Banquet

ARTISTS

Marissa Lindquist

Michael Chapman

Timothy Burke

Derren Lowe

Robyn Schmidt

Imogen Sage

Ayesha Tansey

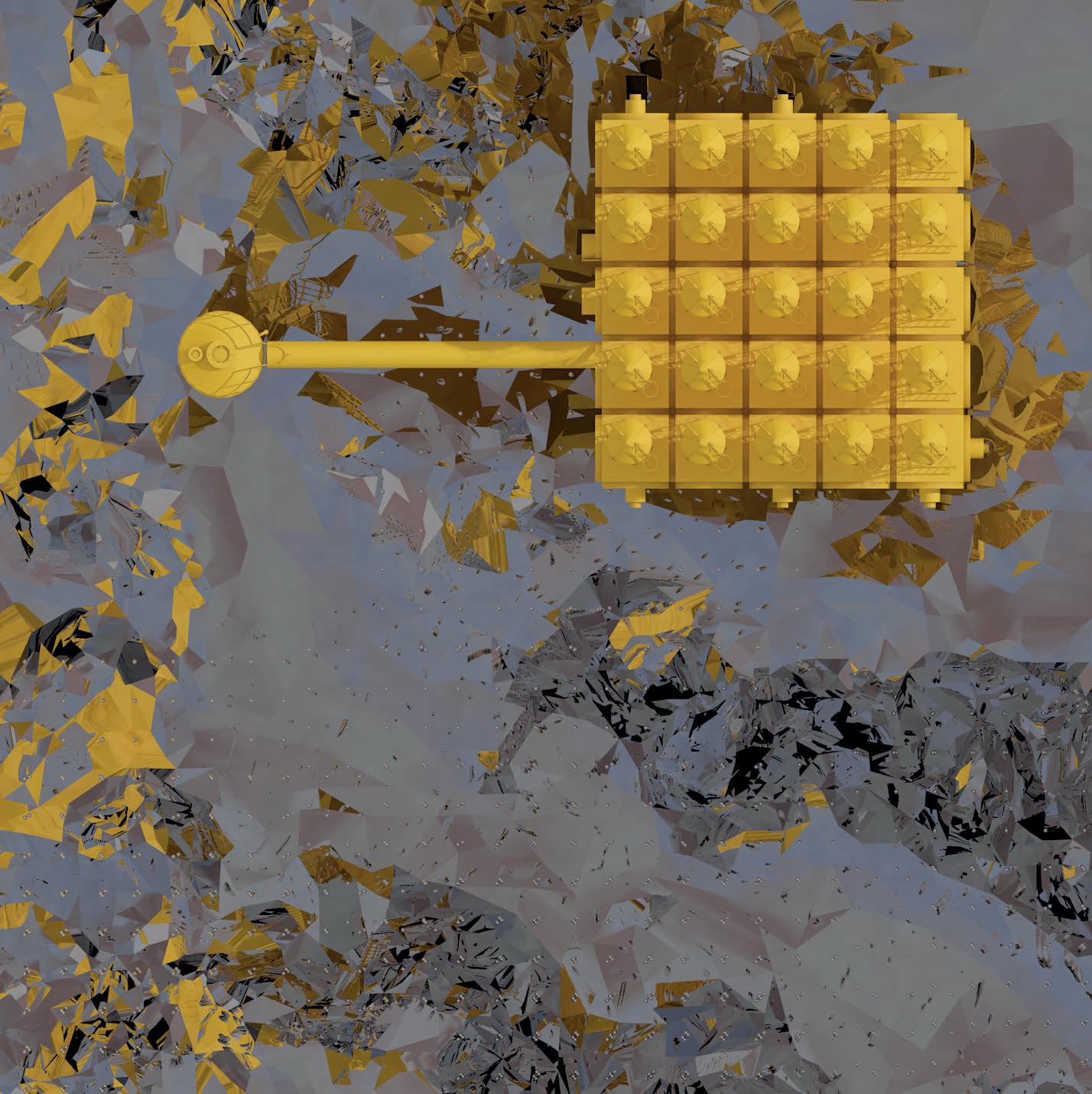

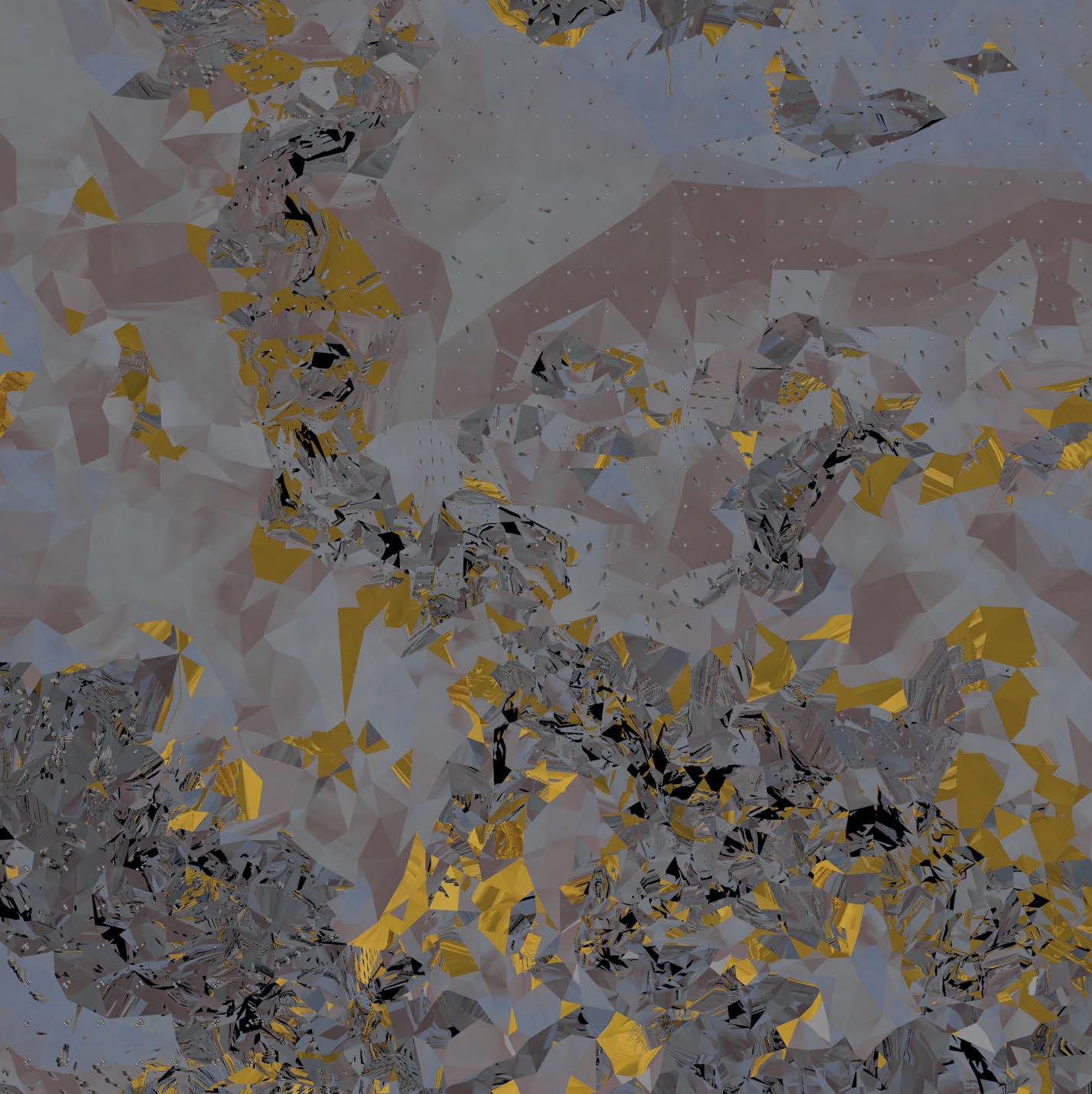

Food has become an integral part of the contemporary culture. At the height of the global pandemic, the absence of public and private dining experiences had a profound impact on personal and interpersonal wellbeing. The exhibition sets out to interrogate the processes and rituals of food, the human condition and architectural production. The exhibition explores the relationship between space and the experience of consumption tied to literary and filmic narratives, through a transhistorical degustation of interactive food machines.

Banquet reimagines the Tin Sheds Gallery, conceptualised as an interactive banquet hall, referencing Nero Germanicus’ Golden Banquet Room – an experiential space for the production and consumption of food and bodily delights. Seven handcrafted analogue machines installed as stations throughout the space, respond to the various courses of a degustation, constructed through architectural means. The stations act as working machines engaging different materials, processes, and scales creating a direct relationship between the viewer, the machine and gastronomic themes. Critical to Banquet’s mise-en-scene is performative pieces reflecting the physical relationship between the gustatory experience, the human condition and dramaturgical movement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands on which this exhibition is being held, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, and we pay our respect to the knowledge embedded forever within the Aboriginal Custodianship of Country. Much of the work for this exhibition was produced on lands of the Worrimi, Awabakal, Gumbaynggirr, Turrbal and Yugara people and we also acknowledge the traditional owners of these lands.

We would like to genuinely thank the enormous number of people that have made this exhibition possible. Tin Sheds Gallery and the University of Sydney have been invaluable and supportive collaborators and Kate Goodwin and Iakovos Amperidis have provided exceptional support, guidance and inspiration throughout. Peter Fisher has been an incredible part of this work, working tirelessly on the production of the catalogue and providing exceptional support and guidance throughout.

We are also grateful to the workshop staff at Queensland University of Technology and University of Newcastle. We were lucky to receive Summer Vacation scholarships through University of Newcastle to support this project. We would like to thank Jackson Voorby and Lexi-Le Owen for the amazing support in the lead-up to the exhibition. Jackson’s drawings are featured throughout the catalogue, and he has been an inspiring and hardworking collaborator on the show. Equally, Lexi’s patience and graphic skills have been invaluable in the layout of the catalogue and preparation of exhibition material. In addition, Sarah Jozefiak was an inspiration and important collaborator.

We would also like to thank James Dwyer, Aaron Crowe, Na Li, Guiherme Nettoalvesdosreis, Tom Dufficy, Simon Hewitt and Paul Ridings for their time and commitment to the project. Ceren Sinanoglou provided guidance and insight and was an early collaborator in the project. We are grateful to Richard Tipping, for making his WordXimage gallery available to use for a preliminary exploration of the projects.

EXHIBITORS

Marissa Lindquist

Marissa is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at the Queensland University of Technology, and Fellow of Australian Institute of Architects. She holds a PhD (UoN) in neuro-imaging and spatial experience and her teaching practice dwells on the margins of interiority, perception and material making.

Michael Chapman

Michael is Professor at the University of Newcastle. His research and creative practice explore architectural drawing, crossovers between art and architecture, Marxism and industrialisation.

COLLABORATORS

Exhibition

Timothy Burke

Timothy is a Lecturer of Architecture in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at the University of Newcastle. In 2019 he was awarded a PhD in Architecture through creative practice research which examined the relationship between machines, drawing and architecture. His current research and teaching are concerned with ways of reimagining postindustrial sites.

Derren Lowe

Derren is a Lecturer of Architecture in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at the University of Newcastle and practising architect. His current research and teaching are focused on memory and narrative explored through drawing and its manifestation in material tectonics.

Robyn Schmidt

Robyn is a graduate of the Design School at Queensland University of Technology. She is currently involved in teaching interior architecture and design psychology and sociology. Her interests include how design can benefit society with particular attention to slow design and the handmade.

Performance

Imogen Sage

Imogen is an actor and maker who trained at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in London. She works in the fields of theatre, film, audio production, and experimental performance. Her current interests include story, female relationships, and the rise of desire.

Ayesha Tansey

Ayesha Tansey trained at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in London and at École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris. She has worked as an actor and a devisor and creator in over 25 productions across Europe and Australia, in both English and French.

Publication

Peter Fisher

Peter is an editor, researcher and curator within architecture, design and photography, producing monographs for Australian and international practices. He teaches both at the University of Sydney and the University of Newcastle and is currently completing a PhD in Architecture examining the role of architectural representation within the photograph and the postcard image.

Assistants

Jackson Voorby, Lexi-Le Owen, James Dwyer, Aaron Crowe, Na Li, Guiherme Nettoalvesdosreis, Simon Hewitt, Paul Ridings.

CONTENTS

Foreword: The Food of Love | Neil Spiller

Exhibition Rituals | Kate Goodwin

Introduction | Michael Chapman and Marissa Lindquist

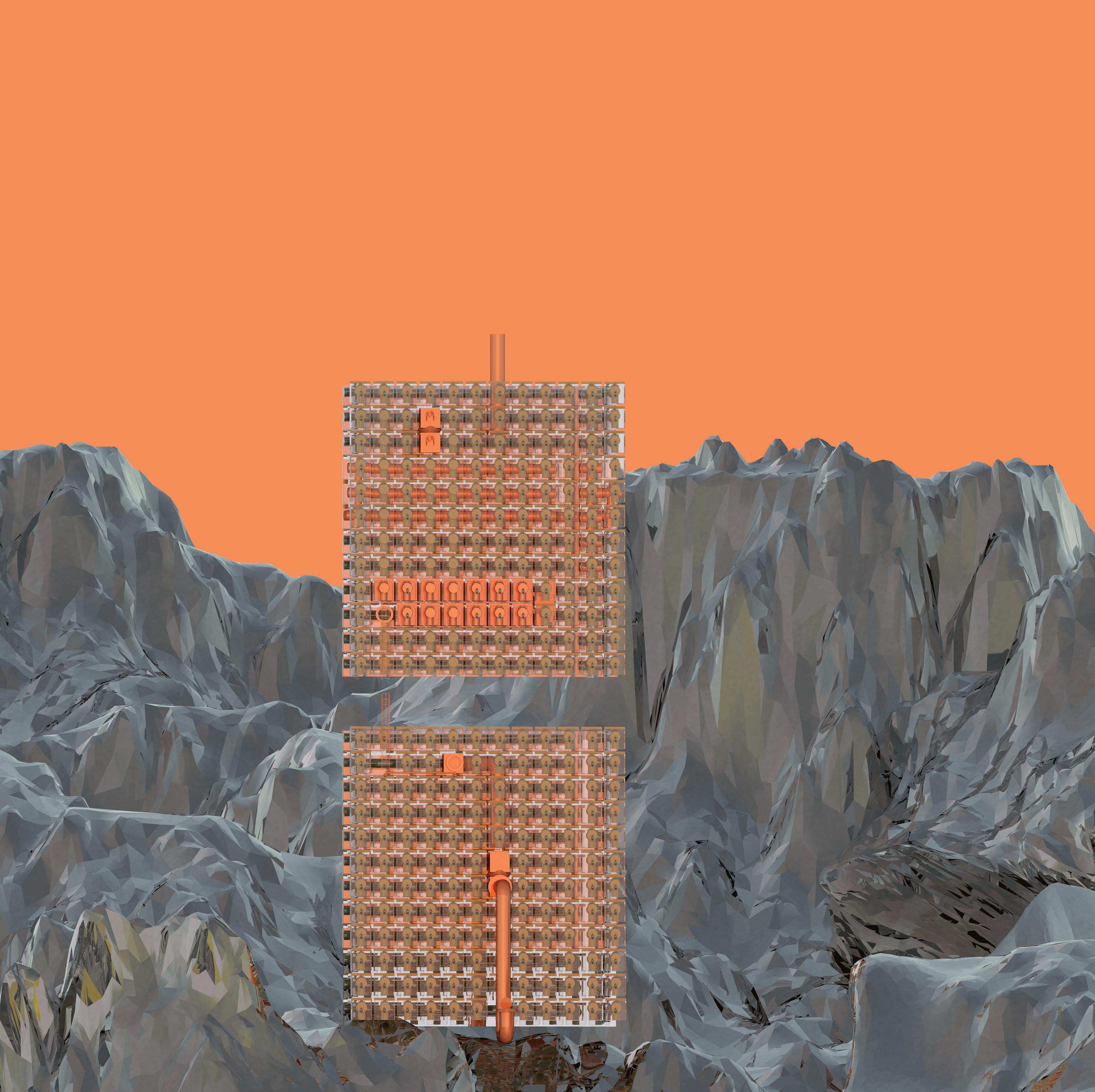

Banquet Hall | Bacchanalia

I Hors d’ouevre | Petite

II Soupe | Rondel

III Entree | Ho Wah

IV Main | Aporcalypse

V Aperitif | Sleeper

VI Café | Godard is Dead

VII Dessert | He is Free

VIII Performance | The Last Octopus Tentacle

IV Leftovers

“A

revolutionary career does not lead to banquets and honorary titles, interesting research, and professorial wages. It leads to misery, disgrace, ingratitude, prison, and a voyage into the unknown.”

—Mark Horkheimer

Image courtesy of Neil Spiller.

“In a circular arcing movement, from street to shop interior, passing through a shop window pane showing reflections but not smashing the glass, fluttering through the host of hanging garments. In association with manikins, boxes of coloured gloves and elaborate hats, Oskar Kokoschka enters an exclusive, expensive, fashionable clothes shop in Vienna. The door bell tinkles.”

Peter Greenaway opening scene directions of The OK Doll. Dis Voir, Paris, 2014.

The Food of Love: Filmic Machinic Desires

Neil Spiller

When asked to write a short introduction to this catalogue and, vicariously the exhibition that accompanies it, concerning the intersection of food, machines and film, I started to muse on one of my favourite true stories. It is a story of hungry desire, of human hubris and psychotic delusion based in Vienna at the end of the First World War. It is also a story that inspired the great film director, Peter Greenaway to write a film script (for a yet unrealised film project) based on its surreal basic premise. It concerns the artist Oskar Kokoschka who had a violent carnal love affair with composer Gustav Mahler’s widow Alma. When the liaison ended, she aborted his child. Kokoschka had a dressmaker make a life-sized doll of her with the facsimile anatomy for love making of various types. He lived, loved and abused the doll for a number of years, hosted parties, drank a lot, took her to the opera until he eventually tired of her, drenched the doll in wine, cut off her head and hurled her from an upstairs window into the street.

Whilst the doll is not a straightforward metallic machine, in the old-fashioned sense, it is a machine, a machine of desires, nonetheless. This fruity and alcohol infused tale, and let’s face it fruit has often been served as an analogy for matters sexual, makes my thoughts spiral off into other surrealist realms. The work of Hans Bellmer, who knew of Kokoschka’s doll, Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass with its coffee grinder, Tanguy’s fruiting bodies and Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures, as examples. So, this exhibition will further expand the lexicons, languages, semiotics and the symbiosis between the culinary, mechanical and projected whether celluloid or digital. I look forward to seeing the fruits all the labour and tasting its intellectual and creative delights.

Professor Neil Spiller is an architect and Editor of Architectural Design Magazine.

Exhibition Rituals

Kate Goodwin

You might ask, why exhibit architecture when it surrounds us everyday? My response would be that exhibitions are a space, one-removed from the real world, in which to test ideas with an attentive and physically present audience. With the capacity to employ spatial and performative practices, an exhibition becomes a particularly compelling and widely accessible medium to disseminate ideas. Not all ideas however make good exhibitions – many suit a book, a conference or a film much better. But in the case of Banquet, the ideas necessitate an exhibition. Banquet explores architecture and the human condition through machines that ritualise food production and consumption. These are concepts and objects to experience and to feel—to understand architecturally, sensually and physically—to participate in and to perform.

World Fairs, where nations displayed their industrial might, became cultural phenomena in the nineteenth century and demonstrated the impact of exhibiting. The ‘Great Exhibition’ of 1851, attracting 6 million visitors to Hyde Park London, brought together 14,000 manufacturers, designers and artists from across the globe to display their work in a revolutionary glass structure the ‘Crystal Palace’, designed by Joseph Paxton. Set with dramatic, seductive staging within the 39-metre-high space and running its 564-meter-length, industrial machines and commodity goods were aestheticised and turned into objects of desire. As well as changing societal attitudes to the Industrial Revolution, it was to have a lasting impact on art and design education and tourism, not to mention the spectacle.

In contrast to a book, exhibitions on any subject, convey concepts in part through physical experience. Relevant objects, images and sounds are placed in a spatial relationship with one another, creating a choreography of encounter for an audience.

While each piece will have its own integrity, when placed as part of an exhibition context they can acquire a new or added meaning. These underlying narratives and ideas are made present and palpable through staging and the creation of atmospheres, appealing to the emotions as much as the intellect.

Exhibitions are invariably social experiences, as recognised early in their history. The Royal Academy’s annual exhibition, established in 1769 marked the launch of the ‘summer season’ where the well healed English socialite went to be seen as much to see art. The presence of the visitor is part of their allure. A performance occurs as visitors move through a space, either directed or drawn to works and interacting with other people. When crowded, careful navigation takes place between visitors, with an unspoken set of rules that dictate whose turn it is to view the works and read labels. Discussion can be sparked between friends or strangers, or quiet and reflection can settle over a crowd. The mood and energy shifts in time and space.

Architecture too invites us into an act of performance. Overlooking a concourse in a busy station, is like watching a dance as bodies negotiate their way around one another, generating a gentle pulsating rhythm. The space becomes alive and purposeful, making the performance of daily rituals legible. When designing the new restaurant buried in the basement of Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram building, New-York based architects, come artists Diller, Scofidio + Renfro underlined one of the essences of eating out – the desire to be seen. The ritual of making an entrance is exaggerated as screens hanging above the bar continually update with blurred images of every patron who passes through the revolving doors. Likewise, the entrance to the restaurant is theatrical, with an elongated glass staircase that assures patrons descend slowly into the heart of the space, as though on a catwalk, turning dining into a social spectacle. The same is done with the preparation of food.

Recent trends for open kitchens in restaurants places cooking on display – the chefs and their accoutrement are performers in the dining experience.

The exhibition Banquet operates performatively on three registers. The machines placed at ‘stations’ in the gallery, have been crafted to perform an architecture of food production. One makes a continuous stream of Hors d’oeuvres on a conveyor belt alongside a moving architectural frieze. Another dispenses treats, while another registers the passing of time in coffee production, with granules slipping through an hourglass allowing the residue to leave marks on paper. The hum of analogue machines in operation creates a background soundtrack for the exhibition.

The stations are set as if a theatre in the round, and the presence of audience members completes the exhibition – they are not just witness to what is on show, but participants in and components of the exhibition itself. An audience member is drawn into observe an experiential phenomenon, and themselves completes the scene for an audience member on the other side. At times confronting, the experience invites us to consider how we are entrapped by luxury and opulence.

This narrative is also enacted through a live performance on the opening night, taking attendees on a physical, sensual and emotional journey of indulgent, hedonistic consumption. Two performers, an eater and server, initiate a banquet devouring course by course in which the audience is invited to partake. They celebrate the pleasure of eating, only there is no food – is it reality or fantasy? As the creators Imogen Sage and Ayesha Tansey express, “All is an act. All is for the viewer. And the audience is in on the conceit – there’s something perversely satiating about watching another eat, even if it’s make-believe”. As the imaginary feast unfolds, each course becomes more absurd, from octopus tentacles cooked in saffron butter to

luxury Belgian chocolate, in the anticipation each might be the last. “What happens if the eater stops playing the game?” the dramaturges ask, “if they stop complying with the rules, and go off script, when emptiness becomes too much to bear”. Only time will tell how the audience might react as the performance spirals out of control. As the performance is live-streamed the exhibition is transported into another, virtual realm – broadcast and captured on film.

Banquet has its foundations in scenes from films and literature that co-opt the preparation of food and its collective consumption for socio-political narratives and dramatic purposes. These scenes became critical and creative provocations for the creators, Marissa Lindquist and Michael Chapman, dissected and translated through numerous mediums to concoct a banquet of immense proportions. Recipes were tested, new degustations imagined, spatial and material configurations explored. I witnessed the ritualistic processes, like a diner in a restaurant anticipating their meal. Sounds of production—slicing, chopping, whisking, stirring, moulding—emanated from the kitchen. The energetic banter of the chefs, Lindquist and Chapman with their eager team of collaborators filled the air. At times I would get a glimpse of the creations, able to taste an ingredient or part of a course, but never the whole. Even the chefs have not fully had that pleasure.

A banquet has now been crafted for our imaginative and intellectual digestion. Like the scenes from the films it references, the exhibition rituals could be described in a series of evocative vignettes in which we the visitors are the actors in the film. They would hint at moments of scarcity and of excess; of expanse and intimacy; noise and quiet; of repulsion and seduction. We are invited into this exhibition – to experience and perform.

Kate Goodwin is Professor of Practice, Architecture at the University of Sydney the Curator of Tin Sheds Gallery.

They pushed the straw around with a pole and found the hunger artist in there. “Are you still fasting?” the supervisor asked. “When are you finally going to stop?” […] “Because I had to fast. I can’t do anything else,” said the hunger artist. “Just look at you,” said the supervisor, “why can’t you do anything else?” “Because,” said the hunger artist, lifting his head a little and, with his lips pursed as if for a kiss, speaking right into the supervisor’s ear so that he wouldn’t miss anything, “because I couldn’t find a food which I enjoyed. If had found that, believe me, I would not have made a spectacle of myself and would have eaten to my heart’s content, like you and everyone else.” Those were his last words, but in his failing eyes there was the firm, if no longer proud, conviction that he was continuing to fast.

—Franz Kafka, The Hunger Artist

Kafka, Frank. ‘The Hunger Artist’. Die neue Rundschau, 1922.