A

1

2813-6926 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND DIPLOMACY

ISSN

MARCH 2024

journal of the International Institute in Geneva

Editor:

Claude Cellich, International Institute in Geneva, Switzerland

Associate Editors:

• Daria Dyakonova, International Institute in Geneva, Switzerland

• Carole Sutton, University of Plymouth ,UK

Editorial Review Board Members:

• Mladen Andrlic, Ambassador of Croatia in Hungary, Croatia

• Kip Becker, Boston University, USA

• Shab Hundal, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Finland

• Liu Hong, University of Otago, New Zealand

• Juneyoung Lee, World Trade Organization, Switzerland

• Octavio Peralta, UN Global Compact Network, Philippines

• Ravi Sarathy, Northeastern University, USA

• Ravi Shanker, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, India

• Ludmila Sterbova, University of Economics, Czech Republic

• Nikos Tsourakis, University of Geneva, Switzerland

• Stephen Weiss, York University, Canada

3

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND DIPLOMACY

Volume 1, Number 1

2024

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL PAPERS

Effective Management of Volunteers

Katharina Rehfeld

Culture and International Trade Law: from Conflict to Coordination

Juneyoung Lee

What Factors Influence the Level of Engagement of Individuals in a Banking Relationship in Jordan?

Nawal Tarazi

Setting Educational Objectives for the Book: Machine Learning Techniques for Text

Nikos Tsourakis

A New Data Protection Law in Switzerland. Still the Weakest Privacy Law in Western Europe?

Michael Baltaian

Navigating the Sustainable Energy Transitions Diamond. Strengthening Coherence between the Technological, Economic, Human, Resource, and Governance Dimensions of Sustainable Energy Transitions From a Systems Perspective

Joachim Monkelbaan and Terrence Surles

BOOK REVIEW

Split the Pie: A Radical New Way to Negotiate

Claude Cellich

4

NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS

Papers for publication in future issues of the IIG JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND DIPLOMACY are welcomed. All articles will be peer-reviewed. The following topics should be addressed in future issues of the Journal:

• Cross cultural marketing communications

• Cross cultural business negotiations

• Exporting / Importing

• E-business and digital marketing

• Foreign joint ventures and strategic alliances

• Investment and financial risk management

• Capital markets and corporate finance

• Entrepreneurship and enterprise development strategies

• Global marketing management and strategies

• International trade promotion

• International project management

• Ethics and Sustainability

• International Relations, Security and Diplomacy

• Business analytics and AI

• International Management and Digital innovation

• Risk Management and Strengthening Supply Chains

Contributors should send their manuscripts via e-mail to Editor (ccellich@iig.ch).

Manuscripts should not exceed 20 double spaced pages.

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND DIPLOMACY is published by the International Institute in Geneva, Switzerland.

Copyrights © 2024. All rights reserved.

5

EDITORIAL

To promote research in international business, international relations and diplomacy, and artificial intelligence the International Institute in Geneva has established an in-house publication entitled the Journal of International of Business and Diplomacy. This journal replaces the Institution’s IUG Business Review. The composition of the Editorial Review Board consists of academics and professionals active in their field of expertise. All the articles in the journal have been peer reviewed. The editor and his team are grateful to the faculty and administrative staff for producing the first volume of the journal.

The first article by Katharina Rehfeld explores effective management within non-profit organizations, focusing on the role of motivation and organizational culture. Volunteers driven by intrinsic motivation are vital to NPOs. And managing them requires understanding their motivations while maintaining a balance between guidance and autonomy. The study shows that values and organizational culture play a significant role in motivation.

The second paper by Juneyoung Lee is based on her recent book Culture and International Trade Law: From Conflict to Coordination It addresses the interaction between trade liberalization, cultural protection, and cultural diversity at domestic, regional, and international levels. Based on anthropological elements, the paper conceptualizes culture being utilized in the trade domain. The author proposes a spectrum of cultural products and discusses the nuances and difficulty in defining what classifies as a cultural product in the context of international trade law. Further, it provides a background to UNESCO and culture, assesses economic and other reasons to restrict or enhance trade in culture, analyzes actual culture-related trade policies in selected countries and examines multicultural and preferential trade rules when they intersect with culture. The overall position is that there needs to be a shift from viewing trade and culture “in conflict” to assessing trade and culture “in coordination.”

The third article by Nawal Tarazi studies in an innovative way the factors that influence the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship in Jordan. The research employs a nonprobability sample of 542 individuals to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the individual and social factors that influence the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship. Her findings affirm key independent factors including economic knowledge, age, income, financial literacy, economy, financial technology, and trust affect the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship in Jordan highlighting the gender differences. The author argues that the results can serve as practical guidelines for bank managers, regulators, and policymakers.

The fourth article is timely in view of the latest development in artificial intelligence. Based on his book Machine Learning Techniques for Text: Apply modern techniques with Python for text processing, dimensionality reduction, classification and evaluation, Nikos Tsourakis refers to how the dominant trend in technology is moving towards crafting machines capable of learning from data to perform intelligent tasks. Preparing for this paradigm shift is crucial for individuals and organizations to remain competitive and innovative in the rapidly evolving digital landscape. The book Machine Learning Techniques for Text aims to equip learners with the relevant skills, focusing on text data and human language. The book covers topics like analyzing texts, embarking on machine learning, and effectively utilizing cutting-edge deep learning frameworks for different tasks. Incorporating Anderson and Krathwohl's Taxonomy enables the set of clear learning objectives, preparing students for real-world challenges and permitting measurable learning outcomes. In the article the author provides a summary of the book along with an indicative list of relevant educational goals, learning outcomes, and assessment tasks.

6

The fifth article by Michael Baltaian examines the practical implications of the new law passed on September 1, 2023 for companies doing business in Switzerland. More specifically, the article looks not only at the key components of the new law and how they compare with equivalent law in Europe but also what they mean in practice for companies considering international ones already subject to GDPR and local businesses only operating in Switzerland.

The last article by Joachim Monkelbaan and Terrence Surles highlights why the world needs to shift towards sustainable energy sources and more efficient use of energy. This requires a comprehensive understanding of a set of key determinants. This article sets out these determinants, including economic aspects, technological aspects, resource considerations, and human facets of sustainable energy transitions. The governance that considers proper policies, polity (institutions), and politics needs to enable these four sometimes synergistic but often conflicting dimensions. The article lays out these dimensions and their intersections and presents them in the form of the ‘Sustainable Energy Transitions (SET) Diamond’.

On behalf of the Editorial Review Board, I take this opportunity to thank everyone for their contribution to this first volume with their knowledge, expertise and above all for their precious time. I look forward to future issues of the Journal with articles addressing the need to improve sustainability of businesses operating in a disruptive environment due to geopolitical conflicts, digital transformation and increasing global competition.

The Editor

7

Effective Management of Volunteers

The role of motivation and organizational culture

Katharina-Maria Rehfeld 1

Abstract

This article explores effective management of volunteers within non-profit organizations (NPOs), focusing on the role of motivation and organizational culture. Volunteers are vital to NPOs, driven by intrinsic motivation, and managing them requires understanding their motivations while maintaining a delicate balance between guidance and autonomy. Studies show that values and organizational culture play a significant role, while the organizational values must be aligned with the personal values of the volunteers. The article illustrates crucial aspects by providing information on voluntary work in Switzerland.

Keywords: sustainable leadership, non-profit organization, commitment, organizational culture

NPOs play a pivotal role in both the economy and the well-being of society. They heavily rely on volunteers who contribute their time and effort voluntarily, driven by a strong intrinsic motivation rather than financial gain. Managing and leading volunteers, however, presents a unique challenge due to the delicate balance between guidance and preserving their autonomy. To harness the full potential of volunteers and ensure their sustained support, it is crucial for those in leadership positions to understand their motivations to guide and manage them effectively and sustainably.

Against this background, the article highlights the peculiarities of managing volunteers by exploring the role of the values and culture of the organization to ensure its existence. Statistics and information about volunteers in Switzerland are provided as an example to illustrate its relevance further.

In Switzerland, the extent of volunteer work is considerable: in 2020, around 1.2 million people carried out unpaid work within organizations, clubs, or public institutions and 2.3 million took on informal unpaid activities such as neighbourhood help, childcare, services, or care and caring for relatives and acquaintances who do not live in the same household. Volunteers invest an average of 4.1 hours per week in this commitment (Federal Statistical Office Switzerland, 2021).

Researchers have highlighted sustainable leadership as a critical success factor for NPOs (Froelich/McKee/Rathge, 2011, p. 3). Sustainable leadership, particularly concerning volunteers, focuses on maintaining their performance and long-term commitment without offering monetary compensation (Kanning 2013, p. 25). Given the extensive literature on the impact of pay structures on employee performance and commitment, managing unpaid volunteers in NPOs necessitates alternative management approaches (Redmann 2018, p. 72).

8

1 Katharina-Maria Rehfeld is Professor in Human Resource Management at IU International University of Applied Science and Adjunct Professor, International Institute in Geneva

Volunteer work is not free of expectations; it operates on the principle of reciprocity. Volunteers donate their time with the expectation that their motives or needs associated with philanthropy will be indirectly satisfied by the organization (von Schnurbein 2008).

Effective leadership in NPOs requires an understanding of volunteers' motives to align their behavior with the organization's goals. Sustainable leadership entails adopting a "motivationally compatible leadership behavior" (Krönes 2016, p. 10), tailored to individual volunteers' needs and motives.

Motives for Volunteering

The discussion on egoism and altruism has significantly influenced research on voluntary engagement for a long time (Cialdini et al., 1987; Schie et al., 2015). Reasons for voluntary engagement have been categorized into egoistic (self-centered) and altruistic (concerned with the well-being of others) reasons. In 1998, Clary and colleagues (Clary et al., 1998) introduced a functional approach that emphasizes the versatility of engagement, overcoming the previous debate on egoistic and altruistic motivations for involvement. They applied the question of the functional approach, which examines the functions and significance of attitudes for individuals, to the realm of voluntary engagement. They inquire into the psychological functions underlying volunteer work, suggesting that engagement can simultaneously serve different purposes for different individuals. Clary et al. (1998, p. 1,518) identify six generally relevant motives for voluntary engagement serving different functions or purposes (Houle et al. 2005, p. 338):

1. Value Motive: This motive is all about having a strong sense of wanting to do good for others and make a positive impact on the world. People with a value motive volunteer because they believe in helping those in need and making their communities or the world a better place. It's driven by a deep sense of humanitarianism and altruism, where the satisfaction comes from knowing they've made a difference in someone else's life.

2. Knowledge Motive: Those with a knowledge motive are motivated by the opportunity to learn and grow. They see volunteering as a chance to gain new insights, acquire new skills, and expand their horizons. These volunteers are often focused on personal development and self-improvement. They find fulfilment in acquiring knowledge and developing expertise in various areas through their volunteer experiences.

3. Career Motive: Some volunteers are driven by the desire to advance their careers or secure gainful employment in the future. They see volunteering as a means to build their resume, gain valuable work experience, and develop skills that can enhance their job prospects. This motive is especially common among young people and those looking to transition into a new career field.

4. Social Motive: People with a social motive are primarily interested in building connections and expanding their social networks. They view volunteering as an opportunity to meet like-minded individuals, make friends, and connect with others who share their interests and values. The social aspect of volunteering is what motivates them the most.

5. Protection Motive: The protection motive involves using volunteer work as a way to cope with personal issues or challenges. It can be a means of distraction or escape from problems in their own lives. Volunteering allows them to focus their energy and attention on helping others, which can provide a sense of relief from personal difficulties.

9

6. Self-Esteem Motive: Volunteers with a self-esteem motive are driven by the positive feelings and self-confidence that come from helping others. They find a sense of selfworth and accomplishment in their voluntary actions. Being recognized and appreciated by others for their contributions further boosts their self-esteem. It's about feeling good about themselves and their ability to make a difference.

After examining numerous studies through this framework, Chacón et al. (2017) discovered that the predominant driver for volunteering is the values dimension, while career and enhancement motivations are less common. The inclination towards career and understanding motivations tends to decrease with the average age of volunteers, and it appears that men are more inclined towards considering the social dimension compared to women.

In Switzerland, most volunteers get involved because they enjoy the activity. For many people, social aspects are also important: thanks to their commitment, volunteers come together with other people and can work together to move something. Other motives that are mentioned often are expanding own knowledge and experiences, giving something back to other people, developing personally and growing personal network. External pressures and obligations rarely play a role. In informal volunteer work, the most important motive is often to help: Three quarters (76%) is committed to helping others. There is no major difference in the motives of women and men (Federal Statistical Office Switzerland 2021).

The managing director of the Ilgenau village for disabled people in Ramsen, Switzerland, highlights the significance of these motives in volunteerism. Many volunteers are driven by a desire to give back, stemming from personal experiences or gratitude for their current circumstances. Younger volunteers, in particular, value networking opportunities, training, and skill development, often becoming experts in their fields through focused further training.

Effective leadership of volunteers relies on aligning their personal motivations with the fulfillment provided by volunteer activities (Stukas et al., 2009, p. 80). Despite the continued dependence of nonprofit and public organizations on volunteer support, determining the factors that drive individuals to volunteer and sustain their commitment over time remains a complex challenge. The Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI) serves as a practical tool that has demonstrated its efficacy in engaging volunteers. Utilizing resources like the VFI questionnaire enables the evaluation of volunteers' motivations, allowing for the customization of their roles to enhance both performance and commitment. Research not only supports the effectiveness of this approach but also validates its utility in designing training manuals for volunteer organizations and improving recruitment and retention practices. Organizations are encouraged to foster and capitalize on these motivations through shared reflection, as proposed by Clary and Snyder (2002).

Organizational Values and Culture

Besides understanding volunteers' individual motivations, an organization's culture and its values play a significant role. Organizational culture has gained importance in recent years in how it influences external perceptions and cooperation within NPOs. It can determine whether volunteers are interested in working with the organization and whether they commit for the long term. A strong, trust-based organizational culture that aligns with and nurtures volunteers'

10

intrinsic motivation becomes a crucial factor in the success or failure of NPOs. Duke (2012) conducted a study that showed a positive relationship between organizational culture and nongovernmental organizations (NGO) performance. A suitable organizational culture can have a positive impact on an organization's effectiveness and its ability to achieve its desired outcomes. Similarly, organizational culture can help prevent negative actions and scandals (Vijfeijken, 2019).

However, there has been limited research on shaping organizational culture in NPOs and how values guide and influence the behaviors of leaders, helpers, and members. Previous studies on organizational culture have largely focused on for-profit organizations. This is partly because NPOs often assume that their organizational culture is naturally shaped by their mission, vision, goals, and their distinction from the business sector. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clear that the interests and values of NPOs, in pursuit of their missions, may not always align with a social and value-oriented organizational culture (Vijfeijken, 2019). This misalignment could diverge from the values held by volunteers.

Martin and Siehl (1983) describe organizational culture as "the cement that holds an organization together through shared patterns of meaning consisting of core values, forms, and strategies to reinforce content." Edgar Schein (1985) also highlights the role of employee values in organizational culture. Schein suggests that employees' values strongly influence organizational culture, meaning that an organization's culture reflects the fundamental values of its team, which, in turn, influence how people behave within the organization (Türk 1976, p. 68). This shared value base serves an identification function (Arnett et al. 2003). NPOs attract volunteers and members who identify with the organization's mission and share its values. To retain volunteers over the long term, it's crucial to assess early in the recruitment process whether a person's individual values align with the organizational culture's values (Weinert 2004, p. 171). Only when these values are in line with a person will they feel comfortable and remain committed to the organization.

Freiermuth (2022/2023, p. 8) points out that the self-perception of formally engaged volunteers has evolved in recent years: they have become more self-assured, viewing themselves as contributors who bring their personal talents and want to have a say, expecting communication on an equal footing. Nowadays, individuals who dedicate themselves to a club or institution not only aim to contribute to a good cause but also approach an organizing entity with specific needs. To retain volunteers, organizations must be aware of and consider these needs, as the options are vast, and volunteers can choose whom they work with.

In the competition for the resource of volunteers, favorable conditions are crucial. The foundation for this is professional volunteer management, aiming to optimize volunteer activities for all involved. It involves aligning the desires and needs of volunteers with the requirements institutions place on them. Volunteer management also ensures that collaboration with volunteers is part of the organizational culture and embedded in the overall strategy. It is crucial that volunteers are familiar with and can identify with the goals and values of the organization.

The integration of volunteers succeeds only when accepted and supported by paid staff. Paid employees should be involved early on, and any reservations and fears should be taken seriously. Otherwise, friction points may arise within an organization, complicating the collaboration between paid and volunteer personnel.

Focusing too much on motivating volunteers can create a conflict-avoidant atmosphere in the long run. For instance, if volunteers who are less motivated are overly protected due to a

11

misinterpretation of employee orientation, it can place additional burdens on paid employees and demotivate them (Simsa 2019, p. 272). This situation can lead to pronounced swings between extremes: too much autonomy followed by centralized control, which can negatively affect volunteers' intrinsic motivation (Simsa 2019, p. 374). Dealing with this leadership dilemma of "either-or," it is advisable to adopt a consistent "both-and" approach. These dilemmas and contradictions specific to NPOs require leaders to have a high tolerance for ambiguity. Leaders must balance divergent interests and expectations of different employee groups while also serving as symbolic role models within the organization. As a result, effective leadership is increasingly recognized as a critical success factor for NGOs in sustainability discussions. It is emphasized that volunteer work is not meant to replace paid work but rather complement and support it. Therefore, the roles, tasks, competencies, and obligations of volunteers and paid staff must be clearly defined and delineated.

The Swiss Red Cross (SRC) Aargau is one of the 24 cantonal branches of the national Red Cross society. As an autonomous association within the SRC group, they are financially and organizationally independent. About 1,000 volunteers are engaged in relief and social integration. According to Silvana Lindt, the specialist in volunteer management at the SRC Aargau, the paid staff experiences collaboration with volunteers as a crucial enrichment in their daily work. "Our employees appreciate the volunteers a lot, and the volunteers reciprocate that appreciation. It's a very positive collaboration for all parties involved. We motivate each other" says Lindt (Freiermuth 2022/2023, p. 8).

Conclusion and Outlook

In conclusion, this paper has delved into the critical aspects of retaining volunteers by comprehending their motivations, emphasizing the significance of organizational culture and values. Despite the third sector's substantial role in society and its contribution to essential tasks, it remains an area that lacks extensive research, particularly in terms of employee management. Recognizing its social and macroeconomic importance, there exists a pressing need to bridge this research gap through empirical studies, thereby ensuring the sustainability of leadership. This empirical approach is crucial for cultivating evidence-based strategies aimed at maintaining the long-term commitment of volunteers.

Furthermore, it is essential to underline that volunteer work is a voluntary endeavor, contrary to mandated involvement. It can never be demanded but should be requested and fostered. While forms of obligatory engagement have their place in various sectors of society, they do not fall under the purview of volunteer work.

Sustainable collaboration with volunteers should be ingrained in the organizational culture, with decisions regarding volunteer engagement made at the leadership level. Adequate resources must be allocated, and the legitimate fears and reservations of paid staff should be acknowledged and addressed. Without the understanding and acceptance of the paid staff, the successful organization of volunteer efforts becomes challenging.

In summary, volunteer work and paid employment are not in competition; rather, they serve different purposes. Services of immediate and vital importance to individuals and the environment should be carried out through paid work, while volunteer work significantly contributes to enhancing the quality of life, fostering human interaction, and championing environmental protection. Balancing these aspects is fundamental for effective leadership in volunteer management.

12

References

Arnett, D.B., German, S.D. and Hunt, S.D. (2003). 'The identity salience Model of relationship Marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing,' Journal of Marketing, 67(2), pp. 89–105. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.89.18614.

Chacón, F., Gutiérrez, G. and Sauto, V. (2017). ‘Volunteer Functions Inventory: A systematic review. Psicothema,’ 29 (3), pp. 306–316.

Cialdini, R.B. et al. (1987). ‘Empathy-based helping: Is it selflessly or selfishly motivated?,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), pp. 749–758.

Clary, E. G., and Snyder, M. (2002). ‘Community involvement: Opportunities and challenges in socializing adults to participate in society,’ Journal of Social Issues, 58, pp. 581–591.

Clary, E. G. et al. (1998). ‘Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), pp. 1516–1530.

Duke II, J. (2012). ‘Organizational Culture as a Determinant of Non-Governmental Organization Performance: Primer Evidence from Nigeria,’ International Business and Management, 4, pp. 66-75.

Federal Statistical Office Switzerland (2021). Freiwilliges Engagement in der Schweiz 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/news/de/2021-0625

Freiermuth, K. (2022/2023). ‘Mit Freiwilligen zusammenarbeiten,’ Der HR-Profi Newsletter 01 Dezember 2022/Januar 2023, Weka Business Media, pp. 8-9.

Froelich, K.A., McKee, G.J. and Rathge, R.W. (2011). ‘Succession planning in nonprofit organizations,’ Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(1), pp. 3–20. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.20037.

Houle, B. J., Sagarin, B. J., and Kaplan, M. F. (2005). ‘A functional approach to volunteerism: Do volunteer motives predict task preference?’ Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 27(4), pp. 337– 344.

Kanning, H (2013). ‘Nachhaltige Entwicklung – Die gesellschaftliche Herausforderung für das 21. Jahrhundert,’ in: Baumast, A. and Paper, J. (eds) `Betriebliches Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement,` Stuttgart, pp. 21-43.

Krönes, G. (2016). ‘Motivation nutzen – Nachhaltiges Personalmanagement Ehrenamtlicher,’ Weingartener Arbeitspapiere zur Allgemeinen Betriebswirtschaftslehre, zum Personalmanagement und Nonprofit-Management, Nr. 12.

Lamprecht, M., Fischer, A. and Stamm, H. (2020). ‘Freiwilligenmonitor Schweiz 2020,’ Retrieved from: https://www.seismoverlag.ch/site/assets/files/16190/oa_9783037777336.pdf

Martin, J., and Siehl, C. (1983). ‘Organizational culture and counterculture: An uneasy symbiosis,’ Organizational Dynamics, 12(2), pp. 52–64.

Van Schie, S., Güntert, S.T., Oostlander, J. and Wehner, T., 2015. “How the organizational context impacts volunteers: A differentiated perspective on self-determined motivation.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, pp.1570-1590.

13

Redmann, B. (2018). ‘Erfolgreich führen im Ehrenamt: Ein Praxisleitfaden für freiwillig engagierte Menschen,’ Springer Gabler.

Schein, E. H. (1985). ‘Organizational culture and leadership: A dynamic view,’ Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Schnurbein, G. v. (2008). ‘Nonprofit Governance in Verbänden: Theorie und Umsetzung am Beispiel von Schweizer Wirtschaftsverbänden,’ Haupt Verlag.

Simsa, R. (2019). ‘Leadership in Organisationen sozialer Bewegungen: Kollektive Refexion und Regeln als Basis für Selbststeuerung. Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation,’ in: Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie, 50, pp. 291–297.

Stukas, A. A. et al. (2009). ‘The matching of motivations to affordances in the volunteer environment: An index for assessing the impact of multiple matches on volunteer outcomes’ Nonproft and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, pp. 5–28.

Türk, K. (1976). ‘Grundlagen einer Pathologie der Organisation: 60 Einsichten,’ Enke Sozialwissenschaften.

Vijfeijken, T.B.-V. (2019). ‘“Culture is what you see when compliance is not in the room”: Organizational culture as an explanatory factor in analyzing recent INGO scandals,’ Nonprofit Policy Forum, 10(4).

Wehner, T. et al. (2015). ‘Frei-gemeinnützige Tätigkeit: Freiwilligenarbeit als Forschungs- und Gestaltungsfeld der Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie,’ in: Wehner, T. and Güntert, S. (eds) ‘Psychologie der Freiwilligenarbeit,’ Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, p. 3-22.

Weinert, A. B. (2004). ‘Organisations- und Personalpsychologie,’ Beltz Verlag

14

15

Culture and International Trade Law: from Conflict to Coordination 1

Juneyoung Lee 2

Abstract

This work addresses the interaction between trade liberalization, cultural protection, and cultural diversity at domestic, regional, and international levels. Based on anthropological elements, the work conceptualizes culture being utilized in the trade domain. It proposes a spectrum of cultural products and discusses the nuances and difficulty in defining what classifies as a cultural product in the context of international trade law. Further, the work: (i) provides a background to UNESCO and culture; (ii) assesses economic and other reasons to restrict or enhance trade in culture; (iii) analyzes actual culture-related trade policies in a cross-section of countries; and (iv) examines multilateral and preferential trade rules when they intersect with culture. The overall position is that there needs to be a shift from viewing trade and culture "in conflict" to assessing the two subjects "in coordination".

Keywords: trade, culture, trade policies, cultural policies, cultural identity, cultural diversity, protectionism, conflict, and coordination

1. The Research Question and This Publication's Approach

How can policies on trade and culture be coordinated in such a way that both are enabled to flourish? This question is at the heart of this publication.

It is not only a philosophical but also a practical, legal, and policy-oriented question that decisionmakers face in trade negotiations and trade disputes. The latest bilateral trade negotiations between the European Union and the United States explicitly underscore the challenges of untangling the issue of trade and culture. Even before officially launching these Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations, some European countries claimed the cultural and audiovisual services should be excluded from the negotiating mandate.

Furthermore, the China-Audiovisuals case shows that the World Trade Organization (WTO) cannot avoid considering its role in the trade and culture debate much longer. The basis for such considerations can be found outside the WTO, and mainly in the developments around the 2005 UNESCO Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. One can, however, question the influence the 2005 Convention has had on legal and political considerations of trade and culture.

Governments have been struggling with striking a balance between the protection of culture and the liberalization of trade based on differing domestic policy priorities for decades. Before placing this discussion in the context of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) / WTO and UNESCO in the 1930s, the League of Nations adopted the 1933 Convention for Facilitating the International Circulation of Films of an Educational Character. The contracting parties of the Convention believed that “the international circulation of educational films is

1 The article is based on a recent book: Juneyoung Lee (2023). Culture and International Trade Law: From Conflict to Coordination, Leiden and Boston, Brill.

2 Juneyoung Lee is a Legal Affairs Officer at the World Trade Organization and Adjunct Professor at the International Institute in Geneva

16

desirable for the mutual understanding of people, and it will consequently encourage moral disarmament.” Aiming at achieving this belief, the Convention exempted educational films from import duties, but this was discontinued with the outbreak of World War II. Afterwards, the 1933 Convention was replaced by the UNESCO Agreement for Facilitating the International Circulation of Visual and Auditory Materials of an Educational, Scientific and Cultural Character, also known as the ‘Beirut Agreement’. Although the latter was designed to “facilitate the free flow of ideas by word and image that would promote the mutual understanding of peoples to encourage the aims of the UNESCO”, it was regarded “in effect as a tariff and trade instrument ” Therefore, the discussion on the interaction between trade and culture began before the creation of the GATT.

In the context of trade, the drafting fathers of the GATT 1947 had undergone a series of difficult discussions on the issue of trade and culture, in particular relating to cinematographic films. The outcome of this debate is the still existing Article IV of the GATT 1947 that allows the GATT Contracting Parties, in the case of cinematographic films, not to fully follow one of the basic principles of the multilateral trading system, namely, the national treatment and general elimination of quantitative duties, in favor of national films.

In addition, this issue was the very reason for the delays during the Uruguay Round because the United States and France had difficulties agreeing on the treatment of audiovisual services under the multilateral trading system. During the Uruguay Round, the audiovisual sector had been debated as an “all-or-nothing” issue: while some considered audiovisual services as entertainment products that were in no way different from any other commercial product, others defended audiovisual products were cultural products and vectors of the fundamental values and ideas of a society. The result of these hard negotiations led to the selection methodology in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), in which members can choose service sectors that they wish to liberalize. In other words, if a member does not wish to liberalize audiovisual services, the member simply does not list the sector in its services schedule. Although more than two decades have passed since this debate on cultural exception, the very same issue re-emerged in the TTIP negotiations.

The Canada-Periodical case fueled the necessity for a non-WTO architect to deal with cultural products issues. In this regard, when Canada and France realized the difficulties for the cultural issue to be resolved in their favor under the multilateral trading system, namely in the WTO, they came to a cooperative endeavor to achieve their goal culture is different from other sectors which led them to turn to UNESCO, not the WTO. The victorious outcome for them was the UNESCO Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, concluded in 2005. This 2005 UNESCO Convention, which came into force in March 2007, has now been ratified by 150 parties. The preamble of the Convention clearly identifies the sensitivities around trade and culture with an underlying preference for culture.

For example, the UNESCO Convention states that Contracting Parties are convinced that cultural activities, goods, and services have both an economic and a cultural nature, because they convey identities, values and meanings, and must therefore not be treated as having solely commercial value. They further note that while the processes of globalization, which have been facilitated by the rapid development of information and communication technologies, afford unprecedented conditions for enhanced interaction between cultures, they also represent a challenge for cultural diversity, particularly considering risks of imbalances between rich and poor countries.

The debate thus far has focused on the assumption that trade and culture have a confrontational relationship, with supporters on either side. Whereas some WTO Members (e.g. the United

17

States) prefer to treat all products similarly, other WTO Members (e.g. Canada and France) are determined to make a clear distinction between cultural and other products when it comes to trade. This book aims to go beyond this contest and explores possibilities to strike a balance between both extremes.

Thus, varying domestic trade policy approaches towards culture are reflected at the multilateral level. The 2005 UNESCO Convention may have contributed to the controversy and has driven a wedge between countries instead of becoming a unifying instrument.

Beyond the domestic and multilateral levels, and particularly because of the stalled negotiations in the Doha Development Round, preferential trade agreements (PTAs) are rapidly growing in importance and in numbers. PTAs increasingly include innovative models for (de)regulating the trade in cultural products.

There may, however, remain considerable potential to discuss the issue of trade and culture at WTO level. The WTO itself may also engage in institutional co-operation with specialized institutions such as UNESCO under the framework of Goal 17 (partnership) of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

There is much more at stake than discussion of culture in the context of trade, this encompasses the appreciation of what culture entails in a rapidly globalizing and integrating economy. Both trade and investment are the lifeblood of such an economy and culture can, in this context, easily be marginalized. At the same time, the exchange between people and companies from different parts of the world can lead to the exchange and mutual enrichment of cultures. These issues are extremely context-sensitive and can best be considered on a case-by-case basis which respects pluralism. Traditional legalistic approaches with binding dispute settlement leave little room for nuance. In that sense, the opportunities offered by more ‘informal’ types of lawmaking should be explored.

Although there is no widely agreed upon definition of ‘cultural products’, some common features of ‘culture-ness’ can be identified: culture is dynamic, social, and contextual. However, further aid for the identification of the cultural components of cultural products in the context of trade is needed. A practical tool, such as a Spectrum for Cultural Products can be designed to categorize specific cultural goods and services based on the UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics.

2. The Significance of the Coordinated Framework Proposed in This Publication

The narrative of literature on trade and culture thus far consists in the opposing views about trade and culture: either culture should ‘get out of the way’ and let trade rule, or trade should be kept at bay to shield culture from the vagaries of economic globalization. This is the antagonistic story usually brought forward in research on trade and culture. 2 To overcome this divisive reporting, my book is an attempt at harmonizing public policy concerns in the field of trade and culture. In conceptual terms, this publication touches upon the dialectic relationship between the arguments that trade liberalization hampers the protection of culture up to the point that it can wipe out culture (thesis) and the view that trade can enhance the diffusion of culture and promote cultural diversity (antithesis). The main goal of this paper is to explore these opposite paradigms and to merge them through a dialectic process into a compromise or other state of agreement via conflict and tension (synthesis).

2 Van Den Bossche P. (2007) Free Trade and Culture: A Study of Relevant WTO Rules and Constraints on National Cultural Policy Measures, Amsterdam, Boekmanstudies; Voon T (2007) Cultural Products and the World Trade Organization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

18

My book also goes beyond most legal scholarship on the issue of trade and culture in the sense that it considers the full range of cultural products based on the ‘cultural spectrum’, which means that it leaves the usual narrow view behind that only audiovisual products are relevant to trade. Furthermore, literature thus far has escaped from pondering the ‘culture-ness’ of cultural products in the context of trade. My contribution sets the stage for a working definition of culture and cultural products which is supported by anthropological and moral conceptualizations of culture. This approach is unique in the sense that literature thus far has rushed into the legal substance of trade and culture without thoroughly investigating a subject which clearly has sociological aspects.

The legal and procedural approach which I adopt is important amidst a clear lack of conciliatory efforts from both institutions and most governments. However, legal, and procedural considerations are no panacea for the political and economic challenges posed by special interests, protectionist popular sentiments, and the prioritization of other unresolved trade issues.

The existing antagonistic approach to trade and culture does not recognize the WTO as an organization which is already equipped with tools to harmonize trade and culture. Not only from the legal perspective detailed overview of the WTO legal provisions which could have an influence on cultural products, and an explicit identification of culture-related/specific provisions. This publication further shows non-legal instruments which can positively aid the discussion on the relationship between trade and culture. From the WTO negotiations perspectives, this publication further analyses the cultural areas of trade negotiations not only through the example of audiovisual services, which are usually interchangeably used for any cultural issue under the WTO without thorough justification, but also other subjects, such as geographical indications and traditional knowledge and folklore. My exploration does not stop at the multilateral level but goes beyond that by examining the potentials of preferential arrangements as a testing ground for finding a healthy equilibrium between trade and culture.

Critically, the book balances the ways forward in future discussions on trade and culture by showing the opportunities which ‘informal international lawmaking’ can offer. Based on its sociological conceptualization of the ‘culture-ness’ of cultural products, the book emphasizes the dynamism of culture which brings to question the suitability of the rigid nature in traditional legalistic approaches towards trade and culture.

Lastly, from an institutional point of view, the coordination between WTO and UNESCO has surprisingly been ignored for a long time. In this regard, this book requires institutional coordination.

3. Key Elements of the Book

This study has sought to answer the following question: How can policies on trade and culture be coordinated in such a way that both are enabled to flourish? To answer that question, a working definition of culture was needed to set the tone for the entire study. This publication thus started by providing three dimensions of ‘culture-ness’ as key cultural characteristics that can be a filter for cultural products in the context of trade, notably that:

i. Culture is social,

ii. Culture is dynamic (evolutionary and constantly changing), and iii. Culture is contextual.

19

Further, the Spectrum for Cultural Products was based on these three common features and aided the identification of ‘cultural products’ in the context of trade. Additionally, cultural products were differentiated on scales based on the 'strength' of their culture-ness.

Chapter 2 focuses on the standard-setting instruments of UNESCO to compare the widely known 2005 UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions with other UNESCO standard-setting instruments. The Chapter demonstrates that in contrast to a successful example of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, the 2005 UNESCO Convention does not yet reach the desired level of protecting cultural diversity. Consequently, the Chapter reflects upon whether the 2005 UNESCO Convention should have taken the incremental approach which had been identified as one of the reasons why other UNESCO standard-setting instruments, such as the World Heritage Convention, are widely supported by the international community. Given that the life of the 2005 UNESCO Convention is still evolving since its entry into force in 2007, the Chapter suggests that the 2005 UNESCO Convention continuously undertake the incremental approach in its implementation. In this context, the Chapter suggests the 2005 UNESCO Convention be renewed to better safeguard the collective spirit of the international community in protecting cultural diversity.

Chapter 3 explores the landscape of domestic cultural policies of key WTO Members that can impact their trading partners. The Chapter points to certain weaknesses in the different economic rationales that argue cultural products are economically different from other products. Clearly, there is no single tendency or trend that one can identify among the diversified approaches by these key WTO Members in terms of protecting their cultural products. Such difficulty in detecting a trend was more challenging for tariff measures than for non-tariff measures. The reason for this could be the lack of a common definition of cultural products which further results in the lack of an established scope for cultural goods. Chapter 3 also identifies certain similarities in key WTO Members' non-tariff measures, particularly in the audiovisual sector.

As Chapter 3 shows, a major challenge is to clearly draw the line between disguised trade protectionism and bona fide cultural concerns. Although this challenge may arise at the national level, the deficiency of international level co-operation on agreed standards in this regard further accelerates the domestic challenges. The fact that there is currently no international or regional institution that is explicitly mandated to tackle the dilemma between trade protectionism and legitimate cultural concerns calls for co-operation at international level.

Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 aim at responding to this call. While Chapter 4 focuses on enhancing the prospective for the WTO to serve as a forum for discussion on trade and culture, Chapter 5 addresses a new era of preferential trade agreements (PTAs) which is quietly being paved as a complementary tool for the linkage between trade and culture.

Chapter 4 demonstrates the existence of implanted tools in the WTO for the co-operation between culture and international trade law from the legal, negotiation, administrative, and WTO accession perspectives. This Chapter emphasizes the importance of a tightly connected pivot across these four functions of the WTO for addressing WTO Members' cultural concerns. Additionally, the point which Chapter 4 tries to make is that, in contrast with the general perception, the WTO could well offer a credible venue for discussing the relationship between trade and culture. In this regard, I identified and emphasized the non-dispute settlement functions of the institution as the appropriate tools for the coordination between culture and international trade law, beyond the already well-recognized dispute settlement function of the WTO. This argument is based on the inherent nature of culture which is identified in Chapter 1 of the study.

20

Similarly to Chapter 4, Chapter 5 considers fora that could play a role in the general treatment of cultural products, namely PTAs. This Chapter examined the PTAs of the leading countries which have been active in the discussion on trade and culture, either at the UNESCO or WTO level, in particular. Thus, Chapter 5 distinguishes major PTA models useful in treating cultural products in PTAs.

Surprisingly, the 2005 UNESCO Convention's impact on PTAs was marginal, except for the EU model, which utilized the 2005 UNESCO Convention in the Protocol on Cultural Co-operation annexed to its preferential trade agreements. This may also suggest the necessity for better collaboration between these two communities: trade and culture. China and New Zealand were identified as culturally conscious and as pursuing innovative cultural policies in the context of PTAs.

Chapter 5 also explains that bilateral investment laws have in a way been more developed in embracing a segment of culture (cultural heritage) than international trade law thanks to the limited scope of culture that international investment law thus far needed to deal with. In my Spectrum of Cultural Products, cultural heritage is one of the six key segments, which is identified as the least controversial.

Chapter 6 presents specific suggestions for ways forward on how to better coordinate the treatment of cultural products in the context of international trade law. Finding a culture-friendly way in the trade context is emphasized broadly in two ways: the first according to a dispute settlement approach, and the second according to a non-dispute settlement approach. Within the dispute settlement approach, I first identify classical trade dispute settlement, particularly in the WTO dispute settlement system but still not conservative in the sense that the classical dispute settlement aims at an evolutionary interpretation approach; and second, informal international lawmaking based on the nature of culture itself is identified as innovative and complementary. Within the non-dispute settlement approach, monitoring, negotiations, and institutional coordination are argued to have a positive effect at multilateral level.

Due to its dynamic nature, culture may not fully match with any rigid form of legality, which is why my preferred way of considering the issue of trade and culture, as presented in Chapter 6, is in non-dispute settlement-oriented, i.e. monitoring/surveillance, negotiations, or institutional cooperation which are not geared towards conflict. However, my ways forward also include the dispute settlement-oriented approach, such as evolutionary treaty interpretation, and informal international law making.

Additionally, for the scenario in which a new agreement could be designed specifically for the issue of trade and culture in the realm of the WTO, a Plurilateral Agreement, or like-minded Members' Initiatives on Cultural Products, is suggested as an appropriate form. Chapter 6 further suggests the APEC (covering the Asia-Pacific region) and the Council of Europe (covering the European region) as appropriate regional forums for developing a working agenda on the relationship between trade and culture.

The aim of this book is to analyze the phenomenon of the inter-relationship between trade and culture. The publication underlines the extensively divisive opinions which revolve around the relationship between trade and culture, and their impact on each other. Nonetheless, when elaborating the possible new approaches in an attempt to contribute to the debate on this issue, what I pursued was the design of those approaches in a constructive way and not in a conflicting way so that policies on trade and culture can be coordinated.

21

I fully recognize the complexity of the issues I address and hope that this book will facilitate deeper conversation about the ways in which culture and trade move from conflict and shape meaningful coordination and dialogue, which are intrinsic to culture itself and the very purpose of its existence.

References

Lee, Juneyoung (2023) Culture and International Trade Law: From Conflict to Coordination, Leiden and Boston, Brill.

Van Den Bossche P.(2007) Free Trade and Culture: A Study of Relevant WTO Rules and Constraints on National Cultural Policy Measures, Amsterdam, Boekmanstudies

Voon T. (2007) Cultural Products and the World Trade Organization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

22

23

What factors influence the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship in Jordan?

Nawal Tarazi 1

Abstract

The Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) presented a study report (NFIS 2018-2019) in collaboration with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH highlighting that 67% of people in Jordan above the age of 15 do not have access to the formal financial system in terms of bank account ownership. Only 33% of adults in Jordan, among whom only 27% of women, are considered financially included. This percentage is considered low even when compared to other countries with the same income level

The research study employed a non-probability sample of 542 individuals to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the individual and social factors that influence the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is the base theory underpinning this research. The Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling method (PLS SEM) was employed for quantitative analysis. The findings affirm key independent factors including economic knowledge, age, income, financial literacy, economy, financial technology, and trust affect the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship in Jordan highlighting the gender differences. Engagement leads to more sustainability and development, thus improving financial inclusion in the country. The results can serve as practical guidelines for bank managers, regulators, and policymakers.

Keywords: Engagement, banking relationship, financial behavior, theory of planned behavior (TPB).

Background

A banking relationship as described by Petersen, & Rajan, (1994) is a close relationship and continued interaction over time, involving multiple products. Sashi’s (2012) definition of customer engagement focuses on satisfying customers by providing greater value when compared to competitors, this satisfaction builds trust and commitment in long-term relationships, thus leading to a higher level of engagement in the long term. Tezel (2015) and Özmete (2015) define financial behavior as a behavioral economic decision. The skills, abilities, attitudes, and patterns of this behavior are essential for making the right financial decisions both on a personal and social scale (Atkinson and Messy, 2012). The most important component of financial skills is financial literacy as highlighted by Csiszárik Kocsir et al. (2017) and confirmed by Xu & Zia (2012) who state that financial skills are not inborn skills, they are acquired, which supports the importance of financial literacy.

The financial sector is considered the backbone of any economy. Development, growth, and achievements of the financial sector are reflected in other sectors of the economy. Several studies including Levine (2005), Bencivenga and Smith (1991), King and Levine (1993), Odedokun (1998), Xu (2000), and Shamim (2007) empirically found a correlation between financial development and economic growth.

24

1 Nawal Tarazi is Head of Department and Adjunct Professor at the International Institute in Geneva.

According to the Association of Banks in Jordan 2021 Annual Report, there are twenty-three banks operating in Jordan as of year-end 2021. Thirteen are commercial Jordanian banks, six foreign banks and four are Islamic banks. As of year-end 2021, the total assets of banks operating in Jordan reached JD 61.06 billion (USD 86.12 billion) and direct credit facilities granted by banks reached JD 30.03 billion (USD 42.36 billion). According to the Central Bank of Jordan (2022), Financial Inclusion is the state wherein individuals and businesses have convenient access to and use affordable and suitable financial products and services, payments, savings, credit, transactions, and insurance that meet their needs, help to improve their lives, and are delivered in a responsible and sustainable way. Jordan’s policymakers are aware of the importance of the inclusion strategy and are committed to following and realizing the economy’s objective of sustainability and growth.

The Financial Inclusion Diagnostic Study in Jordan for the year 2017 (Central Bank of Jordan, 2018) stated that the level of formal financial inclusion in Jordan is quite low for some types of financial products and among certain segments of the population. The World Bank Global Findex’s Database reported that only 25% of Jordanians above 15 years of age had a bank account in 2014, with a much lower rate for women (15.5%) than for men (33.3%). This percentage increased to 42.5% account owners in 2017 (26.6% women vs. 56.3% men) and 47% in 2021 (34% women compared to 58.6% men) (The World Bank, 2021; Development Research Group, 2022).

A study conducted by the Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) in cooperation with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (NFIS 2018-2019) prompted the Jordanian authorities to act and try to understand the reasons for low financial inclusion in Jordan. Their objective was to find ways to boost the availability and the quality of financial services. It stemmed from their belief that low financial inclusion as reflected in the low level of engagement in financial behavior represented in the form of bank account ownership has severe consequences on the economy in general and more specifically on the banking sector. The intention of behavioral change was asserted by actions taken by the highest authorities and national-level policymakers including the Central Bank that strongly believed in the seriousness of the issue.

Earlier studies on the financial behavior of individuals and their level of engagement in a banking relationship were limited in scope and depth. Existing literature on the topic focuses mostly on aspects related to relationship behavior and customer satisfaction once the banking relationship has been established. Fewer studies consider studying the antecedent factors that affect the behavior of individuals establishing a banking relationship and enhancing their engagement. There is thus a gap in the current body of knowledge which this research endeavors to address.

The primary aim of this research is to determine the main antecedents, individual and social factors, that impact the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship in Jordan. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 2019) is the base theory that acknowledges the role of social reality and provides a basis for understanding causal relationships. The factors explored within the research are age, income, education, economy, economic knowledge, financial literacy, financial technology, and trust, in addition to gender. The objective of identifying and understanding the role of these factors can help to shed light on the reasons behind the relatively low level of engagement of individuals with the banking system in Jordan. The research also seeks to suggest means and tools of intervention to encourage greater financial engagement.

25

Moreover, the research pays specific attention to the influence of ‘Gender’ on the above factors. It also places a particular emphasis on investigating the influence of financial literacy in enhancing the level of individuals’ behavioral engagement in a banking relationship.

The objectives of the research are:

1. To determine the individual and social factors that enhance the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship.

2. To examine the influence of financial literacy in enhancing the level of behavioral engagement of individuals in a banking relationship.

3. To investigate the influence of ‘Gender’ and if the above dynamics vary by gender.

Examining interventions from independent variables to core variables (control beliefs) that would lead to changes in the financial behavior is a fairly new perspective that has been adopted in earlier studies but only on a very limited scale. This research addressed this gap by incorporating research literature on behavioral change that lead individuals to alter their financial behavior through improved engagement in a banking relationship, thus impacting the sector and eventually the economy.

Literature Review

The TPB was initially presented in Ajzen and Fishbein’s 1972 expectancy value model of attitude which was then expanded and presented by Ajzen (1991). This theory highlights the significance of beliefs in shaping human behavior. According to the TPB, the three types of beliefs are behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. The strength of these beliefs is associated with the perceptions of behavioral control or what the TPB presents as perceived behavioral control (PBC), given that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control represent the three conceptual independent determinants of intention, whereas the actual behavioral control is directly related to perceived behavioral control. The TPB indicated that the engagement in a behavior is influenced both by intentions and PBC which should be assessed fairly towards a specific behavior to realistically reflect the actual control over that behavior.

According to the TPB, individuals’ behavioral intention is expected to lead to the final behavior. Intention can be defined as follows: how ready an individual is to perform a certain behavior based on attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 2002). Some studies such as Sahoo and Pillai (2017) and Kosiba et al. (2018) presented evidence on limited drivers and outcomes of customer engagement in some banking services. This research contributes to the understanding of the individual and social factors and will determine their effectiveness on individuals’ financial behavior in terms of level of engagement in a banking relationship.

Several studies argued the important role played by financial literacy and its influence on financial behavior. Supporting the study’s objectives, Andarsari and Ningtyas (2019) reported a positive and significant influence of financial literacy on financial behavior. The same study reported that women are expected to lead the future of the world’s economy by 2028 and are expected to take 75% of the world’s discretionary expenditure. The engagement concept is adopted in this research as an important component of customer relationship management and is directly related to consumer behavior in terms of active and engaged purchase of a service or product.

Based on the findings from the preceding literature review (Ji and Wang, (2014), Mittal et al. (2005), McDonald & Rundle (2008) supported by Freeman’s (1984), Tezel (2015), Mthembu

26

(2014), Geva (2001), Demirgüç-Kunt (2018), as well as LaMorte, (2022)), and within the parameters of this research, the engagement in a banking relationship is determined by the ownership of an account at a bank, and the level of engagement is defined as the intensity of an individuals’ usage of banking services. Thus, supporting the concept of banking relationship that starts with an account opened in the name of a customer regardless of its type. The engagement is the customer’s financial behavior which is driven by the expectation of financial assistance and practicality of financial services, the aim of which is to ease financial pressure, provide support, and facilitate financial operations.

The antecedents’ effect supported the use of the TPB to explain the final behavior. Several other studies used the TPB to study banking behavior such as Aziz and Afaq (2018), Yadav et al. (2015), Chai and Dibb (2014) , Çoşkun and Dalziel (2020), Deenanath et al. (2019), Tucker et al. (2019), Bapat’s (2019), Loibl et al. (2021), Ibrahim and Arshad (2017), Ambad and Damit (2016), Flores and Vieira (2014), as well as Bashir and Madhavaiah’s (2014).

According to the TPB, human behavior is influenced by three types of beliefs: behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. A ‘Belief’ according to Schwitzgebel, (2019) is a “state of mind” wherein one person places trust or confidence in others. These beliefs produce the core, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control that drive individuals’ financial behavior in the form of level of engagement in banking relationships. Attitude towards the behavior is the degree to which an individual has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior concerned.

“Subjective norms” refer to the perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a behavior. It is assumed that subjective norms are determined by a set of normative beliefs concerning the expectations of important references or close individuals such as family, friends, co-workers, supervisors, or doctors. Normative beliefs, together with an individual’s motivations, determine the subjective norms. The construct of “perceived behavioral control” refers to people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest; the perception of behavioral control is an impact of intentions and actions (Ajzen 1988 & 1991).

The TPB does not specify where these beliefs originated from but presents several possible background factors that include individual and social factors which have proven to impact the individual’s beliefs and attitudes (Ajzen 1985). The background factors may influence the beliefs people hold, some of these factors are of a personal nature such as personality and broad life values; demographic variables such as education, age, gender, and income; and exposure to media and other sources of information.

This research will follow a path to test some background factors, taking into consideration that some factors such as age, income, gender, culture, and economy cannot be changed or influenced but will assist in confirming the strength or weakness of a relationship. Other factors, however, such as knowledge, education, financial literacy, and FinTech can be transformed, thus determining the relationship between factors before designing effective intervention methods which lead to the necessary behavioral change. The research will pave the way to clarify the kind of intervention needed to improve efficiency. In addition to the above independent individual and social factors, the research adds other related factors that are believed to have an impact on financial behavior: ‘Trust’ and ‘Economic Knowledge’. These will be justified in the upcoming analysis.

Research Methodology

As this research is theory driven, a deductive approach to theory development was followed subject to rigorous testing. This research used the lens of the TPB (Ajzen, 2019) to understand the changes in human social behavior to be able to predict it. The TPB assumes a social reality

27

and provides a basis of explanation indicating causal relationships. Several hypotheses were developed and then the data collected were analyzed using a quantitative approach.

Model of the TPB (Ajzen, 2019)

The research adopted the positivism and post-positivism philosophical assumptions on social sciences which usually lead to the development of models that can predict human behavior. The methodology was the “Deductive Explanatory Methodology”, which is the most common process in social sciences that tends to justify what is happening by using hypotheses to explain relationships among variables. Results determine relationships between factors thus enabling the design of effective interventions that would lead to the needed behavioral change.

The strategy for data collection consisted in a survey administered as a questionnaire and used as the instrument. The questionnaire that included twenty-nine questions, was prepared in both English and Arabic and was inspired by previous high ranked related studies in literature. The questionnaire was structured, standardized, tested, and administered to allow respondents to select the most appropriate option to reflect factors being studied. The research study investigated a non-probability sample of five hundred and forty-two (542) individuals who successfully completed all questions, to obtain a broad view of the individual and social factors that influence the level of engagement of individuals in a banking relationship in Jordan. The target population included Jordanians living in the eight largest cities of Jordan. Data was collected mostly electronically and in certain cases manually, depending on the location and electronic reach of some members within the target population.

The purpose of this research is to understand and observe the effect of the independent variables on the mediating/core variables then relate and propose new ideas and interventions that affect the dependent variable which is the financial behavior towards the level of engagement in a banking relationship.

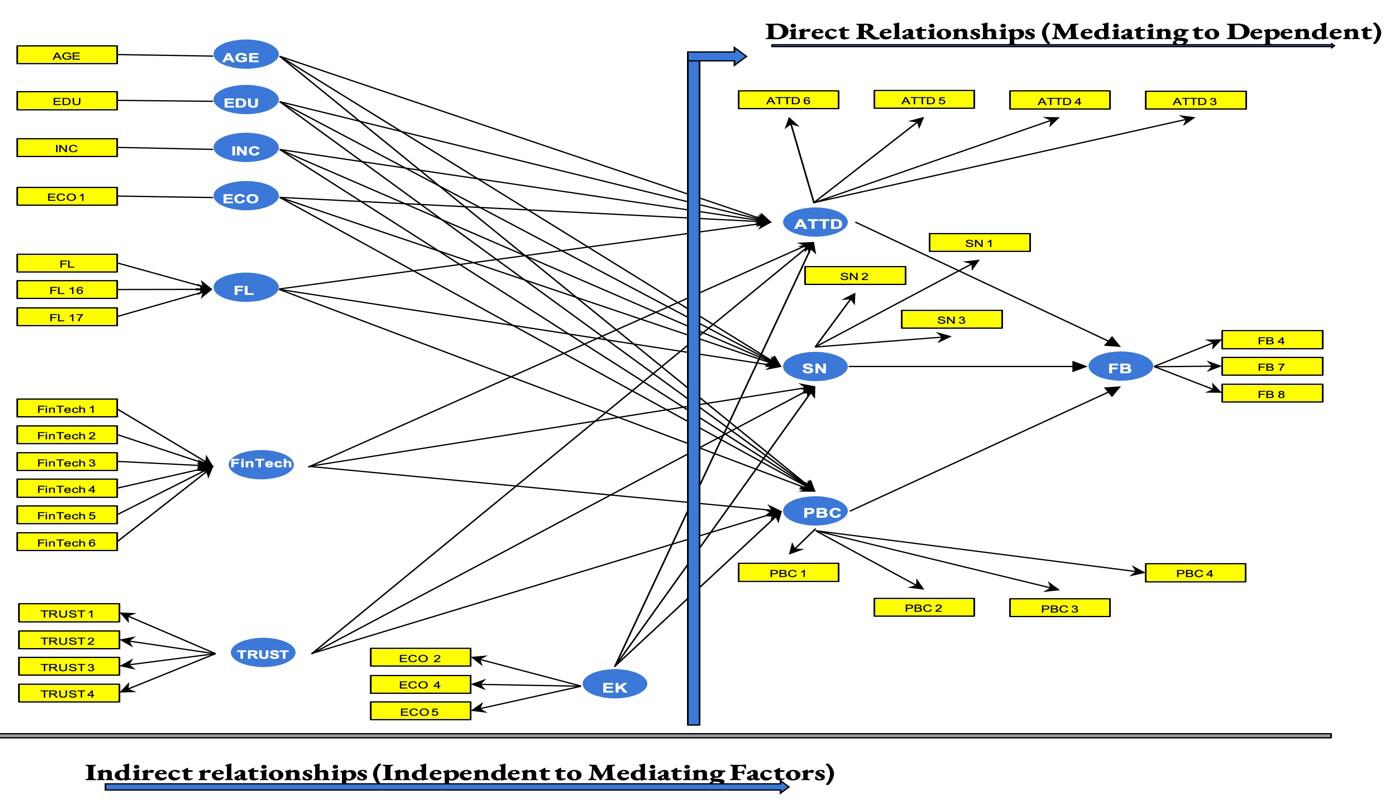

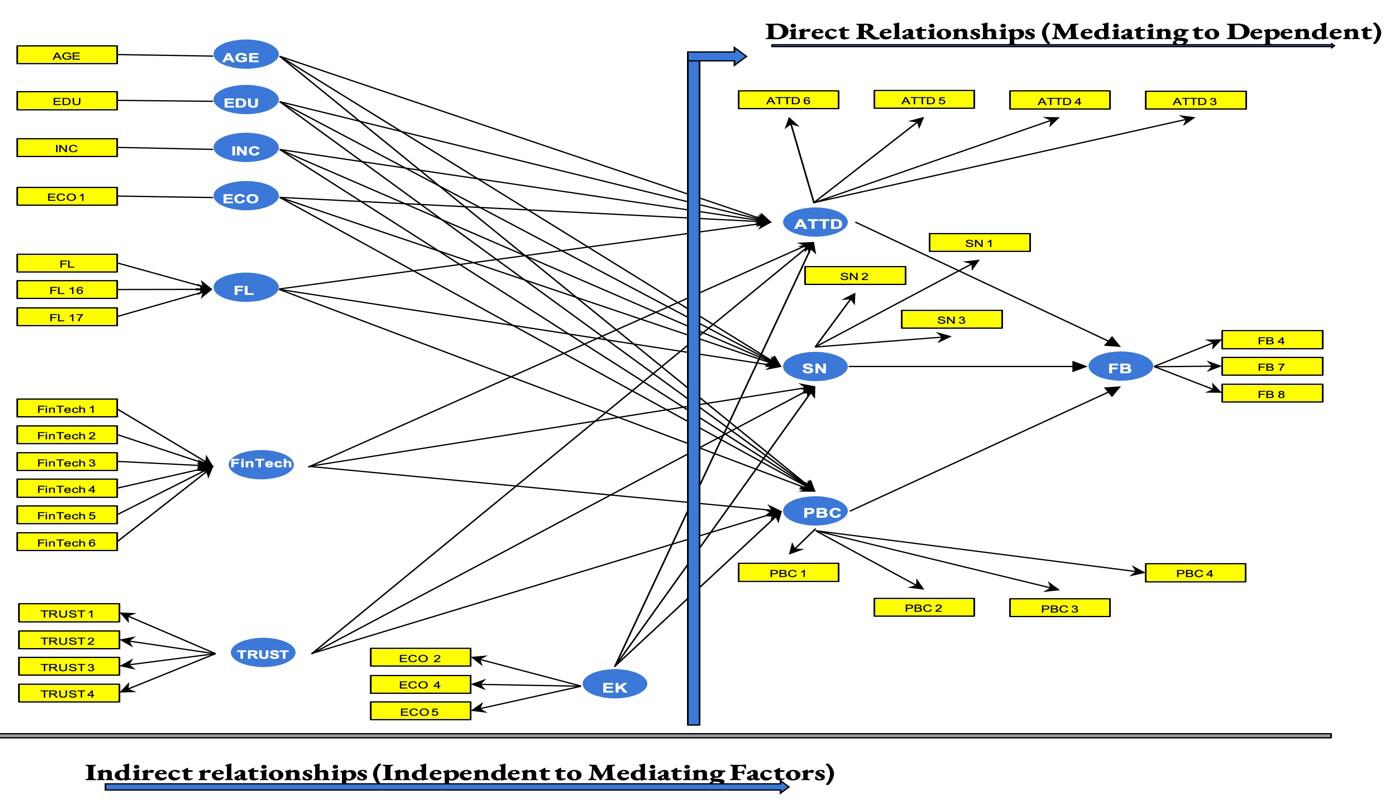

The conceptual model of the TPB used for this research is highlighted in the figure below underscoring the independent factors that were selected from the TPB (age, education, income, economy, knowledge) in addition to the three factors that were added (trust, financial literacy and Fintech). Three mediating / core factors (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) in relation to the dependent factors being the financial behavior which reflect the level of engagement in a banking relationship. Gender was presented as a moderating variable defined by Allen, M. (2017) as variables that can strengthen, diminish, deny, or transform the relationship between independent and dependent variables. Sometimes moderating variables can change the direction of the relationship or help explain the links between the independent and dependent variables. Several hypotheses were presented and investigated to explore relationships and significance using the PLS SEM.

28

Using PLS SEM

The study employed a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling method, referred to as PLS SEM path modelling which is a popular method for estimating complex path models with latent variables and their relationships. The main goal of SEM is “statistical methodology that takes a confirmatory i.e. hypothesis-testing approach to the analysis of a structural theory bearing on some phenomenon” (Byrne, 2013, p. 3). When applying SEM, it is important to highlight the difference between the measurement model (outer model) and the structural model (inner model), which present the relationship between latent constructs known as factors and their indicators at the outer model, whereas relationships among latent constructs with each other are presented at the inner model (Henseler et al., 2009; Jarvis et al., 2003).

The PLS SEM analysis approach explains the relationships among multiple variables using a series of multiple regression equations, whereby causal relationships between constructs are represented by multiple regressions. This method is used for investigating cause effect interactions between constructs and variables and is suitable for both theory building and testing. The PLS-SEM technique is widely used in business research and offers the researcher a considerable flexibility in terms of model specifications and data. It is considered to be an adequate technique for both theory building and testing (Hult et al., 2009 and Hair et al., 2011). The principal step of SEM is the establishment of a path model which is a diagram that displays hypotheses and variable relationships to be estimated (Bollen 2002). A path model displays “constructs” also referred to as “latent variables”, which represent conceptual variables that the researcher has defined in the theoretical model. It is important to determine the nature of the latent variables or constructs i.e. reflective vs. formative. Constructs appear in circles linked via single-headed arrows that represent predictive relationships to the “indicators” that are also names or “manifest variables or items” that appears in rectangles and represent the raw data collected, whether through direct measurement or observation.

In this research, as highlighted in the figure below developed by the PLS SEM, the constructs that appeared as latent variables were the independent variables: Age (AGE), Income (INC), Education (EDU), Economy (ECO), Economic Knowledge (EK), Financial literacy (FL), Financial Technology (FinTech), and Trust (TRUST). Each construct was linked to indicators that measured these constructs, represented by answers from the survey questions measuring that construct. The remaining constructs appearing as latent variables in the middle section of the model included Attitude (ATTD), Social Norms (SN), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC),

29

and then Financial Behavior (FB), a dependent latent variable which appears to the right of the model.

The results of conducting the PLS SEM tests to assess the structural model and investigate the proposed hypotheses are summarized in the table below indicating relationship strength, direction, and impact.

30

Hypotheses/Relationships Original Sample (O): Path (sign +) Coefficients (Significance)* P Values < 0.05 **R2 Supported (Yes/No) Description ATTD -> FB 0.120 0.024 0.326 Positive, significant & substantial. AGE -> ATTD 0.129 0.001 0.326 Positive, significant & substantial. AGE -> PBC -0.004 0.915 0.492 Nonsignificant AGE -> SN -0.024 0.583 0.528 Nonsignificant. EK -> ATTD 0.300 0.000 0.326 Positive, significant & substantial. EK -> PBC 0.090 0.039 0.492 Positive, significant & substantial.

significant & substantial.

*P Values < 0.05 considered significant **R2 values of 0.26, 0.13 and 0.02 can be considered substantial, moderate, and weak.

Findings & Discussion

Five hundred forty-two (542) individuals successfully completed the full questionnaire, and their responses were analyzed. The gender participation was 58% women versus 42% men. Of total participants, 58% were between the age of 40-59 years, 65% were private business employees, business owners or self-employed and 85% of the participants hold both a graduate and post graduate degrees. Most participants live in the capital Amman which is the main business and financial hub and 55% of all participants had been exposed directly or indirectly to economics and finance studies or courses. 31.37% of participants earn JD 1001-JD 2500 (USD 1400-3500) monthly, which is considered high income. 38.5% stated that they use the services extremely often (almost daily), and 36.7% use the banking services very often (weekly).

31 EK -> SN 0.131 0.014 0.217 Positive, significant & moderate. ECO -> ATTD 0.057 0.143 0.326 Nonsignificant ECO -> PBC 0.018 0.629 0.492 Nonsignificant ECO -> SN 0.120 0.007 0.217 Positive, significant & moderate. EDU -> ATTD -0.060 0.177 0.326 Nonsignificant EDU -> PBC -0.011 0.740 0.492 Nonsignificant EDU-> SN 0.031 0.543 0.217 Nonsignificant FL -> ATTD 0.042 0.357 0.326 Nonsignificant FL -> PBC 0.153 0.000 0.492 Positive, significant & substantial. FL -> SN 0.030 0.531 0.217 Nonsignificant FinTech -> ATTD 0.194 0.001 0.326 Positive, significant & substantial. FinTech -> PBC 0.270 0.000 0.492 Positive, significant & substantial. FinTech -> SN 0.217 0.000 0.217 Positive, significant & moderate. INC -> ATTD -0.078 0.075 0.326 Nonsignificant INC -> PBC 0.017 0.693 0.492 Nonsignificant INC -> SN -0.112 0.033 0.217 Negative, significant & moderate. PBC -> FB 0.592 0.000 0.528 Positive, significant & substantial. SN -> FB 0.133 0.000 0.528 Positive,

TRUST-> ATTD 0.184 0.003 0.326 Positive,

TRUST -> PBC 0.363 0.000 0.492 Positive, significant & substantial. TRUST -> SN 0.163 0.009 0.217 Positive, significant

significant & substantial.

& moderate

The findings confirmed that as per the main theory applied in this research; the TPB revealed and confirmed that ATTD, PBC, and SN play positive, significant, and substantial roles in the financial behavior of individuals as indicated by the level of engagement in a banking relationship in Jordan.

The dominant core factor to influence the level of engagement in a banking relationship is PBC, which was proved and influenced by individuals’ independent factors EK, TRUST, FL, and FinTech. The findings indicated that most respondents lacked confidence in their ability to choose financial investment products and mostly chose to invest in real estate; revealing a need to provide more information about products and emphasize the need for increased involvement by the financial service providers.