Volume 2, Fall 2022

Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

Academic Year 2022-2023: Dr. Jane Elizabeth Dougherty (Founding Editor)

Courtney S. Simpkins Rhobie Underwood

Yoon Mi Sohn

Courtney S. Simpkins

Lyra Thomas

Katherine Woods

Cover Art by Emily Beadles, 2022.

Notes on Contributors iii

Affirmative Lovecraft Fandom: Beyond Disavowal and Apologism as Approaches to Lovecraft’s Racism

Martijn J. Loos . . . . . . . . . . 1

Betrayal and Redemption: A Comparative Analysis of Boromir’s and Edmund’s Character Arcs

S. Leigh Ann Cowan . . . . . . . . . 18

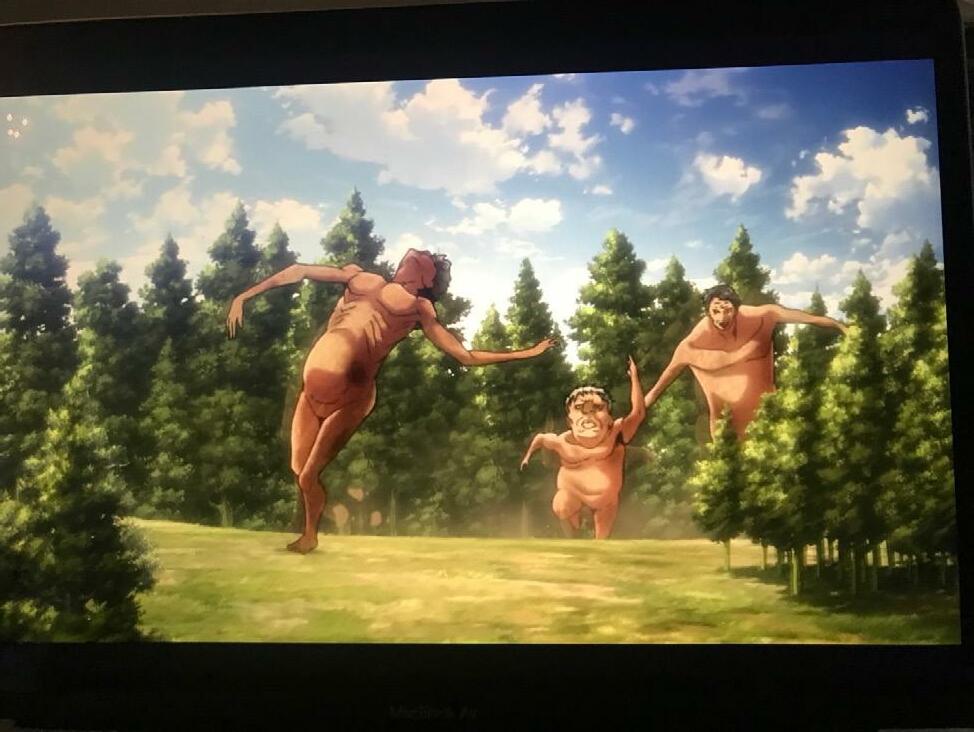

“Cursed Folk,” “Develes,” and the “Kynde of Gog Magog”: The Misuse of Medieval Antisemetic Imagery in Hajime Isayama’s Attack on Titan

Emma Baer-Simon . . . . . . . . . 29

The Philosophical Implications of The Orville’s Material Synthesizer

Ally Zlatar . . . . . . . . . . . 42

MARTIJN J. LOOS is a young academic based in Tilburg, the Netherlands. His work focuses on the intersections between speculative fiction and continental philosophy, with special interest in the works of H. P. Lovecraft and their afterlives. Loos lectures on literature and political philosophy at University College Tilburg, and spends his free time savoring experimental sci-fi and the local beer culture in equal measures.

S. LEIGH ANN COWAN currently works as an assistant acquisitions editor in the field of academic publishing and is an independent scholar. She holds two degrees in English Literature and Language (BA 2018 and MA 2020), a certificate in publishing (2019), and a degree in Deaf Studies (MA 2022). Deaf herself, Leigh Ann’s research interests lie mostly in representations of deafness in literature, but more broadly she looks critically at discourses of characterization in media. Her past and current projects include social justice work and advocacy for deaf students and literacy, focusing largely on fictional works featuring deaf characters on her blog, “Ranked: Deaf Characters in Fiction (Updated Monthly),” which is hosted on The Modcast—Accessibility, Literature, and Mustachios. Her previous publications include: “More or Less Hearing: Representations of Deafness in Marvel Comics,” International Journal of Comic Art, vol. 24 no. 1 (2022), “One and One-Half Friends: A Laingian Approach to Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia,” New Literaria, vol. 3 no. 2 (2022), and “A Proper Amount of Illness: A FeministMarxist Approach to Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-House,” Feminist Spaces, vol. 4 no. 1 (2021).

EMMA BAER-SIMON is a second year MA student, progressing on to the PhD in English Literature at Penn State University. Her primary area of research is in Middle English literature, with a focus on the rhetorics of antisemitism in medieval literature and culture, and its reception in the fantasy genre. She is currently doing work on allegorizing the Holocaust in fantasy and how it has worked with medievalism to contribute to Holocaust revisionism and antisemitism. She is an involved participant in fandom spaces, through the dissemination of both creative and educational fan-content that encourages Jewish resistance in the face of antisemitism, both from the canon material and in fandom responses. BaerSimon is currently working on fanfiction that attempts to rectify some of the antisemitic issues in Attack on Titan, as well as frequently engaging with the fan community online by making informational videos and creating accessible bibliographies. She hopes to continue encouraging awareness of antisemitism, and the role that medievalism has played in its prevalence, both within academia and in fantasy and fandom culture.

ALLY ZLATAR holds a BFA in Visual Art & Art History from Queen’s University & an MLitt in Curatorial Practice and Contemporary Art from the Glasgow School of Art. Her Doctorate of Creative Arts is with the University of Southern Queensland, and she is focusing on embodied experiences of eating disorders in contemporary art. Zlatar is a Lecturer at the University of Glasgow, teaching Arts Research Methodologies. She also has taught at KICL London and the University of Essex. Zlatar also is a leader in art-activism. She was the winner of The Princess Diana Legacy Award 2021, on the 50 Women ESG Leaders 2022 list, a Y20 Award Finalist for Diversity and Inclusion (Youth 20 by G20 Summit), and also received special recognition from The British Citizen Award 2022 for her humanitarian work.

The reception of H. P. Lovecraft’s (1890-1937) output, both fictional and non-fictional, has seen a remarkable trajectory. Not having been able to make a living from his writing, he died in poverty, his work regarded as pulp. Yet after his death his fame spread by way of the ‘Cthulhu Mythos’: the shared fictional universe of Lovecraft’s creation, to which other authors contribute to this day. The Mythos turned into a widespread fandom, and it meant the endurance of Lovecraft’s tropes, themes, fictional locales, and fictional entities. Lovecraft’s friend and collaborator August Derleth was instrumental in spreading the Mythos, both through his own work and by establishing Arkham House with Donald Wandrei in 1939, which was originally designed solely to conserve Lovecraft’s work as hardcovers. Arkham House publishes Mythos tales to this day, from pastiches to parodies.

The influence of fan activity in Lovecraft’s reception cannot be underestimated. Early literary criticism, emerging shortly after Lovecraft’s death, was mostly contained to amateur circles who were also confessed fans of Lovecraft’s work. This criticism included the likes of Fritz Leiber, George T. Wetzel, and Matthew H. Onderdonk, most of whom knew Lovecraft in life (Joshi, Dreamer 391). Through consistent fan effort, Lovecraft finally came to academic attention in the 1970s. The cultural fandom of Lovecraft was faster to develop. The Mythos was essential to this: practically any fan could write their own story within the larger universe. This practice continues to this day, centered around fan conventions like NecronomiCon, first held in 2013, and fan-based publishers of Mythos works, such as Arkham House and Crypt of Cthulhu.

Although it has been claimed that Lovecraft’s inclusion into the Library of America in 2005 meant he entered the American literary canon (Joshi, “Charles Baxter”; Sperling), not all is well in Lovecraft fandom. On the contrary, his reception is very polarized, a debate reflected in the fandom at large (Sederholm and Weinstock 25-33). What causes this polarized and contested, yet flourishing, reception of Lovecraft’s now-widespread legacy and inheritance? And what is at stake in discussing, interpreting, and contesting his work and life? Is there a need to add to the pile of opinions already formed on the matter? After all, “while serious fans and Lovecraft nerds still energetically debate his ‘real’ meaning, the media life of Cthulhu proceeds largely outside of their (or the author’s) control” (Lewis). I argue that two elements of Lovecraft’s legacy are largely responsible for his polarized fandom: the collaborative nature of the Cthulhu Mythos, and the racism and xenophobia underlying Lovecraft’s work. That last element has become increasingly important in popular and critical discussions of Lovecraft (Sederholm and Weinstock 25-8), yet the discussion is often sophistical and uncritical in nature. That is not to disregard other elements of his work that are influential and a rich ground for analysis and

interpretation—most notably Lovecraft’s philosophical underpinnings—but the Mythos and Lovecraft’s racism are two elements which constitute an intersection that, I maintain, needs additional critical attention.

These two elements and the recent upsurge in Lovecraft’s popularity inform each other: Lovecraft’s immense popular appeal and widespread fandom warrants a critical approach to his legacy of racism. If writing in the Mythos, and the reading and analysis of Lovecraft are “site[s] of disputes about history, politics, and affect,” where we “advance claims about how we should understand both texts and also the social world” (Claverie 81), then scholarship has a stake in Lovecraft’s reception if it wishes to expand its understanding of the world and advance candid critical interpretations of it. If fiction “can inform the civic imagination through vigorous discussions about fictional representations” (Saler 52), then scholarship must surely not lag behind in formulating an approach to such a contested fictional legacy as Lovecraft’s. Additionally, because racism is inherent in Lovecraft’s work (Gray; Baxter; Joshi, Magick 162; Paz 3-4), anyone in the fandom who writes in the Cthulhu Mythos—privately, published, or somewhere in between—will have to deal with Lovecraft’s awful side due to the collaborative nature of the Mythos. As such, these intersections raise questions on how to deal with “non-innocent, non-pure histories” (Schneider 162); with a literarily and philosophically influential legacy marred by racism, elitism, classism, and antisemitism. Any continued work in the Cthulhu Mythos or other strands of Lovecraft fandom will hence have to make conscious choices about how to deal the entirety of Lovecraft’s legacy, warts and all.

But that is not what happens. On the contrary, two approaches to Lovecraft’s legacy of racism dominate fandom.1 The first is what I call disavowal, in which the entirety of Lovecraft—the man, his fiction, his epistolary and essayistic output, and, sometimes, the fandom surrounding him, including the Mythos—are disavowed because of his racism. The second is apologism, in which Lovecraft’s racism is acknowledged, but softened or justified by a variety of tactics.

I maintain that both approaches are fundamentally flawed and are an obstacle for Lovecraft fandom to flourish in this day and age. I will first discuss Lovecraft’s racism, and how it is evident in his fiction. Following this is a discussion of first the disavowal, then the apologism approach, including an outline of the essential problems they lead to. Then I will consider the WFA trophy controversy of 2015 as a case study showcasing how both approaches function in practice, and how analyzing the controversy simultaneously highlights these approaches’ bankruptcy. But the WFA trophy also demonstrates an alternative way forward, an approach that affirms Lovecraft’s racism first, and then works from there.

This alternative approach is, perhaps unsurprisingly, fan-driven. Some writers in the Mythos, most of them self-proclaimed Lovecraft fans, started to write what has been dubbed “post-Lovecraftian” fiction (Phipps).2 These works are set in the Mythos, but they first acknowledge, and then subvert and deconstruct Lovecraft’s racism. Scholarship is lagging behind fandom in utilizing this approach,3 which is where I wish to make my intervention. By identifying and naming the most common yet bankrupt approaches to Lovecraft’s racism, I signal the need for an alternative approach. I maintain that fandom should look at post-Lovecraftian fiction—and not to disavowal or apologism—in its approach to Lovecraft’s literary legacy; this alternate way I call ‘affirmative’ in regard to Lovecraft’s racism. Only by embracing this approach can the fandom become sustainable and bridge the impasse caused by its current polarized status.

Lovecraft’s racism is well-documented, both in his fiction and in his personal communications and essays. Whether he also held misogynist (Baxter; Joshi, “Paula Guran”) and homophobic (Joshi, Magick 37) views, or not, is still debated. Lovecraft’s racial hatred was primarily directed towards black people. He argued for a strong color line until his death and railed against intermarriage between

black and white people, which would lead to “miscegenation” (Joshi, Dreamer 358). He claimed “racial mixture” would “lower the result” of a nation (Lovecraft, Selected Letters 1:17). Yet his racism was not limited to black people alone: he also abhorred Indigenous Australians, Irish, German, Polish, and Italian people; generally, anyone of non-WASP descent (Steiner 55). He backed this up with an appeal to scientific racism: “science shows the infinite superiority of the Teutonic Aryan over all others” (Selected Letters 1:17).

His racism extended to antisemitism. In a letter to Rheinhart Kleiner, Lovecraft recalls his first exposure to Jewish people when he went to high school in 1904: It was there that I formed my ineradicable aversion to the Semitic race. The Jews were brilliant in their classes—calculatingly & schemingly brilliant—but their ideals were sordid & their manners coarse. I became rather well known as an anti-Semitic before I had been at Hope Street many days. (Lovecraft, Letters to Kleiner 74-5)

Although Lovecraft spouted slogans such as “oppressive as it seems, the Jew must be muzzled” (Letters to Kleiner 19) in 1915, four years later he would meet his first Jewish friend, Samuel Loveman. He endorsed Loveman in the amateur journalism movement, noting how “Jew or not, I am rather proud to be his sponsor for the second advent of the Association. His poetical gifts are of the highest order, & I doubt if the amateur world can boast his superior” (119). He later also befriended the Jewish Robert Bloch and Kenneth Sterling. Yet most perplexing is perhaps his two-year marriage to Sonia Davis Greene in 1924, a Jewish businesswoman, a marriage to which I will return shortly.

This racism and antisemitism consequently led to some rather deplorable political associations. Lovecraft infamously called the Ku Klux Klan “that noble but much maligned band of Southerners” (Collected Essays 1:56), although later in life he repudiated the KKK (Joshi, Dreamer 98). A similar trend can be observed in his endorsement of Nazism: in a 1933 letter to J. Vernon Shea he stressed “a great & pressing need behind every one of the major planks of Hitlerism—racial-cultural continuity, conservative cultural ideals, & an escape from the absurdities to Versailles,” concluding “I know he [Hitler] is a clown, but by God, I like the boy!” (Selected Letters 4:257). As with the KKK, there is evidence his admiration for Hitler also dissipated later in life when Nazism’s excesses became better known (Joshi, Dreamer 359), but that does not mean that his views are any less reprehensible.

Leading Lovecraft scholar S. T. Joshi has ascribed this apparent ‘softening’ of Lovecraft’s xenophobic views to a shift in ideology (Magick 22, 162). Although the young Lovecraft saw biology as basis for his views, this later shifted to an ideology in which “it is culture rather than blood” that is the determinant (Joshi, Dreamer 361). This also explains his later Jewish friends, and marriage to Greene: he regarded them as well-assimilated, and hence culturally Aryan (221). Greene recalls in her memoir that “H.P. assured me that he was quite ‘cured’; that since I was so well assimilated into the American way of life and the American scene he felt sure our marriage would be a success” (Davis 26). Therefore, in Lovecraft’s eyes, Greene “no longer belonged to these mongrels” (368). Yet this belief was not consistently held, as evidenced by Lovecraft’s later begrudging respect for the Orthodox Jewish community in New York City:

Here exist assorted Jews in the absolutely unassimilated state, with their ancestral beards, skull-caps, and general costumes—which make them very pictureseque [sic], and not nearly so offensive as the strident, pushing Jews who affect clean shaves and American dress. (Lovecraft, Letters from NY 74)

Hence claims concerning the softening of his ideology should be met with caution, and neither should Lovecraft’s racism be oversimplified: it does appear that cultural, not biological, matters seem to preoccupy him most in the latter part of his life, but that does not necessarily lead to a consistent worldview which can be schematically laid out for critique. Furthermore, no matter to what degree

this softening of his views—a shift from ‘biological’ to ‘cultural’ racism or his racialized admiration for ‘unassimilation’ evidenced in his admiration for Orthodox Jewish people in NYC—were consistent and/ or true, they remain extremely noxious ideas. They all remain fundamentally racist ideas, revolving around an extremely bigoted racialized view of the world, and as such these potential nuances do not exculpate Lovecraft.

These views, including their gradual shift, found a way into Lovecraft’s fiction (Joshi, Dreamer 357; Paz 3-4; Baxter). The absolute bottom is his early (1912) poem “On the Creation of N-----s,”⁴ which showcases his biological racism by likening black people to “semi-humans,” created to “fill the gap” between man and animal (“On the Creation”). Herbert West—Reanimator (1922) describes its lone black character as “a loathsome, gorilla-like thing, with abnormally long arms which I could not help but call fore-legs” (44). “The Horror at Red Hook” (1927) describes New York City’s multicultural Red Hook neighborhood as “a maze of hybrid squalor,” from which “the blasphemies of a hundred dialects assail the sky.” (150-151). “He” (1926) is a lesser-known tale dealing with the same subject matter but written from the first person. The true horror in the ghost-written “Medusa’s Coil” (1939) is not the fact that the Medusa of the title, Marceline, has a “hateful crinky coil of serpent-hair,” but instead that “though in deceitfully sleight proportion, Marceline was a negress” (68). In Lovecraft’s fiction, having black ancestry is a worse offense than being a mythological monster. The also ghostwritten novella The Mound (1940) features a non-ironic scene of unabashed craniometry (237), showcasing Lovecraft’s belief that his racism was scientifically confirmed (Paz 3-6). The three robbers who meet a gruesome end at the hands of the eponymous “The Terrible Old Man” (1921) happen to be named Angelo Ricci, Joe Czanek, and Manuel Silva, thus representing Italian, Polish and Portuguese immigrants. These three nationalities, in turn, were the three leading minorities in Providence, Rhode Island, Lovecraft’s hometown (Joshi, Magick 77-8).

This blatant racism, both in Lovecraft’s personal life as in his fiction, warrants a considered approach if we wish to establish a healthy fandom and academic practice that does not perpetuate and reproduce said racist violence. The most commonly seen approaches—disavowal and apologism—have problems specific to them but share the common predicament that they dance around the issue at stake. Both do not deal with Lovecraft’s racism as it is; they refuse to affirm its existence as being there first and foremost. As a consequence, the issue is not dealt with at all, leading to various nefarious consequences.

When anti-racist and feminist thinking—or strands of fandom heavily influenced by them— encounter Lovecraft’s racism, an often-seen reaction is disavowal. That is, because of the non-innocent part of Lovecraft’s legacy, because of his racism, the entirety of his legacy is brusquely set aside. Disavowal refuses to engage with any part of Lovecraft, because of the parts that are tainted. I do not wish to argue that there is no merit in such a maneuver at all; the disavowal of xenophobia and bigotry is a necessary and laudable course of action.⁵ There is also no logical flaw in anti-racism being diametrically opposed to a man who espoused his virulent racism often and openly, both in his fiction and in his personal life. But not all is always as it seems, and I maintain Lovecraft fandom specifically cannot permit itself such unnuanced grand gestures if it wishes to have a sustainable future. At risk are critical finesse, in addition to leaving the playing field wide open to others.

The cultural blogosphere is particularly critical of Lovecraft because of his racist legacy, and as such it is the first place to analyze when discussing the disavowal approach. The central rhetoric is clear: “it’s too late to redeem Lovecraft” (Contreras). Lovecraft’s cross-medial influence is attested and immediately disavowed in calls to stop invoking the Mythos in video games (Greer). This commonly takes an activistic turn, exemplified by the petition against the continued use of Lovecraft’s likeness for the WFA trophy (Older), which I will return to later. It also often takes the form of calls to ‘cancel’ Lovecraft (Gault; Bal; Contreras; Coulombe), which is perhaps the most preeminent expression of the disavowal approach: Lovecraft’s literary legacy is built on racism, and hence the entire man must go.

Both non-scholarly and academic disavowal throw the baby out with the bathwater. In the former case there is nothing left to talk about, and in the latter case it is decidedly unacademic in its fervor. As mentioned above, this approach is uncritical and uncandid, two denominators a fandom surrounding a racist figure cannot permit itself. And although a complete disavowal of virulent xenophobia is laudable in itself, the critical silence that follows after leads to another problem: the (re)signification of Lovecraft’s legacy is left to other parties with less innocent agendas. Various apologisms can fill the void, including the man of his time defense, to which I will return in detail. Hence disavowal’s primary problem is that it itself is uncandid and uncritical; its secondary problem lays in what comes after.

Although an alternate approach to Lovecraft’s legacy can learn from the disavowal approach’s relentless opposition to racism, it can learn as much from disavowal’s flaws. The first is not to lose critical finesse by making gestures that are too grand, be they laudable or not. Secondly, it must not refuse to deal with matters, unsavory or not, lest they be dealt with by others in ways that are inimical to the greater task at hand: to critically and candidly grapple with a non-innocent racist legacy which is too pervasive and influential to ignore.

Like disavowal, the apologism approach first acknowledges that Lovecraft’s legacy has racist underpinnings. But the similarities end after that initial step: whereas disavowal wishes to do away with all of Lovecraft, apologism wishes to keep Lovecraft close. To be able to do so, his racism will have to be deflected or somehow explained away, which can take many forms.⁶ The most commonly occurring apologisms are: the ‘man of his time’ defense, comparisons to other authors with non-innocent legacies, and insisting on Lovecraft being a cultural—rather than biological—racist. I will shortly return to these different strategies in order.

These apologisms are most often seen in Lovecraft fandom and in what I call ‘classical’ Lovecraft scholarship.⁷ Since the WFA controversy, Lovecraft fandom has felt a larger need to defend its object from accusations of racism (Saler 52), because if the object of fandom is discredited, the fandom itself can be perceived as being unjustified. What these two groups of proponents—fandom and scholars—appear to share is a feeling of being under attack, because a bad Lovecraft would reflect badly on them. If Lovecraft were to be condemned as a racist and antisemite, it could seem logical for third parties to assume that his fans and scholars share these prejudices (Walter). To prevent that, an attempt at apologizing for Lovecraft is mobilized, because a successful apology would justify Lovecraft as an object for both fandom and scholarly interest.

The prime apologism is what weird fiction scholar Ezra Claverie dubs the “man of his time defense” (8). It is unassuming in its main proposition: ‘yes, Lovecraft was a racist, but everyone was back then.’ This reasoning is used over the board, from academic criticism (Newitz 97; Lovett-Graff 175; Joshi, Magick 41-3) to fandom (Stevenson “Keep the beloved”; Claverie 86-9), and keeps returning in classical Lovecraft scholarship (De Camp 275; Joshi, Dreamer 358-60). Yet, as mentioned before, this is historically incorrect: although it is true that Lovecraft grew up in a time dubbed “the nadir of American race relations” (Logan xxi), he went above and beyond what was considered normal for the time. Hence the man of his time defense either sketches a false image of Lovecraft’s convictions or claims that the average American ‘of his time’ was virulently racist. Both are wrong. As for the former, Lovecraft himself was keenly aware of the fact that his views were not average, noting in a 1924 letter to his aunt Lillian Clark not to “fancy that my nervous reaction against alien N.Y. types takes the form of conversation likely to offend any individual. One knows when and where to discuss questions with a social or ethnic cast” (qtd. in De Camp 256). As for the latter, one can hardly state that the average American regarded—for example—New York City’s Chinatown as “a bastard mess of stewing mongrel flesh without intellect,” hoping that “a kindly gust of cyanogen could asphyxiate the whole gigantic abortion” (Lovecraft, Selected Letters 1:181).

A slightly more nuanced, but likewise false, variation on the man of his time defense is the assertion that it was specifically Lovecraft’s family and social surroundings that were virulently racist (Joshi, “Racism and Recognition” 24). Lovecraft was brought up in an affluent New England WASP family, and the apologism states that therefore Lovecraft simply couldn’t help his racism. Historical evidence for this is likewise scant, and there are no surviving sources of Lovecraft’s family being exuberantly xenophobic (Steiner 54-5). It also seems to disregard Lovecraft’s extensive traveling across the eastern United States and Canada, and his time living in multicultural New York City from 1924 to 1926. In fact, man of his time reasoning disregards and trivializes the anti-racist movements of the time, including the writings of Lovecraft’s friend and correspondent James F. Morton (1870–1941), who actively advocated for racial equality. It also erases Lovecraft himself, as if he had no choice in his racism, which makes the defense all the more ironic when it is used in tandem with the earlier discussed claim that later in life Lovecraft ‘softened’ his xenophobic views. Hence the man of his time defense amounts to an attempt at revising the past, which has consequences ranging from the undesirable to the disastrous.

Comparing Lovecraft’s non-innocent legacy to those of other authors who were also shown to hold noxious views is a rather blatant deflection which refuses to deal with the issue at hand. Joshi, a consummate apologist, provides a good example: he singles out Bram Stoker (“Once More”), Raymond Chandler (“Reply to Baxter”), Edgar Allen Poe, H. G. Wells, Jack London, Robert E. Howard, Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and George Orwell as authors who are “given a pass for their deviations of current sociopolitical orthodoxy” (“Racism and Recognition” 27). That is, the apologism goes, Lovecraft is singled out for his various -isms, whereas many others are not. This deflection implicitly overlaps with the man of his time defense, and its primary faults are the same. It attempts a revision of the past and does nothing to address the issue at stake: Lovecraft was a virulent racist. It also oversimplifies a hugely complicated matter on multiple levels: it not only flattens the mentioned authors’ viewpoints into a single assertion on their racism, but it also claims that contemporary discourse does not engage with their non-innocent legacies. Both are false.

I briefly treated apologizing Lovecraft’s racism on the grounds that he was a cultural rather than biological racist earlier. It mostly shows up in scholarship (Joshi, Magick 22, 162; Steiner 54) and alt-right discourse which uses this defense to justify their own calls for establishing a white ethnostate (Bimmler; Pechorin). It claims that Lovecraft’s racism shifted from being race-based to it being allegedly culturebased. I can be short on its faults: speaking from ‘within’ the defense, whether it is biological or cultural, racism is still deplorable and hence this defense does nothing to address the issue at stake. Addressing the defense from ‘outside’ of the argument, an easy separation between biological and cultural racism cannot easily be made (Saler 52), and hence the defense rests on a shaky foundation.

All forms of apologism share a haste to do away with Lovecraft’s racism so as to get faster to ‘the things that really matter’; be they Lovecraft’s fiction, his philosophical thought, or his life. This is exactly where the apologism approach’s biggest flaw resides: by focusing on an alleged more important thing behind the racism, the actual racism itself is not dealt with, and remains an open wound. From this impasse other problems arise—the wound is left to fester—as apologism then opens the way for revision of the past and a lack of criticality. As such, apologism’s commendable initial step—acknowledging Lovecraft’s racism—feels empty in retrospect: the racism is swept under the rug or otherwise deflected, with all the problems that brings.

The man of his time defense opens the door for those with more nefarious agendas than the average apologist. Claverie has shown how “the man of his time” defense has become a bulwark for subsuming and justifying white nationalist talking points via Lovecraft’s works and legacy (92). In this capacity, a white nationalist “secondary fandom” (80) of Lovecraft takes Lovecraft’s legacy of racism not as something to be disavowed or apologized; but takes it as the main attraction to Lovecraft. Much of it takes

place on website comment sections, niche magazines such as Instauration (Claverie 93-4), discussion/ imageboards such as 4chan and Stormfront (“most red pilled”; Bimmler), alt-right meme culture (see fig. 1), Facebook comments (Claverie 86-7), and white nationalist ‘race realist’ blogs (Pechorin; “Cosmic Horror”). Lovecraft’s inclusion in the recommended reading list of the American National Socialist White People Party, which claims that “Lovecraft was one of us, all right!” (Covington) is emblematic of this. By presenting Lovecraft as typical for his time, white nationalists can advance an image of the past in which racism was the norm, which means that contemporary anti-racist discourse is “an unjust and oppressive departure from the norms of an idyllic racist past” (Claverie 92).

This revision of the past opens the way to speculating on and advancing white nationalist claims in the present: “reactionary and White Nationalist fans [of Lovecraft] have a stake in (mis) remembering American history and re-narrating it to make White supremacy a normative, unstigmatized position, because if it was so in the past, it could be so again.” (101). This means that Lovecraft has been enthusiastically embraced by some white nationalists as a herald of their views and convenient disseminator of their agenda:

Lovecraft’s ever increasing [sic] influence in the artistic community, coupled with the eloquence and logic with which he is able to articulate positions that the PC world may find distasteful, make him, in my opinion, an ideal instrument for disseminating WN ideas. (Bimmler)

The capability of the man of his time defense to advance white nationalist agenda unquestionably demonstrates its bankruptcy. The fact that Lovecraft has been adopted in some white nationalist circles emphatically demonstrates the need for an alternate way of grappling with his racism, a way that does not lend itself to revision of the past.

The disavowal approach is also not innocent. By disavowing all of Lovecraft, the playing field is left wide open for others to resignify his legacy. Novelist Silvia Morena-Garcia explains the reaction of people of color when asked to contribute to her Lovecraftian anthology She Walks in Shadows (2015): “some people of color would tell me no, no, Lovecraft was racist, so I can’t write that” (“Writers of Color”). Although laudable in its gesture, it disregards the fact that someone else will “write that,” and 4chan’s /pol/ board shows what form that writing might take (see fig. 1).

These approaches to Lovecraft’s legacy share a common predicament: the real sore point, the issue at stake, Lovecraft’s blatant racism, is not dealt with. Disavowal and apologism dance around the issue in various ways and for various reasons. Yet their result is the same: it opens the door to malicious resignification, such as revision of the past, denying the existence of Lovecraft’s racism, or replacing simplifications with other simplifications. The way forward is then an approach that affirms the issue at stake, no matter how horrible, and from there resignifies Lovecraft’s legacy. We can look at the WFA trophy controversy to see these matters at work.

Fig. 1. Alt-right Lovecraft meme, posted on 4chan, /pol/ board, 1 February 2015.

Note: JFFC editors opted to censor the offensive word in question.

Consider the controversy surrounding the World Fantasy Award trophy in 2015, a watershed moment in Lovecraftiana. Its significance is due to two main reasons: first, it dragged the debate on

Lovecraft’s racism from limited discussions in scholarship into the online limelight; and second, it foreshadowed—and perhaps, partly caused—the first wave of post-Lovecraftian Mythos fiction (Saler 52). From the award’s inception in 1975 through 2015, its trophy was a caricature of Lovecraft by artist Gahan Wilson, nicknamed ‘The Howard’ (see fig. 2). Presaging the controversy were writer Nnedi Okorafor’s musings on being awarded with the bust of a racist man in 2011 for her novel Who Fears Death (2010). She asked on Facebook (“A friend of mine”) and her blog (“Lovecraft’s racism”) what to do with her prize after a friend of hers had shown her Lovecraft’s “On the Creation of N-----s,” making her aware of Lovecraft’s non-innocent legacy:

Anyway, a statuette of this racist man’s head is in my home. A statuette of this racist man’s head is one of my greatest honors as a writer. A statuette of this racist man’s head sits beside my Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa and my Carl Brandon Society Parallax Award (an award given to the best speculative fiction by a person of color). I’m conflicted. (Okorafor, “Lovecraft’s racism”)

Several other writers, including Jeff Vandermeer, Chris Barnes (Okorafor, “A friend of mine”), and China Miéville (Okorafor, “Lovecraft’s racism”) weighed in, and the discussion started rolling.

Three years later, when writer Daniel José Older started a petition in 2014 to change the Howard to a bust of Octavia E. Butler, the controversy really picked up steam. Older’s accompanying statements rubbed many the wrong way: “Many writers have spoken out about their discomfort with winning an award that lauds someone with such hideous opinions, most notably Nnedi Okorafor. It’s time to stop co-signing his bigotry and move sci-fi/fantasy out of the past” (“WFA Statue”). One ‘Steven Stevenson’ launched a counter-petition, claiming the push against Lovecraft’s likeness for the WFA was only “to be PC” (“Keep the beloved”). Editors of Tor.com—a bastion for sci-fi, fantasy, and weird fiction publishing— started weighing in (Schelbach), and the media hopped on the controversy train, too (Maroney; Flood).

The WFA decided to change its trophy from the Howard to a tree in front of a moon in 2015 (Cruz). This led to a reaction by none other than imminent Lovecraft scholar S. T. Joshi,⁸ who called it “craven yielding to the worst sort of political correctness and an explicit acceptance of the crude, ignorant, and tendentious slanders against Lovecraft propagated by a small but noisy band of agitators,” and handed in his own two World Fantasy Awards (Joshi, “The World Fantasy Award”). He weighed in twice more on the matter (“Crusades”; “Once More”), rebuking the WFA’s decision with arguments ranging from pointing out other writers with awards named after them being racists too (“Crusades”), to an elaborate man of his time defense (“Once More”).

Note how Joshi’s arguments are apologetic, using two of the apologist strategies I discussed before. He deflects the actual issue at stake: the WFA trophy was, without a doubt, a bust of a virulently racist man (Flood). However, the ‘other camp,’ exemplified by Daniel José Older, takes the disavowal approach to Lovecraft’s legacy: there is no engagement with the issue at stake at all, only an uncritical complete disavowal of the entirety of Lovecraft because of a contentious issue, employing a simplified understanding of Lovecraft’s racism. As such, the responses to the WFA controversy did not further the argument, nor did they lead to any sort of critical, affirmative way of dealing with Lovecraft. Instead, the WFA changed the bust (see fig. 2) without an accompanying statement—itself a form of dancing around the issue by not addressing it at all—only expanding the rift between both camps. As such, the WFA controversy can be seen as symptomatic of the impasse in Lovecraft fandom, and as demonstrating the bankruptcy of the two most commonly seen approaches to Lovecraft’s legacy of racism.

As noted at the start of this small case study, not everything was bad about the controversy, however. Going back to 2011, before the discussion was well underway, Okorafor’s tentative conclusion on her feelings regarding the bust are extremely insightful contra the contentious discussion that would follow three years later:

Do I want “The Howard” (the nickname for the World Fantasy Award statuette. Lovecraft’s full name is “Howard Phillips Lovecraft”) replaced with the head of some other great writer? Maybe. Maybe it’s about that time. Maybe not. What I know I want is to face the history of this leg of literature rather than put it aside or bury it. If this is how some of the great minds of speculative fiction felt, then let’s deal with that... as opposed to never mention it or explain it away. If Lovecraft’s likeness and name are to be used in connection to the World Fantasy Award, I think there should be some discourse about what it means to honor a talented racist. (“Lovecraft’s Racism”)

Okorafor expresses a desire for affirmation: facing the issue at stake as it is, and then dealing with it from there. This is starkly opposed to disavowal (she does not want to “never mention it”), or apologism (neither does she want to “explain it away”). Instead, she wishes to “face” Lovecraft’s legacy of racism.

The WFA controversy was a microcosm showcasing the issue at stake: contemporary Lovecraft scholars and critics cannot properly deal with Lovecraft’s legacy, whereas fiction writers—writing in the Mythos being an integral, but specific, part of Lovecraft fandom—have been exploring a possible alternate way ahead. The apologism approach to Lovecraft’s racism was illustrated by Joshi and the like, the disavowal approach by Older. Okorafor expresses the need for an alternate approach: an affirmative one. As such, the WFA trophy controversy was a turning point in Lovecraftiana: historian Michael Saler notes how it “stimulated an efflorescence of new Mythos fictions reflecting these debates” (54). That is, it stimulated post-Lovecraftian fiction, Mythos tales that take an affirmative approach to Lovecraft’s noninnocent legacy.

An affirmative approach to Lovecraft’s legacy of racism can help both Lovecraft fandom and scholarship navigate beyond the current impasse created by the disavowal and apologism approaches. I borrow the term ‘affirmation’ from the postcritical humanities (Braidotti). It entails a critical gesture that “first and foremost, insists that this is what was said or written” (Knittel 175), as opposed to claiming there is something else ‘behind’ the object of attention. In the context of Lovecraft’s racism, it means that the first critical step, be it in fandom or scholarship, should be the affirmation of that racism: a

foundational gesture that insists on acknowledging Lovecraft’s racism first and only after that considers interpretation, discussion, and explication.

Using this gesture as an approach to Lovecraft’s racism can borrow the strengths of other approaches yet avoid their pitfalls. One can still radically say ‘no’—like disavowal does—after the initial affirmation of a racist legacy. The difference with disavowal that affirmation happens “in such a way that this ‘no’ keeps us concerned and related to what we refuse” (Thiele 28). This remains a critical gesture, as opposed to wholesale disavowal. Affirmation is akin to apologism in that it acknowledges Lovecraft’s racism, but the key difference lays in that affirmation insists on the bare fact: Lovecraft’s racism as it is Apologism’s revision of the past is enabled by the fluidity it allows towards the bare fact—for example, ‘his racism wasn’t that bad for his time!’—and I have shown what consequences that can have. So contrary to both disavowal and apologism, affirmation can enable “undergoing transformations in such a way as to be able to sustain them and make them work towards growth” (Braidotti 57). That is, by affirming Lovecraft’s racism first and foremost, fandom can then move on to find new and better ways to engage with Lovecraft’s legacy candidly and critically. Turning to post-Lovecraftian fiction can show us how.

Elizabeth Bear’s Shoggoths in Bloom (2008) takes a black professor, Paul Harding, as its protagonist. He faces prejudice in 1930s Maine: “Doctor Harding? Well, huh. Never met a colored professor before” (Bear 180). As reports of the Kristallnacht appear in the newspapers, Harding forms two unlikely bonds. First, over and across barriers of race, Harding befriends a local fisherman named Burt; second, Harding manages to communicate with a shoggoth, a Lovecraftian monster central to Lovecraft’s “At the Mountains of Madness” (1936). At this point in the story, the shoggoth reveals its history as having been created as part of an artificial slave race—created as labor and as weapon—tying Bear’s shoggoth to Lovecraft’s depiction of the Mythos creature. Harding contemplates using the immensely powerful, yet easily controllable, shoggoths to end the stirring war in Europe before it has even started, but ultimately decides against it. As such, Bear connects the titular shoggoths—slaves in Lovecraft’s original—to Harding’s experiences as a black man. By navigating these complex, entangled histories of racism, Bear affirms Lovecraft’s racism yet shows how we can move beyond, without apologizing for or disavowing it.

Ruthanna Emrys’ The Litany of Earth (2014) subverts Lovecraft’s “The Shadow over Innsmouth” (1936) by telling the story from the perspective of a female Deep One, a monstrous antagonist who is a thin stand-in for the racialized other in Lovecraft’s original (Pillsworth and Emrys, “Finding the Other Within”). Emrys’ protagonist, Aphra Marsh, faces the bigotry against Deep Ones evident in “The Shadow over Innsmouth.” Yet this time, we are exposed to the monsters’ inner world and realize the violence at the heart of the issue. Emrys, who comes from a family of Reform Jews and is in a same-sex marriage, notes how her “sympathy was squarely with the interned frog-monsters [the Deep Ones in “The Shadow over Innsmouth”],” because Emrys saw parallels between how they were depicted and negative depictions of Jewish people. As such, The Litany of the Earth was born, which takes the fundamentally affirmative angle of “cosmic horror written from the position of oppression, rather than privilege” (Pillsworth and Emrys, “Taking a Baseball Bat”).

Both works, emblematic of post-Lovecraftian fiction, are the works of fans. Bear examines her own complicated relationship to Lovecraft: “How is it, then, that there’s still so much to admire and inspire in work that is also so uncomfortable, so problematical?” So why does she write in the Mythos in the first place? Because she wants to argue with Lovecraft: “I want to argue with his deterministic view of genetics and morality, his apparent horror of interracial marriage and the resulting influence on the gene pool.” She places this arguing at the heart of her writing: “In a lot of ways, I think that is what literature is about; these ongoing conversations” (“Why We Still Write”). Note how “argu[ing]” is an affirmative gesture, not a disavowal (which would preclude arguing) or apologism (which would explain away what one could also argue about). Emrys voices a similar concern: she notes that Lovecraft’s “creations are rich in wonder and yes, in terror,” but she simultaneously realizes that “I am one of Lovecraft’s monsters,”

which “shapes [her] reading inescapably” (Pillsworth and Emrys, “Finding the Other Within”).⁹ Both authors chose to grapple with this tension not by disavowing, nor by apologizing for, Lovecraft’s racism. Instead, it is affirmed: taken at face value, acknowledged as being there as it is, and then working from there. The result is beautiful fiction and an example for scholarship and the larger fandom to follow.

James Kneale has claimed that “once Lovecraft’s racism is discovered, it is difficult not to read him solely in terms of these fears and hatreds. His pathology represents a critical singularity, from which interpretations struggle to escape” (116-7). This claim points in the right direction, yet it also illustrates some of the sore points in contemporary Lovecraft fandom that I have addressed. First, it is not a matter of discovery; Lovecraft’s racism is conspicuous enough to be noticed immediately. A narrative of “discovering” works hand in hand with narratives of apologism or dismissal. Second, Kneale demonstrates the inability of scholarship and the larger fandom to grapple with Lovecraft’s racism: a critical language of “difficulty” and interpretations “escaping” is a language opposite to one of affirmation; the gesture of acknowledging what there is first. Third, a critical singularity is absolutely necessary in the face of Lovecraft’s ever-increasing ubiquity, but it is not one from which interpretations struggle to escape. On the contrary, interpretations should move closer to the facts—Lovecraft’s legacy of racism—and not further away. Interpretations should include Lovecraft’s racism, but “struggling to escape” from it is not the required critical attitude. Instead, the critical singularity required is one of struggling to acknowledge “his pathology”: an alternative affirmative approach to Lovecraft’s legacy of racism.

Post-Lovecraftian fiction shows what Lovecraft fandom can be. Neither disavowal nor apologism affirm—or, in Bear’s words, “argue”—with Lovecraft’s racism; there’s no actual conversation about how to deal with the non-innocent parts of his legacy. Instead, both approaches dance around the issue at stake, leading to others filling in the gap—with white nationalist discourse as the worst possibility—which forecloses all conversation. I mentioned in the introduction that I hold two elements of the Mythos responsible for Lovecraft’s contemporary ubiquity: its collaborative nature and its racist underpinnings. A specific segment of the contemporary Mythos, post-Lovecraftian fiction, created by fans, shows us how the rest of fandom can follow suit, existing at the intersection of these two elements. Subsequently, Lovecraft scholarship can follow. It must, if it is to remain sustainable. It must, when it comes to a celebrated, but racist, author’s legacy.

It is simultaneously peculiar and not surprising that fandom, not scholarship or criticism, is the pioneering force forging ahead in attempting to find a possible alternate approach to Lovecraft’s legacy. Peculiar, because it showcases a certain lack in Lovecraft scholarship, a certain sense of being hung up on ways of grappling with Lovecraft’s non-innocent legacy of racism which rely on bankrupt approaches. Not surprising, because fandom has often been ahead in matters such as these, as the emergence of postLovecraftian fiction once again shows. It is time to follow suit.

1 There are more approaches to Lovecraft’s racism, such as feigned ignorance to its existence or refusing to acknowledge it at all. Nevertheless, these approaches are more niche and not as often seen in fandom. For example, feigned ignorance of Lovecraft’s racism is associated with commercial and/or public enterprises involving Lovecraft’s image, as these enterprises can have a vested interest in not mentioning the deplorable part of Lovecraft’s legacy. Due to these approaches being less common and less associated with fandom, I leave them out of my analysis.

2 For example, Sarah Monette’s The Bone Key (2007), Elizabeth Bear’s Shoggoths in Bloom (2008), Ruthanna Emrys’ The Innsmouth Legacy series (2014-2018), the short story collection She Walks in Shadows edited by Silvia Morena-Garcia (2015), Kij Johnson’s The Dream-Quest of Vellit Boe (2016), Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Thom (2016), Nick Mamatas’ I am Providence (2016), Matt Ruff’s well-known Lovecraft Country (2016), turned into a an HBO TV series by Misha Green (2020), and Phipps himself, with his Cthulhu Armageddon (2016) and The Tower of Zhaal (2017).

3 There are some noticeable exceptions in criticism (Kneale; Kumler; Saler) that have caught wind of fiction’s head start in this matter, but they fall short of formulating a unified critical approach.

⁴ I have chosen not to reproduce Lovecraft’s hateful speech. The exception is figure 1, which would lose its meaning if censored.

⁵ On the contrary, I maintain that post-Lovecraftian fiction exists exactly at this intersection of Lovecraft’s racism and anti-racist thinking. The crucial difference, however, is that post-Lovecraftian fiction takes an affirmative approach to Lovecraft’s trouble, whereas disavowal does away with anything Lovecraftian altogether. I return to this difference later on.

⁶ So many forms, that a tongue-in-cheek bingo card containing often-seen apologisms was created (“Lovecraft Apologist Bingo!”).

⁷ Classical Lovecraft scholarship is the longest-established style of Lovecraft scholarship that focuses on biographical, aesthetic, and philosophical criticism. It traces its beginnings back to the 1970s and 1980s (Mosig; Burleson; Joshi). For the last few decades, it has been represented most prominently by independent scholar S. T. Joshi.

⁸ Although my views on Lovecraft’s racism do not align with Joshi’s (cf. Joshi, “Racism and Recognition”), my work, like almost all modern Lovecraft scholarship, is highly indebted to his indefatigable and pioneering biographical work on Lovecraft.

⁹ This comment parallels Nnedi Okorafor’s comments on the subject: “Many of The Elders [i.e. great artists influential to Okorafor] we honor and need to learn from hate or hated us” (2011b). Although Okorafor does not write in the Mythos herself, this shows again that issue is larger than Lovecraft only.

Ball, Meghan. “Stop Giving Awards to Dead Racists: On Lovecraft and the Retro Hugos.” Nightfire, 5 Aug. 2020, tornightfire.com/stop-giving-awards-to-dead-racists-on-lovecraft-and-the-retrohugos/.

Baxter, Charles. “The Hideous Unknown of H. P. Lovecraft.” The New York Review of Books, 18 Dec. 2014, www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/12/18/hideous-unknown-hp-lovecraft/.

Bear, Elizabeth. “Why We Still Write Lovecraftian Pastiche.” Tor, 4 Dec. 2009, www.tor. com/2009/12/04/why-we-still-write-lovecraft-pastiche/.

“Shoggoths in Bloom.” 2008. Shoggoths in Bloom, Prime Books, 2012, pp. 180-199.

Bimmler, Heinrich. “H. P. Lovecraft – Writings on Race and Culture.” Stormfront, 18 Dec. 2010, www.stormfront.org/forum/t765398/.

Braidotti, Rosi. “Putting the Active Back in Activism.” New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/ Politics, vol. 68: Deleuzian Politics, 2009, 42-57.

Burleson, Donald R. H. P. Lovecraft: A Critical Study. Greenwood Press, 1980.

Chatziioannou, Alexander. “2019: The Year of Cosmic Horror Games.” AV Club, 21 Dec. 2019, games.avclub.com/2019-the-year-of-cosmic-horror-games-1840400500.

Claverie, Ezra. “Lovecraft Fandom(s): Racism, Denial, and White Nationalism.” Intensities: The Journal of Cult Media, 6, Autumn/Winter 2013, pp. 80-110.

Contreras, Crystal. “It’s Too Late to Redeem HP Lovecraft, Who Was An Unapologetic Racist and An ti-Semite.” Williamette Week, 18 Dec. 2017, www.wweek.com/culture/2017/12/18/its-too-late-toredeem-hp-lovecraft-who-was-an-unapologetic-racist-and-anti-semite/.

“Cosmic Horror.” Radish, 21 Apr. 2014, radishmag.wordpress.com/2014/04/21/cosmic-horror/.

Covington, Harold. “Covington Communique – June 30, 2004.” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, 2004, www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/question/2004/july.htm.

Coulombe, Charles. “H. P. Lovecraft is Cancelled.” Crisis Magazine, 15 Sept. 2020, www.crisismagazine.com/2020/h-p-lovecraft-is-cancelled.

Cruz, Lenika. “‘Political Correctness’ Won’t Ruin H. P. Lovecraft’s Legacy.” The Atlantic, 12 Nov. 2015, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/11/hp-lovecraft-world-fantasy-awards/415485/

Davis, Sonia H. Greene Lovecraft. The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft. Necronomicon Press, 1985.

De Camp, Lyon Sprague. H. P. Lovecraft: A Biography. Doubleday, 1975.

Emrys, Ruthanna. The Litany of Earth Tor, 2014.

Winter Tide. Tor, 2017.

Deep Roots. Tor, 2018.

Flood, Alison. “HP Lovecraft biographer rages against ditching of author as fantasy prize emblem.” The Guardian, 11 Nov. 2015, www.theguardian.com/books/2015/nov/11/hp-lovecraft-biographerrages-against-ditching-of-author-as-fantasy-prize-emblem.

Gault, Matthew. “‘Call of Cthulhu’ Shows We Need to Move Past H. P. Lovecraft Once and For All.” Motherboard, 1 Nov. 2018, www.vice.com/en/article/zm9jyx/call-of-cthulhu-shows-we-need-tomove-past-hp-lovecraft-once-and-for-all.

Gray, John. “Weird realism: John Gray on the moral universe of H P Lovecraft.” New Statesman, 24 Oct. 2014, www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/10/weird-realism-john-gray-moral-universe-hp-lovecraft.

Greer, Sam. “Games really need to fall out of love with Lovecraft.” Eurogamer, 10 Oct. 2018, www.eurogamer.net/articles/2018-10-09-games-really-need-to-fall-out-of-love-with-lovecraft.

Guran, Paula. “Introduction: Who, What, When, Where, Why.” The Mammoth Book of Cthulhu: New Lovecraftian Fiction. Edited by Paula Guran, Robinson, 2016, pp. i-vii.

Harman, Graham. Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Zero Books, 2012.

“H. P. Lovecraft: Tales.” Library of America, https://www.loa.org/books/223-tales.

Johnson, Kij. The Dream-Quest of Vellit Boe. Tor, 2016.

Jones, Stephen, editor. Necronomicon: The Best Weird Tales of H. P. Lovecraft. Gollancz, 2008.

Joshi, S. T. H. P. Lovecraft: Four Decades of Criticism. Ohio University Press, 1980.

A Subtler Magick: The Writings and Philosophy of H. P. Lovecraft. Wildside Press, 1996.

A Dreamer and a Visionary: H. P. Lovecraft in His Time. Liverpool University Press, 2001.

“Reply to Charles Baxter’s “The Hideous Unknown of H. P. Lovecraft”.” Stjoshi, 2014, stjoshi.org/review_baxter.html.

“The World Fantasy Award.” Stjoshi, 10 Nov. 2015, stjoshi.org/news2015.html.

“More Crusades for the Crusaders!” Stjoshi, 19 Nov. 2015, stjoshi.org/news2015.html.

“Once More With Feeling.” Stjoshi, 24 Dec. 2015, stjoshi.org/news2015.html.

“Paula Guran on Lovecraft.” Stjoshi, 7 Aug. 2016, stjoshi.org/news2016.html.

“Why Michel Houellebecq is Wrong about Lovecraft’s Racism.” Lovecraft Annual, no. 12, 2018, pp. 43-50.

“H. P. Lovecraft’s Racism and Recognition.” The Truth Seeker, Sept./Dec. 2020, thetruthseeker.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/TS-Sep-Dec-2020-reader-web-pw.pdf.

Kneale, James. ““Indifference Would be Such a Relief”: Race and Weird Geography in Victor LaValle and Matt Ruff’s Dialogues with H. P. Lovecraft.” Spaces and Fictions of the Weird and the Fantastic: Ecologies, Geographies, Oddities. Edited by Julius Greve and Florian Zappe, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Knittel, Susanne. “Memory and Repetition: Reenactment as an Affirmative Critical Practice.” New German Critique, vol. 46, no. 2, 2019, pp. 171-195.

Kumler, David. Into the Seething Vortex: Occult Horror and the Subversion of the Realistic. 2020. University of Washington, PhD dissertation.

LaValle, Victor. The Ballad of Black Tom. Tor, 2016.

Leiber, Fritz. “A Literary Copernicus.” Something About Cats and Other Pieces. Edited by August Derleth, Arkham House, 1949, pp. 290-303.

Lewis, Sophie. “Cthulhu plays no role for me.” Viewpoint Magazine, 8 May 2017, viewpointmag. com/2017/05/08/cthulhu-plays-no-role-for-me/.

Logan, Rayford Whittingham. The Betrayal of the Negro, from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson. 1965. Da Capo Press, 1997.

“Lovecraft Apologist Bingo!” Buzzword Bingo Game.

Lovecraft, H. P. “On the Creation of N-----s.” Howard P. Lovecraft Collection, Brown Digital Repository, 1912, repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:425397/.

“The Terrible Old Man.” The H. P. Lovecraft Archive, 1921, www.hplovecraft.com/ writings/texts/fiction/tom.aspx.

“Herbert West—Reanimator.” 1922. Necronomicon: The Best Weird Tales of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by Stephen Jones, Gollancz, 2008, pp. 34-57.

“He.” The H. P. Lovecraft Archive, 1926, www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/ fiction/he.aspx.

“The Horror at Red Hook.” 1927. Necronomicon: The Best Weird Tales of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by Stephen Jones, Gollancz, 2008, pp. 148-165.

1936. “The Shadow over Innsmouth.” Necronomicon: The Best Weird Tales of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by Stephen Jones, Gollancz, 2008, pp. 504-554.

1936. “At the Mountains of Madness.” Necronomicon: The Best Weird Tales of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by Stephen Jones, Gollancz, 2008, pp. 422-403.

Selected Letters of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, vol. 1: 1911-1924, Arkham House, 1964.

Selected Letters of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by August Derleth and James Turner, vol. 4: 1932-1934, Arkham House, 1976.

Collected Essays of H. P. Lovecraft. Edited by S. T. Joshi, vol. 1: Amateur Journalism, Hippocampus Press, 2004.

Letters to Rheinhart Kleiner. Edited by S. T. Joshi and David E. Schultz, Hippocampus Press, 2005.

Lovecraft, H. P, and Zealia Bishop. “Medusa’s Coil.” 1939. Medusa’s Coil and Others. Edited by S. T. Joshi, The Annotated Revisions and Collaborations of H. P. Lovecraft vol. 2, Arcane Wisdom Press, 2012.

“The Mound.” 1940. The Crawling Chaos and Others. Edited by S. T. Joshi, The Annotated Revisions and Collaborations of H. P. Lovecraft vol. 1, Arcane Wisdom Press, 2012.

Lovett-Graff, Bennett. “Shadows over Lovecraft: Reactionary Fantasy and Immigrant Eugenics.” Extrapolation, vol. 38, issue 3, Fall 1997, pp. 175-184.

Mamatas, Nick. I Am Providence. Night Shade Books, 2016.

Maroney, Kevin J. “Change of Face, Change of Heart.” The New York Review of Science Fiction, 17 Sept. 2014, www.nyrsf.com/2014/09/issue-312-august-2014-editorial-chance-of-face-change-ofheart.html.

Monette, Sarah. The Bone Key: The Necromantic Mysteries of Kyle Murchison Booth. Prime Books, 2007.

Moreno-Garcia, Silvia, and Paula R. Stiles, editors. She Walks in Shadows. Innsmouth Free Press, 2015.

Morton, James Ferdinand. The Curse of Race Prejudice, 1906, catalog.hathitrust.org/ Record/000339229/Cite.

Mosig, Dirk W. “Toward a Greater Appreciation of Lovecraft: The Analytical Approach.” Whispers, vol. 1, no. 1, 1973, pp. 22-23.

Newitz, Annalee. Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture. Duke University Press, 2006.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “The King of Weird.” The New York Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 17, 1996, www.nybooks.com/articles/1996/10/31/the-king-of-weird/.

Okorafor, Nnedi. Who Fears Death. Penguin, 2010.

“A friend of mine wanted to see my World Fantasy Award Trophy.” Facebook, 12 Dec. 2011, www.facebook.com/nnedi/posts/202998716452953?notif_t=share_comment.

“Lovecraft’s racism & The World Fantasy Award statuette, with comments from China Miéville.” Nnedi’s Wahala Zone Blog, 14 Dec. 2011, nnedi.blogspot.com/2011/12/lovecraftsracism-world-fantasy-award.html.

Older, Daniel José. “Make Octavia Butler the WFA Statue Instead of Lovecraft.” Change, 2014, www.change.org/p/the-world-fantasy-award-make-octavia-butler-the-wfa-statue-instead-oflovecraft. Petition.

Omidsalar, Alejandro. “Posthumanism and Un-Endings: How Ligotti Deranges Lovecraft’s Cosmic Horror.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 51, no. 3, June 2018, pp. 716-734.

Paz, César Guarde. “Race and War in the Lovecraft Mythos: A Philosophical Reflection.” Lovecraft Annual, No. 6, 2012, pp. 3-35.

Pechorin. “H. P. Lovecraft on the negro, with reference to the distinction between race and culture.” Pechorin: A Hero of Our Time, 5 Sept. 2015, pechorin2.wordpress.com/2012/09/05/h-p-lovecrafton-the-negro-with-reference-to-the-distinction-between-race-and-culture/.

Phipps, C. T. “What is Post-Lovecraftian Fiction?” The United Federation of Charles, 5 July 2014, unitedfederationofcharles.blogspot.com/2014/07/what-is-post-lovecraftian.html.

Cthulhu Armageddon. Crossroad Press, 2016.

The Tower of Zhaal. Crossroad Press, 2017.

Pillsworth, Anne M., and Ruthanna Emrys. “Finding the Other Within: “The Shadow over Innsmouth”.” Tor, 23 Sept. 2014, www.tor.com/2014/09/23/hp-lovecraft-reread-the-shadow-over-innsmouth/

“Taking a Baseball Bat to Cthulhu: Watching the First Two Episoded of Lovecraft Country.” Tor, 9 Sept. 2020.

Ruff, Matt. Lovecraft Country. HarperCollins, 2016.

Saler, Michael. “Spinning H. P. Lovecraft: A Villain or Hero of Our Times.” Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Social Change. Edited by Henry Jenkins, Gabriel PetersLazaro, and Sangita Shresthova, New York University Press, 2020, pp. 51-59.

Schnelbach, Leah. “Should the World Fantasy Award be Changed?” Tor, 20 Aug. 2014, www.tor.com/2014/08/20/should-the-world-fantasy-award-be-changed/.

Schweitzer, Darrell. Discovering H. P. Lovecraft. Wildside Press LLC, 2012.

Sederholm, Carl H., and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, editors. The Age of Lovecraft. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Sperling, Ali. “H. P. Lovecraft’s Weird Body.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, 31, 2017, doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/031.e09.

Steiner, Bernd. H. P. Lovecraft and the Literature of the Fantastic: Explorations in a Literary Genre. GRIN Verlag, 2005.

Stevenson, Steven. “Keep the beloved H. P. Lovecraft caricature busts (‘Howards’) as World Fantasy Awards trophies, don’t ban them to be PC!” Change, 2014, www.change.org/p/world-fantasyawards-staff-and-the-world-fantasy-convention-keep-the-beloved-h-p-lovecraft-caricature-bustshowards-as-world-fantasy-awards-trophies-don-t-ban-them-to-be-pc. Petition.

“Tales.” Library of America, www.loa.org/books/223-tales.

Tiele, Kathrin. “Affirmation.” Symptoms of the Planetary Condition: A Critical Vocabulary. Edited by Mercedes Bunz, Birgit Mara Kaiser, and Kathrin Thiele, Meson Press, 2017, 25-29.

Walter, Damien. “What do we do about Lovecraft?” DamienWalter, 23 Aug. 2012, damiengwalter.com/2012/08/23/what-do-we-do-about-lovecraft/.

“Was H. P. Lovecraft the most red pilled author ever?” 4chan /pol/ politically incorrect, 2 Mar. 2017, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/114904475/.

“Writers of Color Continue to Wrestle With Lovecraft’s Racist Legacy.” Wired, 1 June 2017, www.wired.com/2017/01/geeks-guide-writers-of-color-lovecraft/.

Most readers remember characters by their actions—and, sometimes, by a single “identifying” action or trait. This is true of Boromir from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: readers most often remember him as the guy who tried to steal the Ring from Frodo. Edmund Pevensie of C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia is treated similarly: he is often identified, halfjokingly, as the kid who sold out his siblings for some candy—not even good candy, at that. While it is true that both Boromir and Edmund do betray those to whom they have obligations, there are many other identifiable actions and traits by which a reader might define them—Boromir’s relentless pursuit of allies against Mordor, for instance, or Edmund’s defeat of the White Witch in battle. Associating a character’s identity with a single action, particularly a negative action like betrayal, reduces that character to a straw man. There have been several academic analyses of Boromir’s betrayal and redemption, but not many of Edmund’s. I can find no articles comparing the two characters’ arcs. Using theories from the fields of social and individual psychology in conjunction with narrative analysis, this paper investigates how Boromir and Edmund’s dispositions and motivations influence their character arcs vis-à-vis the Hero’s Journey. The idea is to show that this one-dimensional identification of characters is insufficient to truly describe these characters, and it underplays the significance of their roles in Tolkien’s and Lewis’s stories. This paper argues that Boromir and Edmund becoming villains—albeit temporary villains— deviates from the Hero’s Journey (as coined by Joseph Campbell), but does not preclude their resuming it.

First, what is the Hero’s Journey? In his work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell describes a process of becoming. An archetype known as the Hero sets out on a quest, overcomes dangers untold and hardships unnumbered, and eventually returns home with some token of their success, and they are wholly changed. The first stage of this journey is the call, which spurs the Hero forward into the unknown (Campbell 53), where they must survive a succession of trials (89). The goal, of course, is to achieve the object of the quest—for example, Boromir sets out to investigate the meaning of his brother’s dream—and then, ideally, to return home with the trophy in hand. Campbell’s concept of the Hero’s Journey is therefore cyclical: the Hero ought to return to the beginning. However, he does cite exceptions to the rule: Heroes like the Buddha refuse to return home (179). In other words, some Heroes deviate from their Journies. This indicates that any individual who sets off on some quest is entering in a Hero’s Journey narrative, and that whether they return home is less important than whether they succeed in their quest (consider certain death missions, for example).

To illustrate this concept in the context of this paper’s topic, the below graphic contains three arcing arrows. The first in yellow represents the Hero’s Journey as portrayed by Campbell,

but here a red arrow interrupts the cycle, off-shooting to form a separate circle. In this graphic I have labeled this interruption as the moment of betrayal, the Hero deviating from the narratively expected path. The second circle can become its own journey, and whether the Hero makes it back to the original track depends on their repentance. In the diagram, the Hero does perform a redemptive act, which brings the betrayal arc to its completion, allowing the Hero to reenter the original Journey narrative. That the attempt to redeem oneself leads back to the moment of the betrayal is significant: the Hero cannot erase the past, and must acknowledge their wrongdoing in order to move forward.

Boromir and Edmund both have no choice but to leave their homes (the Initiation stage). As they find themselves in new territory, they must adapt not only to their surroundings but to other characters with whom they interact—and decide whether they are friends or foes—while navigating perils both physical and spiritual (the Trials and Tribulations of the Hero). Betrayals sidetrack both from their journeys, but they both make the decision to redeem themselves and seek forgiveness in one form or another. After redeeming themselves, both Boromir’s and Edmund’s narrative arcs follow the typical paths of the Hero. Boromir does not complete his journey in that he does not return home, but he does continue his journey in some form: the funeral given to him by Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli brings his body on towards the sea—the great unknown—as Faramir’s vision portrays. Given that he survives the Battle of Beruna, Edmund, unlike Boromir, does complete his Hero’s Journey, eventually adopting the nomenclature King Edmund the Just and ruling peacefully alongside his siblings. His relationship with Lucy, especially, improves after the events of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

My purpose here is to discuss Boromir and Edmund’s divergence from and return to the path of the Hero’s Journey. In order to understand the gravity of their actions, both negative and positive, I will delve into social and psychological theories that outline friendship, trust, and the dissolution of these. To answer questions like, “Can we consider Boromir a friend to any of the members of the Fellowship?” or, “Is a nasty sibling like Edmund counted among the Pevensies’ friends?” I will first create a working definition of friendship.

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle describes friendship as a reciprocated feeling of goodwill between two persons. He further classifies three distinctive types of friendship: utility, pleasure, and virtue. Respectively, these are friendships based on achieving a goal or good; friendships founded on exchanging or receiving pleasantries; and—the most desirable form—friendships in which both persons share love and goodwill for the sake of the other’s happiness and health, rather than for any gain or pleasure (although these latter attributes can certainly be present in a virtuous friendship, they are neither the foundation nor the reason for the continuation of that relationship). Aristotle’s thoughts on friendship, for all his examples, are limited in many respects.For example, he does not consider

reconciliation of friends after an argument, let alone a betrayal, which is a conspicuous oversight on his part. A more inclusive definition of friendship and its attributes allows us to look more closely at this concept of betrayal and how it affects friendships. It is helpful to view friendship as a social construct— thus the meaning and expressions of friendship are subject to social change (for instance, hand holding between male companions is common in the Middle East, whereas the practice became relatively taboo in Western society). Not only that, but friendship as a social construct allows individuals to maintain a stable identity (Demir 25). According to Melikşah Demir:

In friendship the recognition of the Other is not only experienced as a cognitive process for the persons involved in the relationship but primarily as a strong emotional process…It is not only a simple recognition and acceptance of the self but an ongoing identity formation process especially in moments of great difficulty. A friend’s support can involve not only giving advice but offering a new perspective for looking at our self, sometimes being harsh and critical to support a transformation. (26-27)

In other words, because we inevitably must define something by what it is not, even in friendship one must delineate oneself from the Other participating in the relationship. At the same time, one must recognize the individuality of the Other and the fact that in any one of the friendship types as outlined by Aristotle (utility, pleasure, virtue), each friend is reciprocating feelings, actions, and words in a continuous cognitive and emotional process. This process entails that each person should be loyal and empathetic to the Other. Indeed, a study of children’s friendship expectations reveals that these qualities are essential (MacEvoy 105). Certainly, these attributes are important in adult relationships as well.

When one feels that an Other exhibits these qualities of loyalty and empathy, one considers him or her to be trustworthy. More broadly defined, trust is “the expectation of good will in others, [which] can apply to specific persons, such as friends or neighbors” (Glanville 230). This recalls most strongly Aristotle’s definition of virtuous friendship, in which feelings of goodwill towards and for one another are reciprocated for the sake of goodwill itself rather than for utility or pleasure. Demir posits that “the desire to be recognized and accepted produces trust in the [Other] and their capacities and abilities” (27). In other words, trust comes down to believing that one bears goodwill towards the Other and that the Other bears goodwill towards one. Therefore, without trust, there can be no betrayal.

It is clear, then, that both the Fellowship and the Pevensy family harbor a certain amount of trust and goodwill among all of their respective members. It is also clear that both parties were betrayed by one of their own. What this doesn’t answer for is why Boromir and Edmund were in the position to become traitors. What led them to take the actions that they did? Might we find some shared personal attributes in Boromir and Edmund that caused them to betray those around them? Although Boromir and Edmund are very different characters, there has been very little analysis into what environmental, familial, or other personal factors could influence these characters’ motivations and desires. A deep reading of the stories demonstrates striking similarities between Boromir and Edmund in several respects: setting, personal growth, desire, and upbringing.

Gondor and London are very similar environments (the name “Gondor” even looks like a perversion or misreading of “London”) which produce characters very much alike: Boromir and Edmund, as well as Faramir and Lucy. These stone cities, by virtue of their hardness, are also considerably sterile;that is, very little of nature can eke out an existence, an idea especially explored in The Lord of the Rings. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, London is only a referenced setting, but one can assume that any natural things struggle in the wake of industrialization and war. In both novels, the fertility of nature is associated with spiritual growth and even happiness: after the wars of Middle Earth and Narnia, Gondor becomes more naturalized by the introduction of vibrant gardens, and the end of Narnia’s ice age brings abundance—and both herald a new order.

The Gondor and London which Boromir and Edmund know are the environments of war;

nevertheless, they are these characters’ comfort zones. There is a certain predictability in knowing that nowhere is safe, that the Enemy can be around every corner; predictability means being able to adapt oneself to circumstances, which is a form of control. Intensifying, encroaching wars essentially evict both characters from their cities, separating them from all they know—the tall stone walls and buildings which protected them from the outside world, but which also isolated them. This isolation, as becomes clear from Boromir and Edmund’s interactions with strangers in new lands, stunts personal growth, particularly in the area of empathy. Although Boromir understands that other peoples and races are in peril, his primary concern, to the point of desperation, is to bring reinforcements to Gondor and save his own people before any others. Despite Edmund’s knowing that his spitefulness harms others, especially Lucy, he does not empathize with the pain and exasperation he causes, and in fact seems to relish it.

The turning point for both characters, the moments in which they realize empathy, occurs in the wilderness. By journeying out of their homes, the stone cities, and into the wilderness where they meet strangers—possible friends, but also possible foes—both Boromir and Edmund forge new connections, making themselves vulnerable by trusting others to stand by them and support them. In order to have a healthy interpersonal relationship, one must have trust, which is defined as “a confident expectation regarding another’s behavior,” and is “necessary between friends to make sure that confidences are not betrayed; that the friend can expect that his/her friend behaves properly and in line with his/her commitments. Reciprocity is also important in ensuring ongoing, happiness-promoting friendships. Feelings of obligation to friends make a person ‘indebted to the donor, and he remains so until he repays’, thus contributing to the stability of the friendship, or in more extreme cases, to the friendship breaking down” (Demir 26). The internal conflict within Boromir and Edmund seems to be a product of the eras in which they live rather than the sterile stone cities themselves: as wars claim lives of potential friends, perhaps it is best not to have friends at all, in order that one avoids the pain of losing them.

After a long search, Boromir finds himself among friends at Rivendell. Though we are not privy to information regarding whom he met along his initial travels, we can assume that he did not forge strong relationships with anyone, given his distrust of those present at Elrond’s house. Accompanying the Fellowship, Boromir sets out on the quest to keep the Ring out of enemy hands, and though he is not hesitant to disagree with the paths they take, “he does not contest [Aragorn’s] authority as the primary decision-maker of the group” (Beebout 6). Instead, he follows the Fellowship where they will, supporting them physically and emotionally through their trials. For example, though he protested the route through Moria, still he endured the path and even stood by Aragorn’s side against the Balrog when Gandalf ordered them to flee. This illustrates that Boromir is a brave and true captain, and though his ability to empathize with other people is underdeveloped throughout most of the novel, his duty to the Fellowship shines clear through his actions. Indeed, Pippin remembers that he “had liked [Boromir] from the first, admiring the great man’s lordly but kindly manner” (Tolkien 792), indicating that despite his stubbornness and prideful demeanor, he was courteous (with, perhaps, the exception being his treatment of Aragorn).

As the Fellowship endures hardship after hardship in the wild, the travelers grow closer as friends—a phenomenon most noticeable in the development between Legolas and Gimli in Lóthlorien. We see it also between Boromir and the others, except for Frodo, who detects a suspicious change in Boromir’s manner after the Fellowship meets Galadriel (Tolkien 360). It seems Boromir could delay persuading Frodo to hand him the Ring for Gondor’s sake until they reached the city, so Boromir did not consciously entertain any thoughts on the matter until Galadriel showed him his heart. This meeting is perhaps what instigated or awakened the lust for the Ring’s power, especially in close proximity. Miryam Librán-Moreno points out that: