PORTFOLIO

Master of Architecture Candidate

University of Louisiana at Lafayette (337)354-3195

justinpeltier27@gmail.com

University of Louisiana at Lafayette Master of Architecture

August 2022-Present

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Bachelor of Science, Architectural Studies

August 2018-May 2022

Early College Academy Associates Degree, General Studies

August 2014-May 2018

1st Place, ARCH 502 COTE Project Spring 2023

Design Excellence Fall 2018, Spring/Fall 2019, Spring/Fall 2020

Design Merit Spring/Fall 2021

University of Louisiana at Lafayette Graduate Assistant

August 2022 - Present

Vermilion Architects

Architectural Intern

October 2021 - January 2023

Another Broken Egg Cafe Waiter

October 2016 - June 2018

-Skateboarding

-Motorsports

-Playing Guitar & Drums

-Video Games

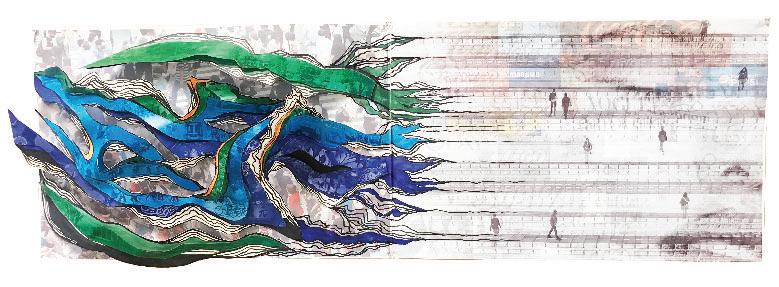

Re-defining the relationship between ecology and industry, helping to prevent wildfires and sustain local farming communities in the Bay Area of California

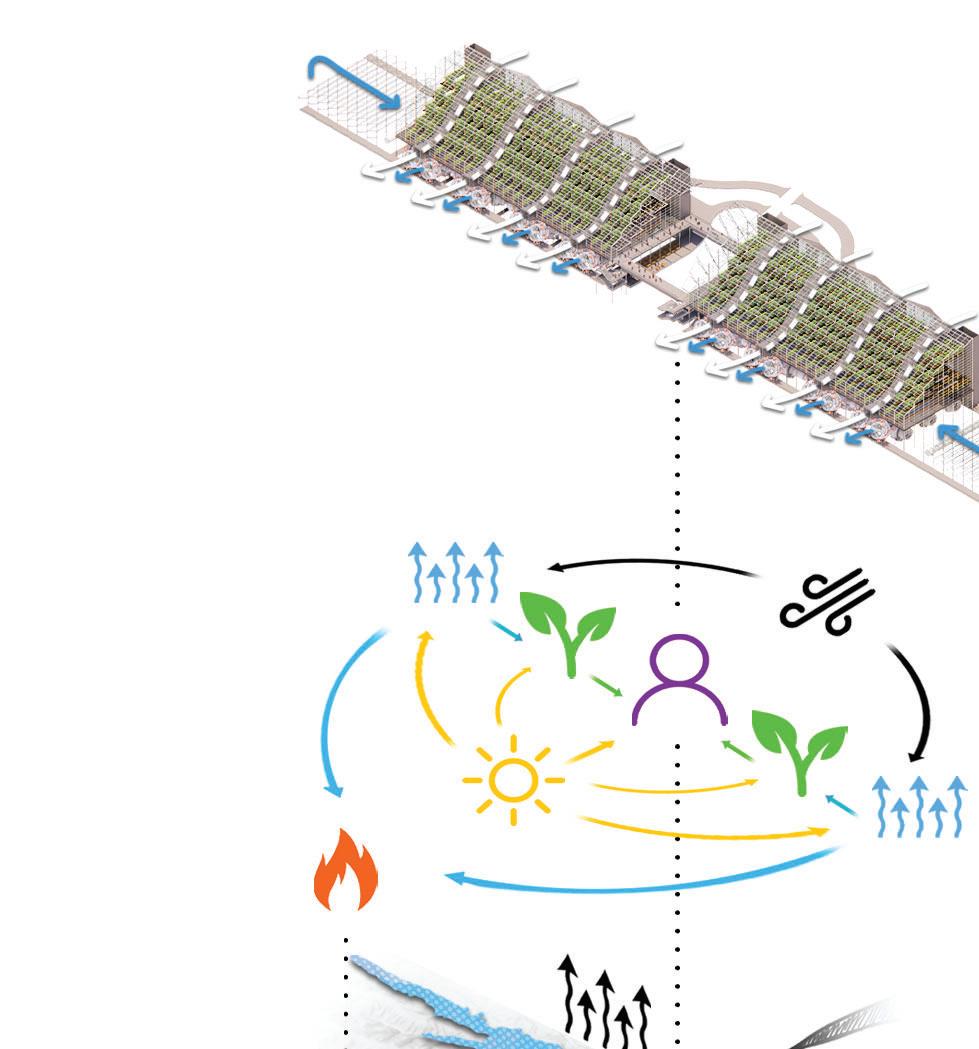

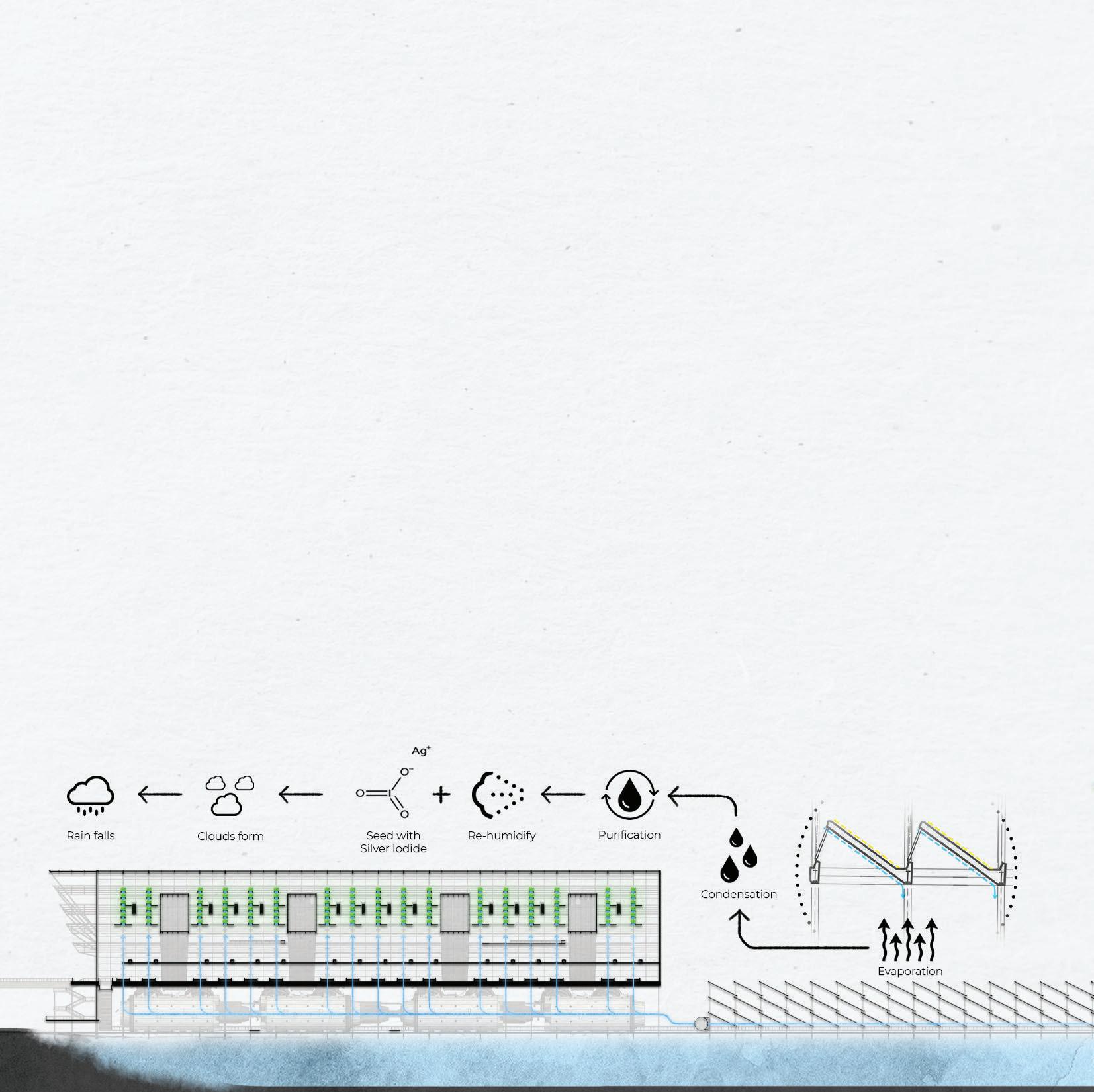

With climate change amplifying California’s water cycle, the dry period of the year now sees much higher evaporation, leading to dried out landscapes and empty reservoirs. When combined with California’s farming and irrigation strategies, water scarcity and natural disasters, like wild fires, are bound to happen. The site poses a unique opportunity for an architectural intervention that would restore balance to this area’s water cycle. In turn, there can be harmony between water, ecology, and industry

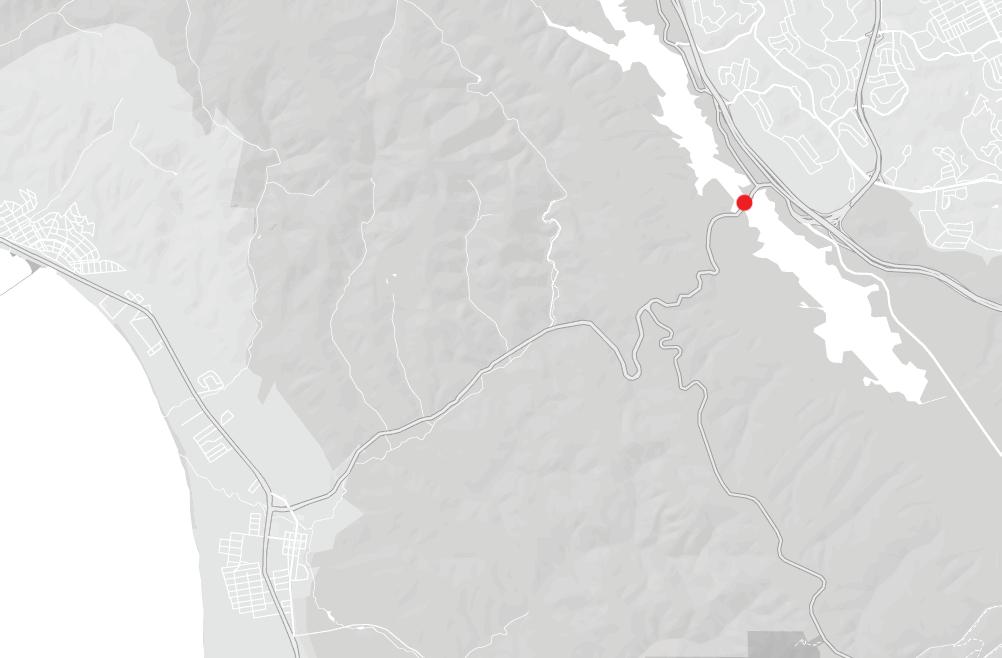

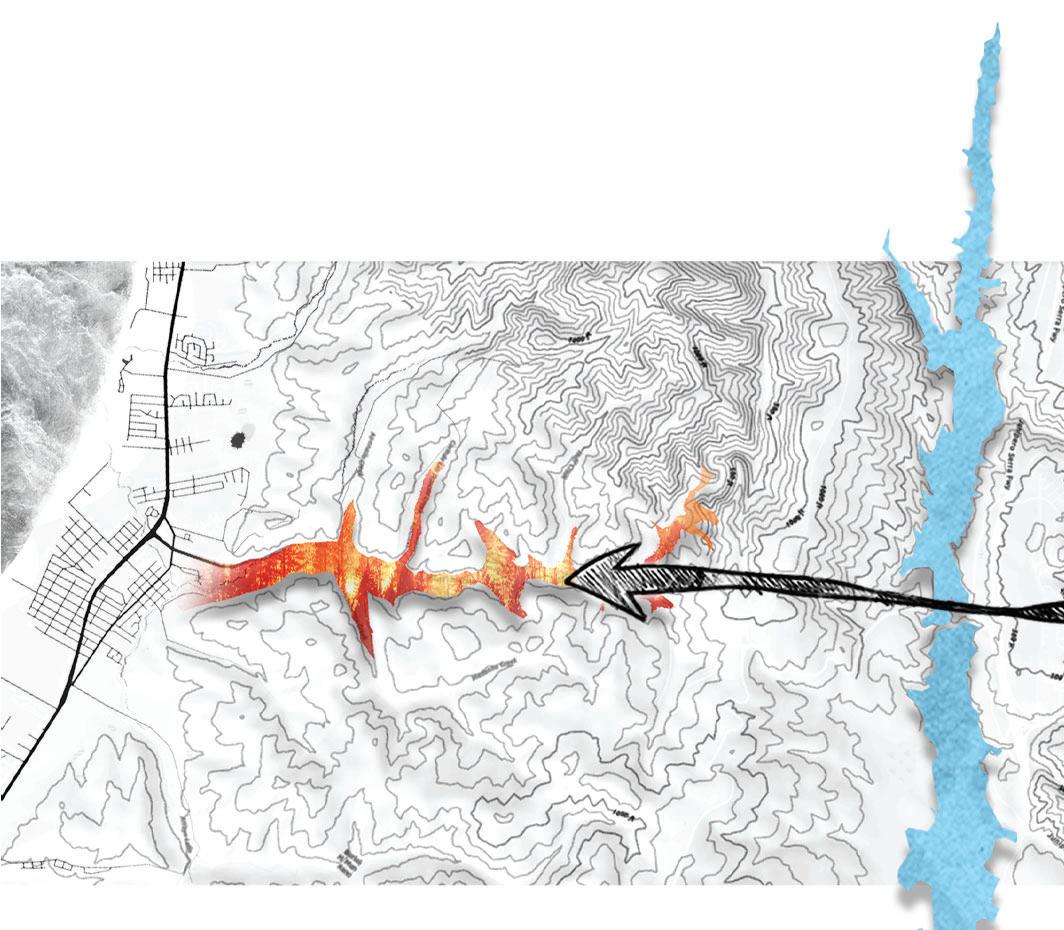

Albert Canyon is home to a wide array of farming communities, and Half Moon Bay has more than 11,000 residents. Both areas have an extremely high risk of wild fire destruction due to dry conditions, and the presence of Diablo Winds coming from the east only exacerbates the risk of these fires. However, before these winds reach the canyon, they pass over Crystal Springs Reservoir, one of the largest man made bodies of water in California. Due to the rising temperatures and evaporation in California, this reservoir alone loses 80 million gallons of water a year. The Cloud Factory exists as an architectural intervention between these natural energy flows, turning destructive conditions into constructive ones. The building captures evaporation over the reservoir and converts it into rain clouds. Through channeling the Diablo Winds from the east, the clouds are carried to the canyon, restoring moisture to a dried out landscape.

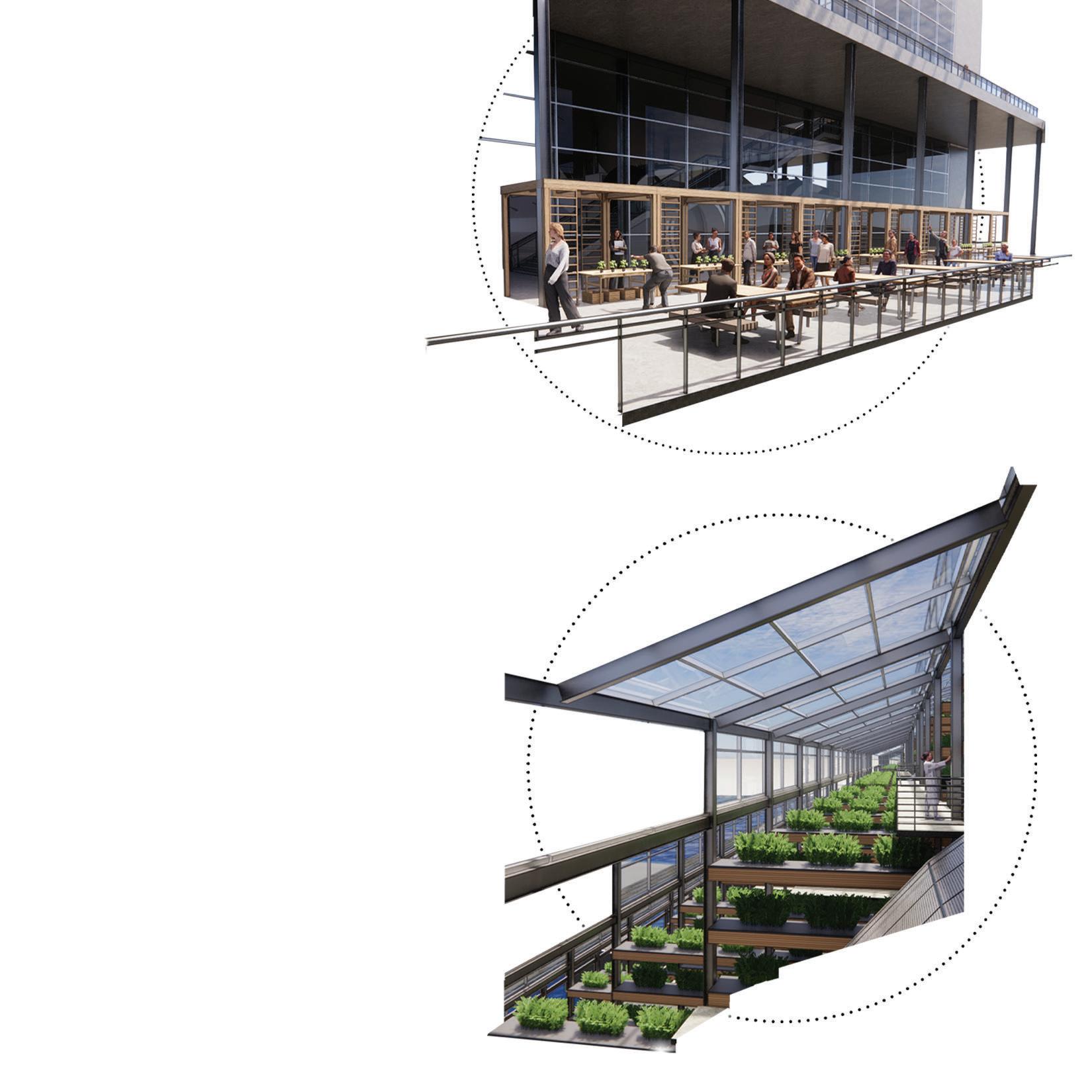

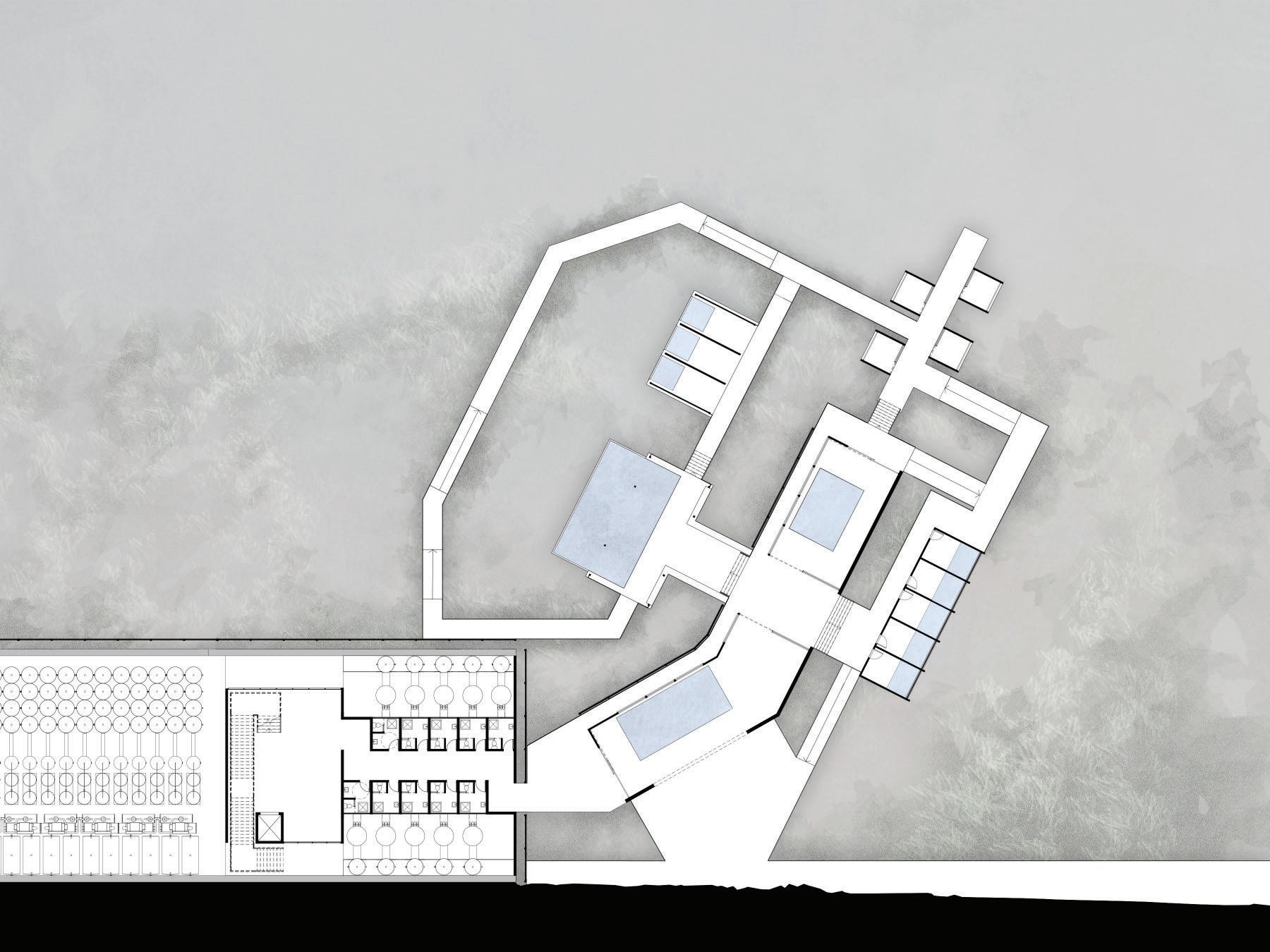

The public area serves as a marketplace for buying produce from the farm and other local vendors. Visitors are able to learn about local farming communities and the sources of their food, as well as learn about the local ecologies of the site. In addition, the public plaza also serves as a viewing area for the creation of clouds coming from the building. This part of the building program introduces the aspect of community and interaction into an inherently industrial building typology.

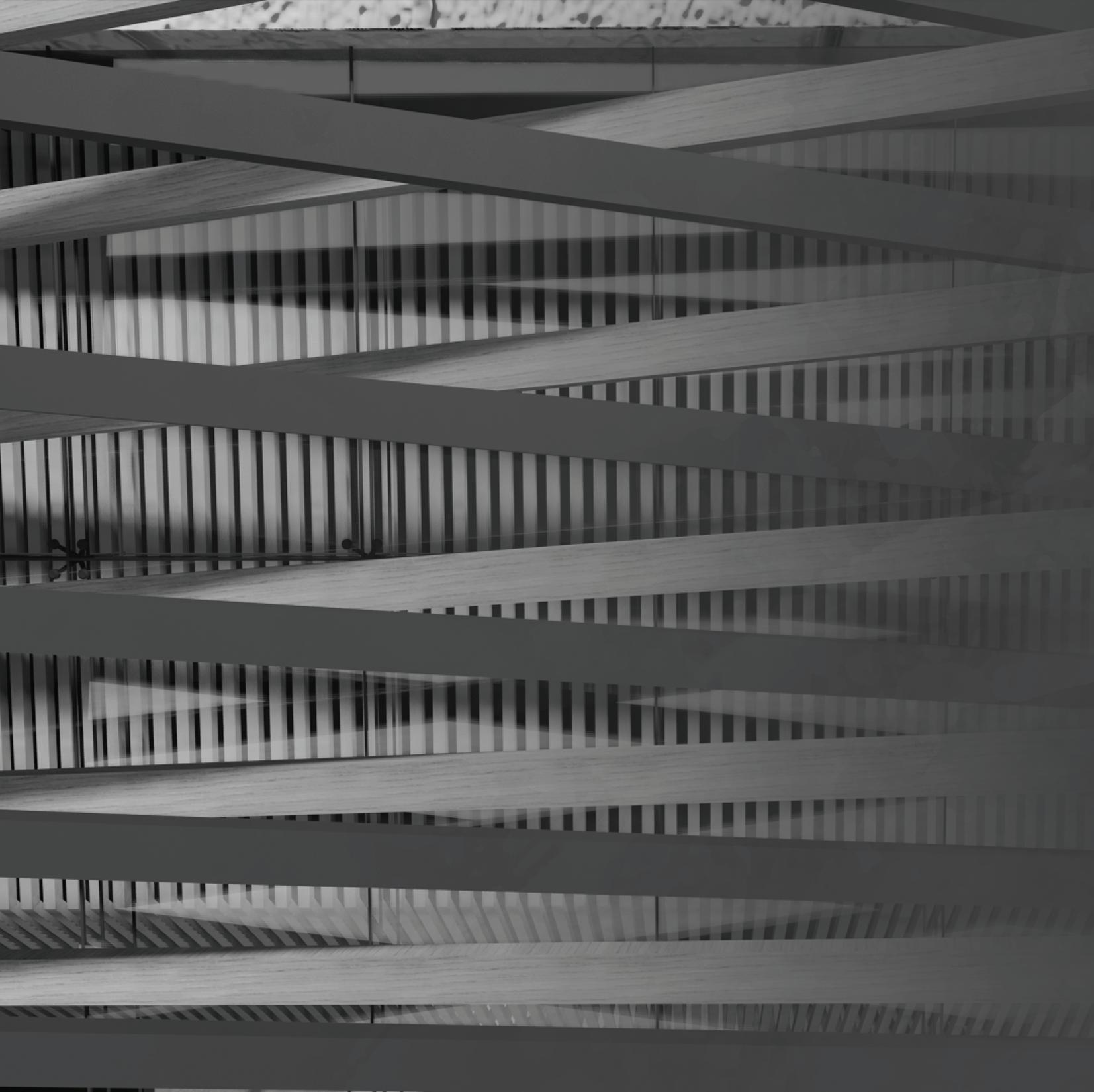

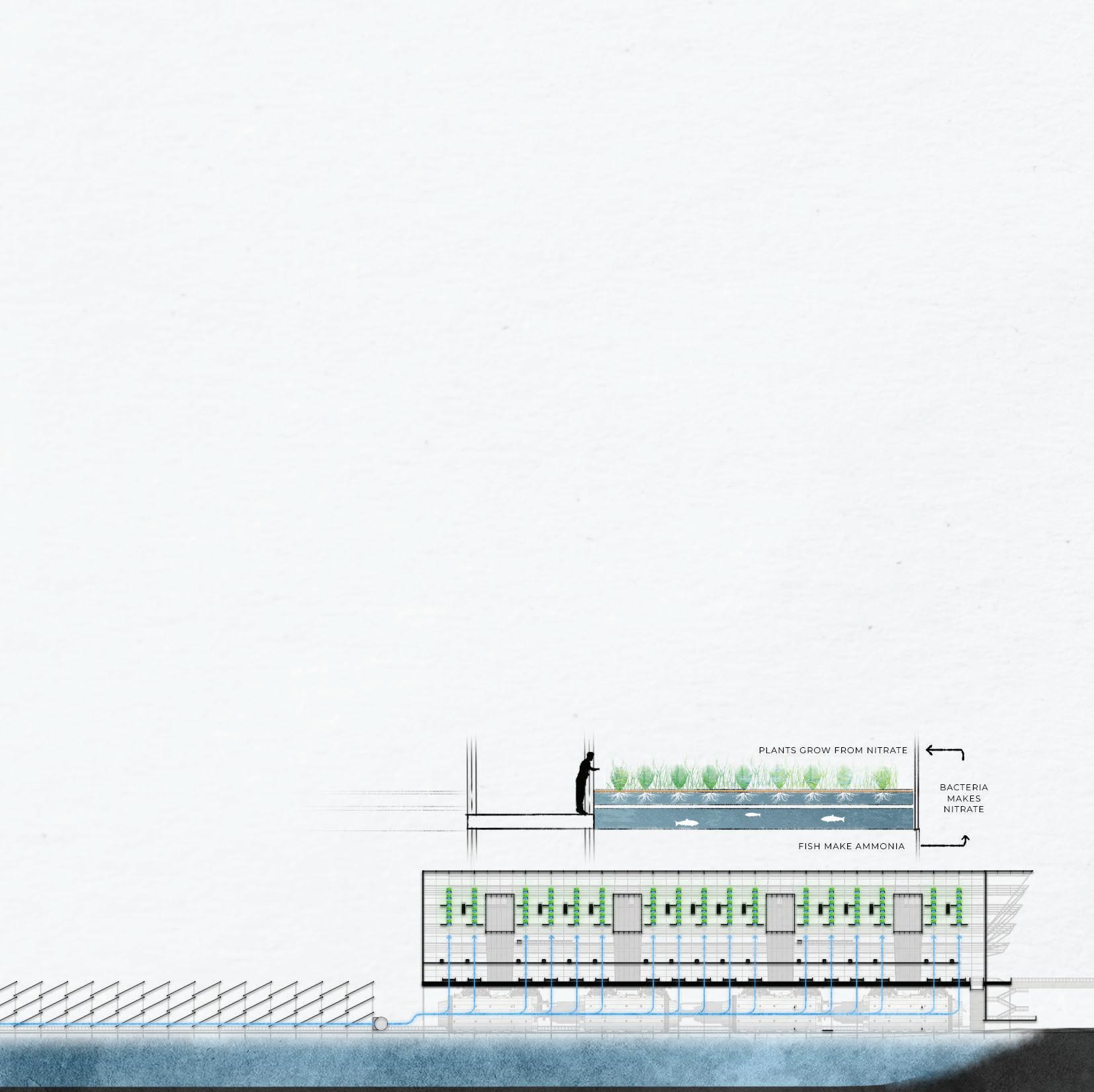

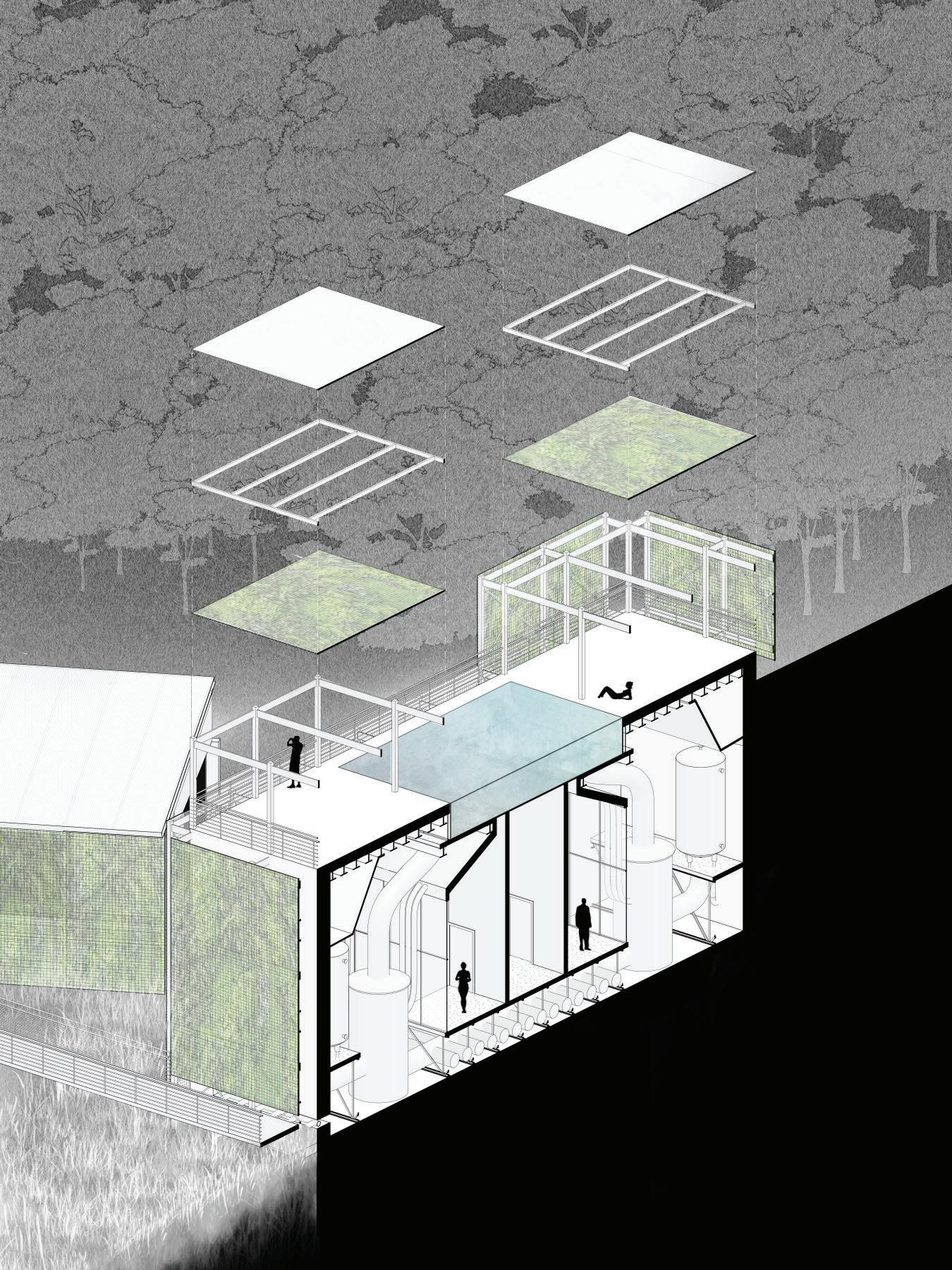

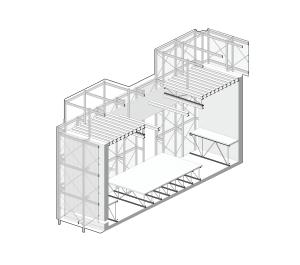

The aquaponics farm utilizes both water and fish harnessed from the reservoir, creating a more sustainable farming practice for the area. Aquaponics farms use only a fraction of the water that traditional farms and irrigation strategies use, while also having the added benefit of producing fish. These farms are stacked along the topside of the building’s geometry, allowing full sun exposure to every piece of produce.

The building’s program consists of two primary pieces: an aquaponics farm and a community plaza.

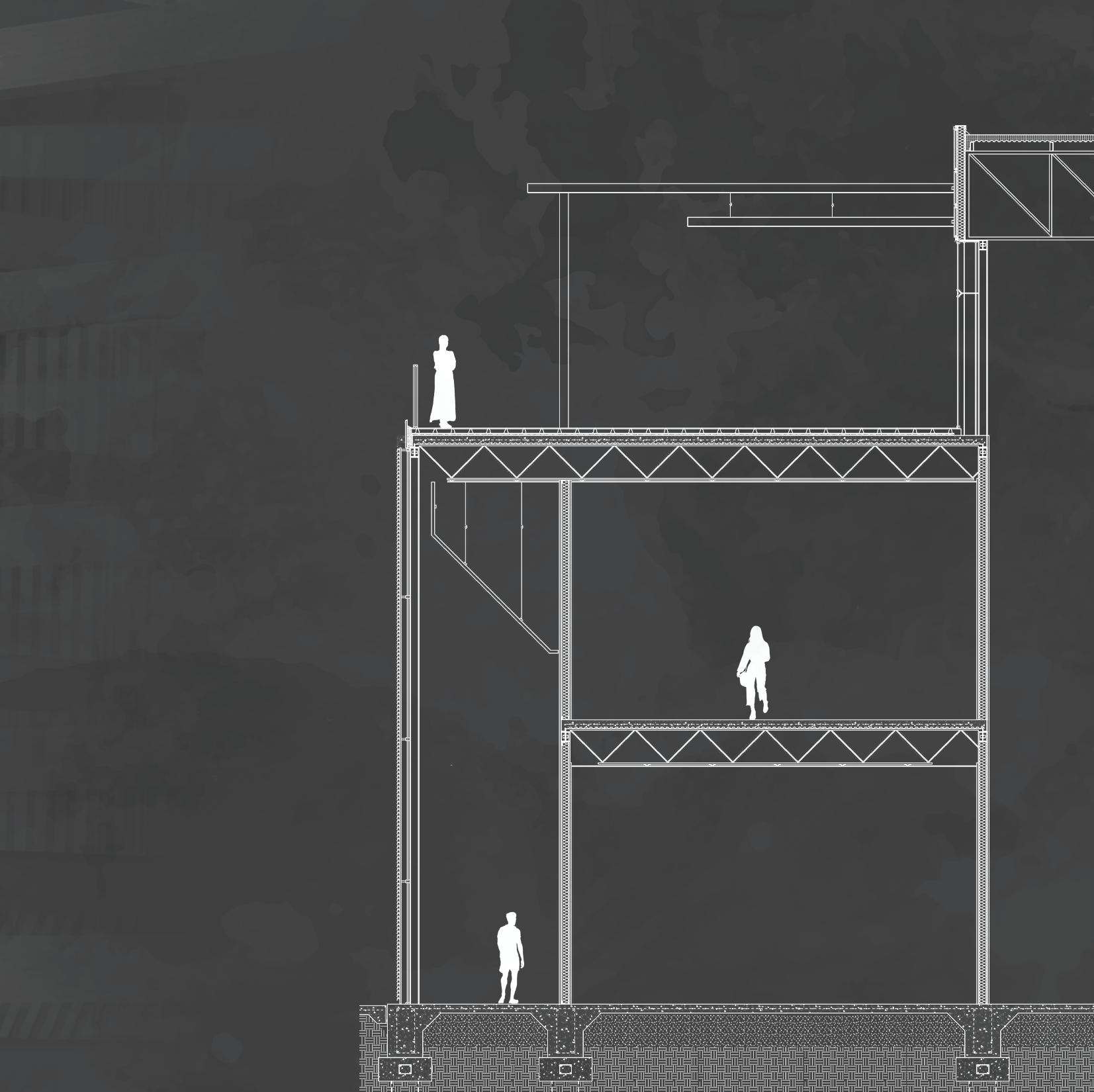

The building’s form is divided into two primary sections, each driven by water. The first is to harness evaporation, and the second is the channeling of water for both the creation of rain clouds and usage by the aquaponics farm. Within the farming area, the water is channeled up the columns of the stacked farm beds. The produce can be collected and passed along a system of conveyer belts towards the backside of the building, where it is packaged and shipped out.

Before the Dutch settled in New York, Manhattan island was home to more ecologies than any of the current national parks in the United States. Throughout the last 400 years, the island has been transformed into one of the largest cities in the world, with nearly all of these ecologies being lost. This project looks at a hypothetical scenario of 100 years in the future, where these ecologies have been restored and humanity lives in harmony within them.

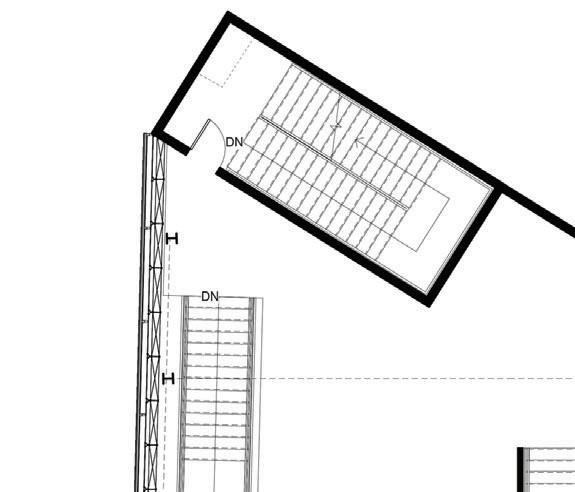

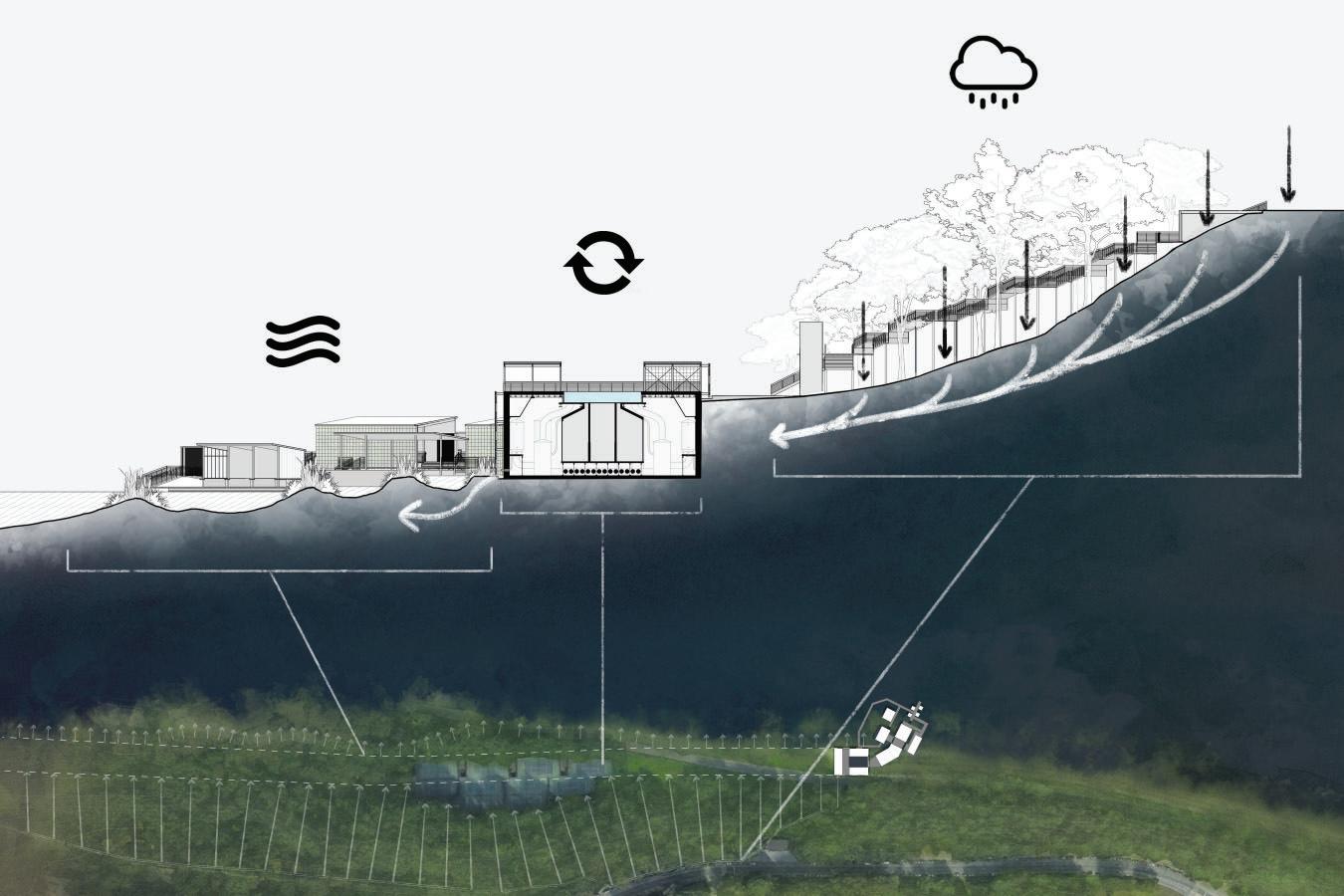

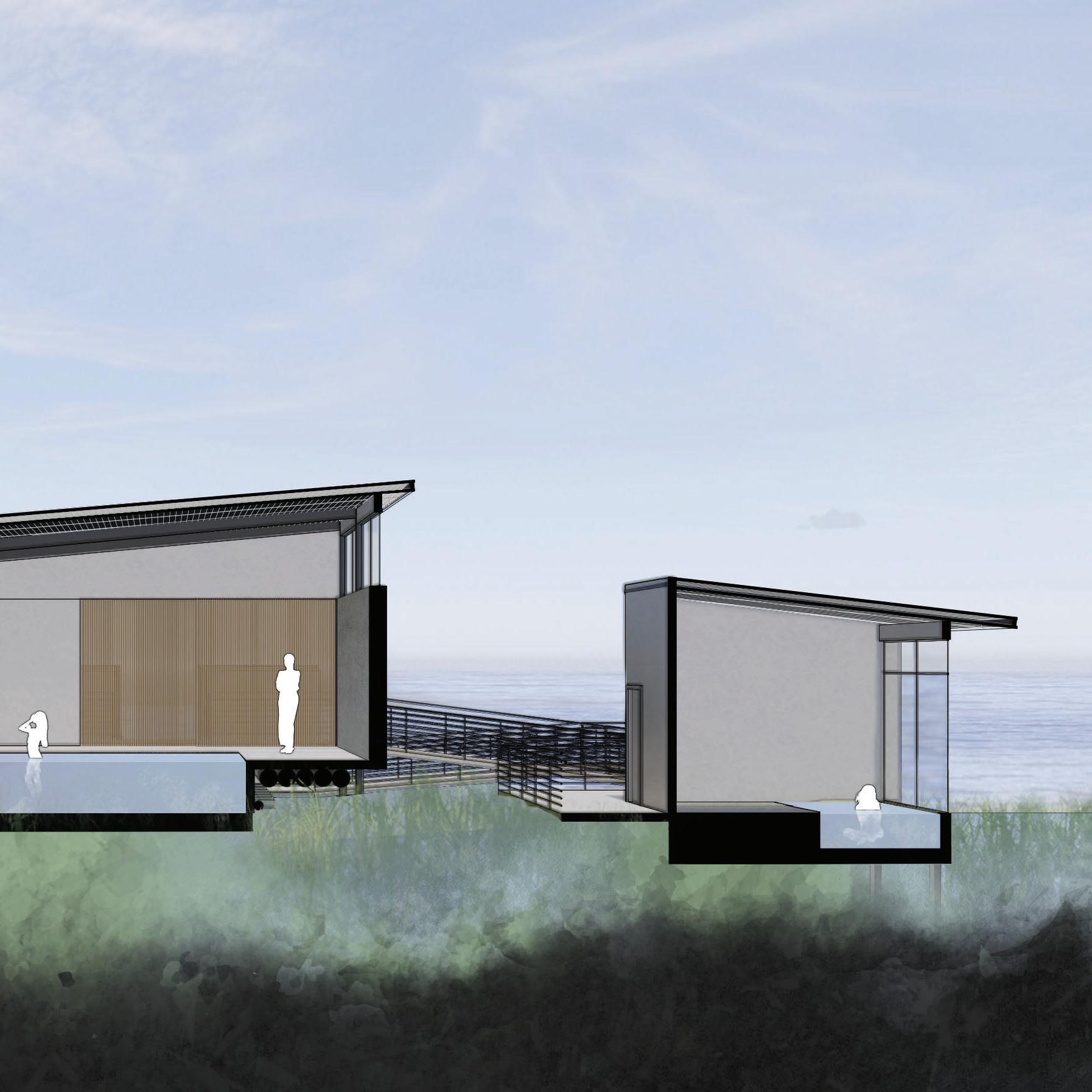

Around 400 years ago, the building site consisted of a steep hillside leading into a riverside marsh. In 2122, sea level rise will render Henry Hudson Parkway unusable, and will also create unfavorable conditions for wildlife on the banks of the river. In order to restore the previous site conditions and host healthier ecologies, the area would require an introduction of fresh water to create brackish water conditions. To do this, the building uses a rainwater collection system over the span of 50 acres. Water is passed and filtered through a decommissioned train tunnel, and is used as a constant water source for both the restored wetlands and the bath house.

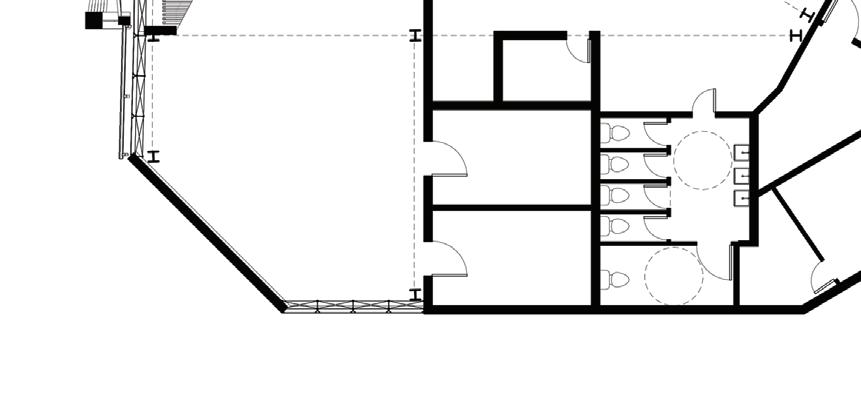

The entrance to the site from Riverside Drive brings the user down the steep slope towards the bathhouse. This serves as an educational walkthrough, allowing the user to learn about the history of the site throughout the last 500 years. The entrance to the bathhouse is down the stairs into the old train tunnel.

OCCUPIABLE SPACE

The tunnel serves as an entrance to the bath house, with all of the water treatment systems visible to the user. The bath house itself consists of a set of warm pools, hot pools, saunas, and cold plunges. Each space is nestled within the wetlands lanscape, creating a one on one interface with the ecologies of the site.

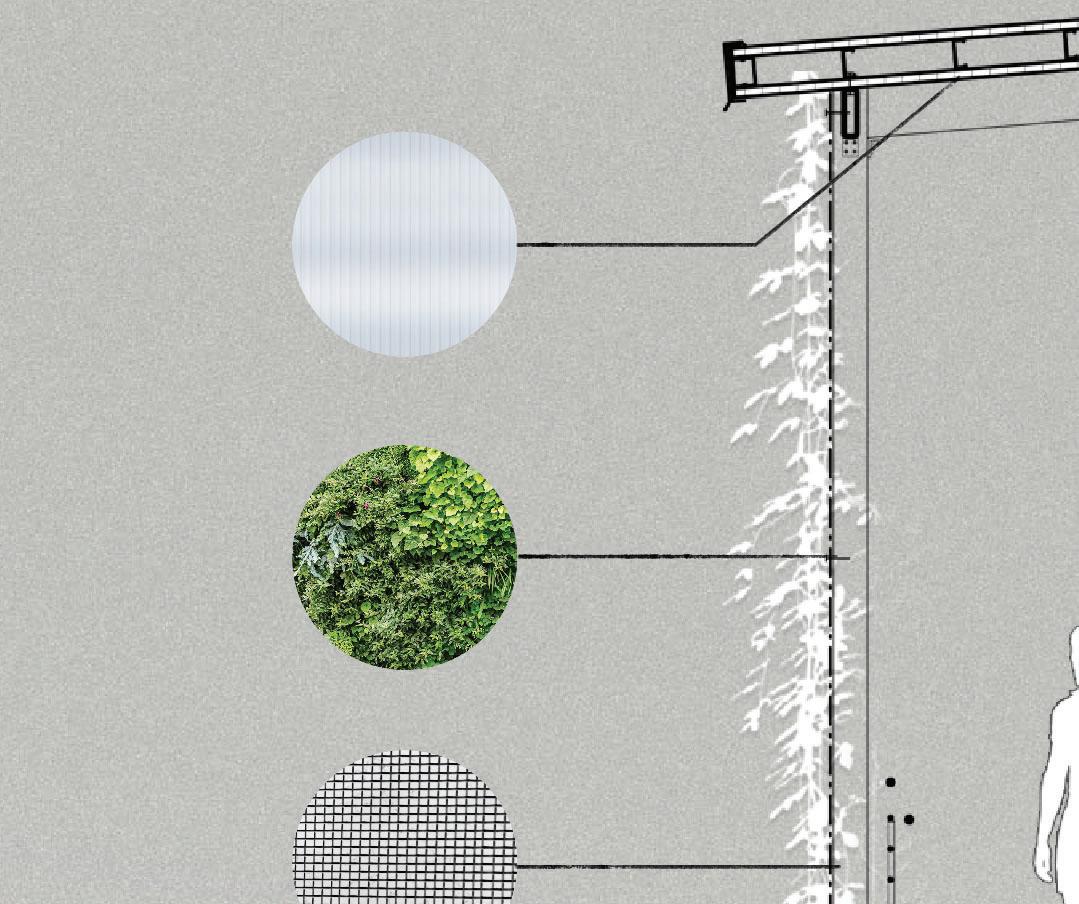

As the building reaches farther into the wetlands, the spaces become more private. At the entrance is a public warm pool, while at the far end are private saunas. Each facade is designed in a way that allows the building to blend into the landscape, all while still allowing visibility and connection out to the surrounding landscape. This is done with wire screens covered with climbing ivy. The roofs of most of the spaces are made with polycarbonate panels to allow ample natural light into the bath house.

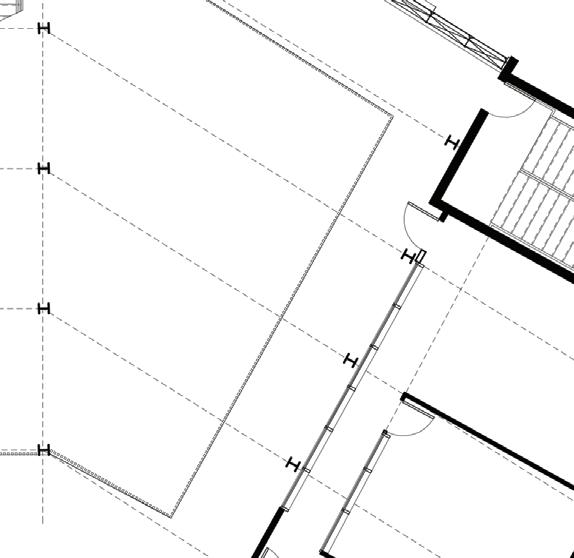

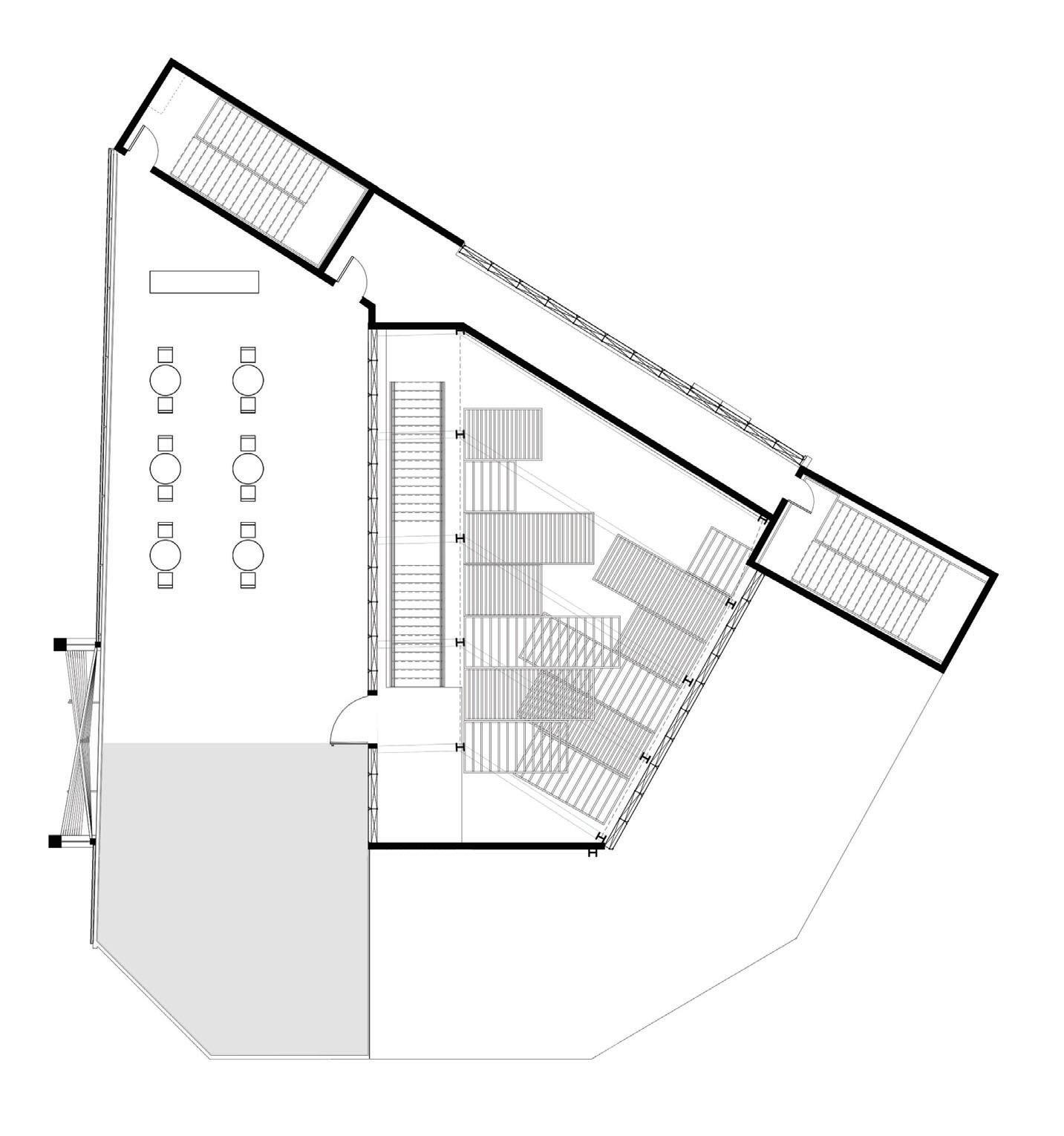

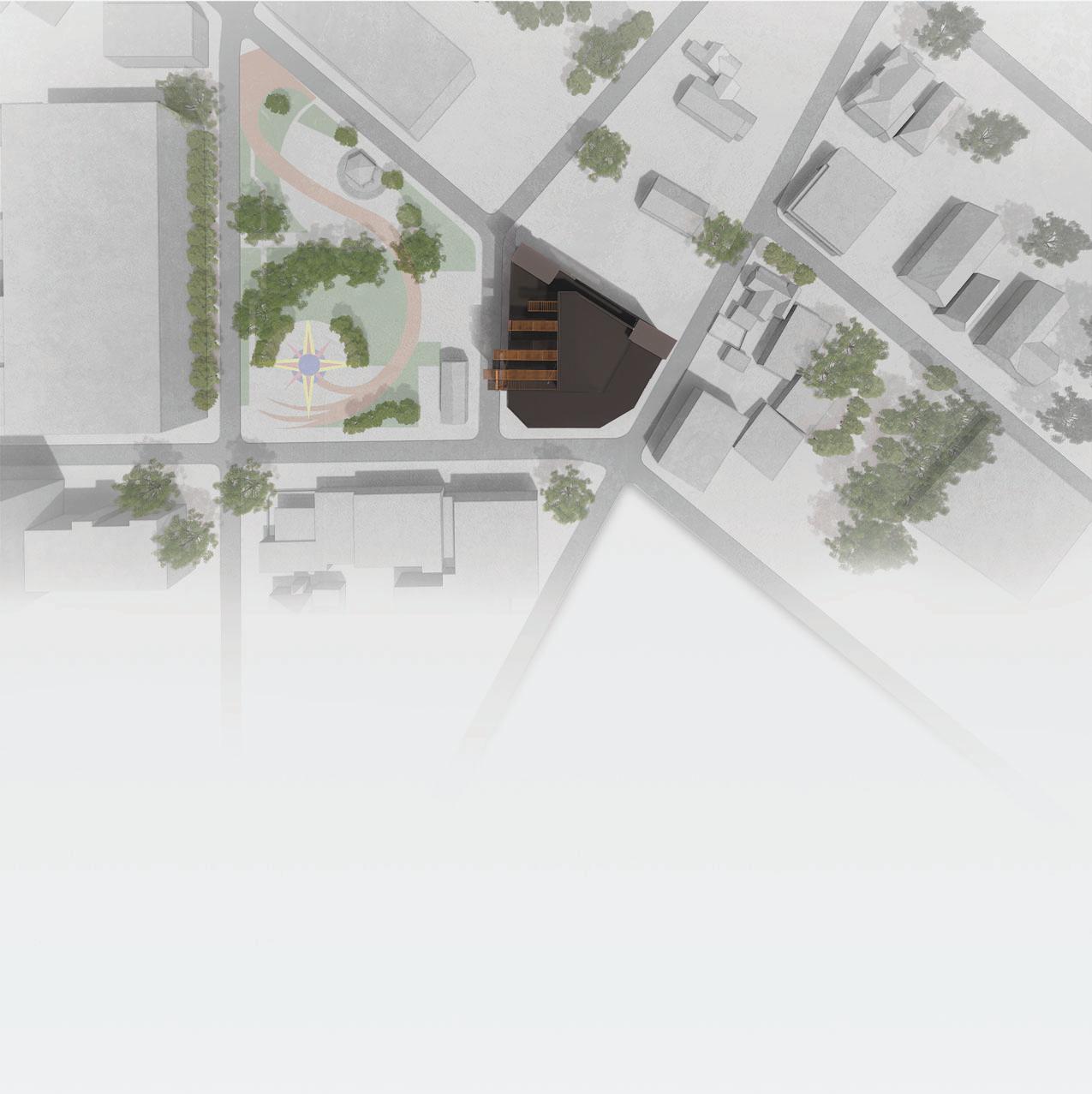

MERGE Culinary Museum rests upon the intersection of the two defining grid systems of Lafayette, Louisiana. Viewing these grids through a historical lens, the museum serves as a window into the connection of French and American culture.

Lafayette was originally planned based on the French long lot system, aligning plots of land perpendicular to the flow of the Atchafalaya River. After the introduction of the North-West Ordinance and the Intercontinental Railroad, another city organization strategy was introduced.

With the building site resting on one of the moments of intersection between the two grids, a unique opportunity was presented. Using this condition as a generator for the building, an open centralized space was created to highlight the moment of crossing between the grids. Each side of the grid was given a unique material, furthering the distinction and highlighting the areas where they cross. Ultimately, this was designated as the restaurant space due to how Cajun food can be seen as a mix between many cultures, including French, American, African, and Native American.

PARK SANS SOUCI

E VERMILION ST

PARK SANS SOUCI

E VERMILION ST

The entrance is located on the western facade due to its direct relationship with Park Sans Souci, as well as having the majority of foot traffic in the area. This motif of the two materials is primarily highlighted on this facade, coming together to signal the entrance. Louver systems are placed on either side to shade from direct sun exposure while also allowing some level of visibility into the building. The rooftop shading structure has both materials colliding as one, representing the collective culture of South Louisiana.

The grids are present in the overall plan, being two separate entities that come together in a centralized restaurant space. The grids are also emblemized by the melding of two different materials, representing the past and present of Cajun life and food.

The interior consists of a restaurant, a culinary museum, a demonstration kitchen, and office spaces. The restaurant is the main driver of the building, being an open centralized space by which all the other interior spaces are organized around.

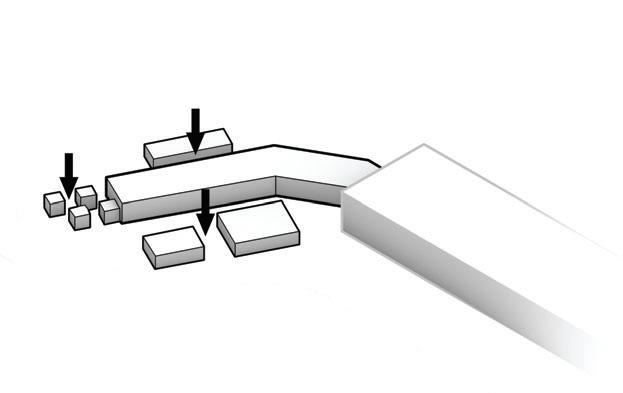

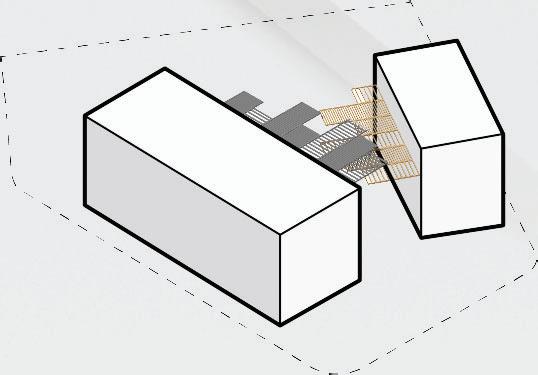

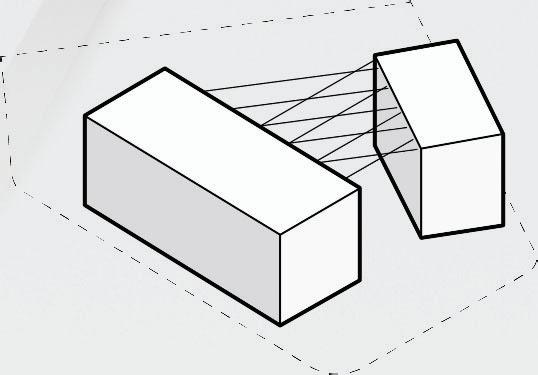

The initial gestures explored different tectonics and spatial conditions that highlighted the intersection of the two cultures. The overall building form adheres to the crossing grid systems, especially in the open center space. The larger fragment model explored both the structural system of this space and the northern facade.