Jim Lorimer A memoir

Copyright © 2022 by James J. Lorimer

All rights reserved

ISBN pending

Had the story been told there is none I would value more highly than what the life of James Lorimer was like. That is, the James Lorimer who was born in Kilmarnock, Scotland in 1836, nine decades before me who had the courage at age 19 to move to a new world. Why did he do that? What did he know about the world and times in which he lived and what were his life experiences in that world? His story made all the difference for my life and yet it is unknown.

It is also fascinating and true that the last three quarters of the 20th Century through which I lived were the most life changing in all of human history. Prior to that time people had lived very much the same for more than a millennium. The industrial and technological revolutions, nations moving by stages from agrarian to manufacturing to service focused societies, the doubling of human life spans –all are fantastic stories that the first James Lorimer could not have imagined.

This recounting of a life lived through a period of such unprecedented change could be told by many of much greater accomplishment. My tale is aimed at contemporary friends and heirs of mine who may wish to recall and hopefully will later be interested to learn how lives were lived through this fantastic time. With technology building geometrically on technology this story will likely seem quaint to the future reader, but we surely did see a lot. Most important, the love of my life wanted the story told.

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times …

The name Lorimer is a common surname in Scotland. It derived from the French word “lormier,” meaning the maker of the metal parts for bridles, spurs and bits. Before the year 1000 A.D., populations were so sparse that few people carrier surnames. Multiple names were reserved for royalty.

A person would be known as James the lormier, James the smith, or James of Nottingham. Personal identification was the individual’s given name with the added reference to their occupation or place of origin to further distinguish them.

The name Lorimer is believed to have reached England and Scotland as the Norman (i.e. French) invasion and occupation occurred in 1066 A.D. William the Conqueror led that invasion and for the next 300 years the French language and culture were enforced upon England. While the native emerging English language finally prevailed, it was heavily influenced by this three century French incursion.

Some centuries later a number of James Lorimers appeared in a direct line in southern Scotland near the small town of Kilmarnock. The first of our lineage we have been able to correctly identify is the James Lorimer born on June 10, 1793 in Kilmarnock. He was a farmer who lived his life in that Scottish community. He did not marry until the age of 38 when on December 30, 1831, he married Mary Russell, age 19. Mary was the daughter of Thomas Russell and Janet Beveridge. No certain record of James Lorimer’s parentage has been found. James and Mary had a son, also named James, who was born in Kilmarnock on May 15, 1836.

This second James Lorimer lived his early years on Douglas Street in Kilmarnock, at an address that no longer exists as we found upon a visit to our ancestral town. The occupation of this James Lorimer was listed as carpenter when he first traveled to the United States in 1855 at age 19.

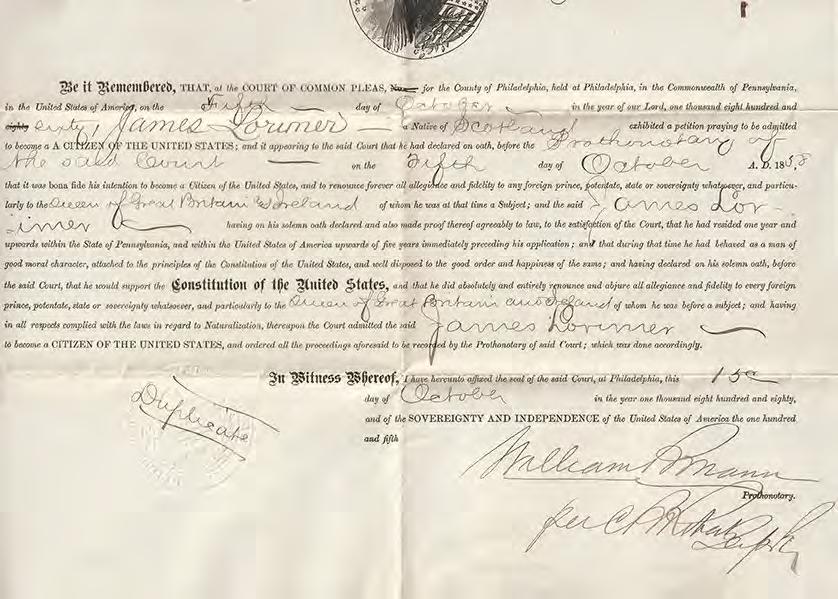

The first James Lorimer in the United States emigrated to Bristol, Pennsylvania, from Kilmarnock, Scotland, in 1858, and was granted U.S. Citizenship by this document in 1858.

It is known that his father died that year, but it is not known whether that event or the harsh economic conditions then existing in Scotland (i.e. famine in both Ireland and Scotland connected with the loss of the basic staple, the potato crop) caused James to venture to this new world. We can be sure the decision was not easy for one whose family had lived in the same small Scottish community for generations. Still, there have been several generations of Lorimers since then who are most grateful that James had the courage to seek a new life and the greater opportunity that seemed possible in the United States. He was not alone. There was a large emigration from England, Scotland and Ireland to the United States during this period.

James Lorimer traveled by ship from Glasgow to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It

would have been a multi-week crossing of the Atlantic under cramped and harsh conditions. His papers indicated he was an apprentice carpenter and he found work in the Philadelphia area.

In early 1956 he returned to Kilmarnock to ask his childhood sweetheart, Elizabeth Campbell, to marry him and come with him to the United States. They were married in the Parish Church of Kilmarnock on March 2, 1856. Their marriage license reflected the occupation of carpenter for the 19 year old James Lorimer, and spinster for the 23 year old Elizabeth Campbell. She was 4 years older than James and signed the church register with her ”mark.” James signed his name in full.

James and Elizabeth traveled to Philadelphia where they settled in a home on Mt. Pleasant Avenue. They lived in this area for the next 20 years and he moved through several occupations. He was a carpenter, a nursery man, and later a policeman in Germantown. They were Scotch Presbyterians. James was later described by his son, Jasper, as having been an avid reader, an immaculate dresser, and a rather stern looking 5 foot 8 pipe smoker.

Beginning in 1859, James and Elizabeth had eight children, William, Mary, Lizzie, Jasper Howatt (our sire), Agnes, Robert, Jennie and Jean. Agnes, Jennie and Jean died in childhood.

The widow of the first James Lorimer of whom we have record remarried a man named Jasper Howatt, and then also emigrated to the Philadelphia area. Jasper Howatt was reasonably well to do and he became owner of a farm in Croydon, Pennsylvania, northeast of Philadelphia along the Delaware River. Mary Russell Lorimer Howatt later bequeathed this farm property jointly to her son by the second marriage and to James Lorimer

In the early 1880s, James Lorimer moved to the Croydon farm to share in caring for the green houses that had been willed to him and his step brother. His oldest son, William, joined his father on the farm which produced their food and also a reasonably good living from the several greenhouses that supplied flowers they marketed in nearby Philadelphia markets. William Lorimer married Margaret Carr Jones in Croydon and they had two children, Elizabeth and Charles.

William died on July 28, 1887 at the age of 29, leaving his wife and two young children on the Croydon farm. The cause of his death is not known.

James Lorimer continued as head of the household in Croydon, operating the farm and greenhouses. The farm contained a large barn and livestock including horses, cows and poultry. Their primary food crops were corn and wheat, which were planted about 100 yards in front of the farmhouse and between the house and the Delaware River, within view about a half mile east. The primary and strong source of income stemmed from the green houses. Farm life was difficult but comfortable for the times. The farm never had indoor plumbing. All transportation was by horse and carriage. A train station in Croydon permitted direct access to Philadelphia, but most delivery of flowers was accomplished through horse and wagon handling.

My grandfather, Jasper Howatt Lorimer, was born in Mount Airy, Pennsylavania on October 25, 1863. He attended Grammar School in Mount Airy from age 6 to 11. He would deliver morning papers before school, meeting a 6:30 a.m. train from Philadelphia. Several papers were handled: The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Times, German Democrat, and the Philadelphia Record. Only the first of these papers has survived through time. Sorting these deliveries for subscribers in the Mount Airy area must have involved some challenge for young Jasper Lorimer.

At age 11, Jasper quit school when his father gave him the option of attending school or going to work. He applied for work at a carpet factory at that young age and was hired as a piecer on a spinning machine. He worked six days a week from 6:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., with one hour for lunch, and was paid $2.50 per week. On the first of every month, he was paid $10, and his sister, Lizzie, would accompany him to collect the money and turn it over to his mother for household needs. At the time, Jasper’s father (James) was making $65 per month as a policeman in Germantown. Jasper expressed doubt that much of the money he earned was actually used for “household needs.”

Jasper quit working at the carpet mill at age 16, having worked there for five

years. His work day had been increased to nearly 18 hours for almost a year, and he was beginning to grow very thin He had lost his appetite and was living primarily on a supper consisting of the drink “half and half”, that was half ale and half port. This he would drink each evening before going to bed around 10 p.m. Feeling the need to work, he took a new job at a green house owned by John Burton. This paid $4.50 a week and he continued working there for the next five years.

He left Burton at age 21 in 1884 and was making $15 per week, which he reports was considered “big money” at the time. The problem had become the relocation of the Burton greenhouses to Springfield in Montgomery County, which was too far from Jasper’s home in Mt. Airy. He immediately found work in Mt. Airy managing eight greenhouses for a man named Bilder, receiving the same $15 per week salary. Jasper worked for Bilder for the next three years.

In June 1887, at the age of 24, Jasper moved to the Croydon farm at the request of his father and uncle, Robert Howatt. The next month Jasper’s brother William died. It is unclear whether Jasper was asked to come to the farm because of his older brother’s final illness. The tragic fact was Margaret Lorimer was left a widow with two young children.

Jasper worked hard on the farm. His extensive greenhouse experience was badly needed, and his brother Bob, and sisters Lizzie and Mary also assisted in maintaining the farm crops and the greenhouses. The harshness of the work again caused him to lose considerable bodyweight, going from 160 down to 130 pounds.

William Lorimer’s widow, Margaret, continued to live on the farm with her two children, Elizabeth born in July 1981, and Charles born in December 1983. On July 29, 1889, two years after Jasper came to live and work on the farm, Jasper and Margaret were married. Jasper was 25 and Margaret 26. Jasper thus assumed responsibility for his brother’s widow and her children.

On June 30, 1890 the first son of Jasper and Margaret, Jasper Howatt Lorimer, Jr. was born on the farm. The following October 21, 1991 a daughter, Margaret, was

born. And on Christmas Day 1892, my father Frank Duffield Lorimer was born. The middle name was taken from a nearby neighbor family name.

During all of the 1880s, 90s, and the first decade of the 20th century, the Lorimer family was headed by James Lorimer. In early February 1912, a horse named “Dolly” kicked to the rear and struck James Lorimer in the chest, breaking several ribs. James died a few weeks later of “pulmonitus.”

At age 75, his last words were, “Don’t blame Dolly.” The family patriarch who had led the Lorimer family to a new world and life had passed away.

Frank Lorimer was the youngest of 5 children. He grew up on the family farm in Croydon, and attended school through the 8th grade at the Badger School in Croydon. He was discouraged from continuing in school, and lived briefly with his older sister, Elizabeth, in Bristol. He soon returned to the family farm and was focused, like his father, primarily on maintaining the 5 greenhouses that had become the family’s main source of income.

He lived on the farm and worked the greenhouses from age 14 until age 23. The year was then 1917 and World War I was underway. A military draft had been instituted and Frank, a single young man, was classified as 1 A, which made him subject to early conscription. He was encouraged to obtain employment in essential war related work that would make deferment possible, and he obtained employment at Traylor’s Shipyard in nearby Cornwells, Pennsylvania. There he helped build wooden freighters by cutting ribs for the ship’s hull with a power saw.

Upon the signing of the World War I armistice in November 1918, the shipbuilding at Traylors and other war related production ceased. Rather than return to the Croydon farm, Frank moved to the Harriman Ship Yards (later Fleetwings) in Bristol where he was employed as a lay up man. This work involved putting side plates on metal ships. He worked at this job throughout 1919 when a strike of scaffold builders resulted in a large scale layoff of workers. He then began driving an oil truck for Atlantic Refining company while continuing to live on the family

farm in Croydon.

In the early 1920s. Frank Lorimer, his sister Margaret, and their parents were the only people still living on the family farm. His older brother Jasper, and his half brother and sister, Charles and Elizabeth, had all left the farm to become married. The greenhouses had all been destroyed by windstorms.

His father, Jasper, worked as a highway construction supervisor and Justice of the Peace. Jasper and Frank also tended to the spring planting and care of the farm livestock. Space was available and it become necessary to accommodate boarders and lodgers on the farm. My grandmother and Aunt Mar would cook for everyone.

Frank’s work with Atlantic Refining involved delivery of oil to homes and stores using oil in the Bristol, Langhorne, and Morrisville areas. He was paid $35 per week for working 10 hours a day for 6 days. Sundays were the day off for most people at that time.

In the Spring of 1921, Frank Lorimer and Mildred Harbison were walking along the bank of the Delaware River near the Lorimer farm. Mildred was with a girlfriend, and Frank was by himself. Mildred was just 17 and Frank was 28. Neither had ever had a date with anyone else. Mildred’s friend left them alone, and Frank took Mildred for a canoe ride on the Delaware. Thus began a very long and wonderful relationship, that made some difference for me.

From talking with my mother and father, separately, about their first meeting it is clear they were both very bashful. My mother because of her youth and lack of dating experience, and my father because as he told me, “I had been afraid of girls.” So, it was the meeting of two lonely people, each in search of someone to love and care for. The young girl working as a telephone operator to help support her widowed mother living in dire poverty, and a young man reared on the farm, always committed to long hours of work, and with little exposure to social settings. The time and circumstances were right for them.

Mildred Harbison was born on March 22, 1904, in Bristol, Pennsylvania.

She was the first child of John Harbison and Margaret Marshall. John worked in the Bristol Carpet Mill, and he was killed in 1904 as he was taking a short cut across a railroad track on his way home from work.

His widowed wife had just delivered their second child, a son Roy. At the time of her father’s death, the family was living in Tullytown and Mildred was 4 years old. She had no recollection of her father.

The family later moved to Pond Street in Bristol when Margaret Harbison married Elmer Shire in 1911. Three Shire children were born: Renee in 1912, William in 1913, and Leland in 1914. Elmer Shire died in 1918, this time leaving Margaret as a 31-year-old widow with five children. The oldest of the children, Mildred, was in 8th grade. She managed to continue in school at Bristol through grade 10, and then with the brief support of her grandfather, James Marshall, took one year of secretarial training at Rider College in Trenton, New Jersey. Mildred then began working full time at age 15 as a Bell Telephone operator in Bristol. She had previously worked in the summers at age 13 and 14 at the Leedom’s carpet mill in Bristol.

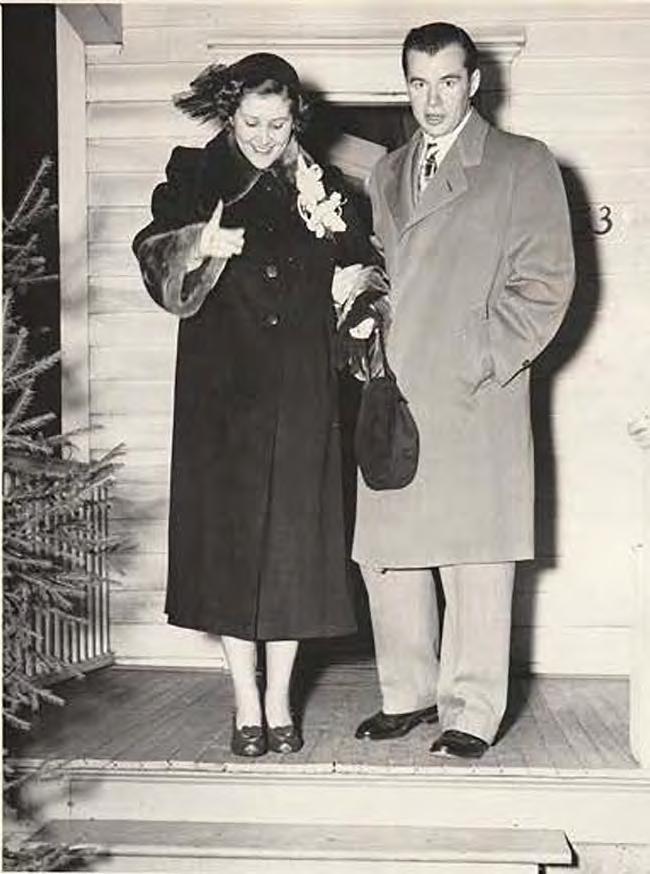

At age 17, Mildred was promoted to Chief Operator at Eddington, Pennsylvania, just south of Bristol. To save travel expense and time she moved to White Hall in College Park in Croydon. It was there she met Frank Lorimer and in a little more than 6 months after their first meeting on the banks of the Delaware River they were married – on January 21, 1922.

Their courtship had been steady and intense. My father had been earning for some years. He was single and well employed, paid no board at home, and owned a car (an Overland) and a motorcycle (Harley Davidson). He would court my mother on the Harley and on boat rides on the river. He began visiting her each evening as she handled her nightly phone operating duties, and he would then drive her home from work. He had paid $300 for the Overland car, and had to drain and store the car during the winter because anti freeze protection was not then available.

Mildred’s employment and support of her mother had enabled her family to

move to a better home in Bristol on Pine Street. Mildred’s mother voiced strong concern regarding Mildred’s interest in a man 12 years her senior. Her mother strenuously warned her not to marry an older man. “You will end up taking care of him”, she said. The opposite proved to be true, and my mother commented on that fact to me just before her death 54 years later.

The only girlfriend Frank Lorimer ever had was Mildred Harbison. By his own account he never dated another woman, and they had no sexual relations before they were married. He said, “I wanted to, but she would not.” But neither the lack of experience, the 12 year age difference, nor Frank’s natural reticence toward women – prevented the relationship and a loving courtship from developing into marriage.

On Saturday, January 21, 1922, in his usual taciturn manner, Frank surprised his mother and sister (both named Margaret) by announcing as he left the farmhouse kitchen that morning that he “was going out to get married.” Neither mother or sister said anything as Frank walked directly out the door.

Frank and Mildred had obtained a marriage license in Philadelphia the day before that Saturday. They traveled by train from Bristol to Elkton, Maryland. That community was well and long known for providing quick wedding ceremonies. Their ceremony, based on a Philadelphia license, was conducted by an Elkton Baptist Minister, named Reverend Moon.

The newly married couple proceeded directly to the Adelphia Hotel on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, returning there by train. They took the precaution of borrowing a suitcase from friends and filling it with newspapers so it would have weight. This was intended to prevent questions by the hotel clerk regarding the legitimacy of their visit.

The couple returned to the Croydon farm the next day, where they were to begin their marriage living in a third floor bedroom of the farmhouse. Frank’s mother and sister were very much concerned and surprised that Mildred arrived at the farm with only the clothes on her back. She appeared to have no

personal possessions, and brought none with her. The Margarets immediately moved to help provide a nightgown, personal items, and some clothes they had available. Frank’s young bride was most appreciative.

Mildred Harbison Lorimer reportedly viewed the Lorimer household as well to do. She shared with my Aunt Mar that as a child at Christmas she was happy to receive half an orange as her present. During her later life, Mildred never referred to the hardships of her childhood. The economic hardship she had experienced was never known to us. I feel it was because she did not want us to know about this deprivation, and it also helps explains her strong determination that her children have a protected and greater life opportunity.

Mildred continued working as a telephone operator for the remainder of 1922. She then began assisting fulltime helping with the boarders and lodgers that the farm continued to accommodate. The farm was comfortable and the lodging rates were reasonable, even though there was no running water or indoor plumbing. At the time those conveniences were not seen as necessary, and the farm never obtained indoor plumbing. Frank and Mildred lived on the Croydon farm for the first four years of their marriage.

In March 1922, two months after their marriage, for the first and only time in his life my father was fired from his job. It was demanded that he drive the oil truck through a blinding now blizzard and he declined to do so. He returned to work with the Traylor company that had begun manufacturing trucks and farm tractors. His job involved demonstrating tractors at county fairs, and he sometimes took Mildred on those demonstration tours. Working in the rain in this tractor demonstrating work resulted in Frank contracting a serious case of pneumonia in October 1922. The pneumonia problem would trouble him again much later in his career.

Just before Christmas 1922, Frank’s older brother Charley asked him to help as an apprentice electrician in Kensington, a Philadelphia suburb. Frank commuted daily by train for the next two years. That experience began his life career as an electrician. Following a slowdown in electric work in Kensington, Frank obtained

work in the maintenance department of the Burlington, New Jersey, Island Park. There he maintained the electrical wiring for the Park rides, and had to ferry across the river daily to work.

In the Fall of 1924, he began traveling to Trenton, New Jersey on the weekends to find work in that larger city as an electrician. Union membership was required for most jobs at that time, and he inquired whether anyone was hiring non union electricians. He found that a man named Kelly, owner of Kelly Electric, was hiring both union and non union workers. Frank was hired by Kelly in October 1924 and worked for Kelly for $1 per hour from 1924 throughout the Depression years until 1939.

He recalled for me that during the week in July 1933 when my brother was born, be earned and was paid just $6 for the hours he was able to work.

During the first months of his new Kelly employment in Trenton, Mildred would drive Frank, in their Overland car, to the Bristol train station each morning. She would pick him up on his return late in the evening. Desiring to move closer to his place of employment and also wishing to move away from the Croydon farm, Frank and Mildred found a small apartment at 215 Highland Street in Trenton and moved there in March 1926.

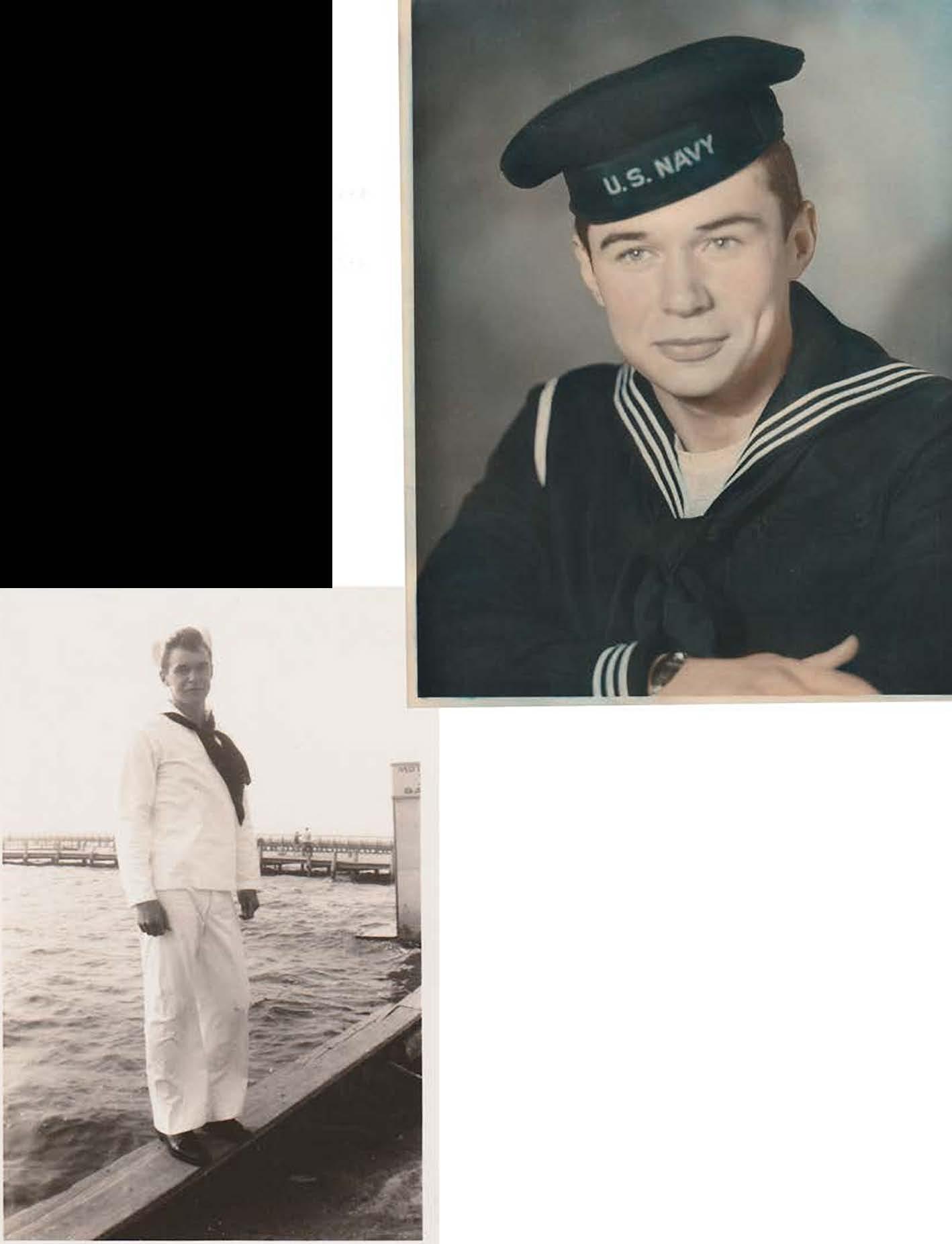

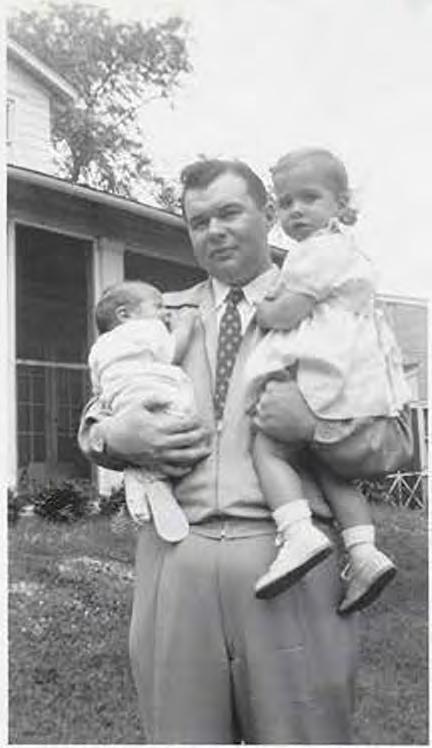

A son was conceived at about that time, in Croydon or Trenton, and that first son, James Jasper Lorimer, was born on October 7, 1926. The delivery was in the Bristol hospital where Mildred Harbison had been born. She returned to have her own baby there. She recalled that the delivery had been difficult, and the forceps used produced a young boy who came out looking somewhat the worse for wear. Fortunately, most of that harsh James Jasper Lorimer, born Oct. 7, 1926

initial treatment did not remain to be seen. James Jasper Lorimer was named for his grandfather and great grandfather.

In July 1927, the family moved from Trenton to a home at 90 West Maple Avenue in Morrisville, Pennsylvania, a small community directly across the Delaware River from the New Jersey capitol city of Trenton.

Frank and Mildred Lorimer would live at this address for the rest of their married life. Mildred died in this home on January 4, 1976, after 54 years of happily married life.

Frank continued his employment with Kelly throughout the 1930s. As World War II began he moved to the Fleetwing Aircraft facility in Bristol, where he served as an electrician throughout the War years.

In 1947, at age 55, he moved to the maintenance department of Warner Sand and

Gravel in Morrisville where he worked until retiring in 1961 at age 69. Even though he worked at Warner’s for 15 years, he was denied retirement benefits because that short a period did not qualify for such benefits.

Frank and Mildred Lorimer began their marriage in The Roaring Twenties, which has been described as one of the most colorful decades in American history. An industrial boom was underway in the auto industry, along with increased demand for all types of consumer goods. It was an era of pleasure and economic prosperity.

Radio was the medium of the masses. Movies were increasingly popular though silent throughout the decade. There was widespread violation of Prohibition, rise of speakeasies, increased popularity of Jazz music, and enthusiasm for dancing the Charleston. Along with women gaining the right to vote, the “Flapper” was a new breed of young women who flaunted their greater freedom and variety of life. The country was filled with energy and optimism.

Those of us born in 1926 arrived at the height of this thriving period. That year the Ford Motor Company established a 40 hour work week and pay of $6 a day.

One in six persons owned a car and 78 percent of the world’s automobiles (24 million) were in the U.S. NBC became the first national radio network, and a female evangelist described social dancing as “the first easiest step towards hell.”

Herbert Hoover was elected President in 1928, succeeding two previous Republicans, Warren Harding in 1920 and Calvin Coolidge in 1924. Hoover’s campaign promise was a quaint, “Chicken in every pot!”. In the view of some economists, the economy was becoming overheated, governmental controls were inadequate, and the stock market was increasingly speculative. All of these concerns proved justified.

Thus, while the Roaring ’20s were a heady time, the decade ended in strong decline. The precipitous event, but by no means the sole cause, was the Wall Street Stock Market crash on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. A selling panic on

that day began the loss of millions for individual and institutional investors. People ceased investing, curtailed purchasing, and lost confidence in banks. Manufacturing slowed and people lost jobs. The downward cycle of economic depression had begun, and its effects were worldwide. A decade filled with hope and success ended badly.

Uncle Bill was Henry E. Billington. He and my Aunt Mar lived in Chicago. Aunt Margaret Lorimer was my father’s sister. She was five feet tall, and uncle Bill stood an imposing 6’2”. He was distinguished looking and highly successful as a businessman. He was my rich uncle, and I still wear his diamond ring which Aunt Mar gave me after his death.

In the summers of 1933 and 1939 I visited with Aunt Mar and Uncle Bill in Chicago. They liked me and I liked them. These vacations were most interesting and enjoyable memories. During my first Chicago visit I was accompanied by my grandfather, Jasper Lorimer. We traveled overnight by train from Philadelphia. We were to spend a week with the Billingtons, and also visit the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair which was celebrating “A Century of Progress”.

At that time, Aunt Mar and Uncle Bill lived on the famous Gold Coast of Chicago, which was an expensive high rise area overlooking Lake Michigan on the north side of the city. Their apartment was on one of the top floors, and the building had a doorman. It was luxurious.

While Uncle Bill went to the office each day, Aunt Mar took us to the World’s Fair and to the Chicago Zoo. The Fair was situated on the shore of Lake Michigan just east of Soldier’s Field, and it was huge. Even though the Depression was well underway, some 47 million visitors attended in 1933 and 1934 – paying the admission price of 50 cents.

The theme of the Fair was “A Century of Progress”, and the large exhibit areas

told the story of the great industrial and technological progress that had been made in the previous century. Several large corporations, General Motors, Ford, General Electric, Westinghouse had huge buildings displaying their latest and future products. Entire assembly lines were set up in the GM and Ford buildings, and we could see a car being made. There were large exhibit buildings devoted to developments in communication and agriculture. More than a dozen nations had pavilions which were set up as miniature villages reflecting the culture of Italy, Ireland, Spain, Egypt, etc.

There was also an exciting Midway that included a wide variety of entertainment. Carnival acts, Frank Buck’s Jungle camp, midget shows, Sally Rand’s famous fan dance (which I was hurried by), Ripley’s “ Believe It or Not”, people diving into tanks, Siamese Twins, and a Sky Ride that took you high above and across the entire Fair area. We attended the Fair on more than one day, and I remember these many wonders and the fun for a six year old.

One afternoon Uncle Bill took me to the Chicago Stock Yards. This facility made Chicago the center of the American meat packing industry for more than 100 years.

While this was a huge and important industry in Chicago, which Uncle Bill wanted me to see, the visit was not an especially good memory. Hundreds of cows were herded through narrow wooden chutes. As they reached the end of the chute, two men stood above them with sledge hammers and endeavored to bash their heads in. This was not a pleasant sight and the sledge hammer aim was not always successful. But it was the harsh reality of stock yard operations which continued for decades. The writer, Upton Sinclair, published an expose of stock yard conditions entitled, “The Jungle” in 1906, but still in 1933 the cruelty continued.

A much more pleasant memory was experienced at the Chicago Zoo. The Zoo was one of the best in the Nation, and it was the first I had visited. They had animals I had never even heard of, and many of them were placed just

across a small moat from the visiting public. I remember thinking that if one of those tigers got a good running start, it could be over here with us. But no one else seemed concerned, so I didn’t mention this potential.

After our visit my grandfather and I returned by train to Philadelphia, where my parents met us by car. It had been my first big adventure, and six years later I was to visit Chicago and the Billingtons again.

The 1939 summer vacation in Chicago was a real learning experience. At twelve years of age, Aunt Mar and Uncle Bill were welcoming me for what they intended to be a civilization process for their young and favored nephew. During my two-week visit I was to be guided in proper deportment, table etiquette., and inter personal greeting skills.

On this visit my parents put me on a train in Philadelphia, and I traveled overnight by myself to Chicago. The Billingtons met me at the train station and we drove in their Packard touring car to their large suburban home. They had advised me prior to the visit that they were going to give me training that would enable me to be comfortable in social settings at any level.

True to their promise, for the next two weeks focus was on manners. I respected what Uncle Bill and Aunt Mar had achieved and I welcomed their guidance. Evening meals were formal affairs with complete place settings. Sitting upright, never placing hands or arms on the table, shifting knives and forks between hands to cut meat, placing the fore fingers pointed downward on each utensil as you cut just one piece of meat at a time, breaking bread in quarters and buttering just one quarter at a time, eating slowly, and knowing that in a multiple utensil setting you always work from the outside in if the place settings are properly positioned. And use the napkin with delicacy. My Aunt Mar said that even when she was dining alone she would follow these procedures, as though someone was looking in the window at her.

During this training process, interpersonal conduct regarding how to shake hands (firmly), who to introduce to whom first, always stand erect, no slouching while seated, when introduced make certain to establish eye contact, and offer a friendly smile. All of these were stressed and noticed when not practiced.

Uncle Bill took me to his office one day and introduced me to his secretary and some business associates. It was an impressive office and I learned that he was Vice President of a large manufacturing firm. I don’t know what was manufactured. He also had me serve as caddy for him as he played golf with some business associates. He commented favorably on my handling of that social situation. As we drove home from the golf outing, Uncle Bill commented that “you can learn a lot about a man from playing golf with him. Especially about his honesty.”

While we met with Uncle Bill only at Christmastime over the years, I do recall a great deal of his shared advice. He was certain that Roosevelt and the Democrats were leading the country to ruin. I would learn that Jewish people cannot be trusted. And thrift is very important. It is interesting to recall that while Uncle Bill was ready to share counsel and advice, my father never did so. He was not a communicator. In our immediate family, my mother was the counselor and motivator.

Uncle Bill’s advice regarding thrift was emphasized on the one shopping excursion we shared. During the daytime of the 1939 visit I would play tennis with some neighborhood boys. They were good players and I enjoyed the sport from the start. Uncle Bill took me to buy a new tennis racket. Our choice was between two very different rackets. One was a top of the line racket with a leather handle that looked expensive. The other had a wooden handle and was inexpensive. Uncle Bill did not ask which I preferred, but explained we would get the wooden handled racket because I was just beginning to play and he would put tape on the wooden handle when we got home. I thanked Uncle Bill and played with the racket for the rest of the summer. Since that time, whenever I’ve had a choice between the best or lesser valued sports or other equipment for myself or someone else, I’ve always elected for the best.

The lesson for me, good or bad, was that thrift was not always the best policy.

Some years later when I was in high school, I received a letter from Uncle Bill on his corporate stationery. He said he had heard I was doing well in sports and that if I needed any equipment or financial assistance to let him know. My mother was so impressed by this offer that she had the letter framed. She took it as a generous expression by him which reflected his special regard for me. I felt the same way, but did not pursue his offer.

The Chicago vacation experience was a great one, and our cruise coming home was a surprise. The Billingtons decided to drive me home in their large Packard touring car. We traveled by way of Detroit where we took an overnight cruise ship across Lake Erie to Buffalo, New York. Not having been on a ship before, seeing the engine room, eating on board in a huge dining room, and sleeping as we sailed was great fun.

We stopped in Buffalo the next day to visit a business associate of Uncle Bill’s. Our evening dinner was quite formal, and the Billingtons expressed pleasure afterward regarding my overall deportment. I did not spill anything. I returned from my Chicago vacation with a lot of stories, and a lot of useful memories.

My Aunt Mar said that even when she was dining alone she would follow these procedures, as though someone was looking in the window at her.

Comic strips and the sports pages were primary reading for us in the 30s. My favorite was Li’l Abner created by Al Capp. It was about a lazy, not too bright, very strong hillbilly who lived in Dogpatch. He was pursued by Daisy Mae, a beautiful blond girlfriend, who he always tried to escape.

There were a lot of interesting characters in the strip. Marryin Sam was a

preacher who would perform weddings at different levels of effort depending on the price. Poor Joe Btfsplk was the world’s worst jinx who always walked around with a cloud over his head and mishaps occurred to anyone coming in contact with him. And then there was Stupefying Jones, who was so gorgeous men became stupefied looking at her.

To provide the Dogpatch girls a chance to catch a husband from this hapless group of hillbillies, “Sadie Hawkins Day” was the one day of the year when bachelors would be given a head start and would have to marry the girl who caught them. For reasons no one could understand, Li’l Abner lived in great fear of being caught by Daisy May. Sadie Hawkins Days were proclaimed on some college campuses and in some small communities.

This comic strip was read by some 70 million Americans daily. A Li’l Abner movie and a Broadway musical were produced. Al Capp would poke fun at business, politics and our culture. His story lines were topical and satirical. The strip was published from 1934 until 1977 when Capp retired.

Some of us felt that something of fun and value was gone.

While movie stars such as Clark Gable and John Wayne were increasingly popular in the ’30s, it was the sports stars who were the icons for young boys. Baseball was the National Sport and most boys knew the batting order and averages for our favorite teams and players. Stories concerning Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were highly publicized, and some of those exploits are still recalled in the next century.

Babe Ruth’s fame helped fuel the rising interest in baseball and sports in the ’30s. Sports were a most welcome diversion and escape from Depression realities. Ruth had been sent to a home for orphan incorrigible boys even though he was not an orphan. His behavior was channeled into a career in professional baseball in his teens, and hence the name “Babe”. He became the Sultan of Swat, hitting

714 homeruns which set a record not passed for a half century. Yankee Stadium became known as the House that Ruth Built.

In one famous World Series game he stepped to the plate, pointed to the right field wall, and then hit the next pitch over the wall he had pointed to. While Ruth’s personal life was scandalous, his on field performance made him a popular national hero. During one season, Ruth’s salary was greater than that of President Hoover. When asked about that, Ruth said, “I had a better year than he did.” I found it interesting that he was a left handed batter and pitcher, who wrote with his right hand.

Lou Gehrig was Ruth’s teammate and his personality opposite. As the “Iron Man” of the sport, he played in 2,130 consecutive games without missing. It was not until 1995 that Cal Ripken of the Baltimore Orioles surpassed that unbreakable record. Gehrig was a clean living man, and it shocked the sports world in the late ’30s when he became gradually disabled with a fatal neuromuscular disease called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, which was thereafter known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. At his final appearance in Yankee Stadium, shown worldwide in theaters, Gehrig referred to himself as “the luckiest man on earth.” That statement had great emotional impact at the time for the entire sports world knew it came from a young athlete who was dying. Gary Cooper played Gehrig and that scene in the move, “Pride of the Yankees” in 1942, and Babe Ruth played himself in the film.

Baseball was our National Sport and pastime in the 1930s and ’40s. We played it daily through the summer months. While I liked playing the game, I did not enjoy watching baseball. It was a too slow-moving, situation oriented game for me. Most of the players are standing or sitting, often waiting through the 3 balls and 2 strikes delay. Chess was as much fun to watch. Still, the pace and history of the game fit the ’30s well, and its popularity has remained high even though other professional team sports were emerging and challenging for the “National Sport” title.

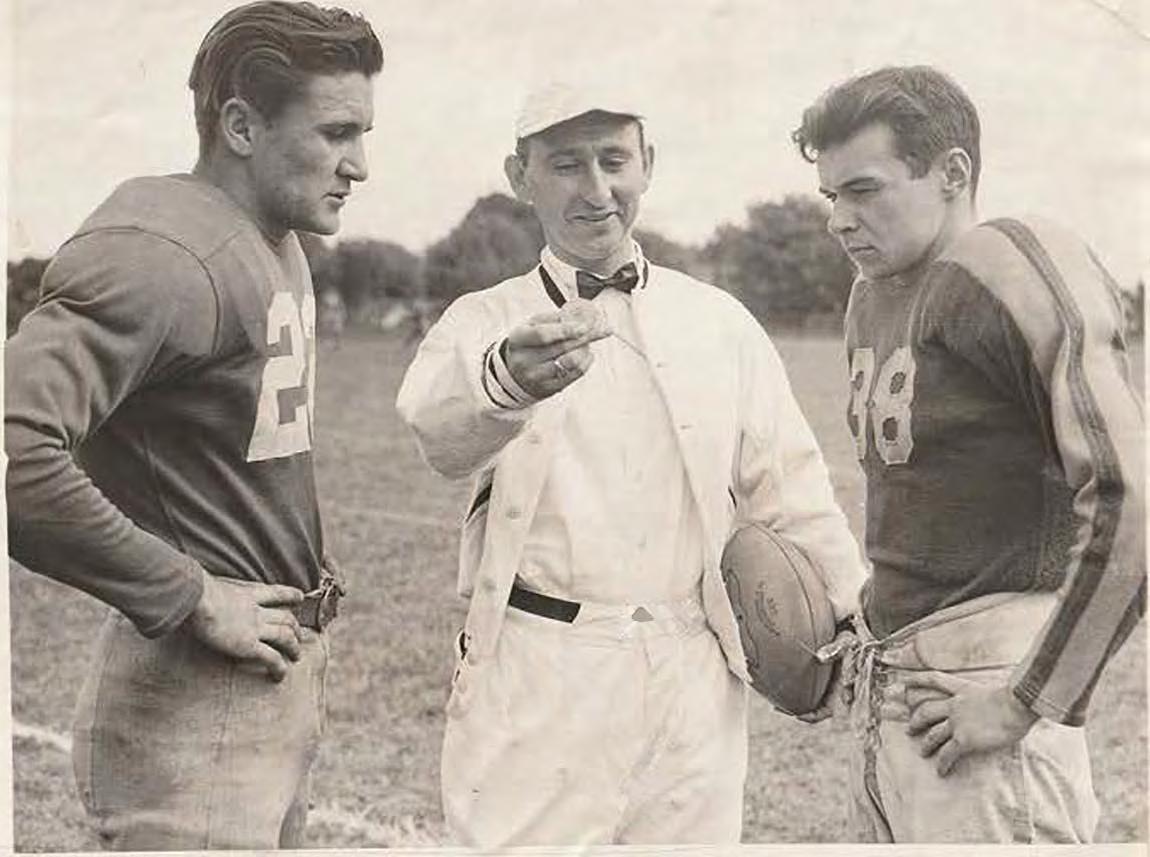

Football was highly popular at the college level, and was becoming increasingly popular at the professional level in the 30s. Then, as now, college football was the feeder system for professional teams. Red Grange of the University of Illinois

moved into professional football, and became known as the Galloping Ghost because no one could seem to tackle him.

In one college game against Michigan, Grange scored four touchdowns in 12 minutes. Grange was credited more than anyone for bringing professional football into the mainstream.

Another football great of the period who I admired was Bronco Nagurski.

He played for the University of Minnesota and then the Chicago Bears throughout the decade. Stories about him were legendary. One was that a scout from the University of Minnesota stopped to ask him directions to the nearest town. Nagurski had been plowing a field without a horse, and lifted his plow to point in the direction of the town. He immediately received a scholarship. Later playing for the Chicago Bears, he was both fullback and tackle. Players played both offense and defense at that time. During one game in Wrigley field, Bronco charged the goal line, head down, shoving tacklers out of the way, and he went right through the end zone and smacked his head on the close in wall at the field’s end. When he came back to the bench, he told his coach George Halas, “That last guy gave me quite a lick.”

That’s why I liked football.

While team sports were enjoying growth and popularity in the ’30s, two of the most famous athletes in the world were from the sports of boxing and track and field. These champions were referred to at the time as “colored,” and the issue of race prejudice haunted their careers. Negro athletes were not accepted by major league baseball and football teams. Still, great national pride was felt for their performances and they became, against all odds, the most famous athletes in the world.

Joe Louis was the World Heavyweight Boxing Champion throughout the late ’30s and all of the ’40s. He fought an astounding 170 times and won 167 of those fights. All of his fights were covered by radio and everyone was tuned in. The announcers had a way of making you see and feel the excitement. Highlight fights of Louis’s career were against the German Champion, Max Schmeling. In the eyes

of an increasingly divided world, Schmeling represented Nazi Germany and white supremacy, and Louis represented American interests. During their first match in 1936, Schmeling knocked Louis out in the 12th round. The 1938 rematch was hyped around the world. It was Nazi evil against American good.

Louis demolished Schmeling in the first round, knocking him down several times and breaking two of his vertebrae. Louis became and continued to be a national hero.

Later in Louis career he suffered through difficult financial and health problems. The Joe Louis Arena in Detroit was named after him. Schmeling and Louis became good friends after the World War II. It was ironic that after Louis died, Schmeling paid for his funeral and was one of the pallbearers.

Professional boxing was the top sport in the 1930s. A string of great champions, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Primo Camera, Max Baer, all prior to Joe Louis, were international sports idols. No athletes received greater newspaper, film and radio coverage than these boxing champions.

At my request, my father installed a small boxing area in our basement at home. My friends and I would spar, and I became proficient at hitting the light speed bag. Our heavy bag was mistakenly filled with sand, and hitting that bag hurt me more than the bag. I would spend hours practicing on the speed bag, and my parents never complained about the noise.

While Jesse Owens spectacular performance in track and field was focused on the two-year period, 1935 and ’36, he established lifetime fame. The 1936 Olympic Games were held in Berlin. Hitler and Nazi propaganda focused on German and Aryan (i.e., racial) superiority, and Hitler was present throughout the games to award medals to German athletes. But a relatively small colored athlete from Ohio State University would dominate the Olympic Games by winning four Gold Medals. Hitler left the stadium on each of these medal presentation occasions, and all of the world took note.

Owens remains the most famous track athlete of all time. He eventually pursued a public relations and speaking career, and Jesse Owens Stadium at Ohio State University carries his name.

My mother was the motivator and disciplinarian for the family. She was also very nurturing, loving, protective and caring. But, occasionally she would mistake the purity of my actions and intentions for wrongdoing. When that happened, either a large wooden spoon or a flyswatter would be called into action as the weapon of choice.

As I grew, I was able to run for it in a reasonable life saving effort. I recall one instance in which she had clearly misjudged my conduct, and was chasing me around the dining room table with the much preferred flyswatter in hand. My mother’s younger brother, Bill Shire, was visiting us at the time and he grabbed the swatter away from my mother and said, “I can’t stand to see you beat him!” Chastened, my mother backed off.

I always liked my uncle Bill.

Only one disciplinary effort on the part of by dad can be remembered. My friends and I found the family car was in the driveway blocking our basketball court. We took the car out of gear and pushed it several feet to make way for our game. As I got out of the car, my friends having pushed, I saw my father coming toward me with a large rake in hand announcing his intention to do me grievous bodily harm. I led my friends in a fast escape as we ran in six directions. I returned home some time later, making sure that the rake was back in its usual place.

The “Noble Experiment” reflected in the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawed the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages.

The Amendment was adopted in 1920 and throughout the following decade it was found that “Prohibition” did not work. If anything, demand for and use of liquor had increased and the involvement of organized crime in meeting that demand was creating serious societal problems.

Another Amendment to the Constitution, repealing the 18th, was necessary. For the first time in our Nation’s history, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th by removing prohibition from the law. The noble experiment had failed. It had been strongly advocated by rural America, and the reality was that imposition of those conservative values on the larger society did not work. Attempts to use government to dictate and enforce moral standards will always be part of life in a democratic society. Prohibition’s history should be a lesson remembered.

There were no private pools in Morrisville in the 1930s. In the summer we would swim in the Delaware River. In the winter, the Trenton YMCA and YWCA offered swimming lessons at their indoor pools. I took lessons at the YWCA.

The Delaware River was about a quarter mile wide, reasonably clean, not very deep, and had many large boulders above the water line. Families would wade, swim, and sunbathe on the rocks to escape the summer heat. One summer afternoon when I was about 7 years old, my parents took me to the river for a swim. This involved playing on and near the large boulders, and we would jump off the rocks into inflated inner tube tires. The depth of the water was about 5 feet and the tubes were used to catch us for floating support. This day my Dad was holding the inner tube, I jumped in it, but went directly through the tube and found myself under water and unable to see or touch anything.

For the first and only time in my life I experienced panic. And I had the clear and weird sense that images of my life were flashing quickly before me in my mind. Years later as I read about near death experiences during which people’s lives flash before them, I felt it was interesting that at that young age I would have

experienced that mental sensation. You would think there would have been too little life at that time to experience such a feeling.

I recall frantically wondering what was happening to me. This did not build a base of confidence for me in the water.

Later in the Navy in 1945 I experienced another swimming incident, but not life review. Although I always felt swimming was one of the best possible forms of exercise, it never developed into a physical pleasure for me.

The Great Depression of the 1930s was not all that great. Times were tough. Millions of men were out of work throughout the decade. Images of bread lines and soup kitchens serving the hungry, along with close to home stories of economic hardship, these were the compelling concerns of the time.

My father was an electrician by trade, employed throughout the decade by Kelly Electric Company in Trenton. It was a small company owned by Mr. Kelly, who we never met. My dad would walk to and from his Trenton job each day, and that involved several miles. Taking advantage of the street car would have cost money. He was paid $10 per week throughout most of the ’30s. His side electric repair jobs on the weekends produced enough additional money that we always had what we needed, but not much more.

While I was well aware of the hardships being experienced during the Depression, I was fortunate to feel shielded from those concerns.

The north section of Morrisville, including 90 West Maple Avenue where we lived, was sometimes referred to as “Cracker Hill”. I did not hear this term until my school mates at William E. Case would insist that people living where we did had to eat crackers in order to afford to live there.

This was, of course, a mistaken idea since everyone living in Morrisville was pretty much at the same economic level and shared the same uncertainties.

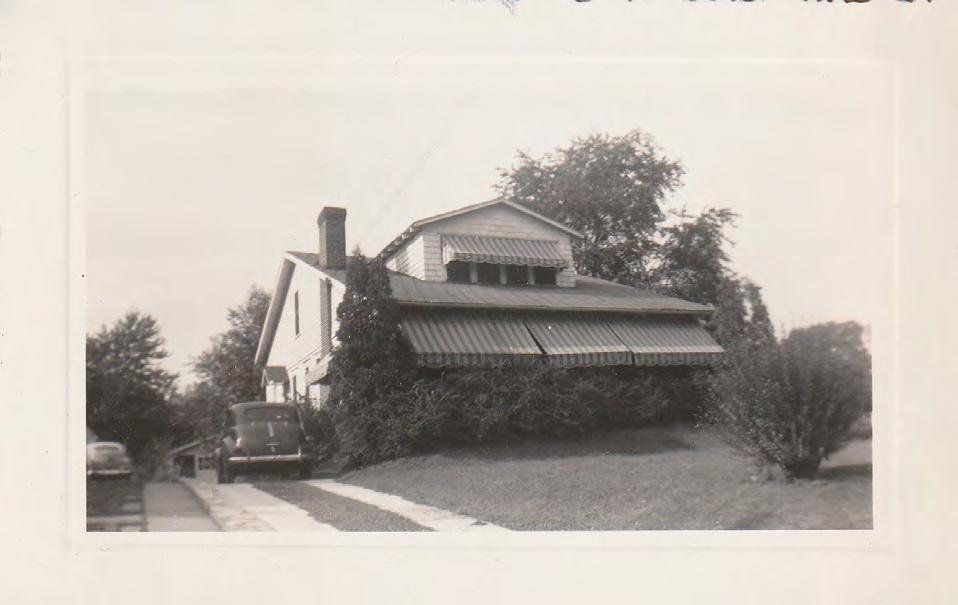

Our two story bungalow, with an added apartment of the second floor, was just

right for a family with two children. We had a good size living room, dining room, kitchen, two bedrooms, a bath, and a basement. Still, we lived in an area of town that during the Depression regularly attracted men who would come to our back door begging for food. My mother would always give them bread, sometimes with jelly, sugar, or butter. They were never invited in the house. This was sad to see.

While in retrospect it is clear our family diet was very limited; I had no sense of that. Certainly, I never complained. What was on the table we ate and liked, and that was three meals a day. We seldom had meat. If meat was available on the weekend, it would be served in stew with potatoes, carrots, and gravy throughout the next week. Dinners of dried beef or fried tomatoes, served with bread and milk, were regular staples. Breakfast was warm cereal and eggs. My school was never far from home and I would come home for lunch each day, usually for peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. We ate as a family each evening in the kitchen, after my father came home from work. Sunday we would eat in the dining room, where sometimes meat would be served. Everyone in my neighborhood was eating and living in much the same way. We witnessed privation, but did not experience it to any serious extent.

Home delivery of most daily needs was one of the advantages of the time. A bread man, a milkman, an ice man, and a mailman would come to our homes almost daily. The mailman delivered mail twice a day. Milk was delivered in glass bottles with cream on the top. In the winter the cream would freeze and expand, forcing the paper cap up more than an inch.

The ice man would deliver large blocks of ice, in sizes depending on price, that would be carried into the kitchen, sized with an ice pick, and placed in the top of the ice box. All homes used ice to cool and protect food. A pan was placed under the ice box to collect water from the melting ice. Part of my allowance duties was to empty that pan. It was interesting to watch the ice man use his pick to shape the ice. I always wondered where all that ice came from, particularly in the summer months. The ice business was a big business, involving house-to-house delivery.

While the mailman walked in making his twice a day delivery, most other deliveries were made by horse and wagon during the early part of the decade and truck during the last years. Some specialty deliveries involved horse drawn wagons and men selling vegetables, sharpening knives, collecting rags, and ringing bells to indicate the ice cream man was here. These sellers would either announce or ring bells as they moved up the street, but would not stop unless a customer appeared. The “rag man” was especially interesting for most children. He was a forbidding looking man, who we could hear coming with his loud “Rag Man!” proclamation as he moved very slowly up the street. I never saw him actually collect a rag, and I don’t know what he did with them. I know of no modern counterpart to his job.

Homes in Morrisville were heated by coal. Shoveling coal and keeping a fire burning throughout the winter was no easy task. It was delivered to most homes on a shoot directly from a coal truck into the basement. Because of window locations, that was not possible in our home and the coal had to be moved by wheelbarrow into our coal bin. That was labor intensive and involved extra cost. We shared in that work. Fire building and maintenance were art forms. The home furnace was permitted to dampen down at night, and required re stoking each morning. Thankfully, my father handled this chore, as he did any other requiring any semblance of skill.

We also had a fireplace in our living room, which made that room especially cozy and warm in the winter. In summer, our air conditioning was obtained by opening the windows. We also enjoyed a very nice screened in front porch where we spent a lot of time in the summer. Awnings were placed around the porch, and also shielded most of the house windows.

Our family had a car throughout my lifetime. I don’t remember the make of cars we had, but we did have one with a rumble seat, which was a seat in the back of the car that could be opened or folded down. It was fun riding in that back seat. While cars had fully replaced horses for family use in Morrisville, travel by car presented some special challenges. To start the car, you had to use a special

crank which was inserted at the front of the engine. This bent-handled device required that you turn it hard in a clockwise fashion, to turn over, or start, the engine. This was not easy, and the crank did on occasion kick back, hurting and even breaking an arm.

Starting a car with an ignition key was not experienced by us in the ’30s. Another very real challenge in traveling by car was the frequency with which tires would go flat. There was a rather firm outer tire, and a more fragile inner tube that was pumped with air. It was the inner tube that had too little tolerance for distance. If we went to the shore for the day, it seemed more likely than not that one of the four tires would not complete the trip. A flat tire required jacking up the car, removing the tire, removing the inner tube, patching the inner tube, then replacing the inner tube, and re inflating the tire. Part of this scenario invariably involved the use of unacceptable language by my father, which further inspired my mother to lead me to church each week to be sure I recognized that God’s name should not be used in vain.

Every Sunday morning my mother took me to church. The Morrisville Episcopal Church was not “high church,” involving an almost Catholic-like ceremony, but it was high enough for me. I can still recite its ritual and liturgy. There was never any question that I would be in church on Sunday.

My brother became an acolyte in the church, assisting the Minister in the rituals, and my mother was most pleased with that. My mother seemed satisfied that I was attending without complaint, and to her that was a good sign. My father never went to church.

Some of my young social activity involved participation, primarily sports, at the local Presbyterian Church. My brief career in the Cub Scouts was also at the Presbyterian Church. I had some trouble with all the perfection required of me in the “Scout’s Oath.” Other than this church-related activity, and occasional church suppers generally run by my mother, I was not focused on the spiritual side of life.

The phone presented another interesting challenge during this period. I knew no one who had a private phone line. Everyone had party lines that involved three or more other homes sharing the same phone line. When you picked up the receiver (i.e., the cone shaped unit you held to your ear), you first had to listen to make sure no one else was on the line. If you heard talking, the polite thing to do was hang up and call later. You could hear a clicking sound if someone picked up the phone while you were talking, and it was appropriate to announce that you were using the line. Privacy was a problem. It was likely you would know some of the other party line partners, but you could not be sure you knew all of them. The phone company did not tell who was on your line. The fewer on the line, the more expensive the monthly cost.

The lack of privacy notwithstanding, the inconvenience of the party line was accepted as the way things were. Lengthy teen age conversations were not as likely, and it was certain that others on your party line were in your immediate neighborhood. I heard some grumbling regarding nosiness, but nothing that was hostile.

We had a great little black dog in the ’30s named Wally. She was named after Wallace Simpson, the woman for whom King Edward of England abdicated the British throne. It was the scandal story of 1937, with Ms. Simpson being an American divorcee who could not be accepted as Queen. Edward’s international broadcast that he “could not move forward in life without the love and support of the woman” he loved, was a somewhat sad fairy tale. The couple married and became the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. They lived together throughout their lives, traveling and always in the public eye.

Our little dog, Wally, was more social that we would have liked. Fixing dogs was not something regularly done in Morrisville at the time. This clearly worked to Wally’s adventurous advantage, since she delivered more little pups than we knew what to do with. Still, she was our long time friend, a wonderful little, child friendly, dog.

Neither of my parents were graduated from high school. My dad stopped going to school before the 8th grade to work in the green houses on the family farm in Croydon, and my mother began working as a phone company operator before completing high school in Bristol. My mother determined early, and clearly communicated to me, that I would be the first in the Lorimer line, or her line, to graduate from college. That proved true.

School began for me at a Quaker Friends School in Fallsington, Pennsylvania, a few miles from Morrisville. Kindergarten and first grade were at this school. My mother would drive me there each day. The Quakers were a gentle Protestant religious group, later known for their strong pacifism. It was fascinating to me that our teachers would never use the pronoun “you”. That was considered to harsh. We would be referred to as “thee” or “thou.”

Under this gentle quaintness, I learned to read and write and have only most pleasant memories. One of those was to have been chosen to lead our first grade band, with baton and all, for the entertainment of our parents at the school assembly. That was my first taste of power.

For the second grade and subsequent years, I returned to Morrisville schools. Capitol View elementary was just a block from my home for my second-grade classes. My future wife, Jean Whittaker, was in the same school, but classes were divided by first and second halves of the alphabet and we were not in the same class and did not know each other.

Third through fifth grades were at William E. Case School on Bridge Street in Morrisville. This school was well over a mile from home, but I made it home for lunch each day. I also recall serving on the school Safety Patrol during my fifth grade, at a corner where children crossed on North Pennsylvania Avenue. My job was to help younger students cross that main street safely. The fact was that Jean Whittaker would have had to cross that street at that point to get to school. Jean

insists she does not recall receiving assistance from me in this early leadership role. It is certain that even then I was focused on protecting her, and it would seem only right that some measure of appreciation be expressed, however belated.

The Morrisville High School building housed grades six through twelve. The school had separately marked entrances for “Boys” and “Girls,” but since classes were co-ed this entry separation was not enforced. Throughout high school there is no question that sports, not academics, was my main and most compelling interest. Gym classes and recess sports periods were where I felt best positioned to perform and excel. Neither schoolwork nor homework captured my interest, although I had no trouble obtaining passing grades. Grades of B and C were it for me. Fortunately, there were no Fs.

These early school years were fun, and most of that enjoyment came from sports activity.

There was a large field on the east side of our home. That area was mowed and maintained by my father, even though we did not own it. That is where nearly all our games were played. My friends from the neighborhood and surrounding area would congregate there in the summer and after school. We would choose up sides and play whatever sport was in season.

Baseball and football were the main sports, and we also attached a basket to my garage for games during that season. I had the double good fortune to have the community play area at my home, and also to be reasonably good at most sports. Basketball was an exception. I could do everything well in that sport except put the ball in the basket. That was a problem, since that is the main objective of that game.

My parents always encouraged my interest in sports. It was never “You can’t play, you must study.” Maybe that was because my mother tried that with the piano, and it didn’t work. She seemed convinced that my large hand span would translate to great skill with the piano, but she was proved wrong. It is likely her

acceptance of my interest in sports came early. She often told me that on Christmas when I was 3 years old, they had laid out what they thought were a good range of toys for Jimmy from Santa Claus.

But, when I came into the living room on Christmas morning, I spotted a small hassock and fell on it immediately exclaiming, “Fut-a-ball!”. That was all I would play with, and there began the unpromising signs for a piano career.

There is also a recollection of my athletic 6th Birthday Party. My friends and I were playing parachute jumping on the swing in our back yard. That involved swinging as high as possible and jumping off at the top of the swing. On one of my jumps, I caught my arm in the swing rope and broke the forearm. I recall that put a slight damper on the party. Thankfully being a party pooper was not yet in the vernacular.

Another example of commitment to sport, also providing some insight on the economics of the time, was my purchase of a prize catcher’s mitt. In the summer of 1938, I saw a beautiful black baseball catcher’s glove in the window of a sporting goods store next to the Lincoln theater in Trenton. The glove cost $3.50 and that was expensive. My parents agreed that I could buy the glove if I paid for it with my own earnings. There were no credit cards or even credit at the time. Everything was done on a cash basis.

The only exception was a layaway plan, which was a common practice. I put 50 cents down and agreed to pay 25 cents per week. The store set aside the glove for me. Each Saturday thereafter I walked to Trenton, paying 25 cents. To my knowledge there was no interest or carrying charge, and finally near the end of the summer the glove was mine. My weekly chore allowance had been used, and the result was a most prized possession.

It was a good lesson for me.

Perhaps the most fortuitous sports happening for me during the 1930s occurred during the summer of 1939. I was visiting for a week with my grandmother and

uncle in Bristol, my mother’s mother and brother – again being lent or farmed-out to my grandparents during the summer.

After playing baseball with some other boys one afternoon, we went to a nearby garage that had been equipped as a workout gym with weights and benches. I had not seen this equipment before, and was very impressed with the physique of the young man who was working out there. He demonstrated and explained how he had developed himself through training with weights. He made clear it was not a question of seeing how much you could lift, but rather training with a heavy weight doing repetitions and sets for each of the various body parts. I had been reading Charles Atlas’s ads claiming that through use of his system of “Dynamic Tension” even a ninety pound weakling could become a real man. I doubted that even then, having heard that Atlas actually obtained his build and strength from weight training. Working progressively with barbells made sense to me.

Immediately upon returning to Morrisville, I called my good friend, Jim Murray, and told him about what I had seen in Bristol. We had become friends in school and even though he lived in another section of town, we had shared our interest in sports and becoming stronger athletes. Jim’s recollection of my report to him is that I expressed with great enthusiasm that, “I have found the secret! What we need to do is get some weights and start training hard with repetitions and sets!” Ready to be convinced, Jim agreed and we both proceeded to persuade our parents that they should help us buy barbell sets from York Barbell Company in York, Pennsylvania.

Jim Murray would later go on to become Editor in Chief of the York Barbell publications, the leading magazines in the field at the time.

Soon after receiving our weights we started training, mostly together, sometimes at his house and sometimes in my side yard. My father often complained that he was getting stronger than us since he was the one who would bring the weights in the house after we had worked out. Apparently, we were too tired to complete that last part of the workout. I also recall that on one occasion while working out in his family’s living room, Jim Murray dropped a weight from overhead and it

cracked right through the floor. We went to the basement and tried to push it up and patch it from there, but the crime was done and I left Jim to face the consequences. We were both lucky to have the understanding parents we did, for we considered it likely we would have to hop a freight train across the street from where Jim lived, in order to escape the wrath that never came.

There can be no question that this early training with weight equipment gave Jim Murray and me a competitive strength advantage throughout our high school years. I always had the feeling, as did he, that I was stronger than my opponents. Weight training gave me the feeling that I had the edge.

The great summer pastime was baseball. We had two major league baseball teams in Philadelphia, the Athletics and the Phillies. On special occasions we would get to go to one of these major league games. The famous manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, Connie Mack, and the players, their positions and batting order, were known to my friends and me.

Local baseball games, other than our own sandlot games, were played on ”The Island”, which was a large recreational area on the river side of the town. The island had been formed as the result of floods during the early years of Morrisville’s history. Both high school football and baseball games were played on this Island field during the 30s.

One special summer highlight was Donkey Baseball. This unique game was played just once a year, and most of the town would turn out to see it. The attraction was that the town Mayor and many other local dignitaries were good sports enough to play a game of baseball using donkeys to move between the bases.

The ball would be pitched and hit as usual, but when the ball was hit the runner had to immediately mount a donkey and try to reach first base before the ball. This was not easy for the donkeys were not at all cooperative.

Everyone enjoyed the fun of seeing the city leaders look ridiculous in their efforts to make the donkey move around the bases. If they didn’t make it on the donkey’s back, they would try pushing and pulling.

The games were very low scoring because it was most difficult to move all the way around the bases. Some handling of the ball in the field also had to be done on the donkey’s back. Men would have trouble mounting the donkey, and even more difficulty staying on. Even though these donkeys were traveling on some Donkey Baseball circuit, they did not seem to recognize the need for getting around the bases. But it was always an evening of great community fun, with a lot of laughs at the expense of our town leadership.

Families were inclined to stay close to home during the Depression years. Travel was expensive and even a day at the shore involved gas expense and replacement of the frequent flat tire. Family evenings at home were most often centered on listening to the radio.

Radio broadcasts were done live. Just as with the early days of television, it was believed the public wanted live entertainment not recordings. And the quality of recordings themselves was not yet well developed. News reports, daytime soap operas, band music, comedy shows, action stories – all were presented live. Sound effects contributed greatly to a sense of reality.

The early evening news featured well known voices such as Lowell Thomas, Gabriel Heater, and Walter Winchell. Thomas was a straight news presenter, Heater was inclined to the more dramatic, and Walter Winchell was the most flamboyant and gossipy. Winchell’s fast paced opening, to the sound of telegraph tapping in the background, was “Good evening Mr. & Mrs. North American and all ships at sea – let’s go to press!” His then quick capsule of the news was focused on personalities. He was the most listened to newscaster.

Daytime radio presented soap operas with the traditional heavy load of commercials. The audience was primarily female, although my mother did not

listen to soap operas. But when I visited with my Aunt Margaret in Chicago on two different Summer occasions, she insisted on a two hour period of afternoon silence each weekday while she listened intently to “The Romance of Helen Trent” etc. That was her afternoon, widely shared, escape.

Following the evening radio news, the most popular choices were between comedy programs and action adventure. It has always been interesting to remember that while radio provided no visual image, that did not detract from our ability to mentally visualize the action being portrayed by voice and sound. In fact, your imagination could conjure up images of the action that were without limit. When the Lone Ranger mounted his great horse, Silver, and rode off with a hearty “Hi Ho Silver – Away!” – one could hear the hoof beats and see them galloping across the plain as those just saved exclaimed, “Who was that masked man?”

Then there was “The Shadow,” who had the ability to cloud men’s minds (never any mention of women) so that they could not see them and yet he could work in the service of justice. A voice always announced, “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!” And we knew he did.

Jack Armstrong – The All American Boy – was another popular program involving stories of a heroic young boy, the ability to subscribe to a secret code book, etc. that portrayed an innocence and purity of mission against evil that was conquered each evening. Jack was a role model who kept us glued to the radio.

The best escape for the entire family during the ’30s were the great comedy shows on radio. Jack Benny and his wife, Mary Livingston; George Burns and Gracie Allen; Fibber McGee and Molly; Amos and Andy – all produced evening laughter for the nation.

Jack Benny was a likable but penny pinching miser. When a robber confronted Benny with “Your money or your life!” – Benny played the pause better than any comedian – with silence. The robber then angrily repeated “I said – your money or your life!”

An exasperated Benny replied, “I’m thinking – I’m thinking”!”

Amos and Andy were played by two white comedians, as hapless, not too bright young negro small business operators. This portrayal and their later films, done in black face, would be politically unacceptable 50 years later. But, in the 1930s the program was humorous and highly popular. Typical was their proud use of an office inter com system. Andy placed the buzzer on his secretary’s desk. When he wanted to call her, he would yell out, “Will you buzz me Miss Blue?” She would then push the buzzer and come into his office. The inability to cope and general ineptness were the source of the humor, and such racial stereotyping was understood and accepted uncritically at the time.

Fibber McGee and Molly were a husband and wife team – as were George Burns and Gracie Allen In both programs the husband was the not too smart straight man and the wife had the put-down punch lines. Fibber McGee also had a popular and anticipated sound effect in each show that involved him opening what became known as “Fibber McGee’s Closet.” Upon opening the door of that closet, a tremendous sound of “everything” falling out was made.

It always produced a laugh and was one of the best examples of the great imagery skill produced by radio sound effects professionals.

Live musical presentations were also a great part of radio’s attraction. It was the big band era and Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw’s Bands, with singers Helen O’Connell and Peggy Lee, were among the most popular. Although recorded music was highly popular, the insistence remained that on radio live performance was what the public wanted. One particular noteworthy musical presentation was made on radio on Armistice Day 1938, when the famous singer, Kate Smith, broadcast her version of “God Bless America.” It became her signature song, and since second only to the “Star Spangled Banner” in patriotic popularity.

The “Fireside Chats” of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, during which he chatted by radio with the entire nation, were regularly presented by the President with great political effectiveness.

The first radio broadcast to all 48 states was accomplished in 1928, when the cowboy philosopher Will Rogers spoke to the nation on the NBC network. President Roosevelt was a man with great communication skill, and the first national politician to take full advantage of the national radio network. His most famous and encouraging message that “We have nothing to fear – but fear itself!” was delivered to an anxious nation by radio at a time of need for such leadership assurance. Radio linked the nation with immediacy and intimacy, and Roosevelt used that new media capability to full advantage.

One of the most interesting examples of the impact of national radio on our society occurred on October 30, 1938. A young actor, Orson Wells (who was also the voice of “The Shadow”), was presenting a program on CBS about H.G. Wells story of “The War of the Worlds.” Although the program led in with an explanation of story telling, the presentation by Wells had so much realism to it that the, “News Bulletin concerning the invasion by men from Mars” set off a nationwide panic. Phone lines were jammed around the country, hundreds of New Yorkers ran into the streets with handkerchiefs over their mouths to guard against Martian gas, and people were checking into hospitals around the country in shock.

They were also calling newspapers to inquire when the world was coming to an end. Wells became famous and there was wide reporting and amazement about the impact of this hoax. Wells later played the lead role in the Academy Award winning move “Citizen Kane.”

Still another dramatic us of the radio in the 1930s involved the execution of Bruno Hauptman for the kidnapping and death of the Charles Lindbergh baby. Lindbergh was a heroic figure who was the first man to fly solo, in 1927, across the Atlantic Ocean from New York to Paris. He did this in 33 hours in his private plane, The Spirit of St. Louis, and he returned to New York for a ticker tape parade and personal fame. Living in Princeton, New Jersey, the country was shocked in 1932 when his baby son was kidnapped for ransom. Lindbergh paid the $50,000 demanded, but the baby was found dead soon after at a point not for from their home. Two years later in September 1934, Bruno Hauptman, a German immigrant, was arrested and charged. The evidence appeared clear and involved

some of the money being found in Hauptman’s home, and some matching of the wooden ladder used in the kidnapping with wood used by Hauptman. Bruno insisted that he was innocent, but he was rather quickly sentenced to death.

The electrocution was broadcast in great detail by radio. Just about the entire nation, my own family joining with neighbors at near midnight at Saturday evening, to hear Gabriel Heater describe and countdown to the event. Revisiting the evidence, would a reprieve be granted, what would be Hauptman’s last meal and statement.

With the count down by seconds to midnight, Heater pronounced, “Bruno Hauptman is dead!” I have not since seen or heard of such a detailed and descriptive focus on a public execution. Radio brought that imagery into our living room in a way we will always remember.

The first Major League baseball game played at night under lights was at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field on May 24, 1935. The game was between the Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies. The prospect of nighttime baseball raised many tradition bound objections. One politician proclaimed “Baseball must be played in sunlight – as God intended!” But the night game attraction had begun.

The Cincinnati Reds also participated in another interesting first. On August 26, 1939, the first television broadcast in history was of a baseball game in New York between the Reds and the N.Y. Dodgers. Only 400 homes in the City received the transmission on very small TV screens. But the game was televised. Development of television technology and transmission was shortly thereafter put on hold for the duration of World War II.