Jill Lowe Facts and Froth

Alchemy and awe collide in the bubbling vats of fermenting indigo.

How so? What is so mysterious?

Knowing a little of the extraordinary process needed to produce the magnificent sixth color of the rainbow will illustrate the justification for the awe in the vats. Because, until late 19th century when synthetic indigo became available, any extracting of the dye from the tiny leaves of the indigo plant was extremely difficult

This color of deep midnight is intoxicating and no color has been prized so highly or for so long, with such a power to bewitch.

Who would know that the magic of indigo dyeing, combined with the french phrase “bleu de Genes” (blue of Genoa) - referring to the Genoese navy’s durable pants sold though the Harbor of Genoa, would give us BLUE JEANS? It was those pants for sailors from Genoa around the1800’s, combined with cloth from the French town “de Nimes” (denim) which would give us the ubiquitous piece of clothing.

The development of what we now know as blue jeans was the work of two enterprising immigrants. In California in the 1850s, a German dry goods merchant named Levi Strauss sold blue denim work pants to local workers. One of his customers, a Latvian tailor named Jacob Davis, regularly bought cloth from his Levi Strauss & Co. wholesale business. After negotiations and patenting, business was commenced by the two men on May 20, 1873. Some consider that day to be the official “birthday" of blue jeans.

With all natural indigo dye coming from the leaves of the plants, much was to change when in 1883 Adolf von Baeyer, identified the molecular structure of indigo enabling the synthetic version of indigo.

And so today almost all indigo is from synthetic processes, resulting in deeper indigo being available with a more uniform color.

Denim is blue on the front and white on the back because only the warp yarns are dyed while the weft yarns are left naturally undyed or bleached.

The very special distinction of indigo dyes from other dyes.

Indigo is a “vat dye” meaning a chemical reduction process is needed in water, to allow the dye to become soluble, in order to bond with fabric fibers. This is unlike most other dyes that simply dissolve in water and attach to the fibers directly.

One extracts the dye from the tiny leaves of the indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria) - a precarious, time sensitive endeavor. Or one can purchase the pigment in cakes or powder from natural indigo companies. Some enterprising home gardners keep “dye gardens” for the purpose.

The insolubility of Indigotin (the dye component of indigo powder) as described above, has resulted in various recipes to achieve solubility.

All indigo vats need three things and Michel Garcia the botanist chemist in France has a well known recipe and is followed by very many dyers of indigo. (one can find much of his wisdom on the internet) The 3 necessities for an indigo vat:-

1) indigo pigment

2) warm water with an alkaline base such as pickling lime - to help dissolve the indigo

3) reducing agent such as fructose- to remove excess oxygen

That’s why indigo is magic! From tiny green leaves, a succession of chemical reactions transforms the plant material into a blue indigo fabric -the most famous blue of all time.

The pathway to our blue jeans of today commenced at least 5000 years ago.

Around the world, plants that form the indigo pigment are the only natural sources of the blue dye. The processes to set the pigment into soluble form that can attach to a textile have developed independently in many cultures, especially China, India, Iran, Greece and Rome and from approximately 1400 years ago in Japan. The global migration of indigo not just as a commodity but as a body of knowledge is a result of countless scientists and practitioners mastering the art.

In Japan, the dying with indigo is known as Aizome and initially was exclusively used in the garments of the Imperial Court in the Heian Period (794 - 1185). Over time, the colors of aizome were adopted by the warrior class who started to wear indigo-dyed garments with the dye having the added benefit of strengthening the fabric.

By the 17th century indigo production had increased exponentially in Japan, to be one of the world’s most prolific indigo manufacturers. At its peak the country held over 1,800 indigo farms. During this time, indigo tones became so widespread that an itinerant travelling scholar from Britain labeled the colour “Japan blue,” a name that has stuck ever since.

As synthetic variants took over, the traditional manufacture of aizome in Japan has slowly faded away, with only four sites dedicated to this fine art still in production today. One of these is the Tokushima Prefecture on Island of Shikoku which dates back to the 12th century.

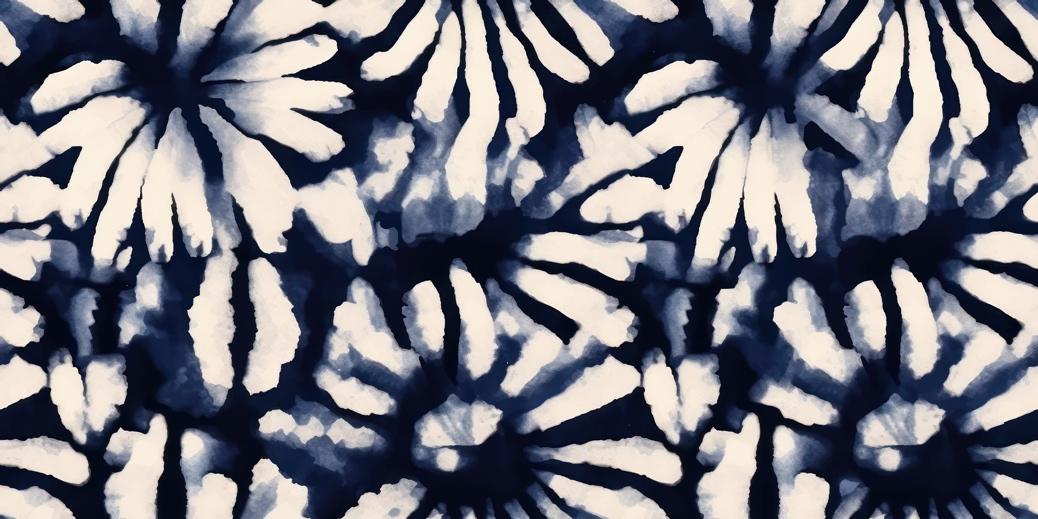

One of the hallmarks of the indigo dyeing in Japan is the shibori tie-dyeing technique. Visitors to Tokushima can immerse themselves in a world of indigo. One can experience the traditional art of aizome and return home with some unique, traditionally crafted Japanese items. Aizumicho Historical Museum (Ai no Yakata) in Tokushima is an historical museum where visitors can dye their own fabric using aizome techniques under guidance and supervision. Put this on your “must do” list for your next visit to Japan?

The impact of indigo is worth delving into and is most easily done though publications such as these.

Indigo - in search of the color that seduced the world by Catherine McKinley is brimming with rich, electrifying tales of the precious dye and its ancient heritage.

This is the ultimate reference on indigo dyeing techniques across the world.

Gloriously pieced together, much like the fine garments it portrays, this colourful volume takes the reader on an international tour of indigo-coloured textiles.

Here follows some glorious images of the magical color of indigo, its dye processes and some products.