Introduction to Natural Dyes

Compared to synthetic dyes, which often follow one correct method, natural dyeing is more like cooking. There are as many ways to extract colour from plants as there are cooks. Each plant has different properties that affect how it’s used. Just as you wouldn’t cook spaghetti the same way as paneer, every plant needs a different approach, and each dyer has their own techniques. That said, the process below has been simplified to work with most plants. For more detailed methods, see the books listed in the resources section.

There are 3 broad categories of dyes:

1. Substantive dyes (which need no mordant and include tannin rich plants such as oak galls and staghorn sumac).

2. V at dyes (such as indigo which require processes not covered here)

3. Adjective dyes . Adjective dyes are the most common and require a metallic compound such as iron or alum to bond with the fibre effectively.

Generally speaking natural dyes only dye natural materials including animal fibres: silk, alpaca and wool, or plant fibres: cotton, linen, hemp, rayon, viscose and ramie. The methods and mordants used in this handbook can be used to dye any animal fibre . For instructions on dyeing plant fibres see one of the books in the resources section.

What is a Mordant?

A mordant is a substance that has an attraction to both the dye and the fibre and so makes many dyeing processes possible. The word mordant comes from the French, mordre , to bite. One of the most common mordants is alum which is a form of aluminium.

Other metallic mordants included copper and iron. Many tannin-rich parts of plants are used as mordants. This includes tree barks and the galls of oak trees. Rhubarb

leaves contain the chemical oxalic acid and work well as a mordant. Note that if you use the liquid from rhubarb leaves as a mordant it will give your fabric a yellow tint and also take precautions as it is mildly poisonous.

Mordants can be added at different points during dyeing. The process described below uses a pre-mordanting method where the fibre is infused with mordant before dyeing. For other options see the resources section.

Process

1. To prepare the fibre for dyeing, first wash well. Then to pre-mordant, first weigh the dry fabric and calculate 5% of this weight. Weigh this amount of alum and dissolve in warm water in a large dye pot. Add plenty of water (enough to allow the fibre to move easily) and add fibre. Heat to just below simmering for 1 hour, stirring frequently. You can also line dry the fibre and store for later dyeing.

2. Pick local dye plants or kitchen scraps. (suggestions on page 2) Onion skins are a strong and ancient dye and work reliably in workshops. Many of the plants listed can be found in abundance along canals and wild spaces in London. Any foraging needs to be done responsibly by choosing only fallen branches or foliage or other plants that are very abundant or invasive. Rare plants like lichens should never be picked.

How much to collect? A general rule is to collect the same weight of plant matter as the dry weight of your fabric. This also means that if you use lightweight fabric like silk, less dye plants will be needed.

3. Wash and chop the plants. This helps release the dye more quickly. Barks and roots may need to be soaked overnight or longer.

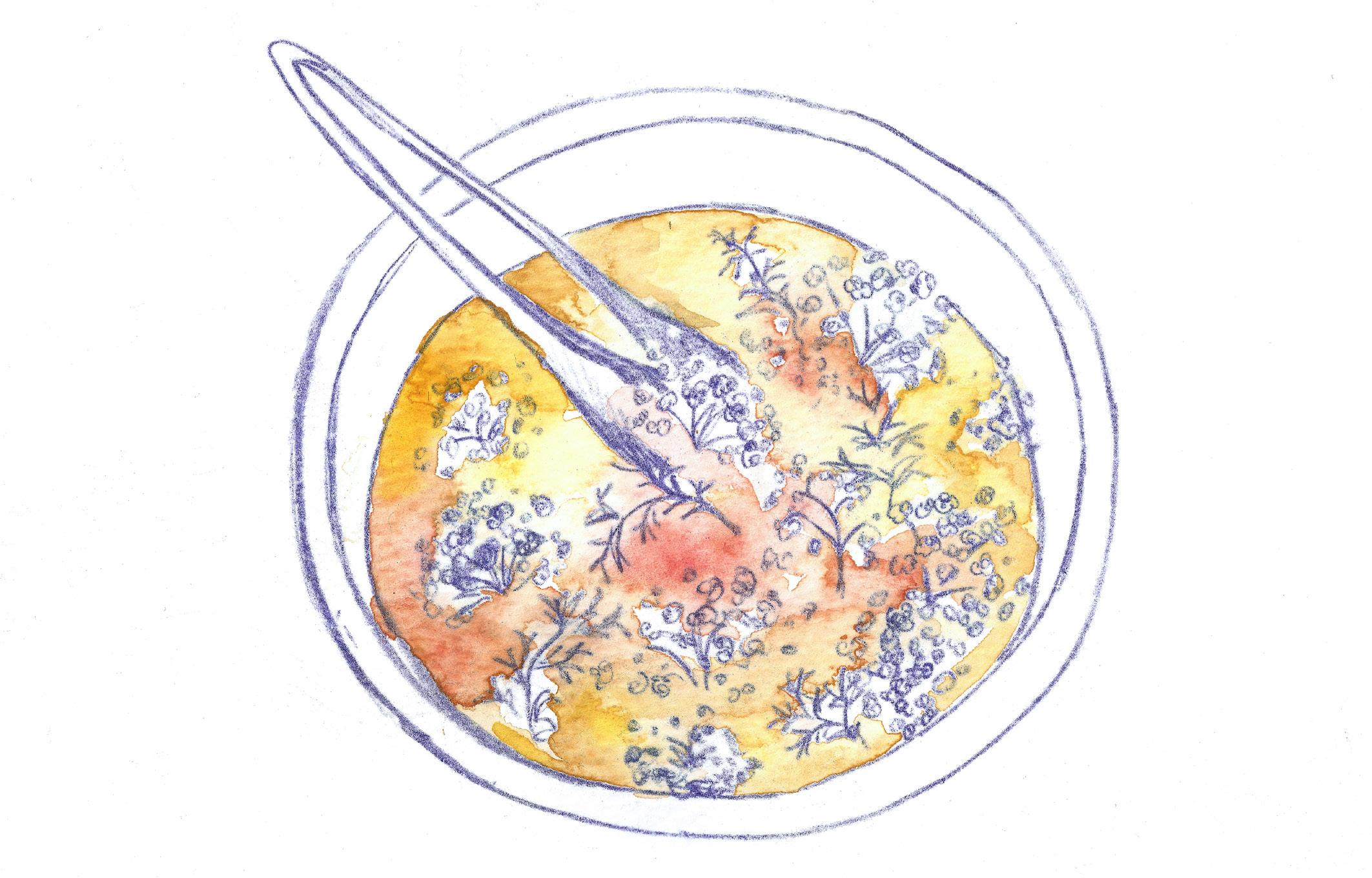

4. Heat the plants in water to simmer leaves, roots and bark. Use a minimum amount of heat for delicate parts like flowers. Watch the colour of the water. Most plants will release the majority of their colour within 40 minutes.

Carefully sieve the plant matter out and keep the liquid (allow to cool if pouring cannot be done safely hot).

5. Immerse mordanted fibre in the dye liquid (add more liquid if needed for easy movement). Heat the dye bath and stir fibre regularly. The longer you keep the fibre in the dye bath, the deeper the colour will be.

6. When finished, remove the fibre and rinse with mild soap and hang to dry.

7. The discarded plant matter can be composted and the alum water poured down the drain or on alum loving plants such as rhodedendron.

List of Supplies

Dye plant material

Mordant appropriate to dye and fibre

Dye pots and lids

Stove or kettle

Fabric (natural fibres)

Tongs

Sieve

Scissors

Washing line and clothes pegs

Weighing scales

Washing soda & vinnegar change the pH.

Shibori materials to create patterns

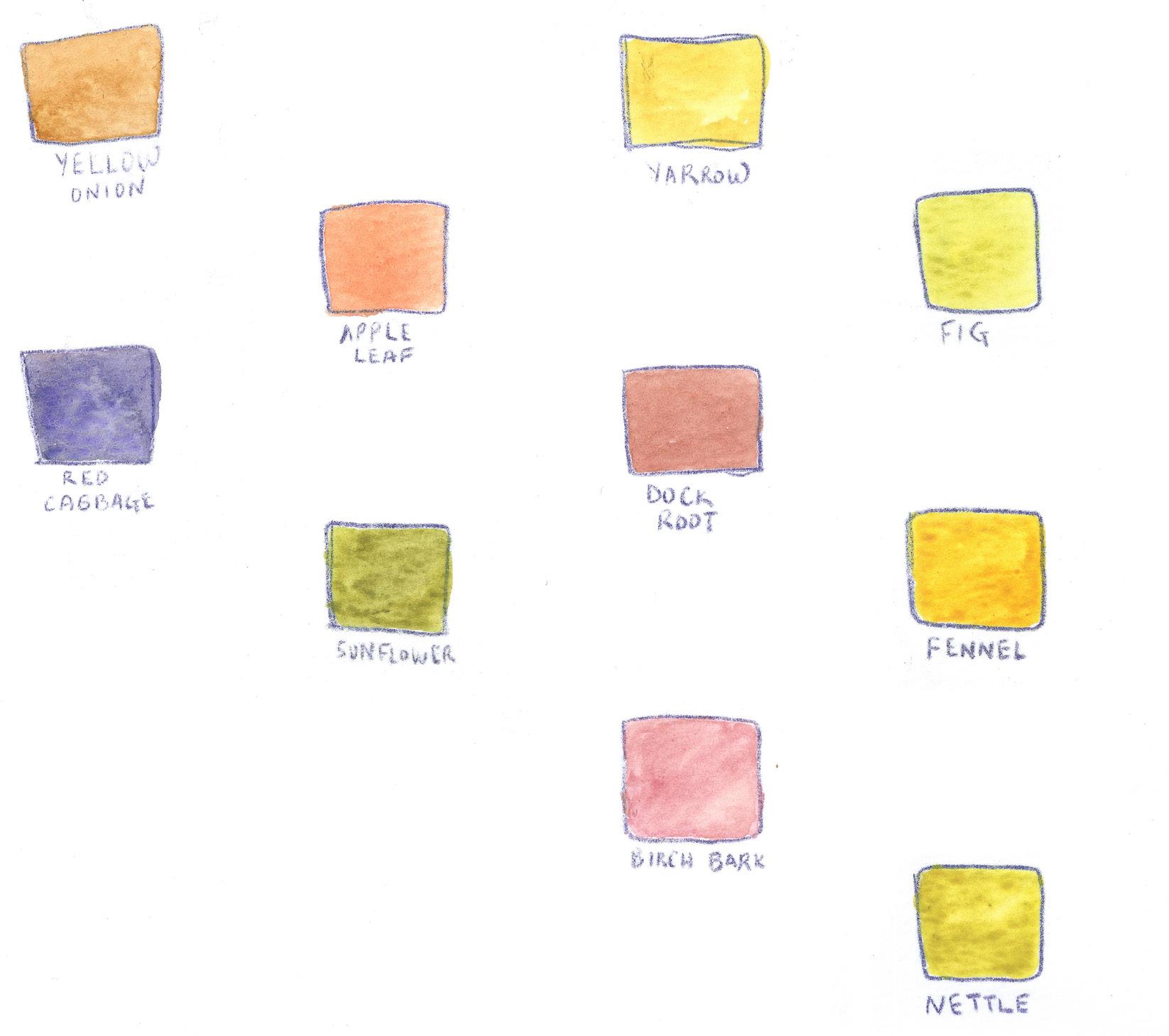

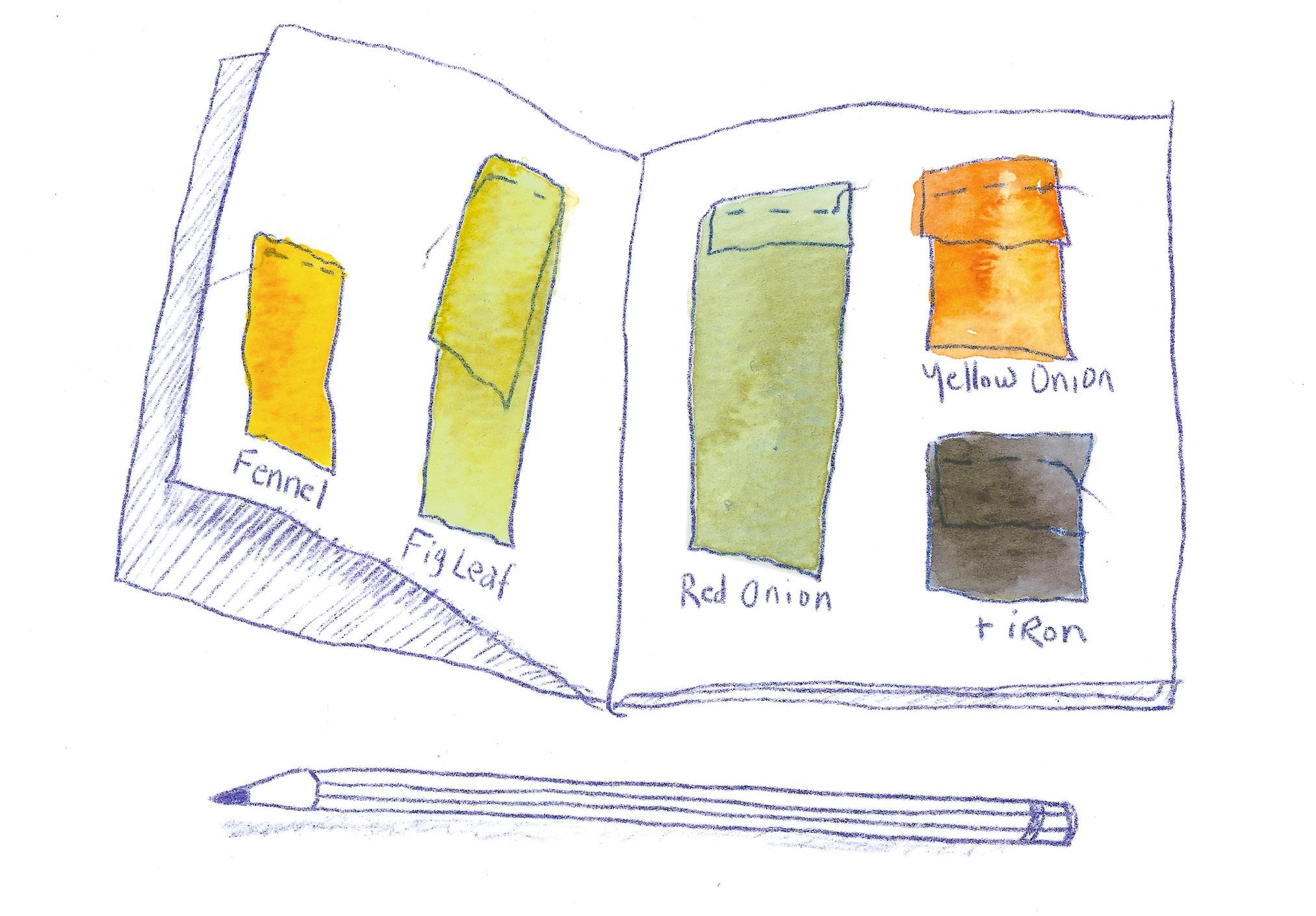

Swatch book to record different dyes

Notebooks and pencils to make note of dye plants used, weights and heating times.

In the Classroom

Natural dyeing is useful for students from all fashion disciplines as it raises many questions relating to the source of our materials and colour.

Dyeing can be done in a classroom without a stove by making concentrated dye baths in advance and topping up with water boiled by kettle just before use. The warmth is a catalist and speeds up the dyeing process. Fibre can also be left in the dye bath overnight for deep colour but dyeing may not be as even.

Small electic hobs can be used but it is better to do the initial heating of plants on a strong heat source as large pots of water can take a surpising amount of time to heat.

If a day or whole afternoon class is possible the students can take part in the whole dyeing process including the chopping of dye plants and pre-mordanting of the fibre.

Silk habotai is a good fabric for workshops as it take the colour very quickly and brightly.

Questions to consider and discuss in class

Q. In your fashion work, how do you go about choosing colour?

Answers to Basic Questions

1. What is a Dye?

A dye is a colored substance that has an ability stick to a substrate such as fabric.Most dyes require a mordant to improve the fastness of the dye on the fiber.

2. What is a natural dye?

Q. Where do dyes come from and what are them made of?

The majority of natural dyes are from plant sources – roots, berries, bark,

leaves, and wood, fungi, and lichens but also metallic substances such as iron, chrome and copper.

Humans have been using natural dyes for thousands of years. In fact any textiles made before 1856 will have been coloured with natural dyes.

3. What is a synthetic dye?

The term synthetic dye usually refers to dyes made in the lab from petroleum.

History

Before the invention of synthetic dyes, brilliantly dyed fabrics were made around the world in every shade of the rainbow using plants, minerals and some animal or insect products. Many of these were readily available and locally produced but the most costly and sought after colours were often only available from rare, far away or very labour intensive dyes.

One such example is the famed purple cloth worn by Roman emperors and Medieval royalty. This colour was made from sea snails or insects local to present day Lebanon and called Tyrian purple and crimson kermes.

Plant-based dyes such as woad, indigo, saffron, and madder as well as the insectbased cochineal were raised commercially and were important trade goods in the economies of Asia and Europe for many centuries. The origin of these dyes were kept as valuable trade secrets and in some cases the process used are still unknown today.

In the 1850s William Henry Perkins made the first sythetic dye accidentally in his East London lab. He was actually trying to make quinine (used for the treatment of malaria) from coal tar but instead created the first aniline dye, a purple which he called mauve.

Perkins’ invention spread rapidly, with several more colours created in the following years.

These new dyes could be made far more quickly and cheaply than many of the natural dyes and offered a standardised process that fit the industrial age.

Today ntural dyes are used very rarely on a commercial scale. However as interest in petroleum alternatives and locally sourced materials grows, so has the number of designers looking to use natural dyes again.

Qualities

You might find that natural dyes give a more complex colour than synthetic dyes. The down side of this is that it can be more difficult to get very even colours using natural dyes. But they are particularly adept if you are looking for subtle shimmering colour combinations or ombre effects.

Myth 1:

Natural dyes produce only drab colours.

If you’ve ever been to a museum such as the V & A in London, all of the textiles from before 1856 will have been naturally dyed, which gives an idea of the full range of colours possible. Natural dyes can be used to create every colour, it might just take a bit of research to find out the best plant.

Myth 2:

Natural dyes fade in the wash or sunlight.

Actually many naturally dyed textiles are more resistant to fading than conventionally-dyed garments. Each natural dye has different properties and some do fade faster than others. See the resources section for more information.

Myth 3:

Natural dyes are always safe and ‘nontoxic’.

Just because natural dyes only use nonpetroleum based chemicals does not mean they are without question non-toxic and safe. Especially in previous centuries many heavy metals such as chrome and copper were used. Also Medieval dyers made much use of stale urine and modern indigo dyers often use the highly caustic chemical, lye. For these reasons before the advent of sythetic dyes, dyeing districts were often far removed from town centres due to the smell and pollution they generated.

However, with modern methods, natural dyes offer the possibility for completely non-toxic colour -even edible dyes in some cases!

Health and Safety

Use different utensils and pots for cooking and dyeing! Even if you’re not using a mordant, a surprising amount of locally grown plants contain harmful chemicals.

If you’re using alum, it is technically a skin sensetiser. When sold in crystal form a mask is not necessary but wear gloves or use tongs to protect skin.

Using only 5% of the fabric weight of alum will keep from too much powder being present in the dry fabric before it is washed out.

Tongs and appropriate protective equipment for working with hot liquids and hot surfaces are essential.

List of Plant Dye Resources

Compiled in November 2014

Suppliers

Fibrecrafts at George Weil: supplier of mordants and natural dyes (UK) http://www.georgeweil.com/Fibrecrafts.aspx/

Woad Inc. (based outside Norwich, UK): Grower and supplier of Woad. The Woad Centre also runs demonstrations and events. http://www.thewoadcentre.co.uk/

Earthues (Seattle, USA) supplier of natural dyes for craft and industry www.earthues.com/

Books

Wild Color: The Complete Guide to Making and Using Natural Dyes by Jenny Dean and Karen Diadick Casselman

Guide des Teintures Naturelles by Marie Marquet

The Handbook of Natural Plant Dyes by Sasha Duerr

Eco Colour: Environmentally Sustainable Dyes by India Flint

A Dyer’s Garden: From plant to Pot. Growing Dyes for Natural Fibers

Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science by Dominique Cardon

Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans by Jenny Balfour-Paul

Fashion and Sustainability: Design for Change by Kate Fletcher and Lynda Grose

Gardens featuring natural dyes in the UK

Museum of the Home, East London

https://museumofthehome.org.uk/

Vauxhall City Farm, SW London

http://www.dyework.co.uk/index.shtml/

Horniman Museum and Gardens, SE London

http://www.horniman.ac.uk/

Chelsea Physic Garden, West London http://chelseaphysicgarden.co.uk/

Oxford Botanic Garden, Oxford, UK http://www.botanic-garden.ox.ac.uk/

Websites and Organisations

CRIT Horticole, Rochefort, France

Supports the development of businesses and facilitate innovation in Europe in four areas, one of which is the use of plant dyes. http://www.critt-horticole.com/

The Centre for Sustainable Fashion, UAL Keep in touch via the blog and social media to find out about upcoming opportunities. http://www.sustainable-fashion.com/

Fibershed: a non-profit organization providing experiential education to build and sustain a thriving bioregional textile culture in California.

http://www.fibershed.com/

Slow Lab: a collective of Slow experiments for art and life.

http://www.slowlab.net/

Plants for a Future: excellent database for finding and identifying useful plants. www.pfaf.org/