I am delighted to welcome an exhibition devoted to the work of internationally renowned British painters, Sir Christopher Le Brun and Charlotte Verity to The Gallery at Windsor. Christopher held a solo exhibition here in 2017, when he was President of the Royal Academy of Arts. It is a great pleasure to have Christopher back in Windsor to exhibit for a second time, and to Charlotte for her first.

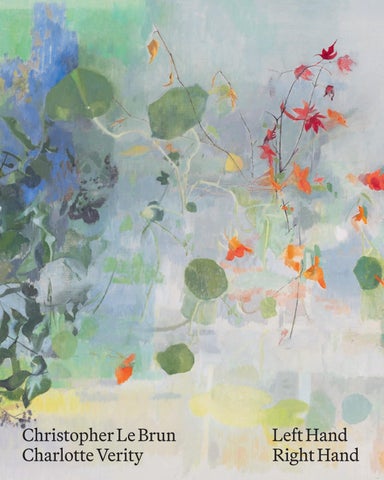

Meeting at the Slade School of Fine Art, London in the 1970s they have since developed a rich artistic dialogue arising from years of shared experience, which is expressed by distinct painterly sensibilities. Le Brun’s work is led by his imagination, revealing a commitment to the essential pleasure of painting for its own sake, its processes and physicality. By contrast, Verity’s lucid compositions, born from hours of close observation and intense looking, distil a precise yet capacious vision of the world. Together, this exhibition will introduce you to how collectively exceptional their work is.

Robin Vousden, a highly celebrated curator, former gallery director and long-time friend of the artists, has worked closely with them, on this, their first major joint exhibition. His insightful and engaging essay for this catalogue draws fascinating connections between them and a wider historical context.

To coordinate an exhibition at this level requires an expert team. I extend thanks to my staff at Windsor, particularly Jane Smalley, to the albertz benda gallery in New York, to Nicola Togneri our exhibition coordinator and Mark Thomson for designing this wonderful catalogue, his sixth publication for The Gallery at Windsor.

Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to Christopher and Charlotte for embracing our invitation to exhibit together. This unique show promises to be full of personal observation, profound connection, and aesthetic discovery.

I was pleased to be called by Christopher Le Brun in the summer of 2024. Pleased and surprised, for he was asking if I could be involved with an exhibition of paintings by Charlotte Verity and him, proposed for The Gallery at Windsor for early spring, 2025. Christopher and I have known one another for some forty years, though our paths cross infrequently. They do so most often in the context of the Royal Academy in London. Le Brun was President of the Royal Academy for eight years from 2011 until 2019. He was knighted in 2021, so is now Sir Christopher Le Brun, PPRA. The painter Charlotte Verity, Le Brun’s wife and partner since the 1970s, is now Lady Le Brun.

Forty years ago, working on an exhibition of paintings from the collection of Granada Television (a major arts sponsor in north-west England), it was exciting to discover that the company had recently purchased two important paintings by Le Brun, Castelfranco 1980 and Trophy (Anger, Reverie), 1982.By including both paintings in the exhibition, we not only demonstrated that this enlightened and imaginative patron was keeping right up to date, but also provided ourselves with a resonant image for the exhibition poster that would be difficult to better.

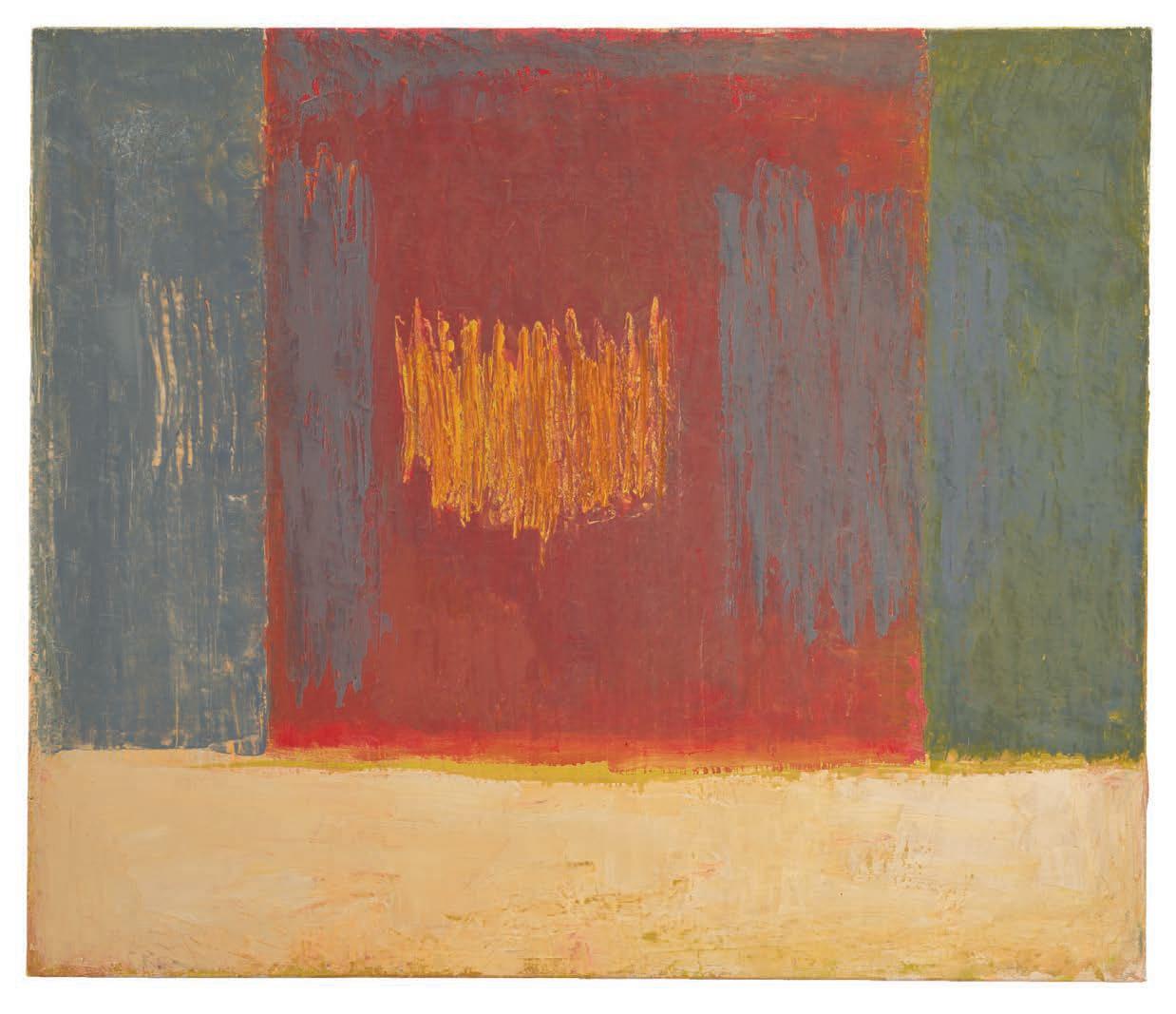

Curiously, Trophy (Anger, Reverie) has returned, in ectoplasmic form, to join the present exhibition. Le Brun’s painting, All Day, 2022, is amongst the artist’s most apparently abstract. The work nonetheless evokes the classical mythological imagery of the earlier painting, made in the year of the Berlin exhibition, Zeitgeist, which (along with other international exhibitions of 1982) brought this English painter’s work to the attention of a world audience.

Charlotte Verity too has been part of my art landscape for decades. She has shown with art-dealer friends (including Anne Berthoud, Madeleine Bessborough and Karsten Schubert).

An early encounter with one of her paintings took place in the home of distinguished curator friends in south London. A moment of epiphany.

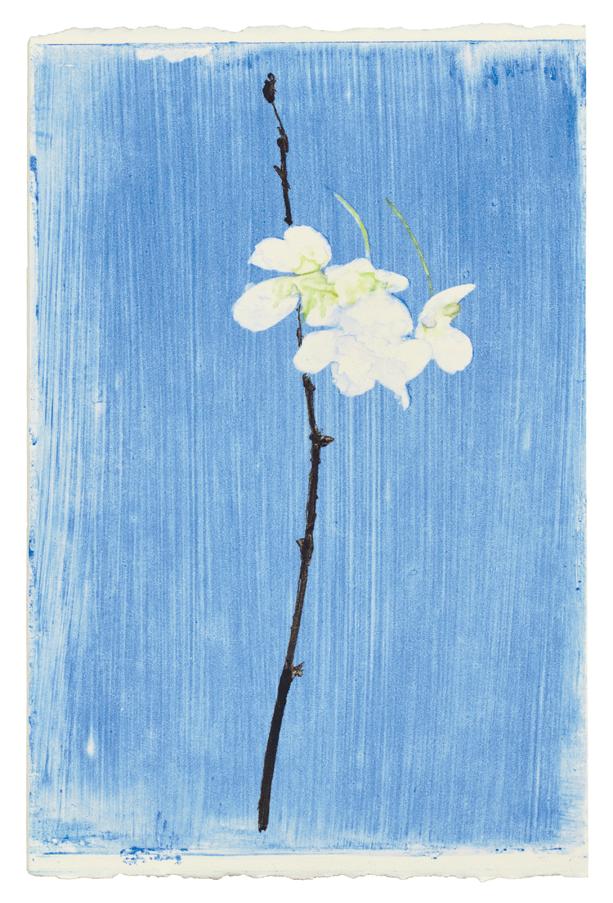

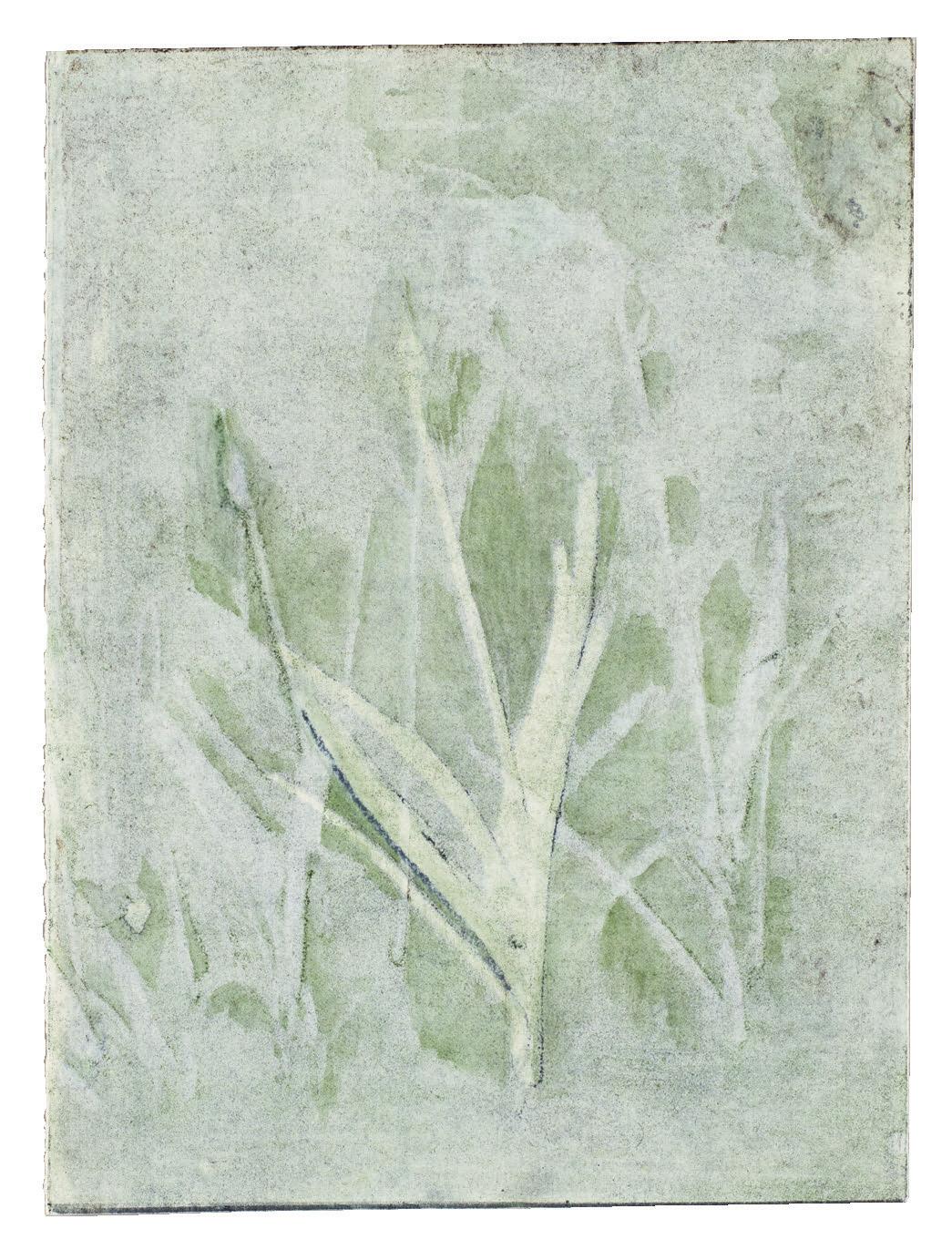

More recently, in 2021, her gallery scored an unintentional victory when the slim publication, Charlotte Verity: Echoing Green arrived on my desk. One look at CV33, 2020, precipitated a telephone call, a visit and a purchase. The booklet from that exhibition, with its wonderful essay and haiku, is beside me as I write; the original watercolour monoprint downstairs, across from a visionary watercolour portrait by Paul Nash of his wife Margaret.

This is the first time that Charlotte Verity and Christopher Le Brun have shown their paintings together. Though they share a home they have separate studios. They are both painters, draughtsmen and printmakers. (Le Brun makes sculpture too, though not shown here).

Verity’s paintings, monotypes and drawings originate from an intense scrutiny of the natural world. Flowers and plants, stems and leaves are observed and recorded in the studio and en plein air. The artist has devised a means of capturing sunlight and sky that brings another energy to the work. Memories of earlier art and of poetry, and the associations that both bring with them, are also invoked. It is this elusive, flickering, precise but restless quality that renders these paintings so special and so moving.

It is this phenomenon, this summoning up of image and word from the realms of art, music and poetry, that connects Verity’s work to that of Le Brun. There is an implicit monumentality in

his paintings, with their multiple references to archetypes in both art and letters. These paintings are not depictions, nor representations, but abstractions. He creates other forms of knowledge through invention that feed the imagination and drive each painting to completion. The artist cannot tell us ‘I have seen this’, but only ‘I believe this to be true’.

Poetry is a stream that flows through the lives and works of both these painters. The discipline, the lyricism and the rigour of verse are never far away. Anselm Kiefer has written: ‘I think in images. Poems help me to do this. They are like buoys in the sea. I swim to them, from one to the next; in between, without them, I am lost.’1 Le Brun and Verity might say as much with equal truth.

What follows is a kind of journal, an account of studio visits to look at the paintings, a visit to the artists’ home and studios in the country, and return trips to Camberwell to set out loose-leaf “storyboard” collages on the studio floor. Word and image are pieced together, almost like a quilt, as we look for connection, illumination and understanding.

I am most grateful to The Hon. Hilary M. Weston for the invitation to co-curate this exhibition and to contribute to the book that accompanies it.

Three friends have helped with the introductory text, “all is always now”. They are Sophia Kennedy-Wilson, Louise Vousden and Stephen Waddell. Their encouragement and support have been invaluable.

Another friend, Edmund de Waal, has most generously agreed to the reissue of his essays about each artist, first published by Ridinghouse in 2014 and 2016.

In the artists’ studios, Joseph Goody has provided access and insight.

Thanks above all to Charlotte Verity and Christopher Le Brun. It has been a privilege to spend time with their paintings and a pleasure to be allowed to think and write about them.

Since T. S. Eliot has lent the pages that follow their title, let us give him the last word here as well:

And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.2

1 Anselm Kiefer, acceptance speech, 2008 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, Paulskirche, Frankfurt am Main, 19 October, 2008.

2 T. S. Eliot, ‘Little Gidding’, Four Quartets 1942.

wednesday 9 october 2024 Camberwell

‘“Oh, it remembers you, you’ve been here before”

I had been there before.’2

Sophia and I are in Christopher Le Brun’s Camberwell studio. We are checking our internet connection. We have printed out and placed photographs and photocopies on the paint-splattered floor. They are arranged into two groups, one for each artist: Charlotte Verity on the left, Christopher Le Brun on the right.3 Our idea is better to understand the nature and scale of the exhibition of their paintings, which is to open in Windsor, Florida in late January 2025.

I forward by email pictures and poems to Sophia to print out. We are using these images and texts to build ‘storyboards’ for each artist. We are particular about which images and texts go together. There is some overlap. A photocopy of a Samuel Palmer etching appears twice, once for each artist. Another Palmer print, a wood engraving, is amongst the Le Brun images. Odilon Redon appears on both sides of the room, a black and white lithograph to the right with Le Brun, a colourful pastel to the left with Verity.

The work is intense, and fun. A first pictorial layout is done. This is revised each time we get new photocopies out. New relationships appear. New images, new words come to mind. Maybe these notes, this gathering of passing recollections and responses, will serve as a kind of introduction to the Windsor exhibition?

Le Brun has stopped by to check up on us. We appear to have a green light so far. We should add an image by Claude Lorrain. Also Samuel Palmer’s etching The Sleeping Shepherd; Early Morning

monday 2 september 2024

Camberwell

First studio visit.

There are paintings to see by both artists. Others are already in New York, perhaps on their way to Florida. Some, Verity’s for the most part, are in Somerset. We have good images of everything.

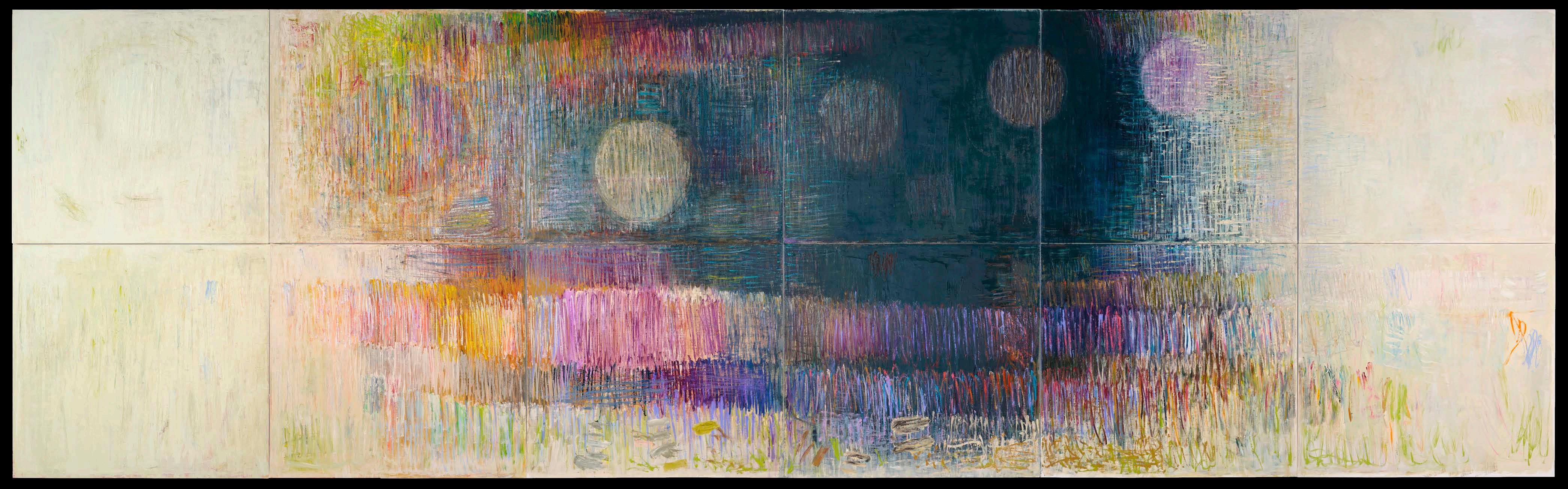

Le Brun’s new multi-panel painting, Phases of the Moon IV, is hanging, in daylight, on the end wall of the studio. This is not one canvas, but twelve, each roughly square, arranged two up and six across. They create a panorama measuring some six and a half by nearly twenty-two feet.

Phases of the Moon IV is, at one and the same time an invention, an abstraction, a memory and a panoramic landscape. The oil paint is applied as though the work were a gigantic drawing. In places it is almost scribbled. The mark-making is rapid, repetitive. Often (Le Brun confirms) paint is squeezed straight onto the canvas, the soft metal top of the open tube serving as applicator.

The title is a literal one. We appear to be watching the phases of the Moon as it orbits the Earth. Narrative moves from noon to noon, left to right, via afternoon sun through dusk to darkness, from civil dawn to sunrise. Finally the bright whiteness of midday returns. A smaller, slightly earlier painting All Day, 2022, appears with hindsight to prophesy this white abstraction, this glare. The cycle begins again, a celestial folk dance in paint.

The impression created is monumental, musical, romantic, scientific, theatrical. The painting is an invocation, calling upon many archetypes, histories and mythologies to achieve its impact. Phases of the Moon IV takes its place in a continuum. Milestones from the history of British art could include works by Blake, Palmer, Martin, Turner, Nash, Moore. A later ‘storyboard’ will illustrate all of them.

Michael Andrews, another Slade-trained artist, provides a useful recent point on this trajectory. His painting, Laughter Uluru (Ayers Rock), The Cathedral I, 1985 was once described as resembling a gigantic watercolour, just as Phases of the Moon IV evokes a crayon drawing on a monumental, cathedral-like scale.

Another ‘storyboard’ of photocopies, French painting mostly, reproduces paintings by Poussin, Claude, Courbet, Friedrich, Böcklin, Monet, Cézanne … I wonder out loud about Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. His monumental, classical landscapes, quiet, recognisable, populated but curiously empty of meaning, seem to prefigure this series of Le Brun’s. The artist, passing, agrees.

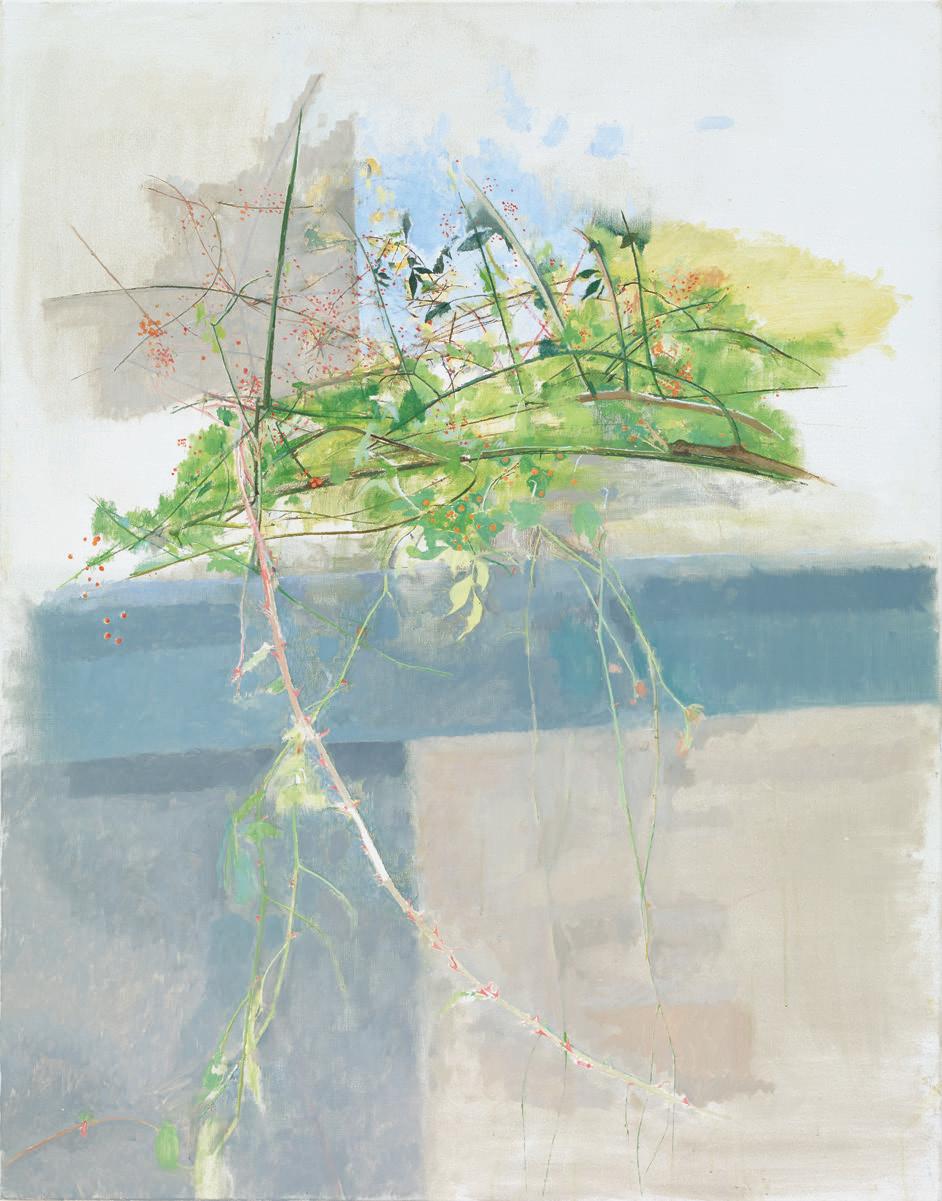

Pleased, I cross the landing to the other studio, and to Verity’s paintings. These are to move from London to the artist’s new studio in Somerset. I will see them again soon.

The first painting we look at, Glance, 2021, is one of the largest destined for the Windsor show.

While Le Brun’s paintings are inventions, Verity paints what she sees. We are told what is in the studio, often on a kind of ‘nature table’, and what is outside, either seen from a window or out of doors. Garden flowers and plants, glass containers to hold them, and the water that keeps them alive, are shown with other objects so that planes and surfaces become traps for colour and light, refractions and shadows. Translated into paint, the effect is hallucinatory. Clear glass vessels become no more than a glitter, a twinkling, a moment captured. The artist depicts light and colour, time and space. Dead plants are replaced. Blue skies are not skies at all, just blue, as sunlight is yellow.

An artist friend of mine, reviewing an early draft of this text, spoke of the dreamlike, liminal, pictorial space created by Verity – lyrical marks that are at once brushstrokes and forms of resemblance. This lovely description seems too good to leave behind, so is stolen here.

For all Verity’s painstaking endeavours, her results are insistently poetic, visionary. We have left Puvis de Chavannes, only to find Odilon Redon.

Why Odilon Redon? Because in Glance, 2021, a burst of incandescent orange nasturtium petals, crimson maple leaves and floating green foliage, we recall nothing so much as his late hallucinatory flower paintings.

Once entered into, Verity’s imaginative world becomes pervasive. A recital of songs by Gabriel Fauré at the Wigmore Hall in September begins with the composer’s setting of Victor Hugo’s celebrated poem Le papillon et la fleur. Both words and music seem so attuned to Verity’s painterly voice that we reproduce the poem here complete, in French and in English translation.

La pauvre fleur disait au papillon céleste:

Ne fuis pas!

Vois comme nos destins sont différents. Je reste, Tu t’en vas!

Pourtant nous nous aimons, nous vivons sans les hommes Et loin d’eux, Et nous nous ressemblons, et l’on dit que nous sommes Fleurs tous deux!

Mais, hélas! l’air t’emporte et la terre m’enchaîne. Sort cruel!

Je voudrais embaumer ton vol de mon haleine Dans le ciel!

Mais non, tu vas trop loin! – Parmi des fleurs sans nombre Vous fuyez, Et moi je reste seule à voir tourner mon ombre À mes pieds.

Tu fuis, puis tu reviens; puis tu t’en vas encore Luire ailleurs.

Aussi me trouves-tu toujours à chaque aurore

Toute en pleurs!

Oh! pour que notre amour coule des jours fidèles, Ô mon roi, Prends comme moi racine, ou donne-moi des ailes Comme à toi!

victor hugo | The butterfly and the flower

The humble flower said to the heavenly butterfly: Do not flee!

See how our destinies differ. Fixed to earth am I, You fly away!

Yet we love each other, we live without men And far from them, And we are so alike, it is said that both of us Are flowers!

But alas! The breeze bears you away, the earth holds me fast. Cruel fate!

I would perfume your flight with my fragrant breath In the sky!

But no, you flit too far! Among countless flowers You fly away, While I remain alone, and watch my shadow circle Round my feet.

You fly away, then return; then take flight again To shimmer elsewhere.

And so you always find me at each dawn Bathed in tears!

Ah, that our love might flow through faithful days, O my king, Take root like me, or give me wings Like yours! 4

Another painting by Verity, seen briefly in Le Brun’s studio, and again in Somerset, is Buds, 2020. Here, plant specimens are portrayed as in a laboratory, rather than in a studio. Or maybe as in a primary school, for association and memory invade the visual and emotional space of this quiet painting.

Memories of a country childhood, infant school, nature walks, arranging wild flowers in a jam-jar for a village fete. Singing Together, a radio program for school children, broadcast by the BBC in the summer of 1959, includes a song we all learn:

Once there was a wild rose gay On the moorland growing.

But a careless boy at play

Chanced to see the tempting spray

Which the breeze was blowing. Soft red rose, red rose of May, On the moorland growing.

Said the boy: ‘I’ll pick you now, On the moorland growing.’

Said the rose: ‘I’ll prick you now, That you may remember how Sad I was at going.’

Soft red rose, red rose of May, On the moorland growing.

Roughly then he snatched his prize, On the moorland growing, After this he’ll be more wise; There before his very eyes Blood was freely flowing.

Soft red rose, red rose of May, On the moorland growing.5

We seven-year-olds are singing, in the Berkshire countryside, the poetry of Goethe to the music of Schubert. Some sixty-five years later, looking at this painting by Verity, that summer moment comes to mind.

The farm house and studio in Somerset are a revelation. Not just for their charm and space and warmth, nor for the generous studios newly constructed in adjacent old buildings, but because there, hanging in the living room, are the framed etchings of Samuel Palmer. These prints hang also in this writer’s home. All of them. If poetry is one of the threads that sews the work of these two painters together, maybe Palmer’s etchings are another.

The ‘nature table’ still-life paintings we saw in Camberwell are now in Somerset. Other small flower landscapes, painted en plein air, have made the westward journey too.

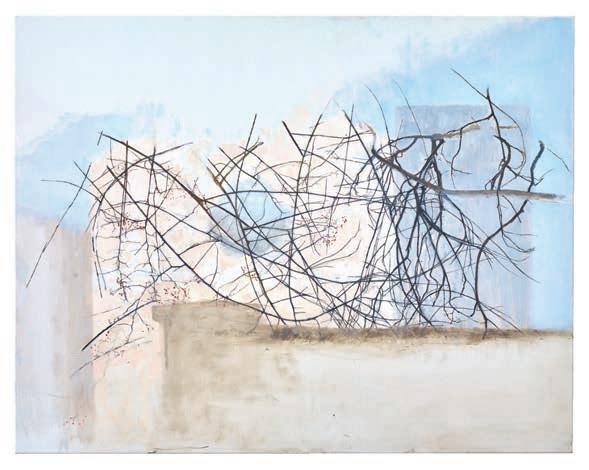

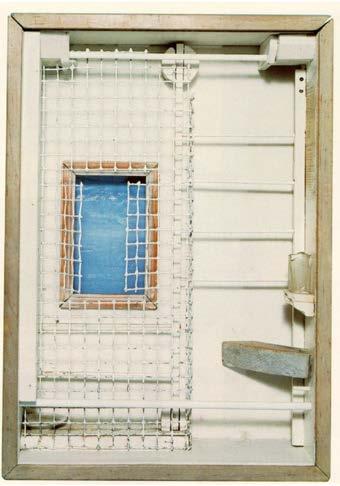

One of Verity’s paintings, My Nest, 2017, takes centre stage in the artists’ dining room. It depicts the outside wall of their London garden and, rising above it, a screen of thorns making a pattern, a lattice of bare and brittle branches beyond which appears the sunlit wall of a church. I love this painting. It is full of ghosts and patterns, like cracks in ice, which articulate and conceal at the same time. It is full of associations too.

On our ‘storyboard’, we have pinned up the still shocking image of the dead Christ from Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Also Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950.

Privately, looking at this painting, I am happier standing in imagination beside Mary Lennox in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, 1911, wondering what happens on the other side of the wall, and whether the robin is sharing a secret.

A second London garden landscape hangs in the painter’s studio. Betula Weeping, 2009–14, like My Nest, shows the world through a cascade of autumn branches that canopies the painting’s surface whilst inviting the viewer into its secret shaded space. An impression of Palmer’s The Sleeping Shepherd; Early Morning, 1857, another dreamer in another bower, also hangs in Somerset.

Back in London, we pin up a photocopy of John Everett Millais’s Autumn Leaves, 1856. Beside it, from a century later, we hang a Pauline Baynes illustration from C. S. Lewis’s The Magician's Nephew, 1955. The drawing depicts the wood between the worlds through which Lewis’s child protagonists find their way to Narnia, whose genesis they will witness. Passing by behind us, I am glad that Le Brun recognises the image from afar.

I write to Verity, hoping with this painting to make another reference to Eliot’s Four Quartets:

Go, said the bird, for the leaves were full of children, Hidden excitedly, containing laughter.6

Her written reply suggests that these lovely lines may be too much for so small a painting to carry. We’ll see.

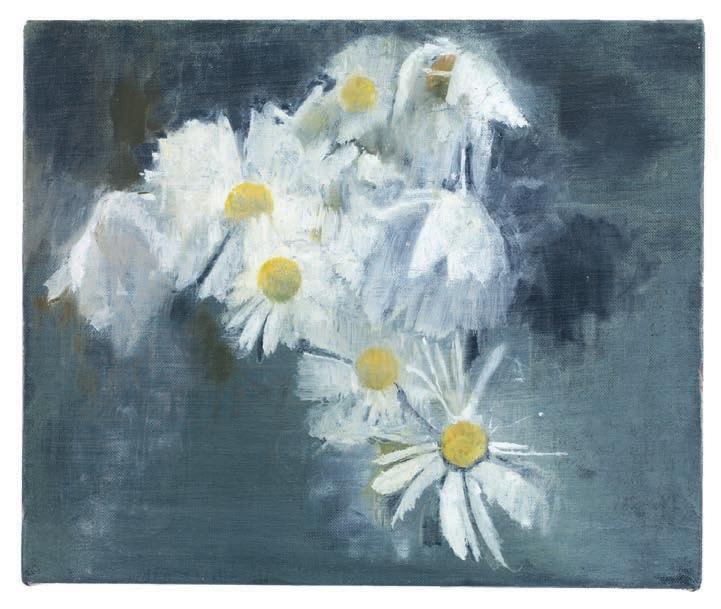

Four small flower paintings have also left Camberwell for Somerset. Painted out of doors, not in the studio, their mood, like their size, sets them apart. Anemones, Daises, Creeper, Plumbago.

The graphic armature of these works, these out-door paintings, is no longer exposed. There is no map nor web to choreograph the viewer’s journey. Instead, figure and ground, flower and foliage, flow together like a painted tapestry.

There’s something else here too. Tricky territory. Images of annunciation, sacrifice, redemption and assumption hover in memory. Maybe all art now worth looking at is somehow sacred?

For our ‘storyboard’, we find images, details of paintings by Bellini, Piero, Velázquez and Cornell. The last image may work less well than Dickinson’s verse, which inspired it:

It might be easier To fail—with Land in Sight— Than gain—My Blue Peninsula— To perish—of Delight—7

wednesday 16 october 2024

Camberwell

Sophia and I are back in the studio. Joseph Goody is there to let us in, but otherwise getting on with his own work. The artists are in Somerset, we guess, or travelling.

The only painting left that will be part of the Windsor show is Phases of the Moon IV. Hanging in an otherwise empty studio, it becomes majestic, operatic, inexhaustible. It is such a rewarding luxury to spend time, days, quietly with one great painting.

In Manchester in 1971, in my second year of reading art history, my housemate would play John Lennon’s newly released album, Imagine, over and over again, into the early morning. We got to know that great work then, as I get to learn this painting now, half a century later. Nothing changes.

Le Brun’s paintings for Windsor are in New York already. Six of them were finished in 2022. Another, Caught, as well as a series of four smaller canvases Small Seasons, are dated a year later. The two most recent paintings, Phases of the Sun II and Phases of the Moon IV were made this year, 2024.

In the absence of the originals, colour photographs of the eight single canvases, as well as the set of four Small Seasons, have

joined the photocopies and pages of poetry on the studio floor. The game of association that we began to play a month ago expands, now that all images are equal. Le Brun’s classical abstractions, his representations (reconstructions perhaps) of emotion and memory, are holding their own in the company of Claude and Poussin; Courbet, Monet and Cézanne; Newman and Rothko.

The recent paintings are not so large, rectangular, three feet high by three something wide. Picture windows – satisfying. The paintings share with Verity’s a not so deep pictorial space that, though now invented rather than observed, is similarly resistant to architecture and to definition. Both artists are painters of light, with all its flickering instability, motion and repose.

The ‘game’ of association continues. How are we to see To and Fro 2022, without conjuring Courbet’s The Meeting? Three figures, now strong yellow patches, a staff to separate the two from the one, artist acknowledged by patron. Above all, the bravura, the confidence of the mark-making: ‘the achieve of, the mastery of the thing’.8

Camberwell

We will not see Le Brun’s Small Seasons until next year. Photographs are almost satisfying, nearly seductive – and puzzling. Spring, Summer, Autumn present few difficulties – the narrative is in the titles and the painting tells its own story. Small Season, Summer in particular feels close to Turner. Maybe we can illustrate one of his Petworth studies as a reference among the plates?

But what about Small Seasons, Winter? Blocks of black impede the eye’s journey into the painting’s space. Memory serves at last. 1995: The Royal Academy (appropriately enough). Nicolas Poussin, The Four Seasons Winter (The Flood), on loan from the Louvre, a not-to-be-forgotten moment for art in London. In Le Brun’s painting, the image is reversed, as though the artist, like the pre-Raphaelites before him, has taken it from the engraving, rather than the oil.

We haven’t seen a transcription before in Le Brun’s painting and will not do so again, or at least never so clearly. This viewer is pleased to have the puzzle solved.

This is our last day in the studio. The artists are travelling. Joseph is about to go away too. The next time we see Phases of the Moon IV will be in Florida.

We have talked a lot about French painting, though both Claude and Poussin are surely as much embedded in the psyches of British painters as in those of their own country. The museums, galleries and private palaces of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales seem full of their work.

Different as their paintings appear to be at first sight, the work of Le Brun and Verity expands and extends an imaginative response to the landscapes of art, memory and nature that is at one and the same time classic and romantic. Their painted language is one of truth to history and to the present.

Poetry is the warp and the weft of this canvas. Poetry, and the poetic images of Samuel Palmer. We found intimations of Verity’s achievement in Hugo’s Le papillon et la Fleur and Palmer’s The Sleeping Shepherd; Early Morning Let us leave this studio with the memory of Phases of the Moon IV as well as Palmer’s The Lonely Tower and Faust’s watchman, with his ‘happy eyes’.9

1 T S. Eliot, Burnt Norton, 1936. And the end and the beginning were always there Before the beginning and after the end. And all is always now.

2 Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisted 1945, Book One, ET IN ARCADIA EGO I had been there before; knew all about it.

3 Le Brun is left-handed; Verity right-handed.

4 Victor Hugo, Le papillon et la Fleur 1861, translation by Richard Stokes, from A French Song Companion, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

5 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Wild Rose, 1789. Music, Franz Schubert. Translation by E. Fiske, published in Singing Together, Summer 1959, ‘The Oxford School Music Books’, Teacher’s Manual Senior Part I, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6 T S. Eliot, Burnt Norton, 1936, First part of Four Quartets 1942.

7 Emily Dickinson, It might be lonelier date unknown.

8 G erard Manley Hopkins, The Windhover, 1914.

9 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Lynceus der Thürmer, auf Fausts Sternwarte, 1833. Translation ‘Szene aus Faust’ by Richard Stokes from the Book of Lieder London: Faber & Faber, with thanks to George Bird, co-author of The FischerDieskau Book of Lieder London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

johann wolfgang von goethe | Lynceus, der Thürmer, auf Fausts Sternwarte singend

Zum Sehen geboren, Zum Schauen bestellt, Dem Thurme geschworen, Gefällt mir die Welt. Ich blick’ in die Ferne, Ich seh’ in die Näh’ Den Mond und die Sterne, Den Wald und das Reh. So seh’ ich in allen Die ewige Zier, Und wie mir’s gefallen, Gefall’ ich auch mir. Ihr glücklichen Augen, Was je ihr gesehn, Es sei wie es wolle, Es war doch so schön!

johann wolfgang von goethe | Lynceus, the watchman, singing on Faust’s observatory

I am born to look, I am employed to watch, I am loyal to this tower, I love the world. I look into the distance, and see near by, the moon and the stars, the forest and the deer. and in all of them I see eternal beauty, and as the world delights me, so I am filled with delight. oh, happy eyes, may all that you’ve seen remain as it was For it was beautiful!

i What does it mean to return to a subject, to go back to paint these few snowdrops in a glass, an apple or two, a branch from a birch tree with its just-clinging leaves? To mark a place out as your terrain, a windowsill, say, and then come back and see how the light changes, thickens, how the dusk clouds the spaces, how the shift of hours takes you away into yourself. Returning is hard work. There is no grandeur in looking hard at this, your self in the world. It is necessary.

You are thinking aloud about time.

ii

These paintings are about looking again.

John Clare looks at his landscape, the fields and woods of Northamptonshire, with longing. He looks at what was present in his childhood and what exists now. He charts minutes and hours and seasons and years, the birds and trees and flowers, a hedge, a copse.

‘I love the lone green places’, he writes, knowing what kinds of silences are necessary to bring thoughts into clarity, to bring about the distillation of many things into singularity, bring an image alive.1

His poetry is full of birds’ nests. The hen’s and the quail’s, the firetail’s, the nightingale’s, the thrush’s, the yellowhammer’s. This makes sense. You need to be attentive to how a tree changes with a movement to find a nest. You need scrupulous attention to discover what it is – ‘Five eggs, pen-scribbled o’er with ink their shells/ Resembling writing scrawls’,2 he notices of the marks of the eggs of the yellowhammer, ‘ink-spotted over shells of greeny blue’ of the thrush.3

A nest is a kind of sculpture too. A holding together, a structure tracing a bird’s traverse of these few miles. It is an idea. Clare wants to hold the year in language. He writes The Shepherd’s Calendar marking this place in the world in all its particularity, its fullness.

In these paintings by Charlotte Verity the seasons’ ebb is marked. They are a calendar, a series of poems tracing one full moment and then another.

iii

These paintings are alive to structure. There is a matrix of twigs and stalks and branches and stems. These lines have always been present in her work but now the skeletal is coming into view, becoming a subject in itself.

This toughness reveals so much.

These structures are fiercely exact. And they abstract. These branches are lines of thoughts, of nerves dividing again and again. Calligraphies, dendrites, a kind of musical notation, markings on a wall, into a wall, in mid-air.

In Spent Stems they are stripped back, essential in their wintriness. To understand winter, wrote Wallace Stevens, you need ‘a mind of winter’.4

These lines hum.

iv There are other kindred painters of windowsills and ledges, an open window. I think of David Jones and Winifred Nicholson. These are liminal spaces in paintings, a bridge between worlds. They have nothing to do with domesticity. They are about the edge of the world – the place where things change. Outside is a street, a hillside, the sea, an altogether elsewhere. Inside is your mind. You paint this edge.

Say it again. They have nothing to do with home.

v Here in these paintings is temporality.

Pears are good for this, each moment from hardness to deliquesence a slight movement. Pears swelling, pears scattered across the ground, a pear’s last leaves barely hanging onto a branch. These are paintings of lateness. Daisies in September, spring flowers on the cusp in Sky-Blue Spring, golden fragility in Betula Weeping. This is part of their beauty.

It is part of our language, this rhythmic falling away. ‘For all flesh is as grass, and all the glory of man as the flower of grass. The grass withereth, and the flower thereof falleth away’.5 These cadences are so quiet.

vi You cannot come and just do it. You need to have seen it through. These paintings are about waiting.

Height of Summer feels like an hour, the hour where you look away and look back and a flower has shrugged, the petals drifted down. Town Light Winter feels like days.

These paintings distil. They are exacting, beautiful, tough. Wait with them.

Notes

1 John Clare, ‘The Maple Tree’, in Eric Robinson and David Powell (eds), John Clare: Major Works, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004, p.423.

2 John Clare, ‘The Yellowhammer’s Nest’, The Rural Muse, Whittaker & Co., London, 1835, p.79.

3 John Clare, ‘The Thrush’s Nest’, ibid. p.128.

4 Wallace Stevens, ‘The Snow Man’, Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, vol.xix no.1, October 1921, p.4.

5 1 Peter 1:24, King James Version.

I am thinking of angels. I am in Christopher Le Brun’s studio, three flights of stairs up in a south London warehouse, and there is light from huge skylights above and light from windows before and behind me, and a recent painting almost five feet square is propped against a wall in front of me. It is April and the weather has turned on itself again so that the day is failing.

The painting is an exhilarated cloud of reds and carmines. It is called Seraphim (p.70). It is intensely beautiful and I am thinking of the moments at the opening of Rilke’s First Duino Elegy (1923), when the poet cannot bear the transparency of his life:

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angelic Orders? And even if one were to suddenly take me to its heart, I would vanish into its stronger existence. For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror, that we are still able to bear, and we revere it so, because it calmly disdains to destroy us. Every Angel is terror. And so I hold myself back and swallow the cry of a darkened sobbing. Ah, who then can we make use of? Not Angels: not men, and the resourceful creatures see clearly that we are not really at home in the interpreted world. Perhaps there remains some tree on a slope, that we can see again each day: there remains to us yesterday’s street, and the thinned-out loyalty of a habit that liked us, and so stayed, and never departed.

Whose angels are these? Blake’s angels down the road from the studio in Peckham Rye, or aristocratic ones in the rarefied thermals above the cliffs at Duino, or the controlled echoes of Prospero’s Island? How English is this call to annihilation? Can you trust these voices?

You cannot choose when to be visited by Seraphim, but you can choose to avoid the ‘thinned-out loyalty of a habit/that liked us, and so stayed’. Go up the stairs to your studio every day, but don’t expect to know what will happen. It may not be welcome but you will be alive and you will find that you are altogether elsewhere. The first line of this First Elegy came in a revelatory moment, the words caught in the wind. Then the Elegies took ten years to complete.

above/below

Le Brun is too deeply embedded in Poussin not to understand the structure of gesture in a painting – the hands raised in supplication from below, the open benevolence of a gesture from above, the openness of welcome, the movements of disavowal. There is a narrative embedded in these pictures no matter how scuffed, erased, graffitied, annihilated.

There is falling – like Icarus, like Danaë, like Peter Lanyon on the air currents above Cornwall. And there is the setting of the sun. Here, the light and the shadows are dispersed across the picture plane. That is not quite right: here in Rose, 2014, is a fire-starter, a

conflagration setting an image alight. Here is Painting as Sunrise, 2013, the idea of starting again, making sense of a new day. And here is Choir, 2013. These are raising movements of thought and sound, up and away like the smoke of a burnt offering in the far distance, smoke from a travellers’ fire telling you how far you have come.

It makes me think of a drawing by Cézanne, The Apotheosis of Delacroix (1890–94) in which the painter is gathered into the heavens by angels as the earth-bound comrades left behind raise their brushes in salutation. It is affectionate, wry and necessary to let the old man go.

There is a lot of letting go in these paintings.

When is a painting finished? Do you hover over it, or is it, as Auden said of a poem, ‘never finished, only abandoned’? How about the title? Is it finished when the name, the luggage label, is put round its neck and it is moved towards the door? Is it finished on the gallery wall?

Looking at the dates on the backs of the canvases, some have taken two years, some a few days. I like this. It is worrying when there is a pattern that is too obvious, a sense of how to measure labour to scale. He talks of coming in and finding that it is too beautiful, that there is a cadence to the lyricism that isn’t quite right. Or that there is a disordering that needs to happen, a taking up of colour to make new marks over the ground that has been prepared.

Here is Swan, 2014, a field of whites, more icy-blues than Ryman-whites. It is a huge canvas, nearly nine feet high. And there are strong cobalt markings coming down, falling like glacial water across the whole plane. It is Herrick’s Delight in Disorder (1648) in which he says that we get most pleasure when we know what is lost and what is gained when structure is loosened, when we sense ‘a wilde civility’.

There is both wildness and civility in this body of work, Dionysian and Apollonian markings.

Swan is a moment of letting go. It is the apprehension, not of Whistler’s fireworks showing up the stars, showing off the height of the London skies, the whole painting-as-performance-shtick, but the moment afterwards. Everyone turns away. Conversation starts again. No one is looking at the sky any more, but this is where it happened. Paint that. It is far more interesting, more sublime.

scriabin

I ask about music in the studio. The question of what you listen to – the easiest question number one of the interviewer – gets refracted back to me. What do you hear when you listen? Do you hear structures, do you hear ideas, do you sense how improvisation changes? Do you listen to lose yourself? Do you paint music? Can you see what I have been listening to?

There are core composers. Bach I could have guessed, and Schoenberg is no surprise, since his collected essays lies brokenspined on the floor. Both keep a cerebral watch on how to map the flowing of an idea, its doing and undoing and redoing.

Schoenberg’s ‘colour crescendo’ in the storm scenes in his opera Die Glückliche Hand (1910–13) might seem over prescriptive, alliances of tone and emotion too carefully stipulated, but at least he thought in colour.

Walton, 2013, and Scriabin, 2013–14, are titles for works in the exhibition. But Walton and Scriabin and Delius and Shostakovich are part of his tremendous list, because no one is going to make that up in a hurry. Too odd. Too orchestral. And the wrong period: too romantic by far, lacking in avant-garde kudos. I worry over the list. Scriabin is a synaesthete but that doesn’t get me very far. Walton was an exile, an Englishman abroad, an Englishman who didn’t fit in. That doesn’t help either. I write a note to self: he likes music.

scale

Why are they this big? They are the scale of doors. ‘Doors’ sounds too domestic: they are gates. He has never worried about painting big pictures in the past, nor about making proper sculpture to sit in a landscape. His genres, history painting, history sculpture, demand scale. These new paintings feel appropriately huge for whatever new genre they are avoiding.

et in arcadia ego

There is an English classicism that has been lost, gets rediscovered and lost again every couple of generations. Why should English classicism be thought of as melancholic? What irritates is not just that the reading of the landscape as Arcadian implies some lapsarian moment, a narrative of decline, it is that classicism gets claimed as nostalgia. A pall hangs off it, yellowing the emotion. It is over-varnished. I look at Atlas (Shelley), 2014, and feel the radicalism in Shelley, the toughness in taking on the beginnings of story-telling, the feeling that you don’t know what is going to happen, that you might not like the place you are taken to.

Le Brun’s work over 30 years circles classicism and neoclassicism, both the source and the return to source. His habitation of these stories, these landscapes, the light of the south shows real and forceful concentration. He talks of a recent generation of painters and their adoption of narrative: the ‘things that they regard as available I regard as difficult’. And ‘to depict something needs thought’. Imagery isn’t downloadable. He can walk you around Troy. His work is much darker in spirit than is allowed. The horse that has wandered out of a Tennyson Idyll is the same horse that has been abandoned after some terrible battle. Where is the rider? The painter and poet David Jones said that the horses wandering the Black Mountains on the borders of Wales were Arthur’s defeated cavalry. And the wood from which it emerges is part of a North European forest, an Altdorfer smudge of pines that holds something much scarier, some memory of legend where something has happened.

Le Brun has always been closer to Altdorfer than Constable. The matter of England is a thoroughly Continental issue, much too serious to be left to the English.

a story Christopher tells me that when Turner visited David it was a disaster.

Ad Reinhardt Painter and writer of statements, wrote a statement for the catalogue of the exhibition The New Decade, held at the Whitney in 1955:

Painting is special, separate, a matter of meditation and contemplation, for me, no physical action or social sport. As much consciousness as possible. Clarity, completeness, quintessence, quiet. No noise, no schmutz, no schmerz, no fauve schwarmerei. Perfection, passiveness, consonance, consummateness. No palpitations, no gesticulation, no grotesquerie. Spirituality, serenity, absoluteness, coherence. No automatism, no accident, no anxiety, no catharsis, no chance. Detachment, disinterestedness, thoughtfulness, transcendence. No humbugging, no button-holing, no exploitation, no mixing things up.

He was obviously cross when he wrote it, cross with New York and critics and painters and curators and all that gestural emotion floating around and being valorised as significant and new. But I like the bit about ‘no palpitations’. How you can be in emotion and paint without noise and schmutz is difficult. One of the reasons why these paintings are so strong is that they don’t button-hole you, but you cannot walk past; they do mix things up, but are coherent.

Warner Road se5 at dusk

When I leave the studio it is almost dark. This is the moment entre chien et loup, when one thing becomes another, where to discern which animal is which becomes difficult, then more difficult, then an impossibility. There is a danger in this moment, a threshold of sorts. A fox stops outside the corner shop at the end of the road, one paw raised, the air electric. We look at each other appraisingly.

And off he goes into his own story, not looking back, as English as can be, and as wild.

Sir Christopher Le Brun (b. 1951, UK) is one of the leading British painters of his generation, celebrated internationally since the 1980s, who makes both figurative and abstract work in painting, sculpture and print. He was an instrumental public figure in his role as President of the Royal Academy of Arts in London from 2011 to 2019, and was awarded a Knighthood (Knight Bachelor) for services to the Arts in the 2021 New Year Honours. Recently, Tate, London, the Museum of Contemporary Art & Urban Planning (MoCAUP), Shenzhen, and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford CT, have all acquired major works.

2024

Phases of the Moon Lisson Gallery, Beijing, China Unenclosed, Academicians’ Room, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK

2023 Swan Ritual, albertz benda, New York, USA

2022 Making Light, albertz benda, Los Angeles, USA Momentarium, Lisson Gallery, London, UK

2021

A Sense of Sight, Abstract Work 1974–2020, Red Brick Art Museum, Beijing, China

2020 Figure and Play, albertz benda, New York

Recent group exhibitions

2024 Right Hand, Left Hand, Lyndsey Ingram, London, UK New Collection Display, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, USA Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK

2023 New Acquisitions, Southampton City Art Gallery, UK Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK

2022

The Endless Summer, albertz benda & Friedman Benda, Los Angeles, USA Liljevalchs 100 years, Jubilee 2021, Liljevalchs Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden

2021 Transcendence and Rén Jīan, Su Xinping and Christopher Le Brun, MoCAUP, Shenzhen, China

Selected public collections

Art Gallery of New South Wales, AUS British Museum, UK

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Museum of Contemporary Art & Urban Planning (MoCAUP), PRC

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA

Museum of Modern Art, NY Tate, UK

Victoria & Albert Museum, UK

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, USA

Yale Center for British Art, USA

Public collections

Arts Council of England, UK

British Museum, UK

Derby Museum and Art Gallery, UK

Deutsche Bank, UK

Garden Museum, UK

Government Art Collection, UK

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, USA

Sir John Soane’s Museum, UK

Tate Education, UK

University College London, UK

Charlotte Verity (b. 1954, Germany) is a British artist who has honed a lucid and highly specific visual process to attain truth in her work. Close looking is at the heart of her practice. For decades, she has immersed herself in nature, either by painting and drawing out of doors or by bringing elements of it into her studio to observe. Her paintings and prints track the seasons and the passing of time. Since graduating from the Slade, she has exhibited extensively and undertaken residencies including at Towner, Eastbourne; The Garden Museum, London and Flatford, Suffolk. She has been on the faculty of The Royal Drawing School since 2001.

Recent solo exhibitions

2024

So It Is, Tom Rowland, London, UK

2021

Echoing Green I, Karsten Schubert, Room 2, London, UK

Echoing Green II, Karsten Schubert, Room 2, London, UK

2019

The Seasons’ Ebb, New Art Centre, Wiltshire, UK

2018 In Their Garden, Garden Museum, London, UK

Recent group exhibitions

2024

Right Hand, Left Hand, Lyndsey Ingram, London, UK

The Shape of Things, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, UK

Contemporary Collecting: David Hockney to Cornelia Parker, The British Museum, London, UK Display of Paintings, the Design House, New Art Centre, Wiltshire, UK

2023

Display of Gallery Artists, Tom Rowland, London, UK

2022 Kill or Cure, Wolfson College, Cambridge, UK Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK

2021

ATM21, Manchester Poetry Library, Manchester, UK Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK Drawing Biennial 2021, The Drawing Room, London, UK

Works on pages: back cover, 2–3, 21, 22, 23, 26–28, 69, 70, 71, 72, 75, 76, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 85

© Christopher Le Brun christopherlebrun.co.uk

Works on pages: front cover, 8–9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 20, 30–31, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 43, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 65 © Charlotte Verity charlotteverity.co.uk

All rights reserved, DACS 2025

All photography by Stephen and Jackson White

Reference images

p. 15: Samuel Palmer (dates), The Sleeping Shepherd: Early Morning, 1857. (public domain). Image courtesy Princeton University Art Museum.

p. 19: Giovanni Bellini and workshop, Angel of the Annunciation and Virgin Annunciate, c. 1500 (detail). (public domain). Image courtesy Mongolo1984, via Wikimedia Commons.

p.19: Piero della Francesca, The Baptism of Christ c. 1448–50 (detail). (public domain). Image courtesy The National Gallery, London.

p. 20: Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, The Crucified Christ, c. 1632 (detail). (public domain). Image courtesy Museo del Prado, via Wikimedia Commons.

p. 20: Joseph Cornell, Toward the Blue Peninsula: for Emily Dickinson, c. 1953. (public domain). Image courtesy Artchive.

p. 21: Gustave Courbet, The Meeting or ‘Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet’, 1854. (public domain). Image courtesy Musée Fabre, via Wikimedia Commons.

p. 22: Nicolas Poussin, The Four Seasons (Les Quatre Saisons), Winter (The Flood), 1660–64. (public domain). Image courtesy Alamy.

p.23: Claude Lorrain, The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648. (public domain). Image courtesy The National Gallery, London, via Wikimedia Commons.

p. 25 Samuel Palmer, The Lonely Tower, 1879. (public domain). Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Texts

‘all is always now’ © Robin Vousden, 2024 ‘Charlotte Verity’ © Edmund de Waal, 2014 ‘Christopher Le Brun: Above/Below’ © Edmund de Waal, 2016

Quotes and Poetry

p. 13: Anselm Kiefer, acceptance speech, 2008 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, Paulskirche, Frankfurt am Main, 19 October, 2008. Reproduced with kind permission Anselm Kiefer.

p. 13: T. S. Eliot, ‘Little Gidding’, Four Quartets, 1942. (public domain)

pp. 14, 18: T. S. Eliot, ‘Burnt Norton’, Four Quartets 1936. (public domain)

p. 15: Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited 1945, Book One, ET IN ARCADIA EGO. (public domain)

pp. 16–17: Victor Hugo, Le papillon et la Fleur 1861, translation by Richard Stokes, from A French Song Companion, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Reproduced with kind permission Richard Stokes.

p. 17: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Wild Rose, 1789. Music, Franz Schubert. Translation by E. Fiske 1955–56, published in Singing Together Summer 1959, ‘The Oxford School Music Books’, Teacher’s Manual Senior, Part I, Oxford: Oxford University Press. (public domain)

p. 18: Emily Dickinson, It might be lonelier, date unknown. (public domain)

p. 21: Gerard Manley Hopkins, The Windhover, 1914. (public domain)

p. 25: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Lynceus der Thürmer, auf Fausts Sternwarte, 1833. Translation ‘Szene aus Faust’ by Richard Stokes from the Book of Lieder, London: Faber & Faber, with thanks to George Bird, co-author of The Fischer-Dieskau Book of Lieder, London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. Reproduced with kind permission Richard Stokes.

Robin Vousden worked as a curator at the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester from 1975 to 1984.

He joined Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London as a director in 1984, working there until the gallery closed in 2001. After two years in Paris and New York with Marian Goodman Gallery, Robin returned to London, joining Gagosian in 2004 and working there until his retirement in 2022.

Robin Vousden served as a trustee of the North West Essex Collection Trust from 2018 to 2024. He has been a trustee of Pallant House Gallery, Chichester since September 2023.