Spring 2024. Copyright © 2024. The Journaling Collective.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used without written permission of the copyright owners.

Please scan this QR code to access a digital version of this anthology, including an audio version for those with visual accessibility needs.

ISBN: 978-1-7383996-0-4 (e-book)

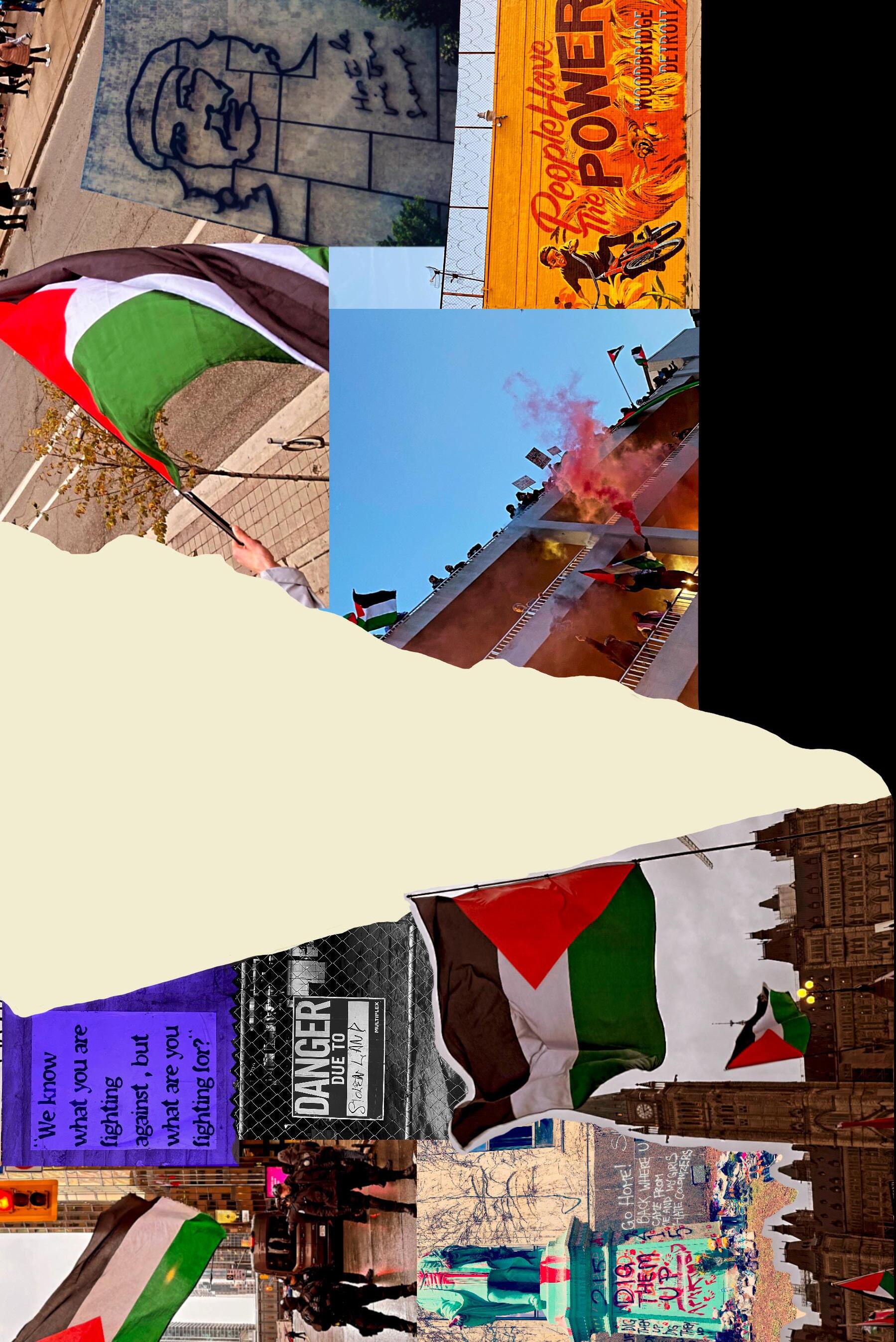

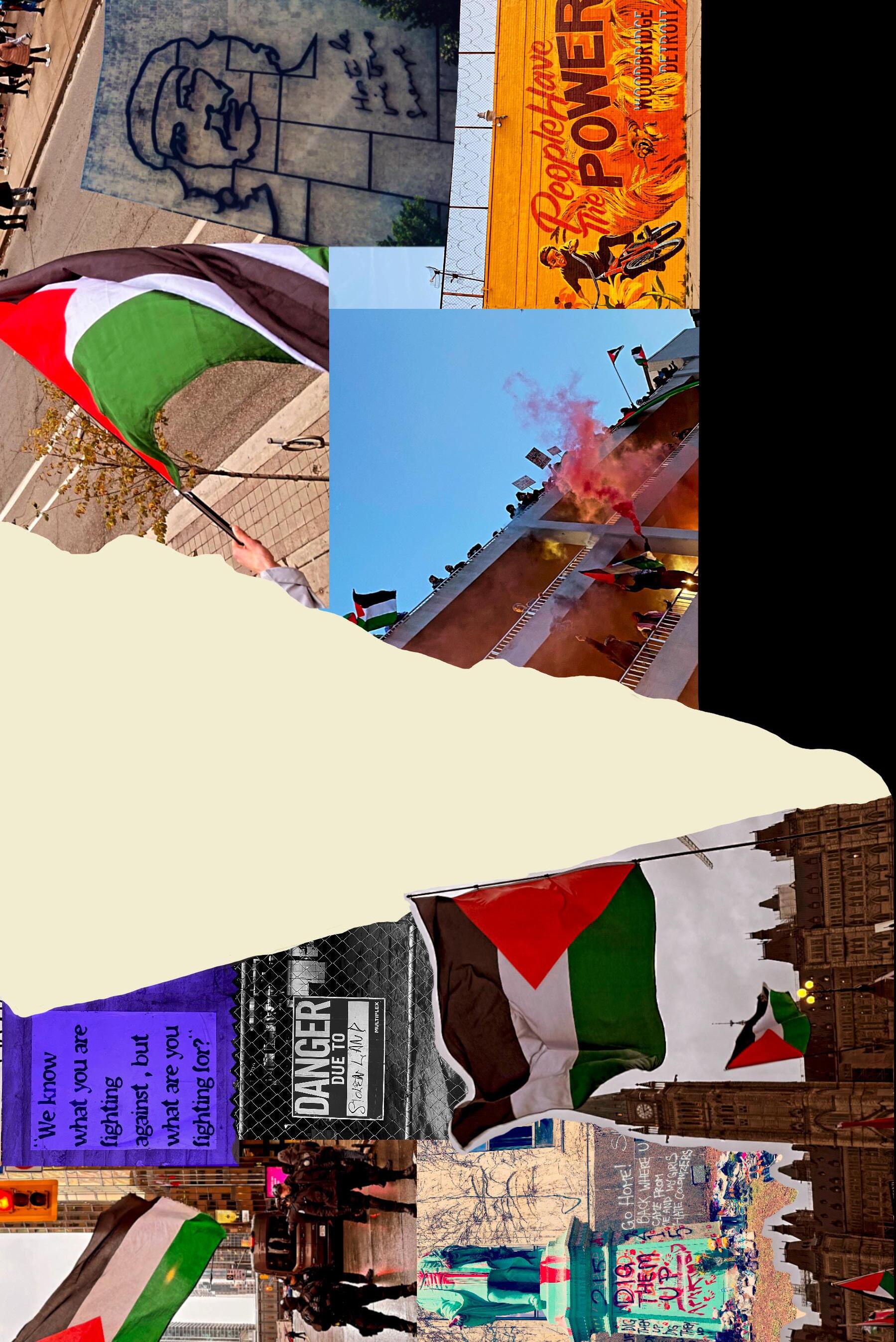

Part 1: Pulse of Dissent

by The Journaling Collective

Sowing Solidarities

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the people who provided invaluable gifts throughout this collective process of dissent and resistance:

First and foremost, Nanky Rai, our comrade who guided us with wisdom and laughter. They challenged us to do better by our communities over our 4 years at The Med SchoolTM They stuck with us throughout this whole process, editing, re-editing, and re-re-editing, giving us sparkles of joy throughout.

AK, who provided much-needed accessibility guidance.

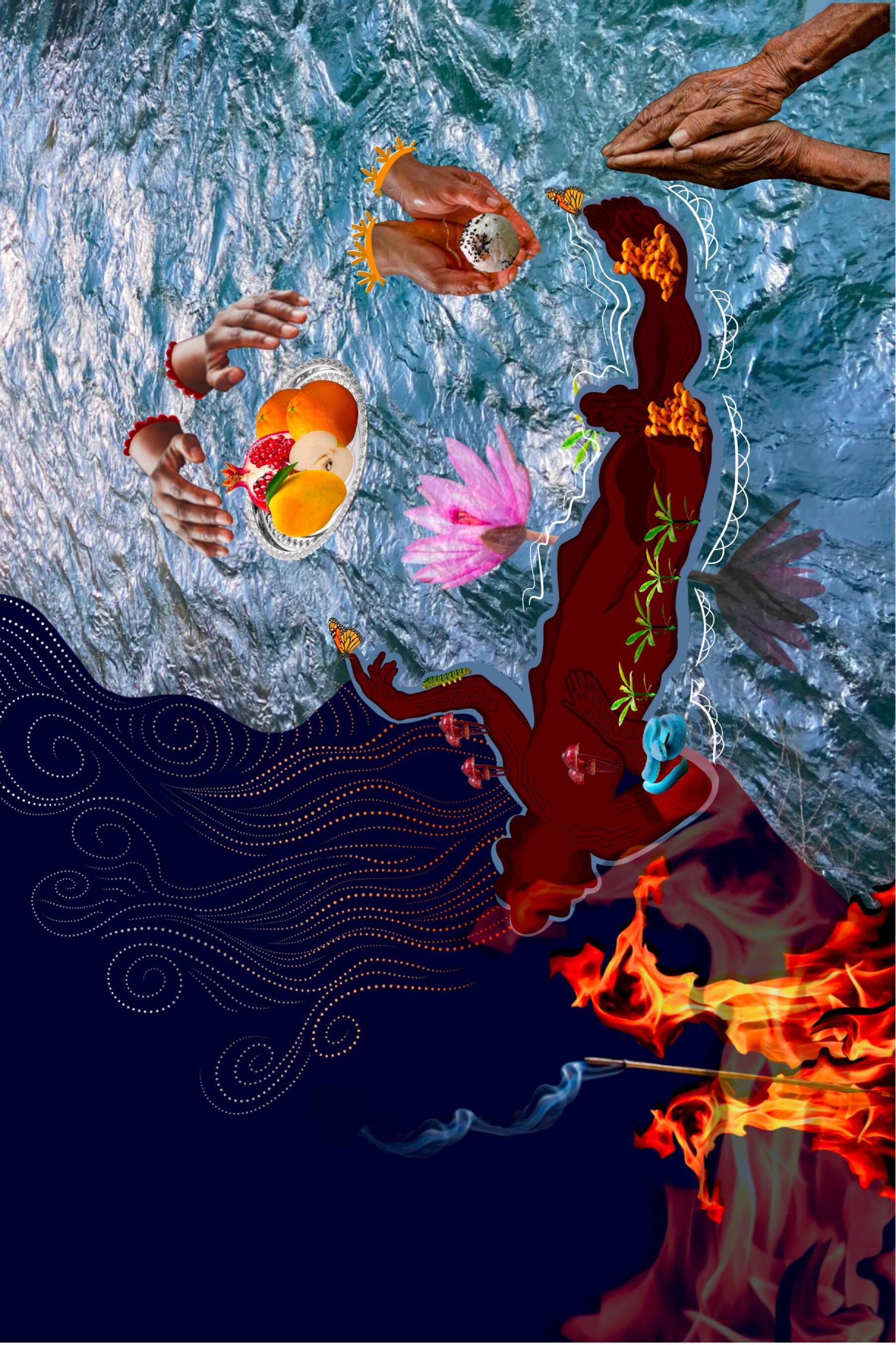

Pardis Pahlavanlu, the artist for the liberation-filled cover pages of this anthology.

Sara Kloepfer, our diligent copy-editor who combed through our pages.

Soma, our speedy printer who bound our colour-filled pages into one collective spine.

Bahar Orang & Jody Chan, who drew us into reflections on balancing the vastness of creativity and the practicality of structure as this anthology blossomed.

Tahmina Reza, who engaged us in the world of written word, speaking with us on the intricacies of the editing process.

The Public, who housed us in their studio that allowed the fruition of a multiplicity of collaborations.

The Kim family, who housed us in their warm and spacious home and left us filled with deliciousness.

& finally, each other – each person brought in their bold and beautiful spirit. We brought with us intention, commitment, and dreams that we continue to carve into goals. While not all who are in the Journaling Collective were part of this anthology, your contributions will never be forgotten.

And wait! We can’t forget Luna! Our doe-eyed emotional support dog.

4

Seeding Sovereignties

Seeds resist.

Seeds carry the stories of generations past, present, and future. They hold our futurities.

They are passed on from one generation to the next, just as our inherent right to liberation and sovereignty are. They, like peoples, are rooted deeply in the soil, nurturing a beautiful resistance, healing the land, healing the people.

The corn kernel gleams, goldened, emboldened, by Sun’s rays, melting into the worldly soil of Turtle Island, roots stretching, twisting, criss-crossing, from the lands of Wet’suwet’en to the waters of Mi’kma’ki.

The olive seed, lines stricken, draws timelines of the generations of Palestinians who will continue to save and grow it.

The spherical okra seed shows us the Sudanese peoples’ infinite years of resistance.

The mushqbudji rice seed’s pointed ends teach us the poignancy of Kashmir’s self-determination.

Our experiences as medical students studying in Tkaronto are intrinsically tied to our identities as settlers on lands that should remain under the full jurisdiction of the Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and the Mississaugas of the Credit nations. Coming from nations and homelands that are shaped, depleted, and exploited by imperialism, we recognize the ongoing and unique impacts of settler colonialism that we are participating in here. We see the links of the plight and resistance of Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island with those of Palestine, Sudan, Kashmir, The Congo, Haiti, Puerto Rico, and all oppressed sovereign peoples across the world. We commit to addressing our complicity in settler colonialism by remaining in direct opposition to colonial violence and striving to practice solidarity with Indigenous peoples, always.

5

Mandaamin

Corn Turtle Island

Shajarat Zeitoon

Olive Tree Filasṭīn

6

Nabat al-Bamya Okra Plant Sudan

Nabat al-Bamya Okra Plant Sudan

7

Mushqbudji Kashmiri Rice Kashmir

Who we are

We are a collective of 10 graduating students from The Med School™, but contrary to the establishment’s imposition, we are so much more than: we are siblings, children, caregivers, organizers, lovers, survivors, community members, dancers, movers, singers, artists, poets, and writers. We come from an array of backgrounds, upbringings, and experiences of race, sexuality, gender, class, disability, and migration. Our personal and collective experiences of white supremacy, classism, cisheteropatriarchy, ableism, casteism, and imperialism have shaped our journeys and influenced our perspectives towards medicine.

This anthology has a birth story of its own, and took on many stumblings and bendings before settling in the form before you today. The anthology contains reflections of students who started medical school in the midst of a global pandemic and a reckoning of global anti-Blackness and state-enacted racial violence. While we were being welcomed to the ‘wonderful (virtual) world of medicine,’ Western imperialism’s blood lust for profits delayed access to COVID vaccines globally. While we attended lectures on personal lifestyle changes and the biomedical etiology and treatment of disease, that same education was using ‘race science’ to justify the disproportionate deaths and illnesses impacting Black and brown communities. As we write this, the most structurally dispossessed communities continue to remain subject to disproportionate exposure, sickness, and death from the structural complications of racial capitalism.

As students dedicated to anti-colonial approaches to health/care, we have supported each other through an inaccessible education system meant to mould us into professionals who often harm the communities we come from. We supported each other when we saw our parents, our community members and even ourselves represented in our curriculum only as subjects of deviance, disease, and subjugation. We are also shaped by our experiences in hospitals where we bore witness to the beautiful and painful complexities of birth, death, and all that comes in between. The stories we have been gifted from patients, those still with us and those not, will stay with us. This anthology is for them, too.

While many of us belong to dispossessed communities, we also carry immense privilege and access to resources as medical students. The capital (both economic and social) that brought us here and continues to prop us up cannot be ignored. For each of us, our place in medical school and therefore

8

in this anthology was brought about by the violence of white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, settler colonialism, casteism, and ableism. There is much we still have to learn and unlearn about our power in this world. We commit to remaining in allegiance with the wretched of the earth, not the medical industrial complex.1 We strive to lend ourselves to movements committed to dismantling medical violence by fighting for non-reformist reform, uplifting self determining care and engaging in resistance towards liberatory futures.2

This anthology is sectioned into two parts. The first is Pulse of Dissent, which speaks to truth telling. Here we hope to share our experiences and expose the fleshy parts of medical learning that are often kept behind closed doors and stifled tears. We firmly believe that our lived experiences are valuable, fertile sources of information. Part two of the anthology, Beats of Resistance, is where we challenge ourselves to do the serious, difficult work of imagining just futures. We sew threads of the individuals, communities and movements who inspire us, who labour better futures every day. From abolitionist organizing to disability justice to trans liberation and a Free Palestine, we have worked to sow seeds of solidarity and resistance, in little ways and in big ways, too.

We have presented our truthful reflections, in the spirit of the Combahee River Collective, who taught us that “from the personal, the striving toward wholeness individually and within the community, comes the political, the struggle against those forces that render individuals and communities unwhole.”3

To everyone reading this, thank you for engaging with the work our hearts have been pulling us to do over the past few years. We hope these pieces express our joy, our rage, our humour, our dreams, and ultimately, our truths.

9

Dedication

To community: Thank you. You have shaped who we are. We hope these pages affirm and validate that which you intimately know to be true about the medical industrial complex. We hope our rage, love, and commitment to uplifting you and all justice-seeking communities is palpable. We thank you for being our teachers. Our commitment to medicine is a commitment first and foremost to land sovereignty and collective selfdetermination. We thank you for keeping us grounded in that responsibility, knowingly or not.

To health students, past, present and future: We hope you feel seen and heard in these pages. We hope this work offers a language to articulate some of the discomfort you may have been feeling about your education — both what it is and what it isn’t. We hope you feel motivated to connect with others, demand better for yourself, and engage in resistance in ways both big and small.

To ourselves: One of us said it best – this anthology is a manifestation of what we needed in this particular time and in this particular context. We hope it serves as an archive of our experiences, our joys, and our hopes for the future as we complete this chapter of our journey. We shared a complicated 4 years together processing it all. We hope, as we move forward into residency, that this anthology serves as a contract to which we can hold our future selves accountable. We have faith in us, and we’re watching us, too.

10

Content Warning

Please be aware that some of the material in this anthology includes subject matter that may trigger some readers. Our decision to include such material is not taken lightly. These topics include: genocide; selfimmolation; forced hospitalization and medical violence, including within the psychiatric system; suicide; institutional and interpersonal violence rooted in anti-Blackness; settler colonialism; transphobia; ableism; fatphobia; and death and dying.

We have done our best to notify you of potentially triggering content at the beginning of specific pieces. We invite you to engage with these works in the ways that flow for you.

of

5 Seeding Sovereignties 8 Who we are 12 Rice Bowl 13 “Land Acknowledgement” 14 Cognitive Dissonance 16 To our future co-conspirators 19 POC Gate: Representation is not Resistance 22 Racism IN / Racism OUT 26 [sic] 28 Rest is Medicine 33 Wellness Ableism in Medicine 34 soul loss 36 Lost in Foundations 38 In Conversation: Fatphobia in the Clinic 42 Social Justice Warrior 43 Discharge Summary 46 deviant disruptors causing disorder Flip over to back cover for Part 2

Part 1: Pulse of Dissent Table

Contents

Rice Bowl

lunan 芦楠

Imagine a book on a shelf in your house. You reach for it. Toronto Notes. You flip through every page. You see yourself in a bright white coat in a dimly lit room.

A patient lies on a hospital bed; their skin as faded as the light; your skin too visible. Professional.

You see yourself, laptop open, sitting in a grand lecture hall, unable to see or comprehend the great name booming at the lectern. Medical Expert.

You see yourself standing by a laboratory bench, wondering what an amino acid looks like, how it tastes. Scholar

You see yourself sitting in a corporate board room, expected to draft an EDI policy, unsure why it matters whether your words fall under this heading or that, unsure what your words even mean, but fearing being flagged. Leader, Communicator, Collaborator, Advocate.

Imagine yourself, as you enter medical school. You learn your value is your performance. You feel dissonance. Competition seems to be the only way to survive. You hear whispers of those who were erased for not performing. You fear.

So you infuse your blood into clinical notes, publications, titles, only able to focus on climbing the next rung of the ladder. If you are fortunate, some disease or finding will be named after you.

How can you dream of alternative realities?

Imagine now, this anthology on your dinner table. Beside the journal is a bowl of rice – whole, overflowing, and full of yum.

You dream that yum is not scarce.

You exist, you flow, you breathe gently, as you flip through these pages.

12

“Land Acknowledgement”

See Part 2, page 40 for references

13

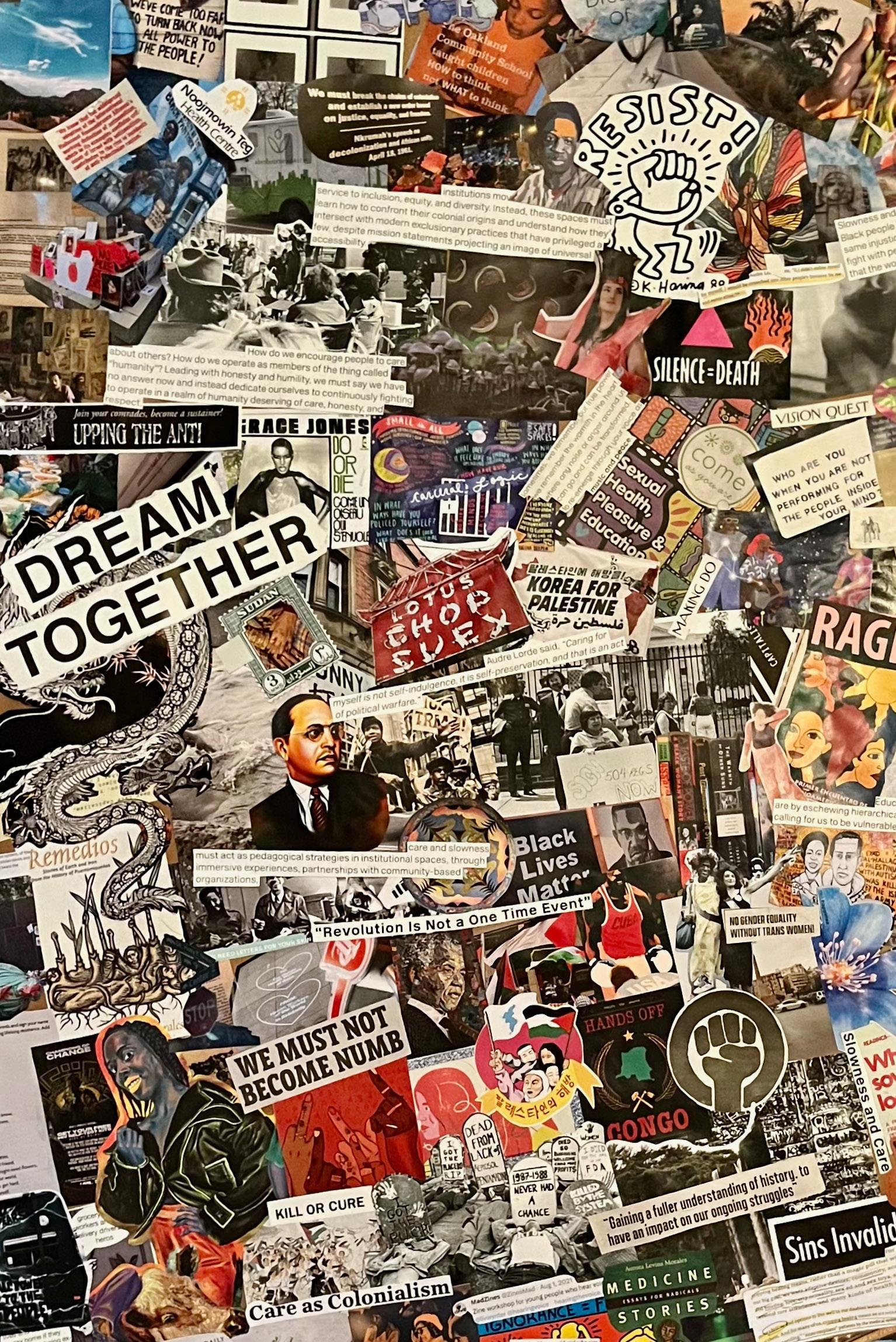

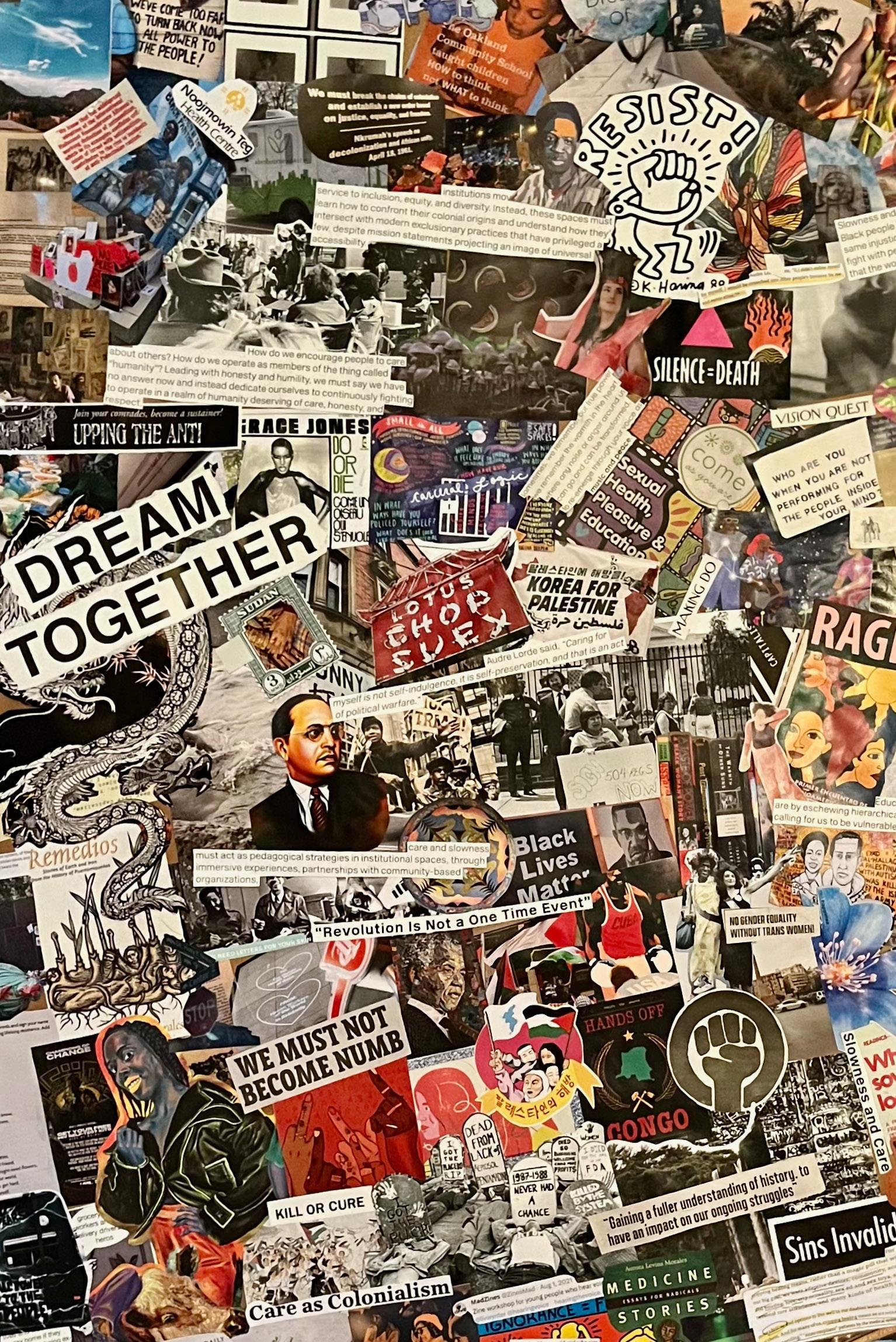

Cognitive Dissonance:

Clippings from our Collective Journal

…global health seems to re-enforce the portrayal of the world as “rich/civilized” countries versus “poor/disease-infested” countries, without discussing the colonialism (both present and historical) that continues to under-develop the Global South.

There’s no mention of the countercurrent, of people defining it for ourselves, claiming agency over this notion of gender, particularly for individuals/communities who are redefining gender according to their own terms.

When we discuss nutritional factors, such as iron and folate, why do we not discuss the oppressive histories and experiments? e.g. The SickKids hospital-based Nutritional Experiments on Indigenous Children in residential schools in the 1940s were only acknowledged 3 years ago.¹

…willingly told that it is okay to reduce life expectancy in people who use substances…“I would consider it a miracle if this patient came back in 5 years for a valve replacement” just shows the extent to which our system is betting against certain lives and surviving is inherently a fight against the very people/system that is meant to help you live longer, healthier lives.

it gets embedded into how healthcare providers conceptualize diseases, and how one then views patients who are unable to control these various factors as a personal failure/noncompliance.

incorporated labour rights occupational health perspective… At the same time, a larger discussion on structural factors affecting workers’ health through the lenses of environmental justice and capitalism are still needed.

Currently feeling like there is a constant sense of through small group classes, or social media…

Specifically, I was reflecting on how generations of genocide and colonialism in Canada have aimed to break apart Indigenous family structures, suppress and extract Indigenous cultural , and further the ongoing psychological trauma of racial narratives… I wonder why we do not discuss how we as Canadian medical students benefit from colonialism.

thinking a lot about how manifestations of sex outside the binary are not only medicalised, but pathologised and intervened upon.

Discussion of the duty to disclose without consideration for how medical professionals have contributed to the discriminatory practices of Children’s Aid Societies, which disproportionately police Black, Indigenous and Racialized families was unsettling.²

I’m feeling like the learning is very narrow in medicine but don’t know how to balance that with learning things traditionally considered outside of medicine…

“why do we need estrogens in men?” and “why do men produce progesterone?” essentialist and binary narratives are so ingrained in our understanding of sex and hormones… there is a lack of acknowledgement that levels of such hormones vary significantly in people of all sexes, and doesn’t at all manifest in a binary way.

…women, racialized, Black patients are continuously not believed when they say they are in pain and are chronically undertreated as a result...I wish we had some more time to also unpack biases associated with how we expect pain to be communicated and shared.³

please stop assigning a gender to body parts.

“It is important to remember that you do not need to be certain that abuse has occurred. You will almost never be certain. If you have any suspicion or reason to believe abuse is occurring, you MUST report.” …I get the extent of harms that can be caused by not addressing abuse, but there's a strong assumption that CAS is a system that doesn't fuck people's lives up further. too many people don't know about the violence that Indigenous, Black and racialized youth, families, and communities are subject to.

This obsession with getting people “back to work” after injury or while living with chronic conditions and disabilities. It is really unnerving. The idea of someone being made “functional” enough to contribute to the capitalist system.

The patient in this case is made out to be a threat to others in a way that doesn’t represent the majority of people who would actually present with psychosis. It teaches us that we are meant to respond to situations like this with an immediate carceral and coercive approach.

people who experience psychosis are criminalized so damn often instead of being cared for. And why are we acting like the structural determinants of health don’t intimately shape distress.

…We’ll be ‘treating’ them, sedating and pacifying the harms that they lived through so that it’s no longer a burden to us, but the person continues to experience an assault on the psyche, this time, less visible, this time pacified enough so that society can put a peg in the pain that we have caused, put a peg in the bursting dam, representative of the structural oppressions that people are facing.

To our future co-conspirators,

Welcome, to the Zoo that is medical school! This place you peered into from the outside will consume your waking hours for the next 4 years. There will be times you will forget the confines you are in, and will need to pull yourself out to maintain a critical gaze. You will find yourself using your voice to ask critical questions and challenge the status quo. As much as your voice is a source of power, an outlet for the fire that burns inside of you, it needs a community to sustain it as well as to prevent you from burning yourself. In isolation, even a plant is limited in growth. Amongst a forest, the plants’ tangled roots communicate their needs and share resources to nourish each other: This is how you will survive medical training.

The Journaling Collective grew as a collaborative ecosystem to nurture our individual journeys in institutions not designed for us. To resist our erasure.

This anthology started as a group of 15-20 students who were initially brought together by a faculty member and their piece on Uprooting Medical Violence.1 This collective was built on a shared praxis of radical solidarity and anti-oppression. We chose to connect around a collective journal (hence, “The Journaling Collective”), where we documented our reflections on the curriculum (both explicit and hidden). Quotes from our journals can be found on the pages before this letter. We later realized that the collective also gave us the space and structure necessary to support our dissent, cultivate resistance, and inspire liberatory action in solidarity with communities outside the ivory towers of academia. The Journaling Collective grew as a collaborative ecosystem to nurture our individual journeys in institutions not designed for us. To resist our erasure.

But collective work that is nourishing, supportive, and oppositional to the demands of capitalism takes patience.

16

Change requires you to care for yourself, act within your capacity while embracing discomfort, and be accountable to your commitments.

Our collective was fortunate to find each other in the milieu of DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) liberals in medicine. We were perhaps even more fortunate to have a mentor, whose brief term as a faculty lead in 2SLGBTQIA+ health coincided with our first year. We leaned on them in every step of our journey, from drafting community guidelines, to navigating our emotionally turbulent training, to designing our anthology. We would not have coalesced in the way we did without their guiding presence. There are people who have moved through the training you will move through, who may have felt the things you will feel, and who may have spoken for the values you will speak for. A strong collective will lean on the wisdom of their elders. The path we took to this anthology is pock-marked with detours and dead-ends. On our laptops we have the husk of an app with 10 messages, in our calendars we have monthly meetings where we never got to the agenda, in our notes we have deadlines none of us ever met. None of these steps were a waste of time (OK, maybe the app was). But collective work that is nourishing, supportive, and oppositional to the demands of capitalism takes patience. Your paths, both personal and collective, will have inevitable divergences, confluences, and dams. Each of these steps should be met with gratitude. Change requires you to care for yourself, act within your capacity while embracing discomfort, and be accountable to your commitments. The institution will reward quantity and prestige, but resist the urge to do more because of the social currency it lends you. We all experienced it, and at times also succumbed to it. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t partake in institutional initiatives, it just requires you to be intentional about the goals of your work and where you lend your labor. There is only one of you but for the institution, we are all replaceable.

There is only one of you but for the institution, we are all replaceable.

17

Some of our growth in this collective included unlearning hierarchies and leadership approaches that stunt creativity. A plant needs someone to sow its seeds, to water it, and to protect it. Who does this may change with time, as the plant grows and the seasons change. We started with a trio organizing most facets of our journal. By third year, the trilateral leadership had almost entirely dissolved, with each member taking responsibility for our collective. A horizontal leadership led our collective.

As we near the end of our time in medical school, we are also laying the Journaling Collective to rest. We learned the importance of building something organically, originating from ideas dreamed and grown to fruition together. Just as we found each other from behind our screens, you too will respond to a moment in history that shapes how you come together.

Like natural cycles of life, this formation is being put to rest peacefully, but we are passing on its spirit, seeds sown for the next generation of resistors - you.

In solidarity,

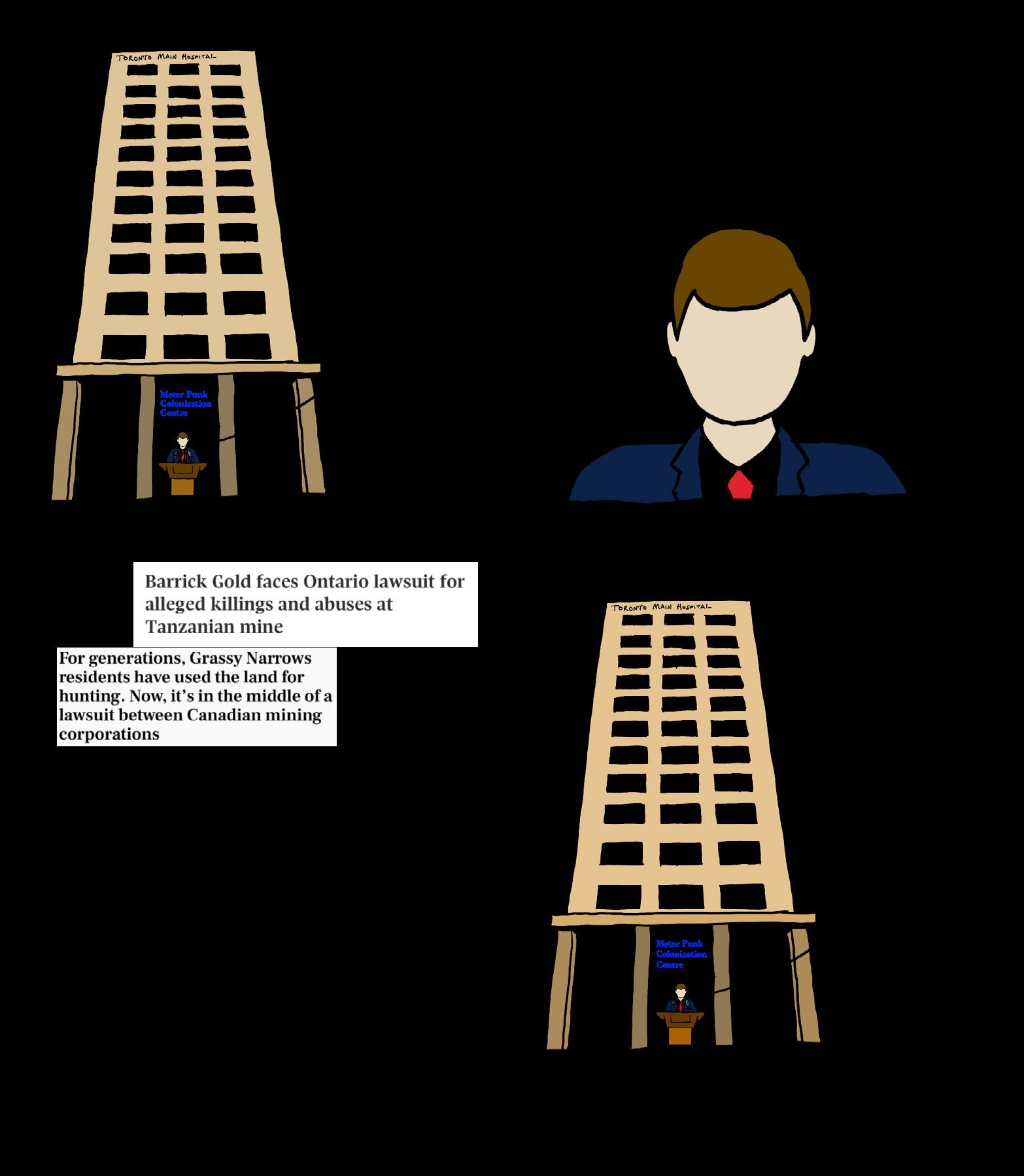

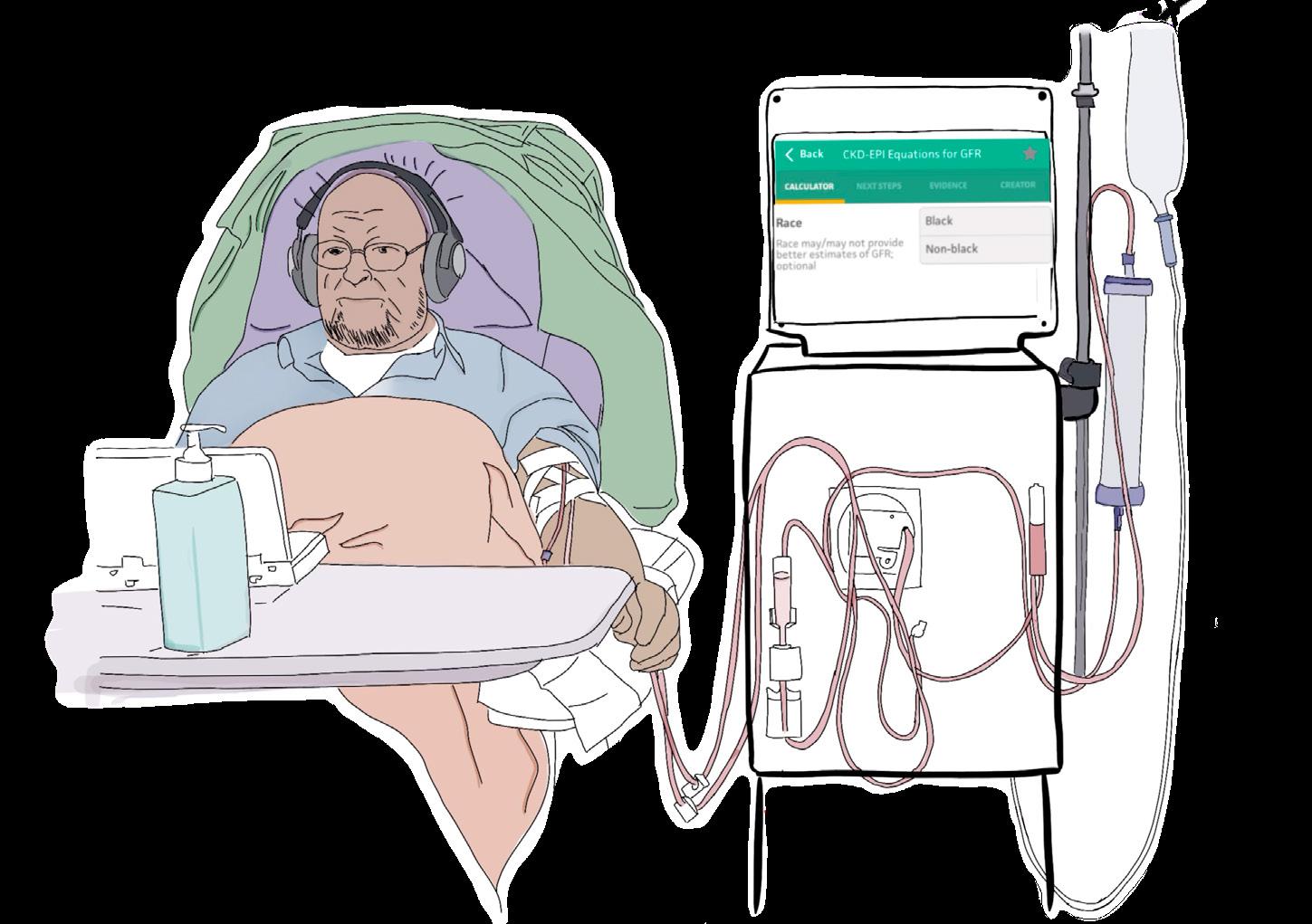

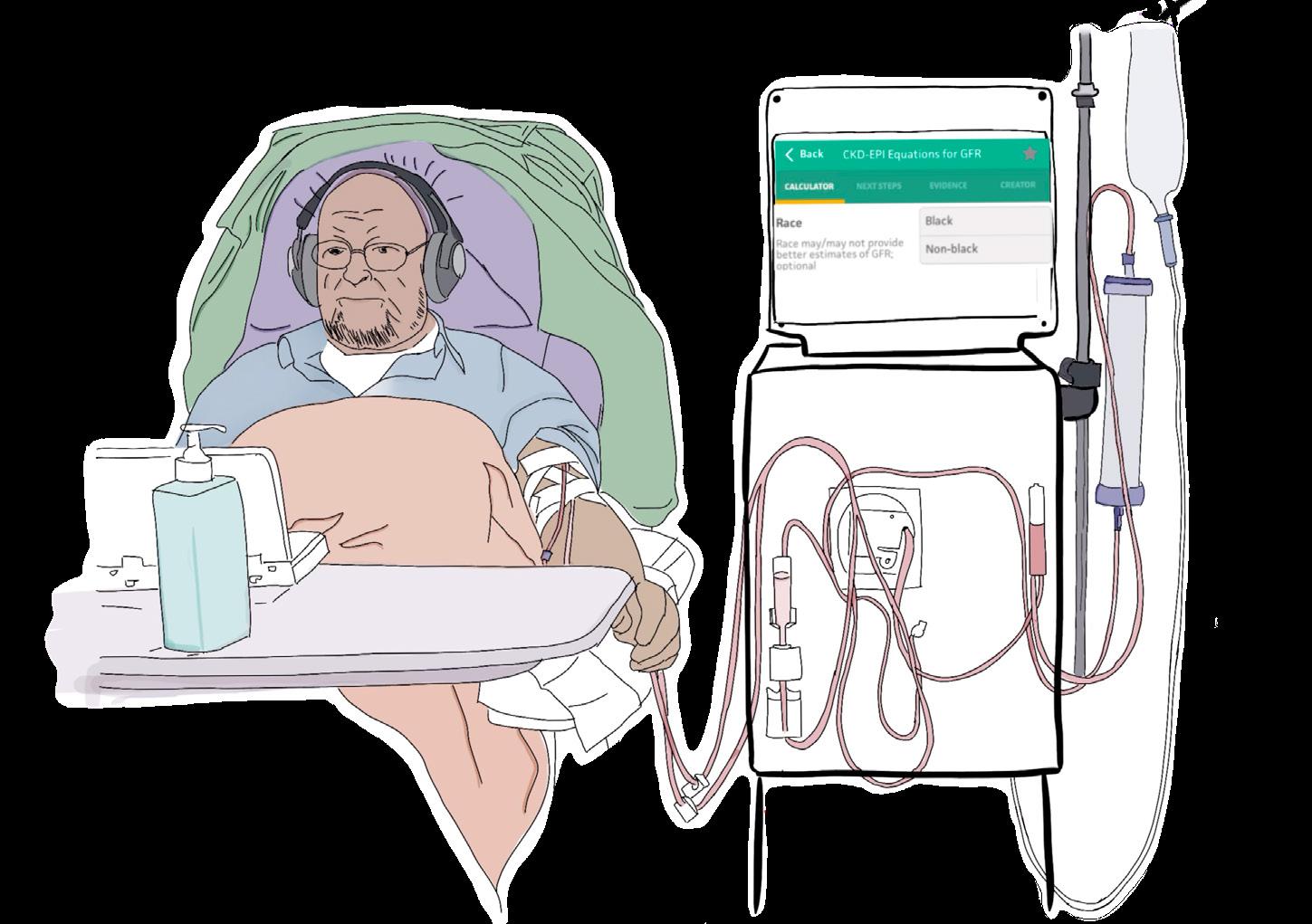

When learning about the lungs, we were taught about lung function testing. Members of the Journaling Collective raised concerns during virtual lectures about the use of race in the interpretations of these tests. As a result, The Med SchoolTM created an open access document to “discuss” how to teach race in medicine, including kidney function tests. Excerpts from this document are on the next page, alongside our own commentary, included as “talk backs ”

This discussion can be grounded in a wider commentary on people of color, respectability, and representation politics within the institution. A number of anonymous commenters referenced being people of color to legitimize their support for the status quo: racism in health care.

What happens when we prioritize memorizing “facts” rather than critical thinking?

Why do certain people not only accept but defend hierarchies in medicine?

As we see EDI (equity, diversity, inclusion) adopted within academia, we ask those in power to consider whether their allegiance is to community or institutions. We must remain wary of how identity politics can be used to uphold systems of oppression.

19

As important as this matter is and as a person of colour myself, I think the way this issue has been approached during the lectures by certain students is not appropriate. It has been brought up at multiple occasions, and sometimes without merit. And while our professors and tutors have been extremely kind at answering these questions (sometimes even at the cost of not covering educational material because of limited time), I have felt that it seems at times like professors are being bullied

I understand it is very important to feel inclusive and have the right to speak and bring up the issues to the faculty. But, sometimes I feel like things were blown up out of proportion and some students are focusing just on finding faults. This not only belittles the genuine concerns that we might have in future, but it distracts, takes our time from learning the actual topic that is being discussed (during lectures) and creates a toxic or hostile environment.

^ couldn’t agree more with both of these comments! Also a person of color

Have you ever thought of the toxic/hostile environment produced by teaching race science?

I am a person of colour myself and I feel like the PFT and quoting race correction as “racism” is beyond the context! And during this unprecedented time where we are feeling burnout and feel like in a doom of negativity, appraising every single word used by a professor or an example in an extreme negative and critical aspect is just not going to do any good! I know some of us are extremely passionate about discrimination and equality, but I think it shoudn’t be brought up at every single occasion. This is my humble opinion.

^ Also as a POC, I felt that the issues about race correction in PFTs were adequately addressed by lecturers (although it wasn’t in the slides or anything, it was talked about in sufficient depth).

This tells us nothing about your politics, but thanks for letting us know!

There is merit in looking at race when it comes to PFT!! Comparing people’s health to people who come from similar backgrounds (regionally, genetically, and geographically) is really important and needed! Looking at race is not always bad! I didn’t understand why this point about race was brought up in every single lecture and workshop?

Respectfully, we don’t think you understand what race means. Race ≠ biology and in fact, there are significant regional, genetic, and geographic variation amongst people of the same racial group

I am not against probing into racism in medicine. Let us say, I am interested in topic X and I bring that up in every single lecture that is possible, how will that look?! … If you are passionate and you find something is correct, ask the lecturer, after they have explained, if it is still unsettling-email them, talk to them at YOUR OWN TIME and if you come to an understanding and if you feel generous, share it with the rest. Everyone has their priorities, and be respectful of that... All I am saying is, don’t let your passion interfere with others’ learning.

Why is your time more valuable than ours or any patient that we will come across? Pretty sure we pay the same exorbitant tuition and have an equal right to engage with our learning. Not to mention the labour you expect to be done on your behalf and then "share with the rest"

... had to bring it up again and again and it sounded like their ulterior motive was to harass the lecturer

Sorry we should have considered the fragility of our lecturers while we defended the humanity and lives of our communities.

RACISM IN

We are taught that science discovers “truths” about our world. In medical school, we memorize facts and equations as objective truths. One of these truths is that race is biology. We do not learn to question the supposedly evidence-based methods informing our knowledge, including how we see and treat the lung, kidney, and body function of Black people.

Yet questioning cracks this ‘truth.’

Why do we assume Black kidneys are different from white kidneys? What results from assuming?

The story of the eGFR is a story of the power of advocacy to challenge what is accepted as fact. eGFR, or estimated glomerular filtration rate, is used to measure the efficacy of our kidneys and monitor any decreases in their functioning. The way we “estimate” the glomerular filtration rate is by using the amount of creatinine in the blood — the more creatinine that is in the blood, the less effectively your kidneys are working. We assume. We have developed “formulas” over the years to better our estimations. Until 2021, race was also used as a variable in these calculations.1 As a result, two individuals of different “races” with the same blood creatinine levels are calculated to have different kidney function.

22

The socio-historical context within which we conduct scientific research is one of the many factors influencing our construction of reality.

New data shows this formula over-estimates kidney function by approximately 16% in Black patients.2 What results is that we overlook kidney injury, delaying access to medically necessary kidney transplants, such as dialysis and kidney transplants for Black people.

The basis for this comes from studies in the 1970’s that found higher amounts of creatinine in the blood of Black patients. This finding was attributed to a “naturally” higher muscle mass. Minimal research was done to investigate why or rule out other factors.3 Why was it so easy to explain this away by assuming all Black people have more muscle mass? Why was this so easy to accept? We seem to have a collective amnesia that this same argument was used for the transatlantic slave trade and the labour exploitation of Black peoples. The socio-historical context within which we conduct scientific research is one of the many factors influencing our construction of reality.

Our textbooks and lectures omit this history. The foundations of the nation states of Canada and the US exist on the exploitation of Black people, so too does our medical knowledge.

In 2021, while we were in medical school, a collective effort led by American medical students, physicians, and community members, many of them racialized and Black, successfully advocated for the National Kidney Foundation to remove “race correction” from the eGFR calculation.1 eGFR is also a story of inspiration and hope, the power of collective action, and the possibilities of confronting the history of medical racism.

Though race correction has been removed from the official guidelines, the history of eGFR remains rooted in anti-Blackness — realities students are still not taught.

RACISM OUT

In Toronto, Black people experienced disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death. 4 Similar trends have been observed across time, geography, and respiratory conditions (e.g. asthma, pneumonia). These disparities are driven by structural factors including antiBlack racism. 5

• Incomenutrition, medications

• Housingindoor and outdoor air pollution, crowded housing, proximity to highways and factories, etc.

• Occupationexposure to pollutants/irritants/ pathogens, being a frontline “essential worker”

The Journaling Collective entered medical school during the early waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was also a time of “racial reckoning.” In May of that year, George Floyd was murdered by police officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis. Many institutions co-opted the Movement for Black Lives under the pretense of EDI. The Med School™ was no exception. While our class has the largest ever Black cohort, we have been taught that African Americans (read: all Black people) have 14.7% worse lung function than “Caucasians” (read: white people). This belief is treated as a scientific fact and applied to clinical algorithms in the form of “race correction.” Instead of questioning white supremacist assumptions, our curriculum uses race as a proxy for genetics. To that, we say:

• Chronic stress due to interpersonal and structural racism

• Access to testing and vaccinationsthere was a significant mismatch in the GTA between where these sites were initially placed versus communities that were most impacted by COVID-19

(1) Race is NOT biology

(2) Racial disparities in health outcomes are not driven primarily by genetics

(3) Whiteness is not the gold standard

(4) Blackness is not inferior

24

RACISM IN

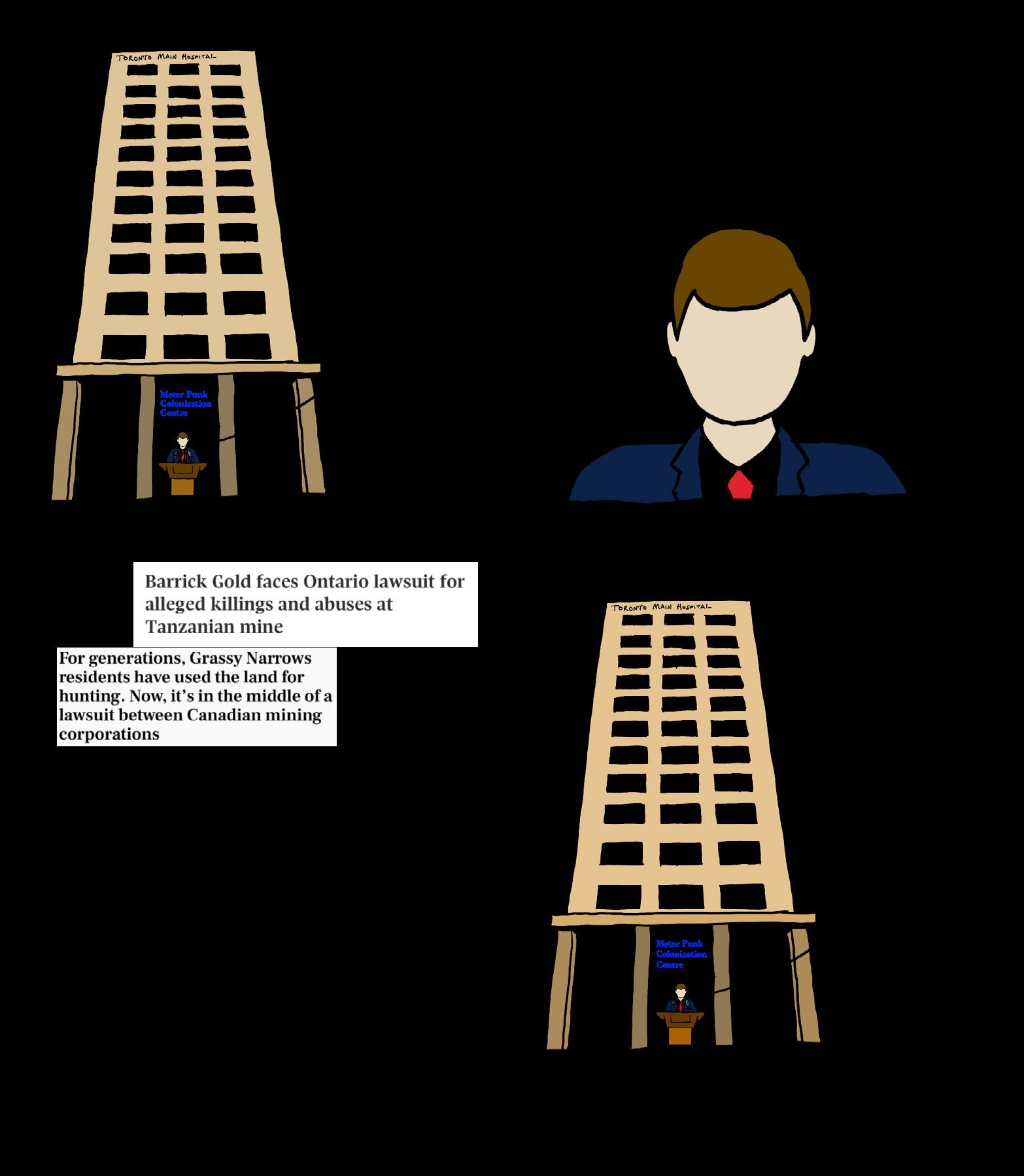

This image was adapted from a 2021 lecture from The Med School TM

bodies as inherently inferior, he justified slavery. Further research by the US Sanitary Commission reinforced racist interpretations of these differences by failing to account for the physical toll of brutal working and living conditions to which enslaved people were subjected. As eugenics took hold in the early 20th century, there was a rising interest in comparing lung function, and other physical attributes, across ethnoracial groups, always against a white diagnostic standard. The ghost of Cartwright continues to haunt medical education in the form of “race correction” seen in lung function calculations. This practice can result in the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of chronic lung disease in Black patients. 8

Spirometry is a test that measures lung function. Initial research attributed differences in lung capacity to height and occupation. By the time spirometry was brought to the US, assumptions of racial difference were central to this field of study . 6

Samuel Adolphus Cartwright (November 3, 1793 –May 2, 1863) was a slaveholding physician known for experimentation on enslaved Africans in the US. According to him, enslaved people who sought to liberate themselves from slavery were sick with “drapetomania.”

Cartwright claimed that Black people had 20% lower lung capacity as compared to white people. 7 By defining Black

25

RACISM OUT

Heard by trans and enby learners over the last 4 years:

“discoid rashes in lupus can be very disfiguring for women who get it”

tonic REM sleep can feature “erection in males”

seizures are often misdiagnosed as psychiatric illness, “for some reason in young women more than young men”

“people, women especially, describe blurry vision as though there is mascara smudged over the eye”

“for women” if you’re only doing vaginal and cervical swabs and not pharyngeal, you can miss many infections

“the husband” usually responds strongly to crowning

epilepsy has the same disease burden as “lung cancer in men or breast cancer in women”

LGBTQ people are sometimes considered an “invisible minority” because you cannot tell someone is queer as you might be able to do for something like “race or gender”

26 [sic]

"isitahimoraher?"

Patient: I have a question, it’s probably offensive

Me: Oh ok, go ahead

Patient: Are you a transsexual?

Me: Yes

androgen insensitivity: you are a “46XY male” who didn’t develop a uterus or penis

“it’s very hard to tell a lady who has hair growth not to use cosmetic things that get rid of the hair”

“unfortunately,

women do not make more eggs after birth”

alcoholic cerebellar degeneration: more common in “males”

27

Rest is Medicine

kim jae hee

content warning: this piece discusses suicide model minority

My parent’s meet-cute was in the 1980s. My father, a proud and shameless man, met my mother, a soft-spoken and thoughtful woman. Turmoil found both the country and my father’s family during this time; they’d eventually leave Korea for Canada. Their aspirations for North American stability were quickly severed when my father was laid off four times within a year. So my parents uprooted our family once again, this time away from our Korean community in Toronto to a small, rural horse-racing town with a population of 10,000. And to the benefit of me and my younger sister, my parents found success in running a three-forone business: a diner, video rental, and convenience store.

Our lives were immersed in the business. My parents worked 7 days a week, labouring to deliver the perfect eggs with bacon for their white patrons. When they were not working, their minds were consumed with ideas to improve their work. My father would surreptitiously “not steal” menus from bustling restaurants, then spend the evening pondering meticulously the pros and cons of various napkin options. Whether explicit or implicit, the messaging for me and my sister, as for many other children of immigrants, was that our work should consume us. If hard work is glorified as a virtue, then rest must be a weakness. We embodied the model minority (myth), recognizing that the West valued our diligent work and compliant demeanor in bolstering their empire, all the while harbouring disdain for our own existence.1 Over time, my parents began to perceive their own self-worth solely through the lens of capitalism, equating their wealth and labour as a measure of their value.

medical grind culture

I embraced a similar grind mindset, diligently working to be accepted to and throughout medical school. I had thought this was a calling, but by the time I faced the reality of medical training, it was already too late to walk away (read: I have a six figure line of credit to pay off now lol). From the outset, I was warned that clinical placements would push me to my mental and physical

28

limits. This was not a surprise to hear; in reality I aspired to bear the calluses and scars of hard work, akin to those of my parents. I accepted the work conditions because it was ‘for the benefit of our learning.’ The institution convinced me that compliance was in my best interest, to be submissive to authority and complicit in medical violence. I received praise when I sacrificed my sleep to labor through the night. I am not allowed to demand better, because if I did ‘my patients would suffer.’

This is not by choice, but rather because I am a cog in the wheel in a system reliant on our unpaid work for its survival. We enter medicine with allegiances to work for our communities, but the machinery of the medical industrial complex (MIC) works harder.2 Conscious of and oblivious to what I absorbed.

my mother and her brother

Born in 1963 to Suh Song-jook (서송죽) and Chae Young-geun (채영근), my mother is the eldest of three. Despite the unstable economy, my grandfather held a steady job as a crane operator, ensuring a reliable income for the family. My grandmother meticulously managed their finances, seeking the best interest rates by moving their money between banks and saving for special occasions, such as their monthly meat dinner. Like most of her generation, my mother was raised with the expectation to be a homemaker, sent to vocational college to learn needlework and cooking. She was smart, but her brother was the child to be sent to university.

I wonder if the destabilizing effects of living and working within this brutal system further fueled his struggles.

Her brother, my uncle, worked hard but struggled. Eventually he would relocate to Canada to work as a cook at my parent’s restaurant. Much of his life and passing remains enigmatic to me. I saw him as a solitary and headstrong person, harbouring deep affection for his sisters yet unable to forge close emotional bonds with them. The pressure to achieve material success clearly burdened him, as his final year was marked by conflicts around money. My mother now speaks sparingly of my uncle, and while it may be speculative, I wonder if the destabilizing effects of living and working within this brutal system further fueled his struggles.

The crushing weight of capitalism contributes to far too many suicides.

29

the individualization of rest and resilience

Close your eyes and take a deep breath, begin to notice how your body feels, scanning from head to toe. I scan my own body, as if I lack the resilience and must search for it from within. What would Audre Lorde have thought about medical education’s co-optation of her work. While attending another virtual, mandatory wellness session, I often pretend to close my eyes, looking down at my phone where I receive emails from the same faculty delivering this selfcare content. You are scheduled for one in four call shifts this month and are permitted to take three personal days off per year. Remember to submit an evaluation or you will be flagged for professionalism and by the way, where is your 500 word reflection on work-life balance.

Today, my father tells me little of his turbulent life and I find myself grasping for the glimpses he does share.

I am told to work 80 unpaid hours this week, by the same people asking me to make time to meditate, exercise, and rest. Oh, and I need to remember to call my pharmacy for a refill of my meds, I think my antidepressant™ is running low.

Hello, my name is J and I use she/her pronouns, what brings you in today? 15 minutes to run through the laundry list of today’s patient’s issues. They look exhausted – do my dark circles expose my own despair? In the ways that I have barely sustained myself through medical training, I have only been taught to maintain my patients’ health at a level where they are just well enough to work, but never truly well. They are not ready to go back to work. But they can’t afford another day off. ODSP is never enough (Ontario disability is $1300 per month). The role of the physician is inextricably linked to extracting monetary value from bodies who bear the impact of capitalism.3 We tell them the cause of their sickness is biological and divert their attention away from the genuine origins.

The more I work, the more I start to feel unwell. I believe it was my own doing, in not doing enough. They were not wrong to tell me to engage in self-care, but prioritizing quality time with family and friends, sleeping more than 6 hours a night, choosing rotations with less call, regular therapy – all were not enough. I think of my uncle now, wondering if he recognized the external circumstances contributing to his distress, and if he did, did this clarity alleviate any of his suffering?

30

my father

Son of Cho Ok-hee (조옥희) and Kim Kyo-jeung (김교증), my father was born in 1959 and grew up as the maknae (youngest) of five children. In the postKorean War era, south Korea was a place of political instability and corruption, defined by poor economic development and characterized as a puppet of the United States. As the nation was consumed by social upheaval, my father’s own father, with his “thin ears,” naively invested their family’s earnings in fruitless ventures. Although I still have never spoken to my father about this directly, somewhere along his timeline he contracts polio. To conceal his physical differences, he has avoided acknowledging this part of his story and continues to adapt his movement to avoid drawing attention to his disability. Today, my father tells me little of his turbulent life and I find myself grasping for the glimpses he does share.

Now in his 60s, he re-engages with the healthcare system once again. I accompany him to his elective cardiac catheterization. Still groggy, he mumbles on about how, like me, he had dreamed of being a physician. This surprises me as my aunts and uncles had always painted him as a shit disturber with little passion or motivation. He tells me how his teacher discouraged him from pursuing medicine, because “a physician cannot be in a body like yours.” And so he stopped engaging with his schoolwork because it wouldn’t matter anyway.

carceral logics in medical education

The university used my friends and me to showcase the consequences of nonconformity within our classroom. Disruptors and deviants with disabilities, Madness, obligation as caregivers, active involvement in community work. Unproductive because of the need to slow. Punished with academic probation.

Doctors are cops, so we surveil each other. Flagged for professionalism on an evaluation form, arbitrary yet inflexible standards. I failed a multiple choice exam testing me on my ability to memorize colonial medical violence. Does this make me a bad medical student? A bad future doctor?

The irony is that by the time we are staff, the system compensates us generously and tethers us to its existing structures.

Allegedly, many things have changed since my father’s youth, but so much remains the same.

31

disruption

We disrupt our education (see timeline on page 46), begging The Med School™ for the curriculum we dreamed of for future students. Our four year tenure inherently lacks longevity, and the school knows there is no structural accountability. We are siloed, unaware of the students who have come before us, and who likely fought the same battles.

The irony is that by the time we are staff, the system compensates us generously and tethers us to its existing structures. The anticipated class ascendance has already aligned us with the ruling elites. I will become a well-paid physician. Does this inherently entwine me with the maintenance of social and material capital? Are we honest when we say we would willingly give up our power, redistribute our resources? When offered class ascension, how can we maintain our commitment to being class traitors?

“rest is what we make possible through resistance”4

I struggle to make peace, simultaneously advocating to create space for myself and my classmates and yet my thoughts are consumed by the people in Palestine, Congo, Sudan. I am reminded that a significant portion of the global community are denied the right to rest. They often do not have the choice to rest and heal, it is eclipsed by survival. The relentless grind is neverending. “Resistance must be centered around dismantling the systems that rob us of choice, while building care networks to ensure equitable access to choice.”4

At the same time, I do believe that making space to pause and reflect is vital for our wider resistance efforts.5 As we move forward through residency, it will be crucial not only to imagine just futures but also to shoulder the responsibility of taking action and putting in the necessary work for our collective liberation. I watch my parents, now newly retired, learning for the first time how to truly rest and be well. I am compelled to find the same for myself and fight for the same for all.

32

Wellness Ableism in Medicine

See Part 2, page 41 for references

33

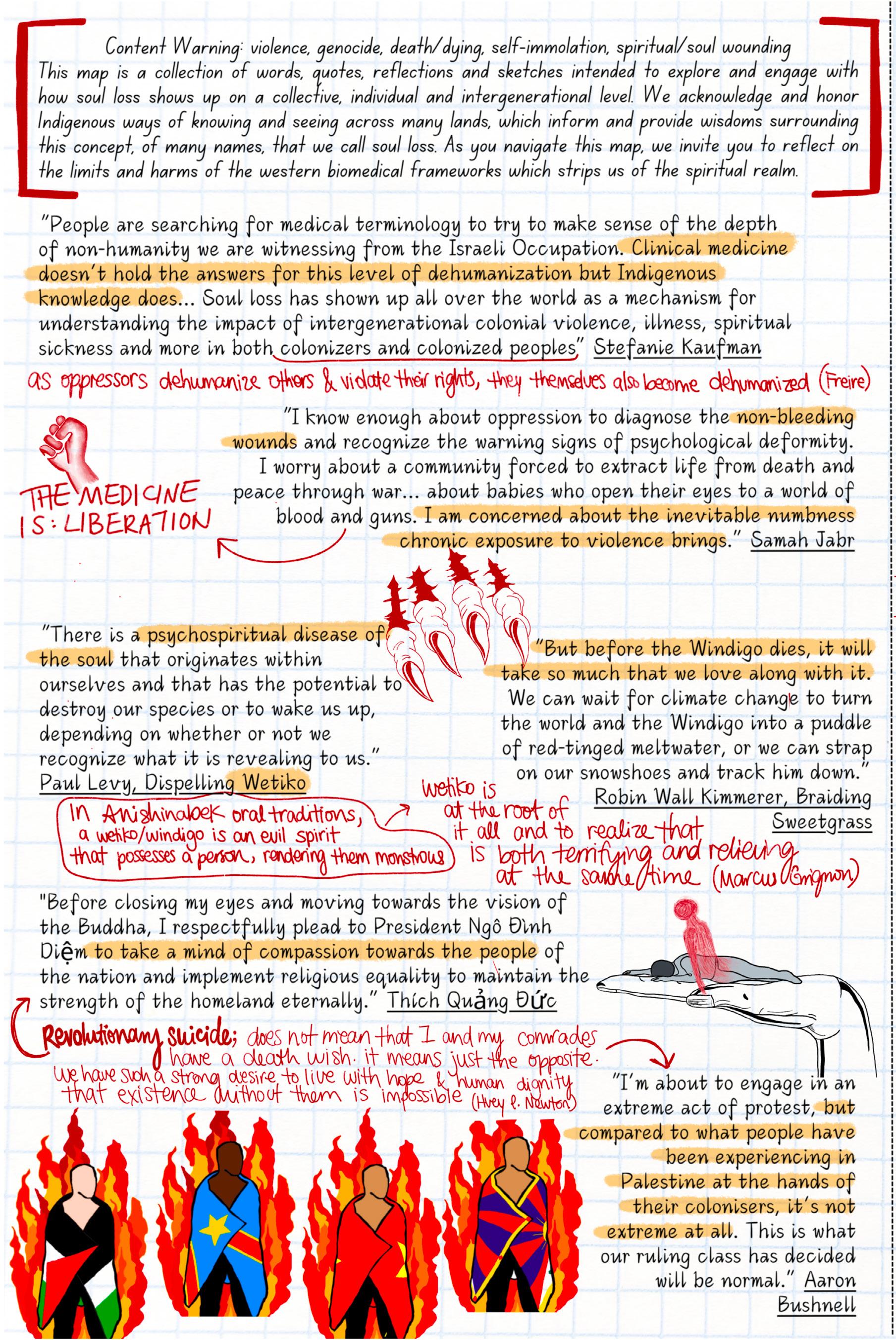

1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 8 9 9 10 7 ”

Collated and illustrated by: Sharumathy and Harsh

Lost in Foundations

lunan 芦楠

I sit in a seminar room of Toronto’s children’s hospital. Outside, grass rises amidst the spring breeze. Inside, our screen reads: ‘a 24-month female has concern of not speaking words. History and physical indicate no motor or cognitive delays. Investigation of audiology results insignificant. Diagnosis includes isolated language delay. Treatment includes daycare (if affordable). Referral to speech language pathology (if affordable). Follow-up to monitor for delays and learning disabilities.’

I play her story. I imagine the life she would live, her joys, her dreams. Would she be free to grow, to explore, to love? to belong

I play with words. I imagine medicine’s foundational blocks, history, physical, floating off the page. I discern “physical” split into species of blocks of see, hear, feel. I see all blocks orbit diagnosis. Disease (Pathology), Delays, Disabilities as center, as the Earth was once centered in our universe. amyth ofobjectivetruths. I see her story is written, her silence labeled, before her first word. Where are her dreams sown?

I play a distant childhood memory. “Bao 宝.” a thing loved. My mom’s gentle laughter flows. Love, warmth, presence, care. Love, despite my language development delays at 24 months, my struggles to say words, to exist. later, my distance, my explosive shame. Love, despite not hearing her sorrows. Love, that honed my first words, my first pen strokes. later, my literary essays of others’ stories. Howdidmydreamsblossom?

I play a cognitive shift inspired by bell hooks: “The word “love” is most often defined as a noun, yet … we would all love better if we used it as a verb.”1

I replay my story. My mom, once a rising pediatrician at Beijing children’s hospital, shifts diagnosis from a noun to a verb, from my disease to my concern. She shifted focus from my impaired brain, an object, towards my verbal delays, a subjective experience. She prescribed growth. treatments of a notebook and pencil to write with, colour-coded pens, agendas, coaching on my words, a quiet space. referrals to spaces where learning became pleasurable, hopeful. follow-ups of emotional wisdom. She centered love. I starred. Herlovedissolvedamythofobjectivetruth.

36

I replay her story. a lesson on love, lost in foundations.

I play with decentering disease, decentering myths of ‘objective truth,’ of doctors, of me. Disability was a diagnosis imposed by our medical school. An uncertain disease I did not have, until I trained in hospitals. An objective truth of being less than. A suffocating erasure.

I play history. Written Chinese is built of visual character blocks, 宝。 Early 20th century, young souls studied abroad, funded by colonialist policies, returned to our middle kingdom, and mapped our blocks onto the Latin alphabet. Pinyin. To survive our language’s erasure. later, to thrive. Our language flows in new ways. One Pinyin, Bao unifies, translates into several previously disparate characters. Bao hu 保护 means protect, baozheng 保证 means promise, support I received from later mentors. Bao zi 包子, the buns my dad cooked.

I play with translating objective truths from another colonial language, of medicine, of disabilities that erase me. Disability breaks into dis- , the latin roots for impair, and -ability , the latin roots of mind unifying with body. I translate dis- into the med school’s structural barriers that I challenge, -ability into my strengths, our strengths. To resist.

We play with models and equations. Our center shifts from Earth to Sun. From disease to our concerns. We thrive as suns. We star.

Is what we lost in foundations,* to translate, to love?

Love, as baoplay

*‘foundations’ is the namegiventothefirsttwoyearsofourcurriculumbyTheMedSchool TM

37

In Conversation: Fatphobia in the Clinic

Bev ewura-abena

Content warning: this peice contains conversation regarding medical violence and neglect towards fat patients

In medical school, we receive limited training on weight, nutrition and health. When fatness is talked about, it is pathologised; described solely in relation to sickness and death. This lack of nuance leads students to use fatphobic assumptions to frame their perspectives on weight and health. I spoke with Dr. Kelsey Ioannoni about her experiences and research on fatphobia within carceral medicine. Here are excerpts from our conversation.

On Policing the Body & Carceral Medicine…

I was only five when Dr. Small, my pediatrician, informed my mom that I needed to lose weight. With his white-man, white-coat authority, he stated this as a fact. I don’t remember exactly how I felt sitting there hearing Dr. Small appraise my small round body, but I remember that I didn’t like him…It would never dawn on me or my immigrant mother to question the validity of this proclamation coming from a white man in authority, and a medical doctor at that. — Dreaming Bigger: Body Liberation and Weight Inclusivity in

Health Care

by Sand C. Chang1

My interviewees would go to the doctor for whatever reason (almost never a weight loss reason)...The doctor would ask them things like, “Okay, what are you eating? What are you doing?” And either, if they provided answers that would have been the “correct answers,” they were disbelieved. Yes, you’re eating salad, but are you eating enough? What are you eating at night? What are you binging when no one’s looking? Yes, you’re going to the gym, but are you working hard enough? Versus if the patient then goes in and says, Yeah, well, I don’t really go to the gym. In that case, it’s still a negative conversation as well.

On the “So What?” Impacts of Fatphobia....

There is no fitness regimen that can keep you moving when doctors refuse to perform a joint surgery you need. There is no diet that can keep you alive when your doctor dismisses the constant pain or discomfort you’re begging them to acknowledge…The only escapes that fat people are offered from a micromanaging, soul-draining existence are weight loss or death.

— Dismantling Medical Fatphobia by Marquisele Mercedes, Pipe Wrench magazine2

38

It prevents access to care. People aren’t going to go to their doctor if all they’re going to hear is they need to lose weight. Or if their doctor told them to lose weight and then they come back and they didn’t lose the weight. Trust me, they are not going back. You feel like a failure.

Othering through Unbelonging …

Fat people are provided demonstrably subpar health care. We are constantly subjected to denigrating messages inside and outside the clinic. It’s an environmental exposure like pollution: the message that our bodies are incorrect, a plague, a contagion, is so ubiquitous in our interpersonal relationships, in media and advertising, and in the built environment that it might as well be in the air we breathe. — Self-fulfilling Prophecies by Monica Kriete3

My entire pregnancy I was terrified of being abnormal…There are subtle ways of reinforcing you don’t belong in healthcare spaces, so if you walk into your doctor’s office, and immediately you don’t fit in a seat in the waiting room… and perhaps they say your weight out loud as they write it down and then you sit in the office in the chair again, with no arms and a staff member comes in to take your blood pressure before the doctor comes, and they can’t do it because it doesn’t work. Before you’ve even seen the doctor you’re already… kicked down quite a few notches. How do you advocate for yourself?

39

On demanding more from medical institutions...

Most people — including many health care providers — are largely unconscious when it comes to calling out diet culture …as a product of white supremacy and colonialism. — Dreaming Bigger: Body Liberation and Weight

Inclusivity in Health Care by Sand

C. Chang1

Okay, I have a fat patient in front of me, they must lose weight. It will help their health. That can’t be the approach when most people are going to come in and say, Yeah, but the doctor before me told me that, too. The doctor, before that told me to lose weight, and guess what? I still haven’t lost the weight. Does that mean I don’t deserve healthcare? Does that mean I don’t deserve a discussion about why my blood pressure is high, or why I am having headaches all the time, or why my ankle’s twisted?

There is no difference between a) providers who are horrible to fat people because they openly hate us, b) providers who are horrible to fat people because they think it’s the best way to get us to lose weight, and c) providers who are horrible to fat people because they haven’t bothered to learn how not to be. There is no difference to the patient, or the outcome.

— Dismantling

Medical Fatphobia by Marquisele Mercedes2

On the burdens of self-advocacy...

Years from now, we will look back in horror at the counterproductive ways we addressed the obesity epidemic and the barbaric ways we treated fat people — long after we knew there was a better path.

— Everything You Know About Obesity is Wrong by Michael Hobbs4

Maybe I’m a little too close to this, because not a lot of people are pushing back...And even folks who are engaging in fat positive spaces don’t feel they can push back against that authority figure. Instead, I’ve heard what they will do is go to the doctors, and if they focus on weight loss instead of the reason I’m there, it’s a lot of in one ear out the other…or I might just sit and listen and then leave upset, or I might have to clear my day after I know I have an important healthcare appointment, because I know it’s not gonna go well, and I’m not gonna feel good after. There’s a lot less resistance

When I graduated, my fertility doctor, he said to me, “You know, Kelsey, you do a really good job advocating for yourself. Never stop,” he said. I shouldn’t have to advocate for myself.

40

happening in the healthcare space compared to the outside. There are strategies, for example, you could order cards that say I don’t want to be weighed that you can give to the staff, but then you think, Well, why do you not feel empowered to just say, I don’t want to be weighed at the start of my appointment? It’s because of all the shame that comes associated with that, or that you might have a negative interaction with the staff. Often, I will say, do you need my weight? If I’m getting a medication, you might need it for dosage. That makes sense to me. Is it because you’re just weighing me at the start of every appointment? Not so cool with that.

On the possibility of health spaces....

Imagine this: You schedule an appointment to go to the doctor for a routine exam. You have no anxiety about going because you know the doctor will not make assumptions about your health based on your appearance or body weight. In fact, they won’t even be interested in weighing you because they know this is a subpar way to make determinations about your health. Instead, they listen to you. They are more interested in what you have to say than the size or shape of your body. — Dreaming Bigger: Body Liberation and Weight

Inclusivity in Health Care by Sand

C. Chang1

It’s called the Obesity Pregnancy Clinic. That was the only time I ever felt like the language was stigmatizing, because after that she used my language. They weighed me, only to check my weight as I grew with a baby, but they never told me my weight. They always had the blood pressure cuffs [that] were set up for fat bodies. Because it was a pregnancy clinic for large women…I was surrounded by other fat people who were pregnant. And what a different experience that was! — what a fucking difference compared to other health care spaces! I don’t know why that can’t be replicated in so many other spaces, where you just recognize your patient as your patient and not as a body in need of fixing.

41

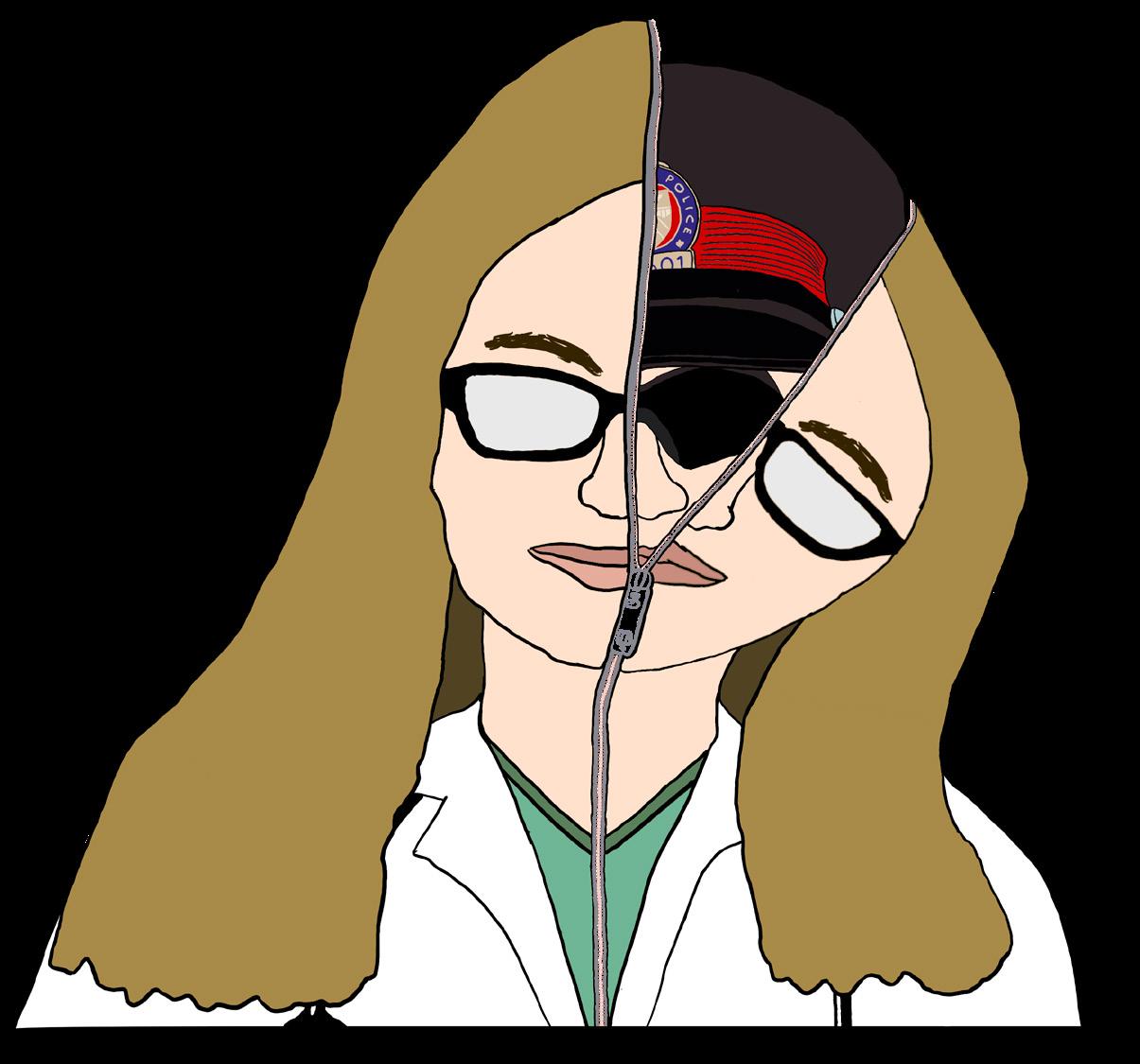

Social Justice Warrior

42

Content warning:

This is a satirical piece mimicking the format of a clinical report prepared by a health professional at the end of a hospital stay. The student is depicted as a patient. Content depicts forced hospitalization and medical violence.

DISCHARGE SUMMARY

Patient Demographics

Patient Name: Medical Student

Patient ID: Student no. 1005758861 Visit

Date of Admission: Sept 1, 2020

Date of Discharge: May 5, 2024

Discharge Diagnosis: Status post - 4 years medical school

Discharge Disposition: PGY1 (Post Graduate Year 1)

Diagnosis

Conditions Impacting The Med SchoolTM Stay:

• Preexisting: Commitment to Liberation, Anti-Imperialist Feminisms

• Developed During Stay: Burnout, Professionalism Infarct (NYHA class IV), Settler Colonialism Oppositional Disorder

Course While in The Med SchoolTM

ID: 28 yo F(emale) of ethnic race presenting with disillusionment and apathy. Patient uses they/them pronouns, however based on our judgement of her gender presentation, she/her pronouns were used for remainder of her stay.

Patient presents on Sept 1, 2020 with keen attitude and lack of medical knowledge. While in The Med SchoolTM from 2020-2022 she endorsed anhedonia, guilt, loss of physical and mental energy, and decreased psychomotor activity. Patient states this is secondary to cognitive dissonance, and witnessing overt racism, trans & homophobia. During clinical placements (2022-2024), patient displayed increasing amounts of persecutory delusions. They state that they are overworked by the medical industrial complex, despite the fact that we only make you work 80 hours a week. Prior to discharge, patient displayed increasingly aggressive signs of Settler Colonial Oppositional Disorder which threatened the safety of other staff and learners (for example: she posted “Free Palestine” on her private social media accounts, as more than 30,000 Palestinians have been killed.

43

Mental Status Exam on Discharge

Appearance: Disheveled, poor grooming. Multiple tattoos and facial piercings, inappropriate for a professional setting.

Motor: Psychomotor agitation and frequent fidgeting / shifting.

Speech: Rate and rhythm are within normal limits. Volume ranges from upper end of normal to loud. Tone is reactive.

Emotion: “ok”

Affect: Dysthymic, indifferent, dysphoric, angry, and labile.

Perception: Not reacting to external stimuli. Episodic depersonalization and derealization.

Thought Content: Delusions of persecution. Overvalued ideas of social justice. Visual hallucinations of a free, just world. Auditory hallucinations of a revolutionary future.

Thought Process: Circumstantial, can be momentarily goal directed with aggressive intervention by authority.

Investigations

• #Called2TheOffice1

• Mandatory meeting with the middle manager at an inflexible time during clinic duties

Interventions

• School sanctioned Office of Student Affairs counsellor*

• Learner mistreatment portal (where “we are not liable to take any action regarding reports”)

• Supportive listening:

• “We are worried about your mental health”

• “Have you tried Office of Student Affairs yet?”

• “Have you tried meditation?”

• “Have you tried exercise?”

• “Have you tried breathing?”

• “Our hearts are so heavy… for both sides, who are definitely equal military powers and there is absolutely no further context of occupation to be explored”

• Personal wellness day**

• Focused learning plan assignment

• Remediation

• Forced Leave of Absence

*only available once per month, wait time 1 month, 6x max total usage

**no more than 3 per year. Must be planned 30 business days in advance.

44

Medications:

• Antipsychotic medication for chemical restraint during stay

• Initiated on antidepressants prior to discharge Discharge Plan

In summary Med Student is 28 yo Female of ethnic race presenting with disillusionment and apathy. My impression is that she is suffering from Burnout. While she was once a keen and motivated medical student she sadly now presents as an empty vessel who needs to be educated on her mental health diagnoses so that she can learn to fit the mold. She spends too much time engaging in critical thought with her patients. If this continues she will never be able to make enough money. This is dangerous because her potential lack of class mobility may prevent her from enforcing class divisions in society. Discharge from The Med SchoolTM with medication.

Patient has completed remediation and received credit in all validated measurement tools for discharge. There are no acute safety concerns. Patient will come to her senses and start practicing medicine how we want her to when she recognizes how much debt she has accrued during her stay. Patient has been counselled on risks and benefits if she does choose to relapse. Based on our assessment, she was given adequate opportunity to ask questions which were answered to her satisfaction. Care will be transferred to toxic Residency ProgramTM as per match agreement.

Copies to be Sent to: Dean of Medicine, The Med School™ Director of Receiving Residency ProgramTM

We recognize medical students are at a reduced risk of forced institutionalization due to our privileges and social capital

45

Honouring our pulse of dissent, and moving to the beats of resistance. Flip over to the back of the zine.

Spring 2024. Copyright © 2024. The Journaling Collective.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used without written permission of the copyright owners.

Please scan this QR code to access a digital version of this anthology, including an audio version for those with visual accessibility needs.

ISBN: 978-1-7383996-0-4 (e-book)

Sowing Solidarities

Part 2: Beats of Resistance

by The Journaling Collective

Dedication

This is for all the Mad, psychiatric survivor, service user, disabled, crip, neurodivergent folks out there, particularly those with other beautiful identities and experiences that are marginalized by existing systems of domination. This is for our resistant communities, including Black, Indigenous, other racialized, queer/trans/gender non-conforming ones, who are subject to intersecting oppressions. This is for our people who are deliberately and strategically kept out of these rooms, silenced, and sedated. This is for the people we love who have been teaching us our fundamentals in health/care and the breadth and depth of the human experience far before entering medical school. Our communities continue to challenge and lead us to actively unlearn the harmful approaches taught to us in an often dehumanizing curriculum. This is a thank you to our communities, the people we love, who continue to keep us accountable through the gifts of their relationships with us.

We will not give up. We will not stop disrupting. We will not stop dissenting. We will not stop imagining and pushing for systems of care that center our humanity. We will not stop sowing and growing the seeds of care in the medicalized structures we are complicit in. We will not stop sowing solidarities outside of these structures.

4

Part 2: Beats of Resistance

Content Warning

Please be aware that some of the material in this anthology includes subject matter that may trigger some readers. Our decision to include such material is not taken lightly. These topics include: genocide; selfimmolation; forced hospitalization and medical violence, including within the psychiatric system; suicide; institutional and interpersonal violence rooted in anti-Blackness; settler colonialism; transphobia; ableism; fatphobia; and death and dying.

We have done our best to notify you of potentially triggering content at the beginning of specific pieces. We invite you to engage with these works in the ways that flow for you.

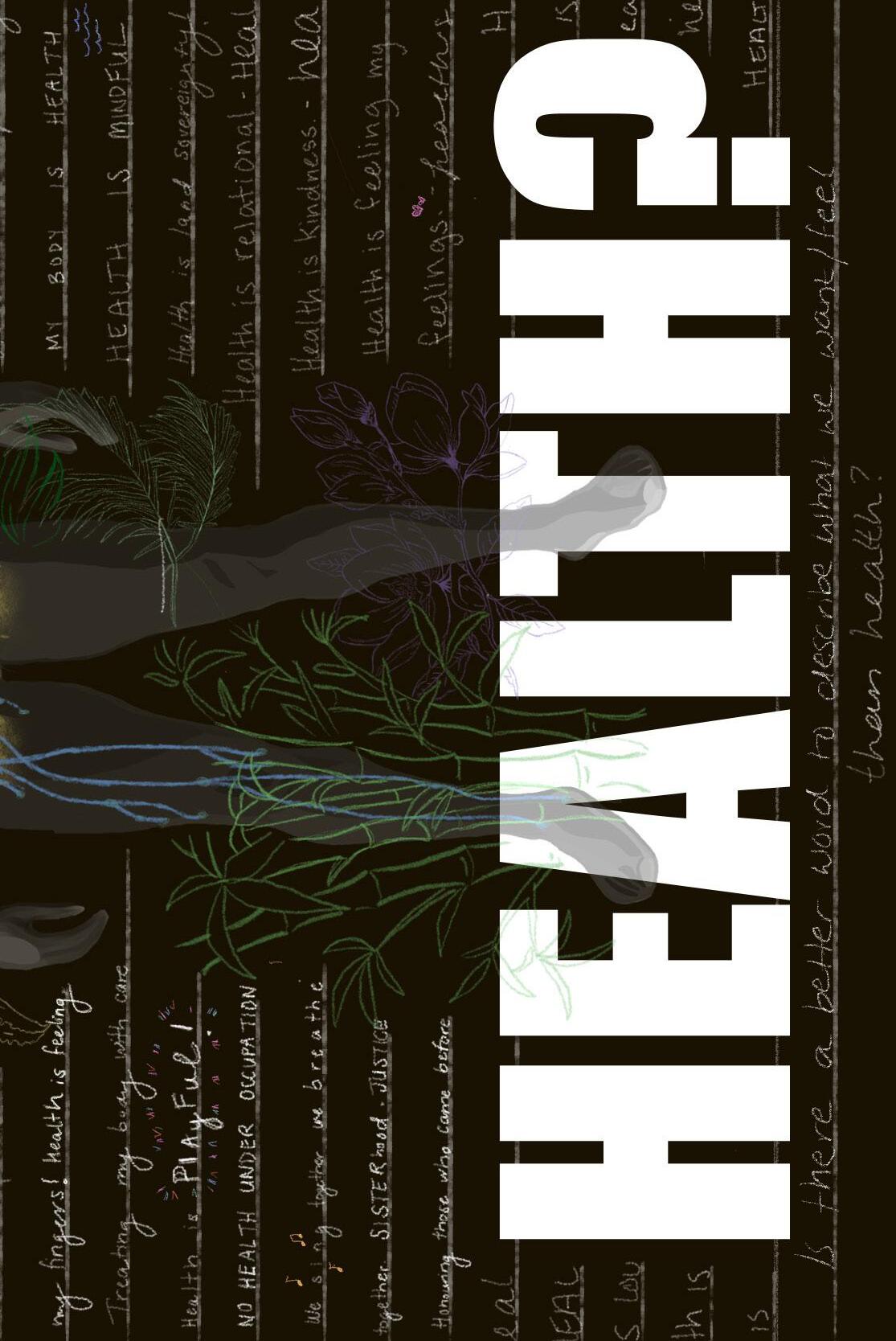

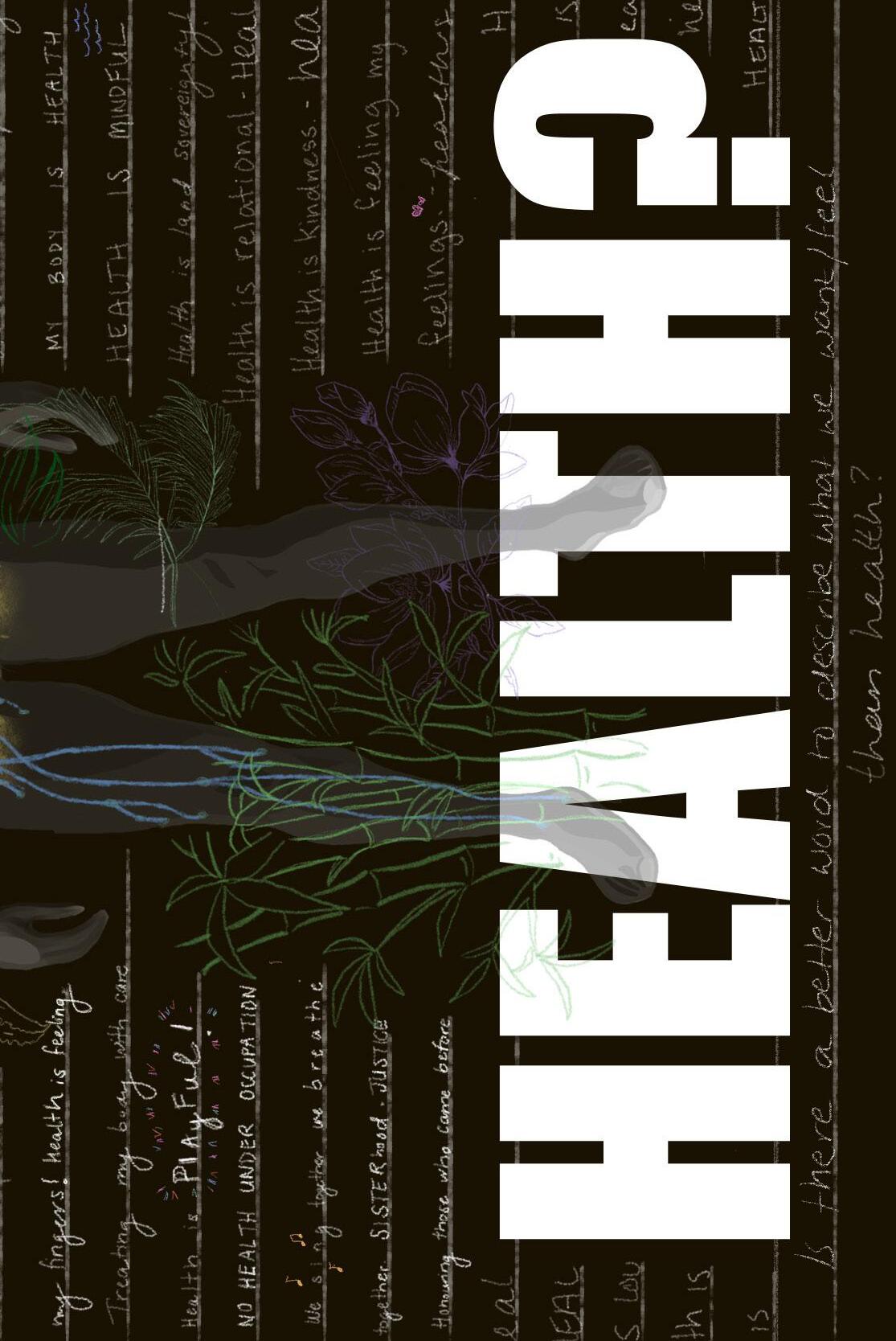

Contents 6 MD Offer Letter 10 What is health? 12 Building my Grief into Dreams 13 Invitations 14 Madness as Illness, Madness as Medicine 16 Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction Spotlight 17 Sudan Solidarity Collective Spotlight 18 Palestinian Youth Movement Spotlight 19 The Palestine Exception 20 Drug User Liberation Front Spotlight 21 Psychiatry for the people 27 Virtue Signalling while ‘Policing Black Lives’ 28 Ritualizing Death 30 Seeding Birth 32 Holding the Knife 34 how to make an invisibility cloak 36 From the River to the Sea 38 A thimble full of sorrow 40 Notes

Table of

Due to the sensitivity of the post, the author wished to publish the following piece anonymously.

Dear Student,

On behalf of the Admissions Committee, we are pleased to reward you an offer of admission to the Doctor of Medicine Program!

This year our Committee received over 5,000 applications, and extended less than 250 offers of admission. However, medicine is not a meritocracy. Upon meeting peers from diverse backgrounds, you will quickly realize that applicants differed in their advantages throughout the admissions process. “Not every applicant had the same access to opportunities to demonstrate or enhance his or her commendable qualities”. You will continue to benefit (and be disadvantaged) from the resources you have (not) accumulated over your lifetime as a result of your economic background, social position, postal code, (dis)ability, and other markers of identity. You will participate in a demanding (hidden) curriculum that expects you to pass the “would I have a drink with this person” test, even if you did not grow up in rooms like that, with people like that, or drinks like that. Furthermore, by accepting this offer, you will join a community where over 1 in 4 physicians experience burnout, and 34% meet the criteria for clinical depression. Here, you will connect with faculty members and clinicians that are equally burned out.

Upon accepting this offer of admission, we will send you information on the following:

1. The national and global footprint of our program. Our graduates and faculty are leaders in medicine, but despite some improvements in representation amongst the student body, our leadership suffers from a leaky pipeline. Women, BIPOC, 2SLGBTQ+, and people with disabilities are still less likely to be the faces you see on the walls of our historic institutions.

6

When we do introduce ‘diversity and inclusion’ mandates, ‘diverse’ peoples are still ‘included’ within the confines of oppressive institutions. In this way, ‘diversity and inclusion’ practice isolated from collective action against systems of power and oppression only serve to perpetuate cycles of marginalization.

2. Details on student societies and groups that represent diverse identities in medicine. Student groups are a source of solidarity for people that have endured injustices for far too long. However, historical legacies and ongoing effects of racism and colonialism are uncomfortable to discuss. Medical education is still largely ahistorical, despite some efforts to “infiltrate the curriculum”. For example, while learning nutritional science, you may not realize that one of the most celebrated paediatricians in Canada “administered colonial science” because they “view Aboriginal bodies as ‘experimental materials’ and residential schools and Aboriginal communities as kinds of ‘laboratories.’ Furthermore, curricula on ‘vulnerable populations’ (read: “people we oppress through policy choices and discourses of racial inferiority”) may ensure that you learn about risk factors, but it will often lack meaningful discussions on how our institutions have been, and continue to be, implicated in medical violence. Regardless, we will be sure to include a cultural competency lecture to ensure you understand how ‘Other’ people experience health, illness, and disease.

3. Wellness and resiliency training. We will continue to promote our novel wellness curricula that are being introduced to encourage resiliency amongst medical students. Here, we will talk about the benefits of mindfulness exercises, but we are still only starting to meaningfully discuss disability, mental health, and structural causes of burnout. In the meantime, you “must be able to tolerate the physical, emotional, and mental demands of the program and function effectively under Adaptability to changing environments and the ability to function in the face of uncertainties that are inherent in the care of patients are both necessary”. Demands of medical training that we deem to be inherent and integral to the care of patients include, but are not limited to: financial debt, up to 100 hour work weeks, racial discrimination, and toxic quizzing (i.e., ‘pimping’).

4. Information on the social determinants of health. As institutions with a social responsibility mandate, our curricula will introduce you to the social determinants of health. However, limited attention will be given to the structural determinants that make people sick.‘Vulnerable patients’ will often be considered to simply be in a state of poor health instead of human beings

7

who have been impoverished of their right to health. As a result, despite being framed as “a path to equity,” teaching the social determinants of health might actually be “a road to nowhere.” This gap in your education may lead to burnout because you are unprepared to treat marginalized patients and “send them back to the conditions that made them sick in the first place”. However, refer to Point (3) for more information on our innovative curricula to promote resilient medical students.

To respond to this offer you must:

1.Select “Choices/Offers” and then click on the “Offer” to accept the status quo.

2. Experience a serious case of cognitive dissonance as you join a profession with a social responsibility mandate.

3. Once you have indicated your response to the offer, please mentally prepare yourself to practice resiliency in response to systemic failures.

If you have done this successfully, you will receive a confirmation of losing your sense of self on the last screen.

4. However, if you are unsatisfied with the information presented above, you may choose an alternative path to medicine that re-centres social justice and equity in your education and clinical practice.

Should you choose to embark on this path towards health justice, you must consent to the following conditions:

1. I commit to learning and thinking about health that is liberated from systems of power, privilege and oppression.

2. I will use the power granted to me by lending support to communityled social justice movements.

3. I will ensure that my organizing and activism are a collective effort such that I step outside the confines and comforts of the medical institution that is implicated in the very violence I am striving to dismantle.

4. I acknowledge that liberatory praxis necessarily requires me to dismantle and uproot the very systems from which I may benefit.

5. I understand that I must be prepared to resist a lifetime of professional acculturation in pursuit of health justice.

8

6. I intend to seek out and connect with faculty members and clinicians who continue to challenge the status quo for mentorship and guidance.

7. I expect to be inspired by classmates who are also dedicated to reforming medicine.

8. I am committed to cultivating friendships, and forming networks of solidarity that will last a lifetime.

9. I will respect the intellectual and emotional labour required to create meaningful change, and will ensure that I am kind to myself and others who embark on this path of resistance.

10. I will continue to be hopeful.

In presenting you with two offers, one that adheres to tradition, and another that is revolutionary, you may choose how you intend to learn, think, and practice medicine. Always remember that many of you chose this profession to care for members of your community. We hope that you will take this offer as an opportunity to reflect on not only how you wish to learn medicine, but also how you wish to practice it.

Congratulations – we look forward to welcoming you this Fall!

*Originally published in CMAJ, reproduced with permission Anonymous. (2020). MD Offer Letter. CMAJ Blogs. Retrieved from https:// cmajblogs.com/md-offer-letter/

9

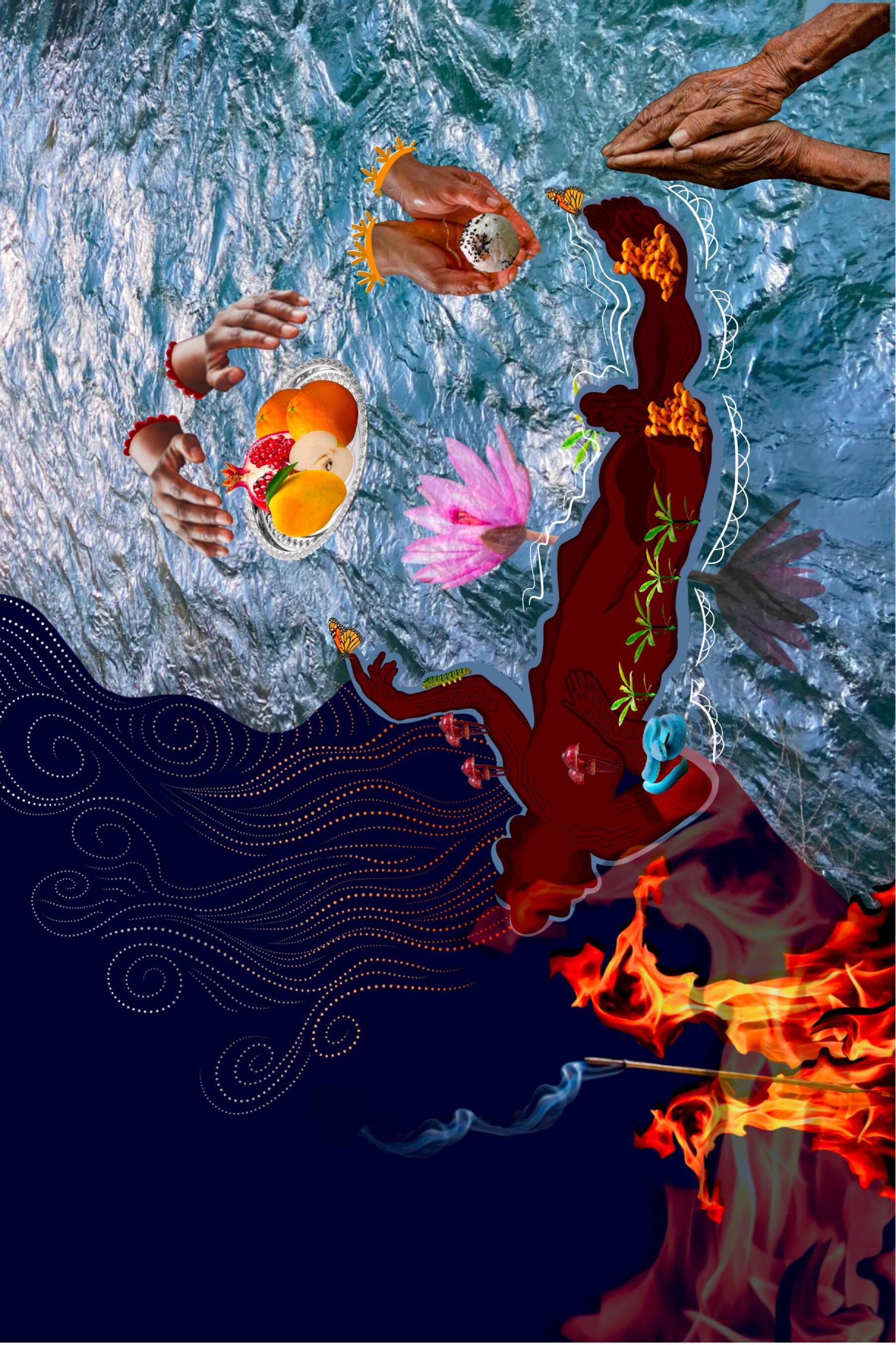

Building my Grief into Dreams

Kabisha V’pillai

I grieve.

I grieve for the people I have lost and continue losing to these systems.

Over and over and over again.

Over and over and over.

I grieve for the lifetime, for the mornings, for the nights, Especially.

I grieve for the joy, that was taken; I grieve for the joy, we could not make, together.

But I promised them.

I promised that I will not stop, my believing, that they are deserving, Of better.

Where we can hold them, and hand them, their pieces.

I dream of a place, where justice feels like the warm, cheeky caress Of a sun’s rays, And freedom, like a cool breeze on a summer’s day.

I dream of care, A care so deep, That the people I love, Become the people, we love.

12

Invitations

Amal Nura

I wish every one of us could be here, every leaf, every root. I would turn over the whole of the Earth to retrieve our lost and discarded siblings, and our plant parents.

I would wade through seas of plasma and iron.

I would destroy the whole world, pull it apart at the cracks beneath our bare feet.

What of all the unblossomed beings? Budding is a form of dying, an invitation to both pests and pesticides.

Colonizing aphids hot on our heels, sticky on our yellow leaves. A feast of honeydew, threads of mold.

But here we are offered a different kind of invitation–a seat, a portal. A warm expression on a brown face, something that unsticks, loosens knots, relaxes fists.

How is it that no one ever asked us? Or if they did, never in the right ways. All these buried memories could eat us alive. Perennial flowers bloom into aches, generations telescoping in space. We fall apart at the cracks, but it is there, too, that we rise.

to the clients and staff of a substance use & mental health program for Black youth

Dedicated

Madness as Illness, Madness as Medicine

Kumiko Lee Wong

Depression is symbiotic within my mind and body, Because I am perceived in a neo-liberal, cisheteronormative and white supremacist world.

A tax for feeling emotions so deeply and beautifully. I am told I get them from my mother.

My depression is a disability. (let’s not romanticize, it can really fucking suck)

She is the deep feeling of sadness, fatigue, indescribable feelings of “ick” within systems of power, muscle tension, headaches, insomnia, hypersomnia, garbage piling up, fridge empty, cereal for dinner again. She whispers to my relationships and sense of self.

Some of us rely on medications to feel like ourselves. And to not feel, when our selves are sought to be destroyed, amalgamated, erased.

My depression is a library. In times of survival, her heaviness has taught me, how to rest, how to have compassion for others, including myself setting boundaries around needs, bedtime is non-negotiable

When we are inevitably let down by systems, how to build care networks as dreamed by crips. Pod mapping,1 over snacks in the afternoon with my loved ones. Reciprocity swirls as the tide. Access intimacy2 is like a warm embrace

I navigate this world with disability and superability

14

Teachings from the Grassroots

Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction

Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction (TIHR) emerged in April 2020 during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in response to a massive shutdown of frontline services and a lack of basic needs for Indigenous people experiencing houselessness in the city of tkarón:to (Toronto).

As the nation-state of Canada continues to enact genocide against the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island, TIHR has been a force of resistance and collective care for their community.