DALLAS BAR ASSOCIATION

Celebrating 150 years of service to the Dallas legal community.

ASSOCIATION

2101 Ross Avenue

Dallas, Texas 75201

Phone: (214) 220-7400

Fax: (214) 220-7465

Website: www.dallasbar.org

Established 1873

The DBA’s purpose is to serve and support the legal profession in Dallas and to promote good relations among lawyers, the judiciary, and the community.

DBA 2023 OFFICERS

President: Cheryl Camin Murray

President-Elect: Bill Mateja

First Vice President: Vicki D. Blanton

Second Vice President: Jonathan Childers

Secretary-Treasurer: Kandace Walter

Immediate Past President: Krisi Kastl

MAGAZINE STAFF

Executive Director: Alicia Hernandez

Editor in Chief: Jessica D. Smith

Executive Assistant: Elizabeth Hayden

Advertising: Annette Planey, Jessica Smith

Design: Page One Enterprises of Texas

Copyright Dallas Bar Association 2023. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any portion of this publication is allowed without written permission from publisher.

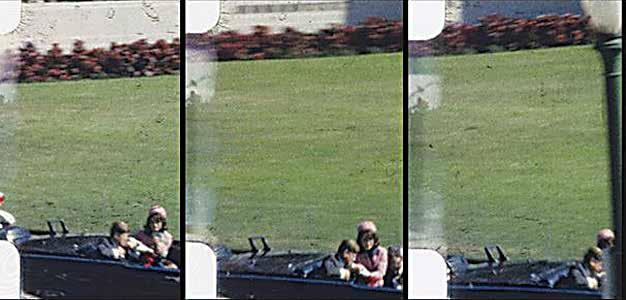

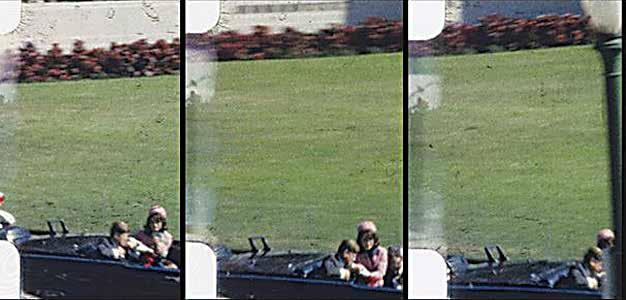

katten.com Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP 2121 North Pearl Street | Suite 1100 | Dallas, Texas 75201-2591 Century City | Charlotte | ChiCago | Dallas | los angeles | new york | orange County | shanghai | washington, DC | lonDon: katten MuChin rosenMan uk llP | attorney aDvertising Katten is proud to celebrate the Dallas Bar Association’s 150th anniversary and congratulates them on 150 years of serving the Dallas legal profession! • Corporate and Transactional • Tax • Insolvency and Restructuring Our Dallas office showcases a diverse team of attorneys who represent clients across a broad range of industries in the following areas: • Health Care • Real Estate • Litigation Cheryl Camin Murray Partner Health Care Dallas Office +1.214.765.3626 cheryl.murray@katten.com Mark S. Solomon Managing Partner, Dallas Corporate Dallas Office +1.214.765.3605 mark.solomon@katten.com For more information, contact: CONTENTS Past Presidents Reminisce 8 Timeline: A History of the Dallas Bar Association 32 Changing the Face of the Dallas Legal Community: the Sarah T. Hughes Diversity Scholarship 38 The Dallas Bar and the Allied Bars: A Collaborative Model 42 2020 and 2021: The DBA Meets the Pandemic 49 The Story of Passman & Jones and the Zapruder Film 54 The DBA’s Diversity Efforts & Accomplishments Over 150 Years 51

BAR

DALLAS

24 46 58

Let’s Celebrate 150 Years of the Dallas Bar Association!

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the very special, limited-edition magazine commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Dallas Bar Association (DBA). The DBA is over 11,500 members strong and has some of the best programs, events, activities, and benefits in the country.

In 1873, the DBA was founded by approximately 40 lawyers, who held regular meetings in the Oriental Hotel. At this time, the population of Dallas was between 4,000 and 7,000 people, which is less than the total number of attorney members of the DBA today. The Dallas Bar has a rich history, which you will learn more about in this commemorative publication. We have come a long way.

Throughout our nation’s history, many of our greatest leaders have been lawyers.

We, as attorneys, are fortunate to have a precious legal education that teaches us a unique way to think and analyze matters, as well as to advocate and speak up for others. One of the main rewards of a legal career is the ability to have a dramatic impact for the benefit of our clients, as well as citizens in our community. The Dallas Bar Association has so much to offer to its members, including exceptional opportunities to sharpen legal skills and make a difference.

Currently, the DBA proudly hosts virtual, hybrid, and in-person educational and hot topic programs that are geared toward not only attorneys, but also members of the public. In addition, we provide leadership academies, wellness programs, mental health resources, pro bono opportunities (through the Dallas Volunteer Attorney Program), diversity initiatives, professional development programs, practice-specific CLEs, networking happy hours, mock trial competitions, golf tournaments, holiday parties, discounted access to sports and art events, award ceremonies, musical performances, and international trips. This is all due to the diligent work of our DBA lawyer leaders, vendor partners, and the incredible professionals who work for the Dallas Bar Association under the guidance of their outstanding leader, DBA Executive Director Alicia Hernandez.

Let us not forget our wonderful home, the

Arts District Mansion, and our catering partner, Culinaire International, led by its talented General Manager, Kevin Brant, and his outstanding team.

As you may have heard, we are hosting an epic 150th anniversary celebration on the evening of September 9, 2023, at the Arts District Mansion. We have changed the date. We were so excited about this party that we had to move it up a month— please mark your calendar!

We have an amazing 150th Anniversary Committee Co-Chaired by Stephanie Gause Culpepper , Senior Managing Counsel at Lument, and Sarah Rogers , Partner at Thompson Coe, who are organizing special activities, as well as this monumental birthday party. I appreciate their leadership as well as the extremely hard work of Jessica Smith , DBA Communications and Media Director, for helping to promote the 150th anniversary, as well as develop this special edition magazine.

The Dallas Bar Association is fortunate to have an extremely strong Board comprised of talented lawyers. This is due in large part to our remarkable kinship with our Allied Bars: the Dallas Asian American Bar Association, Dallas Association of Young Lawyers, Dallas Hispanic Bar Association, Dallas LGBT Bar Association, Dallas Women Lawyers Association, and J.L. Turner Legal Association—whose Presidents and Presidents-elects all serve on our DBA Board of Directors. Thanks to them, our Board is stronger and able to make fiduciary decisions through an incredible array of perspectives, and we are very appreciative of them.

If you are not active in the Dallas Bar, I encourage you to get involved. The opportunities are endless. The DBA provides many ways for you to make a beneficial mark for the common good, and I promise that you will be rewarded with friendships and memories that will last a lifetime. The Dallas Bar has impacted so many lives throughout the years. We look forward to making a positive difference for the next 150 years, and with your ideas, involvement, and support the sky is the limit.

With much appreciation,

Cheryl Camin Murray, 2023 DBA President

2 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

State and Federal Criminal Defense and White Collar Barry Sorrels bjs@sorrelsola.com Stephanie Luce Ola steph@sorrelsola.com 214-774-2424 sorrelsola.com

The Ties That Bind Us

by Alicia Hernandez

In 2020, when life as we knew it stopped and we collectively hit the reset button, I wondered what the Dallas Bar Association (DBA) did a century ago when we experienced two world wars with a global pandemic sandwiched in between. This led me to our historical records and a review of SMU Professor Emeritus Darwin Payne’s outstanding book As Old As Dallas Itself, A History of Lawyers of Dallas, the Dallas Bar Associations, and the City They Helped Build. What I learned is that we share many of the same expectations of the legal profession and justice system as our predecessors of the last 150 years, and they laid the stepping stones that guided us to where we are today.

As we ventured into the Dallas Bar Association’s 150th anniversary, I revisited the material from a different perspective. Now, I was wondering how our future lawyers of the year 2173—150 years from now—would view us. Would those future lawyers be proud, embarrassed, wonder “what were they thinking?” Or, would they, like me, be mindful of the mistakes, appreciative of the attempts to improve, and amazed that we share many of the same principles despite the changing times.

The ties that bind us to our predecessors are a commitment to justice, education, the rule of law, community, and working towards a better bar. We didn’t always get it right the first time (and sometimes the second), but the hard work of our members and their strong commitment to our ideals led our Association forward to where we are today.

Access to Justice

The Dallas Bar Association started its first legal

clinic on July 1, 1924. DBA President W. R. Harris appointed a three-person committee to study the clinic. Once approved, the Bar raised money to support the clinic, and appointed one of the DBA’s few women members, Hattie Henenberg, as its attorney. In 1956, DBA President Dwight L. Simmons appointed a committee to further improve legal aid, and the Dallas Legal Aid Society became a reality in 1957. Fast forward to the 1980s when Legal Aid created a pro bono program that was the predecessor of the Dallas Volunteer Attorney Program, the joint pro bono program of the DBA and Legal Aid of NorthWest Texas. The DBA and Legal Aid also developed a partnership that has raised nearly $18 million to support legal aid to the poor in Dallas since 1998.

Scores of Dallas attorneys have volunteered through DVAP, carrying and passing the baton forward, in our efforts to provide legal aid to the less fortunate in our community. There are too many to mention here, but a few shining stars come to mind, including Lois Bacon, one of the first female attorneys in the Dallas City Attorney’s office, who volunteered full time at DVAP for decades during her

retirement. And, Ken Fuller, who not only helped many, many clients, but also provided unmatched mentorship and support to DVAP and the attorneys of Legal Aid of NorthWest Texas. Both are gone now, but they ran the distance and passed the baton. The work continues.

What started as an idea in 1924 blossomed into a movement, with many lawyers and bar leaders getting behind access to justice. But, maybe no one has said it as well as Past President Ike Vanden Eykel when he repeated many, many times “it is the best thing we do.”

Education

It is no surprise to say that the DBA is committed to educating lawyers with its 400-plus CLE programs per year. But, did you know that the DBA was instrumental in launching SMU Law School? In 1925, Joseph E. Cockrell, a past DBA President and trustee of Southern Methodist University, encouraged then SMU President C.C. Seligman to start a law school. Seligman asked the Trustees to authorize a law school, and they agreed as long as funding was secured outside SMU. Within days, DBA President Charles D. Turner appointed a committee to assist with establishing the school and raising the money to pay for it. DBA members stepped up to cover the salaries of two full-time faculty members for the first two years. In what might be the fastest creation of a law school ever, classes started a few months later in the Fall of 1925.

Since 1981, Dallas Bar members have supported legal education, as well as access to that education through the Dallas Bar Foundation’s Sarah T. Hughes Diversity Scholarship, now

available at all three Dallas area law schools. While we, as an organization, did not have such a critical role in the formation of UNT Dallas College of Law or Texas A&M Law School, the DBA and its members are steadfast supporters. And don’t forget all the DBA’s great programs in elementary, middle, and high schools, including lawyers in the classroom, Mock Trial, and the Summer Law Intern Program—all programs the DBA has been committed to for decades and that are still going strong. All are a demonstration of our love and respect for the law and our understanding of its importance to our society.

The Rule of Law and Right to Counsel

On March 6, 1931, the DBA Executive Committee called a special meeting to discuss the kidnapping of DBA member George Clifton Edwards. The day before, Mr. Edwards and two clients were abducted, tied up, and taken to a remote area of Dallas. While Edwards was released with a verbal “warning” not to “defend these clients,” the clients were taken to a more remote part of Dallas where they were whipped and abandoned. The DBA Executive Committee issued the following resolution:

“It is not only Mr. Edwards’ right to defend an individual charged with the violation of the criminal law, but it is duty to do so… this Committee views with alarm and condemns without reservation the conduct upon the part of those individuals responsible for the abduction…and it severely condemns the breakdown in respect of the law evidenced by the abduction and calls upon all good citizens and all

continued on page 64

4 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Progress is Not the Final Destination

by Kim Askew and Al Ellis

“When I become an old lawyer and can no longer stand before the Bar, I will tell all who will listen not to forget the lessons of history.” –Judge Louis Arthur Bedford, Jr.

The Dallas Bar Association (DBA) proudly celebrates its 150th Anniversary. It is well established as one of the leading bar associations in the United States, having made unparalleled contributions to the legal profession and our community. The DBA leads, innovates, supports, and lifts its lawyers and the public. From its education and public service programming to the administration of justice to tackling issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), the DBA has set the pace for achievement at all levels.

On this anniversary, we pause to reflect on some of our progress and achievements as a Bar on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. One who taught many of us about the DBA and law practice in Dallas was Judge Louis Arthur (L.A.) Bedford, Jr., a legal legend in our community. We have worked on DEI in the DBA for years and Judge Bedford often guided our work. He inspired us. He encouraged the DBA to examine its membership, leadership, and programs because he had experienced the DBA at its worst—when it lacked diversity, inclusion, and equity. Judge Bedford had been denied admission to the DBA based solely on his race. After years of denial, he was admitted to the DBA in 1964, and served the Bar for decades, including on the DBA and Dallas Bar Foundation Boards.

After the DBA opened its doors, Judge Bedford fully embraced the DBA and worked to ensure all

lawyers, especially lawyers of color, understood the history of the Bar and the histories and experiences of lawyers who fought to open the DBA doors and legal practice in Dallas— whether in courthouses, corporations, or law firms. Judge Bedford taught us that the DBA could not be the “home” of the Bar if all lawyers were not welcome in the Bar.

In describing his work and many achievements, Judge Bedford emphasized “progress is not the destination.” For Judge Bedford, our work in law was a journey. Our collective journeys lead to progress, which frequently takes us to new destinations. Judge Bedford opened doors, took down barriers, and made many contributions, but he made sure we understood these were steps along the way to the destination of equality and justice.

In Fall 2022, for the first time, Dallas ISD students walked through the doors of the Judge Louis A. Bedford, Jr. Law Academy, a moment that honored an iconic lawyer and judge who had contributed much to our Bar and community. The DBA was proud on that day and affirmed its journey to the final destination—-making our Bar a truly inclusive one.

As we move to the future, we offer some reflections from DBA members who continue to work on DEI in the Bar.

Kevin B. Wiggins Partner, White & Wiggins, LLP

L. A. Bedford was impressive and wise and wanted to be sure lawyers like me, and others who joined major firms at the time, understood and had an appreciation for the history of African

American attorneys in Dallas who had helped to create the opportunities we were being afforded. Judge Bedford spoke of indignities and insults he had endured from both the bench and bar, but he always moved forward with brilliance, dignity, and grace; characteristics largely honed in the fires of the Jim Crow South. Judge Bedford generously shared his time and recounted his life stories which gave us a sense of the challenges before us. Our task as African American lawyers was to take up the mantel his generation had left us and to teach those who will come after us to engage the courts, our lawmakers, and the country to make progress on the foundational principles his generation and those who came before him had laid. That we must march on ’til victory is won. We continue that journey today.

CeCe Cox

Chief Executive Officer, My Resource Center

Commitment to inclusion, diversity, equity, and access (IDEA) is a journey of learning, listening, re-learning, and action. In 2021, the DBA officially recognized the Dallas LGBT Bar Association with a Board seat. As a member of that organization, I was proud of my colleagues who had persevered. I also was chagrined it had taken 23+ years for the DBA to grant that recognition. Many lessons were learned along the way, as they have been with the inclusion of other bar associations over the years, and my wish is we all continue to open our minds and hearts in a commitment to IDEA so all members of our noble profession can work and serve others without discrimination and bias.

Wei Wei

Jeang Member, Grable Martin

The Dallas Asian American Bar Association (DAABA) was established with about 15 lawyers in 1985. Although it is hard to imagine now, when DBA President Hon. Robert Jordan, and DAABA President Suzy Fulton, sought to secure a seat on the DBA Board for DAABA in 1999, it faced opposition from some in DBA leadership. Today, DAABA boasts over 350 dues-paying members who are active participants of the local legal community, including judges and attorneys who practice law in-house, in law firms, and in the public/government sector.

Rob

Crain Partner, Crain Brogdon LLP

In 2017 the DBA partnered with local pastor Richie Butler and Project Unity to create Together We Dine, a program that connects people with trained facilitators to discuss race and other differences over a meal. DBA lawyers served as the original facilitators, and many continue to do so today. Six years later, thousands of people have participated in these virtual and in-person events. It has been humbling to watch DBA lawyers bring positivity to discussions about which so many are fearful. This is the DBA at its best—working to better our community one conversation at a time.

Regina Montoya CEO and Chair, Regina T. Montoya, PLLC

The DBA has been built by trailblazers like Judge Sarah T. Hughes, Adelfa Callejo, Harriet Miers,

6 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Rhonda Hunter, and Laura Benitez Geisler. They were among “firsts” who helped pave the way for countless women attorneys to navigate the legal field. I witnessed Judge Hughes, for whom the Dallas Bar Foundation’s Diversity Scholarship is named, encourage women to be active in the DBA and to lead the charge for equity and inclusion. She recognized that one must be a force to eliminate systemic barriers to the success of women and lawyers of color. Her advice was always to sit at the table where the decisions are made. The DBA has benefited and grown from listening and acting upon the advice of such diverse voices.

Meyling Ly-Ortiz

Managing Counsel, Toyota

While I have yet to see a Dallas Bar President who looks like me, I am hopeful.

I am hopeful because in recent years, I have seen the intentional inclusion of women, of those who are LGBTQ+, and others from historically marginalized communities in leadership and not just on committees. I am hopeful because of how recent presidents, like Rob Crain, have made it their personal mission to be inclusive and welcoming—not just in the Bar, but in the community. At the same time, let me be clear that hope is not enough. It is continued intentional actions, like the ones above, that will continue to carry the Bar forward, together.

Dena DeNooyer Stroh General Counsel, North Texas Tollway Authority

The Dallas Women Lawyers Association’s (DWLA) path to leadership in the DBA demonstrates how the DBA has grappled with change

though ultimately making decisions that advance the Bar and profession. For years, DWLA had no representation on the DBA Board though it sought to be in governance. Indeed, at times, DWLA’s own leadership had been divided on the issue. I was DWLA President in 2017 when the DBA unanimously approved a voting seat for DWLA. That step helped to ensure the voices of women lawyers would be represented in the governance of the Bar. I am proud the DBA took this step, and it reaffirmed my genuine appreciation for lawyers and their work. The DBA must continue to be nimble in addressing future issues that open the Bar to all.

Stronger Together

The reflections of these Bar leaders demonstrate just how the DBA continues to address tough legal and societal issues as it works to build

a stronger and more inclusive Bar. The Bar has relied on the strength of its diverse members and their collective journeys to make sound and often innovative decisions that guide and set the standards for our profession and community.

Moments on the journey have been fraught with difficulties, but our collective journeys are instructive and healing. Judge Bedford was aware of just how hard the journey to full equality and justice would be, but his example will continue to guide us—progress is important, but we must keep moving to the final destination.

Kim J. Askew is a Partner at DLA Piper LLP and a long-time supporter of the DBA. The DBA has an award named in her honor: the Kim Askew Distinguished Service Award. Al Ellis is Of Counsel at Sommerman, McCaffity, Quesada & Geisler, L.L.P. He was DBA President in 1990, and has a DBA award named in his honor: the Al Ellis Community Involvement Award. They can be reached at kim.askew@ dlapiper.com and al@textrial.com, respectively.

to the Dallas Bar Association for 150 Years of championing the legal profession and our community.

Hon. Elizabeth Lang-Miers

Dallas Bar Association President, 1998

Proud to lead the DBA during the celebration of its 125th year.

7 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

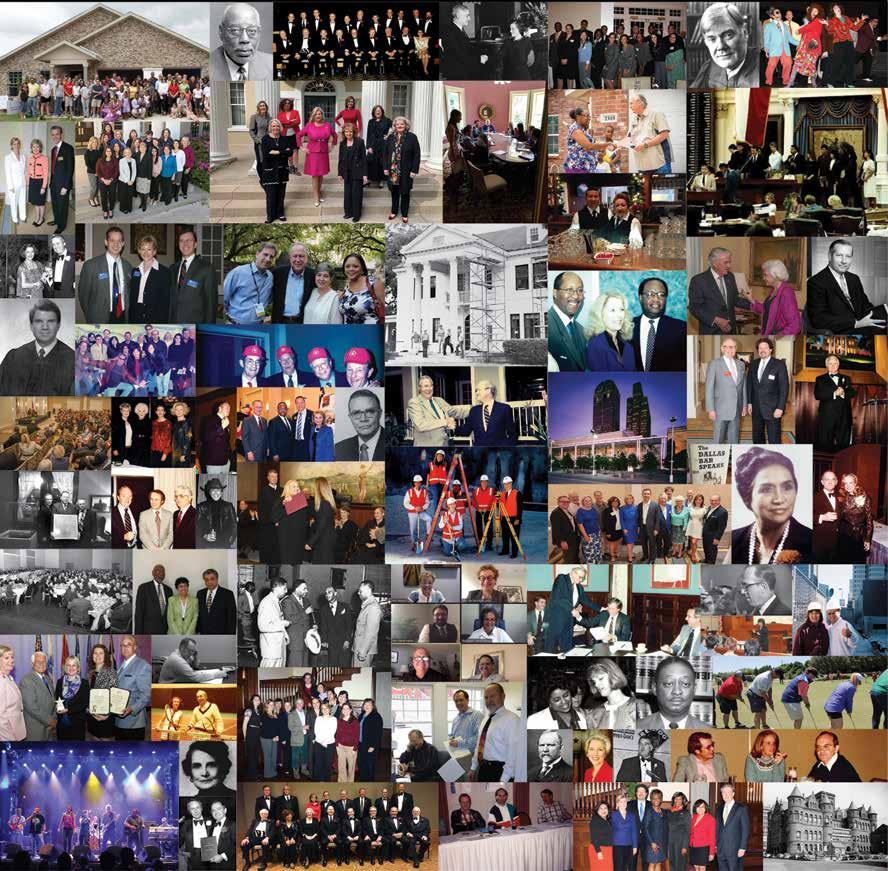

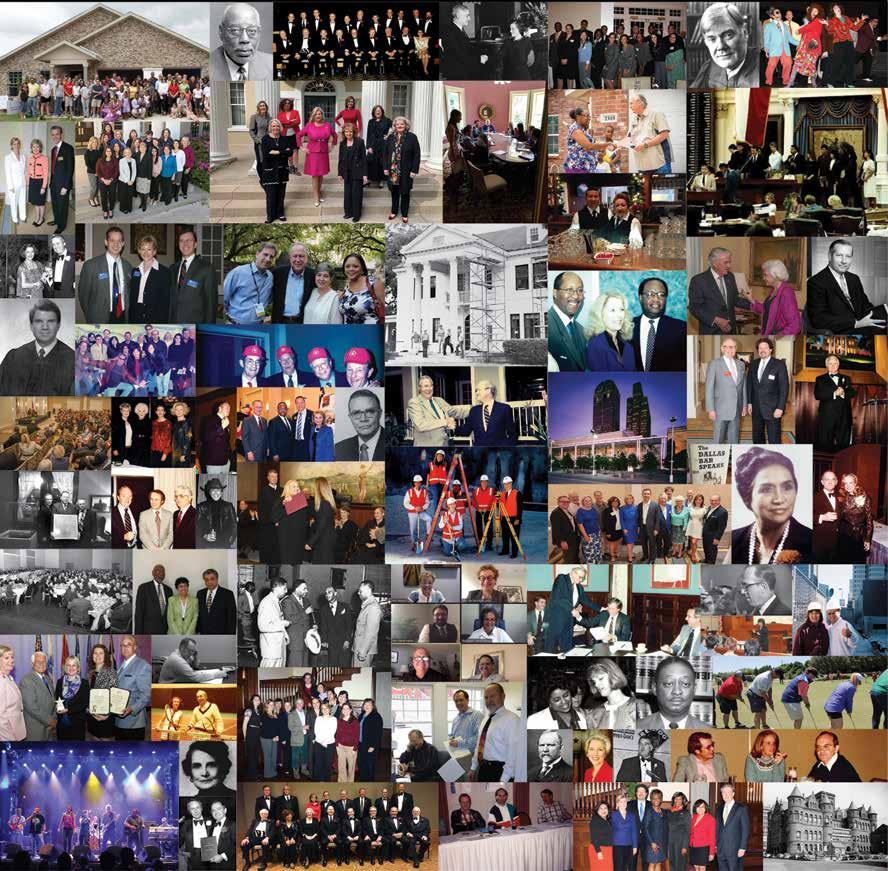

DBA Past Presidents Reminisce

The Dallas Bar Association’s Past Presidents have always been—and still are—a very supportive group. The DBA would not be the same without their hard work, encouragement, and wisdom. Here are a few highlights of their years as DBA President.

Louis Weber, Jr., 1974

My year as President was the happiest year of my career surrounded by professionals like JoAnna Moreland, Betty Bond, Cathy Maher, and a dedicated Board of true community servants. At that time, the practice of law was still based on a lawyer’s word and a handshake. I absolutely loved being President and wish everyone could have the experience.

Jerry Lastelick, 1983

In 1983, we had the memorable experience of the changes in the Dallas County Law Library. Common belief was that the Library was operated by the County, but in fact a District Judge was in charge, hiring personnel, taking trips to Library conventions with library personnel without authorization from anyone, and exercising sole control over the $600,000 Library account. After public hearings, this situation was rectified. Also, I started the dues checkoff for contributions to the Dallas Bar Foundation.

Harriet Miers, 1985

One of the most memorable experiences about my year 1985, was the privilege of working with the lawyers of Dallas and alongside then District Attorney Henry Wade to convince the County Commissioners Court to support building a Criminal Courts Building that would be properly sized for growth. The proposal in the originally contemplated Bond Package provided for a building that

was estimated to be fully utilized at its opening with no size to accommodate future growth. The battle was public and heated until a compromise was reached to allow the public to vote on both the original plan and an additional second plan that would provide an increase in the size of the Courthouse to allow for growth. Contrary to the warnings of naysayers, the voters overwhelmingly supported the increased amount of spending for a larger court building to accommodate growth.

Al Ellis, 1990 1990 began with an appearance by Elvis at my Inaugural and ended with a unanimous Board and Member vote to make the Presidents of the Minority Bars voting members of the DBA Board.

Peter Vogel, 1994

In 1993 I attended the Minority Participation Subcommittee chaired by Frank Stevenson and after the meeting I invited Frank to serve as the 1994 Chair of a new committee to get law firms to recruit high school students. Frank asked me why I wanted him to serve as the 1994 Chair, and I told him that he had auditioned for me in 1993 at the Subcommittee meeting, and my job as President in 1994 was to find future Bar leaders. Frank went on to become President of the Dallas Bar, State Bar of Texas, Chair of the Dallas Bar Foundation, and other great leadership positions!

Jim Burnham, 1996

When I was DBA President, the Dixie Chicks (now known as The Chicks) performed at my Inaugural. They were just starting to become famous. They were really sweet and kept calling me “Mr. Burnham,” as if I was someone special.

Molly Steele, 1997

Both my children are naturalized American citizens. As a consequence, I particularly cherished the times I got to welcome new citizens to our country at naturalization ceremonies held throughout my year as president. I was deeply honored to recognize the hard work and dedication of these immigrants with a dream of living in freedom. And to see our federal judges, whom I admired, welcome them with such sincerity and excitement made me know how fortunate I was to take part in these life-changing events.

Mark Shank, 2001

My most vivid memory is all the work we did on Mansion Expansion, particularly with regard to fundraising. I also recall that the 9/11 tragedy happened that year and was proud of how our Bar responded. Many will also remember that I also had a motto: “maximize cocktail opportunities.”

Nancy A. Thomas, 2002

During my year as DBA President, I was in charge of the construction of the Pavilion at the Mansion. It was a whirlwind of architects, engineers, contractors, and designers, many of whom we fired. Mark Shank and other leaders raised the money, and Cathy Maher and I very happily spent every penny. Rob Roby oversaw the entire project and did his best to keep us out of trouble. My favorite moment was when my dog drove my BMW Z3 convertible into the Big Hole.

Brian D. Melton, 2003

In 2003, all the great work of so many people culminated in the Grand Opening of The Pavilion. It truly was an opening of new doors for all of Dallas. We also honored the great Morris Harrell with the creation of the Morris Harrell Professionalism Committee

and an annual award in his honor. The first annual Education Symposium was also a highlight. The DBA was, and continues to be, the leading professional services organization in Dallas. Congrats on 150!

Rhonda Hunter, 2004

DBA celebrated 50 Years of Brown v. Board with a community Bell-Ringing ceremony, Reenactment of the oral argument, a curriculum which was taught to over 200,000 children, and a committee of young and seasoned leaders who thought of and implemented all of that and more. Of course, the inauguration was epic.

Mark K. Sales, 2006

Fun highlights were the DBA Board Retreat to Memphis, which included visits to the National Civil Rights Museum, Memphis Rock ‘N’ Soul Museum, Sun Records (birthplace of Rock ‘N’ Roll) and Graceland, as well as the first DBA Law Jam at the Granada Theatre with Dallas lawyer bands playing music to raise awareness and money for the DBA Equal Access to Justice programs.

Beverly Bell Godbey, 2007

Did you know that in 2007, for the very first time, every bar leader from the President of the American Bar Association, the President of the State Bar of Texas, the President of the Dallas Bar Association, and the President of each sister bar was a woman? Thanks so much to all of the DBA members and staff who made 2007 such a memorable year and who gave me the opportunity to serve the BEST BAR ASSOCIATION EVER.

Frank Stevenson, 2008

By 2008 I had been involved in DBA leadership

continued on page 63

8 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

When you have strong leaders, you have a strong community. The living DBA Past Presidents are proud to support the Dallas Bar Association and its 150th anniversary.

Louis Weber Jr. 1974

Jerry Lastelick 1983

Harriet Miers 1985

Vincent Perini 1986

George Chapman 1987

Al Ellis 1990

Douglas Lang 1991

Kenneth Mighell 1993

Peter Vogel 1994

Ralph “Red Dog” Jones 1995

Jim Burnham 1996

Molly Steele 1997

Elizabeth Lang-Miers 1998

Robert Jordan 1999

W. Mike Baggett 2000 Mark Shank 2001

Nancy Thomas 2002 Brian Melton 2003

Rhonda Hunter 2004

Timothy Mountz 2005

Mark Sales 2006

Beverly Godbey 2007

Frank Stevenson II 2008

Christina Melton Crain 2009

Ike Vanden Eykel 2010

Barry Sorrels 2011

Paul Stafford 2012

Sally Crawford 2013

Scott McElhaney 2014

Brad Weber 2015 Jerry Alexander 2016

Rob Crain 2017

Michael K. Hurst 2018

Laura Benitez Geisler 2019

Robert Tobey 2020

Aaron Tobin 2021

Louis Weber Jr. 1974

Jerry Lastelick 1983

Harriet Miers 1985

Vincent Perini 1986

George Chapman 1987

Al Ellis 1990

Douglas Lang 1991

Kenneth Mighell 1993

Peter Vogel 1994

Ralph “Red Dog” Jones 1995

Jim Burnham 1996

Molly Steele 1997

Elizabeth Lang-Miers 1998

Robert Jordan 1999

W. Mike Baggett 2000 Mark Shank 2001

Nancy Thomas 2002 Brian Melton 2003

Rhonda Hunter 2004

Timothy Mountz 2005

Mark Sales 2006

Beverly Godbey 2007

Frank Stevenson II 2008

Christina Melton Crain 2009

Ike Vanden Eykel 2010

Barry Sorrels 2011

Paul Stafford 2012

Sally Crawford 2013

Scott McElhaney 2014

Brad Weber 2015 Jerry Alexander 2016

Rob Crain 2017

Michael K. Hurst 2018

Laura Benitez Geisler 2019

Robert Tobey 2020

Aaron Tobin 2021

CELEBRATING

Krisi Kastl 2022

How “If” Changes to “When”

by Frank E. Stevenson II

A Dallas Bar Association program for at-risk students allowed me to mentor a young man beginning his freshman year at a Dallas ISD high school. I reflexively spoke to my mentee as I did my own son. “When you go to college, you’ll need this,” and “When you go to college, you’ll do that.” But during one of my “when-you-go-tocollege” conversations he placed his hand on my arm to stop me and after a few moments quietly said, “You need to understand something. You are the first person who ever acted like I was supposed to succeed.”

Without a single family member having ever finished high school and with his older brother in jail, my mentee had never heard “When you go to college.” He had barely heard “If you go to college.”

I had witlessly thought that the DBA program was intended for me and the other mentors to give those students study tips or writing advice or time-management skills or the like. But it actually wanted us to give those students something far more precious—namely, our confidence. And three and a half

years later, I watched that young man graduate in the top 10 percent of his class. “If” changed to “when” and the four scholarships he earned carried him to college that fall.

Sometimes all a person needs to succeed is for enough people to believe in him. And it is remarkable how often those people are placed and equipped to instill that confidence by the Dallas Bar Association.

Over its 150-year history, the Dallas Bar has offered its members unmatched opportunities for professional growth. But a far more estimable metric is how our Association has fitted its members to serve their community—especially those

who, if the topic of success is raised, at most hear “if” and never “when.”

Initially advanced by 1979 DBA President Jerry Buchmeyer, this year marks the 44th consecutive year the DBA has run its statewide High School Mock Trial program. Reaching over 300 Texas schools annually, more than 175,000 students have participated in this program since its inception. And, yes, the participants are taught procedure, rules of evidence, and all the rest. But what the program really teaches these young women and men is that they can be lawyers or anything else they want to be. Stated differently, it strives to change “if” to “when.”

The same is true for the DBA’s Law Related Education programs. Through separate grade-specific contests ranging from K to 12, over 100,000 Dallas ISD students have been asked to depict or explain the Rule of

Law via the graphic arts, photography, or written essay by the DBA’s Law Day Program. But only the most credulous could believe that is what this program is actually about. Attend the awards luncheon and watch the teachers applaud, the parents beam, the winners smile. You are watching “if” inch towards “when.”

And the DBA’s Law in the Schools and Community/Career Days Program— another Law Related Education initiative—places DBA lawyers in DISD schools. They teach those students the legal issues associated with WikiLeaks or anti-cyber bullying or their First Amendment rights—except, of course, they don’t. What they actually teach is that there are opportunities available to these young people they otherwise might never imagine—in essence, “if” can

continued on page 14

12 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

become “when.”

In 1993, DBA President-Elect Peter Vogel asked a guy he didn’t know from a pile of lumber to start a program during Peter’s year leading our Association. It was the Summer Law Intern Program, and I was that pile of lumber.

Since that time, the members of the Dallas Bar have given over 650 DISD students summer jobs in your law firms, agencies, and corporate offices. And the Summer Law Intern Program—or SLIP—won awards from the State Bar of Texas and the DISD, and was implemented by other bar associations following our example.

But the success of a program like SLIP is not measured by awards. Is it changing lives? Is it nudging “if” to “when”?

After the program was in place a few years, we asked one of its alumni to address precisely that question at our orientation event for the incoming interns. Her response supplied a clearer answer than we ever imagined. She asked if the event could be

live. Fortunately, because of the DBA Home Project, the longest-running, whole-house sponsor for Dallas Area Habitat for Humanity, 36 families will sleep tonight in homes we provided them.

For others, an unresolved and seemingly unresolvable legal need can be an impene-

Geisler’s legal incubator, Entrepreneurs in Community Lawyering, that equips lawyers to better address the everyday legal needs of everyday Americans.

And it is also hard to change “if” to “when” if we lack the ability to talk and relate to people different from

now than three decades ago. America is chin-deep in the gummy bilge of hopelessness. Fully 85 percent of us believe our country is headed in the wrong direction, according to an Associated Press/University of Chicago poll last summer. This places distinct imperatives on us as lawyers.

moved up a day so it would not conflict with her departure for Europe on her Marshall Scholarship.

Other outward-facing DBA programs may not seem overtly aimed at changing “if” to “when,” but in fact remove the barriers to that transformation becoming a reality. It is hard to believe in “when” if you lack a decent place to

trable barrier to “when.” The Dallas Bar responds with its Equal Access to Justice Campaign that has raised more than $18 million for legal-aid efforts to serve 70,000 families through the Dallas Vol-

ourselves. 2017 DBA President Rob Crain’s Together We Dine plays antidote to that by bringing together people of diverse backgrounds in a structured and positive setting to talk about things that matter. And there is also the manifest good accomplished by other outward-facing DBA programs—such as the Toy Collection Drive and Santa Brings a Suit.

We cannot be content to measure ourselves or this Association by only the contributions we make to our profession. We also must weigh the contributions made by our profession to our community at large— focusing not solely on the client who brings us his lavish retainer, but also on the evicted tenant, the at-risk student, and the underhoused family who bring us only their crushing need. Fortunately, when we give help, we invariably receive help. And more. When I consider the activities that made me most proud to be a lawyer, virtually all of them were “if”to-“when” opportunities supplied by the Bar.

unteer Attorney Program (DVAP); 1993 DBA President Ken Mighell’s LegalLine that has counseled and comforted thousands of our city’s least fortunate; 1948 DBA President Robert L. Dillard, Jr.’s Lawyer Referral Service that has helped over half a million people find the attorneys they badly needed; and 2019 DBA President Laura Benitez

Setting up SLIP exactly 30 years ago, I imagined I was in the business of providing summer employment or professional development instruction or the like. I wasn’t. Nor were any of the other DBA volunteers working on that or any of the other programs I have named. We all instead were in the Believing-In-People Business. We were placing our confidence in people famished for it. We were telling them “when” instead of “if”—maybe even for the first time. That is needed more desperately

By building houses, hiring interns, mentoring students, bringing clothing, teaching in schools, and supporting DVAP, we declare that none of this city’s homeless or hopeless, out-of-work, overlooked, or oppressed have to stay that way—“if” can become “when.” It is the DBA’s 150-year-old contribution to the Believing-In-People Business. I used to wonder if the Believing-In-People Business could even help change the entire world. Now I wonder if the world changes any other way.

14 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Frank E. Stevenson practices at Locke Lord LLP, served as 2008 DBA President, and is a Past President of the State Bar of Texas and the Western States Bar Conference. He can be reached at fstevenson@ lockelord.com.

When I consider the activities that made me most proud to be a lawyer, virtually all of them were “if”-to-“when” opportunities supplied by the Bar.

Gone are the Days…Yet

by Harriet Miers

Between 1970 when I became a lawyer, and 1985 when I served as President of the Dallas Bar Association, I had already seen many changes occur for women practicing law in Dallas and around the State. By that time, Dallas had many more women lawyers successfully engaged in differing aspects of the profession. During that same period, I had been encouraged by male colleagues, such as former Dallas Bar President John Estes, to join and stay involved in the activities of the Dallas Bar. Some of my early volunteer efforts with the Bar involved working with representatives of the education system in Texas to include law-focused learning in the baseline curriculum of public schools. As an example, that experience allowed me to work with dedicated, selfless lawyers—and it showed me how Bar work could be challenging, enriching, thoroughly enjoyable, as well as impactful for the profession and public.

Other women lawyers also were seeing the value of Bar work, and they were becoming more and more active in professional activities beyond just the practice of law. In those times, the additional responsibilities for many women lawyers included being the primary caregiver for children and often aging parents. Personal family care, in addition to developing a practice or otherwise working full time, was challenging even without engaging in other activities such as Bar work. As time passed, though, as should have been expected, women lawyers increasingly did seek to include Bar work and community service in their professional lives.

A Bar project, such as advancing law-focused education for young students in public schools, is just one example

of the broad range of Bar efforts that can be attractive to lawyers. The vast majority of lawyers seek to see how their law degree can have the most meaningful impact, in addition to using their license to earn a living. Being involved in the substantive law areas of bar associations, such as litigation or antitrust-focused sections, provided an opportunity for women lawyers, as well as their male counterparts, to learn and also have greater exposure to outstanding lawyers in many fields. Over time, more and more women lawyers sought the benefits of such activities and leadership roles in Committees and Sections. They recognized that being involved in these activities helped keep a lawyer on the horizons of the law, and enabled the development of highly important relationships in both personal and professional lives. Nonetheless, while extremely valuable, being involved in such activities created additional commitments and strain on already busy schedules—especially for women lawyers.

Time has passed now, and the profession has become much more diverse. The opportunities for women have greatly increased, including for those who represent the greater diversity that now exists in the makeup of the legal community. Women lawyers are represented in the halls of various legal and other educational institutions, law firms of all sizes, corporations, governmental offices across the spectrum from city to national, public interest organizations, community organizations, and advocacy

organizations of every description. Importantly, women are now also prominent in the Texas judiciary. As from the beginning, solo practice also remains an available choice. Additionally, women with law degrees can choose to enter any role in business, education, or community service using a law license as simply foundational, rather than as a requirement.

In those earlier days, unfortunately, women taking time off or working part time was sometimes interpreted as evidence of a lack of seriousness in a legal career. Attitudes in many quarters have evolved over time, and both men and women have sought ways to emphasize family responsibilities to a greater extent. This shift has been important in the recognition that accommodating family needs, values, and responsibilities helps create a better work environment and team approach, as well as helps lead to well-rounded lives for lawyers wherever they may be practicing.

While opportunities now abound for women lawyers, challenges remain for many who strive to effectively manage their practice or work in the legal arena and still carry their unique family responsibilities. While the ideal may be for family responsibilities to lie equally with both parents, practicality generally shows disproportionate responsibilities for women. Certainly, at this time, men do undertake more tasks related to child rearing, education, doctor visits, and involvement in their children’s participation in sports and other extracurricular activities. Employers and professional organizations offering opportunities to work part time or remotely are also instrumental in encouraging a robust professional life for those with family responsibilities.

As the professions have become more accommodating for women to have their professional lives and spend time in family endeavors, greater supportive facilities have developed. Day care facilities and options to allow for child care are more numerous. Even more are needed, though, particularly affordable ones. The greater awareness of the need to find workable schedules, structures, and accommodations for women with children, or helping with an aging family member, has led to more openness and understanding of the need to offer viable alternatives.

While gone are the days when women lawyers faced unacceptable hardships to seek a level playing field with equal opportunities to excel in the legal profession, challenges in the profession for women remain somewhat unique. The great development has been in increased efforts to recognize challenges many women lawyers face and the need to effectively address them. The legal profession is at its best when it allows for meaningful contribution by all those with an interest in being an excellent lawyer, without foreclosing on meeting family responsibilities. The focus on the needs of the legal profession to accommodate those who serve as primary caregivers should continue for the healthy growth of the legal profession and its ability to best serve the Nation and its people, communities, and businesses.

Harriet Miers , 1985 DBA President, is a Partner at Locke Lord. She was the first woman DBA President, the first woman hired at the Dallas Firm of Locke Purnell Boren Laney & Neely, and the first woman elected to Firm President. In addition to her many “firsts,” she also served in the administration of President George W. Bush from 2001-2007. She can be reached at hmiers@lockelord.com.

18 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Dallas’ African-American Lawyers: A Rich and Vibrant History

by Rhonda Hunter

by Rhonda Hunter

You could hear a pin drop. The huge ballroom was filled to the brim with those who had come to witness the inauguration of the first African American President in the 131-year history of the Dallas Bar Association. “We are the lawyers. We are the arbiters of justice. We are the ones people come to first.” The year was 2004. The speaker and newly elected President was me, Rhonda Hunter.

On this occasion especially, lawyers that shaped Dallas and created the path that led to my ascension to the presidency were top of mind. A daunting past and awesome reminder of how legacies are built through generations of perseverance and diligent work.

J.L. Turner is recognized as the first African American lawyer to remain in practice in Dallas due to his legacy of longevity from 1898 to 1951. Turner practiced for a time with Joseph E. Wylie, who had started a practice in Dallas in 1885. It would be early in the 21st century before scholars Darwin Payne, John Browning, and Hon. Carolyn Wright Sanders would recover evidence that more lawyers of African American descent had a presence in Dallas before the turn of the century.

In 1882, J. H. Williams petitioned to become a lawyer after “reading the law” and working under the tutelage of a Dallas lawyer. He was denied a license to practice in December 1882. Later in the 21st century, Williams would be posthumously admitted to the Texas Bar after a review of the evidence regarding his application by

modern lawyers.

Earlier in 1882, Samuel Scott, a licensed attorney, came to Dallas to practice, but left within six months after what the Dallas Herald described as a “slight prejudice against him on account of his race.” He would later become one of Arkansas’ first Blackelected state legislators.

The inability to gain traction in the legal profession in Dallas would transcend centuries as over 100 years later, young lawyers would leave Dallas after being unable to find law firm employment. Several would become successful leaders in other states, including Aaron Ford, who now serves as the Attorney General for the State of Nevada, and Berna Rhodes Ford, now Legal Counsel for Nevada State College. Recognizing leaders before they traversed and succeeded elsewhere would become a recurring issue for Dallas lawyers.

W. J. Durham, who studied the law and passed the bar in 1926, had faced the burning of his law office in Sherman in 1930. Durham moved his law office to Dallas in 1944 and partnered with young C. B. Bunkley, who earned his University of Michigan law degree in 1944. By the 1950s, housing was at a premium and African Americans buying properties in previously all-white Dallas neighborhoods faced a rash of bombings intended to discourage expansion of middleclass Blacks into these areas. Durham was

instrumental in representing the community in efforts to stop the bombings.

Both Durham and Bunkley gained recognition and respect as lawyers who, in addition to their daily practice of civil, criminal, and probate cases, worked on Dallas housing, education, and civil liberties cases with the future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall. They served as lawyers on landmark cases such as Sweatt v. Painter (1950), and Borders v. Rippy (1955), the first Dallas school desegregation case.

L. A. Bedford left Dallas as a young man and traveled to bustling New York City to attend Brooklyn Law School before returning to Dallas in 1951 to be mentored by Durham and Bunkley. About this time, L. Clifford Davis returned to Fort Worth after matriculating at Howard University Law School. Davis would travel from Fort Worth to Dallas for meetings and comradery with his legal contemporaries, as there were no other Black lawyers in Fort Worth in the early 1950s.

Twelve Dallas lawyers formalized these gatherings of Black attorneys in 1952, by forming the Barristers Club. Four years later, the club’s name was changed to the J.L. Turner Legal Society in honor of the elder statesman and mentor attorney, J. L. Turner, Sr. Turner practiced for five decades, making him the longest-practicing Black attorney in Dallas by the time of his death in 1951. His son, attorney J.L. Turner, Jr., served as President of the group in its first years of operation, and the Association has produced presidents who have become Dallas’ leaders over the

course of the 70 years since its formation.

W. J. Durham and C. B. Bunkley applied for membership in the Dallas Bar Association in the early 1960s. The applications of Durham and Bunkley were not acted on at that time. While they were never officially turned down for membership, they were not accepted either. Durham was asked to reapply in 1968. He refused, as did Bunkley. In 2006, the Dallas Bar admitted Durham and Bunkley posthumously, as DBA members.

By 1963, Fred Finch, a Harvard-educated Dallas attorney with roots in East Texas, became the first African American member of the Dallas Bar. Late in his career and decades after opening his office on Oakland Avenue, Mr. Finch—a probate and civil rights attorney who also published a local newspaper—hired a young law student to clerk in his practice. That law student would later become the first African American President of the Dallas Bar Association.

The first person of color to join the Dallas Bar Board of Directors in 1984 was Louis A. (L.A.) Bedford. Bedford had become the first African American judge in Dallas County in 1966. Bedford would mentor every African American attorney to grace the doors of his office on Forest Avenue, including Joan Tarpley, who was the first African American female to open a practice in Dallas County in 1968 and the first African American female judge in Dallas County in 1975; and Joseph E. Lockridge, who in 1966, became Dallas’ first Black state representative since reconstruction.

continued on page 64

20 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Insurance against insurers.

IS YOUR COMPANY PROTECTED AGAINST INSURERS?

Clients trust us to help them navigate insurance policies, communicate with insurers, negotiate claims, and litigate disputes. Whether you have a simple question or a serious dispute, you can count on our team for straight talk, smart solutions, and tenacious advocacy.

Former DBA President Beverly B. Godbey and the rest of the Amy Stewart Law team congratulate and thank the DBA for 150 years of excellence.

NEGOTIATION | LITIGATION | CONSULTATION | 214 233 7076 | amystewartlaw.com | Dallas, TX

Becoming Part of the DBA Community

by Laura Benitez Geisler

I recall feeling like an outsider the first time I walked into the DBA as a first-year law student. Surrounded by members of a profession I longed to join; I didn’t see any that looked like me. It is not surprising since at that time, there were only 202 Hispanic lawyers in all of Dallas County and only 707 female Hispanic lawyers in the entire State of Texas, according to the State Bar of Texas Department of Research and Analysis. I was still struggling to see myself as a lawyer, but the sense of community I felt that day inside the DBA community made me want to go back, because for the first time I could begin to see myself as a lawyer.

By the time I graduated from SMU in 1997, women and minorities were visible role models in our local bar associations. That year, the Dallas Association of Young Lawyers (DAYL) was led by its first Hispanic President, Joyce Marie-Garay, and Molly Steele was President of the Dallas Bar Association (the second woman to hold that position following Harriet Miers in 1985), with Liz Lang-Miers as President-Elect. Seeing women in these leadership positions was inspiring and their journeys undoubtedly helped pave the way for mine. But the person who most directly helped pave the way for me in bar leadership was Ralph C. “Red Dog” Jones. As a mentor and role model, Red Dog could not have been any more different than I was, but his influence on my professional career was profound.

A Past-President of the DAYL and the DBA, Red Dog hired me out of law school and encouraged me to apply for the inaugural DAYL Leadership Class. Given that I was awaiting my bar results

when I submitted my application, I have no doubt Red Dog pulled some strings to get me into the class. Through that experience I was led to explore various opportunities not only with DAYL, but also the Mexican American Bar Association (now known as the Dallas Hispanic Bar Association/DHBA) and the Dallas Women Lawyers Association (DWLA).

I first served on the DAYL Board of Directors in 2002 as the appointed liaison for the Mexican American Bar Association. Recognizing the opportunity to increase Hispanic representation on the DAYL Board, I decided to run for an elected position the following year so that the appointed position could go to another Hispanic lawyer. In 2003, while serving on the DAYL Board of Directors, I was elected to serve as President of the DWLA. My experiences and interactions during those formative years helped prepare me to serve as DAYL President in 2007 and eventually as DBA President in 2019.

Following my term as DAYL President, I successfully ran for a seat on the DBA Board of Directors in 2008. During my time on the DBA Board, I became increasingly sensitive to the fact that the DBA, founded in 1873 with a membership base of over 10,000 lawyers, had never elected a Hispanic to serve as President. It is not an easy path to the DBA Presidency. The leadership track is long and requires significant commitment. The first step involves getting elected to the DBA Board of

Directors (something that had not always been easy for minority lawyers). After serving on the Board, the next step typically involves running for Vice Chair of the Board of Directors, followed by a run for Chair of the Board (positions elected by Board members). Thereafter, the line of succession is voted on by the general membership and traditionally involves a term as Second Vice-President, First Vice-President, and President-Elect before assuming the role as DBA President.

My decision to pursue the DBA Presidency was not an easy one. At this point in my career I had already spent a significant amount of time in bar leadership, and while I enjoyed the work, I was start-

inspiration I needed to continue my path to the DBA Presidency. It was a humbling moment, accompanied by the recognition that it was not about me, but about setting an example for others to follow. Up until that point, I did not view myself as a role model or appreciate how my leadership roles could influence the way others viewed their own potential. It reminded me that whatever successes I had achieved came on the backs of those who proceeded me and reminded me that I had an obligation to do my part to make the path easier for others.

To have played a small role in DBA’s history is an honor. My year as DBA President was one of the most professionally rewarding expe-

ing to burn out and was not sure if I wanted to take on such the commitment—until a chance encounter with a young Hispanic law student. The student approached me following a Bar function and although we had never met, she wanted me to know that she viewed me as a role model. She described watching me from afar at several different events and explained that she had been looking for an opportunity to meet me. She described how seeing someone who looked like her gave her a sense of belonging and made her feel less like an outsider. I was immediately taken back to my first time at a Bar function, feeling like an outsider, surrounded by members of a profession I longed to join, but with none who looked like me.

The law student who saw herself in me became the

riences of my career, made possible by a community of Dallas lawyers from all walks of life who believed in and supported me—and for that I am forever grateful.

It was there that I found the role models and community that helped me grow personally and professionally, and supported me as I became the 110th President of the Dallas Bar Association—the “first” Hispanic in the history of the organization ever elected to serve in the role.

Laura Benitez Geisler , 2019 DBA President, is an attorney at Sommerman, McCaffity, Quesada & Geisler, L.L.P. In addition to her legal and community work, she served as Co-Chair for the 2014-2015 Equal Access to Justice Campaign benefitting DVAP, which raised over $1.1 million to provide pro bono legal services to low-income Dallas County residents.

22 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

To have played a small role in DBA’s history is an honor.

The History of the Arts District Mansion: Home of the Dallas Bar Association

by Rob Crain

Later this year, the Dallas Bar Association (DBA) will celebrate its 150th anniversary at the Arts District Mansion located at the intersection of Ross Avenue and Pearl Street. Though the DBA’s acquisition of the Mansion would not occur until 1977, the Association and its future home were birthed within a few years of one another.

In 1888, Nettie Ennis Belo, wife of Alfred Horatio (A.H.) Belo, a civil war veteran and publisher of the Dallas Morning News , bought a brown frame house at the corner of Ross and Pearl for $27,500 from Mrs. Belo’s “separate property and estate.” The site was part of a 10-acre tract which Captain W.H. Gaston, a pioneer Dallas banker, had bought several years earlier for $100 an acre. Ross Avenue became the first elegant address in Dallas and its first paved street between what is now Ervay Street and North Central Expressway.

Architect Herbert Miller Greene was commissioned by Nettie Belo to design a stately mansion at

Ross and Pearl patterned after the Belo family home in Salem, North Carolina. The contractor for the neo-classical revival home was Daniel Morgan, who, in 1893, completed the Dallas County Courthouse now known as “Old Red.”

Construction of the home was believed to have been completed about 1900. A.H. Belo died in 1901, having inhabited the home for less than a year. His son, Alfred Horatio Belo, Jr., succeeded his father as President of the Dallas Morning News until he died in 1906 at the age of 33 from meningitis. Nettie Ennis Belo lived in the home until her death in 1913 at the age of 67. Her daughter-in-law,

Helen Ponder Belo, eventually moved the remaining family members back to North Carolina in 1922.

In 1926, a 50-year lease was negotiated between Helen Belo Morrison (Nettie and A.H. Belo’s granddaughter), and the Loudermilk-Sparkman Funeral Home. The funeral home changed names over the years and hosted the funeral services of Dallas dignitaries and other wellknown persons, including the funeral of Clyde Barrow of “Bonnie and Clyde.”

On September 15, 1977, the Dallas Bar Association closed on the purchase of the Belo Mansion. A few days later the DBA closed on adjacent parcels of land; these parcels acted as a parking lot for many years and are now the sites of the Pavilion and underground parking garage.

In advance of my year as DBA President in 2017, I had the privilege of interviewing Jerry Jordan, Harriet Miers (1985 DBA President), Nick LaBranche (Building Engineer), Bob (1978 DBA President) and Gail Thomas, and several others to learn the history of the mansion

purchase. Cathy Maher, former Executive Director of the DBA, also collected history on the Belo Family and DBA headquarters which is included here.

The DBA was founded in 1873. The de facto headquarters of the Association rotated to the law office of the Association President for that year. In 1937, the Association secured a 15-foot cubicle under the stairs of the Old Red Courthouse. In 1955, Henry Strasburger was President of the DBA. He believed lawyers should have a regular meeting place. According to Bob Thomas, Henry felt so strongly about securing a location for lawyers to meet and socialize, he silenced any concerns about costs by personally advancing the first year’s rent for space in the Adolphus Hotel. He was right. Lawyers flocked to the new gathering place. Membership flourished, and by the 1970s the Association outgrew their space.

At the time, the Belo family home sat vacant. The Loudermilk-Sparkman Funeral Home had moved out of the mansion due to expansion of Pearl Street, but remained obligated under the lease agreement with Helen Belo Morrison. Mr. Sparkman hired the firm of Turner, Rodgers, Winn, Scurlock & Terry to help them find relief from the lease. Jerry Jordan was an attorney with the firm and also served at that time as Vice President of the DBA.

Jerry believed the home could be an option for the new headquarters. In 1976, at the Inauguration of incoming DBA President Waller Collie, Jr., Jerry was seated next to Gail Thomas, wife of

24 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Waller Collier and Bob Thomas

Bob Thomas. Gail is a person who gets things done. Jerry knew that if he could sell Gail on the idea of the Belo home as the Bar’s headquarters, “the battle was more than half won.” When hearing the suggestion, Gail recalls, “sparks went off, and it just felt like dynamite.”

That year’s Board of Directors’ retreat was at Tanglewood Lodge on Lake Texoma. The idea of the Belo family home as a headquarters was discussed. A group including Jerry, Bob, Gail, and Waller visited the mansion shortly thereafter. Jerry unlocked the door with Waller following him inside. All remember Waller taking his first steps inside the home and saying words to the effect of, “This is what a bar headquarters should look like!” Behind Waller and Bob’s leadership, momentum quickly

trip to North Carolina to meet with Ms. Morrison. The night before the trip, Bob and Gail dropped off their kids with Bob’s parents. When conversation turned to the reason for the

Morrison felt passionately about her childhood home. She wanted the home to go to caring people who would maintain its integrity for years to come.

When the DBA contingency met Ms. Morrison in her North Carolina home, initially things did not go well. The atmosphere was frosty until Bob remembered to tell Ms. Morrison “Hello” from his mother. Bob retold his mother’s account of the beautiful blue dress. Whatever chill was in the air quickly disappeared. Turns out, the dress was Ms. Morrison’s “favorite dress of all time.” Her parents had bought it for her in Paris. She also remembered Bob’s mother. In an instant, the DBA was family.

Estes, Jerry, Bob, and many others. Many of the rooms at the Mansion are named after firms who dug deep for the cause.

On the third Thursday in September 1977, the DBA exercised their option and closed on the purchase of the new headquarters. Hard work followed. Members worked weekends scraping layers of paint off the walls until the original colors were discovered. Detail was taken to return the home to its original condition. What is now Arts District Hall was a chapel erected by the funeral home for services. The DBA built an atrium to connect the home and chapel.

On August 1, 1979, opening ceremonies were held at the new DBA headquarters, and Helen Belo Morrison was present. She proclaimed the home was just as she remembered. She was proud. She donated portraits of her grandfather and father which hung for many years above the settees near the front door— benches where as young women, she and her sister would wait on their dates.

DBA membership expanded rapidly, as did functions at the Association’s headquarters. Jerry Jordan’s daughter, Jill, was the first to be married at the Mansion. After years of growth, the DBA set upon expanding the facilities, adding the Pavilion in 2003.

built behind the idea, but several hurdles remained. First, they had to convince Helen Belo Morrison to sell them the house in which she was born. Then they had to raise money to buy and refurbish the old home.

Overcoming the first challenge was aided by good luck. Bob and Gail, along with Waller and Elaine Collie, organized a

trip, Bob’s mother said to tell Ms. Morrison “Hello” for her. Bob stopped and asked, “You know Helen Belo [Morrison]?” She answered, “Yes, of course I do, I went to her 12th birthday party at the Belo Mansion…she wore a blue velvet dress with a white rose point lace collar, prettiest dress I ever saw.” This came in handy as Ms.

Shortly thereafter, the DBA secured an option to buy the property, but financing remained a significant obstacle. Some money had been raised for the proposed move to the First National Bank Building, but much more was needed to purchase and remodel the Mansion. Jerry and Bob made connections with Republic Bank, who provided financing. DBA members got to work raising funds, including Jerry Buchmeyer, Harriet Miers, John

From its opening in 1979 until recently, the headquarters was named the “Belo Mansion.” Though A.H. Belo died in 1901, and his family subsequently sold their interest in the Dallas Morning News in 1926 to A.H.’s trusted employee, George Bannerman Dealey, Mr. Dealey chose to honor his mentor by retaining the Belo name on the publishing company. Throughout the 20th century, the Belo name was associated with high

continued on page 62

25 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Nick LaBranche, Building Engineer, explains the building blueprints.

Members of the public line up to view the body of Clyde Barrow.

Memories

by Cathy Maher

In 1978, I was one of only four staff members at the DBA’s headquarters in the Adolphus Tower, located on the corner of Main and Akard in the heart of Downtown Dallas. By then, our Bar had grown to 3,400 members.

Thereafter, I served in a number of positions, including as DBA Executive Director from 1994 to 2016. Too many positive changes occurred in the DBA over the next 35-plus years to recount them all. The following are just a few notable achievements.

At the Adolphus office in 1978, operations were simple—no computers. Invitations for our only social event—the Inaugural—were tediously hand-addressed by staff. Dues statements were also prepared by hand. The inefficiency of hand-addressing mailers changed when the Bar purchased an Addressograph, a printing machine used to efficiently produce ink impression mailing labels for the Weekly Newsletter and Headnotes, which was used until the processes were outsourced later.

Until the 1990s, lawyers wishing to join the DBA were required to obtain signatures from two current members vouching for them. Dues were hand-posted by staff on 4x6 cards until IBM computers were finally purchased.

There were few CLE meetings at the Adolphus, but Clinics with lunch service were a long-established tradition and held in cramped space on the first and third Friday of the month. New members were introduced there monthly. The meetings were popular and well-attended.

While at the Adolphus, food service for Clinics was prepared in a private club and wheeled on service carts through downtown to the Adolphus. Members were

required to register for Clinics if they wanted to eat. Today, members enjoy a delicious buffet prepared in a commercial kitchen. No reservations needed.

The Bar always dreamt of owning its own headquarters, and in 1977 it raised over $1 million to purchase and renovate the Belo Mansion. Some wondered what our leaders were thinking, buying a former funeral home on the other side of downtown. After extensive renovation, the staff, along with a branch of the Dallas County Law Library, moved into the Mansion in 1979.

Some members resigned their memberships because they believed the building was inconvenient and a wasteful expense, but with the foresight of leaders, including Waller Collie, Jr., Bob Thomas, and the Hon. Jerry Buchmeyer, the city would grow north with development around our headquarters, beginning with the Dallas Museum of Art (1984), the Trammell Crow Tower (1985), the Chase Tower (1987), and the Meyerson (1989). The Mansion was now right in the middle of the newly created Arts District, and firms began to move to nearby buildings. The decision to purchase the new headquarters proved to be one of the greatest accomplishments in the history of our Bar.

The DBA hosted the American Bar Association Annual Meeting the summer of our move to the Mansion and could now show off its own headquarters to suitably impressed national bar leaders. That year, the Magna Carta also came to Dallas and the DBA was honored to

display it to the public at its new headquarters.

Without our headquarters in downtown Dallas, the Bar could never have accommodated its growing membership. With the facilities the Mansion provided, members could now easily meet to exchange ideas and create new programs and projects. It was only natural that CLE programs grew from roughly 35 per year at the Adolphus to over 400 per year today. New Sections and Committees were created as well, now that there was space for their meetings.

In the 1980s, the DBA became a national leader among bar associations with the creation of the Minority Participation Committee. This was the catalyst for the creation of joint programs with Allied Bars, minority clerkship luncheons, and the establishment of the Sarah T. Hughes Diversity Scholarship Program to provide scholarships to minority students at area law schools. Bar None was created in 1986 and today has raised in excess of $2 million for the Hughes Scholarships.

Diversity throughout the membership and within its leadership has grown greatly over the years. The DBA has seen its first woman President, Harriet E. Miers, and thereafter, the first African American President, Rhonda Hunter, and the first Hispanic President, Laura Benitez Geisler. Today, the Bar has a very diverse board, including a judicial seat and all Allied Bar Presidents serving as voting members.

Bar leaders have always encouraged pro bono involvement. The Dallas Volunteer Attorney Program (DVAP) was created in 1997 to coordinate and provide more services in the community. Annual fundraising for the program has grown enormously from several thousand dollars to over $1.5 million today, and its services have multiplied.

The Texas High School

Mock Trial Competition and the Law in the Schools & Community programs are well-established programs created in the late 1970s. They have grown since then and are important programs for students in our schools. Later, more activities related to students were created, including the Bar’s Summer Law Intern Program, Mentoring Program, and Law Day Contests. Our Bar became a role model for other bar associations’ education-related programs.

By 2000, membership reached 7,500. Meeting space was at a premium, and parking was still limited to only 60 outdoor spaces (with two spaces never used because hundreds of grackles roosted in trees above them) behind the Mansion. Parking was gridlocked most days.

In 2001-2002 through efforts of DBA leaders, including Nancy A. Thomas as Construction Chair and Mark A. Shank as Fundraising Chair, we raised $14 million to add the Pavilion to the Mansion, which now includes additional meeting space, as well as 250-plus parking spaces in a covered garage.

I have always been proud of the DBA, its members, and its programs. Members have not only given generously of their time to the Bar, but have also served in many other leadership capacities in our community, including on the Dallas City Council, Commissioners Court, and as Mayor, including the City of Dallas’ current Mayor Eric Johnson.

The DBA has consistently been recognized by the State Bar of Texas and the American Bar Association for its comprehensive and innovative programming and, with the engaged can-do membership of 11,800+ today, it is certain that positive growth will continue for many years to come.

26 Dallas Bar Association | 150th Anniversary

Cathy Maher retired as the Executive Director of the DBA in 2016. She lives in Dallas and can be reached at catharinemaher@gmail.com.

Goranson Bain Ausley is pleased to welcome five highly-accomplished Texas family law attorneys to our firm. Their presence expands our footprint within the state while also increasing the depth and breadth of our expertise. Cindy, Chris, Gary, Clayton, and Cassidy bring with them distinctive skills and a proven record of success in helping to resolve today’s most challenging family law issues. With their addition, along with two new offices in West Texas, we can now serve even more people in more places with greater resources to protect families and secure futures.

DALLAS 214.449.1748

PLANO 972.445.9062

AUSTIN 512.687.8949

FORT WORTH 817.518.4622

GRANBURY 817.518.4894

GBAFAMILYLAW .COM

Growing in strengths. Not just numbers.

Recognized leaders in family law join our team in Fort Worth, Granbury, and Midland.

Cindy Tisdale Chris Nickelson Gary Nickelson

Clayton Bryant Cassidy Pearson

A Brief History of Mock Trial in Texas

by Stephen W. Gwinn

Law-focused education programs began to appear across the fruited plain in the 1970s. In Texas, the program was known as Law in a Changing Society and was directed at classroom students in Texas at all levels. One of the activities included in that program was Mock Trial which was conducted in Dallas ISD classrooms. In 1979, a citywide competition was sponsored by the Dallas Bar Association’s (DBA) Law in a Changing Society Committee and DISD. Classroom Mock Trial received such a positive response that in June of 1980, the DBA organized a “statewide” competition that included four teams. The winner of that competition was Woodrow Wilson High School, and former DBA President Al Ellis was the coach of that team. This was the first such competition in the nation.

In 1982, the DBA opened an office for a statewide program at the DBA headquarters and installed former classroom teacher Judy Yarbro as the coordinator of the program. Texas was on the forefront of mock trial and the competition grew from four teams in 1980 to 17 teams in 1981, and the program received the State Bar of Texas Award of Merit. In 1982, regional competitions were organized throughout

the state through the Texas Education Agency’s Regional Service Centers and the competition had grown to over 150 schools by 1983.

In 1985, Texas and Oklahoma, along with six other states, created the All-States Competition (which is now called the National High School Mock Trial Competition). Corpus Christi Richard King High School won that National Competition. Dallas hosted the National Championship in 1988 with 24 teams. The Dallas County Commissioners’ Court adopted a resolution declaring May 2, 1988 as National Mock Trial Day in Dallas. Westlake High School finished second at that competition, losing only to South Carolina’s Socastee High School in the final.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the competition continued to grow and improve. The decision was made to mirror the National Competition and enlarge the team size from six students to 10, with three lawyers and three witnesses on each side. Success followed the Texas team, as teams from Texas placed second in 1991 and 1992 (Richard King High School) and third in 1999 (Kerville Tivy High School). In 1997, Lake Highlands High School completed an undefeated record at Nationals and also finished third. The coach of that team was Steve Russell, who would become a Vice-Chair of

the DBA’s Texas High School Mock Trial Committee and serve in that role for more than 20 years.

In 2007, Texas once again hosted the National Championships in Dallas. Forty teams from as far away as South Korea participated. The competition earned the DBA additional State Bar accolades and the Texas team from Richardson High School finished eighth. In 2008, Texas added a Professionalism Award which would be named after the state’s first ever State Competition Coordinator, Judy Yarbro. This award is the only award at the State Competition where the teams themselves decide the winner. In 2016, the National Competition added a Courtroom Artist category to the competition, and Texas would follow suit in 2017. Texas Artists consistently place in the top three every year and the Texas Courtroom Artist Competition routinely draws more competitors than the National Competition, despite being half the size.

DBA members generously donate their time every year to judge three locally held competitions, giving hundreds of hours to students in the area and for the State Championships. The committee works 11 or 12

months every year, as the end of one Mock Trial season means the start of another.