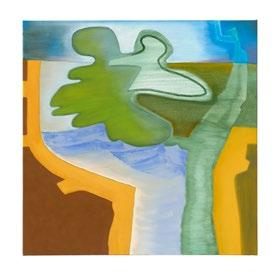

Far Earth Near Tree

Jennifer Amadeo-Holl

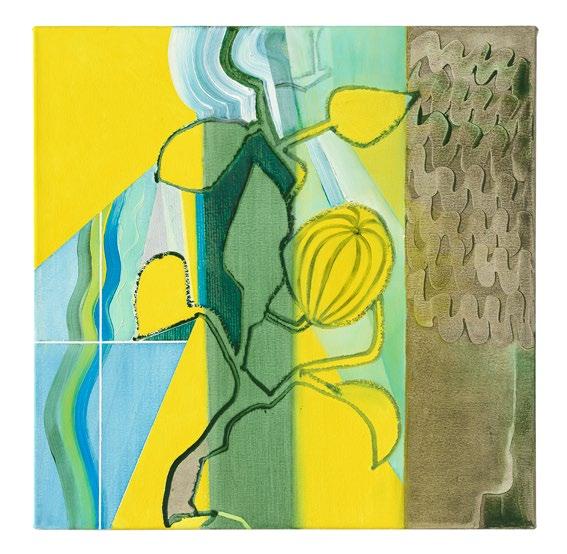

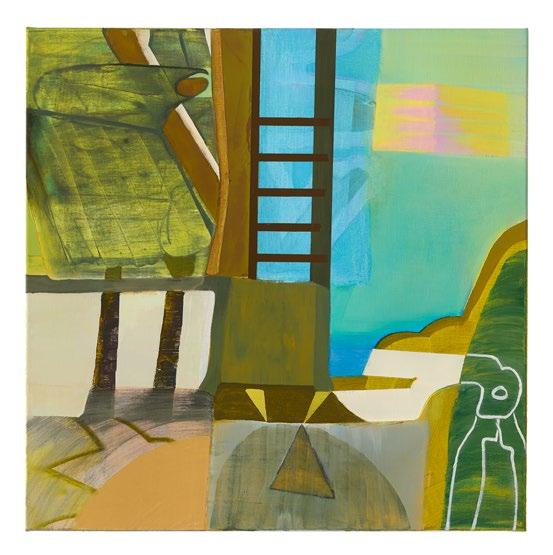

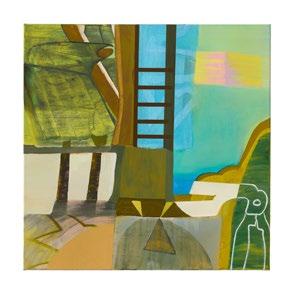

Front Cover, Ancient and New

Jennifer Amadeo-Holl

Front Cover, Ancient and New

Jennifer Amadeo-Holl

Paintings

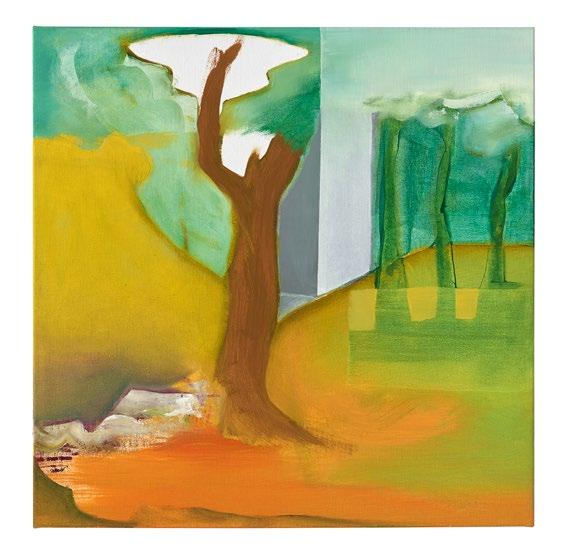

When the earth seems too far, too much to conceive of or protect, too abstract and obscure to see, may there yet be a tree, near, observable, possibly embraceable.

Benjamin Swett is the author of New York City of Trees, which won the 2013 New York City Book Award for Photography. His forthcoming essay collection, The Picture Not Taken: On Life and Photography, will be published by New York Review Books in October 2024. He teaches writing at The City College of New York and is currently the Larry Lederman Photography Fellow at the New York Botanical Garden.

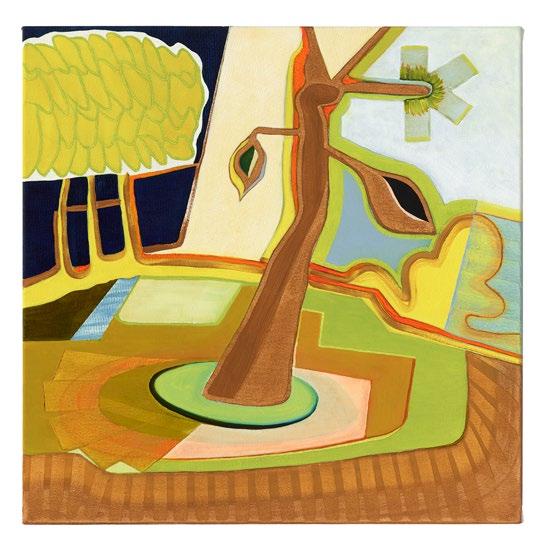

Photosyntheses, detail

Trees in cities are different from those in a forest. They are, among other things, more seen. Constantly on display for those who walk or drive by, or who observe them through apartment windows, city trees possess a heightened presence and character in people's minds. This at any rate was what I found myself thinking when I first began noticing Jennifer Amadeo-Holl's marvelous tree portraits on Instagram—that in each of her bright, surprising squares was captured some aspect of the many lives of a tree in a city as they might unfold, day by day, season by season, in the mind of a caring neighbor. The same tree one might find in the forest or on the shore—but here fully regarded, followed, loved.

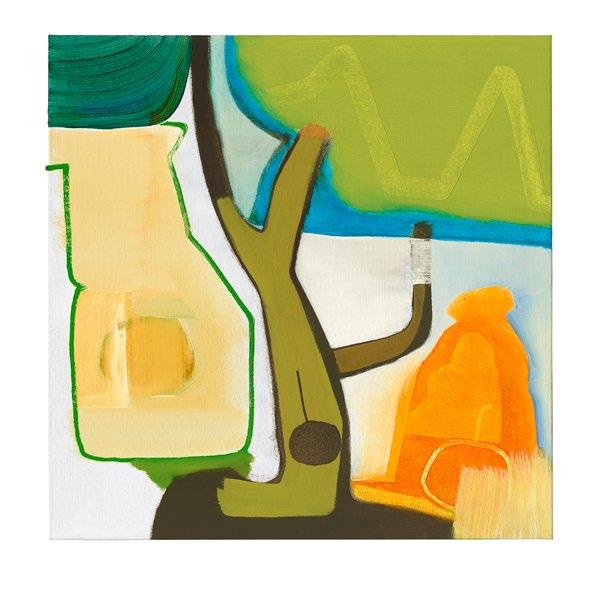

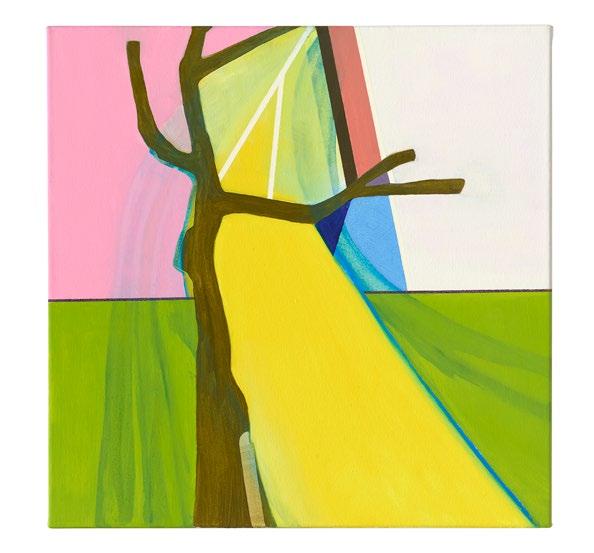

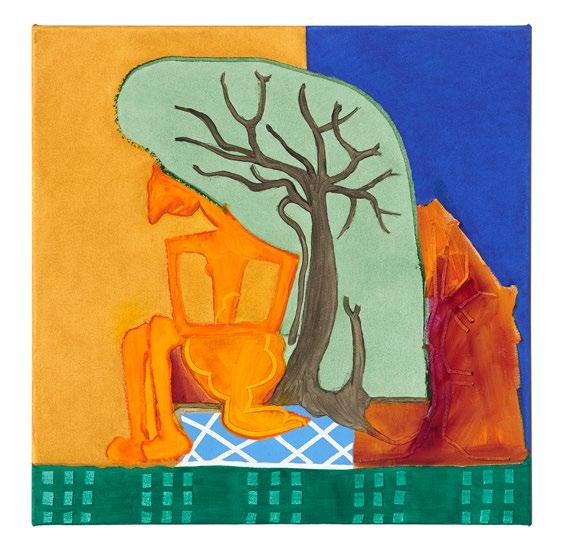

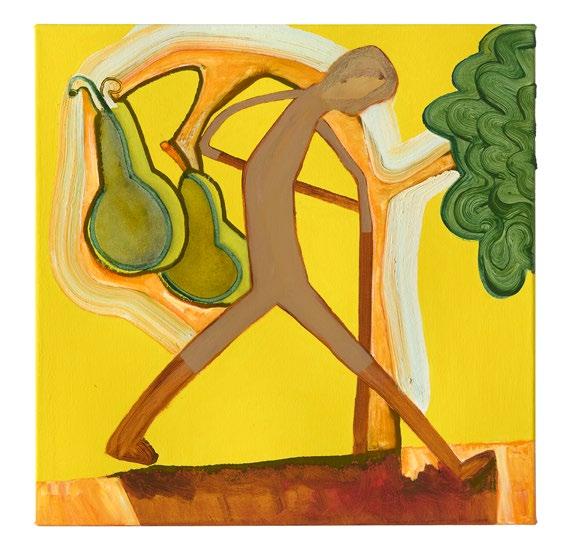

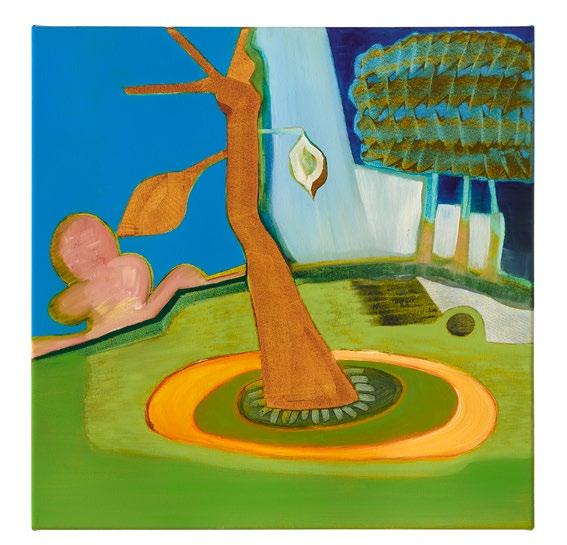

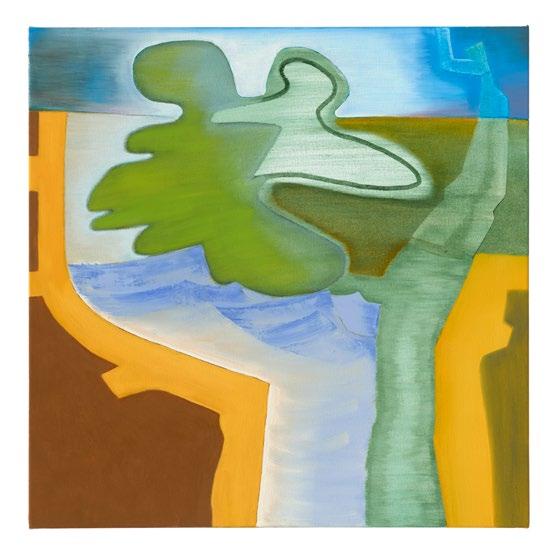

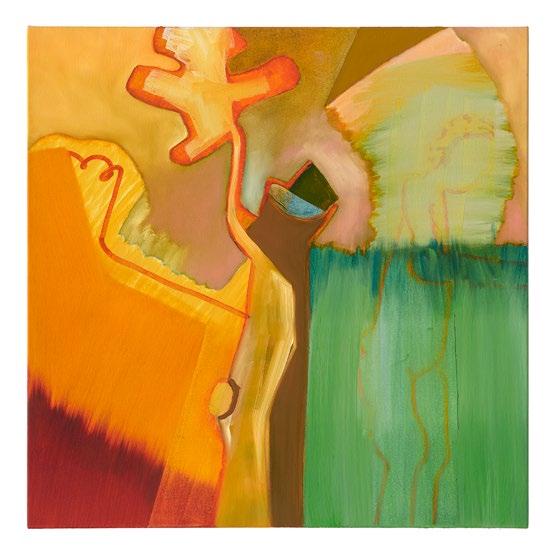

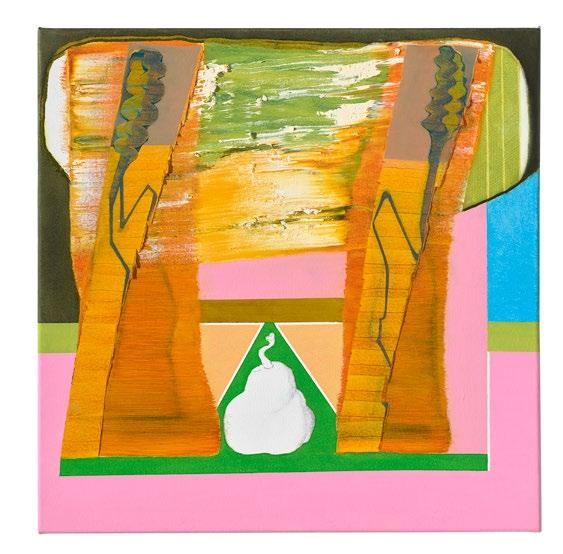

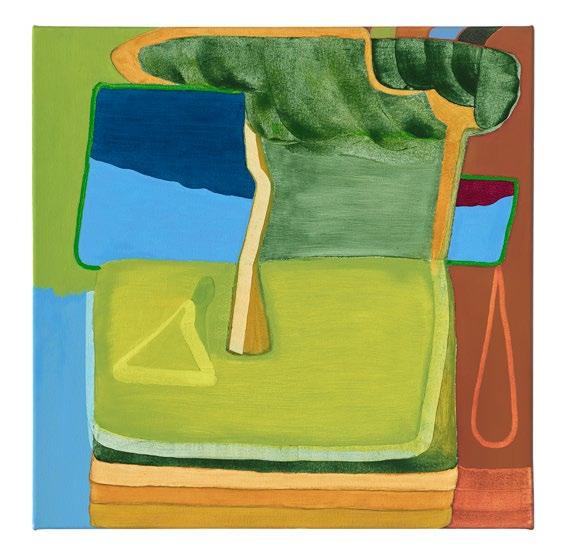

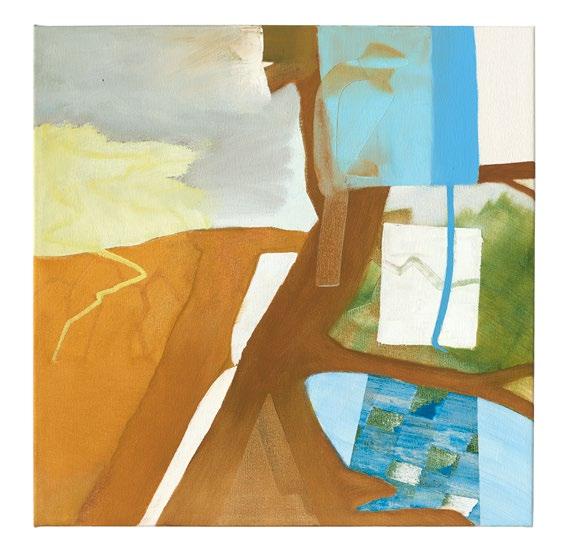

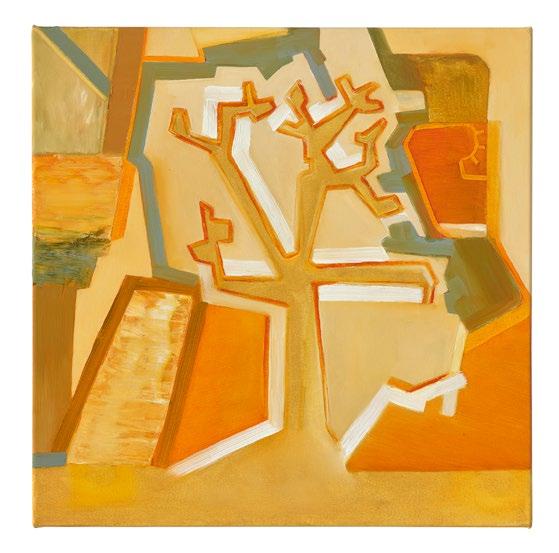

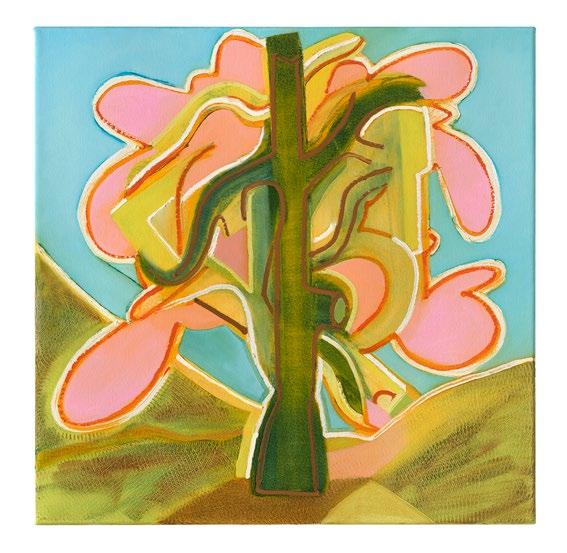

At the center of just about every one of these semi-abstract 24" x 24" paintings is a vertical shape that represents, sometimes overtly and sometimes only by positioning and color, a tree. Around these tree-shapes everything in life seems to happen, cities rise, people stride through, light changes, seasons change, ponds seem to form, conversations happen, landscapes roll away. Light and memories and pathways and clouds and doorways—even other trees and branches—gather around them, each both the calm center and the animating source of movementin the frame.

In their abstraction and particularity, trees store memories and feelings tied to places, and they continue to hold the places together in a person's mind long after they themselves are gone. In the end I think of the trees in these paintings as a single specimen observed over and over again in the many situations in which a tree finds itself—scenes in an ongoing narrative unfolding, for our benefit, in this inventive artist's head.

– Benjamin Swett

Touch activates the senses, expanding space and perception and infilling our experience with light, color, possibility, and an array of personal memories and references.

A life’s story, a life’s study, and a keen observation of art history and contemporary culture. These things accompany Jennifer Amadeo-Holl in her studio, witnessing, informing, and surrounding her as she touches the surfaces of her paintings, as her brushes and tools create innumerable starting points and endless successions of places where light, color, and visual circumstances pierce, rest, and emanate from her touch. In her hands paint slides, color radiates, formal decisions create new ways to see, and time seems to expand into something encompassing.

Why do the circumstances that surround these paintings of trees seem to radiate from her works rather than obscure our view? How does this translation occur?

For many artists the marks and measures of a person’s story are the vehicles that propel them to a space that is necessarily wordless and permeable—where the making happens. Everything is there, from wisdom to neurosis, all rendered speechless by the act of making. With this series Jennifer Amadeo-Holl has filled the shape, temperature, color, sound and motion of this space—with these paintings of trees. Like their subjects these paintings are interconnected, in quiet, persistent communication, considering all things, inclusive, strong, and lasting with an adaptability made from rigor and without judgmentalism.

Amadeo-Holl’s marks and gestures move quickly and slowly, making time the context for each piece. Light pushes her colors to us, even as she flattens some spaces, opens others, divides the canvases with these magnificent, kind subjects to create and solve formal problems.

Trees, the subject, story, and reason for this body of work are at once the main concern of these paintings and the internal dream that makes them alive. Each individual decision the artist has made for us moves, shifts, flattens, defines, activates and consoles, just like the subjects themselves. We watch a group of trees in the summer breeze. Altogether they make a view, a landscape. Individually they move differently, shifting, bending, rustling, moving with the wind and allowing it to move through them.

Jennifer Amadeo-Holl has come to us with an understanding of the history and significance of trees and created a suite of paintings that are also a new set of symbols that we are invited to occupy with our own stories, concerns, and our love for the dream of life.

–Mike Carroll

Mike Carroll lives and works in Truro, Massachusetts, and South Florida. He is the owner and Director of the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown and has been a curator, gallerist, advisor, and producer in the world of fine art for three decades. He was involved in Boston's thriving underground art scene and ran the live performance and Video section at The Boston Film Video Foundation, when video was in its black and white reel to reel infancy. When development displaced the performances held there Carroll opened his first gallery, The 11th Hour near Boston’s South Station. Carroll is a painter represented by the Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown, MA.

Adaptations, detail

These paintings are an inquiry into the puzzles of existence, speaking through trees. The attempt is to express that time feels both quick and deep, love eternal and fleeting, memory firm and faded, and the sublime present and remote. I hope they speak to the varieties of human experience, and find form for something meaningful and magical to another human mind.

Notes about the paintings: Each of these works falls within the canopy of the series Far Earth Near Tree. Each has also an individual title, was painted in oil, is 24 x 24 inches, and was created during the years 2023 and 2024.

Trust in Twig to Limb

Root Crowns and Other Delights

A Natural Home

A Shared Pear

Curious and Good

Coves for Thought

Num Num Nest

The Abney Effect

Geometries of Spring

My roots bridge the island of Puerto Rico and the peninsula of Cape Cod, the one formed by ancient volcanoes and the other nearly afresh by glacial drift. Art played a foundational role in my childhood, as growing up, I was immersed in the company of poets, painters, potters, sculptors, post + beam barn builders, letterpress printers and experimenters in many realms. Painting, drawing, words, and caregiving are my chosen paths to communicate and live this heritage.

I now live in a city, in Boston’s Fort Point Channel district, but grounding my being are ever the landscape and trees of my earlier years: the adaptable Scrub Pine and vulnerable Elm of the Cape, the Yagrumo Hembra and self-pollinating Ceiba of Puerto Rico, sacred to the Taino peoples of the island and central to the Mapuche in Chile, where I painted it along with the Araucania or Pehuen, a tree species so ancient it is sometimes called an animate fossil.

On Cape Cod, I am represented by The Schoolhouse Gallery. Exhibiting with the Schoolhouse holds deep meaning as I grew up knowing many of the artists of Provincetown, and the building itself embodies a good deal of the history and adaptive resiliency of the town and its people. Built in 1844 as the Eastern School House, it served early elementary students for nearly 90 years, but was abandoned in 1931 and stood vacant, wind swept and gathering cod fish flakes and sand.1,2,3

But then…in 1936 the sand was shifted to transform the building into a vital Community Center,4,5,6 and it went on to serve other community uses that spared it being demolished. 1957 began its life in the arts, first as the Provincetown Workshop, and then as the home of Long Point Gallery, an artists’ cooperative founded by, among others, Carmen Cicero and Robert Motherwell. Also located there was a gallery called Rising Tides.

In 1997, Howard G. "David" Davis III purchased and lovingly restored the building and renamed it the Schoolhouse Center, and cast a new tower bell in honor of artist Kevin Driskell, who died of AIDS that year. The Schoolhouse Center is now owned by Lower Cape Communications, which runs WOMR Outermost Community Radio, a nonprofit dedicated to reflecting the rich culture and history of the town. The Schoolhouse Center is one of the few enduring buildings in Provincetown noted by Thoreau in Cape Cod, couched between his 60 descriptions of sand.

Ah sand! In which is imprinted “billions of years of Earth’s history … in the geology of each grain.” 7

“Life begets rock, rocks beget life.” 8 Life begets trees.

Far Earth Near Tree

1. The entire town of Provincetown is a sandspit consisting largely of deposited marine sediment eroded and shifted from farther south.

2. Windblown sand dunes were observed in 1912 by meteorologist Alfred Wegener to be evidence of continental drift. His studies of geologic patterns were published in his 1915 book The Origin of Continents and Oceans, in which Wegener postulated the existence in the late Paleozoic Era of a supercontinent which he called Pangaea. Sourced from page 22.2 of Bentley et al, Historical Geology (VIVA, the Virgina Library Consortium).

3. In Building Provincetown (2010), David W. Dunlap provides a rich and detailed history of this storied building. https://buildingprovincetown.wordpress.com/2010/01/07/492commercial-street

4. As noted in Dunlap’s history, in 1936, the building was converted through the initiative of Professor Charles H. Hapgood and advocacy of Mary Heaton Vorse. Some initially questioned this plan as a radical social experiment but it was eventually supported by the town’s residents, and the Center went on to become the liveliest place in town.

5. Remarkably, vis-à-vis this narrative touching on geology, Professor Hapgood was the author of The Earth’s Shifting Crust, a 1958 scientific volume which denied the theory that continents drift relative to each other over geologic time. After discussions with Albert Einstein concerning geophysics, he republished the book as The Path to the Pole, wherein he proposed that polar wandering accounts for the movement of continents. However, the theory of Plate Tectonics or continental drift was proved in the 1960s. Hapgood followed other erroneous paths in his research into paleoclimatology and ancient civilizations, such as believing the Acámbaro figures uncovered by young-Earth creationist Waldemar Julsrud (and later proved to be fakes) were evidence that dinosaurs coexisted with humans.

6. Mary Heaton Vorse was a labor activist, journalist, author and charter member of the Heterodoxy. In 1942 she published a memoir of her life in Provincetown called Time and the Town. In 2020 resident Ken Fulk saved and restored the Vorse House, putting it at the service of four local arts organizations.

7. Sedimentologist Milo Barham. In Curtin University, “New Technique Unlocks Ancient History of Earth from Grains of Sand,” Phys.org, Earth Sciences, March 1, 2022.

8. Minerologist and astrobiologist Robert M. Hazen. 2023. In Igric Maja Oreskovic, “Extraterrestrial Rocks: Explorations of Speculative Mineralogy,” Astrovitae.com, Issue 5, April: 66.

Acknowledgements:

With gratitude to my beloved family, near and extended, to my dear friends, to my gallerist Mike, to art lovers and makers everywhere, to Siggy and Sugar, may you roam in harmony with the birds along the sandy shores, to my Mother Martha, painter, poet, and unorthodox thinker, whose work is populated by trees, birds and stars, and who made this path visible, and to my Sister Marphy and Father José, long among the trees.

Paintings

©Jennifer Amadeo-Holl

Photograpy

©Julia Featheringill

Design

©Joanne Kaliontzis

Text

©Jennifer Amadeo-Holl

©Mike Carroll

©Benjamin Swett

jenniferamadeoholl.com @jahamadeoholl