LAND OF LIVING SKIES

A Saskatchewan Prairie Architecture

MArch Thesis

Jessica Gu 2024

MArch Thesis

Jessica Gu 2024

LAND OF LIVING SKIES A SASKATCHEWAN PRAIRIE ARCHITECTURE

by Jessica GuBachelor of Architectural Science

Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University), 2020

A thesis presented to Toronto Metropolitan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in the Program of Architecture

Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2024

© Jessica Gu 2024

AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS

I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners.

I authorize Toronto Metropolitan University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research.

I further authorize Toronto Metropolitan University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research.

I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public.

Land of Living Skies: A Saskatchewan Prairie Architecture Master of Architecture 2024

JessicaGu

Program of Architecture | Toronto Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

The Saskatchewan Prairie can be described as the sky and fields, divided by a continuous horizon line; this iconic image is the common perception of the landscape. By studying the landscape through four lenses, the prairie shows that it is rich with stories in its physical conditions and cultural phenomena. Architecture becomes a means of documenting the landscape by translating the intangible into tangible design interventions. Opportunities for investigation can be found in the archetypes that represent the existing landscape: from combines, to gophers, to catalogue homes, to native grass, to railways, to birds, and many, many more – each one a fragment that represents some aspect of Saskatchewan. Tying together the vast plains of Saskatchewan and the fragments of investigations is the Land of Living Skies Road Trip, a collection of interventions spread out across the province, experienced by car. So pack a bag, bring a friend, and get ready to hit the road!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many people that I’m grateful to for having helped me during the process of my thesis.

First, I’d like to thank my supervisor Marco Polo and the support you gave me not only in the duration of thesis but my time throughout the program. I enjoyed our conversations around the historical, social, and political context surrounding Canadian architecture; it’s a subject that will be forever interesting to me. You show full investment in your students’ projects and well-being, this support was invaluable for me. Thank you so much.

Thank you to my second reader Garth Norbraten, who is another fellow Saskatchewanian. I had so much fun bantering about Saskatchewan lore and I am thankful for the local insight you brought to my thesis.

Thank you to my program representative Cheryl Atkinson for the conversations during my milestones. And thank you to Paul Floerke for stepping in at the eleventh hour for your supervision in the winter.

For my family, thank you for scrounging around the house looking for old maps, license plates, and other things to mail to me.

Thank you to my classmates for being there with me for the last two years. I’m grateful for our friendship and am looking forward to exciting things to come. I would especially like to thank Christian, Anya, and Sam for the good conversation and for the time spent working together.

To Sarah and Anna, thank you for answering the many questions I had about the grasslands and wetlands ecology, I am so grateful for your knowledge and your unconditional support in the last year.

To the Jellicoe family, especially Colin, thank you for teaching me about the family farm and providing me with many photos of trucks, tools, and buildings.

Thank you to Rory, who sold me the blue Nissan at a good price, allowing me to travel through and document Saskatchewan in the summer of 2023.

Thank you to all of my friends who lent a helping hand; including Gabe, Tanya, Dale, Surath, Amy, Amanda, Murray, Billy, Alee, Julie, Nicole, Jessica M., Justin, Arnel, Shane, and Emmy. I couldn’t have done it without you.

List of Figures

Figure 1: Map of Canada

Source: By author

Figure 2: Little house on the prairie

Source: By author

Figure 3: Driving in Saskatoon in the summer and winter

Source: By author

Figure 4: Saskatoon from the plane

Source: By author

Figure 5: Fields in Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 6: Driving past a field in Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 7: Wanuskewin Park

Source: By author

Figure 8: Sketch of Regina Beach

Source: By author

Figure 9: Sketch of Wanuskewin Park

Source: By author

Figure 10: Sketch of Saskatoon

Source: By author

Figure 11: Sketch of wild flowers in Cypress Hills

Source: By author

Figure 12: Sketch of prairie lilies

Source: By author

Figure 13: Sketch of flowers

Source: By author

Figure 14: Sketch of wild rye

Source: By author

Figure 15: Grassland ecozone and pothole region

Source: By author

Figure 16: Yellow headed blackbird, goose, bison, sandhill crane, cat tails

Source: By author

Figure 17: Traditional territories of Indigenous nations in Saskatchewan

Source: By author, synthesized from multiple sources

Figure 18: Aerial image of the grid in Saskatchewan

Source: Google maps. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.google.com/ maps/@49.5835733,-105.6209687,33479m/ data=!3m1!1e3?authuser=0&entry=ttu.

Figure 19: Dominion Land Survey over MB, SK, AB, BC

Source: Topographical Survey of Canada. 1929 Index to Townships in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. 2006. https://d3d0lqu00lnqvz.cloudfront.net/ media/media/1edab983-1db2-4032-8b34f6d48d5238da.jpg.

Figure 20: A township split into 36 sections

Source: McKercher, Robert B., and Bertram Wolfe. “Understanding Western Canada’s Dominion Land Survey System.” Unversity of Saskatchewan, 1986. 4

Figure 21: Sections within a township owned by the Canadian government, railway companies, HBC, and SK school board

Source: McKercher, Robert B., and Bertram Wolfe. “Understanding Western Canada’s Dominion Land Survey System.” Unversity of Saskatchewan, 1986. 10

Figure 22: Photo of township survey of Saskatoon from 1882

Source: The Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Regina, SK. Photo by Author

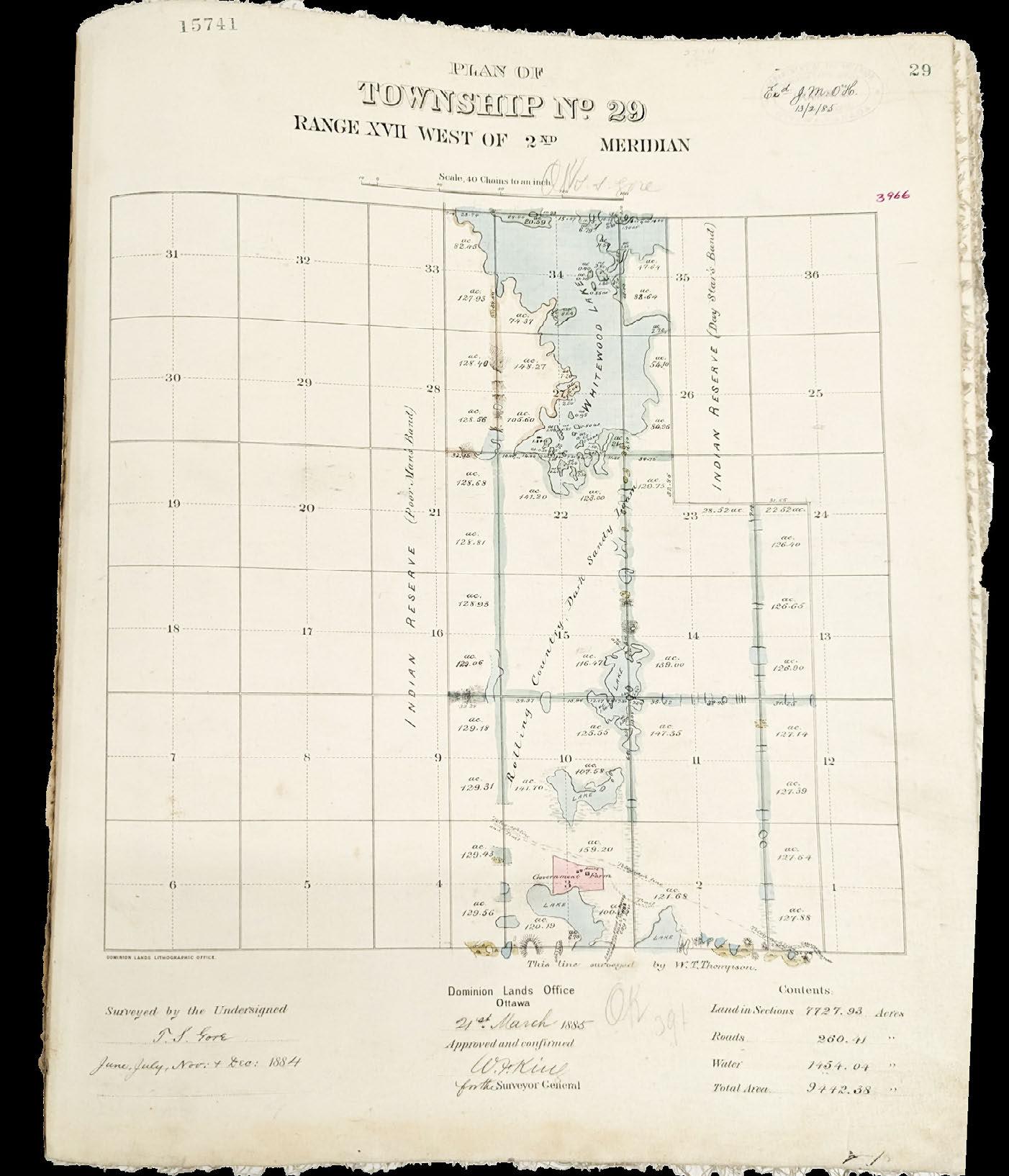

Figure 23: Photo of township survey from 1885

Source: The Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Regina, SK. Photo by Author

Figure 24: Centuriation map of Cadastre d’Arausio circa 77AD

Source: JPS68. Cadastre of Arausio. 2011. https://upload.wikimedia.org/ wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/ Cadastre_d%27Arausio.jpg/636pxCadastre_d%27Arausio.jpg?20110501204144.

Figure 25: 1912 Illustration from marketing pamphlet issued by the Authority of the Minister of the Interior, Ottawa Canada

Source: The Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Regina, SK. Photo by author

Figure 26: Photos of marketing pamphlets issued in 1911 and 1912 by the government to promote “free land” to potential settlers

Source: The Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Regina, SK. Photo by author

Figure 27: Wild nature depicted as witches. Albrecht Durer, The Four Witches, 1497.

Source: Agrest, Diana. Architecture of Nature: Nature of Architecture. First edition. Novato, CA: Applied Research and Design Publishing, 2021. 261

Figure 28: Photo of township survey that includes reserves from 1882

Source: The Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Regina, SK. Photo by author

Figure 29: Photo of township survey that includes reserves from 1885

Source: The Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Regina, SK. Photo by author

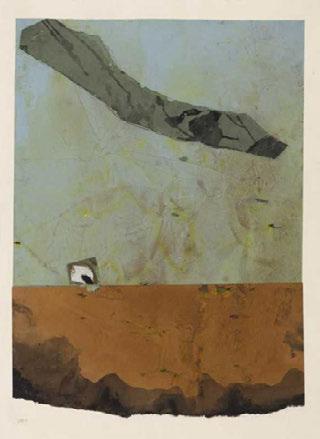

Figure 30: Interpretation of the prairies if everything that happened on the ground was reflected in the sky

Source: By author

Figure 31: Floating images of abandoned things in Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 32: Photo of abandoned grain elevator

Source: By author

Figure 33: Floating images of abandoned things in Saskatchewan

Source: Colin Jellicoe

Figure 34: Jellicoe family farm from 1923 to 2023

Source: By author

Figure 35: John Deere ad from 1837

Source: John Deere - First Plow ~ Where it All Started. Accessed April 22, 2024. http://www. esnarf.com/1291a.jpg.

Figure 36: John Deere ad from 1913

Source: 2011. 1026 - JOHN DEERE PLOW CO. METAL ADVERTISING SIGN - 12.5 X 16. https://www.icollector.com/1026-JOHNDEERE-PLOW-CO-METAL-ADVERTISINGSIGN-12-5-X-16_i10652255.

Figure 37: John Deere ad from 1935

Source: John Deere Tractor, Model D from 1935. Accessed April 22, 2024. https:// johnnypopper.com/jdgifs/dadver.jpg.

Figure 38: John Deere ad from 1974

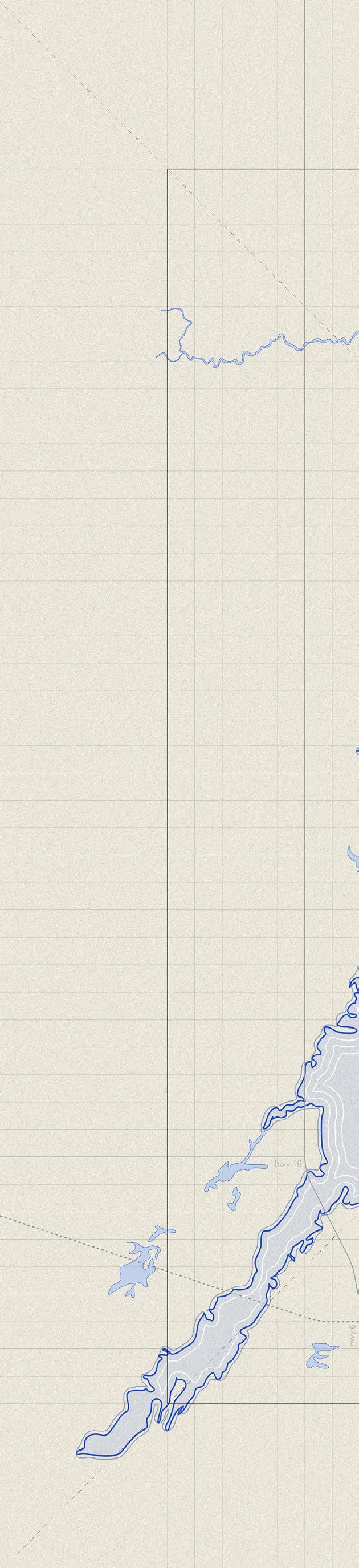

Source: John Deere advertisement 1974, Nothing runs like a Deere . Accessed April 22, 2024. https://blog.machinefinder.com/wpcontent/uploads/2012/01/1974-john-deere110-112-140-lawn-tractors-ad_260737186347. jpeg.

Figure 39: John Deere ad from 2024

Source: John Deere Catalog from 2024. 2023. https://lirp.cdn-website. com/ea12c005/dms3rep/multi/opt/ Front+cover+2024+catalog-1920w.png.

Figure 40: Shipping container yard

Source: Shipping container yard. 2021. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/ articles/supply-chain-snarls-leave-southerncalifornia-swamped-in-empty-shippingcontainers-11637928000.

Figure 41: Prairie landscape as yard of machines

Source: By author

Figure 42: Automated landscape by 2030

Source: Future of Farming. John Deere. https://www.deere.co.uk/en/agriculture/futureof-farming/. Adapted by author

Figure 43: Gusts of wind make the windchimes sing. Gordon Reeve, The Coming Spring, 2018

Source: By author

Figure 44: Big big snowman in the city

Source: By author

Figure 45: Snow angels

Source: By author

Figure 46: Joni Mitchell’s album cover set in the riverbank of Saskatoon and she is holding a prairie lily. Joni Mitchell, Clouds, 1969

Source: Reprise Records. Clouds (Joni Mitchell album). 2021. https://upload. wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/7/72/Joni_Clouds. jpg.

Figure 47: Agnes Martin, untitled, 1965

Source: Untitled. Whitney Museum of American Art. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://whitney.org/collection/works/37887 .

Figure 48: Corner Gas Season 1, Episode 1

Opening Scene

Source: “Ruby Reborn.” Corner Gas. CTV, January 22, 2004. https://www.ctv.ca/shows/ corner-gas/ruby-reborn-s1e1.

Figure 49: Corner Gas set

Source: Corner Gas set. Corner Gas. Accessed April 15, 2023. https://www.cornergas.com/ walkingtour/vsspi/WS%20corner%20gas%20. png.

Figure 50: Dorothy Knowles, Reeds and Wildflowers, 1990.

Source: Remai Modern Gallery, Saskatoon, SK. Photo by author

Figure 51: William Perehudoff, La Loche No. 9, 1973.

Source: Perehudoff, William. LA Loche No. 9, 1973. Artnet. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.artnet.com/artists/williamperehudoff/la-loche-no-9-_847UibjtwGu_ MGGR-Vd1w2.

Figure 52: Otto Rogers, Slow Moving Clouds, 2015.

Source: Rogers, Otto. Slow Moving Cloud, 2015. Accessed August 9, 2023. https:// oenogallery.com/artists/otto-rogers/art/slowmoving-cloud.

Figure 53: Eli Borenstein, Hexaplane Structurist

Relief No. 2 (Arctic Series),1995-1998.

Source: Bornstein, Eli. Hexaplane Structurist

Relief No. 2 (Arctic Series), 1995-1998. Galleries West. Accessed April 30, 2024. https://www.gallerieswest.ca/magazine/ books/eli-bornstein/.

Figure 54: Marily Levine, John’s Mountie Boots, 1973.

Source: Levine, Marilyn. John’s Mountie Boots, 1973. Gathie Falk. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/gathiefalk/key-works/eight-red-boots/.

Figure 55: Victor Cicansky, Compost Shovel, 2020

Source: Cicansky, Victor. Compost Shovel, 2020. Slate Fine Art Gallery. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://images. squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ba1 f575016e192aae50960/1633635675294AHIBTDHMFH6NLK8DTJZ6/109_cic_ compostshovel+2.jpg?format=2500w.

Figure 56: Joe Fafard, Saskatoon (AP III), 2007

Source: Fafard, Joseph. Saskatoon (AP III)

2007. University of Regina. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www2.uregina.ca/president/ art/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/17-009-061new-1024x683.jpg.

Figure 57: David Thauberger, Product Positioning, 2021

Source: David, Thauberger. Product Placement, 2021. David Thauberger. Accessed April 30, 2024. https://www. davidthauberger.com/recentworks/images/dtproductpositioning21_a1.jpg.

Figure 58: Photograph of exhibit. Meryl McMaster, bloodline, 2023.

Source: Remai Modern Gallery, Saskatoon, SK. Photo by author

Figure 59: Laure Prouvost, Oma-je, 2023.

Source: Remai Modern Gallery, Saskatoon, SK. Photo by author

Figure 60: One of the many mobiles at the exhibit. Laure Prouvost, Oma-je, 2023.

Source: Remai Modern Gallery, Saskatoon, SK. Photo by author

Figure 61: Lyle XOX’s sculptural head piece using found objects. Lyle Reimer, 40 Love, 2023.

Source: Reimer, Lyle. Head piece sculpture by Lyle XOX on Instagram post. June 2023. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/ CtUG98zLOmc/.

Figure 62: David Stonhouse, Powerboxes, 2020

Source: Stonhouse, David. Powerboxes, 2020. 2020. David Stonhouse. https://www. davidstonhouse.com/powerboxes-2020/ mtzpajegpeup8pvwhv4k6aqo2qjiwc.

Figure 63: Ric Pollock, Hi-Ho Silver, 2014

Source: Pollock, Ric, and Judy Wood. Hi Ho Silver. 2014. Fineartamerica. https://images. fineartamerica.com/images-medium-large-5/ hi-ho-silver-ric-pollock.jpg.

Figure 64: Kehan Bought 100,000 Googly Eyes

Source: By author

Figure 65: Wanuskewin cyanotypes

Source: By author

Figure 66: Abstract investigation on pothole wetlands and sod houses

Source: By author

Figure 67: Frank Lloyd Wright, Martin House, Buffalo, NY, 1904.

Source: By author

Figure 68: Clifford Wiens, Heating and Cooling Plant, University of Regina, Regina, SK, 1967.

Source: By author

Figure 69: Clifford Wiens, Silton Chapel, Silton, SK, 1969.

Source: Wiens, Clifford. Project by Project: Architectural Memoirs. Vancouver: Wiens Pub., 2013. 208

Figure 70: Silton Chapel circa. 2023. Clifford Wiens, Silton Chapel, Silton, SK, 1969.

Source: wcm_league. Demolished Silton Chapel. 2023. Instagram. https://www. instagram.com/p/CwiNKIiOtlg/?img_index=2.

Figure 71: Clifford Wiens, Silton Chapel, Silton, SK, 1969.

Source: Wiens, Clifford. Project by Project: Architectural Memoirs. Vancouver: Wiens Pub., 2013. 210

Figure 72: Entry to visitor centre framing views of rolling hills. Clifford Wiens, Trans-Canada Highway Campground, Maple Creek, SK, 1964.

Source: Wiens, Clifford. Project by Project: Architectural Memoirs. Vancouver: Wiens Pub., 2013. 148

Figure 73: Clifford Wiens, Trans-Canada Highway Campground, Maple Creek, SK, 1964.

Source: Wiens, Clifford. Project by Project: Architectural Memoirs. Vancouver: Wiens Pub., 2013. 151

Figure 74: Donald Judd, 15 untitled works in concrete, Marfa, Texas, 1980-1984.

Source: Judd, Donald. 15 untitled works in concrete, 1980-1984. Chinati. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://chinati.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/06/9330_Chinati_ FO_043lowres-1024x681.jpg. Architectural Memoirs. Vancouver: Wiens Pub., 2013. 210

Figure 75: Pin from Expo ‘86 representing Saskatchewan’s grain elevator pavillion

Source: By author

Figure 76: Grain elevator in Rosthern SK

Source: By author

Figure 77: Deconstructed grain elevator in Kenaston SK

Source: By author

Figure 78: Exposed sod wall at the Addison sod house circa 2023

Source: By author

Figure 79: Addison House covered in vines in 1929

Source: Chandler, Graham. Vines adorn the Addison Sod House in 1929. 2010. Legion. https://legionmagazine.com/the-last-of-thesoddies/.

Figure 80: Addison House clad in vinyl in 2023

Source: By author

Figure 81: David’s haybale house under construction

Source: David Kucher

Figure 82: Sketch of tipi construction

Source: Jefferys, Charles W. Plains Indians Lodge or Tipi, 1942. CW Jeffereys. Accessed March 12, 2023. https://www.cwjefferys.ca/ plains-indians-lodge-or-tipi.

Figure 83: Tipi as travois

Source: Miller, Gordon. horse-drawn travois was adapted from the earlier travois pulled by dogs. 2006. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/ article/travois.

Figure 84: Tipis in the prairie

Source: Horetsky, Charles. Cree Camp on the prairie, south of Vermilion, Sept 1871. 2005. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:CreeCamp1871.jpg.

Figure 85: Nugent Studio from driveway. Clifford Wiens, Nugent Studio, Lumsden, SK, 1959-1960.

Source: By author

Figure 86: Interior walls of bronze casting studio. Clifford Wiens, Nugent Studio, Lumsden, SK, 1959-1960.

Source: By author

Figure 87: John Nugent sculptures on the property

Source: By author

Figure 88: Concrete sewer windows at candle making studio. Clifford Wiens, Nugent Studio, Lumsden, SK, 1959-1960.

Source: By author

Figure 89: William Kurelek, The Painter, 1974

Source: Kurelek, William, and Art Gallery of Ontario. The Painter, 1974. Art Canada Institute. Accessed March 24, 2023. https:// www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/william-kurelek/keyworks/the-painter/.

Figure 90: RV campers in Cypress Hills SK

Source: By author

Figure 91: Dallegret, François, Transportable Standard-of-Living Package, 1965. Drawing for Reyner Banham’s “A Home is Not a House”, Art in America 2, 1965.

Source: Dallegret, François, and Reyner Banham. A Home is Not a House, 1965. 2011. Socks. https://socks-studio.com/2011/10/31/ francois-dallegret-and-reyner-banham-ahome-is-not-a-house-1965/.

Figure 92: Transparent plastic bubble dome inflated by air-conditioning output with Standard-Of-Living Package inside. Dallegret, François, The Environment Bubble, 1965. Drawing for Reyner Banham’s “A Home is Not a House”, Art in America 2, 1965.

Source: Dallegret, François, and Reyner Banham. Un-House. Transportable Standardof-Living Package, 1965. 2011. Socks. https:// socks-studio.com/2011/10/31/francoisdallegret-and-reyner-banham-a-home-is-not-ahouse-1965/.

Figure 93: Dallegret, François, Trailmaster GTO Transcontinental, 1965. Drawing for Reyner Banham’s “A Home is Not a House”, Art in America 2, 1965.

Source: Dallegret, François, and Reyner Banham. Trailmaster GTO, 1965. 2011. Socks. https://socks-studio.com/2011/10/31/francoisdallegret-and-reyner-banham-a-home-is-not-ahouse-1965/.

Figure 94: Various car oriented signs and objects in Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 95: Photos of signs in Las Vegas from LFLV

Source: Venturi, Robert, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour. Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form. 17th print. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2000. 62-63

Figure 96: Section indicating 5km radius extent of horizon

Source: By author

Figure 97: Objective landscape vs. thoroughfare landscape

Source: By author

Figure 98: Plan indicating 5km radius extent of horizon

Source: By author

Figure 99: Viewing extent expands with mobility

Source: By author

Figure 100: Phenomenological drawing of driving

Source: By author

Figure 101: Prairie landscape “moving image”

Source: By author

Figure 102: Frames from videos of driving in Canadian landscapes overlayed into single images

Source: By author

Figure 103: Windows from the Nugent Studio framing the Qu’Appelle Valley. Clifford Wiens, Nugent Studio, Lumsden, SK, 1959-1960.

Source: By author

Figure 104: Madelon Vriesendorp, Flagrant Délit, 1978. First Edition Cover for Rem Koolhaas’ Delirious New York, Oxford University Press, 1978

Source: Vriesendorp, Madelon, and Rem Koolhaas. Flagrant Délit, 1975. Canadian Centre for Architecture. Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/search/ details/collection/object/309530.

Figure 105: Madelon Vriesendorp, The City of the Captive Globe, 1978. Drawing for Rem Koolhaas’ Delirious New York, Oxford University Press, 1978

Source: Koolhaas, Rem. Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. New ed.

New York: The Monacelli Press, 1994. 295

Figure 106: Series of drawings representing investigating fragments of the whole

Source: By author

Figure 107: Sketches of archetypes of Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 108: Richard Buckminster Fuller. Dymaxion Map, 1943.

Source: Buckminster Fuller’s Map of the World, 1943. 2017. Open Culture. https:// www.openculture.com/2017/02/buckminsterfullers-map-of-the-world.html.

Figure 109: Saskatchewan map with major organizational systems

Source: By author

Figure 110: Abstracted map of Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 111: Interface of saskfarmlistings.ca

Source: Interface of saskfarmlistings.ca.

Accessed November 28, 2024. https:// saskfarmlistings.ca

Figure 112: Example of real estate listing from saskfarmlistings.ca

Source: Interface of saskfarmlistings.ca.

Accessed November 28, 2024. https:// saskfarmlistings.ca

Figure 113: Farms for sale, FFS 1 : T13R23W2

Source: By author

Figure 114: Farms for sale, FFS 2 : T8R16W2

Source: By author

Figure 115: Farms for sale, FFS 3 : T26R10W3

Source: By author

Figure 116: Farms for sale, FFS 4 : T8R25W2

Source: By author

Figure 117: Farms for sale, FFS 5 : T33R2W2

Source: By author

Figure 118: Farms for sale, FFS 6 : T50R25W2

Source: By author

Figure 119: Farms for sale, FFS 7 : 10R15W3

Source: By author

Figure 120: Farms for sale, FFS 8 : T8R14W2

Source: By author

Figure 121: Farms for sale, FFS 9 : T24R11W2

Source: By author

Figure 122: Farms for sale, FFS 10 : T23R24W3

Source: By author

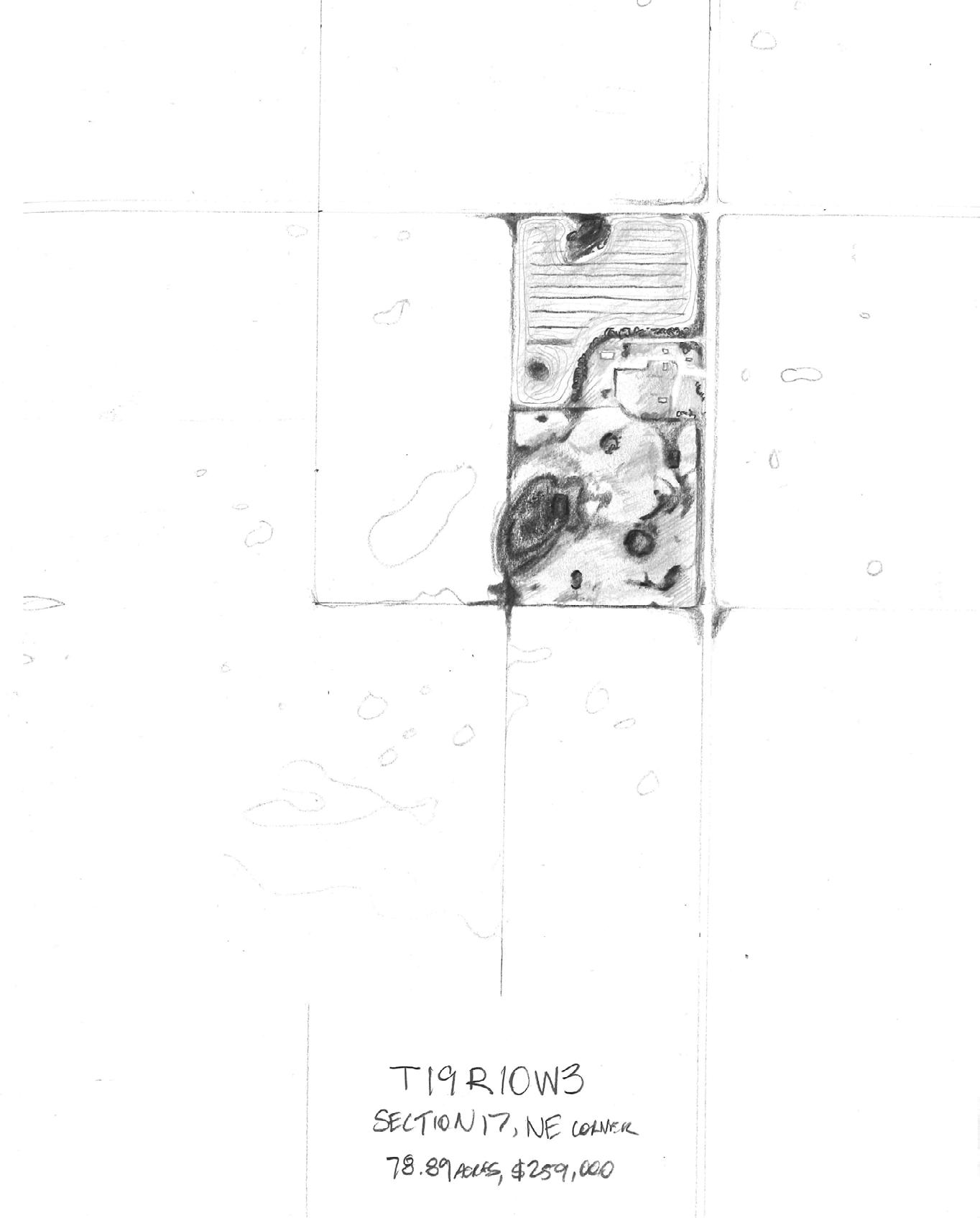

Figure 123: Farms for sale, FFS 11 : T29R10W2

Source: By author

Figure 124: Farms for sale, FFS 12 : T49R10W2

Source: By author

Figure 125: Farms for sale, FFS 13 : T14R19W3

Source: By author

Figure 126: Farms for sale, FFS 14 : T6R1W2

Source: By author

Figure 127: Farms for sale, FFS 15 : T35R22W2

Source: By author

Figure 128: Farms for sale, FFS 16 : T19R10W3

Source: By author

Figure 129: Farms for sale, FFS 17 : T17R12W3

Source: By author

Figure 130: Farms for sale, FFS 18 : T17R31W1

Source: By author

Figure 131: Farms for sale, FFS 1 to FFS 18

Source: By author

Figure 132: In the back seat of my dad’s truck, driving to Regina

Source: By author

Figure 133: Series of photos driving across the prairies

Source: By author

Figure 134: Saskatchewan license plate

Source: By author

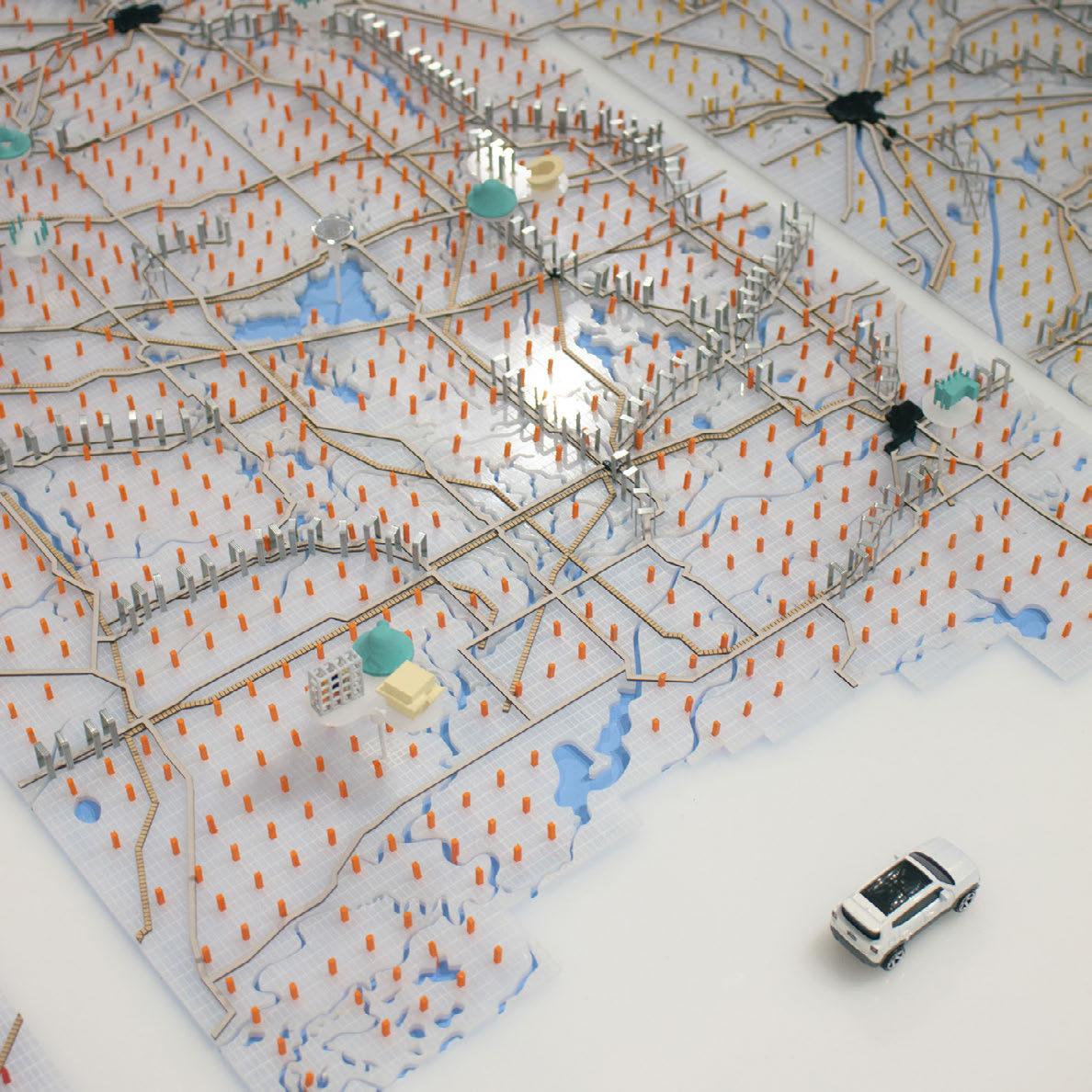

Figure 135: Saskatchewan site model with toy car

Source: By author

Figure 136: Map of the Land of Living Skies

Road Trip

Source: By author

Figure 137: Table of fragments of investigation in relation to the four lenses of Saskatchewan

Source: By author

Figure 138: Detail, site model of the Land of Living Skies Road Trip

Source: By author

Figure 139: Sky Everwhere concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 140: At the centre dock of Big Quill Lake

Source: By author

Figure 141: Grasslands & Gophers concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 142: Walking towards the centre of a remediated grassland site

Source: By author

Figure 143: Life of Wetlands : Conserved wetland concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 144: View of observation deck for an existing wetland being conserved

Source: By author

Figure 145: Model of intervention for existing wetland

Source: By author

Figure 146: Site model of wetland with interventions

Source: By author

Figure 147: Model of intervention for existing wetland

Source: By author

Figure 148: Sketch of existing condition of wetland

Source: By author

Figure 149: Model of intervention for remediated wetland

Source: By author

Figure 150: Life of Wetlands : Reconstructed concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 151: View of observation deck for a reconstructed wetland, forming the new bank

Source: By author

Figure 152: Ghost of the CPR concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 153: Driving down a highway, at the intersection where two abandoned railway lines meet

Source: By author

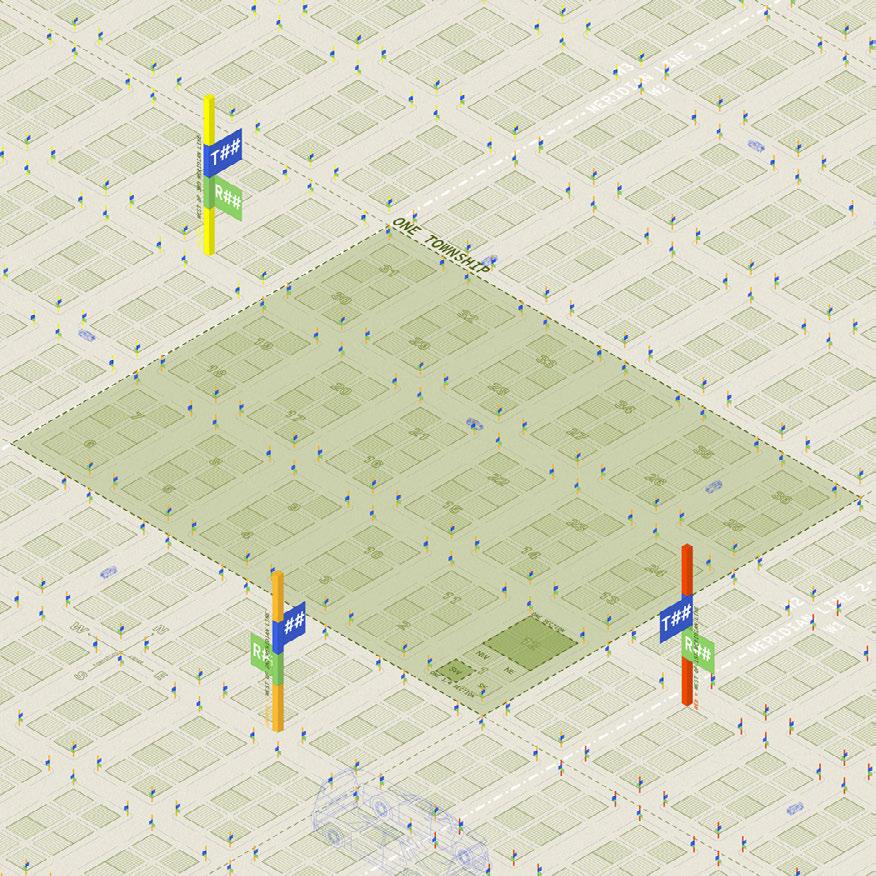

Figure 154: The TRW Grid concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 155: Driving down a gravel road at the intersection of T16R29W2, T15R30W2, T16R29W2, and T16R30W2

Source: By author

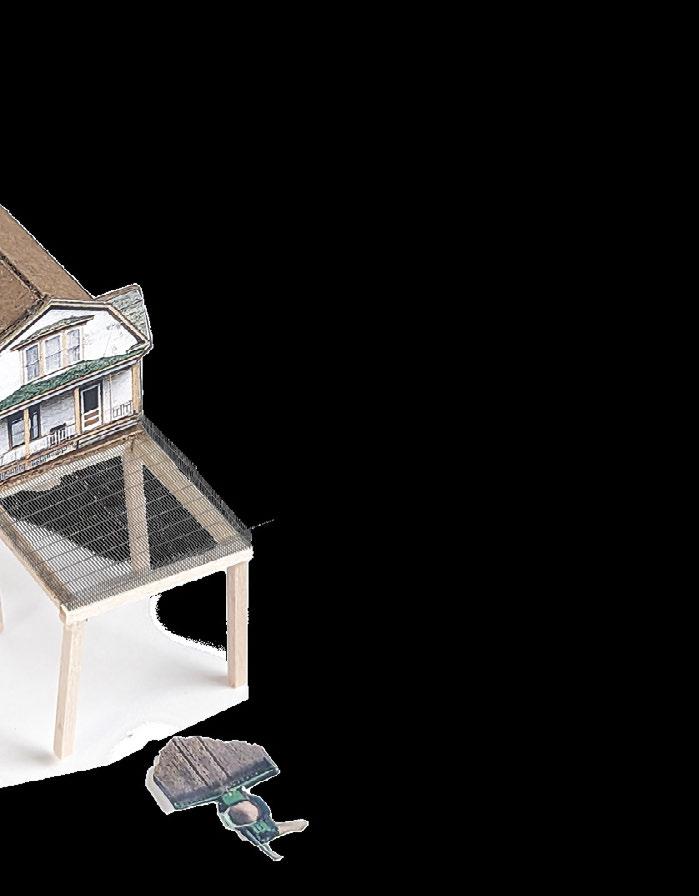

Figure 156: Home Sweet Home concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 157: Models and sketches of catalogue and mobile homes

Source: By author

Figure 158: Oh look! That house is in the air!

Source: By author

Figure 159: Cage of Junk concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 160: Model and sketches of Cage of Junk

Source: By author

Figure 161: Driving past a large cage filled with lots of stuff

Source: By author

Figure 162: John Deere Tourism concept drawing

Source: By author

Figure 163: Sketches analyzing combine

Source: By author

Figure 164: Physical model of John Deere camper

Source: By author

Figure 165: Collage of Dustin Bezulgy’s Youtube video

Source: Bezulgy, David. “Big Saskatchewan Wheat Harvest.” YouTube, September 24, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7kFnLpHgw&ab_channel=DustinBezugly. Collage by author

Figure 166: Tourist just arriving at his campsite for the night

Source: By author

Figure 167: Map showing the interventions of the Land of Living Skies Road Trip

Source: By author

Figure 168: Snapshots from the Land of Living Skies Road Trip

Source: By author

Figure 169: Detail of site model

Source: By author

Figure 170: Detail of site model

Source: By author

Figure 171: Pilot episode of the Land of Living Skies Road Trip

Source: By author

Figure 172: Saskatchewan from the sky

Source: By author

Figure 173: Detail of map for the Land of Living Skies Road Trip

Source: By author

Figure 174: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 175: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 176: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 177: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 178: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 179: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 180: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

Figure 181: Photo of exhibit

Source: By author

<

1 Climenhaga, Christy. CBC News, “Why the Prairies Get More Sun than the Rest of Canada | CBC News,” CBC, December 29, 2021, https://www. cbc.ca/news/canada/ edmonton/sun-shines-onprairies-1.6287193.

Established in 1905, Saskatchewan is one of three Prairie Provinces in Canada, situated between Alberta and Manitoba. The province has a diverse landscape including the Canadian Shield and the Boreal forest in the northern area, but the landscape that it’s known for is its prairies. Unlike other provinces which have prominent landscape features such as the Rocky Mountains, or the Great Lakes, or one of the oceans, the Saskatchewan prairie landscape is distinct because of its simple topography. Its “lack of” landscape becomes its monumental feature as its defining element becomes the horizon, which divides the ground and a panoramic sky.

The prairies are a vast and flat landscape that extends for hundreds of kilometers. The area is generally sparse with trees other than the occasional speckled clumps of bush or the planted windrows. A flat landscape makes for a windy place, which is shown in the permanently skewed trees or twisted abandoned farms, or the six foot tall snowdrifts on the side of buildings. The winters are very cold, reaching -40°C with the wind chill at least once a year and the summers are very hot, typically settling around 40°C. Although the temperatures are extreme, its dry climate makes for many sunny days throughout the year – enough to be called the sunniest place in Canada.1

The sky is fundamental to the experience of living in the prairies. Sometimes it’s a remarkable sight such as northern lights or an awesome lightning storm, but even on a daily basis it is prevalent to the landscape. In the summer, the sky has picturesque clouds as one might see in romantic oil paintings. In the winter, the low sun casts extra-long shadows; the sky is usually clear and bright, fading from blue to white at the horizon and blending into the field of white snow. Sunsets present a gradient of colours, from orange to pink to purple to blue, casting a filtered hue everywhere the light can reach. Saskatchewan is proud of its dynamic skies – so much so that the provincial license plate slogan is “Land of Living Skies”.

Through the hands of the Canadian government, the prairie landscape was changed within a few decades with the use of the Dominion Land Act, a grid system to divide the land to become farms. Used on a massive scale, the grid transformed Saskatchewan into the breadbasket of Canada, making up over 40% of Canada’s cropland.2 During this development, the grid was simultaneously used as a tool to suppress the Great Plains Grasslands ecology and the indigenous people that inhabited it for thousands of years before settlement. Since settlement and confederation, it’s now also home to people from all around the world. Conceptualized as an organizational system for land, the massive grid then manifested itself in the form of roads, resulting in Saskatchewan having the most roads of any province in the country.

Saskatchewan has never been at the heart of architectural innovation in Canada for many reasons. Because the province has never had a school of architecture, it does not have a reciprocal relationship between pedagogy and practice; prospective students need to leave the province for education and tend to stay away after graduation. The shocking truth is that for a province of almost 1.2 million people, there are only 94 resident architects.3 But now that metropolitan cities are presenting problems of housing affordability, less populated places such as Saskatchewan offer a new opportunity. Architecture has the possibility of tapping into a culture to which it is not yet contributing.

So what makes a distinctly Saskatchewan architecture?

Other than the vernacular architecture and the work of a few modern architects, very little architecture is representative of the Saskatchewan prairies. To gain an understanding of the province, architecture can look at other media such as art, music, literature, TV, etc. Whether it is high art, pop art, or people’s personal stories, a common thread

>

2 Statistics Canada Government of Canada, “Saskatchewan Continues to Live up to the Title of Breadbasket of Canada,” June 15, 2022, https:// www150.statcan.gc.ca/ n1/pub/96-325-x/2021001/ article/00008-eng.htm.

3 “Saskatchewan Association of Architects: 2022 Annual Report” (Saskatoon, SK: Saskatchewan Association of Architects, May 6, 2023).

that connects work coming out of Saskatchewan is its unique landscape. Work that represents a response to the landscape includes Eli Bornstein’s abstract sculptures that investigate the play of light, the recreation of a bison by Joe Fafard, the construction of a tipi, the architecture of Clifford Wiens, or even the songs of Joni Mitchell.

The sparse landscape also coincides with a scarcity of resources resulting in people developing a frugal attitude. Making things with available found resources first started as a necessity to survive, has now turned into a cultural way of thinking and creating. Found objects become part of the tectonics of making in Saskatchewan. Then, as an existing architecture that places itself in the history of the gridded land, the car becomes of interest. When driving through the province, this talisman of North American culture epitomizes the experience of the prairie landscape.

A future Saskatchewan architecture is one that recognizes the change in landscape through the use of the grid, and an understanding of the multiple histories of the province. By looking at history and other practices such as art and pop culture, architecture learns to develop a methodology that reflects prairie sensibilities. Architecture can then engage in the cultural discourse of Saskatchewan, becoming a medium of education to enhance our understanding of place.

CHAPTER 1 Four Lenses

Figure 6: Driving past a field in SaskatchewanLens 1: Grasslands, Wetlands, & More

“A prairie requests the favour of your closer attention. It does not divulge itself to mere passerby.”4 – Candace Savage from Prairie: a Natural History of the Heart of North America

Before settlers arrived in the late 19th and early 20th century, for thousands of years the landscape consisted mostly of Great Plains Grasslands.5 The agrarian shift during settlement was the most significant change in the prairie landscape since the last ice age that created the grasslands. About 1.2 million years ago, a vast slab of ice scraped over the area, creating the flat landscape; then about 18,000 years ago, its receding proglacial lakes deposited biological organisms and carbon trapped in the dirt, creating the rich soil that formed the grasslands and wetlands.6 Grasslands can be found in every continent except Antarctica, if there was no human intervention, it would form about 46 million km2 in area – covering over one third of the world’s land area as one of the largest terrestrial biomes.7

In her book Prairie: A Natural History of the Heart of North America, Candace Savage quotes Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, the first known European to come across a grasslands landscape in 1540 in what is now known as New Mexico,

“I reached some plains so vast, that I did not find their limit anywhere I went … a wilderness in which nothing grew, except for very small plants.”8

In reality, the Grasslands in North America are very diverse, encapsulating fifteen ecoregions; in Saskatchewan alone the regions include the Aspen Parkland, Northern Mixed Grasslands, and the Northwestern Short/Mixed Grasslands.9 Each ecoregion has its own mix of flora and fauna of short and tall grasses, small trees or bushes, and flowers.10 When I visited Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park in July, the landscape ranged from tall grass to meadows filled with wildflowers.

Chapter 1 : Four Lenses

Superimposed on the grasslands ecology are wetlands, each of which acts as a microecosystem on top of the prairie. Saskatchewan is part of the pothole region of the grasslands, which means the landscape was originally dotted with marshes, ponds, and lakes. Wetlands are ephemeral systems, constantly changing with the flow of precipitation depending on the season and the year. Depending on the size of the wetland, it’s common for a wetland to be saturated during the spring from the snowmelt and completely dry by mid-summer or even a few weeks later. The wetlands are filled with wildlife including insects, songbirds, waterfowl, and mammals; they are incredibly important for the migration of animals during the spring.

During Coronado’s exploration in the 16th century, he reported the sighting of another animal on the landscape,

“I found such a quantity of cows … that it is impossible to number them, for while I was journeying through these plains, until I returned to where I first found them, there was not a day that I lost sight of them.”11

These cows he describes are the bison that were a crucial animal to the indigenous people that resided in the grasslands. The bison were essential to the life of the indigenous people as it was a source of shelter, clothing and food. For thousands of years before settlement, the land of what is now defined as Saskatchewan was shared by many nations. It is the traditional territory of the Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota (Assiniboine), Dakota and Lakota (Sioux), Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan), Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla, Ĩyãħé Nakón mąkóce (Stoney), Niitsítpiis-stahkoii (Blackfoot / Niitsítapi) and the Métis. Indigenous people and their traditional ways of living were displaced during the settlement period and the development of the agricultural landscape that we see today.

10 Ibid.,17-18

11 Ibid., 5

Chapter 1 : Four Lenses

Figure 17: Traditional territories of Indigenous nations in Saskatchewan

TRADITIONAL TERRITORIES

Ochéthi Šakówin Sioux

Assiniboine

Iyãné Nakón makóce (Stoney)

Niitsítpiis-stahkoii (Blackfoot / Niitsítapi)

Anishinabewaki

Cree

Dënéndeh

Denendeh (Dënësułinë Nëné)

Michif Piyii (Métis)

GOV’T IMPLEMENTED BORDERS

Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla Treaty Borders

Indian Act First Nations Reserves

FNLMA - Operational

FNLMA - Developmental

Lens 2: Industrial Landscape

Establishing the Grid

The Canadian government implemented the Dominion Land Survey and Dominion Land Act in 1871 and 1872 to bring settlers into the Prairies from all across Europe and Eastern Canada.12 During this process of settlement, the government worked hard to remove indigenous people and their culture. Along with many other political efforts and systems such as residential schools, the government caused the death of many indigenous people by changing the grasslands into agricultural land and purposely trying to extirpate the bison. The change also caused the extinction of many animals, including the Plains Wolves, Plains Grizzlies, Plains Elk, Plains Bighorn Sheep, and free-ranging Plains Bison.13

Before the creation of the Prairie Provinces, the area was known as Rupert’s Land, which was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company. It became part of Canada in 1870 as part of the North-West Territories, a huge portion of Canada. The following year, the government started work on the Dominion Land Survey, which saw an elaborate grid system placed over what are now British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. The survey covers a total of about 178 million acres of land, and is said to be the largest survey using a single grid done in the entire world.14 The government had two goals during this time, first to build the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) - a railway that would traverse the entire country from east to west; and second to populate the prairies and to make them productive for agriculture. The Dominion Land Survey and Dominion Land Act made both of these goals a reality.15

The Dominion Land Survey grid divides the land from the scale of the entirety of the provinces down to one eighth mile by one eighth mile. At the largest scale, the four western provinces were divided using seven longitudinal lines called “meridians”. Saskatchewan is situated on the fourth meridian on its western border and goes just past the second meridian on its eastern border. Between the meridian lines, the land is then divided with a six mile by six mile grid where cells are marked longitudinally as “townships” and

12 Robert B. McKercher and Bertram Wolfe, “Understanding Western Canada’s Dominion Land Survey System” (Unversity of Saskatchewan, 1986).

13 Savage and Williams, Prairie. 19

14 Dave Obee, Back to the Land: A Genealogical Guide to Finding Farms on the Canadian Prairies, 2nd ed (Victoria, BC: D. Obee, 2003). 2

15 McKercher and Wolfe, “Understanding Western Canada’s Dominion Land Survey System.” 3 Figure 18: Aerial image of the grid in Saskatchewan

Chapter 1 : Four Lenses

23

16 McKercher and Wolfe.

2-4

17 Ibid., 10

latitudinally as “ranges”, creating a matrix system to reference each cell; each cell is also called a “township”, which may cause confusion. Next, each township is divided into 36 one mile by one mile squares, called a “section” of 640 acres, each named with a number from one to 36. Then, each section is divided into four quarters, each cell a half mile by half mile, equally to 160 acres called a “quarter section”. This is the typical parcel of land that would be bought or given away to settlers. The divisions continue from quarter sections into “legal subdivisions” and smaller still into “quarter of legal subdivisions”.16

The ownership of the land was shared by the government of Canada under the policies of the Dominion Land Act, the railways, the provincial school board, and the Hudson’s Bay Company. The land is divided based on the sections of a township: The DLA owns 16 sections to be given away to homesteaders, the school board owns sections 11 and 29, the Hudson’s Bay Company owned section 8 and almost all of section 26, and the rest went to the railways.17 The land owned by the railways, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the school boards were sold to pay off construction debts or make profit. But the land owned by the government was given away through policies of the Dominion Land Act, where each settler would be given a quarter section for a $10 administration fee if they could build a shelter and make the land productive within three years.

The point of the grid system was so it could be copied across the landscape and provide an easy way to describe every section of the land. When visiting the archive, each township can be found on a reference map that then leads you to a township reference book that then leads to a township survey drawing. For example, to find the survey drawing of Saskatoon, I found that it is ‘west of the Third Meridian’, ‘township 36”, and ‘range five’.

The reference book would then tell me that the survey drawing is in Volume 17 on pages 77, 78, and 79 (Figure 22).

The grid was simply placed over top of the existing landscape with no regard to the various ecological conditions - this is evident when looking at the archival surveys. The drawings are extremely sparse except around the lines of the grid, where we see lines cut through waterways and ignore topographical changes. The intervention of the Dominion Land Survey and the Dominion Land Act brought in a new demographic of people and completely recreated the prairie landscape. By creating Saskatchewan, the landscape shifted from its grasslands ecology to a gridded agricultural land.

Figure 19: Dominion Land Survey over MB, SK, AB, BC Figure 20: A township split into 36 sections

Figure 23: Photo of township survey from 1885

Figure 23: Photo of township survey from 1885

Origins of the Grid

Division of land into grids existed long before the surveys of North America. As early as the fourth century BC, the Roman Empire used a surveying practice called “centuriation” where the land was divided into squares.18 Using a survey tool called the groma, the squares would be created starting at the intersection of x and y axes, and the land would be divided into four squares of 20 x 20 actus, about 700m x 700m or 120 acres.19 Primarily, centuriation was applied in the context of acquiring colonies for the Romans.20 Colonies acted both as agricultural settlements and the site of Roman defense, so the land not only had to serve settlers, but had to be clumped together to better serve the military.21 As the Romans established more colonies and as their sphere of influence spread, the division of land by centuriation became common practice. Centuriated land can be found in Italy, France, Britain, Germany, Switzerland, Dalmatia, Greece, and North Africa.22

Like the Romans, the grid in Canada was also used to colonize conquered land, just at a much larger scale. Unlike the Romans who used the grid to establish a land base as a form of urbanization, the North American prairies’ use of the grid is closely tied to industrialization. In the prairies, industrializing did not involve building factories and machines to manufacture products; instead, the motive was to turn the land into an agricultural factory. To support the land factory, the grid is used as a machine and the people are used to operate and manufacture the products of wheat, oats, lentils, canola, barley, etc. Diana Agrest quotes feminist philosopher Sandra Harding in her essay “The Return of the Repressed: Nature”,

“As nature came to seem more like a machine, did not the machine come to seem more natural?”23

Nature (landscape) and the machine (industry) have merged together to become one in

24: Centuriation map of Cadastre d’Arausio circa 77AD

Figure 25: 1912 Illustration from marketing pamphlet issued by the Authority of the Minister of the Interior, Ottawa Canada > top to bottom

18 O.A.W Dilke, The Roman Land Surveyors: An Introduction to the Agrimensores (New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, Inc, 1971). 15, 133

19 Ibid., 15

20 Ibid., 16

21 Ibid., 15, 133

22 Ibid., 15, 133

23 Diana Agrest, “The Return of the Repressed: Nature,” in The Sex of Architecture, ed. Patricia Conway, Leslie Kane Weisman, and Diana Agrest (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 49–68. 51

24 Ibid., 50

25 Ibid., 50

26 Ibid., 50

27 Ibid., 51-52

the gridded plains of the prairies.

Canada’s development of the prairies in the late 1800s follows America’s prior development of the Midwest. At first, the American landscape was seen by Europeans as a virgin landscape. By denying the fact that the land was already inhabited by people and deeming it as “available”, it allowed the Europeans to take the land without it being perceived or accused of stealing it. At the same time, the city was seen as sinful and the pastoral ideal of rural life in a sublime landscape was preferred.24 In this context, the untouched wilderness was highly valued, so much so that in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature written in 1836, the landscape can be equated to God’s body of soul.25 However, conflicting with the pastoral ideal was the rise of the industrial revolution and the governmental prerogative to connect America coast to coast politically and economically. Thomas Jefferson recognized this in his Notes on Virginia, where he wrote about the great potential of the machine, and the reality that industry will alter an ideal rural life. Industrialization in America had two main pursuits; the push of the Midwestern frontier, and the construction of the locomotive which challenged the pastoral ideal.26 In Canadian history, the same narrative was replayed by John A. MacDonald’s government in the establishment of the Prairie Provinces and the creation of the CPR. The consequences of this process forced an ideological change that could accept both the machine and the sublime landscape,

“The locomotive crossing the virgin land ‘was like nothing seen before,’ and in order to reconcile the power of the machine with the beauty and peacefulness of the rural countryside, a discourse in which the power of the machine could be praised, a technological sublime, had to be developed … this philosophy, while neutralizing the contradiction of accepting the machine as a positive force, facilitated the destruction of the very landscape that represented the ideal of pastoralism”27

This change in ideology became a gateway to accepting the removal of the existing ecology as the destruction of the grasslands did not stop with the train. The original landscape continued to change as it was divided into millions of farm parcels in order to support the construction and use of the railway, and to ultimately support the national

The Grid as a Tool of Power

It is only recently that people (myself included) are becoming more educated about indigenous history and the extensively manipulative and harmful methods used to acquire Canada’s land. The field of architecture needs to recognize this history in its discourse. The Canadian government’s agenda of establishing the Prairies included the removal and assimilation of indigenous people and their traditional use of the land that existed for thousands of years. In the book The Inconvenient Indian, celebrated Indigenous author Thomas King writes,

“Land. If you understand nothing else about the history of Indians in North America, you need to understand that the question that really matters is the question of land.”28

To fulfill the cultural genocide against indigenous people, the Canadian government created the Indian Act in 1876, which was used to gain power over land and power over people.

In her essay “The Return of the Repressed: Nature” Diana Agrest describes the equivalence between nature and woman that has been depicted in philosophy, art, and science. Nature, gendered female, is described as passive, virgin, fertile, nurturing, and meant to be controlled and exploited. This is an ideology that believes that land needs to be worked and be productive; so the human, gendered male, has been made essential in the cultivation process. Just like procreation, man has the ability to activate and cultivate the sources of nature to be exploited.29 Man holds power because of this. In Canada, this ideology is played out in similar fashion; in his book 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act, Bob Joseph quotes Arthur Meighen, the Minister of the Interior and Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1918, economy.

“We would be only too glad to have the Indian use this land, if he would… but he will not cultivate this land, and we want to cultivate it; that is all.”30

There is an emphasis on the idea of productivity; if the land is not cultivated, it is not being put to good use even though uncultivated land is crucial for the habitat of animals and plants that have sustained indigenous people.31 Whether the cultivation process is good for the land or not is never questioned because the priority is to better man’s situation, so the land was exploited to do so. The analogy of nature being female is even more clear when it acts in “untamed” or “rebellious” ways in the events of storms, illness, and death, it is associated with witches, who need to be burned (Figure 27).32 Contrary to the misogynistic views towards nature seen in of Eurocentric cultures, Indigenous culture has a completely different relationship with land and women, who were respected and had very important roles in the community. So like witches, indigenous people were seen as threats because they did not comply with the agenda of the Canadian government therefore needed to be gotten rid of. Categorizing the power dynamics between “machine and man” vs. “nature and woman” is important to understand the people, motives, strategies, and tools required to dominate a landscape,

“The virgin earth was subdued by the machine for the exploitation of the goods of the earth in a race where industrialization and technological progress, backed by an ever-more rationalized view of the world, made the development of capitalism possible. The process that privileged the mechanistic over the organic was also needed to control, dominate, and violate nature as female while excluding woman from socially and economically dominant ideology and practices.” 33

The use of the machine over nature as a tool of suppression and exploitation is proven

30 Robert P. C. Joseph, 21 Things You May Not Know about the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality (Port Coquitlam, BC: Indigenous Relations Press, 2018). 68

31 Ibid., 68

32 Agrest, “The Return of the Repressed: Nature.” 55

33 Ibid., 55

34 Joseph. 25

35 “Reserves,” accessed August 21, 2023, https:// indigenousfoundations. arts.ubc.ca/reserves/.

in Canada’s use of the grid to fulfill the motives of the Indian Act. In a letter dated November 18, 1870, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald writes,

“… We should take immediate steps to extinguish the Indian titles somewhere in the Fertile Belt in the valley of Saskatchewan, and open it for settlement. There will otherwise be an influx of squatters who will seize upon the most eligible positions and greatly disturb the symmetry of future surveys.”34

In this shocking quote, it’s important to make note of a few terms. First, the motive is clear in the phrase “extinguish the Indian titles” that the goal is to remove indigenous people and their culture from the land. The term “squatters” clarifies that indigenous people are not welcomed into the new world of Canada. “Fertile Belt” shows the ideological view that the land is rich with opportunity, waiting to be cultivated with crops, which is achieved through the “symmetry of future surveys”, also known as the Dominion Land Survey or the grid. The geometry of the grid is an inflexible system because the strength of the grid represented the power of the government and the colonial goals it stood for. So in John A. Macdonald’s government, the success of the grid equated to dominating the indigenous population.

Part of the Indian Act included the creation of indigenous reserves. In the negotiation process with indigenous nations, reserves were created under the guise that these are pieces of land set aside for an [Indian] band’s use. Unfortunately in reality, reserves were created to control and contain indigenous people and to give advantage to settlers. The locations of reserves were not so systematic and varied based on the treaties, bands, or what suited the government causing the reserve to be outside of traditional territory.35 The size of reserves also varies, but was determined formulaically using the Dominion Land system. The calculations in determining sizes are different from treaty

Note: Reserves are included in the survey, suggesting that the government is not responsible for the land and does not have access to what is going on in reserve land.

from

to treaty; in Saskatchewan, Treaties 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 allocated 640 acres (1 section) per family of five and Treaty 2 allocated 160 acres (quarter section) per family of five.36 By moving indigenous people onto reserves, settlers were given full access to resources such as fish and game, water, timber, and mineral resources, while the boundaries and bureaucracy of the reserves systematically held resources away from indigenous people.37

Although the land was meant to be set aside for indigenous nations, there are many regulations within the Indian Act that have taken land away from the reserves. Some examples include the allowance of any public work including railways and roads to be created on reserves, and since 1911 this did not require the approval of the band.38

Or from 1896-1911, 21% of reserve land in the Prairie Provinces was surrendered for settlement because it was uncultivated.39 Reserve land is still precarious and is still under the control of the government even though it is declared to indigenous people. Private interests are allowed to work the land if it suits the need of the government through political loopholes. It is still not sovereign land.

The use of the grid is representative of the violent relationship that Eurocentric cultures have towards the landscape. One that is human-centric – man-centric to be exact – a relationship that is made to benefit man without regard for other beings, whether that is nature or people. If we continue with the analogy that nature is female, then the nature that we currently have in the prairies is like a female milking cow, anatomically manipulated and continually impregnated as a machine for production.

36

38

39

Where the Abstract Meets the Real

The grid is abstract, it is artificial. According to abstract expressionist art critic Clement Greenberg, the avant-garde and the abstract are reaching towards a higher mode of art, something that is pure and only exists within its own parameters, outside of current societal influences. Similar to how nature is abstract in the way that it is accepted as is; the avant-garde is reaching towards something God-like, something that can be accepted as is.40 The abstract qualities of the grid have been the subject of investigation for abstract artists such as Piet Mondrian or Agnes Martin.

The grid is also a design tool used to create order, whether it’s for the Prairie’s agricultural grid, a structural grid, a spreadsheet table, or a city plan. Diana Agrest describes the role of the gridded city in modernism,

“Grids were drawn over the natural terrain as if on a blank piece of paper: cities without history. The grid as a spatially open-ended, non-hierarchical system of circulation networks anticipating what communications would produce later in a non-physical, spatial way … the gridding of America should be seen as the creation of the real modern city, an abstract Cartesian grid with no past traced on virgin land.”41

Le Corbusier developed urban theories around the grid, which can be seen in his Ville Contemporaine, Plan Voisin, and Ville Radieuse. The idea of the “tower in the park” was created on a grid system to bring more greenery and landscape into the modern city. Nature in the city is reduced to becoming a “green plane” in the grid, which has two uses: first as a background for buildings and second as a way to organize the movement of cars as the lines of the grid become streets. 42 Like Le Corbusier’s city plans, the farmland grid in Saskatchewan reduces the landscape to a single plane of colour, divided by grid lines of roads. But unlike a city, the prairies are operating

40 Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” The Partisan Review, 1939, 34–39. 6

41 Agrest, “The Return of the Repressed: Nature.” 57-58

42 Ibid., 58

at a much larger and rural scale, creating planes of canola yellow, grain green, and snow white in the winter. This landscape of grid roads and fields of colour has come to resonate with the people of Saskatchewan.

In Saskatchewan, the abstract system of the grid is placed over ecological realities. The two diverging systems meet to become the current Prairie landscape.

Lens 3: Abandonment & Diaspora

Settlement mostly brought people from Eastern Canada and Britain, along with others coming from Ireland, Scotland, Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Ukraine.43 Saskatchewan is still predominantly a European-derived population, but has recently seen more people coming from all around the world. According to the most current census in 2021, there is a visible minority population of about 14.4%.44 The common view of Saskatchewan is of blue skies, wheat fields, and happy farmers of European descent. This understanding comes from media representation and a yearning nostalgic view for settlement times. But there are two phenomena occurring in the province that challenge this stereotype.

Statistics around Saskatchewan’s population show that people do not stay in the province. Based on Saskatchewan’s annual Population Report released in January 2023, the province’s average population growth rate has been 1.08% over the last 10 years.45 Within Canada, there are more people moving out of Saskatchewan to other provinces than the other way around; meaning that interprovincial movement is at a negative growth rate of -0.5%.46 Natural birth rates are not making up for this loss, so the population growth has relied on immigration. The province supplemented the deficit of interprovincial migration by bringing in 31,539 people internationally, which makes up 2.6% of Saskatchewan’s total population of 1,214,618 (2022).47 This movement of people shows that people tend to leave for other places so the province is relying on a continuous stream of newcomers to sustain its population. The province is unable to provide for the desires of Saskatchewanians; as observed by Mark Abley in his essay “Saskatchewan’s Diaspora”,

“It wasn’t just a matter of [their] aspiring to leave; in such an environment, to aspire is to leave”.48

This is because the source of the provincial economy of agriculture does not match the

Figure 31: Floating images of abandoned things in Saskatchewan

Figure 32: Photo of abandoned grain elevator > top to bottom

43 J. M. Porter and Cheryl Avery, eds., Perspectives of Saskatchewan (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2009). 61

44 Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, “Saskatchewan Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity: 2021 Census of Canada” (Statistics Canada, October 26, 2022).

45 Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, “Saskatchewan Annual Population Report,” March 22, 2023.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Porter and Avery. 353

1 : Four Lenses

Chapter

Chapter

interests of its people. In a way, agriculture has become the double-edged sword of the province. In the development of Saskatchewan, agriculture was used as a tool to populate the province with people from Europe and Ontario (Upper Canada at the time); now, it is the reason why people are leaving. As other industries such as manufacturing became a priority, agriculture became less of an interest.

As people leave, they leave behind the objects of their life, or artifacts of abandonment. This can come in the form of tools, tins, furniture, scrap metal, farm equipment, cars, buidlings, and so much more.

These items usually have two fates: either they are horarded into a shed, in the hope that someone will find them interesting, or they are left untouched slowly disintegrating into the landscape. The artifacts of abandonment hold the histories of those who lived in Saskatchewan in the past.

Lens 4: Land of Living Skies Machines

The second phenomenon is the innovation in farm equipment. Farming technology has evolved a lot over the years - from hand plows in early settlement days to the massive combines we see now, this has changed the way people farm.

Take my friend’s family farm for example. in the summer of 2023, Keegan’s family just celebrated the 100 year anniversary of the Jellicoe family farm. In 1923, Keegan’s great grandfather moved from Britain to start a new life on a farm about an hour away from Melfort, SK by taking advantage of the $10 quarter section parcel (160 acres) offered by the Dominion Land Act. At that time, it took two to three people to work the quarter section and only 75% of it was productive because of the practice of a summer fallow. Now, Keegan’s dad (Colin) owns two sections (1280 acres), which is eight times larger than the original farm. Now, the farm only needs one to two people to work and since the introduction of fertilizer, there is no need for a summer fallow. Keegan’s farm is considered a modest growth; one of his neighbours is a company that owns 20,000 acres with about 12 people working them. Farms are becoming larger while needing less man-power, meaning there is more reliance on farm equipment to operate on the land.

According to John Deere (who is the world’s leading farm equipment manufactuer and symbol of agriculture); the company is planning on building a world of fully autonomous farming by 2030.49 This includes a variety of self-driving equipment and spraying drones that can be controlled via a “Command Cab”, which uses AI to simulate the farm digitally onto a computer in a satellite location; that means you can farm in Saskatchewan, but live in Cabo.50 John Deere has already started the automation process by revealing their first fully automatic tractor in 2022.51

49 Bob Woods, “How John Deere Plans to Build a World of Fully Autonomous Farming by 2030,” CNBC, October 2, 2022, https://www.cnbc. com/2022/10/02/howdeere-plans-to-build-aworld-of-fully-autonomousfarming-by-2030.html.

50 “The Future of Farming Technology | John Deere,” accessed December 3, 2023, https://www.deere. co.uk/en/agriculture/futureof-farming/.

51 “John Deere Reveals Fully Autonomous Tractor at CES 2022,” accessed December 3, 2023, https:// www.deere.com/en/news/ all-news/autonomoustractor-reveal/.

With the introduction of automated systems, the movement of people out of rural areas will only be accelerated. The land will no longer be inhabited by people, but a series of agricultural machines.

CHAPTER 2

Interpretations of the Prairies

Figure 43: Gusts of wind make the windchimes sing. Gordon Reeve, The Coming Spring, 2018

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

A Critique of Architecture in Saskatchewan

Architecture has never been the source of culture in Saskatchewan, which is better represented in other fields like literature, music, and art. A look at the Saskatchewan Architects Association (SAA) report of 2022 shows us why. In a province with a population of 1,188,338 (2022)52, there are 408 registered architects. 314 of these are non-resident, meaning they do not live in the province; this leaves 94 resident architects that live and practice in Saskatchewan.53 Because of the lack of an architecture school, any prospective students need to leave the province for education and they tend to stay away after graduation because of the lack of architectural opportunities back home in Saskatchewan. There are no contemporary architecture practices in the province that particularly stand out; this may be part of the reason why the new cultural buildings such as the Remai Modern Gallery and the upcoming Saskatoon public library are designed by architects from other provinces.

52 “Saskatchewan’s Dashboard - Population,” Government of Saskatchewan, accessed August 23, 2023, https:// dashboard.saskatchewan. ca/people-community/ people/population.

53 “Saskatchewan Association of Architects: 2022 Annual Report.”

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

Pop

Culture

Saskatchewan culture is and has always been fruitful and is represented in all sorts of mediums and schools of thought. The common ground for them all is the landscape, a powerful image that enters the ethos and the minds of the people that know it – it’s become the source of inspiration for pop culture and high culture. Those who grew up in the province but have left for bigger, better places, take with them the impressions left by the prairie landscape. It’s influenced the likes of singer songwriter Joni Mitchell, who grew up in Saskatoon, SK and sings about the place she is from in “River”, “Urge for Going”, and “Paprika Plains”,

Back in my hometown

They would have cleared the floor

Just to watch the rain come down

They’re such sky oriented people

…

I dream paprika plains

Vast and bleak and God forsaken

Paprika plains

And a turquoise river snaking

(Mitchell, “Paprika Plains”) 54

Her lyrics frequently visits themes of the sky; the landscape has seeped into songs that are not about the prairies like “Goodbye Blue Sky”, “Amelia”, “Both Sides Now”, and “Hejira” to name a few.

Abstract expressionist Agnes Martin spent most of her life in the United States, was born in rural Macklin, Saskatchewan. Her paintings, more frequently than not were variations of a pencil drawn grid on a six by six foot canvas, resembling an aerial view of the prairie

54 “Joni Mitchell - Paprika Plains - Lyrics,” accessed August 17, 2023, https:// jonimitchell.com/music/ song.cfm?id=171.

top to bottom

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

“You know, I’ve uh, never driven across Saskatchewan before”

“It sure is flat”

“There’s lots to see. There’s nothin’ to block your view” *waves hand*

“Well you still haven’t really, about half way to go yet”

“Hey Hank! This guy says Saskatchewan is flat. He says there’s nothin’ to see”

“It is kinda flat. Thanks for pointing that out”

<

55 Victoria Watson, “Pictorial Grids: Reading the Buildings of Mies van Der Rohe through the Paintings of Agnes Martin,” The Journal of Architecture 14, no. 3 (June 2009): 421–38, https://doi. org/10.1080/1360236090 3027996.

56 Wallace Stegner, Wolf Willow: A History, a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier, 4. print, A Viking Compass Book 197 (New York: Viking Press, 1971). 23

57 Porter and Avery. 351

58 “Ruby Reborn,” Corner Gas (CTV, January 22, 2004).

Chapter 2: Interpretations of

agricultural grid. Although the work is described as not being literal representations of anything,55 it’s hard to ignore the possible influence that the agricultural grid must have had on Martin’s idea of the world.

Then there is American writer Wallace Stegner, a Pulitzer Prize winner and English professor at Stanford University who spent a part of his childhood by the Cypress Hills of Southern Saskatchewan. He writes in his classic part fiction, part non-fiction memoir Wolf Willow,

“I may not know who I am, but I know where I am from.”56

Although Stegner only spent six years in the small town of Eastend, according to him those years greatly shaped how he understood himself.57 Joni Mitchell, Agnes Martin, and Wallace Stegner are examples of people that represent Saskatchewan’s diaspora.

And finally there is Corner Gas, a popular CTV show that aired from 2004-2009 which depicts small town life in Saskatchewan. Even though Dog River is a fictional town, the well-loved show presents what day-to-day life could look like in a rural place. The show revolves around the town’s main institution, the gas station, the only one for 60km in any direction. In the pilot episode, the opening scene immediately makes a sarcastic joke about the prairie’s stereotypical flatness.58 Watching the show gives the viewer a glimpse into of some of the cultural practices (and dry humour) of rural Saskatchewan.

The mid-twentieth century was an interesting time for art in Saskatchewan. From 1955 to 2012, the University of Saskatchewan ran a summer workshop just north of Prince Albert at Emma Lake. World class artists and critics were invited to run the workshops including Barnett Newman in 1959, Jules Olinski in 1964, Donald Judd in 1968, and Anthony Caro in 1977 just to name a few. Most influentially, New York art critic Clement Greenberg was a workshop leader in 1962, and he grew to admire and have great interest in the abstract art coming from Saskatchewan. In a review of art on the prairies published in Canadian Art in 1963 he said,

“…almost everybody, to my surprise, turned out to be a ‘pro’. And I mean a ‘pro’ in the fullest sense … I am aware that it may seem distorted by favouritism towards Saskatchewan. I honestly don’t feel that it is distorted in this respect.”59

A few of the artists who were part of this discourse included the Regina Five, Otto Rogers, William Perehudoff, and Dorothy Knowles. One of the outstanding sculptors was structurist Eli Bornstein, whose work investigated play of light with colour and form, 60 the architectural sculptures remind me of movement in the prairie landscape. At the same time, there was another group of artists at the university that worked in a more representational manner and frequently worked with clay. This group, known as the funk artists, included sculptors Joe Fafard, Victor Cicansky, Marilyn Levine, and painter David Thauberger. There came to be a bit of a rivalry between the abstractionists and the funk artists, yet the common interest found in the work of both camps is the subject of the Saskatchewan landscape.

Now, art in Saskatchewan is headed in a different direction. Regina-based Mackenzie Art Gallery curator Nicolle Nugent describes how current art focuses on research and Art

59 Clement Greenberg, “Clement Greenberg’s View of Art on the Prairies,” Canadian Art 20, no. 2 (March 1963): 90–107. 94, 107

60 Ibid., 90-107

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

61 “Meryl McMaster: Bloodline,” Remai Modern, April 12, 2023, https:// remaimodern.org/whatson/exhibitions-all/merylmcmaster-bloodline/.

62 “Laure Prouvost: Oma-Je,” Remai Modern, March 28, 2023, https:// remaimodern.org/whatson/exhibitions-all/laureprouvost-oma-je/.

inquiry. Art is working on reflecting today’s society back at us, and that means giving space to voices that have not been listened to. Today, themes frequently centre on issues of the environment, feminism, ableism, and colonialism. During my visit to the Remai Art Gallery in Saskatoon, two of the exhibitions stood out to me. The first is Meryl McMaster’s bloodline, a photo exhibition that reflects McMaster’s Plains Cree/ Métis, Dutch, and British ancestry.61 Each photograph captures McMaster dressed in a handmade costume made of a variety of materials and objects that reference traditional clothes and stories. She then poses and interacts with a sublime landscape, frequently in Saskatchewan, telling the narrative of both indigenous and settler histories. The second exhibition is Laure Prouvost’s Oma-je, which journeys through themes of knowledge transfer, water, and motherhood.62 The most impressive part of the installation was the hundreds of mobiles hung on a moving curtain track made of stuff she found on the highways of Belgium and France. Each mobile had the interplay of man-made and natural materials. For me, both exhibits were interested in recounting a narrative by using found objects from the landscape to create work that interacts with the environment.

Other local contemporary artists also work within the practice of found objects to explore narratives. Lyle XOX who is from Wymark, SK now based in Vancouver, BC creates elaborate head sculptures with recycled garbage. He describes a story from his childhood,

“I grew up in a home where, before I was even going to kindergarten, I was doing craft days with my mom. We would make stuff out of literally nothing. I have this memory of my mom making this peacock one day out of a styrofoam egg carton. Remember those pastel styrofoam egg cartons in yellows and greens and pinks? Watching my mom, I was completely fascinated by the idea that I could take something without value and turn it into an object of beauty.”63

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

63 Katie White, “‘I Take Something Without Value and Turn It Into An Object of Beauty’: How Lyle XOX Transforms Trash Into Extravagant Wearable Art,” Artnet News, October 1, 2020, https://news.artnet. com/partner-content/lylexox-interview.

64 Stonhouse, David. “Powerboxes (2021),” David Stonhouse, accessed August 23, 2023, http://www. davidstonhouse.com/ powerboxes-2021.

65 “Ric Pollock Turns Scrap into Sculpture in SmallTown Saskatchewan,” thestarphoenix, accessed August 23, 2023, https:// thestarphoenix.com/ entertainment/local-arts/ ric-pollock-turns-scrapinto-sculpture-in-smalltown-saskatchewan.

And then there’s David Stonhouse from Saskatoon, who in his series Powerboxes creates sculptures based on peculiar moments found on the buildings of rural Saskatchewan.64

Lastly, there is Ric Pollock in Arlee, SK, creates sculptures from scrapped material from customers, patrons, and farmers around his area.65 This artistic discourse shows a cultural interest in things that are lying around, waiting to be used.

From Joni Mitchell to Eli Bornstein to Ric Pollock, there lies a discourse of Saskatchewan prairie culture that architecture can be part of.

>

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

Outside of Saskatchewan, the Prairie School in the Midwestern United States had great influence over architecture in the 20th century. Led by Louis Sullivan, Prairie School architecture can be seen in the works of George Grant Elmslie, William Purcell, Parker Berry, William E. Drummond, William L. Steele and big shot architect Frank Lloyd Wright in the period from 1900 to WWI.66 The style can be seen in a few commercial projects such as the Larkin Building, completed in 1904 in Buffalo, NY (which is now demolished), but the style was typically used for private homes. The Prairie School developed a style that is inspired by the open plains of the Midwest and is distinguished by the formal emphasis on the horizontal line.67 The buildings typically have open floor plans, modest ceiling heights, large roof overhangs, and continuous strip windows with short vertical mullions. Masonry was a common material for the houses, its visual heaviness made the buildings look hunkered down on the site.

The projects of the Prairie School started in suburban Chicago and later on the style travelled to suburbs in other cities, rural Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. Even though the Prairie School architecture is derived from the prairie landscape, it is simply a style that can be applied to any building. Comparing two of the most notable projects of the Prairie School (both by Frank Lloyd Wright), the Robie House in Chicago (1910) and the Martin House in Buffalo (1905), the two are remarkably similar even though Chicago and Buffalo are different cities in different states with different histories and landscapes. Even more incongruously, the only Prairie School building in Canada was Wright’s Banff Pavilion, situated not in the Prairies but in the Rocky Mountains.68

66 H. Allen Brooks, The Prairie School (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006). 5

67 Ibid., 5

68 “Frank Lloyd Wright Pavilion | Banff, ABOfficial Website,” accessed September 3, 2023, https:// banff.ca/487/Frank-LloydWright-Pavilion.

Chapter 2: Interpretations of the Prairies

Canadian Architecture & Clifford Wiens