3 minute read

McDonaldization of Language Learning | Anna Drewing

What does a fast-food chain have to do with the study of foreign languages? Possibly just as much as it has to do with society in general. McDonaldization is a term coined by a sociologist George Ritzer in 1993 to describe a situation in which a society adopts the characteristics of a fast-food restaurant. There are four aspects of this process. Firstly, an essential feature of McDonaldization is the efficiency – all the efforts are put into the minimisation of production time. Then, there are predictability and control, and finally, there is calculability – the objectives should be quantifiable.

On the example of the McDonald’s brand itself, the efficiency is to be found in the way the food is being prepared - on an assembly line, just like in a car factory. Calculability is reflected in the fact that the sales are more important than subjective gustatory pleasures. For instance, it’s insignificant what the BigMac’s taste is, as long as people keep buying it in large quantities. The predictability factor manifests itself in the form of a worldwide standardisation of services. Control is just another word to say that the workers are supposed to toe the line, or they will be replaced. In short: do your job and don’t think outside the box.

Advertisement

Still, it is a big leap from fast-food to languages, one may think. And yet, since languages are so crucial nowadays, probably more than ever, it is no surprise that somebody already came up with an idea to monetise it. For the past several years, creative and innovative offers of language courses have sprung up like mushrooms. What do they have to do with McDonaldization? Everything!

Efficiency: they offer maximal development of your language skills for the minimal amount of time you need to sacrifice in order to achieve that goal. “Study only 15 minutes every day!”; “Become proficient in 3 months!” – does that ring any bell?

Calculability: many online courses are based on the idea of gamification, i.e. while learning, you earn points, get to a higher level, and collect badges. Interestingly, such courses rarely reward real-life aspects. For example: can you follow a simple dialogue in your target language? Do you understand longer texts? How well can you use the language in a mundane, everyday situation?

Predictability: have you noticed that all the courses on Duolingo-like platforms have almost identical structure? That all the lessons are the same, even though they cover completely different topics? The study is repetitive and easy, and just a tiny bit challenging – enough to make you feel that you are learning something, but not enough to pose a serious problem that you might encounter in a real communication situation.

Control: why would you need a teacher, who is creative and motivating, but sometimes sad or tired – so, ultimately: imperfect and flawed – when you can have a fully automated online experience? After all, the machine will never surprise you with an unannounced quiz or make you present a speech in front of the entire class.

How tragically unchallenging.

Many language learning apps or pre-made courses are desperate to keep the students in their comfort zone. Everything is nice, pretty, and instantly rewarding. That is, until you realise that the actual language learning magic happens outside the comfort zone, not inside it.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not trying to bash language learning apps in general – they offer a nice play-start into the process of learning a new language. Are you thinking of taking up Russian, but you are not yet sure whether it is something for you? Then try Duolingo for a few weeks before you decide to find a teacher; it will give you a pleasant first feel of the language.

However, what you should always keep in mind is that your ultimate language learning goal is to go way beyond games like that. It is to start talking to people, reading the news, listening to foreign radio channels. While at the same time, the ultimate goal of apps like Duolingo is to keep you playing in the kids’ pool.

So in the end, if you are truly serious about learning a foreign language, just remember that at one point you need to get off the beaten track. After all, it is an incredibly personal experience, in which you will want to find way more variety and brain nutrition than a language-course-equivalent of a BigMac.

Anna Drewing

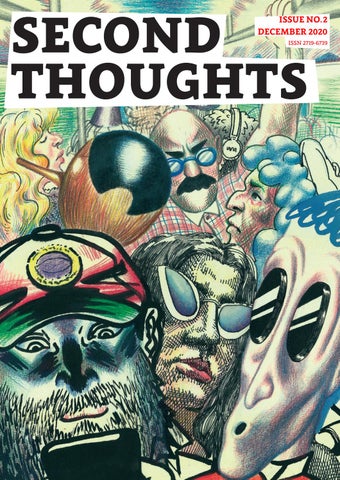

Cover illustration: Zofia Klamka & Karol Mularczyk