Remembering VIC JURIS

BY CYDNEY HALPIN

Ihope this issue of Jersey Jazz finds you ever vigilant about your health and the health of others as we continue to find creative ways to stay connected while masked and socially distant.

It’s with a heavy heart that I must tell you about the death of Marcia Steinberg—longtime NJJS board member and ardent jazz enthusiast. Nobody could work a room, make introductions, and spread the joy of jazz like Marcia. Her desire to support musicians, champion up and coming talent and to always stay current with the music made her an incredible ambassador for the art form. The board and I wish to extend our deepest condolences to Marcia’s family and friends. She’ll be greatly missed. True to form, I know she’s enjoying heaven’s incredible big band with zeal. Please see page 36 for more information about her life and legacy.

This time last year, we introduced the redesigned Jersey Jazz with Editor Sanford Josephson and Art Director Steve Kirchuk. Steve has chosen not to continue in this capacity but remains our webmaster. The board and I would like to thank him for his dedication and service to NJJS.

This issue of Jersey Jazz marks the beginning of our new partnership with Art Director Mike Bessire. Please join me in welcoming him to the NJJS family, as his expertise will be invaluable as we traverse the challenges that lie ahead for this organization.

Please join me in welcoming Jane Fuller to the NJJS Board of Directors. Jane has an extensive background in strategic partnerships and brand management, having worked with consumer giants Coca Cola, Pepsi Co., and Colgate-Palmolive. Jane is a Jersey native and grew up in Princeton where, after many years living and working in Manhattan, now resides again with her husband—jazz pianist—Larry Fuller. Given her knowledge of the jazz industry and her expertise as a marketing leader, we’re thrilled to have her join the board as we work to design the future of NJJS.

One of the benefits of membership to NJJS is the opportunity to attend our scheduled Sunday Socials free of charge. The Covid-19 pandemic has interrupted this opportunity and has forced us to adapt and shift our programming to an online streaming format via Facebook and Youtube.

Given our new reality, please join us Sunday, September 20th at 4p.m. for our Virtual Social “Dave Stryker and Friends” as they present a tribute concert in honor of the late Vic Juris. Please check our website www. njjs.org closer to the event for more information and any necessary log in codes. This is sure to be a wonderful concert that you won’t want to miss. See page 05 for more information.

Sneak Peak … I’m thrilled to announce that the Pizzarelli family has generously donated one of Bucky’s amazing paintings to NJJS, with all proceeds

02 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ ON THE COVER Vic Juris. Photo by Mitchell Seidel

ALL THAT’S JAZZ

COLUMNS 02 All That’s Jazz 04 Editor’s Choice 32 Dan’s Den 37 Not Without You! 38 From the Crow’s Nest ARTICLES/REVIEWS 05 Jazz Social: Remembering Vic Juris 06 Outside at Shanghai Jazz 07 Jazz on the Back Deck 08 Eric Reed Live at the Vanguard 10 Talking Jazz: Lucy Yeghiazaryn 14 Rising Star: Sarah Hanahan 16 WPU Summer Jazz Room Series 18 Big Band in the Sky 20 Central Jersey Jazz Festival 22 Musical Journey: Jerry Weldon 24 Other Views 28 At Home With Bill Mays 29 Book Review:Jazz Images 30 Swingin’ the Blues with Swingadelic

IN THIS ISSUE

from its sale to benefit the Society. As of press time, we’re still in the process of figuring out how best to offer and manage the auction of this extraordinary gift but more detailed information will follow on our website www. njjs.org and in the November/December issue of Jersey Jazz.

(Please note, this painting is actually in very vibrant colors and will be pictured on our website accordingly.)

If we’ve learned anything throughout this pandemic it’s that change is here to stay! The creativity that has emerged via virtual online platforms from musicians, venues, cultural institutions, etc., has been amazing.Individuals and organizations have embraced technology to stay connected, productive, and engaged with their audiences, presenting a vast array of incredible new and archived content.

To this end, I hope you’ve discovered Jay Daniels’ Simply Timeless Radio show we’ve added to our website www.njjs.org. This program is FREE to listeners and content is changed every Friday. I encourage you take advantage of this delightful program.

Every aspect of the jazz industry has been turned upside down with this pandemic and the production of Jersey

Jazz is no exception. We’ve lost three fourths of our advertising revenue with musicians out of work, venues shuttered, and events cancelled for who knows how long. After much board debate, and given the industry wide uncertainty of circumstances, it’s become obvious that we can no longer afford to produce a bi-monthly print edition of Jersey Jazz. Sadly, the November/December 2020 magazine will be our last printed and mailed issue. The magazine will continue however as an online publication, accessible through our website.

We remain committed to the same editorial excellence that has been the the driving force of this publication, but it will be online starting in January 2021. We remain steadfast to our mission—the promotion and preservation of jazz—but through more modern and necessary means.

Your membership is of the utmost importance to us and we’re working diligently to redesign our website to provide you with the easiest and most rewarding experience as you continue to enjoy Jersey Jazz on your computer, tablet or phone.

I know this information likely comes as a shock and a disappointment and as president of this organization, it’s horrible news to deliver! To continue to operate in a fiscally irresponsible manner isn’t prudent and poses a threat to our mission, programs and future.

This organization has had the support of its members for almost 50 years. I hope you’ll see fit to rise to the times and embrace our new reality as we work together within these trying times. If you have any questions or suggestions, please contact me via email at pres@njjs.org.

President Cydney Halpin pres@njjs.org

Executive VP Jay Dougherty vicepresident@njjs.org

Treasurer Dave Dilzell treasurer@njjs.org

VP, Membership Pete Grice membership@njjs.org

VP, Publicity Sanford Josephson sanford.josephson@gmail.com

VP, Music Programming Mitchell Seidel music@njjs.org

Recording Secretary Irene Miller

Co-Founder Jack Stine

Immediate Past President Mike Katz

DIRECTORS

Ted Clark, Cynthia Feketie, Stephen Fuller, Carrie Jackson, Mike Katz , Peter Lin, Caryl Anne McBride, Robert McGee, James Pansulla, Stew Schiffer, Elliott Tyson, Jackie Wetcher

ADVISORS

Don Braden, Al Kuehn, Bob Porter www.njjs.org

03 SEP—OCT • 2020 NJJS.ORG Magazine of the New Jersey Jazz Society VOLUME 48 • ISSUE 4 • USPS® PE6668 Jersey Jazz (ISSN 07405928) is published bi-monthly for members of The New Jersey Jazz Society P.O. BOX 223, GARWOOD, NJ 07027 908-380-2847 • INFO@NJJS.ORG Membership fee is $45/year. Periodical postage paid at West Caldwell, NJ Postmaster please send address changes to P.O. BOX 223, GARWOOD, NJ 07027 All material in Jersey Jazz, except where another copyright holder is explicitly acknowledged, is copyright ©New Jersey Jazz Society 2020. All rights reserved. Use of this material is strictly prohibited without the written consent of the NJJS. Editor Sanford Josephson editor@njjs.org Art Director Michael Bessire art@njjs.org International Editor Fradley Garner fradleygarner@gmail.com Contributing Photo Editor Mitchell Seidel photo@njjs.org Contributing Editors Dan Morgenstern, Bill Crow, Schaen Fox, Sandy Ingham, Joe Lang Contributing Photographers Jack Grassa, Tony Graves, Mitchell Seidel, Bob Verbeek NEW

JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY OFFICERS 2020

PRINTED BY: BERNARDSVILLE PRINT CENTER

THE EDITOR’S CHOICE

BY SANFORD JOSEPHSON

1935: Benny Goodman hired Black pianist Teddy Wilson to be part of his trio, which also included drummer Gene Krupa. Soon after that, the trio was expanded to a quartet with the addition of another African-American musician, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton.

1936-51: When bassist Milt Hinton played with Cab Calloway’s band, it was difficult for Black musicians to find decent hotel rooms, so Calloway would lease a Pullman car, drive from town to town, and park the Pullman on the side of the tracks. “We’d play the town and come on back and go to sleep,” Hinton said.

“ THERE IS NOTHING NEW IN THE WORLD EXCEPT THE HISTORY YOU DO NOT KNOW.”

—HARRY S. TRUMAN

1937-45: Earle Warren, a light-skinned African-American saxophonist with Count Basie’s Orchestra would sometimes procure food for other band members because he could pass for white. “A lot of cities didn’t offer decent food or nothing for colored people,” he said. “The restaurants we could go to were greasy restaurants; or if we went to a place where they had a wall where it said, ‘colored on one side and white on the other’, it was still greasy and funky.”

1947-51: The Louis Armstrong All-Stars, with Jack Teagarden on trombone, was a racially mixed band with relatively few racially-related problems because of Armstrong’s prestige. However, the Black and white musicians often had to stay at separate hotels. “We’d get to town, especially in the South,” said Black bassist Arvell Shaw, and they’d go to the white section, and we’d go to the Black section. That’s the way it was in those days, and that’s what we were accustomed to.”

1949: The mixed-race aspect of Miles Davis’ Birth of the Cool nonet was groundbreaking. In the words of jazz writer Stanley Crouch, “Close collaboration of the sort [Miles] Davis and John Lewis had with Gerry Mulligan, Gil Evans, and Johnny Carisi had not happened before.”

1950s: Dave Brubeck refused to cave in when some college deans, primarily in the South, requested that his African-American bassist Eugene Wright not perform at campus concerts. Brubeck also turned down a 1958 tour in South Africa rather than sign a contract specifying that his band would be all white.

2020: Saxophonist Scott Robinson created a musical piece of 8 minutes and 46 seconds duration, “the exact length of time it took for a man’s life to ebb away on that horrifying video we have all seen in the news.”

ABOUT NJJS

Founded in 1972, The New Jersey Jazz Society has diligently maintained its mission to promote and preserve America’s great art form – jazz. To accomplish our mission, we produce a bi-monthly magazine, Jersey Jazz; sponsor live jazz events; and provide scholarships to New Jersey college students studying jazz. Through our outreach program Generations of Jazz, we provide interactive programs focused on the history of jazz

The Society is run by a board of directors who meet monthly to conduct Society business. NJJS membership is comprised of jazz devotees from all parts of the state, the country and the world. Visit www.njjs.org or email info@njjs.org for more information on our programs and services.

MEMBER BENEFITS

10 FREE Concerts Annually at our “Sunday Socials”

Bi-Monthly Award Winning Jersey Jazz Magazine - Featuring Articles, Interviews, Reviews, Events and More.

Discounts at NJJS Sponsored Concerts & Events.

Discounts at Participating Venues & Restaurants

Support for Our Scholarship and Generations of Jazz Programs

MUSICIAN MEMBERS

FREE Listing on NJJS.org “Musicians

List” with Individual Website Link

FREE Gig Advertising in our Bi-monthly eBlast

THE RECORD BIN

A collection of CDs & LPs available at reduced prices at most NJJS concerts and events and through mail order www.njjs.org/Store

JOIN NJJS

Family/Individual $45 (Family includes to 2 Adults and 2 children under 18 years of age)

Family/Individual 3-Year $115

Musician Member $45 / 3-Year $90 (one time only, renewal at standard basic membership level.)

Youth $15 - For people under 21 years of age. Date of Birth Required.

Give-A-Gift $25 - Members in good standing may purchase unlimited gift memberships. Applies to New Memberships only.

Fan $75 - $99

Jazzer $100 - $249

Sideman $250 - $499

Bandleader $500+

Corporate Membership $1000

Members at Jazzer level and above and Corporate Membership receive special benefits. Please contact Membership@njjs.org for details.

The New Jersey Jazz Society is qualified as a tax exempt cultural organization under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, Federal ID 23-7229339. Your contribution is taxdeductible to the full extent allowed by law. For more Information or to join, visit www.njjs.org

04 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

TOP:

PHOTO BY TONY GRAVES; BOTTOM: PHOTO BY MITCHELL SEIDEL.

VIRTUAL JAZZ SOCIAL

Dave Stryker Remembers Vic Juris

BY MITCHELL SEIDEL

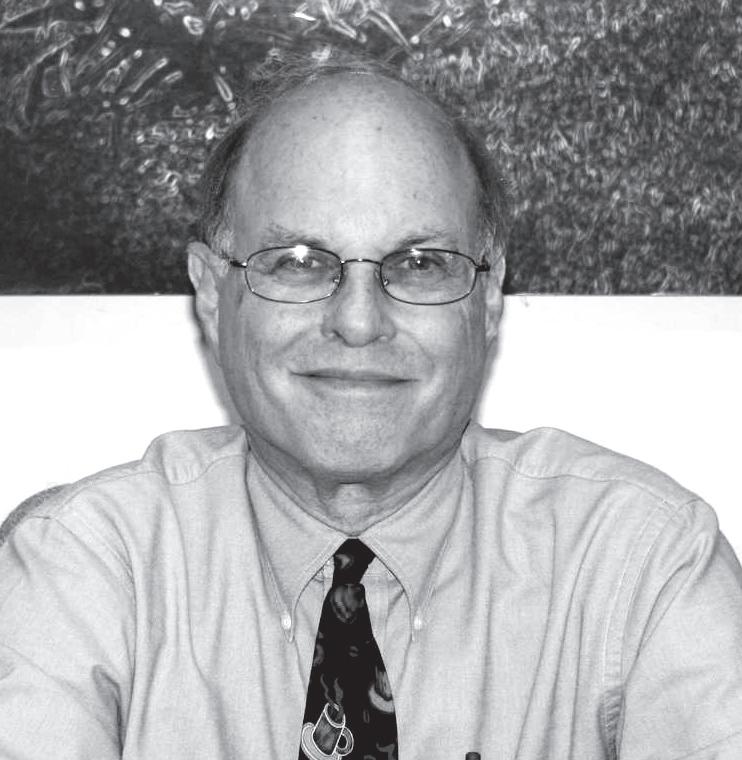

The jazz world is anchored by people like guitarist Vic Juris, musicians possessing such talent they can be counted on to seamlessly lead or support sessions of all sorts. Through his career Juris supported funky organists, boppish horn players and even the ultra-modern saxophonist David Liebman, who in a post-mortem tribute pronounced him “the hardest worker I have known.”

We can proudly call the Jersey City native “local talent” who lived most of his life in North Jersey. Indeed, when he wasn’t on the road, Juris could be found playing somewhere in the region. Corona notwithstanding, it’s odd to see jazz listings and not find that Juris is performing somewhere locally. “I always have gigs,” he said in 2017. “I always make sure that I’m playing, and that there’s a challenge in it for

“ STRYKER AND JURIS LIVED IN THE SAME WEST ORANGE NEIGHBORHOOD.

me.” Juris died December 31, 2019, at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, NJ, at the age of 66 after a six-month battle with liver cancer.

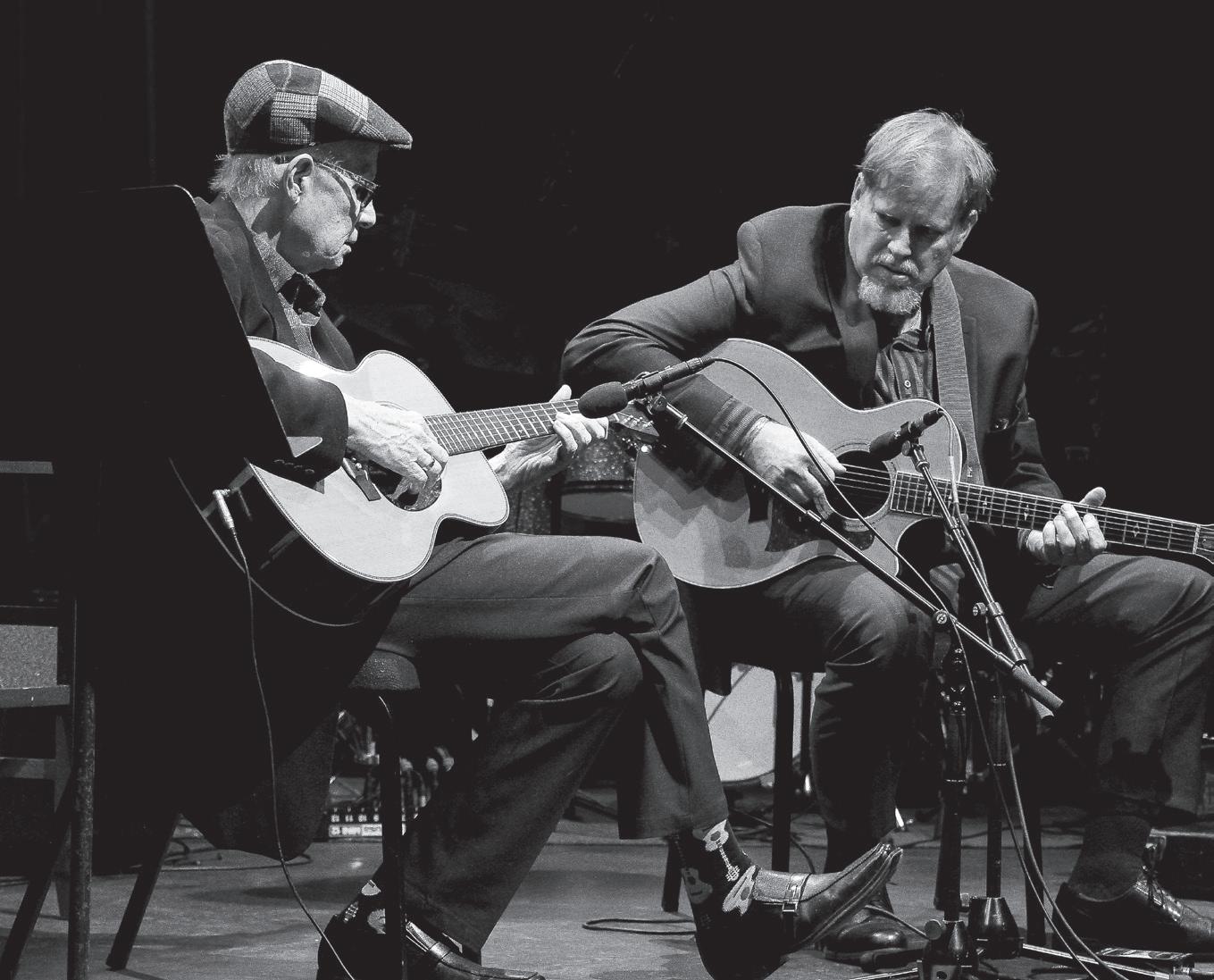

Anyone who follows guitarists can tell you they’re a close-knit bunch. They go to each others’ gigs, check out their compatriots’ compositions and albums, and, in the case of guitarists Dave Stryker and Juris, lived in the same West Orange neighborhood. There was always a sense of mutual admiration when they got together and jammed or simply crossed paths and talked shop.

An example of that will be on display on September 20 at NJJS’ Virtual Social. when Stryker will give a nod to his late friend while also performing some of his own material. Stryker will perform live from 4-5 p.m. on the NJJS Facebook page.

Ever since Stryker arrived in New Jersey from his native Omaha some 40 years ago, he has been ubiquitous on area stages and in clubs. He also has recorded a selection of albums that have garnered him recognition throughout the jazz community.

Stryker has performed with such notables as organist Jack McDuff, and saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, among others. He has numerous album credits as a writer and arranger, some 50 as an album sideman, and nearly as many under his own name.

As we get closer to the Social concert date, please check the NJJS website (www.njjs.org) for updated log-in information. Funding for the NJJS Socials has been made possible in part by Morris Arts through the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a partner agency of the National Endowment for the Arts.

05 SEP—OCT • 2020 NJJS.ORG

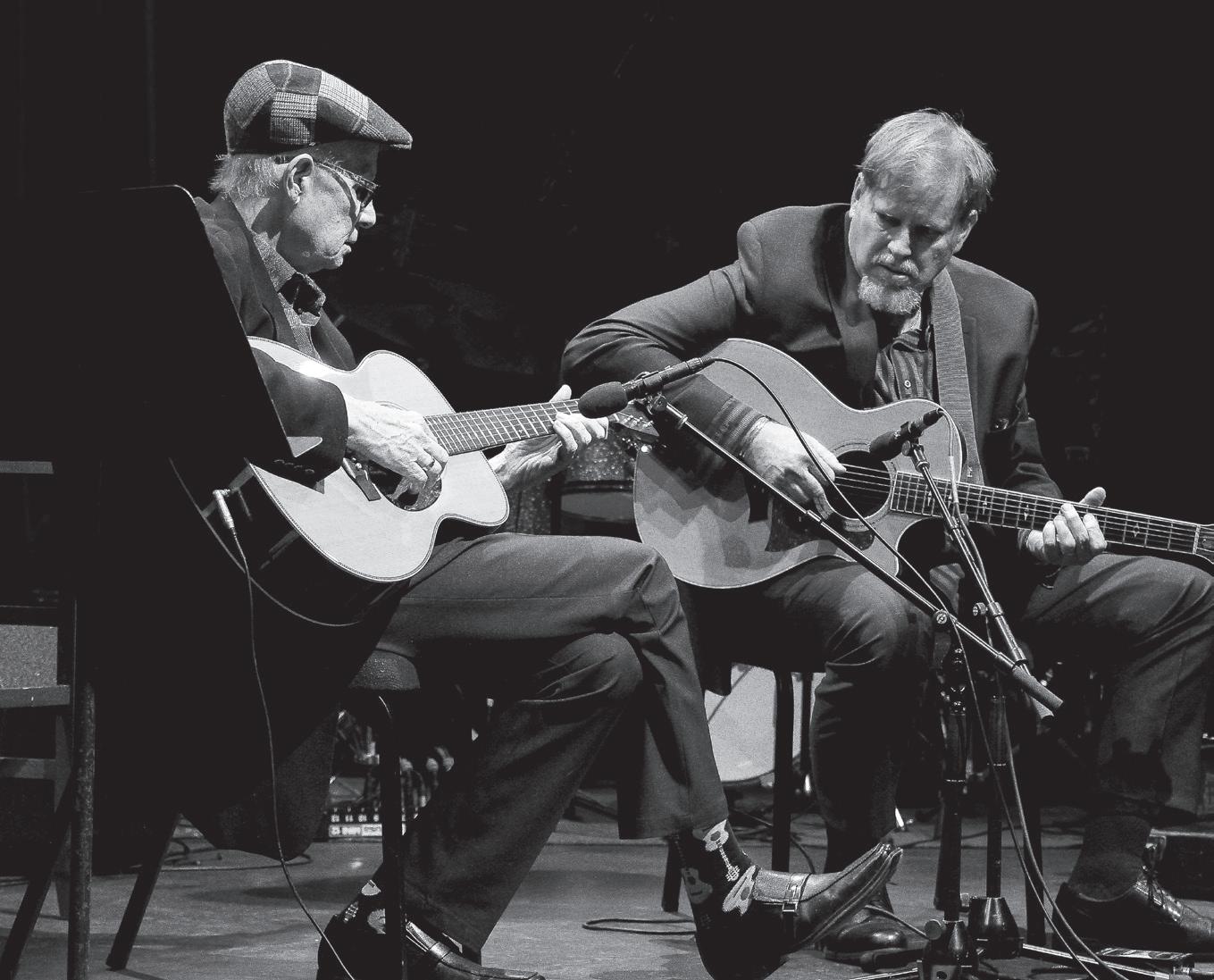

Vic Juris, left, and Dave Stryker last November at the Giants of Jazz concert in South Orange.

TOP: PHOTO BY TONY GRAVES; BOTTOM: PHOTO BY MITCHELL SEIDEL.

OUTSIDE AT SHANGHAI JAZZ

Leonieke Scheuble Channels

Her Inner Bobby Timmons

Eighteen-year-old pianist Leonieke Scheuble has an affinity for the hard bop music of the 1950s and early ‘60s. During her second set on the parking lot outside Shanghai Jazz on July 29, she dove into such hard bop classics as Bobby Timmons’ “Dat Dere” and “Moanin’” and Horace Silver’s “Senor Blues”. Her trio, which includes her father Nick Scheuble on drums and Tim Givens on bass, had been rained out twice before finally having a successful outdoors appearance at the Madison, NJ, jazz club.

Timmons is Leonieke’s favorite pianist. Last year, just before pianist Harold Mabern passed away, she got to play “Dat Dere” with him in a practice room at William Paterson University, where she will begin her Jazz Studies college career this fall. (Father Nick is

a WPU alum). “I grew up hearing [Lee Morgan’s] ‘Sidewinder’, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, and Clifford Brown,” she said. “Hard bop has a blues aspect, and I’ve always gravitated toward tunes that are bluesey.”

Her other favorite keyboardists are Wynton Kelly, Bud Powell, and Cedar Walton, but, at Shanghai, she also gave a nod to the blues style of Ray Bryant with

“ HARD BOP HAS A BLUES ASPECT ... AND I’VE ALWAYS GRAVITATED TOWARD TUNES THAT ARE BLUESEY.”

a performance of his “Cubano Chant”, played the Dizzy Gillespie classic, “Tin Tin Deo”, and sprinkled in some standards such as Arthur Schwartz’s “You and the Night and the Music” and Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood”. During the second set, the trio introduced a surprise guest, vocalist Antoinette Montague, who belted out Louis Jordan’s “Let the Good Times Roll”, followed by the trio’s performance of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Favela”.

The following day, July 30, Leonieke led her “Hard Bop/Soul” quintet in a free early afternoon concert outside the Kearny Public Library in Kearny, NJ. Featuring trumpeter Rick Savage and tenor saxophonist Adam Brenner, along with Nick Scheuble on drums and Givens on bass, they played “The Chess Players”, a song from Art Blakey’s 1960 Blue Note album, The Big Beat, that Harold Mabern taught students to play by ear when Savage was attending William Paterson. That concert also included Hank Mobley’s “Infra-Rae” from the 1956 Columbia release, The Jazz Messengers. Savage fit right into the hard bop mood of the concert, evoking his major influences,who are clearly Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, and Lee Morgan.

The environment at Shanghai was designed to keep everyone safe during the coronavirus. Tables were spaced a minimum of six feet apart or more. There was hand sanitizer on every table, and all wait staff and performers (when possible) were wearing masks. Every employee, according to owner Tom Donahoe, “is required to submit to a temperature check” upon arrival. “The first priority,” he added, “is the health and safety of the patron.” While the fall performance schedule wasn’t complete at presstime, the Warren Vache Quartet was slated to appear on September 16.

06 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

Bassist Tim Givens and pianist Leonieke Scheuble.

PHOTO BY JACK GRASSA

JAZZ ON THE BACK DECK

The Return of Live Music to the Morris Museum

BY BRETT WELLMAN MESSENGER

After months of live streams, zoom concerts, and digging through my collection of vinyl records for old gems, I found myself craving live music in a way I never had in my life previously. I had taken it, along with many things, for granted. As the weather improved, and the curve in New Jersey flattened, I started to ponder the ways we could start to bring music back to audiences in a safe and responsible way. That led to a welcomed outing from my apartment and to the grounds of the Morris Museum to look for a new venue and to consider new possibilities. As I walked out onto the back parking deck, I could already see the stage and hear the music. I returned that night with a tape measure, and some camping chairs. Once I felt confident that we could pull this off safely, I reached out to some of our favorite jazz musicians to get a sense of their interest. It did not take long to line up a schedule.

On July 16, we opened Jazz on the Back Deck with Amani, and what a special evening it was! The Morris Museum staff banded together, working all day in the beating hot sun to clean up, set up, measure, and chalk lines. Our patrons arrived and graciously followed the new protocols, and I witnessed a level of neighborly courtesy and understanding that was truly inspiring. All of that was before the music even started. If laughter is the best medicine, music is a close second. As I sat, along with our audience, to enjoy Amani; the Mariel Bildsten Quartet, on a rain-delayed Saturday night performance, July 25; and on July 30, clarinetist/saxophonist Dan Levinson and his ensemble of familiar masters, I returned to a sense of normalcy through music.

Our final concert of this abbreviated season took place on August 6, featuring Big Fun(k), a “groove/jazz/soul” quartet coled by saxophonist Don Braden and drummer Karl Latham, but stay tuned—we have big plans for September! This presentation was sponsored by our friends at the New Jersey Jazz Society.

I feel deep gratitude for the opportunity to safely gather and enjoy music together. I will never take the ability to hear live music for granted again. I do not have a crystal ball, and I cannot predict when I will stand on the stage of the Bickford Theatre, looking out at a sold-out, jam packed theatre to introduce a concert again, but I have faith that that day will come again, and in the meantime I look forward to providing audiences with as much as we can responsibly manage out on the Back Deck. I hope to see you out there soon!

Brett Wellman Messenger is Curatorial Director of Live Arts at the Morris Museum.

07 SEP—OCT • 2020 NJJS.ORG

Drummer Karl Latham and saxophonist Don Braden.

PHOTO BY JACK GRASSA

BY SANFORD JOSEPHSON

Music to pianist Eric Reed, “is not just about my livelihood, it’s my heartbeat.” So, when he had an opportunity to leave his home in Los Angeles and do two virtual performances at New York’s Village Vanguard in July, he grabbed “my heavy duty mask and got on a plane.”

On Friday night, July 10 and Saturday, July 11, Reed led a quartet featuring bassist Dezron Douglas, drummer McClenty Hunter, and tenor saxophonist Stacy Dillard in an empty club, playing to an audience that watched online.

The performances included a tribute to Bud Powell, “Dear Bud”, Cedar Walton’s “Martha’s Prize”, the Jules Styne/Sammy Cahn standard, “It’s

ONLINE AT THE VILLAGE VANGUARD

Pianist Eric Reed

Previewing a New Album and Paying Homage to Bud Powell, Cedar Walton, and Sammy Cahn

You or No One”, and “Western Rebellion”, an original composition that will be featured on a new Smoke Sessions album, Such a Time As This, to be released later this year. When he was first locked down at home in Los Angeles, as a result of the coronavirus, Reed was determined “to practice five or six hours every single day and go for a walk every day. For three weeks, I was good. I was at my piano, taking a two-mile walk, writing symphonies and concertos.”

By week four, he said, it was getting old. “The best thing that came out of it,” he said, “was the music I composed. I wrote a song, ‘Waltz’, for Wallace Roney, (who died from Covid March 31) and another, ‘Bebophobia’, maintaining the tradition of the jazz contrafact and referencing the extreme fear and aversion to bebop, as manifested by the unenlightened.” (A jazz contrafact is a musical composition consisting of a new melody over-

laid on a familiar harmonic structure, such as Charlie Parker’s “Koko”, based on Ray Noble’s “Cherokee”).

Another song on Such a Time As This , Reed said, is called “Paradox Peace”, which describes the atmosphere of Los Angeles during Covid. “On a Sunday night a week after the quarantine hit, I went for a drive around 10 o’clock. It was raining, and I drove around West Hollywood. It was so eerie, like a ghost town. Literally, there was no one on the streets. It was peacefulness but a paradox.” Reed had a similar experience in New York three months later. “We ended the show at the Village Vanguard around 10:30 on Friday night. There was nobody on the street in the Village at midnight. That really messed me up.”

Roney, according to Reed, “was one of the most misunderstood musicians that I knew. I think Wallace suffered

08 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

from low self-esteem. There was a certain childlikeness and wonder about him when he would talk about other great musicians.” Reed compared Roney to the main character in Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee, someone who would have been more comfortable in a different time period. “He seemed to be a soul or spirit that could have been some kin of Buddy Bolden, existing before the music industry, when music was closer to the culture.” Powell, Reed added, “was a musician largely misunderstood, misread, mistreated, when people treated substance abusers like they were criminals, not like people who had a disease. Most of his career, as brilliant as he was, he sort of spent in another world. His music spoke for him. And, he may have also had some issue with self-esteem. Bud Powell didn’t take the easy route. Like Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, Art Tatum, he didn’t do it the easy way. He continued to explore, challenge, invent. He was not repaid well for it. He was not appreciated en masse. ‘Dear Bud’ is sort of a letter that I wrote him.”

“Martha’s Prize” was included on Walton’s last studio album, the 2011 HighNote release, The Bouncer. It was also on Reed’s last album, Everybody Gets the Blues (Smoke Sessions: 2019). In his review of that album, JazzTimes’ Matthew Kassel described Reed as “one of the most reliably good pianists in the gospel-jazz tradition.”

That tradition is intrinsic in Reed’s playing. When asked about his influences, he responded: “You have to go all the way back to the piano players I heard in church. These people had a tremendous impact as my early influences.” Another early influence was pianist Bobby Timmons, who also had a church background, playing organ in his grandfather’s church

at age six. “Bobby Timmons,” Reed said, “was my next door neighbor’s best friend. He let me play the piano sitting on his lap.” All he remembers of that is “some dude who had these long skinny fingers,” but his neighbor later told him who it was.

Now 50, Reed enjoys listening to some of the younger pianists emerging on the scene today such as Aaron Diehl, Emmet Cohen, Christian Sands, and Sullivan Fortner. Fortner, he added, “has a certain kind of reckless abandon. He reminds me that I don’t have to be quite so much in control. Don’t control the music. Let the music breathe.” And, he enjoys playing standards from the Great American Songbook. Sammy Cahn, he said, “has to be in the top 10 of composers.” But he also likes to play tunes written by Rodgers & Hart, Gershwin, Duke El-

“

trumpeter Clora Bryant. “These were legendary jazz musicians on the West Coast,” he said. “Playing with them was a warm, positive, loving experience. I was young enough to be their grandchild.” Then, in 1989, Wynton Marsalis heard him play during a master class and hired him to succeed Marcus Roberts in his septet. That was a different kind of experience. “Now, I was playing with younger musicians closer to my age. There was a certain kind of intensity that was a little unnerving. I hadn’t been on the road. It was awakening with a bang. No transition—from a medium burning flame to high boiling.”

Another unique experience was an opportunity to play at Bradley’s, the popular jazz bar in Greenwich Village. “The first time I played there,” he said, “was in 1992. Wendy took a chance on me. (Wendy Cunningham, was the

YOU HAVE TO GO ALL THE WAY BACK TO THE PIANO PLAYERS I HEARD IN CHURCH. THESE PEOPLE HAD A TREMENDOUS IMPACT AS MY EARLY INFLUENCES.”

lington, and Cole Porter. And, Everybody Gets the Blues included a medley of Lennon and McCartney’s “Yesterday” with Jerome Kern’s “Yesterdays” and Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing”, heard on the tail end of Cedar Walton’s “Cedar Waltzin’”.

As a teenager in Los Angeles, Reed received some early guidance from veteran LA musicians such as bassist Red Callender, saxophonists Buddy Collette and Teddy Edwards, and

widow of Bradley’s owner, Bradley Cunningham). She had me in there a few times, and I was able to play there for four years (Bradley’s closed in 1996). “You could see the whole spectrum there—Cecil Taylor and Hank Jones, and they were there to hear John Hicks. That was my education. So many of the bebop cats were there—Clifford Jordan, Junior Cook, Dexter Gordon, Dizzy, Walter Davis, Jr. I’m very proud of that experience.”

09 SEP—OCT • 2020 NJJS.ORG

TALKING JAZZ

A Jersey Jazz Interview with Lucy Yeghiazaryan

BY SCHAEN FOX

Immigrants enrich America,” is an old truism, and this interviewee is more proof of it. While she was born and spent her early years in Armenia, New Jersey has also played an important role in Yeghiazayran’s development. She is an exceptionally talented artist with an interesting story to tell. Despite the pandemic, Yeghiazaryan was scheduled to have two live gigs in August: an outdoors performance in front of Tavern on George in New Brunswick on August 20 and a livestreamed performance at Chris’ Jazz Café in Philadelphia on August 22.

JJ: I see that while you use the name Lucy, your name is really Lusine. Which do you prefer?

LY: Everyone calls me Lucy. Lusine is a very common name in Armenia. I use it when I’m back home. It means “moon.” People had too much trouble saying it here, so I stopped using it.

JJ: Your website bio states that, “years before she ever learned to speak English, she began singing the tunes by meticulously mimicking the sounds and styles of the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan.” Did you sing in English in public?

LY: My mother knew that my sisters and I were pretty good singers from an early age. So, she put us on stage very early on. At seven or eight we were singing Armenian music then. My dad was a big jazz fan so we had a lot of records at home. That was something I only did at home. I only sang Armenian on stage. It was only after immigrating here that I decided to sing jazz publicly.

JJ: How did your dad build a collection of then forbidden jazz records in the Soviet era?

LY: Well, my father is an artist, a wood carver. His name is Mels, and in our town people always called him “Mels the Artist.” Being involved in the cultural circles that he was in, he came across things he wasn’t supposed to have. He knew a couple of guys in the National Jazz Orchestra in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Since they were one of the very few groups allowed out of the country at that time, some of the guys could sneak things back; and they got passed from hand to hand.

JJ: Your whole family immigrated straight to New Jersey. What was that like for you?

LY: We immigrated straight to a very rural town called West Milford, because my mother was working there. I don’t think by her own choice, that was just where the work was. We moved there a couple months after 9/11. My

“ SHE PUT US ON STAGE VERY EARLY ON. AT SEVEN OR EIGHT WE WERE SINGING ARMENIAN MUSIC.”

10 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

IMAGE BY YOAV TRIFMAN

sisters and I didn’t speak any English but were forced to go to public school immediately. In a cultural sense it was not pleasant. It was a hostile environment for immigrants in a town where there were no immigrants. We were the only outsiders. It was a strange welcome to a country that I thought was a country of immigrants. It turned out that it was not. My family and I were very confused initially, but I lived in that town until I graduated from high school. In middle school, I joined this Jazz for Teens program based out

of NJPAC. That was really the first time I sang jazz. They had a rhythm section of older guys that would come in and play with the singers. It was a good experience for a young person. I did that for a few years, and started actually gigging around New Jersey.

JJ: Who were some of those older guys that we might know?

LY: At the time the whole program was run by Don Braden, Mike LeDonne, Valery Ponomarev, Joris Teepe and others. It was great. A lot of times the guys

were touring, so they would have subs, so you got to meet a lot of real people who were actually working in the field. It was a very real example of what was to come, if you decided to go into jazz.

Having played with the rhythm section at that age was really helpful for me, because singers don’t get enough of that early on, even if you go into college as a singer. For some reason, the instrumentalists and vocalists are kept separately. Because of this you’re really just lacking in experience when you actually get out there. You don’t know what you are doing because you’ve never actually done it. Having that band with us once a week gave me a strong foundation in how to clearly communicate with a band.

JJ: You attended William Paterson University, but not for jazz. Why?

LY: I decided to go to William Paterson for jazz, but I realized it wasn’t my cup of tea, shall we say. I graduated with a world history degree, which I have never used. My mother told me, “You have to get a degree. I don’t care in what, but you have to get a degree.” I took something I was interested in and had a good time. I enjoyed the reading. I wanted to do Russian history, but William Paterson didn’t have that. I never liked Russia, because of its prolonged influence on my country. I figured I should know more about it if I’m going to hate it.

All throughout college I stayed very close to the jazz program. I just wasn’t in it. It was a great experience. I was always at Shea (Shea Center for the Performing Arts), and people would have jam sessions in their houses , and I would always try to go, so I was involved. I would make sure that if anyone was willing to play, I was there to sing. The crazy thing is, by not being a jazz major I ended up singing with more people than any vocal jazz major there. That speaks

11 SEP—OCT • 2020 NJJS.ORG

IMAGE BY YOAV TRIFMAN

to the issue within jazz education regarding vocalists. All the programs are separate. On occasion they will put a singer in an ensemble, but it is too rare. You don’t give them enough time to figure out how to run a band. You end up with singers that are hesitant due to a lack of any real experience.

William Paterson gives you a very real picture of what’s to come. It has a strong emphasis on straight ahead jazz, and that can be rough around the edges, which I really like. I think it produces a lot of good musicians because it doesn’t try to gaslight you in any way. I really, really love and respect that about this school.

I’m so glad I initially moved to New Jersey instead of New York, because there is a very strong group of jazz musicians in Jersey who are great musicians yet are very humble people. They come do their thing in New York then go home and don’t brag about it. There is just a relaxed attitude about it, that’s all. I like that approach and always respected the New Jersey jazz musicians.

JJ: What was your process for learning English and how long did it take you?

LY: My sisters and I were quiet for a good year and a half just listening and trying to learn the language from school and television mostly. I was about 11 or 12, so at that age it only takes about a year to grasp a language when you’re living in it.

JJ: What languages do you speak?

LY: Armenian, Russian and English.

JJ: How did your family react to your decision to make music your career?

LY: I was the only person in my family to question my career; everyone else has always seen it as the only natural route for me.

JJ: Right after graduating from college, you did perform with the National Armenian Jazz Orchestra. How did that happen, and what was that like?

LY: I think that for anyone that immigrates at the age I did there is a kind of calling back, and you never feel completely settled. I hadn’t been back home in years and decided to go and see what was happening. I stayed for about a year. I was hanging at a club in Yerevan, our capital, and I don’t know how this guy knew me, but he said, “I know you. You’re a singer. Why don’ you come up and sing?” I went up and sang, and some guys from the orchestra were there who told the director. He called me the next day. I worked with them for

JJ: You left New Jersey for a jazz career in New York City. How difficult was it to find your place in the city’s jazz community?

LY: It was probably three years or so before I was earning my money just by singing. I just wasn’t working enough. I had to pay rent. I sold a couple of instruments I had. I sold my mandolin, my old violin. I had all sorts of weird jobs in the beginning. I was a tour guide, waitress, sold some art etc. That was rough. The first two years were rough, but I think I’ve been lucky in some ways. I don’t get a lot of work on my own, but I’m hired as a side person a lot, which makes my life easier in some ways. People started calling me because I’m reliable.

“ I THINK IF YOU DO SOMETHING YOU LIKE WELL, THEN, THE AUDIENCE WILL LIKE IT.”

a couple of months while I was there. For such a small, secluded country it does have a strong commitment to jazz. Last year I did the jazz festival there with [saxophonist] Grant Stewart. We did a couple of gigs at smaller clubs in town outside of the festival, and they were packed with people either my age or younger, which is rare here. Jazz audiences here tend to be older. This place was packed. Grant was playing with a pianist named Vahag Hayrapetyan. They were playing bebop tunes, and the entire room in the back was just singing along the way you’d sing “Happy Birthday”. I was amazed. I never see that here. It’s odd to see that outside of the country. There has been a love of jazz in Armenia since the Soviet era, and I think it’s become stronger with the internet since you have a lot more access.

JJ: Your shows I’ve seen were heavy on American Songbook classics. Is that your usual, or did you read your audience and adjust to their jazz taste?

LY: No. I’m not usually trying to please the audience. I think if you do something you like well, then, the audience will like it. I’ve always liked good songs. If it is a good song, I’ll sing it. It just happens that a lot of those songs are in the American Songbook, and I just end up singing those tunes. Schools today also push original compositions. I was never the kid making up songs. I was always learning songs. I like songs that everybody knows, and finding obscure songs and presenting them in a way that feels familiar to people. Every show is different, because you do have to feel the audience out to a certain degree. It is hard to get to that point,

12 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

JAZZ

TALKING

where you can just look out and feel this tune would be good, because, early on, you are just too nervous to be thinking of that. You make a list, and you play the list down in the order and tempos you had written. It is hard to break out of that, but once you feel a little more comfortable, you become better at reading the audience, and that is an extremely important tool to have. Having worked with older musicians that I really respect in the last couple of years, and seeing them do that has made me more relaxed and more willing to make it up as I go. (Yeghiazaryan’s debut album in 2019, Blue Heaven, on the Cellar/Cellar Live Records label, included such standards as Oscar Hammerstein

and Jerome Kern’s “Nobody Else But Me”, Rodgers and Hart’s “Thou Swell”, and, of course, Walter Donaldson and George A. White’s “My Blue Heaven”).

JJ: Who are some of those “older” musicians and how have they affected your career?

LY: I play with Grant Stewart a lot. He is somebody who doesn’t say much, but leads by example. He’s humble and relaxed on stage, but in my opinion is one of the best tenor players alive. He does it because he loves it, and does it so well and naturally. Just observing him has been a pleasure and a learning experience. (Of Yeghiazaryan, Stewart says: “Lucy has it all, an incredible tone, time

that drives the band, and that other ‘something’ that makes you say this is the real thing. Definitely one of a kind.”) Tardo Hammer, a piano player I’ve been playing with, is a big risk taker. A lot of times I don’t know where he is going musically speaking. He adds an element of surprise and spice that I like, because it forces me to sing things I wouldn’t otherwise. Earlier when I lived in New Jersey, I used to play with Winard Harper, who’s a showman and has an ability to set the audience at ease, whether it’s through humor or his relaxed way of playing.”

JJ Please tell us about your visual art. My mother is an art therapist for children, so she spent a ton of time with us kids, especially in Armenia in the ‘90s when there was no electricity .

I’ve always felt that I’m a better singer than I am an artist. But I’ve always loved it, and it is what I do to relax. It is an art form that I can practice on my own without having to deal with other people.

JJ: Of all your jazz heroes which are the most interesting to you as people, not artists?

For me, everything begins and ends with Ella. I really also love Etta Jones. Guys that I play with that played with her say she was a sweetheart. You hear stories about singers who were rough leaders. But when I hear about women that didn’t act like that, I think that is harder to do. It is harder to stay kind when you haven’t received much kindness. So yeah, people like Ella and Etta Jones who were notoriously kind, did their thing well and kept their cool.. I’ve always admired those women. I try to have a close relationship with guys I play with, not belittle them in any way, but make them feel that we are all part of the music, that I’m not necessarily the leader, but that WE are the band.

13 SEP—OCT • 2020

RISING STAR

Alto Saxophonist Sarah Hanahan

Mixing a ‘Powerful, Fresh Sound’ with a Healthy Respect for Tradition

BY SANFORD JOSEPHSON

When she was growing up in Marlborough, MA, Sarah Hanahan’s father, a drummer, would show her videos of the Buddy Rich Big Band. “We used to sit and watch them together,” she recalled, “and I was fascinated by the visual images and the amazing saxophone section. By the time I was eight years old, I said to my dad, ‘I really want a saxophone for Christmas.’”

She received the saxophone and went on to play lead alto saxophone for the Marlborough High School jazz band, winning a full scholarship to study jazz performance at the University of Hartford Hartt School of Music’s Jackie McLean Institute. At the audition for her college acceptance, Hanahan played “I Hear a Rhapsody” (recorded by Jackie McLean on his 1960 Prestige album, Makin’ The Changes). McLean, she said, has been her biggest influence. “I learned so much about him from [bassist] Nat Reeves and [trombonist] Steve Davis, who were faculty members and played with him. They shared so much with me about Jackie’s life and music.”

McLean, who died in 2006 at the age of 74, was one of the young lions of the bebop era, playing with Bud Powell, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, and Charles Mingus, among others. He arrived at the University of Hartford in 1970 as a Music Instructor at the

Hartt School. In 1980, he was named Director of the newly-formed African-American Music program, which was renamed the Jackie McLean Institute of Jazz in 2000.

Reeves, Hanahan said, “is really like my mentor. He was Kenny Garrett’s bass player. He used to pull me up on stage even when I wasn’t ready. I’m so grateful to him for that.” Hanahan’s playing was also greatly influenced by another faculty member, saxophonist Abraham Burton. “He changed everything about the way I played,” she recalled, impressing upon her the importance of ballads. His advice: “I want to hear you play

slow and really mean it on every note that comes out of your horn. I don’t care how fast you play. I know you can burn. Let me hear you play soft. You need texture. You need dynamics.”

According to Davis, Hanahan is “the real deal. She has the fire! Her alto sound is powerful, fresh, and unique. At the same time, you can hear the tradition in her playing and her concept as an improviser and budding composer.”

On March 14th of this year, the Sarah Hanahan Quartet appeared at the Side Door Jazz Club in Old Lyme, CT. The band included three young musicians – Hanahan, pianist Zaccai Curtis, and drummer Michael Ode, plus the veteran, Reeves, on bass. The Side Door gig, said Hanahan, “was my very last show” before live performances were ended by the coronavirus.

Canceled dates included scheduled performances with the Diva Jazz Orchestra March 19-22 at Dizzy’s Club in New York and a March 28th date at Kenyon College in Gambier, OH. Drummer Sherrie Maricle, who leads the Diva Orchestra, first heard Hanahan play last year at the Jazz Educators Conference in Reno, NV, as part of a Sisters in Jazz group. “I immediately heard that she was an extremely gifted player,” Maricle said. “She had great feel, sound, personal style, and a lot of creativity. Once I discovered she was also an excellent reader and woodwind doubler, I knew she would be a perfect fit in the Diva Jazz Orchestra, and she has been subbing with us ever since.” Hanahan also had plans for a week-long engagement with pianist Jason Moran at the

14 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

As a result of the live music lull caused by Covid-19, the 23-year-old Hanahan left her home base of New York City for her family’s home in Marlborough “to slow down and focus on a lot of writing and get ready for school in the fall.” “School” is the Juilliard School where she will be studying for a Master’s Degree in Jazz Studies.

New Jersey jazz fans had an opportunity to see Hanahan this past December and January. On December 20, 2019, she was part of a big band led by drummer Evan Sherman at the New Brunswick Performing Arts Center, and on January 20, 2020, she performed with trombonist Mariel Bildsten’s septet in a tribute to Duke Ellington and Count Basie at the Morris Museum’s Bickford Theatre in Morristown. At that concert, Bildsten thanked Hanahan for introducing her to Ellington’s “Lady of the Lavender Mist”, one of the alto saxophonist’s “favorite songs”, which the septet performed. “It was a beautiful moment,” Hanhan recalled, adding that she met Bildsten when they were playing in an all-female band at Yale. “We hit it off musically and personally.” Sherman and Hanahan met during a jam session at the Smoke jazz club on New York

City’s Upper West Side. “It was great to play and bounce off each other musically,” she recalled, “and that’s when we started working together.”

A lot of saxophonists, Hanahan said, “eventually change over to tenor, but I love the alto.” She feels a “spiritual connection” to Jackie McLean, but “of course, I’m also influenced by Charlie Parker and John Coltrane.” Added Davis: “I also hear her Kenny Garrett influence. I’m very proud of Sarah. I’m excited to hear where she’s going to take the music.”

NJJS.ORG

Sarah Hanahan, 2nd from left, with the Diva Jazz Orchestra. Others, from left: tenor saxophonist Scheila Gonzalez, alto saxophonist Alexa Tarantino, tenor saxophonist Sharon Hirata, and baritone saxophonist Leigh Pilzer.

WPU SUMMER JAZZ ROOM SERIES

Four Online Concerts in a Safe But ‘Surreal’ Environment

BY SCHAEN FOX

William Paterson University’s jazz program is a jazz mecca. It is staffed with major jazz luminaries and attracts students from all around the country and the world, some on Fulbright Scholarships. Jazz fans have also enjoyed the decades long public Jazz Room concerts held each season. Adapting to the chaos of 2020, caused by the coronavirus, Tim Newman, Producer of the Summer Jazz Room Series, and Al Schaefer, Director of Operations,

held the summer four-day series online. Normally, the concerts are priced reasonably; this year it was a paywhat-you-will or free event, available on the Jazz Room website.

As always, it was held in the Shea Center for the Performing Arts. To make it as safe as possible, musicians were spaced about 10 feet apart and encouraged to use masks when possible. Bottles of hand sanitizer were available as were clear plastic panels. A newly installed UV-air filtering system helped ensure that the center’s air was both refreshingly cool and pathogens free. That is a permanent facili-

ty improvement. The broadcasts had good quality audio and video, but seeing musicians playing in an empty theater did add a mildly surreal element.

On July 21, pianist Richard “Tardo” Hammer, bassist Lee Hudson and drummer Steve Williams opened the 27th series. I became a fan of Hammer when I first heard him backing Warren Vache at Shanghai Jazz. He updated me on his routine during the pandemic. “I’ve been able to keep up with most of my teaching via online conferencing, and it’s working better than expected. I’m holed up with a good bunch of people, that is, my wife, two kids and a dog, so it keeps me moving. Really very fortunate so far. The extra time that I don’t spend on the subway has paid off with extra time for practice and exercise.”

The versatile Hammer has a light touch on the piano that reminds me of Teddy Wilson, but his technique and musical vocabulary show an affinity for the bebop masters. The program consisted of classics, such as Richard Rodgers’ “I Didn’t Know What Time it Was,” and lesser known gems, such as Duke Jordan’s “No Problem.” Talking between numbers was minimal, so the standard-length set was filled with wonderful music.

Later, Hammer told me, “We were happy to be playing together again. It’s good to have the other musicians there for camaraderie, support and interaction.” He probably smiled as he concluded, “An empty theater is strange, but we’ve all played under strange circumstances in the past. I have, on occasion, played to emptier spaces!”

The second evening, July 22, featured vocalist and William Paterson alumna Alexis Cole performing with an all-star group: trumpeter Joe Magnarelli, saxophonist Don Braden, trombonist and William Paterson

16 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

IMAGES BY BOB VERBEEK, WILLIAM PATERSON UNIVERSITY

Tardo Hammer

faculty member Newman, pianist Ted Rosenthal, William Paterson alum bassist David Finck, and drummer Joe Spinelli. Jeremy Pelt was scheduled to play, but a last-minute car problem forced them to scramble for a replacement. Magnarelli rushed over, played the charts cold, once again demonstrating why he has a stellar reputation.

This was the only vocal set of the series, with Cole singing jazz and songbook classics ranging from Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz” to Billy Joel’s “New York State of Mind.” She often added interesting and pertinent information as well, ranging from her experiences at her beloved alma mater to her years in the Army stationed overseas. Speaking about how she felt performing again, she said that, while rehearsing with her pianist, “Ted played three notes of the song, and I just burst out crying uncontrollable sobs. This is the first time I’ve sung with anybody since this started in March, and it was very emotional for me.”

Rosenthal later told me, “I think we all felt it in different ways. It was great to be with everyone, but I was

still conscious of social distancing. It was great to be back, but you could also feel differences and had to experience a new normal for a while.” The musicians all rose above the odd situation, however, and played to their usual high standards.

The third evening, July 23, brought Hammond B3 organist Akiko Tsuruga, leading another outstanding group: Magnarelli, trumpet, Jerry Weldon, tenor saxophone, WPU alum Charlie Sigler, guitar, and Joe Farnsworth, drums. Tsuruga, DownBeat’s 2020 Rising Star organist, who has left Japan to live here, truly seems most at home at the Hammond B3. It can almost sound like a big band, and she expertly makes it roar or purr softly. Her set included standards such

as Horace Silver’s beautiful “Peace,” and some of her own, compositions such as “Dancing Cat.” It all had the mood and the quality of the great organ groups of the past.

The final event, on July 24, provided a unique ending to a historic page in the Jazz Room series. Trombonist and shell master Steve Turre brought in a band of mostly young talents: saxophonist Emilio Modeste, trumpeter Wallace Roney, Jr, pianist Isaiah Thompson, bassist Dezron Douglas, and drummer Orion Turre. They played mostly Turre’s originals that are due to be on his next CD. He only played his shells late in the set before it was terminated by a false fire alarm.

Dr. David Demsey, WPU Coordinator of Jazz Studies, expects that

“ AN EMPTY THEATER IS STRANGE, BUT WE’VE ALL PLAYED UNDER STRANGE CIRCUMSTANCES IN THE PAST.”

the fall Jazz Room series may be a mixed event where a few hundred fans can attend the concerts while others will again view them at home. Added Rosenthal: “We all had certain trepidations about how things would be handled in terms of distancing and cleanliness. I was very pleased with how the staff and everyone put thought and execution into making the experience as risk free as it can be. I would do it again.”

The music, as mentioned, was free, donations can be made by logging onto the university’s home page, wpunj.org, and clicking on the blue Give to WP tab on the top right of the page.

17 SEP—OCT • 2020

IMAGES BY BOB VERBEEK, WILLIAM PATERSON UNIVERSITY

Alexis Cole

BIG BAND IN THE SKY

Remembering Jerry Bruno

BY RUSS KASSOFF

Ifirst met Jerry in 1976, and we did club dates and private parties where I had the steady solo piano gig, and he often subbed in the trio. We also did society gigs with Peter Duchin and Jerry Kravat. ( Bassist Jerry Bruno died at the age of 100 on June 22, 2020: https://njjs.org/index.php/2020/06 /25/bassist-jerry-bruno-bucky-andme-were-like-melted-together)

My name got around the Italian Musicians Mafia—which included Nick Perito (Perry Como), Domenic Cortese (accordionist in everything including The Godfather!), Joe Malin (Sinatra’s contractor and the concert master of his orchestras), and Bucky Pizzarelli of course. I started with Sinatra in 1980 and Liza Minnelli in 1982. Jerry had already left his mark having toured with Liza in the early ‘70s, and the stories from those tours are legendary and, for the most part, unprintable!

I got a call from Bucky in 1982. At the time, he had his trio at the Cafe Pierre—a steady gig five nights a week with the legendary Tony Monte at the piano, and the wonderful Ron Naspo on bass. Both sidemen took off more than half the time because then, in the heyday of live work, they had plenty of accounts and people to play for, so they both needed subs. One such sub with regularity was Jerry Bruno. Jerry and I inherited the bass and piano chairs as both Tony and Ron became so incred-

ibly busy. They both became our subs!

Since Jerry and I had such a vast repertoire rivaling Bucky’s we all enjoyed playing just about any tune. It was the same 10,000 songs over and over again!

During this period (’82-86’) we recorded albums with Red Norvo (Just Friends), The Cafe Pierre Trio, and went into the studio with the opportunity to use studio time to record John Jr’s first album—I’m Hip— Please Don’t Tell My Father, featuring the first recording of John’s smash hit,

“I Like Jersey Best”. Jerry was an integral part of all of these recordings and

Joe Parnello, and played alongside the great guitarist Tony Mottola, bassists Gene Cherico and the amazing Jim Hughart. In the mid-‘80s we toured together several times.

Jerry and I would always play for Sinatra’s opening acts—Charlie Callas, Shields & Yarnell, Tom Dreesen, and even Nancy Sinatra. Sometimes Jerry would play section (orchestral) bass and I would stay at the piano to play for Frank except when Bill Miller would sit down and play his timeless accompaniment of “One For My Baby”. Vincent Falcone also sat down from the podium to accompany magnificently for Frank from time to time. On the day that Costa died, January 19, 1983, Jerry walked into the Cafe Pierre down the marble steps and came over to Bucky and myself and just said “Costa died.” He was at the recording studio when the word got out to the orchestra. Don Costa was

during these years was in the studios— primarily Nola run by recording engineer legend Jim Czak—much of the time doing a long list of independent recording projects.

Jerry recorded on 10 different Sinatra recording dates from 1968 (Cycles, Whatever Happened To Christmas ) until 1982 (Trilogy—1979, She Shot Me Down with Gordon Jenkins 1981) mostly under the leadership of Don Costa. He also played section bass under the batons of Bill Miller, Vincent Falcone,

his best friend; he sat down and toasted with a bottle of wine.

From then until about March 2017 we did all the things free-lance musicians would do. Jerry always had kind words to say about everyone and always enjoyed the role of contractor— the guy making the calls to book the band for club dates, shows, restaurants galore. I had the good fortune of getting those calls and playing at one time or another for all of them. He was always the shining light in the middle of the

18 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

ALWAYS HAD KIND WORDS TO SAY ABOUT EVERYONE AND ALWAYS ENJOYED THE ROLE OF CONTRACTOR—THE GUY MAKING THE CALLS.

JERRY

room. Folks just gravitated to him. In his later years, every restaurant where we’d go out to eat after a rehearsal or event there were always strangers sitting nearby who were magically attracted to him. The ladies loved him! He loved the attention and often would make a Yogi Berra-like comment about an obvious but mundane thing.

On one of these dates around 1986 Jerry called me and said we were going to get picked up in a van and taken to Philadelphia to do a morning TV Show (AM Philadelphia) for his regular client Charles Kelman, the world famous ophthalmologist who is credited with inventing Lasik surgery and who also played the alto saxophone and had a show. It was close to the date and he asked me to get him a drummer. I had just done five weeks at Michael’s Pub with Annie Ross, and

our drummer was none other than the great Mel Lewis. Knowing he was up late at night I gave him a call and he agreed to be picked up in the van at 3:30 a.m. to go to Philly to perform live on the day of the show! Now for me, it was a thrill to spend any time with Mel just to hear his stories. It was like having a talk radio show on without commercials. We had a great gig and an equally great trip back!

In 1980, as a result of Jerry’s support, I got the call to begin what was an intermittent 11-year stint playing piano in the Frank Sinatra world, my moments—musical and onstage—with Sinatra were magical, and he gave me the nickname “the kid”. Whenever they needed a pianist for a show, Sinatra would tell Joe Malin, the contractor, to get “the kid!”. Now in my late middle age, I’m no longer the kid,

but I feel a responsibility to try to give some musical meaning to the lives of my elders who have been leaving us at an alarming rate, especially now. My numerous, almost weekly visits with Jerry Bruno were priceless.

As he reached his upper 90s, he was fully aware of the physical limits of his bass “chops”. In retrospect, it was an honor for me to sit with him at the piano and guide him through songs in the last years fully accommodating his limitations. I know he loved that.

As the gigs got less and less, and his friends passed on, it became imperative to maintain that raison d’être.

I did as much as I could helping to create several dates in restaurants with proprietors who treated him with the most respectful adulation: Shanghai Jazz in Madison, NJ—(Tom Donohue—proprietor); The Glen Rock Inn—where over the years he played with Bucky, and Al Caiola, booked by Arlene Rosenberg after her husband Shelly passed; Maureen’s Jazz Cellar in Nyack NY, owned and operated by the wonderful pianist David Budway and his wife Brianne Higgins; and finally the last gig we did together along with vocalist Catherine Dupuis on Jerry’s 25th Leap Day— February 29, 2020—at Division Street Grill in Peekskill, NY, hosted by Arne Paglia who adored all things Jerry and Bucky. We cannot thank them enough for always welcoming and loving Jerry and allowing me to be a small part of his 100 years!

Anyone who encountered Jerry by way of the music, stories, eating—it’s time to smile. R.I.P.

Russ Kassoff, a pianist and composer, hosts “The Jazz Deli” on Saturday mornings on WFDU, 89.1FM. CONTINUED

19 SEP—OCT • 2020 NJJS.ORG

ON PG. 34

Jerry Bruno, left, and Russ Kassoff

CENTRAL JERSEY JAZZ FESTIVAL

Alexis Morrast, Matthew Whitaker & Mark Gross In 3-Hour Virtual Concert

BY SANDY INGHAM

he Central Jersey Jazz Festival—normally held on three days at three different locations— has adjusted to the coronavirus environment and will present one three-hour virtual concert on Sunday, September 13, from 1-5 p.m. The concert will be streamed free on centraljerseyjazzfestival.com as well as on YouTube ( youtube.com/channel/ucsi6t-wopwlpjkefqroessg ) and Facebook (facebook.com/centraljerseyjazzfestival).

The lineup: Vocalist Alexis Morrast, sponsored by Flemington, Hunterdon County seat at 1 p.m.; pianist Matthew Whitaker, sponsored by New Brunswick, Middlesex County seat at 2:30 p.m.; and alto saxophonist Mark Gross, sponsored by Somerville, Somerset County seat at 4 p.m.

Eighteen-year-old Morrast started singing at age three and hasn’t stopped. Born in Newark, she lives with her family in Plainfield, NJ, and now attends the Berklee Col-

lege of Music in Boston. The Showtime at the Apollo winner has built a devoted following with performances at top venues such as the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, Dizzy’s Club, and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. Hot House Magazine presented her the “best up-and-coming young artist” award in 2017. Morrast also performed at the New Jersey Jazz Society’s 45th anniversary concert in October 2017 at Drew University in Madison, NJ, and in March 2019 at the Jazz on a Sunday Afternoon series at the Jay and Linda Grunin Center for the Arts in Toms River, NJ. NJJS is a proud media sponsor of the JOSA series.In 2019, she performed with Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra’s Big Band Holidays tour.

This writer first saw Morrast at an outdoor concert in New Brunswick in 2017. At 15, the rich voice and the passion and poise she displayed in exploring the Great American

20 SEP / OCT • 2020

JAZZ

JERSEY

MARK GROSS(LEFT) BY ADRIANA MATEO

Mark Gross

Alexis Morrast

Songbook was reminiscent of Ella, Sarah or Carmen. When Morrast appeared at the Nyack Center in Rockland County this past February, the Nyack News & Views’ Melanie Rock described her as “a young vocal phenom. She’s a compelling performer.” Morrast will perform with a quartet at the CJJF.

Whitaker, a 19-year-old keyboard prodigy from Hackensack, NJ, has triumphed over seemingly insurmountable odds in his young life. Born prematurely and blind, as an infant he underwent 11 operations aimed at giving him eyesight. They failed, but at age three, his gift for music was discovered when he was given a toy keyboard and began playing the nursery songs he heard, chords and all, without any instruction. It was soon clear his perfect pitch enabled him to play complex compositions after a single hearing.

He learned to read music via Braille, a skill he’s put to use as a composer and arranger. By age 11, he was playing for the public and has toured the world playing both piano and Hammond B-3 organ.

A CBS-TV 60 Minutes profile earlier this year included interviews with his parents, instructor, and a neuroscientist who marveled at Whitaker’s improvisational flights of fancy and persuaded him to allow a brain scan while he listened to music. The finding: his visual cortex “lit up” with the music, helping explain his extraordinary gift.

“

in the jazz heritage, but full of modern attitude, tone, and vocabulary.” DownBeat’s John Murph, writing about Gross’ 2012 Jazz Legacy Productions album, Blackside, wrote that Gross “deserves greater recognition,”

Co-hosts for the three-hour concert will be Virginia DeBerry, co-founder of the New Brunswick Jazz Project, and Sheila Anderson, host of WBGO’s “Weekend Jazz After Hours“and founder of the Somerville Jazz Festival. In a joint statement, they said: “We are happy that despite the Covid-19 pandemic, we will be able to present the 2020 Central Jersey Jazz Festival virtually! It took a minute for us to determine how to revamp our originally planned event for a livestream one, but the CJJF team from Flemington, New Brunswick, and Somerville collaborated, as we usually do, and found a way to make it work. Team work and improvisation, cornerstones in jazz, are essential in any partnership. Now in its 11th year, the CJJF team is committed to presenting great artists. We are grateful to our partner and presenting sponsor, RWJ/Barnabas Health for their continued support, especially in these difficult times!”

DESPITE THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC, WE WILL BE ABLE TO PRESENT THE 2020 CENTRAL JERSEY JAZZ FESTIVAL VIRTUALLY!”

Critics have lauded Whitaker’s shows and his two albums, Now Hear This (Resilience Music: 2019) and Outta The Box (Jazz Foundation of America: 2017). George Kanzler, the former Star-Ledger jazz writer now freelancing for several jazz magazines, called him “the very essence of a musical prodigy.” Whitaker will lead a quartet at the CJJF.

Gross will lead a quartet in the CJJF finale. The son of a Baltimore pastor, the 54-year-old alto saxophonist grew up on gospel music and mastered jazz at the Berklee College of Music. He’s worked in numerous big bands, including the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band, the Village Vanguard Jazz Orchestra, and the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Having performed on more than 40 jazz recordings, he also played on two Grammy Award-winning albums recorded by the Dave Holland Big Band— What Goes Around (ECM Records: 2002) and Overtime (Dare 2 Records: 2005).

Japan’s Swing Journal called Gross “a powerful alto sax player who is a Cannonball type player. As you may presume—funky is his flavor. He shows his modern modality, which is reflected in his sound.” Jazz Sensibilities’ Stamish Malcuss, reviewing his 2018 MGQ Records’ album, +Strings, wrote that Gross’ “approach to the horn is based

Matthew Whitaker

NJJS.ORG

MARK

BY ADRIANA

GROSS(LEFT)

MATEO

MUSICAL JOURNEY

Jerry Weldon

From Lionel Hampton to Harry Connick

BY SCHAEN FOX

Jerry Weldon started to play saxophone when he was in high school, but the turning point in his musical life happened when his father took him to see Stan Getz at the Village Vanguard. “That did it,” he said. “That is when I said I wanted this to be my life’s work.” Weldon never got to tell Getz that story. “I got to meet him on a few occasions, but well, as Zoot Sims said, ‘Stan was a nice bunch of guys.’ I just said hello. He was very nice, but I didn’t go through all of that with him.”

Weldon found more great influences at Rutgers University. “That is really where it came together for me, where I found the way I was going to play, and my identity, music wise. I studied under Paul Jeffrey who started the jazz program at Rutgers and really put it on the map. He was my mentor. He worked with Monk after Charlie Rouse. He also worked with Dizzy, Illinois Jacquet, and Mingus. . He molded my style and did a lot for me.” Another influence was pianist Kenny Barron. “He was a great teacher. I was in his piano class. I hadn’t played piano until I got to college. When I got into Kenny’s class, he showed me basic voicings. Coupled with that, I was transcribing solos. So, it came together then. He was a really good part of my development.”

Like everyone in the jazz community, Weldon’s live gigs disappeared because of Covid-19. He was, howev-

er, back on the bandstand on July 2, playing with his trio from 7-10 p.m. in front of New Brunswick’s Tavern on George, a revival of live jazz concerts sponsored by the New Brunswick Jazz Project. “I think we’re a long way away from ‘normal’,” he said at presstime, but “we really had a great night. The crowd was very receptive, tables

“

I GOT PHOTOS TAKEN WITH PRESIDENTS BUSH AND OBAMA. I JUST MET THEM, SHOOK HANDS, SAID HELLO AND TOOK THE PICTURE.”

were set up outdoors on George Street, everyone was masked and distancing nicely.” Weldon’s trio played two sets, which included Jimmy Smith’s “The Sermon” and Dexter Gordon’s “Catalonian Nights”, among other “straight ahead and swingin’ tunes.” The NBJP scheduled Thursday evening performances through the summer.

In addition to formal classes at Rutgers, there were regular concerts sometimes held twice a week. “Larry Ridley, the chairman of the department, would hire a guest artist, say

Johnny Griffin or Barry Harris, Nat Adderley, Sonny Stitt, George Coleman, or Dexter Gordon, to come down with their band to play. We would play a set before whoever was to perform that evening. Sometimes they would play with us. That was quite an experience.” Classmates included: “Terence Blanchard (trumpet), Ralph Peterson (drums), Frank Lacy (trombone), David Schumacher (saxophone), John Bianculli (pianist), Adam Brenner (saxophone), Harry Pickens (piano), and Thomas Chapin, a great alto saxophonist, flautist, and composer. He made some great records and was gone way too soon.”

After graduating, Weldon made some recordings at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs. “Rudy was very meticulous and a private sort of a guy, but we had a good relationship. In fact, one time I was about to do a date there, and I looked at my record collection. I said, “I’ll bet 75 per cent of these were done at his studio.” I pulled a few out and took them to the date. One was Sonny Rollins on Impulse. In it was a picture of Rudy holding the door for Sonny as he walked into the studio. I showed it to Rudy. He got a kick out of it.”

Weldon’s big break was when Jeffrey told Lionel Hampton, “I have these really good students here at Rutgers who can really play.” Hamp said, “Well, send them over.” Chapin, Weldon said, “left school the year before I did and went right into Lionel Hampton’s band. Hamp just loved the way Tom played, and when an opening came up, Tom got me in. Then Adam Brenner came in. Then Dave Schumacher came in on baritone, so we had an all-Rutgers sax section for about five years with the band.

“That is where I learned to become a professional, the way he paced a set,

22 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

put a set together, followed one tune into the next. The way he spoke to the audience, his showmanship, and his persona. He was the complete package, a great musician, and also a great entertainer. The thing that I got the most from Hamp is how he gave 110 per cent every single night, every single night. He played every single show like it was going to be his last one.”

Being with Hampton got Weldon his first White House gigs. “I played for Reagan’s Inaugural and George H.W. Bush’s Inaugural; and we played the Governor’s Ball for President Obama in 2010 with Harry Connick.

I got photos taken with Presidents Bush and Obama. I just met them, shook hands, said hello and took the picture. The Governor’s Ball was a lot of fun and a very good night. We went in and had a rehearsal. Then President Obama came in and said hello to everybody. We took the picture, went back to the hotel, and later we went back to a fabulous night.”

Weldon was with Hampton for six years, from 1982 to the end of 1988. “Then I was in and out over the years,” he added. Eventually, he felt the urge to do something else. “I went with Jack McDuff after Hamp and played with

him, along with (saxophonist) Andrew Beals, another Rutgers alum, for many years, off and on from the ‘80s until he passed away in 2001. McDuff was a great arranger and composer. He had a very hip four horn book of alto, tenor, trumpet, and trombone. I made a bunch of records with him for Concord.”

The jazz organ format has long attracted Weldon. “In high school, a friend gave me those Blue Note records Stanley Turrentine made with Shirley Scott. I just loved those.”

The other big band that Weldon is closely associated with is that of Harry Connick, Jr., and that also began with Hampton. “I met Harry in New Orleans in 1984. We had a two-week stay at the Roosevelt Hotel. When you get two weeks in New Orleans, you hear and play a lot of music. I met great musicians like Wallace Davenport, Wendell Brunious, Ralph Johnson and Clarence Ford, a great saxophone player. The musicians are so warm. You are always welcome to sit in. It’s a great environment.

“Harry was still in high school, but he was working in the clubs quite a bit. When he came to New York, he played in Hamp’s band for a very short time. He remembered me, and we got to be friends. He told me he was starting his band, and would I be interested in doing that? I said, ‘Sure.’ That was 1990, and I stayed four years. It was a great band. We worked constantly. We were on television a lot, made some good records, went to Australia two or three times, and just traveled the world. I played in Windsor Castle with Harry for Prince Phillip’s 70th birthday. It was a great experience. He re-formed the big band at the end of the ‘90s, and I’ve been pretty much with him since then. Harry still writes just about all of the arrangements. He’s a fabulous musician.”

23 SEP—OCT • 2020

OTHER VIEWS

In these times there is a lot of time available to listen to music, a good thing when the new releases keep pouring into my mailbox. This issue will include mostly new discs but also some catching up with ones that have been accumulating in my stacks.

BY JOE LANG

» Organist/pianist Radam Schwartz has been an ubiquitous presence on the New Jersey jazz scene as both a player and educator, most notably as Music Director of the Jazz Institute of New Jersey, a youth program in New Brunswick. For about 30 years, Schwartz ran a weekly jam session, initially at the Peppermint Lounge in Orange and subsequently at the Crossroads in Garwood, that attracted many stars such as Etta Jones, George Benson and Jimmy McGriff. His latest release finds him fronting The Radam Schwartz Organ Big Band, the hard-swinging, groove-oriented aggregation found on Message From Groove and GW (Arabesque -AJ220). The program includes three Schwartz originals, one each by trombonist Peter Lin and saxophonist Abel Mireles, plus John Coltrane’s “Blues Minor,” “Ain’t No Way,” an Aretha Franklin classic, “Between the Sheets” from the Isley Brothers, and a taste of Bach, “Von Gott.” An album by Richard “Groove” Holmes and the Gerald Wilson Big Band served as an inspiration for this undertaking by Schwartz and crew. They have done a fine job of capturing the spirit of that recording. arabesquerecords.com

»

Alec Wilder is a composer too often overlooked among important

composers of classic pop. While the Wilder songs included when listing standards of the great American Songbook are limited, he was far more prolific than most would imagine, and his lack of recognition is most probably because his tunes tended to be more sophisticated than popular tastes found palatable. On Night Talk The Alec Wilder Songbook (Capri—74162)

The Mark Masters Ensemble featuring baritone saxophonist Gary Smulyan offers up a nine-song program that includes one selection that will be familiar to almost all listeners, “I’ll Be Around;” one quite popular with jazz players, “Moon and Sand;” and a couple that have been recorded by vocalists who dig deeply for fine tunes that fly under the radar, “I Like It Here” and “Lovers and Losers.” The balance of the tunes, “You’re Free,” “Don’t Deny,” “Ellen,” “Baggage Room Blues,” and “Night Talk” are all interesting but obscure. Masters has assembled a band comprising Smulyan, Bob Summers on trumpet, Don Shelton on alto sax and flute, Jerry Pinter on tenor and soprano saxes, Dave Woodley on trombone, Ed Czach on piano, Putter Smith on bass, and Kendall Kay on drums, matching the New York Citybased Smulyan with a cast of premier Los Angeles area cats. Smulyan takes to the Wilder material with fervor and an infectious creative spirit that matches the engaging charts

penned by Masters. Wilder, who was a jazz enthusiast, would surely have been happy upon hearing the results. caprirecords.com

»

For Jimmy, Wes and Oliver (Mack Avenue—1152) by the Christian McBride Big Band, featuring organist Joey DeFrancesco and guitarist Mark Whitfield, also draws its inspiration from earlier recordings, The Dynamic Duo and Further Adventures of Jimmy and Wes, two albums featuring organist Jimmy Smith and guitarist Wes Montgomery backed by a big band with arrangements from the ever imaginative Oliver Nelson. McBride’s big band appears on six of the 10 tracks, with the remaining four finding DeFrancesco, Whitfield, McBride and Quincy Phillips on drums playing as a quartet. Both groups have unmitigated swing in common. The large ensemble assays ‘Night Train,” “Road Song,” “Milestones,” “Down By the Riverside,” “Medgar Evers Blues” and “Pie Blues,” while the foursome addresses “Up Jumped Spring,” “The Very Thought of You,” “I Want to Talk About You” and “Don Is.” DeFrancesco and Whitfield sparkle throughout this nicely paced outing. This is an album that should receive a lot of airplay and find itself frequently in your player. mackavenue.com

» This pandemic and the associated lockdown has had a particularly hard effect on jazz musicians. With clubs closed, concerts canceled and on hold, and getting together in a studio for

24 SEP / OCT • 2020 JERSEY JAZZ

recording pretty much precluded by social distancing requirements, they have been left to their imaginative devices to survive until things turn around. Many have been livestreaming with the hope that it will result in viewers making online contributions to support their efforts. A few have returned to busking where it is allowed and safe to do so.