ARGUMENT :

The main argument of this paper is that inclusivity has to be the foundation of architectural design. Traditionally, architecture has been considered as a balance of technology, aesthetics, and functionality, but as W.Fox points out, every design decision is a matter of ethics. The built environment is deeply implicated in shaping societal structures and relationships.4 Design choices not only add to or diminish the human experience but also mirror the power relations and social inequalities that are present in any given culture. Therefore, architecture cannot be considered as neutral it has to be actively involved in the power structures and challenge them by promoting inclusivity and equity.

This argument is supported in Papanek’s socially responsible design principles. Papanek emphasizes in Design for the Real World that designers should prioritize the welfare of users who face the greatest vulnerability.5 The ethical framework presented by Henri Lefebvre in The Production of Space finds support in Papanek's argument. The social nature of space emerges from political and economic forces according to Lefebvre in Production of space. The architect should treat space as an active component which both shows and strengthens social standards and institutional frameworks.6 Design inclusivity extends past physical accessibility of spaces because it demands consideration of social and political space elements which create barriers for groups including people with disabilities and elderly individuals and

marginalized communities.

The authors Colomina and Wigley in Are we human build upon this idea by discussing how architecture influences human identity formation. According to the authors architecture maintains a direct connection to human experience because the spaces we live in help form our identity and social connections with others.7 This overall understanding demonstrates why inclusive design matters because it allows all people including those from different social backgrounds to have effective interactions with their built environment. Architecture should create environments that promote social connection and foster a sense of belonging.

Mossop in her critical review Design for Social Justice: A Critical Review of Practices in Architecture and Urban Design challenges architects to integrate social justice into every stage of the design process. She argues that the responsibility of architects extends beyond functional and aesthetic considerations to include their role in addressing inequalities and fostering a more equitable society.8 This shows the increasing need for architects to be more socially responsible and not only focus on design but also on the impact of the built environment on communities.

The presented arguments establish inclusivity and social justice as a moral necessity which demands architectural practice to change direction. Architects need to evaluate both the functional and aesthetic aspects of their designs and their impact on social justice during the design process. Architects who prioritize inclusivity create built environments which serve all communities including historically marginalized groups thus advancing equality and justice throughout society.

Field Of Reasearch : :

In the early 1st century BC, the Roman architect Vitruvius laid the foundation for basic principles of architectural ethics. He proposed that all buildings should have three attributes: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas strength, utility, and beauty. Philosophical foundations were laid by Immanuel Kent addressing the concepts like duty, autonomy and universalizability in architectural responsibility and public space. Later on carried by some modern contemporary thinkers like Le Corbouseir, Jane Jacobs and Christopher Alexander and along the way Jane Jacobs was the first one who challenged top-down urban planning and emphasized bottom up, community driven development and advocated for social vitality, mixed use neighborhoods, walkability, and diverse public life, later on various contributors eventually expanded and added aspects, field of architectural ethics currently consists of multiple dimensions which examine the social and cultural along with environmental duties architects handle while designing buildings. The main priority in this domain requires architects to design spaces which fulfill both aesthetic requirements and functional needs while specifically serving vulnerable and marginalized individuals.

One of the influential contributor is Papanek, in design for the world he emphasizes that designers must prioritize societal welfare through their work while maintaining awareness of social cultural and ecological design consequences.9 The designer needs to focus on the social and cultural and ecological effects which result from design. This perspective calls for a design practice that serves the most vulnerable populations, ensuring that all people, regardless of physical or social characteristics, have equal access to spaces and opportunities.

W.Fox in Built environment and ethics supports this idea by pointing out that the built environment actually shapes social, cultural, and environmental outcomes. He states that The built environment is deeply implicated in shaping societal structures and relationships.10

This underscores the ethical obligation of architects to recognize that design decisions can either reinforce or challenge societal power structures. Architects must, therefore, engage in practices that promote inclusivity and equity, and that their work does not perpetuate inequalities but rather fosters a more just society.

The Right to the City by David Harvey extends the analysis by showing how urban space functions as a battleground for disputes about access and rights. According to Harvey the right to reshape urban environments directly connects to the right to the city because the right to the city is, above all, the right to change it.11 Architects have a dual responsibility according to this viewpoint because they must both design buildings and make sure these buildings serve to advance social justice goals in urban areas. The argument supports inclusive design which must operate within urban settings to provide equal access for all residents including those who have been historically denied urban development benefits.

Donald Norman in The Design of Everyday Things presents a user-centered perspective by recommending spaces that are both intuitive and accessible. Norman emphasizes that good design is as little design as possible which demonstrates the significance of straightforward and accessible design.12 The design principles of Norman align with Papanek's emphasis on human welfare instead of aesthetic or technological complexity. The usercentered design principles of Norman direct space creation to meet the requirements of all people regardless of their physical or cognitive abilities.

In Architecture and Capitalism Deamer examines economic power dynamics that control architectural practice by showing how capitalist systems produce buildings which benefit only a select few instead of serving the broader public. According to Deamer architecture operates under capitalist systems in constant conflict with its ability to create inclusive spaces.13The analysis presents architects with an ethical challenge because they must navigate capitalist systems while being

forced to choose between profit and social responsibility.

Richard Sennett (2004) in The Ethics of the Built Environment examines how architecture influences social interaction and community feeling. Sennett states that architecture functions beyond societal values because it actively forms those values14 which supports Colomina and Wigley’s in Are We Human position that architecture determines human identity. Sennett stresses social integration through inclusive design which creates social cohesion and mutual understanding.

Lorna Fox in Socially Responsible Architecture A Call to Action for the Next Generation of Architects presents a strong argument for the immediate integration of social responsibility into architectural education and practice. According to Fox, future architects must be trained in a way that combines functional and beautiful space design with the ability to address vital social issues.15 Fox’s call to action demands architects to design with awareness of their work's social impact while urging future architects to make social justice their fundamental practice principle.

Context :

The ethical need for inclusivity emerges when urbanization increases while social structures become complex and global mobility grows. The changing demographics of urban areas require built environments to adapt to these population shifts. Architects must address immediate issues which include disability access and economic inequality and racial segregation. The urgent needs of marginalized communities remain unaddressed by many designs which continue to serve the interests of privileged few groups.

Method :

This paper uses critical analysis of primary and secondary sources to discuss the ethical imperatives of inclusivity in architectural design. This paper attempts to synthesize the theoretical frameworks proposed by Papanek, Lefebvre, Foxand Colomina and Wigley in order to

develop a comprehensive understanding of how inclusivity can be integrated into architectural practice. The method is to look at both the theoretical principles of inclusivity and the practical problems that architects have in trying to implement these ideas. In addition to primary sources, secondary sources such as Norman, Harvey, Deamer, and Sennett are used to further explore the complexities of creating inclusive spaces within the broader context of contemporary architecture.

Sources :

The main sources of this paper establish basic ethical principles which support inclusive architectural practice. Papanek establishes in his book Design for the Real World that architectural practice must prioritize inclusivity as its fundamental principle. The ethical duty of architects to serve marginalized groups matches his analysis of how design focuses excessively on aesthetics rather than social responsibility. The Production of Space by Lefebvre extends this concept by demonstrating that physical space derives its nature from social political and economic elements. The architect must analyze their designs because they either reinforce or transform existing power dynamics in society according to his findings. Fox’s Ethics and the Built Environment supports the idea that designers must evaluate the extensive social impacts of their work while promoting inclusive practices throughout their entire design process. The authors of Are We Human? extend this knowledge by explaining how architecture functions as a relationship mediator between humans and their identities while advocating for architects to build spaces that foster social bonds and identity acceptance.

The practical implementation of inclusive design in architecture is discussed in Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things and Harvey’s The Right to the City. Norman’s user-centered design approach stresses the need for creating intuitive and accessible spaces, while Harvey’s work stresses the need for architects to consider the broader

The Ethics of the Built Environment stresses the role of architecture in fostering social integration.

The primary and secondary sources together establish both theoretical and practical evidence that inclusivity needs to become an essential principle of architectural ethics to guide architects in designing spaces that provide equal service to all society members.

DISCUSSION

Architecture is ethically charged, it can never be neutral, every designed space bends the fabric of life in many dimensions

Architecture is never neutral. Every architectural decision whether deliberate or unconscious produces effects that include some while excluding others. As Warwick Fox asserts, “architecture is not ethically neutral because it always manifests and reinforces, to some extent, social values and power structures”.16 Design, therefore, functions as a moral act it structures access, visibility, and power. Whether we consider economic, emotional, or physical dimensions, every spatial configuration privileges certain groups while potentially marginalizing others.

Even the concept of inclusivity is inherently relative. It is defined by a collective subjectivity that reflects the needs, perceptions, and identities of a specific group. As such, what is inclusive to one group may still be exclusionary to another. This is not unlike the processes of natural evolution, where certain traits are selected for and others left behind. Complete inclusivity in architectural design, like universal adaptation in evolution, remains an unattainable ideal within the constraints of our social and physical world. However, this does not absolve architects of ethical responsibility. Rather, it reinforces the necessity of employing adaptive design strategies approaches that respond to changing needs, diverse bodies, and shifting cultural landscapes. In doing so, architecture can cultivate a more inclusive “fabric of life,” even if it

can never be universally inclusive.

This ethical imperative becomes clearer when situated in a historical and socio-political context. Early human life, shaped by a nomadic huntergatherer existence, produced impermanent, mobile shelters. With the advent of agriculture and fixed settlements, the built environment began to reflect and reinforce new forms of social, economic, and political organization. As land gained symbolic and material significance, so too did architecture become a medium for establishing territorial claims, hierarchies, and enduring inequalities. Thus, the built environment has always been entangled with systems of power.

In our contemporary, urbanized world where most people live indoors and rely on built environments for access to essential resources architecture plays a central role in shaping human experience. As Colomina and Wigley argue in Are We Human?, “Architecture is not simply a platform for the programs of the day, but an active agent in the construction of how we understand ourselves”.17 The authors highlight that architecture “regulates behavior, communication, and even bodily performance,” underscoring its role as a medium through which social norms, cultural identities, and interpersonal relationships are formed.18 Far from being passive, architecture actively conditions the ways we live and perceive ourselves and others.

This perspective aligns closely with Fox’s assertion that “design choices always have political, economic, and social consequences”.19 For instance, urban planning decisions that prioritize highways and private vehicle access over pedestrian pathways systematically disadvantage those who are elderly, disabled, or economically marginalized. These spatial configurations do not arise in a vacuum; they mirror and reinforce dominant social structures.

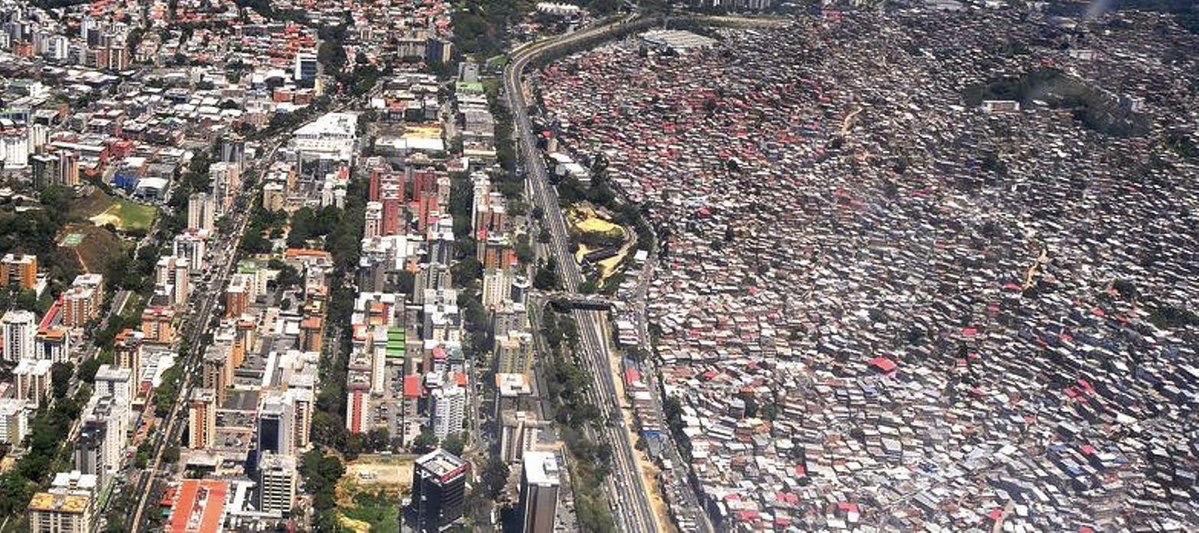

Fox warns that such designs, especially those that “serve primarily wealthy or privileged groups,” can produce environments that “negatively affect marginalized communities”.20 This is evident in cities where luxury developments displace affordable housing, deepening social stratification through the built form. In this way, architecture becomes complicit in the maintenance of inequality unless architects actively intervene to challenge these dynamics.

Henri Lefebvre further extends this critique by re-conceptualizing space itself as a social product. In The Production of Space, Lefebvre argues that “(social) space is a (social) product”.21 He contends that space is not a neutral container for social action but rather a terrain produced by and productive of social relations. Architecture, therefore, must be understood not merely as the creation of objects within space, but as a force that shapes, and is shaped by, political and economic structures.

For Lefebvre, the built environment is a site where dominant ideologies materialize. Gated communities, privatized public spaces, and the marginalization of informal settlements all exemplify how architectural decisions reflect broader struggles over control and access. As he

notes, “Every society... produces a space, its own space,” and this space in turn produces social relations.22 The implications for architectural ethics are clear to design is to participate in the reproduction or contestation of these social orders.

Consequently, architecture must be regarded as a vehicle of social transformation. The ethical role of the architect is not merely to solve technical problems or produce aesthetically pleasing structures, but to engage critically with the social consequences of design. Architecture affects how people relate to each other, how communities are formed or fragmented, and how justice is spatialized or denied.

As Colomina and Wigley write, “To design is to think about the future of the human. Not just what we are, but what we could be”.23 This future oriented stance underscores the profound responsibility borne by architects. If space structures life, then the ethics of design must be rooted in a commitment to inclusion, adaptability, and critical reflection.

As Colomina and Wigley write, “To design is to think about the future of the human. Not just what we are, but what we could be”.23 This future oriented stance underscores the profound responsibility borne by architects. If space structures life, then the ethics of design must be rooted in a commitment to inclusion, adaptability, and critical reflection.

"The School of Athens" by Raphael functions as a visual manifesto of Renaissance humanism and a powerful symbol of intellectual inclusivity. The fresco presents an idealized gathering of great thinkers from diverse philosophical traditions— Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Pythagoras, Euclid, and others—engaged in dialogue within a grand architectural space. This harmonious assembly represents an inclusive intellectual community

where differing ideas and schools of thought coexist and interact. The architectural setting, with its soaring arches, classical symmetry, and open spatial arrangement, reflects the Renaissance belief in rational order and the potential of design to foster knowledge and exchange.

While the painting celebrates inclusivity by bringing together minds across time, disciplines, and beliefs, it also implicitly acknowledges exclusion: it is an elite space designed for the intellectual few. Thus, the work highlights a dual truth—that every act of inclusion also defines a boundary of exclusion. Yet, as an allegory, The School of Athens suggests that designed spaces can serve as frameworks for collective thought and cultural advancement, a lesson still vital for architecture today.

Raphael, School of Athens, 1509-1511, fresco (Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican)

Inclusive Design Is a Moral Imperative That Demands Architects Confront Systemic and Economic Barriers

As previously discussed, inclusivity should be placed at the core of architectural ethics. While complete inclusivit across all physical, economic, emotional, and social dimensions may never be fully achievable, it must remain a guiding principle. As a design goal, inclusivity cannot offer a universal theory or a definitive endpoint. Instead, it should function as an evolving process one that adapts and responds to shifting cultural contexts, social needs, and environmental conditions. By anchoring inclusivity at the heart of architectural practice, we shape the “fabric of life” more ethically, responsively, and justly. In doing so, we not only evolve the built environment but also transform human life in return.

Architecture is a distinctly human act, a means of softening the harshness of nature. Unlike natural environments, which operate according to indifference, human-made environments aim to provide comfort, accessibility, and dignity. As a result, the built environment reflects our collective attempt to create a more equitable existence. It is this drive to design spaces that make room for all forms of life that distinguishes human civilization. This distinguishing feature should guide architectural practice, particularly as we confront new ways of living shaped by digital

technology, climate change, and social complexity.

The imperative to design inclusively demands that architects challenge dominant systems political, economic, and spatial. In rapidly expanding capitalist cities, the power structures that shape design outcomes frequently undermine inclusion. If architects fail to contest these forces, the authoritarian and profit-driven systems that dominate urban development will eliminate spaces for the socially, economically, physically, and emotionally marginalized. The future of our cities depends on resisting this erasure. Adaptive inclusivity must, therefore, become central not peripheral to the architectural discipline.

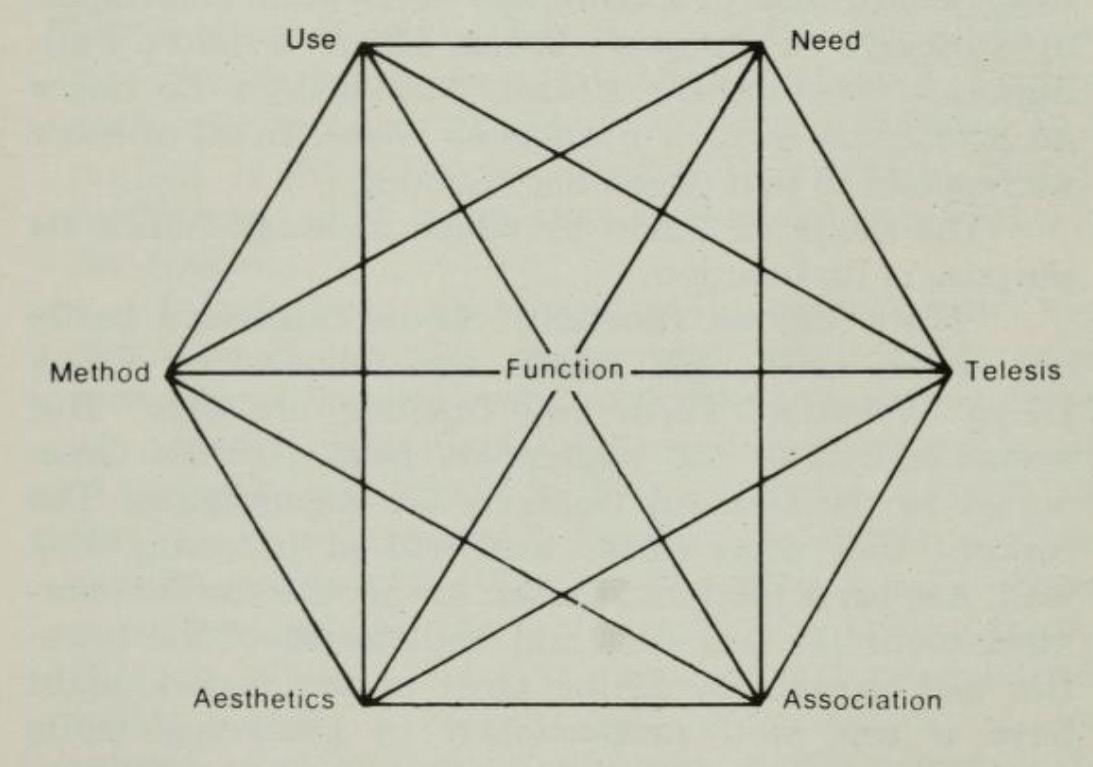

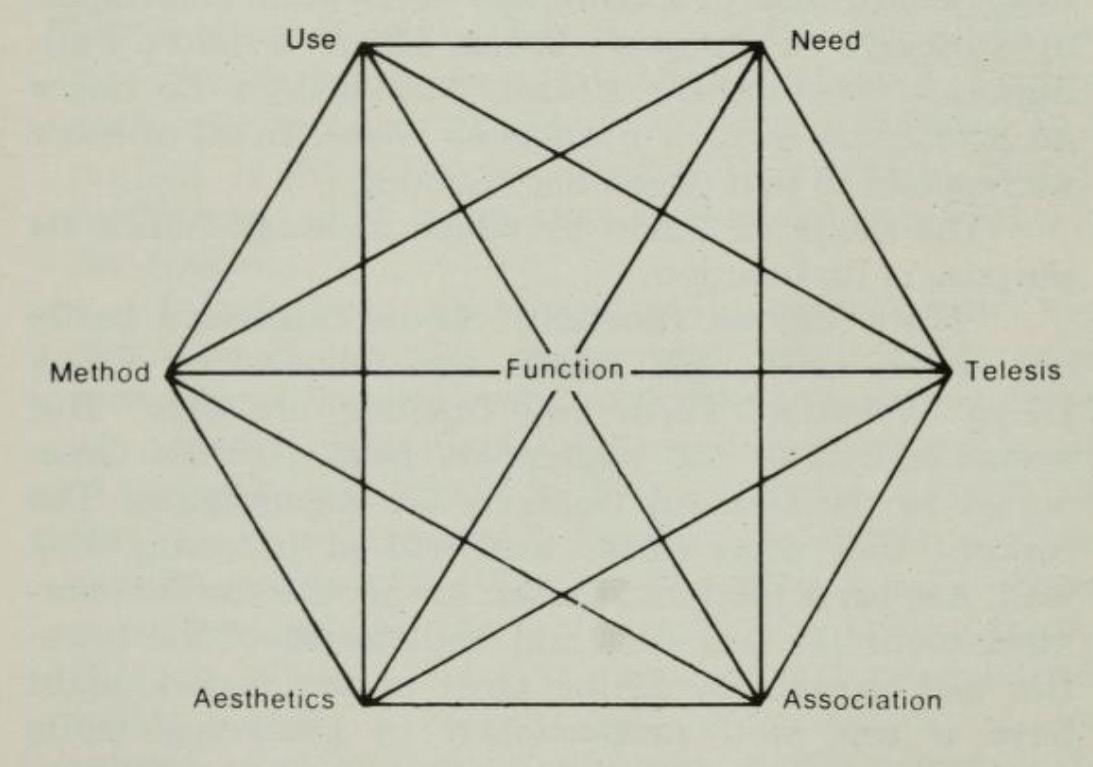

Victor Papanek, in Design for the Real World, insisted that the highest responsibility of designers is to serve the needs of the most vulnerable. “Design,” he writes, “must become an innovative, highly creative, cross-disciplinary tool responsive to the true needs of men”.24 He calls on architects to shift their attention away from the middle and upper classes, focusing instead on designing for low-income communities, elderly people, disabled individuals, and other marginalized groups. His concept of the "Function Complex" emphasizes that ethical design must integrate social function, cultural meaning, aesthetic form, and above all human need.

Papanek’s call for ethical inclusivity frames design not as a neutral craft but as a moral undertaking. A public building without ramps or elevators does not merely fail technically it fails ethically. Inadequate lighting, unsafe layouts, or exclusive zoning policies disproportionately harm vulnerable groups, particularly women, children, and people with disabilities. Design that does not serve all is, in Papanek’s view, “simply bad design”.25

Donald Norman reinforces this ethical imperative in The Design of Everyday Things, where he states that "good design is as little design as possible" and should prioritize usability and accessibility.26 For Norman, intuitive design that naturally accommodates users of diverse physical and cognitive abilities is not a bonus but a baseline requirement. Architecture must provide universal accessibility while also ensuring spatial legibility and emotional inclusiveness. When environments are easy to navigate and welcoming, they foster belonging and inclusion.

Norman’s usability centered approach complements Papanek’s social ethics. Where Papanek argues that inclusive design must prioritize vulnerable users, Norman adds that design should intuitively support and empower all users. Together, they provide a framework where inclusion is not a secondary consideration but the primary goal.

Despite the moral clarity of these arguments, economic systems remain a major obstacle. As Peggy Deamer outlines in Architecture and Capitalism, architecture operates within systems that prioritize capital accumulation over social welfare. She argues that “capitalism’s imperative for profit creates spatial inequities,” leading architects to serve elite clients while neglecting public needs.27 This economic alignment privileges luxury and exclusivity over equity and access.

Gentrification exemplifies this dynamic: luxury developments, marketed as urban “improvements,” often displace low income residents and eliminate affordable housing options. Architects working within such systems face profound ethical tensions between designing for the common good and meeting the demands of capital. Without conscious resistance, design practice risks becoming complicit in structural exclusion.

David Harvey, in The Right to the City, articulates a response to this tension. He asserts that “the right to the city is not merely a right of access to what already exists, but a right to change it after our heart's desire”.28 This right implies a collective power to reshape urban life and social relations. Architects, as spatial agents, must enable this transformation. They must create opportunities for all people regardless of income or identity to participate in the shaping of their environment.

Zoe Mossop echoes this claim in Design for Social Justice, stating that “architects must be more than service providers they must be educators, advocates, and reformers”.29 According to Mossop, inclusive design requires architects to confront systemic inequalities and embed social justice in every phase of their practice. This includes working across political, financial, physical, and emotional dimensions to foster inclusion and equity.

In conclusion, adaptive inclusivity is not simply a design trend or ethical add-on. It is the core of what it means to practice architecture responsibly. Given the social, ecological, and economic challenges of our time, architects must not only respond to existing needs but anticipate future ones. Inclusivity should not aim for perfect universality, but rather for a persistent openness a willingness to listen, evolve, and challenge exclusionary systems. In a world shaped by uneven development and capitalist pressures, the ethical architect must push boundaries, resist complacency, and advocate for a built environment

that honors the full range of human experience.

Conclusion

Architecture functions as an ethical practice which determines human identity and creates social structures and social relationships. The built environment we inhabit together with our formed relationships determine how we interact with our surroundings. Architecture functions as a medium that connects people through their relationships while simultaneously shaping their personal identities according to Colomina and Wigley. Architecture requires more than technical competence because it functions as a cultural and psychological force that affects human existence. Architects need to understand that their design choices create substantial ethical consequences which either sustain or fight against social inequalities.

The principle of inclusive design stands as an absolute necessity for architecture. According to Papanek architects need to make the needs of society's most vulnerable members their top priority. Norman explains that good design should provide intuitive access to everyone regardless of their physical or cognitive limitations. The duty of architects includes designing spaces which welcome all people and promote inclusivity.

The journey toward inclusive design faces multiple barriers which stem from economic and systemic limitations. Architects need to understand how capitalist systems restrict their work because they value financial gain over public welfare. According to Deamer, Harvey and Mossop architects need to challenge existing power structures while advocating for social justice to overcome these barriers. Architects must go beyond designing aesthetically pleasing and functional spaces because their role includes fighting for equitable inclusive environments that promote social justice and accessibility.

Through ethical awareness and inclusive design principles architects can transform their professional work into social change agents who develop spaces that unite beauty with functionality and equality with justice.

Word Court (4092)

Endnotes :

Endnotes :

Primary Sources :

1.Colomina, B. and Wigley, M., 2016. Are We Human? The Design of the Species. Princeton University Press, pp. 1416.

2.Papanek, V., 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Pantheon Books. p. 25

3.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 44

4.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 3

5.Papanek, V., 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Pantheon Books. p. 40

6.Lefebvre, H., 1974. The Production of Space. Blackwell Publishing. p. 10

7.Colomina, B. and Wigley, M., 2016. Are We Human? The Design of the Species. Princeton University Press, p. 16

9.Papanek, V., 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Pantheon Books. p. 25

10.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 3

16.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 16

17.Colomina, B. and Wigley, M., 2016. Are We Human? The Design of the Species. Princeton University Press, p. 15

18.Colomina, B. and Wigley, M., 2016. Are We Human? The Design of the Species. Princeton University Press, p. 19

19.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 5

20.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 7

21.Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. p. 26

22.Lefebvre, H., 1974. The Production of Space. Blackwell Publishing. p. 31

23.Colomina, B. and Wigley, M., 2016. Are We Human? The Design of the Species. Princeton University Press, p. 37

24.Papanek, V., 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Pantheon Books. p. 9

25.Papanek, V., 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Pantheon Books. p. 41

Secondary Sources :

8.Mossop, E., 2016. Design for Social Justice: A Critical Review of Practices in Architecture and Urban Design. Design Issues, 32(4), pp. 9-17.

11.Harvey, D., 2008. The Right to the City. New Left Review, 53, pp. 23-40.

12.Norman, D., 1988. The Design of Everyday Things. Basic Books. p. 4

13.Deamer, P., 2017. Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present. Routledge. p. 56

14.Sennett, R., 2004. The Ethics of the Built Environment. In: Environmental Design: A Study of Architecture and Social Responsibility. Routledge. p. 62

15.Fox, L., 2018. Socially Responsible Architecture: A Call to Action for the Next Generation of Architects. Journal of Social Architecture, pp. 19-24.

26..Norman, D., 1988. The Design of Everyday Things. Basic Books. p. 167

27.Deamer, P., 2017. Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present. Routledge. p. 9

28.Harvey, D., 2008. The Right to the City. New Left Review, 53, p. 23

29.Mossop, E., 2016. Design for Social Justice: A Critical Review of Practices in Architecture and Urban Design. Design Issues, 32(4), p. 52

Bibliography :

Colomina, B. and Wigley, M., 2016. Are We Human? The Design of the Species. Princeton University Press. Papanek, V., 1971. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Pantheon Books. Fox, W., 2000. Ethics and the Built Environment. Routledge. Lefebvre, H., 1974. The Production of Space. Blackwell Publishing. Mossop, E., 2016. Design for Social Justice: A Critical Review of Practices in Architecture and Urban Design. Design Issues.

Harvey, D., 2008. The Right to the City. New Left Review, 53. Norman, D., 1988. The Design of Everyday Things. Basic Books. Deamer, P., 2017. Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present. Routledge.

Sennett, R., 2004. The Ethics of the Built Environment. In: Environmental Design: A Study of Architecture and Social Responsibility. Routledge.