PRISMATIC VISION

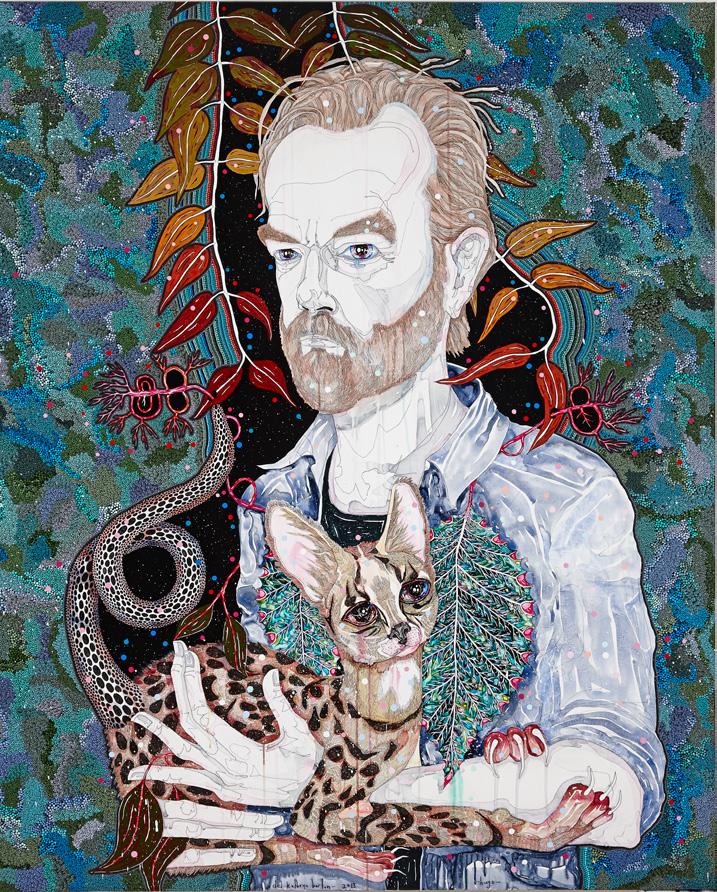

Artist Del Kathryn Barton on appreciating the still moments in a kaleidoscopic life and career.

At Kay & Burton, we’re drawn to those moments when potential becomes power and when emerging voices start reshaping the cultural landscape. Issue 11 celebrates these turning points— highlighting the dynamic energy of creatives, brands and business leaders who aren’t just participating in their industries, but redefining the rules with clarity and conviction.

Our cover story features twotime Archibald Prize-winning multidisciplinary artist Del Kathryn Barton (p22), whose boldly imaginative work has captivated audiences globally and positioned her as a defining presence in Australian contemporary art. Barton’s creative vision exemplifies the kind of artistic ascendancy that transcends geographical boundaries and speaks to universal human experiences.

Elsewhere within these pages we explore the meticulous restoration of New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel (p08), where celebrated French interior designer Pierre-Yves Rochon has revived the icon’s Art Deco heritage; we also visit the landmark Cartier exhibition at London’s V&A (p36), which provides a masterclass in luxury brand evolution; and hear from Melbourne menswear designer Christian Kimber on the evolving rules of dressing (p50). We also showcase some of the rising talent participating in this year’s Rigg Design Prize (p53), and venture to Champagne to discover how the president of one ultra-exclusive house has elevated scarcity into an art form (p17).

As always, The Luxury Report offers insights into the worlds of business, investment and property. In this issue, Michael Saadie draws on findings from NAB’s latest research to explore how small business succession planning is evolving, with new pathways to more flexible and impactful forms of legacy opening up (p13); Sally Auld’s economic outlook (p20) examines Australia’s strong position following recent global trade volatility, identifying key factors driving growing investor confidence; and we sit down with Australian entrepreneur, AirTrunk founder Robin Khuda, to examine the strategic foresight behind his extraordinary business success (p30).

We trust these stories will provide not only inspiration but practical perspectives as you navigate your own professional and creative endeavours. As always, we are eager to hear from you about the ascending stars, remarkable achievements and innovative thinking within your own network.

CONTRIBUTORS

NAB

Michael Saadie

Executive of NAB Private

Wealth & CEO JBWere

Sally Auld

NAB Chief Economist

Mark Browning

Head of Valuations & Property Advisory

Darian Kuzma

Private Client Executive

KAY & BURTON

Ross Savas

Managing Director

Peter Kudelka

Executive Director

Gowan Stubbings

Executive Director

Alex Schiavo

Executive Director

Scott Patterson

Executive Director

Tom Barr Smith

Executive Director

Jamie Mi

Partner & Head of International

EDITORIAL

Common State

Managing Editors

Luke McKinnon

Nick Kenyon

Editor

Leanne Clancey

Proofreader

Cathy Gowdie

Writers

Amelia Barnes

Peter Barrett

Alice Blackwood

Cameron Cooper

Kirsten Craze

Catherine Gillies

Freya Herring

Praachi Raniwala

Anna Snoekstra

Tyson Stelzer

Tomas Telegramma

Lucianne Tonti

Carlie Trotter

Adam Turner

Design and Art Direction

Amber Goedegebuure

Cover Image

Del Kathryn Barton

Photography

Saskia Wilson

Hair and Makeup

Gavin Anesbury

ADVERTISING

Nick Kenyon

Head of Luxury Strategy, Kay & Burton Telephone +61 3 9825 2554 nkenyon@kayburton.com.au

Level 7, 505 Toorak Road, Toorak, VIC 3142

The Luxury Report is published four times a year. Copyright © Kay & Burton. Printed by Neo, 5 Dunlop Road, Mulgrave, VIC 3170. The contents of this document (contents) have been prepared and are provided by Kay & Burton (which means and includes Kay & Burton Pty Ltd, its associated entities and its officers, servants, contractors, employees and agents) in good faith. Some of the contents have been provided to Kay & Burton by others. Kay & Burton does not represent or warrant the accuracy of the contents. The contents are provided solely for information purposes and do not constitute any recommendation, advice or direction by Kay & Burton for anyone to use any of the contents to make any decision about anything and in particular, about making any investment or participating in or acquiring, disposing, selling or purchasing anything or entering into any agreement, arrangement or dealing (whether legally binding or not). Kay & Burton recommends that any such decision should only be made following the receipt of advice from an appropriately qualified advisor.

BREAKING FROM TRADITION

Interior designer Pierre-Yves Rochon reveals how he masterfully revived New York’s iconic Waldorf Astoria, balancing careful preservation with elegant restraint.

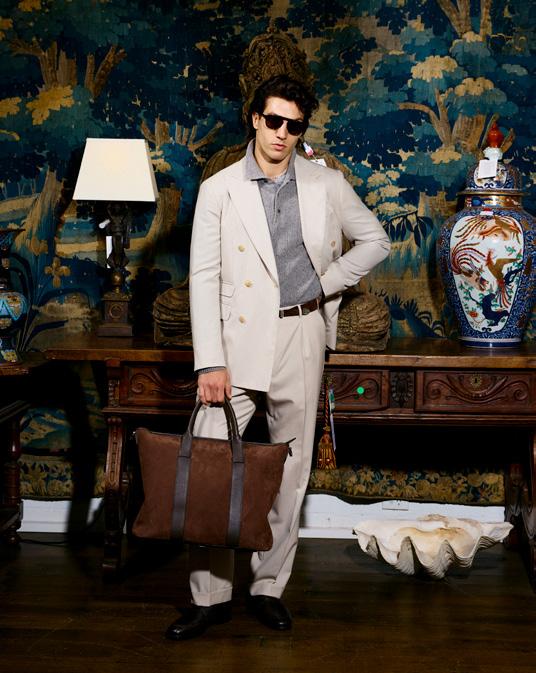

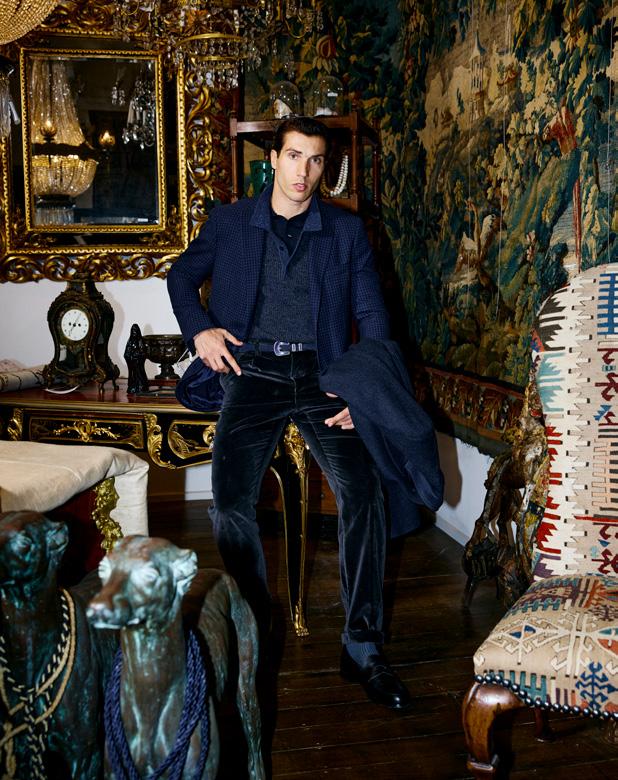

How British-born menswear designer Christian Kimber is weaving lifestyle considerations into formal suiting conventions to tailor the perfect fit for contemporary Australian men.

STILL MOMENTS IN A KALEIDOSCOPE LIFE

Archibald Prize-winning artist Del Kathryn Barton explores the early influences and deeply personal experiences driving her distinctive creative vision and path to international acclaim.

13 NAVIGATING THE HANDOVER

NAB’s Michael Saadie examines why flexible exit strategies are replacing traditional family business transfers.

17 A MODEST REVOLUTIONARY

Champagne Salon president Didier Depond explains how cultivating rarity has elevated the house to legendary status.

20 STRONGLY POSITIONED

As trade tensions ease, optimistic prospects emerge for well-positioned Australian portfolios.

30 CATCHING THE CURRENT EARLY

How data centre mogul Robin Khuda is now applying his infrastructure genius to craft dream homes.

33 THE NEW LUXURY CEILING

Why $10m-plus sales are now standard and what’s driving Australia’s prestige property evolution.

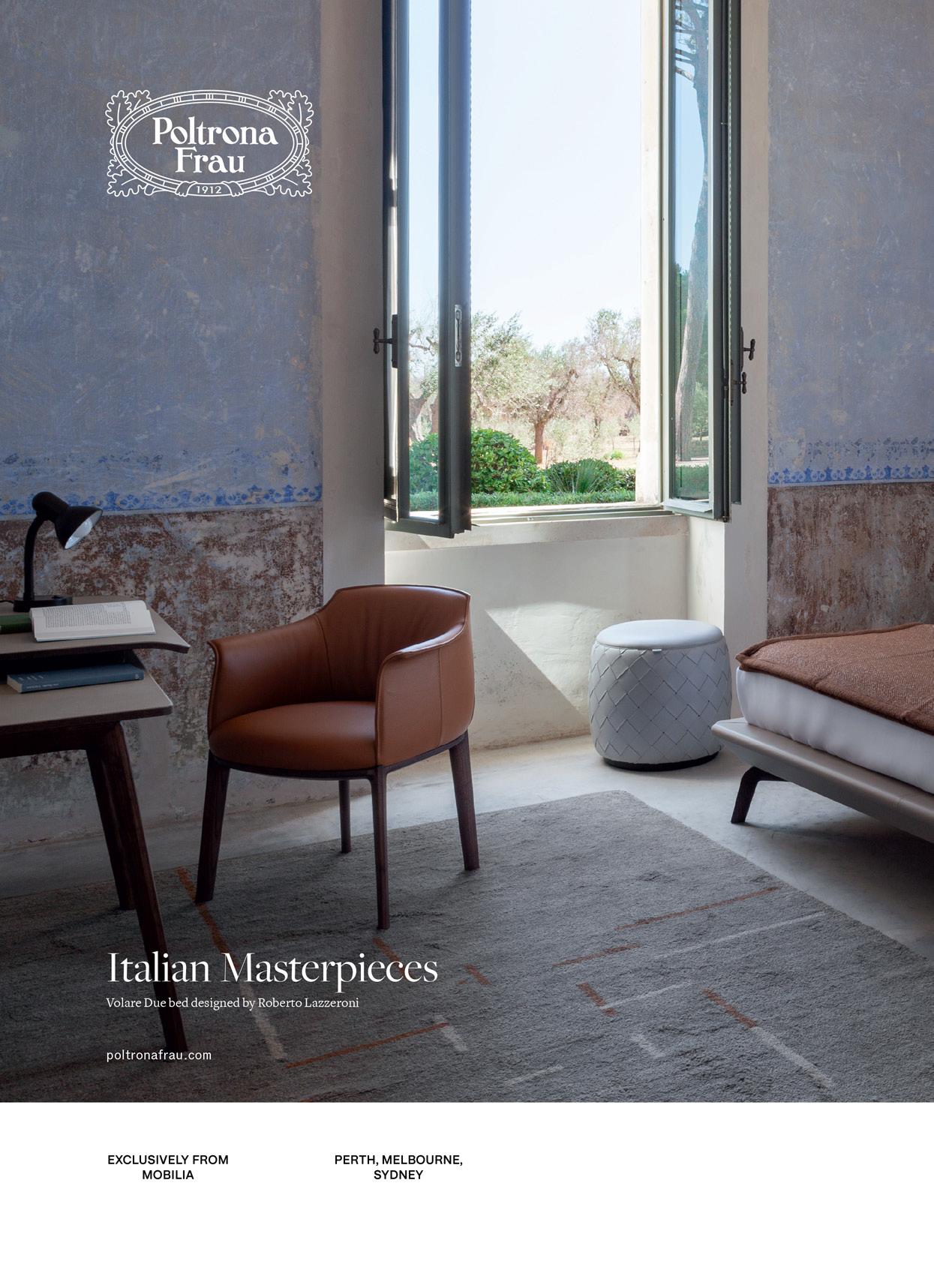

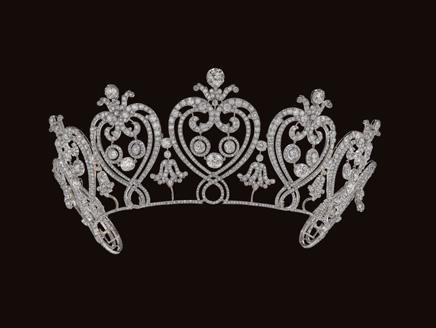

36 OF CROWNS, STARS & STONES

Step behind the scenes of the exhibition charting how Cartier became the jeweller of kings.

38 THE ETERNAL ENTREPRENEUR

Serial founder Nick Bell discusses his most ambitious project yet: engineering human longevity beyond 100.

41 GROWING CULTURAL CAPITAL

Explore the Melbourne garden project joining a worldwide movement in urban green design.

44 THE SEEKER’S EYE

Discover David Hicks’ 25-year interior design journey and the passionate collecting that fuels his creativity.

53 THE MAKING RENAISSANCE

Meet five rising stars spotlit by Australia’s premier design prize competition.

56 SOPHISTICATED SOUL

Inside chef Tom Sarafian’s debut restaurant where family tradition meets cultural heritage.

58 WHERE SPIRIT TAKES FORM

Trent Jansen on the role of collaboration and cultural immersion in his design practice.

62 OUT AND ABOUT

ornate Silver Corridor at the Waldorf Astoria, New York.

Kathryn Barton at her Paddington studio. Image: Saskia Wilson.

THE SHORTLIST

01 Almas modular sofa system by Knotte

A collaboration between Australian furniture brand Knotte and Melbourne designer Joanne Odisho (recipient of the 2023 Artichoke Emerging Maker Prize), this modular seating system embodies warmth through its generous proportions and signature indented cylindrical bolster backrest.

Named after Odisho’s grandmother, the collection bridges heritage inspiration with modern manufacturing. Crafted in Sydney, the system offers unlimited configuration through straight, curved, corner and ottoman components. Available in premium textiles including Kvadrat’s knitted Uniform Mélange, the system offers both comfort and visual sophistication. POA (subject to configuration). knotte.com.au

02 Atelier Art Deco Limited Edition audio system by Bang & Olufsen

Released to mark the Danish audio pioneer’s 100-year milestone, this home cinema collection reimagines the classic Beovision Theatre soundbar and Beolab 28 speakers with an Art Deco twist. Crafted from rosewood and chestnut-anodised aluminium, each piece features precision-machined geometric patterns with 100 engraved lines commemorating the brand’s centenary. Limited to 100 units worldwide, this fusion of heritage craftsmanship and cutting-edge acoustics elevates audio into collectible art. Available in select stores, POA (subject to configuration). bang-olufsen.com

03 ‘Where have all the flowers gone’ chair by Bieëmele

Conceived last year as a reflection on conflict and its recurring patterns, Melbourne-based maker Scotty Bemelen’s sculptural chair transforms recycled copper water pipes and salvaged timber into a quietly powerful meditation. Inspired by Bernie Boston’s 1967 Flower Power photograph, carved copper blooms emerge from patinated pipes, while the seat layers recycled Oregon, pier and messmate burl timbers with polished beach rock. Named after Pete Seeger’s ballad on history repeating, this handcrafted-to-commission piece feels especially resonant in 2025—a reminder of how design can echo the times while offering comfort. POA bieemele.com

Image: Mark Roper

05

04 Boss foosball table by FAS Pendezza

Designed by Milan’s Studio Basaglia Rota Nodari, this regulation-standard table shifts gaming into sophisticated design territory. The Boss combines post-industrial aesthetics with premium functionality, with its sleek black playing field contrasted against durable Iroko wood components. Every element reflects Italian premium gaming specialist FAS Pendezza’s century-spanning expertise. Available in a range of vibrant colours or bespoke finishes, this statement piece will command respect in any space. From $10,600. faspendezza.com

ALLTOTEM sculpture by Michael Young

British industrial designer Michael Young, whose work has been collected by the Louvre, Centre Pompidou and London’s V&A Museum, reimagines traditional Asian lanterns in his ALLTOTEM sculpture series. Where historical paper and silk lanterns symbolise prosperity across Asian festivals, Young’s 18 limited-edition pieces translate these meanings into polished extruded aluminium art objects featuring semi-random patterns. Drawing from his “complex minimalist” philosophy, these towering totems choreograph light and shadow, bridging Eastern cultural heritage with Western manufacturing to create what Young calls “industrial art”. From $22,500. galleryall.com

The

Park Avenue entrance at the Waldorf Astoria, New York.

Listening to legacy

In a city that never stops changing, New York’s restored Waldorf Astoria offers something radical: less intervention, more preservation, and a deep respect for architectural heritage—by Freya Herring.

Few hotels carry the weight of New York legend like the Waldorf Astoria. After a seven-year closure, it has reopened under the passionate guidance of French interior designer Pierre-Yves Rochon—and his passion for the project is unmistakable. “The building itself was the main inspiration,” Rochon says. “It doesn’t need decoration; it speaks on its own. The proportions, the rhythm, the materials, the Art Deco vocabulary—all of that was already present.”

Of course, this isn’t Rochon’s first rodeo—he has been responsible for reimagining many of the world’s great hotels, including Paris’ George V, The Savoy in London and The Peninsula in Shanghai. His history with this particular hotel heavyweight, though, spans decades. “My wife and I stayed at the Waldorf Astoria more than 30 years ago,” he says. “I remember walking through the hotel and saying to her, ‘One day, I would love to redesign this place.’ And years later, the opportunity came.”

The hotel, which dates back to 1893, was demolished in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building before reopening in its current Park Avenue incarnation in 1931 in a flurry of Art Deco flamboyance. Many illustrious decades followed, with guests from Queen Elizabeth II and Franklin D. Roosevelt to Marilyn Monroe and Frank Sinatra (who also lived there for several years) passing through its bronze-edged doors. By the 2010s the interior had grown tired, and in 2017 the hotel closed for refurbishment. Enter, Rochon.

“My wife and I stayed at the Waldorf Astoria more than 30 years ago. I remember walking through the hotel and saying to her, ‘One day, I would love to redesign this place.’”

“At the time of the renovation, the hotel was closed, of course, but its spirit was still very present,” Rochon notes. “It was a sleeping monument. You could feel the power of its past—the scale, the Art Deco geometry, the energy of New York in the 1930s. What we did was not invent something new; we brought comfort to what was already there. The architecture was already doing its job beautifully.”

The makeover of the Waldorf Astoria has been a labour of love. “The goal was to make it whole again,” Rochon emphasises. “And in a way, more honest— because comfort today is not the same as in the 1930s.” This objective was achieved through careful planning and a profound appreciation for the building’s original form. “This kind of building doesn’t belong to you. It belongs to the city. You’re just a caretaker, really,” he observes. “There was a sense of responsibility in restoring it with care and precision. Our role was not to reinterpret or overdesign—it was to let the building breathe again, and to bring back its original dignity with today’s standards of comfort.”

Luxury, through the Rochon lens, is not about decadence or extravagance. “Modern luxury is invisible,” he states. “It’s silence, comfort, discretion. Those things can—and must—be integrated into a historic building, but in a way that never disturbs its essence.” The hotel’s new iteration is a triumph of quiet luxury, with a palette of materials and tones that highlight and celebrate its 1930s heritage.

“The clock in the lobby remains exactly as it was,” notes Rochon. “There are also the main doors, the historic entrances, the mosaics in the floor—these elements are part of the collective memory. We didn’t need to reinvent them. We needed to care for them.” This meticulous care is evident in details like the lobby clock restoration, on which a team

01 The hotel’s fresco-lined Silver Corridor.

02 Cole Porter’s vintage Steinway piano takes centre stage in the glamorous Peacock Bar, set within the hotel’s soaring grand atrium.

comprising a master metalsmith, clockmaker and four conservators worked for almost a year, painstakingly restoring each component.

“We worked with preservation teams, with artisans, and above all, with the [hotel’s] history,” Rochon explains. “Every time we touched something, we asked, ‘Can we conserve it? Can we repair it? And if we must replace, how do we do it respectfully?’” The process was laborious, but for a building with such significance, it was also a vital endeavour. “There were many challenges, but we took the time. You don’t rush a building like this,” he maintains. “It’s like restoring a piece of music—every note matters.”

Sweeping changes converted the hotel from 1400 guest rooms to 375, with the smallest room measuring

twice the size of the hotel’s original rooms. There are also 372 privately owned condominium residences designed by Jean-Louis Deniot on the upper floors. “Many of the structural elements couldn’t be touched. We had to respect the historic envelope, while also introducing entirely new functions and layouts,” Rochon explains. “On the Park Avenue side, for instance, there were split levels and odd transitions that made orientation difficult. We had to find a new spatial logic within a protected shell. Another challenge was daylight, or the lack of it, in certain areas.” In response, a mezzanine was removed to bring back natural light that had been lost for decades, an entirely new lobby was created, and the ground floor sequence was reordered. “It’s not just about aesthetics,” insists

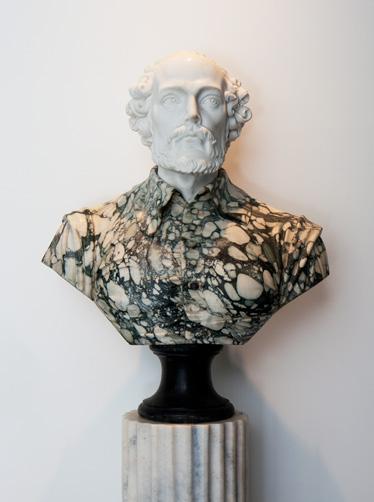

03 Anchored by an ornate central chandelier, the restored ceiling of the Basildon Room features 24 paintings inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy

04 French interior designer Pierre-Yves Rochon.

Rochon, “it’s about restoring logic and clarity to the flow of the space.”

The sense of clarity extends into the hotel’s colour palette, which is often pared-back and almost celestially pale. In a relentlessly loud and hectic city like New York, it’s an approach that feels like a welcome tonic to the fray. The bedrooms encapsulate this—soft, tactile fabrics that both soothe the spirit and muffle the noise, a prominence of cream and white tones, and decor that is both minimal and considered. As with much of Rochon’s oeuvre, there is the sense, if not the reality, of diamonds— glittery moments flickering in the light. Like a diamond’s cut, the design appears simple from a distance but upon closer inspection reveals the rich detail and craftsmanship it took to shape it.

The hotel’s Silver Corridor and Grand Ballroom have been restored to their magnificent states, but the newly reinstated Peacock Alley offers a moody contrast—dark and richly textured with maple burl wood

panelling, blue carpets and ornate ceilings. Stretching from Park to Lexington Avenue, it is named after the fabled corridor which linked the former Waldorf and Astoria hotels after they merged in 1897. Back then, patrons would promenade between the buildings, ‘peacocking’ the latest fashions and establishing themselves as New York’s most fashionable set in doing so.

Its new manifestation honours the original by reintroducing materials from the initial designs, such as Portoro marble. “It’s a rich black marble with golden veins, typical of the 1930s,” Rochon says. “It gives a sense of rooted elegance.” Facets that couldn’t be saved were sympathetically replaced. “We couldn’t save the original carpet in Peacock Alley,” he explains. “We created a new carpet as a reinterpretation, drawing from archival motifs.”

Historic pieces take pride of place: a clock commissioned by Queen Victoria in 1893, and the

grand piano gifted by Cole Porter, who lived at the hotel for some three decades. Bronze accents, too, were brought back. “Always with a patina; never shiny,” notes Rochon. “This project was less about introducing new materials than about restoring existing ones. The soul of the Waldorf Astoria was already there, we just helped it re-emerge.”

Rochon hopes that this approach could mark a way forward for future grand hotel renovation. “We don’t need to constantly invent,” he says. “Sometimes, the most powerful gesture is to listen to the building, to trust its original language, and bring it into the present with precision. That kind of integrity, I think it’s what guests are looking for now. Not noise, not novelty—but truth.”

05 Living room space of guest suite with Park Avenue view.

The Waldorf Astoria will make its Australian debut in Sydney in late 2026.

NAVIGATING THE HANDOVER

As nearly half of small business owners approach their final decade at the helm, Australia is bracing for a historic transfer of ownership that will test succession plans and family readiness—writes Michael Saadie, executive of NAB Private Wealth and CEO JBWere.

Across the business landscape, an evolution has begun. The traditional dream of building a business to pass down through generations is dissolving and being replaced by something more complex. Our latest research report, conducted with market intelligence firm CoreData, reveals that only 39 per cent of small business owners expect their children to take the reins—a seismic shift from the succession ambitions that once defined business ownership.

This is not merely statistically significant. With small businesses (defined as those employing fewer than 20 people) accounting for a third of national GDP and employing over 5.3 million people, we are witnessing a reimagining of how wealth, purpose and legacy intersect in modern life. The implications go beyond balance sheets into how we define and conceive success, retirement and family prosperity.

BECOMING UNANCHORED

Within the wealth management sector, conversations are evolving. Where we once discussed tax structures and asset allocation, we now find ourselves grappling with questions of identity, purpose and fulfilment.

One client recently described selling their business to a US private equity firm as “like winning the lottery”, but that excitement was overshadowed by disorientation and a peculiar sense of mourning. After two decades building a 12-person operation into a thriving global enterprise with more than 120 employees, they found themselves

untethered. The business was not just their wealth creator, it was their daily driver and social ecosystem. While these discussions consume our advisory sessions, the policy response remains behind the curve.

The numbers tell a sobering story: nearly half of Australian small business proprietors are aged over 50, with 22 per cent just five years from pension age. Even so, only 34 per cent have a documented succession plan. Another 31 per cent have discussed plans without formalising them, while 20 per cent keep their intentions entirely to themselves. This is not procrastination—it is paralysis in the face of fundamental questions that numbers alone cannot answer.

THE PULL OF DIFFERENT TIDES

Why are the children of successful businesspeople increasingly stepping away from the family business? The answer lies partly in the vast range of alternatives that beckon from every corner of our evolving economy. The tech sector’s appeal, with its promise of scale, offers emerging talent the chance to build billion-dollar valuations without the decades of hands-on management that their parents endured.

With young professionals drawn to inner-city innovation hubs, the industrial and regional areas where many family enterprises operate feel increasingly remote, geographically and culturally. The inherited logistics company in the suburbs, however successful, struggles to compete with the allure of a CBD startup or global consulting firm.

We are also witnessing a generational shift in how success is defined. Where their parents measured achievement and success in revenue growth and market share, millennials and gen Z prioritise flexibility, purpose and impact. The prospect of inheriting the family firm can be less appealing than launching a sustainable fashion brand or joining a climate tech venture, for instance.

HALF-SPEED AHEAD

Traditional retirement—that significant moment when one stops working entirely—is becoming as outdated as the farewell morning tea. Our research reveals that 54 per cent of small business leaders plan to be partially retired but working by choice at 67, with another 29 per cent expecting to work full-time by choice. This is not driven by financial necessity, but by something more fundamental.

I call this ‘punctuated retirement’: a deliberate, flexible transition that maintains intellectual and social engagement while shedding the management burden. It is about preserving what energises while removing what exhausts. Most of the survey participants cite intellectual stimulation as their primary motivation, with enjoyment and purpose close behind.

This shift demands sophisticated wealth strategies. At NAB Private Wealth, we are seeing clients design complex structures that allow them to retain strategic involvement while delegating day-to-day control. They are building portfolios of non-executive directorships or channelling their expertise into philanthropic initiatives.

SPREADING THE SAILS

Perhaps no challenge is as acute as the ‘empire mindset’ that keeps wealth dangerously concentrated. Business owners naturally gravitate toward what they know, often maintaining most of the family wealth within their company. It is familiar, it is controllable, and it has worked so far. The burden of being solely responsible for revenue has also made many afraid to look beyond the business. But this concentration creates its own challenges.

The adviser’s role has transformed from simply recommending diversification to becoming a translator between the familiar and unfamiliar. We must explain how a diversified portfolio spanning public markets, property and alternative investments provides not only risk mitigation but also the liquidity needed when the next generation requires capital for their own enterprises or property purchases. This is particularly critical given that over half of businesses with revenues exceeding $200,000 hold commercial property or high-value assets, often illiquid and difficult to partition among beneficiaries.

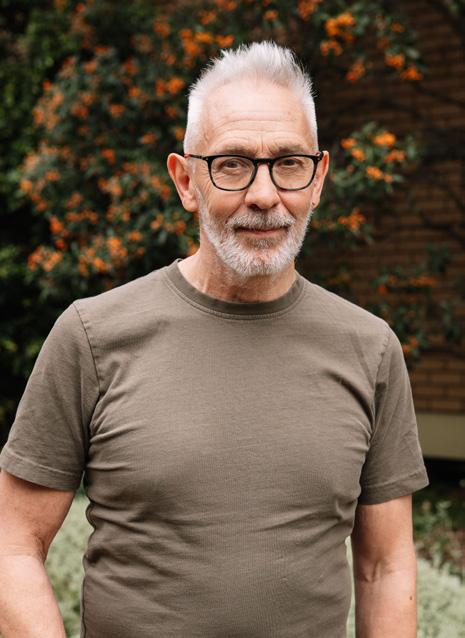

Michael Saadie, Executive, NAB Private Wealth and CEO, JBWere.

CHARTING THE COURSE

The key is starting important succession conversations years or even decades before handover. When company structures are properly established from inception—with clear separation between personal and business assets, appropriate trusts and tax-efficient vehicles—the eventual transfer becomes more seamless and less complex.

Family discussions should begin early, allowing friction points to surface and resolve well before any transfer of leadership or the commencement of sale negotiations. Through our private banking network and JBWere’s family advisory services, we facilitate these often sensitive discussions in confidential settings where discretion is paramount. We also host networking events which bring together business owners facing similar transitions, creating safe spaces for sharing experiences and strategies.

With a quarter of businesses set to close upon their owners’ retirement, we are witnessing the end of automatic succession and the beginning of something deliberate and meaningful. Modern legacy surpasses company continuity, extending to embrace philanthropic endeavours, impact investing and social enterprise.

This legacy planning process begins with essential questions: What is the purpose of this wealth? What world do we want for future generations? Once families answer these questions, many discover new paths forward. We observe founders channelling their entrepreneurial energy into venture philanthropy and multigenerational foundations to create new forms of family unity without shared business operations.

Employee buyouts are among the solutions now emerging, allowing executives to reward loyal teams while ensuring business succession. These structures preserve local employment and community engagement while freeing founders to pursue new challenges. It is inheritance reimagined, enabling future prosperity rather than dictating its terms.

PREPARING FOR THE WAVE

Looking ahead, we face an unprecedented wave of ownership transfers. With the number of small businesses having doubled over the past 25 years to 2.6 million, and baby boomers approaching retirement en masse, we need robust infrastructure to facilitate smooth succession.

This requires creating frameworks that support emotional, financial and practical transitions simultaneously.

The current reality, where only 30 per cent of small business owners maintain ongoing relationships with financial advisers, suggests many people are incredibly underprepared. The complexity of 21st-century succession demands coordination across private banking, wealth advisory, tax planning and family counselling. NAB Private Wealth brings together business bankers, private bankers and wealth advisers from the very beginning. This collaborative, end-to-end approach, supported by JBWere’s investment advisory, nabtrade’s self-directed platform and NAB Ventures’ innovation ecosystem, helps ensure seamless support across business, financial and personal planning.

We also recognise that women will be among the largest beneficiaries of the upcoming wealth transfer. This drives our continued investment in female advisers, who are a critical part of our team and well placed to serve this demographic.

CATCHING NEW WINDS

In working with and supporting entrepreneurs, I have observed that many find their post-exit ventures more fulfilling than their original businesses. Freed from daily pressures and armed with capital and experience, they are funding innovation, backing tomorrow’s leaders and pursuing meaningful causes with characteristic determination.

Rather than viewing the move away from traditional succession as a negative trend, we see important progress toward increasingly flexible and impactful forms of legacy. For those willing to plan early, diversify thoughtfully and reimagine retirement, this transition represents not an ending but a beginning.

Our thoughts around succession are changing because the world is changing. The question is not whether to adapt but how quickly and thoughtfully we can build new models that honour both achievement and aspiration, serving not just the generation that built wealth, but also those who will build differently.

In this great unbundling of business and family, opportunities abound.

Read the full Beyond the Business: Navigating Retirement and Succession for Small Business Owners report at business.nab.com.au/life-beyond-your-small-business.

This article has been prepared by National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937 AFSL and Australian Credit Licence 230686 (NAB). The information contained in this article is believed to be reliable as at September 2025 and is intended to be of a general nature only. It has been prepared without taking into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on this information, NAB recommends that you consider whether it is appropriate for your circumstances. NAB recommends that you seek independent legal, property, financial and taxation advice before acting on any information in this article. All products and services mentioned in this document are issued by National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937, Australian Credit Licence and AFSL No. 230686 (NAB), except wealth advice services, which are provided by JBWere Limited ABN 68 137 978 360 AFSL No. 341162 (JBWere), and nabtrade, which is the information, trading and settlement service provided by WealthHub Securities Limited ABN 83 089 718 249 AFSL No. 230704 (WealthHub). WealthHub and JBWere are wholly owned subsidiaries of National Australia Bank Limited (NAB). WealthHub’s and JBWere’s obligations do not represent deposits or other liabilities of NAB. NAB does not guarantee its subsidiaries’ obligations or performance, or

A modest revolutionary

Under Didier Depond’s quiet stewardship, Salon has become champagne’s holy grail; a small luxury brand that punches far above its weight in the shadow of its seven-millionbottle parent company. Here, the man behind the mystique explains how humility built an empire—by Tyson Stelzer.

When Didier Depond was first offered the presidency of Champagne Salon over the phone nearly three decades ago, his first response was to ask his boss if he was drunk. All these years later, he oversees some of Champagne’s most exclusive and expensive bottles—fewer than 50,000 per vintage, each one coveted by collectors across the globe.

The year was 1997, and 33-year-old Depond was on assignment hosting a tasting abroad, having spent 11 years working his way up from a salesman to marketing director of Champagne Laurent-Perrier. The late Bernard de Nonancourt, then-owner of Laurent-Perrier, was on the line from Italy offering Depond the role.

Within a week, Depond was back in the home of this fabled house in the Champagne grand cru village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, assuming responsibility as president of Salon Delamotte. The role would have him oversee both houses: the ultra-rare Salon, which releases vintages only in exceptional years, and Delamotte, the more accessible champagne house founded in 1760. Under Depond’s guidance over the past 28 years, Salon has risen to become one of the most sought-after champagnes globally, with the street price effectively tripling in less than a decade. But it wasn’t always this way.

“Thirty years ago, Salon Delamotte was not what it is today,” Depond recalls. “It was a little bit difficult, following ownership by Pernod Ricard, so it was not very famous and did not have a good image. I slowly started to rebuild the houses.”

It’s no simple calling to manage a small luxury brand under the broad umbrella of a large owner. Laurent-Perrier

produces close to seven million bottles annually, while the recent release of fewer than 50,000 bottles of Salon 2015 represents just the 45th vintage since 1905.

“There are some examples of luxury products where they are no longer the same volume and no longer the same quality. But for the past 28 years, I have never, never, never increased the volume,” Depond emphasises. This is no small feat for a brand for which he estimates demand outstrips production 100-fold.

“It was very simple with Bernard [de Nonancourt]—no big strategy or crazy ideas. The only point that he emphasised repeatedly was, ‘You have time to do the best.’ Money was never a problem, and he always told me to take my time. ‘If you decide it is not the right vintage for Salon, it is your decision,’” the Laurent-Perrier veteran had told Depond.

It was this freedom that gave Depond the confidence to take on the role, despite his youth at the time. “I remain extremely free,” he explains. “And if this were not the case, I would not be in the company any longer.”

While giving Depond the autonomy to define his own role, de Nonancourt’s mentorship proved formative. “He was like my second father,” Depond reflects today, “an incredible man, a master, a direction to follow. He was close to two metres in stature, like a mountain, a rock. And he was super kind, super sweet and super strong. He was a role model for

05 The gates of Salon House, in France’s Côte des Blancs. Image: Leif Carlsson.

01 In its quest for perfection, Champagne Salon produces an average of just three to four vintages per decade.

02 Didier Depond, president of Champagne Salon and its sister house Champagne Delamotte. Image: Leif Carlsson.

03 Champagne Salon’s Blanc de Blancs style uses chardonnay grapes sourced exclusively from the grand cru village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger.

04 Wine critics consider the 2004 Champagne Salon among the greatest vintages of the past two decades.

me. I am small and I am not very intelligent, so I tried to follow him,” he laughs.

Depond, of course, is much smarter than he admits, and is due credit also for the rise of Salon’s sister house, Delamotte. “The two houses are like my right and left hands, my balance,” he says. “Salon is the superstar, but like my two children with two different characters, I love Delamotte [equally].”

When Depond took the helm, Delamotte produced just 200,000 bottles annually, mushrooming to one million today. In an era when it is popular for champagne houses to increase the diversity of their offerings, Depond courageously bucked the trend by streamlining the Delamotte portfolio to just five cuvées. “This has not been a problem for us,” he reveals, “because when the market is difficult, it needs something that is clear.”

Meanwhile, Salon continues its dizzying upward spiral. “Thirty years ago, it was all about the bubbles,” Depond says, “and now champagne is seen as a great wine with bubbles, with perhaps even greater potential for ageing than other wines.” The transformation extends beyond perception to market dynamics. “We drink champagnes at 50, 70 or 90 years of age and they are still perfect. When I started [working] in Champagne 40 years ago, champagne was never in auctions.”

The turning point came roughly five years ago when an investment article appeared focusing on blue-chip wines like Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and Petrus. “At the end of the article, it said, ‘If you want to make money fast, invest in Salon, because it is under the radar,’” Depond recalls. “After this article, the demand increased dramatically.” While he now works with auction houses, Depond maintains perspective: “This is not the priority for me. Auctions are good for the image, but not for day-to-day business.”

For all he has achieved in his tenure, Depond remains unassumingly reflective. “My legacy at Salon and Delamotte, and in my personal life, is that I want to be the most discreet for those coming after me. I am not pretentious enough to believe I must leave something. I have spent 28 years at Salon Delamotte, and maybe I will have five or 10 years more, and I will continue to work like this... and the next person will do it differently.”

It’s a mindset rooted in accepting constant change. “The last 30 years were different from how the next years, months and weeks will be,” he notes. “So, my focus is not on my legacy—what happens in 10 years is not important to me. Tomorrow is important, the next harvest is important. We will be very disappointed if we focus on 20 years. We need to be much more focused on the reality of the present.”

STRONGLY POSITIONED

As global trade war fears subside, Australian investors are primed for their next strategic moves in a brightening market, writes NAB chief economist Sally Auld.

Two years of economic uncertainty are finally giving way to measured optimism. With minimal impact to date from the Trump administration’s tariffs and global market volatility easing, Australia’s economy appears poised for modest growth in the next 12 months. High net worth Australians have, for the most part, weathered the storm well over the past two years as low debt levels and high interest rates have worked in their favour. This cohort has helped sustain Australia’s consumption levels, and now, on the back of rising market confidence and strong asset prices, there is seemingly little to stop the spending of these hard-earned dollars in 2026.

The July 2025 NAB Monthly Business Survey also pointed to companies feeling slightly more optimistic about the future, adding to hopes of a positive shift in Australia’s macroeconomic trajectory. We expect GDP growth to return to trend during 2026, while unemployment is forecast to rise only modestly, peaking at 4.4% by the end of 2025. Inflation, meanwhile, is looking likely to settle at about 2.5%, aligning with the mid-point of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s target range. However, the RBA remains cautious. NAB is predicting two more rate cuts by February next year, bringing the cash rate to 3.1%. There is also optimism that Australia’s reliance on government spending will lessen, with an invigorated private sector leading a new growth phase.

NAVIGATING GLOBAL HEADWINDS

While Australia remains sensitive to external developments, the economy seems to be turning the corner. Earlier this year, markets were fretting about the impact of the Trump tariffs and global trade disruption. While the long-term implications of American trade policies remain unclear, the US economy continues to tick along, and concerns about a full-blown trade war are diminishing.

Australia is well placed to weather any international volatility. We have largely avoided punitive US tariffs, inflation is under control, and the RBA has the capacity to cut interest rates as a stimulus measure if it so chooses. In short, the worst seems to be behind Australia, and there are some encouraging dynamics for the economy as it enters the second half of the year. As high-income households continue to increase discretionary spending and weigh up smart investments, there is a growing sense of optimism.

REVIEWING PORTFOLIO STRATEGIES

With conditions stabilising, asset allocation is again the focus for sophisticated investors. Equity markets, including the S&P 500, have enjoyed an extraordinary run, and key stock exchanges are sitting on or near record highs. As a result, the risk-reward equation for investors has shifted, and it may not be the right time to go hard on equities.

Our colleagues at JBWere are advocating for more defensively positioned portfolios, adding that fixed income generally offers attractive risk-adjusted returns. While pockets of value remain in equities, especially in healthcare and energy, there is a risk of being overweight in this asset class, and any new equity exposure requires careful consideration.

This applies to offshore allocations too, with JBWere cautioning against rushing into US-dollar assets after a decade or more of equities outperformance. Bringing capital home or targeting underweight options such as Japan, Europe or emerging markets may deliver better value. For instance, Southeast Asia continues to appeal, with strong demographic trends and favourable fundamentals creating long-term investment potential.

THE AI ‘ARMS RACE’

The latest data from global technology company Capgemini shows that the total wealth among Australian high net worth individuals rose 3.3% in 2024. With more money at their disposal, investors may increasingly consider opportunities in the artificial intelligence

space—a theme that is dominating capital markets.

Some AI front-runners are engaged in aggressive capital expenditure across R&D and business development, in contrast to a few years ago when companies prioritised lean operations to generate healthy cash flow. This new AI ‘arms race’ has created an environment that is ripe with opportunity, but not without risk. The burden of proof is on firms to demonstrate to investors that the vast sums of money being spent are likely to yield decent returns.

History tells us that only a few winners emerge from periods of aggressive expansion, with the rest often struggling to compete. During the next 18 months, these AI and technology companies will need to validate their strategies through strong financial performance.

HIGH-END PROPERTY IN FAVOUR

There has been a clear upswing in luxury property sentiment on the back of sustained house price growth and recent RBA rate cuts. New records for property sales around Australia, including existing dwellings and yet-tobe-built penthouse apartments in Sydney and Melbourne, highlight the confidence in the luxury property market.

Top earners appear to be allocating more capital to prestige real estate, viewing the asset class as a long-term wealth builder and a hedge against inflation. Such interest is being reinforced by likely changes to superannuation tax rules. The Australian Government’s move to lift taxes on super balances exceeding $3m is prompting some individuals to diversify wealth outside traditional retirement accounts, with premium property emerging as a preferred option. The segment is proving resilient, with declining borrowing costs and strong foreign capital inflows expected to support ongoing strength in high-end real estate markets.

TEMPERED EXPECTATIONS

While much of the hysteria around US trade policy has started to die down, it is worth acknowledging that economies and investors are experiencing historically unusual events. With this in mind, we do need to keep an eye on markets and any left-field developments, or what we economists like to call ‘non-linear effects.’

US fiscal conditions remain concerning and have the potential to unsettle global markets, and we do seem to be living and investing in a world that is less stable and more fractious than in the past. Amid brightening domestic conditions, there is still a need for vigilance and for investors, the importance of diversification, flexibility and robust risk management may be greater than ever.

STILL MOMENTS IN A KALEIDOSCOPE LIFE

Known for her maximalist and hyper-detailed artworks, Del Kathryn Barton joins the dots of her evolution into one of Australia’s top contemporary artists—by Anna Snoekstra.

Del Kathryn Barton is tired, but that won’t stop her.

She speaks to me from her Paddington studio, in Sydney’s leafy inner-east, her hair piled high and her outfit a magic eye of layered patterns. The space around Barton is overflowing with colour, paint splatter and empty easels. The huge paintings, drawings and sculptures themselves are gone.

The day before, she had shipped an exhibition of new work to Korea, for her outing at Frieze Seoul with Melbourne’s Station Gallery—a deadline that came within a week of sending off work for a return show at Albertz Benda in New York titled the more than human world

I’m instantly curious about the way she titles her works, always in lower case and often expansive. Barton tells me she chooses lower case because, in her words, “I want there to be a sense that there’s no real beginning and no real end. [The titles are] these poetic bubbles of text floating around the practice that can offer moments of potential connection or interpretation without it being fixed.” She resists the pressure on artists to offer direct explanations of their art, but offers: “The essence of my work, the female protagonists

and the worlds that they inhabit are very heightened. There’s a strong sense of humanity, but it goes beyond the everyday.”

I ask Barton if she’s planning to take a break to recover after these big milestones, especially with a new book of her work being released with Station in coming weeks, but she gives me one of her signature explosive laughs. She’s just signed on for another show in Miami. For Barton, her art practice isn’t something she wants or needs a break from— it’s what gives her energy. “I’m not an artist who ever has creative blocks,” she explains. “If anything, there are just too many ideas and the constant desire to make. It’s about the challenge of grounding that [impulse] and not feeling overwhelmed. My brain and my sensory experience of being human are very, very fertile.”

Digging deeper into her practice, she says: “This fertile quality and my maximalist aesthetic, and experience of inhabiting a female form, is all very layered and dense and complex. I think, for me, bringing that down to a single image is enormously challenging, but it gives me a lot of calm as well,” she explains. “I love to think about

01 Del Kathryn Barton’s unique vision has transcended Australian boundaries to capture global attention. Image: Saskia Wilson.

02 Still from Barton’s film, The Nightingale and the Rose, 2015. Image: Aquarius Films.

the paintings as being like the centre of a spider web; a distilled moment that lots of different narrative and sensory experiences extend from.”

We discuss this idea of distilled moments from which so much colour and story can expand, and I ask Barton if she can think of any such moments from her own life: moments that have transformed her as a woman and an artist. “I’m 52 now,” she says, “so you can look back, and you can join the dots, you know, to find coherence. Living it is just the big, messy experience of being human every day.”

“Living it is just the big, messy experience of being human every day.”

The first moments that began her practice were incredibly difficult ones. As a child, Barton lived with her parents and two siblings in tents on a huge 20ha property in the lower Blue Mountains, surrounded by 200ha of forest. She experienced debilitating episodes of auditory and visual hallucinations. Her mother, a committed Christian and Steiner school teacher, went to a series of alternative healers to help her daughter. “No one really knew what was happening. My mother, in the end, when I was having an episode, just encouraged me to draw in those moments.” Barton would feel disembodied during these episodes, but the act of drawing helped her become present. “It was a way of coming into my body and feeling safe, and just getting the energy moving through, and distracting the fear place of the mind with the act of creating something. That’s a life-giving space; a regenerative space; a space of joy and possibility. I use my practice in that way to this day, even though it’s a professional studio. I have staff, I have deadlines, blah, blah, blah. Still, it’s the life-giving force that drives my concerns.”

I ask her how this experience connected to the next significant moment of her creative evolution: art school. She admits the contrast was tough. “I left home when I was 17,” she says. “I was very innocent. I wasn’t streetwise at all. And I moved to [Sydney’s] Newtown, the inner city.” While the program exposed her to groundbreaking artists she deeply admired—including Joy Hester, Louise Bourgeois, Jenny Watson and Sally Gabori—the institution’s conceptual emphasis clashed with her more intuitive, process-driven artistic nature. Beyond providing her with a framework for understanding her work’s place within the contemporary canon, art school’s most valuable lesson was profoundly personal. Barton discovered what she fundamentally needs for her practice: “A private space, a sense of sanctuary, a space where my body feels very safe. Where I can feel whatever I need to feel, because I have a lot of big emotions that I manage every day.” This revelation about the necessity of emotional and physical sanctuary became, as she puts it, “the biggest takeaway from art school.”

The next turning point arrived when she was hanging drawings for a group show at Sydney’s College of Fine Arts, and the late legendary Sydney art dealer Ray Hughes walked in. Barton’s graphite drawings were emotional self-portraits, some quite graphic. Hughes bought one that night, and from there became her mentor. He understood who she was as an artist, and who she could be if she focused on figurative practice centring on lived experience. She credits his support with “changing everything,” transitioning her from studio practice to professional practice.

At this point in her career, Barton’s art was monochromatic and focused on drawing, but that changed with the birth of her son. “Our first pregnancy was unplanned. I was catapulted into the experience of a pregnant body, which I absolutely loved,” she enthuses. “The birth was long and protracted, but it was the birth I wanted, and that was incredibly meaningful to me. It was a whole different way of being in my body as a woman; it was so abject but so glorious.” Barton can vividly remember seeing her son, Kell, for the first time. “He’s got these amazing green eyes, and I had never felt more—bless my partner, I love him and we’re still together—but I had never felt more dizzyingly in love in my whole life. It’s a love that you don’t have to be afraid of, that’s just so pure, and the reciprocity is so deep, and the alchemy is so deep.” Barton returned quickly to her studio after recovering from the birth and began painting again, using colour for the first time in her professional life. “Look at my paintings now, [they’re like] rainbow kaleidoscopes. Kell was the beginning and the end of the rainbow for me all at once.”

The birth of her son was followed two years later by the arrival of her daughter, Arella. She describes the experience of being a working artist with two young children as “[extraordinarily] challenging, but I was in my vibe.” Seeing her children experience the world fuelled her creativity, and her career soared. “Being a mother has made me a better artist,” she says, “and being an artist has mostly made me a better mother.”

03 Colour bursts from every corner of Barton’s studio. Image: Saskia Wilson. 04 The artist at work; final brushstrokes are added to a new work. Image: Saskia Wilson.

When her son was five and her daughter was three, Barton painted a self-portrait with them, which went on to win the 2008 Archibald Prize. Five years later, she won a second Archibald with her portrait of actor Hugo Weaving. Since then, Barton has solidified her position as one of Australia’s leading contemporary artists. She has held major solo exhibitions, including the highway is a disco at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2017, and participated in international art fairs such as UNTITLED Miami Beach, and Asia Now Paris in 2018. In 2015, Barton expanded her artistic practice into filmmaking with her directorial debut, The Nightingale and the Rose, which garnered multiple awards including the AACTA for Best Animated Short. She continued exploring moving image work with art film Red (2016), featuring Cate Blanchett, and her first feature film, Blaze, in 2022.

Although a spectacular and important piece of cinema, Blaze was an exhausting experience for Barton, its difficult subject matter tearing at old wounds. In February 2022, between finishing filming and the release of Blaze, Barton travelled to the Venice Biennale to visit the exhibition The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani. The show was filled with surrealist art made by women and non-binary artists that Barton admired, but whose work she hadn’t had the luxury to experience in person. It had a profound effect on her. “I feel emotional just going back to this memory,” she tells me. “I was wandering through this show, and I felt the most profound sense of connection—that this is the art canon I belong to. I haven’t felt that in Australia, or at least not in such a holistic, immersive way. It was confronting, in a way, to suddenly feel that I understood what my historical family was. That’s everything to me.”

However, Barton knows she couldn’t produce the work she makes if she were not Australian. “My works, more often than not, have that strong element of Australia which I’m passionate about, and that really defines space in a very particular way,” she says. It isn’t just her art that’s rooted to place, but her sense of sanctuary. “Even in the busiest parts of Australia, here in the eastern suburbs of Sydney, there’s still, for me, a feeling of tranquillity. A distilled quality. Australia just gives me the right energy to anchor my core self.”

“My works, more often than not, have that strong element of Australia which I’m passionate about, and that really defines space in a very particular way.”

hugo, 2013. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Watercolour, gouache and acrylic on canvas, 200x180cm.

Del Kathryn Barton’s the more than human world will be shown at Albertz Benda, New York from 30 October–30 December 2025.

Barton in her studio workspace, where large-scale works demonstrate the powerful visual language that defines her artistic approach. Image: Saskia Wilson.

Catching the current early

Robin Khuda sold AirTrunk just as the AI boom made data centres indispensable. Now the infrastructure titan is applying his exacting standards to Australia’s most coveted coastal addresses—by Carlie Trotter.

Despite evidence to the contrary, Robin Khuda does not possess a crystal ball. The famously smiley 48-year-old entrepreneur who built and sold hyperscale data centre giant AirTrunk for a staggering $24bn last year—Australia’s biggest acquisition of 2024, perfectly timed for the world-upending AI compute boom—prefers to speak of patterns, courage and the discipline of measured risk. Yet his uncanny ability to identify opportunities years ahead of market consensus has made him one of Asia Pacific’s most successful technology infrastructure pioneers.

“I’ve always been curious about what lies just beyond the horizon and drawn to patterns others might overlook,” Khuda says from his North Sydney office, where floor-to-ceiling windows frame the harbour that first captivated him when he arrived from Bangladesh as an 18-year-old with no money and no network. “Being comfortable with uncertainty and having the conviction to follow through when the path isn’t obvious goes a long way.”

In 2015, when data centres were barely a blip on the public consciousness and ‘hyperscale’ meant nothing to investors, Khuda founded AirTrunk with a vision of vast facilities that would power the digital revolution. The following year, the firm secured a $400m contract but lacked the capital to execute it. Rather than walk away, he personally funded the initial operations until Goldman Sachs and TPG Sixth Street Partners came aboard as early backers.

“I learned that taking risks—when done with care and discipline—can really change things,” he reflects. “It’s about choosing the right moment, understanding why it’s important and being ready to keep going after the decision is made.”

With institutional backing secured, AirTrunk expanded methodically across Australia, then

Digital infrastructure pioneer and coastal developer Robin Khuda.

into Malaysia and Japan. By the time he orchestrated its partial sale to a consortium including Blackstone and the Canada Pension Plan last year, the company had multiplied eightfold in value since 2020, operating across five APAC markets with customers including Microsoft, Google and Amazon. Khuda structured the deal to maintain both leadership and a small equity position.

“We built hyperscale data centres before most people were even using the term, which meant a lot of explaining, a lot of patience and occasionally wondering if I’d misread the room entirely,” he recalls. “You need to balance bold vision with operational discipline and surround yourself with people who aren’t just smart but who believe in the long game.”

FROM CLOUD TO COAST

Alongside his continuing role as AirTrunk chief executive, Khuda established Ondas in 2021, dividing his attention between digital infrastructure and residential architecture.

The boutique apartment developer focuses exclusively on waterfront sites—by definition irreplicable— in Australia’s most coveted coastal

locations. It is a strategic move into a market gap he identified during his own drawn-out property search.

“When searching for my own beachfront home, I realised how limited the options were for people seeking something truly special: a residence that is not only beautifully designed and move-in ready, but also responds to the Australian way of life,” he explains. That insight has been sharpened through dialogue with the Kay & Burton team, who understand exactly which waterfront opportunities warrant Ondas’ attention. “We’re seeing a new generation of buyers, from downsizers ready for their next chapter to returning expats who’ve encountered a certain calibre of design abroad, all searching for homes that feel as exceptional as their life experiences.”

The name Ondas (Spanish for waves) captures the next wave of Khuda’s ambitions, this time in bedrooms and balconies rather than servers and silicon. “After years of building infrastructure at hyperscale, I found myself gravitating toward something more tactile: the way architecture, light and landscape can influence how we live and feel,” he

says. “Creating spaces in locations I personally love—like Palm Beach, Mosman and Sorrento—felt less like a pivot and more like a natural evolution.” Each project begins not with architectural plans but with a core question: how will people inhabit these spaces, day after day, season after season? “Australia’s coastline is unlike anywhere else in the world: raw, expansive and alive. As someone who came from overseas, I’m constantly struck by its power to shape not just the landscape but the way we live,” Khuda reflects. “We begin by embracing a sense of openness, seamless connection between interior and exterior, and a respect for the native environment that is more than just aesthetic—it’s experiential.”

STRATEGIC SHORES

The proof of concept came early last year, when Ondas Manly’s penthouse sold for more than $18m. The six-residence building, designed by Rob Mills Architecture, features a geometric facade with soft curves that echo the beach and breakers below. From there, Ondas has expanded north to Palm Beach, where five apartments

The debut Ondas Manly development offers views of one of Sydney’s most iconic beaches.

will rise beside the heritage-listed Barrenjoey House; across to Mosman, where $32m recently secured a site for six storeys of harbour views; and interstate to Melbourne, where 16 St Kilda apartments are already under construction.

Each location has been chosen for its prime waterfront position and potential to showcase what Khuda calls his “zero tolerance for failure” approach, the same standard that ensures AirTrunk data centres operate with military precision. “As with many things in life, who you choose to partner with is so important. Ondas partners with only the best-in-class architects, builders, landscape and interior stylists,” he adds.

The Manly residences demonstrate this rigour with deep overhangs that temper the summer sun, limestone underfoot that blurs the threshold between inside and out, and kitchen benches carved from single marble slabs that promise both beauty and decades of use.

INTUITIVE LUXURY

With three-bed apartments starting from $8.75m, Ondas buyers seek what Khuda calls “that elusive blend of ease, authenticity and subtle delight” that is the hallmark of world-class hospitality. “We take inspiration from the effortless comfort of a favourite retreat,” he explains, “but rather than trying to create a place that feels like a holiday escape, the goal is to foster a home that enriches everyday living, where the sense of renewal and tranquillity is constant.” This ethos manifests in technology that anticipates rather than intrudes: lighting, climate and blinds respond to weather and time of day, wine storage maintains ideal conditions, music follows seamlessly between rooms.

Khuda’s enthusiasm for the process is palpable. “There’s something incredibly fulfilling about crafting spaces that impact lives, spark connection and become part of someone’s everyday story,” he says. He is applying these same principles to

his own Balmoral project, where he and wife Melea are consolidating a double block with the neighbouring property to create their own tri-level residence, testing every Ondas principle firsthand.

EXPANDING HORIZONS

Perhaps Khuda’s most significant construction project is creating pathways for the next generation. Newly named 2025 Sydneysider of the Year, Khuda made headlines in February when the Khuda Family Foundation donated $100m to the University of Sydney, the largest gift in the university’s history and among the most significant in Australian philanthropy.

The gift funds an ambitious 20-year program to equip thousands of girls from Western Sydney with pathways into STEM, spanning high school outreach, academic mentoring and university scholarships. “My vision, shared with the University of Sydney, is that this program that we’ve created will become a game-changing template that others can leverage and scale in the future,” Khuda stated at the announcement. It is characteristic of his approach to look beyond solving immediate problems in favour of systemic, generational change.

ALWAYS BUILDING

Juggling AirTrunk’s continued growth with Ondas’ expansion would overwhelm most, but Khuda seems energised rather than exhausted by the dual demands. “I’m drawn to projects that require patience and precision,” he acknowledges. Though the entrepreneurial drive never fully quiets, he has learned when to step back. These days, rest means family time, ocean walks, genuine quiet—fuel for the work rather than escape from it.

Different as they are, both ventures define how we will inhabit the future. AirTrunk powers our digital existence; Ondas grounds us in physical space. “We’re creating places with lasting quality and character, designed to fit naturally into their surroundings and support the way people actually live,” Khuda says. Then, with the exactitude that has defined his career: “Every element, from the curve of a wall to the framing of a view, is intentional.”

Khuda’s strategy centres on waterfront residences that capture the essence of coastal living.

THE NEW LUXURY CEILING

How $20 million became Australia’s new normal

As next-generation wealth drives multimilliondollar transactions, Australia’s luxury property market is witnessing a transformation in both price and prestige—by Kirsten Craze.

While mainstream metrics might demonstrate steady growth in overall property values, it’s the ultra-luxury price bracket (homes sold for more than $10m) that offers a compelling narrative for Australia’s luxury real estate. Increases in elevated transactions reveal that the high-end market is being redefined.

In Melbourne, more than 10 homes boasting eight-digit price tags hit the market in the first week of August alone, while approximately two dozen sold over that price point in the first half of 2025, according to realestate.com.au listings. For Sydney, 15 homes asking $10m-plus came to market in early August, while more than 100 have sold over that benchmark since January 2025. Anecdotally, luxury real estate agents across the country confirm there are dozens more off-market sales topping $10m, suggesting that the scale of ultra-luxury sales is impossible to accurately tally.

At the extreme end of property prices, new thresholds have been surpassed this year in Sydney and Melbourne. A yet-to-be-built three-storey penthouse in Barangaroo fetched more than $140m, while in Victoria, luxury real estate agency Kay & Burton discreetly negotiated two of the state’s most significant transactions ranging between $50m to $150m. The former $31.6m house price record in Melbourne’s suburb of Brighton was also reset with a recent sale on Moule Avenue which sold for an undisclosed figure.

Mark Browning, head of valuations and property advisory at NAB, says today’s ultra-luxury purchasers are largely entrepreneurs who place features such as privacy, security, and a well-being-focused lifestyle high on their wish lists.

“There has always been a segment of buyers drawn to traditional family estates that have been meticulously renovated with every conceivable modern amenity,” Browning says. “But there’s an equally strong demand for contemporary penthouses, whether it’s a beachfront property on the Gold Coast or a harbour-view residence in Sydney, with integrated luxury amenities. Both styles are commanding premium prices, reflecting how diverse luxury preferences have become.”

While luxury real estate purchasers typically skew towards their 40s and 50s, Browning notes that ABS lending data shows there has been a rise in wealthy younger millennials making their move into the multimillion-dollar market.

Financing figures don’t tell the whole story, with a cohort of top-tier buyers unaffected by interest rate movements or borrowing power.

“At the top, interest rate fluctuations have minimal impact. It probably speaks more to confidence in the wider Australian economy, rather than affordability, given these buyers typically transact in cash,” he explains. “But if lower rates spur the general economy and in turn, share market gains and business viability, that creates a stronger correlation for these buyers than mortgage costs.”

Kay & Burton managing director Ross Savas anticipates the high net worth population may undergo fundamental changes over the coming decade, and with that shift may come an evolution of the top-end property preferences and market dynamics.

“Australia is experiencing a massive intergenerational wealth transfer that represents a once-in-a-generation economic shift with global implications and the momentum is already building,” Savas explains. “Additionally, we’re seeing significant wealth creation from entrepreneurs in technology and digital commerce, a trend that is expected to accelerate in the near future.”

The weakened Australian dollar presents another driver in the luxury property sector. Sitting at or below USD$0.65 for most of the year, the Australian currency presents an enticing value proposition for offshore buyers.

“The lower Australian dollar positions our property market in a favourable light worldwide,” Savas explains. “We’re seeing substantial interest from expats and offshore buyers who are eager to buy here. Both our overseas client database and international business meetings reflect that demand.”

Research shows that on a global stage, Australia’s top 5% of most expensive homes offer impressive “bang for buck.” According to Knight Frank’s The Wealth

Report 2025, US$1m (AUD$1.53m) buys 45sqm of luxury Sydney real estate, while the same amount would secure 87sqm in Melbourne. These metrics represent extraordinary buying power when compared with other cities such as Hong Kong, Singapore, London, New York or Geneva, where US$1m bought less than 40sqm of prime property in 2024.

Jamie Mi, partner and head of international at Kay & Burton, says Melbourne’s luxury property market continues to represent outstanding value for overseas purchasers. “Melbourne remains significantly affordable relative to comparable global cities and emerging luxury markets,” she says. “By October this year, we predict a new wave of curiosity and powerful overseas inquiry, specifically from China, Hong Kong, Singapore, the US and Vietnam.”

“Already, we’re witnessing shorter settlements, even for homes selling for up to $40m, and a resurgence in the all-cash purchaser,” Mi adds. “Should the Australian Government expand immigration pathways, it may create another decade-long wave of demand in the top-end suburbs. Ultimately, we remain competitively priced against other global cities while offering strong long-term growth potential.”

01

02

03

04

04

OF CROWNS, STARS

From Paris to Patiala, tiaras to Tutti Frutti, a landmark new exhibition traces how jewellery house Cartier became a global icon of luxury and innovation— by Praachi Raniwala.

At London’s V&A Museum, a diamond tiara greets visitors with quiet brilliance. The Manchester Tiara, created by Cartier in 1903 for Consuelo, Dowager Duchess of Manchester, stands not just as the opener for this exhibition on the storied Parisian brand—it captures Cartier’s story in miniature.

The tiara’s significance lies as much in its story as in its setting. “It was made in Paris, for an American heiress marrying into English aristocracy,” explains Helen Molesworth, senior curator of jewellery at the V&A and lead curator of the exhibition. It embodies the international reach, cultural cachet and modern vision that turned a modest Parisian workshop into the world’s most influential jeweller.

This global perspective became Cartier’s defining characteristic. The exhibition reveals how the three brothers—Louis, Pierre and Jacques, grandsons of founder Louis-François Cartier—strategically positioned themselves across three continents. “They set themselves up in Paris, London and New York, beginning the globalisation of Cartier,” explains Molesworth.

It was this rare blend of daring design, flawless craftsmanship and border-transcending inspiration that propelled Cartier into one of the world’s most forwardthinking jewellery houses—establishing a blueprint that global luxury brands still follow today.

A RARE GEM

“The three brothers looking to the world around them was the beginning of what we now recognise as the Cartier style and heritage,” says Molesworth. “Jacques travelled through India, the Middle East and Sri Lanka; Pierre explored Russia; Louis found his muse on the streets of Paris.” From Egypt to China and India, no source of inspiration was off limits.

In doing so, Cartier built a vocabulary of design that was light, modern and strikingly ahead of its time while still feeling of-the-moment. The maison’s signature garland style revolutionised 20th-century jewellery, replacing the weighty Victorian aesthetic with an airy play of materials. “Every generation since has tapped into [contemporary trends], but always with a nod to heritage rooted in creativity and craftsmanship,” adds Molesworth.

Over 175 years, this ethos has produced countless icons: the Tank and Crash watches, the exuberant Tutti Frutti necklaces, and legendary pieces for Elizabeth Taylor, Princess Grace of Monaco, and Queen Elizabeth II—whose pink diamond Williamson brooch was famously worn to Prince Charles and Lady Diana’s wedding.

JEWELLER OF KINGS

Founded in Paris in 1847, Cartier’s ties with royalty cemented its reputation as “the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers.” In 1907, Cartier created the trousseau jewels for Princess Marie Bonaparte, Napoleon I’s greatgrandniece, who was marrying into the Danish-Greek royal family. Prior to delivery, the maison displayed the pieces at its Rue de la Paix showroom in Paris— a masterstroke of early luxury marketing.

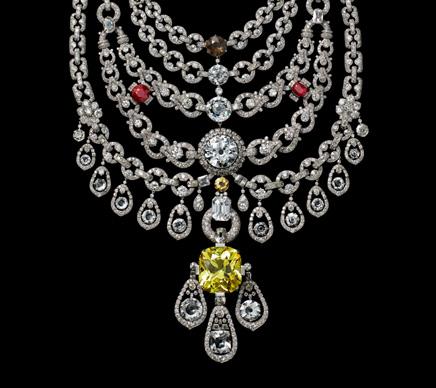

Two decades later, in 1928, came an even more monumental commission—a ceremonial necklace for Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala in India. At 1000 carats and composed of 2930 diamonds, it remains the largest necklace ever created by Cartier.

Grace Kelly’s emerald-cut Cartier engagement ring cemented the maison’s influence in luxury jewellery. Image: The Princess Grace Foundation.

& STONES

“Cartier came up with brilliant ideas in the 20th century that we now call marketing,” says Molesworth. “But it only worked because the jewels themselves were extraordinary. You cannot sustain 150-plus years of success without being rooted in quality.”

THE FAMILY LEGACY

“The unshakeable bond of the three brothers was the magic ingredient,” says Francesca Cartier Brickell, great-granddaughter of Tutti Frutti mastermind Jacques, and author of acclaimed 2019 book The Cartiers. This human dimension, she explains, was “the essential element my grandfather [Jean-Jacques] felt was absent from publications about the firm and its creations.”

Francesca’s research revealed the extraordinary depth of the brothers’ relationship. Initially, she questioned whether the family stories might be romanticised. “My grandfather had told me how his father and two uncles would do anything for each other, so much so it annoyed their wives,” she recalls. “But I always wondered if this was an exaggerated family legend passed down with rose-tinted spectacles.”

Then she discovered proof in decades of correspondence. Pierre wrote to Jacques during WWI: “You know from experience that my two brothers mean everything to me. It’s together that we dreamed of the greatness of our house; it’s together that we developed it and spread its fame to the four corners of the globe.” As Francesca puts it: “This wasn’t a fairy tale—it was documented reality.”

For Francesca, this family spirit lives on at the exhibition. The Cartier London Stag brooch—never before displayed publicly—particularly resonates. “It was the piece my grandfather Jean-Jacques was most proud of,” she explains. The brooch, created as a wedding anniversary gift for her grandmother’s sister, embodies the family’s “commitment to ‘never copy, only create,’ their belief in taking time to do something properly, and that magical collaborative spirit between designer and craftsman.”

The exhibition reminds us that jewellery is never mere ornamentation, notes Molesworth. “When you look at Cartier, you see how the world has changed, how it has responded to jewellery, and how one of the greatest maisons of all time helped shape the story of the 20th century.”

Ultimately, Cartier’s genius lay in both design and marketing strategy. Through limited production and placing pieces on celebrated women, every move created desirability that fed the brand’s global mythology—turning objects into symbols of power.

01 Manchester Tiara, Harnichard for Cartier Paris, 1903. Commission for Consuelo, Dowager Duchess of Manchester. Diamonds, gold and silver; the C-scroll at each end set with glass paste.

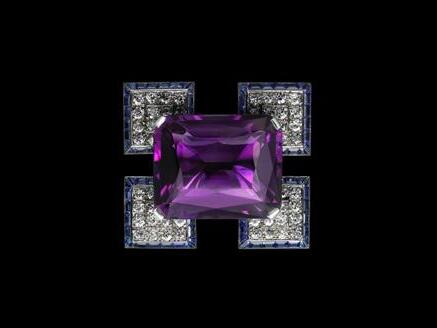

02 Brooch, Cartier London, 1933. Amethyst, sapphires, diamonds and platinum. Image: Vincent Wulveryck, Collection Cartier.

03 Patiala Necklace, Cartier Paris, special order, 1928 (restored 1999–2002). Commissioned by Bhupinder Singh, Maharajah of Patiala. Diamonds, yellow and white zirconia, topaz, synthetic rubies, smoky quartz, citrine set in platinum. Image: Vincent Wulveryck, Collection Cartier.

Cartier is showing at the V&A South Kensington (London) until 16 November 2025. vam.ac.uk

With countless ventures under his belt, Australian businessman Nick Bell has made momentum his trademark. His latest obsession applies the same systematic approach to the ultimate challenge: redefining what it means to age—by Adam Turner.

The eternal entrepreneur

Running his first side hustle from a high school locker in the 1990s, enterprising farm boy turned rich-lister Nick Bell set off early on the road to success. Growing up on a sheep and cattle farm in Mount Macedon, northwest of Melbourne, Bell dreamed of the big city lights. Determined to make it a reality, the ambitious teenager set his sights on moving to London and went to work raising the cash for a plane ticket.

“I was always hustling to make money,” Bell says of his school years. “That [attitude] comes from my father. He had a couple of businesses, they weren’t all that successful, but he always had the itch for it and I thought that was amazing. When I was young, I thought being an entrepreneur was like being a movie star, offering the freedom to march to the beat of your own drum, and I wanted that life, even though I wasn’t sure if it was attainable.”

Determined to make the dream a reality, Bell wasn’t content to wait. Setting up shop in his locker at recess, he started leasing out sports equipment, computer games and videos to fellow students. He even sold his school lunches to raise cash, going hungry in his first taste of hustle culture which prioritises work and ambition over all else.

Thanks to his extraordinary drive, Bell finished high school with enough funds to get him to London, where he worked in bars before returning to Melbourne to study marketing. His academic career lasted six weeks before he returned to hospitality work. With his sights set on bigger things, Bell bluffed his way into a data entry job by claiming he could touch type, then moved to sales where he quickly climbed the ranks.

By age 24, Bell says he was tired of climbing the corporate ladder to make others rich. Determined to put his sales skills to work for himself, he founded his own skincare business focused on a tablet-based acne treatment. In a harsh reality check, after three years of hard work, the reality was sobering: he was still earning a mere $75 a week from the business.

While the fledgling skincare business didn’t completely fail, it never took off, hampered in part by supply chain issues and an inability to scale. The setback offered Bell valuable lessons about resilience and execution—but perhaps more importantly, it crystallised his understanding of what drives him.