6 minute read

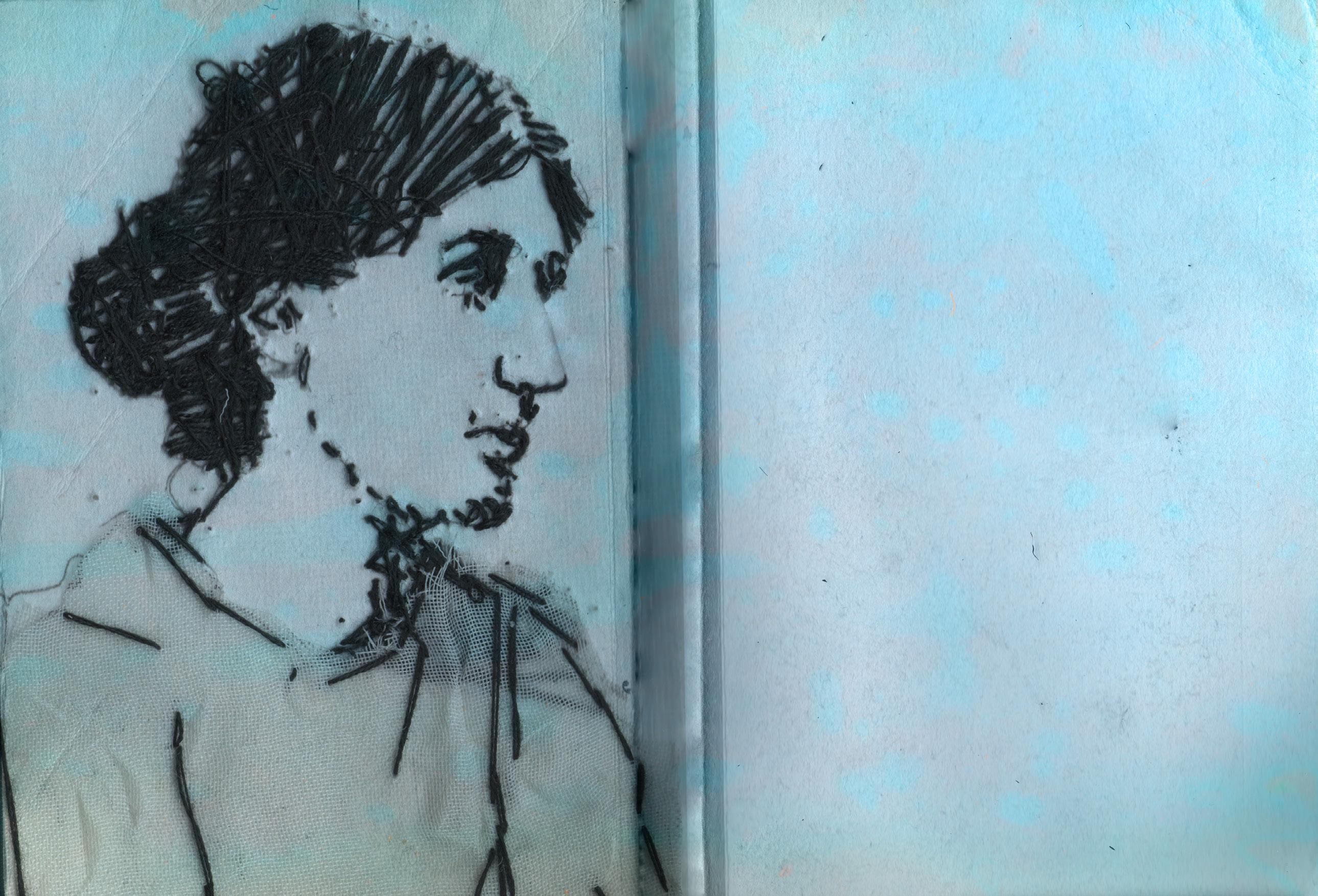

Why Read Virginia Woolf in 2020 | Anna Potoczny

It took several decades following her death for Virginia Woolf to be rediscovered. Immensely popular throughout her life, she was temporarily forgotten after the turmoil of the Second World War. After all, what could a delicate upper-class authoress, apparently too fragile to bear the harsh social and political reality of the 40s, tell us about the contemporary world?

Of course, it can hardly be an accurate description of Virginia Woolf (except for the “upper-class” part). Such a perception of her may have been caused, according to Woolf’s biographer Hermione Lee, by a report written after her suicide in 1941. According to the report, the writer took her own life, as “a balance of her mind was disturbed” due to the threatening political situation. The text was controversial with Woolf’s friends and family, as it completely disregarded the actual reason of her death – her conviction that she was “going mad again” with no chance for recovery this time. It is now generally known that Woolf suffered from a debilitating mental illness (probably bipolar disorder) for over forty years.

Advertisement

Woolf’s writing can be considered revolutionary in a variety of ways, which was only noticed in the 1950s, once the writer herself was given a voice. The publication of her diaries, letters, and a biography resulted in a renewed interest not only in her works but also in herself. As a non-heteronormative, feminist, mentally ill writer, she has been eagerly read through such a lens, and her texts have often been explored by feminist, queer, and ecological literary critics.

None of those aspects of her writing is exactly surprising now – to some, they are even uninteresting. Rather, I would argue that the unique power of Woolf’s works lies in the author’s compelling and incredibly personal way of writing about people and the world at large. Her characters’ constant striving to get closer to life itself, to bridge the gap between themselves and other individuals, in order to represent timeless values and issues.

More than half a century after Woolf’s death, we dwell in a completely different reality. We are flooded with information and (usually upsetting) news, which may lead us to grow distrustful of each other. The Western world has become varied, welcoming a range of world-views and identities. While theoretically more inclusive, this world has at the same time become more divisive. The idealisation of individualism might have caused us to insist on looking inwards. As Olga Tokarczuk noted in her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “[w]e live in a reality of polyphonic first-person narratives, and we are met from all sides with polyphonic noise”. In dealing with the world, we consult our own preconceptions about people and things when we should perhaps be looking outwards, towards people radically different from us, and see what they have to offer. Virginia Woolf started writing a bit over a century ago. Her times were perhaps equally turbulent and full of changes as ours, calling for new forms of writing. Did she possibly show us an alternative way of expressing ourselves and engaging with others – a way that questions our tendency towards self-centredness?

Zofia Klamka & Karol Mularczyk

In her diary entry from 1920, Woolf reflects on her friendship with Katherine Mansfield who claimed, when discussing their relationship, that “one ought to merge into things”, to almost become one with the object of affection. The idea of “intermittently merging”, as Hermione Lee phrases it, appears throughout her works. It makes one consider that perhaps our identity may be based as much on introspection and a sense of individuality as on our relations with others.

The motif of complex relationships, of gathering and collecting – people, mostly – constitutes a well-known Woolfian theme, illustrated by party scenes in novels such as Mrs Dalloway or To the Lighthouse. The free flow of thoughts released from the mind of each character strengthens the sense of individuality and self-exploration, but it also suggests the need for a connection which would blur the boundaries between individuals. One’s self stops being dependent on social class or status, and human connection is not grounded in common life experience, similar views, or any other such kind of similarity anymore. When space (domestic or urban) becomes the only thing that connects random strangers, surprising associations are made.

In Mrs Dalloway, Septimus Warren Smith, a shell-shocked former soldier and poet, who commits suicide to avoid forced hospitalisation, serves as a double to Clarissa Dalloway, an upper-class hostess of a lavish party in Westminster. “She felt now somehow very like him – the young man who had killed himself”. This striking instance of the possibility of seeing your own self in someone completely different is one of the most astonishing fragments of the book. Shocked into awareness by death that could have been her own, Clarissa Dalloway feels compelled to escape for a moment from the bottomless pit of stimuli that is her party and “assemble”, and to reunite with her childhood friends, who have been there all the time, although much changed.

While the emphasis on looking inwards is particularly characteristic for Woolf’s prose, perhaps the most powerful moments are those when she writes about looking outwards – towards others, towards the world, from which we are never fully separate. Total individuality and independence are only true to some extent, as the borders of our identity are never stable enough to remain intact in the face of meaningful human contact. While Woolf writes compellingly about individuality and never fails to be brilliantly introspective, she also clearly touches upon the topic of the pain of isolation, of the persistent desire to know other people and to be closer to them.

What Woolf criticised was the egocentrism that appears when people base their sense of self on someone else’s alleged inferiority. She exposes such egocentrism through the character of Charles Tansley in To the Lighthouse. He is an ambitious, yet clearly insecure young academic. Daydreaming about academic titles that would make others admire him, he still feels the need to strengthen his sense of superiority by claiming, at the sight of a woman with an easel, that “[w]omen can’t paint, women can’t write”. Painfully self-absorbed, slightly obsessed with the concept of his own greatness, he wishes to impress a woman he admires. However, she finds his self-centred attitude quite insufferable. The novel questions the idea of life as a set of milestones and achievements. The memories of departed friends, cultivated by those who remember them, are all that is left in the end. In To the Lighthouse, people achieve immortality not through their individual greatness, but through everyone else’s effort to keep them alive through memories.

Why, then, is it worth reading Virginia Woolf in 2020? Perhaps for comfort. Perhaps to let ourselves be convinced that other people are also a source of comfort. Woolf’s novels offer a touching and refreshing perspective on human relationships and the place of the self within those relationships. She often explores the difficulty of truly knowing other people without being led astray by our own projections. Woolf’s works offer us the idea that, although it really is difficult to look beyond ourselves and reach out to people radically different from us, we should probably try. Emotional intimacy can be found in the most surprising moments and places – between a young, awkward painter and an upper-class homemaker, a sophisticated socialite and a suicidal veteran, or within a long-neglected friendship. Closeness, as illustrated by Woolf, can reside everywhere, as its basis is not any superficial sort of similarity but our shared, vulnerable humanity.

Anna Potoczny

Cover illustration: Zofia Klamka & Karol Mularczyk