BUILDING AS ARCHIVE

BUILDING PROJECT

BUILDING AS ARCHIVE

BUILDING PROJECT

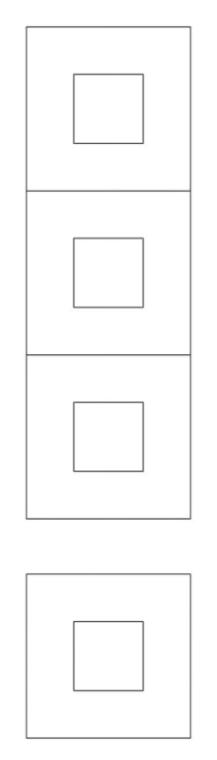

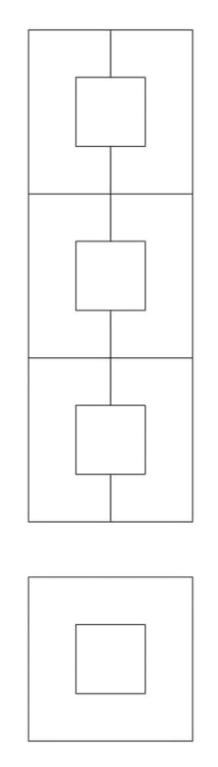

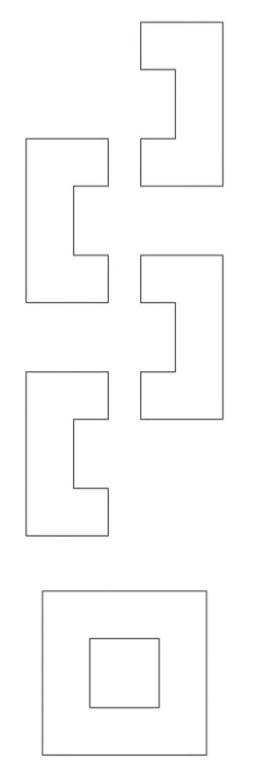

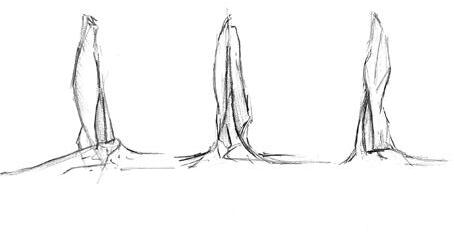

Broken geometries — derived from the Gropius’s formal language — begin by abstracting and subdividing the organic plan of Gropius (U.S. Embassy in Athens), treating it not as a fixed footprint but as a generative formal language. This geometry is subimposed upon itself, overlapped and rotated, creating a dense matrix of spatialrelationships.Astheplanlayers,voidsemerge—momentsofmisalignmentthatbecomeopportunities for paths, courtyards, and thresholds. What was once surface now becomes section; the plan is flipped and embedded, reinterpreted as a subterranean field. Circulation is no longer linear but unfolds through these interstitial geometries, producing a labyrinthine system of movement. From iconic precedent to a new tectonic order—wherearchitecturebecomesa topographicweave ofmemoryandmovement.

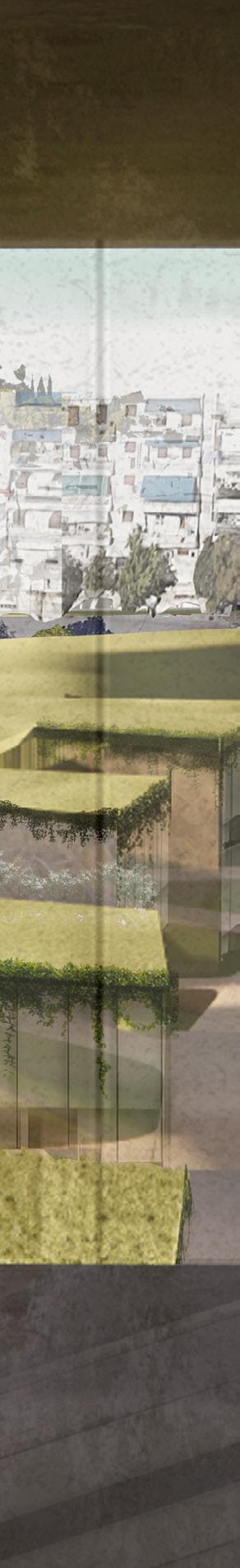

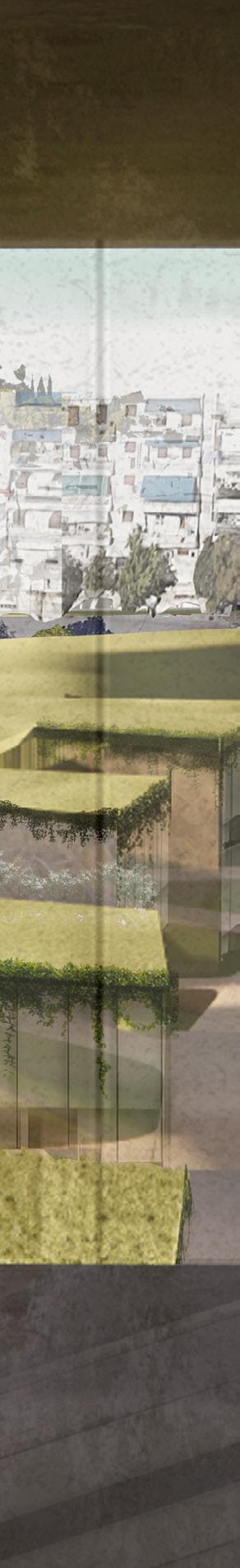

In the heart of Athens, diplomacy finds form through restraint. Rather than assert dominance in a more obvious form, the embassy is nestled into the landscape, seeking alignment with its host rather than contrast. The architecture operates as a mediator — expressing American ideals through spatial transparency and civic generosity, while remaining sensitive to the rhythms and memory of the Greek terrain. The result is a subdued presence, one that speaks softly, and listens first.

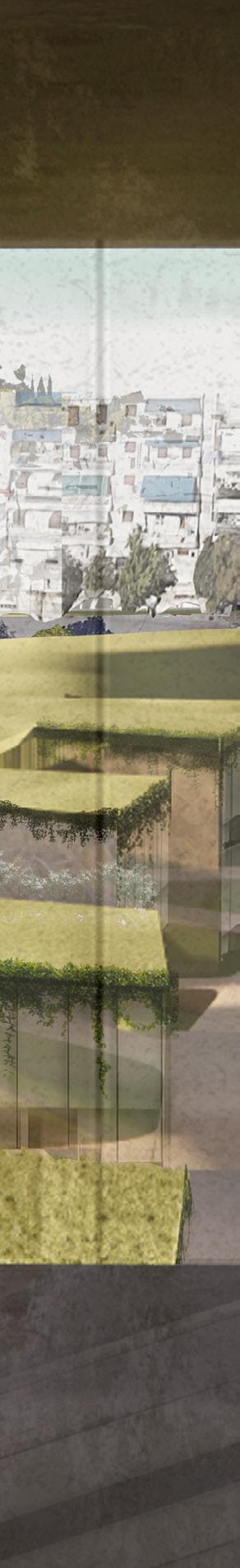

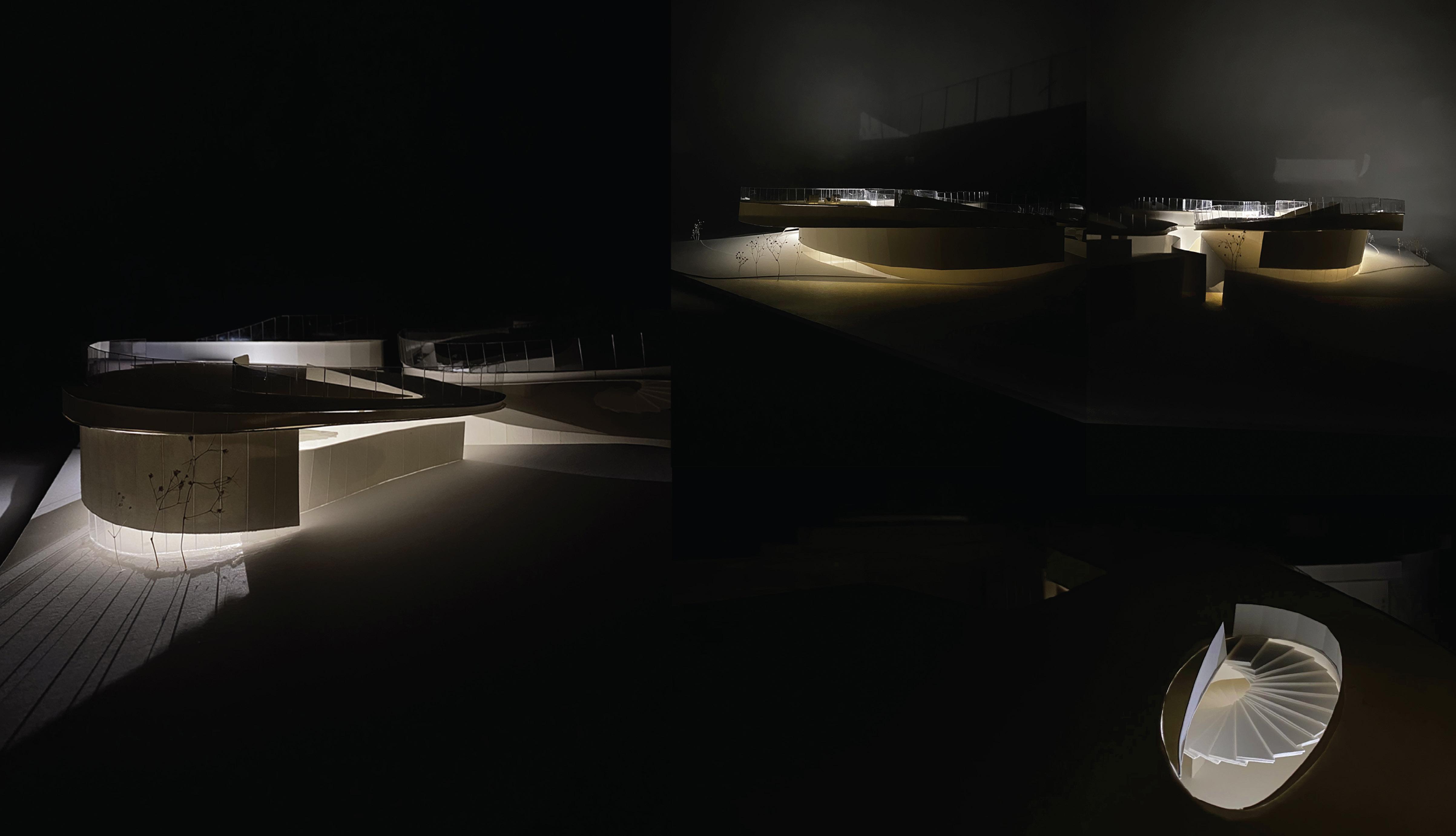

Carving becomes the dominant driver. Subtractive gestures hollow out the site, using excavation to reveal the land. The natural slope of the land becomes a collaborator — guiding circulation, shaping space, and grounding the embassy’s massing. Built forms emerge as remnants of this excavation, appearing as if unearthed rather than erected. Architecture becomes terrain, and terrain becomes architecture — a dialogue between mass and void

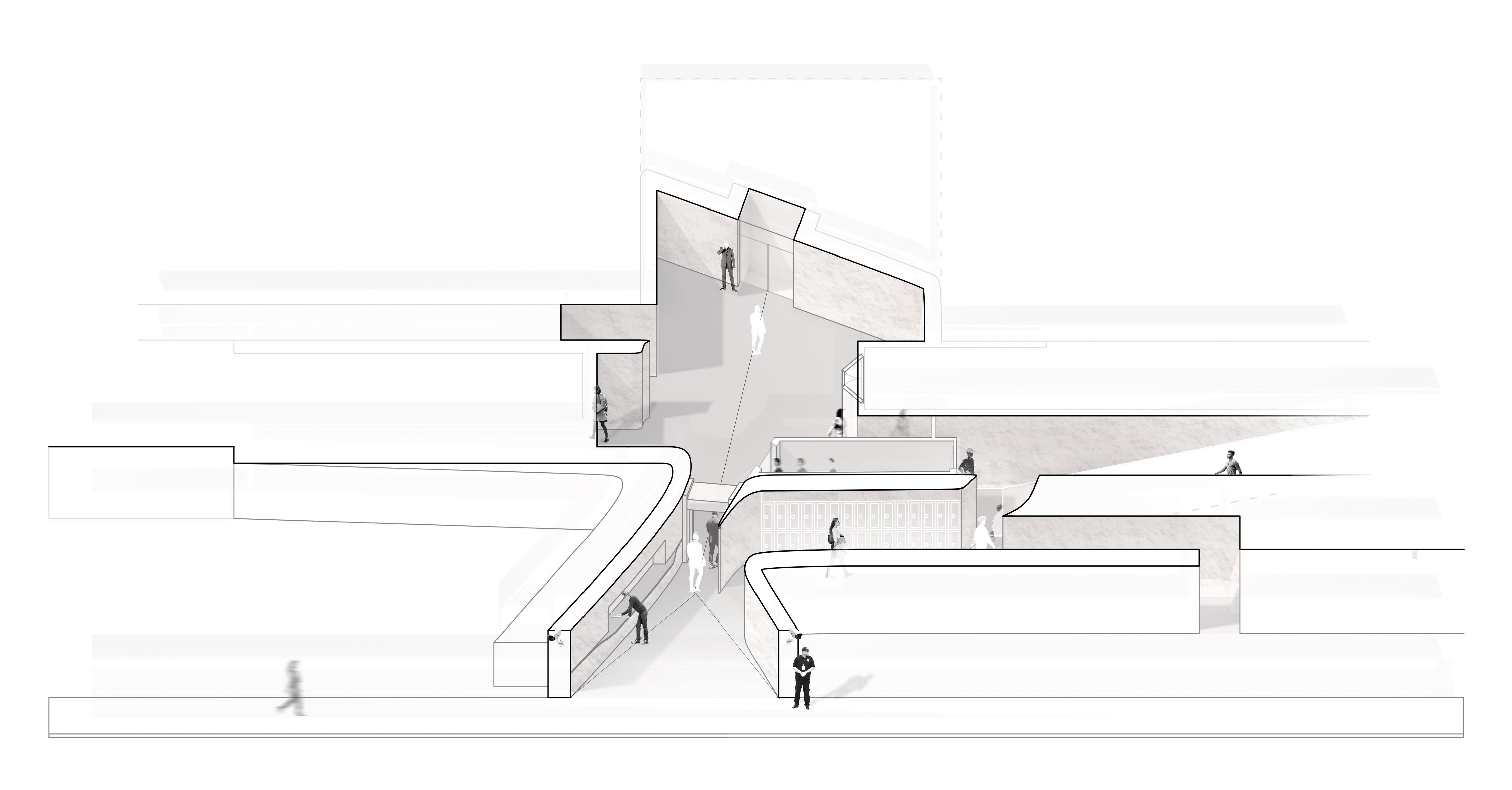

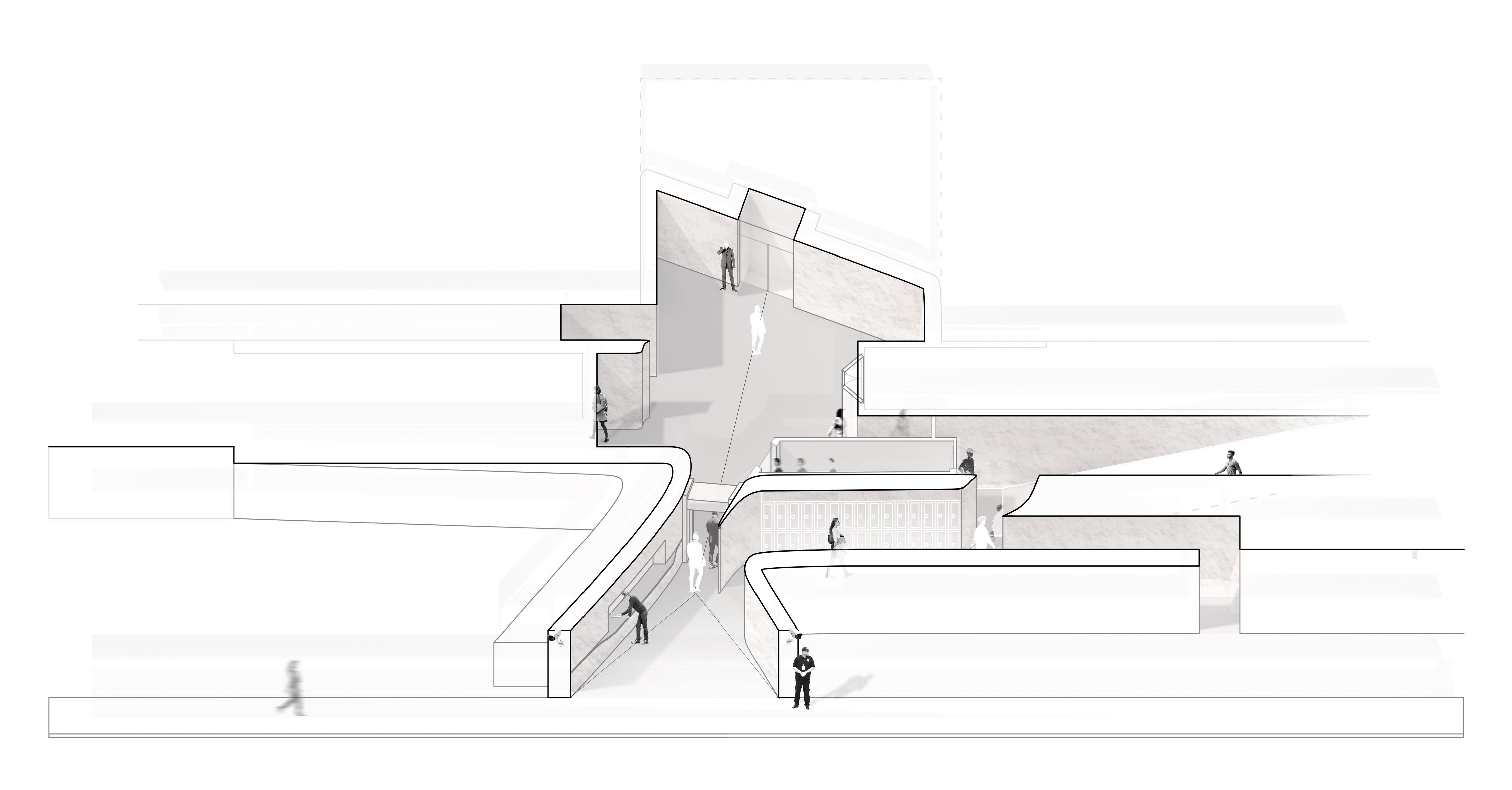

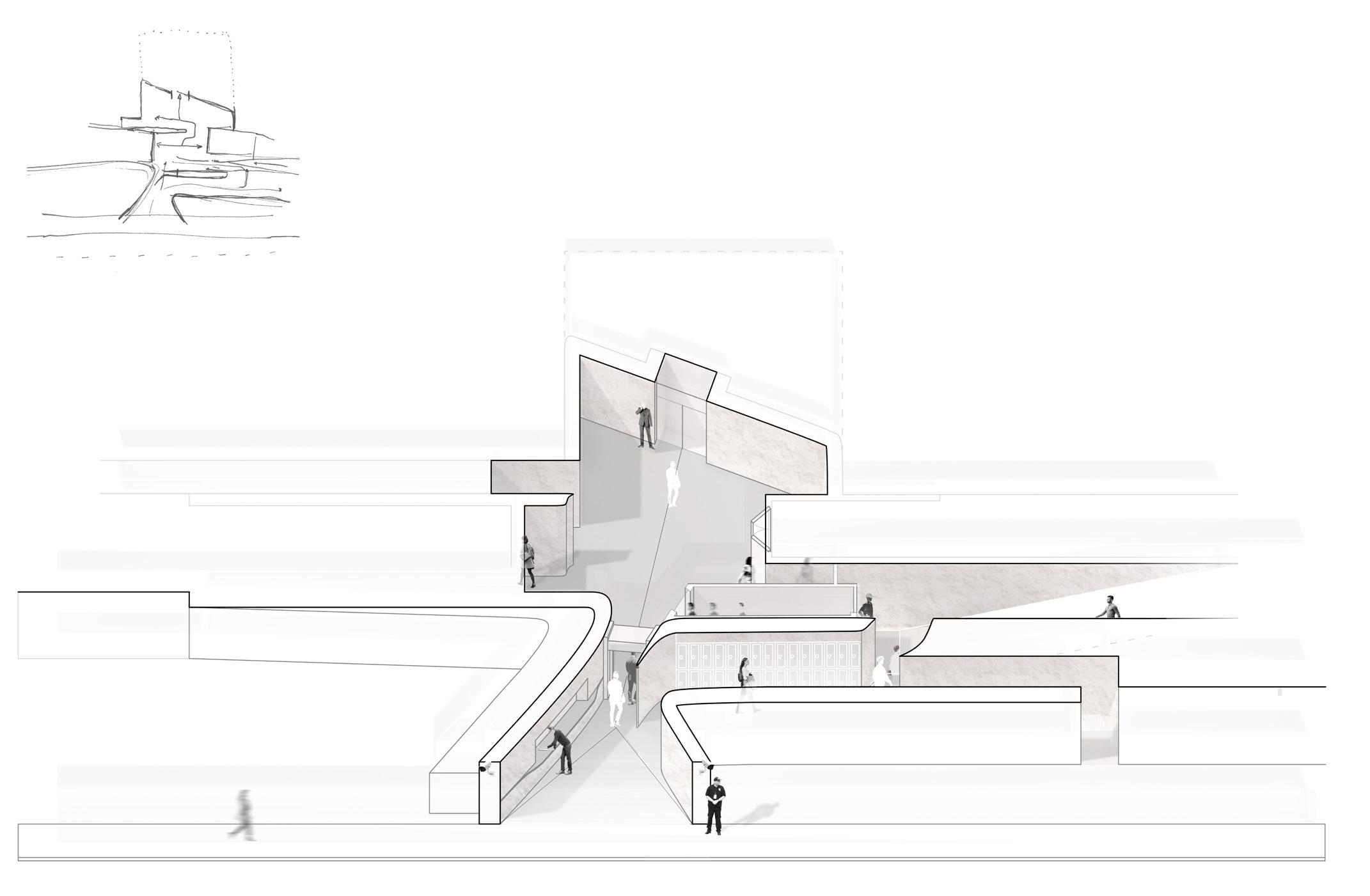

The CAC (Controlled Access Center) marks the entry into the site, balancing the need for strict security with the desire for a welcoming arrival. Partially embedded into the landscape, the CAC uses layered massing, controlled sightlines, and a staggered approach to create a sense of progression. Security measures are integrated into the architecture allowing the space to feel protective rather than confrontational. It acts as both threshold and buffer setting the tone for a secure yet open diplomatic presence.

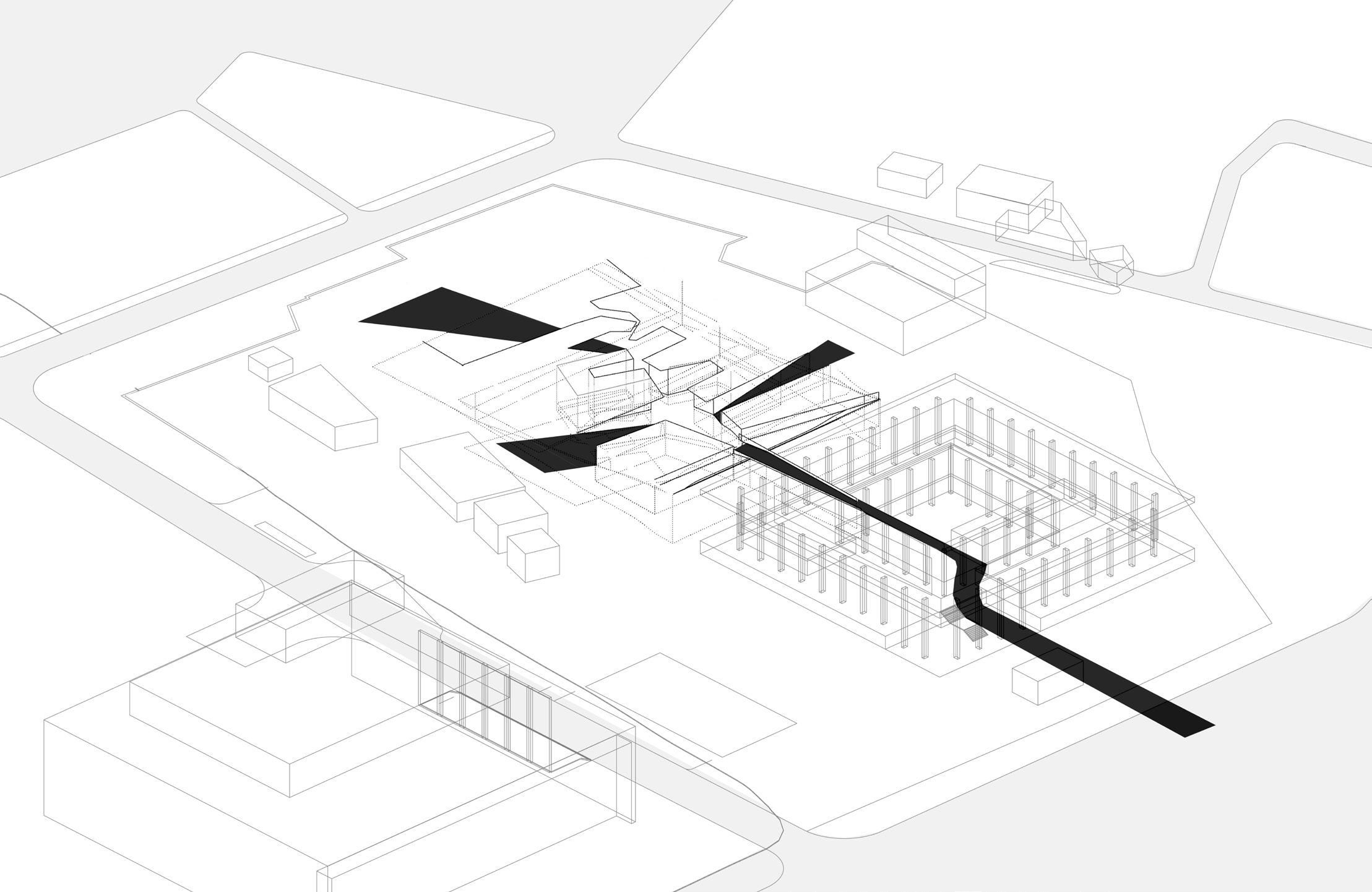

At the subterranean level, the plan unfolds as a continuous field of interconnected programs, embedded into the landscape and shaped by movement, security, and terrain. The site is accessed through four entry points: the existing Gropius embassy, two public CACs on the east and west wings, and a private northern CAC for the ambassador’s residential access.

Programs — including office spaces, military barracks, support zones, and shared areas like the cafeteria and art spaces — shift and slide through the site, branching from a central sunken spine. Circulation is designed as a layered experience, not a direct path, allowing secure and communal zones to overlap subtly. The result is a protected yet fluid system — architecture that moves with the land and connects through form.

A canyon-like spatial sequence threads through the site, orchestrating a slow descent and ascent that unfolds through the interplay of architecture and earth, a subtle nod to the Acropolis. Broken geometries — derived from Gropius’s formal language — fracture into a series of courtyards. These outdoor rooms operate as both spatial relief and connective tissue, openiong up the structures to natural light and open courtyards.

A staggered, stepped spine becomes the project’s central axis — not a straight line of control, but a rhythm of changes in elevation, framing views, bridging spaces. Two primary programmatic zones face one another across the site, their connection maintained through paths that meander, converge, and part. These interwoven routes invite multiple readings of the site, emphasizing both autonomy and interdependence. Buildings and landscape are no longer separate; they are parts of the same sentence.

Returning the ground as a cultural offering through the adaptation of a public park. Above, the roof gives itself back to the city. Transformed into a public green, it extends an invitation rather than a warning — a park in the sky, open and nonthreatening. This gesture subverts the image of the embassy as fortress. Instead, the embassy offers its highest point to the people, framing views of Athens while symbolically bridging the space between what it means to be host and guest.

Here, diplomacy is not just negotiated inside, but expressed outside— through openness, humility, and shared ground.

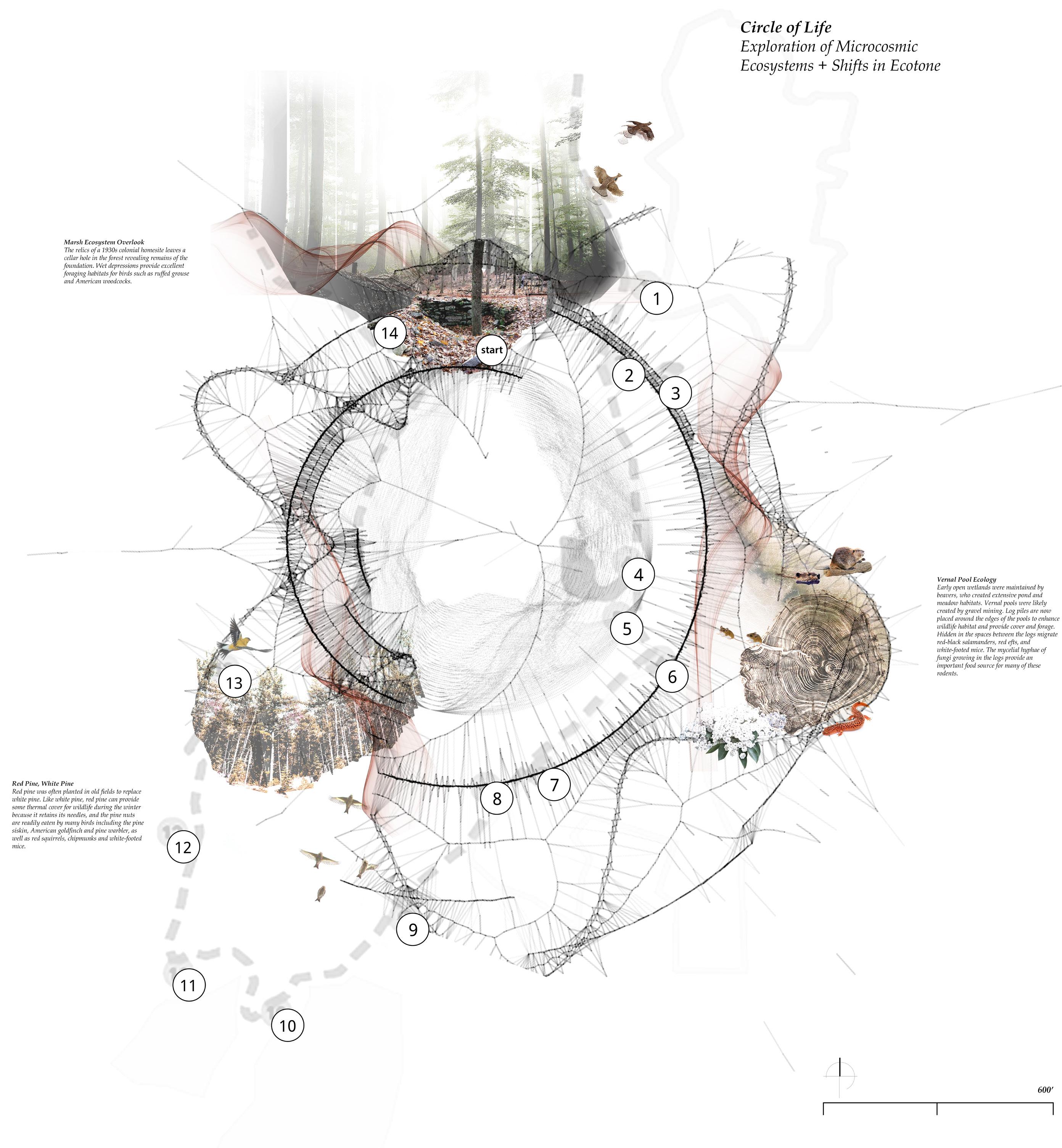

Islands have been used as metaphors to plan cities and have prompted the creation of strange and dramatic infrastructural conditions. As a geographic trope for designers, the island represents both total freedom and total constraint.

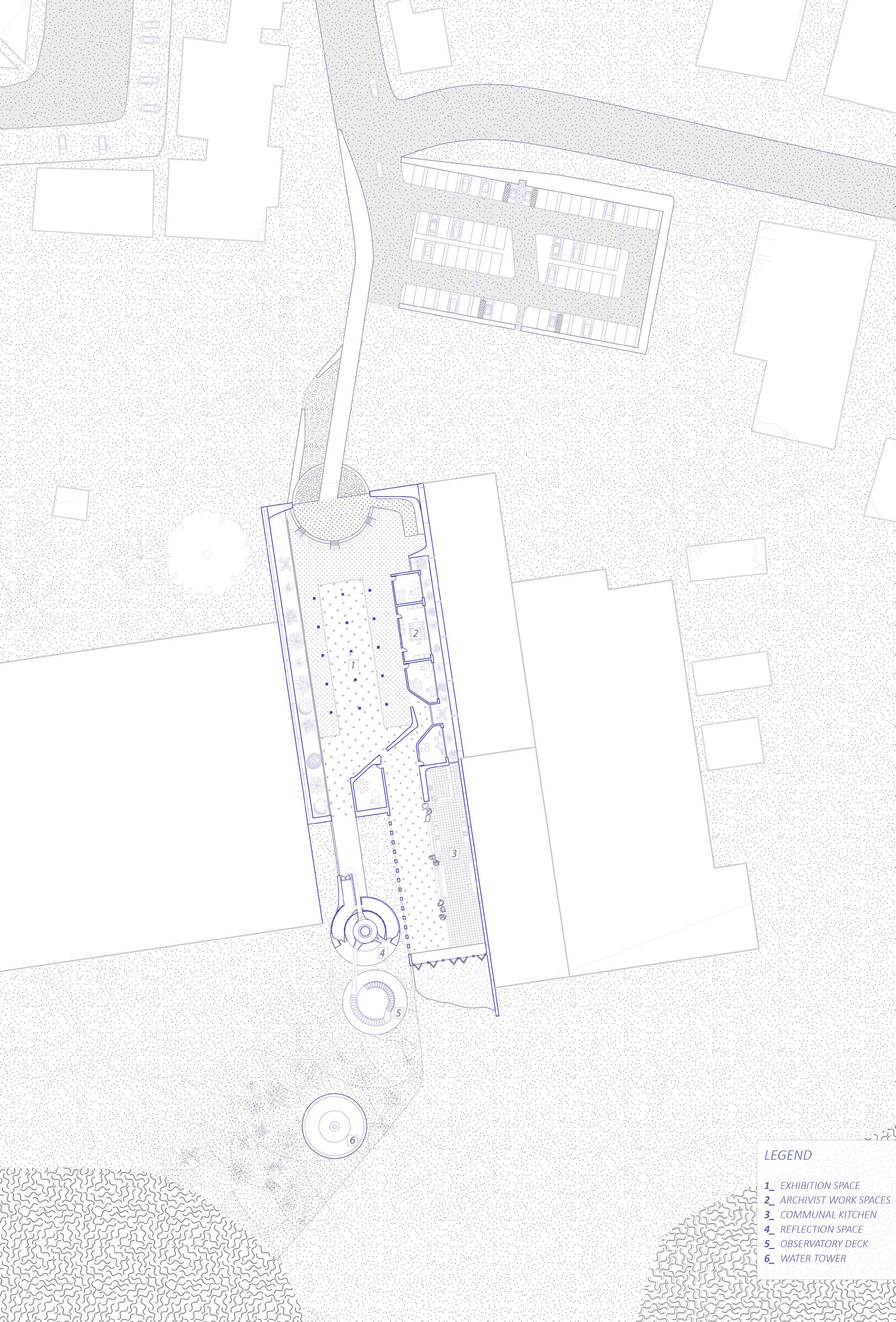

This project, based in the Central Aguirre Historic District in Salinas on the south of the island, addresses the gap between research, archive, memory, and present landscapes via adaptive industrial reuse applications of its former sugar factory and its two remaining chimneys. The Central Aguirre Historic District is the site of a former company town built by an American investment firm to serve its sugar refinery factory. It is a place that encapsulates the U.S. occupation of the island, and the violent extraction landscapes of the wider Caribbean that accumulated around the manufacturing and exportation of sugar.

AACUPR (El Archivo de Arquitectura y Construcción de la Universidad de Puerto Rico) at the University of Puerto Rico holds all of the historic documentation and drawings related to this sugar factory and its site. They are seeking a way to better house these thousands of archival drawings and images as well as a way to revive the forgotten city of Aguirre.

Puerto Rico has extremely diverse landscape typologies- from the highest remote terrains to its more dense urban cities, both being very susceptible to natural disasters. In the south of the island, near Aguirre, Salinas, it is affected mainly by both droughts and flooding that affect Puerto Rico and its inhabitants yearly- being classified as a D3 area of extreme drought. These droughts result in informal approaches to water collection due to the lack of access to clean water during these events, leaving people to individually source water from nearby streams to bottle themselves.

Like Puerto Rico, the island of Cuba has similarities in its geologically diverse landscapes and climatic conditions which foster breeding grounds for new forms of production of many local resources- from limestone extraction to coffee plantations to sugar cane factories. From the mountains of Sierra Maestra in Santiago to Havana’s busy port city, we can explore the movement of various resources that travel from the island’s highest remote terrains to be sent out from its main urban port.

As one walks through the sugar factory, it is evident that the remnants of the fabric of the sugar factory remain as if frozen in time- the evidence of history. These materials and fragments tell the story of Aguirre and the means of production at the time that sustained its city’s economy.

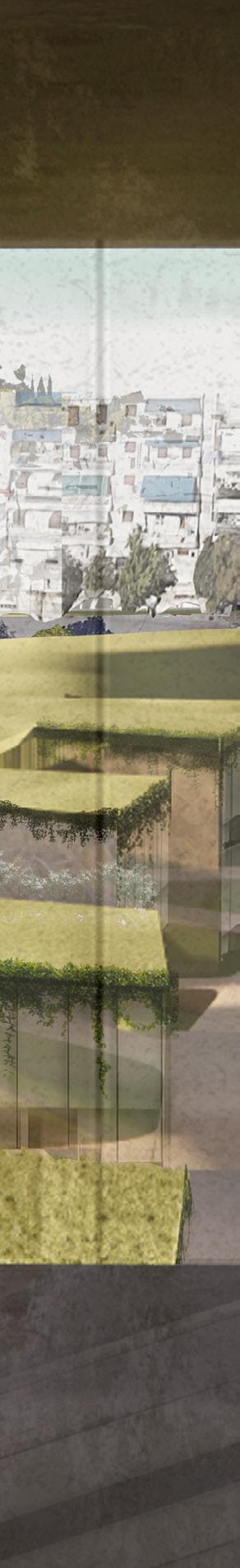

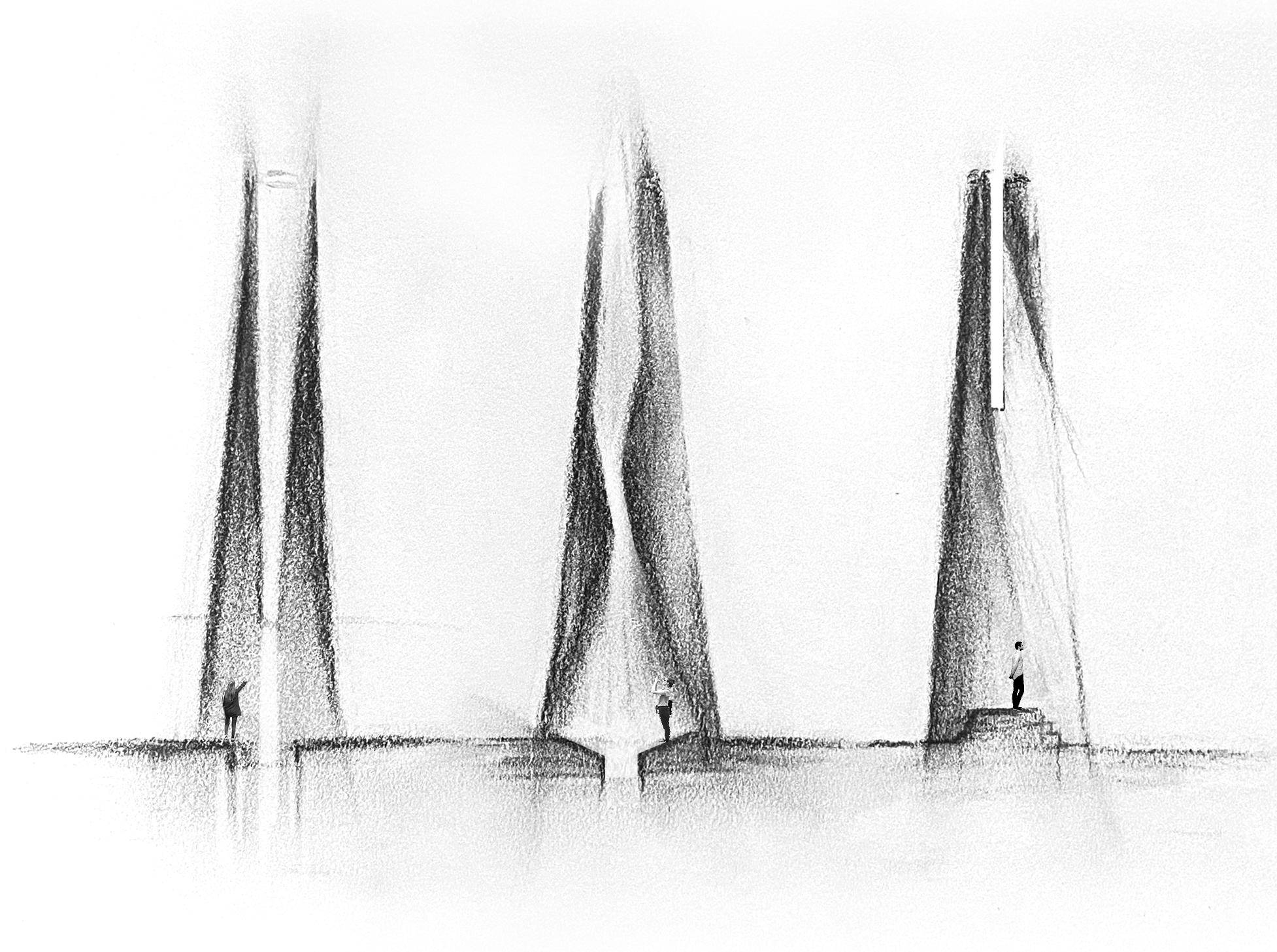

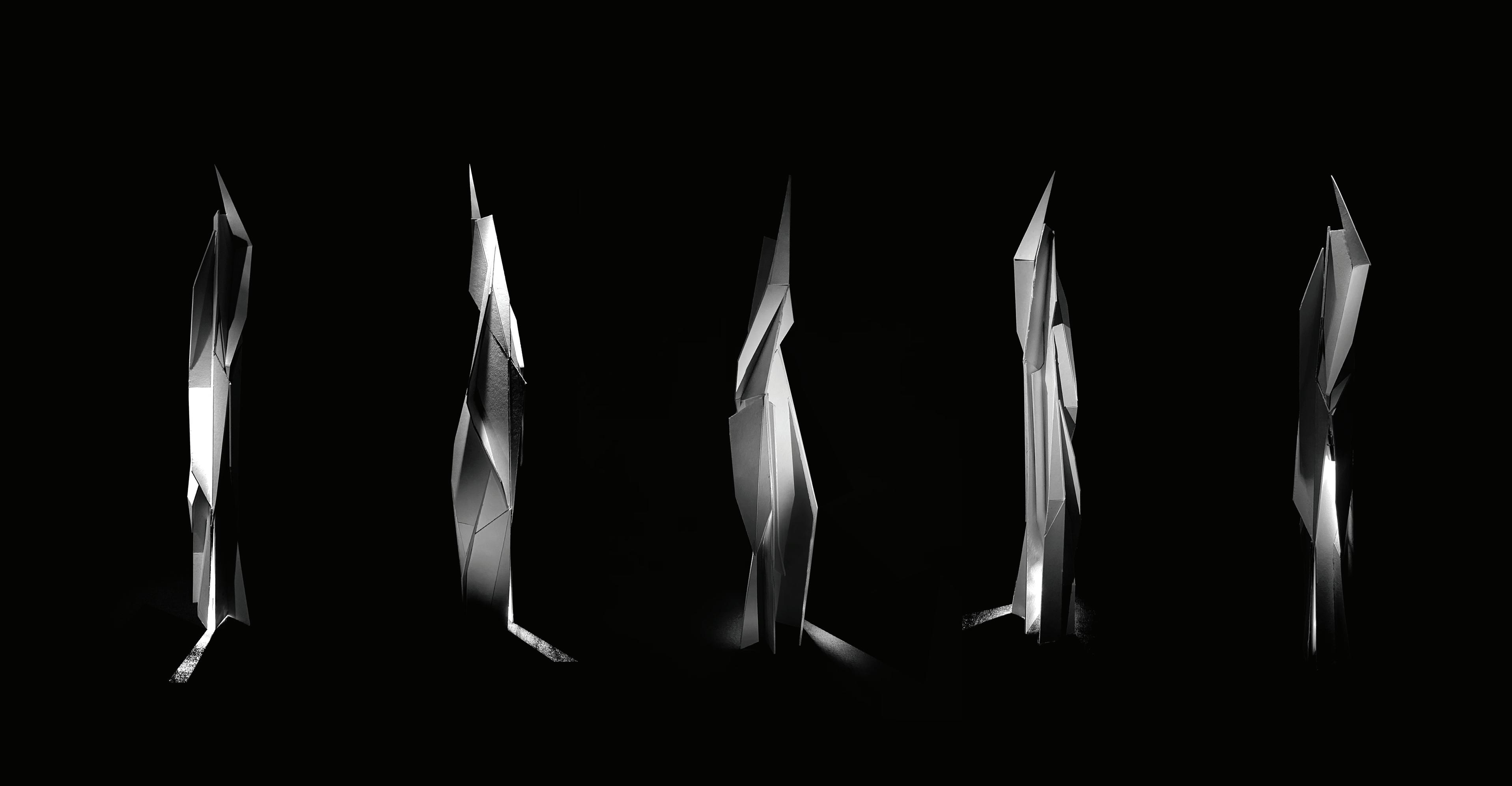

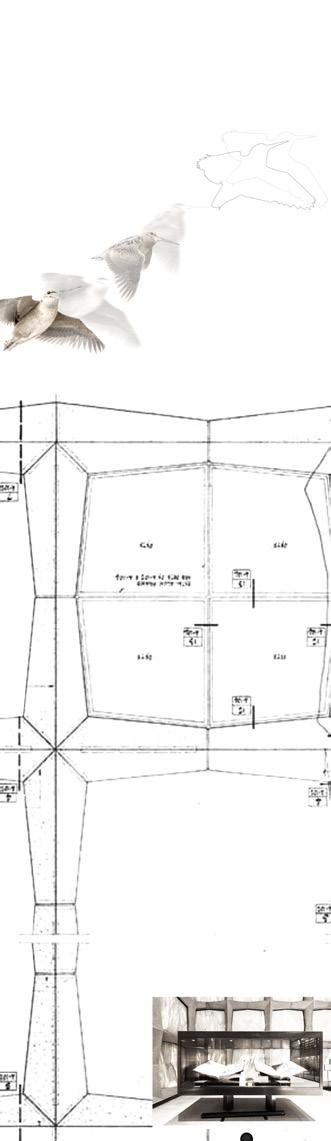

This project treats building as archive, as well as give old structures a new life by restoring the chimneys from ruin to a kind of monument. The two chimneys become main markers for pathfinding. The brick chimney was built in the 1800s by the Spanish. whereas the concrete chimney was built by the U.S. when they took over in the 1900s. The materiality of brick and concrete reference ideas of past and present, alluding to a possible future.

The brick chimney (far left) is reutilized and restored to memorialize the history of its space, illuminating its remnants, creating a contemplative space for reflection and projection of archive and history as well as water collection.

The concrete chimney (middle) takes on the opportunity to frame a view of the city of Aguirre and its waterfront in its present state, serving as an observation point of the city and its tower of the future- the water tower.

This third structure confronts ideas of the future: environmental issues. Flipping the expelling logic of the chimney, a water tower that gathers rather than spews is the seed of a new water retention system on the site. The new system serves as a pilot project for what might be possible for the community in the future. The three structures together become monuments that operate in the past, present, and aim to position the town in a new future, all at once.

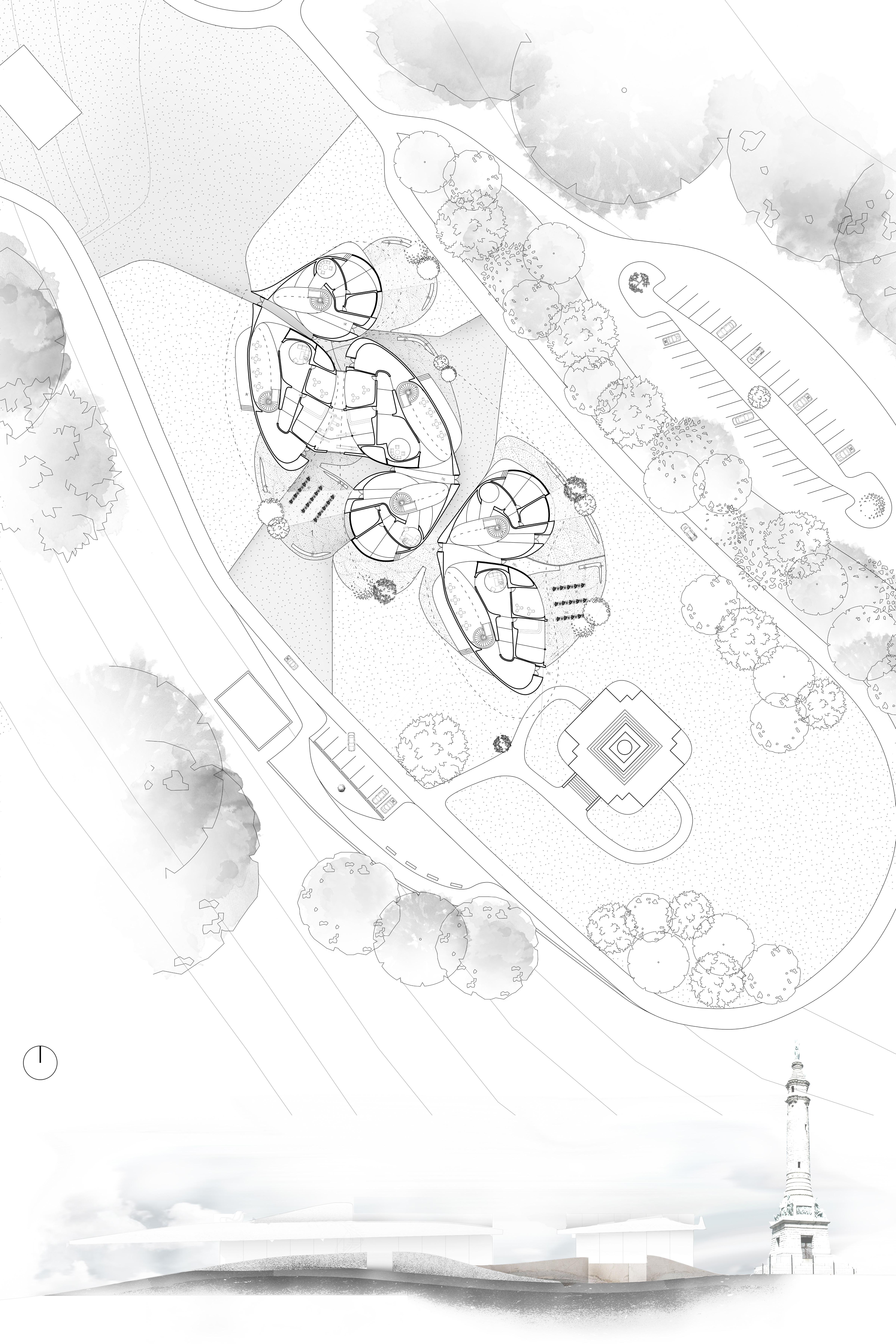

The plan serves as a wayfinder that frames and leads one to the three towering structures: the two chimneys and the new water tower, enforcing a direct axis towards the water. The sugar factory is restored and revitalized as an exhibition space for the archival documents and materials of the factory as well as archivist work spaces with a communal kitchen. The concrete chimney becomes an observatory deck that has a spiral staircase that weaves in and out of the chimney to frame views as one makes their way to the top.

The integration of water collection and storage into the site becomes a central feature, flowing under, through, and above the landscape. This visible display of water management not only serves a practical purpose but also serves as a reminder of the site’s connection to its environment and the importance of sustainable practices.

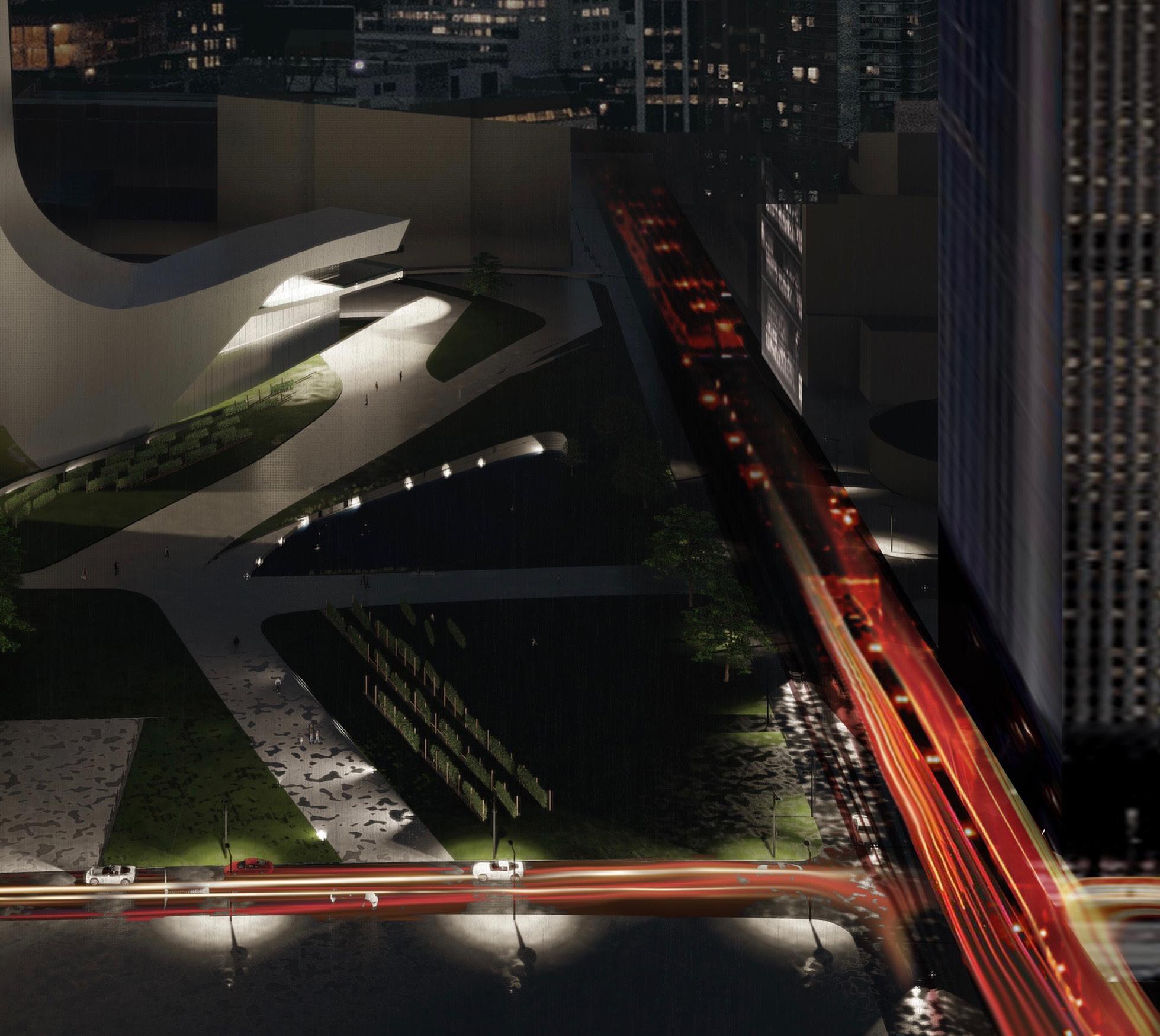

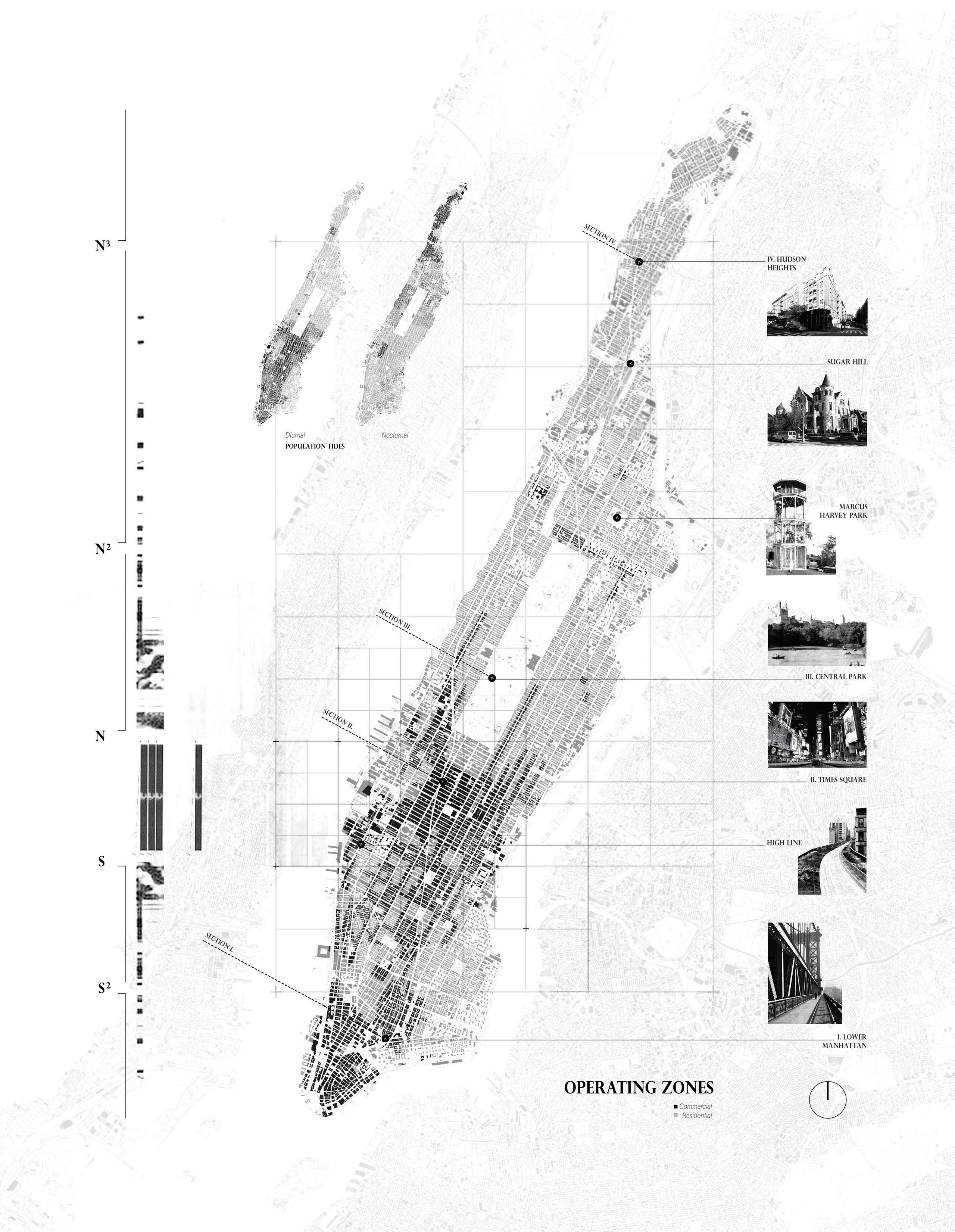

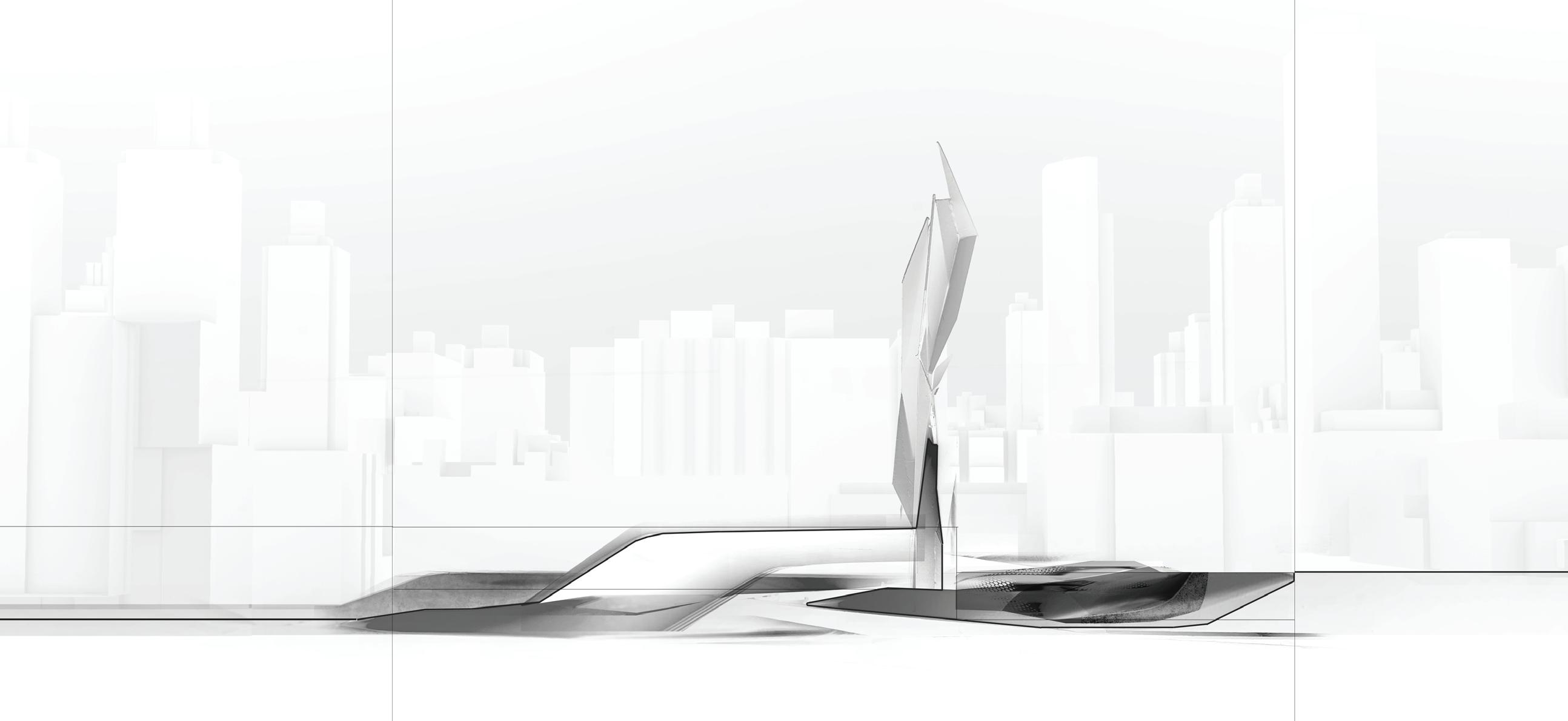

In the study of zoning and population levels in Manhattan, New York evolved the interest of understanding how individuals occupy urban spaces along the city grid throughout diurnal and nocturnal periods of the day. By analyzing how 1. residential and commercial zones are divided, and 2. the population density in those areas, emerges a sense of a “center of gravity” revealed in moments of compression and expansion throughout Manhattan. The concept of “north-ness” is amplified by the division of upper and lower Manhattan, where Times Square is the center point in tying both urban spaces, very distinct in terms of their commercial and residential zonings.

Manhattan is described as a place of “multiple realities and partial comprehensions.” An urban network of infinite perceptions and multiple views, where every change has a ripple effect down throughout the whole city fabric. Inception represents these concepts of perceived and subjective reality, where the city itself becomes a place to live inside fantasy, where the real and natural cease to exist.

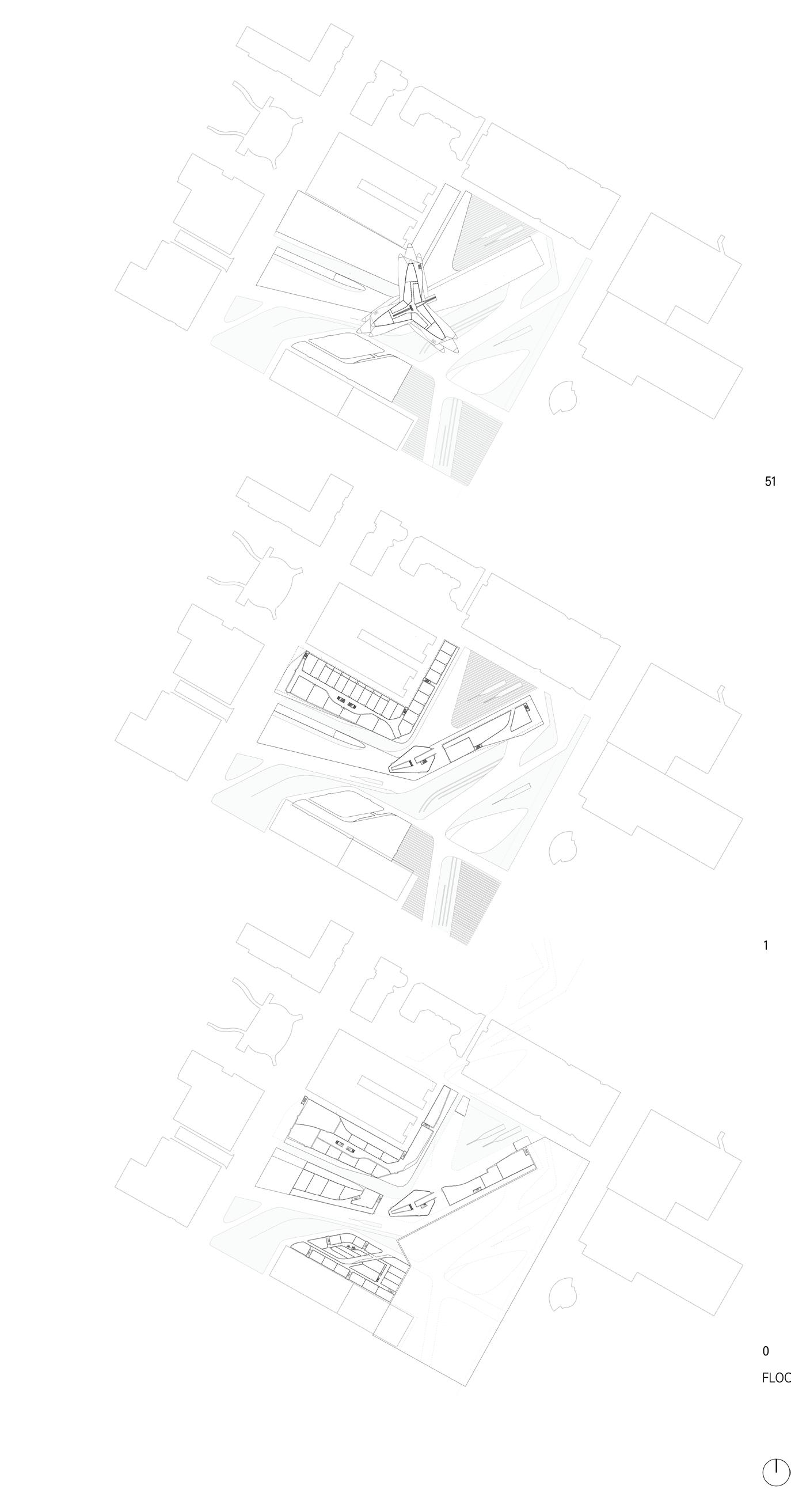

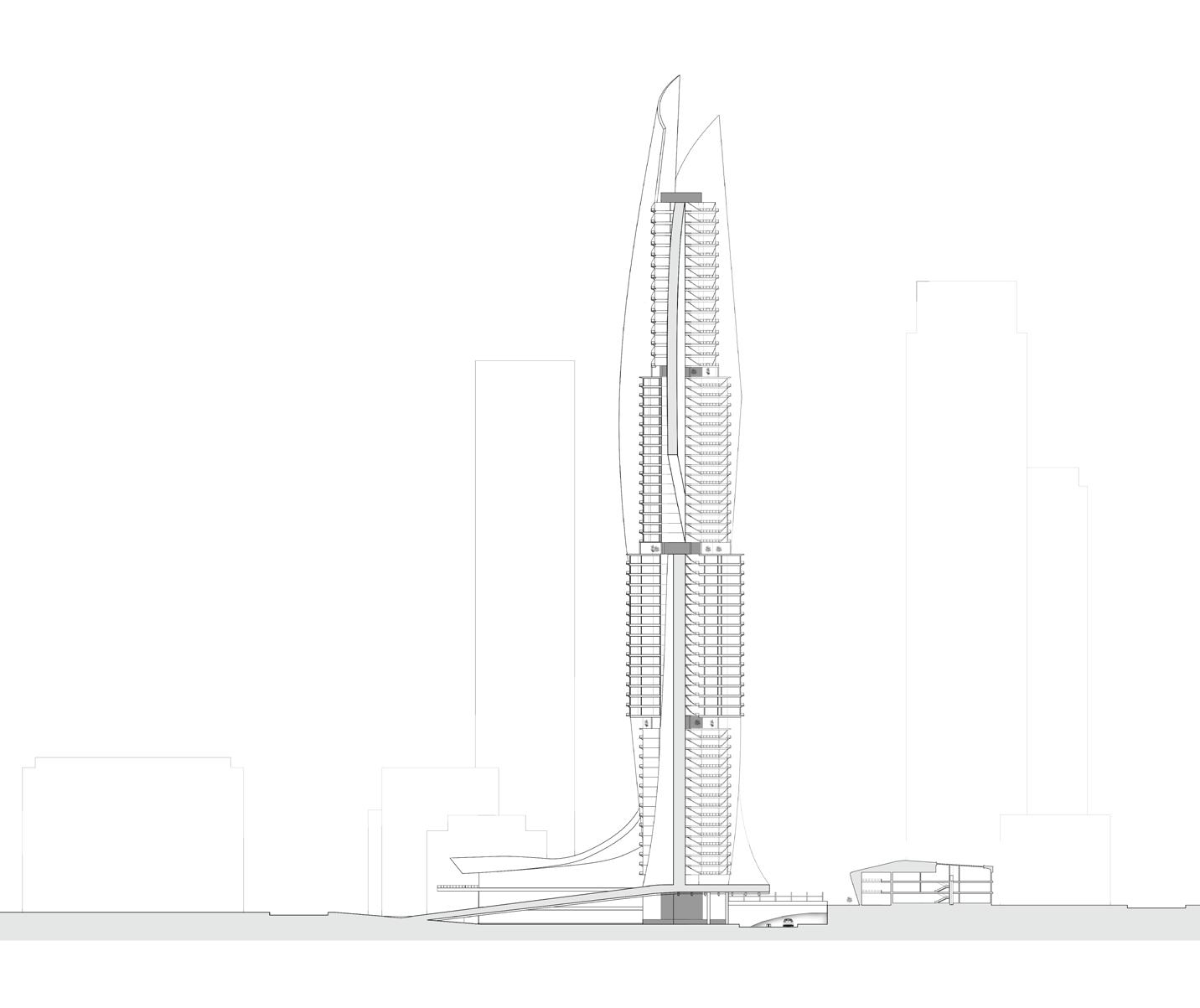

Through analytical study of site and form, the landscape begins to weave into the tower via excavation and manipulation of ground. Interconnectedness is achieved through the integration of housing types, multiple entries, and the merging of housing with urban farming. A flow of horizontal spaces are split yet interconnected into three areas of the site: residential, agricultural, and commercial. Horizontal bars and the tower are allocated for housing and commerce.

The ever-changing culture of Manhattan lends itself to the idea of a space, or series of spaces, that emulate different realities and perspectives. The model photo series experiments with exterior façades and how they would shift the occupants’ experience. By understanding the sun’s movements and shadows casted, the idea of a shifting floor plan that responds to its surroundings allows for a constant dialogue between the space and its environment. Sunlight and shadow begin to inform the character and rhythm of residential and public spaces and how they interact. Together, they influence itinerary and how the occupant can coexist in these spaces.

The floor plans of the tower shift ten degrees counterclockwise every sixteen floors. Every sixteen floors the floor plans are also reduced in size, with the constants being the slit and the stairs/ elevators.Asthefloor plansturnandshrink,thebalconyexperience isalsoshiftingdependingonwhat floor oneison.Thebalconiesshiftindesigntoaccommodateforthesizeandorientationchange.

The urban farm present is a grape vineyard, which is used by the adjacent restaurant and winery. These vineyarwds are sustained by the central slit, or core, of the tower. This enclosed slit lets water flow downward the tower, being collected into water tanks every sixteen floors to be used for plumbing and hydropower for the building and its occupants.

Collected greywater is utilized for the waterfall where it is then collected at ground level in a reflection pool. This pool then moves the water through an underground system where it is then pushed up into the roots of the vineyard with the use of water pumps to sustain the farm. Water is also distributed to the neighboring pond. This urban farming system not only promotes sustainable living but also enhances an urban city experience by making it more intertwined with multiple functions of modern day living.

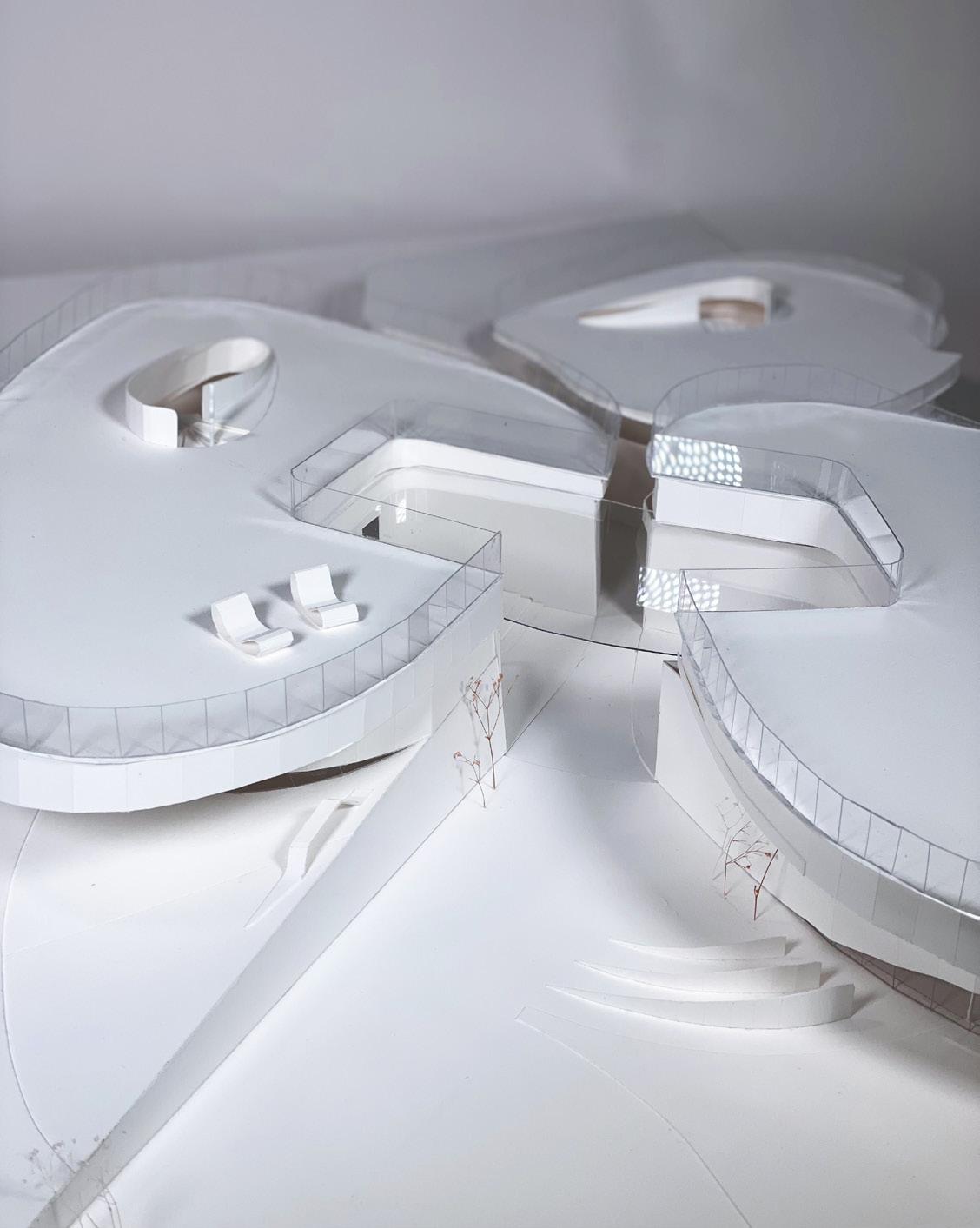

Stemming from the natural composition of a butterfly wing, the plan drawing becomes a canvas for an organic spatial exploration, capturing the essence of the butterfly wing’s layers and translating them into tangible architectural elements. The program of a recreation center serves the purpose to create spaces where people of all ages can connect and interact, with a specific focus on improving the quality of life for the elderly population.

In embracing the intergenerational aspect, the design strives to bridge the gap between age groups, promoting a sense of community and mutual care. The incorporation of play areas for children and spaces for the elderly to engage in activities reinforces the idea of shared experiences. The layout encourages visual connections, allowing children and the elderly to look out for one another, fostering a sense of responsibility and companionship. By intertwining the ideas of play and safety, the design creates a symbiotic relationship between different age demographics.

The intentional design of the recreation center facilitated an overlap between the indoor-outdoor playground for children and the adjacent gardening areas tailored for seniors. This strategic positioning not only encouraged intergenerational interaction but also ensured safety and supervision for both age groups. With clear, unobstructed sightlines between the playground and the gardening spaces, the elderly could observe the children at play from the comfort of their outdoor environment.

This visual connection between generations creates a harmonious atmosphere where both young and old felt connected and valued within the community. By facilitating this mutual visibility, the recreation center promoted not only safety but also meaningful engagement and shared experiences between different age groups.

The proposed library, located in Norwich, Connecticut, takes advantage of its landscape by sitting at the edge of the Yantic Falls waterfall. The library integrates with the existing walkway that spans across the waterfall, making it an integral part of the project’s inception. As visitors step onto the walkway, they are greeted with the view of the cascading water, setting the tone for an immersive library experience integrated into the landscape. This point of entry serves as the initial joint of the project, where users can access the library and embark on a path-finding journey through the meandering spaces.

The intention for these curvilinear forms is to intertwine and peel off from each other, for a play on light filtration and threshold conditions. As light filters through these slits and punctures, it encounters these curved surfaces, creating patterns of light and shadow that dance and transform throughout the day. As the library sits on the edge of Yantic Falls, the presence of water and its natural reflective quality are also inherent to the site. By incorporating reflective surfaces within the space, the design establishes a connection to its surroundings and embraces the qualities of the site itself.

To create a harmonious blend with the natural surroundings, the library branches off from this point of entry into two distinct buildings. These buildings, interconnected by a network of pathways, form the library’s primary spaces. The network of pathways acts as the backbone of the library, introducing multiple routes of circulation throughout the spaces, inviting visitors to meander, discover, and choose their own paths, fostering a sense of exploration and autonomy. The left side of the building serves as a breakout space for more quiet reading or study areas while the right side serves as a commons area where the main library is located. The middle joint that serves as an overhead for the entrance point also has stairs that lead to a small observatory deck to look out into the landscape from a new elevation point.

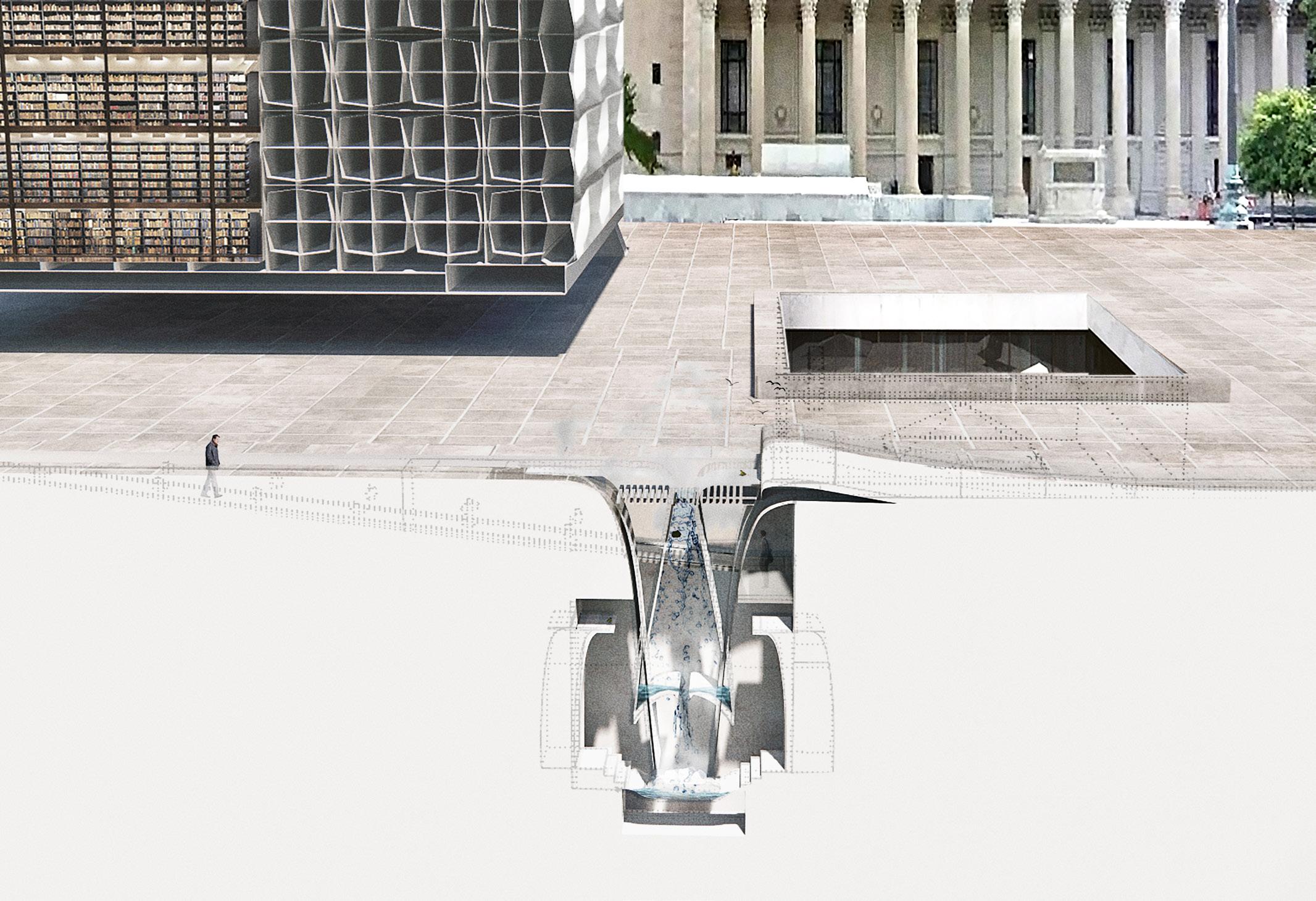

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, located on the campus of Yale University, is characterized by its iconic exterior facade, which consists of thin panels of translucent marble known as “veinless Georgia marble” supported by a grid of bronze mullions. These marble panels filter natural light and regulate the temperature and humidity levels inside the archive, creating an environment for preserving the library’s rare and fragile archival collection.

The architecture of the building itself plays a crucial role in water management. The Beinecke and its surroundings is engineered to withstand potential water ingress, with measures such as waterproofing materials and drainage systems integrated into its design. This ensures that even during inclement weather, the interior remains dry and secure, protecting the rare and fragile collections housed within the library. The new intervention onto the site delves into concepts of water collection, filtration, and the local ecosystem, emphasizing the interconnectedness between built environments and nature.

Inspired by Noguchi’s sunken courtyard, the new intervention manifests as a linear slit in the landscape, leading to an underground “water tower” publicly accessible rather than concealed. Unlike the Beinecke, this design showcases the behind-the-scenes systems, turning them into architectural features. It aims to redefine people’s perception of the water filtration process, transforming it from a mere maintenance task into an architectural marvel. The filtration system doubles as a habitat for birds, with ground-level holes serving as bird dwellings. This not only enhances the area’s natural ecosystem but also contributes to the preservation of the local bird population. In essence, the project offers an immersive way for people to experience water filtration while fostering environmental stewardship.

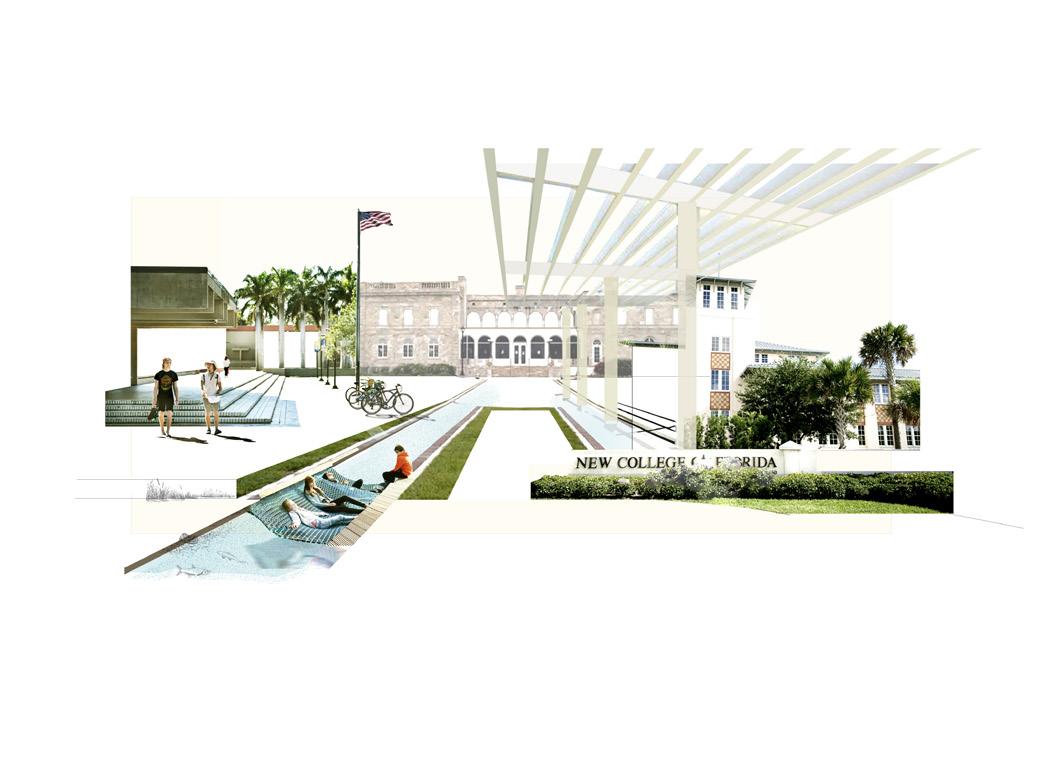

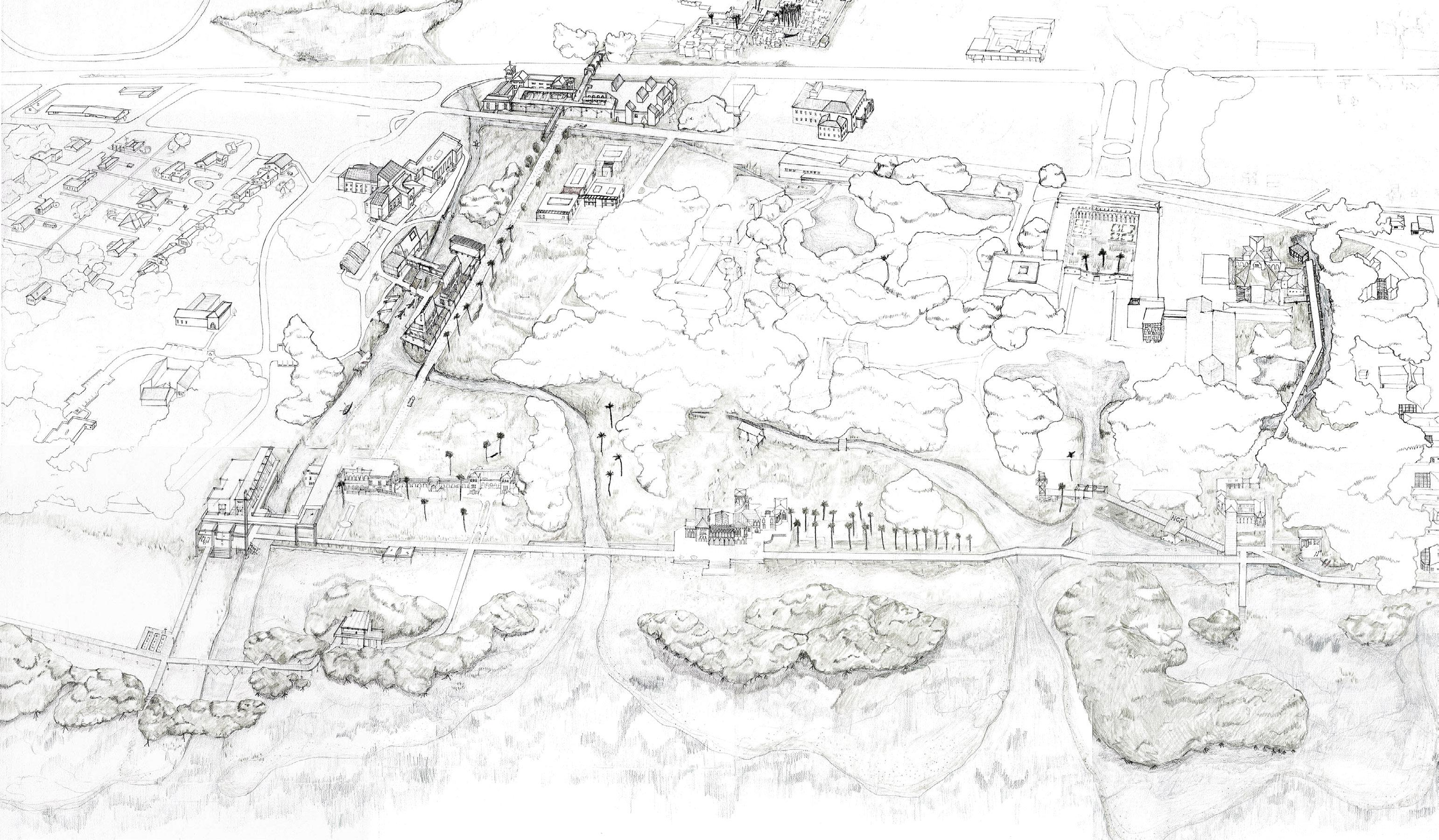

The proposal for the New College of Florida was framed around the issue of coastal resiliency. The main driver are two sides of the same coin- where resiliency would be embodied not just in strategies that protect against storms and heat, but in safeguarding the college’s unique pedagogy.

An analysis of the Gulf Coast began to elucidate the way that Sarasota is connected to its bay. The regional shoreline consists of channels, waterways, and estuaries as well as moments of dredge. What becomes clear is the regularity of intrusions of water into the landscape. This becomes a focal point of future landscape moves that are to break down and soften the seawall, remove top-down, aerially planned pathways with no relation to campus flows, add swales to create inner-campus waterway experiences and give shape to the landscape while creating new pathways to relink existing buildings.

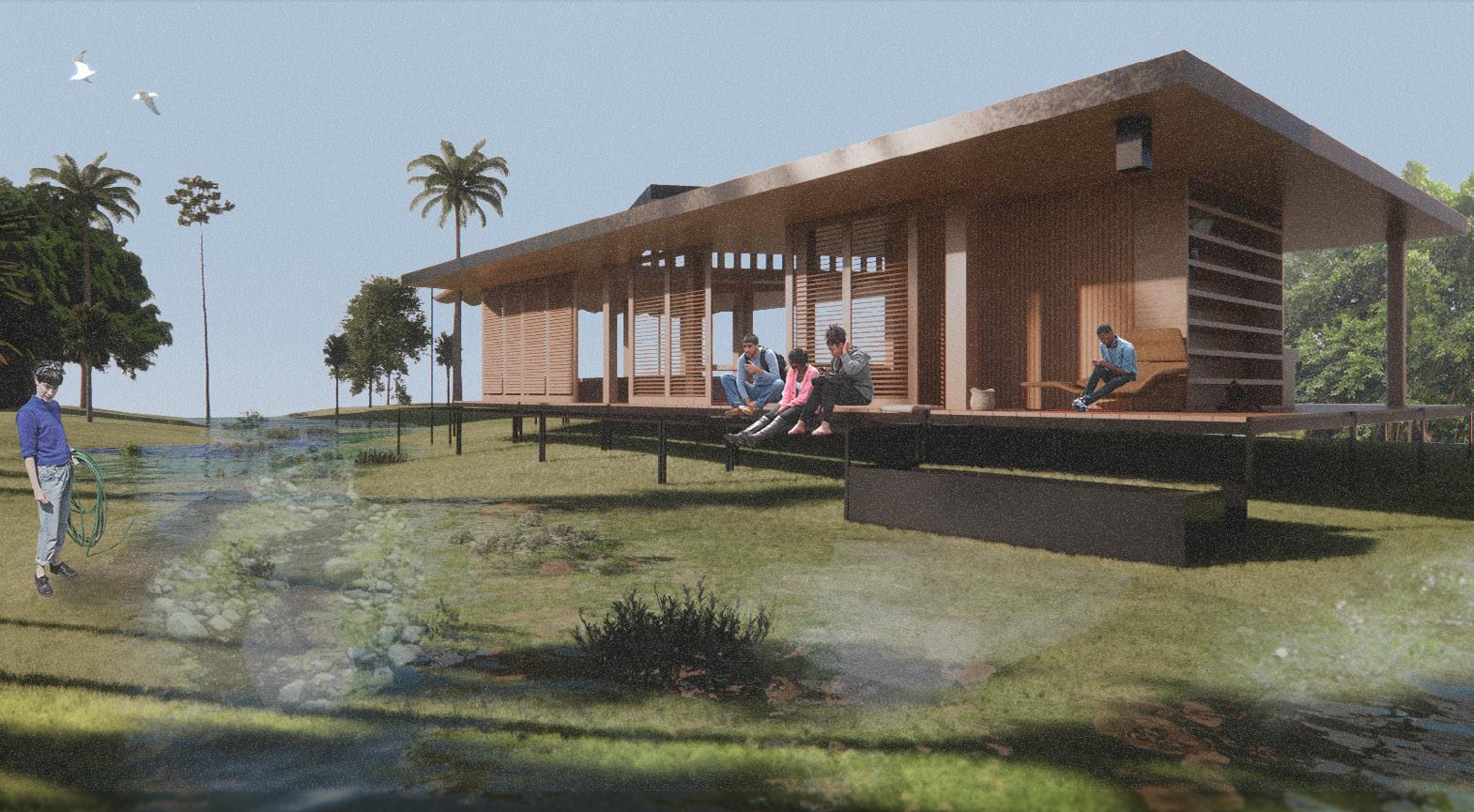

Outdoor classrooms can now be found throughout the campus, interconnected by pathways. These classrooms utilize operable shading devices to create a closer connection with the surrounding bioswales, natural landscape, and ecosystems. These structures not only provide cooler areas but also serve as gathering spots for students. The integration of indoor and outdoor spaces enhances the possibilities for classroom settings. For example, students can visit these natural ecosystems on-site promoting engagement and activating the curriculum, particularly in subjects like natural sciences.

This intervention showcases an application of adaptive reuse, a connecting extension to the already existing Heiser Building. This intervention is a series of overhead canopy structures that provide outdoor shading to enable student migration to these areas. These canopies serve as a breakout into the natural landscape to bridge, or blur, the lines between interior and exterior. Breaking out into the landscape also reorients the building towards the connecting path via the use of operable panel-like “garage” doors.

Referencing the Dogtrot House experience in the design, this becomes a hybrid, transitional space between interior and exterior, providing the flexibility to have a multifunctional space that also facilitates passive ventilation, natural light, and lower energy use and costs.

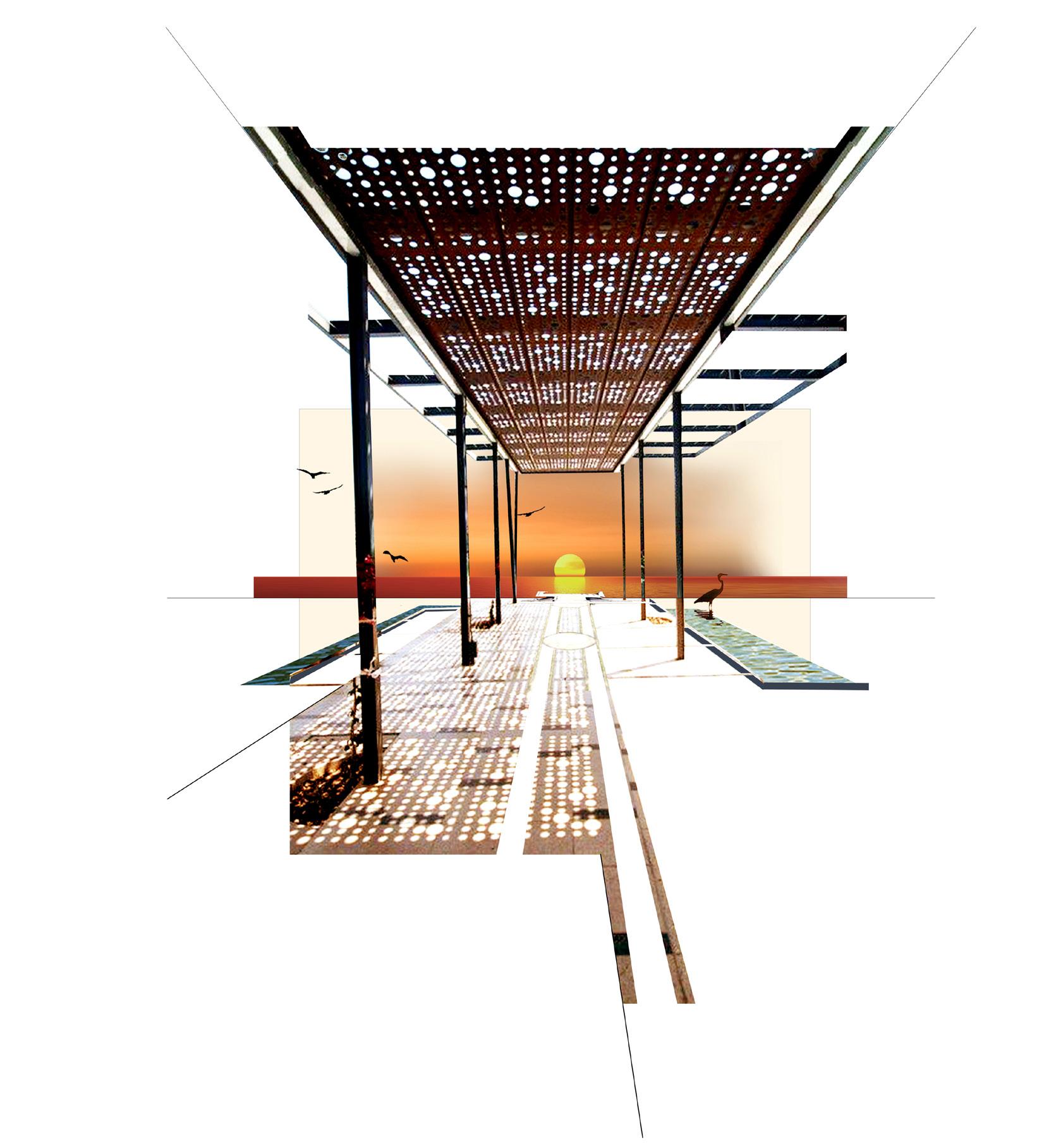

This showcases the transformation of the existing seawall to create a more welcoming and interactive bayfront for students and the community. This transformation involves physically removing the current construction and activating the bay area. The aim is to encourage the growth of new ecosystems, including marine life such as fish, manatees, and plant life like mangroves. To achieve this, subtle architectural interventions are employed, such as the installation of connecting pathways and the introduction of bioswales. Essentially, the bioswales act as natural sponges within the landscape, providing a means to manage excess stormwater while improving water quality.

The dorm design’s emphasis is on creating abundant spaces for intentional interaction and gathering among students. Drawing inspiration from the dogtrot architectural style, shaded and ventilated corridors play a pivotal role in facilitating these opportunities. The dogtrot concept involves a central open-air corridor, often covered, that connects different rooms or spaces. In the context of the dorm design, shaded and ventilated corridors serve as vibrant hubs where students can come together, socialize, and engage in meaningful interactions. These corridors offer comfortable environments for casual conversations, group activities, or even quiet moments of reflection.

The shaded and ventilated corridors offer a respite from the elements, providing a comfortable transition between indoor and outdoor spaces. Students can traverse these corridors to access their rooms or move between different areas of the dormitory while enjoying natural ventilation and protection from the sun.

By creating a layout that fosters intentional interaction and gathering, the dorm design promotes a sense of community and camaraderie among the residents. It encourages students to step out of their comfort zones and actively participate in the vibrant social fabric of the dormitory.

KHORSHID, NOAH SILVESTRY, N’DOS ONOCHIE, OSWALDO CHINCHILLA, & KATIE JIN

The 2022 Jim Vlock First Year Building Project is sited on 164 Plymouth Street, in a residential neighborhood tangent to an active rail transport. This year’s house marks the fifth collaboration with Columbus House, a New Haven-based provider of services to populations dealing with homelessness. This one story, one bedroom home mitigates the sound of the train, responds to climate conditions, maximizes the limited lot size, and ensures a safe and comfortable environment for the residents.

PROFESSOR PETER EISENMAN

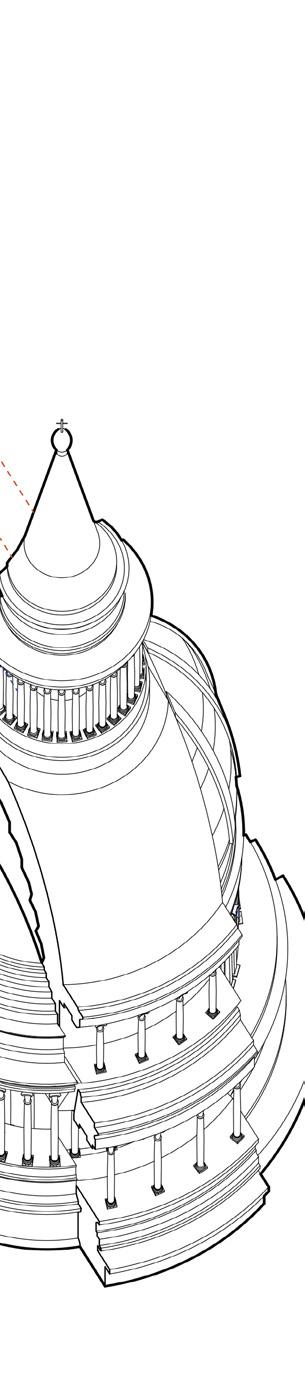

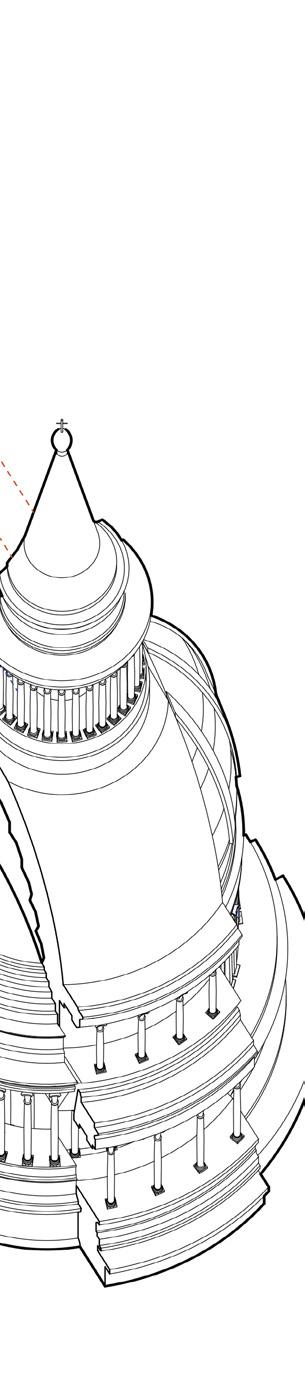

Santa Maria di Monte Santo and Santa Maria del Miracoli are the first impression one receives when entering Vatican City due to the churches being at the sides of the central road

Via del Corso of Piazza del Popolo. Both churches designed by Rainaldi and passed onto Bernini resemble similar architectural styles, with plan revisions by Bernini for Santa Maria di Monte Santo. This difference is notable in their respective plans, where they have different geometries. What at first glance suggests a completely symmetrical exterior facade, actually lies within two distinct plan configurations as well as the interior pediments demonstrated in section.

St. Peter’s dome has been a result of different schools of thought that essentially contribute to the final configuration of the dome. The contributions of Bramante, Sangallo, and Michelangelo (in that order) suggest a shift of dome structure towards one of verticality and a centralized plan. Bramante’s variation is mainly composed of a solid masonry dome that emphasizes a centralized plan. Sangallo’s revision focuses on a double-shelled dome; this hollow structure redefines Bramante’s design from being one of massing to one of lightweight construction. Michelangelo’s final revision reverts back to Bramante’s centralized design, however, Michelangelo proposes a more rational plan.