ChArt (Celebrating the Humanities & Arts)

The Humanities Journal of the Phoenix Biomedical Campus

Volume 11, 2025-2026

ChArt (Celebrating the Humanities & Arts)

The Humanities Journal of the Phoenix Biomedical Campus

Volume 11, 2025-2026

The Humanities Journal of the Phoenix Biomedical Campus Volume 11, 2025-2026

©Copyright, All Rights Reserved

Celebrating the Humanities & Arts is an interprofessional, peer-reviewed/juried journal devoted to sharing the insights and experiences of the Phoenix biomedical community (students, staff, faculty and patients) through original works of personal expression, including original art, essays, motion media, photography, poetry and prose.

The journal is supported by: The Program for Narrative Medicine & Health Humanities,, Department of Bioethics and Medical Humanism

The University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix 435 N 5th St. Phoenix, Arizona 85004

Email: PBC-Journal@email.arizona.edu

Website: www.narrativemedphx.com

Print Copy: www.Amazon.com

Dear Phoenix Biomedical Community,

Greetings! We are pleased to present our eleventh annual humanities and arts journal. Our mission is to celebrate the diversity of perspectives, ideas and experiences of our campus with you and present both the familiar and extraordinary moments in human experiences. Representative pieces are drawn from the genres of prose, poetry, photography, painting and motion media. They showcase the many creative and artistic talents of our community.

This print edition is a selection of editor favorites, carefully woven together for your enjoyment. We hope that you feel inspired by the unique perspectives of the authors and artists presented. May these works lead you to a renewed level of commitment to self-expression and artistic exploration, and may your own endeavors create harmony, balance and joy in your life.

On behalf of the editorial board – enjoy!

Jennifer R. Hartmark-Hill, MD, FAAFP

Nicole Varda Faculty Editor-in-Chief Student Editor-in-Chief

Editorial Board

Jen Hartmark-Hill

Kennedy Sparling

Maya Khalil

Nicole Varda

Special Acknowledgements

Dr. Jacqueline Chadwick — With appreciation for support for the founding of this journal

Dr. David Beyda, Department of Bioethics & Medical Humanism Chair — With appreciation for ongoing support, and providing our publication a home

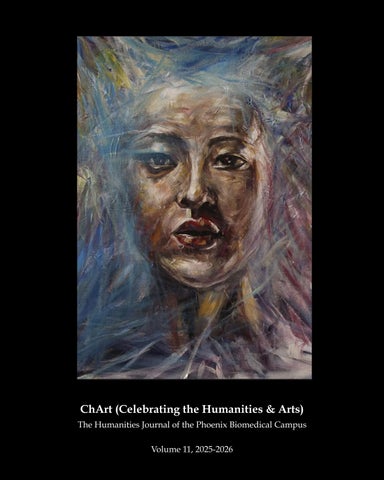

Katrina Jia — Cover Art

This piece explores the balance between life and its inevitable hardships. The girl's face reflects both experience and pain as the blur and haze of life gradually consume her. She embodies the concept of holding onto life's vitality while change, loss, and emotional tolls slowly fade her once strong beliefs and personality. This piece aims to reflect the struggle between strength and fragility that we all face as we navigate life's challenges.

Katrina Jia is a first year medical student with a deep passion for both humanity and art. She uses her art to explore themes of life, vulnerability, and resilience, reflecting on the emotional complexities she has navigated. Outside of her studies and art, she enjoys playing piano, skiing, cooking, baking, and spending time with her kitties!

“My barn having burned down, I can now see the moon.”

Mizuta Masahide

This piece is inspired by the ways in which life changes and we mature, and in the ways in which life changes and we stay the same - still anxious, stumbling through every new experience, and always seeking friendship and familiarity.

Nicole Varda is a fourth-year medical student, interested in primary care with a passion for health humanities, creative writing, and bioethics.

People are not rubber bands.

Apply stress and watch me deform under the strain

Eggshell bones and banana skin are quick to crack and bruise

We are closer to ceramic than polyisoprene

I will live with micro-fractures and crazy glue and a strict avoidance of magnifying glasses

Resiliency is for physicists and polymers and physicians- but only sometimes

Relearning your ABCs, twenty-six this time. A picture book’s spine replaced by radiographic vertebrae but the same needles that made your stomach turn since you were six

Teary-eyed in a patient’s room because she’s only three years younger than you and her hair is freshly braided and her toes are painted the same baby pink as your own, except there’s an organ donor document with her name on it and the only thing you’ve donated are the clothes you cleaned out of your closet two summers ago

Heating up a PB&J for the man in the ED whose granddaughter shares your name and whose hands are cold from heart failure

Calling your mom crying because you read an evaluation that made you feel the same way you did in fourth grade when a girl made fun of your new shoes

Falling asleep in mascara and only remembering a multivitamin once a week

Exhausted because you had to read an extra chapter on the importance of sleep hygiene

Christmas trees left up until January and abandoned laundry taking up permanent residence on that one couch cushion you’ve given up on

Your baby teeth falling out and your wisdom teeth being extracted

Did I do good?

Bumping the hospital bed, shaky hands, misguiding the laparoscopic camera

Suddenly you’re learning to drive all over again and you’re doing it all wrong

Getting lost, asking for permission to go the bathroom, being unsure where to sit at lunch

Holding a hand when yours are too inexperienced to do anything else

Buying your seventh potted plant, letting false optimism take root that this one will be different

Those are things for people.

The meaning of this piece refers to the unpredictability of life and medicine, even in the face of best practices and preparation. A personal moment of where I felt disappointed with my own academic shortcomings was followed by a moving clinical experience that demonstrated a way where Life imitates Medicine, in this case, it was despite the patient's efforts and prophylactic measures. The title refers to a moment years ago when I scratched out my premedical commitment on a calendar, and realizing then that it would have been best to write in pencil.

Fatemah Alzuhairi is a UACOMP med student from the class of 2028. She graduated from ASU in 2022 with a degree in biomedical sciences and a minor in history. In her spare time, she enjoys planning creative projects, reading, and drinking copious amounts of Earl Grey tea.

In the spirit of reinvention, I tried again to be a better student.

I try. The work spread and invaded my calendar with no consideration for morale.

All for the hope of my redemption. And yet, I fell short, and so, I licked my wounds, and I professed my confusion:

“I thought I did everything right.”

I continued on, relatively unscathed, begrudging that this was all too familiar.

Familiar it was, the question followed into clinic, joining the last patient of the day.

Nothing good comes from the dread that comes with the anticipation,

Their questions reinvent themselves, one gets creative when made to wait.

With no clocks in the room, the internal chronometer gets skewed, and this patient waits.

She tried to hold her head up high, giving a smile as she wrung out her hands.

Her eyes darting between us, her joke lands with a broken leg.

It is spring, I thought, far too early for Octobers. It was then she clued me in. A double amputation:

—Her double mastectomy. There again I hear it—

“I thought I did everything right.”

She now grapples with what is only speculation. What's worse than bad news?

Ambiguous bad news.

She ask the questions and comes with hypotheses, Calling on the scientific method that falls short against the shrugs of physicians.

(Would my shoulders shrug that way one day?)

So beloved are those who take preventative measures,

Permanent and deeper than the skin, offer a sacrifice, ’it will all be worth it...’

Much more lasting than exam scores and the current flavor of grievances.

Its many echoes are all too common. In one’s work, in the day-to-day, in the necessary.

The fruit of our labor may still rot.

It is why I write on my lofty calendars in pencil— And not pen. Pandemics do not care for hefty deadlines.

Metastases have no sense of propriety, And all that preparation may still leave you limping past the finish line.

We all can try our best, but it may only go so far, But here is hoping our best may be good enough.

Brace is about the quiet, often invisible process of healing. I wrote it while going through an injury, when everything felt slow and uncertain. It captures the frustration of waiting and the strength it takes to keep going when you can’t see progress. Sometimes healing isn’t loud or clear—it happens slowly, beneath the surface. This poem is a reminder that even in stillness, we’re getting stronger.

Neha Patel is a Junior at Paradise Valley High School. She is a part of the CREST Bioscience program where she is actively exploring various career paths in medicine. Beyond academics, Neha is an avid athlete, proudly representing her school as a Captain of both the Varsity Basketball and Varsity Flag Football teams. Sports have been a cornerstone of her life, teaching her the values of teamwork, discipline, and perseverance. She is passionate about combining her love for science and athletics as she prepares for a future in healthcare.

Paused, not brokenAn internal fight, Still not woken, When will I see the light?

Days, weeks, months How long do I have to wait?

Life’s medicine moves fast, No time to hesitate.

Healing isn’t always seen, It grows in quiet, steady streamsA whispered strength beneath the skin, Turning pain to power within.

This piece was inspired by my dad and my two grandfathers. I see how over time they change and at the beginning stages of life they take care of you, but in later stages when they are not as healthy or strong, you tend to take care of them.

Neela Patel is a 12-year-old going into 8th grade. She loves writing poetry. Neela also loves sports and has been playing basketball for about 4 years. She gives back to the community by participating in Girl Scouts and serves as a Student Ambassador for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

There once was a man And I didn't know who he was He held me and swaddled me, Fed me and read to me.

There once was a man He held my bike for me when I was learning to ride it And taught me how to throw a ball.

There once was a man Who drove me to school And taught me to read and write. There once was a man Who took me camping in my backyard And even brought me back into the house when it was too cold.

There once was a man Who cheered the loudest when I graduated And took me places in the summer. There once was a man Who loved me and watched me love another.

There once was a man Who walked me down the aisle. Now, times have changed And I am the one holding you, feeding you, And reading to you.

I am the one holding your hand and your cane. I am the one driving you to your appointments And reading your prescriptions And writing your daily schedule.

I am the one who brings you your coat And I am the one who lays a blanket on you when you fall asleep in the chair.

In the end, We have come full circle You are my father And I am your daughter.

This piece is part of a poetry collection that reimagines core concepts in bioinformatics through a humanistic lens. As a Biomedical Informatics student, I often grapple with the complexity and abstraction of scientific ideas—sequence alignment, comparative genomics, and phylogenetics can feel distant to those outside the field. Through poetry, I aim to bridge that gap.

Each poem in this piece transforms a technical method into a metaphor for understanding life, identity, and connection. “Sequence Alignment” reflects our search for meaning in genetic differences that can change a life.

“Comparative Genomics” explores how the smallest genetic variations distinguish us from other species—and make us uniquely human.

“Phylogenetics” invites us to consider our place on the evolutionary tree, grounded in the past and reaching toward the future.

My inspiration stems from the beauty of the natural world and the transformative power of science. I believe science is not just about discovery, but about storytelling—about making the invisible visible and the complex understandable. Poetry, with its emotional resonance, allows me to share that vision with others and celebrate the deep creativity embedded in scientific inquiry.

Sanyam Paresh Shah is a senior majoring in Biomedical Informatics at Arizona State University. Passionate about the intersection of biology, mathematics, and technology, he has explored systems biology, metagenomics, and machine learning. As a research assistant in two labs, he contributes to metagenomic analysis related to air and dust sampling and helps develop a healthcare decision aid. He has also served as a teaching assistant for Biostatistics and Python, strengthening his communication and teaching skills. His capstone project focuses on algorithms to support healthcare recommendations. Outside research, Sanyam blends art and science through poetry inspired by bioinformatics, aiming to make complex topics more accessible. Committed to advancing genomics and human health, he aspires to pursue a PhD and contribute impactful discoveries in the field.

The study of evolutionary relationships between species using sequencing of genetic material.

Humans are like leaves on a tree— not knowing the branches or the roots through which we ascend. When the wind blows, we separate from life so easily, so peacefully.

When the sun rises, the leaves grow. They look up and see the future. They are unaware of the grip of the past that holds them in place.

The leaves shine and the roots rest in the darkness. When the sun shines, the rays escape. They light up the path as we dig for the roots.

A field that compares the full genomes of multiple species.

We lay genomes side by side, compare the ancient texts of our existence, diluted and perfected by time.

I observe similarities in the DNA of the mouse— genes that make our hearts beat, eyes blink, lungs breathe.

The secrets lie in the one-percent, the genetic difference that allows me to write poetry, worry about my grandma’s health and make her tea.

I am amazed when I see a sequence that tells the story of a billion years, providing clues to the first cell that made us.

I am hopeful that one day, a difference will show itself, perhaps in a bat’s code, explaining the absence of cancer, a pattern that shields us from pain.

Sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA or protein to identify regions of similarity or differences.

We align the sequences of life, hoping to fill in the gaps that define our history and identity.

We look for patterns in caves of information. We look for differences— a mutation that separates life from death, cancer from no cancer, joy from misery— so that someday, when someone’s sister cries in a hospital room, I can point to a sequence and say Here, here’s the spot where we'll make it right.

Pottery became a newfound passion during my gap year. But over this past year, I’ve struggled to juggle my creative interests with the demands of medical school. Initially setting pottery aside, I found myself increasingly prone to episodes of burnout. But creating this piece was a call back to my love for pottery and unexpectedly, medicine.

I draw many parallels between pottery and medicine. Both are labors of love and time. Working with clay also offers a valuable perspective on how I strive to interact with patients—with attentiveness, care and compassion.

Most of all, pottery teaches me resilience. I wanted to reflect that in this piece, initially cracked then repaired through kintsugi, a traditional Japanese ceramic practice that involves mending broken pottery with lacquer and powdered gold. This practice embraces imperfections as marks of beauty in the process of healing and growth—an idea that deeply resonated with me as I reflected on my first year in medical school. Ultimately, I wanted this piece to exhibit the beauty in its resilience as a reminder of the resilience we cultivate as physicians in training, and the beauty in learning to heal.

Irene Jo is a second-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix. Growing up with an artist mom, she developed an ambition to create art like hers but quickly realized she did not share her mom’s gift for painting. Nonetheless, she pursued her creativity through other mediums—from constantly rearranging her 10’ by 10’ room with DIY projects as a kid to finding a love of ceramics as an adult. She especially values art as a way to connect with and give to others.

This piece was inspired by the often invisible and persistent struggle experienced by individuals living with addiction, trauma, or other mental health challenges.

Kennedy Sparling, a fourth-year medical student, has always been drawn to the creative arts, finding a powerful outlet for self-expression through poetry. Writing allows her to give voice to feelings and thoughts that are often difficult to articulate, serving as both a personal refuge and a means of connection with others. This deep appreciation for creative expression continues to inform her approach to both medicine and life.

In medicine, they talk about compensated failure, how the body adapts, makes do, strives for return, until it no longer can. I have seen it, a man with hands like matchsticks, not reaching for a drug, but for silence, for rest, for the fleeting feeling of not being hunted by his own blood. I have felt it, the quiet chaos beneath my skin. On the outside, passing as whole, never revealing, the many buried versions of myself it took to get here. And no one applauds the strength it takes to continue, not because it’s not noble, but because it’s necessary.

To rebuild without guidance. To breathe without sound.

And no one warns you of the never ending fight, becoming familiar with the masked struggle of who you were, who you are now.

Always distracting, endlessly adjusting, praying that day you no longer adapt never comes.

"Life in Play" uses basketball as a metaphor for life’s journey—full of choices, setbacks, and resilience. Each quarter represents a new chapter, and the “ball in your court” reflects the power we have to shape our path. Some shots land, some miss, but the game goes on. Inspired by my experience as a student-athlete, this piece captures how sports have taught me to face challenges, stay steady, and keep moving forward—on and off the court.

Neha Patel is a Junior at Paradise Valley High School. She is a part of the CREST Bioscience program where she is actively exploring various career paths in medicine. Beyond academics, Neha is an avid athlete, proudly representing her school as a Captain of both the Varsity Basketball and Varsity Flag Football teams. Sports have been a cornerstone of her life, teaching her the values of teamwork, discipline, and perseverance. She is passionate about combining her love for science and athletics as she prepares for a future in healthcare.

Tipoff and birth, Just beginnings, A 40 minute clock, Four quarters of life.

The ball is always in your court, Only you can decide the next play, Some shots fall, And some drift away.

Sometimes the outcomes are uncontrollable, But the game must go on, Stay steady, stay strong, And keep moving along.

I have a long list of health issues. Among the most overwhelming has been my severe chronic asthma with COPD. I was born with a birth defect called spina bifida which requires its own specific focus and strength to deal with. But when we discovered the extra complications that came with my breathing issues several years into the rest of my struggles, it created a whole new level of concern for the people who helped take care of me as I grew up, especially my mother. This is a narrative poem about one of my many nights my mother and I were forced to confront my ailments head-on.

Bryan Hall has a B.A. in Communication from Arizona State University. He has been a contributing member of his local writing community since 2005 in such roles as assistant editor for the poetry journal Merge, co-host of First Friday Poetry in Heritage Square, member of the Arizona State Poetry Society and co-facilitator of various writing workshops for The Phoenix Poetry Series as well as Mesa Arts Center. His chapbooks are Walks on Wheels with Ione Press and Corners of Everywhere with Lulu Press Inc. Bryan also published a micro-poem collection called The Master of Collapse with Rinky-Dink Press in 2021.

(for my mother)

Urgent Care had become routine –faceless lab coats aping composure after a barrage of needles filled me with corticosteroids. Then scrutiny of sinus rhythms and an escalating medical history chart turns the room to furrowed brows and anxious whispers while waiting for my lungs to stabilize.

With every precaution taken and no stone left to turn they reluctantly allowed us to leave. It was after dark and well past my bedtime but I was invigorated, twitching and talkative in the backseat from the medicine. You were silently mulling over the evening’s events. We were still learning the hard way: even here the air is too thin for me.

But this is how we’ve always lived –more fragile, though somehow stronger for it.

It may have been fear that drove your car to Smitty’s on the way home, or perhaps some measure of pride in the way I used to face things directly, without panic or fatigue –still too young to recognize ineptitude, not yet dulled from limitation.

Knowing full-well life scarcely rewards tenacity, you bought me a G.I. Joe action figure I had been frantically seeking and told me it was for being a good patient. Then, after tucking me in, you pushed back against this fickle universe – refusing to ever concede that I might not get to stay.

This piece is about how life can be brutal and painful. It demonstrates that throughout the tough times in life, you have to keep fighting and have hope in yourself and everyone else around you.

Neela Patel is a 12-year-old going into 8th grade. She loves writing poetry. Neela also loves sports and has been playing basketball for about 4 years. She gives back to the community by participating in Girl Scouts and serves as a Student Ambassador for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Winter is lifeless

Everything is dead, but us

We are still alive

Fighting to survive

Now we understand what it is like to live in this brutal season

We have reason to try to stay alive

There are people who love us and care for us

We must try

You can’t cry

You must be tough during this brutal season tonight

Cause we are the last alive, even though we got tears in our eyes

Nothing we can do but try to fight

Like it is the last night

Shivering in the pain, with no hope left in me

But we must try

Cause if you don't try, there is no fight against this brutal season tonight

This piece encapsulates my feelings after three clinical rotations in medical school. Broadly, it reflects the many high and lows we feel in life. The long tense periods where we feel like the the days are blending together and the slow relaxing days that we desperately cling on to. It highlights the isolation that students can feel now that they are away from campus and classmates. It reinforces the importance that community can bring and the warmth you get from familiar faces.

Mike Shide Zhang is a third-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine Phoenix. He first started his love of poetry when his wonderful high school English teacher encouraged his passion. He finds poetry a restful escape from the world.

Whisked from place to place

Confused and disoriented

Nomad in the blizzard

Trying to find some warmth

Climbing towards an unseeable summit

One I’ve heard in whispers

Trying to trust the journey

But still taking many wrong turns

Holding on to those precious moments of peace

Sleeping while I can, eating if I can

Tiredness seeps like the cold

Through my suddenly less shiny short white coat

I’ve been up for almost a day but I can’t manage to close my eyes

Even when I do I wake up

To the same heaviness

I forgot when I was last happy

When I got to be safe to be myself

All alone I kept wandering

Thinking about all the people who started with me

Now dropped into their own storm

Only the lofty spirits witness me

Blending in with their long white coats

Silently judging me for all my missteps trying to survive another month

What should you do if you can’t go on any longer?

A dizzying array of fast and slow

Just like that I’m back in the great lodge

Seeing everyone I started out with

Made strong by being battered and bruised

I get one week to prepare before I get sent out again

Trying my hardest to let the weariness drain out of me

Soak in the warmth and pull myself together

Hitting the books and the ancestral archives

Prying out secret knowledge to save myself

Before I get a chance to say goodbye

I am pushed out to the cold again

To go on to my fourth rotation

Microaggressions start harmlessly and in ways that invalidate what we experience. I hope to give gentle insight in the often excused conduct that starts young and continues with the ultimate goal of keeping only one narrative dominant.

Dr. Jean Robey is a nephrologist who practices Narrative Medicine, writer, and poet. Her book Evesonderism: Living the Story of the Art of Medicine comes out September 2025

The firecrackers going off

All around us

And the bright colorful twinkled and showered down and faded

The wind blew a light breeze and the night air was filled with Fireflies

I felt young

And my daughter said, “I love the wind.”

Her father leaned in and patted her head saying back, “I know you do. It is mighty and sweet.”

The man beside her said, “You don’t know wind.” Gruff and cruel were the words that divided her from her truth

She looked at her father for reassurance but he hadn’t heard the man for the fireworks going off

Her toes began to be the only thing she’d stare at

It didn’t sit right

The night blew smoke and smelled of fire Inviting burning down a notion

To burn it hot and final

“I’m cold,” she said “You’re not,” her father said, chuckling I saw all the excuses and reasons why he meant well laid out like a harmless picnic

On the blanket of a social contract It didn’t sit right

And then I took her by the arm and spun her around for her to see

My eyes

My understanding of 99 degrees and humidity “Delilah, you be what you are. Not Sweetpea or Honey. You be cold. You be in love with a breeze. You don’t need big folks, men, women or me to tell you,” I said, “who you are.”

And the largest firework exploded to put that in her head instead of the nonsense

That she can’t tell if she’s cold or loves the wind

What a crime to rob a genuine narrative Steal voice choice, identity, and truth

Just to stay the eye we be mindful to look away from For toes instead of what we know in our hearts

Conscious, subconscious and superconscious experiences integrate into our practice of medicine, and the path to healing our own wounds and the wounds of our patients may surprise us.

Kenna Stephenson, a native Texan, thrives on helping others achieve well-being. She has cared for over 100,000 patients in settings of: a Marae in New Zealand, under triple canopy jungles of Guatemala, inside a mobile unit traversing Texas mine fields, and a Paramount Pictures’ set. A graduate of The University of Texas at Austin, she achieved the MD degree at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and completed a student fellowship at the National Institutes of Health. Her residency at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center culminated with the Resident’s Resident Award. She has practiced in Texas, Arizona, Central America, Southeast Asia, and New Zealand including private practice and academic medicine. An Associate Professor of Family, Community & Preventive Medicine, she is the Founding Medical Director of Team-5 Medical Foundation. Her book, The Gospel of Women’s Health: Awakening Athena Again has received international acclaim.

Beep, beep, beep! She startles glancing at her pager. What was it in the dream that so disturbed her? She wondered silently, aware that she had had a powerful dream, but no time to recall it. Throughout rounds, it came back to her in pieces. Walking to her office, she reconstructed it completely. It embarrassed her-how ridiculous! During the morning clinic the dream haunted her creeping into her psyche between patient cases. She met her husband for lunch. He always knew when she was troubled.

“What’s up?” he asks, with genuine concern.

“Nothing,” she responds.

He sighs, used to being shrugged off by such inquiries. Walking to the office, he tries again, sensing her restlessness.

“OK,” she reluctantly agreed. “I had this dream-it’s ridiculous, even embarrassing. I can’t shake it-it’s stayed with me all day.”

She began. “The dream is in Spanish, and we walk through an entrance to a large, indoor swimming pool. At first it appears deserted, then we hear voices, and see three Viejas dressed in black and wailing in the corner. You step back and I approach them.”

“She’s dying,” they cry, “she’s dying-can you help?”

“They gesture to the pool. I step to the tiled edge and see a girl lying face up on the bottom of the pool. Her eyes are open and her body completely still. Her hair sweeps around her head like a halo.

I dive into the water, feel her pulse, then surface for air, and call for you to bring a dolphin. At that moment, I strongly believe that the only way to resuscitate her is with a dolphin. Isn’t that crazy? I know CPR and make no effort to initiate it.”

“What happened next?” her husband asks with increasing interest.

“I calmly wait, and you return carrying a dolphin. I observe numerous scars on its body and am concerned that it might be too frail to be effective as you lower it into the pool. The dolphin swims straight to me, and we dive down together and resuscitate the girl. How? I don’t know. We bring her up and out of the pool and she is breathing. The women are joyful at her recovery. Then I woke up. It’s just humiliating, that I used a dolphin-crazy!” she finished.

Rounds run late that evening due to an office emergency and an ICU crisis. As she finishes her charts in the ICU, she greets the chaplain who is also completing rounds. She feels the urge to talk to her about the dream-feeling that perhaps she could help. Although she doesn’t know Chaplain Terry well, she recognizes her wisdom in their mutual patient care, and feels she is trustworthy. After sharing the dream, the chaplain responds.

“Dreams are symbolic, not literal, so don’t judge yourself so harshly about your medical skills. Dreams may convey messages from the subconscious mind. Did you grow up near the sea?”

“No, not at all,” she answered firmly, not wanting to unseal the door to her childhood and somewhat dismayed that Chaplain Terry has embarked on this path to the past. She avoids any discussions about her life prior to her university entrance as most people are incredulous, others envious of her accomplishments after a tough start and some express pity which annoys her. She realized early in her training that few could grasp her experience nor should they-it was hers and private, and as a cultural minority among the medical community it was best to keep silent about her past.

“Dreams involving a body of water represent your spiritual self, and theological symbols have depicted the dolphin as the Christ of the ocean- its perpetual smile of serenity and peace conveys compassion, and its willingness to go into dangerous waters to assist creatures including humans is told in legends. In some images, the dolphin is impaled on an anchor like a crucifix. Although you didn’t grow up near the ocean, have you even interacted with a dolphin?” she persisted.

“No, I really don’t think so,” the doctor responds, yet this simple question penetrates her psyche- piercing her armor, her mask. She hurriedly thanks the chaplain and retreats to her private office as the world that she had escaped, and buried, is erupting. First the smell- dust, oil, cotton seed.

Next the taste-sand, salt and blood until finally the feeling-the feeling that she had worked so hard to escape slithers through her body, uncomfortably clutching, then squeezing her chest and paralyzing her limbs. The memory emerges. As the woman and child exit the department store and head to the car, they narrow their eyes and cover their noses and mouths to guard against the sandy grit whipping through the air. The lot holds a few scattered cars underneath a dirt-filled sky and the parking lot speakers wail with the voice of Waylon Jennings, a native son. The girl likes Waylon’s voice-it is how she feels-light and heavy together. Looking for brightness in the world and feeling its pain. Suddenly a glint catches her attention, and she widens her eyes to track the brightness. The sun has broken through the dull dishwater sky, and its light reflects from on the surface of a small pool at the edge of the parking lot. Water! Water was an enchantment in this dust bowl which was devoid of lakes, rivers, and streams. The only standing bodies of water that the girl had seen were irrigation ditches which occasionally swelled with spring rains. Why is there a pool in the parking lot of the Sears and Roebuck department store? She strains to see more, and notices a truck parked nearby and a sign: Dolphin. Dare she ask to go closer? No, she counters, as her requests are almost always denied, or when pursued, frequently punished as being vain.

Yet, her chest grows full of desire, and she feels that it will break or that she will suffocate-she urgently needs to see the dolphin no matter the consequences-it is necessary to her very existence and breathing.

“Please, please can I see the dolphin?” she begs the woman. The woman surprisingly acknowledges her request and ambivalently turns towards the pool. As they get closer, the girl notices a smaller sign: See the Dolphin 25 cents. Although the six-year-old has no money, in fact nothing to call her own, she continues walking towards the pool. She stops near a man squatting on the pavement between the pool and truck, trying to light a cigarette between gusts of wind. Eagerly she cranes her neck, straining to see the pool. She soon realizes that she isn’t tall enough to see the surface from the ground. The sky darkens and the sun seems covered with more dirt as the wind spits more sand into their faces. She doesn’t dare ask for 25 cents, knowing it would be denied. She stands still, straining to hear the dolphin splashing in the pool above the howl of the wind. Lost in her thoughts, she startles when the man pulls down a ladder and his gentle voice commands, “Climb up.” Dreamily she obeys. Standing at the level of the pool’s surface, she watches the man dart to the opposite side of the pool with a metal bucket. She strains to see the dolphin amidst the brown water’s choppy waves kicked up by the sharp West Texas wind.

She looks harder imagining a dolphin fin with each foam crest. Whee! A whistle sounds as the man holds a fish above the surface, and the dolphin jumps up to snare the prize then quickly disappears. Whee! The whistle chirps again, and the dolphin returns to the surface swimming on its belly, then flipping to its back.

“Touch it” the man commands, and the girl extends her hand to stroke the dolphin’s belly. With that touch a feeling courses through her body, a sense of being alive, being free, and being clean. She feels as if she belongs to a grander world and place filled with comfort and warmth. This strange feeling engulfs her as she yields to its embrace when she is startled at a familiar sound.

“Come down, we have to go,” the voice orders, and the girl returns to the ground. Looking back every few steps, she watches the pool as they approach the car and continues looking back as they drive through the parking lot, down the street, and then as long as she can, she keeps looking back at the Sears and Roebucks sign. When she can no longer see the sign, she begins recreating the experience in her imagination wanting to find that feeling again. Whack! The girl startles, then is aware of the hot, stinging sensation on her cheek.

“Look at ME when I’m talking to you! You are ungrateful, insolent-a devil’s child.” The voice seems far away, yet with more blows she hears its insults more clearly. Whack! She narrows her eyes, turns toward the voice as commanded, and lets the beating begin.

I thought of renewal while creating this piece, "Reform our Fears". I believe that wellness captivates one’s pursuits and transformative experiences redirect us to reform our fears.

Insulin injections can be intimidating for some. They will sting, but they are reassuring for blood sugar control.

In the picture, the insulin pens were arranged collectively to form a casing that would serve as extra support for the vase, like administering another form of treatment to lower the blood sugar levels.

As proper diet and regular exercise remain the foundation of treatment in diabetes, the picture shows that the needle caps were coalesced in the form of a rectangular apple server.

For any form of treatment, active involvement and compliance are necessary for effectiveness. In the picture, the orchid plant’s graceful stance signifies calm compliance and growth.

Just like in the picture, at times, life may be on the edge, and balancing things is important to capture the moment.

Dr. Joan Frances C. Chua is a Board-Certified Internist, currently a Part-Time Faculty at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix, Doctoring Program, as a Clinical Skills Evaluator, and holds a Clinical Assistant Professor title in Internal Medicine. She completed her Internal Medicine Residency Program at St. Francis Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her Rotating Internship was completed at Santo Tomas University Hospital in Manila, Philippines. She earned her degree in Doctor of Medicine and Surgery at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, Philippines. She completed her undergraduate degree in Bachelor of Science Major in Biology - Accelerated 3-year Program at the University of Santo Tomas as well.

“Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other’s eye for an instant?”

Henry David Thoreau

I work as a poetic interventionist/poetic medicine specialist, and though I work with a range of medically vulnerable populations, these poems are based on observations/reflections of my work with dementia patients. As a full-time caregiver to my adult son (who has multiple disabilities and congenital conditions), I have a special bond with family caregivers, but I also empathize with people who are struggling with their newly diagnosed/evolving neurodivergence. I’m not an MD, so they’re not “my patients” in the clinical sense of the phrase, but they are “my people,” and bringing language, creativity, playfulness, and joy to them is one of the greatest gifts of my life. I hope these poems convey both my gratitude and love for them (and my son).

Rosemarie Dombrowski is the inaugural Poet Laureate of Phoenix, AZ, the founding editor of rinky dink press, and the founding director of Revisionary Arts, a nonprofit that facilitates self-care and healing through poetry. She’s published four collections of poetry and is the recipient of an Arts Hero Award, a Great 48 award, a Laureate Fellowship from the Academy of American Poets, an Arizona Humanities Speaker of the Year award, and an Arizona Capital Times Leader of the Year award. RD teaches at Arizona State University and is the faculty editor of both ISSUED: stories of service and Grey Matter, the medical poetry journal at the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix. Her work has been featured on poets.org, NPR, TEDx, and elsewhere.

At the clinic, Beth talks about him as though she invented the details: the lushness of its nonverbal dialogue, movements like slanted rhyme. She insists that he can speak, or that he’s spoken to her, and you can almost hear him humming over the lunchtime soundtrack. You run your fingers through each other’s hair, braid another version of the story together, and you are both happy and sad, and you never correct her.

You pass around a box of crocheted hearts. The patients swoon as they reach for purples and baby blues, hold them like heirlooms.

In Plath’s poem, “Two Views of a Cadaver Room,” the medical student scalpels the heart right out of the cadaver and hands it to her like a love letter without words, which, in a way, is the most sacred kind.

This story has stayed with me. I thought I was in Rocky Point to serve, but this patient ended up changing me. Even though we couldn’t offer her the surgery she needed, her strength, love for her family, and quiet smile left a deep impression. It was one of those moments that made everything real. She gave me something I’ll carry with me through medical school.

J Bryce Palmer is a first-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. Originally from Snowflake, Arizona, he is passionate about narrative medicine and the power of patient stories to inspire compassionate, meaningful care.

Sitting in the heat of the Mexican desert, I took your chart from a colleague heading to lunch. I was eager to help, grateful for the chance to serve in a volunteer clinic.

I called your name and watched you stand up slowly, hobbling with the clinic’s walker. Each step was a labor of pain as we moved toward the exam room; even sitting took great effort. My enthusiasm quickly turned to concern.

As we spoke through a translator, the severity of your condition began to unfold. You told a story of years filled with pain, cramping, and weakness. It was worse when you leaned back and eased slightly when you leaned forward. You were suffering, enduring, and trying to adapt.

On the exam table, your body continued the story: you couldn’t kick out, dorsiflex, or feel parts of your foot. A positive straight leg test. Then there were the X-rays you handed me. Physical films you kept for moments like these. A failed L4-L5 fusion with listhesis. Surgery is what you really need. But we didn’t have the resources here.

You began to cry. I waited for the translation, but I didn’t need words to understand. Your husband, always nearby, kind and attentive, tried to comfort you. You spoke of the 12-year-old grandson at home. You wanted to cook and care for your husband and the child. But you couldn’t care for even yourself.

When it was time to go, we helped you to the dusty car shuffling, because the clinic’s walker had to stay behind. And yet, as you climbed inside and drove away, you smiled. I felt overwhelmed, hopeless, and deeply moved.

In that moment, you gave me a gift- a single fragment of your story. Your example stirred something within me. Inspiration. You inspired me, a first-year medical student, to pursue a path where I could do more for patients like you. I had come to serve, but you gave me something far greater: a vision of your potential, the life you could pursue. That Saturday, sweating in the Mexican sun, I couldn’t help you. Someday, though, I’ll be back. I might not be in Mexico, and it might not be you in the room, but I’ll be back, ready to give you your life back.

My first rotation of third year was neurology. Because it was my first clinical experience with nothing else to compare it to, I'm not sure I fully realized in the moment how emotionally weighty some of the situations were-- I continued to process them as the year unfolded. Evaluating patients for brain death is something I will never forget. A particular patient we rounded on for a week was the inspiration for this piece. I am deeply grateful for the time I got to spend with him. Here I tried to reflect on the contradictory perceptions and feelings I experienced. I hoped to express the mixture of a surreal tragedy and the reassuring way recognition of humanity is extended toward the patient by care teams during this process.

Annalise Bracher is a 4th year medical student pursuing Child Neurology and a member of the Health Humanities COD. She particularly enjoys writing short stories and flash fiction. In her free time, she loves to read and watch all things sci-fi, play the violin, and cook new recipes with friends and family.

Despite being less than a day old, your reminder was ghostly.

Printed neatly on the whiteboard in sleek ink, bubbled handwriting and an exclamation point. The nurse who had written it intended for you to read it upon awakening. You were imagined leaving with your groceries in hand, saved from rot, your fridge full for the coming week. You were meant to feel the warmth and relief one does when you’ve been cared for so closely.

They moved through each test with diligence. Each day the same. I felt the unease of performance to an unknown audience when I spoke to you and as I watched my hands move across your face, awkwardly— somehow feeling both too gentle and too brazen at the same moment. What sort of limbo were we in together? As we waited for the final sign of your inevitable state of displacement? I sound cold to describe you like this—I feel shame to view you as an unavoidable ending. Did you sense these vestiges of companionship and relation we offered to you as you left yourself behind?

In the final hours, did you know your groceries would not spoil?

Kennedy Sparling, a fourth-year medical student, has always been drawn to the creative arts, finding a powerful outlet for self-expression through poetry. Writing allows her to give voice to feelings and thoughts that are often difficult to articulate, serving as both a personal refuge and a means of connection with others. This deep appreciation for creative expression continues to inform her approach to both medicine and life.

I know her face, her name.

A ghost, my own reflection. Familiar enough to recognize, but too distant to call from memory.

I imagine her laughter, tears, sounds echoing in the loudness of his unspoken. I wonder if she hears me too, feels the same shape of longing, sees the same cracks in her reflection.

She is real and not real.

walking a path parallel to mine, asymptotes drawing close but never touching, forbidden to collide, bound by a geometry no one taught us.

Blood is thick, they say, but I’ve watched it thin into mist, Particles drifting, recasting themselves into smoke, present but untouchable, slipping through fingers desperate to hold.

But still, she’s there. Not buried in my memories, Nor the stories of my childhood, but present, quiet, sealed in the space between.

I know what I feel has no permission. No label, only the stifled ache of “I wish I knew you” tucked softly between “I know I never can.”

This vase came from a need to get thoughts out of my head in a way that words couldn’t express. There was something calming and grounding about carving images and designs through the black slip — each line helping me work through something I couldn’t quite name. The design wasn’t planned; it just flowed as I went.

The patterns and symbols were inspired by rough images of nature. I wasn’t trying to make something polished or pristine. I just wanted to make something that felt real. The eyes, the organic shapes, and the strange little details are all parts of whatever was sitting in my mind at the time.

This piece gave me space to let those things out. It’s not meant to be over thought — just something to sit with, and maybe feel a bit of that quiet release too.

Santana Solomon was raised in rural Arizona and is currently a medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix. She likes to make ceramics.

Kenna Stephenson, a native Texan, thrives on helping others achieve well-being. She has cared for over 100,000 patients in settings of: a Marae in New Zealand, under triple canopy jungles of Guatemala, inside a mobile unit traversing Texas mine fields, and a Paramount Pictures’ set. A graduate of The University of Texas at Austin, she achieved the MD degree at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and completed a student fellowship at the National Institutes of Health. Her residency at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center culminated with the Resident’s Resident Award. She has practiced in Texas, Arizona, Central America, Southeast Asia, and New Zealand including private practice and academic medicine. An Associate Professor of Family, Community & Preventive Medicine, she is the Founding Medical Director of Team-5 Medical Foundation. Her book, The Gospel of Women’s Health: Awakening Athena Again has received international acclaim.

Dear Cynthia,

Happy Birthday, and for your gift please accept this story about your sons. As you may remember, I was hospitalised and met Kyle when he was admitted there and both of us were receiving treatment following accidents. We met in the unisex restroom, when we were brushing our teeth together! He beamed a friendly smile at me and I introduced myself and it was an instant friendship. I think that the two of us had more energy put together than all of the rest of the patients who were too old, tired, hurt or worn out to even make an effort at connecting with others. Kyle and I would talk and talk or listen to music and then talk about music after the other patients had gone to bed. Sometimes we played games and I would stack the table high with the ancient encyclopaedias in the lounge to raise the board as he couldn’t look down due to the halo for his neck injury. He was the age of my children so that was comfortable for me, and calming. As an American physician, being in a large ward of a public hospital in a foreign country was a terrifying experience and something I had never contemplated. My friends were urging me to go back to the US for treatment, but we had stopped our US insurance and had bought a house and land. We were determined to make a new life in New Zealand, even if it meant my being sick there!

Spending time with Kyle made me forget about my worries, then I met you, your daughter, and your son James and that was great! I was sad when Kyle told me that he was being transferred to Auckland. When he told me more about the rehabilitation program, I was happy for him to get specialized care. Before he left, he gave me a pyramid shaped rainbow quartz crystal. At first, I refused it-telling him that he should keep it as he might need it. But I have to admit I was really craving it! Kyle told me that he could get more because James collected crystals and insisted that I take it. Kyle’s generous spirit extended to other patients as I saw him give chocolates to some of our ward mates on the day he left for Auckland. James later mailed a package brimming with crystals to my home! Your sons are remarkable in their generosity at ages 19 and 20! The rainbow quartz crystal radiated on my hospital bedside table. Its shine beckoned me in the sunlight or moonlight and I felt peace, knowing that we are all connected to the Divine and are not called to suffer more than we are able. I thought of Kyle, and would pray for him, I thought of my children singing Over the Rainbow, and of happier times and I would be comforted. When Kyle’s pain overwhelmed him and he ended his life, I renamed it the Kyle crystal. When I was hospitalised over the following months, I took that crystal with me and I remember showing it to you when you visited me on Ward 6-where Kyle had been hospitalized.

It must have been tough for you to walk through those memories that afternoon, and your visit uplifted me tremendously! Kyle shared his dreams of traveling with me, and I’ve taken his crystal to six continents in exploring incredible places on our Earth. When I moved to Guam I brought all of my crystals with me and reflected, I want to be like Kyle-a Light, a Friend, a genuine Smile that says, “I care about you, I’m happy to help you today”. I first lived in an apartment, and then moved to a friend’s condominium near the beach. Somehow during my packing and moving the Kyle crystal was lost. I was distraught, I checked every corner of that place several times on my days off, and could not find it. That was in September, and then in February I had had an extremely tough day. I saw a middle aged male patient with severe pain, cough, difficulty breathing, and weight loss. He was alone in the world. During the interview he said numerous negative things about himself. When I examined him and realised the serious nature of his diagnosis, I was personally impressed with his stoicism and that despite his health demise he was going to work each day. After obtaining the initial test results, I delivered the news that I was phoning the ambulance, and he would go emergently to the hospital.

His eyes widened in terror,“ What will they do to me?” I knew the terror and anxiety that my patient was feeling. I comforted him assuring him that I would go to the hospital as soon as I could and check on him. Usually on Guam, I take food to the hospital yet this particular man could hardly breathe, must less eat delicious treats! Arriving home that evening, I was drawn to look at my crystals. When I opened the drawer to retrieve them I saw a scrap of newspaper, and wrapped inside was the Kyle crystal! I must have overlooked it! Or maybe it was supernaturally placed there? I don’t know, but I was overjoyed to see it! All of this happened on a significant death anniversary of a family member. The crystal looked and felt the same and I held it awhile. Suddenly the idea came to me-I was to give this patient a crystal. Just like Kyle had given me one when I was in the hospital. His gift was a symbol of his own generous spirit, yet the gift itself is valuable. I wanted to create this experience for my patient-to give him something to hold to, to help him endure the suffering ahead. I studied the crystals that James had given me, waiting for guidance. I was attracted to the obsidian. I picked it up, if felt right. Then I went to the computer to search for the healing properties associated with obsidian. I was amazed as they were precisely attuned to this patient: overcoming negative thoughts and emotions, perseverance through darkness.

I wrote this on an index card and went to the hospital. I was getting ready to leave the bedside as he thanked me for the visit, when I shared that I had brought him a gift. I revealed that just like him, I was suddenly admitted to the hospital years ago, and I too was afraid and far away from my family and friends. I continued, “ Being a doctor actually increased my fear as I was keenly aware of the medical errors that may occur and the extreme vulnerability of the patient. It was one of the toughest moments of my life and a fellow patient helped me through the terrible experience. His name was Kyle, and he was a patient with a head and neck injury. When he was being transferred from our shared ward, he gave me a crystal and it encouraged me and brightened my days. “ I presented the obsidian to the patient, placing it on his bedside table, then read him the index card. He smiled, even giggled for the first time since I had met him. He looked at the crystal with a type of hunger in his eyes. He excitedly said, "What do I do with it? I’ve never had a crystal before!” I shared that he could do what I did, sometimes during the day hold it in his hand, and if he was having pain or a procedure was being done he should put it in his pocket or keep as near to his body as possible. At other times he could look at it-it is a mirror stone, or he could remember that meaning, and think positive thoughts about himself, like the things I saw.

He quickly grabbed the crystal with his right hand in his agonal state, and he opened and shut his fist looking at it intensely. He looked at me shyly and inquired, “What type of positive things?” I told him that my impression was that he was a dedicated and loyal employee, and that he was quick witted and clever. He seemed surprised, but didn’t argue with my comments. I don’t know the rest of his story, but someday I’ll find out. I wanted to share this story of how Kyle and James have helped me, and others.

This piece began as a patient narrative, but quickly evolved into something more personal. As I wrote, I found myself grappling with how often we-especially in medicine-rationalize our own suffering while tending to others. This story isn't just about physical illness. It's about grief, emotional suppression, and how easy it is to disappear into responsibility. The character's descent into illness mirrors a descent that many of us face silently, when we keep pushing through without pausing to ask how we're really doing. This piece for me became a reflection on what it means to be a caregiver in a system that often rewards endurance more than self-awareness. It's a reminder that tending to others shouldn't come at the cost of abandoning ourselves.

Raj Shah is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix, pursuing a dual MD/MPH with a focus in rural and Indigenous health. Before medical school, he worked as a rural EMT and ski patroller on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona. Throughout medical school, he has continued working with Native communities across Arizona in a variety of clinical, academic, and volunteer roles, deepening his commitment to community-centered care. Raj is now applying into general surgery, with long-term goals of improving surgical access in underserved populations.

It was a beautiful day. He was with his family, working a steady job, attending school to pursue his passion. Then he started feeling a little fatigued. Nothing alarming. Just stress, he thought. School and work were piling up, so of course he felt tired. Then came the appetite loss. Still, he rationalized: maybe this was a good thing… he’d been wanting to lose weight anyway.

Then a low-grade fever and mild cough. Maybe a virus he thought. He went to the ER. They told him it was likely viral and sent him home with Tylenol. He was relieved it wasn’t something worse.

But a week later, his symptoms hadn’t improved. He thought about going back to the hospital, but his grandfather, the man who raised him, was suddenly very ill. And so he set his own health aside. For the next two weeks, he stayed at his grandfather’s bedside, barely noticing how his own body was failing him. After multiple hospital visits, his grandfather passed away. The grief hit hard.

Was the fatigue from the infection or from the heartbreak? Was the insomnia physiological, or just mourning? He couldn’t tell anymore. And he didn’t have time to figure it out.

Eventually, he returned to the hospital. This time, they told him he had an empyema—an infection that had silently encased his lungs. He was sent in an ambulance to the nearest academic medical center and was told he needed urgent surgery or risked going into septic shock.

He was told he’d probably wake up with four small incisions on his chest. But when he woke up, he saw a long incision running across the chest, multiple tubes draining from his body, and a catheter collecting his urine. The infection had been far more extensive than anticipated. They’d had to open his chest entirely.

He stayed hospitalized for two weeks, poked, prodded, unable to sleep, in a kind of pain that he described as both physical and existential. Dozens of healthcare personnel moved in and out of his room, asking questions, adjusting settings, writing notes. But none of them really knew him.

And because he lived far from the hospital, he endured much of this without the presence of family.

He began to wonder: Should I have gone to the hospital sooner? Did I make a mistake putting my grandfather first? Why didn’t they catch this the first

time? Am I going to lose my job? My classes? How will I pay my bills? Everything suddenly felt unstable.

This was the story of a kind, thoughtful 26-year-old individual who became my patient.

I first met him that morning during rounds. He was quiet, polite, and looked exhausted. Just another name on our list—until a few hours later, I was scrubbed in, my gloved hands inside his chest, helping clear the infection that had nearly taken his life.

The shift felt jarring. One moment I was at his bedside, the next I was inside his body. It’s one of the strange truths of this profession: our proximity to suffering can change so suddenly, so intimately, we often don’t have time to process it. But with him, I did.

We shared stories and got to know each other during his hospital stay. I sat beside him each day, not just changing dressings or checking tubes, but giving him space to talk about his life outside the hospital, to cry, or to simply vent. What I expected to be a clinical responsibility became a bond I’ll carry with me for the rest of my life.

He trusted me enough to let me witness him not just as a body healing from infection, but as a person caught in life’s relentless, unforgiving pace. And in that process, I saw myself in him.

Empyema in someone that young is rare. That it progressed so quietly, while he experienced only subtle symptoms, made it even more unusual. As clinicians, we rely on statistics. We talk about likelihoods. But when the improbable becomes someone’s reality, those numbers stop meaning anything. He was the less than 0.001 percent.

And it made me wonder: What have I been pushing aside in my own life, brushing under the rug, convincing myself I’ll deal with later?

Maybe it’s not an infection in my chest. Maybe it’s the emotions I compartmentalize to get through the day. The calls to my family that I keep putting off. The growing list of small sacrifices I make in service of a bigger goal—but at what cost?

This experience reminded me that the very things we ask our patients to do such as listening to their bodies, honoring their needs, seeking help early, are often the things we fail to do ourselves. Life imitates medicine in that way. The neglect accumulates quietly, until it demands to be acknowledged.

I don’t know that I would have done anything differently than he did. Life moves fast. Responsibilities pile up. People depend on us. And so we delay tending to ourselves.

But if we don’t make space for our own healing, life will eventually force it upon us.

I hope we remember that our well-being—physical, emotional, spiritual—is not selfish. It is essential. I hope we continue to check in with ourselves, to care for the parts of us no one else can see, and to recognize that sometimes, the person who needs the most urgent care… is ourselves.

The Huichol (Wixárika) people of Mexico offer a rich cultural perspective on health and art. While specific data on kidney cancer in the Huichol is limited, indigenous communities often face health disparities. In rural Mexico, limited access to cancer detection and treatment leads to worse outcomes. Broader statistics show that Mexican Americans and American Indians have a 50% higher mortality rate from kidney cancer compared to whites, hinting at genetic, environmental, or healthcare access factors that may also affect the Huichol. Chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension, which increase kidney cancer risk, are rising in many Native communities. Although kidney cancer is not traditionally recognized in Huichol health lore, raising awareness is crucial as indigenous peoples often lack cancer education and screening.

Huichol art, particularly their yarn paintings (nierika), provides a spiritual framework for discussing health. Historically, these colorful mosaics, made from yarn pressed into beeswax, were offerings created by shamans to honor deities. The motifs—sun, rain serpent, corn, flowers, and blue deer—represent life, growth, and balance. In Huichol culture, “art is prayer,” linking artistic expression with healing, as creating art is seen as a direct communication with the gods for blessings on health and well-being.

Olivia Triplett is a fourth year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix. During her undergraduate studies, she worked as a medical assistant at the Allergy and Asthma Center of Boston in the lab of Dr. Weihong Zheng. She also gained research experience at at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Pfizer, Casma Therapeutics, Chroma Medicine, and the Cram Lab at Northeastern University. Outside of work and school, she enjoys visiting national parks, and bothering her cats, Ellie and Eddie. She is interested in pursuing a career in Oncology.

“The hours are terrible, the pay is terrible, you're underappreciated, unsupported, disrespected, and frequently physically endangered, but there's no better job in the world” Adam Kay

Medicine calls people to it as physicians and the life they invest and live becomes one with the practice they commit to. Imitation is the embodiment of an ethos and the seams are so invisible there is not distinguishing the doctor from the person or the person from the physician.

Dr. Jean Robey is a nephrologist who practices Narrative Medicine, writer, and poet. Her book Evesonderism: Living the Story of the Art of Medicine comes out September 2025.

By the middle of Painting

Your masterpiece

You will have been asked

Past a moment of clarity

To the very brink of questioning it all

Why medicine?

“I used to know,” you’ll say It’s ok

Really.

We all think this from time to time

Till we are coercing a childhood dream to sleep a bit longer in idealism

All the distress

Protesting the alternative future

All the asking with humility

The passing fun others have

The chilling truth of death breathing our air

Sharing our space

When we haven’t even dared to fall in love or build families

Driving others to drown in our audacious

Plans and empathy

Will eventuate

No longer waiting but hesitating In the decision

To be all in

All accountable

Still in love with Medicine

Why medicine?

Why is our life fusing with a course By our design By our choice

That places us humble holding something universally unclear and far from casual?

We are too much a dedicated idiot Conspiring with surreal serendipity

To ever take a bathroom break till we check on someone sick

Is life imitating medicine

When medicine imitates art

And we are asking please

Please, please Please

Let me join and be a part

Of a masterpiece to its’ last oily stroke As a physician

Helping the hardest won victories

Body Mind

Destiny Against death Against suffering

I put a ring on it

I put a thing before myself and all else many times

There is no life

Without medicine

No medicine better than living

No living without art

Without being apart of this Madness

We call doctoring for some of us

It is seduction

Constructing the very brink of questioning it all

Until the sun rises over and over

On the horizon that calls us even now

To a life repeatedly healing wounds and ripping out the dying parts

Poisoning the poisonous parts

Starting over

To realize we should never work so hard

Hopeful Reassuring

Grace and honor falling over in over in love with upholding Humanity

As we exemplify it

Every day calling ourselves

Someone’s doctor

And end the day doctoring ourselves

A poem I wrote during the COVID-19 pandemic and revisited during my time in the ICU about the often ironic connection between human connection and medical illness.

Nicole Varda is a fourth-year medical student, interested in primary care with a passion for health humanities, creative writing, and bioethics.

I miss chapped lips and crooked smiles and day-old shaves

A whole person, unobstructed and unaltered. There is something inherently sad about all these half faces.

Squinted eyes a poor substitute for grins.

I miss brushing shoulders and grasping hands and saying bless you without reaching for sanitizer and paranoia, in my back pocket. Always.

This piece was written as a reflection of my time spent on the trauma surgery service during my MS3 year. Especially early in the rotation, it was challenging to adapt to an environment where seeing and inflicting pain and agony was a daily ritual. However, as this piece reflects, by the time my 8 weeks of trauma were done, I came to understand the necessity for it and even appreciate the importance of our work.

_______________________________________

Ellie Pitcher is a 4th year MD/MPH student at the University of Arizona planning to specialize in OB/Gyn. In her spare time, she enjoys cooking, reading, hiking, and hanging out with her dogs.

Doctors have a unique capacity to do harm. Nowhere is this more evident than on the trauma service. Our patients come to us on the worst days of their life, often convinced that they are dying. From the moment they arrive, they are terrified. Put yourself in their shoes for a moment.

Your dignity is stripped away as we methodically remove your clothing in a brightly lit room with dozens of onlookers. We ignore your questions and demand that you stop talking so we can better hear delicate breath sounds. No, you cannot have any water. No, we don’t know if your loved one survived. We withhold pain medications until we are satisfied that we have accurately assessed mental status. We press hardest where it hurts most. Exquisitely tender, rigid abdomen? We push on it. Shortness of breath and chest bruising? We push on it. Back pain and paresthesias? We push on it. Next, we roll you side to side, even though your femur is shattered and your distal leg fails to move with the proximal portion. We make you do absurd things, like wiggle your toes - and when you can’t and your distal pulses are absent, two of us tightly grip your leg and torturously pull it back into position. If the bleeding won’t stop, we systematically cut off the blood flow with a tourniquet. The leg will turn

purple and feel like it’s dying - because it is. We’re killing it. Next comes the imaging. Yes, your arm is dislocated and that ankle is likely broken: but we need you to stop moving so we can get a better picture. We know it hurts, just take a deep breath and hold still. Downtrending oxygen saturation and fluid on chest x-ray? Here come the surgeons again, dressed in funny gowns and gloves. They are going to cut you open and slide a long tube into your chest. Yes, it’s going to hurt. Try not to move. When our work in the trauma bay is done, it’s off to the CT scanners. Finally, some pain meds - just in time for you to lay in isolated silence, feeling alone and no less terrified.

Our trauma evaluation is often a symphony of agony. However, it doesn’t take long to recognize those noises as reassuring. We relish in the screams and moans, because it means that we have time. The patients that scare us are the ones who make no noise. The man who was found down in a puddle of bloody vomit: every breath is a quiet gurgle as bloody foam slips out of his mouth and the beeping from his monitor slows and then becomes a constant, high-pitched quiet scream. The man who jumped headfirst off a building: his ventilator huffs and puffs as blood quietly drips from his head onto the floor. A

staple gun fires again and again. Another package of gauze is opened. More dripping. We can’t stop the bleeding. The woman who was run over, again and again: her LUCAS pounds away, then we remove it and an eerie silence stretches on while we stare at the ultrasound screen. No cardiac activity. 50 minutes down. Nothing to do.

Although we have the capacity to cause harm - and we do every day on the trauma service - we do it with the knowledge that we can save these people. Although our oath says nonmaleficence, there’s an imaginary asterisk next to it - a little harm is okay, if you’ve got the right intentions.

This piece is about a young family I met while attending daily ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) rounds in the pediatric intensive care unit. I was struck by the contrast between the complex, often somber medical discussions surrounding her care and the gentle, positive presence of her mother. One of my research interests is exploring how music can support the well-being of hospitalized children, which inspired me to focus on the auditory components of this experience. The melody of this mother’s voice reminded me of music, hushing the harsh, unfamiliar noises of hospital.

Lauren Ondrejka is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, applying to pediatrics this year. She earned her Bachelor of Science in Health Sciences from the University of Arizona in Tucson, majoring in Physiology with minors in French and Biochemistry. Born and raised in Arizona, she enjoys spending time with family and friends, trying new restaurants, and attending live music, dance, and theatre performances around the valley. Though initially drawn to the health humanities through her love of music, she has since been inspired by her colleagues to explore linguistic and visual expression through writing and painting.

Millions of miniature tubes, five flashing monitors, countless stickers and sensors

Humming, beeping, hissing

Hushed chatter about your gases, pressures, perfusion, flow

Parents propped up against the doorframe

Faces pale, puffed up with exhaustion, brows drawn together

Concern, confusion, fear

An open chest with a tiny beating heart shielded only by antimicrobial plastic wrap

“Sternal precautions: don’t lift me under my arms!” the sign warns

It hangs next to the one spelling your name

Whimsical cursive letters and pink ribbons tied in bows

Clear, thick tubes dive beneath the plastic wrap

Pull dark purple from the veins

Push bright red to the arteries

Mom hovers over you, always

Whispering stories, murmuring sweet words

Stroking hair, squeezing hands

I hope you hear her

Over the humming, beeping, hissing

The human mind can be chaotic in of itself, and with all the technology that is available to us, it is too easy to get overwhelmed in today’s world. As a practitioner of meditation, I have found the breath to be useful in connecting me to the present moment, and I often marvel at the power of such a simple action.

This reminded me of my time in the hospital, where advancements in medicine abound. However, sometimes what is needed is a return to the basics, and I was grateful to learn this early in my third year when I witnessed a conversation between my preceptor and the family members of a patient who was being considered for hospice. Through the discussion, he sought to understand the values and wishes of the patient and the perspectives of the family, and I saw how he guided them through and helped them come to a realization about the patient’s care.

Just like the breath, the conversation was a simple but powerful tool that served to keep the patient front and center, and sometimes, that is exactly what is needed.

Lauren Dimalanta is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix.

Advances many Often helpful but sometimes Simple is enough

After an intern year spent navigating the grief, overwhelm, and chaos of the 2020 covid pandemic, I struggled immensely with burnout. This patient allowed me to fall in love with medicine again during my PGY2 year. Unfortunately, this patient passed away. I has the honor of reading this 100-word love story I had written in her memory during her memorial service. Alongside her loved ones, I found myself grateful for moments that transcend our roles as physicians and have allowed me to once again practice medicine with my whole heart.

Dr. Miriam Robin recently completed her Chief Residency in Quality Improvement and Patient Safety at the Phoenix VA and junior faculty at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, where she completed her Med-Peds residency. A graduate of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, she also holds a BS in Biological Science from Florida State University, where she was Phi Beta Kappa.

In residency, she developed her program’s first anti-racism curriculum, created a pipeline partnership for underrepresented pre-med students, and launched a scholarly mentorship initiative that produced 42 accepted abstracts—over one-third co-authored by underrepresented trainees. Dr. Robin received an ACGME Back to Bedside grant for her Inclusive Hair, Inclusive Care project, which pairs cultural competency education with inclusive hair kits.

Recognized for her work in education and equity, she has received multiple awards and is published in The New York Times and SGIM Forum. Her work centers on joy, inclusion, and social justice in medicine.

“But you’re my doctor,” she said when I mentioned that the attending physician would soon be in to examine her. “And I ordered something special for you.” She unfolded a napkin on her breakfast tray. Inside lay single-serving packets of peanut butter and grape jelly, an ode to my professed love of the Smucker’s Uncrustables peanut butter and jelly sandwiches that had helped me get through my first year of residency. In that moment — after a harrowing year in the trenches of the pandemic — I remembered why I chose medicine.

The peanut butter and jelly packets my patient ordered for me.