then. The Gambian boy translated for me.

Every 19 days they renew the detention paper for us to sign so you don’t know for how long you will be detained or what you have done wrong. I

felt hopeless there with no future so I did some bad things. I had no idea how long I would be locked up for. I became sick - feeling sick all the time.

They took away our mobiles but every now and again we could use a fixed phone to make a local call. There were some good people outside who would give us sugar for tea, shampoo and sometimes clothes. I was in for 5 months.

This is what they do: drain you on arrival, find out the language you speak, can’t find an interpreter in that language so don’t do an asylum interview but instead prepare a rejection letter and after 2 months serve it directly to you in detention.. When they gave me my rejection letter they gave it to about 28 other Africans at the same time - all detained together. I was in detention for 5 months. Af-

32

ter I was released my appeal was suspended and I had my asylum interview in October 2020.

At that time there was much fighting in the camp. [A large group of people living in the camp] would attack blacks. They would come into our tents and containers and say “Africa give food, give money” and if you didn’t they would stab you. There wasn’t much police in the campmaybe 5 or 6 and they would walk around the edges of the camp not the centre. They were afraid of [the group] and we were black. They never helped us. In the time I was in Moria I had 3 friends killed from stab wounds [by this group].

One night I was coming back from the toilet at about 11/12 in the night and I saw 2 Somali guys talking to each other on my route back. [3 of the group] said to them “hey Africa give food” and when the Somalis refused [one of them] took out a big knife and stabbed one of the Somalis in 3 places including in the back. The guy fell down and

the other Somali ran away. I took the guy’s head - the one that had been stabbed - and put it on my leg. He said to me “[they] took my phone and money”. He was asking me for water. I have never seen that much blood before - it was pouring out of him like water. I started to cry. [They] shouted to me “Africa take him to hospital” I shouted at them “what the fuck are you telling me to bring him to hospital, why did you stab him”. I was crying.

One guy from DJibouti and 3 guys who had been sleeping in the mosque came to help me. The 4 of us carried him to the clinic by the gate of the camp but we could see his life passing. He was asking for water and getting very weak. I knew he was dying.

The security did nothing, they just looked on. The guy was dying and they did nothing, they didn’t call an ambulance. They were afraid of [this group] I was yelling at the police - I knew the same could happen to me tomorrow; I could die and the police wouldn’t protect us [Afri-

33

cans]. Other people came and started shouting at the police. They locked themselves in their office. Ten minutes later he died.

2 months later another Congolese guy was stabbed in the leg and they amputated his leg. When he woke up he went crazy but he died in hospital.

I have seen many things. [They] want our telephones so I carried a knife like other Africans because they knifed me for my phone. They take drugs and then they are not afraid. They follow us Africans to rob us. The police did nothing. If you live or die the police don’t care.

Maybe you heard of the case of Karamoko from Côte d’Ivoire. We were together in detention. Like me they said he was not 17 but over 18 so they locked him up. His claim was rejected in detention, his appeal made and then released. He was a professional footballer and played a lot in the camp when he came out of detention. He was a very gentle and quiet guy who didn’t

like groups . He would spend a lot of his time speaking on his phone to his family and he would go to mosque a lot.

So one night, a Congolese man and his wife went to a spot in the camp where there was wifi. [this same group] took his wife’s phone and he ran after them and caught the guy with the phone. He beat him and took the phone back. They then went and collected their group and came back for the Congolese guy and any Africans they came across. When they saw anyone black they fought them. So there was a big fight from about 8 - 12 midnight between [the group] and Africans. 4 Africans were stabbed.

We carried the Congolese guy to outside the gate and kept calling for an ambulance - none came. A Greek guy living near came with a small car and took the Congolese man and his wife to the hospital.

I went back to my tent and they had stabbed my friend who I shared the tent with and Karamoko. I went to Kar-

34

amoko’s tent and he was unconscious. They had stabbed him in the side. He had been sitting outside his tent speaking with his Mum on his phone and 5 [of the group] came to him. He said to his Mum let me call you back as there is a problem in the camp. He put his phone in his pocket and went to enter his tent and they stabbed him. He fell down on top of Ismail who was sleeping by the door and then they stabbed Ismail in the leg. When I got there, there were people there saying Karamoko is dying.

We carried Karamoko to the gate and waited 40 mins for another ambulance. 2 Africans had already been taken to hospital. When they put Karamoko in the ambulance he was trying to give me his brother’s number who lived in France but they wouldn’t let me. He and Ismail were both taken to hospital and Karamoko seemed ok. He was on his own with no others from [Côte d’Ivoire] in the camp. The Congolese guy had his wife and Ismail had friends from Burkina Faso but Karamoko had no-one.

Next morning Karamoko died and we had to call his Mum. She refused to believe us saying she was talking with him last night and he said he would call her back. She said she wouldn’t believe us until she sees the cemetery he is buried in.

‘The guy, Karamoko, had full energy, full dreams to make it in life, but he lost everything here. Many people they lost their lives here in Lesvos and some in this camp. Many people came here with good bodies and they don’t have problems with their bodies but after one year it’s bad. Life is temporary, of course my life is temporary. I have seen many things in my life and I am scared of nothing. I try to be good in the present.

The fight started here.

35 Extract taken from recorded conversation.

36

Smugglers’ lookout post opposite Patras port. Greece, December 2021

37

The Ukraine Family Scheme

In March 2022, the UK government’s response to the overwhelming need to support those fleeing Ukraine was to introduce the Ukraine family scheme. The Ukraine family scheme presents a version of family reunion where,

in an unexpected turn and in the face of public and political pressure,

efforts have been made to remove many of the barriers...

Examples of this include broadening the definition of family to encompass extended family members (siblings, grandparents, grandchildren, aunts and uncles, nephews and nieces, cousins) 1

residential area. Patras, Greece, December 2022

Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 38.

38 Street art,

1

and the immediate family of an extended family member [and] removing all application fees and waiving the need for sponsors to meet any maintenance or accommodation requirements; acknowledging the need for flexibility

around VAC (Visa Application Centre) attendance and VAC location; and allowing those successful under the scheme to work, study and claim benefits in the UK upon arrival. 2

It is evident from the concessions made in its own guidance that the Home Office clearly recognises the hurdles it places before those fleeing their country and seeking to join their family members in safety. 3

W from Mali arrived from Turkey by dinghy to Lesvos. W hid in a forest with more than 20 others he travelled with. They were hunted down throughout the night by people in balaclavas with dogs and torches. Gun shots rang out frequently. Together with X they made it to ‘new Moria’ camp where they registered their claim for asylum. The others were all captured, put on a dinghy and pushed back to Turkey. Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

Home Office, Ukraine Scheme Guidance version 4.0, 11 March 2022, available online at https:// assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/1060447/ukraine-scheme-guidance.pdf

Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 38

41

2 3

(previous page) Lwam Abraham. Pedion Tou Aeros Park. Athens, Greece. December 2021

December 2021

December 2021

(left) Road to the airport. Lesvos, Greece.

(right) The twins, Patras, Greece.

A familysystemreunification not fit for purpose

[The] reliance on a framework of integration means that displaced people and their ability to ‘integrate’ becomes the focus of any problem, obscuring the impact of violent and hostile societal structures.

...we do not believe that integration is an effective or appropriate unit of measurement through which to assess the state’s responsibility to unite loved ones and family members. 1

The fundamental problem is that the UK Government does not consider their loved ones to be their family, regardless of their bonds of love and belonging. 2

For this group, unless they are able to demonstrate compassionate and exceptional circumstances (which would undoubtedly require legal support), they have almost no possibility of having their loved ones rejoin them. 3

By limiting the possibilities of family reunion, and by enforcing a reliance on exceptional Article 8 arguments, sponsors are forced to make complex and arguably impossible decisions.

One practitioner commented that, in their experience,

“you see clients struggling with decisions about which family member to focus on, and which family member to bring.” 4

Kara

Lesvos, Greece. September 2018

Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 10

Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 12

Oxfam International, Safe but not Settled: The impact of family separation on refugees in the UK, January 2018, page 31

Quote given by a legal practitioner in the context of the Refugee Legal Support report, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 12

1 2 3 4

Tepe refugee camp.

(previous page) Asylum seekers prohibited from leaving the island of Lesvos, pending outcome of their applications. Port of Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece. September 2018.

(left) Ado at ‘home’. For two years, while his asylum claim was under consideration, Ado slept in a shelter by night in Pireus and walked the streets of Athens by day, despite his severe mobility challenges. From the Democratic Republic of Congo, he had his asylum claim and appeal refused. As a vulnerable person he was eventually put in temporary emergency accommodation by the International Organization for Migration, (IOM), where he lives now. Athens, Greece. December 2021

(next page) Night boat sailing out of Patras port to Italy. Patras, Greece. December 2021

50

A waste of human potential

“’As people who fled our country, who have faced discrimination, who have faced all of this difficult stuff and all this trouble on our journey, we expected some rest after all of this discrimination and difficulty and trouble. But here still, after all this time, I am in one country and my mum is in another country and I do not see any light at the end of the tunnel”. 1

Quote taken from Z’s interview for the Refugee Legal Support report, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 11

1 51

Notes

In December 2021, RLS initiated a pilot art project collaborating with people on the move. Together, we created images from personal accounts which reflected the experience of fleeing home, ‘landing’ in Greece, and the overwhelming experiences of navigating a challenging complex and broken asylum system.

. Many of the photographs reproduced here were taken in Lesvos, Athens and Patras. Running alongside the images is text from the RLS report “Family Reunion Post-Brexit: No light at the end of the tunnel” and from individual testimonies.

Frequently people gave accounts of the brutal enforcement of the illegal practice of pushbacks by Frontex and its ‘agents’. We heard countless stories of hiding in forests from armed police with dogs and from armed hooded vigilantes. These pushbacks from Greece to Turkish territorial waters

are on the increase and are a deliberate attempt to deny people their right to claim asylum, in direct contravention to the UN 1951 Refugee Convention.

Throughout Europe we see these pushbacks over land and sea borders preventing people joining loved ones, scattering and dislocating them across bounded territories unsupported, excluded and isolated.

During the course of producing this piece of work, we have seen the UK Government place migrants on a plane bound for Rwanda where we are told their asylum claims will be given full consideration. One by one, over a period of approximately 5 hours we saw people taken off the plane onto the runway at the Ministry of Defence Base near Salisbury and placed in Border Force vans. Those five hours on the plane, unable to contact lawyers, friends or family, waiting, not knowing, was

54

beyond an inhumane and excruciating stage in their journey to find safety.

The flight has for now been halted, pending the outcome of Judicial Reviews challenging the legality of the Rwanda offshoring policy, legitimized under the pernicious anti-refugee bill, (Nationality & Borders Act 2022), passed without regard for complete and consistent opposition.

What has happened to our humanity? We all share the very basic need to be close to our loved ones, to be together, and yet those who lead us tear them apart. We can no longer trust our Government to safeguard for us this most basic of rights.

This body of work was made possible by the expertise and comradeship of Elena Santioli, RLS caseworker embedded with Legal Centre Lesvos; Lucy Alper, RLS caseworker, Athens; Harry Harris, RLS caseworker, London and author of the report Family Re-

union Post-Brexit: No light at the end of the tunnel. Thank you to all of them for their insights and support. Thank you also to Lesvos Legal Centre for encouraging this work and working with RLS to make it happen.

Those people on the move who participated, not only gave support to the project but most importantly took a risk, sharing their experiences, images, reflections, and their pain, to shed light on the reality of this broken system. In some cases their identities have been protected for reasons of privacy and security, though in all instances there is consent to the use of images and testimonies. Respect to each and every one of you, we stand in solidarity.

Sarah Booker, Pilot Arts Project Developer, RLS. June 2022

55

All photography © Sarah Booker, 2023

Produced for Refugee Legal Support alongsie their report Family Reunification Post-Brexit: No light at the end of the tunnel (July 2022)

Design by Samuel Lanchin

Concept by Sarah Booker and Samuel Lanchin

To donate to Refugee Legal Support, visit www.refugeelegalsupport.org or scan the QR code below:

A project by Sarah Bookerwith Refugee Legal Support

(left) Wall art, residential area. Patras, Greece. December 2021

(right) In the absence of safe routes many migrants are forced to make the irregular crossing across the Channel from the North coast of France to the South coast of England in small dinghies. France. October 2021

1 Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 4

(left) Wall art, residential area. Patras, Greece. December 2021

(right) In the absence of safe routes many migrants are forced to make the irregular crossing across the Channel from the North coast of France to the South coast of England in small dinghies. France. October 2021

1 Refugee Legal Support, Family Reunion From Europe: No light at the end of the tunnel, April 2022, page 4

(left) Patras to Italy night crossing. December 2021

(right) Euro Tunnel, Folkstone to Calais. April 2022

(left) Patras to Italy night crossing. December 2021

(right) Euro Tunnel, Folkstone to Calais. April 2022

(left) Hellenic Coast Guard for Frontex viewed from the main bus stop for Moria. The port of Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

(right) Ship moving across wall art in the port of Piraeus. Greece. May 2018

(left) Hellenic Coast Guard for Frontex viewed from the main bus stop for Moria. The port of Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece. December 2021

(right) Ship moving across wall art in the port of Piraeus. Greece. May 2018