LET’S PLAY Toy Library | Toy Hospital | Storytelling Centre | Social Housing

2023/24 Unit 3: Civic Structure

Jessica Zhan S2156009

AD: Tectonics

DESIGN STATEMENT

‘Let’s Play’ is an architectural experiment that combines vibrant civic spaces with social housing. Located in the heart of Leith next to St.Mary Star of the Sea, the scheme includes a Toy Hospital and Toy Library (the only one in Leith), a Storytelling Centre, and an outdoor playground on the ground floor, with four stories of social housing above. The scheme investigates the concept of ‘Play’ from the aspects of Use, Structure, Construction, and Matter. It aspires to both embody and nurture the passion and resilience of fellow Leithers, reaching a wider impact on the entire Leith community.

In ‘Use’, the main concern of the project is bridging the gap between a mixed population around the site - a range of ages, social classes, racial backgrounds, and religious beliefs, devising a set of interconnected programmes that mitigates differences and celebrates togetherness. ‘Play’ is a crucial activity in our childhood, and through the Toy Library and playground, children of less wealthy backgrounds can gain access to enriching resources that they wouldn’t have otherwise. ‘Play’ is a practice of memory-making. In the Toy Hospital, old toys are repaired and passed down through generations, alongside stories of family and identity archived in the Storytelling Centre. ‘Play’ is also a spiritual practice, encouraging a more fundamental sense of spirituality that overlooks religious separations.

In ‘Structure’ and ‘Construction’, the project interprets ‘play’ as an act of empowerment and creativity. The ability to make and build something out of nothing, to manipulate as you wish, to fix and adapt without having to wait for ‘the construction industry’, is closely connected with sustainability, agency, dignity, and human rights. Separating permanent and ‘dressing’ elements provides an inclusive framework that gives freedom back to the users, not only allowing them to express their lifestyle but also saving cost and time from maintenance. The project is a doll’s house, an avatar, an urban stage set - it evolves as time goes on and needs change, but never quite finishes.

In ‘Matter’, ‘play’ is the joy of colour and the responsibility that joy is founded on. With a special focus on creatively reclaiming and upcycling components, materials are used as key markers of spaces, memory, and identity, both for the project and for the people of Leith. But more importantly, the choice and sourcing of materials reduce cost, safeguard health, and minimise embodied carbon. This is the rigorous dirty work that lifts up the ‘play’.

Finally, this project is my final undergraduate design project, and ‘Let’s Play’ is the ultimate message I want to leave for myself and the world. Architecture is often a difficult path, so is the journey of growing into an adult. Amidst the chaos of university and the challenges of adulthood, what is a better wish than to always keep that childish ability in ourselves to have fun and play?

CONTENTS

Site Introduction 4 128 Acknowledgement I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND: THE SOCIAL SCIENTIST’S FOLIO Rhythm Social Housing Leith [6] 8 10 12 II. USE: THE LEITHER’S HANDBOOK Site Program Precedent Proposal [14] 16 24 28 34 III. STRUCTURE: THE RESIDENT’S HANDBOOK Whole Scheme Housing Storytelling Future [58] 60 62 78 84 IV. CONSTRUCTION: THE PLANNER’S MANUSCRIPT Strategy Assembly/Disassembly [86] 88 94 V. MATTER: THE ARTIST’S FOLIO Materiality Sustainability [102] 104 120 VI. MATERIAL PACK: THE ARCHITECT’S FOLIO Drawings Images Models [130] 132 166 192 VII. APPENDIX: THE AUTHOR’S SKETCHBOOK [198]

16 QUEEN CHARLOTTE STREET, LEITH, EDINBURGH

Sitting just off of Constitution Street, the site was previously home to Headstart Nursery, immediately adjacent to the churchyard of St.Mary Star of the Sea. Though it frequently welcomes church-goers, it faces a relatively quiet street with little traffic and passersby. The site boundary is loosely defined to be the nursery grounds and the area of Queen Charlotte Street in front. However, we are invited to take more radical and urban approaches to the scheme, potentially expanding into the churchyard as well.

The brief outlines a duo-programme of social housing + civic centre. In the following pages, I will give more specific stories of how interpreted this and narrowed my focus to ‘Play’.

4 5 SITE B: AN INTRODUCTION

ORIENTATION MAP OF SITE TO EDINBURGH OLD TOWN

SITE MAP: EXTENT OF SITE B

Leith (Scottish Gaelic: Lìte): Scottish: habitational name from the port near Edinburgh which takes its name from the river at whose mouth it stands. The river name is of Celtic origin meaning “dripping (water)”.’

Abstract

Before I begin with any design project, I always like to review a set of literature that is relevant to the project’s focus and ambitions. find it easier and more motivating to have a ‘broader’ purpose and a more solid foundation to base my decisions on. This semester, we were lucky to have been provided with an incredible bank of writing on urban and civic theories by our tutors. This chapter sets the tone of my thinking throughout these 4 months with a collection of excerpts, corresponded with site photos that demonstrate my interpretation of them. Though not explicitly reinforced in the later chapters, the ideas noted in this chapter thread my entire thought process as ‘greater’ goals I am striving towards with my design.

I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

THE SOCIAL SCIENTIST’S FOLIO

RHYTHM SOCIAL HOUSING LEITH [8] [10] [12]

RHYTHM & CIVIC STRUCTURE

‘Civic architecture is obviously also the expression of civic values and this derives as much from a re sponse to solar orientation and the rhythms of the natural world, as the expression of a building’s use and its urban orientation.’ (pg.13)

‘Gadamer believed that rhythm plays a central role in revealing the participatory character of artworks, and that this establishes the ground for the continuous “relevance of the beautiful”... (pg.19)

‘...the rhythmic character of the typical situations that one finds in buildings, and in urban settings generally (as rooms), is accompanied also by the rhythmic character of architectural facades and thresholds (as niches, windows, doorways etc). Both enable the hinterland of building interiors and of civic territories to coexist in the rhythm of city life animated by both social occasion and analogues of myth, tradition, and the effects of weather, the seasons, natural and second nature etc.’ (pg.19)

Civic Ground: Rhythmic Spatiality and the Communicative Movement between Architecture, Sculpture and Site by Patrick Lynch

I can intuitively feel a unique sense of rhythm for each location I have been to, but it is very difficult to express it in exact words or even images. However, as the excerpts write, civic structures should ultimately align with and embody these distinct rhythms that characterise an area, culture, and people. I have been to Leith quite a few times throughout my years in Edinburgh, and have gone back repeatedly this semester to immerse myself - albeit intangibly in Leith’s way of life. This collection of images is the Leith have silhouetted in my mind.

8 I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND| II | III | IV | V | VI | VII 9 RHYTHM | SOCIAL HOUSING | LEITH

RHYTHM OF THE CITY

RHYTHM OF ARCHITECTURE

RHYTHM OF LIFE

SOCIAL HOUSING & HUMAN RIGHTS

‘Where after all, do human rights begin? In the small places, close to home.’

‘Residents also expressed concerns that complaints and requests for help were often slow to be answers, or were never resolved Homeowners expressed concern about the accuracy and transparency of billing for factoring services.’

Housing Rights in Practice: Lessons learned from Leith, by Scottish Human Rights Commission

‘...the construction industry has undergone a series of transformations in terms of sustainability, speed of construction, and technical and structural performance. Where these transformations claim to improve performance, they have also increased the complexity of buildings...Builders and developers establish capital-intensive infrastructure and production methods that allow them to operate as intermediaries...The growing platformization of the construction industry points towards one ambition: monopolization of the built environment.

Promised Land: Housing from Commodification to Cooperation by Pier Vittorio Aureli, et al.

Following the wider literary investigation of the aspirations of this unit ‘Civic Structure’, narrowed my lens to the social housing aspect of the brief. Leith is already home to many social housing estates, as the area is known for its relatively cheap rent compared to other areas in Edinburgh. But the conditions of these social housing are decent at best, perfectly fitting into the stereotypical image of ‘housing for the poor’ - Corbusian styled, so well-surveillanced that they suggest an over-abundant number of crimes, poorly-maintained, and lacking respect for its residents. The architecture of social housing has much deeper impacts on the social and health status of lower-income citizens, ultimately relating to their fundamental human rights and dignity. Bad designs can perpetuate their misfortune, but good designs can lift them up by improving their physical, social, and mental wellbeing. This helped me identify what want to do differently in my social housing proposal.

10 I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND| II | III | IV | V | VI | VII 11 RHYTHM | SOCIAL HOUSING | LEITH

Eleanor Roosevelt

SNAPSHOTS OF SOCIAL HOUSING IN LEITH

‘PERSEVERE’: THE LEITH MOTTO

‘So with our darkest days behind us our ship of hope will steer, and if in doubt, just keep in mind our motto: PERSEVERE.’

It is unknown exactly when the motto “Persevere” was adopted by Leith - we can see from the registration document that it was recognised as a motto when the crest was registered in 1889, but how long before this it was in general use is a mystery. The screen of the crest with the motto on display in South Leith Parish Church (included in the slideshow above) is believed to date back possibly to the 1600’s, howevre it has been touched up a few times since, and there is no knowing if the motto was part of the original design. Whatever the case may be, the motto “Persevere” is now firmly embedded in the mindset of anyone who grows up in, or becomes part of the Leith community.’

‘I was born in Leith, and it means home to me. Family, friends, streets and houses, shops, churches, all are part of my life’s experience, and the motto Persevere has helped me tremendously. I try to live up to it in every situation, and I love the strength and simplicity of such a powerful motto.’

-- Christine Muir

LeithForever - 100 Days of Leith

Finally, wanted to understand the people am designing for, not just in terms of their immediate needs but also their character. While we were visiting site, we constantly notice the word ‘Persevere’ pop up everywhere. A quick google search revealed that it is Leith’s motto. This plus the famous movie/musical ‘Sunshine on Leith’ helped me sketch an idea of Leithers as resilient, vibrant, and optimistic people, who rarely have an easy life but always take on challenges with positivity and joy. I became enthralled and invested in this group of people and was better able to see things in their shoes. Theorists say that civic structure should embody civic value, and ‘Persevere’ is perhaps the most notable civic value of Leith. This informed my entire design, from its concept and strategy to its final detail and execution.

POPS UP EVERYWHERE

12 I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND| II | III | IV | V | VI | VII 13

‘PERSEVERE’

| SOCIAL HOUSING | LEITH

Engraving of the crest and motto on lamp posts by the shore. Photo from 100DaysofLeith ‘Persevere’ graffiti on the wall of social housings near New Kirkgate

RHYTHM

The crest and motto are emblazened on the doorfront near our site that was renovating. Photo by author

The church next to our site used the same image as its crest. Photo by author

Screenshot from the movie Sunshine on Leith. The spirit of ‘Persevere’ is a crucial part of Leith’s identity and character.

‘In the end the meaning of the space is what takes place within it, that’s what it should be communicating. The designated, designed space is a framing communication that invites potential participants to share a certain particular communicative situation. The meaning is the use, the social function.’

Civic Ground: Rhythmic Spatiality and the Communicative Movement between Architecture, Sculpture and Site by Patrick Lynch

‘In the never-ending to-do list of adulthood, play can feel like a waste of time. We exhaust ourselves with tasks we should or have to do, but we rarely have time or energy for activities we want to do. Play offers a reprieve from the chaos, and it challenges us to connect with a key part of ourselves that gets lost in the responsibilities of adulthood...’

How to Add More Play to Your Grown-Up Life, Even Now, by Kristin Wong

Abstract

This chapter sets the scene for the design proposal through the aspect of ‘Use’. It collates materials and information that would be helpful for Leithers visiting the site, the story behind the project, how to get here, and what to expect. More specifically, we expound on the birth, development, and realisation of the concept of ‘Play’ in civic spaces to address the main concern of use: how do we bridge the growing barriers between people of different ages, ethnicities, economic backgrounds, and religious beliefs?

The journey begins with the existing site, identifying current functions and imagining potential uses, integrating them into co-dependent programmes: Toy Library, Toy Hospital, Playground, Storytelling Centre, and churchyard engagement, with social housing on the upper floors. According to these programmes, I conduct a series of precedent studies to generate massing and overall strategies. Lastly, we zoom-in to the final proposal, focusing on the design of spaces for public uses on the ground floor. For a project to be built, perhaps use is not the most important aspect to discuss. However, use is always the part in my head that gives the project importance and weight, making it come alive and inviting people to join the imagination of something beautiful that can come true. Before we resolve the structure, construction, and material in later chapters, please first accept this invitation to play.

II. USE THE LEITHER’S HANDBOOK SITE PROGRAM PRECEDENT PROPOSAL [16] [24] [28] [34]

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 16 17 SITE EXISTING FUNCTIONS,

SITE | PROGRAM | PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL 1 ACROSS THE STREET 6 HEADSTART NURSERY 9 COWORKING SPACE 2 ADJACENT BUILDING 7 CHURCH 10 RESIDENTIAL COURTYARD 3 PRESBYTERY GARDEN 8 LEITH PILATES 11 PRESBYTERY HALL 4 CHURCHYARD 5 LINKSVIEW HOUSE

SURROUNDING AREAS

Perhaps it is because the nursery has a fenced-off playground, or perhaps my longing for childhood play has been on the back of my mind as am growing up - more likely it is an intuitive thought that factors a bit of everything - but kept noticing play structures around Leith and using ‘play’ as a guiding concept of my project. Thus, I reviewed the existing play opportunities. found that ‘play’ is actually a huge gap that has so much more needs and potential. It is also something that is often overlooked by deeply important for children and adults alike. Furthermore, the permission to play relates to social housing, inequality, and access to education.

‘Play encompasses children’s behaviour which is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated It is performed for no external goal or reward, and is a fundamental and integral part of healthy development not only for individual children, but also for the society in which they live...’

The children’s playground is the closest thing to a melting pot a neighborhood can have People of different races and ages were spotted engaging in friendly conversations...the joys and agonies of raising children provide some common experiences that all parents can relate to and often want to share...’

--

‘In the never-ending to-do list of adulthood, play can feel like a waste of time. We exhaust ourselves with tasks we should or have to do, but we rarely have time or energy for activities we want to do. Play offers a reprieve from the chaos, and it challenges us to connect with a key part of ourselves that gets lost in the responsibilities of adulthood...’

‘Children living in social housing flats in a multimillion-pound riverside development in London have been warned off playing in shared spaces on the site by their landlords... A spokesperson for the mayor of London said: “All children should have access to outdoor and green space to play in and segregation of these spaces has no place in London.”’

‘there was something both physical and mental that happened when [children] worked their fingers. Imagination. Socialization. Freedom... The most powerful way children learn isn’t only in classrooms or libraries but on playgrounds and in playrooms. Toys should be free. And the library is the perfect platform...

-- Kristin Wong, How to Add More Play to Your Grown-Up Life, Even Now

PUBLIC PLAY SPACES IN LEITH

-- Harriet Grant, Social housing tenants warned of ‘play ban’ for children in London site’s shared spaces, The Guardian

-- Alexandra Lange, Every City Should Have a Toy Library

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 20 21 1 2 3 4 5 6 PERMISSION TO PLAY

Susan Isaacs, British early years educationalist & psychologist

-- Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Department chair in Urban Planning at UCLA

1. KEDDIE GARDENS 5 LEITH LINKS PLAY PARK

6 PILRIG PARK 4 TOLLBOOTH WYND PLAYGROUND

2 TAYLOR GARDENS

3 HENDERSON GARDENS

SITE | PROGRAM | PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

TRACING RHYTHM, IMAGINING USE

Simultaneously, we did a studio exercise imagining the potential uses of public spaces in our proposal. Instead of being more specific with the types of site activities want, I treated the entire site area as one giant public space and populated it with all the ways Leithers use their spaces currently. also corresponded the sketches with different time and weather scenarios to develop a sense of rhythm and pattern in use. This helped me to organise spaces on the site into distinct ‘character areas’ based on limiting conditions and types of usage, which laid an informative framework to develop programme and massing while remaining as inclusive and flexible as possible.

WEEKDAY NOON, SUNNY VS RAIN

WEEKDAY SUNNY, MORNING TO EVENING WEEKEND EVENING, SUNNY VS RAIN

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 22 23

WEEKEND SUNNY,

TO

FINDING RHYTHMS OF USE OVERLAYING ALL SCENARIOS TOGETHER SITE | PROGRAM | PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

MORNING

EVENING

PROGRAMME WAYS OF PLAY

The previous exercises led me down a research rabbit hole of potential programmes that suit the spirit and lifestyles of Leithers, while also being appropriate for site conditions. This included reading about Leith through news and blogs, digging through my brain, as well as listening to my intuition for what feels ‘right’. In the end, a set of 5 interrelating programmes with 5 different interpretations or ways of ‘Play’ - is devised as the use of this project, each corresponding with a ‘programme’ precedent that I have seen either in Leith or in other parts of the world. This also became a more detailed brief that led me through project development.

TOY HOSPITAL

TOY LIBRARY

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 24 25

Invite the Leith Toy Hospital to base their operations on the ground floor and host regular workshops teaching social housing residents about craft as a way of helping them learn a skill and find joy. Leith Toy Hospital, 64 Constitution St. Images from web. Open a toy library in conjunction with the Toy Hospital, allowing families to lend toys for free. This cuts expenses for social housing residents while bringing more creativity and freedom to kids from lower-income households. Toy libraries around the world. Images from web. PLAYGROUND

SOCIAL

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL Inspired by AnjiPlay a programme that encourages kids to use upcycled objects and build their own play, developing creativity, passion, courage, and intelligence. The playground will provide upcycled barrels, tires, and scaffolding planks. Establishing the second storytelling centre in Edinburgh that is dedicated to Leith. It will house archives from past events, provide books and stories for lending, and help bridge the gap between older and younger generations, and the church. Referencing A House for Artists as a key precedent. Providing social housing above ground floor with an emphasis on ‘play’ - creativity, adaptability, and agency of residents. Providing work opportunities for residents in ground floor spaces. Cas Holman’s page on AnjiPlay. Images from web. 100 Days of Leith storytelling event. Image from web. A House for Artists by Apparata. Images from web.

STORYTELLING CENTRE

HOUSING

ACCOMMODATING COEXISTENCE

During the initial site analysis, I had drafted a current diagram of key usages. The new programmes respond to this pattern by fostering more interactions between different user groups and opening up more public spaces for communal activities as demonstrated by the updated diagram on the right. It was a process of filling in the gaps, mitigating conflicts and creating new sparks. As work out potential co-existence opportunities between different uses/users, began to crystallise a vision of building usage and the types of designs that accommodate them. also started to form my circulation and massing strategies. TYPICAL WEEKDAY TIMETABLE OF EXISTING AREA INITIAL ITERATION OF SITE STRATEGY

PROPOSED WEEKDAY TIMETABLE OF SITE AREA

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 26 27

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

STUDYING DIMENSIONS

To continue to develop massing, I studied a number of precedents with similar programmes as mine, specifically noting their spatial arrangements and dimensions. I thought about them as puzzle pieces, each having a relatively fixed size that are arranged to form a fuller picture. This exercise helped me relate use with dimensions and spatial experience, further sharpening my idea of what I wanted to achieve and how I needed to do that. Referencing precedents also ensured that my massing is always reasonable for its intended use without having to test out every possible arrangement.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 28 29

PRECEDENTS

|

ARCHITECTS CHILDREN’S TOY LIBRARY | LAN ARCHITECTURE HOUSING COOPERATION DE WARREN | NATRUFIED LEA BRIDGE LIBRARY PAVILION | STUDIO WEAVE A HOUSE FOR ARTISTS | APPARATA SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

WATERLOO CITY FARM | FEILDEN FOWLES SEASHORE CHAPEL

VECTOR

APPLYING PATTERNS TO MASSING

Using the ‘puzzle pieces’ from different precedents, my massing iteration process was about arranging them in plan and combining that with environmental and contextual considerations in 3D. This was definitely not a linear process, and a lot of changes in the massing were instinctive jumps instead of coherent improvements. Also emerging through iterations are common dimensions among precedents. For example, ‘7’ meters or multiples of 7 kept popping up in spaces of various uses, which made me realise that 7 metres must be a great width that can accommodate for a range of uses. This helped my building become more adaptive from the very beginning.

1ST ITERATION

2ND ITERATION

3RD ITERATION

From the first iteration, it was clear that I wanted to lightly poke through the wall and inhabit the churchyard, as well as create a semi-enclosed public space that feels protected yet accessible The second iteration experiments with using changing ground levels to create boundaries and variations in uses, referencing the Economist Building. However, the scale was too big to be appropriate for this site. The third iteration takes from the previous two and tries to combine them with a ‘slope’ - a grander civic gesture. There were many interesting opportunities, but the residential building is too deep to create pleasant passages under it.

FINAL MASSING DIAGRAM

The final iteration continues the semi-enclosed courtyard idea from previous ones, but further adapts the scale for the site context. It also moves the entrance out from under the residential building, creating a compression-expansion experience.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 30 31

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

Investigations around massing was happening alongside the ‘voids’ in between massing the public spaces. From the first exercise of the semester, my group’s precedent was the public space of the New Art Gallery in Walsall. The development was quite monumental for such a small town, and the civic gestures were both dramatic and effective. Signature stripes in the paving reference crosswalks, inviting people to inhabit and tying the entire square together. The scheme also has a greater urban ambition, serving as the end of the High Street and bridging with the canal. A lot of these themes: connection, equality, and playfulness, coincide with my focus, so the architects’ moves were key references of my public space strategies. The stripes especially gave me a fun device to synthesise all my research and explorations around ‘Use’ into one homogenising feature.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 32 33 PUBLIC SPACE: NEW ART GALLERY WALSALL

TOWN MAP: RELATIONSHIP WITH LANDMARKS 1:2000 @ A2 SITE PLAN FRAMING THE END OF HIGH STREET SYMBOLIC PAVING: ENTRANCE, SCALE & EQUALITY PURPOSEFUL VISUAL CONNECTION WITH CANAL 1:500 @ A2 SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

MASSING

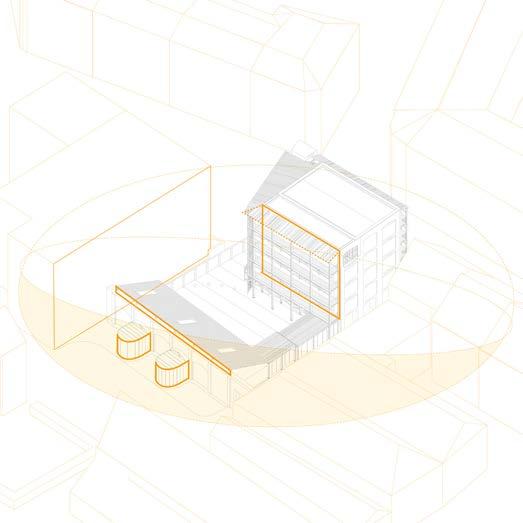

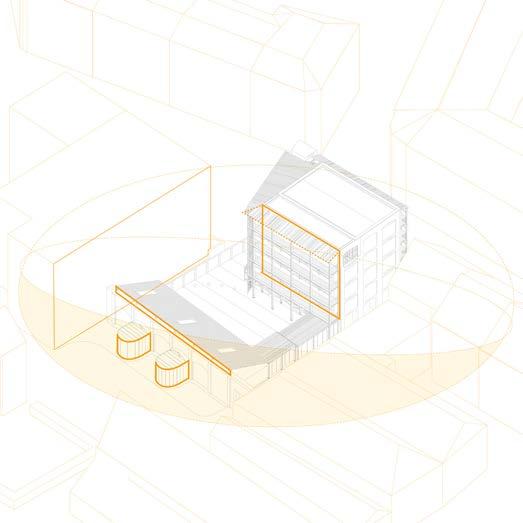

Thus begins the subsection about my final proposal involving ‘Use’. Welcome welcome. The scheme lightly peers into the churchyard to the southwest, and addresses Queen Charlotte Street with a grand civic gesture of the stripes, serving as crosswalk at the intersection of Queen Charlotte and Maritime Street. Massing responds to key environmental factors, optimising its own orientation without compromising the experiences of surrounding buildings. While the public space bordering Queen Charlotte is open and inviting, the main play space is protected from traffic, within the hug of internal building structures.

MAP 1:1000 @ A3

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 34 35 PROPOSAL

STRATEGIES

SITE

RESPONSE TO SUN DIVISION OF PROGRAMME RESPONSE TO WIND RESPONSE TO NOISE & TRAFFIC Key spaces all have south-facing windows for natural light with overhangs to prevent overheating. Massing minimizes obstructions of surrounding buildings Sufficient distancing & wind shields prevent wind tunnels, while openings provide opportunities for cross ventilation Massing shields the public space & main residential openings away from traffic & noise while making civic activities accessible through glazing SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

On top of general considerations, there are 4 key massing moves for the scheme, summarised by these photos of the 1:200 massing model in context. These moves ensure that the building sits snugly into existing surroundings, but also signifies something fun, different, and important to visitors from all angles. PROPOSED SCHEME IN CONTEXT

WITH 1:200 MASSING MODEL

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 36 37

KEY MOVES

1 2 3 4

Residential building height matches surrounding buildings without blocking existing residential windows

An entrance to be found - compression and expansion

Peeking through the existing wall into the churchyard - lightly bridging the gap

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

Continuing the street with a ‘colonnade’ of existing trees

No matter where you are visiting from, you can expect something inviting and different. These views offering a sneak peek of the entire scheme as you approach, only luring you to come closer to see what is inside. They are four different invitations to play.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 38 39 ON GETTING HERE...

WALKING DOWN TOLBOOTH WYND

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

VISITING FROM MARITIME STREET

WELCOMED FROM QUEEN CHARLOTTE STREET

APPROACHING FROM THE CHURCHYARD

All public spaces/services are on the ground floor. Each function has its own separate entrance facing the outside, but all spaces are internally connected and faces into the playground. The arrangement of spaces follow the general pattern of transition, from the busier Queen Charlotte Street to the quietude of the churchyard. The abundant openings allow the spaces to feel permeable and adaptable - users can open and lock them as needed.

CIVIC/PROGRAMMATIC STRATEGY BUBBLE DIAGRAM OF CIVIC SPACES CIRCULATION

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 40 41

FLOOR: AN INVITATION

PLAY

G

TO

G FLOOR PLAN 1:200 @ A3 Key 1 Toy Hospital 2 Toy Library 3 Residential Foyer 4 Playground 5 Corridor Cafe 6 Storytelling Centre Entrance/Cafe 7 Storytelling Centre 8 Toilet 9 Meditation Pod 10 Pocket Gardens 11 Repaved Churchyard SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

As mentioned before, the scheme aims to break down existing barriers between surrounding spaces, especially the segregation with the churchyard. Through different combinations of open and closed doors, the ground floor can adapt to different events and security needs. Below are just three examples of how spaces can be separately secured to serve distinct purposes. A visual connection with the churchyard is established through the Meditation Pods, maintaining the relationship between church and civic spaces without compromising security.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 42 43 NEW CONNECTIONS

PROPOSED TIME-BASED SPACE USAGE

‘CONNECTION’ PHOTO OF EXISTING SITE

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

‘CONNECTION’ PHOTO OF 1:50 EXPERIENTIAL MODEL OF PROPOSAL (PREVIOUS ITERATION)

FRAMING URBAN CORRIDORS

Public spaces work in tandem with programmatical needs, facilitating circulation and enlivening the microcosm of the scheme. Explicitly referencing New Art Gallery Walsall, the different types of public spaces address distinct use and limitations on different edges of the site, ensuring that there is no ‘back side’ to the project.

INVITATION TO EXPLORE

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 44 45

STRATEGIES

PUBLIC SPACE

Directly referencing the New Art Gallery Walsall, using striped pavings for a range of difference functions

was also spontaneously inspired by the newly built Jingyang Camphor Court, by Vector Architects how the outdoor timber colonnade converses with existing trees

AN

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

HARD EDGES & SOFT NUDGES PEAKING THROUGH

TO CHURCHYARD

The space facing Queen Charlotte Street houses the Toy Hospital and Toy Library. This is because these two programmes have the busiest businesses and streams of visitors relative to the Storytelling Centre. Old toys (either vintage or simply broken) are repaired by craftsmen in the Toy Hospital, and the Toy Library offers a catalogue of different toys for Leithers to check out. The two functions are internally divided with rotating walls that can be opened or closed at will, as a lot of the activities happening within must work together (for example, the toy hospital will regularly repair toys to be lent in the library). Foyer to the upper floor flats is separated from public programmes, though another door is in place that allows access directly from the foyer to the Toy Hospital, as residents from social housing can apprentice and work in the hospital and library as a communal programme (much like A House for Artists, by Apparata).

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 46 47 TOY HOSPITAL & TOY LIBRARY

TOY LIBRARY

TOY HOSPITAL

Leith Toy Hospital, 64 Constitution St, EH6 6RR

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

‘Every City Should Have a Toy Library’, The Atlantic

The furniture and cladding used for the Library’s interior are all crafted on-site with reclaimed pieces of timber, some painted with the signature Leith blue. This encourages a spirit of making and reusing that is both empowering and environmentally conscious.

Once constructed, the Toy Library will be the only one in Leith, giving valuable access to a range of toys for families who have less money to spend on non-essential equipments. With more chances and access to play, the project hopes to develop creativity and agency in the children of Leith to claim their own path and strive for equal opportunities to their peers.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 48 49

ACCESS TO PLAY

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

LEA Bridge Library Pavilion by Studio Weave, using reclaimed timber of various colours actually give the interior a more cozy and unique atmosphere.

The playground is covered with the stripes from Walsall, except alternating in orange and yellow. The stripes give the playground a sense of scale that invites children to inhabit and integrate into their own little games. The elliptical ring of mooring bollards further defines the main play space, also serving as public seats for parents. For the general use of the playground, I was especially inspired by Cas Holman’s collaboration with AnjiPlay, a programme that encourages children to build their own play from reclaimed barrels, planks, ladders, and tires. Their belief is that play does not depend on cost or sophistication it is actually more authentic and liberating to give agency back to kids. Thus, a set of reclaimed objects are stored in shacks to be used for children to build play under the help and supervision of Toy Hospital staff.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 50 51

PLAYGROUND & ANJIPLAY

INHABITED PLAN OF PLAYGROUND

The nursery playground that is currently on site first reminded me about the potential of using recycled materials on the playground

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

Having known Cas Holman and AnjiPlay from past experience further inspired the programme and layout of the playground

This is the view of the playground from the bottleneck entrance facing Queen Charlotte Street. wanted to create a sequence of compression and expansion, as if the small, nondescript door is actually a portal to another pocket of the universe, one that is more joyful, lively, and warm. Through this gesture, I want to spark curiosity in adults and children alike, inviting them to find joy even when life can be challenging.

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 52 53 JOY IS TO BE

FOUND

SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

Bordering the existing historical wall and the churchyard is the Storytelling Centre, as it is more peaceful and archival. Part of it works as a library, offering documents about old Leith stories for people to review. Part of it is an archive, keeping record of oral and written stories of older generations to live on. But most importantly, it is a centre for older and younger people to come together through storytelling, gathering the most elderly people who attend church with the emerging Gen Z and Alpha who rarely practice religion. It deals with the more fundamental part of spirituality - communion, perspective, guidance, and solace. Occupying the space between the churchyard and playground, the centre both programmatically and symbolically break barriers and build bridges.

Photos and stories from the ‘100 Days of Leith’ events are archived in the Storytelling Centre, where people can browse whenever they want

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 54 55 STORYTELLING CENTRE

INHABITED PLAN OF STORYTELLING CENTRE & MEDITATION PODS SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

was inspired by the warm ambience and very comfortable width proportion of Studio Weave’s Lea Bridge Library pavilion, so directly used its inside-to-outside proportion and borrowed its spatial qualities for the storytelling centre

| II. USE | III | IV | V | VI | VII 56 57 COMMUNION & PASSAGE SITE | PROGRAM| PRECEDENT | PROPOSAL

‘You let people know what’s structural and what isn’t...if you’ve done that then it’s intuitive that you can change it. It’s like an invitation to change it, and you don’t have to prescribe the changes. It’s just that it should speak for itself...We gave the residents handbooks as well, where we show site photos of what’s behind the top layer of the buildup, so that they know what’s underneath their floors and what’s in their walls.’

Scaffold podcast Apparata

Abstract

From the aspect of ‘Structure’, ‘play’ is lego-building, stage-dressing, and radical user adaptability, like your character’s room in the Sim’s that can constantly update and evolve as you progress in the story. It is another attempt to spark creativity in users and future-proof ar chitecture.

This chapter explains the structural strategy of the entire proposal, from a broad strategies to future possibilities. It is called the Resident’s Handbook because again referencing Apparata it provides crucial information for residents to customise and adapt their homes without interfering with load-bearing components. The project aims to make the structural framework as clear and intuitive as possible, giving users maximum ability and agency to claim their own homes without professional knowledge or profound experience.

The chapter begins with an overview of the Whole Scheme. Then, it moves on to the 5-storey housing block where the main focus lies, outlining permanent structural components against adaptable non-structural ones and the resulting use and design of the flats. The structure of the Storytelling Centre follows a relatively distinct strategy compared to housing, thus will be discussed separately. Finally, the chapter concludes with an imagination of future reuse, when all that is left are the permanent structures. Who knows, in 200 years, maybe this project will join the ranks of Old Town blocks, serving as a monument to the times of the past.

III. STRUCTURE THE RESIDENT’S HANDBOOK

WHOLE SCHEME HOUSING STORYTELLING FUTURE [60] [62] [78] [84]

WHOLE

CONSTRUCTION STRATEGY

These 8 steps outline the development of structural strategy, as well as its imagined evolution sequence. Some parts of it takes from lingering musings in ‘Use’, wanting to preserve the monumentality of the churchyard while mixing it with new buildings and programmes.

SCHEME STRUCTURAL &

Adding supporting structures & cladding around brick walls to enclose residential building Existing site Extending brick language to address level change & define public spaces Retaining historical wall & demolishing nursery 1 5 2 6 Extrapolating wall to multistorey permanent brick structural walls with pretensioned stone beams Using timber structures to facilitate circulation & further shape public space In the future, structures with shorter lifespan comes away, leaving a ‘ruin’ of permanent, monumental brick walls & platform Conserving wall & creating punctures 4 3 7 8 WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 60 61

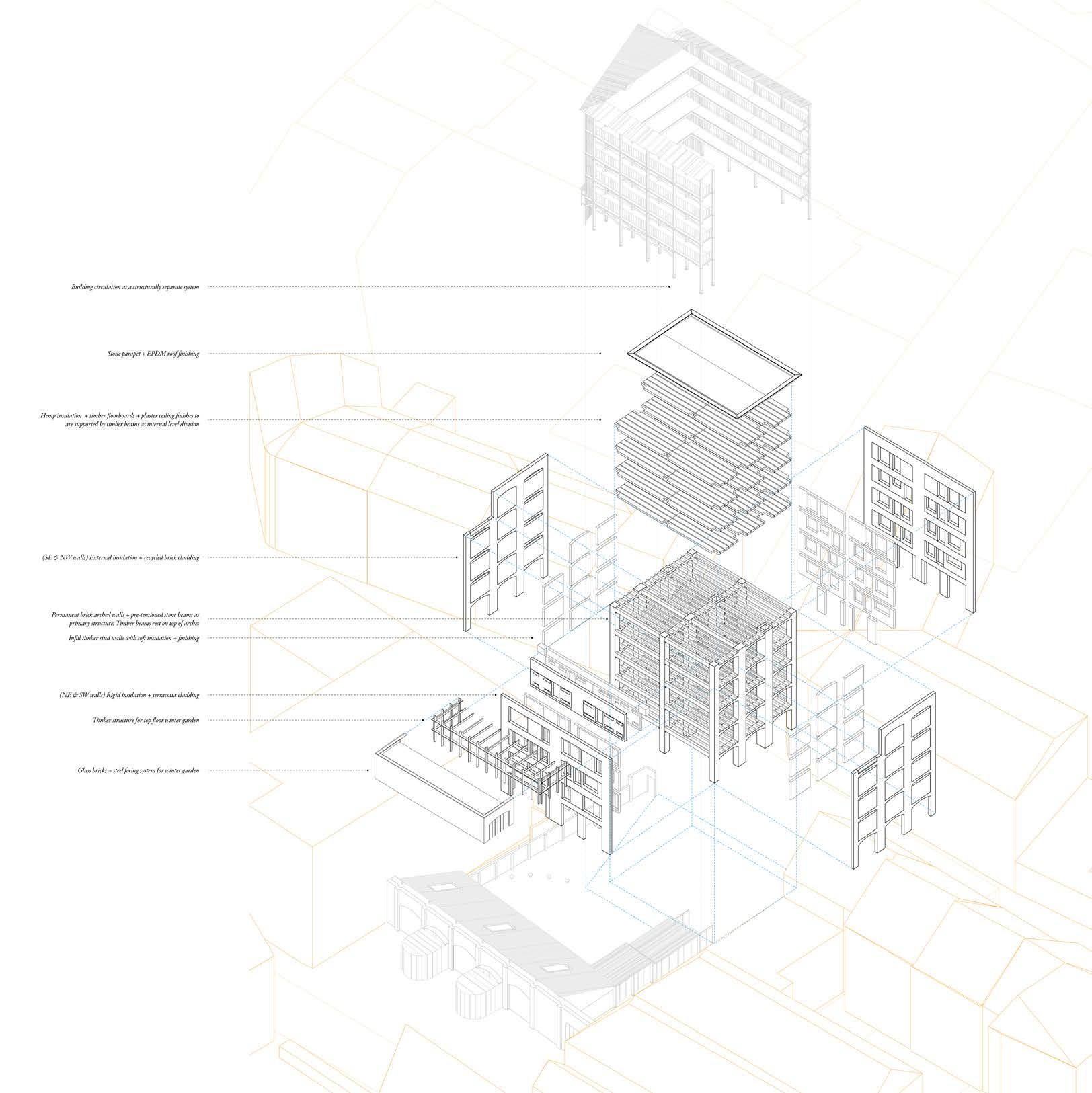

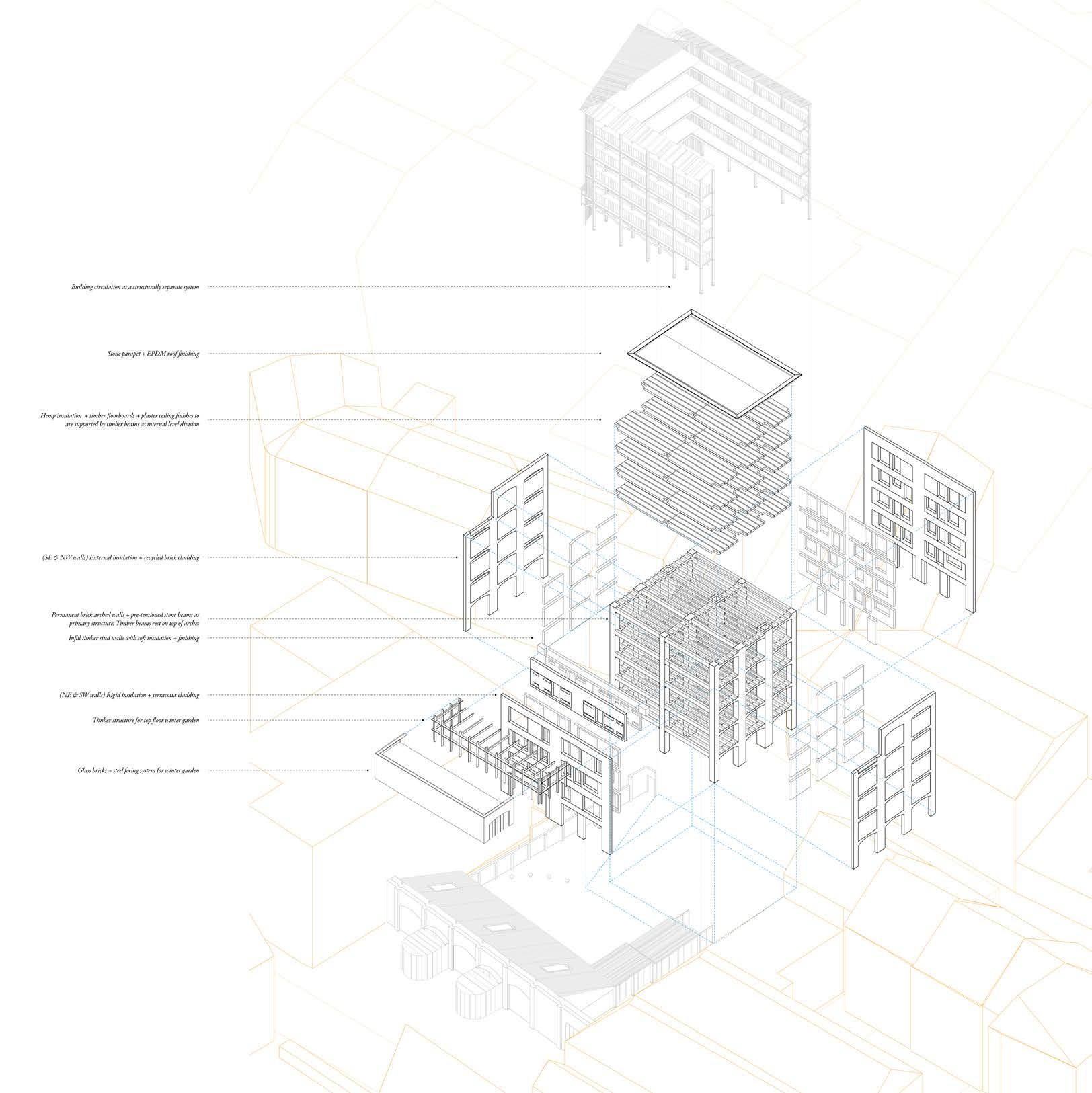

The housing block consists of two separate ‘sets’ of structures: the inner building and the circulation scaffolding wrapped around it. Only the inner building will be conditioned, consisting of layers of increasing lifespans based on the principles of stage-dressing adaptability.

EXPLORING STRUCTURAL LAYERS EXPLORING

HOUSING INTERIOR SPACES EXPLODED AXONOMETRIC

HOUSING STRUCTURAL ASSEMBLY

STRUCTURAL HIERARCHY timberSecondarystructure Primary masonry structure Tertiary infills & cladding Independent timber scaffolding 1:200 MASSING MODEL 1:50 CONSTRUCTION MODEL

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 62 63

The timber scaffolding references the structure and assembly of actual scaffolding. Wrapping around the flats to facilitate circulation. As the uses of the building evolve, different circulation routes might generate different forms of scaffolding - hence the reference to one of the most flexible and disassemblable structures in construction.

HEATED STRUCTURES IN ORANGE

HOUSING CIRCULATION SPACES EXPLODED AXONOMETRIC

‘SCAFFOLDING’

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 64 65

PRECEDENT: A HOUSE FOR ARTISTS

STUDYING STRUCTURAL STRATEGY IN SECTION

The core precedent for structural strategies is A House for Artists by Apparata. The concrete structural layout opens up the floor plan for creative adaptations by residents, fostering communal living and allowing future reuse. What extrapolated from this was not the concrete itself, but more the achieved layout in plan and section. It was fascinating to understand that the structure itself can generate use and design, instead of being a mere tool to achieve a separate design.

INTEGRATION OF STRUCTURE & USE IN PLAN

EXPERIENTIAL PHOTOS SHOWING INHABITATION WITHIN THE STRUCTURE

Deep hallway act as shading on warm, sunny days, preventing internal overheating in summer However, plenty of sunlight is still gained in the colder months when the sun angle is lower Lack of structural walls allow entire floor to be connected, for better solar gain & more flexible uses Simple yet high quality detailing allows maximum adaptability for the spaces WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 66 67

SCALE & FLEXIBILITY

Thus, even though the material system I used in my structure is completely different, my proposal extracted the key layout strategies of Apparata and can achieve a similar effect in opening up the section for flexible interior arrangements, providing alternate fire escapes to liberate the usage of hallways, allowing a higher-than-average floor height for more comfortable spaces. An added bonus to my proposal is the flexibility in section, as the floors are not part of the load-bearing structure. If needed, double- or triple-height spaces can be created for non-residential uses of the building.

IN SECTION:

PROPOSAL

SECTION BB’ SECTION AA’ Section perpendicular to hallways and Queen Charlotte street has more solid external walls to provide more privacy and structural stability. Internal floors are still flexible Section through hallways have more open external walls for natural light and sense of community. Structure also allowing for flexibility across multiple floors WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE 4 2 1 3 +3.687 +0.000 +3.130 +6.587 +9.487 +12.387 +15.287 +15.737 Key 1 Toy Library 2 Toy Hospital 3 Apartments 4 Residential Circulation 01 5m Section BB’ 1:200 @ A3 4 2 1 3 +3.687 +0.000 +3.130 +6.587 +9.487 +12.387 +15.287 +15.737 Key 1 Toy Library 2 Toy Hospital 3 Apartments 4 Residential Circulation 01 5m Section BB’ 1:200 @ A3 5 4 1 2 3 +3.687 +2.917 +0.000 +3.236 +3.619 +7.029 +6.200 +6.587 +9.487 +12.387 +15.287 +15.737 +1.000 Key 1 Toy Library 2 Apartments 3 Top Floor Apartment Sun Space 4 Cafe/Lounge 5 Storytelling Centre 01 5m Section AA’ 1:200 @ A3 5 4 1 2 3 +3.687 +2.917 +0.000 +3.236 +3.619 +7.029 +6.200 +6.587 +9.487 +12.387 +15.287 +15.737 +1.000 Key 1 Toy Library 2 Apartments 3 Top Floor Apartment Sun Space 4 Cafe/Lounge 5 Storytelling Centre 01 5m Section AA’ 1:200 @ A3 | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 68 69

TECHNICAL PLAN:

FORMING THE FLATS

Similarly, in plan, I extracted the structural layout of Apparata and applied it to a brick wall/ stone beam permanent structure. Residents need only to follow a set of straightforward principles to customise both the internal layout as they wish. This structural/infill framework also applies to the facade of the building. Each flat has a portion of the northwest and southeast facade they can adapt, as the loadbearing brick arch walls run perpendicular to those facades in plan.

STRUCTURAL DIVISION PRINCIPLE

APARTMENT ORGANISATION PRINCIPLE

TECHNICAL PLAN OF TYPICAL RESIDENTIAL FLOOR

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 70 71

ADAPTABLE OPENINGS: FRAMEWORK & INFILL

So it is that there are individual ‘soft spots’ on the NW and SE facades of the building that are customised by individual households, almost as if each family has their own ‘shop window’ they can curate for passersby, one that demonstrates their ways of life. Residents can choose from a catalogue of 4 different openings and arrange them onto timber stud wall panels according to their internal layout. These stud walls can then ‘fill into’ the permanent structural frameworks of brick walls and stone beams. The initial state of the building only imagines 4 possible arrangements (among countless others) to occupy the 4 residential floors. Openings determine how the domestic sphere interacts with the public. This gesture of freedom, though seemingly superficial, hopes to encourage residents to claim and keep their own homes as the beginning of their agency and power.

DETERMINING ‘SOFT SPOTS’

CATALOGUE OF OPENINGS

APARTMENT VARIATIONS G+1 2 x 2B flats G+3 2 flats of different sizes G+2 6B flat share G+4 2 x 2B flats + winter gardens WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 72 73

‘DRESSING’ THE ELEVATION

It then follows that the facades become a grid that is first dressed with a variety of infills and then the timber scaffolding wrapping around the building. It can be treated like an avatar, or picture frame, that always offers a sneak peek of what is going on inside.

NORTHEAST ELEVATION FACING QUEEN CHARLOTTE STREET

STAGE-DRESSING WITH A KIT OF PARTS

1:50 CONSTRUCTION MODEL

ELEVATION FACING PLAYGROUND

facades of different apartments Adding timber scaffolding Adding timber scaffolding

SOUTHWEST

Stacking the facades of different apartments Stacking the

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 74 75

TECHNICAL SECTION:

HIERARCHY & FLEXIBILITY

This coloured render of the elevation corresponded with construction details of the technical section demonstrates the hierarchy and readability of the structure more clearly. Fixed elements are distinguished from infill/flexible elements. Temporary timber scaffolding is contrasted with the relative permanence of the building’s structure. Different arrangements of openings populate the infills, accentuated by the colourful doors, yet they all harmonise with the overall facade and fit with the street elevation. The structural strategy of the entire project can be read on this one elevation: an homage to masonry walls, clear hierarchy defined by materials, the radical approach to adaptability, and the embodiment of ‘play’.

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 76 77

The Storytelling Centre adopts a timber structure that relies on the historical wall for load-bearing and the southern facade. The structural importance of the wall reinforces its symbolic significance as the backbone of the centre. A series of timber trusses rest on the wall on one end and supported by timber twin columns on the other. Similar to Waterloo City Farm, the timber structure is capped at either end with stud walls and finished with reclaimed corrugated steel sheets for the roof. There is a small area of cold bridging with the truss that continues from internal to external spaces, just like Waterloo. However, the impact of this is minimised with the small cross-sectional area and sufficient insulation on all other faces.

CORRIDOR CAFE + STORYTELLING CENTRE

EXPLODED AXONOMETRIC

STORYTELLING: STRUCTURAL STRATEGY

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING| FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 80 81

TECHNICAL SECTION CC’ THROUGH STORYTELLING CENTRE

FUTURE ADAPTABILITY & MONUMENTALITY

Finally, the permanent structure of the project takes on a strong, monumental presence itself. In 100 years, when all the dresses come apart, the arched brick walls stand against the arched historical wall of the churchyard, paying homage to the original arches while marking a separate era in history. The L-shaped brick platform that wraps around the Playground is almost reminiscent of an empty stage, quietly waiting for the next show. The definitions of these remaining structures naturally frame a civic square with characteristic mementos scattered across a carpet of brick and stripes. Though the significance of the space feels more solemn than fun, it can still accommodate for all forms of ‘Play’.

CURRENT PROPOSAL: TOY LIBRARY

PROPOSED USE IN 100 YEARS: MONUMENT

WHOLE SCHEME | HOUSING | STORYTELLING | FUTURE | II | III. STRUCTURE | IV | V | VI | VII 84 85

SQUARE

‘...the construction industry has undergone a series of transformations in terms of sustainability, speed of construction, and technical and structural performance. Where these transformations claim to improve performance, they have also increased the complexity of buildings...Builders and developers establish capital-intensive infrastructure and production methods that allow them to operate as intermediaries...The growing platformization of the construction industry points towards one ambition: monopolization of the built environment

Promised Land: Housing from Commodification to Cooperation by Pier Vittorio Aureli, et al.

Abstract

‘Construction’ works closely with ‘Structure’ to a point that it is hard to actually draw the line between the two chapters. In the previous chapter, the project’s structural ambition in terms of adaptability, customisation, and demountability are outlined as a part of the bigger structural framework. This chapter delves deeper into how these ambitions are realized in the detailed construction of structural/nonstructural components, focusing on the assembly and disassembly of non-loadbearing layers.The chapter first introduces the overall construction strategy and hierarchy of the proposal, then zooms into several key junctions in the proposal to expound on with technical drawings and the construction model. Here, ‘Play’ is the fitting of the lego pieces, the matching shapes of the jigsaw. It is allowing the residents to understand the construction of their homes with clarity, allowing the workers to grasp the construction sequence and goal with ease, and simplifying the process as much as possible - again, moving power away from contractors to the hands of users.

IV. CONSTRUCTION

THE WORKER’S MANUSCRIPT

STRATEGY ASSEMBLY/DISASSEMBLY [88] [94]

SEPARATION OF COMPONENTS & INTUITIVE ASSEMBLY

The strategy of construction is very simple: what is the most intuitive way layers can come together? How can different components of the building’s envelope be changed without interfering with others? The answer is the separation of all components from each other: the floorboards, infill walls, internal walls, and external circulation.

PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION SEQUENCE / POTENTIAL STATES OF BUILDING 1.

90 I | II | III | IV. CONSTRUCTION | V | VI | VII

loadbearing brick/stone structure on compacted stone foundation, with optional timber beams to separate floors 2. Adding timber stud walls and floors, which then support envelope materials like insulation & cladding 3. Adding timber scaffolding to define circulation spaces, which is structurally independent but can rely on brick walls for extra rigidity 4. (in 50 years) Timber scaffolding can come away, and internal arrangement can adapt to non-residential uses 5. (in 100 years) Only the brick wall and stone beams will remain, with optional timber secondary beams

Permanent

TECHNICAL

This section demonstrates the construction detail of the building in its current state, with each housing floor adopting a different internal layout and external opening layout. The top floor of the social housing even uses a completely different cladding system to make a winter garden facing the south. The timber structure of the scaffolding, corridor cafe, and Storytelling Centre lightly rests on brick platforms. This is one moment in the material bank that is the building.

92 93 I | II | III | IV. CONSTRUCTION | V | VI | VII

SECTION: THE MATERIAL BANK

STRATEGY | ASSEMBLY/DISASSEMBLY

ASSEMBLY/DISASSEMBLY SCAFFOLDING

The scaffolding is a timber structure using standard sizes of C16 softwood timber, all bolted together to allow disassembly and ease of future reuse bolts are much less damaging to the timber compared to nails. Like an actual scaffolding, the easy assembly process can be streamlined and adapted. The structure is separate from the building’s envelope, and the construction is one module that is repeated across different levels and in plan.

5.

94 95 I | II | III | IV. CONSTRUCTION | V | VI | VII

21mm reclaimed pine planks

100x100mm douglas fir timber battens

75x225mm C16 douglas fir beam

47x225mm C16 douglas fir beam

1.

2.

3.

4.

47x100mm reclaimed C16 douglas fir bracing

Timber twin column (see opposite spread for detail)

48.3mm diameter reclaimed scaffolding tube as railing, painted blue 8. 26.9mm diameter reclaimed scaffolding tube as railing poles, painted blue 9. 27x120mm steel railing skirting piece, painted blue Structurally separate parts TECHNICAL SECTION OF SCAFFOLDING COLUMN SPLICE SEPARATION OF STRUCTURE

timber

used for standardised sourcing and construction, as well as ease of future disassembly and reuse All components are bolted together to minimise damage to the timber and enable future reuse as well Final assembly outcome STRATEGY | ASSEMBLY/DISASSEMBLY

6.

7.

C16

is

STORYTELLING: TIMBER STRUCTURE FOR DISASSEMBLY

The timber structure of the Storytelling Centre resembles that of the residential scaffolding. It uses standard C16 timber components assembled with bolts for disassembly and reuse. The structure only lightly rests on the historical wall with minimal bolting and drilling to prevent damaging its integrity.

We found anchors embedded in the wall on site, suggesting that it was previously used as support for other structures, and that it is reliable for bolting and anchoring.

1. Existing Masonry Wall

2. New Masonry Wall Envelope

Vapour control layer

195mm hemp insulation + 47x195mm douglas

battens @ 600mm centres

90mm wood fibre insulation board - Breather membrane - 50mm ventilated cavity - 102.5mm waste brick wall cladding, with open perpends at 5 brick intervals

3. 38mm Double-Glazed Awning Window

TRUSS TO BASE BEAM CONNECTION TWIN BEAM SYSTEM CONNECTION

TECHNICAL SECTION OF SCAFFOLDING

TRUSS TO MASONRY WALL CONNECTION OVERVIEW

100 101 I | II | III | IV. CONSTRUCTION | V | VI | VII

-

-

fir

-

STRATEGY | ASSEMBLY/DISASSEMBLY

4. Timber Truss 5. Roof - 20mm plywood board finishing - Vapour control layer - 120mm hemp insulation + 47x120mm pine timber joists @ 400mm centres - 180mm wood fibre insulation board - 18mm OSB sheathing board - 10mm waterproof layer - 19mm reclaimed corrugated metal roof sheet

‘There must be a better way to make the things we want, a way that doesn’t spoil the sky, or the rain or the land.’

Paul McCartney

This is the final chapter of the main body of this portfolio. It examines the project from the material aspect. Material can seem to be the most insignificant part of a building like the textures you paste onto the building after the model is built. However, it directly determines the atmosphere of the spaces and the sustainability of the scheme. have found concerns about material to pop up with every design decision I make, and it is inextricably tied to ‘Use’, ‘Structure’, and ‘Construction.

The chapter begins with an investigation of ‘materiality’, focusing on the more experiential and aesthetic choices that were made to enhance the project. ‘Matter’ is used as an expression of the values of this project and the culture of Leith, especially in the treatment of facades and the use of colour. Then, we transition into the ‘drier’ part of the chapter that deals with sourcing and sustainability, including U-value calculations of building envelopes. The chapter concludes with a rough embodied carbon assessment of the scheme, demonstrating that good design does not have to come at the expense of polluting the environment.

With any ‘Play’, there is the dirty work of laying the ground rules and ensuring safety - the backstage of the show. This chapter is exactly that. Coming to the end of this story, it conveys that ‘Play’ is not just about fun, but involves a sense of responsibility and commitment to make the world a better place.

SUSTAINABILITY

Abstract

V. MATTER

[104] [120]

THE ARTIST’S FOLIO

MATERIALITY

PRIMARY-SECONDARY -TERTIARY MATERIALS

Perhaps the most significant takeaway had about material culture is the clear expression of primary, secondary, and tertiary materials that correspond to structural strategies of buildings. Primary materials/structure is most always heavy masonry, with secondary timber/ steel structures and tertiary elements in bold colours. This informed my material strategy to also correspond to my structural hierarchy and evolution, relating the expression of materials with their lifespan and use. Since tertiary materials need to be the most flexible and discarded the most frequently, they are mostly reclaimed/ upcycled materials with a creative spin.

PRIMARY MATERIALS

SECONDARY MATERIALS

TERTIARY MATERIALS

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’ PHOTO OF 1:50 CONSTRUCTION MODEL OF PROPOSAL PHOTO OF EXISTING SITE

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’ PHOTO OF 1:50 CONSTRUCTION MODEL OF PROPOSAL PHOTO OF EXISTING SITE

MATERIALITY | SUSTAINABILITY | II | III | IV | V. MATTER | VI | VII 110 111

The ‘symbolic’ take on material continues to the paving, used to subtly mark boundaries and characters of each area.

PAVING: SUBTLE SYMBOLISM

3 4 2 5 6 9 10 11 14 15 12 13 01 5m 1:200 @ A3 DRAINAGE DIAGRAM GROUND FLOOR PAVING PLAN RECLAIMED BRICK, RUNNING BOND ASPHALT

GRAVEL

TREE SUDS

STRIP

YELLOW & ORANGE CORKEEN RECLAIMED BRICK, FISHBONE BOND EXISTING COBBLESTONE PINE TIMBER FLOORBOARDS 1 Entrance area 11 Storytelling centre 2 Entrance area planters 9 Separation between pocket garden & meditation pods 3 Welcoming crossroad 10 Pocket gardens 4 Playground 13 Residential foyer 15 Meditation pods 5 Queen Charlotte Lane 6 Playground seating & ramp 12 Toy library & hospital 14 Toilets 7 Churchyard 8 New driveway for churchyard MATERIALITY | SUSTAINABILITY | II | III | IV | V. MATTER | VI | VII 118 119

BABY YELLOW THERMOPLASTIC ROAD PAINT SUDS PLANTING PITS

SUSTAINABILITY:

SOURCING & REUSE

Finally, the project aspires to limit the sourcing of all major materials to within Scotland, specifically within a 75-mile radius of the site. The collage to the right collects sourcing and transportation information. Sourcing local materials not only reduces the carbon cost of transmission but also helps boost the local economy, extending the ambition and impact of the project to more people in the construction industry.

‘Increased timber construction is also an opportunity to increase demand for homegorwn timber, driving more domestic tree planting...Increasing demand for homegrown softwoods in construction is limited by a lack of market demand for C16 timber which is the strength class most domestic softwoods are graded to. C16 timber is strong enough for the demands of most construction, but the current greater market familiarity with the higher grade C24 timber the common grade of imported timber - leads to overspecification. More work is needed to better promote and utilise the strength and density of homegrown C16 softwood in construction.’

Timber in Construction Roadmap by Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, UK Government

MATERIALITY | SUSTAINABILITY | II | III | IV | V. MATTER | VI | VII 120 121

Lastly, an embodied carbon assessment is completed for major building components. The bulk of embodied carbon comes from permanent structures, mitigated by the fact that their lifespan can reach hundreds if not thousands of years. Most cladding/infill materials are bio-based, acting as carbon storages instead of carbon emitters. Thus, while they may have to circulate more frequently, they can have a positive impact on CO2 emissions and waste management. Even though this assessment does not include every building materials, the excellent carbon score that is achieved means that the project is environmentally responsible and contributes to a greener vision of the construction industry. It proves that we can make things we want without spoiling the blue waters and blue skies.

CARBON FOOTPRINT OF MAJOR BUILDING COMPONENTS

EMBODIED CARBON CALCULATION OF MAJOR BUILDING COMPONENTS

Notes: - Negative A1-3 ECFs mean that wood-based materials sequester more carbon than emitted during production and construction - All distances used for A4 Transport have been outlined in the Material Sourcing Map displayed previously - A5a site activities is estimated as 1400kgCO2e per 100,000 pounds construction cost as outlined by the RICS

EMBODIED CARBON

MATERIALITY | SUSTAINABILITY

Material Volume (m3) Mass (kg) A1-3 (kgCO2e/kg) A4 (kgCO2e/kg) A5a (kgCO2e) A5w (kgCO2e/kg) Total (kgCO2e) Wood fibre (sequestration incl.) 254.371 15262.26 -4.167 0.00812 350.56 -0.024 -63838 Hemp (sequestration incl.) 248.397 6209.925 -4.400 0.00812 -0.044 -27545 Douglas fir softwood (sequestration incl.) 76.19 40380.7 -0.237 0.0124 0.015 -8444 Kenoteq K-briqs 43.973 7079.653 0.00758 0.0031 0 75.6 Pre-tensioned stone beams 30.4 82384 0.079 0.0126 0.012 8530 Compacted stone aggregates 92.728 148364.8 0.087 0.0126 0.013 16681 Pre-cast concrete slabs 72.088 173011.2 0.139 0.0126 0.002 26518 Reclaimed bricks 121.264 206148.8 0.1278 0.005 0.037 35045 Structural bricks 143.478 243912.6 0.213 0.0073 0.059 68143 Total Carbon Footprint: 55517 kgCO2 Total Internal Floor Area: 1138 sqm Carbon Score: 48.78 kgCO2e/sqm It’s an A!

UK Construction Costs

million

| II | III | IV | V. MATTER | VI | VII 126 127

guide. Construction cost is estimated based on ‘Typical

of Buildings’ published by costmodelling.com on April 1, 2024 - to be a 2.5

project

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’ PHOTO OF 1:50 CONSTRUCTION MODEL OF PROPOSAL PHOTO OF EXISTING SITE

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’

‘MATERIAL CULTURE’ PHOTO OF 1:50 CONSTRUCTION MODEL OF PROPOSAL PHOTO OF EXISTING SITE