Topic: 29 NOV 2024

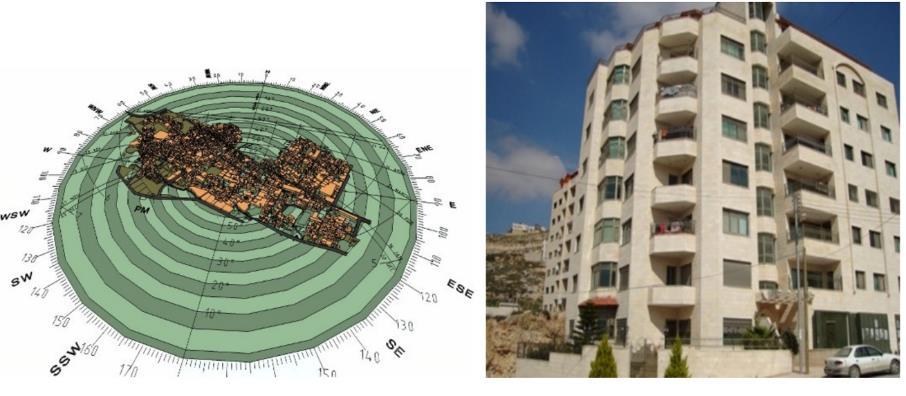

The pressing challenges of climate change demand the integration of sustainable methods into architectural design. Vernacular architecture offers critical insights through its climate-responsive strategies, utilization of local materials, and passive energy systems. Particularly for hot-arid regions, passive cooling strategies such as natural ventilation, solar protection, thermal mass, and evaporative cooling demonstrate the potential to achieve occupant comfort while minimizing energy consumption. Hassan Fathy’s assertion that "to build means to cooperate with earth and nature, to know the laws and obey them" (Fathy, 1973) underscores the relevance of these time-tested principles. This paper explores how vernacular principles can be refined to meet the rigorous demands of modern net-zero carbon targets, focusing on hot-arid climates as a starting point.

Theresearchisexpectedtodemonstratehowpassivecooling principles from vernacular architecture can enhance thermal comfort and reduce energy use in modern net-zero carbon buildings in hot-arid regions. It will provide practical recommendations tailored to local climatic and cultural contexts,emphasizingtheimportanceofongoingadaptation and evaluation. These findings will offer actionable insights for architects and policymakers, bridging traditional knowledge with contemporary sustainability frameworks. As (Stewart Brand, 1994) remarked, “Every building is a prediction; every prediction is incorrect,” underscoring the iterative nature of this endeavor.

The study aims to investigate how passive cooling strategies from vernacular architecture particularly those suited to hot-arid regions can be adapted for modern net-zero carbon buildings. It will examine strategies such as natural ventilation, thermal mass, and solar protection, ensuring compatibility with contemporary sociocultural contexts while promoting occupant wellbeing and long-term sustainability.

A focused literature review will identify and evaluate key vernacular cooling strategies in hot-arid regions. Comparative case studies will analyze historical vernacular buildings and contemporary structures employing similar principles. In-depth interviews with architects and sustainable design experts will provide qualitative insights into the application of these strategies. Post-occupancy evaluations (POE) will be reconsidered due to access limitations, with an emphasis instead on documented performance data and user feedback from existing studies.

In hot-arid regions, architectural design must balance environmental sustainability with human comfort while respectingculturalandsocialcontexts.AsHassanFathy(1986) articulated in Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture, passive cooling strategies such as natural ventilation, thermal mass, solar protection, evaporative cooling, and vegetation management areessentialindevelopingsustainablesolutions for these climates. These strategies, rooted in centuries of traditional practices, demonstrate the ingenuity of vernacular architecture while offering lessons for modern adaptations. Comparing these strategies in both vernacular and modern contexts reveals valuable insights into their efficiency, sustainability, and cultural relevance, paving the way for innovative approaches to climate-responsive design.

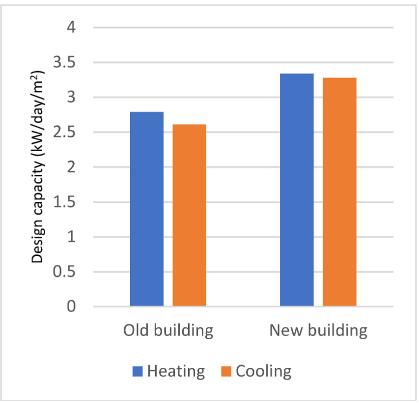

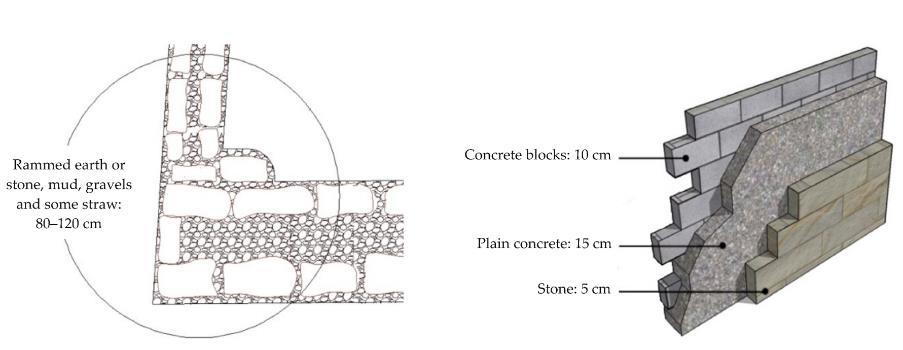

Traditional architecture in hot-arid regions often employs materials like stone, mud, and adobe, which possess low thermal conductivity and high thermal mass. As Asquith and Vellinga (2006)noted,thesematerialsnot onlyregulateindoor temperatures effectively but also embody sustainability by utilizing locally available resources. In contrast, modern materialssuchasconcreteandsteeldominatecontemporary construction but often lack thermal insulation, leading to higher energy demands for heating and cooling. According to Younes et al. (2012), integrating natural materials into modern design can significantly reduce operational energy and mitigate the environmental impact of construction.

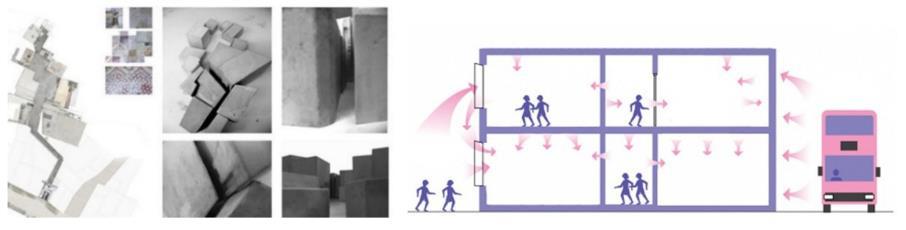

Thick walls, a hallmark of vernacular buildings, act as thermal reservoirs by delaying heat penetration during the day and releasing it at night. This concept of thermal lag enhances comfort by minimizing temperature fluctuations. Abdel Hadi (2006) explained that these walls provide a "natural buffer" against extreme weather, a feature absent in many modern designs with thin, poorly insulated walls.

4: Comparison of the overall expenses of a new and old building in Palestine

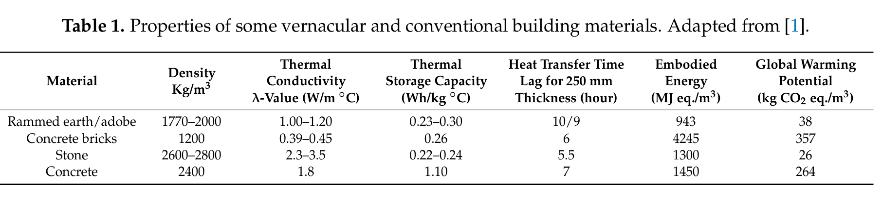

5: A comparison of a modern and old building's design capacities in Palestine.

Modern architecture can benefit from lessons in material selection. Fernandes et al. (2010) recommend using advanced sustainable materials such as phase-change materials, which mimic the thermal storage capacity of traditional materials while catering to contemporary construction needs. For example, rammed earth and hollow bricks serve as environmentally friendly alternatives, combining traditional wisdom with modern innovations.

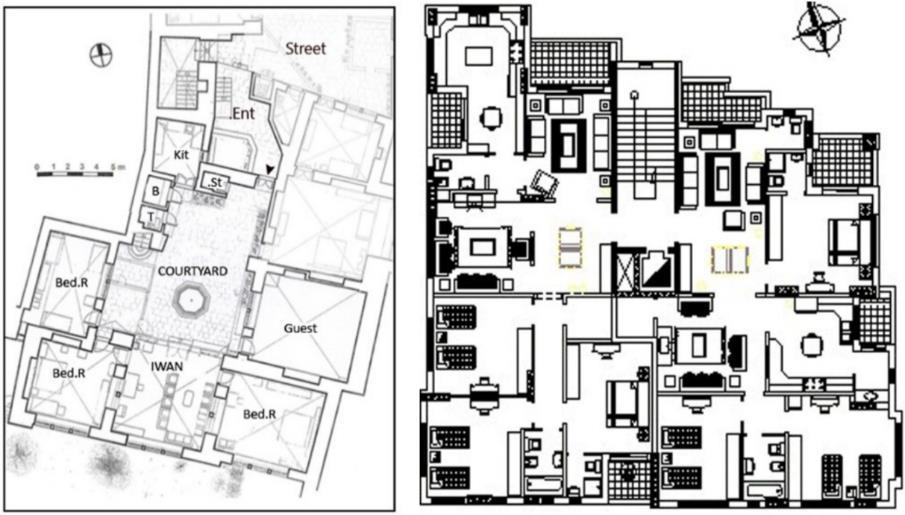

Courtyards have historically played a vital role in vernacular architecture, serving as microclimatic regulators. Edwards (2001) observed that these open spaces enhance airflow, reduce heat buildup, and provide shaded areas, thereby reducing dependency on mechanical cooling systems. In contemporary designs, the absence of such features often results in increased energy consumption.

Windows in traditional buildings were strategically placed to optimize natural ventilation and solar control. Smaller openings were often oriented to face prevailing winds, enhancing cross-ventilation. Al-Masri and Abu Hijleh (2012) highlighted that these principles are frequently overlooked in modern designs, where aesthetics often take precedence over climate compatibility, leading to inefficient energy use.

7: Comparing the opening levels, there are many building openings to the outside spaces on the New (Right) side and few on the Old (Left) side.

The Mashrabiya, a lattice screen typical of Islamic architecture, balances privacy, airflow, and solar protection. Bianca (2000) notedthat these intricate designs not only serve functional purposes but also add aesthetic value. Modern adaptations of Mashrabiya, such as perforated façades or movable louvers, provide energy efficiency while maintaining cultural significance.

8: Comparing the openings' levels, shading, and privacy features as the "Mashrabiya," Old (Left); and the New (Right), which are not shaded.

Shading elements, such as overhangs and pergolas, are integral components of traditional architecture. Fathy (1986) explained that these features minimize solar radiation, particularly during the summer months, while allowing lowangle sunlight in winter. The strategic orientation of buildings also contributes to efficient solar protection.

Advanced shading solutions, such as dynamic façades and kinetic systems, have emerged in contemporary architecture. Olgyay (1963), in Design with Climate, emphasized that these systems build upon traditional shading principles by integrating automation and sustainable materials. Reflective surfaces and cool roof technologies are modern extensions of vernacular techniques, enhancing solar deflection and energy efficiency.

Figure 9: Comparatively speaking, the Old (Left) uses "Kizan" for cooling and privacy at the level of the apertures, whereas the New (Right) uses outdoor spaces such balconies that lack visual privacy.

Incorporating culturally significant elements, such as kizan (perforated pottery screens), fosters user acceptance and environmental harmony. Taleghani et al. (2014) highlighted the importance of maintaining cultural identity in modern designs, ensuring sustainability aligns with local traditions.

Thick walls in traditional Nablus buildings act as thermal buffers, stabilizing indoor temperatures. Ragette (2003) explained that these walls absorb heat during the day and release it at night, ensuring a stable indoor environment even in extreme climates.

Figure 10: Comparing the opening levels, the major apertures on the left are facing the interior courtyard, while the openings on the right are facing all directions.

Night flushingcomplementsthermalmass bycoolingbuildings during the cooler evening hours. Meir et al. (2009) described how cross-ventilation and high-level operable windows enhance this process, a concept that modern designs can readily adopt.

Contemporary Challenges and Opportunities

Integrating thermal mass into high-rise buildings presents challenges such as limited space and urban density. Zhang et al. (2014) proposed innovative solutions, including façadeintegrated thermal systems and composite materials, to address these issues while maintaining energy efficiency.

11: Comparison between the Old (Left) and New (Right) internal spaces

Water features such as fountains and water channels are prominent in vernacular architecture. Edwards and Sibley (2001) explained that these elements leverage evaporative cooling to create more comfortable microclimates, particularly in courtyards.

Indirect evaporative coolers offer a contemporary alternative, providing cooling without increasing humidity. Santamouris (2006) suggested that integrating these systems with renewable energy sources, such as solar panels, can reduce operational costs and environmental impact.

Incorporating greenery and water features into public and private spaces reflects the harmony of traditional designs. Fathy (1986) noted that such elements not only address climate challenges but also enhance community well-being and aesthetic appeal.

all directions.

TreesandclimbingplantsaroundcourtyardsinNablusprovide natural shading and cooling. Ragette (2003) emphasized the role of seasonal foliage changes in optimizing energy efficiency, such as shedding leaves in winter to allow passive heating.

Taleghani et al. (2014) argue that urban heat islands necessitate the adoption of green solutions like vertical gardens andgreen roofs.These features replicatethebenefits of vernacular landscaping in densely populated urban settings.

Vegetation offers a low-cost, low-maintenance alternative to mechanical cooling systems. Santamouris (2006) explained that integrating greenery into urban planning enhances thermal comfort and reduces energy consumption.

Figure 14: In terms of vegetation, the Old (Left) uses vegetation in the courtyards, whereas the New (Right) lacks greenery at the building and urban sizes.

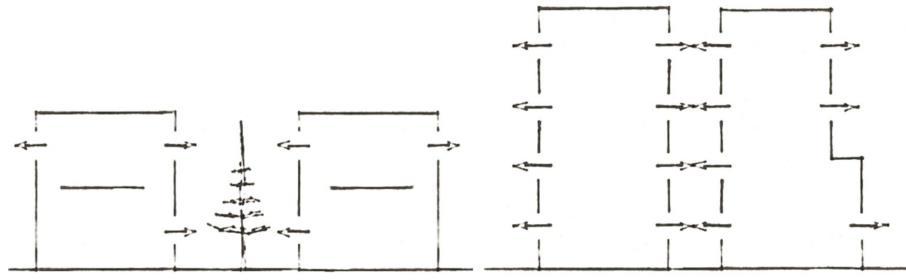

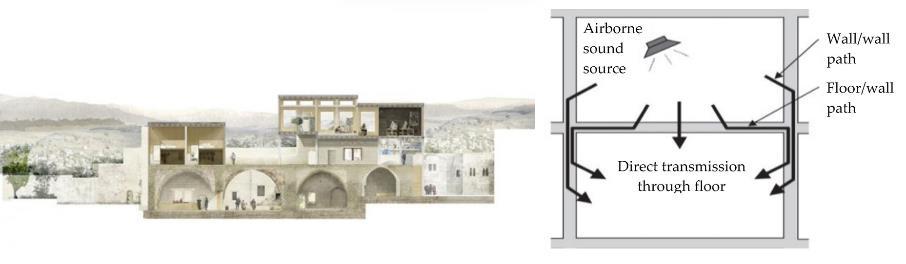

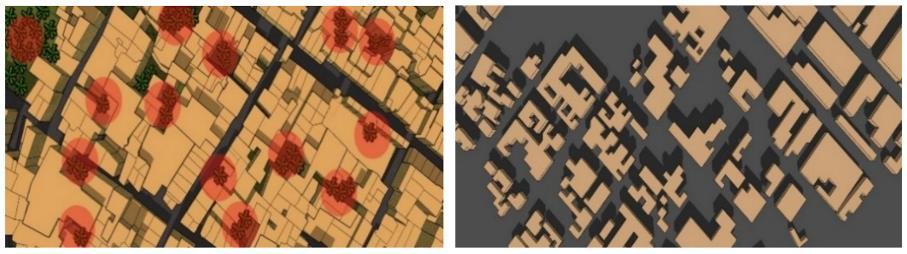

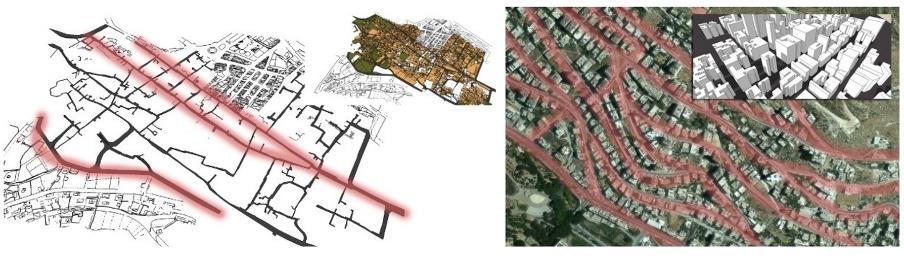

Traditional layouts, featuring narrow streets and low-rise clustered buildings, inherently reduce noise transmission. AlMasri and Abu Hijleh (2012) noted that thick walls and courtyards further isolate living spaces from external disturbances.

Figure 15: Comparing the Old (Left) and New (Right) in terms of internal noise transmission, the former has low noise transmission via low-rise buildings and the latter has strong vertical noise

Modern urban layouts often exacerbate noise pollution. Meir et al. (2009) argued that incorporating green buffers and semi-courtyards can help mitigate these issues, improving the livability of urban environments.

Using noise-insulating materials and drawing lessons from vernacularplanning,assuggestedbySantamouris(2006),can create quieter, more comfortable cities.

Figure 16: Comparing the Old (Left) and New (Right) for internal noise transmission, the former uses courtyards as a "cavity" to inhibit horizontal noise transmission, while the latter uses open streets and divided buildings to increase noise from outside buildings.

Figure 17: Comparing the various types of streets at the level of outdoor noise transmission, the Old (Left) allowed for a drop in noise transmission, while the New (Right) allowed for an increase in noise transmission due to public and unclassified roadways.

Figure 18: In terms of exterior noise transmission, pedestrian walkways devoid of cars also reduced outside noise, Old (Left); permitting cars to utilize all roadways increased outside noise, New (Right).

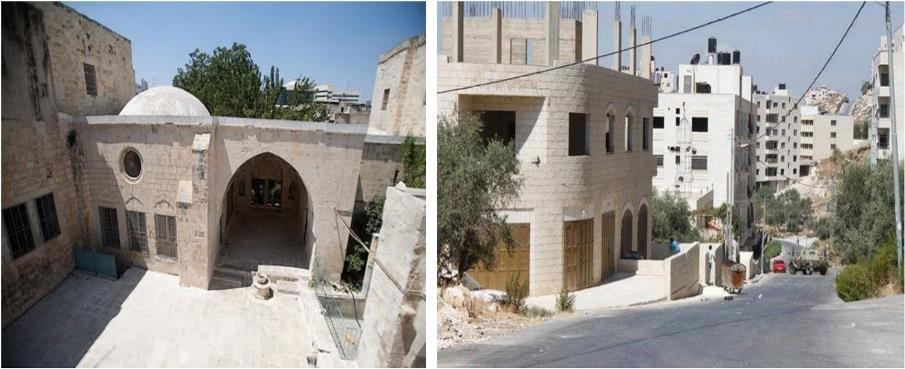

Vernacular buildings in Nablus emphasize modesty and social equality.Fathy (1986)highlightedhowthesefeaturespromote community identity and cohesion.

Modern architecture often reflects socioeconomic disparities, with visible differences in building size, materials, and design. Bianca (2000) called for policies and designs that prioritize inclusivity and social harmony.

Edwards (2001) suggested that the modest aesthetics of vernacular architecture can inspire sustainable urban development, blending functionality with cultural relevance.

Figure 19: At the building picture level, the economic status of the occupants was only represented by the interior space quality, Old (Left); the working and lower middle classes reside in multiresidential buildings, New (Right).

Design strategies for hot-arid regions, particularly those rooted in vernacular architecture, offer profound insights into achieving thermal comfort and sustainability. As Fathy (1986) observed, elements such as natural ventilation, thermal mass, solar shading, evaporative cooling, and vegetation demonstrate the ingenuity of traditional designs. Modern architecture can draw from these principles, adapting them with innovative materials and technologies to create resilient structures that meet the challenges of climate change.

Figure 20: At the building image level, buildings have a similar and straightforward exterior appearance (Old (Left); the image and height of the building represent the residents' financial status, and detached homes are typically occupied by upper-middle-class and upper-class people (New (Right)).

In the old city of Nablus, building materials were sourced locally and were primarily natural, such as mud, stone, and earth.These materials had significant thermal mass properties, meaning they could store heat during the day and release it at night, helping to moderate indoor temperatures in extreme climates. Additionally, the thick walls of these buildings provided insulation from noise, creating a quieter, more comfortable living environment. As noted by Asquith and Vellinga (2006), the use of these materials contributed to the buildings' sustainability, both in terms of energy efficiency and minimal environmental impact, as they did not require extensive processing or transportation.

Thedesignofinteriorspacesintraditionalhousesintheoldcity of Nablus was heavily influenced by cultural values such as privacy, modesty, and hospitality. These values dictated the spatial organization of the home, ensuring that the design provided intimate spaces for family life while offering privacy from outsiders. Courtyards played a crucial role in this setup, serving as an extension of the interior, providing light, air, and a place for social gatherings. According to Fathy (1986), such courtyards helped in regulating the temperature inside the house, making them a sustainable element of traditional architecture.

Modern houses, on the other hand, tend to prioritize economic factors over cultural considerations. As a result, many new apartment designs lack these cultural features, as they are more focused on maximizing floor space and reducing construction costs. This can lead to a disconnection between the built environment and the cultural or social needs of the residents. The lack of courtyards or adequate ventilation can make the indoor environment uncomfortable and less energy-efficient, further exacerbating the challenges of living in a hot-arid climate.

Openings in traditional architecture, such as windows and doors, were designed with a careful understanding of the local climate. The placement, size, and orientation of these openings were optimized for passive cooling strategies, allowingcool breezestoenter while minimizingheat gain from the sun. In many vernacular buildings, windows were located to capture the prevailing winds during the summer months, while in winter, they were positioned to let in the warm sun, providingnatural heating.As notedbyAl-MasriandAbu Hijleh (2012), these carefully placed openings not only contributed to thermal comfort but also helped to preserve privacy, as they were often screened by latticework or curtains.

In modern buildings, however, this consideration is often overlooked. The aesthetic appeal of large windows and open-plan designs often takes precedence, disregarding the importance of orientation and the effects of direct sunlight. This can lead to increased reliance on mechanical cooling systems and a significant loss of energy efficiency. As Fernandes et al. (2010) observed, modern buildings are frequently designed without an understanding of the surrounding environmental context, which compromises both thermal comfort and privacy.

The role of vegetation in traditional architecture was vital, not only for aesthetic reasons but also for its functional contribution to the environment. In the old city of Nablus, vegetation such as trees, vines, and shrubs was used strategicallyaroundcourtyardstoprovideshadeandcoolthe air through evapotranspiration. These natural elements helped reduce the temperature in the surrounding area, particularly in the hot summer months. Fathy (1986) highlighted the importance of integrating nature into urban planning, arguing that plants and trees have a cooling effect that can make the built environment more livable without the need for excessive mechanical cooling.

However, in modern developments, the use of vegetation is often minimal, especially in urban areas where space is limited, and green spaces are not prioritized. The shift towards high-risebuildingsanddenseurbanareashasresultedinfewer opportunities for planting trees or creating green spaces. As a result, the new urban areas suffer from higher temperatures and poorer air quality, contributing to the urban heat island effect. Taleghani et al. (2014) stress that integrating green spaces, such as vertical gardens or rooftop gardens, into modern urban planning could help mitigate these issues and improve environmental sustainability.

The image of a building in the old city of Nablus was largely dictated by cultural norms and the societal value placed on modesty. As Fathy (1986) explained, traditional architecture emphasized simplicity and uniformity, with buildings sharing similar exterior features regardless of the wealth of the owner. This uniformity helped promote social cohesion, reducing the visual disparity between rich and poor, which in turn fostered a sense of equality and shared identity. This design approach was in direct response to the cultural need for modesty and the avoidance of ostentation.

In contrast, modern buildings in Palestinian cities often reflect the financial status of the owner, with luxury apartments and mansions featuring distinct, ostentatious exteriors. The exterior image of abuilding in new urban areas has become asymbol ofwealthandindividualstatus,leadingtoamorefragmented urbanfabric.Bianca (2000)critiquedthistrend,notingthatthe emphasis on individual expression through building facades oftenunderminesthesocialunitythatwaspresentintheolder, more modest architectural styles.

Noise transmission in the old city of Nablus was minimized through the strategic placement of residential units, narrow streets, and the use of thick walls, which acted as sound barriers. The "Housh," or private courtyard, provided a buffer between homes and the outside world, preventing noise from external activities fromenteringthe livingspaces.Al-Masriand Abu Hijleh (2012) highlighted the importance of these spatial arrangements in creating a quiet, peaceful environment within the city.

In modern urban areas, however, noise pollution is a growing issue. The grid system used in contemporary city planning often places residential buildings next to busy roads, leading to higher levels of noise exposure. The lack of adequate noiseinsulating materials in contemporary buildings further exacerbates this problem. Meir et al. (2009) noted that the absence of green buffers and the reliance on concrete facades make it difficult to achieve acceptable noise levels within the home. Incorporating features such as doubleglazed windows, soundproof walls, and green spaces could help reduce noise transmission and improve the livability of modern urban areas.

References

• Abdel Hadi, A. (2006). Sustainable Building Design for HotArid Climates. Springer, Berlin.

• Al-Masri, N. and Abu Hijleh, B. (2012). ‘Courtyard housing in mid-rise buildings: An environmental assessment in hot-arid climates,’ Energy and Buildings, 55, pp. 481-493.

• Al Tawayha, F., Braganca, L. & Mateus, R., 2019. Contribution of the Vernacular Architecture to Sustainability: A Comparative Study between the Contemporary Areas and the Old Quarter of a Mediterranean City. CTAC Research Centre, University of Minho.

• Asquith, L. and Vellinga, M. (2006). Vernacular Architecture in the Twenty-First Century: Theory, Education, and Practice. Taylor & Francis, Abingdon.

• Bianca, S. (2000). Urban Form in the Arab World: Past and Present. Thames & Hudson, London.

• Brand, S. (1994). How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built. London Penguin Books.

• Edwards, B. (2001). Green Architecture: Principles and Practice. Architectural Press, Oxford.

• Edwards, B. and Sibley, M. (2001). Sustainable Architecture: European Directives and Building Design. Routledge, London.

• Fathy, H. (1973). Architecture for the Poor. University of Chicago Press.

• Fathy, H. (1986). Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture: Principles and Examples with Reference to Hot-Arid Climates. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

• Fernandes, E. et al. (2010). ‘Phase change materials for thermal energy storage: Design, applications and

performance,’ Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 14(3), pp. 1095-1110.

• Meir, I.A., Garb, Y., Jiao, D. and Cicelsky, A. (2009). ‘Postoccupancy evaluation: An inevitable step toward sustainability,’ Advances in Building Energy Research, 3(1), pp. 189-219.

• Olgyay, V. (1963). Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

• Ragette, F. (2003). Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region. American University of Sharjah Press, Sharjah.

• Santamouris, M. (2006). Environmental Design of Urban Buildings: An Integrated Approach. Earthscan, London.

• Taleghani, M., Tenpierik, M., Kurvers, S. and van den Dobbelsteen, A. (2014). ‘A review into thermal comfort in buildings,’ Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 26, pp. 201-215.

• Younes, C., Shdid, C.A. and Bitsuamlak, G. (2012). ‘Air infiltration through building envelopes: A review,’ Journal of Building Physics, 35(3), pp. 267-302.

• Zhang, Y., et al. (2014). ‘High-rise buildings and thermal mass: Optimizing energy performance,’ Energy and Buildings, 77, pp. 143-152.