SINGLEHOOD

IN THE

What does your dream career look like— is it in a courtroom, boardroom, or saving lives in the ER? Maybe you want to earn a graduate degree or conduct cutting edge research. If you’re ready to explore a world of opportunities, TOURO TAKES YOU THERE.

touro.edu/poweryourpath

NAOMI PERLA, ASSOCIATE DEBEVOISE AND PLIMPTON, LLP

NAOMI PERLA, ASSOCIATE DEBEVOISE AND PLIMPTON, LLP

Fall 2023/5784 | Vol. 84, No. 1

OU KOSHER CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT

Rabbi Yacov Halevi Lipschutz

By Rabbi Menachem Genack

By Rabbi Menachem Genack

TRIBUTE

Remembering

Rabbi Matis Greenblatt

By Joel M. Schreiber, Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg and Rabbi Emanuel Feldman

JEWISH LIVING

Can’t We Just Get Along? Living Side

By Side in Peace and Harmony

Singlehood in the Community: Are We Missing the Mark?

e Crisis of My Experience By Anonymous

REVIEW ESSAY

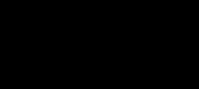

Unmatched: An Orthodox Jewish Woman’s Mystifying Journey to Find Marriage and Meaning

By Sarah LavaneReviewed by Rebbetzin Faigie Horowitz

THE CHEF’S TABLE Signs, Sealed, Delivered! By Naomi Ross

LEGAL-EASE

What’s the Truth about . . . e “Expiration Date” of Rabbeinu Gershom’s Ban on Polygamy? By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

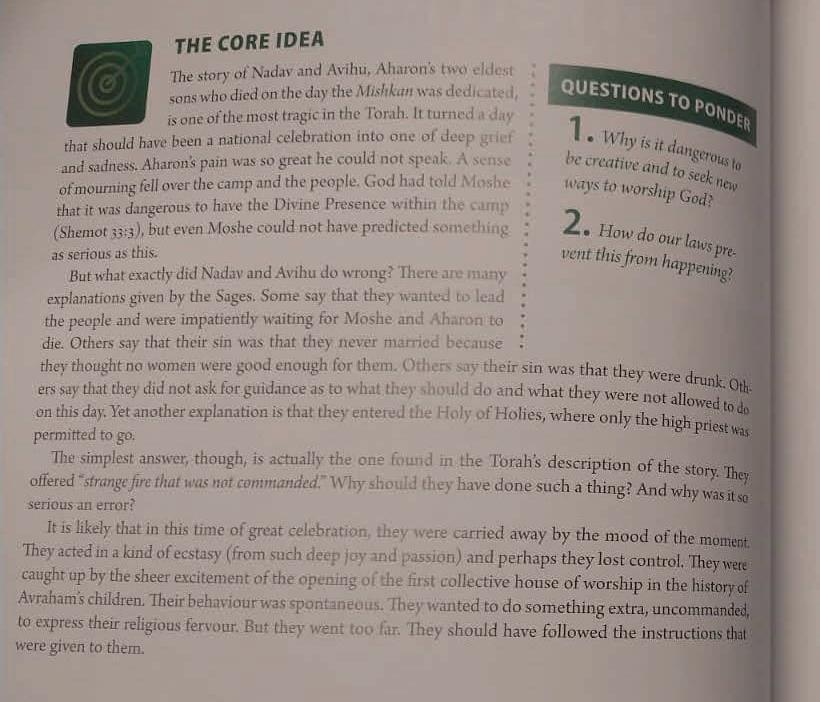

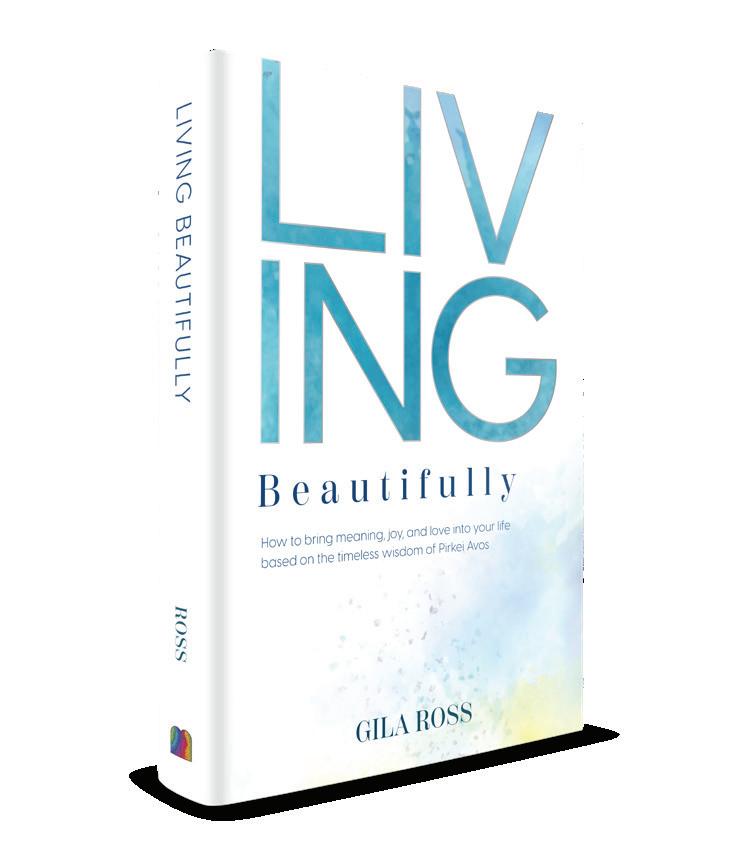

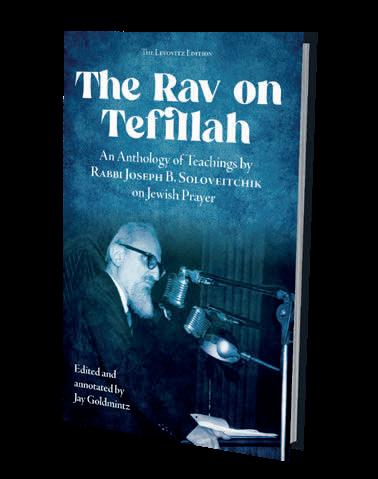

NEW FROM OU PRESS

By

Sam Ellenbogenand Michael Waldner, as told to Nechama Carmel; Rabbi Shabsey Gartner, as told to Steve Lipman and Leah Lightman; Tova Herskovitz, as told to Steve Lipman; Sid Laytin, as told to Merri Ukraincik; and Mindy Pollak, as told to Merri Ukraincik

Deeds

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors: Stories of Communities at Came Together

By Steve LipmanJEWISH THOUGHT

In Search of Spirituality: A Symposium

A Simple Experiment: How Members of One Shul Sought to Change the Way ey Daven

By Rabbi Noah ChesesLETTERS

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Outrage

By Mitchel R. AederFROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

e Division ing: Strangers, Competitors and Monsters

MENTSCH MANAGEMENT

Answering the Call

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

ON MY MIND

Confronting the Suboptimal

By Moishe Bane

86 90 94 98 100 102 104

INSIDE PHILANTHROPY

Major New Gi Enables OU to Expand Its Focus on North American Communal Growth

BOOKS

A Guide to the Guide

By Rabbis Yosef Chaim Elazar Kohn and Yaakov Yosef Reinman

Reviewed by Rabbi Shmuel Phillips

Reviews in Brief By Rabbi Gil Student

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Witnessing the Power of Chesed

By Sara Spielman

IT'S YOUR TIME TO RISE AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY.

Israel. Rabbi Alkalai did not only speak of the return to Israel as a solution to the perennial problem of antisemitism but as a way to ful ll the Jewish aspiration for political normalization—Jews living in their original homeland.

Rabbi Alkalai understood that Jews do not need to wait passively for Mashiach to achieve this aspiration; on the contrary, he saw the return of the Jewish people to Israel as the way to facilitate (and advance) the arrival of Mashiach. In his book Goral LaHashem, Rabbi Alkalai formulated the religious foundations of his vision and the practical steps to be taken to reestablish the Jewish nation in Israel. e book was published in three di erent editions and translated into many languages, including English.

Another great example is Rabbi Yaakov Meir (1856–1939) who was blocked from the position of chief rabbi of Jerusalem in 1906 for being “too Zionistic”; he was sent on shelichut to Bukhara and essaloniki, where he worked to ingather the exiles by promoting resettlement in Eretz Yisrael. He returned to Israel in 1921, and with the help of Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, was elected Sephardic chief rabbi of Israel (Rishon LeTzion) until his passing. Along with Rabbi Chaim Hirschensohn, he also founded Safa Berura, an organization that worked to reestablish Hebrew as a spoken language (a notable member of the organization was Eliezer Ben-Yehuda).

It is my hope that future articles in Jewish Action will be a source of pride to all Jews—Ashkenazim and Sephardim—as we continue to work together to build Eretz Yisrael both physically and spiritually.

Jack Dweck Brooklyn, New Yorke issue dealing with Torah and arti cial intelligence (“Torah in the Age of Arti cial Intelligence,” spring 2023) presented interesting discussions of technology and its potential use in halachic decision making. e tone was generally positive and optimistic. I was, however, expecting some consideration of the downsides but did not nd any.

Let’s consider three examples. We are generally taught to nd a halachic authority to follow, whether it be the rebbi who teaches you in school, the rabbi of your shul, or some other gure who inspires you. We are told not to sample multiple sources and nd the pesak that we like. But it’s exactly that behavior that AI will indirectly encourage by the ease and speed of querying. Searching for a kula (or a chumra) will be a breeze.

Second, in his article, “AI Meets Halachah,” Rabbi Dr. Aaron Glatt wrote that the process of giving a pesak is not mechanical. A single posek can give di erent answers to the same question, based on his knowledge of the person asking. Many AI experts are predicting that approximately two years from now, most internet users will have a personal AI “agent.” Instead of jumping from website to website to

order pizza, make an airline reservation, purchase tickets to a play and nd tomorrow’s weather forecast, you will simply talk to your agent a er logging in, and request the actions or information. More than that, the agent will o er suggestions based on your past requests, likes and dislikes. At the beginning, you will feel surprised that the agent seems to make such good choices, but eventually you will take it for granted, like the ideas of a good friend. It’s not a stretch to say the same will apply to your halachic questions. All of the background information that impinges on the pesak, from your budget to your family situation to your physical and psychological health, will be accessible to AI in o ering a decision. is will be a challenge to human posekim ird, though it may sound extreme, we have to think about avodah zarah is concern arises from our unavoidable tendency to humanize robots and AI. A robot technology company created a robot “dog” with metal boxes for its body, neck and face, and four rods for legs. To demonstrate its programming, a person with a baseball bat struck the dog, knocking it over. e dog quickly got up, ready to do its master’s bidding. e dog was struck several more times, each time quickly righting itself. A video of this demonstration on the internet resulted in thousands of responses from horri ed viewers, expressing shock and anger at such cruel treatment. An AI taught to interact with people will be humanized at a much higher level. With its amazing knowledge of facts alongside its familiarity with your personality, the AI agent will likely gain the status of an authority gure in your life. e Rambam, in explaining the source of avodah zarah, describes a process starting with the observation of moving stars and ends with the creation of personal idols. is does not di er much from the process of rst seeing AI as a general information resource, and nally relating to it as a trusted friend.

Today, the technology world is divided over the future of AI. Is it a threat or the ful llment of unlimited promise? No matter which side one takes, the best choice is to be prepared for the expected as well as the unexpected.

Dr. Irv Cantor

Jerusalem, Israel

Rabbi Dr. Aaron Glatt Responds:

I thank Dr. Cantor for his interest in Jewish Action’s AI issue. e articles addressed speci c aspects but could not focus on every eventuality. Much still remains to be learned about the potential bene ts and pitfalls of AI.

e examples of concern cited are all problems we have today with any good search engine. Indeed yes, AI might exacerbate these issues further. However, certain intangibles, such as di cult-to-quantify interpersonal relationships and character traits that a posek takes into account, cannot be duplicated by AI—at least not in the near future.

IT'S YOUR TIME TO RISE AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY.

In his piece “ e Best Is Yet to Be” (spring 2023), David Olivestone doesn’t recall the question being raised as to why Robert Browning chose Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra, the twel h-century paytan and author of one of the classic commentaries on Tanach, as the narrator of his poem “Rabbi Ben Ezra.” I, however, vividly recall the question being asked during my doctoral oral examination and dissertation defense. Actually, “Rabbi Ben Ezra” has less to do with Browning’s interest in and fascination with Hebrew, Judaism and rabbinic literature and much more to do with Ibn Ezra’s twel h-century contemporary Omar Khayyam, a celebrated Persian poet, philosopher and grammarian.

Browning was responding to Edward Fitzgerald’s wildly popular “ e Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam,” which extols the joys of youth, carpe diem hedonism and unbridled sensuality. e “Rubáiyát,” as one critic points out, “captures the imagination of its Victorian audience who had been raised singing pious hymns at church on Sunday.” It rejects the Victorian code’s emphasis on self-control, moderation, social convention, the spiritual life, Christian morality and the wisdom that comes with age. Browning’s “Ibn Ezra,” a venerated scholar of the same period as Khayyam, eschews the cult of Khayyam and posits a more balanced view, arguing that youth is but one phase of the soul’s experience and that it will fade—replaced by wisdom, perspective, and the insights of age; it is not the end of one’s life, but the beginning of something more. Or as Betty White’s mother always used to say, “ e older you get, the better you get, unless you’re a banana.”

To appreciate the contrasting messages, I refer readers to Frederick Leroy Sargent’s Omar and the Rabbi (Cambridge, 1911), which combines the translation of the “Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam” and Browning’s “Rabbi Ben Ezra,” and presents them in dramatic form.

Herbert Schlager Queens, New YorkIn “Unscrambling the Kashrut of Eggs” (summer 2023), the article erroneously implied that a fertilized egg must be discarded only if a blood spot appears in the yolk. This is incorrect. If a fertilized egg has developed to the point that a blood spot appears in any location, the entire egg becomes forbidden and should be discarded (Rema, YD 66:3).

In July, at the American Jewish Press Association (AJPA) Conference, Jewish Action won seven Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism for work that appeared in 2022. The magazine secured first place in the Excellence in Writing about Health Care category for Rachel Schwartzberg’s “Unplugging the Digital Generation.”

“The Future of Food,” by Barbara Bensoussan and Merri Ukraincik, won first place in two categories: Excellence in Business Reporting and Excellence in Writing about Food and Wine. Aviva Engel’s “The Divorced Family,” which included personal stories from divorced parents as told to Steve Lipman and Tova Cohen, received second place for Excellence in Writing about Women, and Aviva’s second piece, “Supporting the Divorced Parent,” earned second place for Excellence in Writing about Social Justice and Humanitarian Work.

The magazine also won honorable mention in two categories: Excellence in Writing about Food and Wine for Rafael Medo ’s “Keeping Kosher, Becoming American,” and Excellence in Writing about Health Care for “Habits of Emotionally Strong Families” by Sandy Eller, Leah R. Lightman and Steve Lipman.

is magazine contains

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org. Letters may be edited for clarity.

divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin.

IT'S YOUR TIME TO RISE AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY.

of social media have exacerbated this destructive phenomenon.

By Mitchel R. AederIt is no secret that our society feels extremely polarized. Of course, this is nothing new. When I was a kid in New Jersey, you were either a Mets fan or a Yankees fan. Never, ever both.1 at was real polarization. As a Mets fan, I was blessed to come of age during the glorious years (1965-1976) between the Yankees’ glory years. Nonetheless, some of my best friends were Yankees fans. We were able to put our ideological di erences aside when talking about less important things, like family, schoolwork and soccer.

Today, society seems to be irrevocably split along social, political and religious lines. We listen to or read only news that is presented from our parochial perspective, except to ridicule the other. In 2020, the Pew Research Center reported that 45 percent of adults have stopped talking to someone about politics as a result of something the other person said.2 e polarization is re ected in the coarseness of public “discourse.” Debating has ceded to screaming.3 e ubiquity and anonymity

is modality of “communication” has unfortunately in ltrated our Orthodox Jewish circles as well. In my travels, I recently came across a local weekly newspaper written by and for the Orthodox community. In addition to the local news, this paper features several opinion columns. A number of the columns, whatever the topic at hand, were strident, even angry. So far, so bad. Far worse were the letters to the editor, which expressed outrage (outrage!) at a variety of opinions expressed the previous week. Unfortunately, this newspaper is not unique. On social media and podcasts as well as in print media, certain topics (did someone mention President Trump?) are guaranteed to unleash a torrent of angry screeds.4

Do we really have to speak that way? Must we print those who do?

Let me bring this home. At the Orthodox Union, we make decisions daily that a ect the community. Some of these decisions are operational (how much to charge for a particular summer program), others involve public policy (should we make a public statement or le a legal brief?), and yet others involve institutional priorities (what role, if any, should the OU play in combating antisemitism?). Each decision is weighed and debated, taking into account cost, expertise, likelihood of success, extent of communal consensus and impact on existing programs, among other factors. O en, we seek guidance from posekim and other rabbinic leaders. Still, reasonable people may disagree with virtually every decision we make. We welcome feedback and debate. What we get too o en, however, is vitriol.

e problem with outrage goes beyond derech eretz or how one should speak to another human being. It

evinces a lack of respect—how could anyone have been so stupid to have done or said that? Even if the obligation to judge people favorably, to be dan l’kaf zechut, does not require one to agree, it does demand that we give the other person the bene t of the doubt that they considered the issues and reached a reasonable conclusion. Again, people disagree. Respectfully. In any event, screaming is ine ective. People tune it out. Here is an example of a recent issue that generated both thoughtful and, alas, vitriolic comment.5 In February, in response to a horri c terrorist attack in which Hallel and Yagel Yaniv, Hy”d, were murdered in the Shomron, a group of Jews rioted in the Arab town of Huwara. e OU published a statement condemning the riots. We received some outraged and outrageous responses, questioning whose side we are on. ese comments were hurtful, but not impactful. We then received a quiet, thoughtful rebuke from someone who questioned our having failed to publicly condemn the original terrorist attack. We had not done so, because we presumed that everyone knows where we stand on anti-Jewish terrorism. He argued that our fair rebuke of the rioters was undercut by our failure to acknowledge the pain of the Yaniv family, their friends and Klal Yisrael. We took this comment to heart and spoke out a er the following terror attack which, sadly, was only days later.

Other recent issues that elicited hate mail include: (i) our meeting with Israeli Finance Minister Betzalel Smotrich (from the le ), (ii) our note of gratitude to the Biden administration for its antisemitism initiative (from the right); and (iii) the amicus brief we led in support of the lawsuit that (successfully) challenged the New York State Department of Education’s overreaching regulations designed to force Chassidic yeshivas to introduce

more secular studies into their curriculum.6

Strong feelings are not limited to the political arena. Some people feel very passionately that kosher certi cation should concern only food preparation and not other religious or social issues. Others feel equally passionately that the OU should withhold certi cation from products with o ensive packaging; from restaurants to which one would be embarrassed to bring a rosh yeshivah; and from companies whose corporate values are antithetical to Torah values. Is either side objectively correct? Is either position unreasonable?

is is not about being thin-skinned, and it certainly is not intended to sti e dissent. As one of my colleagues eloquently noted: “Anyone may inquire about our statements or silence on speci c issues. We do not expect blind faith, and we o en gain from hearing the perspectives of others. I would hope, however, that those inquiries would not come as an attack, but rather take the form of a query, giving us the bene t of the doubt that we choose our approach to issues precisely because we are ercely committed both to Torah values and to the wellbeing of our community and work hard to balance the various considerations as to how to advance those causes.”

When is outrage appropriate? Clearly when dealing with chillul Hashem and antisemitism, with falsehood, malice and the like. But even here, one should be thoughtful and strategic about one’s tone, especially but not exclusively when addressing an “internal” audience. ere are Jewish organizations that have only one volume. I wonder if anyone listens.

People are in uenced by their environments. We are living in an environment that favors moral indignation over collegial debate. We must try to push back against this, especially when we speak to each other. As Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur approach, perhaps we can undertake to lower the volume, to hear and to be heard.

L’shanah tovah tikateivu v’techateimu.Notes

1. ere was a persistent rumor that there were twenty-two other teams, none of which mattered whatsoever.

2. Not that things have improved. In 2023, Pew reported that two-thirds of Republicans and Democrats view members of the opposite party as more “immoral.” Yikes!

3. For over thirty years, PBS aired Firing Line, in which staunch conservative William F. Buckley debated the issues of the day primarily with liberal thinkers. It’s hard to imagine such a show having a platform, or an audience, today.

4. Rabbis Aaron Lopiansky and Yosef Elefant pointed out at an Agudah convention a couple of years ago that Torah values are determined by the Torah, not by the platforms of the Republican or Democratic parties. Woe that they felt a need to say this.

5. As tempting (and entertaining) as it would be to quote the o ending emails and posts, this is a family publication.

6. e OU’s position was that while the State has an interest in its citizens having su cient education to perform civic duties and be economically self-su cient, the regulations went well beyond that and encroached on religious liberty.

Aviv Avnon | Finance

U.S. BASED EXPERIENCE

Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP

U.S. LEGAL EDUCATION

Columbia Law School, LL.M.

Sam Katz | Corporate and Capital Markets

U.S. BASED EXPERIENCE

Dechert

U.S. LEGAL EDUCATION

New York University School of Law, J.D.

Isaac (Yitzhak) Pasha | Corporate and Capital Markets

U.S. BASED EXPERIENCE

Kirkland & Ellis LLP

U.S. LEGAL EDUCATION

Yale Law School, LL.M.

Inbar Rauchwerger | Mergers & Acquisitions

U.S. BASED EXPERIENCE

Goodwin Procter LLP

U.S. LEGAL EDUCATION

Columbia Law School, LL.M.

Rachel Rhodes | Corporate and Capital Markets

U.S. BASED EXPERIENCE

Fried Frank LLP

Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP

U.S. LEGAL EDUCATION

Columbia Law School, LL.M.

honigman.com/HonigmanLawIsrael

In Israel, divisions rage. In America, they whisper.

In Israel, the choices of one segment of the population regarding matters such as army service, economic engagement and public observance of religion profoundly impact the others, hence the rage. In America, we are less interdependent and can do our own thing, thus the whisper. Yet, while those divisions are less pronounced and raucous, they are there and represent a painfully signi cant lost opportunity for Klal Yisrael.

Jews pray copiously for peace. e nightly request for shalom rav, abundant peace, is a muted and modest hope for a lack of con ict, while the daytime plea of sim shalom ambitiously asks G-d to bless us kulanu k’echad, together as one uni ed whole. e gap between them is the di erence between night and day, between the isolation of darkness and the brilliantly encompassing illumination cast b’or panecha, by the light of G-d’s countenance. It is the di erence between coexistence and unity.

Light enables vision, and vision is essential to unity. As expressed in Mishlei, “B’ein chazon yipara am, v’shomer Torah—ashreihu, in the absence of vision, the nation disintegrates. Fortunate is the one who observes Torah.”1 Individual Torah observance guides our personal lives—“fortunate is the one who observes Torah”—but we need a Torah-guided real-world vision, a chazon illuminated b’or panecha, to bring the nation together. As a broader community we are missing that unifying clear vision and are functioning instead in the darkness, thankfully without raging con ict, but with the inherent incoherence of shalom rav, a fractured peace.

While this expresses itself on many fronts, we will focus on three: Fear, Alienation and Competition.

Growth is a blessing, but it generates fear. at is what happened in Egypt. “ e Children of Israel were fruitful and swarmed, they increased and grew very strong, and the land became lled with them.”2 at phenomenal growth scared the Egyptians, leading them to plot and scheme and ultimately implement bondage and oppression to contain and suppress our growth. at was their reaction to our blessing, and it is perhaps why the Book of Shemot is known start to nish as Sefer HaGeulah, the Book of Redemption, Exodus. While the Book dedicates many chapters to the story of our bondage and su ering, that su ering was a product of the blessing of our growth, a critical component of our maturation and redemption.

Orthodoxy across the world is growing both objectively and relatively. Its numbers are swelling due to a combination of high birth rates and strong retention, and it now constitutes an increasing percentage of the Jewish

population. While some smaller Orthodox communities with limited Jewish infrastructure are struggling to survive, those that have crossed the threshold and o er day schools and kosher pizza are as a rule experiencing substantial growth. is growth is even more dramatic in Israel, where the current and anticipated demographic shi s in the country indicate a dramatically growing Chareidi and Religious Zionist population. is is generating fear.

While it was tting for the Egyptians to be fearful of what could easily become a growing h column of foreigners, Jews should not need to fear other Jews. But they do. Orthodox Jews can be scary. We look di erent, live di erently, and have di erent expectations of ourselves and sometimes of others. We build shuls everywhere to speed to during the week and to walk in crowds to rarely on the sidewalk on Shabbat and yom tov. We build communities and neighborhoods so that we can be close to each other, but inadvertently, we make others feel out of place. It is easy to understand how people can feel that wherever we are, we are taking over. And that is just in America. (See “Can’t We Just Get Along?” on page 23 in this issue.)

And so we end up with Jews fearing other Jews.

In the winter of 1913, Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook and Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld led a delegation of rabbis on a tour of the new settlements in the Shomron and the Galil. At that time, the demographics were shi ing in the opposite direction as the new and more secular Yishuv was growing in numbers and in uence, and it was the religious who were fearful. e mission’s purpose was to bridge the growing divide between the old and the new Yishuvim

In his introduction to the chronicle3 of the trip, Rav Kook writes of what led to that gap. A er stating how some of the leaders of the new Yishuv were exclusively focused on the secular aspects of developing the land and its communities, he notes how the old Yishuv had created their own distance in their interest to build the most rari ed atmosphere possible within their holy cities. “ at innocent and wholesome desire created an ideological and geographic divide between brothers who genuinely needed partnership in every venture and task.”

During the trip, Rabbi Yaakov Moshe Charlop, a student and colleague of Rav Kook, had a conversation late into the night with a watchman in the Emek Yizre’el community of Merchavya. e guard expressed how religiously bene cial it would be for Merchavya if a group of yeshivah students from Yerushalayim would establish a neighboring settlement. Rabbi Charlop responded that those students stay away as they fear being caught in the

settlements’ atmosphere of contempt for religion. “Had you had the foresight to relate more warmly to those dedicated to Torah and mitzvot, we would achieve resolution and a blending of our strengths. e yeshivah students’ feelings of faith and holiness would in uence you, and your courageous and vigorous spirit would enter the hearts of the yeshivah students.”

Jews fear other Jews and keep their distance. At this time of Orthodox growth, we need to facilitate the vision, the chazon, where the Orthodox community is perceived not as a threat but as a growing resource of passionately committed Jews who prioritize both their Judaism and their absolute and unconditional love for each and every other Jew. We will facilitate that vision in others when we build it within Orthodoxy, but thus far we have not.

In the celebrated prophetic vision described as Chazon Yeshayahu, the prophet Yeshayahu describes the failed

society destined for Churban. In the spirit of Mishlei, he expresses on G-d’s behalf how our routine observances our mitzvot, our o erings, our Shabbatot and festivals are insu cient to maintain the nation in the absence of a broader vision that includes an encompassing commitment to the pursuit of security and justice for the most vulnerable.

In describing our failure to properly constitute as a nation, Yeshayahu compares us to the leaders of Sodom and the people of Amorah. While in the vernacular the names of these cities are emblematic of gross immorality, what truly did them in was their utter apathy and complete failure to be caring and charitable. “Behold this was the failure of Sodom, your sister: pride, abundance of bread, and careless ease were hers and her daughters’, and yet she did not strengthen the hand of the poor and needy.”4 is matches the characterization by our Sages of the attitude of Sodom, “what is mine is mine and what is yours is yours.”5 e people

of Sodom wanted to be le alone; the needs of others simply did not register with them. But it did not stop there.

e Talmud6 famously describes how the Sodomites made guests unwelcome, most notably via the “Sodom bed” that needed to t all, that forced those shorter to stretch to size and those too tall to be cut short. is was not just a medieval torture chamber. It tells the common story of a community that would not welcome those who did not t their image of what a resident of their town should look like.

is is a narrow perspective that stubbornly persists, especially as Orthodox numerical and nancial strength have lessened the intra-Orthodox need for allies and partners. Our community is highly segmented, with an utter lack of identi cation with or even mutual awareness between those segments. Tensions are low since we each go about our business as if the others simply do not exist. Each segment has its own world, its Sodom bed, its comfort zone of who it knows, recognizes and invites to the seats at their communal tables.

As we consider our own generational shi s in both religious directions, we ought to ask ourselves what the likelihood is that we would have established a relationship with our own parents, grandparents or greatgrandparents had they been our contemporaries. Would we have greeted someone like them in the street or the supermarket? Would we have shared co ee or Shabbat meals or otherwise created a relationship with them? Would they feel comfortable in our shul or minyan that is designed for one speci c age or religious micro-demographic?

e answer will o en be “no.”

Our lack of a national vision, b’ein chazon, is leaving us alienated from those to our right and to our le such that we are missing the chance to bene t from their energies and to have them bene t from ours. is is an epic lost opportunity for Klal Yisrael.

V’ra’acha v’samach b’libo 7 ose three Hebrew words should be posted on the walls of all our communal o ces.

ey were communicated to Moshe by G-d a er a week of Moshe resisting assumption of the Divine mission of leading the Jews out of Egypt. Our Sages taught that Moshe’s resistance derived from his concern of displacing and overshadowing his older brother Aharon who was then leading the Jews in Egypt.8 G-d became angry with Moshe, noting that rather than Aharon feeling hurt, “he will see you and rejoice in his heart.” Instead of expressing appreciation for Moshe’s humility and sensitivity, Hashem was frustrated that he inserted politics into the dynamics of Jewish leadership, that he assumed that Aharon would be anything other than thrilled that help for the Jewish people was on the way, whomever the messenger.

I received a call from the leader of a campus educational program asking permission to hire away someone who had just joined our team. “Excuse me for what may be a chutzpah, but we both work for the Ribbono Shel Olam, the One Above, and I really think she is more needed in the role I would have for her here.” e direct request was incredibly refreshing, and we were game to entertain it and try to consider objectively where the sought-a er employee could uniquely do more for G-d and for Klal Yisrael, if she would be interested in the other opportunity (she was not.)

at request should not be a chutzpah; it should be a norm. It was inspiringly reminiscent of when Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz sent some of his best and brightest students in Mesivta Torah Vodaath to serve as the initial core of Rabbi Aaron Kotler’s new yeshivah in Lakewood. It is not about us, about growing our institution, claiming organizational credit or seeking personal success. We are all on the same team. We need to rejoice at the e orts and the successes of others. e Jewish people should not be enslaved in Egypt for another week while we work out the politics of who will be the one to lead them out.

e Jewish people are spending a lot of time waiting for us to work out our politics. B’ein chazon, in our limited communal vision, we are all competing for credit, for market share,

for prominence, and for fundraising dollars. Potential partners are viewed as competitors whose success we sometimes see as diminishing our own.9 We need to adopt the kind of vision that sees past that, that understands, appreciates and applauds the added value of being teammates with all those working for the Ribbono Shel Olam.

We are divided, within Orthodoxy and beyond. Division has us view each other as strangers, competitors and monsters. A bit of vision, of chazon, can bring us closer to thinking as a nation, as brothers and sisters, as teammates and partners, and as treasured resources for each other.

Rabbi Simcha Zissel Broyde of Kelm, the master teacher of the Musar movement, posted the following note for his students in anticipation of Rosh Hashanah.

On this day, we have the task of declaring G-d as our King. But when we consider any human kingdom, we understand that it can only be maintained to the extent that the king’s subjects are bound together like one in their service of the king. It is therefore incumbent upon us, as we declare G-d as our King, to make ourselves one and to commit with all our being to the mitzvah of loving our fellow man as ourselves. How can we pray to G-d that all the world bond together as one in His service when we ourselves are not bound together? Each of us can and should look around at our immediate circle, as well as at our neighbors and community, and see ourselves as pieces of a single whole. We can, we should—and so far we don’t. We can do better, and we will.

Notes

1. Mishlei 29:18.

2. Shemot 1:7.

3. Eileh Massei, originally published in 1916, republished by Keren RE”M in 2011.

4. Yechezkel 19:49; see Ramban to Bereishit 19:5.

5. Pirkei Avot 5:10.

6. Sanhedrin 109b.

7. Shemot 4:14.

8. See Rashi to Shemot 4:10.

9. Mori v’Rabi Rabbi Na ali Neuberger was fond of quoting President Eisenhower, who said, “It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.”

At Touro University’s Lander College for Women, you’ll find academic excellence, a commitment to Torah values, and supportive faculty dedicated to helping you reach your goals. Whether it’s a pathway program to one of Touro’s professional schools, admission to an Ivy league graduate school, an internship at a top firm or a job at a fortune 500 company, TOURO TAKES YOU THERE.

lcw.touro.edu

Marian Stoltz Loike, Ph.D., Dean

Marian Stoltz Loike, Ph.D., Dean

As we initiate the season of re ection, atonement and connection to Hashem, we remind ourselves that we are not merely involved in a unidirectional conversation. Engagement with the Divine is a two-way street, in which we are being called. Our Sages note (for example, Pirkei Avot 6:2) that a bat kol, or a Heavenly voice, calls out from Mount Sinai each day, unbeknownst to the Children of Israel. Do we hear it? Are we answering the call? How do we answer that call at the Orthodox Union?

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

Our introduction to the rst of our forefathers, Avraham, begins with the words: “And Hashem said to Avram.” Why did Hashem aim this Divine directive at Avraham in particular? On what grounds did Hashem select Avraham? What of the others who populated that pre-monotheistic universe? e Chiddushei HaRim (Sefat Emet, Lech Lecha 5632 and 5662, based on Bereishit Rabbah 39:1) supplies an answer to this quandary that is as beautiful as it is brilliant, encompassing within it the great challenge of modern man in an increasingly frenzied society: e call of the Almighty went forth for all to hear; only Avraham, however, made the choice to answer that call.

l We ensure that our imprimatur is not merely a stamp but a pledge of quality, of excellence, for over a million products worldwide.

l We elevate over 32,000 teens in spiritually upli ing activities, conversations and communities.

l We create communities of Torah, leadership and service on over seventy college campuses in Canada, the US and Israel.

l We serve over 1,500 individuals with special needs and their families.

l We engage hundreds of thousands in Torah learning, including programming for women leaders and projects for a number of the underserved communities within our ranks.

l We support thousands of American olim in our homeland. And much, much more.

And now in our season of personal goal setting for the new year, our professionals are also setting their sights on goals for the coming year. If we have already accomplished this much, what can we accomplish together in the coming year? What are the questions we can answer? What are the callings containing our names, our potential? We have much to do—and we are just getting started.

Wherever you are in life—college student, new alum, busy professional, empty-nester, recent retiree—what is your calling? We have much to accomplish, all of us, together. e question and the test, then, is to discover our calling; to understand our challenge; to tease out that so , subtle and sometimes soundless voice that beckons us to rise to our potential, and to magnify it into a resounding declaration that both guides and colors our lives. May this be our berachah for the coming year and for many years to come.

“Everyone who wills can hear the inner voice. It is within everyone.”

Mahatma GandhiRabbi Dr. Josh Joseph is executive vice president/chief operating o cer of the OU.

The question and the test, then, is to discover our calling; to understand our challenge; to tease out that soft, subtle and sometimes soundless voice that beckons us to rise to our potential . . .

Your

Yom Tov table isn’t fully set without

With 2023 marking 100 years of OU Kosher, throughout the year, Jewish Action will pro le personalities who played a seminal role in building OU Kosher.

Rabbi Yacov Halevi Lipschutz, my predecessor at OU Kosher from 1977 to 1980, was named for his great-grandfather, the famed secretary of Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor and author of the Zichron Yaakov. He took great pride in his illustrious Lithuanian heritage (Rabbi Moshe Elefant, COO of OU Kosher, once commented to me that Rabbi Yacov Lipschutz was the last true Litvak), and especially in his namesake’s relationship with Rav Yitzchak Elchanan. In his youth, he studied in Torah Vodaas and Beis Medrash Elyon and was known as a real masmid. (His chavrusa was his cousin with the same name as his, who was an author of the Encyclopedia Talmudit and went on to edit manuscripts of important Rishonim for Machon Harry Fischel.)

Reb Yacov was a bona de talmid chacham and an expert in the laws of kashrus, especially shechitah, who authored the critical work Kashruth: A Comprehensive Background and Reference Guide to the Principles of Kashruth. Published in 1988, the book served as an authoritative guide to kashrus—the rst work of its kind. His detailed knowledge of the status of an in nite number of ingredients was just one aspect of his mastery of kashrus He was learned in many other areas and used to send me his handwritten divrei Torah on the parashah, which were ultimately collected into the three volumes of his sefer Ikvei Binyamin. His divrei Torah were always full of

insight, and I enjoyed reading them very much. In addition to his brilliant mind, he also had a poetic soul; in fact, along with writing sefarim, he would compose poetry.

Reb Yacov was a pioneer in many ways. He was the only boy from his Massachusetts hometown of Fall River, where his father served as rav for decades, to study in a yeshivah at the time, and one of the few from the yeshivah to continue his studies in kollel following marriage. He remained in klei kodesh work, delivering a shiur for high school and semichah students at Yeshiva Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch in the Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights, which was home to a large community of German Jewish refugees.

While in Washington Heights, he developed a close bond with Rabbi Joseph Breuer, who headed the institutions of the German Jewish community. Rabbi Breuer in uenced Reb Yacov to undertake serious study of Nach. Once during a conversation, Rabbi Breuer turned to him and said, in his native German, “Uhn vas würde der Novi Yeshayahu dazu sagen—And what would the prophet Yeshayahu say about this?” Reb Yacov took these words to heart. He delved into the poetic words of Yeshayahu’s prophecies and would attempt to analyze situations as he believed the prophets would. His public speeches would invariably center on the eternity and vitality of the Jewish people as they struggled through the exile and inspire people to view themselves as members of an eternal Divine nation, not as mere individuals.

When I came to the OU in 1980, everyone held Reb Yacov in high regard, almost in awe, because of his great integrity, loyalty and expertise. ose who worked with him, people who really knew the kashrus industry, respected him tremendously for his knowledge and his judgment. He also possessed

remarkable yiras Shamayim. Rabbi Elefant described to me an episode that occurred a er Reb Yacov had le the OU, in which there was some remote concern about the kashrus of matzah under his supervision. Reb Yacov was trembling at the possibility that something had gone wrong, and immediately replaced all the matzah in question.

During the years Reb Yacov served at the OU, he traveled and visited plants much more frequently than I do today because the OU was much smaller at the time and had a limited sta . A 1979 New York Times article described the heads of the “big four” kosher organizations at the time, including Rabbi Lipschutz: “ ese are not men to cavil at the prospect of more ight time than becomes a Secretary of State, and it takes more than turbulence alo and intransigence below to discourage them from extending the dominion of kashrut.” On occasion, the New York Times gets it right.

I o en quote what Reb Yacov told me in the name of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik. Rav Soloveitchik said to him that when you see an OU on a product, it testi es to the vitality of the American Jewish community. Reb Yacov’s commitment to the community helped make the OU the trusted symbol it is.

Even though Reb Yacov was an austere Litvak, he had a wonderful sense of humor. He always saw the potential in others, and he was tremendously loyal. When the OU absorbed National Kashrus, the hashgachah he had established a er leaving the OU, he had one rm condition: all the people and the mashgichim who worked with him must keep their jobs. To me, that was emblematic of his commitment and his loyalty.

e signi cant contributions he made to the Jewish community through his great talents and re ned character, and the distinguished family he le behind, are his legacy.

It was 1985 and the then-president of the Orthodox Union Professor Shimon Kwestel requested that I, chairman of the OU Publications Commission at the time, create a magazine that would disseminate and further the values of the organization. Matis Greenblatt and I subsequently met in my home, and a er a few hours of intense discussion, we decided to turn the organization’s seven- or eight-page in-house newsletter, known as Jewish Action, into a full- edged magazine. Matis was to serve as literary editor.

Almost forty years later, re ecting on years of tireless work and e ort, one realizes that without Matis’s contribution—his insight and extraordinary talent—the magazine would never have succeeded. For decades we conferred at least two or three times a week, sometimes daily,

Joel M. Schreiber is chairman emeritus, Jewish Action Committee. This article is adapted from an essay that was originally published in the spring 2014 issue of Jewish Action.

and during those times, I realized the depth of his remarkable talents. We would discuss, deliberate and debate for hours on end.

Matis was a consummate talmid chacham and expert, whether in Talmud, Midrash, Jewish philosophy or machshavah. Be it klezmer or classical music, novels or biographies, Chassidim or Mitnagdim, politics or organizations, Matis had an interest in and a rm knowledge of the subject matter.

Working closely with editor Heidi Tenzer, Charlotte Friedland and Nechama Carmel respectively, Matis brought an intellectual rigor to the publication. Along with the Editorial Committee, he conceptualized many of our celebrated issues, and because

of his personal connections, Jewish Action began featuring some of the most prominent thinkers and rabbis in the Orthodox world, such as Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein and Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks. Jewish Action’s intellectual breadth was due to Matis’s in uence as well. Under his guidance, we published articles covering the range of Orthodox Torah scholarship, from Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook to Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner, from Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik to Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. In our quest to challenge our readership with fresh perspectives and new insights, Matis was a continual source of ideas. His eclectic knowledge and dedication to excellence made working with him both interesting and challenging. His deep faith infused our work with value and importance. Ironically although Matis was practically unknown to the OU administration and o cers, he was the spark that helped create and sustain interest in Jewish Action not only in the formative years but for decades therea er

A er nearly three decades of tireless devotion to the magazine, Matis retired while continuing to serve Jewish Action as literary editor emeritus. We can be certain in the

knowledge that his literary creation will remain an enduring gi to the Jewish public.

On a personal note, Matis’s recent passing leaves a void in my heart that will never be lled. My special relationship with this very special person was a gi that I will always cherish. Chaval al d’avdin v’lo mishtakchin.

It was a criminal conspiracy. e criminals: Matis Greenblatt and Hillel Goldberg. e crime: getting Orthodox Jews who don’t usually read each other, or hear each other or pay attention to each other, to do so. e tools of the crime: Greenblatt’s checkered history, aided and abetted by Goldberg’s own checkered history. e checkered history: Torah study under rebbeim both in and out of the yeshivah world, appreciation of perspectives both in and out of Modern Orthodox communities, and personal connections in both worlds.

For example, when Greenblatt, in 1987, proposed to Goldberg a symposium on musar (“Do We Need a Renewal of Musar?”), no time was spent on evaluating whether this was a good idea. Of course it was a good idea, not just intrinsically, but because it was an area of Torah that no particular segment of the Orthodox Jewish community could claim a monopoly on, or a particular expertise in. By its nature, musar crosses boundaries. So no, time was not spent on evaluating the idea. Immediately, we began tossing out names of potential contributors, a key criterion being their roots in yeshivot that otherwise might not pay attention to each other, their study under rebbeim who might not otherwise read each other.

In truth, Greenblatt was the chief conspirator; Goldberg was the coconspirator. Indeed, Greenblatt’s genius was in gathering around himself many co-conspirators. Another one was Joel Schreiber, chairman of the OU Publications Commission from 1985 to 2004, who insisted on the independence of the magazine’s voice and not only supported diversity of voice, but o ered his own ideas on it. Another one was editor Heidi Tenzer, who was followed by Charlotte Friedland and current editor Nechama Carmel. not only had to edit the consequences of the various literary conspiracies (Greenblatt’s o cial title was “literary editor”), but also had to keep the magazine in balance with other valuable foci.

As the years went on and Greenblatt’s special projects and symposia grew Jewish Action in stature and readership, his crimes multiplied. He tackled many controversial topics. Jewish Action became the go-to publication for many sides, not just one side, of a controversy. When a magazine grows in stature, there are dramatic side bene ts. Surely one of Greenblatt’s many lasting contributions derived from his special link to the late Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, zt”l, which yielded his memorable 1992 piece, “ e Source of Faith Is Faith Itself.” Sum it up this way: Unlike almost all house organs, in Jewish Action many pieces shepherded into print by Rabbi Matis Greenblatt have ended up with a permanent place in the Jewish spiritual rmament.

As I contemplate Matis’s wide perspectives and laser-focused dedication, I regret that no similar conspiracy is ever likely to come my way again. Matis, you cared; Matis, you mastered the art of friendship. Rest in peace, my friend: you did your piece to change the world and heal the breaches.

Rabbi Matis Greenblatt, z”l, was born in 1933 in the Coney Island section of Brooklyn, where he spent his childhood.

He attended Yeshiva of Brighton Beach for elementary school and Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin for high school and post high school beit midrash studies. It was there that he formed a close relationship with the rosh yeshivah, Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner.

Rabbi Greenblatt earned his bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from Brooklyn College. He began working for the federal Social Security Administration (SSA) at age twenty-five when he married Audrey (Chana) Shapiro, a Stern College student from Kansas City. He spent his early married life in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, and later moved to Monsey.

While still working at the SSA, he was recruited to develop Jewish Action into a full-fledged magazine and re-launched the publication. He retired from the SSA at fiftythree and devoted more of his time to Jewish Action. In 2000, Rabbi Greenblatt realized his longtime dream of making aliyah, and he spent his remaining years in Bayit Vegan, Jerusalem. He is survived by six children, thirty-one grandchildren and many greatgrandchildren.

King David in Psalm 24 asks, “Mi Ya’aleh . . . who will ascend to G-d’s holy place . . . . ?” And he answers:

“

Neki kapayim u’var levav, the clean of hands and the pure of heart, asher lo nasa la’shav nafshi, who did not carry My soul in vain.” e meaning of neki kapayim is fairly clear: a “clean hand” takes not what is not his, but instead gives to others and bestows blessings; bar levav, “pure of heart,” means one who bears no grudge, has no malice or envy or hatred. But the meaning of “did not carry My soul in vain” is not readily apparent.

In the life of my friend Rabbi Matis Greenblatt, the meaning becomes apparent. For at birth, every person is granted a soul and is bidden to improve it, heighten its spirituality and utilize it to serve G-d and to help others. If during a person’s lifetime he does not enhance his spirituality or increase his service of G-d and man—does not, in a word, cleanse and purify his G-d-given soul but instead returns it to its Maker unimproved and unre ned—that means that the soul given to him at birth was carried by him in vain, la’shav, for he did nothing with it. e person who will ascend to G-d’s holy place is the one who during his lifetime devoted himself to loyal service of G-d, to study of Torah, to spiritual pursuits, and to doing chesed, kindness.

It is these words—lo nasa la’shav nafshi—that portray my friend of many years. Having learned with him as a chavrusa for many years, I recognized his brilliant mind and intellectual rigor. He loved learning, reveled in its depths, and was a veritable bibliographer: give him just the title of any classic sefer Nimukei Yosef, Rif, Rashba, Tosafos Rid—and he would immediately know its author and when it was published. Beyond this, having studied in Mesivta Chaim Berlin under the legendary Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner, he absorbed his rebbi’s ability to perceive, to analyze, to prize integrity and to give no quarter to intellectual dishonesty. But above all else, in addition to his perceptive editing and ne writing, Rav Matis was a mentsch, a sensitive human being, kind and considerate and caring despite the fact that his was not an easy life. He and his devoted wife—whose care and concern for him in his last years was without parallel—overcame many challenges even before his nal, lengthy illness. Notwithstanding all this, his goodness remained unchanged.

Who will ascend to G-d’s holy place? People like Rav Matis Greenblatt. He surely earned a rich Olam Haba, taking with him his clean, unsullied hands (as a Kohen, he gave thousands of blessings), his pure heart and especially his soul, which he re ned and enhanced and certainly did not carry in vain. He is sorely missed. May his soul be bound up in the bond of eternal life.

Unfortunately, we occasionally hear about confict and tension when Orthodox Jews begin moving into a new community. While the confict often centers on zoning issues or the introduction of an eruv, the battles tend to mask emotions simmering beneath the surface: fear of the unknown and anxiety about the future. No doubt antisemitism exists, but in many cases, the tension dissipates when caring, concerned people—on both sides—get involved. In the stories that follow, that is exactly what happened.

When con ict and tension began to brew in Ocean County, a core group of Orthodox activists set out to change the situation.

By Sam Ellenbogen and Michael Waldner

As

By Sam Ellenbogen and Michael Waldner

As

told to

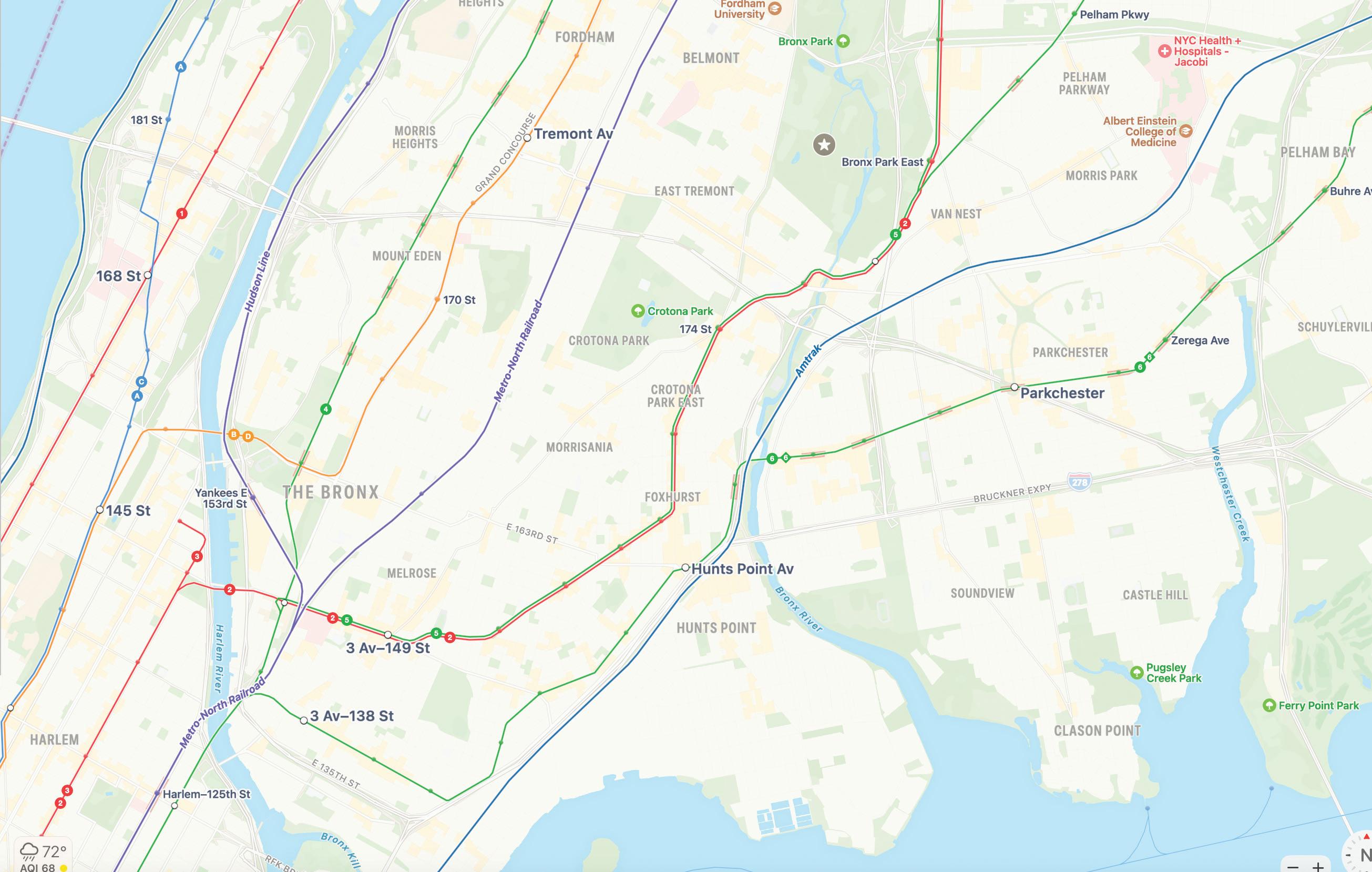

Nechama CarmelWhen we rst moved here some years ago, blackand-white yard signs adorned front lawns, declaring “Don’t sell! Toms River Strong!” e signs were mostly in response to aggressive real estate solicitors; non-Jewish families had gotten visits from several agents on the lookout for homes for Orthodox families seeking to move into the area. Rabbi Moshe Gourarie

was operating the Chabad Jewish Center from his house, a quiet shul that attracted a small crowd. e township was giving him a hard time since the zoning ordinance banned places of prayer in a residential zone. A meeting was held in the town hall over the issue, and 2,000 non-Jewish residents showed up to oppose the shul. Tensions were running high. e Toms River Jewish Community Council (TRJCC) was born out of necessity; it was a reactionary measure to the tension and con ict. A core group of guys—eleven local businessmen—decided to come together to try and promote dialogue and conversation. (Our o ce is my [Sam’s] dining room.) We reached out to the mayor, county o cials, the sheri , the local police chief, the re chief and local interfaith leaders.

We wanted there to be a place for people to express discontent and to air questions. We let everyone know: if there are problems, come to us.

In the years since we started, we’ve spent thousands of hours engaging with residents and community leaders. We’ve become the go-to place for addressing communal issues. Residents

turn to us, asking about the eruv. Or on Sukkos, for example, neighbors call asking, “What’s with all the huts?” Nine out of ten times, the calls we receive concern perception issues.

People have valid questions. Many of them never encountered an Orthodox Jew before. When Orthodox families rst started moving in, much of the tension was simply due to fear of the unknown. Residents didn’t want Toms River turning into crowded Lakewood. But we didn’t want that either. We moved here precisely because of the quality of life; we, too, wanted a quiet, serene community. Once we helped them realized that, the hate signs came down. We eld calls all day long. Much of the work we do is education. For example, we got a call from the head of local code enforcement. In Toms River, one is only permitted to park on the street or in a driveway. One Orthodox Jewish family parked two cars side by side in their driveway, causing one of the cars to be partially parked on the lawn. In a town where residents take great pride in their manicured lawns, this understandably upset some neighbors. One neighbor called code enforcement to report the violation. I called the

ordinance against parking on the lawn. He was simply unaware of it.

When a new family moves here, we try to educate them about the community standards: you can’t leave bikes out overnight; you need to take your garbage cans in; you have to properly maintain your lawn and property. Moving from the city to suburbia requires an adjustment.

ere needs to be open-mindedness on all sides and a willingness to have a conversation. We have found that the only way to have dialogue is to engage in dialogue.

On anksgiving we brought food to the police department and to the volunteer re ghters to express our gratitude for all that they do. Recently, we got a call from someone interested in donating a signi cant amount of toys. We could have chosen to donate the toys to a Jewish children’s organization. But we decided to make it a gi for everyone. We reached out to the police chief and set up a date for a free toy drive. e Toms River Jewish Community Council, in conjunction with the local Police Foundation, will be distributing toys to the community’s

are one community. When a problem arises, we try to jump on it immediately. We can’t a ord to wait. is is a bit of a problem as all of us are businessmen trying to run our businesses during the day, while also making sure we are available. Since elding the calls has become a full-time job, we are in the process of hiring our rst administrator. As the community continues to grow, we are committed to ensuring that we remain accessible and responsive.

Are there issues? Yes. Is there antisemitism? Yes, antisemitism does exist, but we have dramatically changed the situation in our community. Overall, in Toms River, we now have a great relationship with our neighbors. Residents are welcoming and understanding. We’ve come a long way. ese days you would be hardpressed to nd a “Toms River Strong” sign anywhere.

As told to Steve Lipman and Leah R. Lightman

Afew years ago, when we moved from Boro Park to Toms River to be closer to our children and grandchildren, the Rise Up Ocean County (RUOC) movement was raging. e people behind RUOC felt threatened by the growth of the Orthodox Jewish populations of Lakewood and the surrounding communities. Jews were purchasing homes and moving to Toms River in increasing numbers. e nature of the area was changing. is was a year or two before the creation of the Toms River Jewish Community Council.

e local non-Jews and secular Jews feared many things, including the erosion of the tax base due to the potential conversion of Orthodox homes into shuls. ey were also concerned about the brain drain on the public school system as the in ux of Orthodox neighbors diminished the local public school student body. Additionally, the Orthodox Jewish community members’ request for bus

funding for their students was perceived as a violation of church and state.

And there was the social issue— they were simply not used to seeing Orthodox Jews walking the streets on Shabbos.

Locals organized to block the way for Orthodox Jews to move in, and began to make things more di cult for us. ey did not like the rapid changes

taking place. ere was friction. ere was tension. You could feel it.

Most of the Orthodox families moving in didn’t know how to bridge the gap with the neighbors. I saw the need to create bonds of friendship, and believed that if something was not done, we were headed to a bad place. A er sharing my concerns with Rabbi Michel Twerski of Milwaukee, he urged me to take action.

Over time, I came to develop a connection with a non-Orthodox Jew who is proud of his Jewishness and is a mover and shaker in Toms River. Eventually we had lunch and he agreed to set up a meeting with Jewish representatives of the community and some of Toms River’s local political gures. A er much e ort, our rst meeting was at a local Starbucks.

Uncomfortable is an understatement for describing the initial moments of that meeting. It wasn’t warm and fuzzy at rst. “Gentlemen,” we began, “do you

think we really have horns? What are you afraid of? at we are going to tear down the houses and construct multidwelling units on every property? at’s not why we’ve chosen to live here. We are family people just like you. We have chosen to live in Toms River since we are seeking quality of life as you are. Let’s all step back, take a collective breath and realize that we have much in common.”

By focusing on shared values and goals, we began to break down barriers. By the time that meeting came to an end, we all saw that we could work together: what united us was far greater than what divided us. Also, we were prepared to give to the community. People want to work with givers, not takers. So we rolled up our sleeves and began collaborating on civic matters, bussing issues, political campaigns and whatever else was needed. Once the Toms River Jewish Community Council came along, the situation improved even more.

Of course, the garden is more about growing community than about growing any specifc vegetables or fowers. Meeting face to face is a great way to build bridges and foster relations.Jewish and non-Jewish children planting together at the grand opening of the Common Grounds community garden in Lakewood in 2021. e garden is a project of One Ocean County, dedicated to fostering dialogue and positive interaction between the region’s Orthodox Jewish community and their neighbors. Courtesy of the Lakewood Scoop/Colin Lewis Rabbi Shabsey Gartner, a resident of Toms River and a veteran community activist, is the founder of the Living Kiddush Hashem Foundation, dedicated to raising awareness of the paramount importance of the mitzvah of kiddush Hashem (livingkiddushhashem.org/). Steve Lipman and Leah R. Lightman are frequent contributors to Jewish Action.

e Jewish community has developed strong ties to the police chief and the sheri in Toms River. A few months ago, the community held a hachnasas sefer Torah. We had ten police and sheri cars escorting us through a major thoroughfare. ey were amazingly supportive. Four or ve years earlier, we would not have been allowed to do it.

In the years since we’ve been able to overcome the tension and con ict, I have learned a few things. Being aware of neighborhood concerns is a rst priority in avoiding confrontation. Most people are clearly afraid that Orthodox Jews will simply overrun their lifestyle without consideration for things they hold dear. Any change frightens people. It’s important to realize that this is a legitimate fear people have.

ere is no one recipe for success in how an Orthodox community can grow and migrate to new areas, but awareness and proactively organized initiatives can help each community as it grows. What works is very simple: Create a vaad or community committee to be responsible for outreach—to political parties, the police department, the re department, the Chamber of Commerce. We take the initiative to deliver sandwiches and treats to public servants, such as the police, EMS and re departments on anksgiving and holidays. People notice. It creates a tremendous amount of goodwill.

Participate in local events. All townships have open meetings on a regular basis. Community representatives should attend these meetings consistently and introduce themselves, showing participation in local matters and a willingness to live side by side.

Express concern for local legislation and politics by showing activism in elections. is has huge rami cations, especially in local primaries. We do make a di erence.

Support the food banks and the homeless in your community. It shows we care. It’s our obligation to engage in community outreach.

Be gracious. When we drive,

we can choose to drive safely or recklessly; we can choose to either make a kiddush Hashem or a chillul Hashem. How we behave in public contributes to whether people will accept us or reject us.

Share common goals. Reform or Conservative Jews may feel confronted or excluded when Orthodox Jews move into their neighborhoods. We should make them aware of our common goals as residents.

By working with our neighbors, unbelievably good things have happened in Toms River.

Tova Herskovitz

As told to Steve Lipman

Afew years ago in Ocean County, home of Lakewood and other rapidly expanding Orthodox Jewish communities, there was a lot of misunderstanding and stereotyping with regard to the Orthodox community. Having studied community dialogue while going for my master’s in social work, I wondered if I might be able to help with building bridges.

I reached out to my peers who are engaged in the outside world and are civic-minded like myself. In 2019, we founded One Ocean County (oneoceancounty.com), a nonpro t organization to bridge the divide and foster dialogue. We do this by hosting events, educational programs and other activities that bring together diverse groups of participants.

When we started, people in the frum community were nervous— many said things like, “it’s fruitless”; it will be an invitation to more scrutiny”; “maybe the problems will just go away.” But we persevered.

Initially, we met with local reporters and held focus groups where we discussed common misconceptions about our community. Many of the local people just didn’t know Orthodox people. We tried to educate—we touched on everything from what we read to how we dress to where we live, shop and play. It was a great way to break the mystique and invite people into our culture. We

By Colin Lewis As toldto

Steve LipmanIn Ocean County, we are seeing unprecedented growth of the Orthodox Jewish community. I watched the yeshivah, Beth Medrash Govoha, grow.

I like the concept of community outreach. The Toms River Jewish Community Council asked me to introduce them to some of the pastors in the community so we could build bridges between ethnic groups.

A couple of friends along with me and an Orthodox Jew formed Love Thy Neighbor USA. [Love Thy Neighbor USA is a grassroots group of activists who embrace community values and work with people and organizations to improve and strengthen relationships between one another, irrelevant of race, religion, color or creed.] One year we hosted a Super Bowl party for the homeless at Urban Air, a recreational place for youth. At least 100 people came. The room was filled with hot food, clothing, hygienic supplies and medical equipment for the homeless.

Love Thy Neighbor has grown; this will be our fourth year. It breaks down the negativity and the stereotypes when people see that the Orthodox community cares about social issues and about its neighbors.

It’s a learning experience for both communities.

Browse through thousands of mouthwatering recipes, explore tips for freezing ahead, discover a brilliant honey cake hack, and download a printable Simanim chart!

Kosher.com

learned that there needed to be a place where people could interact in a positive way and share common ground.

Our rst project that was open to the public was in 2019, before Covid. It was a challah bake held in the ballroom of a local hotel. e idea came from an African American community activist who had heard about a challah bake on the Jersey Shore. We didn’t think people would be interested in making challah, but we posted the event on Facebook and had yers distributed at city council meetings and in downtown Lakewood. Everyone told their friends about it, and local pastors told their congregants about it.

We ended up with 120 women, 80 percent were non-Jews—public school teachers, doctors and nurses. Some women spoke only Spanish; we had a translator on hand. e event was kosher and free of charge; Toms River resident Scott (Shabsey) Gartner sponsored it in honor of his wife Jessica’s birthday.

In the crowded ballroom, women gathered at round tables laden high with ingredients. Each participant received an apron that said “Knead Kindness,” the night’s theme. At every table, one or two Orthodox women led a demonstration on making challah while explaining what challah means to her. We didn’t lean too heavily on the religious aspect of challah. e women went through the steps together—kneading the dough, braiding it, et cetera. We didn’t actually bake the challahs there; the participants took their ready-to-bake challah home with them.

e women had a fabulous time. It was a very fun, relaxed atmosphere. For us, this was the rst step to see if it was possible to bring people together. People asked when the next one would be. ey wanted to see each other again. Unfortunately, Covid put

everything on hold, although we did organize a virtual challah bake during Covid. Subsequently, we had a cra s night at a local library.

Another project of ours is the Lakewood-based “Common Grounds” community garden, where we grow owers and vegetables. Lakewood Mayor Raymond Coles was an early supporter of this initiative. Lakewood Township donated a seventy-byy-foot piece of township-owned elds and gave us access to town water at no charge. We also launched a fundraising campaign, which brought in over $10,000, most of it from local businesses, to help pay for an irrigation system. e Lakewood Police Department donated funds, and a local group for African-American youth helped build the ower beds and plant the various vegetables and herbs. Of course, the garden is more about growing community than about growing any speci c vegetables or owers. Meeting face to face is a great way to build bridges and foster relations.

In addition to the community garden and #KneadKindness, we organize Super Soul Sundays and Super Bowl parties for the homeless population. We

also work with local media, including the Asbury Park Press, to educate people and create awareness of the diversity in Ocean County. In addition, One Ocean County holds tech meetups for young tech enthusiasts in the area. e work of One Ocean County was recently recognized by the Jewish Federation of Ocean County. What have we learned? at people are genuinely interested in learning about our community. We just have to take the rst steps to reach out.

As told to Merri Ukraincik

Imoved to Merion, Pennsylvania, about twenty years ago, when I was newly religious and recently retired. I got involved in community projects from the beginning, and I was the logical point person when we launched the e ort to build a new mikvah in 2010; because of my background in construction, I already knew the town’s leadership.

e landscape in Merion has shi ed dramatically over the years. ere was a time when the deeds to some of the houses did not permit sale to a Jew. Now, most homes on the market are bought by a frum Jewish family. Our plan to replace the original mikvah located in the basement of our elementary school—with a modern facility on another property in town was one more sign of our increasing communal presence here.

With all our growth, however, we are still a relatively small kehillah, not really on anyone’s radar, so we have never faced staunch local opposition. But Orthodox Jews are visible. I attribute our continued success as a community in Merion to the sensitive

way we have gone about meeting our needs, being mindful of our neighbors as we expand.

For example, we have generally taken a civic-focused approach here. We have members on the boards of the public library and the re department. Several others serve as volunteer re ghters. We participate in the annual July 4th parade. Our rabbis give convocations at public events, and we attend them. It’s a healthy way for us to live side by side in one neighborhood.

A er we identi ed a suitable property for the new mikvah, an eyesore we wanted to convert from residential to commercial use, we proceeded carefully to gain public support, reaching out to all the neighbors and to Merion’s residential clubs. We were also sure to do whatever the zoning board requested. We used local professionals for the project and talked to everyone the township asked us to—and we listened to what they had to say.

ough all of us are busy, I made the time to contact anyone who raised their hands at a zoning meeting with a question. I met with them one on one to assuage concerns, or to explain

what a mikvah is and why it is essential to our lives as a community of faith. We approached the Conservative synagogues as well. ese conversations helped us to both garner support for the mikvah and ensure ongoing shalom bayit with our neighbors. Personal connections removed the few barriers of resistance we faced. An artist whose home is right next to the mikvah has a secluded yard with trellises and a pool. He feared losing his privacy if we were to add a proposed second story onto the mikvah building. e zoning board rejected the plan anyway, but our investment of time in listening to him and responding to his speci c concerns ultimately made him the number-one supporter of the project.

e process of constructing the mikvah gave us the opportunity to build many important relationships with Merion residents of all backgrounds, and it remains important to us to preserve and strengthen them going forward.

We invited everyone in town to the Chanukat Habayit to demonstrate our appreciation for their support as we celebrated this milestone.

One of the keys to our success in growing a frum community responsibly has been remembering that we are coming in and asking something of an existing neighborhood. We are deferential and respectful, and we know to compromise where we can. But mostly, we go the extra mile to communicate person to person. In Merion, it’s made all the di erence.

Outremont, an a uent, picturesque residential borough of Montreal, Quebec, is a tale of two very di erent communities. Most residents of Outremont are among the city’s nonJewish, French-speaking cultural elite. It is also home to Montreal’s largest Yiddish-speaking Chassidic population, which numbers several thousand.

ere has been tension between the two communities for some three decades. But things have shi ed in recent years. For example, the Outremont Borough Council served sufganiyot from a local kosher bakery at its monthly meeting one Chanukah. e fact that a Jewish holiday was publicly acknowledged at a council meeting was a momentous event, explained Mindy Pollak, a member of the Vizhnitz Chassidic sect who has served on the council since 2013. (To the best of her knowledge, she is the rst Chassidic woman outside of Israel ever elected to political o ce.)

ere have been other developments

as well. Several years ago, the borough’s annual spring fair—usually held only on Saturday—was extended into Sunday, making it possible for Chassidim to participate. eir previous requests for an extension had been denied.

“

ere’s de nitely a change,” Pollak was quoted as saying in the Canadian Jewish News. “ e council plays a huge role in setting the tone of what goes on. Past councils have sort of encouraged the con ict.”

During Covid, the Chassidim were compelled to make minyanim on their porches and pray outdoors. Surprisingly, some of the non-Jewish neighbors began to really enjoy the chanting of the prayers.“It was such a beautiful thing,” one neighbor was quoted as saying on the North Americana podcast, “and because the community keeps itself fairly sequestered. . . . A lot of people were touched by the intimacy of it . . . seeing into the sacred rituals of a community that is closed to you. . . .”

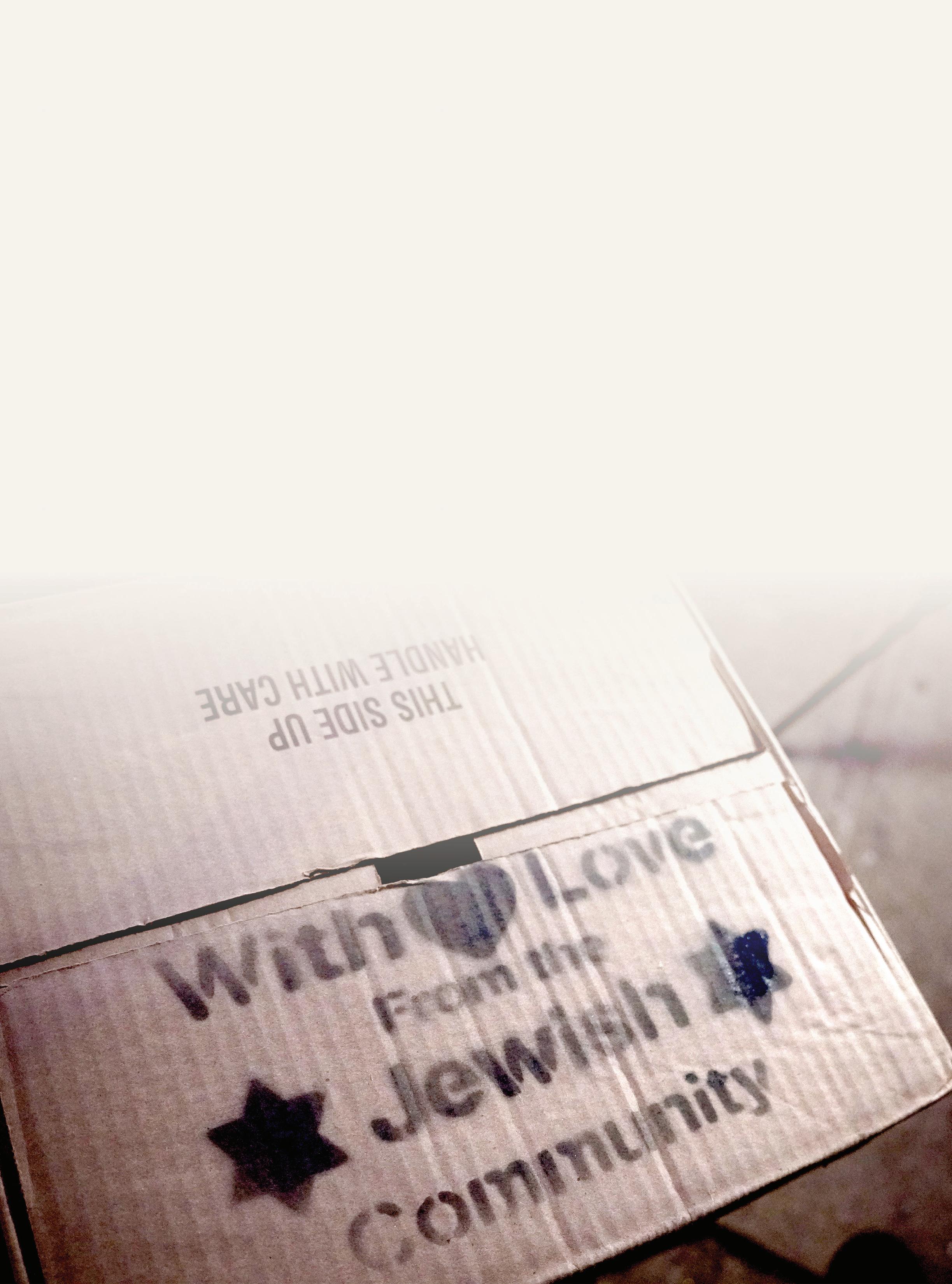

Grateful for the support, the Chassidim brought over bakery goods

to their neighbors with a note thanking them for their “patience during these hard times” and apologizing for the inconvenience they may have caused by praying on their porches three times a day.

e Chassidim have made other e orts to foster better relations as well.

e local branch of Hatzoloh responds to the medical emergencies of Jews and non-Jews alike and oversees the rst-aid tent at community-wide events. And when Belzer Grand Rabbi Yissochar Dov Rokeach made a rare visit from Israel in 2018, the Chassidim placed letters in the mailboxes of Outremont’s non-Jewish residents explaining the importance of the visit and providing advance notice about crowds and other concerns.

A erward, they placed a full-page ad in a local paper to thank their “dear neighbors.” Finding constructive ways to deal with potential con ict has helped create a more positive, harmonious atmosphere in Outremont.

I attribute our continued success as a community in Merion to the sensitive way we have gone about meeting our needs, being mindful of our neighbors as we expand.

With the growing threat of a war with Hezbollah, we can’t ensure this Rosh HaShanah will usher in a peaceful year. But with a new campaign to add 300 urgently needed ambulances to MDA’s fleet, we can save lives no matter what 5784 brings.

With the growing threat of a war with Hezbollah, we can’t ensure this Rosh HaShanah will usher in a peaceful year. But with a new campaign to add 300 urgently needed ambulances to MDA’s fleet, we can save lives no matter what 5784 brings.

Make a donation today or contact us about how you, your family, or synagogue provide the ambulances MDA will need.

With the growing threat of a war with Hezbollah, we can’t ensure this Rosh HaShanah will usher in a peaceful year. But with a new campaign to add 300 urgently needed ambulances to MDA’s fleet, we can save lives no matter what 5784 brings.

With the growing threat of a war with Hezbollah, we can’t ensure this Rosh HaShanah will usher in a peaceful year. But with a new campaign to add 300 urgently needed ambulances to MDA’s fleet, we can save lives no matter what 5784 brings.

Visit afmda.org/give or call 866.632.2763.

Make a donation today or contact us about how you, your family, or synagogue can provide the ambulances MDA will need.

Visit afmda.org/give or call 866.632.2763.

Make a donation today or contact us about how you, your family, or synagogue can provide the ambulances MDA will need.

Make a donation today or contact us about how you, your family, or synagogue can provide the ambulances MDA will need.

Visit afmda.org/give or call 866.632.2763.

Visit afmda.org/give or call 866.632.2763.

As Israelis rejoice in the sound of the shofar, we’re also preparing for the wail of the siren.

As Israelis rejoice in the sound of the shofar, we’re also preparing for the wail of the siren.

As Israelis rejoice in the sound of the shofar, we’re also preparing for the wail of the siren.

As Israelis rejoice in the sound of the shofar, we’re also preparing for the wail of the siren.By Mindy Pollak As told to Merri Ukraincik

We [Chassidic Jews] make up about 25 percent of the neighborhood. Our separate worldviews, lifestyles and appearance have all made for a tenuous coexistence between us and the local non-Jewish population.