Kampung Education: Active Learning through Vernacular Space

Jovan Chen Thesis Research + Design

Jovan Chen Thesis Research + Design

Abstract

Education has continuously evolved alongside sociopolitical and technological shifts, progressing from medieval elitism to guild-based apprenticeships, industrial institutions, and now, into the rapidly changing landscape of the information age. A Dell Research Report states that “An estimated 85% of the jobs in 2030 haven’t been invented yet. The pace of change will be so rapid that people will learn “in-the-moment” … thus the ability to gain new knowledge will be more valuable than the knowledge itself,” emphasizing the need for meta-learning(active) over passive knowledge acquisition. Yet, contemporary educational spaces and pedagogies remain rooted in passive engagement and rigid boundaries, limiting learners’ ability to adapt to the uncertainty and complexity of modern society.

This thesis extrapolates the uncertainty of societal and technological shifts to assert the relevance of meta-learning(active learning) by implementing a vernacular spatial framework from Jakarta’s Kampung community. The Kampung— known for its diverse, resilient, and informal urban spaces—offers a living testbed for understanding how spatial configurations encourage multiple modes of learning, interaction, and collaboration. By examining the spatial dynamics of the Kampung and its intersection with Jakarta’s formal urban environment, the research seeks to reimagine educational spaces as adaptable, interactive, and integrated with the city.

Utilizing a campus building as an empirical case study, this thesis evaluates a design methodology that reinterprets Kampung spatial attributes into an innovative architectural lexicon with prospective global applicability. The methodology

encompasses a comprehensive design of the building’s spatial configurations, material properties, and circulation patterns, drawing systematic parallels with the organic, adaptable characteristics inherent in Kampung environments. Through an iterative design process, a series of frameworks were developed to create dynamic, community-centric spatial assemblages that facilitate spontaneous interactions, promote multimodal learning paradigms, and encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration.

The “Kampungified Spaces” framework serves not only as a spatial framework but also as a transformative blueprint for reforming existing educational environments. This framework creates an alternative possibility for the future of educational typologies.

Thesis Advisor

Kane Yanagawa 柳川肯

Education through the lense of Society

History and Development

Timeline of Education

I. The Changing Landscape

21st Century Education

Elements of Educational Space

School Building Typology

II. Learning from Vernacular Spaces

From Walled City to Kampung Enclaves

Community-based Urbanism

III. Kampung Typology Research

Kampung Case Study

Kampung Spatial Framework

The Unique Identity

IV. The Hypothesis

One size doesn’t fit all

Exercise I: Grafting Spaces

Exercise II: Fragments of Space

The Kampungify Framework

Social Ground

Social Diversity

Social Collectivity

Urban Test-Lab

No Man’s Land

Site Analysis

Kampung Education-Hub

The City and it’s Counterparts

The Campus and it’s Counterparts

The Plan is the Generator

The Section is the Activator

Credit & References

Education has always been one of humanity’s most fundamental tools for survival, progress, and transformation. As this timeline of educational history illustrates, the evolution of formal education is deeply interconnected with the development of human culture, reflecting the shifting priorities, values, and advancements of civilizations over millennia. From its nascent stages in ancient societies to the sophisticated systems of the modern era, education has not only been shaped by the cultures that created it but has also actively influenced the trajectory of human civilization.

Ancient Times. In Ancient Egypt, one of the earliest civilizations to establish formal education,

schools served as training grounds for scribes and administrators, reflecting the societal emphasis on governance, record-keeping, and religion.

Similarly, in Ancient China, the creation of schools during the Xia dynasty was designed to educate aristocrats in rituals, literature, and archery, underscoring the Confucian ideals of order, hierarchy, and moral cultivation that dominated Chinese culture for centuries. Education here was less about innovation and more about preserving and transmitting cultural values.

Meanwhile, in Ancient India, education was passed down orally and centered on spiritual and philosophical pursuits. The three-step process of Shravana (hearing), Manana (reflection),

and Nididhyasana (application) exemplifies the connection between education and personal transformation in Indian traditions. This focus on introspection and wisdom laid the foundation for disciplines like yoga, logic, and metaphysics that continue to influence global thought today.

In the West, Ancient Greece revolutionized education with a distinct focus on critical thinking, physical training, and the pursuit of excellence. The Socratic method—built on dialogue and inquiry—epitomizes this era’s commitment to intellectual rigor and democratic ideals. The Greeks’ informal yet structured approach to learning was further developed during the Roman Era, which adopted Greek pedagogical practices but emphasized rhetoric and law to suit the needs of their expanding empire. These systems of education reflected the sociopolitical priorities of their time and reinforced the civic identities of their citizens.

Middle Ages. The Middle Ages marked a period where education was predominantly controlled by the Church, reflecting the era’s deep religious influence on all aspects of life. Monastic schools preserved classical knowledge and ensured its transmission, while the rise of universities in the 12th century—such as those in Bologna and Paris—heralded a new era of scholasticism. These institutions sought to reconcile faith with reason, laying the intellectual groundwork for later cultural revolutions.

Renaissance Period. The Renaissance was a turning point, as humanism sparked a revival of classical learning and emphasized the value of arts, literature, and philosophy. Thinkers like Comenius championed universal education, advocating for systematic teaching methods and broader access to learning. This period reflected humanity’s growing belief in the potential of the individual and the transformative power of knowledge.

The Enlightenment took this further, promoting ideas of rationality, individualism, and empirical inquiry. Philosophers like John Locke and JeanJacques Rousseau redefined education as a

means of personal liberation and social progress. The emphasis on experiential learning and civic responsibility during this era underscored education’s role in shaping not just individuals but also modern nation-states.

Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution brought about rapid changes in society and demanded new forms of education to prepare individuals for roles in industrialized economies. As urbanization and mechanization transformed daily life, education shifted from classical to practical knowledge, fostering skills that aligned with the needs of modern labor markets.

20th Century Education. The progressive education movement, championed by John Dewey in the 20th century, emphasized experiential learning, social responsibility, and the holistic development of individuals. This movement reflected the increasingly interconnected and democratic world, where education is seen as a means of nurturing creativity, critical thinking, and global citizenship.

Throughout history, education has evolved in response to humanity’s needs and aspirations. It has served as a mirror of cultural values, a tool for social cohesion, and a catalyst for innovation and change. By examining its history, we can better understand how education not only reflects the progress of civilization but also serves as its engine, empowering generations to navigate the challenges of their time while shaping a shared future.

Education of the 21st century is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by advancements in technology, cultural evolution, and the need for a more holistic approach to learning. At the heart of this transformation is the concept of the “meta-learner,” a framework proposed by the Boston-based Center for Curriculum Redesign (CCR). The meta-learner is built on three core components: knowledge, skills, and character, providing a comprehensive approach to education in a rapidly changing world.

Traditionally, educational institutions and pedagogies were centered on the transmission of knowledge from teacher to student, often relying heavily on books and other static sources. Classrooms and lecture halls symbolized this paradigm, where the teacher was the primary authority, and the curriculum was designed to produce specialists for predictable roles in society. However, the rapid evolution of the Internet, artificial intelligence (AI), and global connectivity has rendered this model insufficient. Knowledge, once scarce and valuable, is now ubiquitous and instantly acces sible. This shift has diminished the importance of rote learning and placed a premium on the ability

to learn, unlearn, and adapt—the hallmarks of meta-learning.

Meta-Learning. Meta-learning emphasizes resilience, adaptability, and the capacity to tackle uncertainty—skills that are increasingly vital in a world where the future is unpredictable. A research by Dell Technologies states, “An estimated 85% of the jobs in 2030 haven’t been invented yet. The pace of change will be so rapid that people will learn “in-the-moment” … thus the ability to gain new knowledge will be more valuable than the knowledge itself.” This startling projection underscores the need for education systems to focus not just on imparting knowledge but on fostering the skills and character necessary to navigate a rapidly changing landscape. Learners must be equipped to think critically, collaborate effectively, and approach challenges with creativity and confidence.

Pedagogy. Pedagogies must evolve to prioritize active and experiential learning, where students engage with real-world problems and develop the ability to learn independently. The role of the educator is no longer that of a knowledge gatekeeper but a facilitator and mentor, guiding students to

become self-directed learners. The integration of AI and digital tools further supports this shift, enabling personalized learning experiences and expanding access to resources that empower learners to take ownership of their education.

Transition. The convergence of these trends highlights the transition from traditional educational institutions to dynamic systems that prioritize the development of meta-learners. In this new model, the ability to adapt, innovate, and thrive in uncertain environments becomes the ultimate goal of education, preparing individuals not just for specific careers but for lifelong learning and personal growth.

source: BostonCenterforCurriculumRedesign,“EducationintheageofAI”

Building on the transformation of education and the rise of the meta-learner, the design and structure of educational spaces must undergo a similar evolution. The physical environments in which education takes place are not neutral; they reflect and reinforce the pedagogies and learning methods they are designed to support. Traditional educational spaces, from classrooms to campuses, were shaped by the hierarchical, teacher-centered model of learning, which emphasized the unidirectional transfer of knowledge. These spaces prioritized control and order, often at the expense of creativity, interaction, and flexibility.

In traditional pedagogy, the teacher was the central figure, and the classroom was designed to reflect this. Rows of desks facing a single point of authority—the teacher’s desk or podium—symbolized the one-way flow of information. This layout, coupled with rigid schedules and compartmentalized subjects, created an environment that prioritized efficiency and discipline over collabo-

ration and adaptability. Lecture halls and libraries extended this model to larger scales, reinforcing the idea that knowledge was to be consumed passively rather than actively constructed. Such spaces mirrored the industrial-era approach to education, which aimed to produce specialists for predictable, stable roles in society.

However, as pedagogies have shifted toward active and experiential learning, the inadequacies of these traditional spaces have become increasingly apparent. Active learning methods, which prioritize engagement, problem-solving, and collaboration, demand environments that are flexible and adaptable. For example, group projects require reconfigurable furniture, while hands-on activities benefit from open, modular spaces. The rise of interdisciplinary approaches further challenges the traditional layout, as these methods often require spaces that encourage interaction across fields and disciplines. The rigidity of conventional designs hinders the dynamic exchange of ideas and limits the potential for creativity and innovation

SMLXL. The diagram illustrates how educational spaces, at different scales, influence the perception and experience of learning. At the smallest scale (S), individual elements such as desks, chairs, and personal workspaces shape the learner’s immediate experience. These elements, often designed for passive use, can stifle engagement and limit the freedom to explore new ways of learning. At the medium scale (M), classrooms and lecture halls dictate how groups interact, often enforcing a top-down hierarchy that conflicts with collaborative pedagogies. Moving to the large scale (L), buildings and campus layouts reflect institutional priorities, with rigid zoning and segregated disciplines that restrict interdisciplinary collaboration. At the extra-large scale (XL), the relationship between campuses and cities determines how education integrates with the broader community, often isolating academic institutions from the real-world contexts they aim to address.

In the context of the meta-learner, educational

principles of adaptability, inclusivity, and collaboration. The passiveness and rigidity of traditional spaces must give way to environments that inspire curiosity, foster creativity, and facilitate the fluid exchange of ideas. This requires a fundamental shift in how educational spaces are conceived and built, moving away from hierarchical structures toward flexible, learner-centered designs. Spaces must support the diverse needs of modern learners, integrating technology seamlessly while promoting active participation and real-world engagement.

As education continues to evolve, so too must the spaces in which it occurs. By aligning the design of educational environments with the goals of active, experiential learning and the development of meta-learners, we can create spaces that not only accommodate but actively enhance the transformative potential of education in the 21st century.

Jakarta’s Urbanism

To understand how education of the future can integrate with vernacular spaces, it is essential to explore the historical and spatial evolution of Jakarta. Jakarta, originally a port city, has a complex urban fabric shaped by its colonial past, rapid modernization, and persistent vernacular traditions. This dynamic history has given rise to unique spatial typologies that reflect the cultural and socio-economic tensions between planned urban development and organic, community -based growth.

Jakarta’s transformation began during the Dutch East India Company era in the 17th century. The city, then known as Batavia, was established as

a fortified settlement, surrounded by a walled city that primarily catered to Dutch elites and their commercial interests. This structure intentionally excluded the indigenous population, pushing them to the periphery. The enactment of segregation laws, such as those following the Batavia massacre of 1740, reinforced this divide, creating a clear spatial and social boundary.

Social Segregation. The 1740 massacre, where thousands of Chinese residents were killed or displaced, marked a turning point. Survivors and indigenous populations formed informal settlements, or kampungs, outside the city walls. These kampungs emerged as adaptive spaces—self-organized, resourceful, and deeply rooted in local

traditions. The typology of these settlements was vernacular by necessity, blending indigenous values with pragmatic responses to spatial constraints. Over time, kampungs became densely populated enclaves, characterized by narrow alleys, communal spaces, and hybrid structures that accommodated both living and working activities.

Modernist European Urban Planning. The arrival of the Jakarta-Bogor railway in 1884 signified the onset of modern infrastructure and urban expansion. While the railway enabled connectivity and economic growth, it also contributed to a fragmented urban landscape. Development became concentrated along railway lines, leaving

kampungs in spatial tension with the planned city. This patchwork city growth intensified as colonial urban planning prioritized the creation of new districts for administrative and residential purposes, often neglecting the needs of kampung communities. Post-independence urbanization and projects like the Menteng development in the mid-20th century further exacerbated this fragmentation. Kampungs, while marginalized, persisted as resilient spaces that adapted to the pressures of modernization. These areas became hubs of traditional Indonesian values, fostering community cohesion, mutual aid, and localized economies amidst the rapidly transforming city.

City of Tensions. Jakarta today is a city of con-

trasts, where high-rise developments and modern infrastructure coexist with densely populated kampungs. This juxtaposition reveals a tension between the formal city and its informal counterparts. Kampungs, though often dismissed as underdeveloped, embody unique social and spatial qualities. They serve as vibrant community spaces, enabling traditional practices to flourish in the face of urban pressures.

This phenomenon of patchy growth, where modern urban planning and vernacular settlements intersect, creates a rich and complex urban fabric. Kampungs act as counterpoints to the rigidity of planned urban spaces, offering a form of spatial resilience that aligns with the unpredictability of Jakarta’s growth. They demonstrate the potential for bottom-up, community-driven development to coexist with top-down urban planning.

Vernacular Spaces as Platform for Education. As we consider the integration of future education into Jakarta’s urban landscape, kampungs pres

ent intriguing possibilities. These vernacular spaces, shaped by history and tradition, offer ing environments. Their emphasis on communal interaction, adaptability, and resourcefulness aligns with the principles of active and experiential learning.

The evolution of Jakarta’s kampungs from isolated enclaves to integral parts of the city highlights their potential as adaptive learning spaces. By embracing the vernacular typology and its inherent values, future education systems can bridge the gap between the rigidity of formal institutions and the dynamism of informal, community-driven environments. This convergence has the potential to redefine education not just as a process of knowledge transfer, but as an integral part of urban life that thrives in the interplay of tradition and modernity. fertile ground for the development of meta-learning environments. Their emphasis on communal interaction, adaptability, and resourcefulness aligns with the principles of active and experiential learning.

“Kampung

adalah tempat dimana semua orang saling bertegur sapa”

“Kampung

is a place where everyone greets each other”

Kampung and it’s Culture

Kampungs represent a distinctive model of community-based urbanism, where tradition and adaptability coexist within the dynamic fabric of Jakarta’s growth. These settlements function through an organic yet structured hierarchy comprising RT (Pillars of Neighbors), RW (Community Units), and kelurahan (sub-districts). This decentralized governance fosters a strong sense of identity and belonging, rooted in “gotong royong” (mutual assistance), a cultural practice that unites residents through solidarity and cooperation.

Informality. Despite their informal status, kampungs thrive as vibrant, dense, and resourceful spaces, capable of evolving in response to social, economic, and environmental challenges. Their adaptability arises from shared knowledge and collective problem-solving, enabling kampungs to remain resilient amid pressures from formal urban development and rapid modernization. This duality, where informal kampung life coexists with structured planning, creates an intriguing tension. Kampungs act as cultural and social anchors, preserving traditional Indonesian values while counterbalancing the rigidity of formal urban systems.

The kampung is more than just a settlement pattern; it is a framework for resilience and inclusivity. Its structure encourages constant adaptation, fostering strong community bonds and a shared

identity. Kampungs have demonstrated a remarkable ability to “learn” and “relearn” through communal experiences, offering a living example of adaptive urbanism. This resilience makes them uniquely suited to navigate uncertainty and change, highlighting their role as laboratories of innovation within the urban landscape.

As Jakarta continues to evolve, kampungs provide valuable lessons for the future of urban and educational spaces alike. Their emphasis on collaboration, cultural relevance, and the well-being of their residents underscores the potential of informal systems to address complex urban challenges. By bridging tradition with modernity, kampungs exemplify how deeply rooted communal practices can inform more inclusive and sustainable urban designs.

30,480 RT (Pillars of Neighbors)

1,367 RW (Pillars of Residents)

267 Kelurahan (Sub-district)

44 Kecamatan (District)

5 Kotamadya (City District)

Our investigation into Kampung typologies began with the selection of four diverse sites across Jakarta: Kampung Muara Baru, Kampung Luar Batang, Kampung Melayu, and Kampung Rawa. These initial specimens offered a glimpse into the urban fabric of Jakarta’s informal settlements, providing distinct examples of how Kampungs operate spatially and socially within the dense city environment.

We adopted a two-pronged approach to analyze these sites: figure-ground mapping and street-level perspectives using Google Maps’ Street View. This dual method revealed a fascinating divergence in understanding spatial qualities. The figure-ground plans, while effective for defining boundaries and capturing the organic, non-linear layouts that contrast sharply with Jakarta’s rigid city grid, provided little insight into the dynamic spatial experiences within the Kampungs. The extreme density of these areas, with Floor Area Ratios ranging from 70-90%, meant that plans alone were unable to convey the vibrant, compact nature of these environments.

Shifting to a street-level perspective unveiled an entirely different dimension. Navigating the streets

virtually, we encountered the intricate interfaces of Kampung life—the blurred boundaries between public and private spaces, the interplay of informal furniture arrangements, food stalls, motorbikes, and daily activities. These elements collectively create a rich spatial narrative that is invisible in two-dimensional plans. The streets come alive as spaces of interaction and adaptation, where the density fosters resilience and a unique communal spirit.

It became clear that while figure-ground plans are useful for identifying boundaries and overall patterns, street-level perspectives are crucial for understanding the experiential and qualitative aspects of Kampung spaces.

In-depth Research. In this next phase, we selected a 100m x 100m section within Kampung Luar Batang for further analysis. This area was reconstructed in 3D with a high degree of precision, enabling us to capture the complexity of its spatial and social structures. This meticulous approach aims to bridge the gap between macro-level observations and micro-level interactions, providing a comprehensive understanding of how Kampung spaces function as resilient, adaptive, and vibrant urban environments.

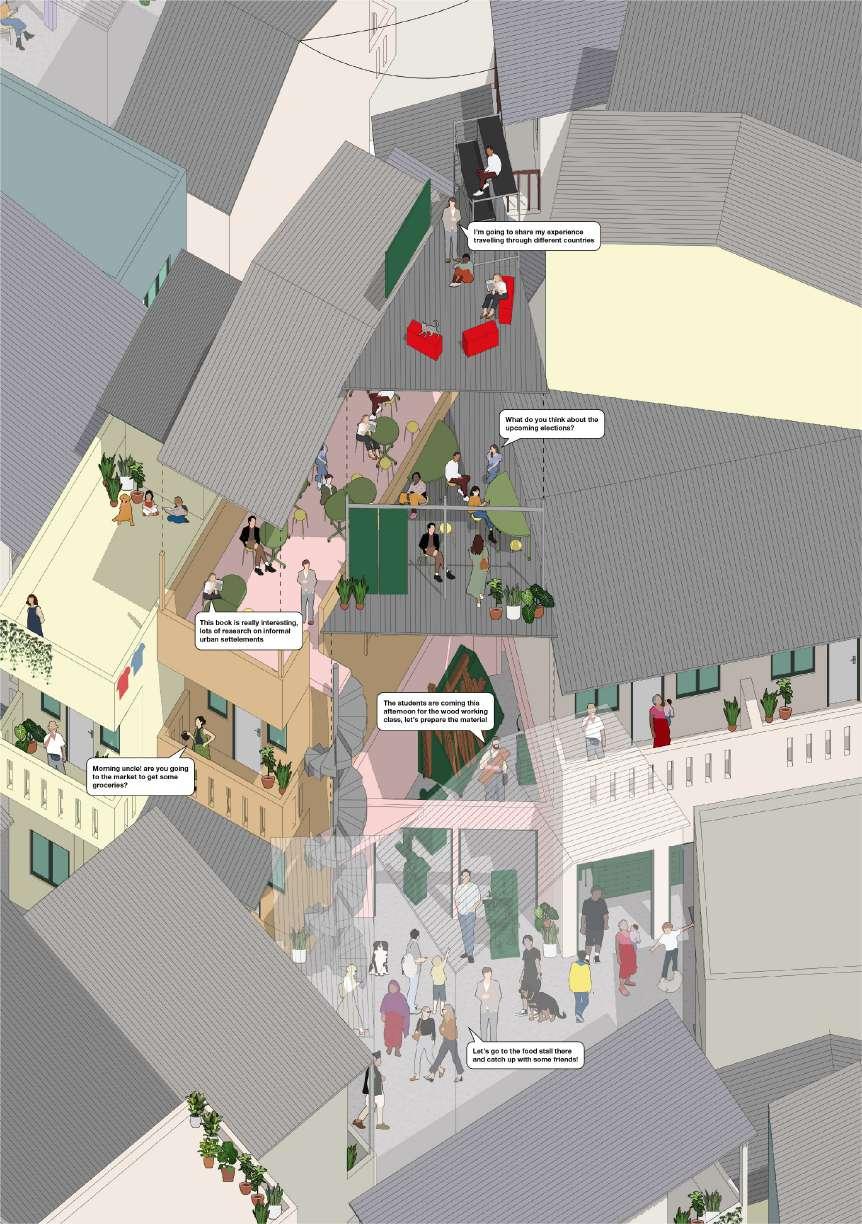

The Learning Society Kampung spaces provide a compelling framework to rethink future educational environments. These spaces thrive on adaptability, where social cohesion, interaction, and informal learning are integral to daily life. The diagram highlights the interplay between formal and informal, individual and collective dynamics, forming the foundation for inclusive and collaborative educational models inspired by kampung life.

In kampungs, learning emerges naturally through shared experiences rather than institutional structures. Streets, transitional spaces, and community anchors such as mosques or informal markets act as hubs for interaction and discussion. These spaces dissolve boundaries between public and private, fostering environments that support organic learning. Integrating activities like food stalls, play areas, and communal gatherings creates a vibrant setting for knowledge exchange and skill-building.

Informal. The informal vitality of kampung life shows how learning is deeply rooted in communal interactions. Children learn through play and observation, adults share knowledge in everyday encounters, and collective problem-solving addresses shared challenges. This participatory model values lived experiences, making everyone a teacher and a learner. The kampung becomes a dynamic environment for growth, driven by collaboration and interaction.

This kampung-inspired approach to education emphasizes openness and collectivity, challenging traditional hierarchies that separate institutionalized education from the lived realities of marginalized communities. By embracing the principles of inclusivity and adaptability found in kampung spaces, we can envision an educational future that bridges social divides and fosters shared learning for all.

“The quality of communities is their ability to combine two seemingly competing characteristics: density and individuality. On the one hand, communities are dense, public and collective; on the other, they enable individual freedom and identity, traits expressed through flexibility and diversity.”

-MVRDV-

The statement underscores the need for a transformative approach to educational spaces and pedagogy. Drawing from our research on kampung spaces and their dynamic, communal nature, we propose an alternative model called “Kampung Education.” This approach seeks to merge the organic, flexible qualities of kampung environments with the structured framework of contemporary educational systems.

The vision highlights a symbiosis between educational spaces, site context, and kampung. This convergence fosters identity, engagement, and adaptability, resulting in an enriched learning environment that transcends traditional boundaries. Kampung Education operates on two interrelated realms: Spatial Prototypes and Programmatic Frameworks.

Spatial prototypes include anchor spaces and activator spaces, which provide communal hubs and catalysts for interaction. These spaces are designed to be open, flexible, and inclusive, promoting active participation from locals, teachers, students, and passersby. They dissolve rigid hierarchies and encourage organic learning through informal exchanges and shared experiences.

Programmatic frameworks outline a hybrid learning system that blends “high culture” institutional practices with “low culture” communal dynamics. By fostering collaboration, adaptability, and engagement, these frameworks cultivate a lifestyle of continuous learning. They emphasize social exposure and interaction, transforming education into a shared, everyday experience.

At its core, Kampung Education envisions a hybrid meta-learning environment that is resilient,

inclusive, and vibrant. This model celebrates the richness of both formal and informal learning systems, offering an alternate reality where education becomes a communal and adaptive process, deeply rooted in the local context while remaining forward-looking and innovative.

To test our hypothesis, we conducted a series of exercises, Exercise I: Grafting Spaces: focused on the integration of educational programs into a 100m x 100m kampung specimen that we decided. The selected programs (for now)—a classroom, a studio, and an auditorium—were carefully grafted into the existing kampung environment. This approach prioritized the organic spatial qualities of the kampung while minimizing design interventions, aiming to allow the inherent dynamics

of the site to guide the interaction between these new elements and the existing framework.

By retaining the kampung’s spatial structure and embracing its informal, adaptive nature, we sought to observe how educational programs might harmonize with everyday life. This method emphasized the fluidity of kampung spaces, where public and private boundaries dissolve, and communal engagement thrives. The grafting exercise revealed a unique interplay between

these programs and the kampung’s physical and social environment, providing insights into how educational interventions can coexist with and enhance the existing community fabric.

This exercise serves as an early test of Kampung Education’s potential to merge structured learning spaces with organic, community-driven environments, offering a promising model for adaptable, inclusive, and resilient educational frameworks.

Programmatic and Pragmatic

The nine selected sites within the kampung each embody unique spatial and programmatic qualities, encompassing a variety of scales and typologies. These range from existing traditional markets to leftover sheds, from narrow alleys to someone’s backdoor kitchen, and from ground-level spaces to rooftops. They span the spectrum from private to public realms, capturing the diverse character of the kampung environment.

Our approach focused on integrating new educational programs into these existing spaces. By grafting these programs onto the existing spatial fabric, we sought to explore how the kampung environment could amplify learning and foster social interaction. This process required a thorough study of how the existing spaces would interact with the new interventions, both spatially and socially, and how these relationships could generate new opportunities for the community.

To respect the intrinsic qualities of the kampung, we deliberately minimized our design interventions. This allowed the existing spaces, the newly introduced programs, and the community itself to shape the transformation of these sites organically. Our aim was not only to adapt the educational programs to the kampung environment but also to observe how this synthesis could enrich the kampung’s character and functionality, unlocking new possibilities for spaces that encourage learning and interaction.

To organize and analyze these interventions, the nine sites were categorized into two types of spaces: anchor spaces and activator spaces. This classification is based on how each scale responds to the environment and how the interaction between existing and newly grafted programs creates hubs or spaces with distinct roles.

Anchor Space. Anchor spaces are larger-scale interventions, such as markets, studios, or mosques, that serve as central hubs for the community. These spaces are typically permanent and act as anchors within the kampung, bringing people together and fostering a strong sense of connection.

Activator Space. Activator spaces, in contrast, are smaller-scale interventions like food stalls in alleys, reading corners, or balconies. These spaces interact with their surroundings in a more transient or flexible way. Unlike anchor spaces, activator spaces may not always be present but are equally vital in enriching and energizing the kampung environment, fostering dynamic, intimate interactions at a smaller scale.

Together, these two types of spaces illustrate how the kampung environment supports a layered and dynamic approach to learning and community interaction. By allowing the permanence of anchor spaces and the flexibility of activator spaces to coexist, we aim to demonstrate how synthesizing educational programs with the kampung’s spatial and social fabric can create a paradigm for learning—one that is open, engaging, and deeply rooted in the everyday life of the community.

Site A integrates a large program—a flexible auditorium—into the tight, intricate kampung environment. By utilizing the gaps between buildings and an existing interior courtyard, we sought to embed this expansive space seamlessly within the surrounding fabric. The design leverages scaffolding as a structural framework to create adaptable seating areas, while simultaneously providing access to nearby rooftops.

The combination of rooftop access and stair-like spaces, formed through the stacking of scaffolding, transforms the auditorium into a versatile and dynamic environment. This configuration allows the large hall to accommodate a variety of activities and needs, ranging from intimate gatherings to large-scale community events. Nearby food stalls further enhance the vibrancy of the space, encouraging social interactions and fostering an inviting atmosphere.

The adjacent studio, designed as a space for students and locals to learn and exchange knowledge, plays a critical role in creating a boundless, interactive environment. The open nature of the auditorium, with its flexible design and visual permeability, blurs the boundaries between the two spaces. The studio’s direct access to the auditorium—both physically and visually—creates opportunities for seamless interaction. As activities take place in the auditorium, the studio serves as an extension, allowing people to observe, engage, or transition between focused learning and communal events.

This interconnectedness fosters a dynamic synergy between learning and community interaction. The flexibility of the auditorium and its integration with the studio ensure that these spaces do not operate in isolation but merge into a single cohesive environment. The result is a fluid, adaptable space that encourages collaboration, supports diverse activities, and strengthens the sense of community within the kampung.

Site B is located within an existing residential building adjacent to the community mosque. Our design grafts a studio learning space into the building’s ground level, opening it up towards the street, the mosque, and a nearby food stall. This strategic positioning allows the existing anchor space—the mosque, which serves as a religious and cultural hub—to create an interesting relationship with the new studio space, which functions as an anchor for learning.

The mosque’s role as a community gathering point is extended through its interaction with the studio space, where people can meet, discuss, and engage in conversation. This relationship blurs the lines between public and private, creating a fusion of learning and community activities. By integrating these two functions, the design fosters informal conversations and visual connections, allowing the mosque and the studio to complement each other and encourage engagement across both spaces.

This blending of uses transforms the street, infusing it with new vibrancy as two distinct programs—religious activities and educational learning—juxtapose each other. The resulting transitional space becomes inclusive, inviting both community members and learners to interact freely. The studio is designed to accommodate various types of learning, from kinesthetic and audio-visual experiences to reading, writing, and personal study. The inner areas provide more intimate spaces for focused learning, while the open, flexible layout encourages movement and collaboration.

Moreover, the studio’s function changes throughout the day. The adjacent food stall, with direct access from the studio’s side, creates a dynamic learning environment by incorporating food consumption into the learning experience. This interaction between food and learning fosters a new way of engagement, where people can enjoy food while participating in conversations or informal discussions, thus enhancing the social and educational atmosphere.

The food stall seating area further blurs the boundaries between the studio and the street, creating an even richer environment where everyone—regardless of their purpose—can come and go. This design not only encourages spontaneous interactions but also creates a space where learning and community life coexist in a fluid, inclusive manner.

Site C is located beside an existing woodshop and a leftover shed. Our design repurposes this shed into a woodworking workshop that encourages collaboration between students and locals. This intervention emphasizes “learning by doing,” creating direct opportunities for students to engage with the carpenters next door and learn through hands-on experience.

By utilizing the leftover space, we extend the existing woodshop into a community workshop open to all. Additionally, two new floors were added above the workshop to foster small, informal discussions, brainstorming sessions, and personal learning spaces. The vertical expansion of the space demonstrates how density can be harnessed to create vibrant, distinct areas within the kampung.

The higher floors offer new perspectives on the dense kampung environment, providing quieter spaces for focused learning when needed. This vertical density helps balance the active, handson learning environment on the ground floor with more introspective, personal spaces above. The intervention creates a gradient of publicity, with the ground floor integrated into the woodshop to provide an open, communal learning atmosphere.

The second floor offers semi-public, informal spaces for conversation and idea exchange, while the upper floor prioritizes personal learning through private spaces and expansive views of the surrounding kampung.

This design aims to show how the layering of spaces—both horizontally and vertically—can foster different types of interactions, supporting a range of learning experiences and creating a vibrant, multifaceted environment.

For Site D, we selected a two-story existing building, where the ground floor is a traditional market and the upper level is residential. The design involves renovating and repurposing the building to accommodate additional programs that engage with its surrounding environment.

On the ground floor, we emphasize the openness of the traditional market by introducing hot-desking spaces alongside the market. These spaces function as waiting areas, inviting people to linger and interact, thereby enhancing the communal experience. This intervention encourages engagement between visitors and market vendors, fostering an environment of social exchange and connection.

The second floor is reimagined as a space for small to medium semi-outdoor learning environments. Here, walls of varying heights serve as both media for learning and spatial dividers, creating intimate areas that foster focused engagement while maintaining visual connections. This layering of spaces allows for diverse types of learning, from group discussions to independent study.

In addition, an outdoor area is integrated into the design, using scaffolding structures that emphasize openness and flexibility. This space is ideal for medium-scale events or activities and creates a dynamic connection to the semi-outdoor learning areas.

The third floor is dedicated to kinesthetic learning, supporting activities such as sports or interactive learning through movement. This floor further diversifies the range of learning experiences within the building.

Finally, the rooftop is designed to accommodate various types of seating and conversation areas. It offers a visual connection to the third floor, allowing the rooftop to function as an extension of the learning spaces below, capable of hosting different activities.

This intervention explores the idea of stacking diverse programs to create cross-level interactions through visual connections, circulation, and even sound. By fostering relationships between different floors, the design encourages a dynamic flow of learning and engagement across multiple levels. Ultimately, this concept emphasizes how layering programs vertically can enhance interaction and collaboration in a compact urban

This site focuses on repurposing an existing shed, which was originally used as a waiting area for bike riders and locals, complete with snack and food stalls. This existing program is enhanced by adding a newly grafted reading space and min

gling areas, transforming the shed into a dynamic, informal gathering space.this intervention creates a new type of micro-library, where people can relax, socialize, and engage with educational content in a casual setting.

Site F extends a second-floor balcony over the street, creating a semi-public space with visual connections to the street. The ground floor features a communal bookshelf for book exchange, while the second floor serves as a cozy lounge

for relaxation and interaction. The extension allows potential access to a neighboring rooftop, increasing the space’s versatility.

Site G

This intervention transforms a tight alley with a food stall into a semi-café by incorporating wooden pallets to create more lingering space. This setup encourages engagement and information sharing, turning the quick food stop into a space

where people can hang out. The goal is to explore how small food stalls can be enhanced to activate the environment and foster learning through community interaction.

Reimagining the classroom as an active, engaging space rather than a controlled, sterile environment was central to this site. Positioned near a bike shop and driver waiting areas, the classroom dissolves spatial boundaries, enabling interaction

between students and the surrounding community. The space fosters awareness and exchange, where bike drivers can relax, share experiences, and even engage with the learning environment, creating a harmonious blend of education and everyday life.

Site I

Site I utilizes a small niche between buildings, transforming it into an active learning space integrated with a kitchen at the back. The design emphasizes how this compact space can become vibrant. Coupled with a second-floor micro-library

the intervention explores how tight spaces can be adapted to accommodate a range of activities, from small reading groups and discussions to live bands and community gatherings.

The interventions on each site highlight the untapped potential of kampung spaces to redefine the future of learning environments. By carefully integrating educational programs within the organic structure of these spaces—whether through traditional markets, residential areas, or informal gathering points—we uncover how flexible, community-driven settings can support both structured and unstructured learning.

The goal of these interventions was to extract and amplify the inherent qualities of kampung spaces—adaptability, community engagement, and fluidity—to propose an alternative future for learning spaces. These experiments challenge the traditional, rigid notions of educational environments and demonstrate that learning can thrive in dynamic, informal settings that blend seamlessly with everyday life.

By embracing the spatial and social richness of the kampung, these designs offer a new paradigm for educational spaces—one that fosters interaction, collaboration, and a deeper connection to the community. Ultimately, they present a vision for the future where learning is not confined to the classroom but is instead integrated into the very fabric of our surroundings, making education a continuous, evolving, and deeply social experience.

In the Kampung, the ground plane is not merely a surface but an active agent that shapes social behavior. Rather than remaining neutral, the ground must be utilized to guide human movement and interaction by suggesting specific uses and activities. By creating a “polarized” space—one that encourages both convergence and divergence— this approach transforms the environment into an active contributor to social production. This effect can be achieved through deliberate spatial strategies that integrate diverse elements to establish clear yet ambiguous cues and areas of activity.

Like the Kampung’s alleys, the idea of the playful alley embodies a ground plane that is intentionally porous and dynamic. This corridor-like space functions as a transitional “gray area” where boundaries are blurred and no single activity dominates. The resulting ambiguity invites users to engage with the space on their own terms, fostering spontaneous interactions and creative learning experiences. The playful alley thus becomes a site of both connection and creative disconnection, where the potential for overlapping or conflicting interests adds a dynamic edge to the learning environment.

It integrates distinct yet autonomous spatial programs to generate juxtaposition and spatial ambiguity, fostering an open and explorative learning environment. By interweaving spaces with varying degrees of publicity and user engagement, this approach cultivates dynamic relationships that encourage learners to interact, reflect, and participate proactively. Through strategic spatial overlaps, program stitching enhances social exposure and supports active learning, transforming educational spaces into adaptive and interactive environments.

Contrary to the conventional notion of flexibility as an open-plan concept, the Kampung achieves adaptability through a network of niches, small spaces, and streets that foster individuality and diversity. Rather than relying on large, undefined spaces, its adaptability emerges from the capacity of these smaller, interwoven environments to accommodate evolving social and functional needs. The proposed learning spaces embrace a variety of spatial typologies and contextual conditions, enabling diverse modes of learning, living, and future adaptation. This approach not only facilitates personalized and collective learning experiences but also encourages the co-creation of spatial contexts and the dynamic reconfiguration of educational environments over time.

While spatial variety fosters inclusivity and diverse learning possibilities, density is often perceived in terms of physical space allocation. However, within the Kampung context, density is defined not by spatial constraints but by the intensity of activities and interactions. This framework reinterprets density as a catalyst for experiential learning, where the concentration of social and educational engagement transforms space into an active participant in the learning process. Rather than merely accommodating additional programs or functions, spaces are designed to facilitate dynamic exchanges, reinforcing the concept of the environment as the “third teacher”—a medium through which knowledge is shared, interactions are fostered, and learning becomes an immersive, communal experience.

Ensuring a safe learning environment is essential, and the Kampung offers a model of security rooted in community and social coherence. Rather than relying solely on physical barriers or surveillance, this framework promotes safety through spatial programming and design strategies that encourage natural surveillance, aligning with the “eyes on the street” principle. By integrating the learning environment within the broader community—engaging diverse groups such as teachers, students, staff, local vendors, and residents—security becomes an active, collective responsibility. This inclusive social fabric fosters a self-sustaining system of mutual care and vigilance, creating a conducive and supportive space for learning.

“Our site should be an Urban Lab” To test our hypothesis, we propose a site that embodies the complex dynamics of Jakarta’s urban condition—a living laboratory for experimentation and synthesis. Located in West Jakarta, the district of Tomang offers a unique intersection of formal and informal urbanism, making it an ideal testing ground for rethinking educational environments.

Tomang is one of Jakarta’s earliest areas to be shaped through private-sector-led development, resulting in a diverse urban fabric. It hosts a mix of commercial zones, leisure centers, student housing, and educational institutions, reflecting the vibrant energy of a student-centric neighborhood. Importantly, it is also home to an urban kampung—an informal settlement that borders two major university campuses: Trisakti University

This adjacency between the kampung and enclosed academic institutions creates a unique condition: a spatial and social threshold where formal education meets vernacular urban life. Surrounded by skyscrapers, high-rise apartments, and affluent residential enclaves, the kampung in Tomang becomes a microcosm of Jakarta’s contrasts. It is here that we envision the Kampung Education Hub—a catalyst for negotiating new relationships between the city, the kampung, and the university.

By situating our project in Tomang, we aim to explore how educational environments can move beyond institutional boundaries and become active, embedded agents within the city. The site offers the ingredients to test our central question:

“Can vernacular, community-based learning environments coexist and evolve alongside formal

This setting challenges conventional campus design and encourages the development of an engaged, adaptable, and socially responsive educational typology—one that grows from the

The site is surrounded by multiple conflicting interest from the enclosed campus area, the informal kampung behind, even the gated high-end residential complex all competing for a dominant role on the urban grid.

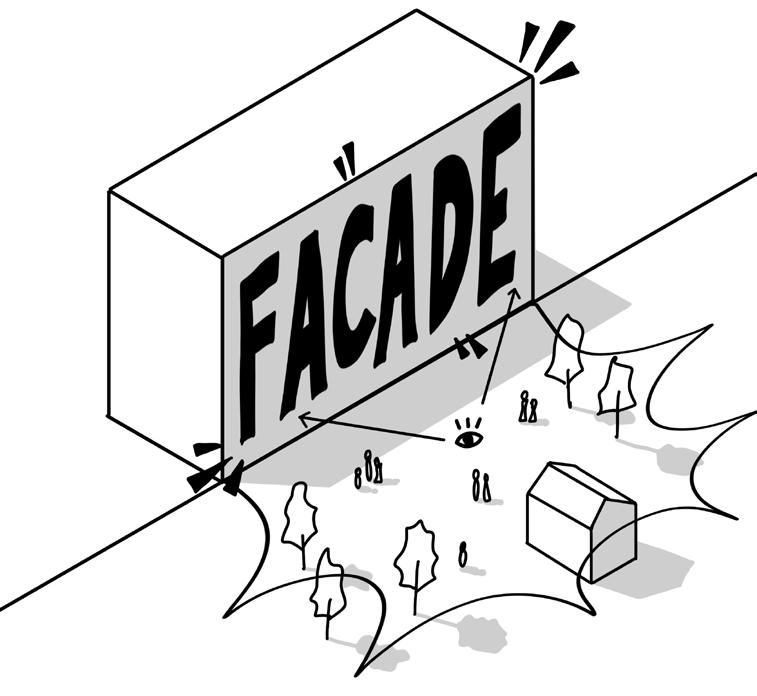

The campus, enclosed by perimeter walls, reflects an intent to remain sterile and isolated from its surroundings—establishing a “safe” learning environment that is detached from the urban realities just beyond its borders.

The areas around the campus are lively, composed of small-scale commercial programs and residential zones. Yet, this vibrant context remains largely disconnected from the campus itself, creating a sense of detachment for faculty.

“Hole” on the wall this phenomenon founded on the side of the campus wall adjacent to the Kampung area emphasize the paradox of Kampung and the City. As students depends a lot on the Kampung that provides easy and economically viable access to

printing, supplies, food, and etc. Thus they created these holes on the campus wall in order to echange goods without actually leaving the campus area.

The Kampung Education-Hub is strategically positioned at the threshold between the enclosed university campus and the surrounding urban fabric. Rather than reinforcing this divide, the project reimagines the border as an exploded, three-dimensional space—a permeable zone that invites exchange rather than exclusion. What was once a rigid wall becomes an active interface, engaging both sides and speaking to the city’s complexity.

Architecturally, the building embodies its values. It exposes the processes of learning and social production, making them visible and accessible. By projecting educational life outward, it asserts that learning is not confined to isolated institutions but is inherently urban and public.

From the city’s perspective, the building appears as a section cut—a revealing slice through the architecture that displays its inner workings. This visual transparency invites multiple modes of engagement: physical interaction, visual connection, and ideological dialogue. The façade becomes a dynamic stage for urban life, drawing in passersby and encouraging participation, reinforcing the idea that education belongs not behind walls, but at the heart of the city.

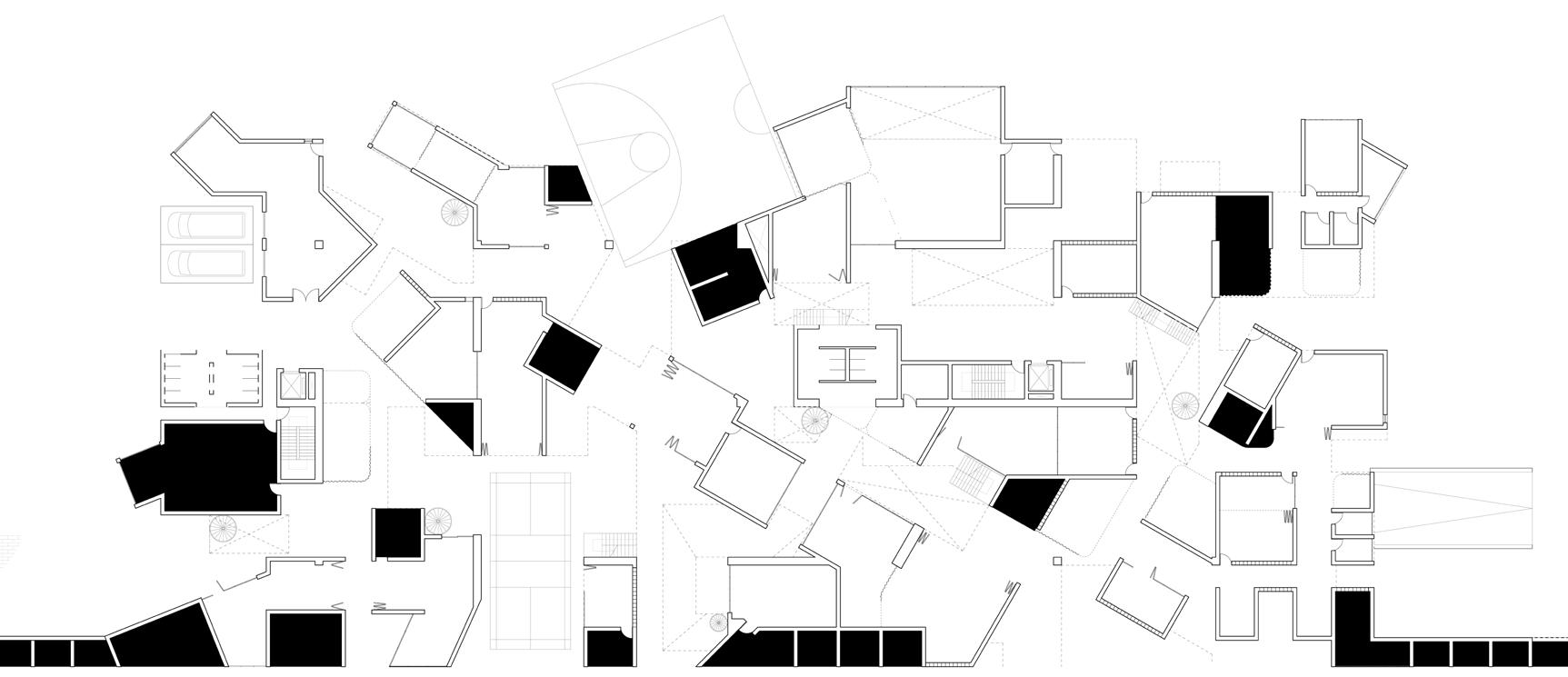

The Kampung Education-Hub employs a diverse range of geometries to reflect the idea of orchestrated chaos—a spatial principle drawn from the informality and adaptability of kampung environments. This controlled disorder polarizes the learning spaces, compelling the surrounding city to engage, adapt, and negotiate on multiple levels.

Each geometric form responds to varying scales, typologies, and degrees of openness, enabling a flexible framework for learning environments. This creates endless possibilities for spatial configuration, accommodating different modes of education and community interaction.

A lightweight mesh façade reinforces the duality of transparency and enclosure. It opens the building to the city, while also addressing climatic and environmental needs specific to Jakarta. Beyond its visual porosity, the mesh acts as a passive ventilation system and a protective barrier against mosquitoes and insects, ensuring that semi-outdoor spaces remain safe, comfortable, and conducive to learning.

The architecture asserts itself within the city—not as an isolated object, but as a form in dialogue. It projects its intent outward, initiating a conversation between learning and urban life. Rather than retreat into critical distance, it takes a projective stance: one that engages, provokes, and participates in the city’s evolving narrative of space, education, and identity.

The existing campus embodies the legacy of Western modernist urban planning—an enclosed, sterile enclave modeled after European city ideals, detached from its immediate urban and social context. This spatial ideology reflects a top-down approach to knowledge and space, isolating education from the complexities of everyday life.

In contrast, the Kampung Education-Hub proposes a vision rooted in post-colonial urbanism—one that asserts learning environments must emerge from local conditions, socio-economic realities, and community dynamics. It challenges the imported modernist model by embracing the informality, adaptability, and communal values of the kampung.

Juxtaposed against the neighboring campus buildings, the Education-Hub creates a stark contrast between the clean, uniform language of modernism and its own pixelated, organic form. This visual and spatial tension becomes a productive dialogue—one that redefines the future of education as embedded, participatory, and site-responsive. Here, learning is no longer confined within walls, but is reimagined as an urban act, shaped by and for the people it serves.

The organic form of the Kampung Education-Hub is a deliberate intervention—designed to disrupt the rhythm of the surrounding modernist campus architecture. It acts as both a statement and a provocation, signaling a shift toward a new spatial ideology rooted in the principles of kampung education: openness, adaptability, and community engagement.

This form invites faculty, students, and local residents to move through, within, and around the structure—encouraging exploration, interaction, and participation. The architecture becomes a medium of exchange, where the campus merges with the city, and the city becomes part of the campus.

In this blurring of boundaries, learning is no longer confined by walls, classrooms, or rigid hierarchies. Instead, it unfolds as a fluid, immersive experience—a platform for communication, dialogue, and collective authorship.

The architecture stimulates the senses and provokes thought, enabling a kind of learning that is autonomous, experiential, and continuous. It embodies the essence of meta-learning—a space that encourages curiosity, adaptability, and the exploration of possibilities beyond formal instruction.

“The Plan is the generator. Without a plan, you have lack of order and wilfulness. The Plan holds in itself the essence of sensation. The great problems of tomorrow, dictated by collective necessities, put the question of ‘plan’ in a new form. Modern lifedemands, and is waiting for, a new kind of plan, both for the house and for the city.”

-Le Corbusier,

1920

The essence of the plan as stated by Le Corbusier acts as generator, asserting that the plan itself holds the potential to structure not just space, but society itself. It defines how people live, move, and interact. In the context of the Kampung Education-Hub, this idea is reimagined—not as a blueprint for order, but as a framework for possibility. Here, the plan becomes a tool to cultivate knowledge, provoke curiosity, and support diverse forms of social interaction.

Rather than following the rigid, orthogonal logic of the modernist grid, the plan of the Education-Hub is composed of organic, overlapping forms—a series of ambiguous spatial boxes that shift, pivot, and collide. This deliberate disorder introduces spatial ambiguity, encouraging users to interpret, reconfigure, and personalize their environment. In doing so, the architecture promotes active learning—not just within classrooms, but across thresholds, corridors, terraces, and voids.

This unpredictability is not chaotic; it is self-sustaining and self-restraining. Boundaries are implied rather than enforced, allowing for a porous, adaptable structure that grows with its users. Learning unfolds in layers—formally and informally, intentionally and serendipitously—reflecting the rhythms of everyday life in the kampung.

In a time when education increasingly requires collaboration, adaptability, and critical engage-

ment, the plan must evolve accordingly. The Kampung Education-Hub proposes a new typology: a learning environment that rejects the sterilized isolation of institutional design and instead draws inspiration from vernacular spatial intelligence. It leverages the organic, improvisational logic of the kampung to produce spaces that are inclusive, participatory, and embedded in their urban context.

Ultimately, the plan is not a static document but a living system—a spatial proposition that shapes, and is shaped by, the people who inhabit it.

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

If the plan is the generator, then the section is the activator—bringing the latent potential of the plan into lived, spatial reality. It extrudes the conceptual logic of the plan into three-dimensional space, creating layered environments that operate across scales and levels. The result is not a hierarchy of functions, but an ecosystem of interdependent pockets—voids, terraces, volumes, and in-between spaces that constantly negotiate with one another.

In this vertical choreography, the section becomes a diagram of spatial simultaneity. Learn-

ing is no longer confined to discrete rooms or programs—it becomes ambient, autonomous, and ever-present. Each space hosts its own micro-events of knowledge production, social interaction, or quiet reflection, all unfolding concurrently. The building lives and breathes as a multi-level urban organism, where everything can happen, everywhere, at any time.

This layered condition aligns with the logic of kampung urbanism, where boundaries are blurred, levels are opportunistic, and no space is left inert. The section celebrates this spatial ambiguity—stacking, folding, and revealing moments

of encounter and discovery that animate the architecture beyond its surface.

In this way, the section is not just a representation of the building’s form, but a manifestation of its pedagogical intent—a spatial manifesto of active, decentralized, and experiential learning.

The ground plane is not merely a horizontal surface—it is a social condenser, a polarized and porous terrain that invites interaction, negotiation, and occupation. Far from being a passive floor, it is an active threshold between the city and the architecture—ambiguous in form, but intentional in effect.

It blurs the boundaries between public and institutional, inside and outside, formal and informal. This porosity transforms the ground into a mediating space—a place where students, locals, and urban dwellers converge. It becomes the first site of learning, not through instruction, but through engagement, encounter, and exchange.

By embracing unevenness, openness, and multiplicity, the ground plane acts as the social and spatial foundation of the Kampung Education-Hub—a platform where learning begins not with walls, but with interaction.

The alley is not a static corridor—it is a living, playful artery that adapts and transforms with its users. Acting as both passage and place, it channels social energy, informal learning, and communal interaction. Like its kampung counterpart, the alley resists singular definition—it is fluid, reactive, and ever-changing.

Within a single day, the alley can host a morning yoga session, shift into a casual café or study zone, transform into a workshop or lecture space by midday, and become a lively evening hub for street food, conversations, or spontaneous gatherings. These layered scenarios highlight the versatility and temporal richness of the space.

Just as in the kampung, the alley embodies a kind of spatial improvisation—where architecture sets the stage, but people and time complete the performance. It is this quality of responsive ambiguity that makes the alley not just a passage, but a site of learning, living, and play.

When the playful alleys are stacked, they form a network of overlapping spatial intersections— voids that punctuate the structure across levels. These pockets become light wells, view corridors, and ventilation shafts, regulating the internal environment while enriching the sensory experience.

The result is an organic vertical landscape, where space is shaped by movement, encounter, and openness. Much like the kampung, these pockets emerge not from a rigid plan, but from accumulated layers of use and adaptation. They foster transparency, dialogue between floors, and an atmosphere of informal connectivity.

This vertical porosity turns the building into a living section—one that breathes, sees, and communicates.

As illustrated in the diagram on page 101 (top), the existing campus wall is already activated by small-scale commercial stalls. Rather than rejecting this condition, the Kampung Education-Hub embraces and incorporates it, stitching these informal programs into its own spatial fabric.

The black zones in the diagram represent these embedded stalls—micro-programs that introduce a spectrum of activity into the building. By integrating local commerce, the project blurs the boundaries between institutional and public, formal and informal.

This hybridization creates a layered field of publicness—a series of gray zones that support both learning and community engagement. These shared spaces encourage interaction between students, faculty, and the surrounding society, fostering a campus that is not isolated, but interwoven with the life of the city.

The Kampung Education-Hub promotes adaptability through a diverse range of small to medium-scale spaces, designed to be joined, divided, or reconfigured as needed. This built-in flexibility allows the architecture to respond to changing programs, user needs, and temporal shifts—offering endless possibilities for spatial use and engagement.

At the top, the semi-outdoor rooftop functions as both environmental and programmatic buffer. Equipped with an adjustable soft shading system, it responds to Jakarta’s hot and humid climate, adapting its degree of openness throughout the day.

This dynamic rooftop becomes a versatile platform for learning, gathering, or leisure—a responsive space that enhances comfort while encouraging social and educational interaction.

Louis Kahn said, “School began with a man under a tree, who did not know he was a teacher, discussing his realization with a few, who did not know they were students,” This thesis in its whole proposed an open-ended idea of creating a new typology of architecture that acts as an orchestrated piece of tree capable of knowledge and social reproduction. Exposing itself to the city thus making learning an urban lifestyle.

-Kampung Education-

Gotong Royong in Bahasa Indonesia means “Working Together”

This thesis project would not have been possible without the guidance, assistance, and help of the following people

Advisor: Kane Yanagawa

Shelly Stefanie

Jeovanna Ernie

Kennard Willard

Justin Hung

Ricky Chiu

Edward Lee

Michel Lyn

Jenna Kenisha and others

The Gotong Royong provided critical insights and engaging discussion that inspires this thesis to be bought to life.