HANDS ON

P.4 Preface P.12 Uta Graff (Peer): Heritage and Creation of Knowledge. P.20 Christoffer Harlang: Hammershus Revisited – Reflections on Strategies for a Contemporary Building Culture. P.30 Nicolai Bo Andersen: Sustainable Aesthetics – An Outline of a True Sustainable Building Culture. P.36 Nicolai Bo Andersen & Victor Boye Julebæk: Joint Matter – An Annotated Visual Essay on Sustainable Timber Construction. P.48 Søren Vadstrup: Hurl Space – The Intangible Heritage of the Timber-Framed Farmhouse. P.62 Thomas Kampmann: Revitalising Building Archaeology

– Coupling Traditional Building Archaeology, Surveying and LCA. P.74 Morten Birk Jørgensen: Crowning Svaneke – The Water Tower by Jørn Utzon. P.86 Søren Bak-Andersen: All-Wood-No-Nails – Robotic Tooling Utilising

Historical Material Knowledge. P.98 Victor Boye Julebæk: Tacit Matter – On the Surface of Things. P.110 Back Matter. P.112 Authors’ Biographies.

Morten Birk Jørgensen, Victor Boye Julebæk and Christoffer Harlang. In 2018, we – the researchers at TRANSFORMATION – issued the publication ROBUST in connection with a conference of the same name. The conference was held in Danish for a local professional crowd and the publication written in English for non-Danish speakers. This format proved fruitful as a way to collect excerpts from the research and share them with colleagues and peers within the fields of architecture and cultural heritage. The publication at hand is a sequel to ROBUST, with the modifications we find worthwhile and with a content reflecting our latest research. When we decided to follow up in a similar format, we soon settled on the working title HANDS ON. More out of intuition than

as a product of a particular thematic intention. This ambiguous phrase clung to the work, however, and was eventually elevated to the actual title of the publication. So, what made this title so catchy that we couldn’t wrench it off as the work evolved? Let us take a brief look at the etymology of the phrase and see what is revealed.

The American dictionary Merriam-Webster has an entry under ‘hands-on’ – with a hyphen, that is. According to this, ‘hands-on’ has two main meanings. The first being ‘relating to, being, or providing direct practical experience in the operation or functioning of something.’ Interpreting this in relation to the publication, several of the articles really do present ‘direct practical experience’ concerning their topic. As for the other meaning: ‘characterized by active personal involvement,’ we can vouch for this being a distinguishing feature of all the contributions.

In our version – without the hyphen – the phrase also relates closely to another entry at Merriam-Webster, namely ‘hand on’. This is synonymous with ‘hand down’, i.e., to ‘to transmit in succession (as from father to son).’ This allusion similarly appears somehow characteristic. Sustaining, revisiting, interpreting and disseminating both knowledge and buildings are the interests and responsibilities for the research group at TRANSFORMATION.

First of all, the publication represents the work of a specific research project. Since 2018, the Danish philanthropic association REALDANIA has generously funded ‘Forankring og Forandring’ (English: Rooted Change), or simply ‘FORAN’, in collaboration with KADK. ‘FORAN’ is an umbrella covering a range of diverse projects by the researchers involved. Apart from the researchers engaged in ‘FORAN’, the group presently includes a PhD project as well. Each of the present projects contributes to the main content of this publication. HANDS ON thereby demonstrates the diversity of scopes and displays the common characteristics within the research group.

Each of the authoring researchers has had full authority and autonomy concerning the written content of their contributions. Editorial modifications have been confined to the presented figures apart from more practical aspects of layout, handling of proofreading etc. For the assessment of the content of the articles, we have engaged in an open peer review process with

architect and professor at the Technical University of Munich Uta Graff. She has provided a written statement as a peer report on the research with comments for each article. This peer report is published here as part of the front matter to provide an external perspective on the work and to position the research conducted.

Each article opens with a synopsis that presents the content of the paper. Instead of summarising the content in a preface, we will refer to these small texts and the comprehensive observations by our peer for orientation in the publication.

Rather than focusing on one specific theme, HANDS ON covers a substantive field of approaches to architectural heritage. Some articles deal with traditional architectural working methods, material science, the history of craftsmanship and its relevance and its opportunities of application in a contemporary or future building practice. Others focus on cultural heritage as a contemporary practice and engage with emphasising its present value. While others again engage more philosophically with aesthetic ideas and perception. As such, the publication has a heterogeneous approach to the subject matter.

Nevertheless, there is a common thread that joins the majority of the articles. In the spring semester of 2019, TRANSFORMATION was engaged in a project on the island of Bornholm. This specific project turns up in several of the articles while others are marked by this activity by engaging with experiences and discoveries obtained in connection with the visits to Bornholm.

In the everyday life as researchers at KADK, the focus on a common research production is easily lost between an abundance of activities among the staff members. HANDS ON is a welcome opportunity for the group to get a firm grip on things and align our perspectives on a common goal. At the same time, it is an opportunity to present the ongoing research at TRANSFORMATION and for the researchers to point out directions for further investigation. We hope these articles find you well and look forward to discussing the content with colleagues at the conference HANDS ON and beyond.

Prologue. The KADK Master’s programme ‘Architectural Heritage, Transformation and Conservation’ was developed in order to meet the current and future changes in our physical environment and the associated challenges in a qualified manner on a broad professional level. The focus here is not only on how to repair, restore or transform cultural heritage sites. But with regard to a sustainable consideration of the existing substance of our built environment, the focus is also on more recent buildings and those that are not or not yet listed. Specific methods and perspectives have been developed and implemented in teaching and research which can operationalise the built heritage both ideally and physically.

In order to work on a high level in research and teaching and with a common understanding and commitment the approach of the programme is based on a series of declarations, the ethical codes.1 They are guidelines of a high ethical standard, characterised by an awareness of the holistic perception of architecture and an appropriate withdrawal of possible new intentions towards the carefully determined qualities of the existing built environment as a place for human encounters. Beyond their sentimental value these approaches evenly address aesthetic matters and consider the actual creation and making in the physical realm as condition for action.

The Master’s programme focusses on ‘how to develop the world in which we live: how to further develop the structures, buildings, towns and cities that already exist and, figuratively speaking, how to learn from the building culture that evolved across the ages.’ And there is a keen interest in the fact, that the ‘understanding of materials and tectonics, and knowledge of architectural theory and history are inextricably linked with the concept of sustainable architecture.’2 This latter interest in particular is considered in very different ways in the contributions to this publication. The methodological framework of the programme derives from the intertwining of these spectral divisions.

The program’s research addresses the question of how to develop a more specific approach to the methodology of thinking, constructing and teaching architecture. This aspect is illustrated in various ways in the following contributions. Based upon the heritage of knowledgeable, procedural and creational aspects of architecture, the current and future thinking, action and making of the discipline are defined.

Introduction. The contributions address the different fields of work of the Master’s programme with shifting focus on: education, research and practice. They take various research perspectives and look at a specific topic with a different approach in each case. These attempts can be distinguished as theoretical, historical, technical and phenomenological. In some articles, these approaches complement each other, especially where interdisciplinary research projects are concerned.

All contributions are as much of a systematic and creative approach as of practical relevance. Furthermore, the synergy between research and teaching, one of the programme’s core values, is evident in many of the texts.

Despite the variety of articles, there is a common point of reference that runs through the publication like a red thread. All contributions refer to the Danish island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, which appears to form the common ground and field of investigation for the completely different topics and research questions considered. The insularity turns the local context of research into an enclave, which forms a protected, self-contained framework for all research projects and appears to a certain extent as a laboratory for the acquisition of knowledge. In many cases, field research is actually carried out on Bornholm and work and research is done on site and in reference to specific objects.

In the following, I will briefly discuss the individual contributions in order to locate them thematically, classify them methodically and emphasise their relevance concerning the focus of the Master’s programme. Finally, I will consider the entity of the anthology against the background of the overall theme of the master’s programme.

1. Christoffer Harlang formulates thoughts on a strategy for a contemporary building culture based on his own building project for the extension of a visitor centre on Bornholm.

Two aspects of the contribution should be emphasised: On the one hand, there is the examination of the thoughts of the architect Jørn Utzon, who had already worked on the same situation and had develeped an architectural proposal for it at the beginning of the 1970s, and on the other hand the not explicitly mentioned but legible division of the contribution into three sections in which key aspects of architecture are named.

The reference to Utzon’s work is evenly considered in regard to the theoretical reflection and the process of design and conception of the visitor centre. Studying the way of thinking of another architect holds possible conceptual answers to questions that arise in the context of place and task and that should be answered by contemporary architectural means. In this sense, the differentiated examination of the work of another architect is not just a reference, but always a reflection of one’s own principles and values, which play an essential role in the design process.

The second point mentioned pervades the entire contribution and reflects essential aspects of the design process. The author approaches the central question and the formulation of the task. The preconditions of the design process are named, such as location, programme and history, the relationship between the existing buildings and their surrounding landscape context and the declared intention of maintaining the unity of nature and architecture, with the extension of the ensemble by the new visitor centre. Beginning with a brief description of the site and the existing situation, the author mentions the functional and spatial requirements for the design and finally comes to the construction of the new building and its structural elements.

Through that the article provides an insight into the process of architectural design and shows in an exemplary way the three essential aspects of every architecture. If one follows Kenneth Frampton, ‘the built invariably comes into existence out of the constantly evolving interplay of three converging vectors, the topos, the typos and the tectonic.’3

Despite the mention of essential aspects and elements of the design process, the actual procedural strategies and techniques are not explicitly addressed. The question of strategic choices in the design process remains open. Is it not rather a comprehensible and excitingly readable description of the creative process of designing architecture, into which the article provides an enlightening insight?

2. Nicolai Bo Andersen creates an inspiring connection between significant and relevant current demands on architecture and the search for answers to the question of sustainable aesthetics in the examination of philosophical writings. Based on the juxtaposition of traditional economic theory and the concept of recycling management, Nicolai Bo Andersen formulates a clear appeal to the necessity of the durability of buildings. He clarifies the concept of sustainability, the origin of the term and its historical roots.

In order to substantiate the argument for beauty as an essential aspect of sustainability, Nicolai Bo Andersen explores the concept

of beauty, starting with the Egyptians, through the Greek philosophers, the thinkers of the 17th and 18th centuries, and further to modern times with Heidegger and his thoughts on human existence in the world and Gadamer’s affirmation of the relation between beauty and human play. Amongst other, the author outlines the traditional positions of conservation theory up to the contemporary perspectives.

Considering the specification of highly demanding requirements for architecture, which are self-evident against the background and relevance of the topic, the question how and to what extent these formulated goals can be achieved remains open. But this is not the purpose of his research. Rather the article reads as a theoretical overall concept to the particular projects, which will be explained and examined in the following and which search for answers to the urgent questions of the present on all relevant levels and also on a high aesthetic stage.

On the basis of the values formulated by Plato, as truth, good and beauty, Nicolai Bo Andersen’s contribution ultimately pursues a discourse of values. In that sense, ‘Sustainable Aesthetics’ is not only a profound contribution to durable and resistant architecture but can also be read as an appeal to the creators of building culture to stand up for these values.

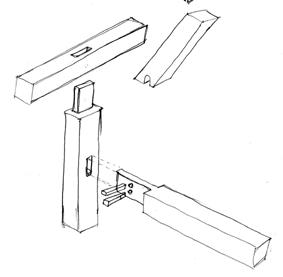

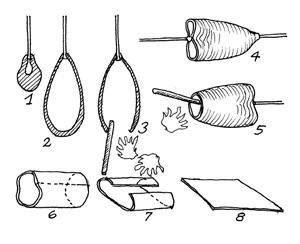

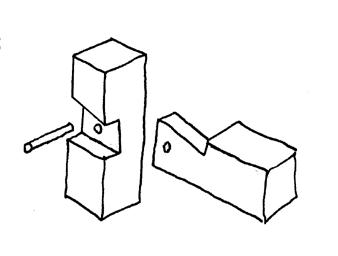

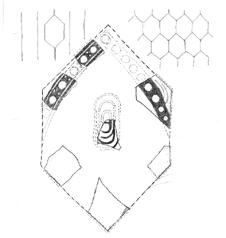

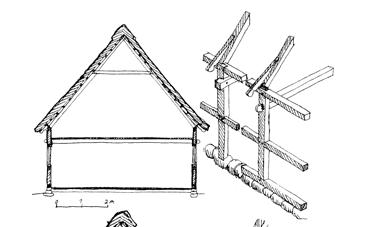

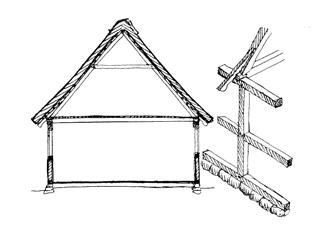

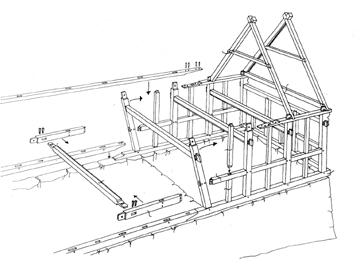

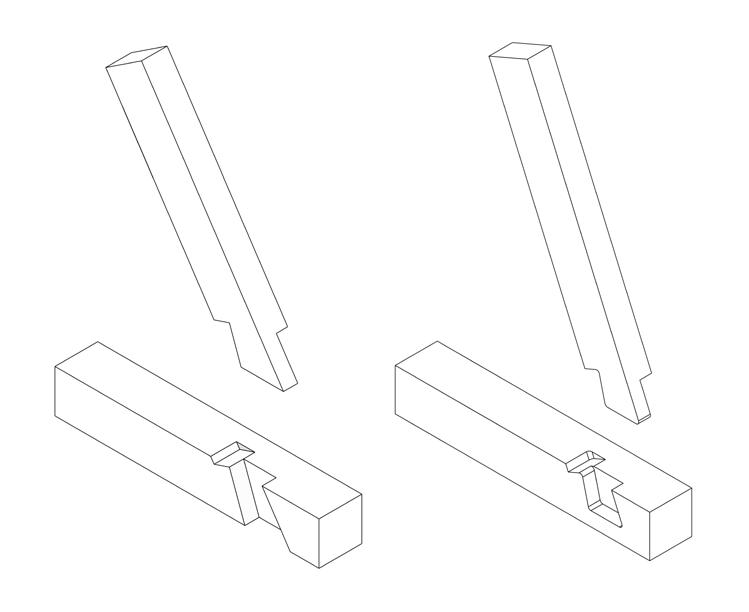

3. In their mutual contribution, Nicolai Bo Andersen and Victor Boye Julebæk very precisely describe the experimental set-up of a design build project. Starting with the basic conditions for the construction of two wooden pavilions, the justification of their identical geometry, the naming of the constructional connections based on a historical survey, their sustainability potentials and the process of their realisation.

Basically, architecture can only be invented and realised in an interdisciplinary way. In projects of this kind, which are realised on a scale of 1:1, this fact can be specified in the sense of an experimental field on a real basis in the cooperation of different participants. For the pavilion on Bornholm, cooperation with apprentices has been established, whereas the pavilion in Copenhagen was built by students. The ‘Joint Matter’ has become a core concern of the project.

The creative and constructive development of the pavilions is based on a detailed study of traditional building techniques in timber construction, which do not require metal connecting elements. Their reinterpretation defines the design and leads to a contemporary architecture. Although the identical geometry and structure of the pavilions, the details are different and refer to the historical principles of the connection typical for the respective locations.

Precise drawings and expressive photographs are part of the design- and practice-based research project. They provide an insight into the construction process, give an impression of the completed pavilions and enrich the textual contribution both visually and in terms of content.

In a different way than in the contribution by Søren Vadstup, the aspect of forward-looking relevance must also be emphasised in this research project. Just as the investigation and scientific analysis of historical building constructions can be fruitful for a contemporary development of resource-saving and site-specific adaptable construction methods, the project conducted and presented by Nicolai Bo Andersen and Victor Boye Julebæk is a productive current contribution to construction methods that will prospectively gain relevance as they deal with the constant ecological and geographical change of coastal regions with regard to possible changes in the course of the coast.

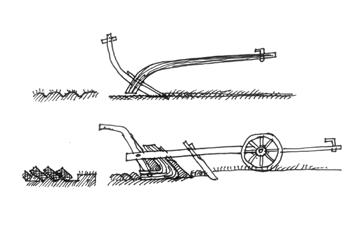

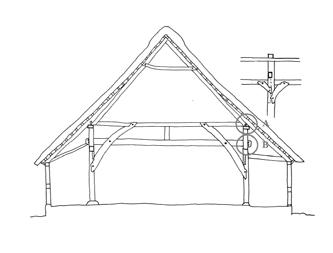

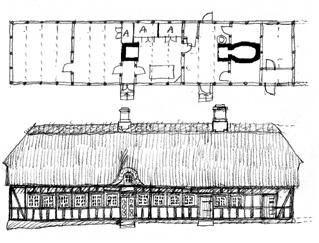

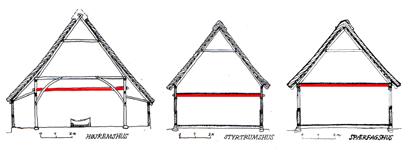

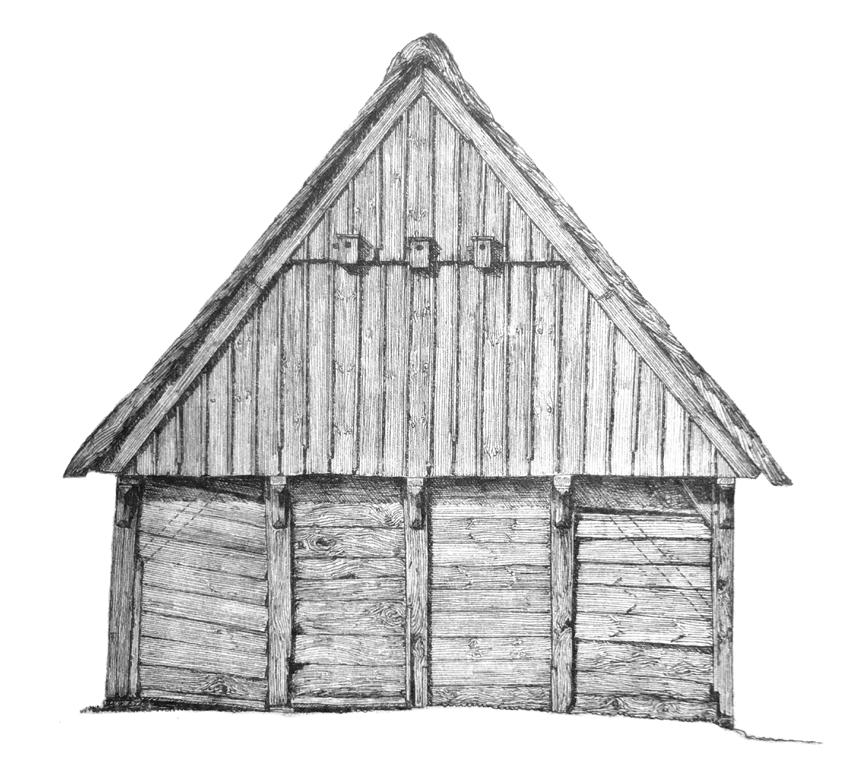

4. In his contribution Søren Vadstrup deals with autochthonous historical building methods of timber-framed constructions in Denmark. Through a precise observation and description of the construction and building method, he fathoms the meaning and origin of this construction method and discusses how it is conceived. Søren Vadstrup adresses the question, why these crooked crosstie-beam structures have such a long tradition in Danish building history and date even further back in the specific context of Bornholm. Most interestingly, this investigation is not only conducted alongside historic means and the reconsideration of the genesis of this constructive building type, but evenly considers etymological and terminological means of its development.

He traces the reason for the frame construction and, based on the linguistic foundation, also clarifies the origin of this construction method in Denmark. It does not only name a building type but rather the underlying process of production and the making. In this sense, language serves as the key to a profound understanding, tracing their origin and evolution. The reconstruction drawings are to be regarded as part of the scientific work, as they have a clear focus, are concise and contribute to the gain of knowledge in a meaningful and legible way.

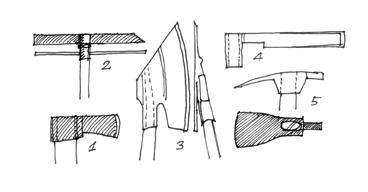

Archaeological findings allow conclusions to be drawn about context specific medieval wood technology and processing tools, which differ significantly from common processing techniques. After an extensive excursus on the history of timber construction and its technology, the author eventually examines his considerations on the specific subject of timber architecture on Bornholm.

The distinct this investigation explores the history of cross-tiebeam constructions, the little it fathoms their potential to serve the contemporary discourse on sustainability and conceiving resources: Due to the minimal use of material, aligned with expertise in craftsmanship and carpentry, they offer a profound resource-saving attempt to architectural construction.

Their inherent tradition of deconstruction, relocation and reassembly bare yet another great potential for adaption as future-oriented technology in wood construction. The perspective necessity to move and relocate buildings due to the elevation of sea-level4 attributes significant relevance to this investigation of historic building constructions and the conservation of knowledge on this construction technique. Although, this aspect is not taken into account as part of the contribution, it opens the realm for the general question, how the investigation and scientific analysis of historic building constructions can contribute fruitfully to contemporary development of resource saving and site specifically adaptable building constructions. Maybe – and this might be a hypothesis – construction methods as such will prospectively gain relevance and become significant references for the development of attempts to deal with the constant ecological and geographical changing of coastal regions in regard to the relocation of buildings due to the elevation of the sea level.

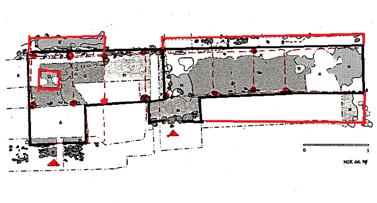

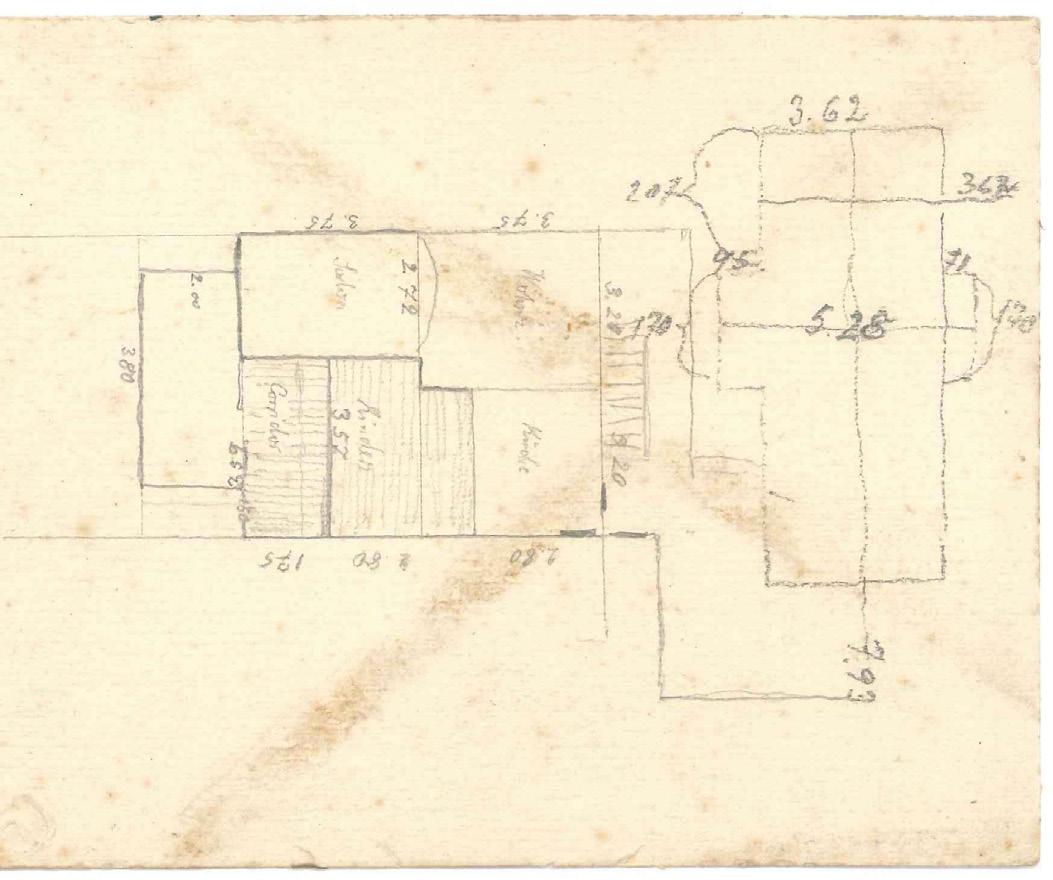

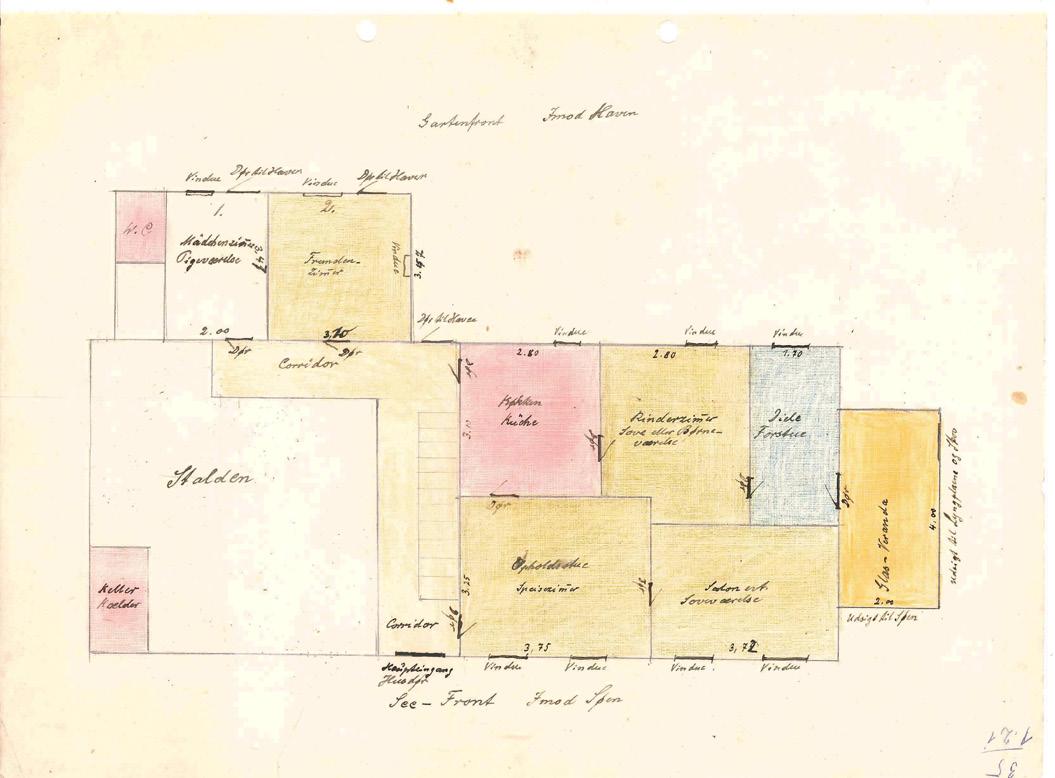

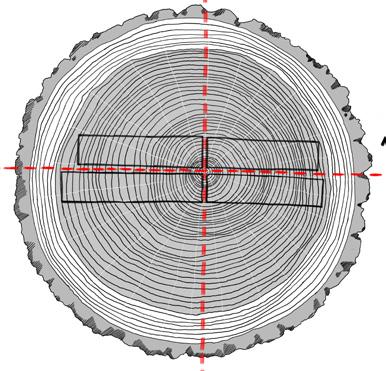

5. Based on a holistic view of the environmental impact of buildings in relation to their total life cycle, Thomas Kampmann examines the question of how an existing building can be reused and thus energy consumption in buildings can be reduced. The aim is to show that it is useful and necessary to anticipate a possible future lifespan of a building and its building components and thus to conduct a credible life cycle assessment. In cooperation with DTU a case study was investigated, the subject of which was a building on Bornholm.

The article gives a detailed insight into the structure of the procedure of a systematic building archaeological survey, graphical documentation with the extensive measurement of the building and

the methods of surveying, as well as cooperation with the conservators, collecting of archive material, comparison of the data gathering with the existing building, determination of construction phases, up to the elaboration of a wooden construction method typical for Bornholm.

Thomas Kampmann concludes his contribution with a critical discourse on the appropriateness of building archaeological survey and summarizes that this type of investigation will raise awareness of the qualities of a building in historical, technical and architectural terms. Regarding to the holistic and sustainable consideration of existing buildings, it is reasonable to carry out archaeological investigations on more recent buildings as well.

The detailed investigations not only lead to a gathering of the physical facts and data of a building, but they also bring the architectural, historical and technical qualities of a building into consciousness. In this sense, the research contribution provides a precise and profound insight into the sense of established and new technical tools in building archaeological survey and shows the necessity of interdisciplinary cooperation in order to achieve the complexity of the aim formulated at the beginning.

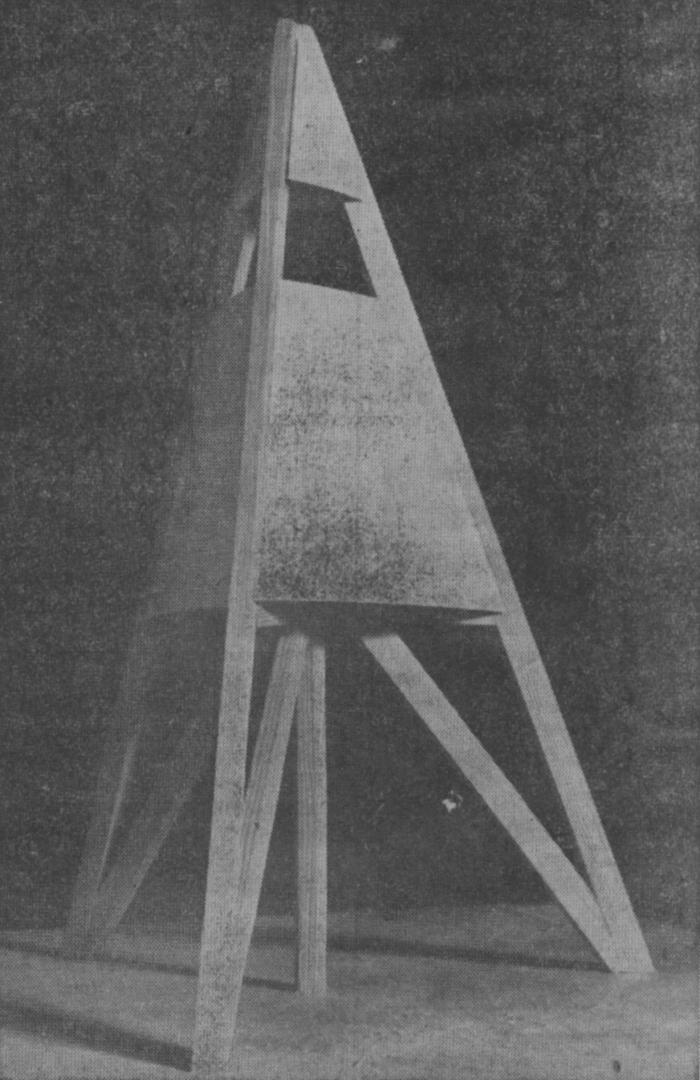

6. In his article, Morten Birk Jørgensen discusses the historical development of an infrastructure building by the architect Jørn Utzon on Bornholm. He focuses on two essential aspects: the history of development that resulted in the work and the work as heritage, as a sculptural architectural form and as an urban edifice, and, finally, he highlights the consequences of the analysis for the contemporary engagement of architecture in the rural context.

While he tries to get to the bottom of the history of the water tower, his arguments are enriched by numerous aspects of the building’s construction process. For example, the political aspect plays a decisive role in the project’s realization when the young architect Jørn Utzon was awarded the contract.

Many aspects worth reading are brought together and could be considered individually as consistent. Even if the contribution aims to find a new reading of Expressionism in Utzon’s work, the interest and explanations are more concerned with the circumstances of its development than with the reasons for the architectural appearance of the building in the context of the surrounding landscape.

The author examines the circumstances that led to the connotation of the water tower in Svaneke as a valued landmark for a local community and asks how this particular case can be of significance and exemplary reference for the recent architectural discourse. The question is also interesting in regard to the fact that Jørn Utzon’s infrastructure building has only been sparsely investigated so far. These are aspects from which questions of cultural heritage, the constitution of meaning and identification also arise. With these questions, the author arouses interest in a more precise examination of the building, its structure and its relevance as a land-based navigation mark.

The contextualization of this singular building seems to be of immanent importance for his analysis, both with regard to the broad spectrum of Utzon’s œuvre and the significant landscape area of the island of Bornholm.

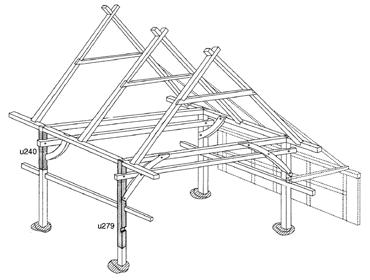

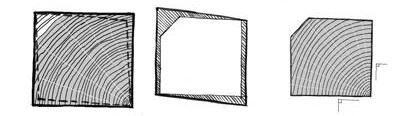

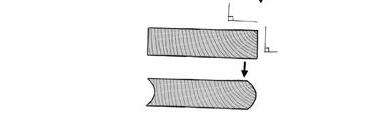

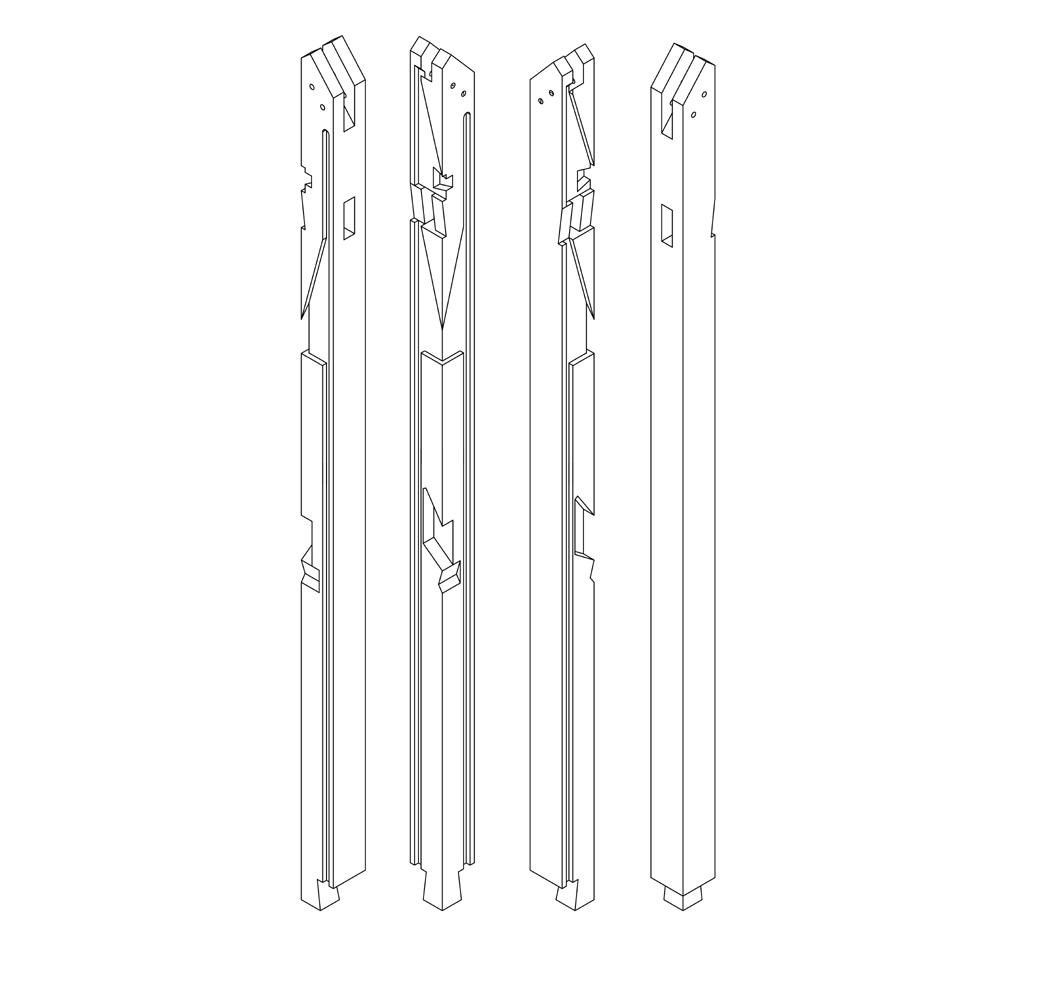

7. Søren Bak-Andersen explores the question of what implications the post-and-plank construction can have for current construction methods. The investigations of historical buildings and the knowledge gained from them will be transferred into the current technology of robotic tooling. With this technology the attempt is made to produce and erect an all wooden pavilion. For

reasons of sustainability, the premise is that the structure has a lifespan that exceeds the duration of growth of the wood used. The model for the construction method and building type is one of the oldest post-and-plank buildings of Danmark, which has been built about 350 years ago.

On the basis of a definition and consideration of wood and its inherent principles, criteria for the selection of the material and its workmanship are established and described in detail. They convey the concrete demands on the project and the targets of the research project. This is based equally on the strengths of historical knowledge, as well as on the profound expertise of wood as a material and the conditions of its processing.

The contribution considers a broad spectrum of relevant aspects in the context of sustainable timber construction: among other things, the obvious cutting of fresh tree trunks for post-and-plank construction is thematized and described in detail; the way in which wood is joined together is considered, as it historically arose from the tools and the possibilities they offer. Also the discourse on the origin of wood, reforestation and timber production and the critical questioning of political goals in favour of sensible and sustainable proposals is an aspect of the investigations made.

A selection of precise illustrations and photographs complement the text both visually and in terms of content. They simplify and deepen the understanding and ultimately convey an impression of the built object and its details shaped by the technology of production.

They attempt to construct a post-and-plank house using modern machinery, based on the inherent principles of the historical construction method and transferred into the present. Based on the strengths of traditional knowledge and craftsmanship, the project uses a novel technology in a way that takes into account the diversity of the living material wood. Therein lies the potential of this innovative contribution.

8. Victor Boye Julebæk explores the relevant question of whether the experience generated by working with specific materials and the phenomenological debate associated with it can contribute to sensual and physical qualities regaining significance and meaning in thinking and building and, understood as a tacit knowledge, becoming more involved in the thinking, making and experiencing of architecture.

His own photographs of clearly outlined sections of building views of simple historical buildings from the island of Bornholm are an essential part of his work.

At first sight it is surprising that the phenomenological observations refer to planar segments of the building elevations, since they aim at a holistic view of the building.

The clear naming of the criteria for the selection of the photographs, the careful consideration and precise description of the clearly defined photographic parts of the building give an impression of the compositional, creative, constructive and ultimately architectural quality of the building as a whole.

Through the methodically clean, photographically precise and linguistically differentiated working method it is possible to convey an overall impression of the building.

The theoretical background forms the essential basis for his work. Thus the concept of resonance plays a decisive role in his work and the perception of the buildings themselves, reading his contribution also evokes a resonance in a figurative sense.

The profound reflection expands one’s own view and opens a new perspective on fundamental qualities of thinking and building architecture. Likewise, the photographically documented works raise the question of both tacit and explicit material knowledge and the craftsmanship of their builders. The contribution succeeds in broadening the awareness of the relevant aspects of architecture through careful and appreciative observation and to extend both the view and the knowledge.

The article is scientifically sound, based on an independent method and a careful phenomenological approach. The project can confirm a high degree of independence of research, which breaks new ground and thus creates opportunities to generate and pass on knowledge.

Summary. It may at first seem surprising that the publication of research contributions is entitled Hands On. The title aptly addresses the different ways of thinking and thus opens up perspectives that correspond to the various approaches to architecture as a holistic undertaking.

On the one hand, it is certainly the reference to practice and the connection to the physical world, on the other hand speaking and acting correlate. According to Hannah Arendt, and as she elaborates in The Human Condition, 5 action and speech are inseparably connected. Action therewith is directly linked to making explicit; implicit knowledge manifests in explicit expression. Wordless action does not exist. Without this mutual interrelation of action and speech, the beautifully and functionally designed world would remain an assembly of isolated things, lacking legibility, meaning and specificity. And without the design of the world as a place worth living in and lasting for generations, all human activity would remain futile and pointless. Through speaking and acting, each person presents himself as a unique and unmistakable individual. They both require reciprocal coexistence: without reference to other people neither of both can be meaningful. Acting and speaking take place in the public sphere, and are therefore impossible to considered private matters, but are of tremendous social impact and relevance. Through action and speech, practice and research, creation and thought, people are able to reveal their identity and their personal skills and talents. Both action and language are essential to gain and pass on knowledge.

The structure of the publication is a stimulating alternation between theoretically grounded and practically oriented contributions. The variety of the topics, the different questions, the fundamentally different focal points of the observations and the related methods of the research projects complement each other in an inspiring way.

The title of this anthology accentuates the desire to avoid an academic distance and emphasises that material substance and the making are directly addressed and dealt with. This is confirmed by all contributions, as they enable the reader to trace the individual genesis of each research project – from the ground of its cultural heritage, through analysis, observation and investigation, towards its recent and perspective attempt.

Each individual presentation not only illuminates a particular aspect of research, but also applies different methodologies according to the questions it addresses. Due to their different focuses – theoretical, historical, technical and phenomenological – the contributions complement each other and show you the complexity of the topic as a whole. The aspect of sustainability is the focus of all contributions. The critical questioning of one’s own actions always appears essential. Thus, the research projects presented are always developed with a view from the present and with the question of their potential for the future in mind.

In the compilation of the contributions, it becomes clear that it is only when the actual knowledge is approached from different perspectives that a holistic approach to a complex subject area such as building in existing contexts becomes possible.

Research, education and practice are areas that stand on their own and require different methods, but which nevertheless interlock, stimulate each other and lead to new insights. The transfer of knowledge and the resulting changes in viewpoints become clear in many contributions and lead to new insights and knowledge creation. In this sense, the articles succeed in demonstrating that architecture is both a profoundly scientific and an elementary artistic discipline.

Given the variety of approaches and attempts, the present publication adequately reflects this fact because the diversity of the contributions opens a broad and manifold spectrum of views.

The individual contributions can stand on their own and be read independently. In the context of this publication, they complement each other as a whole and convey themselves as an interconnection of historical investigations and the knowledge gained from them with current questions on building technology coupled with a high design standard.

This is not only about preserving knowledge, but always directed to the transformation of the insights gained from building archaeological studies into a contemporary practice of preservation, adaption and further construction. And this, as Søren Bak-Andersen states in his text, ‘by continually building upon history, as a continuation of tradition, and not in mimicry’ to uphold ‘our cultural foundation and connection to tradition.’6

The publication as a whole is thus the valuable and comprehensive product of a research activity, which corresponds to the academic quality within the Master’s programme ‘Cultural Heritage, Transformation and Restoration’ and with its different perspectives contributes to the development of the research field of the programme itself. It is also of interest to all those who are interested in architecture which is based on historical knowledge, and which is meaningful in terms of construction and craftsmanship, of high design quality and thus sustainable in every respect.

Through the individual contributions from the research with their respective genuine origin, the publication has a relevant scientific quality that I recommend to read. The anthology is led by the intention to draw the line from history to present, grounding the recent theoretical and practical acting in the discipline of architecture in a consecutive development from heritage to current state and beyond to future perspectives. History is thereby above all understood as the knowledge embodied in the built environment itself. Hands On is an imperative to grasp the knowledge derived from the investigation of historic architectural contexts and to channel it into the present discourse of the discipline as well as the creation practice and the making. The heritage of preconceived knowledge is retraced and considered the basis for further investigation, development and knowledge-creation.

1. Harlang, Christoffer (ed.); Steenberg, Charlie (ed.); Andersen, Nicolai Bo (ed.); Julebæk, Victor Boye (ed.), Lost and Found. Architectural Transformations in Architecture, Copenhagen, 2013, p. 26f.

2. https://kadk.dk/en/programme/cultural-heritage-transformation-and-restoration

3. Frampton, Kenneth: Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1995, p. 2

4. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC: The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, Sept. 2019.

5. Ahrendt, Hannah, The Human Condition Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958. German Title: Vita Activa oder Vom tätigen Leben, 1960.

6. Bak-Andersen, Søren, Post-and-Plank Today – All-Wood-No-Nails, Robotic tooling utilising historical material knowledge, Discussion – Why we did it. In: Hands On, 2020.

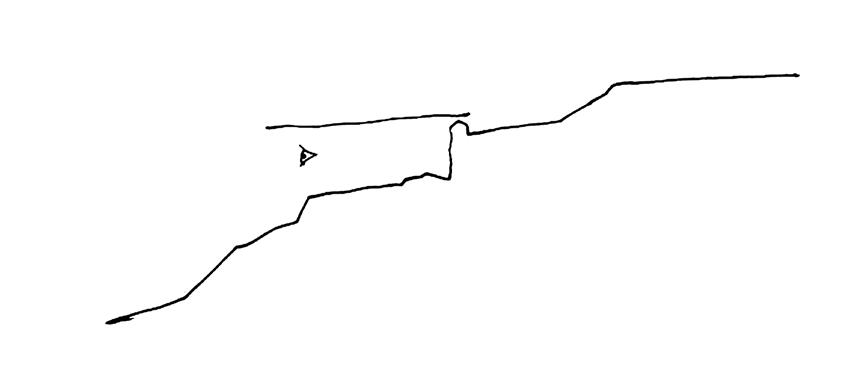

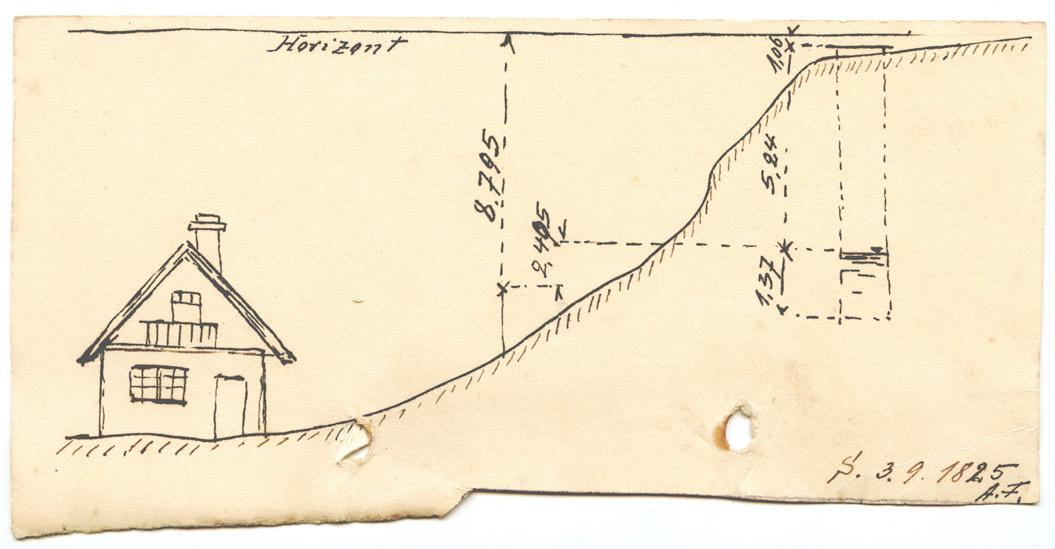

Christoffer Harlang. The Visitor Centre at Hammershus is discreetly incorporated into the rocky, west-facing slope above the castle moat, on a spot originally suggested by Jørn Utzon in his 1971-proposal for a visitor centre. Utzon’s project was never realized but formed the basis for a international design competition won in 2014 with a project developed as a collaborative venture between Arkitema, Christoffer Harlang Architects and BuroHappold Engineers. This paper unfolds how the architecture reads and processes the curvature of the landscape, by developing a number of geometries that form the basis of the vis- itor centre’s floor, walls and roof. By studying the terrain profile and superimposing the morphology on top of the organisation model, we developed a complex spatial figure that, through the use of three principal modular geometries, was able to follow the shape of the site, establish a safe foothold and provide the necessary orientation towards the view from within the building.

Hammershus Revisted. In the middle of the Baltic Sea lies an eastern outpost of Denmark: the rocky island of Bornholm. Here, on the northern tip of the island, we find the largest castle ruin in Northern Europe, the 12th century structure Hammershus, whose new visitor centre is the subject for this text.

Bornholm, a community of around 35,000 souls, was previously known for its fishing but is now primarily a destination for entrepreneurs and tourists with an interest in gastronomy and arts and crafts.

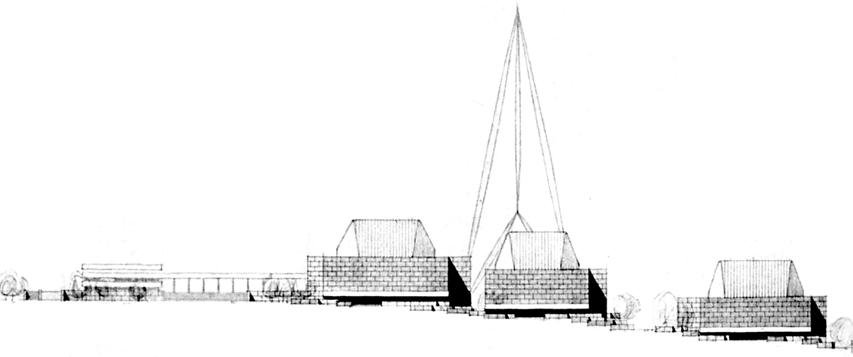

The visitor centre is discreetly incorporated into the rocky, west-facing slope above the castle moat, on a spot originally suggested by Jørn Utzon (1918–2008) in his 1971-proposal for a visitor centre. Utzon’s project was never realised but formed the basis for a prequalified international design competition which we won in 2014 with a project developed as a collaborative venture between Arkitema, Christoffer Harlang Architects and BuroHappold Engineers.

The competition called for a project that was ‘rooted in Utzon’s proposal and the architectural and landscape qualities it contains.’ As part of our preliminary investigation, we found that Utzon’s vision of an articulate building raised on stilts indeed represented a reversible and deliberately gentle approach to landscape in general and the site’s vegetation and characteristic features in particular, but also that this approach was unable to satify the brief’s functional and spatial requirements, which were about four times as high as the ones Utzon operated with.

Jørn Utzon envisioned a composition of wooden bridges and platforms connecting a number of simple wooden houses with mono-pitched roofs supported by wooden posts. It has been reported, but not verified, that the basic idea for Utzon’s tentative composition of oblong buildings at Hammershus came to him during a visit to the Ganges River in India. Here Utzon admired how boats found their place in between each other in a highly complex, tentative but rational way that Utzon found very beautiful.

This compositional mindset has a direct reference in Alvar Aalto’s motifs1 in the siting of a building or building complex, where apparently random but very beautiful juxtapositions and transitions are prioritised over orthogonal schematics and regularity.

Alvar Aalto’s architecture – and Utzon’s – diverges from dogmatic modernism’s ethos of order and geometric regularity, introducing a more open-minded understanding of the interplay between site and building, which is based on intuitively arranged tensions and balances. This tradition where building and landscape find each other in a mutual understanding is as old as building culture itself, but it is in the Nordic modernism that it is given such an inspirational contemporary interpretation.

From the very beginning of the development of our ideas for the competition scheme, we felt that something akin to Utzon’s strategy would be right, but on the other hand something very different was needed, we thought. We were looking for something that would enable the more comprehensive programme to be folded into place without disturbing the fundamental balance of the place.

So we started to look at what was already there as statements from the dialogue between man and nature. At Hammershus, the man-made and the natural have been working together for centuries. The castle is the product of a fruitful meeting between the rock’s prominent position, 75 metres above sea level, and the ability of time to shape the monument with stone and timber, and let the shape be informed by the contours of the terrain.

The monument’s encounter with the landscape is unique to Hammershus. The ruin lies in the borderland between the constructed and the organic, and the experience of the landscape is therefore an inseparable part of the experience of the ruin. Understanding this and the movement in the landscape spaces is key to understanding our approach.

Both the story and the monument itself are staged through the visitor’s walk in the countryside, in the same way Utzon suggested – building and path thus become a means of framing monument and nature.

The scenery is hierarchical, dominated as it is by the experience of the castle, and we felt that the new visitor centre had to submit itself to that. To maintain the hierarchy, a dynamic landscape path was designed independently of the centre’s function. The bridge is also an independent process and part of the staging. The bridge thus becomes an architectural element, a walk through the forest and the valley, which emphasises and highlights the violent dynamics of the landscape along the route.

The same narrative runs through our project for Hammershus Visitor Centre. At the edge of the rocky moat we have traced and adapted the curves of the landscape space, translating them into geometries that define the visitor centre’s floor, walls and roof.

The site and the surroundings encouraged us to work with complexity in more than one sense. How do you place a house on a slope without destroying the slope? How do you handle the premise that the rationality and economy of the building require modular buildability, while nature responds with levels and directions that are much more complex? How does one achieve a heterogeneity that is not chaotic or messy but holds an inner balance? Which is tranquil.

We found some pictures of mountaineers attached to the cliffs with wires. We found pictures of Nepalese houses standing on stilts on a hillside. We went to the library for in the history of architecture as well as in contemporary architecture to find inspiration on how to build a cliff edge; how have people done such a thing before?

The curvature of the site is so complex that we had to begin by imagining something which, on the one hand, is suitable for the function, but which, on the other hand, also consists of smaller parts or entities capable of responding to the inherent morphology of the place. So the building we were designing had to be able to satisfy both demands, where the landscape is one and the functionality the other.

On aerial photos and the site plan of Hammershus you can clearly see that we have traced the landscape, and how the age-old conversation has informed our design. (Fig. 2, 5) We tried to figure out how to intervene in that. How do you draw a path, place a wall and make a space in such a set-up? Those where the questions we asked ourselves.

As a consequence, we came up with the idea that the terrain should be somehow distilled and transformed as a self-acknowledged piece of modern architecture and translated into a building that does not angle for attention but instead seeks to frame the visual connection with the castle ruin, the landscape space, the sky and the sea.

If you look at the photo in figure 1, you will see how the building is reduced – or exalted – to a floor or a platform for the viewer’s participation in the space, constituted by the landscape and the castle ruins.

The 1,200 m2-building is based on a simple programme: about half of it is used for various forms of storytelling about the castle ruin and its dramatic history, while the other half contains café, shop, education unit and toilets. But during our development of the design, we came up with the idea of

adding an additional functionality to the programme in the shape of a public roof terrace or platform, which constitutes the third and very significant element of the buildings programme.

The building is organised with two kinds of spaces: open spaces with public access and direct visual contact with the landscape and the castle ruin; and, against the slope, a variety of closed spaces that provide back-up and secondary functions, with limited access to the public. The layout thus follows familiar principles known from both Mies van der Rohe’s open plans with their closed service cores and Louis Kahn’s thinking, which distinguishes between served spaces and servant spaces

The exhibition consists of simple panels, which are mounted on the concrete walls, a large analog model and 3D animations projected directly onto the walls of the exhibition spaces.

By studying the terrain profile and superimposing the morphology on top of the organization model, we developed a complex spatial figure that, through the use of three principal modular geometries, was able to follow the shape of the site while establishing a safe foothold and providing the necessary orientation towards the view from within the building. (Fig. 3)

As a counterpoint to this tight but adaptable rhythm, we tugged the building’s servant spaces up against the slope, using free geometries when arranging the load-bearing, in-situ cast concrete walls. These undulating structures, which enclose spaces by wrapping around them, were conceived as fluid sequences of insulated, double-layered external walls and simple partitions that interact by forming dynamic spatial relations, with no visible difference between inner and outer walls. Radius for the curvatures was studied and, based on the effects at Arne Jacobsen’s kayak club at Bellevue in Klampenborg, the guiding geometry for inner corners was fixed at an external radius of 90 cm.

This dichotomy, which divides the building’s geometric entity into two parts in the form of modular repetitions and organic exceptions, respectively, articulates the building’s overriding organisational pattern with served and servant spaces. The same dichotomy characterises the building’s tectonic structure, which consists of two separate but interconnected elements: the folding and the lining. While the folding comprises the floor and the undulating cast walls, the lining is the applied level with roof construction, panel walls and doors.

This obvious reference to the craft of the tailor originates from the writings of Adolf Loos in his legendary Das Prinzip der Bekleidung, published in 1898, where Loos explains that each material has its own design language ‘and none can claim the shapes of another material. Because the forms are formed from the usability and production method of each material, they have become with the material and through the material. No material allows an intervention in its circle of forms. Anyone who dares to intervene like this will brand the world as a fake. But art has nothing to do with falsification, with lies. Your paths are thorny, but pure.’ 2

The building is constructed with in-situ cast foundations, floor and walls, and with roof structure in laminated wood and oak. Windows are in steel frames with oak casings; doors and partitions in oak planks. Footbridge and platforms likewise made of oak planks.

These elements, which are all made from sawn oak, serve to inhabit the folded concrete structure, adding a welcome and necessary touch of tactile warmth and functionality to the interiors. Foldings occur in a matter or in the crust of a material when the material’s surplus or structural displacements in the distribution of layers reach a certain level. In this case, the folding is used as an architectural device that makes the spatial figure interact closely with the morphology of the landscape, as opposed to a building designed as an object in the landscape.

The folding’s obvious reference to textiles is elaborated in the visitor centre’s artwork as the artist group AVPD has created an integrated work of art that doubles as room divider between the education unit and the café.

The idea of fitting the building seamlessly into the landscape has led to the

notion of the building’s roof as one large wooden deck, which – thanks to a variety of gently sloping ramps – connects to the new path system and the parking facility.

The project carries on a tradition that may be described as Nordic as it draws primarily on the work of Gunnar Asplund, Sigurd Lewerentz and Alvar Aalto, using and expanding their ideas to emphasise the correlation of space, tectonics, matter and detail. Much of the furniture and fittings, including door handles, lamps, benches, shop fittings and tableware were therefore custom-designed for the building, and, together with the service building and the visitor centre’s bus stop, conceived and designed as an integral part of the architecture at Hammershus.

In Denmark this was not unsual a few decades ago in the works by the protagonists of modern architecture such as Arne Jacobsen, Kay Fisker and Palle Suensson and was last seen in the magnificient church by Jørn Utzon in Bagsværd, completed in 1976.

This ambition to attempt a continuation of the now almost abandoned buildding culture is not a sentimental reference to a lost world of coherence but instead an attempt to safeguard what Frank Lloyd Wright called the integrity of a building:

‘What is needed most in architecture today is the very thing that is most needed in life – Integrity. Just as it is in a human being, so integrity is the deepest quality in a building...if we succeed, we will have done a great service to our moral nature – the psyche – of our democratic society... Stand up for integrity in your building and you stand for integrity not only in the life of those who did the building but socially a reciprocal relationship is inevitable.’ 3

Being able to mentally switch fluidly between scales, between the reading of a landscape and the mastery of a building’s design and all its parts, is one of the most important aspects of all design processes, it seems to me. And that was exactly what we were striving for in our quest to continue a contemporary building culture at Hammershus Visitors Centre.

1 For a further discussion of Alvar Aaltos approach to siting, see: Christoffer Harlang, ‘The Building of the Light’, in Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum , edited by Aase Bak (København: Arkitekturforlaget B, 1999), p. 37–49, and Alvar Aalto, ‘The humanizing of architecture’ [1940] and ‘The trout and the stream’ [1948], in Alvar Aalto in His Own Words , edited by Göran Schildt (Helsinki: Otava, 1991).

2 Adolf Loos, Spoken into the void , Collected Essays by Adolf Loos, 1897 – 1900 (Boston: MIT Press, 1987).

3 For further reading on Frank Llyod Wright, see: Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, ed., The essential Frank Lloyd Wright: Critical Writings on Architecture (Boston: Princeton University Press, 2010).

Nicolai Bo Andersen. In sustainable building culture, three factors may constitute a theoretical framework: technical, functional and architectural parameters. In this perspective, to achieve longevity, a building must be technically robust, functionally adaptable and aesthetically durable. But what does it mean when we say that a building is ‘classic’. Why is it that even though aesthetic ideals seem to change all the time, some buildings have the capacity to talk to us across temporal distance? It is argued that when a work of architecture become listed, it is because it is able to speak to us aesthetically through temporal distance. It is concluded that aesthetic sustainability is fundamentally a hermeneutic question. In this sense, the work of architecture is aesthetically sustainable when we understand something and ourselves. Some buildings talk to us because they say something true (alétheia) about being in the world.

Resources. In traditional economic theory, thinking is linear. Materials are regarded as an unlimited resource, and waste is considered gone when it has left the economic system.1 Materials are put into the economy where they are processed, and when the products and buildings are outdated the resources disappear from the economy as so-called waste. In this traditional economic thinking, focus is on the economy as such and not the larger material context. If the planet, on the other hand, is considered a closed system where only solar energy is fed from the outside and only low-grade thermal energy leaves, then materials are not an infinite resource and waste is not something that disappears.2 Energy is exchanged with the rest of the universe, whereas matter remains in the system since nothing is created and nothing is destroyed, only transformed. In this understanding, the finite material resources are continuously degraded with each transformation.

In a circular economy, waste is not considered non-existent but rather a resource in itself that may be part of the system one more time. In the conventional understanding of circular economy, it is a question of rethinking by reducing, reusing and recycling.3 However, both reusing and recycling material resources require energy and even more resources to be added for each transformation. A more elaborate version of the concept of circular economy advocates a hierarchic list of nine R’s: (1) Refuse, (2) Reduce, (3) Reuse, (4) Repair, (5) Refurbish, (6) Remanufacture, (7) Repurpose, (8) Recycle and (9) Recover energy.4 In this understanding, refusing consumption is better than reusing, which again is significantly better than recycling. In other words, in a true circular economy it is best to keep the resources in the system as long as possible.

In Danish building regulations, only operational energy used for e.g. heating and cooling is considered, whereas embodied energy related to all the life-cycle stages, from the extraction of raw materials to the end of life, does not count.5 However, recent life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies show that in the lifetime of new buildings, embodied energy accounts for significantly more greenhouse gas emission than operational energy.6 In a near future with increasing use of low-emission energy coming from wind and sun, the difference will be even more significant. All this point towards a strategy that prioritises ‘[to] sustain and preserve what is already made, in this case the current building stock, and boost its performance from the perspective of material reuse and energy efficiency.’7 In other words, in a truly sustainable building culture longevity is fundamental.

Sustainability. The concept of sustainability was used for the first time in 1713 by Hans Carl von Carlowitz in his book Sylvicultura oeconomica, oder haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung zur wilden BaumZucht 8 As a reaction to the acute scarcity of timber caused by the heavy exploitation of forests by the mining industry, von Carlowitz described how to balance growth and harvest through the principles of rationalisation, substitution and limitation. Timber should only be cut to the extent that forests could regenerate and ensure material resources for the future. A similar long-term thinking is expressed by Ernst Haeckel who coined the term ecology in 1866 using the Greek oikos that means ‘house’ and -logia that means ‘explanation’, i.e. the doctrine of household. Similarly, the word economy is created by combining oikos and -nomos, meaning ‘house’ and ‘law’, respectively, i.e. the description of the rules governing production and consumption of goods and services.

Today, the most common definition of sustainability is presented in the Brundtland Report of 1987, calling for ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’9 In continuation of prior descriptions of sustainable development, this definition underlines the importance of focusing on long-term interests, not short-sighted profit. In continuation of the Brundtland Report’s understanding of sustainability as compatible with economic growth, different positions call for rationalisation, e.g. through energy efficiency, building insulation and technological development. Other positions call for substitution, e.g. through reusing and recycling by means of circular economy and principles of ‘design for disassembly’, as outlined above.

However, if the aim is continuous economic growth, the speed of reuse and recycling must constantly be accelerated, effectively resulting in a decrease of product lifespan.10 The notion of sustainable economic growth, also known as ‘green growth’, has thus been criticised for being a conceptual contradiction

since the economic system, as described above, is a closed and limited system.11 Exponential economic growth on a planet with limited material resources is simply not possible. In continuation of this, a possible interpretation of a truly sustainable building culture is limiting the use of resources by conserving as much as possible, preferably in the same amount and quality as the existing. In this understanding, exploitation of the earth’s resources may be limited by prolonging the lifespan of buildings through conservation, transformation and restoration.12

Conservation. In A History of Architectural Conservation, Jukka Jokilehto points out that conservation is in fact a cultural question, arguing that ‘[i]n the pre-modern world, it was part of a process where one learnt not to repeat mistakes, and instead recognised successes, taking these as a reference for further improvement.’13 In this perspective, practical knowledge has been developed and cultivated through generations in a process of continuation. Classical authors gave particular attention to durability. More than two thousand years ago, Vitruvius argued that ‘[a]ll these [the art of building, the making of time-pieces, and the construction of machinery] must be built with due reference to durability, convenience, and beauty.’14 Later, Alberti described his concern for the unnecessary destruction of buildings and the need for maintenance and conservation, crying out: ‘God help me, I sometimes cannot stomach it when I see with what negligence, or to put it more crudely, by what avarice they allow the ruin of things….’15

Modern conservation theory may be seen as a continuous negotiation between two positions, one arguing for maximum intervention, the other for minimum.16 As the architect responsible for the restoration of many medieval castles and cathedrals, Viollet-le-Duc argued for the unity of style.17 According to Viollet-le-Duc, ‘to restore a building is not just to preserve it, to repair it, and to remodel it, it is to re-instate it in a complete state such as it may never have been in at any given moment.’18 The ideal of architectural conservation was the unity of the structural and visual style of the building. In opposition to this, John Ruskin argued that stylistic restoration ‘means the most total destruction which a building can suffer.’19 To Ruskin every building is a unique creation made by an individual architect in a specific historic context. The specific qualities of the work of architecture situated in time and space can never be repeated, and the building consequently not restored. Instead, the original material that has ‘matured’ through the passing of time, wear and weathering should be protected as long as possible. In continuation of Ruskin, the Manifesto of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings underlines the importance of conservation, arguing that ‘[i]t is for all these buildings, therefore, of all times and styles, that we plead, and call upon those who have to deal with them, to put Protection in the place of Restoration.’20 The aim was to conserve the buildings materially and ‘hand them down instructive and venerable to those that come after us.’21

In the 20th century, the Venice Charter is considered to be the principal document in architectural conservation. Describing buildings and monuments as imbued with a message from the past it is pointed out that ‘The common responsibility to safeguard them for future generations is recognized,’22 thus underlining the importance of a long temporal perspective. The Charter continues by arguing that ‘It is our duty to hand them on in the full richness of their authenticity.’23 In continuation of the principles described in the Venice Charter, Sir Bernard M. Feilden reasoned that ‘…a historic building is one that gives us a sense of wonder and makes us want to know more about the people and culture that produced it. It has architectural, aesthetic, historic, documentary, archaeological, economic, social and even political and spiritual or symbolic values; but the first impact is always emotional, for it is a symbol of our cultural identity and continuity – a part of our heritage.’24 To Feilden, conservation is about preventing decay and ensuring that the meaning of the object continues to be comprehensible.

Just as the values of architecture, as described by Feilden, are multiple, the reasons for conservation are numerous, including personal, social and scientific values.25 In a Danish context, the law regarding listed buildings and conservation of buildings and built environments allows the Minister of Culture to list buildings or independent landscape architecture of ‘significant architectural or cultural-historical value.’26 Some researchers challenge the materialistic understanding of cultural heritage and argue that cultural heritage is ultimately intangible. Criticising the authorized heritage discourse, Laurajane Smith argues that cultural heritage is a cultural and social process that occurs at

particular locations or by undertaking specific actions when values, meanings and identity are created and recreated.27

In contemporary conservation theory, sustainability and conservation are considered two sides of the same coin. According to Staniforth as referenced by Muñoz Viñas, the whole purpose of preserving cultural heritage is equivalent to the aim of sustainability, i.e. to ‘pass on maximum significance to future generations.’28 As ways to secure cultural meaning and reduce the use of resources to the benefit of current and future generations, both sustainability and conservation aim at longevity. The question is how may architectural longevity be achieved? Buildings change all the time due to decay caused by physical effects and alterations demanded by change in use, just as changing ideas of beauty seem to cause constant alteration. Using Vitruvius’ above-mentioned distinction between durability, convenience and beauty as a framework, it may be argued that sustainable building culture is about achieving technical durability, programmatic usability and aesthetic quality.29 The question is why some works of architecture quickly go out of style, while others have greater resilience to changing ideas of beauty.

Beauty. While both conservation and sustainability aim at longevity, ideas of beauty seem to change all the time.30 One may even get the impression that architecture more and more is a question of fashion and that stylistic features change ever more rapidly. In the Orient, beauty was connected to light and shine. The Semitic god Baal, the Egyptian god Ra and the Persian god Ahura Mazda were all personifications of the sun. The Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton, ‘the spirit of Aton’, and his wife Nefertiti, ‘the perfect’, changed the belief of Egyptians from many gods to only one, Aton, the god of the sun. The Pythagoreans founded the classical understanding of beauty as a question of harmony and proportions to the cosmic order, whereas the Greek sophists identified beauty in the concrete, sensuous world. Socrates, on the other hand, believed that beauty was not a physical thing but must be found in what beautiful things have in common, linking beauty to the useful and the appropriate.

For Plato, truth, good and beauty are inseparably linked. The sensuous beauty is relative, transient and changeable, pointing towards the spiritual beauty of the physical world. According to Plato, beauty must be understood as an absolute, eternal and unchangeable idea. For Aristoteles, on the contrary, it is the ideas contained in the physical forms that make things what they really are. Beauty is unity in diversity. In Aristoteles’ classic definition, beauty is defined by the fact that nothing can be removed and nothing added. For Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, beauty again had something to do with light. Sensuous beauty was caused by something spiritual in the form itself, the light from the highest god, the One. This understanding grew into the Middle Ages where beauty became a question of divine perfection identifying god with a shining light, a luminus current, penetrating the universe.

Until the middle of the 1700s, beauty was regarded as something divine, manifested as an absolute quality. But by the beginning of the modern world, David Hume argued that beauty only exists in the mind of the perceiver and not in the things themselves. And with Immanuel Kant the classic idea of beauty as an objective property was definitely replaced by an understanding of beauty as a subjective product of human consciousness. For Kant, beauty is characterised by disinterested pleasure, universality and regularity. Aesthetic thinking in the mind of the subject is a play between sense and imagination, manifesting itself in a kind of well-being that supports the subject in being realised as a moral creature. According to this perspective, beauty is the symbol of moral good.

Even though the concept of beauty has existed as long as humanity, the concept of aesthetics was founded as late as in the 18th century. Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten defined noeta as the object of logic, whereas things perceived were defined as the science of aesthetics 31 Baumgarten do not consider logic and aesthetics as contradictory, but as two mutually complementary ways to knowledge. For Baumgarten, aesthetics is not just a matter of personal taste, but rather a scientific question; episteme aisthetike. Aesthetics is, in this understanding, the philosophy of sensitive cognition identified with the experience of beauty. In a modern understanding, the work of art is no longer a manifestation of an eternal idea or divine order, but rather considered the result of the artist’s personal experience. However, the concept of beauty has seemingly disappeared from the vocabulary just as the concept of aesthetics is considered precarious. Today, theories of art and architecture are often inspired

by social and cultural studies, represented by, for instance, Pierre Bourdieu and Michel Foucault. And in art theory, the description of formal language and stylistic features of architecture is in focus, in favour of aesthetic experience.32

Experience. According to Martin Heidegger, human being (Dasein) is always practically engaged in the world.33 In this everyday ready-to-hand (Zuhanden) activity, perception is never isolated but always related to something specific. Through the practical use of equipment (Zeug), we understand the material world and the things we use without giving it much thought, just as we continuously test new potentials by making projections (Entwurf) based on past experiences. However, if the equipment suddenly breaks, the practical understanding is replaced by an understanding of the equipment as an object. When the everyday relation characterised by practical concern (Sorge) is broken, the material world is looked upon with an analysing and objectifying gaze. This present-at-hand (Vorhanden) perspective makes us observe the world in a more theoretical and scientific way.

However, both in the ready-to-hand, everyday, concerned activity and in the present-at-hand, analytic objectiveness, the world becomes distant. To Heidegger, our relation to the world is neither just instrumental nor scientific, but also aesthetic.34 In the eyes of the artist, a pair of shoes is not just ordinary and trivial equipment for walking, just as the picture is not simply a result of an objectivising, scientific description. Rather, art is aesthetic knowledge, but on its own terms ‘a becoming and happening of truth.’35 Art is about beauty, but not in the banal sense of the word, rather as a question of disclosure. To Heidegger ‘[b]eauty is one way in which truth essentially occurs as unconcealment.’36

A work of architecture may be understood as a spatial articulation of physical matter.37 The formal elements used in building may have to do with the form, colour, proportion and material effects,38 just as rhythm, daylight and acoustic effects are elements in experiencing architecture.39 Material properties, structural principles and tectonic articulation may allow bodily communication as resonance through sensing or affective involvement, and the produced feeling of identification between the body of the house and the felt body of the perceiver may create meaningful situations.40 In this perspective, experiencing architecture is not a question of ‘understanding’ the work logically, just as it is not a question of ‘understanding’ a piece of music. Rather, the elements of architecture constitute a vocabulary in its own right, which can be communicated aesthetically through sensing and affective involvement. Through the vocabulary of architecture, the architect articulates matter into a meaningful whole, which can be experienced by a perceiver.

Meaning. According to Hans-Georg Gadamer, the work of art is dependent on a process of abstraction.41 It may be perceived as a ‘pure work of art’ if the context in which the work is rooted is disregarded. In a process of ‘aesthetic differentiation’ the work exists in its own right, independent of reference to social, religious or political interests. The positive side to this mode of pure perception is that art is art on its own terms. What is important is how the work works, not external references such as stylistic features, concepts or fashion trends. However, when we look upon a thing, is it never not just characterised by simple perception of what is there, but rather always associated with an understanding of something. Thus criticising the mode of pure perception, Gadamer argues that ‘[o]nly if we “recognize” what is represented are we able to “read” a picture; in fact, that is what ultimately makes it a picture. Seeing means articulating.’42

To Gadamer, pure perception is an abstraction that reduces phenomena. The work of art is more than just simple perception since its meaning and content are determined by the ‘occasion’. When the relation to the world is lost, the work of art loses its meaning because ‘only when we understand it, when it is “clear” to us, does it exist as an artistic creation for us.’43 In this perspective, a building is never just a work of art. A spatial arrangement of pure formal elements or only material effects would make no sense since our understanding of what we perceive is closely dependent on how the work is related to the world. At best, the pure work of architecture would be no more than stage design or a ‘Potemkin village’.

Using the concept of play, Gadamer understands the work of art not just as a question of pure perception but rather as ‘an event of being—in it being appears, meaningfully and visibly.’44 When a play or a piece of music is per-

formed, the play reaches presentation through the players. Similarly, experiencing architecture is the coming-to-presentation of the work through the participation of the perceiver. Experiencing a work of architecture is neither just characterised by sensuous stimuli nor is it a material manifestation of an eternal idea or divine order. The meaning of the work is not an objective property of the thing itself nor a purely subjective question. Rather, in the work of art, presentation is an ontological element in which the presented experiences an increase in being by being experienced. The picture (Bild) is not just a copy (Abbild) but a re-presentation of the original (Urbild) as the ‘specific mode of the work of art’s presence is the coming-to-presentation of being.’45 In this perspective, aesthetic experience is not a question of subjective taste or personal opinion but an event in which a world is coming to presentation.

World. The Parthenon, located at the Acropolis, is the archetypical example of an architectural synthesis between matter, place and use. According to Heidegger, ‘[a] building, a Greek temple, portrays nothing.’46 Rather, the work of architecture ‘sets up a world’, and in this ‘setting forth’ ‘[t]he rock comes to bear and rest and so first becomes rock; metal comes to glitter and shimmer, colors to glow, tones to sing, the word to say.’47 In the Parthenon, blocks of marble are erected against the downward pull of gravity, creating a place for worship on the highest point on top of the city, close to the sky. The Acropolis is a built manifestation of human dwelling on Earth, and in this gesture ‘[t]he work lets the earth be an earth.’48

As a coming-to-presentation of being, the work of architecture is never isolated but always part of a context. Physical matter is articulated on a specific location at a specific time in accordance with material properties and static and tectonic principles in order to create space for human inhabitation on this earth. A work of architecture is never defined by just pure perception or formal elements, rather it always belongs to a specific place in time and space. To Gadamer, a work of architecture extends beyond itself in two ways, ‘as much determined by the aim it is to serve as by the place it is to take up in a total spatial context.’49 By adding something new that fulfils a purpose in a town or in a landscape, the building presents an increase in being and thus it becomes a work of art. If, on the other hand, the building is separated from the use and the place, it loses its meaning and becomes a vague shadow of itself.

However, in a rapidly changing reality, physical matter as well as use and place change all the time. John Ruskin points out that ‘imperfection is in some sort essential to all that we know of life. It is the sign of life in a mortal body, that is to say, of a state of progress and change.’50 To Ruskin, original material, traces of craftsmen’s tool and the result of wear and weathering is what gives the building character. In fact, ‘in all things that live there are certain irregularities and deficiencies which are not only signs of life, but sources of beauty.’51 Similarly, the Danish architect Johannes Exner understands buildings as living organisms, ‘[t]hey are born, they get ill, they are cured, they grow old, they die.’52 The identity of the work of architecture is not just defined by its condition at birth but also conditioned by the physical effects of weathering and changes caused by alterations during a lifetime.

Just as physical matter changes, so does use. In fact, the only thing architects can be sure of is that functions change. Describing what happens after buildings are built, the American writer Steward Brand argues that ‘[a]n adaptive building has to allow slippage between the differently-paced systems of the Site, Structure, Skin, Services, Space plan and Stuff. Otherwise the slow systems block the flow of the quick ones, and the quick ones tear up the old ones with their constant changes.’53 If a structure is planned for a specific programme, it will most likely be demolished when functions inevitably change. According to Brand, rather than planning for a fixed program, ‘scenario planning’ must allow room for an unknown future if buildings should be built to last. Similarly, the context of a work of architecture is in a constant process of change. The Danish landscape architect Sven-Ingvar Andersson describes significant landscape relations in a Bruegel painting as ‘in the centre’, ‘on top of’, ‘in middle of’, ‘at the edge’, ‘at the bottom’, ‘inside’ and ‘in a niche’.54 According to Andersson, the whole reason we may say that a building rests beautifully in the landscape is that we understand it in relation to its surroundings. However, just as the building in itself is always changing, so are the surroundings. According to Perez de Arce, this constant transformation is not a problem as towns need permanence as much as they need transformation, pointing out that change balanced with permanence is a quality to buildings and cities.55 In this perspective, it is not only the experience of the work of

architecture that is new for each coming-to-presentation, it is also the context to which the work is related that is changing all the time. The work of architecture is in itself constantly changing with regard to physical matter, use and place, just as it is continuously coming to presentation through the perceiver.

In the coming-to-presentation, something that was not there before presents itself as something: a world is set up. And when the presented work of art is clear to us, we understand it. Heidegger points out that the German word for space (Raum) has its etymological origin in clearing.56 The word clearing (Lichtung) means making light, which at the same time is making space within a boundary, i.e. to make place for the light to come in and making clear, i.e. to shed a light on something. Referring to Plato, Gadamer points out that ‘[t]he beautiful is of itself truly “most radiant” (to ekphanestaton),’57 arguing that the beautiful is something that emerges as ‘one out of a whole’. In this perspective, the work of architecture is the clear coming-to-presentation of a complex content in an ever-changing reality.