Dear Friends,

As I take shelter in my home in the heart of a Wisconsin winter (IT’S ZERO DEGREES), and write this letter, I have immense gratitude. This journey of conceptualizing, curating and bringing Mother Nature vs. Mother Culture to life has been truly special. What started as an idea, inspired by my favorite book “Ishmael” by Daniel Quinn, has grown into a powerful collection of stories, images and insights that I am proud and excited to share with you.

This magazine examines the duality of two forces that shape our world. “Mother Nature,” the balanced ecosystem that has nurtured life for millennia, and “Mother Culture,” the constructed narratives that guide and often dominate our daily lives. We explore the profound tension between these two entities, seeking to illuminate the stories that connect, divide and define us as humans.

I owe a great deal of appreciation to the talented individuals who contributed their time and passion to this idea. I want to recognize my original Align Magazine team: Natalie, Anna, Juliet, Will, Mika, Maura, Lindsey, Harper and Abigail. I also want to thank the Align executive board for connecting me with these very talented individuals. Without these people, this magazine never could’ve happened.

I also want to extend a huge thanks to the new incredible team of writers, designers and copy editors who made this magazine possible. It was very meaningful to me to bring together colleagues from several facets of my life including the University of Oregon, Yellowstone, and of course, my brother. Your dedication and efforts, fresh ideas and excitement about this idea have elevated this project into something truly special. I am humbled and honored to have worked alongside such a talented and passionate group.

Abigail and Natalie deserve an additional shout out as each served a significant role in this project. Natalie in the initial Align phase, and Abigail in the creation of this magazine.

Finally, I want to thank every reader, supporter, friend and family member of mine that has shown support for this endeavor. Your curiosity and engagement have been a driving force, motivating us to dive deeper and produce the best possible product. Our goal was not simply to create a magazine, but to spark a conversation. I am excited to share it and engage in that conversation with all of you.

It is with great pride and excitement that I present Mother Nature vs. Mother Culture. A project that we have put our heart and soul into. I could not be happier with the final product. May it evoke thought, conversation and connection as we navigate the delicate balance between two forces that define our world.

Cheers,

Jack Whayland | Editor-in-Chief

February of 2025 has arrived. We find ourselves in a landscape defined by tension, between left and right, progress and preservation, consumption and conservation, humanity and the natural world. In the next 30 pages, “Mother Nature vs Mother Culture” addresses this tension and emerges as a space for exploration, reflection and dialogue. Inspired by Daniel Quinn’s novel “Ishmael,” this magazine dives into the duality of two forces that shape our existence: Mother Nature, the timeless, interconnected systems that sustain life, and Mother Culture, the societal narratives that often prioritize human dominance over ecological harmony. Through a blend of experimental writing, and expressive photography, we invite you to question the stories you’ve been told about our place in the world and to imagine new ways of being that honor both the Earth and our shared humanity.

This magazine serves as a call to action, inviting readers and collaborators to navigate the delicate balance between civilization and the natural world, reminding us that we are not separate from nature, but deeply embedded in it. Whether we find ourselves living in the tallest skyscrapers in New York City or the smallest cabins in the remote wilderness, our lives are shaped by the interplay of ecological systems and cultural constructs. This magazine seeks to illuminate that interplay with various themes including: Anthropocentrism vs Ecocentrism: The tension between human-centered worldviews and naturecentered ethics; Rewilding the Mind: Rediscovering our primal connections to the Earth and rethinking cultural myths of human superiority; The Paradox of Progress: The double-edged sword of technological advancement and its impact on the planet; Interconnectedness: The profound interdependence between humans, animals, and the environment; Self-Imprisonment: The literal

These ideas unfold through a range of creative expression, including personal narratives, research-driven essays, poetic reflections and visual storytelling. At the heart of this exploration is the distinction Quinn presents in “Ishmael” between two ways of living: the “Takers,” who exploit resources and drive environmental destruction, and the “Leavers,” who live in harmony with the natural world.

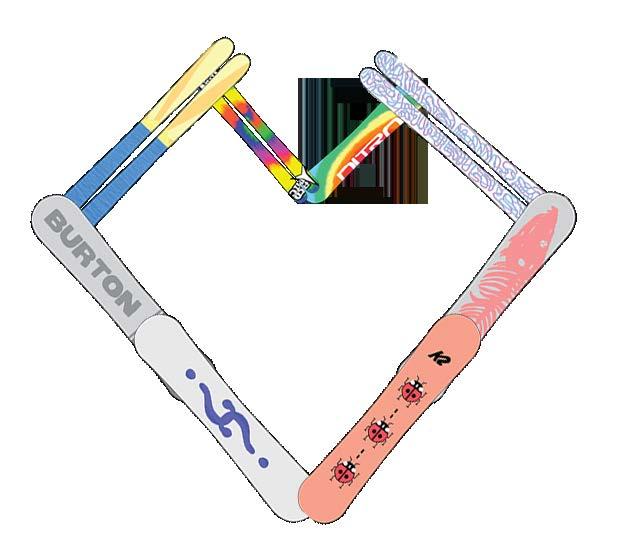

The pieces in this issue take readers from the rugged solitude of the Pacific Crest Trail to the fleeting luxury of modern ski culture, from the ever-moving state of vanlife to the grounding presence of the Willamette River. We explore the myth of American freedom, the tension between environmental responsibility and human innovation, the lasting imprint of family and place and the profound connections forged through travel and cultural exchange. Together these stories paint a picture of a world in motion: A world where the choices we make today will define the future of both our planet and our species.

As you turn these pages, we hope you’ll find inspiration, insight and a renewed sense of purpose. We ask you to take a moment and pause, and truly reflect on our harmony with nature, not as its rulers, but as its partners, fostering a balance where humanity and the natural world thrive as one.

Welcome to Jetty Media; a hub for bold, imaginative digital projects. A place to anchor innovation and launch narratives.

Here at Jetty, we believe in the power of leveraging collaboration, curiosity, creativity, and storytelling in order to challenge perspectives and inspire new ways of thinking. What began as a college collaboration has grown into a thriving creative space, producing visually striking and thought-provoking work.

Iwas eight years old the first time I heard my dad pray. We were in the woods on the back roads that zigzagged through the forest behind our cabin. He made a wrong turn and we found ourselves standing on a carpet of moss and ferns. The trail was lost in the underbrush. My dad stood there. His face was upturned to the patches of sky between the trees, pleading out loud to the empty forest, begging God to guide us home. I didn’t understand at the time who he was talking to, but his desperation scared me. The vast, quiet forest scared me.

The next time we were lost in the woods together I was 21 years old, and I wasn’t afraid. I was doing a portion of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) with my dad as he hiked from our home town Bend, Oregon to the Canadian border. It was early July, and the snow hadn’t quite melted, so the ground was seldom in sight. We saw the trail in glimpses and pieces — each time it appeared, it dove right back under the snow. We were following nothing more than the patterns in tree clearings, assuming we were on track by how the forest parted in front of us.

When we would venture too far off the trail, I would get an uneasy feeling.

The trees looked the same, the snow felt the same and somehow I could sense I didn’t belong. My dad felt it too, and when that uneasiness began to feel a bit too much like being lost, he didn’t pray to God. Instead he typed a four-letter passcode into his phone and pulled up a GPS app. There was our little blue dot in the middle of an empty green screen. He cursed under his breath and pinched the screen frantically until the trail magically appeared to the left of us and up a few hundred feet.

It’s a strange word — lost. Somewhere along the path of becoming human, we found ourselves unfamiliar with the natural world. The wilderness became a place of spectacle, estrangement and unease. What was once natural became wild, and what should be wild is habit. We surround ourselves with noise and killing machines, but we fear none of it more than the vastness of places not yet touched by destruction.

When the United States national parks were first established, the wilderness was a place of spirituality, a sanctuary seen to be closer to heaven and God. Our most natural surroundings were exotic and sacred. While John Muir fought to protect Hetch Hetchy Valley from being dammed, he wrote about the place as though it had been personally touched by God. The rocks were “godlike,” the landscape gardens were “places of recreation

and worship” and the valley was “one of nature’s rarest and most precious mountain temples.” Hand in hand with Muir, President Theodore Roosevelt rallied for the protection of National Park lands. When he spoke in favor of the preservation of the Grand Canyon, Roosevelt described the natural landscape as a place close to God. He pleaded with the American people to protect the park’s “wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, [and] the great loneliness and beauty of the canyon.’’

I gaze and sketch and bask, oftentimes settling down into dumb admiration without definite hope of ever learning much, yet with the longing, unresting effort that lies at the door of hope.

- John Muir

As the wilderness was sanctified, the hand of civilization was ripped from its fading grasp on the natural world. The very attitudes that sought to worship nature estranged us from it entirely.

On the trail, wilderness ceased to be strange or sacred or grand. It was all around us, and it was tedious and infuriating. Our footsteps fell heavy and our shoes were soaked through to our socks as we shuffled through the sun softened snow. We never stayed on a trail for more than a few minutes,

and there were times I wanted to scream, but mostly I just wanted to laugh at the absurdity of it all. A faint line in the dirt was the only thing determining whether we were lost or found. The trail felt safe, monotonous even, but the woods loomed beyond us in terror. The forest murmured to us, telling its secrets and menacing with far off sounds late in the night.

I lay in my tent fighting sleep for hours each night — eyes trained to the faint nylon ceiling above me, ears pricked, muscles clenched. As I listen to the soft rustle of the wind, my mind conjures the sound of an intruder’s footsteps, and the distant murmur of a stream takes on the eerie tone of a menacing whisper. But when day would break, golden light and soft shadows made me forget the fear. The forest returned to its happy place in my mind and all which lurked under the cover of night would become wild imagination.

Wilderness explorers and writers of the early American civilizations have described encounters with nature as those of terror. American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow paints a picture of wonder and fear in the presence of wilderness in his poem “The Prelude.” He describes wind as thwarting, bewildered and forlorn; he speaks of cliffs as if they could talk; he uses the words tumult and darkness to describe the landscape; and yet, he refers to this place as the region of the heavens.

I too feel that fear and wonder. I feel the edges of the forest begging me to become lost within, the river taunting me with its magnetic, roaring pull. I shudder with rush and horror at the peak of a mountain, and I feel perilously small when the land unfolds beyond me, but I am not truly afraid. I am calmed by my helplessness in the unharnessed strength of the

wilderness. Teetering between danger and my own mundane existence, always a safe distance from the edge of the cliff.

But I am no pioneer. I am not the first to find comfort in the vastness of the wilderness; to be submissive to its wonder. Sitting atop North Dome in Yosemite, John Muir wrote, “I gaze and sketch and bask, oftentimes settling down into dumb admiration without definite hope of ever learning much, yet with the longing, unresting effort that lies at the door of hope.” He humbled himself in the presence of nature as one would before God, describing himself as “eager to offer self-denial and renunciation with eternal toil to learn any lesson in the divine manuscript.”

The cunning of nature has been poked and prodded, but there are still too few words to harness its peculiarities. Henry David Thoreau once said that “nature is full of genius, full of the divinity.” He likened the wilderness to a form of art — “the art of god.”

I see the genius, I see the art, but I do not wish to estrange myself from the wilderness by crediting it to some higher power. I will not attempt to understand it, or label it, or simplify it under one holy explanation. I merely wish to exist in it, and within it, I feel peace.

I had agreed to go on the PCT trip as an escape. I had been juggling too much at the time and the to-do lists,

emails and expectations had stacked up like blankets pulled over my face, suffocating me and blotting out the light. I wanted to be untied for a few days — unbothered, unaccountable, unreachable. But the only thing I felt the first day was annoyed. “This is not relaxing,” I grumbled as I swatted away mosquitoes and stumbled over the web of fallen trees congesting the already confusing trail.

Walking 15 miles a day through deadfall and snow while wearing a 30-pound backpack is not relaxing. Eating meals out of plastic bags and sleeping on the ground is not relaxing. This I should have known. I had worked up a grand picture in my head — images of adventure, beauty and grit. But as I trudged through a carcass of burnt forest on day one, I just felt resentment.

It wasn’t until the second day that I noticed the silence. There was the whisper of breeze weaving between pine needles, the trickle of snow melt streams, the shuffle of our feet on snow, the small talk. But still, silence. It was the kind of quiet that sneaks up on you. The kind you don’t notice is there

until you really listen. It was not eerie or uncomfortable, it merely existed in the forest with us and was there when we ran out of things to say. It was soft and gentle, not like the nagging buzz of white noise in an empty room.

The moment I left the trail I missed the quiet. The second my feet found pavement, it was as if they had never left. The noise and blankets were back and I couldn’t breathe again.

I never understood the appeal of backpacking for days — the lack of stimulation, of warm food and dishes and hot water and rooms with mattresses, walls, carpets and doors that lock. But comfort comes with its costs and on the trail nothing mattered as it did at home. On the trail, I only had to exist — not perfectly or impressively. Not with clean, pretty clothes, or one cup of vegetables a meal. Not with 6 a.m. workouts or 500 words written an hour. On the trail, my clothes were stained in sweat and my hair was matted under my three-times-worn hat. I had spoonfuls of peanut butter for lunch and ate my meals out of a bag with my dirty hands. There was dirt everywhere. On my face. Under my fingernails. It caked my knees, stained my socks and made a gritty paste with my sweat.

I was disgusting and imperfect and so utterly human, but for once, I didn’t care. I didn’t count the things I had gotten done at the end of the day; I didn’t worry that there would be more to do tomorrow. I put one foot in front of the other and ate when I was hungry. I slept when the sun went down and woke up when it rose. I peed in the woods and drank from mountain streams and wore the same shirt for days. I couldn’t remember the last time I had existed so purely for existence sake, and I reveled in it.

When I was younger, it bothered me how much time my family insisted on spending outside. Now, the wilderness is my solace from all which pains me. Whenever my mom catches me in a mood, she tells me to go for a walk, and when something is troubling me, we escape into the mountains together. I have yet to find a problem that couldn’t be solved by being dwarfed in the grandeur of the mountains. I find extreme peace in the realization that I am insignificant, that my footsteps barely make an imprint on this heavily tread upon earth.

I don’t believe nature is sacred or sublime, that it should be conquered or that by doing so one would come closer to God. I think it is something

far more ordinary. It is all around us in ways small and subtle. It is in the birds that wake you with their song, the wilted patch of grass in your backyard. It is in the rain and the cold that we button our jackets and close our doors to shut out. And in a way that is not entirely spiritual, in a way without pews, prayers, or priests, the wilderness has become my church.

When I stepped off the PCT, I had trouble adjusting. It had only been a few days, but I had become attached to a life unattached. I had jumped from one extreme lifestyle to another and I flailed as I tried to catch my balance. But I’ve since found it; the balance.

I don’t need to be miles from civilization to feel nature’s hum bringing me back to myself. I’ve found it in the most mundane tasks, in places that are not entirely natural but have murmurs of the humility felt in the wide open. I feel it as I collect miles under my feet on muddy trails and cracked sidewalks. I feel it when I hear my tires purr against cement, when I watch the open road stretch in front of my handlebars. It’s meditation, it’s serenity, it’s emptiness, it’s celebration. I don’t believe in God, but in this church I worship — the church of the wilderness.

WRITER’S NOTE: Many of the ideas and references in this essay were inspired by William Cronon’s “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” I read this piece several years ago and was struck by the absurdity of romanticizing our natural surroundings. I cannot recommend the article enough.

“There is no one right way to live” (Quinn, 92).

After years of hard work and growth, while at the University of Oregon, I found myself with a bachelor’s degree and a world of possibilities before me. But instead of feeling empowered, the weight of societal expectations and the pressure to immediately “figure it all out” left me feeling paralyzed. What followed was stagnation. I clung to short-term distractions and avoided any real forward movement. It wasn’t until I took a bold step and embraced travelling and vanlife that I found the space to break free from these pressures. I leveraged the simplicity and freedom of nature to reconnect with my true self, rediscover my passions and find the clarity and purpose I had been searching for.

My experience at the University of Oregon was incredible. I learned and honed a plethora of subjects and skills, including photography, creative

writing, environmentalism, leadership and history. I further developed my innate ability to connect with others and made hundreds of life-long memories with dozens of life-long friends. The community that I built in Eugene is something I can cherish with every ounce of my body. I met the ‘Goobers,’ six incredible friends that mean the world to me. I will never forget Playing chess in our game room, driving around dirty Eug(ene) and grabbing Hot Mamas wings, movie nights and talks in just about every corner of that house on 164 West 18th. The culmination of these experiences, and graduating, was a pure moment of euphoria.

What followed shortly after was something much less euphoric; complete and utter panic. What the hell am I going to do next? The immense pressure I felt to instantly have my life together was excruciating and incredibly overwhelming. The expectations were clear: Get a job, climb the ladder, buy a house and never stop moving. But for me, these expectations felt less like a roadmap and more like a prison cell. I trapped myself in a maze of “shoulds” and “musts” with no room to breathe or dream. Societal norms, cultural expectations and the fear of failure built the bars of my prison cell. And for a long time, I didn’t know how to break free.

My response wasn’t admirable. I shriveled up, and took solace in things I knew would bring me short-term fulfillment. I partied, played video games, worked in food service and leaned into my community in Eugene. Deep down, I knew I was avoiding progress. It wasn’t a path I was proud of, but I felt like a scared little kid. Still,

there were bright spots in that year — moments of connection and joy that kept me afloat. My community in Eugene became my lifeline. Whether it was sharing a laugh over a pretentious customer at Sweet Life Patisserie or playing a game of late night chess after closing time with my friend Jose at Hey Neighbor, it reminded me that even in the midst of my confusion, I wasn’t alone. I also leaned heavily into the outdoor activities in Eugene. Hikes to Spencer’s Butte, exploring the Willamette Forest and quick drives to Florence, Oregon’s beaches kept me mentally afloat. Despite these moments of light, it felt as though I’d lost myself in this intricate, terrifying maze of life with everyone around me at the finish line (or heading towards it) laughing their asses off.

I had long aspired to participate in something called “vanlife” –a lifestyle where individuals convert vans into mobile homes, allowing them to live and travel freely. The previous year, I acquired a minivan perfect for doing such a thing. So leading up to the end of my lease, I outfitted my van and bought the necessary supplies to live and thrive in my van. One day, I just left (between you and I, it wasn’t that dramatic). I set out to explore the Pacific Northwest, a place I was proud to call home for the previous five years. It was a fresh start I knew I needed, and I’ll never forget the feeling I had finally driving out of Eugene on Highway 99.

There is enormous pressure on you to take a place in the story your culture is enacting in the world— any place at all.

-Ishmael, Daniel Quinn

I visited Olympic, Cascades, Rainier, Lassen, Crater Lake and Redwood National Parks. As I stood beneath ancient redwoods, I felt a profound sense of reassuring insignificance and belonging. I weaved through breathtaking trails, chewed on wildflowers and bear-hugged a couple of trees, feeling their strength and resilience seep into my body (I was a hippie for a summer give me a break). I even backpacked through the North Cascades, trekking 60 miles and climbing 10,000 feet of elevation in 7 days (thanks Will).

In all of these places, I realized I was not separate from nature, but I was a part of it. I am a part of it. The waterfalls, rainforests and cliff views were not just scenery, they were interconnected ecosystems that bind us all. I swam in the Pacific, and flew down rivers all around the west coast. Hell, I even threw a lake in there every once in a while. Swimming in a cold body of water brings me a sense of peace, joy and groundedness that nothing else does. Don’t get me started on the feeling of driving through a beautiful untouched

landscape, the wind blowing through your hair, maybe even a cigarette in your mouth (oops) with “Fearless” by Pink Floyd playing.

I visited friends that I missed more than I realized, and I saw cities that brought on a unique set of experiences and memories. I truly lived on the road. It was exhilarating. I woke up every day with a new sense of adventure. I could go anywhere and do anything.

A distinct experience in my memory was my second day in Crater Lake. I decided to hike Garfield Peak without looking at the weather. This was a common problem of mine — multifaceted planning isn’t always my forté. About halfway up the peak, it started to rain. Normally, this would be a disappointment, but for whatever goddamn reason, I was mesmerized. The cloud engulfed me as I was hiking through it. I was soaked, freezing and being nearly pushed off the mountain by the wind. But by God was that view breathtaking. Picture an enormous crater carved deep into the earth, cradling one of the deepest lakes in the world and glistening sapphire waters so clear you’d swear it was glass. I’ll never forget the sense of perspective that the hike gave me. Not a single condition was going my way, but I was so happy, so fulfilled by this little old hike. If I can make the most of this, why can’t I make the most of my situations in life? I had learned how to appreciate the good and let it immensely outweigh the bad.

There’s something about sitting by a river, the water rushing without a care in the world, that puts everything into perspective. The towering emerald green trees didn’t care if I had a

401(k). The wind coming through the canyon didn’t give a damn about my resume. Even the rocks, ancient and unchanging, seemed to laugh and whisper, “why are you so worried? Just exist, Jack” And for the first time, I listened. At that moment, I didn’t need to prove anything to anyone. The trees and the wind just were, and in their simple, unshakable existence, they reminded me that I could just be too. The walls of that stupid, invisible cell I’d built started to crumble, replaced by the endless horizons of nature and the infinite possibilities of a life lived on my own terms.

The simplicity of vanlife allowed me to step away from my prison and the noise and pressure of societal expectations. I found clarity in the quiet moments, peace in the chaos of the wilderness and a renewed sense of purpose. By leaving behind the constraints of routine, I was able to break free from the cycle of stagnation and confusion that had plagued me for so long. I learned that the answers I was seeking weren’t found in the hustle to conform or meet expectations, but in the freedom to create my own path and embrace the world as it is; unfiltered, unplanned and full of possibilities.

Much like a river, life ebbs and flows. Much like an ocean, life is vast, deep and mysterious. Much like a creek, life is short and shallow. Much like a pond, life can be still and mundane — easy to get lost in the murkiness. And much like a waterfall, life is stunning. It is loud and demanding, and it is worth seeking out.

In 2019, along with many other 18-yearolds, I went off to college. My first big move. I packed my bags and flew from Portland, Oregon to Denver, Colorado to begin my freshman year. Life was exciting, mysterious and vast — I was in my ocean era. I was filled with eagerness and a bit of naivety when I moved into my dorm room and said goodbye to my parents. The first few hours were filled with distractions, girly conversations and room decorating. Universities are good at bombarding the bright-eyed, bushy-tailed freshmen

with activities to keep them distracted from the very real, very terrifying reality that their lives, as they know, are about to change forever. I remember walking with a few new peers around campus, touring the libraries and facilities led by upperclassmen. I’m a victim to zoning out during tours like these and within my self-induced trance came that sinking feeling. Where was I? Who are all these people? How many miles away am I from home? Hundreds? Thousands? What if I don’t connect to the people in Denver the way I did to my Portland girls? I remember excusing myself from the tour group and heading straight to my dorm room. Thank God my roommate was still on the tour. I curled up on my twin XL bed. I was still wearing the awful burgundy orientation t-shirt that every freshman had to wear during week one. I felt like a five-year-old on the first day of kindergarten. I ached for home and I sobbed.

Fast forward about one month, I’d made good friends on my dorm floor. I started feeling more like an adult than I ever had, I joined a sorority, my roommate and I coexisted very easily together and my inner dread became manageable. All that considered, I still yearned for home. I could tell my pining derived from something deeper than just missing the company of my family and home friends. There was something intangible that I could not pinpoint but didn’t bother digging into. I knew I was stuck in a funk, but did not know how to escape. Tik Tok dropped during this year which did not aid my soul searching. I remember doom-scrolling into the wee hours of the morning, consuming videos of lives better than mine. I vividly remember watching a day in my life vlog and the videographer lived minutes from a river where she would take her morning walks. You would’ve thought I had seen a picture of an ex-boyfriend with a new girl the way jealousy struck me.

While I was adapting to my new life, I decided a visit to the University of Oregon for Halloweekend would be a perfect treatment for homesickness. A handful of my best friends were students there, other people would be visiting from all over, and it just felt like a perfect time to get reconnected and refreshed.

I’ll never forget my Eugene-bound flight. I was sitting at my gate and felt a giddiness reminiscent of a kid on Christmas Eve. My two-and-a-half-hour long flight was grueling and I could hardly sit still with my anticipation. When the pilot announced the beginning of our descent, I turned on the song “Coming Home (to Oregon)” by Mat Kearney and flipped open my window shade. Like a lightning strike, I was zapped by the sight of the sun setting behind the Willamette River. The river I lived one mile away from as a kid. The river I drove alongside to get to school. This is the river where I learned how to wakeboard. This is the river that hosts a Christmas boat parade every year. The river that rose and fell, ebbed and flowed, yet remained anchored in the heart of Portland — my ol’ faithful. I felt like I was seeing my figurative mom waiting for me with her arms wide open at my old front door — changing herself while remaining anchored in my heart. Planes have a nasty habit of making me

feel melancholy, but this was a feeling like no other. I cried silently into my hands (embarrassed) but I couldn’t stop the waterworks.

I had no idea the impact geography had on my body until this first big move. My dad laughed at me when I told him living in a landlocked state made me claustrophobic, but I would die on that hill. Realizing I was states away from the ocean — states away from being able to truly breathe — felt like torture to me. The first 18 years of my life were spent in the passenger seat with my hand hanging out the window on a summer night. All of a sudden I was living in the middle seat of a cramped car with no air conditioning and no idea who was driving. When I heard that hardly any of Colorado’s river water ever reaches the ocean, it was like someone put me in a straight jacket. The water goes nowhere, its life path is decided, concrete and stagnant. I realized if I stayed in Denver, my fate would mirror that of its waters.

Some months and a worldwide pandemic later, I found myself starting my sophomore year at the University of Oregon. The moment I submitted my transfer application, a weight lifted off my chest. I was like a river dam that just gave out. In September 2020, I drove to Eugene to move into my new apartment with my two best friends. We had little say in what unit we wanted, but it could not have mattered less to me. When I walked into my bedroom and looked out the window, I saw the rushing Willamette River. I was now that TikTok girl walking by the river. I could now live the life I previously envied. Gallons of rushing water were racing through Oregon to get to the Pacific Ocean where it will take on a new form. That view reminded me that life, in all its forms — vast as the ocean, chaotic as a waterfall, serene as a pond — is always moving and always changing. The river running wild, despite its chaos, grounded me in a way that I did not anticipate. Much like a river, my life would always ebb and flow, pull and push and lead me somewhere solid — somewhere I am meant to be. I threw open my window and embraced the sounds, smells and sights of my old friend Willamette. And I knew damn well that river water would reach the ocean. And I knew I was home.

On an unusually warm Saturday afternoon in Elmhurst, Illinois, the phone rang. It was around 2 o’clock. For the entire day, all I could do was resent the fact that I had to spend this nice Saturday evening at 151 Bar and Grill bussing tables, pouring water and greeting customers with a fake smile while everyone else my age was enjoying themselves outside.

I was lost in my thoughts, dreading the shift ahead, when the sound of my mother’s voice pulled me back to the present. Her tone was soft, almost fragile, and it caught my attention immediately. That’s when I found out.

My mother put the phone down. She had tears in her eyes — “It’s Nico.”

On the phone, my aunt Tracy said that Nico, her oldest child of three, was missing and unreachable for the past few days. His old-school van was not in its usual spot in the driveway of their 70s style ranch home in Ocean Beach, San Diego.

Over the next few days, Tracy and her husband, David, were able to pinpoint Nico’s van which happened to be nestled in a vacant parking lot. Thanks to the phone company and a nearby cell tower, they found that his last phone call from a few days prior came from the van. They finally found his car, but not him. All that was left in the van was a crumpled piece of paper with Nico’s handwriting.

Nico had light blonde hair and bright blue eyes and was over 6 feet tall. He spoke with a gentle yet intelligent demeanor, and had a unique sense of humor. Despite our large age gap, I always felt included, respected, and loved by Nico.

Grief and mourning work in mysterious ways. When my mother hung up the phone and told me the news that Saturday before work, I was numb. I felt empty, but couldn’t cry. I was overly consumed in my little

world of anxiety, and the weight of Nico soon grew heavier with each passing day.

Prior to this devastating experience, I was already entering one of the loneliest and hardest times of my teenage years. You know, those awkward years between the ages of 16 and 18 where you’re still a kid but not one at the same time. I was a relatively blank canvas trying to find my place in a competitive, wealthy suburb of Chicago. I desperately cared what people thought of me and was always dipping my toes into various social arrangements, and feared being labeled as one thing.

I played lacrosse, but I was pretty bad, or ‘mid’ as the kids say. The team was cliquey and filled with popular bros who got all the attention and playing time, and I was constantly on the outside looking in. To find like-minded friends felt like a neverending maze of confusion, social politics and disappointment.

The first Monday morning following the news, my dad drove me to York Community High School at 6:45 a.m. We didn’t say much during the ride, but we sat in solitude as “You’re gonna make me lonesome when you go” by Bob Dylan came on. Indie rocker Ryan Adams had just released a new album called Prisoner. “To Be Without You” fittingly came on following the Bob Dylan song.

Both songs, in their own way, became a soundtrack to my grief. Bob Dylan’s voice felt like a gentle acknowledgment of the inevitable — loss, change and the quiet ache of Nico’s absence. The Ryan Adams tune, on the other hand, was sharper, more visceral and like a mirror reflecting the raw edges of my emotions. Together, they created a space where I could feel without having to explain; where the music carried what I couldn’t yet say aloud.

In the weeks and months that followed, I carried on with my life, going through the motions. I played a sport I didn’t like, nor was I any good at it. Between hanging out with friends and experimenting with making music, I was clueless about what I was even doing — I was fumbling through life.

The first summer without Nico.

As June slowly turned into July, I watched my schoolmates post pictures of their summers on social media: vacations to tropical places, parties, sporting events and exclusive hangouts. I saw faces laughing at jokes I’d never heard. Captions consisting of languages I didn’t speak.

My saving grace that summer was going to my grandfather’s lake house in Manistee, Michigan; “Paradise Bluff,” us Nelsons would call it. Since its purchase in 1980, Paradise Bluff has been a summer gathering place for my mother’s extended family with over 20 members from across the country reuniting. The home away from home is located off of Fox Farm Road in the northwestern lower peninsula beach town of Manistee, Michigan. Exquisite home-cooked meals, beach time, music on the swing and a much-needed break from technology and the chaos of modern society allow us to resonate with each other, catch up and spend quality time together at the end of July and the beginning of August.

Finally, our escape to Paradise Bluff arrived. Flocks of Nelsons arrived in chunks on Friday and the festivities began. We spent hours on our private beach at the foot of 100

wooden steps, sunbathing, swimming, laughing, playing volleyball, fetch with the dogs, music and eating handcrafted sandwiches on crunchy sourdough bread.

After the sun and freshwater of Lake Michigan, a warm shower and clean clothes perfectly prepare me for the gourmet, home-cooked meals by my Uncle Mark. Deep and well-spoken chatter about politics, pop culture, movies, music and current events fills the evening air on the back porch, overlooking the vast and wondrous Lake Michigan.

When our tummies are full, I hear the sweet and bluesy sonic vibrations of my Uncle Mark’s harmonica. I know it’s time to grab my guitar and join him on the wooden porch at the edge of the backyard bluff; just in time for the picturesque sunset.

The following day, instead of venturing down to the beach, I joined Tracy, David, Ben, Becca and the rest of the 20-something Nelson clan to have the inevitable conversation about Nico.

Tracy spoke with warmth and love about her son. Her emotional delivery and well-articulated speech sent shivers down my spine and placed my heart in uncomfortable knots. As she spoke, her words carried a profound sadness that seeped into me, filling every part of my being.

“Don’t ever hesitate to keep his name alive. Please feel free to bring up a memory or speak of him as if he’s still among us. Always.”

I couldn’t take it anymore. Watching my beautiful aunt painfully deliver such a difficult yet profound speech about keeping her son’s name alive felt like one thousand knives in the pit of my stomach.

I abruptly got up from the table and ran outside and down the gravel road until

all I could see were the dancing trees in the glistening afternoon sunlight.

All the suppressed feelings of loss, grief and sorrow that weighed on my soul since February, combined with the sharp pain of loneliness, anxiety and the emptiness of high school, finally poured out of me. The canopy of trees provided a comforting yet safe therapeutic blanket around me.

As I stood there, breathing in the crisp air and listening to the rustle of leaves, I realized I didn’t feel alone anymore. The trees, the sunlight, the earth all seemed to understand, quietly reminding me that I was never truly by myself. In that moment, I felt a deep sense of peace, as if the world itself was keeping me company.

The warm summer wilderness of Northern Michigan and Paradise Bluff helped me find the light in the darkness of that moment. As the tears flooded out of me, I looked to the dirt, then the trees, then the sky, thinking “I love you, Nico. I’ll never forget you and I’ll always keep your name alive.”

Words SAVANNAH LEE | Design, Illustration ABIGAIL RAIKE

When you think of a prison, what images come to mind? Is it filled with cinder blocks, steel bars and confinement? You might picture a correctional facility with guards and handcuffs and the like. However, a far more sinister concept of a prison is one that is selfimposed, and put in place by living in a society that breaks the fundamental laws of nature. As Americans, we subscribe to the belief that we are in the “Land of the Free,” that we are entitled to a certain way of life and that we can take what we want with little thought to consequence. But the life of the “Taker” is a prison; it’s an endless circle of working, making money, spending said money on things and going back to work too exhausted to step back and wonder why we have taken keys and locked

ourselves in confinement. Who is the “Taker?” He could be our forefathers. Those in power who sailed to foreign lands to stake a claim in the endless pursuit of power and influence. America was founded on the concept of “taking.” Taking the land in pursuit of the “Manifest Destiny,” taking resources from indigenous tribes. The Taker has many forms; the humble settler clearcutting land to build a homestead, the oil man buying out the homesteads to expand his empire or the banker offering unpayable loans to the oil man. In fact, we are all entangled in the web of taking. For millennia, we have been shaped into the mold of the Taker. The moment our ancestors chose to cultivate their own food, establish roots and build villages — later expanding into towns and cities — marked the beginning of our existence as Takers. In the Taker’s worldview, the earth is the dominion of humankind. By 2025, our relentless Taking is most visible in our obsession with consumer goods. Why do we love

Mass production is profitable only if its rhythm can be maintained.

- Edward Bernays (1928)

consumer goods? Is it because our DNA is embedded with the intent of acquiring things? Or is it because consuming is part of our society? Is it a learned behavior to cope with the burden of existence? Anything learned, of course, must be taught. And our teachers are not our parents or caregivers, but media and advertising agencies and companies who create products that need to be sold! The purpose of people’s existence, according to corporations, is to consume (Campbell, 1989). In the early days of consumer culture, the wealthy and upper-middle-class were the main targets of consumer goods due to their capacity to afford “wants” in addition to “needs.” The luxuries of fur coats and Persian carpets were unattainable for the typical meat packer or chimney sweep. They were available only to the railroad titans or shirtwaist factory owners. The “needs” of the average American did not include special-occasion flatware or intricate ball gowns for galas. However, the purchasing power of the wealthier class was not enough to sustain corporations and business organizations. The greatest economic problem of business executives in 1927 was the lack of consuming power in relation to the capable and ready powers of production. A solution had to be found: the ultimate consumer, in which the common man could be persuaded to expand his “needs” to include the aforementioned things. In

his 1928 book “Propaganda,” Edward Bernays wrote that “mass production is profitable only if its rhythm can be maintained.” In other words, businesses cannot simply produce in accordance with consumer demands, rather, businesses must employ propaganda and advertising to ensure continuous demand to maintain profits. In addition to powerful advertising and the increasing influence of media, lines of credit were introduced to provide the ultimate consumer with the opportunity to acquire purchasing power. This credit fostered an illusion of classlessness and paved the way for lower classes to take on debt to purchase non-necessity, luxury items to maintain the appearance of a higher identity (Passini, 2013). The foundation of consumerism was poured, and our ultimate consumer was more than happy to put brick after brick in the construction of his own prison.

The self-created prison of consumption continues into 2025. We have an addiction to consuming. The term “addiction” itself implies the individual becomes a slave to a solution to deal with mental suffering or to pursue happiness (Rinaldi, 2003). “Shopaholics” and “retail therapy” and deserving a “sweet treat” are intertwined with the single solution of buying, which will cure your depression, make you more beautiful and thin, give you attention from your desired group of sexual partners and bring financial success. Consumerism also urges the continuous purchase of the “new” item and disgust at the “old,” creating a culture of eternal dissatisfaction (Passini, 2013). Not only must we buy, buy, buy, but we also must seek our identity through what we buy (Passini, 2013). How can

we express our individuality without choosing appropriate, in-group products demonstrating who we are as a person, our political leanings and our values? How can people know you are an outdoorsy liberal without your Hydroflask, your pack of American Spirits or your Carhartt jacket? How will others know you work in finance without your Patagonia vest, New Balance shoes or Apple Watch? How can you define yourself as an individual without the branding to show for it?

The Taker lifestyle, as you are now aware, is defined by consumerism. You may condemn this idea and believe you have free will and try to consume sustainably or assert that your carbon footprint is mitigated by your conscious consumer choices. But the Taker problem is bigger than consumerism itself. We cannot simply buy sustainably because our economic system of capitalism focuses on the production and distribution of goods, and the market dynamics of supply and demand are driven by consumerism’s demand causing the need for more supply, and so on. Capitalism is what thrives on competition, innovation and the pursuit of wealth. And capitalism can never be sustainable.

Contemporary authors and economists have huddled around two schools of thought addressing the sustainability of capitalism: the reflexive political economy versus the critical political economy. The framework of the reflexive political economy emphasizes a process of super-industrialization to accelerate the movement toward eco-friendly capitalism (Huber, 1985). Expansionary development is essential. Increased wealth is needed to invest in the management of resources and technologies to minimize or improve environmental impact (Clark, 2021). This idea supports the notion that dominant institutions (i.e. the government and corporations) will incorporate ecological preservation and costs into their plans. Reflexivity will transform the global economy into a source of sustainable development. Similarly, the movement towards

eco-friendly capitalism will influence ecological concern at multiple levels within a society, and the growing existential threat posed by hazardous ecological risks will pressure powerful institutions to regulate the environment (Beck, 1992).

The self-imposed prison of hope in our leaders is partially to blame, and we comfort ourselves with the assurance that we are on track toward a reflexive political economy. After all, this theory assumes we possess altruistic institutions. Perhaps those we elect to office will produce laws and regulations to curb emissions and tax polluting corporations. Maybe the bourgeoisie will find it in their kind hearts to funnel their mountains of wealth into the development of sustainable infrastructure and the preservation of ecosystems. But when the 1% (including billionaires, millionaires and those earning more than $310,000 per year) account for 16% of all CO2 emissions worldwide and fossil fuel lobbyists gift hundreds of thousands of dollars to House and Senate representatives, both Republican and Democrat (Waldman, 2023), we start to have doubts. When corporations support “net-zero emissions” or not based on whichever political party occupies the White House — such as the case of JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs and the like rolling back climate-finance alliances after the 2024 Presidential election (Marsh & Kishan, 2025) — our hopeful scholars begin to doubt that those with money and power will invest in a climate-friendly future. How can we focus on ecological sustainability when there are profits to be made, cryptocurrencies to mine and oil and gas lobbies to satisfy?

The second framework of the critical political economy suggests

that dominant institutions lack the capacity and willingness to incorporate ecological costs due to the inherent contradictions between a sustainable economy and capitalist imperatives (Schnaiberg and Gould, 1994). Ecological degradation and resource depletion are not simply a stage of capitalism but a critical feature of capitalist development (Clark, 2021). Capitalist production not only requires stripping and withdrawing resources from nature, but also prioritizes exchange value to the point that the necessary regeneration of ecosystems is disrupted and vulnerable to collapse (Foster, 1999). Further, structural tendencies of the capitalist system often produce ecological changes that cannot be fully mitigated via technological innovations, so-called self-correcting market mechanisms or government reforms (Holleman, 2016). The critical political economy framework recognizes the reality of the Taker society. Any sustainable energy pledges or “net-zero” commitments are simply lip service because our economic system requires ecological degradation and depletion of resources.

However depressing our self-imposed prison may be, we need more than just a vision of doom. We need more than to be scolded and told we are guilty of systemic societal and cultural issues contributing to resource depletion. The cornerstone of Taker ideology is that the world belongs to man. But is there another way to live — one that doesn’t involve taking and consumerism and relying on

corporations or governments to save us? Can we unlock our self-imposed prison?

The opposite of Taking is “Leaving.” The culture of the “Leaver” follows the laws of nature. Leavers live sustainably without exploiting resources or consuming more than they need. To the Leaver, man belongs to the world, and humans function as part of an ecosystem. Man is not fit to rule the world more than any other living creature. Traditional Leaver culture involved hunter-gatherer societies at the dawn of the Agricultural Revolution. Perhaps the culture would be considered “primitive,” but it is worthwhile to further explore facets of Leaver culture and determine how we can change our relationship with the natural world. Indigenous communities make up only around 5% of the world’s population, but their sustainable living practices have major impacts on global sustainability development goals (Bansal et al., 2023). Indigenous peoples practice sustainable food systems that encourage biodiversity and the use of native plants, and work with, not against, challenging climates (WEF, 2023). Indigenous peoples also share these outputs within communities, preventing resource hoarding and keeping descendants in mind as they maintain their relationship with the natural world (WEF, 2023). Traditional controlled burning practices, as well as reforestation techniques, show a symbiotic relationship between these communities and their forests.

Our first step to exiting the selfimposed prison of our Taker existence involves redefining our relationship with nature by recognizing that the world does not belong to man. We can incorporate Leaver ideology into our Taker society and learn to live in harmony with our ecosystems. It may be difficult to picture this notion: How can I live in harmony with nature when I occupy a coastal city apartment or a concrete suburban dwelling? The answer lies in individual action. We can plant native grasses and shrubbery in our neighborhoods and our yards. The plants that sustain diverse climates for eons are best

equipped to handle water surplus or shortage and encourage native insect, bird and mammal species to inhabit our spaces. In cities, we can partake in community gardens, using compost materials and sharing activities with our urban neighbors. This shift in our relationship with the natural world is vital.

Another step out of our self-imposed prison is being honest with ourselves about our consumer habits. Part of Leaver culture is consuming only the “needs.” Taker culture thrives on unattainable promises made through the purchase of “wants.” And this next notion may be harder to stomach: The “wants” will not make you thinner or smarter or wealthier. The “wants” provide short-term satisfaction at the expense of long-term consequences. Living reasonably means reusing, fixing and refurbishing. It means holding off on the instant gratification from Amazon purchases or Target runs. Our individuality may need to become defined by more than our consumer preferences.

Our third and final step involves becoming aware that we are not, in fact, in a prison at all. The irony of the self-imposed prison is in the name — it is self-imposed. Our power to resist Taker culture exists within each of us. I am not suggesting that you quit your job or relocate to an Indigenous colony, but by resisting consumer culture, reusing, embracing our ecosystems and building relationships with our neighbors, we can embody the Leaver and encourage those in our circles to join us. In the “Land of the Free,” we still have the autonomy to make our own choices. I hope you will choose to leave.

Bansal, S., Sarker, T., Yadav, A., Garg, I., Gupta, M., & Sarvaiya, H. (2024). Indigenous communities and sustainable development: A review and research agenda. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43, 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22237

Billionaires emit more carbon pollution in 90 minutes than the average person does in a lifetime. Oxfam International. (2024, November 7). https://www.oxfam.org/en/ press-releases/billionaires-emit-more-carbon-pollution-90-minutes-averageperson-does-lifetime Beck, U. (1992). From industrial society to the risk society: Questions of survival, social structure, and ecological enlightenment. Theory, Culture, and Society. 9, 97–513. Bernays, E., & Bazon, I. (2013). Propaganda (1928). Alexandria Publishing House. Campbell D. (1989) The romantic ethic and the spirit of modern consumerism, London, UK: Blackwell.

Clark, T. P., Smolski, A. R., Allen, J. S., Hedlund, J., & Sanchez, H. (2022). Capitalism and Sustainability: An Exploratory Content Analysis of Frameworks in Environmental Political Economy. Social Currents, 9(2), 159-179. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294965211043548

Foster, J. B. (1999). Marx’s theory of metabolic rift: Classical foundations for environmental sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 105(2), 366-405. Holleman, H. (2016). De-naturalizing ecological disaster: colonialism, racism and the global Dust Bowl of the 1930s. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(1), 234–260. https:// doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1195375 Huber, J. (1985). Die regenbogengesellschaft. Ökologie and sozialpolitik [The rainbow society: Ecology and social policy]. Frankfurt, Germany: Fisher. Marsh, A., & Kishan, S. (2025, January 7). JPMorgan Quits Net-Zero Banking Alliance, following Citi, bofa. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2025-01-07/jpmorgan-quits-net-zero-banking-alliance-following-citi-bofa

Passini, S. (2013). A binge-consuming culture: The effect of consumerism on social interactions in western societies. Culture & Psychology, 19(3), 369-390. https://doi. org/10.1177/1354067X13489317

Rinaldi, L. (2003). Stati caotici della mente: Psicosi, disturbi borderline, disturbi psicosoma-tici, dipendenze [Chaotic states of mind: Psychosis, borderline disorders, psychosomatic disorders, addictions]. Milano, Italy: R. Cortina. Schnaiberg, A., & Gould, K. A. (1994). Environment and society: The enduring conflict. St. Martin’s Press. Waldman, S. (2023, February 1). Meet the top house recipients of oil and gas money. E&E News by POLITICO. https://www.eenews.net/articles/meet-the-top-house-recipientsof-oil-and-gas-money/

the local establishments are a huge part of what makes the places so appealing. Without a well-supported workforce to support them, these businesses will wither away. Even as the sport’s popularity expands, the institutions that support a ski tourist economy will not be able to keep up. As past wage-workers move away from these areas due to high prices, these regions suffer. Simultaneously, these same areas grapple with other significant existential threats.

It’s no secret that resorts themselves take a massive toll on the environment. They contribute to fossil fuel consumption, deforestation and water usage. These impacts result in harm to the ski resorts themselves. As the economic and social landscapes of ski resorts gentrify, the locals worry about the continuation of the sport as a whole.

Many modern ski areas are experiencing a massive rise in tourism which brings on its own environmental harms. Over-tourism causes higher carbon emissions required to travel to remote ski areas, overdevelopment of lodging, and a rise of consumerism within mountain towns. Specifically in the Bavaria region of the Alps, annual overnight guests have increased from 4.5 million in 2000 to 7.2 million in 2019. Most often a ski tourist will drive or fly (often both) to a resort, stay in lodging and consume local goods and services. As this type of classic ski tourism increases, mountain towns become less sustainable and inherently work against themselves.

Since the 1950s, April snowpack in the U.S. has fallen 23%. From this same point in time, 600 plus ski resorts have been forced to shut down.

Especially for ski areas at lower elevations, there simply is not enough snow to warrant a profitable season. In time, larger resorts too will begin to lose days of the year which hurts business and morale.

I love skiing, but it’s often hard to ignore the impending deterioration of the sport as I know it. However, I also believe that strong communities can make impactful changes. My hometown, as well as other mountain communities, are on the path to mend the wounds present in current ski culture. A recent group of Bendites have formed a coalition to buy back Mount Bachelor from Powdr Corporation which many believe to be the company responsible for huge price increases at the mountain. To me, this speaks to the passion that ski communities possess both on and off the slopes. Many of the same people care deeply about treating the environment with respect. On a global scale, projects like Save Our Snow push resorts across the world to work towards 100% renewable energy usage.

Ideally, there should be an emphasis on community education. Especially concerning tourists. Many tourists are unaware of or negligent to the detrimental social and environmental impacts associated with their hobby. In essence, it is about creating a community of more leavers than takers. If the pot tips, ski culture could continue to grasp the soul of its original identity. The astounding connection between humans and nature is ever present in skiing. If communities can give back to the mountains they in turn will continue to give back to us as they have for generations to come. Even though the sport may never look like what it did in the past, there is a sense that skiing will survive at least until next season.

A cultural journal analysis about leavers, takers and the quiet resilience of moss.

Every society interacts with the natural world in its own unique way. I’ve found that this is a reflection of deeply ingrained cultural values. Traveling across 27 countries has given me a wide range of perspectives on what it means to care for our planet. From some of the most populated cities in the world, to towns so small I’m recognized as a foreigner, I’ve observed how respect for the Earth — or lack thereof — manifests in the subtleties of daily life. It’s in the recycling bins placed thoughtfully in a public square, the snippets of conversation drifting from a café or the deliberate design of public transit systems that harmonize with the natural world.

Growing up in the United States, I can’t say my expectations for environmental consciousness were ever set particularly high. Americans live in a culture of convenience — single-use plastics, fast food and greedy, sprawling developments that prize immediacy and profit over sustainability. So, when I first traveled to Europe, I was utterly floored by how different things were. The recycling stations had multiple categories and were more detailed than I’d ever seen, despite growing up in the Pacific Northwest. Climate change awareness was omnipresent, with signs reminding people of their responsibilities toward the planet. I realized how much my American cultural lens had normalized apathy.

When I was in Switzerland, my perspective expanded in ways I hadn’t even imagined possible. I

spent the summer of 2022 with my Swiss friends in Zurich. Their genuine concern for the environment in casual conversation in day-to-day life reminded me of the same passion I only saw in my environmental science classes during my undergrad. It was at the famous “Street Parade,” where over one million people from all around Europe gathered for a free techno festival, that I noticed something almost utopian. By 6 a.m. the next morning, the streets were spotless, every piece of garbage removed with precision. It felt almost surreal to me, I loved the idea that celebration and responsibility can coexist which was something that hadn’t been real to me before. It wasn’t just Switzerland, either; countries like Sweden, Denmark and Japan embody a similar respect for nature. These nations prioritize sustainability, embedding environmental respect

into their cultural narratives. In Sweden, recycling and eco-friendly habits are second nature. The Danish concept of “hygge” emphasizes material simplicity, meaning it is respected to extend one’s comfort to include a respect for natural surroundings. Japan holds a more spiritual consideration for nature.

Japan was an anomaly to me. The religious Shinto belief that natural elements, like water and forests, are sacred resonates throughout the culture. I visited shrines in Kyoto where offerings were made to honor the Earth itself as well as different elements and seasons. I was struck by how this reverence manifests in modern practices too. I noticed this respect manifests in public policies such as stringent waste management systems and an emphasis on clean energy. I noticed how Japan, along with Denmark and Sweden, reflect the “Leaver” philosophy’s ethos — a belief in living within the bounds of nature rather than attempting to own or even conquer it.

During my travels, I met a British man named George Grant who is a sustainable engineering instructor at Nottingham University. Over drinks at a reggae bar in Ko Phi Phi, Thailand, he shared his research on the potential of moss to combat environmental challenges and climate change.

“My research primarily focused on how moss can combat flooding and improve the health of water to improve biodiversity and keep the environment safe,” he told me with the most excited energy I’d seen in days. “However, in the research, I came across ‘moss trees,’ which are in the early stages of use to combat air pollution and absorb CO2. So, it was a nice added benefit to my research.” He explained how moss is being developed in concrete as well, helping to reduce CO2 emissions in construction which is a major contributor to climate change. It was wild for me to be at the other end of the table with a beer in my hand thinking about how the same moss that would get stuck in between my

toes on the oak tree I used to climb as a kid would be the solution to a lot of environmental problems today.

George had a relentless sense of optimism for climate change. “I hope that there’s more legislation to compel developers and decision makers to demonstrate how CO2 has been reduced as much as possible,” he said. “Also, I think it’s really important to glamorize how cool combating climate change is to encourage more young people to care about the environment, and ultimately, encourage innovation. We’re now at a point where we need new solutions to reverse the impact of climate change rather than just slow it down.”

Like me, George travels with a constant analysis running in the back of his mind, observing sustainability practices in different countries. We shared our unique findings and referenced Thailand as a place with untapped potential. “Thailand feels less developed in terms of the sustainability strategies in the built

environment, and I feel like it has so much opportunity. If you look at cities like Singapore, there’s much more biophilic design and I feel Thailand would benefit from it. Both in terms of practicality; reducing flooding, which is common, and the general aesthetics to help preserve the landscape.” He compared this to the UK where sustainability measures in new developments are improving, but older ones remain problematic.

Listening to George speak gave me a lot of hope. Meeting people who have dedicated their careers to helping our environment is tear-jerking for me. It’s rare to meet someone with such a deep understanding of the problem and a clear vision for solutions, and it made me reflect on my intentions as I start my career as well.

Through all of this, I’ve realized how deeply connected culture is to our relationship with the planet. Some societies, like those in northern Europe or indigenous communities

SOPHIE SEBASTIAN

When I was a little girl

I knew I had this buried wisdom

How we can learn from nature

I still pretend I’m seven years old

Pondering this concept

in Asia and South America, seem to embrace what scientists call the Gaia hypothesis — the idea that Earth functions as a living organism, self-regulating and interconnected. Others, like the United States, seem determined to control and exploit the natural world, embodying the “Taker” philosophy that anthropologist and author Daniel Quinn so eloquently described. A mindset rooted in the belief that humans are entitled to dominate and consume Earth’s resources without regard for the balance of life.

After reflecting on my time abroad, I’m reminded that solving environmental challenges isn’t just about technology or policy — it’s about culture and connection. George’s belief that we need to make climate action inspiring resonates deeply with me. If we can shift the narrative to one of hope, creativity and shared responsibility, perhaps even “Taker” societies like the United States can begin to address our issues and change.

The passion I’ve seen has gifted me a renewed sense of purpose. It’s a reminder that change can happen, even in flawed systems. Traveling has taught me that culture isn’t just about food, language or art. It should be about how we each collectively treat the planet we live on. The question isn’t just about how to save the Earth. It’s about having the courage to be unapologetically bold and acknowledge that, ultimately, it’s about saving ourselves and rediscovering how to coexist in balance with the world we are all an integral part of.

Perhaps the answers lie in the small moments — in a conversation at a bar, a ritual at a shrine or the quiet resilience of moss growing on a city wall. Moss, a symbolic, beautiful little creature forever serves as a reminder of the inspiration I’ve drawn from lessons of diverse cultures and meaningful conversations about climate change.

As I’m now 22 looking outside my window each morning The invasive ivy peers at me, embarrassed

As it suffocates the life out of the trees

Who is meant to flourish from existing

The ivy knows it doesn’t belong here

It’s ashamed of its unnatural presence

As is the control it so desperately seeks

But life is not meant to be lived through control It’s meant to be lived through creation. The freedom each branch holds with no weight Is the creation it was always destined for For control was never meant to be there

So maybe I am 22, ashamed too

That I’d gone against my seven-year-old self’s wisdom And tried to control a life of mine, How unnatural of me

When the magic was all in creation

Over the last decade, I’ve been a lucky man. My office, home and playground have often been what many call “Mother Nature.”

I’ve spent countless nights under the stars in Utah, slept just a mile from the world’s most famous geyser, rafted the Grand Canyon’s labyrinthine walls, guided adventurers to barrier islands and explored America’s last frontier. I’ve called the world’s first national park home and a small alpine hut perched above a lake in New Zealand my office.

In a world where time outdoors is increasingly celebrated, my lifestyle draws attention and admiration. For some, especially those rooted in cities, my tales evoke awe, even envy. But behind the postcard moments lies a life that can be isolating, harsh and deeply unsustainable — not necessarily in the environmental sense, but in terms of personal happiness. What many cherish about urban life — community, culture and connection — is equally special. And yet we often pit these two experiences — “Mother Nature” and “Mother Culture”— against one another as opposing forces. This dichotomy dominates environmental conversations, painting a simplistic picture: nature is good, and culture is bad. It appeals to our human

tendency to frame the world in binaries — good versus evil; takers versus leavers. But this narrative misses a fundamental truth; culture is not separate from nature — it is a part of it. If we want to address climate change and ecological degradation effectively, we must stop dividing these forces and start reimagining their relationship. Rather than viewing ourselves as puppet masters of nature, controlling its fate (good or bad), we need to recognize that we are part of it, inseparably connected to the planet’s systems. This reframing has profound implications for how we perceive the world around us.

In Daniel Quinn’s “Ishmael,” the critique of “Mother Culture” underscores humanity’s anthropocentrism — the belief that humans are superior to and separate from nature. The novel presents two contrasting groups: “Takers” and “Leavers.” Leavers embody a philosophy of coexistence and sustainability, striving to replenish and rejuvenate natural areas while avoiding overindulgence. Takers represent those who exploit and deplete natural resources, prioritizing unchecked growth and consumption without regard for the long-term consequences on the environment. This mindset fuels many environmental crises, but vilifying

You must absolutely and forever relinquish the idea that you know who should live and who should die on this planet.

- Ishmael, Daniel Quinn

culture oversimplifies the issue. Whether in Yellowstone National Park or New York City, humans are animals, and the environments we shape — parks, cities, technologies, even what we think of as “wilderness” — are all expressions of our connection to nature. What if we didn’t see one as pristine and natural and the other as a polluted concrete jungle? What if we recognized both as part of the greater Mother Nature? This shift in perspective changes the stakes. Consider a bag of trash floating in the Schuylkill River as

it winds through Philadelphia. For many, it’s an everyday sight that hardly registers. Yet, if the same trash were spotted in a crystal-clear stream in Yosemite, it would prompt outrage. This discrepancy highlights how we compartmentalize nature into places worth caring for and places we ignore, failing to see the interconnectedness of it all. Melting glaciers and animal extinctions aren’t just nature’s losses — they’re ours. Rising seas don’t just threaten ecosystems, they displace millions. Wildfires don’t just burn forests, they destroy homes and livelihoods. Los Angeles, one of the wealthiest and most populous cities in the world, burns. Recognizing culture as part of nature forces us to see climate change as not just an environmental issue, but a human issue — one that will affect every aspect of our lives. And yet, our narratives often fail to connect these dots. We focus on images of turtles with straws in their noses and dying coral reefs — both undeniably tragic — but the bigger picture isn’t just about these isolated events. It’s about humanity’s survival as part of the natural world. Climate change isn’t just about ecosystems, it’s about cities going underwater, mass displacement and a future where clean drinking water becomes a rarity. It’s not a cinematic apocalypse

where everything changes overnight — it’s a slow, compounding crisis that could lead to rebellion, conflict and even war. This is the reality we must confront.

While cultural advancements have caused environmental harm, they also hold immense potential for restoration. Renewable energy technologies, for instance, align human ingenuity with ecological

We’re not destroying the world because we’re clumsy. We’re destroying the world because we are, in a very literal and deliberate way, at war with it.

- Ishmael, Daniel Quinn

principles. Solar panels and wind turbines harness natural forces, transforming innovation into tools for sustainability. Art and storytelling play an equally critical role in this restoration. Environmental narratives in literature, film and music inspire collective action and remind us of our deep connection to the natural world. Take Bob Dylan for instance. His lyrics like “Go out in your country where the land meets the sun, see the craters and the canyons and where the waterfalls run,” invite listeners to experience nature through vivid imagery. Such words evoke a sense of wonder and inspire people to reflect on what nature means to them. These creations demonstrate that progress doesn’t have to come at nature’s expense, and it shouldn’t come at culture’s expense either. To truly move forward, we need to bridge the gap between Mother Nature and Mother Culture.

Technological advancements often face criticism for their environmental costs, yet they are also essential to solving ecological crises. The paradox of progress lies in finding a balance between simplicity and innovation. It’s not about rejecting technology, but about using it responsibly to restore what has been lost. Urban design provides a perfect example.

I have amazing news for you. Man is not alone on this planet. He is part of a community, upon which he depends absolutely.

- Ishmael, Daniel Quinn

Green roofs, urban forests and efficient public transportation reduce carbon footprints while fostering community. These innovations remind us that culture, when guided by ecological ethics, can be a force for restoration. At its core, our social structure needs greater advocacy for interconnectedness. Culture, like ecosystems, thrives on relationships and collaboration. By acknowledging

that humans are not separate from nature, we can realign our cultural achievements to reflect our role within the web of life.

We arrive at a reconciliation of two worldviews: Anthropocentrism, which centers on human needs, and ecocentrism, which prioritizes ecosystems. A balanced approach recognizes that these perspectives are deeply intertwined. Human flourishing depends on healthy ecosystems and ecological restoration benefits from human creativity and innovation. This balance is evident in the concept of “rewilding the mind.” Rather than rejecting culture outright, rewilding invites us to rethink our narratives of superiority. By rediscovering our primal connections to the earth — whether through hiking, farming, climbing or simply observing nature, and whether it’s doing so in a national park or in your own backyard — we can create cultural frameworks that strengthen, rather than oppose, ecological harmony.

Mother Culture has its flaws — favoring the wealthy, dividing communities and unsustainable practices — but it is still a product of Mother Nature. And Mother Nature, indifferent to our divisions, reminds us of our shared vulnerability and resilience. Recognizing this interconnectedness inspires optimism: The belief that human creativity, guided by ecological awareness, can address environmental challenges while celebrating what makes us uniquely human. Rather than villainizing Mother Culture, we must reimagine it as a force for harmony. By embracing the creativity, beauty and connection that culture fosters, we can inspire solutions that unite human progress with ecological stewardship. The future depends not on choosing between nature and culture, but on recognizing that they are one and the same. Only then can we rise to the challenge of climate change — not as conquerors of nature, but as collaborators within it.

Each piece in this magazine uniquely unpacks the freedom found in forging an unconventional path. These stories discuss dominance and harmony, questioning whether the pursuit of control has distanced us from something more instinctive and whole. They explore the double-edged reality of progress where every step forward feels like two steps back. Through moments of quiet recognition and wild rediscovery, they reveal the things, both natural and unnatural , that bring us together. They challenge the walls we build around ourselves, the silent rules we follow and the possibility of stepping beyond them into something vast, untamed and real.

We began with Jess McComb’s piece, “The Church of the Wilderness,” a personal narrative that explores the evolving relationship between humans and nature. McComb reminiscences on her personal experiences hiking the Pacific Crest Trail with her father. She contrasts childhood fear of the wilderness with the eventual comfort found in its vastness. She highlights how humans have sanctified and estranged themselves from nature, bringing insight from iconic figures like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau. Through discomfort, silence and raw existence on the trail, McComb finds a profound sense of peace. One not rooted in divinity, but in the simplicity of being one with nature. The wilderness becomes her church, not as a place of worship, but as a space for clarity and freedom.

Jack Whayland’s “Imprisoned by Expectation, Liberated by Nature” follows the themes of self-imprisonment, escape and self-discovery. He transparently relives his experiences

and thoughts graduating from college and then partaking in vanlife. The piece explores the tension between societal norms and personal freedoms, illustrating how stripping life down to its essentials can be an act of liberation. Whayland emphasizes the importance of appreciating the good, and letting it immensely weigh out the bad in a story of breaking away from expectation and embracing movement and adaptability.