T he Böhler

Madonna by Giovanni Pisano

MAX SEIDEL

IN COLLABORATION WITH SERENA CALAMAI

MAX SEIDEL

IN COLLABORATION WITH SERENA CALAMAI

MAX SEIDEL IN COLLABORATION WITH SERENA CALAMAI

Dear Friends of the Kunsthandlung Julius Böhler,

For me, it is a great pleasure to be able to present a very special Madonna to you at this year’s TEFAF that has been the centrepiece of our family collection for 120 years. The masterpiece is a work by the Italian artist Giovanni Pisano, court sculptor to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII. Created in about 1313, it was restored around 1490 by Benedetto da Maiano.

In 1904, my great-great-grandfather Julius Böhler acquired the marble Madonna and Child at the Somzée auction in Brussels where more then 2,000 works of art, brought together by one of Belgium’s most important collectors, were sold after his death. At that time it was attributed to the Renaissance artist Nicola Pisano (1434-1538). Léon Somzée, an extremely successful engineer and Belgian politician, probably acquired it in Rome between 1864 and 1867.

Thanks to his expert eye Julius Böhler had succeeded in acquiring an extraordinary work of art for his important private collection. The Madonna was not intended for sale. It found a new home in the Palais Böhler in Brienner Strasse in Munich, the representative seat of the company and the family home.

A special feature set the sculpture apart right from the start. It was evident that the head and the body did not belong together and even dated from different eras. An art-historical puzzle had to be solved.

The first attribution of the figure, that had rarely been displayed in public, was to Tino di Camaino, a pupil of Giovanni Pisano. Since then, Max Seidel – an internationally recognised expert on Giovanni Pisano – has successfully proven the sculpture’s attribution to Giovanni Pisano himself. Seidel backs up his theory through stylistic comparisons with works acknowledged as being by Giovanni Pisano which are discussed in this publication. He explains the addition of the lost head by Benedetto da Maiano – equally attributed due to style – on account of the extraordinarily high esteem in which the Pisano Madonna must have been held in the late 15th century. Only an artist comparable to Giovanni Pisano, such as Benedetto da Maiano, was allowed to create the new head of the Virgin Mary. This was a unique course of action for which no comparison is known to date.

Thanks to the interaction of these two great Italian artists spanning different epochs, this work combines the Italian Gothic with the Renaissance in a harmonious and artistically convincing way.

I invite you to embark on an art-historical journey with Max Seidel and I am already looking forward to showing you this beautiful and extraordinary work, to which I am particularly close, on our stand.

Finally, I would like to express my thanks to Eva Bitzinger and Julia Scheid for their, as always, profound editorial work.

Yours,

Florian Eitle-Böhler

GIOVANNI PISANO

GIOVANNI PISANO

Circa 1248 Pisa – 1318 Siena

Circa 1313

Restoration of the head of the Madonna attributed to BENEDETTO DA MAIANO 1442 Maiano near Fiesole – 1497 Florence Marble, with later partial gilding Height 60.5 cm

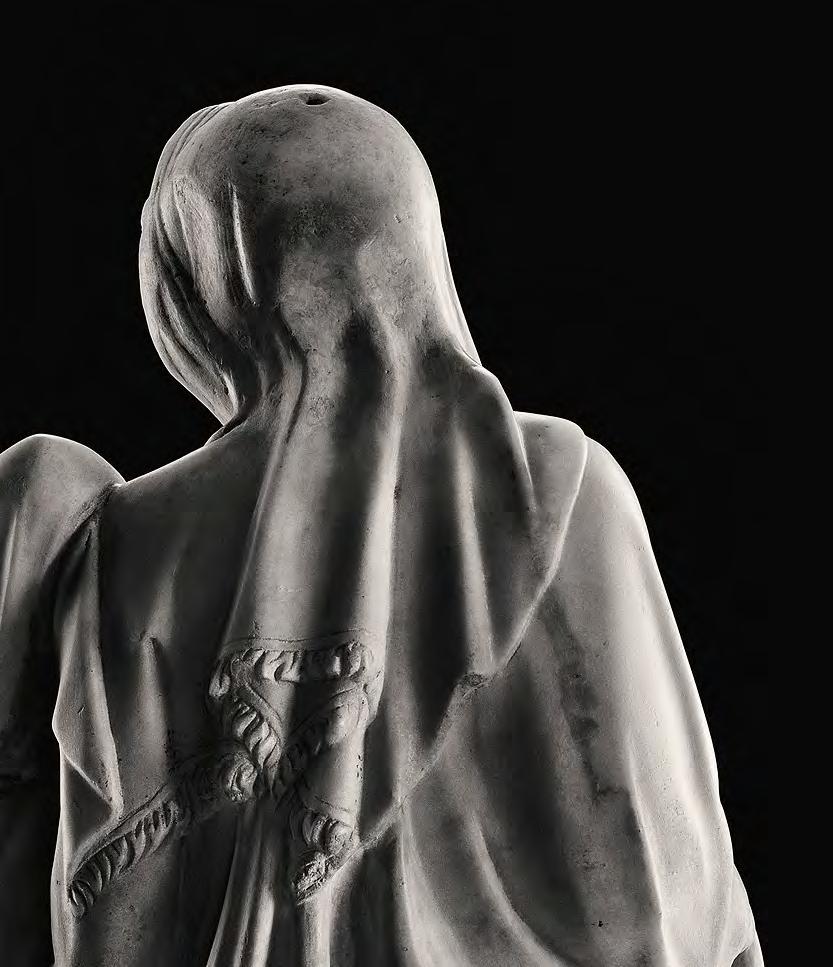

Fig. 1 Giovanni Pisano, Madonna and Child (Head of the Madonna by Benedetto da Maiano), Starnberg, Böhler Collection

Fig. 1 Giovanni Pisano, Madonna and Child (Head of the Madonna by Benedetto da Maiano), Starnberg, Böhler Collection

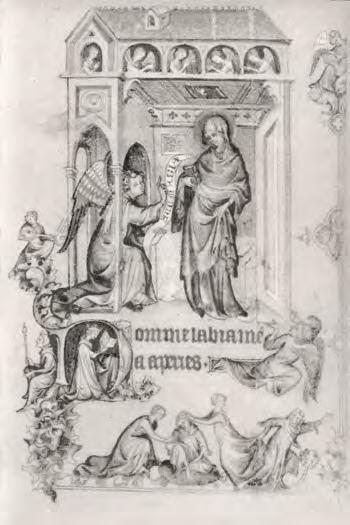

The Böhler Madonna (fig. 1) was acquired by Julius Böhler –Kaiserlich-Königlicher Hofantiquar and Königlich-Bayerischer Hofantiquar – from the Belgian collector Léon de Somzée at the auction of the huge collection belonging to the industrial gas magnate, held in 1904 at the Palais Somzée in Brussels (fig. 14). 1

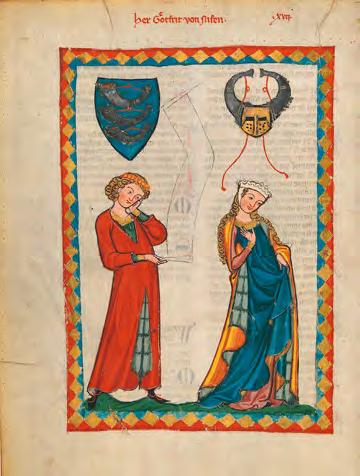

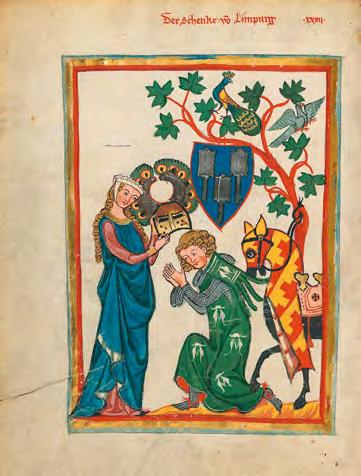

The sculpture has always been kept in private collections, initially in the Collection Somzée and later, until the present, in the Sammlung Böhler. The only exhibition of the sculpture, to a select public, took place in the summer of 1958 during the show entitled ‘Meisterwerke alter Kunst’ at the Böhler Gallery in Munich, as part of the celebrations for the city’s 800 th anniversary. On that occasion the statuette was presented with an attribution to the Sienese sculptor Tino di Camaino. 2

As we gather from the entries devoted to the sculpture in the two typewritten catalogues of the Böhler Collection, issued in 1931 and 1967, it is deducible, but not demonstrable, that Julius Böhler had asked Wilhelm von Bode (fig. 5) for an opinion on the statuette, but, probably because of the stylistic incongruity of the head, Bode preferred to suggest that the dealer should apply to the Italian art historian Adolfo Venturi. 3 As far as we now know, Bode never officially expressed an opinion on the attribution of the sculpture, although in those very years he was involved in the creation of a rich collection of fourteenth-century sculpture for the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum and enjoyed the availability of enormous sums of money for the purchase of excellent works, thanks to the generous financial support of the Emperor Wilhelm II of Prussia. 4

What is said about Bode’s judgement in the two Böhler catalogues, i.e. that Bode considered the body to be by Giovanni Pisano and the head by Benedetto da Maiano (fig. 1), we must assume to be a rumour passed on by dealers but not officially confirmed. 5 Both in the inventory of 1931 and in that of 1967 the white marble sculptural group with gilded fringes at the hem of the cloak, 60.5 cm high, is described as a work attributed by Adolfo Venturi in primis, and subsequently by Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, to Tino di Camaino. 6 Moreover, in the 1967 catalogue it is stated that the attribution to Tino was confirmed both by John Pope-Hennessy and by Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner, indicating also that in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston there was a similar headless Madonna, also by Tino, which was given to the museum by the American collector Charles Callahan Perkins. 7

From this documentation we gather that, after the acquisition of the work by Julius Böhler, the only ones who officially attributed the teenth-century sculpture to Tino di Camaino were Venturi, in 1906, 8 and Volbach in 1925 9 in the margin of a small scholarly article. In volume IV of his Storia dell’arte italiana, devoted to fourteenth-century sculpture, Venturi states that:

While he was in Pisa, Tino di Camaino must have executed a great many Madonnas, which remained typical for the Pisan sculptors. One is in Turin, in the Civic Museum, from the collection of the Marchese d’Azeglio, […] and this served as a model for another in the Berlin Museum, where it was ascribed to Giovanni Pisano, and for a third, entirely remade, which is in Munich at Böhler the dealer. […] The attitude of those Madonnas, raising the cloak with the right hand and gazing at the divine Infant, and the way in which he places his hand on his Mother’s breast, derive from models by Giovanni Pisano. 10

The attribution to Tino di Camaino was based on regarding the d’Azeglio Madonna (fig. 86) – a supreme masterpiece by Tino inspired by the late works of his master Giovanni Pisano –as the model for the Böhler Madonna (fig. 1) and for the Madonna and Child now in the Bode Museum (fig. 55), which Venturi then attributed to Tino although it was ‘ascribed to Giovanni Pisano’ on the basis of Bode’s initial attribution of 1886. 11 The d’Azeglio Madonna is signed by Tino di Camaino in the inscription (fig. 86): VIRGINIS A TINO FECIT OH QUAM CERNIS IMAGHO QAM GENUERE PATER[QUE] MAG[I]STRO. 12 Among the Madonnas which, according to Venturi, remained ‘typical for the Pisan sculptors’ he indicates the Madonna and Child of San Michele in Borgo, a work by a follower of Tino di Camaino, now known to be Lupo di Francesco (fig. 100). 13 The mistaken attribution of the Böhler Madonna was taken up in the essay by Volbach, published in 1925 in the Münchner Jahrbuch für bildende Kunst, 14 mainly devoted to the Ettal Madonna:

If we observe the other works of Tino as well as the forementioned Madonnas, the likelihood increases that the paternity of the Ettal Madonna be his. We find similar features in his first standing Madonnas in the Civic Museum in Turin and in the Böhler Collection in Munich. 15

In his essay Volbach attributed the Ettal Madonna and Child to Tino di Camaino, and compared the Turin Madonna stylistically to the Böhler one (fig. 1 and fig. 86). In his overview of Tino’s works, Volbach dated the Ettal Madonna, at the centre of this stylistic group of Madonnas that included the Böhler statuette, to about 1320. 16

The reasons for this ‘suspension of judgement’ about a sculpture of such high scholarly interest could be multiple. It is possible that the dealer Julius Böhler wanted jealously to conserve the sculptural group in his family collection, in those very years when he was intent on consolidating his position as connoisseur and art dealer on the international scene, together with his eldest son Julius Wilhelm.

Julius Böhler was the eighth child of a family of craftsmen, and was born in 1860 at Schmalenberg near St Blasien in the Black Forest. In 1880 at the age of twenty he acquired his first antique at Überlingen on Lake Constance, and it marked the foundation of his art gallery. 17 So the founder of the famous firm was selftaught. In 1883 he married Maria Loibl, by whom he had two more sons after the first-born, Otto Alfons and Wilhelm. 18

Between 1902 and 1904 (the year he bought the Madonna from the collection of Léon de Somzée, (fig. 1) Julius Böhler, at the peak of his success as a dealer, commissioned from the architect Gabriel von Seidl a building to house his art gallery in the elegant Brienner Straße in Munich (fig. 2), where he also set up his private collection, which undoubtedly included the statuette in question (fig. 1). 19 Subsequently, his son Julius Wilhelm, after a long period of apprenticeship in Paris and London, in 1920 founded together with his friend Fritz Steinmeyer an art gallery in Lucerne, continuing to keep the Madonna and Child secret as a private work belonging to the family. Julius cultivated in particular his interest in Gothic statuary whereas his eldest son, Lulu, preferred paintings and drawings, and for this reason had little interest in sculpture. 20

From 1913 in fact Lulu Böhler and Fritz Steinmeyer moved to the USA, where they came into contact with the art dealer Duveen and the collectors Isabella Stewart Gardener and Philip Lehman. In these circumstances they had success in selling, to leading European museums, some extraordinary paintings such as two landscapes: one by Philips Koninck to the Munich Pinakothek and one by Rubens to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin. 21 Julius Böhler died in 1934. Over the four decades following the acquisition of the Madonna, the sculpture remained practically inaccessible to scholars in the Böhler family collection in Munich. 22

Another reason that could explain this long silence might have been a certain prudence, due to the strange incongruency of the head, perhaps fifteenth-century or even nineteenthcentury, in relation to the Gothic sculpture (figs. 1, 6-10). Such indecision was aggravated also by Bode’s refusal to purchase the sculpture for the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, even though in the early years of the twentieth century he had renewed his interest in the sculptures of Nicola and Giovanni Pisano. 23 There exists however a strange and curious parallel between the careers of Bode and Böhler, which had its beginning in the 1890s and was based on some precise connections, albeit at a distance, between the two connoisseurs and collectors.

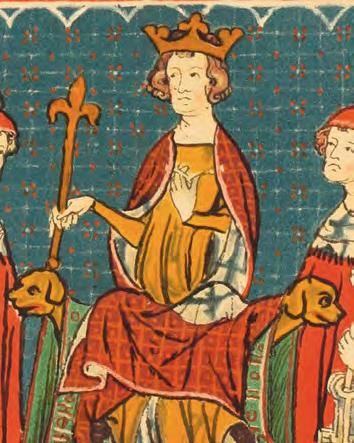

When in 1895 Julius Böhler became Kaiserlich-Königlicher Hofantiquar (fig. 3), one year later, on 6 May 1896, by a decree of the Emperor Wilhelm II of Prussia, construction began on the Renaissance Museum in Berlin, which was inaugurated as the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in 1904 (fig. 11). In that year work on the construction of the Böhler building in Munich, begun in 1902, was finished (fig. 2). 24 The Madonna from the Somzée Collection was purchased in 1904, and in the following year Julius Böhler was made Königlich-Bayerischer Hofantiquar (fig. 4). 25 In 1875 Bode had begun to collect the masterpieces that two decades later would form the nucleus of the sculpture collection of the Renaissance-Museum (figs. 5, 11), concentrating mainly on the Italian Renaissance. So it seems significant that some of the works acquired in 1881 by Bode were the Imago Pietatis and the Madonna and Child, both by Giovanni Pisano. In this context however it seems strange that Bode, who between 1901 and 1905 had devoted himself to collecting sculptures of the Italian Gothic – choosing in particular the Archangel Gabriel by Nicola Pisano from the pulpit of Siena Cathedral, the Dormitio Virginis by Arnolfo from the façade of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, the Sibyls from the pulpit of Pisa Cathedral and the wooden Crucifix by Giovanni Pisano – should not have expressed his opinion officially on the Böhler Madonna, nor have made the slightest attempt to acquire it. 26

To understand the nature of this strange insecurity of the critics, we need to comprehend the basis for the art historians’ opinions previously expressed. In the early decades of the twentieth century, in addition to the Böhler Madonna, the sculptures of the Madonna and Child known to be works by Giovanni Pisano and Tino di Camaino were three: the Berlin Madonna (fig. 55), attributed by Bode to Giovanni Pisano and by Venturi and Volbach to Tino; 27 the Madonna of the Girdle in Prato by Giovanni (fig. 51); and, in the circle of works by Pisano’s famous pupil, the d’Azeglio Madonna (fig. 86), since the late nineteenth century conserved at the Civic Museum in Turin. In the light of this restricted group of works, critics of the early decades of the twentieth century wrongly saw the Turin Madonna (fig. 86) as the model for the Böhler Madonna (figs. 1, 6-10). Following a long period when scholars paid no attention to the sculpture, for the first time Max Seidel in 1972, in an article in the journal Pantheon on the Berlin Madonna, 28 evaluated the Böhler statue in the context of the group of headless Madonnas of the ‘school of Giovanni Pisano’ –which includes the Madonna in the museum of Sant’Agostino in Genoa (fig. 46), the headless Madonna in Pisa that was originally part of the Lasinio Collection at the Camposanto (fig. 43) and the one in the Museum of Fine Arts di Boston – attributing it to this ambit of the master. Subsequently Seidel, in the 1987 catalogue of the exhibition ‘Giovanni Pisano a Genova’, clearly corrected the models of comparison, identifying the Berlin Madonna (fig. 55), with the imperial crown, and the headless Madonna in the museum of Sant’Agostino in Genoa (fig. 46) as the principal reference models for the stylistic identification of the Böhler statuette. 29

Prompted by a request for an expertise on the work on the part of the dealer Florian Eitle-Böhler, we took the opportunity to examine the statuette in greater depth, on the basis of new stylistic comparisons with works by Giovanni Pisano, distinguishing them from those created by Tino in a style that pays homage to his master, as for example the Turin Madonna. Starting from the awareness that it was an excellent masterpiece by Giovanni Pisano (figs. 6-10), we demonstrated that this sculpture belongs to his period as court artist to Emperor Henry VII, in the years 1312-1313. This demonstration was made possible by concentrating on five basic problems, with the aim of resolving the stylistic question and that of the statuette’s historical-political significance. To understand this sculpture in the history of collecting, we studied the typology and character of the collection formed by Léon de Somzée, who owned the statuette until it was acquired by the Munich dealer. In the singular figure of this industrial gas magnate, who accumulated works of art in his house in Brussels, we discovered the profile of a collector hitherto unknown to art criticism, following his development from amateur purchasing en masse to collector well aware of the historical value of his acquisitions.

We devoted ourselves to studying the sculpture in its two stylistic components. Given that the body, from the very first glance, appeared to be unequivocally by Giovanni Pisano (figs. 6-10), we formulated a hypothetical reconstruction of the statuette’s original appearance, taking the head of the Prato Madonna as a model (figs. 31-32). A particular study regarded the fifteenth-century head: we were able to demonstrate that it is

by Benedetto da Maiano and belonged originally to this sculpture, dating the head to around 1490 (figs. 22-26). This allowed us to discover something utterly unprecedented: the dialogue that took place between a famous renaissance artist and Giovanni Pisano, adjusting his own work to the Gothic masterpiece. Thanks to X-rays of the work, it has moreover been possible to shed light on the history of the head’s restoration, not only in the fifteenth century but also in the early twentieth, after Julius Böhler acquired it (figs. 37-40).

By widening the stylistic comparisons with other works by Giovanni, on the basis of new photographic documentation, including the headless Madonna in Pisa at the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo (fig. 43) and the one in Genoa in the Museo di Sant’Agostino (fig. 41), discovered in 1987, 30 both unknown to Volbach and Venturi, 31 we have been able to develop innovative paragons that demonstrate not only the high quality of the Böhler Madonna, but also its place among the works created by Giovanni in the years 1312 and 1313. Following this line of research, we discovered that in the fourteenth century the Böhler Madonna was so famous and venerated that it became the model for the Madonna of San Michele in Borgo in Pisa, by Lupo di Francesco, (figs. 100-101) and for the Madonna in Piombino signed by Marco and Ciolo da Siena (fig. 104), both of them dating from around 1320. On the basis of these new stylistic comparisons we have proposed a dating to around 1313 for the Böhler Madonna and have clarified the provenance of the original location in the city of Pisa.

A wholly unexpected fascination emanates from the history of the Böhler Madonna (fig. 1) in collections, dating from the activities of the first collector, the industrial gas magnate Léon de Somzée, who was an homo politicus, according to the typically late-nineteenth-century definition given by Paul Valery, though today we would probably say that he was a politically influential person on account of his great wealth. Born Léon Mathieu Henri in Liège in 1837, he took his doctorate in engineering in that city in 1862. 32

After his first industrial missions to Spain and Portugal, he was in Italy for the first time between 1862 and 1863 as the emissary of the mining engineers Caroline. 33 It must have been during this first sojourn in Italy that the rich industrialist became strongly attracted to collecting, encouraged by his considerable economic means and by a desire to create an enduring name for himself. This is extremely characteristic of a personality endowed with a high conception of his own destiny, for which he envisaged a great social and political future. This period of about one year spent in Italy must have been too brief for the young Somzée to complete the first acquisitions for his future art collection. So it was during his work as director-general of the Italian gas industry, between 1864 and 1867, that he was able to spend about four years in Italy that were to prove decisive for the formation of his collection; in time it would include works of art of every kind: sculptures, paintings and Belgian tapestries. In all likelihood the Madonna and Child, now part of the Böhler Collection, was acquired during this very period in Rome. From the 1860s dates the first plaster bust of Léon de Somzée that is known to us (fig. 12). It was the sculptor Charles Auguste Fraikin (1817-1893) who portrayed him as a young man, with an elegant coat open to show a silk waistcoat, typical of the dandy fashions of the later nineteenth century. The face is crowned by hair parted in the centre, exalting the open gaze staring thoughtfully into the distance, while the pursed lips are surmounted with a flowing moustache, highly fashionable at the time.

The rampant advancement of Somzée’s career in the gas industry, that emerged as the new source of energy in parallel with inventions in the field of electro-magnetism, was accompanied by the gradual formation of a personality that influenced the economies of many European countries. After his prestigious post in Italy, Somzée was head engineer at the Compagnie pour l’Eclairage et le Chauffage par le Gaz in Belgium from 1867 to 1871, while from 1886 he was director of the gas industry in the city of Brussels. 34 This pioneering role, which favoured the spread of an energy source destined to revolutionise society in a wave of heady economic expansion, allowed him to influence political relations between the European countries. From 1884 to 1892 he was a member of the Belgian Parliament, representing the Brussels district, and his mandate was renewed from 1896 to 1900. 35 In the same years, around the time of the great Exposition Universelle in Paris (1900), Somzée was President of the Association Royale des Ingénieurs Industriels. 36

This homo novus reconciled in his overweening ambition his dream of becoming a great art collector with that of influencing industry and politics. This double and specular aspect of Somzée appears not only from the considerable number of international societies that recognised him as a member, such as the Société Générale Internationale d’Eclairage in Belgium and the Société de Pétrole de Grosny in Russia, or as president, such as the Société Impériale Ottomane d’Eclairage, but also from his membership of the Société Royale d’Archéologie de Bruxelles, something he undoubtedly owed to his reputation as a feverish collector. 37 It seems significant of Somzée’s approach to collecting and of his scarce connoisseurship, dominated by a certain fin de siècle eclecticism, that among his publications there is not a single art-historical study or one dealing with works of art.

From his first book, published in 1878 on submarine communication between Britain and France, to his last, published in 1900 and entitled Chemin de fer pour de grandes vitesses, his writings dealt with the new technologies. 38

In the light of these formative experiences, it appears clear that his role as collector began with the idea of creating for himself the image of a man who has achieved his own rebirth and his fame on the threshold of the modern world, thanks to his staggering wealth and by surrounding himself with works of art that augmented his social prestige. This is confirmed by a glance at the second portrait of Somzée, showing him in his maturity (fig. 13). It is a bronze bust made in the late nineteenth century, undoubtedly before his death in 1901. The face no longer appears somewhat overshadowed with as yet unrealised thoughts, but is illuminated with a placid smile, expressing all the sensibility and determination with which the great politician and collector experienced the dawning of the modern age in Europe. The wavy hair and upturned moustache give vitality to the otherwise calm and lively gaze. Unlike the fashionable clothing worn in the first portrait (fig. 12), lacking the decorations that would proclaim his distinctive political importance, in this bust jacket and shirt are adorned with no fewer than four medals (fig. 13). Moreover the sculptor took the trouble to exalt the value of his sitter, alluding vaguely to the iconography of Roman busts, as appears from the tunic-like drapery, which was not part of nineteenth-century fashion, and

from the medallion sculpted on the base of the bust, vaguely recalling the bronze medals that were inserted into busts in antiquity. The work was commissioned to the sculptor Josef Lambeaux (1852-1908), who signed it on the back, and is part of a ‘gallery of busts of illustrious men’ of the nineteenth and twentieth century in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Liège.

The Somzée Collection originated in the early 1860s, between 1862 and 1864, and it was undoubtedly shaped during Léon’s long sojourn in Italy that ended in 1867, given that antique and Italian works of art always constituted the major nucleus of the collection. Until his death in 1901, Somzée devoted himself indefatigably to the minutiae of displaying an astonishing quantity of art works in his house in Brussels.

Thanks to our research in the archives of the department of architectural patrimony and town planning for the region of Brussels, we have been able to trace an image and the exact address of what in the late nineteenth century was known as the Maison Somzée (fig. 14). 39 It is a document earlier than 1908 and very important, because it completes the photographic documentation of some rooms in the house that we can admire in the initial pages of the catalogue for the auction of the entire collection that took place in Brussels on 24 May 1904 (figs. 15, 20). 40 The majestic Palais Somzée stood at number 22 (now 46)

Rue des Palais in the Belgian capital. This street was one of the branches of the tracé royal, built in 1820 together with Rue Royale and Avenue de la Reine. 41 In particular, Rue des Palais owed it name to the presence of two royal residences, and was distinguished not only by the houses of the upper middle classes but also by hôtels in the neoclassical style, first of all the Hôtel Somzée. 42 In the rare photograph of the Schaerbeek quarter (fig. 14) we notice how the viewpoint of the photographer coincides with Place Jules de Trooz and takes in, among the passers-by, some children who on the left are playing in the street at hoop and stick, while on the right four little girls and a man in a bowler hat are observing the proceedings with interest. The children probably belonged to the Institute Sainte-Marie, originally a home for deaf-mutes that was demolished in 1908, which we recognise in the large building on the corner, surrounded by a wall protecting a little garden with a row of leafless trees. The street still has a religious building, the Église Saint-Nicolas de Myre, though unfortunately it is not visible in the photograph. Only two buildings stand between the Institute and the Hôtel Somzée, which in an inventory is defined as an ‘imposante demeure d’un collectioneur d’art’. 43 Despite the considerable distance from the camera and the transverse viewpoint, we can clearly see that the house is articulated with three orders of windows, eight on the ground floor with the entrance doorway in the centre, and nine on the first and second floor. The architectural model emulates in a late-nineteenth-century neoclassical style the elements of the Italian renaissance palazzi, which the collector had undoubtedly admired during his stay in Rome, in particular Palazzo Farnese by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Palazzo Barberini by Carlo Maderno, which from a residence became a museum. We note in the Belgian house architectural elements typical of these Italian palazzi, such as the rustication on the ground floor of the façade and the aedicules of the rectangular windows on the first floor, against the smooth intonaco of the walls, separated by a string- course. The mingling with the nineteenth-century neoclassical style can be seen in particular in the frieze that runs beneath the eaves, though

unfortunately the photograph is not clear enough to show the details or identify its iconography. We do not know the date of the house’s demolition, but it is possible that it took place in 1908, four years after the auction and in the same year as the demolition of the adjacent buildings.

Hôtel Somzée contained a vast and eclectic collection of works of art. This house was part of Somzée’s collecting project and his favourite place, constructed ad hoc, for the scenographic display of his art works. His home was therefore an exhibition space that acquired the value of a private art gallery, open only to a few chosen connoisseurs and to his intimate friends. As is shown in one of the rare photographs of the interior published in the 1904 auction catalogue (fig. 15), the building must have been carefully designed by Somzée and its internal spaces transformed by him so as to create a gallery for the mixed genres of his mirabilia: paintings, sculptures, tapestries and small objets d'art. 44 The eclectic heaping up of the collection follows for the most part a certain Wunderkammer taste, articulating the pieces in accordance with the monumental scenography of the salon, lit during the day by a large skylight. From the ceiling hung two splendid lamps decorated with glass foliage, as well as a number of oil and gas lights. These latter bore witness not only to the successful career of the engineer Somzée but also to the advanced technology in his house at the dawning of the modern age. The sculptures and a male bust at the sides of the vast salon are arranged with regular cadence in correspondence with columns similar to the Corinthian order; each of the four columns presents a particular stylistic mingling: in the upper part of the enthasis, evidenced by a cornice, we note Doric fluting while the lower part has figured reliefs with grotesques and panoplies. Each column is detached from the wall so as to create round-arched niches, in which were paintings of various subjects. To reinforce the centre of the salon, in axis with the monumental arched entrance opening onto a room similar in perspective, we note two sculptures not easily legible, with antique vases and porphyry urns in the intervals: one of them might represent Venus, Daphne or la Source, while the other is a headless fragment of a Roman copy of a Kouros of the fourth century BC. Small art objects and more delicate items, such as a rare collection of painted fans, are displayed in glass cases in the centre and at the sides of the room. In this building the rooms recall, in the arrangement of the columns and in the almost basilican conception of space, the rooms of Palazzo Farnese in Rome, revealing that the idea of the project was that of a rich and vast family collection, intended to form a private gallery in honour of the glory of its founder and of his family.

The arrangement of the art works in the majestic building in Rue des Palais in Brussels reveals the outlook of an amateur collector, not yet flanked by an expert art historian. Not until the mid-1890s did Somzée entrust his collection of Greek and Roman antiquities to the archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler (1854-1907), who had taken part in the excavations at Olympia in Greece and in 1880 had collaborated on the creation of the Antikensammlung in Berlin, where he was appointed professor in 1884. 45 Later, after being awarded the chair at Munich in 1894, Furtwängler took part in the excavations on the island of Egina and at the city of Orcomenos in the Peloponnese. 46 It is especially interesting that the father of the future conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler (18861954) was employed on the scholarly arrangement of the Somzée Collection a few years after the publication in 1893 of the book Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik, while between 1900 and 1904 the archaeologist would publish in several volumes his study of Greek vase painting, Griechische Vasenmalerei 47

The work of study and scholarly arrangement carried out by the famous archaeologist was determinant for the value of the collection of antiquities and shows Somzée’s urgent desire to confer order on his collection, with the idea not only of making the more prestigious works emerge but also of making them comprehensible in scholarly terms in accordance with a correct art-historical perspective. In 1897 Adolf Furtwängler published in Munich the first catalogue of the Somzée collection entitled Antike Kunstdenkmäler (fig. 17) 48 In the introduction that the archaeologist wrote as a premise to the arrangement of the collection illustrated in the 1897 catalogue, we find the declaration of those principles at the basis of the transformation of Somzée’s eclectic dilettante holding into a compact art collection limpidly selected, in which each object is displayed in accordance with precise art-historical criteria. 49 Furtwängler traces the acquisitions to the gardens and courtyards of villas belonging to Rome’s patrician families, discovering sculptures still unknown to archaeologists. 50 From a careful analysis of the provenances in the catalogue, we note that no fewer than twenty-two sculptures have a Roman provenance: in particular, fourteen from the Ludovisi Collection, six from Palazzo Sciarra, five from an unspecified Roman Collection, one from Palazzo Rospigliosi, four from the Demidoff Collection and two from Villa Casali. 51 To this list we can add a sculpture from Palazzo Soderini in Florence and another one from the collection of a Polish count in Brussels. 52 The archaeologist took care to emphasise that it was Somzée’s idea to correct the dilettante aspect of

the collection by means of an accurate study of provenance and of scholarly cataloguing. 53

The archaeologist also declared that it was his choice to remove from the sculptures most of the later restorations and integrations, and to interest himself also in Roman copies as evidence of the lost Greek bronzes. 54 In the 1897 catalogue, Furtwängler took the trouble both to indicate the later integrations and to explain their removal. For example, regarding a ‘Torso of a youth in the style of Polykleitos’ he declares that ‘the earlier additions have been removed’, 55 while regarding a ‘Torso of Antinoos’ from the Villa Ludovisi in Rome together with a torso of Poseidon originally from the Baths of Caracalla, he states that he saw it with a head of the Apollo Belvedere type and with the right arm added, while it now lacked both the added limb and the plinth. 56 The conscientious archaeologist did not fail, in the case of a ‘Torso of Apollo’ from the Ludovisi collection, to note both its original components and its later integrations: ‘the stele with the serpent beside two sandalled feet is antique, although not attached. The lower part of the legs from knee to ankle is an integration. The other additions have now been removed.’ 57 In the light of this ‘purist’ choice regarding interventions, which were mostly renaissance or eighteenth- to nineteenth-century, it seems clear that the scholarly work of Furtwängler, or of his successor, did not extend to include the collection of thirteenth- to seventeenth-century sculpture, because otherwise the Madonna and Child, now in the Böhler collection, would be lacking the head made for it by Benedetto da Maiano, which is an important stylistic witness to the dialogue between the renaissance artist and Giovanni Pisano.

In the catalogue of the collection of antiquities drawn up by Furtwängler there is a photograph of the display of works selected by the archaeologist at the Hôtel Somzée in Brussels (fig. 16). Observing this photograph and comparing it with the one of

the room with the collection of sculptures, paintings and objets d’art (fig. 15), it seems clear not only that the collection of antiquities is distinct for chronology from the vast number of remaining works of art but also that Somzée was guided and educated by the German archaeologist towards a selected and aware form of collecting, in the stylistic distinctions and in the quality and historical importance of the works on display The imposing colonnaded room with coffered ceiling and a window opening onto the internal courtyard, presents works arranged according to subject and chronology. We note in the layout an attempt to astonish the viewer by the sumptuous nature of the collection, which includes many fragments of torsos and busts, and two centaurs. The articulation of the plinths in respect of the architectural space is the result of a careful choice, which places in the centre of attention the most significant work in the room: a colossal statue of a young man in a helmet, from the gardens of Villa Ludovisi. 58 So the display choices, no longer eclectic and inconsistent, indicate the pre-eminent works as identified by art-historical study. Although the sculpture appears complete in the photograph, Furtwängler specifies that the lower part of the right and left leg, the right foot, the penis, the nose and part of the neck are integrations. 59 The work is the only known copy of a lost Greek original of the earlier fifth century BC, and the only copy that shows an Oplitodromos by the sculptor and painter Mikou, a contemporary of Kalamides and Polygnotus. 60

The fame and fortune of the Somzée Collection grew in parallel with the scholarly study and ordering of the works. Around the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the owner celebrated the achievement of his fame both as a learned collector and as a European politician and industrialist. At the dawn of the new century, which opened novel horizons for the electrical inventions of the modern age and for new sources of energy, Somzée presented himself at the great Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 with a collection of works of art in the Belgian pavilion (fig. 18) – unfortunately the Böhler Madonna was not among the sculptures on display. 61

The rearrangement of the collection was in fact begun by Somzée starting from the works he esteemed most highly, i.e. those of classical antiquity, as is confirmed by the fact that at the Paris Exposition he almost exclusively displayed antiquities. 62 In 1901 death interrupted this project of the cataloguing of the collection, which would undoubtedly have eventually involved the sculptures considered to date from the sixteenth and seventeenth century.

On 24 May 1904 at number 22 Rue des Palais the entire collection of Léon de Somzée, comprising 2,050 works, was sold at auction, given that no member of the family was interested in conserving the patrimony of the far-sighted collector (fig. 20). 63 It was the first time that the Madonna and Child was displayed to the general public, and on this occasion the purchaser was the famous Kaiserlich-Königlicher Hofantiquar Julius Böhler of Munich.

In the auction catalogue edited by J. Fievez of Brussels, plate XCIII is a photograph showing exactly how the Böhler Madonna was displayed at the time of the sale, together with some other sculptures (figs. 19, 21). 64 The display takes no account of the different styles of the statues, nor of their subject, nor of their dating. They appear in a frontal position, some on specially made plinths, so as to create a sort of harmonious arrangement of the heights of the two symmetrical parts of the group; the height of the sculptures varies between 45 and 60.5 cm. The Böhler Madonna (catalogued as number 1421) is also placed on a nonoriginal plinth, which raises it symmetrically in relation to the Virgin and Child numbered 1418 (fig. 19). So the presentation privileges a balance in the formal proportions, as is shown by the insertion at the sides of the sequence of five central sculptures of two putti-telemons supporting shell-like bases, defined by the catalogue as ‘travail florentin du XV siècle’ and exhibited at the Exposition d’art Ancien at Brussels in 1888. 65

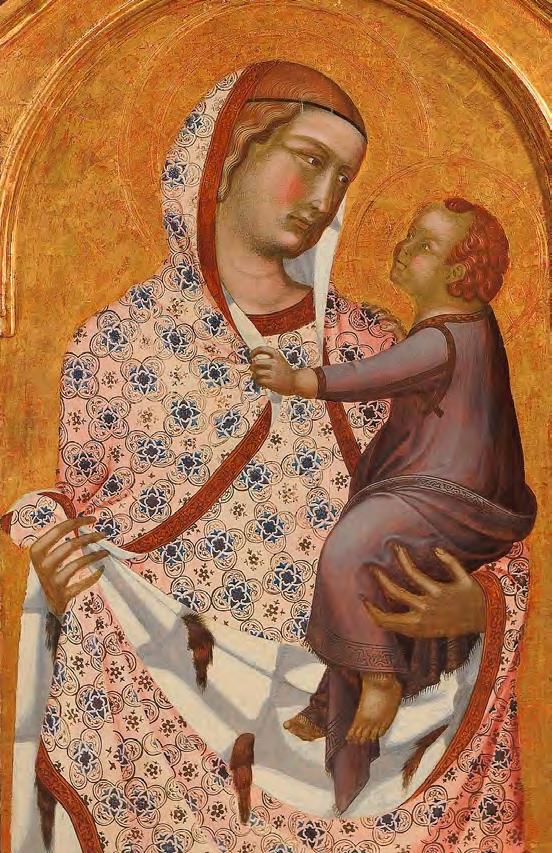

Eclectic late-nineteenth-century taste prevails over any idea of historical or scholarly arrangement, and for this reason both the attributions and the dating leave much to be desired. One of the two best-loved works according to the taste of the time is the Virgin and Child identified as number 1418 (fig. 19), called a ‘belle œuvre, finement ciselée et de beaucoup de sentiment’, is attributed to the sculptor Nicola Pisano and dated to the sixteenth century. 66 The later Nicola Pisano was however exclusively a painter who was born in 1434 and died in 1538, son of Bartolomeo da Brugia. 67 This same attributional superficiality is found in the case of the central sculpture of the Virgin in prayer, praised for the drapery and newly attributed to the same Nicola Pisano. 68

The second work of the two best loved is a statuette of the Virgin and Child described at number 1420 (fig. 19) as a very beautiful piece with remarkable drapery and expression. Admiration for this sculpture must have been such that it was in the Exposition Universelle at Paris in 1900. 69 The David with the head of Goliath, next to the Böhler Madonna, is the only sculpture in terracotta, said to be Florentine work of the early fifteenth century and attributed in the catalogue to Lorenzo Ghiberti. 70

The future Böhler Madonna was presented at number 1421 with a single brief line in the catalogue: ‘Statuette en marbre blanc de la Vierge avec l’Enfant Jésus. Travail italien, XVII siècle. Hauteur, sans le socle, 0.60’. 71 As an example of the taste of the time, which conditioned critical judgements on the style of the works without understanding them deeply in historical and scholarly terms, we note that the Böhler Madonna is not praised like the other two Virgins of the group, nor is it appreciated for its drapery and movement. The work, which in the catalogue photograph reveals gilding on the fringes of the cloak, on the girdle and at the base of the Child’s neck, because of Somzée’s lack of appreciation was never sent by him to any exhibition, unlike the other three works visible in the photograph. Lack of understanding of the work’s great art historical value is evident too in the catalogue entry on the Böhler Madonna where no reference is made to the evident stylistic disparity between the renaissance head and the Gothic statuette. Unfortunately we do not know the prices attained at the auction but we may surmise that the price of the Böhler Madonna was very low, to the advantage of its new owner Julius Böhler who with this acquisition showed himself to be an excellent connoisseur.

The stylistic disparity between the head and the body of the Böhler Madonna turns out to be one of the most intriguing problems in the understanding of the statuette, given that it long irritated the art historians and hindered their judgement in identifying the work as a sculpture by Giovanni Pisano (figs. 1, 6-10, 24-26). With a view to resolving the problem implicit in such a disparity, we have formulated four hypotheses.

The first hypothesis is that the head in question is a fake, especially made in the circle of Roman art dealers between 1864 and 1867, i.e. in the arc of time when the magnate-collector Léon de Somzée acquired the sculpture in Rome together with an enormous number of works of art of the Roman period, sold by the city’s old noble families. The hypothesis of a nineteenthcentury head emerged also from the fact that Somzée, not being an expert connoisseur who carefully selected works for his own collection, lacked art-historical advisors (this was before the intervention of the archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler) and for this reason was unable to distinguish a nineteenth-century forgery from an original.

Secondly, we considered the hypothesis that a fifteenthcentury head was mounted onto the sculpture by some art dealer in preparation for its being acquired by Somzée in Rome. The third hypothesis, linked indirectly to the fourth, is based on an attribution of the head to the Tuscan sculptor Benedetto da Maiano (fig. 24). The 1931 and 1967 typewritten inventories of the Böhler Collection report that Wilhelm von Bode had informally, and probably voce dictu, identified in the head the style of Benedetto da Maiano. 72

Lastly, the fourth hypothesis is that the head was made by Benedetto da Maiano for this very sculpture by Giovanni Pisano, which had been left headless after a brutal fall. So this would be a very rare example of an integrative restoration in the 1480s of a fourteenth-century sculpture presumably much admired as an object of veneration and devotion.

To demonstrate that this is an original head sculpted by Benedetto da Maiano, we relied on the professional opinion of Francesco Caglioti, the eminent connoisseur of fifteenth-century Tuscan sculpture, who completely agrees with our analysis as set out here. We wish to illustrate the attribution of the head to the Tuscan sculptor, initially presenting two stylistic comparisons with two famous works by Benedetto da Maiano: the delicate face of the Madonna and Child in the roundel sculpted in relief to crown the tomb of Maria d’Aragona in the church of Sant’Anna dei Lombardi in Naples (fig. 22) and the head of the Madonna and Child known as ‘of the Snows’ in the church of Santa Maria Assunta e Sant’Elia at Terranova Sappo Minulio (fig. 23).

Observing the head of the Böhler Madonna, and comparing it with that of the Virgin in the roundel with seraphim surrounded by a festoon of fruit, (figs. 22, 24-25) we clearly recognise the common compositional traits in the oval of the face firmly supported by a neck worked with soft, subtle moulding and slightly inclined to give full effect to the fall, at the sides of the face, of the drapery on either side of the face. The folds of this veil are gathered into a point at the top of the head above the hair parting, as though alluding to a diadem. This slight but significant raising of the cloth delineates an ideal vertical axis that traces the parting, the nose, the lips and the rounded chin.

1 Today, only a small number of figures are to be seen.

2 Painted à la porcelaine, the stone sculptures would have had the appearance of painted china figures.

The limpid ovoid form is emphasised by the slight contrast with the locks of hair, in both sculptures three on each side, which fall in soft waves to cover the temples and part of the ears, and seem to lap against the quiet surface of the face. Both in the Neapolitan sculpture and in the Böhler one we observe the same compositional principle in the maximum harmony of the oval, where we admire the quiet expression and the intus that the artist has conferred on the figure.

From the softness of the Madonnas’ complexions there emerge unmistakeable traits of the figures sculpted by Benedetto (figs. 22, 24-25), not only for the almost imperceptible (were it not for the falling of the light on the arched profiles) eyebrows, but in particular for the subdued cut of the almond-shaped eyes. The lips seem sealed and defined by the dimples at the corners of the mouth. The lower lip can be read thanks to an indefinite passage of chiaroscuro given by the dimple on the chin, which like a well polished detail concludes the symmetrical oval of the face. Since the Madonna in the roundel on the Aragonese tomb is one of Benedetto’s supreme masterpieces, it is precisely this extremely high formal quality that allows us confidently to ascribe the head of the Böhler Madonna to the sculptor, in as much as the stylistic features, albeit of a slightly lower tone in the latter, are clearly identical.

The second stylistic comparison is between the head of the Böhler Madonna and that of the Madonna of the Snows in Terranova Sappo Minulio (figs. 23, 25-26), belonging to a series of Madonnas linked to Calabria in southern Italy. It reveals how the stylistic features proper to the Tuscan sculptor are present also in the face of the Böhler Virgin. As in the case of the head of the Madonna in the roundel on the tomb in Naples, we note that Benedetto in the case of the Böhler Madonna used a technique of working the marble in the round that is distinguished from the technique of sculpted relief, proper to the Madonna of the Snows (fig. 27).

Observing the face of the Madonna of Sappo Minulio and that of the Böhler Virgin, we are aware of a greater stylistic quality in the latter although the stylistic motifs have much in common, among them being the composition of the oval motif of the face, positioned in axis with the slender neck (figs. 23, 26). Very similar in both sculptures is the appearance of the eyes beneath the half-closed lids, and the eyebrows perceptible only from a slight hollow in the marble. The expression changes imperceptibly between the two faces: the lips of the Madonna of the Snows appear thin and firm in an icastic smile, while those of the Böhler

Virgin smile delicately. With subtle ability Benedetto maintains the stylistic feature, slightly changing the form so as to adapt the barely hinted smile of the Madonna of the Snows, who does not look at her Son, into the contained movement of empathetic sentiment of the Böhler Madonna who is engaged in a visual dialogue with the Christ Child. In the formulation of the soft and wavy locks of hair, Benedetto expresses himself in the customary central division, which emphasises the oval of the face while partly concealing the ears. The veil appears in this comparison similar in its arrangement, with the same folding into ‘diadem-like’ pleats, although that of the Calabrian sculpture presents a piercing at the edge of the cloak in contact with the locks of hair. While in the Böhler Madonna the veil falls at the sides of the face, timidly alluding to the emphatic movement of the body in the original fourteenth-century sculpture, in the Madonna of Sappo Minulio on the other hand it is slight breeze that disturbs the folds falling at the sides of the Virgin’s face, distending the pleats at the sides.

In the light of these comparisons, we can affirm that the head of the Böhler Madonna is unquestionably an authentic and high-quality work by Benedetto da Maiano. As for the dating, the arc of time in which Benedetto made the head for the Böhler Madonna can be deduced with a certain accuracy from the documented chronology of the funerary monument to Maria d’Aragona and of the Madonna and Child of Terranova Sappo Minulio.

It was Antonio Piccolomini Todeschini, duke of Amalfi, nephew of Pius II and consort of Maria d’Aragona, who set up the funerary monument to his wife, natural daughter of King Ferrante of Naples. 73 As is attested also by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the artists, the cenotaph was commissioned from Antonio Rossellino, who died in 1479 leaving the work unfinished. 74 In this connexion we have a Procura document dated 18 July 1481, in which Antonio Piccolomini authorises the abbot of San Miniato to claim the sum of 50 florins from the heirs of Antonio Rossellino, given that the latter’s death had interrupted the commission. 75 On 10 March 1490/1491 a document attests that Antonio Piccolomini paid 100 florins to Benedetto da Maiano, confirming that the Tuscan sculptor worked on the monument to Maria d’Aragona, completing what was left unfinished by Antonio Rossellino. 76 The extraordinary quality of the roundel with the Madonna and Child, and the evident stylistic features of the figures, confirm that Benedetto da Maiano planned this relief to complete the monument begun by Rossellino (fig. 22). So, taking the Procura document as terminus a quo, it follows that the image of the Virgin in the roundel was made shortly after 1481 (fig. 22). 77 The Madonna

of the Snows (figs. 23, 27), identified by Francesco Caglioti as a work of Benedetto da Maiano, 78 was originally conceived by the sculptor as the central part of an altar that was probably commissioned by Count Marino Curiale di Terranova. 79 The close stylistic similarity between the relief of Sappo Minulio and the altar of the Annunciation in Naples, for which 1489 is given as terminus ad quem, allows us to date the Madonna and Child of Sappo Minulio to around 1490 (figs. 23, 27). 80 From this chronological analysis of the two works by Benedetto, we can deduce with a certain degree of probability that the sculptor made the head for the Böhler Madonna at some time in the 1470s (figs. 24-26).

In Tuscan sculpture of the late fifteenth century it is fairly rare, as compared to the fourteenth century, to find statues of the Madonna and Child in a standing position. This motif, which was continually repeated in the Gothic period, rarely and only in particular cases was continued in the early Renaissance. Only a few examples of this type of Madonna have come down to us,

made in terracotta by the followers of Donatello. Jacopo della Quercia on the other hand recreated these themes from Gothic sculpture. Among the predecessors of Benedetto da Maiano, only Luca della Robbia made two standing Madonnas, though they were not in marble but in glazed terracotta.

Several scholars have attributed to Benedetto a small group of Madonnas – all more than a metre in height, standing, holding the Child – stylistically consistent, in the south of Italy, which perhaps derive from a devotional prototype. 81 Ascribed to Benedetto are not more than five marble statues of lifesized Madonna, all in Calabria and none of them commissioned for Florence or for elsewhere in Tuscany. 82 According to the studies of Doris Carl, the Madonna and Child of Morano Calabro, in the Collegiata della Maddalena, and the one of Amantea (fig. 28), in the church of San Bernardino da Siena, both derive from the celebrated Madonna di Nicotera (fig. 29), which has been an object of particular devotion ever since the birth of the legend that it arrived in a ‘wandering vessel’ and was found on the beach by the monk Paolo da Sinopoli, who set it up in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie.83

Fig. 27 Benedetto da Maiano, Madonna of the Snows, Terranova Sappo Minulio, church of Santa Maria Assunta e San Elia Fig. 28 Benedetto da Maiano, Madonna and Child, Amantea, church of San Bernardino da Siena Fig. 29 Antonello Gagini (or Benedetto da Maiano), Madonna and Child, Nicotera, CathedralIn particular, the Madonna di Morano Calabro is thought to be the first copy of the statue of Nicotera (fig. 29). 84 However in 2002 Francesco Caglioti identified the Madonna Nicotera (150 cm tall) as a youthful work by Antonello Gagini, dating from between 1498 and 1499 (fig. 29); in contrast he identified Benedetto’s typical stylistic features in the face and in the composition of the Madonna of the Snows (fig. 27), which however was not a statue but the central part of an altar sculpted in relief. 85

Lastly, if we consider that also the Madonna di Bombile at the Santuario della Madonna della Grotta presents a style very similar to that of the Madonnas of Nicotera (fig. 29) and of Morano Calabro, it seems clear that the number of standing Madonnas ascribable to Benedetto da Maiano shrinks perhaps to only one, i.e. the Madonna of the Snows (fig. 27), which however in comparison with the Böhler Madonna is not only much taller but is also not a statue in the round but a relief (figs. 1, 27). From these studies it is clear that on the nineteenth-century art market there was no head of a standing Madonna by Benedetto da Maiano with measurements suited to being attached to the Böhler Madonna, which was and is about 60.5 cm tall. Thus we may exclude the hypothesis of an arbitrary reassembling with a head by Benedetto.

In support of the thesis that we are not dealing with a fragmentary head of a standing Madonna by Benedetto attached in the nineteenth century – or even with a nineteenth-century fake used to complete the headless statue – , we should like to illustrate some details that provide proof of the integrative restoration that Benedetto skilfully operated by joining the head, which he had made, onto the fourteenth-century sculpture. The joining of the marble fits perfectly every component of the veil and neck of the original part; neither at the back nor at the front nor at the sides can be found any disjuncture or disarticulation, something that would be impossible had not the head been specifically made for this purpose. On the front we note how the pleats in the folds of the veil fall in perfect harmony with the fourteenth-century remains of the drapery sculpted by Giovanni Pisano, of which the lower left margin has been conserved, which turns behind the back, and that of the lower right margin which with two pleats cover the fold of the cloak, falling turned out at the breast. On the basis of these traces of drapery, Benedetto reconstructed the veiling of the head, worked with a slight disarticulation on the right side caused by the difficulty of recapturing the tension of the movement conferred by the neck on the head. Even more surprising is the study of the back of the head (fig. 40).

The softly channelled pleats of Benedetto’s veil seem vertically generated from the ones of the original drapery. In following the emphasis of the juxtaposition of the heavy cloth conceived by Giovanni, Benedetto widens the distance between the pleats and the braids so as to adapt the inclination of the head to the dialogue with the Child.

Integrative restoration of a work considered to have been of primary importance was in the Renaissance destined exclusively for the rediscovered works of Greek and Roman antiquity, and generally not for Gothic sculpture. In late-fifteenth-century Tuscany there exists no evidence for such an integrative restoration on the part of a celebrated sculptor like Benedetto da Maiano. Neither Donatello nor Verrocchio received commissions of this sort. This testimony is therefore not only an historical document of the greatest importance but it also shows how highly appreciated was a masterpiece by Giovanni Pisano in the later fifteenth century. It was undoubtedly an object of devotion and veneration, and it must have been famous if such an eminent sculptor as Benedetto was called upon to restore it.

The dialogue between Benedetto and Giovanni reveals an unexpected comparison between the art of the Renaissance and that of the Tuscan Gothic, attested by what is for us today an irritating stylistic juxtaposition, which however in the time of Benedetto was the fruit of a new sensitivity towards this period of the previous century (fig. 30).

To reconstruct a hypothesis of how the Böhler Madonna might have looked with its original head, we have created a photomontage that substitutes for Benedetto’s head the head of the Madonna and Child sculpted by Giovanni Pisano around 1312 for the Chapel of the Sacred Girdle in Prato Cathedral (figs. 30-32, 51, 56). The photographic juxtaposition was realised by tracing the profiles of the conjunction between the original and Benedetto’s head: these limits are clearly visible in the Böhler sculpture thanks to the discontinuity in the colour of the marble and to the different working of the surfaces on the part of the two artists. The insertion of the head of the Prato Madonna confers to the observer the idea of how the serpentine movement of the body was articulated in emphatic tension from the feet upwards, until the turn of the head culminating in the dialogue with the Child. To illustrate the hypothetical reconstruction of the sculpture, we propose two phases of the recomposition: the first (fig. 31) with a photographic apposition in which the head appears ‘in semi-transparency’

with a non-invasive tone, the second (fig. 32) with a genuine hypothetical reconstruction of the original appearance of Giovanni Pisano’s marble head.

When we compare this with the present arrangement of the sculpture including the head by Benedetto, it clearly appears how the symmetrical style of Benedetto’s harmonious and pure renaissance proportions does not coherently crown the serpentine Gothic of the taut and extremely expressive movement conceived by Giovanni (figs. 30-32). Benedetto da Maiano, admiring Giovanni’s work, attempted to enter into close dialogue with its expressive tension, integrating it with a magisterial

example of his own art, which however ended up by tempering the movement in torsion that, from the right knee, passes to the Madonna’s hand, opening up to the intense and quivering dialogue between Mother and Son. This desire of the artist to dialogue with the pose of Giovanni’s sculpture explains why the left part of the locks and veil appear unfinished (figs. 25-26), as though to privilege a viewpoint of the head that emphasised the visual dialogue between the Virgin and Christ.

In this rare example of a comparison between two epochs in the history of Italian art, the Gothic and the Renaissance find a point of conjunction in two famous artists united in an unprecedented dialogue, in the context of a single masterpiece.

Our demonstration that the head is a late-fifteenth-century work made by the famous Tuscan sculptor for Giovanni Pisano’s headless Madonna does not absolve us from the study of later re-elaborations, of which we have revealed traces by observing the present stuccoing, decisive in determining the current orientation of the Madonna’s face and its dialogue with her Son. This study arose from a comparison between the photograph of the Böhler sculpture taken on the occasion of the 1904 auction (fig. 33) and published in the catalogue of the sale of Léon de Somzée’s Collection (fig. 19), and a modern photograph of the work from the same orientation and viewpoint documented in the early-twentieth-century photograph (fig. 34). This comparison clearly reveals surprising and important, albeit minimal, differences in the position of the Madonna’s head, showing that the restoration and the correction of the fifteenth-century work’s incline are due to the art dealer Julius Böhler, after he acquired the work from the collection of Léon de Somzée.

Benedetto da Maiano’s head must have been very unstable and have undergone repeated interventions between the sixteenth and nineteenth century in order to reattach it to the fourteenth-century sculpture, for which it had been designed (figs. 33-34). However, after he acquired the statuette for his own collection, Julius Böhler decided on a definitive intervention so as to fix the head securely to the pre-existing sculpture. This restoration, which aimed not to alter Benedetto’s brilliant integrative restoration but to exalt the unique nature of this comparison between Gothic and Renaissance in a single masterpiece, made it necessary to use stucco to fix the neck and the veil both at the sides and at the back. It is however important to point out that the stucco did not cover Benedetto’s original junctures between the head and the fourteenth-century sculpture, as they perfectly follow the consistent stylistic flow of the pleats created by Benedetto.

Certainly Julius Böhler’s idea was to recuperate a more correct inclination of the Virgin’s face, so as to recapture as far as possible the original aspect and to emphasise the visual colloquy with Christ, given that the unstable position of the head during the Somzée ownership had led to a disarticulation of the pose that attenuated the intensity of the dialogue (figs. 32-34).

As is shown by a comparison between a modern photograph of the sculpture and the one taken in 1904, the head of the Child, which had also suffered a fall and had been reattached, did not undergo any change in orientation, confirming that the Böhler restoration affected only the head of the Madonna (figs. 33-34).

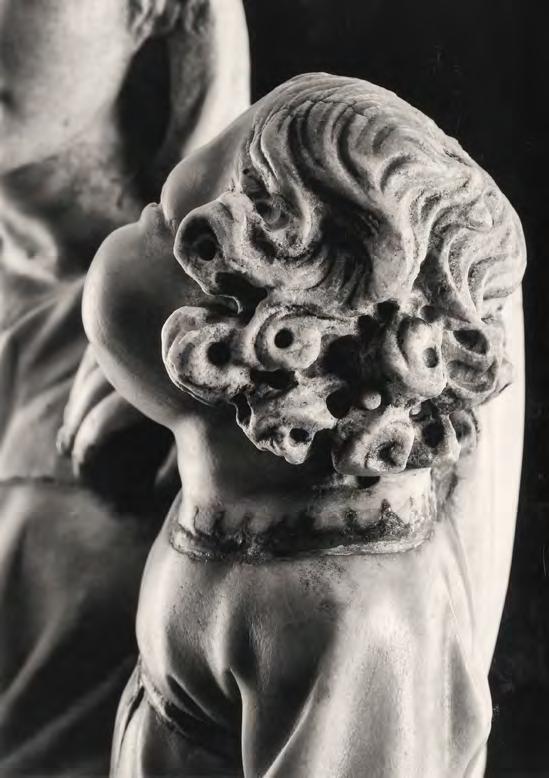

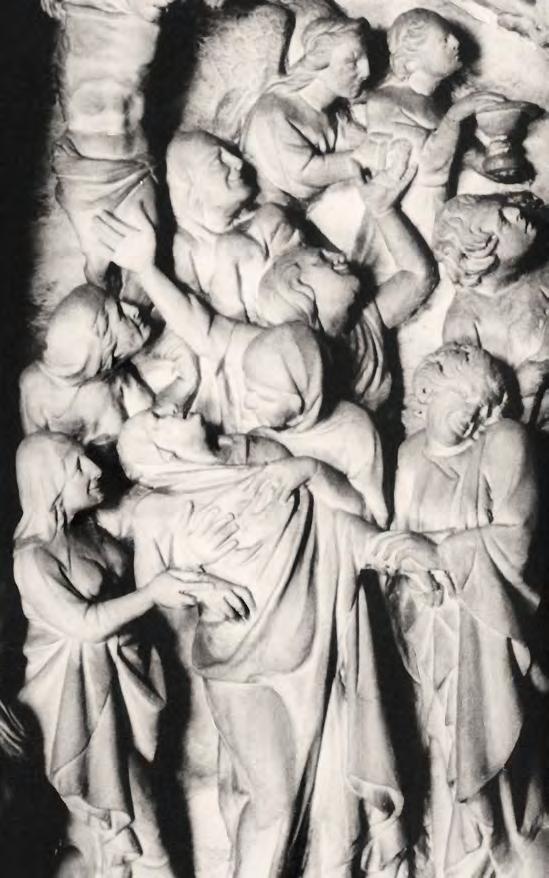

The head of the Christ Child is one of the supreme masterpieces of Giovanni Pisano (fig. 35). Although broken at the base of the neck, reattached in the fifteenth century and maintained thus by Léon de Somzée and by Julius Böhler, the head of the Böhler Christ Child is distinguished by a skilful working of the curly hair with the drill so as to convey rotundity on the frothy locks (figs. 34, 35). The face was sculpted by Giovanni Pisano in sideways profile, precisely so as to emphasise the Child’s smiling turn towards the Madonna, so as to capture the movement and almost the atmospheric sense of the space in which the Child moves. This is helped by the taut vibration of the rounded cheeks, the expressive creases around the eyes and the softness of the smooth partings in the hair curling around the nape of the neck. This creation of

the idea of the Child who in profile, in an instinctive movement, turns emphatically to fix his eyes on his Mother, is extremely similar to a detail in the relief showing the Massacre of the Innocents, sculpted by Giovanni Pisano for the pulpit of Pisa Cathedral (figs. 35-36). As we can tell by comparing the two children turning towards their own mothers, one in a moment of joyous colloquy and the other in tragic anguish, the expressive intensity that bursts from the skilful working of the curling locks and of the profile of the cheek, nose and eyes, is absolutely the same. This would confirm that the head of the Böhler Christ Child was authentically created by Giovanni Pisano within a few years of the masterpiece for Pisa Cathedral.

Thanks to recent X-rays of the Böhler sculpture, we have been able to observe how the reattachment of the head to the body took place (figs. 38-39). An initial comparison is that between a photograph of the profile of the sculpture’s bust and an X-ray of the sculpture’s profile taken from the opposite side (figs. 37-38).

The head was fixed to the base of the neck by a leaden dowel that extended vertically about half way between the head and the shoulders. In order to insert this reinforcing element, the restorer must have removed Benedetto’s head, thus losing the earlier stuccoing, after which he would have positioned the dowel and re-stuccoed the parts together. In radiography the stuccoing is visible in the horizontal band at the base of the neck. Moreover, the fact that the X-rays are so reflective reveals that it is prevalently composed of gesso and mortar. If we observe the photograph in consideration of this radiographic detail, we see how the Böhler stuccoing faithfully follows Benedetto’s original in correctly recomposing the pleats he sculpted with those of the drapery falling over the back, sculpted by Giovanni Pisano.

The X-ray photograph of the head and bust of the Böhler Madonna shows the position of the dowel in the centre of the neck (fig. 39). The X-rays of the left part of the veil falling from the forehead

demonstrate that, because of the repositioning of the head to recapture the correct orientation of the face, the surfaces of the drapery were stuccoed in order to fix the assemblage at the base of the veil falling over the shoulders. However it is the comparison between this X-ray with a photograph of the back of the Madonna that allows us to read the qualities of the Böhler restoration (figs. 39-40): no fifteenth-century part was altered, but only recomposed in optimum alignment so as to guarantee a solid fixing of the head. The X-ray photograph of the sculpture’s bust reveals that the head of the Christ Child was also consolidated by a leaden dowel inserted during the Böhler restoration (fig. 39). Our hypothesis on the early-twentieth-century conservative restoration is therefore confirmed also as regards the head of the Child, which was consolidated without altering its position, as is demonstrated by a comparison with the auction photograph of 1904, and was then stuccoed at the base of the neck (figs. 33-34, 39).

In the Museo Civico di Sant’Agostino in Genoa there is a statuette 47 cm high showing a headless Madonna (figs. 41, 46), now universally recognised as a masterpiece by Giovanni Pisano but unknown at the beginning of the last century both to Venturi and to Volbach, as emerges from their studies of the sculptures by Tino di Camaino and Giovanni Pisano. 86 Furthermore this statuette is mentioned, as a work of comparison for the stylistic understanding of the Böhler Madonna, neither in the two type-written catalogues of the Böhler Collection of 1931 and 1967 87 nor in those of the exhibition held at the Böhler gallery in Munich in 1958. 88 It was only five years later, in 1963, although the sculpture had been part for several decades of the old collection in the Museo Civico di Sant’Agostino, that the statuette was published by Caterina Marcenaro as a work originally belonging to the tomb of Margaret of Brabant by Giovanni Pisano, in the very years when Marcenaro was collaborating with the museologist Franco Albini on the new arrangement for the sculptural group of the elevatio animae, made for the funerary monument to the queen consort of the emperor Henry VII. 89

The work was again studied in the context of the 1987 exhibition ‘Giovanni Pisano a Genova’, and on that occasion underwent cleaning at the restoration department of the Vatican Museums (fig. 46) 90 This conservative intervention clarified that the marble of the statuette is different from that of the other sculptures on the royal tomb, originally in the church of San Francesco in Castelletto in Genoa, given that the marble of these latter presents grey veining that is absent from the Madonna, which is distinguished by a soft alabastrine patina (fig. 46). 91 The statuette of the headless Madonna certainly belongs to the works created by Giovanni in the period he was working in Genoa on the imperial monument, though it is possible that the work was part of the vast

complex of sepulchral architecture or that it was intended for Genoa Cathedral, as part of an altar executed after the donation made by the emperor to the cathedral Chapter, before his departure from Genoa and in memoriam of his consort. Given that the sculptures in the Museo Civico di Sant’Agostino are almost exclusively from Genoese circles, it is highly unlikely that this statuette did not come from Genoa. Although we cannot be certain as to its provenance from the church of San Francesco in Castelletto or from the Cathedral, we can be sure of the dating to the second half of 1313, corresponding to Giovanni’s only Genoese sojourn for the creation of Margaret of Brabant’s tomb. 92

The ‘imperial context’ of the Genoese statue provides an important clue to a dating around the middle of 1313, given the very close stylistic and compositional resemblance to the Böhler Madonna (figs. 41-42). The two sculptures are of similar height: 47 cm the headless Madonna of Genoa and 60.5 cm the Böhler Madonna with the head created by Benedetto da Maiano (figs. 30, 41). The rediscovery of the statuette in the Böhler Collection, in view of its correct attribution to Giovanni Pisano, has made it possible to reconstruct an homogeneous stylistic group of Madonnas holding the Child, all about 60.5 cm tall, which bear witness to Giovanni’s ‘imperial style’ under the influence of the emperor Henry VII. 93 This stylistic reconstruction, something absolutely new in Giovanni Pisano studies, originated in the unprecedented comparison between the Genoa Madonna and the one in the Böhler Collection (figs. 41-42), thus breaking out of the narrow circle of stylistic comparisons hitherto known, which apart from the Madonna in the Museo Civico di Sant’Agostino, includes the headless Madonna donated by Paolo Lasinio to the collection of the Camposanto di Pisa (now in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo), long thought to be a workshop piece (fig. 43). 94 Our recognition of the stylistic similarity between the Böhler sculpture and the Genoese one has allowed us to reconsider

both the notable quality of the headless sculpture in Pisa (fig. 43), 54 cm tall, and to recognise in the headless Madonna in Boston, 47 cm tall, the work of a slavish imitator of the master. 95

The archetypal paragon – at the centre of our study – that allows us to recognise with precision the stylistic features of Giovanni Pisano’s ‘imperial style’ is that between the Genoese statuette and the Böhler Madonna as a work, hitherto lacking, that revolutionises the historical and stylistic understanding with which we observe all the other Madonnas by the sculptor. The attribution of the Böhler statuette to Giovanni Pisano is evidently confirmed in an initial comparison between the right faces of the Madonna and the same viewpoint on the Genoese statue (figs. 41-42). We note the conformity of the same stylistic features: the Virgin’s right knee bent forwards by the foot pointed backwards, forming an angle in respect of the flank in torsion. The emphatic movement of the knee stretches the heavy cloth of the cloak, gathering its lower folds to cover the right foot. The double fringed border of the drapery above and below the right knee of the Böhler Madonna, slightly stretches and raises the cloth, while the

shoulders and breast tend towards the Child. In the Genoese Madonna this tension of the bust and of the right hand is lighter, in fact the same gesture of the hand is less in torsion, although equally concentrated on raising the cloak which, because of the gentler movement of the bust, gathers finer and softer pleats at the belly, while those of the drapery that binds the lap of the Böhler Madonna are tighter and more synthetic.

The stylistic feature that more than any other identifies the handwriting of Giovanni Pisano is the shape of the right hand (figs. 44-45). The wrist, traced by the line of the sleeve’s cloth, flexes arching the back of the hand, a bit more rotated in the Genoese work and slightly curved upwards in the Böhler statuette, on which four dimples in the soft skin of the marble mark the beginning of the slender fingers. In both sculptures the thumb, index and middle finger, sinking into the pleats of the drapery, form the gesture that pins it with the three outstretched fingers, open on the belly, to move it away in the twist and close it to the side, lifting the heavy fabric to form a rich cascade of folds that fall triangularly degrading downwards.

The other two fingers are curled towards the palm of the hand. The stylistic punctum of the composition in both masterpieces by Giovanni Pisano is defined by the emphatic tension of the hand that is both tense and in movement. In both sculptures this gesture releases the compositional lines of the brilliant invention of a double movement, which combines the fluidity of the serpentine twist that goes from the foot to the knee, and to the hand up to the shoulder, culminating in the twisting of the head towards the Child, with the accentuated arching of the back.

The attribution of the Böhler Madonna to Giovanni Pisano and its dating to the Genoese period are confirmed by the observation of the plasticity of the compositional lines of the drapery in this sculpture (figs. 41-42, 44-45). Similarly to the Madonna of Genoa, in which the composition of the three directions of the pleats of the drapery, starting from the gesture of the right hand (from the back, from the cone falling under the hand and from the lap), wander in detailed calligraphic declinations in a slightly tense movement, in the Böhler Madonna the composition and the motif of the drapery, while the angular folds that flow from the back of the cloak into the right hand, those of the drape enveloping the lap and those falling from the fingers of the hand, are sculpted with greater softness and fluidity of movement.

In both statuettes the right wrist, elbow and shoulder create a compositional angle which, in the side view of the work, emphasises the arching of the bust, highlighting the lap unveiled by the drapery, the waist that holds back the folds of the soft garment on the breasts (figs. 41-42). The stylistic feature of the cloak that, fixed by a brooch, envelops the right shoulder sheathing the elbow and uncovering part of the breast, finds a double declination in the two sculptures: in the Genoese Madonna a single pleat of the cloak falls tautly to envelop the arm, creating a space visible in the contrasted chiaroscuro of the pleats between the posterior drapery, the arm and the bust, while in the Böhler Madonna the cloak falls softly from the clasp and the lamellar fold drops vertically right into the opening between the arm and the breast, covering with folds the tight-fitting sleeve of which we note the edge at the wrist.

In the light of these stylistic reflections, which on the basis of this comparison illustrate the topoi of Giovanni’s ‘imperial style’, it appears clear that the original prototype of the compositional elements of the Böhler Madonna is the Madonna in the lunette of the main portal of the Baptistery of Pisa. We will later discuss the relationship with this homogeneous stylistic group of the three Madonnas of the imperial period (figs. 30, 32, 78, 84)

Our new understanding of the corpus of the Madonnas created by Giovanni Pisano around 1312-1313, and therefore also their new stylistic interpretation, derive from the rediscovery of this group’s central figure, the Böhler Madonna (figs. 30, 42).

The sculpture of the Madonna and Child, both headless, conserved in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo (fig. 43) and 54 cm tall, entered the collection of the Camposanto in Pisa between 1810 and 1815, as a donation by Paolo Lasinio, attributed to Nino Pisano and without indications of provenance. 96 The sculpture was exhibited in the 1987 show ‘Giovanni Pisano a Genova’ and, for that occasion, underwent in Pisa in 1986 a careful cleaning which removed a thick layer of dust. 97 It was Roberto Papini in 1915, studying the Camposanto Collection, who identified the headless statue as the work of Giovanni Pisano, 98 followed by Enzo Carli who indicated the sculpture as a work attributed to the master. 99 In 1972 Seidel, although comparing the Madonna with the Madonna in the Bode Museum in Berlin and with the one in the Museo Civico di Sant’Agostino in Genoa (figs. 43, 46, 55), preferred to be more cautious, affirming that the statuette was the work of a talented assistant of Giovanni who worked closely with the master. 100 The sculpture was again exhibited in 1993 in the show ‘I Marmi di Lasinio’ in Pisa and, in the catalogue entry, Antonino Caleca attributed it to the circle of Giovanni Pisano, considering it a project of the late activity of the master’s workshop. 101 Following these studies, the sculpture is exhibited at the Museo di San Matteo in Pisa in a vitrine, similar to the one that today contains the ivory Madonna by Giovanni Pisano at the Museo della Primaziale. In 2005 Lorenzo Carletti attributed the sculpture to Giovanni Pisano. He confirmed this attribution in 2011 in a study published together with Cristiano Giometti. 102

In view of our present studies, the authenticity of the Madonna of the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo as a work by Giovanni Pisano is confirmed even more clearly by a comparison with the Madonna of Genoa (figs. 41, 43, 46). The Genoese statuette, made during Giovanni’s sojourn in Pisa after August 1313, is a work that expresses the ‘aulico stile imperiale’ of the master’s late maturity. At that time he must have been about sixty-five, given that he is thought to have been born around 1248 and, between 1265 and 1268, collaborated with his father Nicola on the pulpit of Siena Cathedral. 103 It is however unlikely that the statuette was originally located at the summit of the tomb of Queen Margaret of Brabant, as Clario di Fabio argued, 104 since it would have been in contrast with the correct iconography of the tomb’s architectural structure,