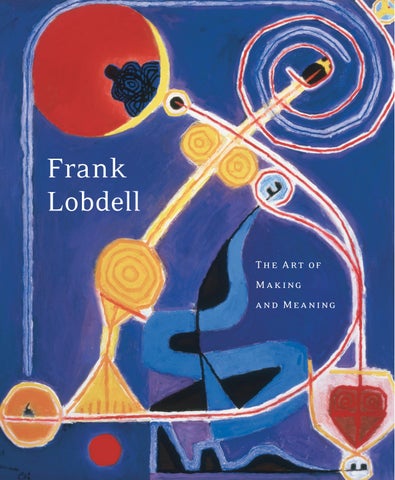

Frank Lobdell

TEXTS BY Timothy Anglin Burgard

Walter Hopps

Bruce Nixon

Robert Flynn Johnson

Bruce Guenther

Anthony Torres

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In association with Hudson Hills Press New York and Manchester

vii Foreword

Harry S. Parker III

xi Introduction

Bruce Guenther

1 Beyond Words: The Hand of Humanity

Timothy Anglin Burgard

9 Paintings and Graphics from 1948 to 1965

Walter Hopps

29 A Wonderland of His Own

Bruce Nixon

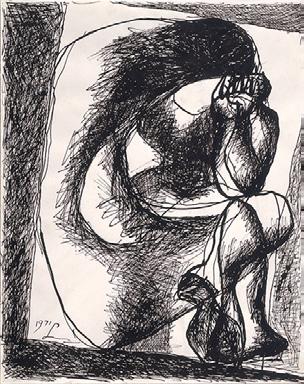

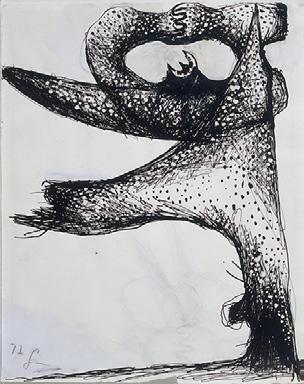

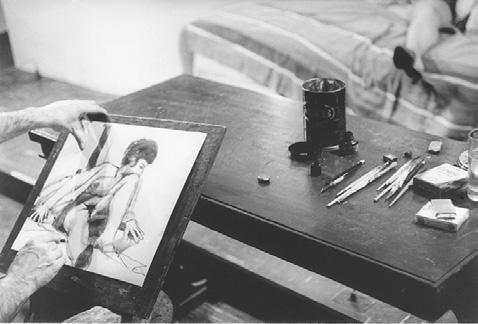

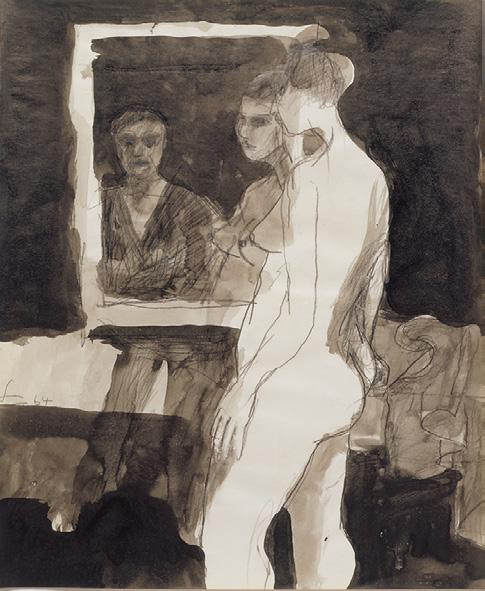

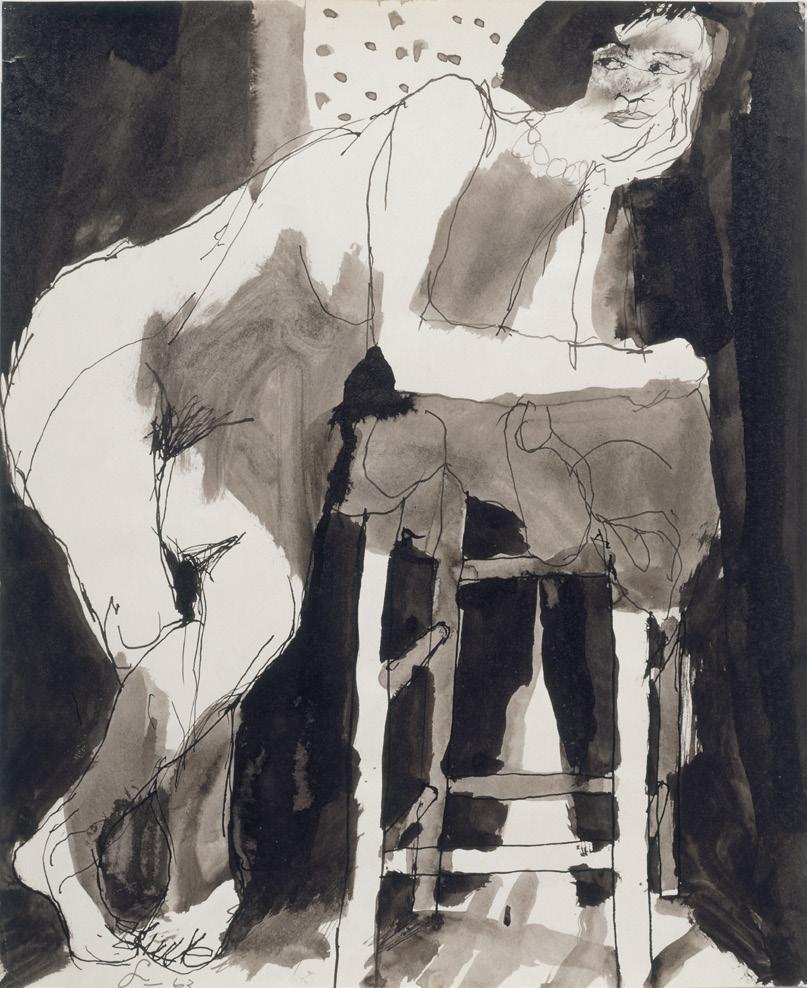

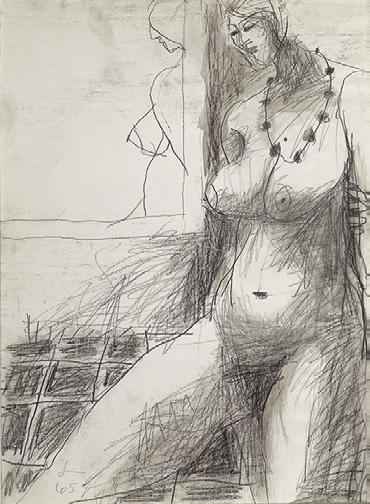

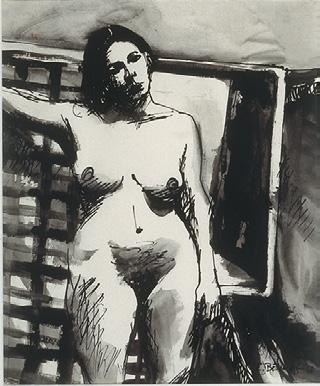

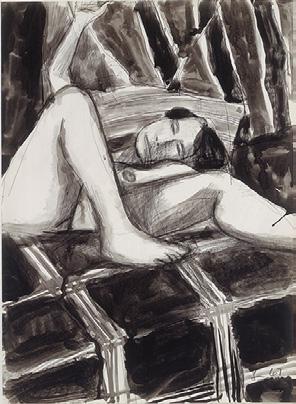

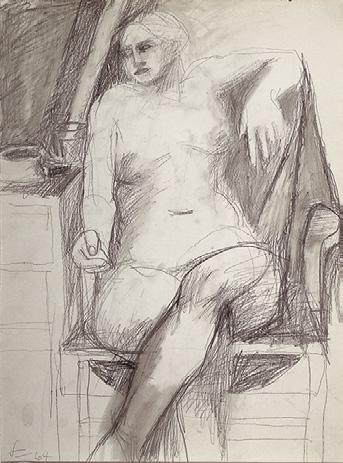

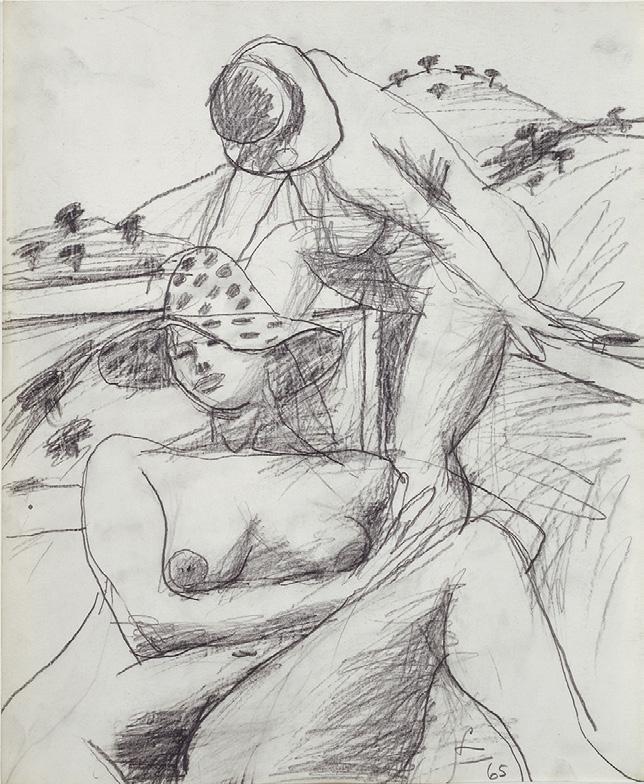

179 The Drawing Process

Robert Flynn Johnson

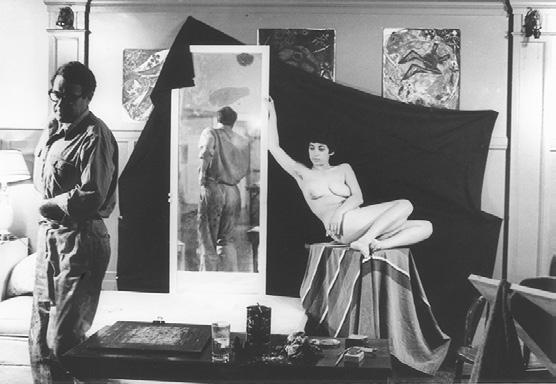

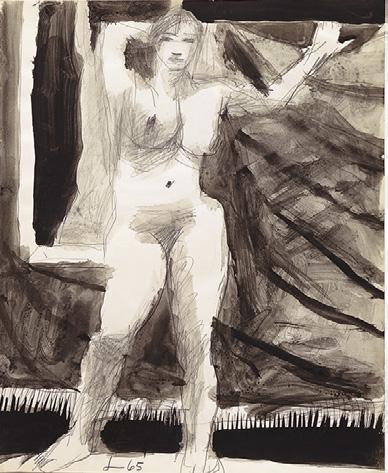

191 Every Thursday Night

Bruce Guenther

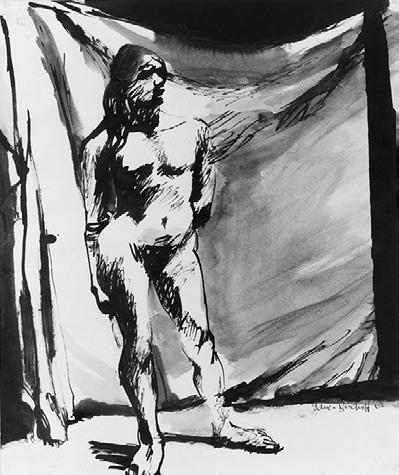

229 The Life of the Hand

Bruce Nixon

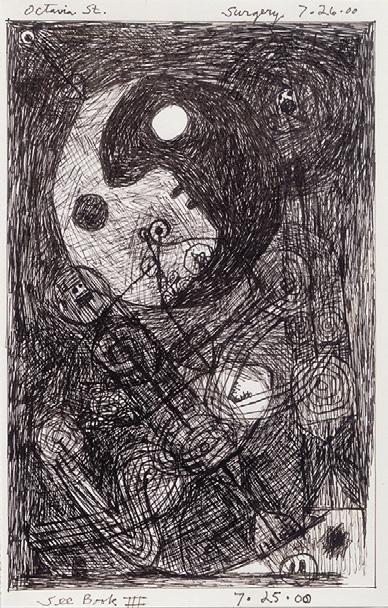

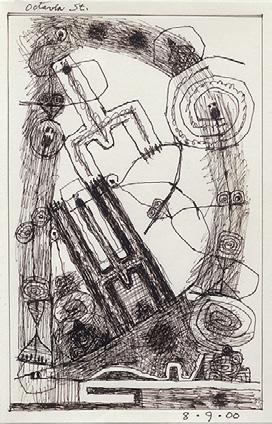

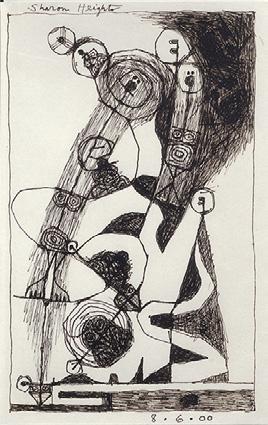

279 Negotiating Space: The Sketchbooks

Anthony Torres

301 Illustrated Chronology

Diane Roby

Anthony Torres

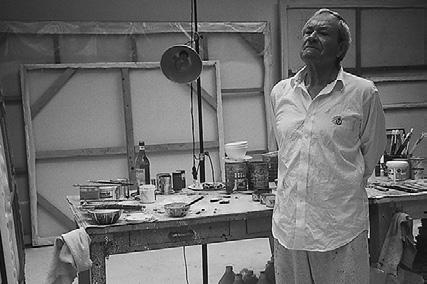

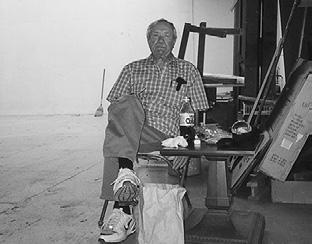

For over half a century, Frank Lobdell’s work has immeasurably enriched the local and national cultural landscape. His stature is reXected in the acclaim of art critics, in the respect of fellow-artists, and in the admiration of his students, regardless of their personal artistic philosophies. To state that Lobdell is “an artist’s artist” is to acknowledge that he has pursued his calling with passion, discipline, and integrity, and that he has elevated the creation of art above its reception in the art world.

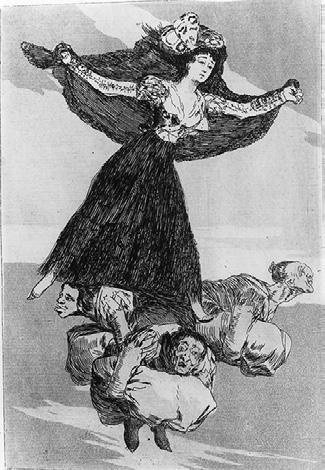

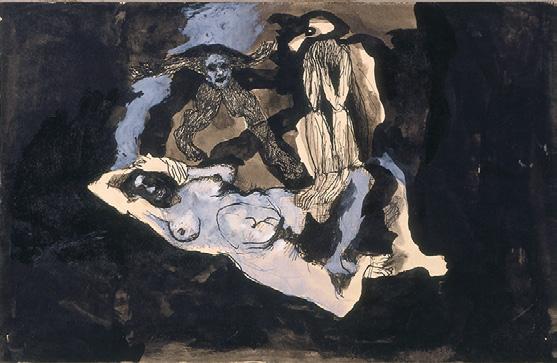

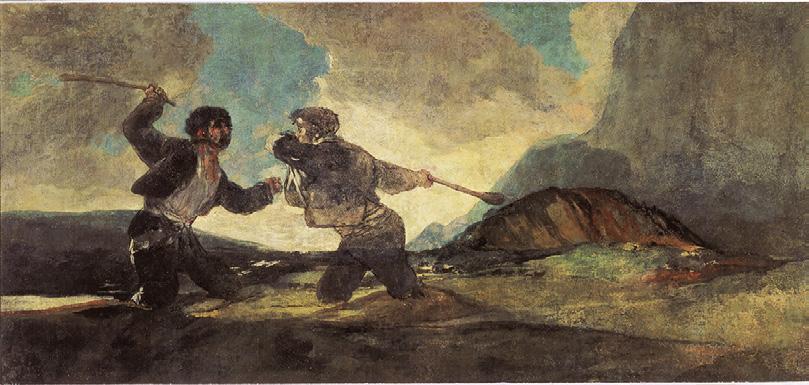

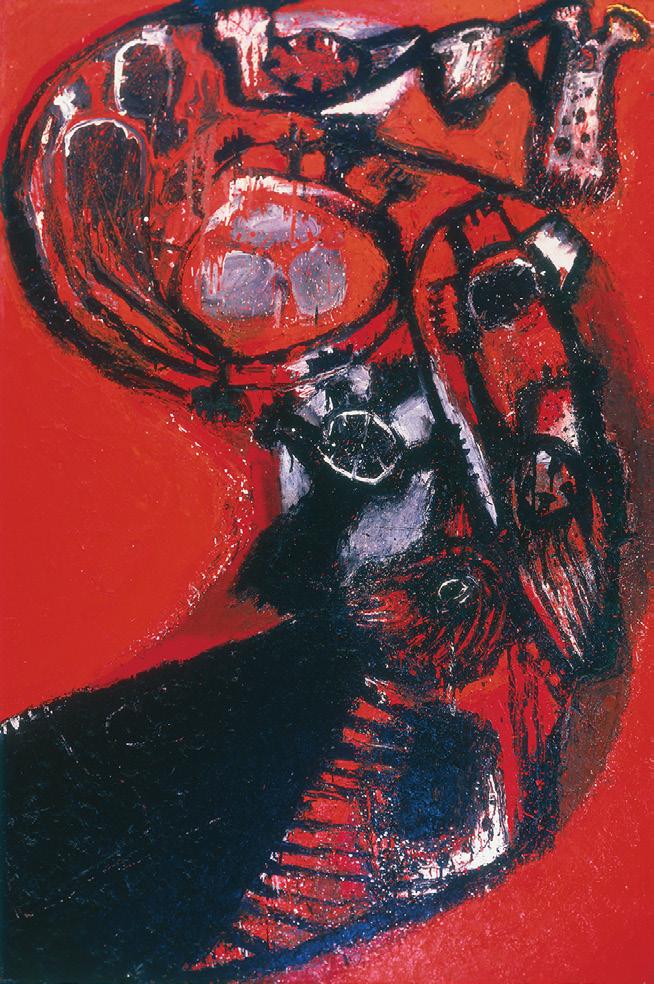

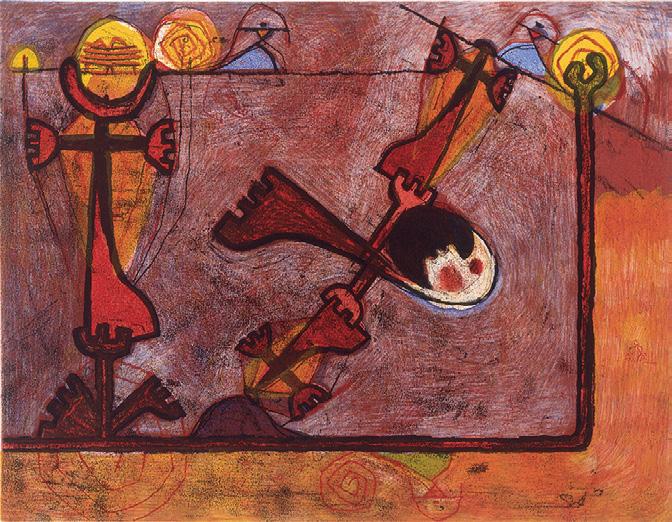

Lobdell’s diverse body of work is linked by its shared sense of humanity. In the 1940s, he was among the pioneers of the San Francisco Bay area school of abstract expressionism. During the 1950s, he gradually reintroduced the human Wgure into his work, thus expanding conventional conceptions of both abstraction and Wguration. Drawing inspiration from the vision of Francisco Goya, these works presented a dark, existential worldview shaped by the cumulative horrors of World War II, the Holocaust, the atomic bomb, and the Korean War.

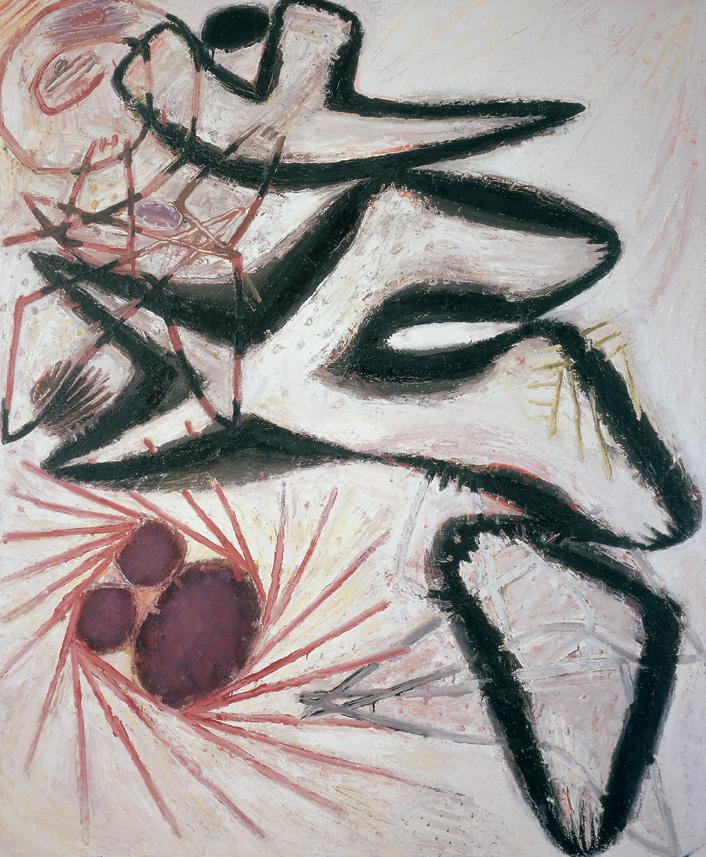

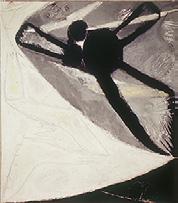

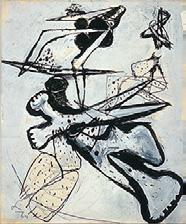

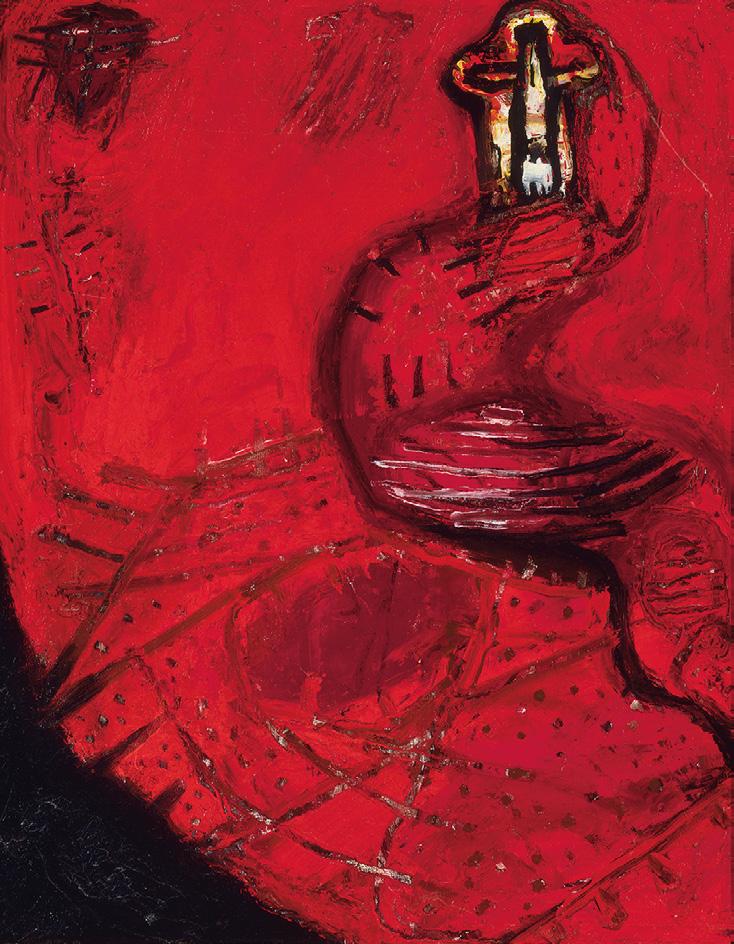

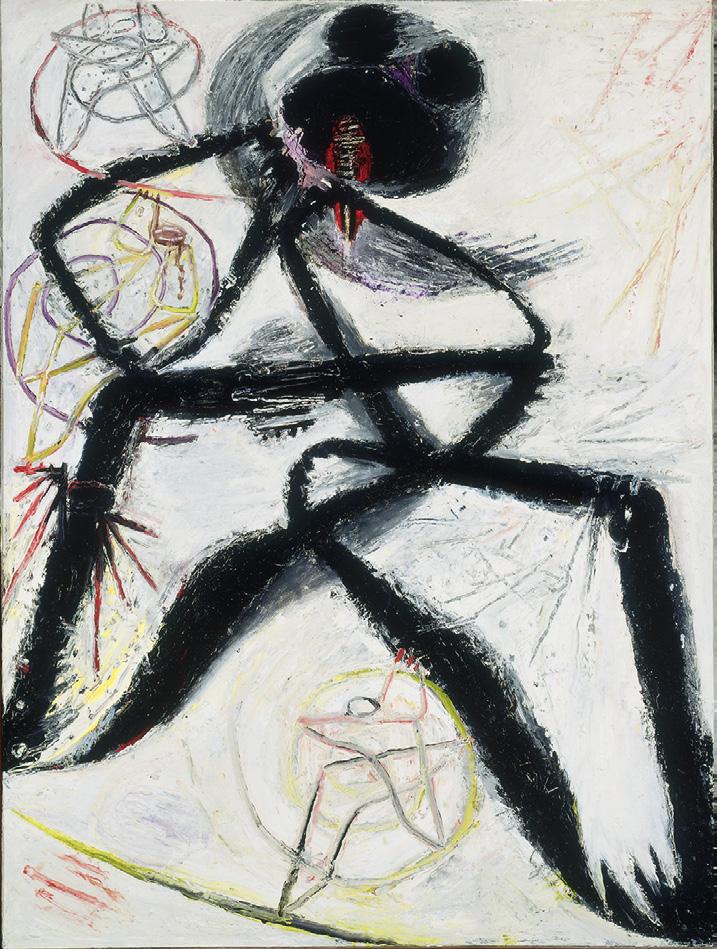

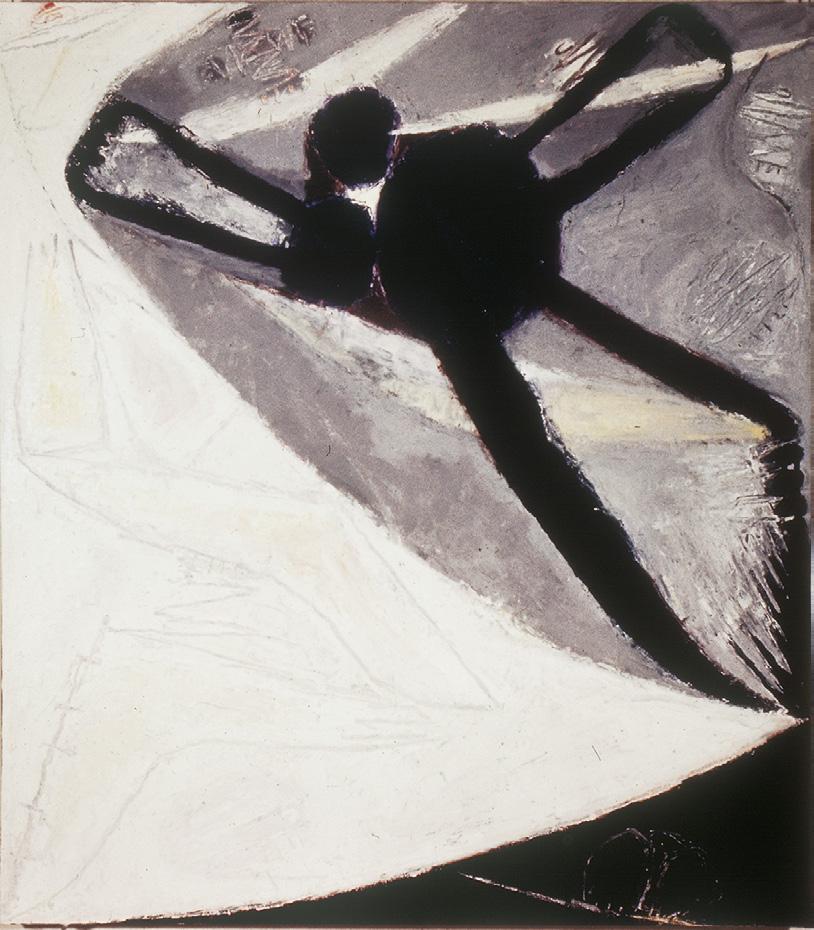

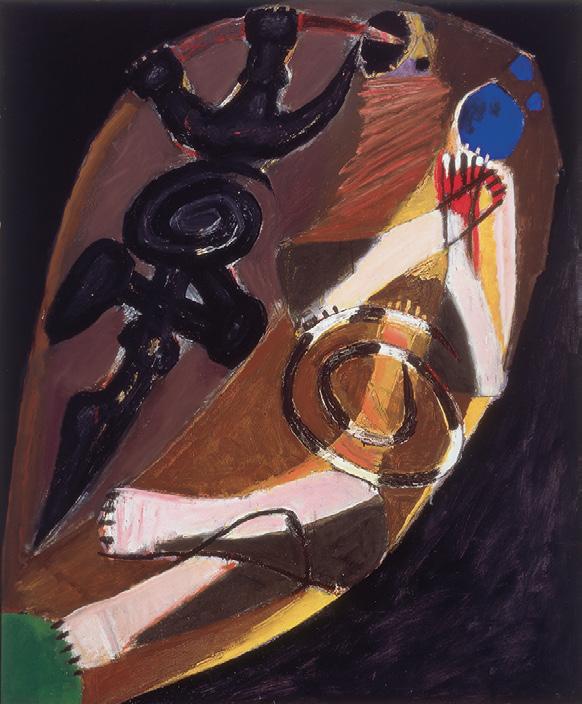

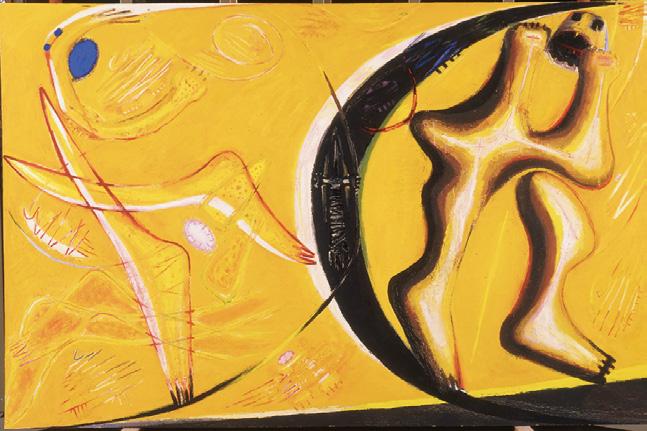

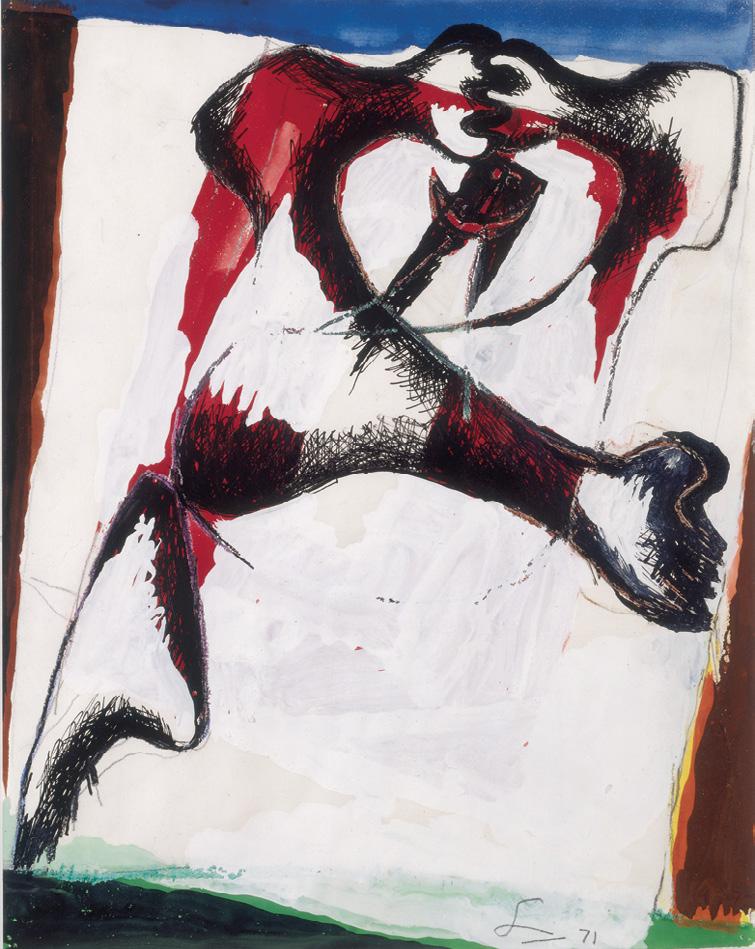

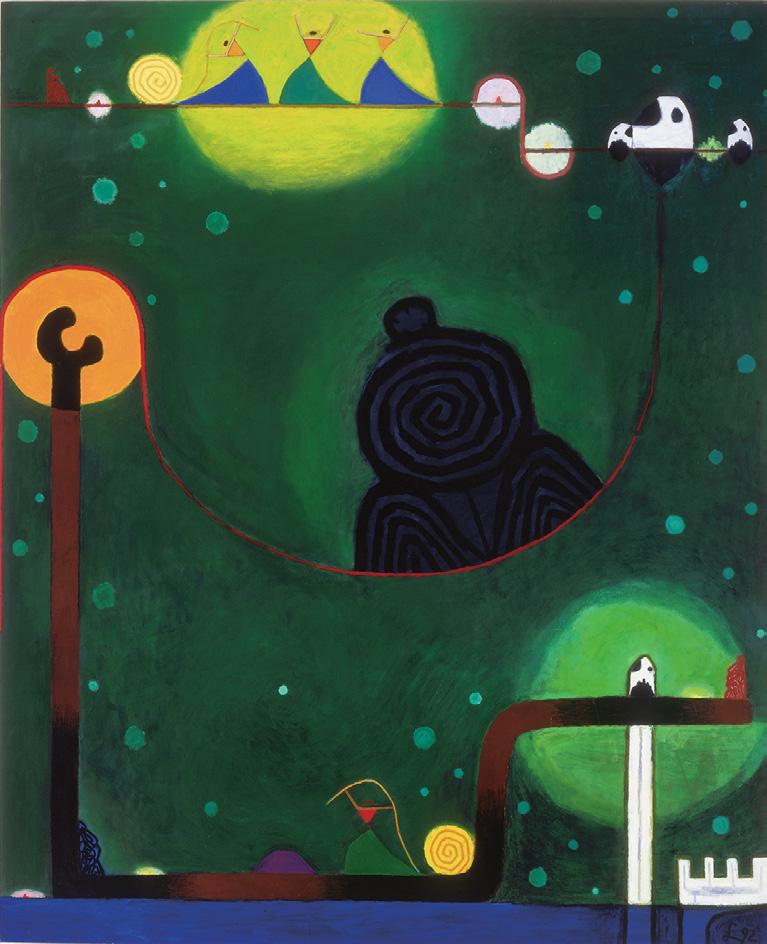

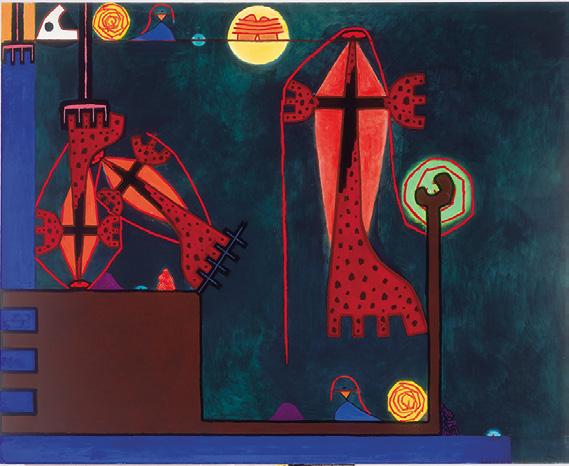

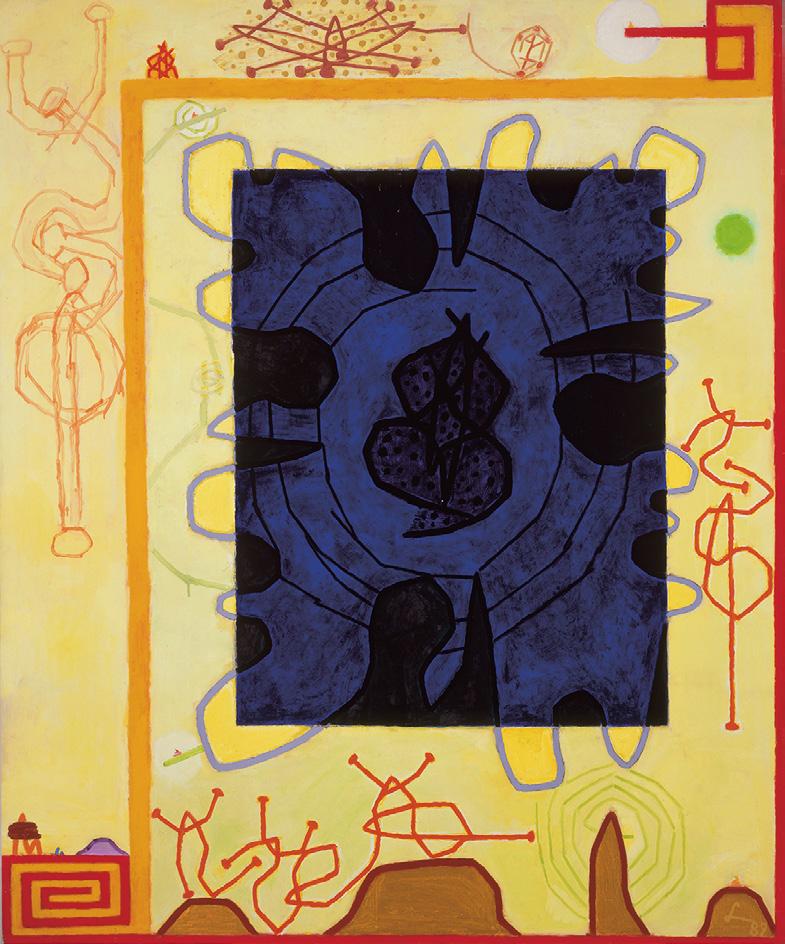

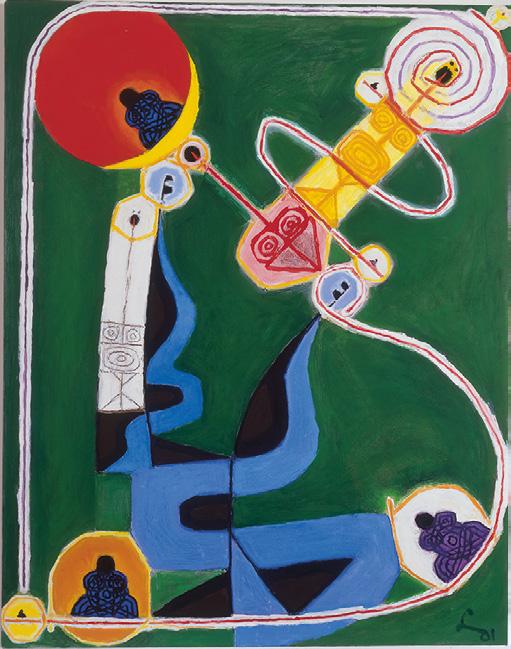

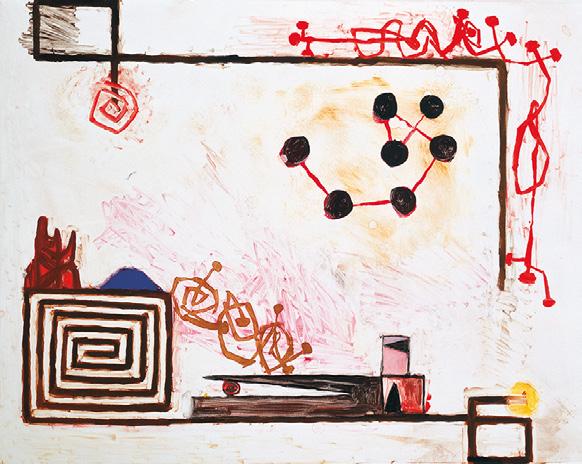

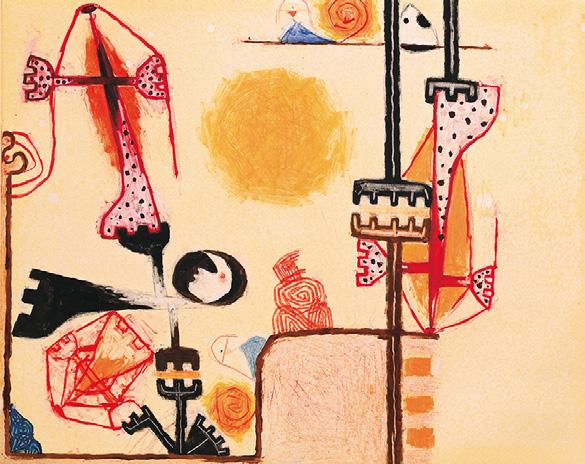

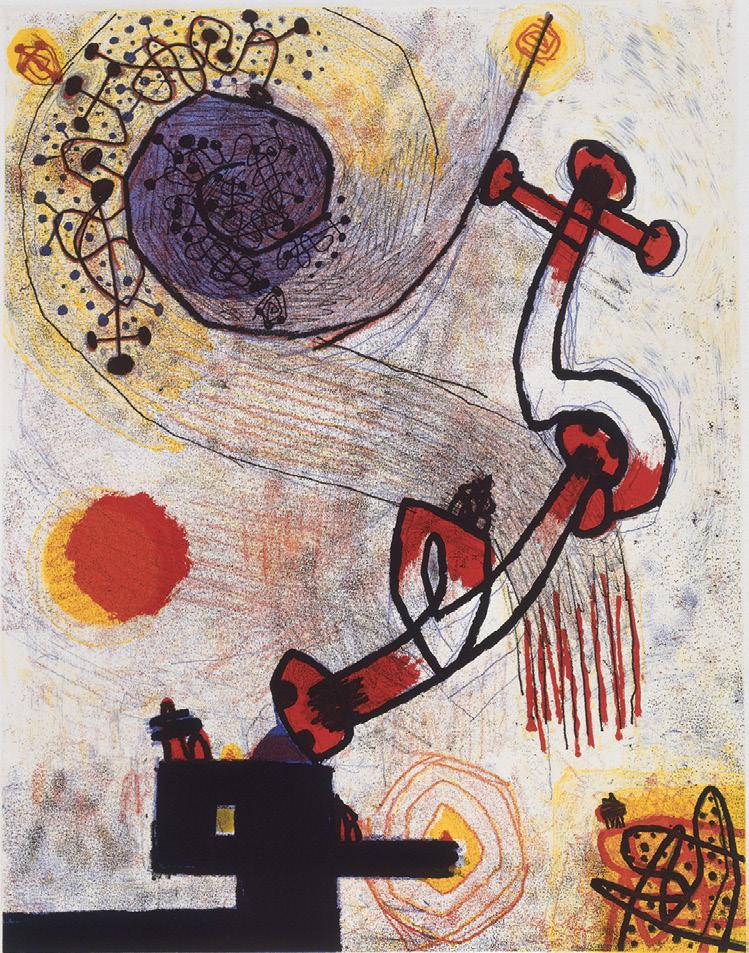

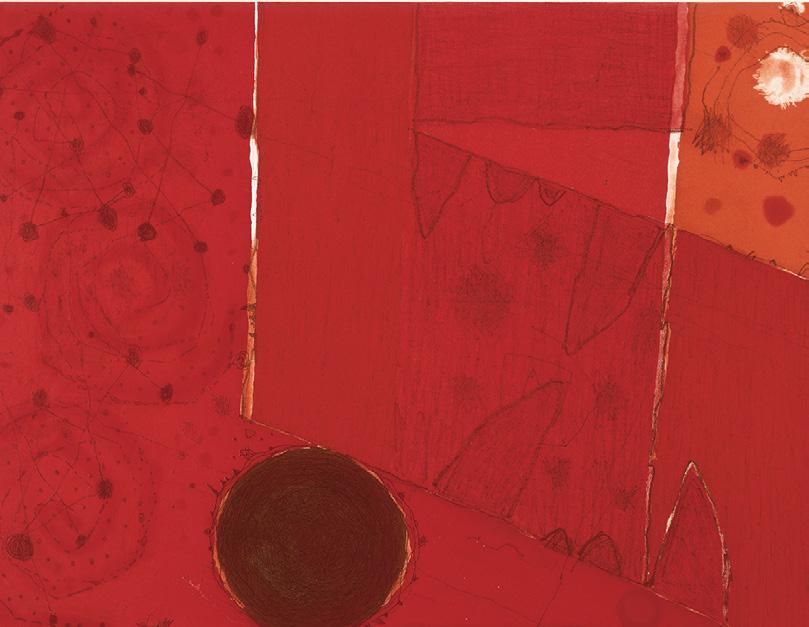

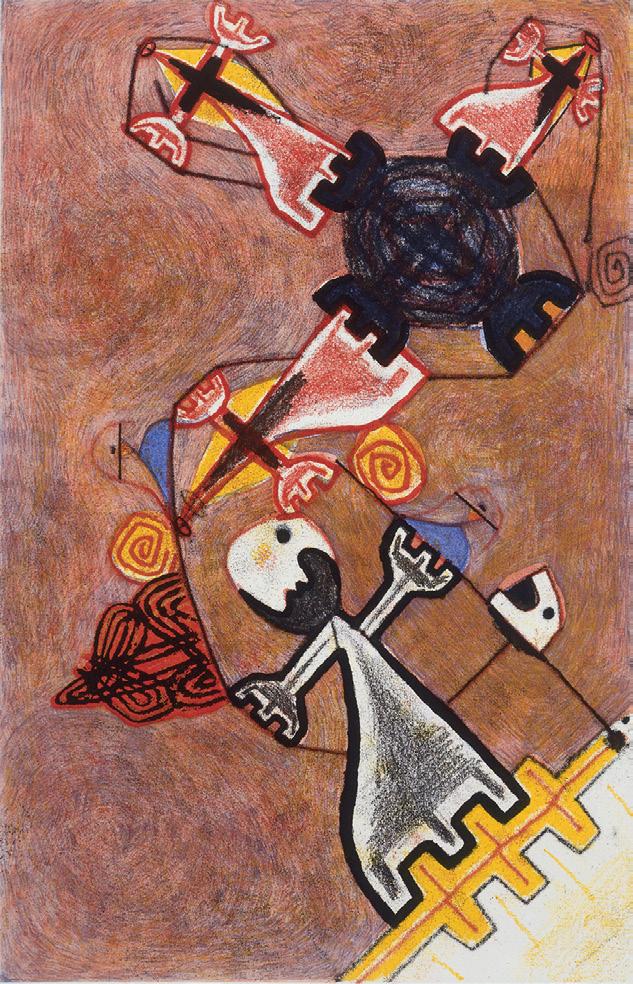

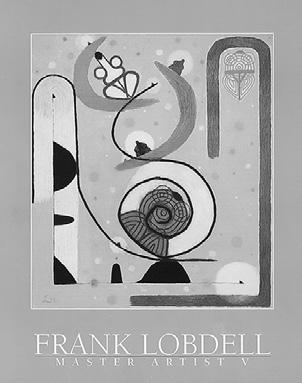

In the 1960s and 1970s, Lobdell expanded the scale and scope of his Wgures—most notably in Summer 1967 (In Memory of James Budd Dixon) and in his Dance series (1969–1971)—which now actively asserted their humanity in opposition to the threat posed by the war in Vietnam. From the 1980s to the present, he has developed a resonant new language of signs, one that suggests the primordial and the mythic are not relegated to the past, but still alive and vital in the present. Equating art and life on the most fundamental level, these recent works reconnect contemporary viewers with the eternal physical and spiritual struggle of the artist—and of humankind—for making and meaning.

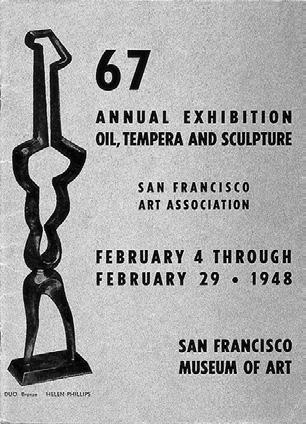

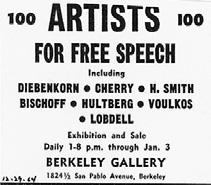

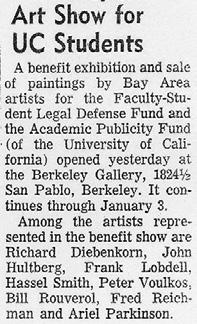

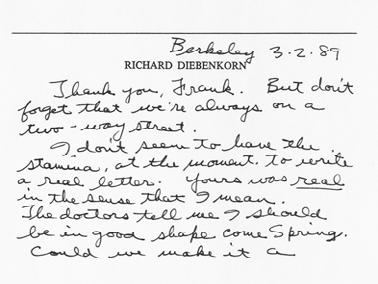

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco have a relationship with Frank Lobdell that spans his entire career. Thus it is both Wtting, and an honor, to celebrate the publication of this major monograph with a retrospective exhibition of his work. Lobdell’s Wrst interaction with our museums occurred before the merger that joined them. He participated in the invitational group exhibitions of 1947 and 1948 at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor while still a student at San Francisco’s California School of Fine Arts. The M. H. de Young Memorial Museum presented his Wrst solo exhibition in 1960, and three years later, his extraordinary Wgure drawings were included with those of his colleagues Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer BischoV, in an exhibition at the Palace of the Legion of Honor.

The Fine Arts Museums’ longstanding support of Frank Lobdell’s work is commensurate with their mission to support artists of both local and national stature. In addition to organizing the present exhibition at the Palace of the Legion of Honor, two of our curators, Timothy Anglin Burgard and Robert Flynn Johnson, are among the contributors to this catalogue, along with Walter Hopps, Bruce Nixon, Bruce Guenther, and Anthony Torres. Project coordinator Anne Kohs, editor Lorna Price, research and production coordinator Diane Roby, and designer John Hubbard along with the rest of the staV at Marquand Books deserve credit for bringing this Wrst major monograph on Lobdell to fruition.

We are pleased to acknowledge that Frank Lobdell: The Art of Making and Meaning is the Wrst exhibition to be supported by the Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Traveling Exhibitions. We also wish to acknowledge the artist’s wife, Jinx Lobdell, as well as his son Judson Lobdell, who has donated the artist’s largest and most ambitious painting, Summer 1967 (In Memory of James Budd Dixon) to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. We are also indebted to Morgan Flagg, Wayne and Betty Jean Thiebaud, Michael Hackett, Manuel Neri, and Carolyn Farris whose loyal support of Lobdell’s work has helped to make this exhibition and publication a reality. We join them in paying tribute to the unwavering integrity of Frank Lobdell’s creative expression.

Harry S. Parker

III, Director Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

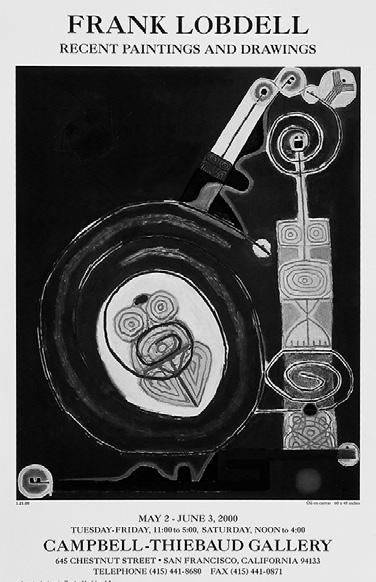

The publication of F RANK L OBDELL : T HE A RT OF M AKING AND M EANING and the series of special exhibitions that accompany it mark an important milestone in the public recognition of an American artist of the Wrst rank. A collaborative endeavor, the institutions and individuals involved have come together to celebrate and document the ongoing artistic achievement of Frank Lobdell, a preeminent member of the San Francisco Bay Area’s artist community. Though widely recognized by his peers as an “artist’s artist” and celebrated for his teaching career, Lobdell has not received the broad public recognition that his contemporaries David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, and Elmer BischoV have been granted. This handsome book, with its voluminous illustrations and scholarly essays, is intended to correct that disparity and provide a guide to the rich evolution of Lobdell’s aesthetic over the course of some sixty years of invention and innovation.

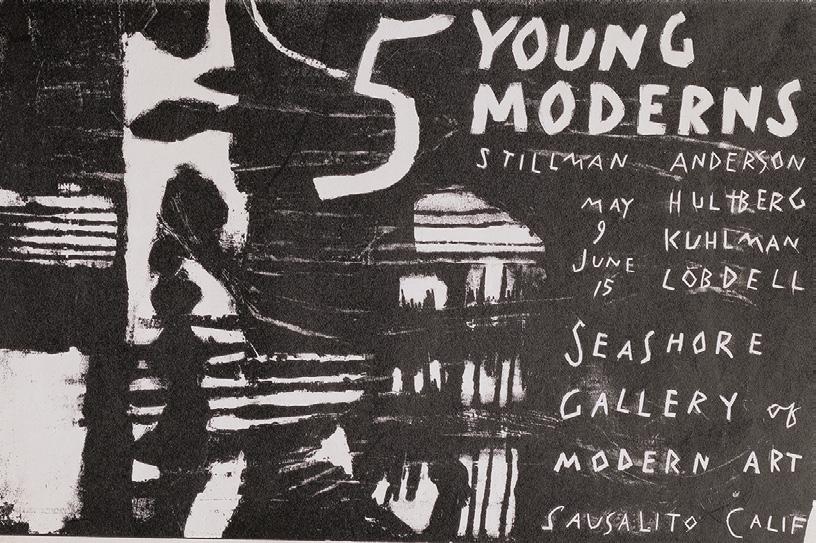

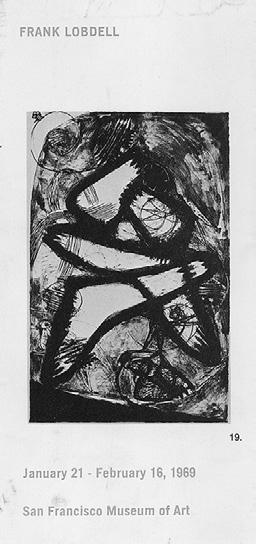

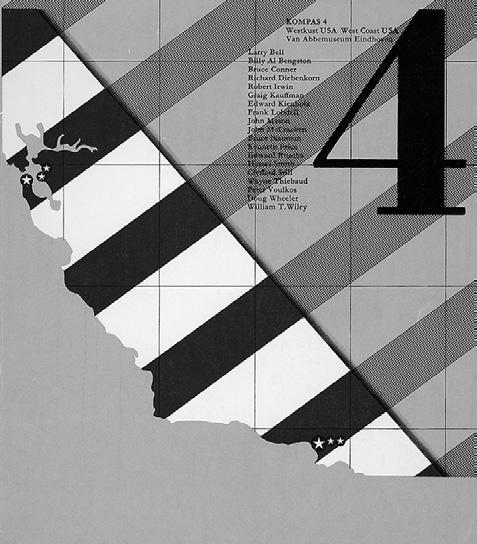

In each successive decade of his working life, Frank Lobdell has been counted as an artist whose work is essential in deWning parameters of artistic dialogue in the San Francisco Bay Area, where his reputation and stature were well established both nationally and internationally by the mid 1950s. The power of his paintings brought him widespread critical attention. Long before he would have regular gallery representation in San Francisco itself, he was exhibiting internationally. As early as 1951, his work was included in exhibition at the Petit Palais, Paris, in a group show; in 1955 he was represented in the Third Biennial of São Paulo; and in 1958, at the Osaka International Festival, Japan, as well as venues in London, Turin, and Eindhoven, including early solo exhibitions in Paris and Geneva. He also showed regularly in solo and group exhibitions in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco; in exhibitions at San Francisco’s M. H. de Young Memorial Museum and the Walker Art

Center, Minneapolis (1960); The Whitney Museum of American Art (1962); the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1964); and a major retrospective exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum (1966), among many others.

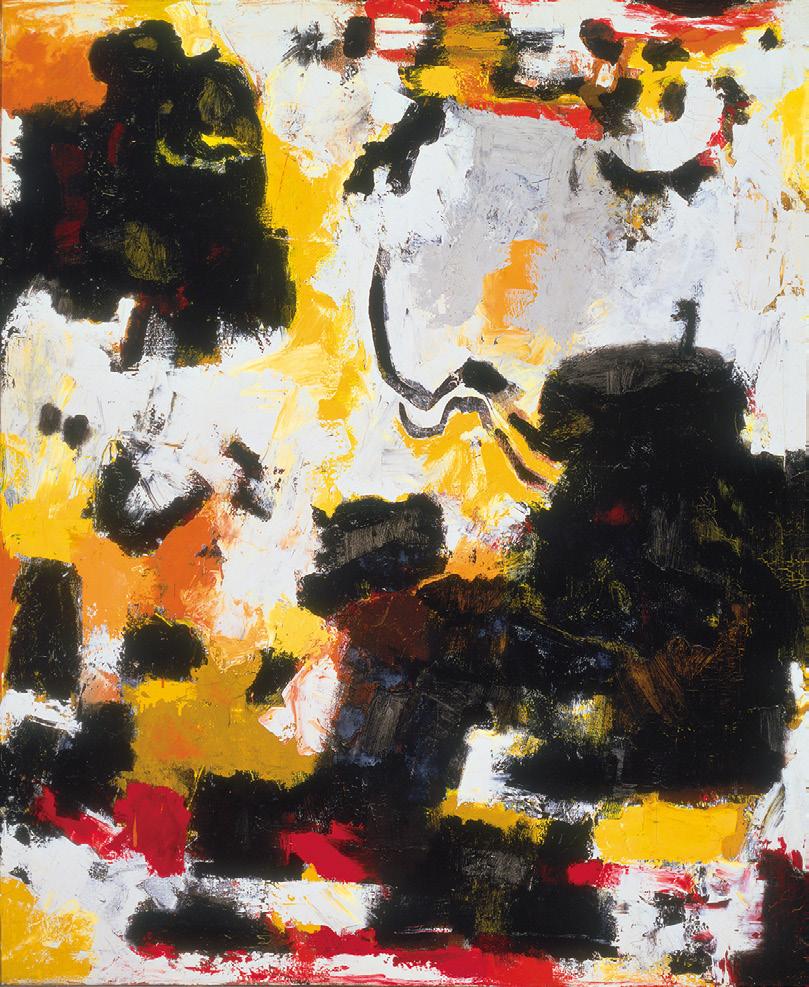

Frank Lobdell’s early abstractions of the 1940s powerfully expressed the eVects of service in World War II on his psyche. Responding to their tenor, Thomas Albright, the late San Francisco art critic, observed of them: “[There is] constant . . . evolution in Lobdell’s art . . . from a somber, sometimes tragic sense of elemental conXict to a lyrical and exalted liberation, from darkness into light.” As a student under the G.I. Bill at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), Lobdell embraced its rejection of traditional canons of still-life and Wgurative painting for an emerging paradigm of process-driven gestural abstraction: “I can’t be content with prettiness when a feeling of turmoil seems most characteristic of our times.” Nevertheless, a focus on surface and color as the building blocks of abstraction began to emerge around this time, coming into full fruition in the successive decades.

By the early 1950s, Frank Lobdell had clearly found his own voice, and his Wrst truly independent paintings emerged. Anthropomorphic references begin to appear in his ever-more-physical abstractions, reinforcing meaning and emotional connections. As with much of Lobdell’s work, the references are often suYciently personal to be opaque, yet for the viewer, recognizable enough to be provocatively troubling. Dore Ashton, New York art critic, observed of him:

[Lobdell] is one of the few San Francisco painters who have been able to take the lessons of ClyVord Still and Mark Rothko, and do something with them. [He has] developed a symbolic imagery that stays close to the myth themes that these older painters were exploring around 1946. [The symbols] . . . engender an atmosphere—a dark, almost chaotic atmosphere of beginning.

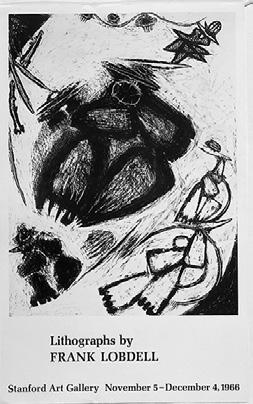

Lobdell has enjoyed long tenure as a central Wgure in the instruction of painting in the San Francisco Bay Area. He began his distinguished teaching career in 1957, by accepting an invitation to join the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts. He taught there until 1965, when he left to serve as Artistin-Residence at Stanford University. He joined the Stanford faculty in January of 1966 and taught there for the next thirty years.

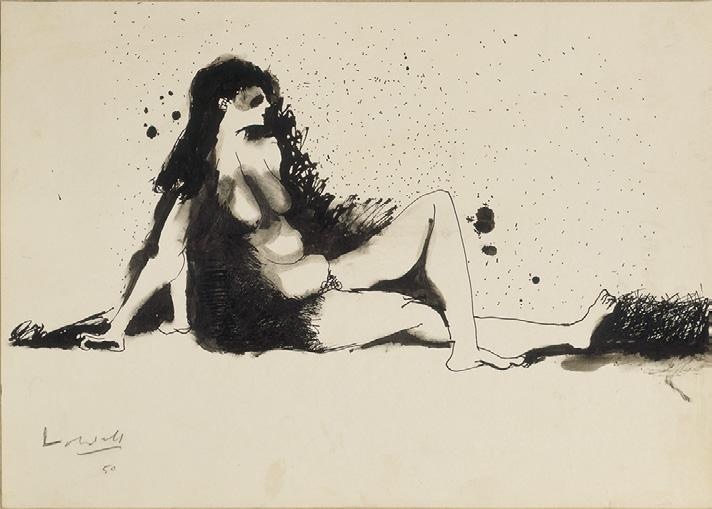

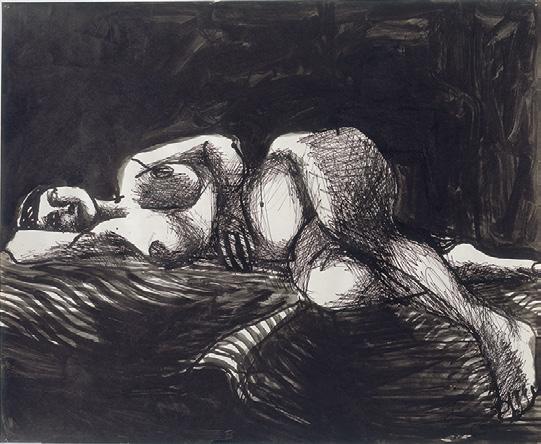

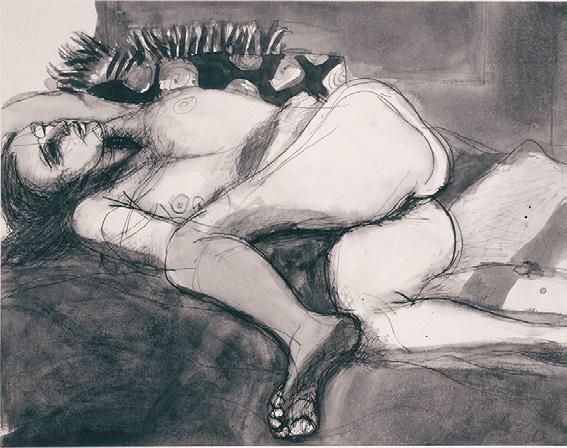

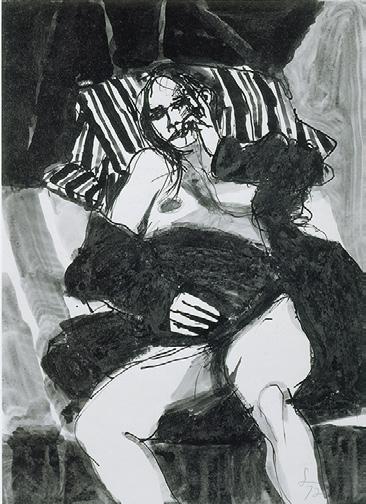

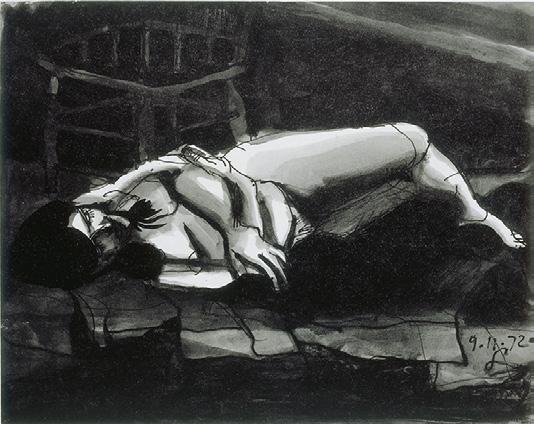

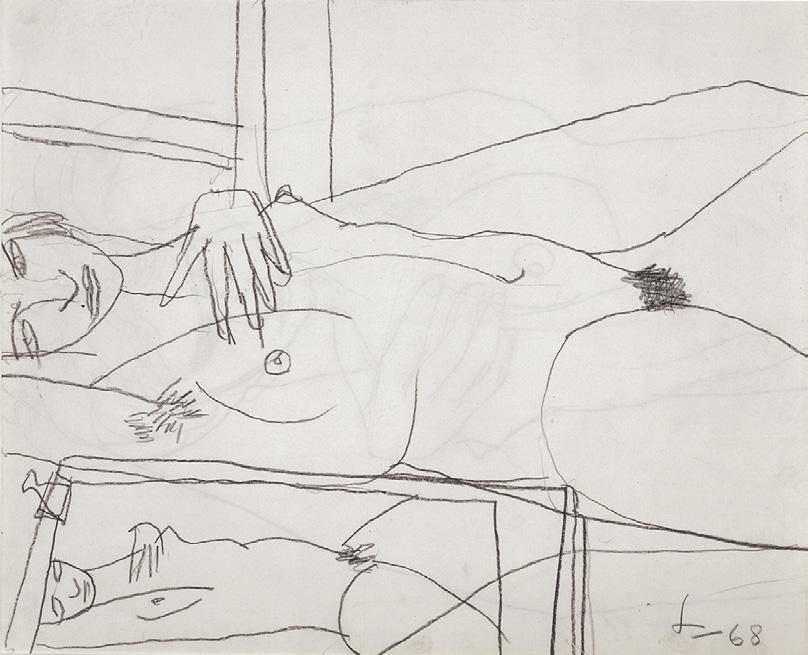

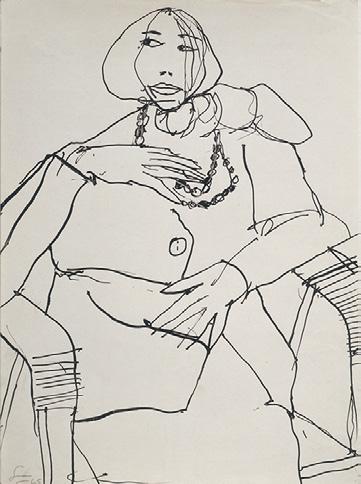

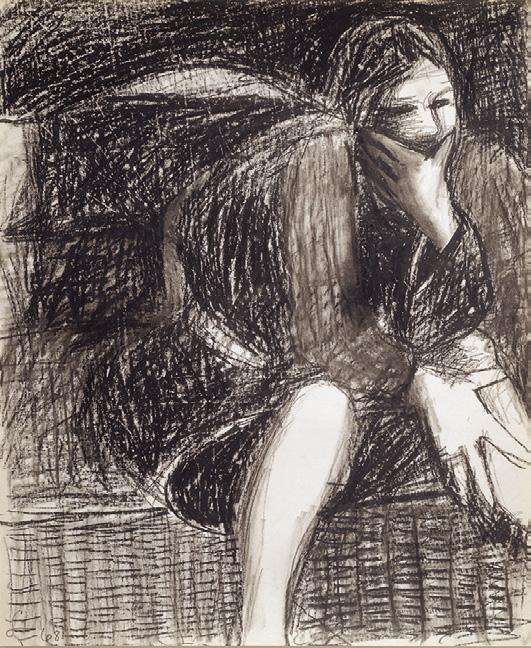

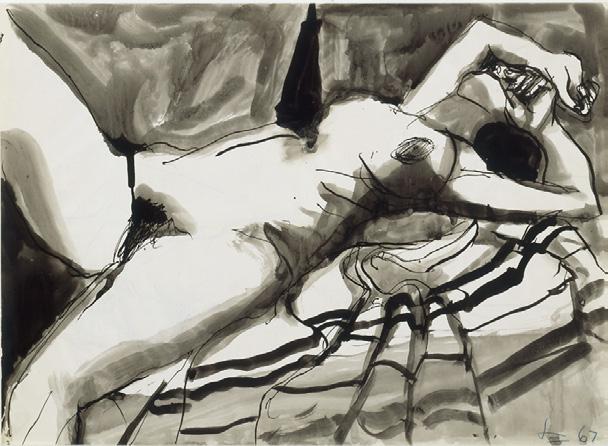

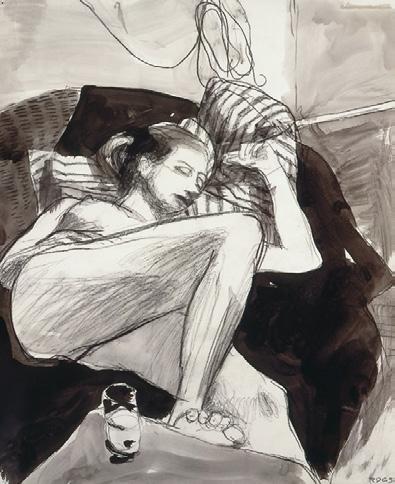

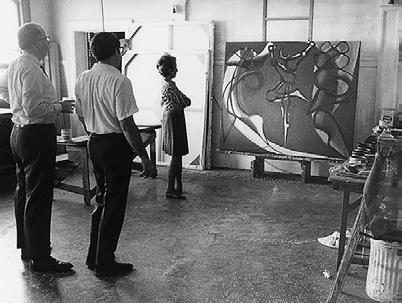

From the late 1950s to the mid 1960s, Lobdell participated in weekly Wgure-drawing sessions with his friends Diebenkorn, BischoV, and Park. After moving to Stanford in 1966, he continued the practice, drawing with fellow-instructors Nathan Oliveira, Keith Boyle, and others. Essentially an abstract artist from the beginning, in those years Lobdell used these weekly sessions as a springboard to develop a vocabulary of abstraction that was informed by a study of the human body and grounded in the formal issues of abstract expressionist gesture. His subsequent incorporation of diverse art historical references such as Francisco Goya or surrealism, coupled with direct painting techniques, further distinguished his work as a unique voice on the West Coast.

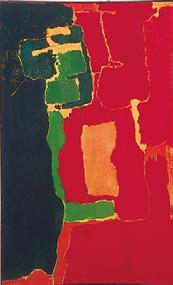

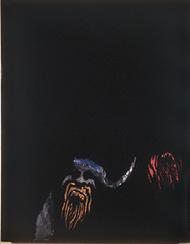

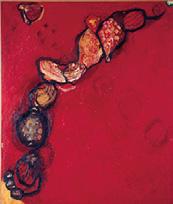

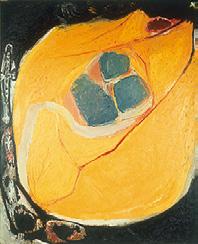

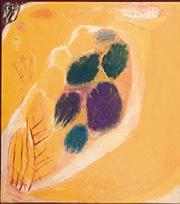

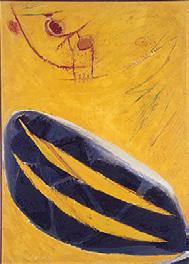

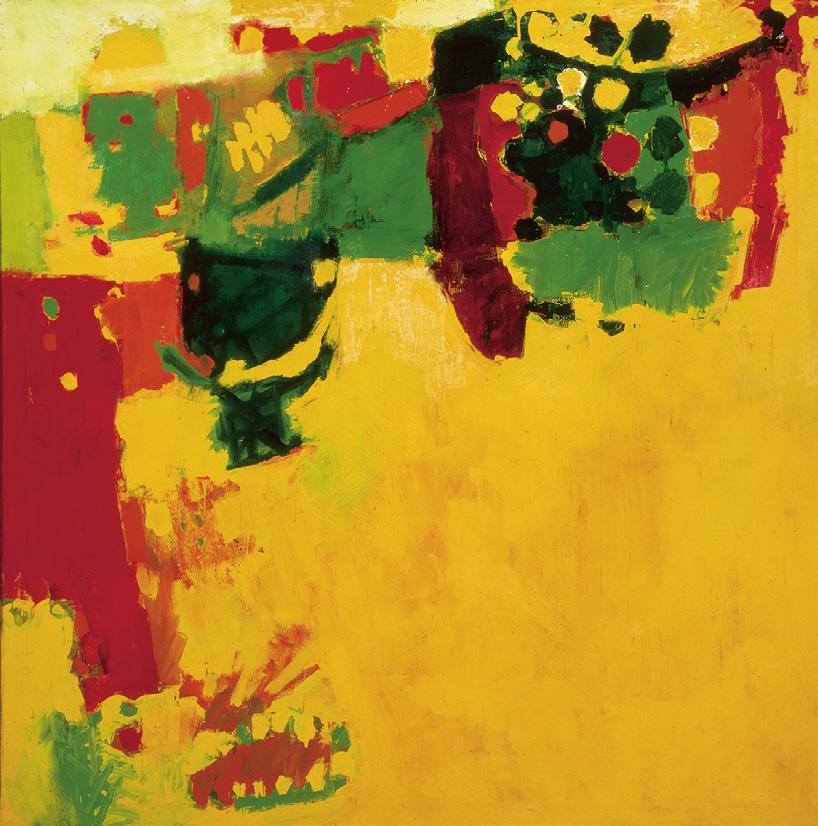

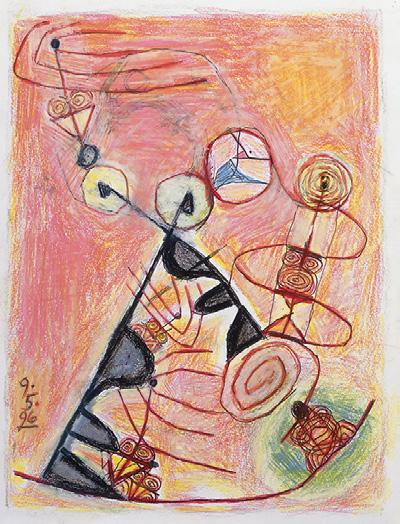

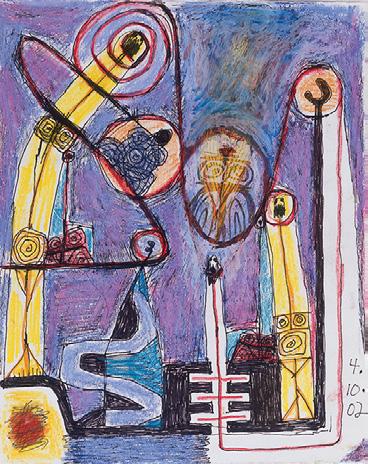

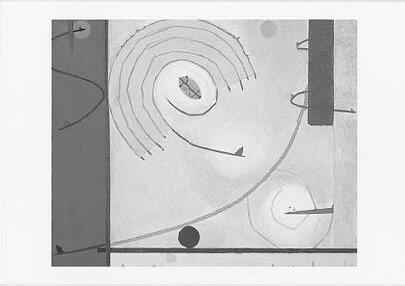

Lobdell thinks in color, and color is central to the concerns of the last twenty years of his work. It becomes increasingly saturated and jewel-like as he has perfected his technique of layering diVerent translucent colors, one upon the other, to create a much-enhanced and glowing third value. He began to juxtapose warm and cool hues early in his career, and this practice assumed a new importance in the work of the last two decades as it shifted space and emotional tenor within the paintings.

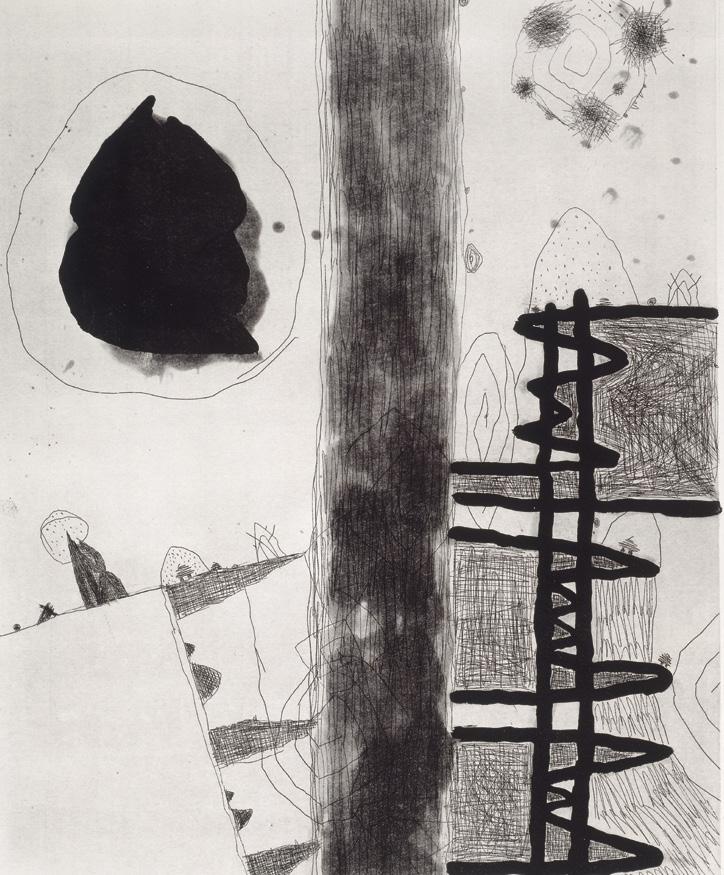

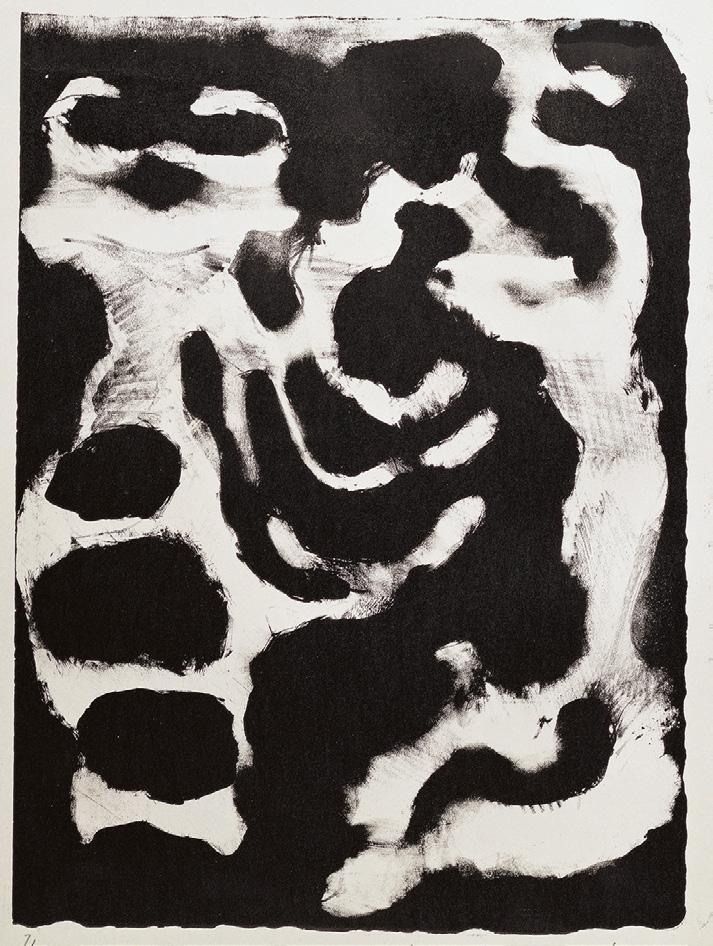

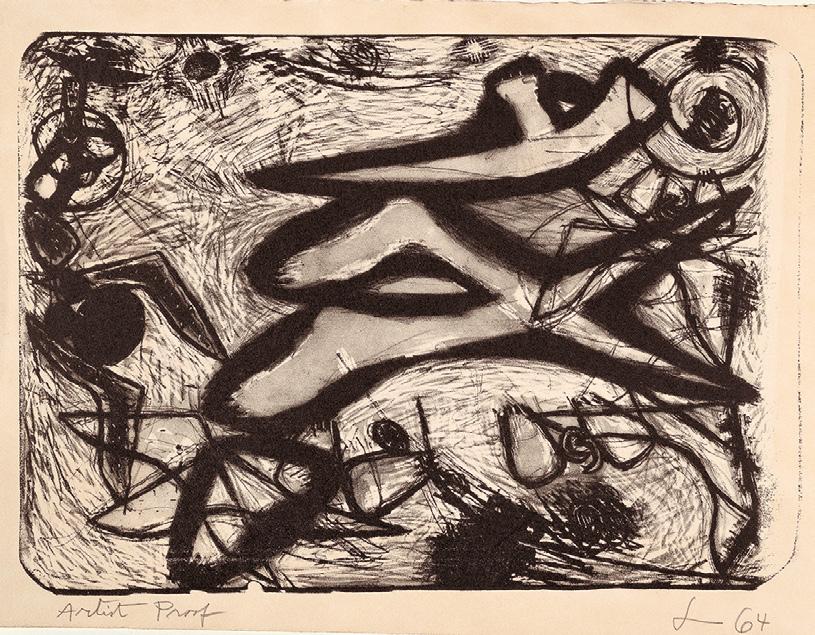

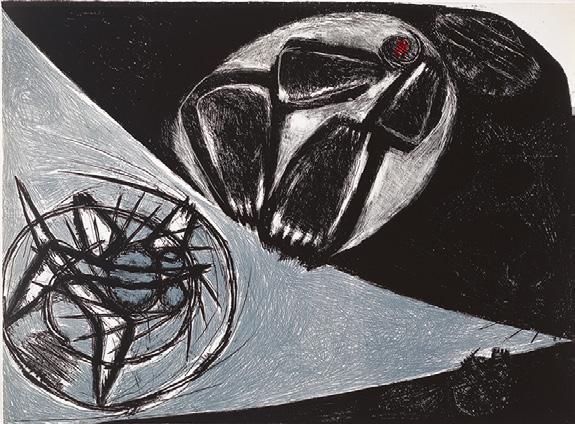

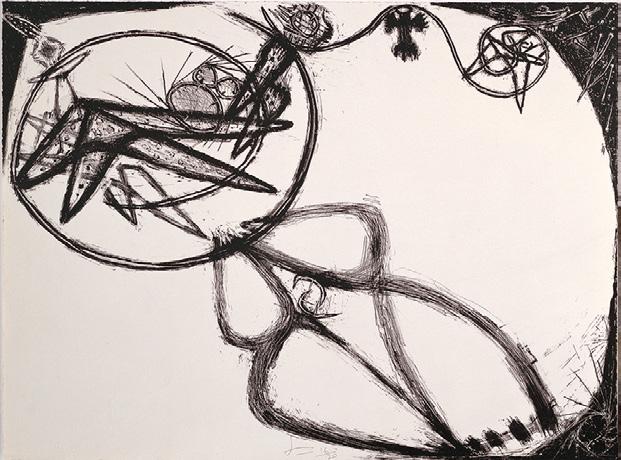

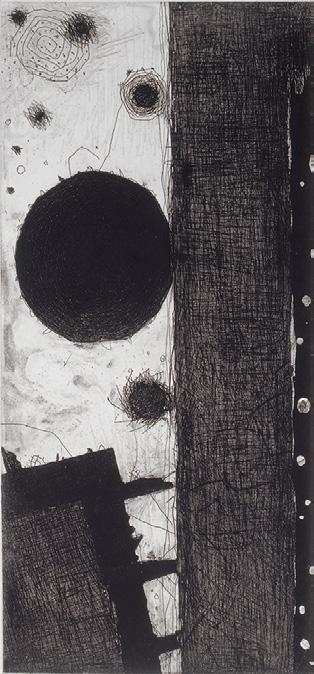

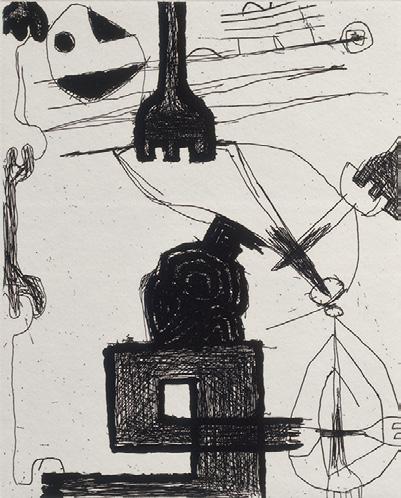

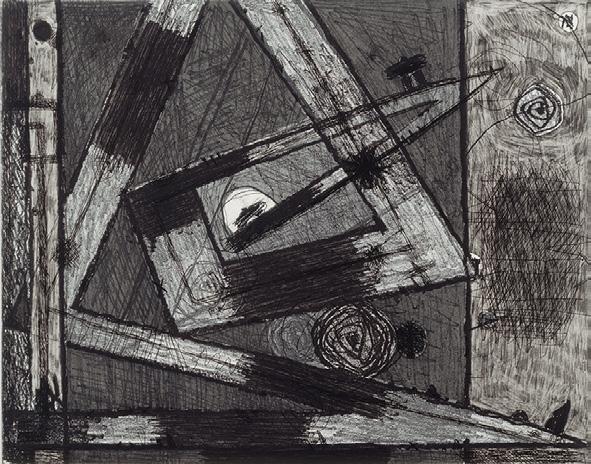

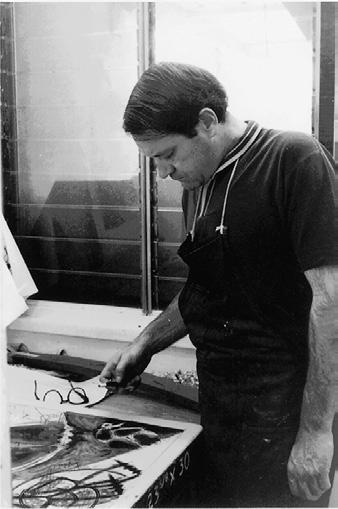

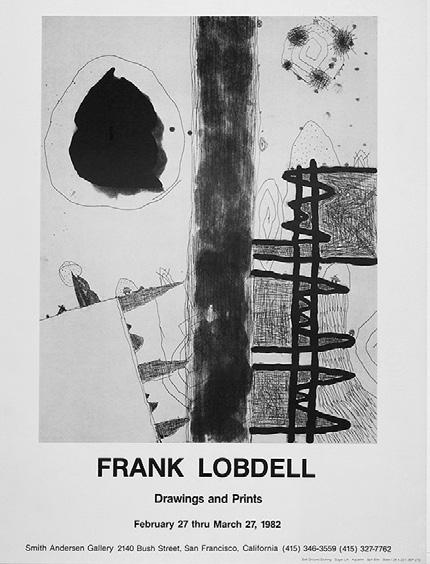

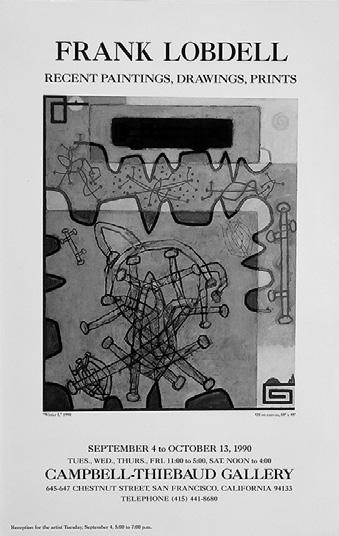

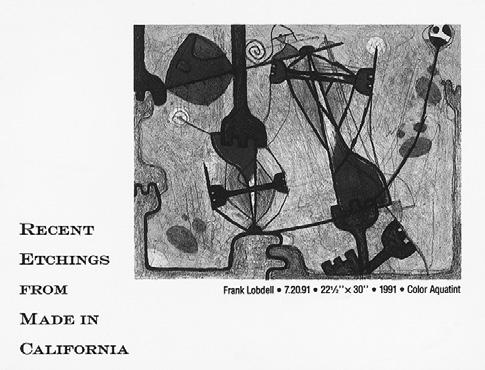

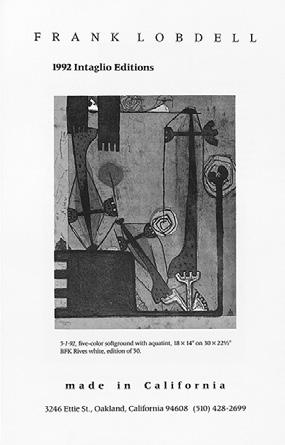

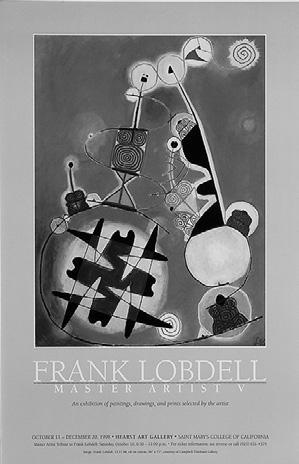

In addition to his work as a painter, Lobdell has been an avid and persistent innovator and explorer of various printmaking techniques, including lithography, etching, and monotypes. He has produced numerous editions through important associations with leading West Coast printmaking studios, including Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles; Smith Andersen Editions in Palo Alto; and master printer David Kelso of made in California, Oakland, among others.

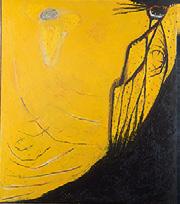

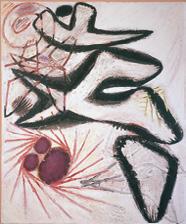

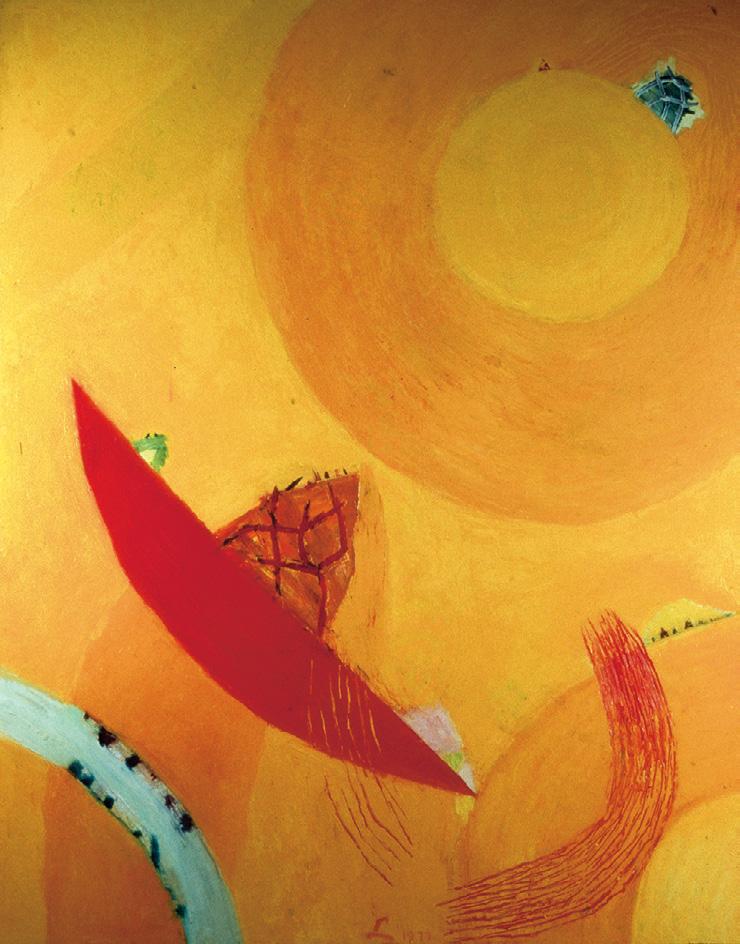

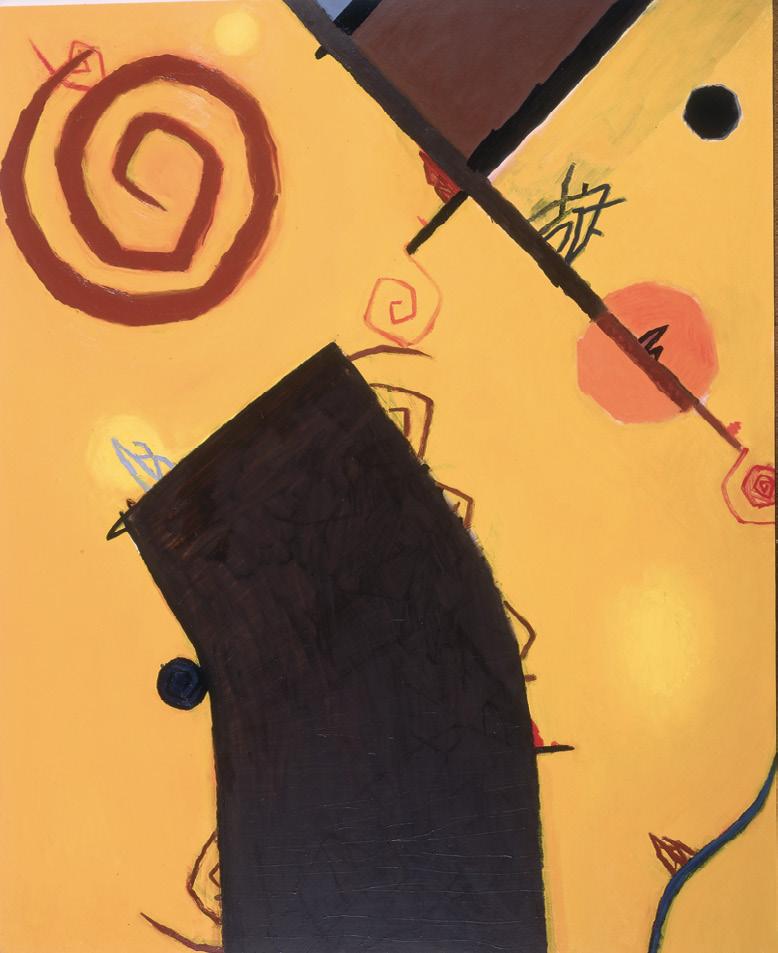

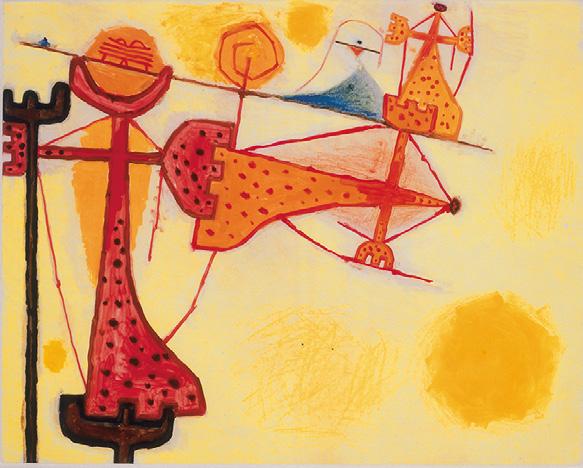

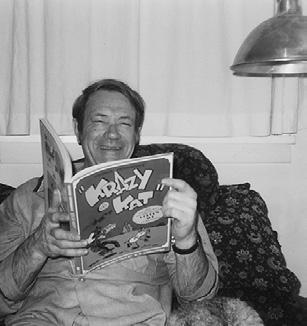

In more recent years, Frank Lobdell has been honored with a Pew Foundation Grant; awards from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, New York, including its Gold Medal for Distinguished Achievement in Painting (1988), and he was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1998. He has served as Visiting Artist/Artist in Residence at Tyler School of Art, Temple University; Yale University School of Art, and other institutions. Frank Lobdell has succeeded in creating a new and meaningful paradigm for his painting, which now embraces a universal symbolism of the sacred and the profane, in breathtakingly beautiful works of both high seriousness and play. In this most recent phase of his work, he depicts a world full of movement, activity, joy, and boundless emotion. To encounter a Lobdell painting today is to engage at the highest level in a complex dance between structure and symbolism, form and meaning. He deploys a high-key palette in dynamic compositions with an erotically charged cosmos populated with abstract Wgures whose sources range across historical world culture and the lexicon of universal symbols. He draws for imagery on West Coast Indian totems, Kilim rugs, prehistoric fertility Wgures, Mediterranean painted pottery of antiquity, Buddhist sculpture, Native American art, and Celtic knot designs.

With a timeless message of human longing and interdependence, Lobdell continues to confound expectations and engage the viewer in a dialogue of earthly pleasure and spiritual enlightenment. Always pushing the limits of his working methodology, he continues to experiment with materials, challenging himself as he devises new strategies of engagement in both painting and printmaking. It is that spirit of inquiry and deep passion that this volume and the related exhibitions celebrate.

Bruce Guenther, Chief Curator and Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Portland Art Museum, Oregon

Frank Lobdell is a member of “the greatest generation,” not because he served in World War II, but because he survived the physical and psychic scars inXicted by that war and went on to create a signiWcant body of artwork. As a G.I. Bill student (1947–50) at San Francisco’s California School of Fine Arts, he confronted the existential question of whether art retained any relevance in a world that had been permanently transformed by the Holocaust and Hiroshima. For Lobdell, the war became a Wery crucible that stripped his life and art of all illusions. Only through a lifelong artistic struggle has he been able to confront the disasters of war, to reaYrm his paciWst political ideals, and to resurrect the human Wgure as the natural locus of a humanity that seemed to have perished during that conXict.

Lobdell’s Wrst major experience with the art of war occurred in 1940, when he and Wve other students from the St. Paul School of Fine Arts drove through a blizzard to see the Museum of Modern Art’s Picasso retrospective, then on view at the Chicago Art Institute. Lobdell “camped out” at the museum for three days and later called this transformative experience a revelation, one that conWrmed his calling as an artist. Forty years later, he vividly recalled: “I felt the power of painting to really move. I wanted that power, the power to stir emotions as strongly as I was feeling the work I was looking at.”v

If the Picasso exhibition was a revelation, its principal text was the monumental Spanish Civil War painting Guernica (1937, Wg. 2). Lobdell spent an entire day studying Picasso’s apocalyptic vision of birth and destruction, life and death, and innocence and evil. The young artist was particularly struck by the innovative installation of dozens of Picasso’s related drawings and paintings, and observed, “You could read it like a book.”w Like predella panels in a Renaissance altarpiece, these independent works of art collectively augmented the

visual and visceral impact of the larger painting. PreWguring a central tenet of abstract expressionism and Lobdell’s own work, Picasso’s Guernica opus declared the process of artistic creation itself to be a meaningful act and subject. Lobdell’s strong response to Guernica also was inXuenced by the painting’s scathing political indictment of Nazi Germany and Fascist Spain for the destruction of a Spanish town and the deaths of its civilians. As a teenager, Lobdell brieXy considered enlisting in the famous Lincoln Brigade of foreign volunteers, in order to join the Spanish Republicans’ Wght against Francisco Franco’s fascists.x As a mature artist, Lobdell would later emulate Picasso’s perception of painting as a political act in his own antiwar works such as Summer 1967 (In Memory of James Budd Dixon) and the Dance series (1969–1971). But with the United States entry into World War II, Lobdell deferred his art aspirations; he was inducted into the Army in 1942.

In April of 1945, Wve years after viewing Picasso’s Guernica, Lieutenant Frank Lobdell confronted the harsh realities of war when he came upon a barn in Gardelegen, Germany, that was Wlled with the charred corpses of prisoners who had been burned alive by German soldiers. On April 13, over 1,000 concentration camp prisoners had been forced into the enormous, hay-Wlled barn, which was then set ablaze with gasoline and incendiary grenades. Several desperate prisoners scraped their Wngers down to the bone while attempting to dig under the barn doors with their bare hands. The few prisoners who managed to escape the barn were machine-gunned by the German soldiers.

When American troops arrived on the scene the next day, they found over 300 smoldering corpses in the barn, and over 700 bodies buried in an adjacent mass grave. Photographs of the massacre were published in Life magazine on May 7, 1945, and were included in an exhibition entitled Lest We Forget, which toured the United States. But this horriWc scene of “charcoal corpses” contorted by fear and by Wre, their blackened and skeletal hands futilely

grasping for escape, was already indelibly seared into Lobdell’s visual memory. Speaking of his World War II experiences, he later recalled: My identity was shaken by that experience, as I think everyone’s was. . . . Somewhere in All Quiet on the Western Front, [Erich Maria Remarque] remarks that there are no survivors. I think he’s absolutely right. No one who has been involved in one of these wars truly survives. It’ll haunt you for the rest of your life. . . . I painted my way out of a lot of this. Fortunately I had the talent to do this. I couldn’t say that I came to grips with myself except that I was no longer as anxious about a lot of experiences. Somehow the anxiety had maybe gone into the paintings. A bit therapeutic, an unloading on the canvas.y

One of these early paintings, 31 December 1948 (Wg. 1) reveals a dialogue with ClyVord Still’s work, which had been exhibited at San Francisco’s California Palace of the Legion of Honor in 1947. For Lobdell, this inXuential exhibition “hit just as hard as the Picasso show. But in a very diVerent way.”z Still’s work represented an “assault” on the dominant School of Paris aesthetic and shattered conventional conceptions of representation. Still’s work also provided a new visual vocabulary—abstract, elemental, and mythic—that resonated with the existential world view of Lobdell and his fellow war veterans. Although Lobdell never studied with Still at the School of Fine Arts, he admired the older artist’s use of abstraction as a metaphorical mediating point between personal and public narratives. Speaking of his work in terms that could be applied to many of Lobdell’s early works, Still explained:

It is like stripping down Rembrandt or Velasquez to see what an eye can do by itself, or an arm, or a head—and then going beyond to see what just the idea of an eye or an arm or a head might be. In a sense, all the paintings are self-portraits. The Wgure stands behind it all until eventually you could say it explodes across the whole canvas. But by then, of course, it’s become a whole new world. Simply by talking about it you have already begun to falsify, because you are giving names to these ideas, and the forms and colors, and textures have become something else, for which there are no words.{

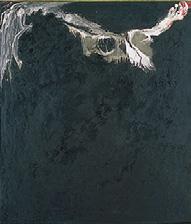

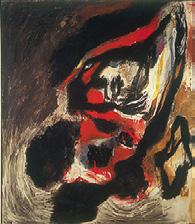

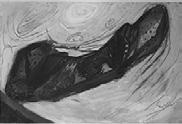

Formally, 31 December 1948 preWgures many aspects of Lobdell’s later works, including a shallow surface tension between form and space, the deWnition of forms by light or its absence, and a mutable interplay between ostensibly abstract forms and Wguration. The composition’s interlocking puzzle pieces oscillate between a clinging cohesion and a shattered fragmentation, creating a claustrophobic context that extends beyond the canvas’s borders. The agitated brush and palette-knife strokes, fraying and dissipating along their edges, resemble scars raked into the earth, and create a sense of disintegration and dislocation.

Although 31 December 1948 initially appears to be abstract, Lobdell’s explicit linkage of his early work with his traumatic wartime experiences encourages further examination. For example, the four or Wve diagonal black

forms at the upper left resemble Wngers, part of a large, blackened handprint impressed upon the canvas surface and streaked by blood red across its palm. These silhouetted, totemic forms also may be seen as individual human Wgures, teetering on the edge of an abyss. A second clawlike black hand descends from the upper right and, subverting the image’s traditional associations of divine intervention by the hand of God, appears to menace the recoiling Wgures below. A third red, white, and yellow hand form lies lifelessly across the bottom of the composition, the Xesh worn away from the joints of its three skeletal Wngers, one of which bears a ringlike band of gold.

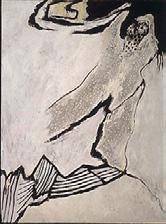

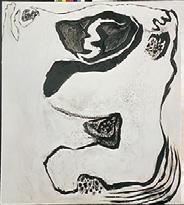

Several of Lobdell’s early postwar paintings reveal his attempts to come to terms with the atrocities committed in the barn at Gardelegen. A comparison of 17 October 1947 (Wg. 3) with 31 December 1948, however, reveals an exponential artistic evolution from an analytical and geometric dissection of the human Wgure, to an embodiment of irrational violence and overwhelming emotion—from a depiction of physical pain to the actual sensation of psychic angst. Like a solitary Auguste Rodin hand (Wg. 4), in which the expressive fragment represents the whole, Lobdell’s hands represent the graspable human fragments of an inhumane and incomprehensible whole. These brutalized, dehumanized hands not only capture the victims’ death throes—

they also seem to represent the disembodiment of humanity itself during World War II.

Lobdell, whose prewar political ideals had prompted unsuccessful attempts to enlist in the Marines and the Air Force, was deeply ambivalent about his World War II service. Describing his experience at Gardelegen, Lobdell pointedly noted that the American troops expressed outrage over the atrocities at the barn but demonstrated a relative indiVerence toward the bodies of German civilians they had seen in the town.| Lobdell’s disembodied hands, oscillating between abstraction and Wguration, appear to express this moral dilemma. They blur the distinction between the lifeless hands of the victims and the menacing hands of their executioners, and perhaps also the hands of the artist—ultimately implicating everyone in this crime against humanity:

Fascism had been defeated in a war that a lot of people felt was a worthwhile war, without, of course, realizing the other side. By the time we’d conquered Germany and Japan, we’d been reduced to using the same means. I felt that at the time. An uneasiness about a lot of this. Say, the bombing of Dresden, and the atomic bomb at Hiroshima. Mixed feelings. It saved me from the South PaciWc, and in a way it was the end of the war, but if our enemies had been terror bombing and [using] Hitler’s tactics, etc. If this had been the enemy, why we had defeated ourselves.}

Although many of Lobdell’s abstract expressionist contemporaries rejected overt Wguration, their emphasis on painting as process—a visual record of the physical and psychic traces of the artist’s hand and mind—actually elevated the individual human being’s role as the artist/creator. These personal and cultural contexts illuminate one of Lobdell’s favorite themes:

The hand is so important. This is how things are described. . . . . The main thing is to keep your hand in it, through the entire process. The image can be changed by the medium, and you get something you wouldn’t otherwise have known. . . . But it’s the hand in the end. And it has to be my hand in all of this.~

Lobdell’s use of charcoal black, crimson red, and golden yellow in 31 December 1948 inevitably evokes traditional associations with death, blood, and Wre. As in Picasso’s Guernica, or in Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810–15), the glaring contrast between white and black suggests a battle between the forces of light and darkness, reason and madness, and life and death.

A less obvious connection may be made between Lobdell’s palette and that of Rembrandt, whose Lucretia (1666, Wg. 5), in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, had made a strong impression on the young artist before the war. Rembrandt’s image of Lucretia, who has just fatally stabbed herself and hovers between life and death, emphasizes her hands (one grasping a knife and the other clutching a cord) and the startling red streak of blood that stains her bright white chemise. Rembrandt’s singular use of Xickering yellow or gold light to convey a tangible sense of humanity and spirituality is perhaps reXected in 31 December 1948, although Lobdell also raises the possibility that this spiritual light has been fanned into a hellish inferno.

The most appropriate thematic analogy is perhaps provided by another painting that Lobdell admired—Francisco Goya’s Madrid: 3rd of May, 1808 (1814, Wg. 6), which depicts the nocturnal execution of Spanish resistance Wghters by a Wring squad of French soldiers. Goya’s symbolic use of color, including the ominous black sky, the phosphorescent white shirt and gold pants of the central protagonist, and the large red pool of blood spilling from the pile of executed prisoners, appears to be echoed in 31 December 1948. Similarly, the parallel array of death-dealing riXes menacing the Spanish prisoners Wnds resonance in the menacing, clawlike black hand and recoiling Wgures of Lobdell’s painting.

More signiWcantly, Madrid: 3rd of May, 1808 illuminates the seeming contradiction between heroic humanity and ignominious death found in both paintings. The upraised-hands gestures of both Goya’s central Christlike Wgure and Lobdell’s anonymous victim are futile in the face of inevitable death, but they are also deWning moments of human transcendence. Ironically, these deWant martyrs are most alive and most human at the moment when their lives are about to be extinguished.

Like the pigmented handprints found in the neolithic cave paintings of Lascaux, France, Lobdell’s painted hands represent one of the most elemental signs of human identity and self-expression. In the context of the atrocities at Gardelegen, they provided a powerful metaphor for conveying the unthinkable, the unspeakable, and the incomprehensible. Describing his aspirations as an artist, Lobdell declared, “The truth is, you’re after something beyond words. Hence, if there are words, you haven’t done it really. If you can Wnd words for something, then you’d better get back to work. It goes beyond words.”vu In the aftermath of World War II, the Holocaust, and Hiroshima, these archetypal hands commemorated the eternal human struggle for survival and provided a touchstone for the artist’s subsequent invention of a personal sign language. But in 31 December 1948, Lobdell’s hands had already suVused the vocabulary of abstraction with a luminous humanity that slowly re-emerged, like a phoenix from its own ashes, to deWne his art.

Timothy Anglin Burgard is the Ednah Root Curator of American Art and Curator-in-Charge, American Art Department, at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Notes

1. Terry St. John interview with Frank Lobdell, San Francisco, April 8, 1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, hard copy in Frank Lobdell artist Wle, American Art Department, M. H. de Young Museum, San Francisco, p. 7.

2. Ibid., p. 9.

3. Timothy Anglin Burgard interview with Frank Lobdell, October 30, 2002.

4. Terry St. John, op. cit., p. 35.

5. Terry St. John, op. cit., p. 19.

6. ClyVord Still, quoted in Thomas Albright, “The Painted Flame,” Horizon (Nov. 1979), p. 32.

7. Timothy Anglin Burgard, op. cit.

8. Terry St. John., op. cit., p. 26.

9. Bruce Nixon, interview with Frank Lobdell, San Francisco, 2002, cited in “The Life of the Hand,” below, p. 233.

10. Terry St. John, op. cit., p. 26.

y Lucientes,

Paintings and Graphics from 1948 to 1965

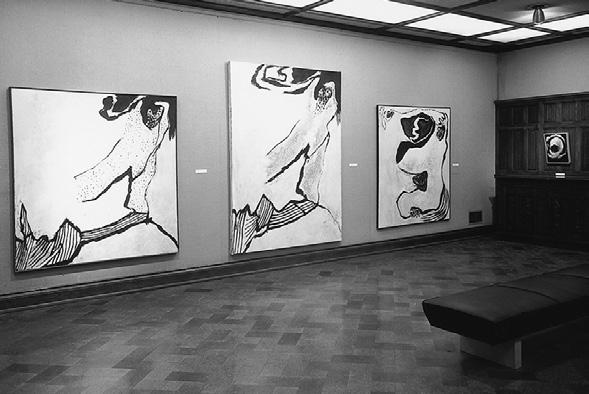

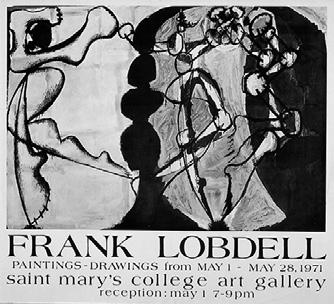

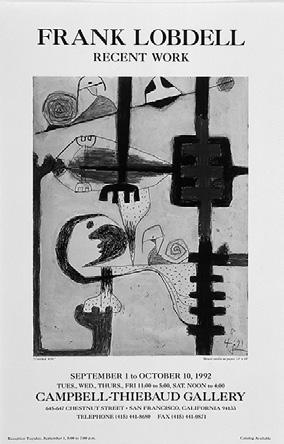

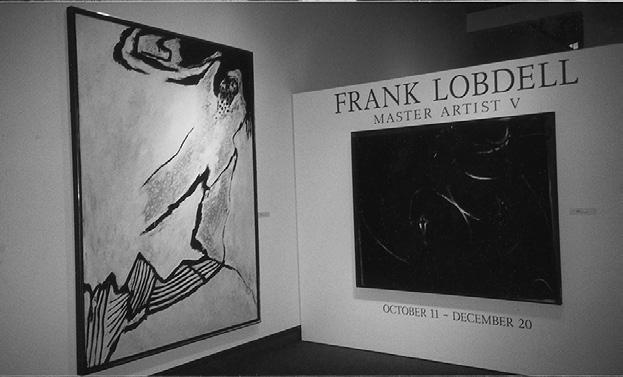

Pasadena Art Museum

March 15–April 10, 1966

Central to the art of Frank Lobdell loom the issues of mortal struggle and moral choice. His art is deeply introspective, evokes questions of human dilemma, and is far from an art of preconceived formal order, ideatic postulate, or hedonistic engagement. Confrontation with Lobdell’s art immediately reveals his commitment to an evolving, intuitive, painterly process. Each painting, for the most part heavily worked and reworked, obviously involves a prolonged process of formation. There is the sense that these paintings have been brought into being with great diYculty, and this sense of diYculty and struggle so overtly expressed determines a core of meaning in the painting. The paintings are diYcult in another sense, in the way their imagery deWes conventional identiWcation as either abstract or Wgurative. Established is a uniquely ambiguous imagery (something other than a readable, visual metaphor) completely interlocked with and revealing of the physical consequence of the paint and paint application. The speciWc conWguration of Lobdell’s imagery changes as his work evolves in time, but perhaps consistent with it is its profoundly disquieting, often anguished tenor.

In locating Lobdell’s work in the context of today’s serious advanced art, it is important to know that his Wrst fully mature work appeared in the period 1948–1950. This comes at the climactic moment in the emergence of what is implied in the phrase “New American Painting,” as associated with the work of Gorky, de Kooning, Newman, Still et al. The physical characteristics of

*This essay appeared in the catalogue Frank Lobdell: Paintings and Graphics from 1948 to 1965, published by the Pasadena Art Museum for an exhibition curated by Walter Hopps and presented at the museum March 15–April 10, 1966. The exhibition was then shown at the Stanford Art Museum, May 1–31, 1966. Reprinted by permission of Norton Simon Museum.

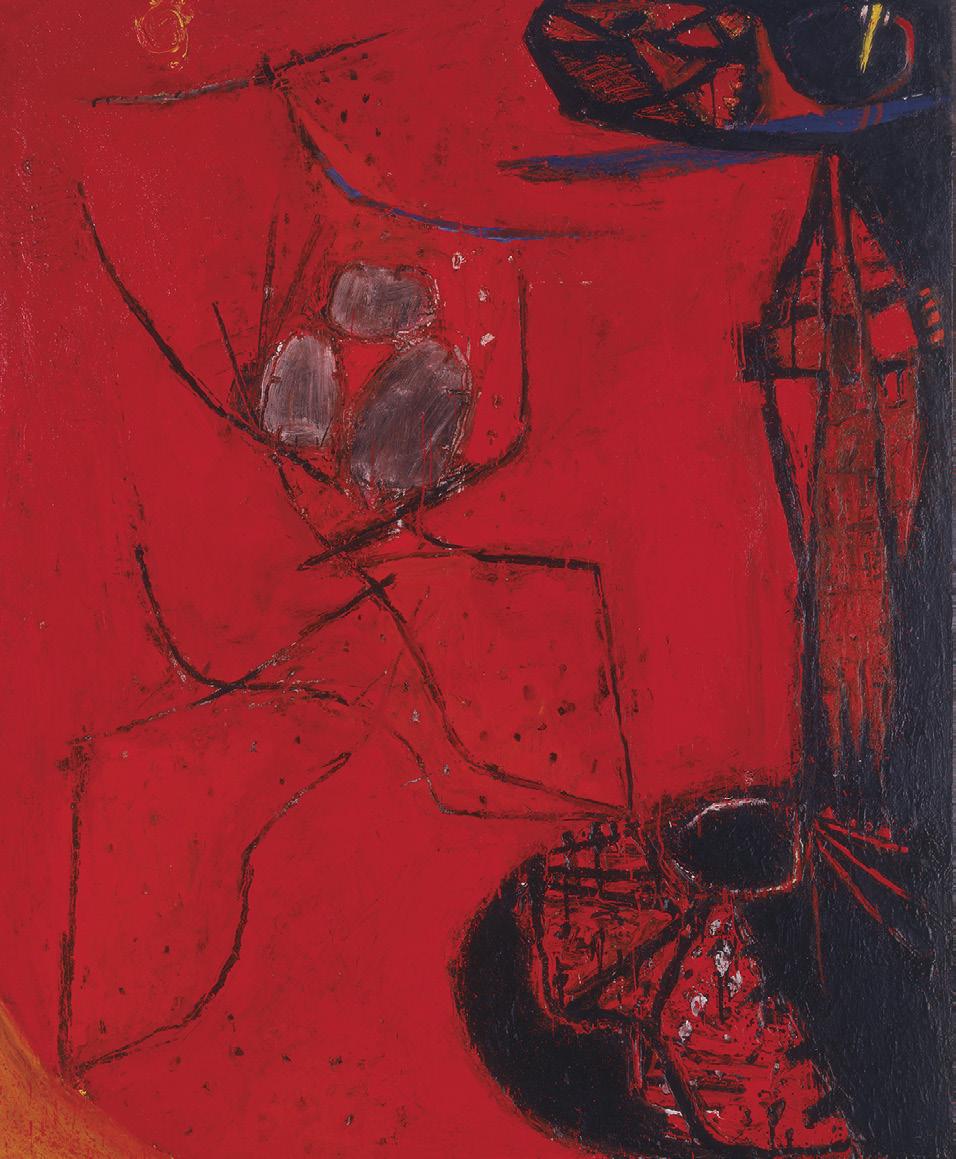

opposite Fall 1958, reproduced on the cover of the Pasadena Art Museum exhibition catalogue, 1966.

Lobdell’s painting, of course, associate it with that work of the New American Painting conventionally identiWed as abstract expressionism.

While New York City in the 1940s was unquestionably a primary center of abstract expressionist development (i.e., essentially the New York School), it is nonetheless the case that related, germinal work was emerging in the San Francisco Bay region at virtually the same time. Further, the transience of certain artists (particularly Still and Rothko) between the two cities at the time carried approaches to painting developed in the San Francisco region to New York, as well as from New York.

Lobdell’s primary home and working environment since the Second World War has been San Francisco. When the spotlight of recognition and notoriety came, for many obvious reasons, to focus upon the artists and activity in New York (pronouncedly so by 1955), Lobdell remained as a major Wgure among those few who stuck it out in San Francisco. While it does not follow that those artists working in New York City and destined to receive great notoriety necessarily expected or sought it, it does follow that those artists, such as Lobdell, remaining far from any spotlight in San Francisco markedly demonstrated their unconcern for either potential notoriety or frenetic art world involvement. Lobdell’s deliberate decision to remain in a place promising little in the way of notoriety and its material beneWts goes beyond explaining his relative obscurity ten years ago to suggest the extent to which he maintained a belief in the value of a rather rigorously independent, self-reliant role for himself as an artist.

In tracing the course of Lobdell’s life there are events to be singled out that have obvious bearing on the nature of his art. His youth was spent in the Midwest, primarily St. Paul, Minnesota, a city far from being a sophisticated center of modern art. Lobdell’s childhood preoccupation with drawing was not discouraged at home and was eventually stimulated by an unusually enlightened high school art teacher, Eugene Dana. His experience in high school triggered his desire to pursue Wne art and led him to study with Cameron Booth at the St. Paul School of Fine Arts in the late 1930s. At that time, Booth was clearly one of the few artist-teachers in the Midwest involved with any real sense of modern art.

With little important art existing in Minnesota, Chicago was the closest important center for Lobdell to see art of the past or anything approaching current activity. Unfortunately, circumstances for him were such that visiting Chicago was not easily undertaken. Lobdell had visited Chicago’s Art Institute at the time when The Museum of Modern Art’s vast Picasso exhibition was presented there. The impact of the exhibition was decisive; this was Lobdell’s Wrst encounter with a large number of great twentieth-century paintings. The curious muscular and rather brutal vitality and sophistication that mark Picasso’s painting around 1906–1910 Wnd something of a later date transformation in Lobdell’s Wnest work. It is at least clear that this aspect of Picasso aVected Lobdell far more than Picasso’s detached architectonic

structure and analytical cubism. Lobdell also came to have a great regard for Picasso’s skill in draftsmanship.

Lobdell left art school immediately after his encounter with the Picasso exhibition and began to devote his full time to painting on his own, maintaining a studio in St. Paul, and later in Minneapolis. His early independent career was interrupted by military service from 1942 to 1945. Following the war, Lobdell chose to reenter art school under the beneWts of the G.I. Bill. At one point he considered establishing himself in New York City, but personal circumstances dictated San Francisco, and he completed the program of the California School of Fine Arts.

The California School of Fine Arts has occupied a major role in the development of art in the Western United States from its founding before the turn of the century to the present. The eVect of this school, now known as the San Francisco Art Institute, was never greater than in the late 1940s following the war. Lobdell’s association with this school was of vital consequence to him during that period as a student and later, in the 1950s, as a member of its faculty.

ClyVord Still, undoubtedly the California School of Fine Arts’ greatest teacher, characterized this school in the late 1940s as far from being an ideal center for artists themselves, in that it was disorganized, naive in many of its programs and administrative functions, and often unsympathetic to the most serious teachers and students in residence. Nonetheless, Lobdell enjoyed the opportunity to work virtually on his own with what amounted to a government subsidy. Moreover, the school’s milieu tended to blur distinctions between the faculty and those mature students returned from the war, many of whom already had the beginnings of a career prior to military service. The variety of artists variously associated with the school was quite extraordinary, including such men as: Elmer BischoV, Ernest Briggs, Richard Diebenkorn, Edward Dugmore, John Hultberg, Jack JeVerson, the late David Park, Mark Rothko (during his summer session visits), Hassel Smith, Clay Spohn, and many others. The impact of Still’s art was felt throughout the school. Beyond Still’s art itself, Lobdell highly valued his exposure to what he refers to as “the weight of Still’s intellect.”

The work of certain artists of his generation, who were active in the San Francisco Bay region up until 1950 (and beyond in the case of some), contrasts sharply with the often foreboding quality of Lobdell’s art. For example, the work of Richard Diebenkorn assumed a more calm, lyrical nature. The work of Hassel Smith was characteristically involved with imagery of ironic and unpredictable wit. Sam Francis, who attended the University of California in Berkeley across the Bay, was developing an abstract expressionist approach involving a sensuous and expansive hedonism, in extremely marked contrast to Lobdell’s work. Perhaps the work of these artists was visually related, if at all, only in respect to certain general characteristics of space and scale operative in their painting. The essentially postcubist space involved a sense of

extendibility of forms beyond a limit as cropped by the canvas’s edge. Thus, critical or dramatic elements in the composition might well appear at the canvas’s edge rather than being centrally located and contained.

Lobdell visited Paris brieXy between 1950 and 1951. For him the experience turned out to be particularly unsatisfactory. The postwar artwork in Paris seemed weak and eVete in the face of its prewar tradition and in comparison with the adventurous, vigorous work he knew was being done in the U.S.

In 1951 Lobdell returned to San Francisco and soon settled in the studio, near the San Francisco waterfront on Mission Street, which he has occupied until this time. Lobdell encountered a startling situation; art activity as he had experienced it before living in Paris seemed to have collapsed. Many important artists had left the city, most of them for good. The nature of the California School of Fine Arts seemed to have changed; the lively contemporary exhibition program fostered by Jermaine MacAgy came to a standstill when she and her husband, Douglas MacAgy, the outgoing Director of the school, left the area. There remained incredibly little art life in the city apart from that maintained by Dr. Grace Morley at the San Francisco Museum of Art and that occasionally generated by artists themselves in the face of poor and diYcult circumstances. Something like a mere six private collectors and gallery dealers together scarcely provided a resourceful patronage for the art created in the area. Lobdell has characterized 1952–1953 as the dark years, and he worked in a sense of isolation that must have seemed peculiarly close to that which he had experienced in Minnesota before the war. Somewhat ironically, the interest that began to be taken in Lobdell’s work, stemming from around 1957, came from New York, Los Angeles, and Europe.

The writings of two American authors, Herman Melville and Henry David Thoreau, have preoccupied Lobdell during the period of his work in this exhibition. Without, of course, suggesting that Lobdell’s art illustrates this writing, it seems that Lobdell shares parallel concerns and somehow makes them known in his work. Such concerns, deep in the American grain, continue to haunt our thoughts.

Walter Hopps is Curator of Twentieth-Century Art at the Menil Collection in Houston, and Adjunct Senior Curator of Twentieth-Century Art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. In 1966 he was curator at the Pasadena Art Museum.

Pasadena Art Museum, March 15–April 10, 1966

The following information is reproduced from the 1966 Pasadena Art Museum catalogue for the exhibition Frank Lobdell: Paintings and Graphics from 1948 to 1965 (March 15–April 10). Images of artwork have been added if available. Titles and collections are listed as recorded in 1966; dimensions are updated. Current information on works illustrated here appears below in the List of Illustrations (p. 387).

The paintings listed here have been selected by the artist as comprising his principal body of work executed between 1945 and 1965 in the medium of oil-based pigments. Dimensions are given in inches, height preceding width. All paintings are on canvas except no. 58, which is on a Masonite panel. Those listed with (*) are unavailable for this exhibition.

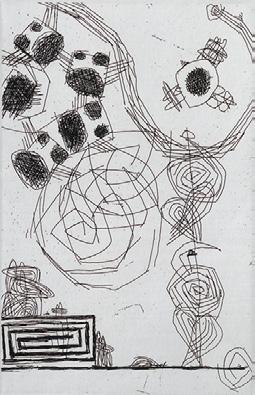

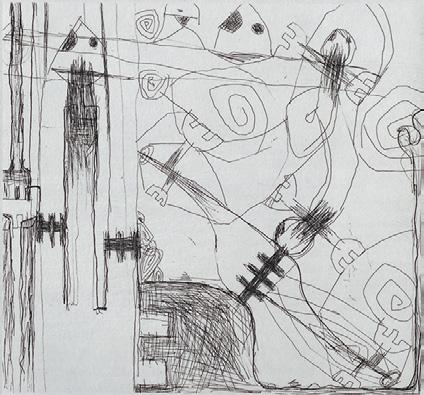

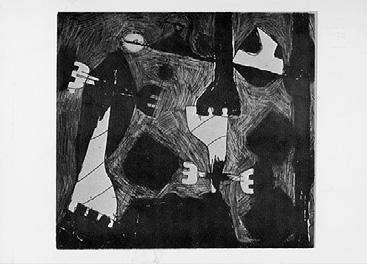

The graphic works listed here have been selected from the artist’s total output of several hundred that were produced in these same years. The drawings are executed in mixed media, as indicated, except the final entry (no. 98), which is a lithograph.

12. NOVEMBER 1953 NUMBER 1

73

14. MARCH 1954 (2) 69H × 65H

16. MARCH 1954 (4)

not illustrated

17. APRIL 1954 NUMBER 1

18. JULY 1954

19 × 14 inches

69

69

69H × 48 inches

70 × 61G inches

26. FEBRUARY 1957

(Black painting)

69G × 60G inches

Mr.

69G × 60G inches

70 × 60G inches

75

not illustrated

87G × 70 inches

Lent anonymously

34. FALL 1958

69G × 91I inches

69

70

38. APRIL 1959

70I × 74G inches

39. JUNE 1959

73G × 70 inches

40. SUMMER 1959

68G × 91 inches

Mr.

41. AUG 1959

61 × 37 inches

42. OCT 1959

48H × 49I inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

43. JULY 1960 *

39 × 31 inches (approximate)

44. SEPT 1960

73 × 49 inches

Mr. and Mrs. Harris Newmark, Los Angeles

45. OCT 1960

48 × 44 inches Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles

not illustrated not illustrated

not illustrated

46. FALL 1960 *

85H × 69I inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

not illustrated not illustrated

47. FEBRUARY 1961

61H × 70 inches

James A. Michener Foundation Collection, Allentown Art Museum

48. MARCH 1961

63 × 70 inches

Mr. and Mrs. Gifford Phillips, Santa Monica

56. SUMMER 1962

69I × 97G inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

57. 3 OCT 1962

30 × 24 inches

58. ASCENT (Red) 13 OCT 1962

72I × 48I inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

59. DARK PRESENCE (Yellow) 3 JAN

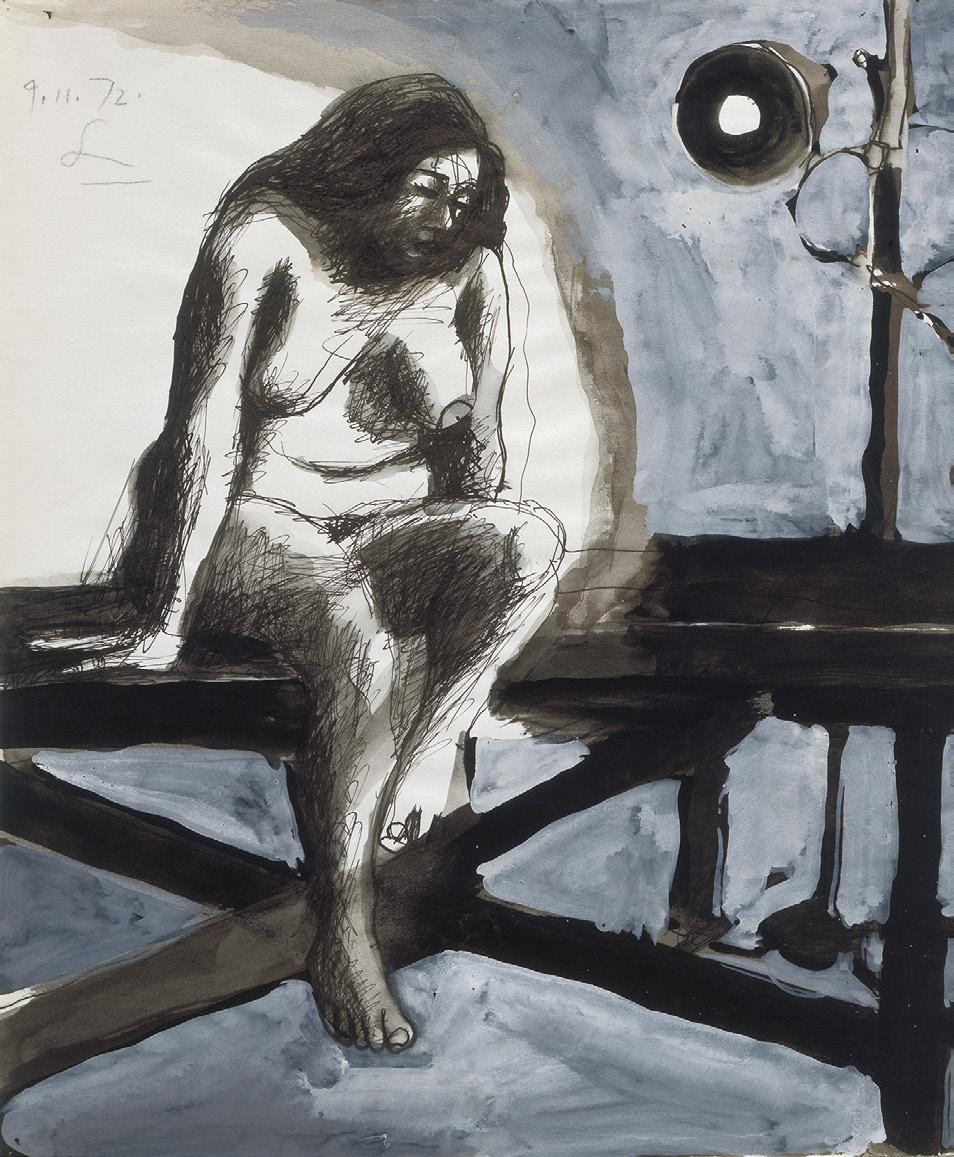

97G × 69I inches

60. FEB 1963

62H × 69M inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City 1963

61. DARK PRESENCE III (Yellow)

61H × 69I inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

62. DARK PRESENCE (White) 20 MARCH

70H × 60H inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

NOV 1964 60 × 50 inches

JUNE 1964

60J × 49M inches

70. MAY 1965

57 × 47H inches

71. SUMMER 1965

83K × 69 inches

72. OCT 1965

57 × 43 inches

74. Untitled 1958 Gouache and ink on paper

9J × 14 inches

Mrs. Albert Levinson, Los Angeles

75. Drawing 7/4/58

Gouache, ink and collage on paper

18 × 24 inches

Mr. and Mrs. Robert A. Rowan, Pasadena

76. Untitled Gouache and ink on paper 9 × 14 inches

Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles

77. Untitled Gouache and ink on paper

13L × 11 inches

Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles

78. Untitled Gouache, ink and pencil on paper

14M × 20G inches

Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles

79.

14I × 20H inches

Los Angeles

15G × 20 inches

83. A 2

Crayon and pencil on cardboard 8 × 14 inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

16K × 13G inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

7H × 15 inches

84.

Crayon and pencil on cardboard 8 × 14 inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City not illustrated not illustrated not illustrated not illustrated not illustrated not illustrated not illustrated

85. Untitled #22

Gouache and ink on paper 15 × 17I inches

86. Untitled #19

Gouache and pencil on paper 14 × 17 inches

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City

11I × 17I inches

11I × 17I inches

17

17

Martha

17

Martha

Gallery, New York City not illustrated

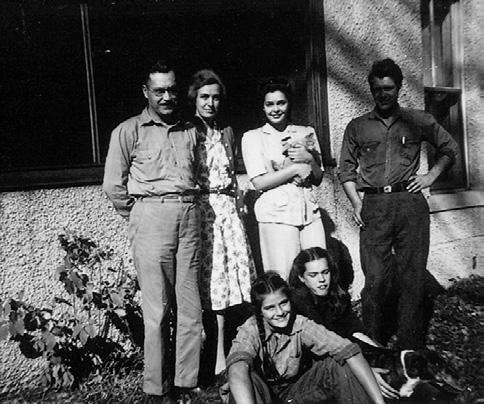

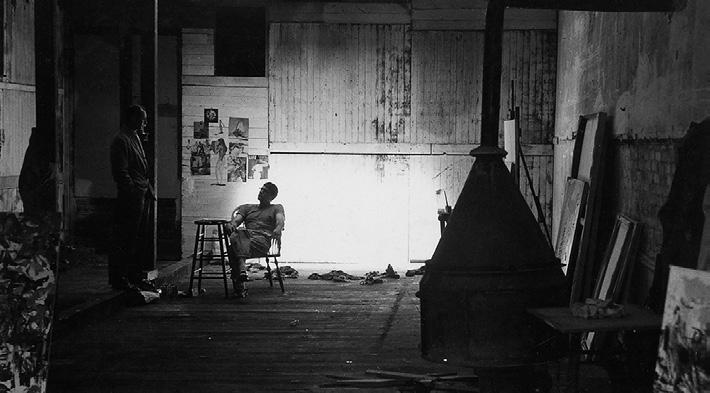

When Frank Lobdell arrived in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1946, recently married and less than a year out of the Army, he soon found himself in the company of a small group of artists fervent in their pursuit of the new American abstraction. Their center of gravity was the California School of Fine Arts—now the San Francisco Art Institute—a rambling, old Mission-style building collected around a fortresslike tower on the slopes of Russian Hill, and most of the other artists Lobdell met there were much like himself, young veterans funding their studies with the G.I. Bill. Few were native to the city. Many of them had discovered it while journeying to and from the PaciWc front, and then they returned, drawn to its balmy weather, the glistening coastal light, and the silent, creeping fog banks that cloaked the city in briny mists, which transformed the nighttime streets into a spectral tableau, to the North Beach clubs where a nascent jazz revival was already underway, and to the gregarious world of the saloons and coVeehouses—a city close to the landscape that surrounded it on every side, with an easy, relaxed atmosphere far diVerent from the metropolitan centers of the East Coast. For the Wrst time, too, the study of art represented a realistic alternative to a conventional college education, and to conventional social and professional ambitions—something that had a powerful appeal for men whose youth had come to an end amid the destructive sprawl of global warfare. Art oVered itself as a practice into which they could direct their experiences: the self-reXexive conditions of abstraction promised a means of exploring a sense of existence that literally deWed description. And the school had risen to meet this need, with Douglas MacAgy, a new director whose handpicked instructors were in most cases no more than a few years older than the students and just as enthusiastic about the emerging progressive art.

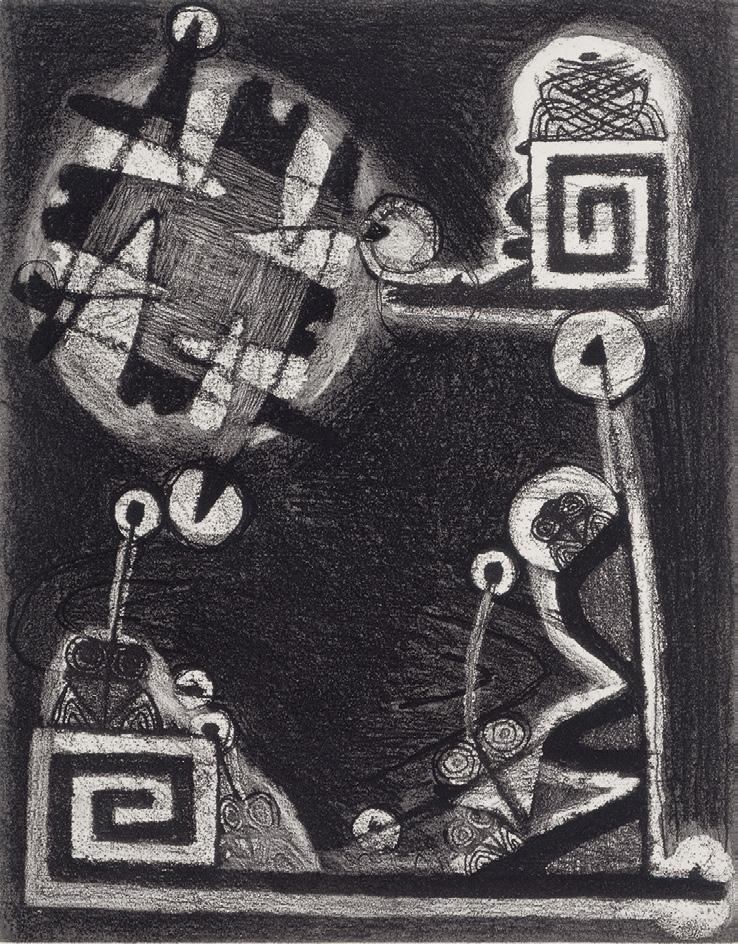

Bruce Nixon

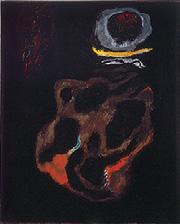

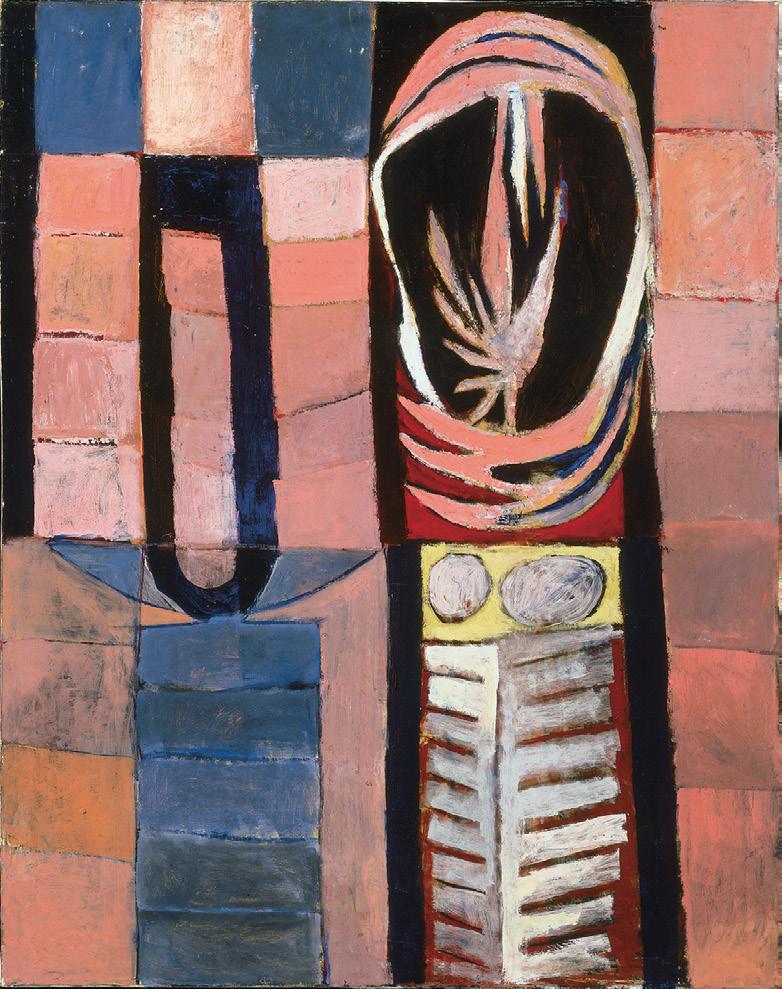

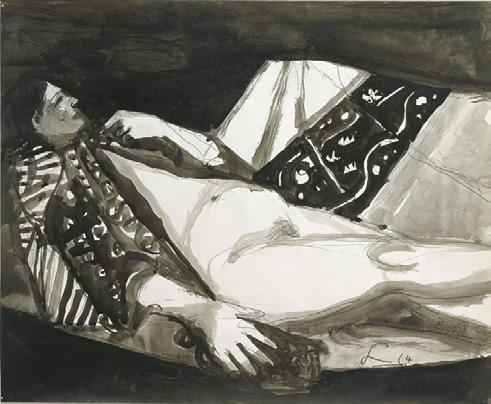

opposite 1. June 1964

Like many artists whose working lives have been similarly long and productive, Lobdell’s can be arranged into a discernible sequence of stages, even if they do not always assume a neat or outwardly logical order. But his career rightly begins in the late 1940s with his embrace of abstract expressionism, in which he recognized that painting might provide a lifelong arena of individualized inquiry, a place where he could, indeed, be entirely himself. Later phases of his career, particularly the complex body of work that began during the mid-1970s, may be more far-reaching in their signiWcance, but Lobdell was occupied from the start with the ideas that have engaged him throughout his career. One sees, for example, a fascination with the exchanges that occur when invented forms are placed in the various kinds of spaces that can be created upon painted canvas; these spaces may allude to “real” spaces in an interrogative way but should never be confused with them, since one of Lobdell’s subjects, the origin and nature of meaning, is inseparable from his conception of the work of art as a controlled, intensely personal site whose uncertain relationship to the real world is very much to the point.

A trait that distinguishes the human from other species is its will—or perhaps more accurately, its compulsion—to generate meaning from forms and signs. We are a reading species, and so we depend upon systems of representation to make sense of our experience of the world. The extent to which ‘meaning’ is collective or individual, general or speciWc, intrinsic or invented, is another of Lobdell’s concerns, and we often Wnd him working in the overlap between Welds of possibility. Inquiry into the conditions of meaning and the ways in which visual information may be garnished with cultural signiWcance is not new, of course, nor is Lobdell the only artist to have recognized that abstraction oVered tremendous potential as a method of contemplating it— whether as self-dramatization, as an open-ended, nonspeciWc visual form, or simply as a diVerent kind of representation. But he approached the task with considerable originality, and he has gone his own way, resisting abstract expressionism’s tendencies during the 1950s toward an increasingly vigorous generality of reference in materials and application.

With unXagging diligence, Lobdell instead absorbed a wide range of images from both art and nonart sources as he went about shaping his own Xexible spatial environments and a lexicon of forms with which to populate them— forms that have remained resistant to conventional symbolic associations. Over time, these forms would take on lives of their own, as they were absorbed into the gradual, systematic evolution that has been pervasive throughout the work itself. In many artists, such patient, deliberate production would extend the promise of revealed meaning, but Lobdell avoids presumptions of this sort. In questions concerning the human condition, he has no deWnitive answers; indeed, the questions themselves may be no more than illusions. It was as if he had seized upon the most promising visual ideas of the day, drawn from the surrealist-derived imagery of Joan Miró, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and William Baziotes, and intensiWed their activities upon the canvas, pushing them as hard and as far as he could, until he crossed into a territory that was utterly, recognizably, his own. He never felt a need to reduce his imagery. The deployment of signage in early abstract expressionism, which tempered its

auratic visual presence with a provocative ambiguity, had moved him. Rather than abandon it or permit it to be subsumed in the reWnements of the modernist canvas, he wondered where else it might lead and what additional accomplishments awaited it, and then he set about Wnding out.

The direction of Lobdell’s late phase is announced as early as the mid1960s, in the magisterial paintings Summer 1967 (In Memory of James Budd Dixon) and Summer 1968, but the conditions of his career may be as much a result of his decision to remain in the Bay Area as they are a matter of temperament—though the determination to separate himself from the center of the art world should also be regarded as temperamental. He kept abreast of events, but was under no pressure to submit his work to the prevailing doctrines of late modernism. He knew that the appearance of Wgural imagery in his work would encounter little, if any, disapproval in a region in which boundaries between abstraction and Wguration had never been clearly Wxed: so it was that the Wgure as Wgure appeared on his canvases during the early 1950s, and there it has remained, in one form or another, ever since. Immense shifts have occurred, of course. The functionality of the Wgure, which is such a distinctive aspect of the canvases of the 1950s and early 1960s, falls away as the artist begins developing idiomatic Wgural forms whose correspondence with the human body is no longer readily apparent, forms that refuse to abide by the familiar traditions of Wgurative meaning in art.

In essence, Lobdell has devoted himself to the creation and expansion of his own visual vocabulary, one to which he—and possibly only he—has full access. He has constructed a wonderland of his own, and as we go about interpreting what we encounter there, the work holds a mirror to the human imagination and to the array of procedures with which we go about assembling meaning. We will look for meaning, of course. We can hardly prevent ourselves from approaching the canvas as a vehicle of symbolic imagery. Along the way, however, careful observation of the machinery of interpretation may be explanatory, not because it provides any particular answers but because it unhinges the very possibility of absolute meaning or immutable truth.

Still, in Lobdell’s mind, the evolution of his imagery has been toward sign, not symbol; more precisely, it has moved away from symbol, seeking an escape from the symbolic. In common usage, ‘symbol’ and ‘sign’ are virtually interchangeable, but for Lobdell, ‘sign’ carries the implication of neutrality: it is a signiWer that refers to nothing other than itself. It is free of reXexive associations, which bestows a certain kind of availability. The symbol, on the other hand, is by deWnition referential, relying upon its connections to the established themes of a collective culture for successful application in the work of art: broad cultural agreements regarding the ‘meaning’ of the image constitute the basis for archetypal forms, literary allusion, the presentation of readily apprehensible thematic content, and so on. These distinctions of terminology acquired signiWcance for Lobdell during the 1950s and again in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he discovered that overtly Wgurative elements, with their inevitable symbolic inXections, tend to direct the reading process along predictable, well-established channels of interpretation, an experience that demonstrated the limitations of the symbolic within the context of his own

speciWc concerns. Reliance upon conventions inevitably bound the work to dominant themes in the culture; at the very least, it required an acquiescence to cultural narratives of which Lobdell was highly skeptical, or in which he did not believe at all. At the same time, his Werce independence would not allow him to submit his work to the familiar rituals of rebellion and critique, which would be just as compromising in the end. He sought instead a path of his own.

From this perspective, Lobdell’s career can also be regarded as an investigation into the diVerences between symbol and sign, and why those diVerences are of such importance. In transitional paintings such as Summer 1977, Winter 1979, Fall 1980, and Spring 1982, we witness the force with which he penetrates the symbolic and then casts it aside. He turns to signage in its stead, his own signage: the sign as the initial moment in the life of the symbol, its chrysalis state, prior to cultural internalization and thus to the establishment of thematic identity that occurs as meaning begins to gather around it. Each of his signs has its own history, certainly, but we can never be sure of its full range of reference for the artist, or if a precise catalog of reference even exists. Lobdell is not in the business of self-expression, which would only impose a further determinant upon the work.

As a narrative—and it is that—the prodigious Xow of images from Lobdell’s studio is a kind of theater, with the canvas as a stage. The work is not simply artiWce, however, any more than it is simply presentational, a mode of illustration. In the end, Lobdell’s signs, regardless of their meaning, or their lack of it, belong to the world because they are in the world and can exist nowhere else. Perhaps they are a little uneasy about this, and long for a certainty that will always elude them. Then, too, they must operate against the instincts of a culture highly skilled at generating symbols and meanings of its own—often cynical, self-serving ones. Meanwhile, on the level of the individual painting, Lobdell struggles toward the moment that satisWes his eye. Each painting seeks that moment for itself, and the originality of the imagery simply assures that his eye will recognize that moment when it arrives.

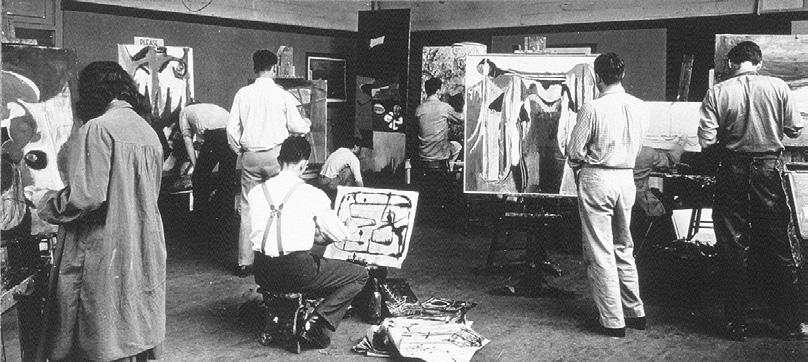

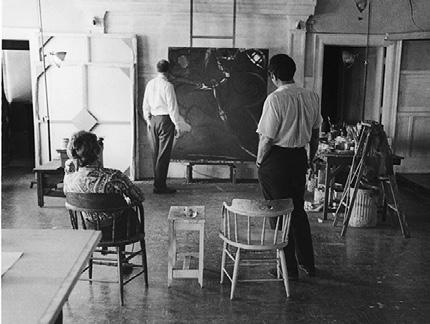

An old black-and-white photograph taken in one of the studios at the California School of Fine Arts during the late 1940s provides a rare view of a class during that era. A number of students can be seen from behind as they labor at their easels. Neither a model nor an instructor is in evidence, and most of the paintings could be described as variations upon the characteristic local abstraction of the era. One of the students is Frank Lobdell, who has stepped back from a large, cluttered image that vaguely recalls a Picassoesque automatism—the mobile line that creates forms which are then revised with patterns of color. Picasso was still a preeminent Wgure for many young American artists, who responded to his restless, protean outpouring of forms and images. Lobdell himself had traveled by automobile to Chicago during the winter of 1940, while he was still a student at the St. Paul School of Fine Arts in Minnesota, to see an exhibition of Picasso’s work at the Chicago Art Institute, where he found himself transWxed by Guernica (1937). It occupied the far wall of a long gallery otherwise devoted to studies and

smaller canvases related to the painting, appearing with the force of revelation amid the Wres of war in Europe.

Lobdell would continue to draw information from Picasso’s work for many years to come, but that is getting ahead of the story. For the time being, with the war so close in memory, eVorts to extend a local surrealism derived from Picasso and other European models had become increasingly problematic— the style was not exhausted so much as burdened by prewar aYliations that now seemed all but irrelevant—and Lobdell’s own diYculty is evident in the tangled imagery of the painting before him. This one is a struggle, but it is a struggle against the persistence of direct inXuence. One senses that Lobdell has recognized the deeper problem before him, and although he eventually chose to work through rather than abandon his sources, the painting in this photograph seems to encapsulate the situation of the moment. Painters in New York had experienced a similar conXict after launching themselves during the late 1930s and early 1940s from various surrealist models, but even before the end of the decade, they had found their answer in greater visual simplicity and clarity of intention; this resolution can be seen as an underlying motive in Rothko’s hovering rectangles and Gottlieb’s bursts, Robert Motherwell’s vast ovoid shapes, and the monochrome canvases of Barnett Newman, with their towering, unequivocal objecthood and frank acknowledgement of the viewer before them. But Lobdell was laboring in much diVerent company, and he would arrive at some crucial answers late in the summer of 1947, when he went to see an exhibition of thirteen paintings by ClyVord Still at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, a museum devoted largely to

historical European art in a low, windswept Beaux-Arts building overlooking the Golden Gate.

Still was an instructor at CSFA at the time, having been hired the previous year, and his imperious manner, his outspoken views on abstract painting, and the high-Xown, messianic rhetoric with which he expressed them had already created factions within the art school. He had been in the Bay Area earlier in the decade, employed in the defense industry, and his work appeared in a museum there for the Wrst time in 1943, apparently without much local impact. Four years later, circumstances had greatly changed, and because so many artists were aVected by it in one way or another, the 1947 exhibition is now regarded as a watershed event in San Francisco’s emergence as a center of abstract expressionism.

But Lobdell did not like what he saw, at least not at Wrst. The crusty surfaces of Still’s paintings, built from dark earth tones applied with a palette knife, seemed crude and deliberately opaque, and he was determined to reject them. More than a half-century later, he recalled: “All of this painting was an assault on what I had developed, an assault on my inXuences up to that point. Color in Still was raw. The paint was raw. But I was so anxious to protect my investment in French art that I went back a dozen times, trying to Wnd a Xaw, a reason to put this stuV down. Then one night I was working on a canvas in my studio at Sausalito and the next thing I knew, there was some of that ragged edge, some of that color, in my painting. And I realized I’d been had. It woke me up. It was like an irritation, getting in the way of something I felt comfortable with.”

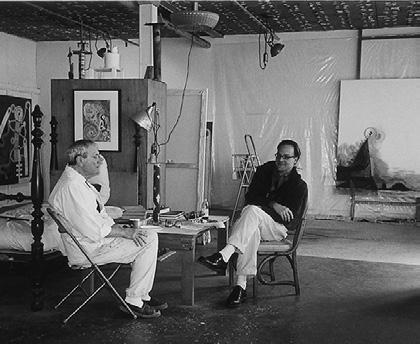

opposite and above

For Lobdell, the full eVect was not immediate, but certain ideas that he took from Still would have a lasting impact: indiVerence to decoration; immersion in the materiality of paint and the sheer physicality of the relationship between texture and form; a sense that the events on the painting continue beyond the edges of the canvas, which leads to a rejection of the frame as an arbiter of coherence and meaning; the ways in which large Welds deWne smaller ones, and vice versa, an active exchange that inXuences the spatial character of the overall image; and by extension, an understanding of the painting as a fundamentally spatial event. Lobdell never really accepted the idea, in circulation by the 1950s, that Still’s work was based in the Western and the romantic landscape traditions. For him, its primary subject was space, space built with a technique so coarse and aggressive that it bordered on violence. Picasso brought a barbarism of his own to the image, which was an aspect of his appeal for Lobdell, but Still shifted emphasis from depiction and narrative invention to the painting as an object unfettered by conventions of pictorial logic, an image excavated from its own materials.

Other contemporary painting was available to artists working in San Francisco at the time. The San Francisco Museum of Art owned Pollock’s Guardians of the Secret (1943), a painting whose inXuence can be detected in the work of a number of artists in the city, and also owned Rothko’s large surrealist canvas Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1944); museum annuals brought the work of Gottlieb, Baziotes, Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and other artists in New York. But distance—the condition of information often acquired at second hand—would prove to be an impediment to the local dispersion of European modernism. The Bay Area had no émigré artists to serve as role models, nor galleries in which to see their work; most of the art activity revolved around the schools. As a result, San Francisco never experienced a surrealist phase in quite the same way as New York, and indeed, some notable aspects of the surrealist program simply had no application there. But with the understanding that the self had priority in abstract painting, an idea of surrealist automatism did arrive more or less intact. As a result, San Francisco abstraction displayed a distinctive gestural tendency almost from the start, sometimes Xamboyantly so, in colors inXuenced by the variety of the landscape and the chiaroscuro of intense light and shadow.

While abstract painting in the Bay Area was greater than the sum of its inXuences, one can chart aYnities between Pollock’s surrealism and James Budd Dixon’s scabrous canvases; the compositional divisions and muted palette in Rothko and Edward Corbett or Edward Dugmore; the frisky, erotic line of Arshile Gorky and Baziotes as it popped from Hassel Smith’s twirling brush; or Pollock’s allover paint application, pushing hard against the borders of the canvas, in the work of Ernest Briggs. In the end, however, the evocation of the physical world, in all its immediacy, would be central to the character of San Francisco abstraction, together with the rather idealistic embrace of abstraction as a journey into selfhood, using automatism as the primary vehicle of access; or to put it another way, the subconscious and its negotiation of the environment around it, expressed in paint. In Lobdell, the debt to automatism is most evident in his drawing practice, an extensive, wide-ranging pursuit

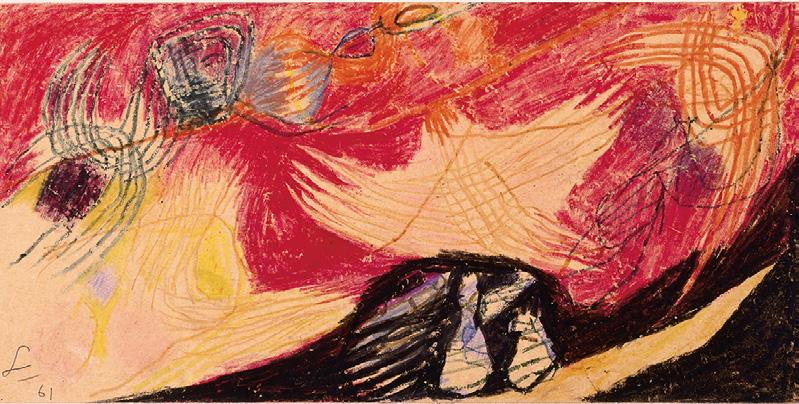

that exists in a kind of parallel to the paintings until the mid-1970s, when the drawings and paintings begin to move into close alignment. But with the San Francisco group as a backdrop to his activities during the 1940s, it is clear that he was already as interested in signage and space as he was in signature gesture.

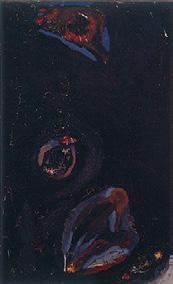

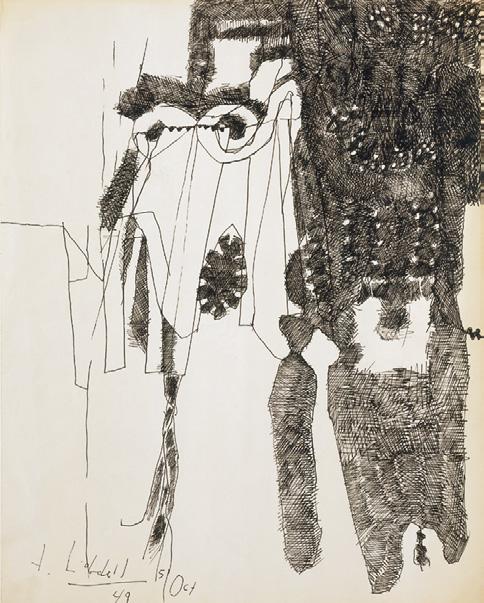

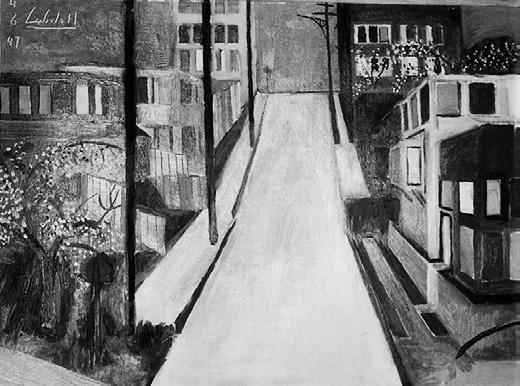

At times, Lobdell can be quite straightforward as he works from ideas that were circulating throughout the period. 10 October 1947 (Wg. 2), for instance, is assembled into a grid of squares and rectangles, each containing a discrete pictographic image; in November 1947 (Wg. 3), reddish rectangles are set down like bricks, creating an architectural form that resembles a niche, with a totem wedged into its dark space.

The format of 10 October 1947, derived from cubism, eliminates centralized or hierarchical perspective, as it does in Gottlieb’s similarly arranged images. The pictographs suggest no internalized thematic connections; the compositional structure keeps the eye moving from one box to the next in a quest for associative order, though it is granted little opportunity to alight on any one spot for very long. If this is a specimen drawer, its organizing principles are uncertain, and if it is a collection of “found” objects—found in the subconscious, that is—then the artist seems quite determined to prevent the conscious mind from reassembling it symbolically. If the verticality of the composition is meant to play upon the notion of the painting as a window, prospect is denied; it opens instead upon an apparently random sequence of diVerentiated views whose simultaneity cannot be absorbed in a glance. In this instance, painting is plurality rather than a purveyor of Wxed meaning. References to archetype, particularly in 10 October 1947, are suggestive at Wrst glance, but their obscurity eventually closes them oV. The images are not selected from some dictionary of symbols with the intention of constructing thematic relationships. Their objective is semblance rather than speciWcity. One is reminded of Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror (1932, Wg. 4), in which a grotesque, disjointed interior state is reXected back at the cubist Wgure before the mirror, as if identity—physical and psychological—can only be measured in terms of disruption or fragmentation. But Lobdell had recognized already that symbol, even archetypal symbol, is fundamentally illustrative, a clear code, while signage, with its resistance to the decoding process, leads the viewer

back to the function of the painting as a painting: a visual event that draws attention to the inherently abstract nature of the medium rather than a poetic cipher, ripe for interpretation.

Lobdell did make use of a more orthodox gesturalism, but given the historical circumstances, that would have been diYcult to avoid. A sturdy, exuberant brush is at work in the asymmetrical arrangements of color patches in, for example, May 1949 (Wg. 5). Just as frequently, however, Lobdell uses generous brushwork and thick color Welds to brush out, bury, eliminate, or disguise areas of prior painting activity, a tendency evident in 31 December 1948 (Wg. 6), 13 September 1949 (Wg. 7), 1 January 1949 (Wg. 8), and 30 April 1949 (Wg. 9) The strategy of removal also occurs frequently in his drawing practice during this period: a habit of packing his surfaces with an abundant spillage of imagery and then covering or partially withdrawing those that do not seem necessary to the resolution of the work—indeed, the technique continues to serve him even now. Nor was Lobdell the only artist in the Bay Area to employ it during those years. Well into the 1950s, many of Richard Diebenkorn’s abstract canvases pursue a similar method: the horizontal, earth-colored ridges and planes that suggest landscape often mask dense zones of paint activity. In Lobdell’s case, the images can be just as broadly evocative, but at the same time, their very generality follows from the artist’s desire to leave the familiar image world behind. In this sense, the dark formations in many of the paintings function much like the Xat, forbidding ink Welds in the drawings, lying across tangled bursts of linear activity. At the same time, they gaze toward the Wgural canvases of the mid-1950s, those tormented shapes developed from a severely limited palette and charged masses of brushstrokes.

But spatial relationships are a fundamental concern. The spread of dark color (in 31 December 1948 or 30 April 1949) has a striking visual eVect: the paint feels almost nondimensional, a rich-hued but unequivocal substance that lies directly upon the surface of the canvas, simultaneously deXecting and heightening our sense of the depth beneath it. It traverses a region between the representational and the nonobjective, image and pure paint, expression and a ruthless handling of materials. To some extent, these tendencies in the work may derive from Still, whose ragged compositions were intended to defeat the enclosure of the frame, which he regarded as an unwelcome tyrant: by doing away with conventional hierarchies of visual eVect, he hoped to undermine the traditional security of the rectangle, and by extension, the idea of the painting as a mode of embodied meaning. Still did not wish merely to replace order with disorder, a condition for which there could be no real justiWcation. But his paintings pose a crucial question: what, other than space, can the painting describe? For the moment, at least, this is crucial to Lobdell, though he also digresses from it to consider ideas that may have been drawn from Rothko or Corbett as he divides 27 January 1948 (Wg. 10) into elegant washes of cream, brown, and mossy green, once again with a screenlike Xatness that arrests our vision at the surface of the material. The edges along the bands of color are borders where the forms linger, or where they are trapped: the ovals with spiky teeth, like barred holes that almost (but not quite) permit a view beyond the surface of the painting. These

holes will continue to have considerable importance for Lobdell, and they reemerge later; yet even at this early stage, their intimation of other spaces behind the canvas is a signal that the broad, brushy paint Welds should not be regarded simply as “background.” The artist is attempting, rather, to Wnd a means of engaging a multiplicity of spatial Welds. In this instance, they beckon with the promise of a further view before bringing us to a halt with their fearsome denial of entry.

Lobdell was moving swiftly as he internalized a wide variety of the developments taking place elsewhere in progressive art. He never studied with Still, however. He had seen the work of students who bore Still’s inXuence in a direct way, and so, as an instinctive act of artistic self-protection, he decided to avoid the older artist’s classes. In any case, the golden years of the abstract expressionist experiment at CSFA were coming to a close by the decade’s end. Veterans attending the school on the G.I. Bill had exhausted their funding. Faced with a critical decline in enrollment, MacAgy, who had led the school through this exhilarating era, departed in mid-1950. Within months, Still was gone, too, having adjourned to New York.

That same year, Lobdell took what remained of his G.I. Bill money and sailed for Paris, where he enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, although he rarely attended classes. Neither did he seek out the recent developments in European art. He spent most of his time working in a cavernous studio at the Académie Colarossi, where, in the wintertime city, American

27 January 1948

expatriates and their families camped around a single immense stove. It was also a social place, with wailing infants and people coming and going all the time. In a photograph taken in the Colarossi studio, Lobdell stands among several large canvases. One in particular virtually mirrors the composition of November 1947, but in this instance, the forms are simpliWed Stillian Welds, with ribbonlike shapes dangling around the edges of the wide vertical planes; its organization into parallel panels echoes, too, the subdivisions characteristic of Picasso’s horizontal paintings during the 1930s and early 1940s, including Guernica. Although the work in the photograph is intriguing, it speaks most clearly, perhaps, of the thoroughness with which Lobdell was working his way through ideas regarding abstract painting as he patiently pursued his quest for an authentic personal style.

“I never really emulated Still’s space,” Lobdell said, “but I think that I understood the principle behind it pretty well. It was an environment rather than a deWned space. I can remember a few paintings in that exhibition in 1947 that were just great. Very moving paintings. There was a spatial ambiguity that I saw there, which is in Rothko’s work in a diVerent way, and in Pollock’s in yet a diVerent way. There was the matter of the spatial environment that all the work shared, and which I came to see as signiWcant.”

In the end, San Francisco would be the only city other than New York to produce a signiWcant abstract expressionist group, though relatively few artists there sustained or further developed the form to the extent that artists did in New York. Yet the failure to extend the style locally may have been no more than a matter of circumstance. The region lacked a substantial continuous art tradition of its own, and the commercial opportunities available in New York even by the early 1950s did not appear in the Bay Area until the end of that decade. Since so many painters went there primarily to study, they had no deep loyalty to the city itself, and so an inevitable dispersion began in the early 1950s, creating a vacuum that was Wlled by the artists now associated with the Beat era.

At the same time, the lack of a strong regional art tradition provoked anxiety in some of the artists who did remain, which found expression in their eVorts to establish traditions of their own. This provides an explanation for the appearance of an identiWably local Wgurative painting style in the Bay Area during the 1950s, although the Wgurative movement was also a product of more encompassing conditions already in place in the region. From the beginning of the modern era, progressive developments in art were rarely embraced without question as they made their way to the West Coast. More often, they aroused a native mistrust of both European and East Coast models, and as a result, discourse among artists surrounding the “new” tended to focus on the appropriateness of assimilation, or how the “new” would, or should, become the “local.” Separatism, whether it operated as a geographical fact, a regional mythology, or simply a component of regional identity, became the platform upon which local artists interrogated the American acceptance of foreign models. For this reason, a durable regional enthusiasm for the California Style watercolorists, or for the vivid, painterly scenes associated with the Monterey and Carmel art colonies, comes as no surprise, nor can it be dismissed simply as willful provincialism.

The situation was informed, of course, by skepticism regarding the very notion of a centralized American culture. The new was often required to justify its claims upon the regional artist, and so the local embrace of abstract art during the postwar decade aYrms the extraordinary promise it held for artists at that historical moment. If an enthusiasm for abstraction did, in fact, arrive from outside the region, it was immediately contagious. A conception of the painting process as a quest for authentic individual voice held a natural appeal for artists who were not only fresh from the experience of war but who discovered that the insights of their experience opposed the mainstream values of a nation emerging as a conWdent, aZuent superpower. In this context, San Francisco never really required a distinctly surrealist period, nor did artists there feel a need to turn to archetypal or tribal imagery in order to evoke a “collective” or “essentialized” culture. That work had already been done elsewhere, by others. If the quest for a “primal” self was an ambition, that self operated in a contemporary, postwar world and needed to be addressed in a contemporary setting.

As an artist, Lobdell at the turn of the decade is inseparable from these conditions. In the same way that he intuitively avoided close study with Still, he was now drawn to the isolation and relatively placid pace of the Bay Area as a setting in which to continue his work. Another year had passed, and his stay in Paris came to a close. He returned to San Francisco in 1951, supporting himself with various part-time jobs. His Wrst studio was at 645 Chestnut Street; he next set up a studio in the AudiVred Building, a handsome nineteenth-century structure along the Embarcadero. Ernest Briggs and Jack JeVerson, with whom Lobdell would enjoy close collegial relationships, were two other artists in the building, but much of the old crowd was gone. They were on their own.

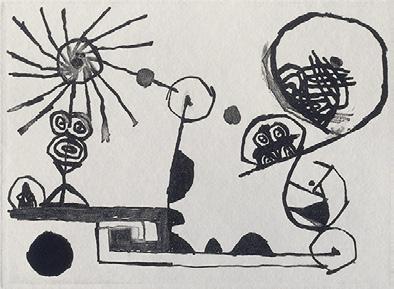

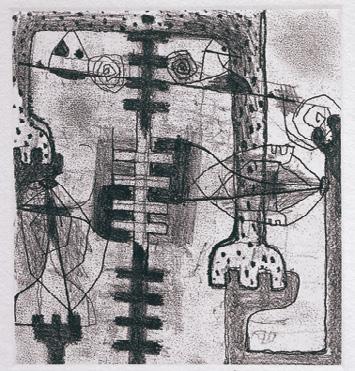

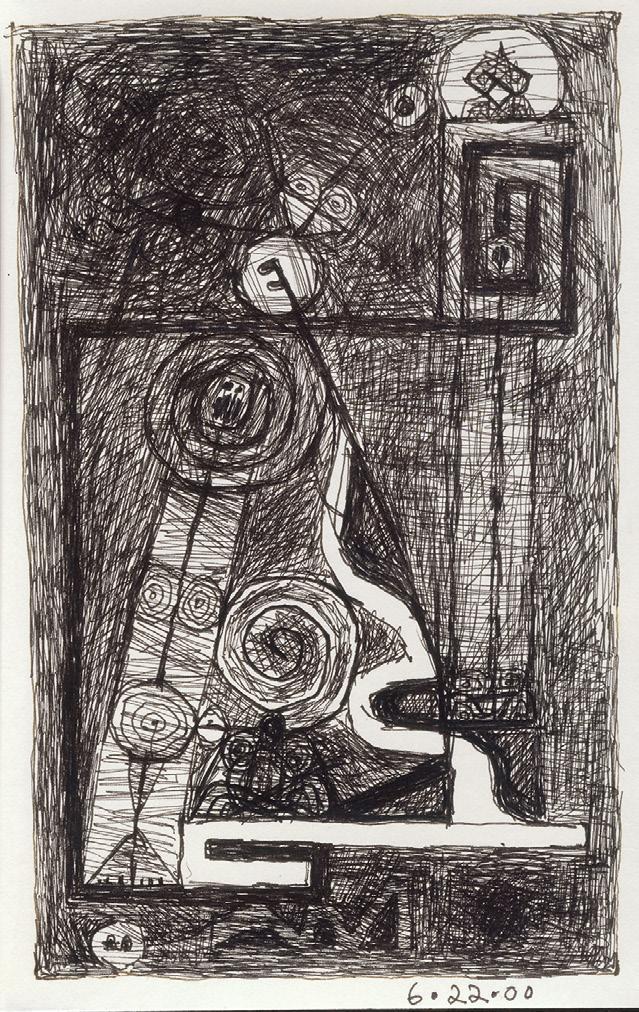

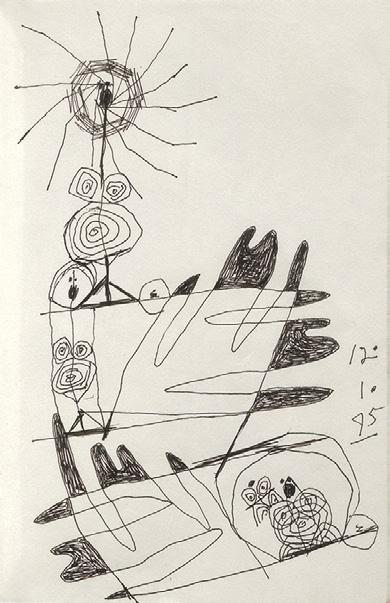

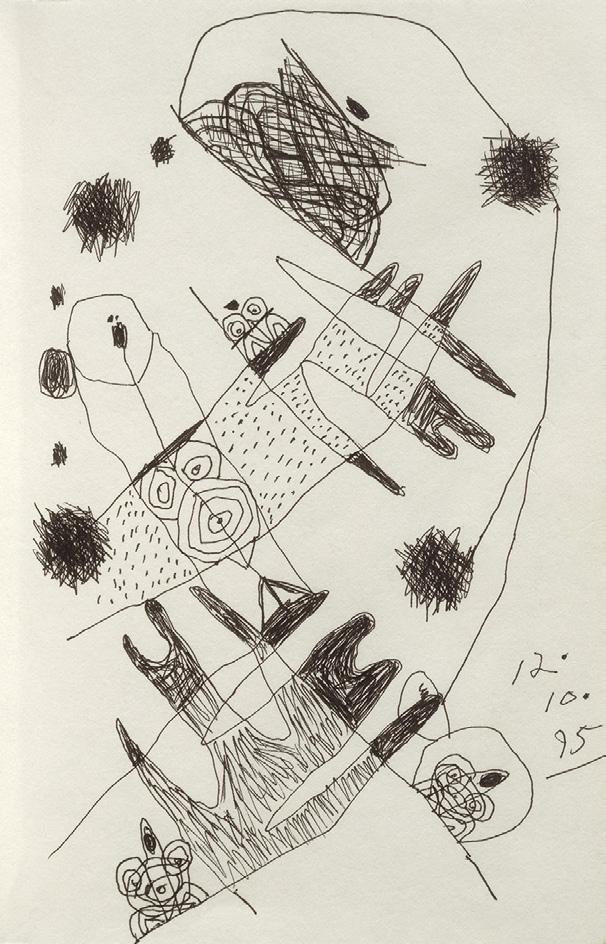

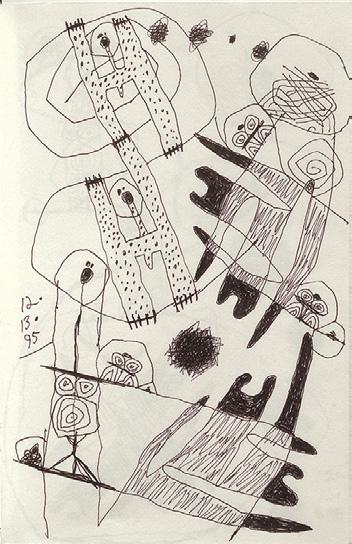

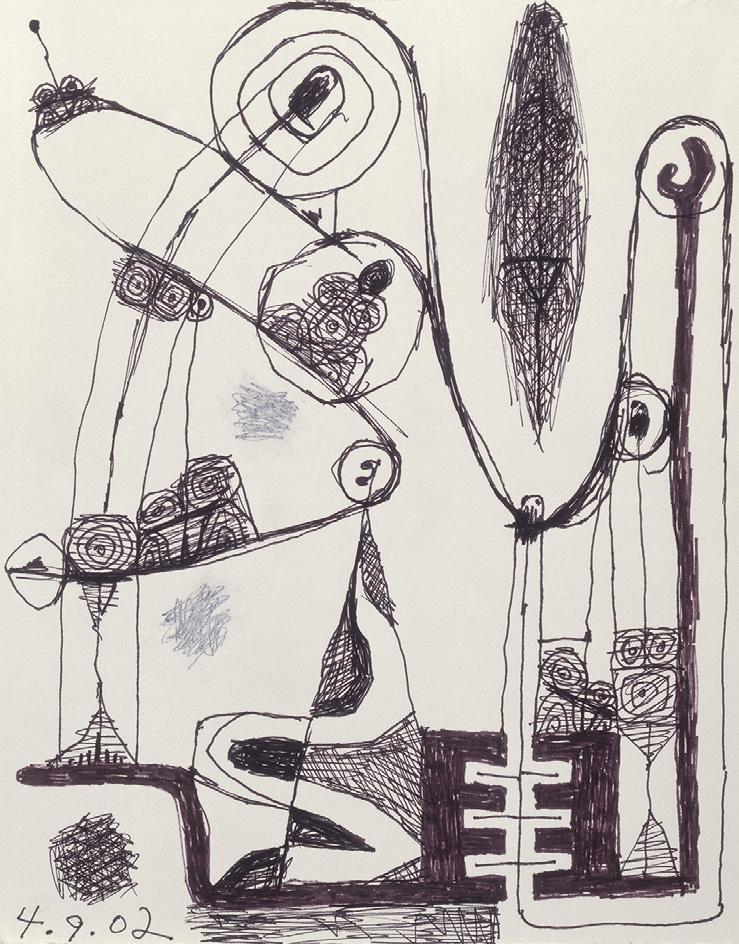

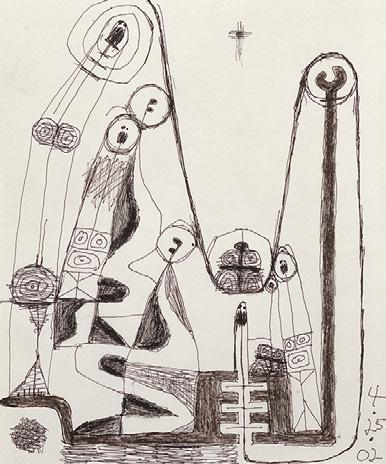

The thousands of drawings that Lobdell has produced during his career are essential to an understanding of his work, but in these Wrst decades, they rarely follow an obvious course, or an easy one. Unlike the drawings after the late 1970s, which are largely committed to speciWc paintings, images, and compositional ideas, the early drawings take on a quality of sprawl as they sift through swarms of ideas, and yet they will almost always suggest the presence of an underlying discipline or concentration, as if any image, however far-ranging, is still tethered to a central purpose. They map a terrain, though not necessarily a clear path through it. Formal overlaps exist among the early paintings and drawings, certainly—the surging masses, the solitary and sometimes fragmented Wgures, the melancholy, faintly gothic romanticism—but a clear sense of correspondence is absent, at least until the early 1960s. The numerous digressions and anomalies—the quirky Wgures, the oblique references to mythology, the visual ideas that recollect a distinctly European surrealism—would appear to have only slight bearing on Lobdell’s primary imagery, but regardless of their speciWc associations for the artist, they can be seen as the declaration of his desire for the freedom to pursue his own needs and interests, one from which he could not turn, and one that would liberate him from the dogmas of representation and abstraction still in force in the Bay Area at that time. If the paintings, especially after the early 1950s, adhere to a Wgural expressionism that developed from Lobdell’s experiences

among the San Francisco abstract expressionist group, his drawings, which he had already come to regard as a tool of research and self-investigation, demonstrate a much wider range of interests, and they reveal the care and patience with which he pursued them.

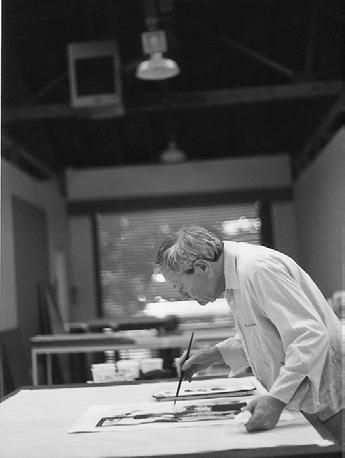

The crucial element in the drawing practice, which soon spilled into the paintings, is a quality that Lobdell simply calls the hand. Almost everything he has done in his art, it seems, is related to the hand’s development and maintenance. The inferences embodied in the term are obvious, and yet the idea of ‘hand’ quickly spreads to an array of references and meanings, all of which are integrated into the practice itself. In the most straightforward sense, the hand holds the mark-making tool and commits the marks: it represents the literal, physical component of drawing, the actual movement of the pen or pencil across the surface of the paper. An individuality of gesture is intrinsic, of course, and so the drawings, well into the 1950s, may be seen as a quest for an idiosyncratic mark—that is, the gradual distillation of what is wholly the artist’s own from amid the array of marks and gestures he is capable of making but which arrived from sources or inXuences that seem to him inessential, extraneous, or imposed. The matter of inXuence is tricky, as Lobdell recognized early on, and at some point, distinctions can become very Wne. But abstract expressionism, as he encountered it after the war, oVered a solution.