a zine on the tensions between queer asian/american communities and the mental healthcare system

Science, medicalisation, and healthcare institutions have harmed Asian/American communities. More specifically, queer Asian/Americans have an increased prevalence of negative mental health outcomes — and these disparities are inherently tied to the intersecting marginalisations faced by this community. This zine hopes to hone in on the relationship between queer Asian/American communities and their access to mental health resources and support. To ask ‘where is our care?’ is to inquire (and demand) why mental health institutions are failing us through an understanding of historical issues inherent to the field, as well as the current challenges faced by queer Asian/American. Simultaneously, the question is a reflection and curiosity of how queer Asian/Americans have built community and cared for each other in spite of systems of oppression. Thus, the thesis of this zine can be broken down into:

1) The current mental health challenges faced by queer Asian/American communities and the factors that lead to the tensions between them and mental healthcare resources/support.

2) Where, instead, are queer Asian/American creating or finding communities, spaces and moments of care?

This zine will move through a variety of sources — largely studies that focus on queer Asian/American experiences in the mental health field — to explore the topic. I also aim to loop in some critical theory in conversation with some of the larger themes that can be identified across the psychological studies to add an additional dimension that incorporates analysis of how power structures like race and cisheteropatriarchy are built and maintained.

This zine was made for the final semester project in AADS 240S: Asian American & Diaspora Psychology: Mental Health, Microaggressions, and the Model Minority Myth, taught by Dr. Hy Huynh.

Asian/American is used in this zine not because this project wholly encompasses the entire history and experiences of such an identity. Rather, because of the sheer scarcity of research on this topic, literature tends to sparsely cover a large range of identities that fall generally under Asian/American. I also engage with this label as a political, racial identity.

Similarly, queerness is a very broad umbrella term for sexuality and gender identifications that fall out of cisheteronormativity, and can be understood as analogous to LGBT+. Acknowledging the very different experiences of sexual and gender minorities, I use queer both because of the lack of literature, but also in its capacity as a label that thinks critically about and challenges rigid understandings of gender and sexuality.

Mental health institutions have not always been kind (to say the least) to queer communities of colour. Additionally, queerness is not always legible for Asian/Americans — racialised and classed aesthetics tend to dominate conceptualisations of queerness.

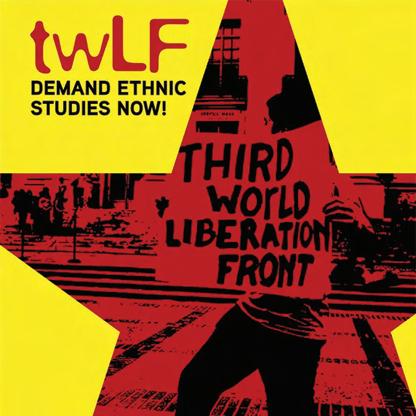

Asian/American as a term was coined in the late 1960s out of a need for a unifying political identity that was radically inclusive of the diverse Asian diasporic communities in the US.

TWLF was a coalition between Asian/American, Black and other racial student groups at San Francisco State University, fighting for the establishment of the first College of Ethnic Studies in the US, leading also to Asian American studies departments helping to institutionalize the term.

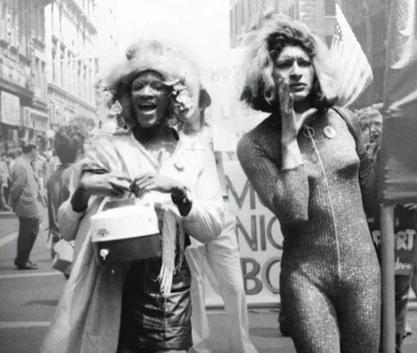

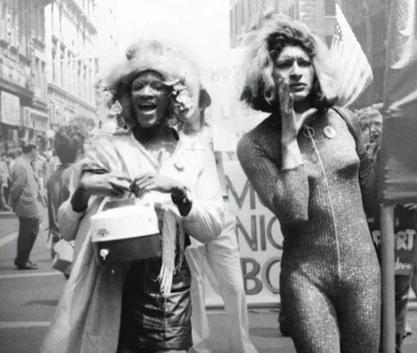

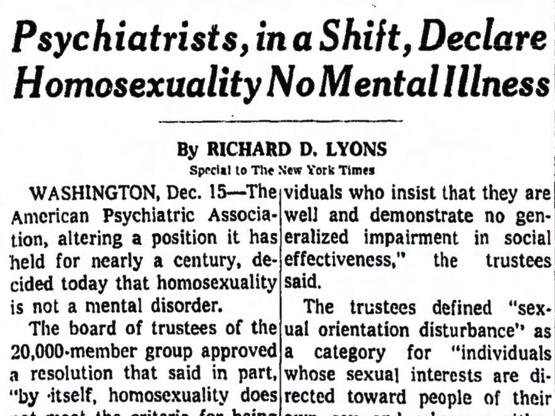

In large part due to the 1969 Stonewall riots (led by Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera) and the APA disruptions of the 1970s, homosexuality was declassified as a mental disorder in 1973.

Pathologisation and criminalisation of homosexuality were normalised in the 20th century, where psychoanalytic cures (conversion therapy) and imprisonment were common responses. Psychology also has explicit racist roots — ‘drapetomania’ was understood as a diagnosis for why enslaved people fled captivity.

queer and diaspora is independent of heterosexuality and nation

Eng (2010) thinks about the ways we can decline the “normative impulse to recuperate lost origins, to recapture the mother or motherland, and to valorize dominant notions of social belonging and racial exclusion that the nation-state would seek to naturalize and legitimate through inherited logics of kinship, blood and identity”. Divorcing queerness and diaspora from nationalism and its structuring logics of heternormativity might offer us new ways to think about identity and community. Eng also critiques colourblindness within queer liberalism — specifically how the forgetting and subsuming of race reinforce dominant power structures.

Becerra et. al. (2021) report that 25% of Asian/American sexual and gender minority (SGM) adults experience psychological distress, a rate four times higher than Asian Americans who are not SGM.

For queer Asian/American youths, it was found that bullying and victimisation at school especially were linked to negative mental health outcomes like depression and anxiety. (Gorse et. al., 2021; Matthews et. al., 2022)

Queer men are more likely to report suicidality compared to straight counterparts, queer women are more likely to experience depressive disorders than straight counterparts. For trans Asian/Americans, higher rates of suicidality and psychological distress were found. (Cochran et. al., 2007)

Transgender Asian/Americans and queer femme Asian/Americans were found to be at higher risk of abuse, both in childhood and relationships. (Becerra et. al., 2021; Choi & Israel, 2016)

Stigma and Cultural Norms: Influenced largely by ideals perpetuated by Westernisation/colonialism, norms have shifted from historically permissive perspectives on sexuality and gender fluidity to more modern pathologizations of queerness. Traditional values like filial piety and family reputation can create immense pressure for queer individuals to conform to heteronormative expectations (Ching et. al., 2018). This internalized heterosexism can lead to reluctance in disclosing sexual orientation and seeking help — particularly when coming out in ways that privilege Western values can feel at odds with values that Choi & Israel (2016) discuss as internal/private identity formulation and maintaining social order.

Lack of Quality Care: Healthcare providers often lack training and understanding of the unique needs and experiences of queer Asian/Americans. Gunter et. al. (2019) showed that clinicians were unable to acknowledge the effect of intersectional identities (or blatantly ignored them), misgendered patients, tended to overemphasize or inappropriately focus on queerness as a pathology and failed to use appropriate frameworks for understanding the role of identity in mental health. Hahm et. al. (2019) have also reported that there is a higher prevalence of inadequate care and unmet needs from mental health services for queer Asian/American women, compared to straight peers, though the study does not analyze any particular mechanisms.

Social Determinants of Health: Matthews et. al. (2022) discuss how social determinants of health, including immigration status (stressors like language, employment, deportation fears), economic stability (poverty, housing, chronic stress from lack of access to healthcare), and social isolation, significantly impact the well-being of queer Asian/Americans. All of these are particularly exacerbated by age — queer elders are reported to have increased strain from estrangement, language barriers and financial stability. Older folks also don’t generally have larger communities of support, and may not be able to access queer Asian/American spaces in the same ease as younger people, who tend to dominate these spaces. Some of this manifests in the usage of social media as the main form of outreach (which isn’t necessarily accessible to older folks) and the disparities in medical English literacy.

Communities built around single axes of identity: Queerphobia is reported as a common experience in Asian/American communities, alongside the racism faced by queer Asian/Americans within LGBTQ+ communities, resulting in psycho-pathogenic outcomes like invisibilisation and stress (Ching et. al., 2018). The dominance of whiteness within queer spaces can pressure queer Asian Americans to assimilate and minimize their racial/ethnic identities to gain acceptance (Le et. al., 2021). Studies also report a general discomfort and lack of engagement with narratives surrounding ‘coming out’, in which queer Asian/Americans don’t necessarily have the privilege of being able to have the same levels of visibility and safety as white queer individuals (Szymanski & Sung, 2013). researchers when theyrealise forthe100th

the most important modality of care found through this literature review has been the development of alternate social support networks and safe spaces. themes arise of:

chosen families: queer asian/americans often form "chosen families" with friends, allies, and other queer individuals who provide emotional support, understanding, and a sense of community (Yoshikawa et. al., 2004; Sung, Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2015).

organisations specific to queer asian/american organizations: offer a space to connect with others who share similar cultural backgrounds and experiences. Access to support networks that are supportive of multiple identities is instrumental to wellbeing and challenging discrimination and stigma (Choi & Israel, 2016).

online spaces: online platforms provide opportunities for connection and support, particularly for those who may not have access to physical communities or who prefer the anonymity of online interactions (Sung, Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2015)

coping mechanisms studied included a mixture of passive and active strategies that are utilised in participants

passive coping: some queer Asian Americans utilize "cultural camouflage" as a protective strategy, selectively disclosing their sexual orientation to manage potential stigma and maintain safety. this might involve maintaining close friendships with other women to conceal romantic relationships and/or utilizing the assumption of heterosexuality within asian/american communities to avoid unwanted attention or questioning (Choi & Israel, 2016; Sung, Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2015).

active coping: many queer asian/americans are engaging in activism and community leadership to advocate for change, raise awareness, and create more inclusive spaces. it can also involve creating new organizations or initiatives specifically focused on the needs of queer asian/americans or working within existing queer organizations to challenge racism and push for intersectional approaches (Sung, Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2015).

further approaches think critically about reclaiming and reframing cultural narratives, such as developing critical consciousness about how sociopolitical factors like white individualism has failed queer asian/americans (Choi & Israel, 2016). these methods of support and care revolve around the recognition of the historical fluidity and acceptance of gender and sexuality in many asian cultures prior to western colonial influence and deconstructing stereotypes and fetishization that contribute to the objectification and marginalization of queer asian/americans (Ching et. al., 2018).

Future directions can take an approach that aims to improve the field of psychology and create better modalities of care within the systems of mental health. Or, we can lean into the kinds of movement building and community values that queer communities of colour have historically carved out for themselves. Neither is a better option — they serve different dimensions of wellbeing for queer Asian/Americans, and studies have discussed multiple different opportunities.

Clinical providers have an enormous amount of power over the visibility of the patients — creating environments that are safe and inclusive should be of basic and foremost importance. Whether through better educational materials or the empowerment of queer Asian/American professionals, clinicians should understand the unique experiences and needs of queer Asian Americans (Choi & Israel, 2016). Studies that interviewed community organisation leaders also suggested campaigns to destigmatize mental health issues for queer Asian/American communities (Matthews et. al., 2022). Lastly, increasing access to mental health services that are culturally competent, affordable, and tailored to the needs of queer Asian Americans is crucial.

Leaning more into the informal networks and organizations of care, future directions can look at supporting queer Asian/American leadership in these spaces, supporting the accessibility and resources of the groups, and expanding their inclusivity and outreach (Matthews et. al., 2022).

Hong and Ferguson (2011) critique a lot of the traditional modes of categorization that erase lived experiences in the intersection of queerness and race, particularly rejecting the idea that identity is static or easily comparable. They explore how marginalized groups can (and need to) organize across difference, with particular care towards understanding how privilege and oppression are experienced differently across communities. This gives a critical theory lens on opportunities to develop spaces and interventions that are radically inclusive of queer Asian/American and other communities with multiple axes of identity.

Studies and literature consistently illustrate the multifaceted challenges and disparities faced by queer Asian Americans. These individuals experience a convergence of stressors stemming from their intersecting identities, leading to a higher risk of negative mental health outcomes and limited access to adequate support (Gunter et. al, 2019; Hahm et. al., 2019). Cultural stigma, particularly the pressure to conform to heteronormative expectations often rooted in colonial influences on traditional Asian values, creates a significant barrier to well-being. Queer Asian/Americans often struggle with familial rejection, internalized heterosexism, and difficulties disclosing their sexual orientation, further impacting their mental health — and many effects are compounded with age, as older generations lack the larger support networks to cope (Ching et. al., 2018; Matthews. et. al., 2022). This intersectional marginalization is compounded by a lack of culturally competent healthcare providers who can adequately address their unique needs. (Choi & Israel, 2016)

In response to these challenges, queer Asian/Americans are actively creating and seeking out alternative modes of care and support. These strategies centre on building strong social networks and safe spaces that affirm both their cultural and sexual identities. This includes forming chosen families, engaging in online and offline communities specifically for queer Asian Americans, and participating in events organized by both Asian American and queer organizations. Some individuals utilize cultural camouflage as a protective measure, selectively disclosing their sexual orientation to navigate potential stigma and maintain safety within their families and communities. Others turn to activism and community leadership to advocate for change and create more inclusive spaces. Additionally, while access to culturally competent care remains a challenge, seeking therapy and mental health treatment from providers who share their cultural background and/or queer identity is another avenue for support. The sources emphasize that these alternative modes of care are not merely coping mechanisms but represent a powerful form of resistance and resilience, empowering queer Asian Americans to create spaces of belonging, challenge dominant narratives, and foster well-being in the face of adversity.

a little zine about identity and mental health, by joy tong.