5 minute read

Belarus Remembering How to Breathe | Natallia Valadzko

The text was written in mid-August 2020.

We are several months into the new order around the world – the devastating death toll and lockdown consequences, the results of the pandemic. It may not be well-known but the Republic of Belarus is the only country in Europe that did not introduce a strict lockdown. While many countries were declaring “war” on coronavirus, Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko persuaded that COVID-19 resides “only in the heads” of the people and that “hysteria” around it is exaggerated.

Advertisement

As far as Belarus is concerned, despite certain safety precautions in place, it certainly did not feel like the prototypical domain of war, maybe except for its victims. The local discourse of COVID-19 is an exceptionally complex and odd phenomenon; especially due to the fact that the president, with overwhelming executive power, shaped the discourse to his will, which had real-life implications on how unconsciously citizens chose or were forced to behave.

The everyday language used to describe the pandemic may be evidence for how people conceptualize the virus and the strategies of dealing with it. Speeches of many countries’ representatives evoked images of global conflict with the forces of a “deadly enemy” and heroes fighting for the safety and the future of the public “on the front lines”. While the war-like emergency perspective calls for swift collaboration and driven action, one may also talk of “casualties”, “victims”, and “collateral damage”.

The danger is that war language shallows a very complex situation and may cause panic stocking. Moreover, war-waging has intensified racism, sexism, and xenophobia before, and, in this case, it again tends to prioritize national interests. The war framing does not seem to protect the minorities. As the example of the US shows, brown and black communities suffered increasingly more from the coronavirus outbreak. In the pro-active, swift actions aimed at triumphing over the enemy by highlighting the opponent, we dramatically neglect human lives and communities, who become the said casualties and collateral damage.

In his speeches, Lukashenko was calling the virus a global “psychosis” and claiming that “vodka, fresh air and hockey, tractors in the countryside will cure it all.” This active encouragement to “not be suffocated by face masks” and keeping healthy by “exercising or working in the field in the open air” could be frequently heard in the media. Keeping quite regular violations of constitutional rights in mind, it is slightly amusing to witness how Lukashenko did not want to put Belarusians “into cages”, pointing to the freedom provided, in contrast to limitations and regulations introduced by the rest of the world.

The very first deaths from the virus were not framed as war casualties, but as people who are themselves fully responsible for their deaths by “foolishly deciding to go outside”. For instance, commenting on the death of a famous Belarusian actor, Lukashenko claimed that nobody should be too surprised since “what a 75-year-old man is doing outside?” and, besides, he was already “weak and had a bunch of health problems”. The denial of the existence of the coronavirus or the underestimation of its lethality was ever-present. People were said to die from conditions associated with smoking or being overweight, almost arranging people in a hierarchy of who deserves and does not deserve to be affected by the coronavirus. People in critical condition were blamed for “giving up the fight” and “forgetting how to breathe”, and it was said that “we have to teach them how to breathe again” when using ventilators, which sounds like a mockery of human dignity and varying degrees of immunity.

It is possible to compare the virus reception to a mental health problem that has been met with stigma. One might say that it has been framed as something to be ashamed of, something to hide – which was actually attempted – or grossly underrepresented and downplayed. By abusing human's appreciation of personal freedom, deaths were blamed on the victims and maintaining the normalcy was encouraged. Stigma has often to do with taboo, silence, gaslighting, and victim-blaming. We know that stigma kills, and so it did.

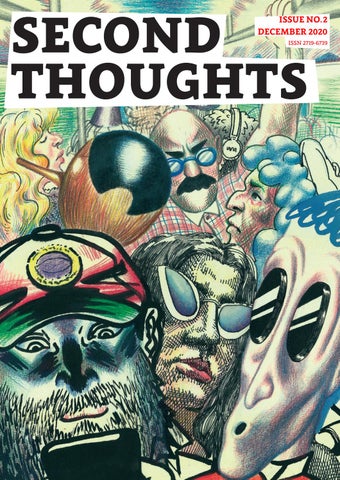

Zofia Klamka & Karol Mularczyk

On the other hand, while the government’s official approach was that of passivity and denial, not everyone agreed to let things go off. While it was hard to talk about established opposition in Belarus due to a precarious, and outward dangerous, position it put anyone who tried to voice their different opinion, Belarusian citizens were used to relying on themselves. Since the outbreak, a great number of volunteers were donating money to help medical professionals with safety equipment, bringing lunches to hospitals and making thousands of protective face masks for the general population pro bono. If we were sticking to the war domain of COVID-19 in Belarus, then the Belarusians were showing consolidated effort, cooperation, and overwhelming care in the face of the enemy – the virus and the state’s inaction.

Despite questionably ambiguous reports of the number of daily cases in Belarus, on July 2nd Lukashenko declared that “we have won the battle against coronavirus”. It seems eerily similar to his general attitude on the result of World War II, that is, downplaying the horrifying devastation and trauma, and foregrounding the “victorious might” and its celebration. The question of what exactly one can call a victory while considering the price paid is all too relevant. It is beyond ironic that right before very challenging presidential elections in August, Lukashenko became a victim of what he himself called, just a couple months before, psychosis. He had to postpone his public appearances a few times, but even though he recognized COVID-19 by admitting that he, in fact, was sick, he was still consistent in highlighting that he went through it while being “on his feet”. This type of rhetoric further flashes out the shameful stigma around the pandemic. In other words, weakness is not allowed.

August 9th was the day of the long-awaited presidential elections that were not like any other in the past 20 years. One might only speculate about the casualties of the people’s war against COVID-19, as there is no transparency about the extent of the spread of the virus. Lukashenko started a war against his own folk through gross voter fraud and, afterwards, brutal suppression of peaceful protests. The discourse around the 2020 elections in Belarus does not need much to use the metaphor of war. Well-equipped and trained units, the use of gas, rubber bullets, vicious beating and torture seemed quite literal.

Natallia Valadzko

Cover illustration: Zofia Klamka & Karol Mularczyk