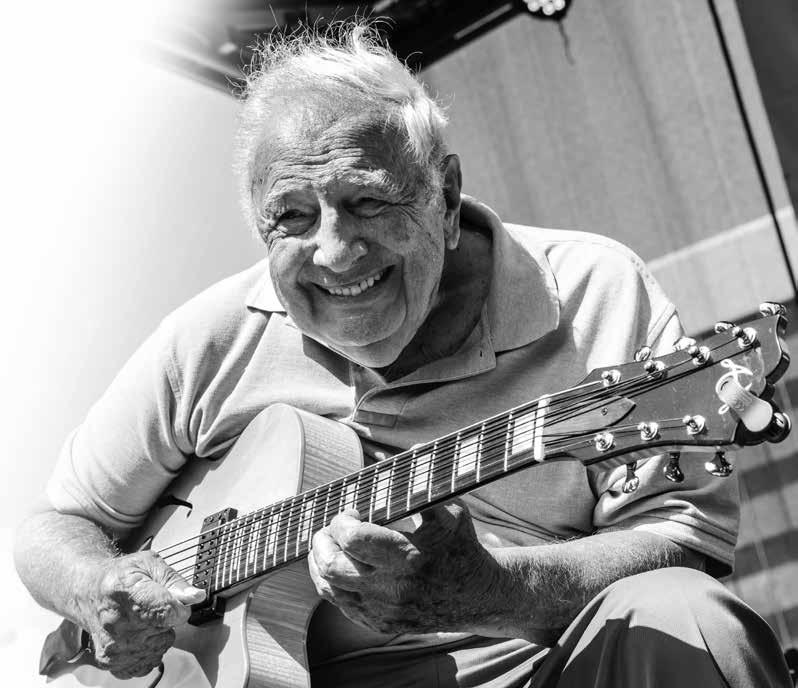

January 9, 1926 - April 1, 2020

May / June 2020 Volume 48 Issue 3 www.njjs.or g Magazine of the New Jersey Jazz Society

Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz.

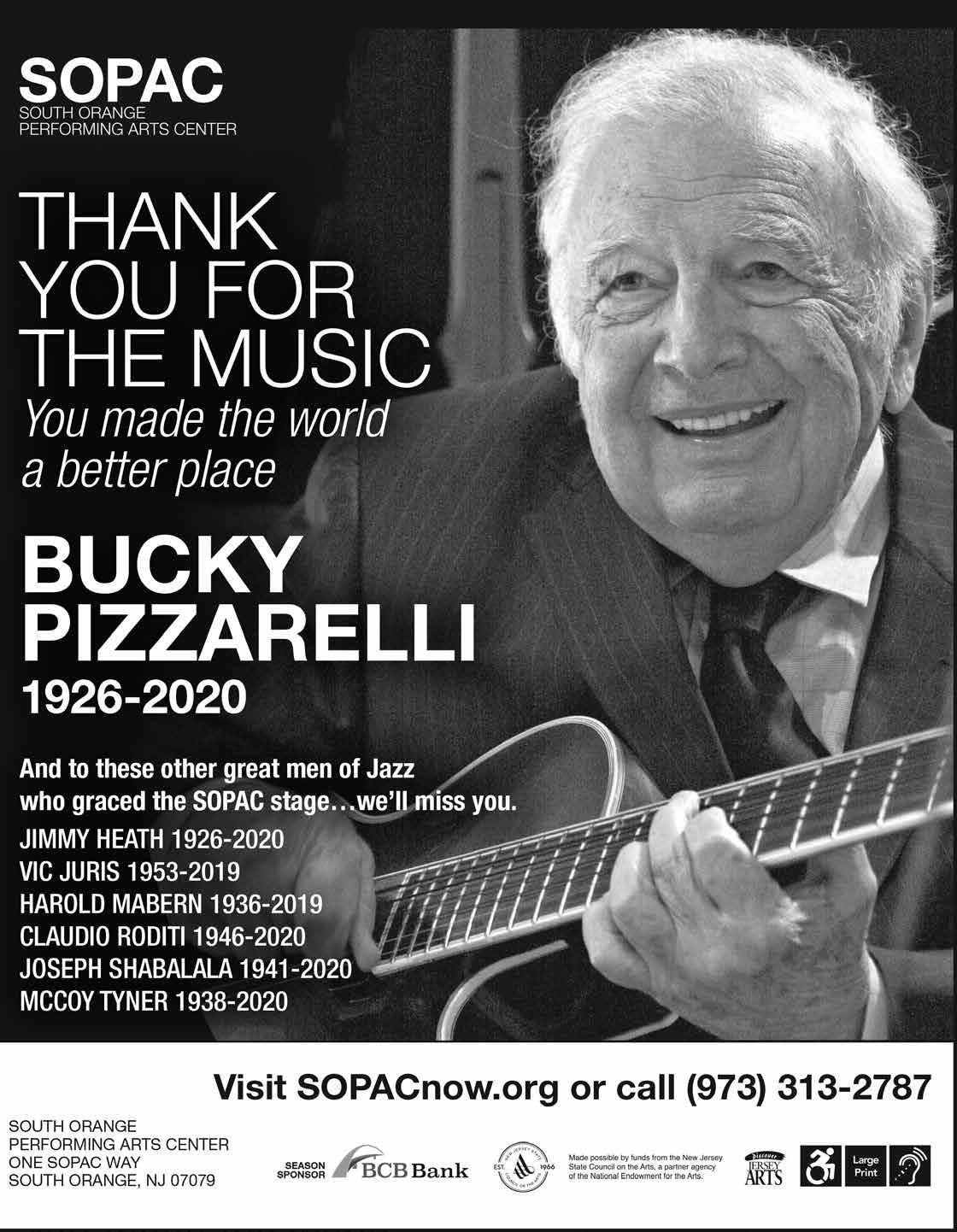

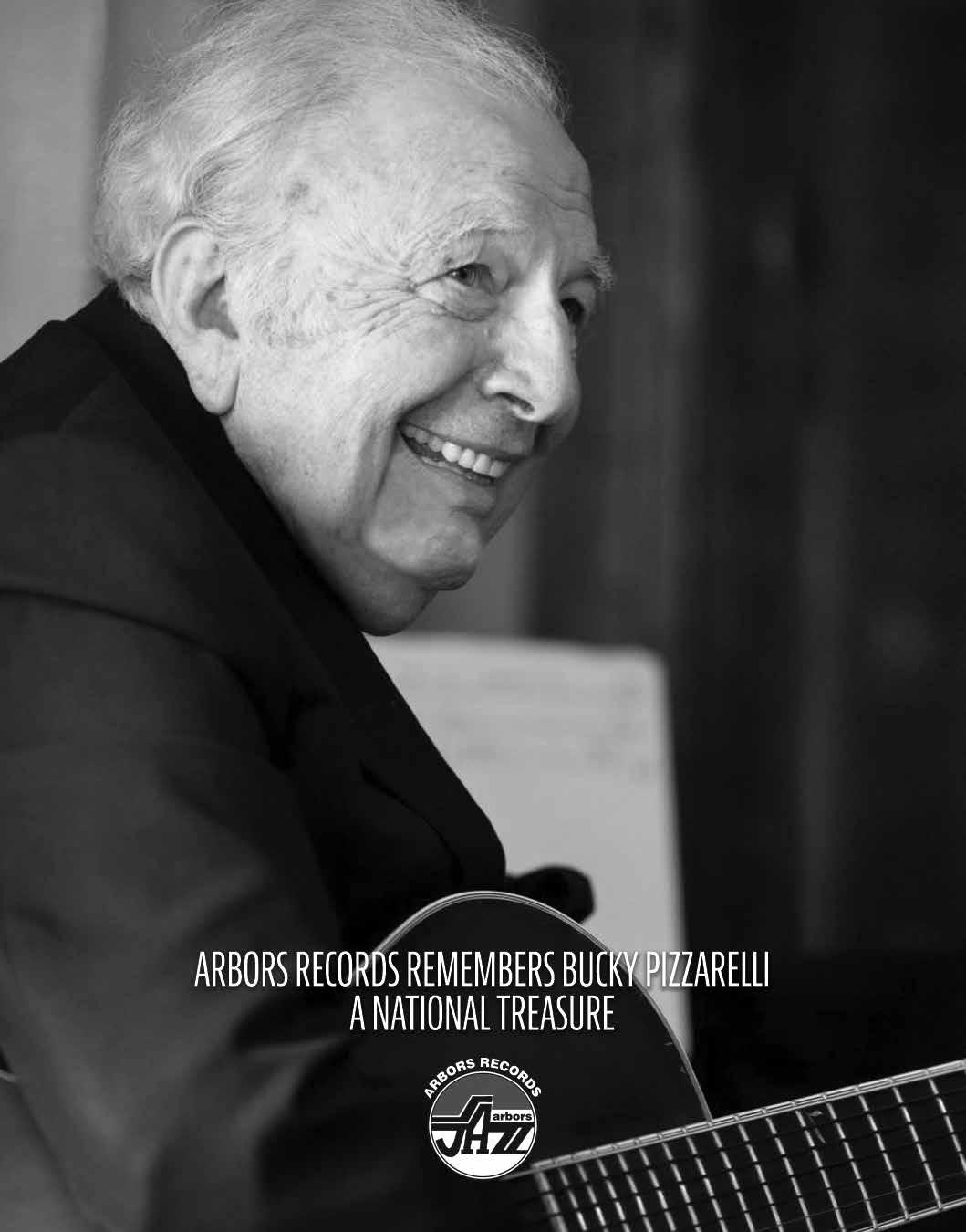

Bucky Pizzarelli

By Cydney Halpin President, NJJS

By Cydney Halpin President, NJJS

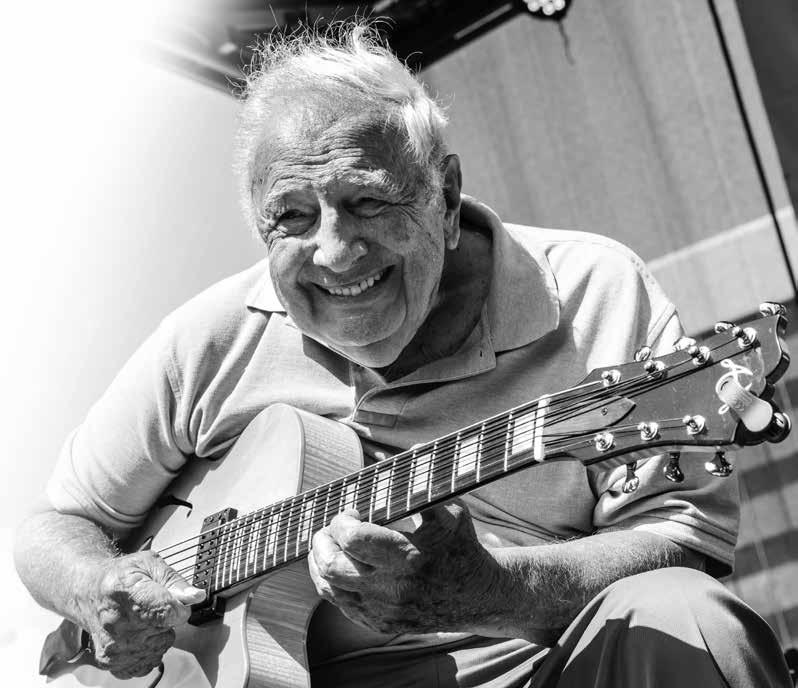

I hope this issue of Jersey Jazz - whose cover is graced one last time by the incomparable Bucky Pizzarelli - finds you and your loved ones safe and healthy, socially distant yet connected to the people and things that bring you solace and joy.

The impact of this global Covid -19 pandemic physically, emotionally, spiritually and financially will have spared no one “When the Lights Go On Again (All Over the World).” The refrain of this song, written in1943 and made popular by Vaughn Monroe, keeps going through my head during these dark and unprecedented times. Every aspect of the jazz world has been upended, with this crisis laying bare how interdependent each piece of this puzzle is and how fragile the web of security is for our musicians, club owners, restaurants, waitstaff, restaurant suppliers, vendors, venues/theaters, advertisers, promoters, managers, publications, publicists, drivers, parking attendants, hotels and their staff - the list is infinite!

Musicians and venues/restaurants need your help NOW! Here are some recommendations for immediate support:

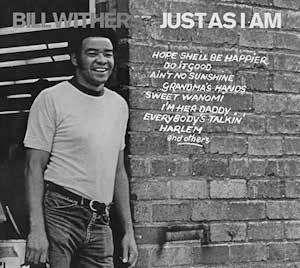

• Purchase artist CDs and downloads from their websites or other online sources like Amazon, Bandcamp and iTunes.

• Purchase gift certificates to clubs and restaurants for future personal use or gifts.

• Purchase take-out meals for yourself, for others, for first responders. Shanghai Jazz is offering this service.

• Make a financial donation to reputable organizations directly helping our musicians like Jazz Foundation of America, the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation and The Grammy’s /MusiCares. There is a comprehensive state by state resource guide on www.billboard.com for other vetted entities.

• Make a financial donation to any organization, museum, entity that supports jazz.

The lights will go on again one day and our fragile jazz world will need your continued patronage and support more than ever. I look forward to seeing you at an NJJS Social, an NJJS sponsored event, at Shanghai Jazz, at a New Brunswick Jazz Project offering, at any of the clubs/venues in NYC, anywhere where jazz music will be celebrated. Until then, please remain vigilant about your health and the health of others. Stay safe and well and WASH YOUR HANDS!

To the Pizzarelli Family, the New Jersey Jazz Society shares in your sadness with the profound loss of your parents Bucky and Ruth Pizzarelli. Their participation and support in the jazz world will be greatly missed. Bucky was our patron saint, and the source of great pride and much musical joy for decades to our board, members and friends. Peace and strength to you all during this difficult time.

To those who have fallen ill with this horrific virus, my fellow board members and I wish you a full and speedy recovery and to those who have lost loved ones to it, we offer our most sincere condolences.

“Music can heal the wounds which medicine cannot touch” – Debasish Mridha ALL

This issue is sponsored in generous part by Tony Freeman.

2 May / June 2020 COLUMNS All That’s Jazz! ............................... 2 Editor’s Choice .............................. 4 Dan’s Den ..................................... 14 Jazz Trivia ..................................... 18 Not Without You! ....................... 33 Noteworthy .................................. 34 From the Crow’s Nest ................. 36

Big Band in the Sky ....................... 5 Jazz Giant: Charles McPherson .. 10 Sarasota Honors Rachel Domber.. 12 Other Views ................................. 16 The Bright Future of Jazz. ........... 20 Talking Jazz: Ingrid Jensen ......... 22 Marty Grosz’s ‘Life in Jazz’. ........ 38 On the Cover:

by Christopher Drukker

ARTICLES/REVIEWS

Bucky Pizzarelli photo

- - -

THAT’S JAZZ!

Bright Future of Jazz

20-21

YOU TO OUR ADVERTISERS:

IN THIS ISSUE The

Pages

THANK

Amani, Arbors Records, Bell & Shivas, James Pansulla, Jazzdagen Tours, Metuchen Arts Council, Morristown Jazz & Blues Festival, Ocean County College, Sandy Sasso, Shanghai Jazz, SOPAC, WBGO

I met Bucky Pizzarelli in the Spring of 1997- facilitating an interview with him and his sons John and Martin - outside the Royale Theater (now the Schoenfeld) on West 54th Street, after a matinee of the short-lived musical Dream (read John’s memoir “World on a String” if you missed it!). I was friends with “the boys” (the name my mother always affectionately called them) and had greeted them both with hugs. Then I turned, looked “the legend” in the eyes and put out my hand to introduced myself, “Hello Mr. Pizzarelli, my name is Cydney. It’s a pleasure to meet you.” And it happened, my first experience with that smile, the twinkle in those eyes, and the laugh. With a returned handshake with both his hands clasping mine, he chuckled and said, “It’s Bucky. Just Bucky.” That, as they say, was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

For the last several years of his career, I was blessed to be Bucky’s gig buddy, dinner companion, wing-girl, a steadying arm and occasional guest singer, while my partner Bob Rizzo assumed the roles of chauffeur (complete with hat!), roadie and backup wingman. Together with Martin on bass and Ed Laub on guitar, and a host of other incredible musicians, we all kept Bucky doing the ‘only thing I know how to do.’ And do it he didfor over 70 years!!

Being a part of these latter years’ gigs meant we were at the Pizzarelli home often for pickups. Bucky’s wife Ruth, a woman of great style and zest for life, (don’t think the men in the family are the only ones who could tell a good story!) would greet us at the door and turn our simple visit into a celebration! Upon leaving she’d wave us off as if we were embarking on a world cruise and, as family meant everything to her, she’d often be waiting up when we delivered her beloved Bucky and Martin back home safely.

On April 1, 2020, the Covid-19 virus claimed Bucky’s life. On April 8, 2020, Ruthie, after 66 years of marriage, four children, four grandchildren, all the music, all the adventures and all the stories, made it clear she had no intention of living without him. John wrote on Facebook, “I’m certain Bucky called for her.” Indeed, I can hear Bucky’s voice (the boys and Bob do great impersonations!) calling, “Ruuuuth” and Ruthie’s quick reply, “Buck?”

They’re stompin’ together at the Savoy, Bucky on the bandstand, and Ruthie at a table with the best view, right where she belongs, elegant and fun - his honeysuckle rose.

Bucky and Ruthie, It has been the greatest gift to share our lives with you and your family. We will miss you both so much!

With all our love, Cydney & Bob

Jay Dougherty Executive VP email: vicepresident@njjs.org

Dave Dilzell Treasurer email: treasurer@njjs.org

Pete Grice VP, Membership email: membership@njjs.org

Sanford Josephson VP, Publicity email: sanford.josephson@gmail.com

Mitchell Seidel VP,

Mike

Ted

ADVISORS

Don Braden, Al Kuehn, Bob Porter, Holli Ross www.njjs.org

May / June 2020 3 Magazine of the New Jersey Jazz Society Volume 48 • Issue 3 USPS® PE6668 Jersey Jazz (ISSN 07405928) is published bi-monthly for members of The New Jersey Jazz Society P.O. Box 223 Garwood, NJ 07027 908-380-2847 info@njjs.org Membership fee is $45/year. Periodical postage paid at West Caldwell, NJ. Postmaster please send address changes to P.O. Box 223 Garwood, NJ 07027 All material in Jersey Jazz, except where another copyright holder is explicitly acknowledged, is copyright ©New Jersey Jazz Society 2020 All rights reserved. Use of this material is strictly prohibited without the written consent of the NJJS. Sanford Josephson Editor email: editor@njjs.org Steve Kirchuk Art Director email: art@njjs.org Fradley Garner International Editor email: fradleygarner@gmail.com Mitchell Seidel Contributing Photo Editor email: photo@njjs.org Contributing Editors Dan Morgenstern, Bill Crow, Schaen Fox, Sandy Ingham, Joe Lang Contributing Photographers Christopher Drukker, Bob Schultz, Mitchell Seidel NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY OFFICERS 2020

Cydney Halpin President email: pres@njjs.org

Music Programming music@njjs.org

Irene Miller Recording Secretary

Jack Stine Co-Founder

DIRECTORS

Katz Immediate Past President

Clark, Cynthia Feketie, Stephen Fuller, Carrie Jackson, Mike Katz , Peter Lin, Caryl Anne McBride, Robert McGee, James Pansulla, Stew Schiffer, Marcia Steinberg, Elliott Tyson, Jackie Wetcher

Printed by: Bernardsville Print Center

Bucky Pizzarelli: Storyteller and Mentor

By Sanford Josephson

The first time I interviewed Bucky Pizzarelli was in the fall of 1978 for an article I was writing about Joe Venuti for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. Venuti died in August of that year, and I was gathering comments from his musical peers. At the time, Bucky was leading a trio at the Pierre Hotel’s Cafe Pierre with pianist Tony Monte and bassist Ron Naspo.

No one really knew Venuti’s age because there were so many versions of when and where he was born. Bucky thought 80 was the correct age, but he told me Venuti kept everyone guessing. “Sometimes, he’d give you a phony figure, then he’d give you another figure.”

Then, Bucky shared two favorite Venuti stories. The first one was at Michael’s Pub, a New York club where Venuti appeared regularly. “One night,” Bucky said, “Joe had a lot of his relatives over from Italy, and they were all sitting around the table. The comedian Henny Youngman came over and started to tell a few jokes. Nobody laughed because nobody understood him. It was a typical Joe Venuti situation. After Youngman told three or four jokes, he looked up at Joe and said, ‘Does anybody speak English here?’, and Joe nonchalantly answered, ‘No.’ ”

The other story was about Teddy Wilson, at Dick Gibson’s Jazz Party, an annual jam session held in Colorado Springs. Bucky said, “Teddy Wilson was sitting around late one night. We were all sitting in the room there. Teddy asked Joe to play some melody that he had heard him do once before. Joe played about eight measures, and Teddy dozed off. So, Joe quietly went to bed, and the next morning when he woke up, Teddy was still sitting in the seat sleeping. So, Joe took his violin out and played the end of the song as Teddy woke up.”

Thirty years later, I was updating the Joe Venuti article for my book, Jazz Notes: Interviews Across the Generations (Praeger/ABC-Clio: 2009) by interviewing some young violinists who were influenced by him. One was Aaron Weinstein, whose touching and humorous tribute to Bucky appears on page 6. Weinstein and Bucky were appearing together at Morristown’s Bickford Theater. “I love how Bucky plays,” Weinstein told me, “but I also love playing with him. He’s a guitar player, and I’m a violin player, but I can learn so much from him because Bucky is one of the great masters of this music, and I value my time with him.”

Earlier that day, Weinstein recorded a new CD with Bucky for Arbors Records. “It’s just beautiful music,” Weinstein said. “It’s that mentality of respecting the melody. It’s Bucky, bassist Jerry Bruno, and I’m with a string quartet -- two violinists, a cellist, and a viola.” The album, So Hard to Forget, was released early in 2009.

On a January night in 2008, Bucky was leading a trio at Centenary College in Hackettstown. The other trio members were pianist John Bunch and bassist Phil Flanigan, but there was a special guest -12-year-old violinist Jonathan Russell. The highlight of the concert was a moment when Bunch and Flanigan left the stage and 12-year-old Russell and 82-year Pizzarelli collaborated on a hauntingly uplifting version of Johnny Green’s “Body and Soul”. Later, when I interviewed Russell, he described the moment with Bucky as “pretty cool.”

R.I.P., Bucky. We will all miss you.

About NJJS

Founded in 1972, The New Jersey Jazz Society has diligently maintained its mission to promote and preserve America’s great art form – jazz.

To accomplish our mission, we produce a bi-monthly magazine, Jersey Jazz; sponsor live jazz events; and provide scholarships to New Jersey college students studying jazz. Through our outreach program Generations of Jazz, we provide interactive programs focused on the history of jazz

The Society is run by a board of directors who meet monthly to conduct Society business. NJJS membership is comprised of jazz devotees from all parts of the state, the country and the world. Visit www.njjs.org or email info@njjs.org for more information on our programs and services.

MEMBER BENEFITS

10 FREE Concerts Annually at our “Sunday Socials”

Bi-Monthly Award Winning Jersey Jazz Magazine - Featuring Articles, Interviews, Reviews, Events and More.

Discounts at NJJS Sponsored Concerts & Events.

Discounts at Participating Venues and Restaurants

Support for Our Scholarship and Generations of Jazz Programs

Musician Members

FREE Listing on NJJS.org “Musicians List” with Individual Website

Link

FREE Gig Advertising in our Bi-monthly eBlast

The Record Bin

A collection of CDs & LPs available at reduced prices at most NJJS concerts and events and through mail order www.njjs.org/ Store

JOIN NJJS

Family/Individual $45 (Family includes to 2 Adults and 2 children under 18 years of age)

Family/Individual 3-Year $115

Musician Member $45 / 3-Year $90 (one time only, renewal at standard basic membership level.)

Youth $15 - For people under 21 years of age. Date of Birth Required.

Give-A-Gift $25 - Members in good standing may purchase unlimited gift memberships. Applies to New Memberships only.

Fan $100

Jazzer $250

Sideman $500

Bandleader $750

Corporate Membership $1000

Members at Jazzer level and above and Corporate Membership receive special benefits. Please contact Membership@njjs.org for details.

The New Jersey Jazz Society is qualified as a tax exempt cultural organization under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, Federal ID 23-7229339. Your contribution is tax-deductible to the full extent allowed by law.

For more Information or to join, visit www.njjs.org

4 May / June 2020

CHOICE

EDITOR’S

‘There Is Only One Bucky’

Bucky Pizzarelli 1926-2020

By Sanford Josephson

In 1969, Oscar Peterson released an album called Motions and Emotions on the MPS Records label. One of the tracks was the Antonio Carlos Jobim tune, “Wave”, and the writer Gene Lees sought to find out who the guitarist was.

He reported on his search in the July 1, 1999, issue of JazzTimes. “The chart is marvelous,” he wrote, “and so is Oscar’s performance. But I was particularly struck by the rhythm section guitar work. I listened, trying to figure out who the player was and concluded that it had to be Brazilian, such was the authenticity of it. Not many Americans at that time could really play that way. Later I said to [the arranger] Claus Ogerman, ‘Who played guitar on that track?’ ‘Bucky’, Claus said. It was unnecessary to add a surname: There is only one Bucky.”

Bucky Pizzarelli died at his home in Upper Saddle River, NJ, April 1, 2020, at the age of 94. Two days earlier, according to his daughter, Mary Pizzarelli, he had tested positive for the coronavirus.

After suffering a stroke, pneumonia, and several hospitalizations in 2015 and 2016, it appeared that Pizzarelli’s career was over. But he made a triumphant comeback in 2017. The Chicago Tribune’s Howard Reich, reviewing his June 2017 performance at the Jazz Showcase, wrote of Pizzarelli’s “disarmingly straightforward approach to melodic line. Even at his exalted age, Pizzarelli brought considerable craft to his solos, dispatching practically every note with heightened care.”

In October 2017, the New Jersey Jazz Society saluted Pizzarelli’s seven-decade career at NJJS’ 45th anniversary concert. As reported in the December 2017 issue of Jersey Jazz, the concert kicked off “with a silky smooth ‘Stompin’ at the Savoy’ with Bucky in the leader’s chair . . . The man of the hour, Bucky Pizzarelli, was resplendent in his trademark blazer and rep tie, flashing that ever ready smile, guitar in hand.” Pizzarelli was a favorite among NJJS members and fans, having played countless Jazz Society events going back to the 1970s.

Born in Paterson, NJ, on January 9, 1926, Pizzarelli learned to play banjo and guitar at an early age and, at age 17, was on the road with vocalist Vaughn Monroe’s band. His first musical hero was a blind accordionist/organist named Joe Mooney whom he would play with in Paterson. In an interview with Jersey Jazz’s Schaen Fox 12 years ago (Jersey Jazz, January 2008), Pizzarelli said he learned about the potential Vaughn Monroe gig because of his relationship with Mooney.

“On Sunday afternoons in Paterson,” he said, “we were allowed to go to the Hollywood Brick Bar downstairs on Market and Main Street. Joe Mooney was there, and one of my uncles was playing

guitar with him . . . Frank Ryerson, who was first trumpet player with Vaughn Monroe, was looking for a guitar player to join the band. So, he said to me, are you the kid who played with Joe Mooney down in Paterson?’ I said, ‘Yeah’. He said, ‘OK,’ and that was the requirement. I jumped on the bus and went to Scranton, PA, and Vaughn asked me to stay with the band ‘til I went into the Army, which was about four months later.”

After being released from the Army in 1946, Pizzarelli reunited with Monroe before leaving to join the NBC staff orchestra. He also played with the Three Suns, free-lanced, and toured with Benny Goodman. Pizzarelli was one of the few musicians able to maintain a positive rapport with the difficult Goodman over several years. Asked about that by Fox, he explained that, “Benny could pick a wise guy out before he even walked into the room . . . If you tried to outsmart him, you couldn’t do it . . . I knew what he wanted: With Benny, you had to know what tempo he was doing. That’s all. When he played by himself, there was the tempo before you started playing. If you interpreted that the wrong way, you were out.”

Pizzarelli switched from a six-string to a seven-string guitar when he started playing with fellow guitarist George Barnes in 1970 after Barnes’ previous partner, Carl Kress, died. “I was lucky to team up with George Barnes when I first got that seven-string Gretsch,” Pizzarelli told JazzTimes’ Lees.

“That’s how I got to learn to play that thing.” Reviewing one of Pizzarelli’s and Barnes’ first performances together, The New York Times’ John S. Wilson called them “a brilliant and unique team. Mr. Barnes and Mr. Pizzarelli can be dazzling, and they can be

continued on page 6

May / June 2020 5

THE

BIG BAND IN

SKY

Photo by Bob Schultz

BIG BAND IN THE SKY

continued from page 5

sensuously brooding. They sparkle with excitement, leap with joy, or relax with a warm romantic glow.”

After breaking up with Barnes in 1972, Pizzarelli embarked on a busy recording and performing career, playing solo and appearing with saxophonists Bud Freeman and Zoot Sims and violinists Stephane Grappelli and Joe Venuti, among others.

He played at the White House three times -- for Presidents Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton. The Reagan performance was with Benny Goodman’s quintet which also included Hank Jones on piano, Milt Hinton on bass, and Buddy Rich on drums. “Buddy” Pizzarelli told Fox, “respected Benny like you can’t believe, and when Benny called him to come and play, he was excited and dropped everything. We went down to Washington and stayed at the Watergate. When we played, he even played ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ the way Gene Krupa did it. I have a tape of that. It is very exciting.”

Zoot Sims, Pizzarelli said, was Clinton’s favorite sax player. He was also Pizzarelli’s. “To me,” he told Fox, “there was nobody like Zoot. He was the happiest guy whenever he had that saxophone. Nobody could beat him. He and Al Cohn together, they were the champs. Two champs.” In 1998, Pizzarelli and tenor saxophonist Scott Hamilton released a duo album on the Concord Jazz label called Red Door, a tribute to Sims. Calling the album, “a very successful outing,” AllMusic’s Scott Yanow wrote that, “Pizzarelli’s mastery of the seven-string guitar allows him to play bass lines behind solos, so one never misses the other instruments . .

positive spirit. He seemed to enjoy life to the fullest and made every occasion you were with him -- whether on the road, at a restaurant, hanging with the guys -- a memorable experience. I always looked forward to being with him and his whole family. Also, he was very calm under pressure.” (See article about Rachel Domber receiving the Sarasota Jazz Club’s Satchmo Award, page 12).

“Jazz guitar wouldn’t be what it is today without Bucky Pizzarelli,” guitarist Frank Vignola told the Daily Record’s Westhoven. “He and Freddie Greene were responsible for a style of rhythm guitar playing that has lasted until 2020.” Vignola was often Pizzarelli’s partner in multi-guitar summits at the annual Morristown Jazz and Blues festivals held in August. “He was an inspiration on so many levels,” Vignola said. “When I first met him, I had four young kids, and he was a father. He showed me that, yes, you can be a jazz guitar player and raise a family. That may not seem like a big deal, but it was huge to me.”

. Both Hamilton and Pizzarelli sound inspired in this format, stretching themselves while always swinging.”

In 1980, Pizzarelli began performing in duos with his son, John, then 20, who has gone onto a very successful career as a guitarist and vocalist. The day after Bucky Pizzarelli’s death, John Pizzarelli described his father to the Morristown Daily Record’s William Westhoven as “the ultimate sideman. He wasn’t looking to be the guy out in front of the band. He was happy to be inside the band, supporting the whole organization. There will be some kind of tribute,” he added, “as soon as we can all get with six feet of each other.”

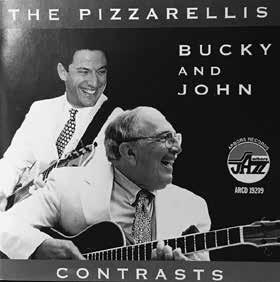

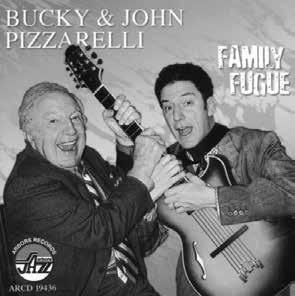

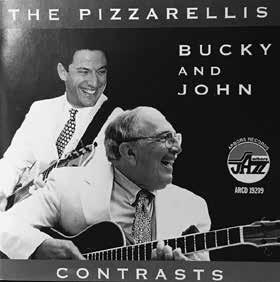

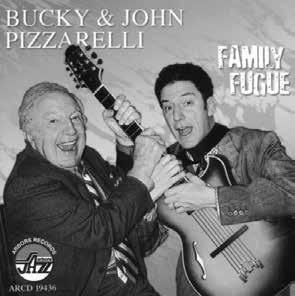

Bucky and John Pizzarelli have recorded albums together on the Arbors Records label, including The Pizzarellis, Bucky and John: Contrast and Bucky and John Pizzarelli: Family Fugue. Arbors Records’ Rachel Domber recalled to Jersey Jazz that her late husband, Mat, and she became friends with Bucky during the 1990s. “Of course, we had heard of him before that,” she said. “He was a very warm, kind person, and I particularly loved his humor and

Ed Laub, Pizzarelli’s protege and musical partner in recent years, recalled on Facebook his first lesson with his mentor. “When I was 16 years old (1968), I rode my bike to the home of Bucky Pizzarelli to take my first guitar lesson. It was a Saturday morning and a day I have never forgotten . . . He said to me, ‘The most important thing you can do as a musician is to try and make everyone you’re playing with sound as good as they can sound...it’s not about you! That’s how you make good music!’ Every musician that ever had the honor of playing with Bucky could sense that was what he did for them every time they played. It was never about him . . . I could never repay Bucky for what he has given me in my life . . . I will be forever grateful. I miss you my dear friend.”

To pianist Dick Hyman, Pizzarelli was “a marvelous guy to work with. He had perfect time, and he knew exactly how the rhythm section and the individual song were best served. I’ll miss him personally; he was one of the founding members of the gang.” Tenor saxophonist Houston Person met Pizzarelli in the early 1970s. “He was such an easygoing guy,” Person said, “and he and he became one of my role models, although I told him I couldn’t dress like him! He always told me I should just play what I felt. It makes no difference, he said, what genre you’re in. We played with the beboppers and the swingers. We all loved Bucky!”

In a Facebook video, violinist Aaron Weinstein recalled the first time he performed with Pizzarelli. “I realized,” he said, “I was sharing the stage with a guy who had played ‘I Got Rhythm’ three times longer than I’d been alive. He did everything but play my violin to help me through that concert . . . Over 15 years, I’ve had the privilege of working on a regular basis with Bucky. During every concert, every recording session, he showed me what it meant to be a great jazz musician. For Bucky Pizzarelli, it meant doing your best

6 May / June 2020

Bucky, with Bernard Purdie Photo by Mitchell Seidel

to make great music, no matter what the venue, sharing that music with the audience in a way they could appreciate and . . . always wearing a tie while doing it.”

Pianist Rossano Sportiello, like Weinstein, learned a lot from Pizzarelli, describing him as “a wonderful musician and person, very supportive of younger players. He was always in a good mood and very generous to give sincere advice. I’ll miss him very much.”

To guitarist Charlie Apicella, “Bucky Pizzarelli embodied the class, warmth, and complete musicianship that is sometimes a rare thing to witness today. My favorite of his recordings are his solo unaccompanied guitar album, Love Songs from1981 and his rhythm playing on Tony Mottola’s All The Way from 1983.”

Bucky’s wife Ruth tragically followed him in death on April 8th, one week to the day after his own. Born December 1, 1930, Ruth was, according to John, “a Jersey Girl before the term was fashionable.” Raised in Waldwick, NJ, no one cared more about family than Ruth. Known to her children as Mommy, and Ruthie by family and friends, Mrs. Pizzarelli was a woman of great style, who loved music, loved a great party, was a fabulous cook, was a kind and generous friend, and never met a stranger she didn’t know. She and Bucky met in 1952, where she worked as a nurse at St. Joseph’s Hospital with Bucky’s sister. Married two years later, the Pizzarellis celebrated their 66th wedding anniversary January 9, 2020. In addition to John and Mary, the Pizzarellis are survived by son, bassist Martin Pizzarelli; daughter Anne Hymes; and four grandchilden.

Donations can be made in their honor to the Jazz Foundation of America.

Ellis Marsalis -- ‘Giant Musician And Teacher, But an Even Greater Father’

“All I did was make sure they had the best so they could be the best. They did the rest.” That brief statement, in a 1993 Ebony Magazine interview, was pianist/educator Ellis Marsalis’ assessment of his

influence on the success of his jazz musician sons -- saxophonist Branford, trumpeter Wynton, trombonist Delfeayo, and percussionist Jason. The elder Marsalis was practically a household name in New Orleans for years, but he only became nationally known when his sons, Branford and Wynton, rose to prominence in the 1980s.

Marsalis died on Wednesday, April 1, 2020, in New Orleans at the age of 85. The cause, according to Branford, was complications of COVID-19. “My dad, was a giant of a musician and teacher, but an even greater father,” said Branford, in a statement issued after his father’s death. “He poured everything he had into making us the best of what we could be.”

Wynton, in his blog on wyntonmarsalis.org, called his father “a humble man with a lyrical sound that captured the spirit of place -New Orleans, the Crescent City, the Big Easy, the Curve. He was a stone-cold believer without extravagant tastes. Like many parents, he sacrificed for us and made so much possible. Not only material things, but things of substance and beauty like the ability to hear complicated music and to read books; to see and to contemplate art . . . For me, there is no sorrow, only joy. He went on down the Good Kings Highway, as was his way, a jazz man, ‘with grace and gratitude.’”

Ellis Marsalis was born on November 14, 1934, in New Orleans. He began as a saxophonist before changing to piano in high school. He received a Bachelor’s Degree in Music Education from New Orleans’ Dillard University, later earning a Master’s Degree in Music Education from Loyola University, also in New Orleans. He directed the Jazz Studies program at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts for high school students. Among his students were trumpeter Terence Blanchard and pianist/vocalist Harry Connick, Jr. He later taught at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond and the University of New Orleans where he founded its Jazz Studies program.

While teaching, he continued to work as a musician, often performing with visiting musicians who were playing in New Orleans and, for three years, from 1967-70, touring with New Orleans-based trumpeter Al Hirt. In 1979, he played a gig at New York’s Carnegie Tavern and was praised by John S. Wilson of The New York Times. “Unlike the widely accepted image of jazz musicians from New Orleans,” Wilson wrote, “Mr. Marsalis is not a traditionalist . . . he’s an eclectic performer with a light and graceful touch . . .an exploratory turn of mind.”

A year later, his two older sons, Branford and Wynton, began to rise on the national scene, and their father’s profile rose with them. In 1983, he gave a solo performance at the Carnegie Tavern’s next door neighbor, Carnegie Hall. “Mr. Marsalis’ interpretations were impressive in their economy and steadiness,” wrote The New York Times critic Stephen Holden. “Sticking mainly to the middle register of the keyboard, the pianist offered richly harmonized arrangements in which fancy keyboard work was kept to a minimum, and studious melodic invention, rather than pronounced bass patterns, determined the structures and tempos.”

Marsalis also collaborated on albums with his sons -- Standard Time, Vol. 3: The Resolution of Romance (Columbia: 1990) and Joe

continued on page 26

May / June 2020 7

Photo Credit: Louisianaweekly.com

Three Jazz Lovers Had a Dream: 10 Years Later, It’s Reality

By Sanford Josephson

Due to the coronavirus, the New Brunswick Jazz Project canceled all performances beginning in mid-March. Please check nbjp.org for updates.

Ten years ago, New Brunswick residents Virginia DeBerry, Jimmy Lenihan, and Michael Tublin decided they wanted to bring live jazz to their town on a regular basis. As luck would have it, all three were steady customers at Makeda, a local Ethiopian restaurant. “We approached Makeda,” said Lenihan, “because we knew the owners, and they knew us.” Added DeBerry, “We had been regulars there for

many years, and they were willing to give us a shot.” Tublin explained that, “At the launch, we said, ‘We’ll take the financial risk. We’ll put the money up at the beginning, and you’ll see the benefit.’”

The biggest challenge at the start was getting the word out, and DeBerry remembers that, “There were nights when it was the three of us, Makeda staff, and the band. But, the music was great, and we knew we would continue. We had agreed to present events for a year -- no matter what. We felt that was the way to give it a chance.”

The first act, booked on Wednesday night, April 14, 2010, was alto saxophonist Ralph Bowen who was also a faculty member in the Jazz Studies program at Rutgers’ Mason Gross School of the Arts. “By the end of the first six months,” recalled DeBerry, “we had gone from twice a month to once a week. The audience was small but enthusiastic, and we felt like it would happen.”

Through the years, NBJP’s venues have featured a wide variety of well-known jazz artists including guitarist Dave Stryker, saxophonists Tia Fuller, Virginia Mayhew and Jerry Weldon, and drummers Victor Lewis and Rudy Royston. Tublin recalled one night when young trombonist Andy Hunter was performing. “All of a sudden, Conrad Herwig comes in and sits in and plays with Andy. We knew Andy was one of his proteges, so it was special.” Added Lenihan: “A bunch of nights we hugged each other because of the interaction of the performers and the audience.”

One promise the NBJP partners have made to their patrons is that there will never be a cover charge or minimum at their venues. That has been accomplished, DeBerry explained, “by working with the venues so they can maximize their return on the additional business jazz nights bring. It’s also working with the audience and encouraging them to eat and drink so the music can keep playing. One of the issues that has happened with jazz, especially in the New York-New Jersey area is that events have often been cost prohibitive.”

Another key to success has been the noise level of the venues. “We ask for respect for the musicians from our audiences,” said Lenihan. “We don’t ask for silence, but we do ask that people listen to the music.” And, echoing DeBerry, he added: “The music is free, but we do expect our audiences to support the house.”

Currently, there is live jazz three nights a week. Tuesday nights feature emerging artists at the George Street Ale House, and Wednesday and Thursday nights are at Tavern on George. “I think the last two to three years is when NBJP really caught on,” DeBerry added, “once we relocated to Tavern on George.”

The group has tried a number of venues, but Tavern on George, according to Lenihan, “came with a basement that looked like a jazz club. It has a certain vibe.” And the owner, Doug Schneider, is committed to making jazz work there. “When we first started there,” said Tublin, “we asked him what dates he wanted to cancel, thinking he would have some private parties around the holidays. He said, ‘We’re not canceling jazz.’”

This writer was at Tavern on George on a Thursday night in late January to see the Nat Adderley, Jr. Quartet. The house was packed, but what was particularly evident was the diversity of the audience -- in race, age, and gender. That, according to DeBerry, is “one of the things I think is the greatest about NBJP jazz nights. I honestly believe we have the most consistently diverse audience of any cultural institution in New Brunswick. We regularly span not only race, age, and gender, but also a wide variety of economic, social and cultural sectors. Our audience proves that music is a connecting force. We have people who have made new friends. We’ve had a number of romantic relationships come from jazz nights. We’ve had marriage proposals and weddings result from our jazz nights. It’s been pretty extraordinary.”

The diversity of the audience, Lenihan added, “reflects our community. It’s the people we hung out with before we started this. They’re the same type of people who are attending our venues. I would also add a shout out to the city of New Brunswick, and the Mayor of New Brunswick, James Cahill. He has been in our corner from the very beginning. He’s the most supportive politician I’ve ever dealt with.” New Brunswick, Tublin pointed out, “is between New York and Philadelphia. It’s fortunate that, geographically, it’s where we all landed.”

8 May / June 2020

NEW BRUNSWICK JAZZ PROJECT

Alto saxophonist Ralph Bowen was the first NBJP performer. Photo by Joel W. Henderson

From left, Jimmy Lenihan, Virginia DeBerry, Michael Tublin

May / June 2020 9

Alto Saxophonist Charles McPherson: A True Giant of Jazz

By Sanford Josephson

I first saw Charles McPherson perform in June 1974 at a Newport Jazz Festival in New York concert entitled, “The Musical Life of Charlie Parker”. A big band led by pianist Jay McShann had a saxophone section with three altos: McPherson, Sonny Stitt, and Phil Woods. Throughout the early and mid-’70s, I would see McPherson and trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer regularly at a club in the Village called Boomers on Bleecker Street. I last saw McPherson play live in December 2015 at William Paterson University and was hoping to see him again at the first Main Stage Concert of this year’s Sarasota Jazz Festival, which was canceled (except for the previous night’s Pub Crawl) due to the coronavirus. McPherson was scheduled to appear on March 12 with NEA Jazz Master pianist Dick Hyman, clarinetist/ saxophonist Ken Peplowski, the festival’s music director, and guitarist Russell Malone. Fortunately, in anticipation of the Sarasota performance, I had interviewed him by phone on March 6.

In 1948, when Charles McPherson was nine years old, his family moved from Joplin, MO, to Detroit. “It was better up north,” he told me. “It was a big city. It was booming. Blue collar, working people were very healthy. Money was flowing. The jazz clubs were successful, and there was a great musical scene.”

McPherson’s family lived on a street that was about a block away from the Blue Bird, “the hippest jazz club in Detroit.” Pianist Barry Harris lived around the corner from the McPhersons, and the future trumpeter, Lonnie Hillyer, lived on the same street. But, before McPherson knew all this, he noticed something special about his neighborhood. “I can remember playing in my front yard,” he said. “I would see throngs of people. Now, I know they were walking to the club, the Blue Bird, but I didn’t know it then. I did know there was something different about these people walking in this direction. They were black and white, interracial. A little kid like me noticed something unusual about that. Something different. A different look coming out of those faces. A certain worldliness. I knew this was a different group of people than those I saw when I went to the grocery store or the post office.”

By the time he reached junior high school, McPherson started playing trumpet, eventually switching to saxophone. An older saxophone player told him about Charlie Parker. “I remembered that name, and I saw Charlie Parker’s name on a jukebox. There were songs like ‘Tico Tico’, ‘Blue Suede Shoes’, ‘In the Still of the Night’. They resonated with me. I said, ‘This is it. This is how you should play.’ There were these long lines that connect like sentences, what I would now call linear -- a bunch of notes being played, and they were all making sense. All these notes fit like a glove. I understood it. Then, I discovered a whole slew of musicians who played like this.” (In 1988, McPherson was the alto saxophone voice of Charlie Parker in several scenes of Clint Eastwood’s movie, Bird)

“Now I understood where these people were going,” he continued. “The club down the street, the Blue Bird, was a place where they played that kind of music. So, I started to go down and stand outside and listen to the music, to people like Elvin Jones, Barry Harris, Thad Jones, Pepper Adams, Paul Chambers. I would just stand outside and listen. One day, the club owner said I could come inside with my parents. At

10 May / June 2020

FROM BEBOP TO BALLET

this time, Miles Davis was playing there. I came in with my parents, and I couldn’t believe it.”

McPherson and his friend, trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer, would occasionally try to sit in at the Blue Bird. “We could play the melody,” McPherson recalled, “but we couldn’t improvise worth a damn. Barry Harris heard us and said, ‘If you want, come by the house, and I’ll show you some things.’ That was the beginning of me learning about harmony and chord changes. I was over at his house every day. He was always teaching. People like Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane -- when they came to Detroit, they would go to his house and hang out. I would be over after school, and I would watch them. They’d be talking about Bertram Russell, Jack Kerouac, the existentialists. They were very intelligent people talking about things that had nothing to do with music. I began to realize that to play this music, you’ve got to become a thinker. You gotta understand how art is connected to other things.”

McPherson moved from Detroit to New York City in the late 1950s and in 1959 he and Hillyer joined Charles Mingus’ band where he would remain for 12 years. “Eric Dolphy and Ted Curson were still in the band,” McPherson recalled, “but they were forming their own groups. Mingus was livid. I got referred to the gig by Yusef Lateef. He knew Lonnie and I were in New York looking for gigs, and he told Mingus, ‘There’s an alto player and trumpet player from Detroit I’ve heard’. Mingus hired us that night.”

Boomers: A Charles McPherson Hangout in the Late ‘60s and Early ‘70s

In an August 2016 article reminiscing about the jazz clubs in Lower Manhattan and Greenwich Village in the 1960s and early ‘70s, Westview News writer Mel Watkins mentioned that “many of the era’s most fondly remembered clubs have been celebrated,” but “Boomers, one of the era’s most colorful and unusual jazz spots, has been overlooked.”

Opened in 1969, Watkins wrote, “the club’s reputation swelled when piano legend Bobby Timmons began appearing regularly . . . and New York Times restaurant critic Raymond Sokolov gave the new soul food menu a rave review. By the early 1970s, Boomers had emerged as one of the most popular jazz clubs and eateries in Greenwich Village.”

The article mentioned Charles McPherson as one of the regular jazz performers along with such other jazz luminaries as pianists Roland Hanna, Cedar Walton, and Junior Mance; saxophonists George Coleman and David Sanborn; and vocalists Betty Carter and Etta Jones. WRVR’s Les Davis broadcast live concerts from there, Watkins wrote, adding that the owners of the Village Vanguard and Village Gate “stopped in to evaluate and recruit artists for their own venues . . . According to saxophonist Dave Schnitter, after [Art] Blakey sat in with him during a session at Boomers, the legendary drummer asked Schnitter to join the Jazz Messengers.” The room was also frequented by “aspiring young politicians as well as celebrities ranging from literary figures to sports stars such as Earl ‘The Pearl’ Monroe or Walt Frazier to members of the Negro Ensemble Company.”

Although McPherson took a short break to work for the Internal Revenue Service, he believes he was the second longest Mingus sideman to drummer Danny Richmond. “I can hear, by way of osmosis, things I remember about Mingus,” he said. “I was always enamored by Mingus’ ballad writing. His ballads were kind of haunting with an interesting, unusual quality.” Every night with Mingus, McPherson said, “was a story. He got a reputation for being a tough guy, but here’s a story that shows another side of him. We played a benefit for the writer, Kenneth Patchen (who had been disabled since the late ‘50s due to a spinal injury). He was a personal friend of Mingus, who did a benefit for him at a coffee house in Mill Valley, CA. It was Danny Richmond, Lonnie, and me. There was a jar for money, and Mingus just gave each of us $5 for playing. Everyone took the money, but I said, ‘Just put it in the tip jar.’ His eyes watered up, and he just said, ‘Thank you, Charles.’ I was 21 years old, and from that point on, he never bothered me. I could be late, it didn’t matter. He teared up, and I could tell he thought of me a little differently. Once he pigeonholed you into a certain category, that’s what you were forever.”

In 1978, McPherson moved to San Diego “to get away from New York and also to see my mom who was living there. She was 69 or 70, and I’m thinking, ‘that’s old as hell’. I ended up staying, and she lived to be 94. I started a new life in San Diego.” He met his wife, Lynn, there, and his youngest daughter, 27-year-old Camile, is a dancer with the San Diego Ballet. She introduced him to choreographer Javier Belasco, and, as a result, in 2015, his large-scale work, “Sweet Synergy Suite” was premiered by the company. It blends bebop and Afro-Latin music with ballet and modern dance styles.

McPherson became the ballet company’s Resident Composer in 2016. “In the last four or five years,” he said, “I have written several ballet suites.” His “Song of Songs”, eight tunes for jazz quintet and voice, was recorded last year at the Rudy Van Gelder Studios in Englewood, NJ, and is due to be released this year. “It was taken from the Old Testament story,” he said. “It deals with a young woman and man in love, a story of unrequited love. The young woman sings some of the words in Hebrew.”

Now 80 years old, McPherson was recently described by The Santa Fe New Mexican’s Richard Sheinin as “an authentic bebopper who keeps his eye on the melody.” That definition, he said, “is true. Any improviser needs a point of reference, other than it sounds good. When you improvise, you don’t just want to ramble. The real art in improvising is when you take a theme and explore it several different ways but make it a cohesive solo with an awareness of the melody. That’s the difference between a player who knows his craft and one who doesn’t. You need to be adhering in some way to the vibe of the melody even though you’re free to play it a million different ways. It’s like playing ping pong. You can’t play without a table. The real art is: Can you hit the ball a million different ways and still go over the net?”

May / June 2020 11

Arbors Records’ Rachel Domber and Her Late Husband, Mat, Receive Prestigious Satchmo Award

The Jazz Club of Sarasota presented its prestigious Satchmo Award to Rachel Domber and her late husband, Mat, founders and operators of Arbors Records, on March 12, at a reception that was part of the pandemic-interrupted Sarasota Jazz Festival. The presentation had been planned as part of the Jazz Club’s 40th anniversary celebration and was hastily rescheduled as musicians and audiences departed under an advisory from Florida governmental officials.

Ed Linehan, President of the Jazz Club and Managing Director of the Jazz Festival, said, “We are very pleased to honor the work of Rachel Domber and her late husband, Matthew, by presenting them with the Satchmo award, the Jazz Club’s highest recognition.” The award commemorates the contributions of jazz great Louis Armstrong. Previous award recipients include NEA Jazz Master pianist Dick Hyman and clarinetist/tenor saxophonist Ken Peplowski, who has been Music Director of the festival the last few years. The 2019 Satchmo Award went to tenor saxophonist Houston Person who was scheduled to perform, along with Hyman and Peplowski, at this year’s event. The award is sponsored by the Harold and Evelyn R. Davis Memorial Foundation in memory of Hal Davis, Founder of the Jazz Club of Sarasota.

Created in 1987, the award, Linehan said, seeks “to honor those who have made a unique and enduring contribution to the living history of jazz, our original art form. I can’t think of anyone who fits that definition better than the Dombers. Through their efforts, Arbors has produced hundreds of albums since 1989, representing many classic styles of jazz.”

Dixieland Jazz Classic in Clearwater, FL; and has been a generous supporter of the New Jersey Jazz Society.

Among Arbors releases in recent years have been Hyman and Peplowski’s Counterpoint, clarinetist/saxophonist Adrian Cunningham’s Adrian Cunningham and His Friends Play the Tunes of Lerner and Loewe, and multi-reedist Scott Robinson’s Tenormore, named Best New Release of 2019 by the readers of JazzTimes Magazine.

Violinist Aaron Weinstein recalled to Jersey Jazz that he met Mat and Rachel Domber “at my first professional recording, which was a session for Arbors Records. At the urging of Bucky Pizzarelli, I was hired to be part of what turned out to be Skitch Henderson’s last album . . . Almost immediately thereafter, Mat and Rachel took me under their wing, bringing me into the Arbors family. They gave me opportunities in my late teens and early 20s to work with the world’s greatest jazz musicians and gave me artistic control of the albums I made for them.” Mat Domber, he added, “was like a grandfather to me . . . Mat and Rachel are a modern day Norman Granz. I feel so grateful to have experienced their musical passion, generosity, and friendship.”

Mat Domber was a New York-based lawyer with real estate interests in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Florida. He was also a jazz fan, record collector, and listener. “We started in 1989 without thinking of establishing a record label,” Rachel Domber recalled, “but only to try to give our friend [clarinetist/saxophonist] Rick Fay something he could sell on the bandstand. It grew into a labor of love, and we now have over 400 recordings in our catalog.” Fay had been a performer at Disney parks in California and Florida but had never recorded as a leader. In addition to making records, Arbors was the originator and producer of March of Jazz weekend jazz parties in Clearwater, FL, which started with bassist Bob Haggart’s 80th birthday in 1994 and continued through 2012, the year of Mat Domber’s death. Arbors is also a sponsor of the Sarasota Jazz Festival and the Suncoast

Among Arbors albums recorded by Weinstein are Handful of Stars (2005) and Blue Too (2008). Reviewing Handful of Stars for AllMusic, Rick Anderson described it as “a startlingly mature and impressively confident debut album from 19-year-old jazz violinist Aaron Weinstein, a young man who plays with a felicitous combination of Stuff Smith’s earthy, powerful attack and Stephane Grappelli’s elegant sophistication.” The ‘stars’ who joined Weinstein on the album included Bucky and John Pizzarelli, Houston Person, Nicki Parrott, and drummer Joe Ascione.

When Mat Domber died in September 2012, several musicians paid tribute to him in the pages of Jersey Jazz (November 2012).

Drummer/vibraphonist Chuck Redd said Domber, “changed my life by allowing me to begin recording as a leader in 2001. He placed no restrictions on my selection of music or on my choice of accompanying musicians.” Pianist Rossano Sportiello recalled that Domber “wasn’t concerned with selling records, just helping musicians whom he liked. That made him truly unique.” And, trumpeter Randy Sandke, who now lives in Sarasota, called Domber “irreplaceable. I never knew anyone else who had so much fun while giving pleasure to others. He was a friend, mentor, and inspiration.”

12 May / June 2020

SARASOTA JAZZ CLUB

Rachel Domber

Rachel Domber Keeps the Music Playing ...

By Schaen Fox

Rachel Domber was interviewed by Jersey Jazz writer Schaen Fox before she knew about the Satchmo Award.

When Mat Domber died in September 2012, it would have been easy for his wife, Rachel, to close down the music company he started more than 30 years ago, but she didn’t. Here’s why.

“Since our first album,” she said, “we became personal friends with all of our musicians. When Mat died, I was terribly upset and wondered what to do with my life because we were so intertwined. . . After he died, I thought about keeping the music alive. I enjoyed it so much I thought I’d just keep doing it. I’m 81, so I don’t know how much longer I can keep going, but I’d like to for as long as I can. “Our goal from the start,” she continued, “was to pick out some upcoming people and give them a CD to sell off the bandstand. Now, I’m recording some very well known artists, like Rossano Sportiello. I think he is one of the greatest living pianists, and I want him to record a masterpiece. Things like that fulfill me.”

Although the music business is moving away from CDs toward digital downloads, Arbors, Domber said, will continue to sell CDs. “We are getting most of our business from digital downloads, so I guess it’s the wave of the future,” she said, “but I’m still going to produce physical CDs and digital downloads. We still sell a lot of CDs because we have people who want to get the physical product, read liner notes and have the whole thing there.”

The March of Jazz weekend jazz parties that the Dombers ran from 1994 to 2012 were legendary. “They were the brainchild of my husband,” she said. “He wanted to have a big jazz party with the best musicians. It cost us a lot of money. We never made a dime off of it, but that wasn’t the point. My husband just thrived on the thing. One year was spectacular. We had Sherrie Maricle and her Diva Jazz Orchestra, and we brought the Tuxedo Big Band of Paul Cheron from Toulouse, France. Bob Wilber was very connected to it. It was exciting to see the all-male band from France and Sherrie’s allfemale American band together.”

It might surprise fans of Arbors Record to learn that Rachel Domber was actually a country music fan when she met Mat. “I was an economist working for the government,” she recalled. “He was a consultant with the State Department in Pennsylvania and made an appointment to see me to discuss low income housing. He was trying to get some elderly units for a non-profit group. I only knew Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, and things like that. When we started dating, I said, ‘I’m sorry, but I can’t imagine going with somebody that doesn’t like country music.’ I loved Tom T. Hall, Bob Wills, and the old-time country music. We started going out to country music things, and he became a huge fan of it.”

As for jazz, “He was 10 years older than me, and he knew everything about jazz. He was a fraternity brother with Dick Hyman at Columbia College. Dick was one year older than Mat, so they weren’t very close, but, after classes, Dick would go down to Greenwich Village and play, and Mat would sneak down to watch him. After we got into the music

business, they became very good friends, and we had a lot of fun together.”

Domber is full of stories about the jazz musicians she and Mat worked with through the years. Ruby Braff and Mat were “very good friends, but Ruby was tough to deal with. One time, he called to talk to Mat, who wasn’t there. He started yelling and screaming about how Mat didn’t know how to do things, so I just slammed the phone down. A few seconds later, the phone rang, and Ruby said, ‘Oh, we must have been disconnected.’ . . . He was nuts, but he was very, very sweet. His soft side came out in his music. He was a master on the cornet.”

Bob Haggart “was wonderful. He enjoyed painting and fancy dining, things like that. Kenny Davern was wonderful in his music, but he had a lot of other interests. He loved hiking and nature. He talked a lot about opera and was well versed in a lot of things. We traveled all over Europe with Bob Wilber and Pug, his wife. They were what I call globalists because of their interests beyond music. I like artists that are not just small talk.”

Tenor saxophonist Flip Phillips gave the Dombers his flattened saxophone. “I have it hanging in my office,” Domber said. “I guess a car ran over it. Flip and Mat were very close.” In addition to the flattened sax, “Mat and I were big collectors of paintings from Bob Haggart and photographs by Milt Hinton.”

All the CDs, Domber said, “are like my little babies. I love them all, and I put a lot of work into every single one . . . The thought of just having lunch with the girls or playing golf, or going to the beach is fine, but I’ve been working ever since I was 16. I love business. That’s why I’m in it. It is mainly for the musicians. I only want to deal with musicians I really admire.”

May / June 2020 13

Ruby Braff was "tough to deal with" but "a master on the cornet."

Pianists Rossano Sportiello, left, and Dick Hyman are two among many Arbors recording artists.

DAN’S DEN

By Dan Morgenstern

Of the far too many who have already been taken from us, the man whose image graces the cover of this magazine was particularly close to the hearts of all who love the music we call jazz, and we were lucky to be his neighbors.

Bucky Pizzarelli was a master of his art and craft. He enhanced any musical situation he might find himself in, and those situations covered a truly amazing range, as you will have learned from “Big Band in the Sky”, to whose ranks he surely was welcomed with open arms and hearts—no musician, no singer who ever shared a note with Bucky could fail to love him.

Bucky Pizzarelli was a master of his art and craft. He enhanced any musical situation he might find himself in.

And that was because he not only could play but loved to play. I would watch when, for instance, he would perform his special arrangement of “Honeysuckle Rose,” calling out the changes to his band mates, spreading joy. Or when he paired with a favorite, such as Ed Laub or Zoot Sims (boy, could they define swing). And you could see it as well as hear it.

I had the good fortune of attending a number of those invitational festivals called “Jazz Parties” where Bucky would also be on hand. He was among the early risers, as was I, and always had a big good morning smile. I never found him in a bad mood—not even when he partnered

with George Barnes for a couple of years, or worked and toured with Benny Goodman for much longer.

There were very, very few musicians as versatile as Bucky Pizzarelli was, and maybe none who were so modest about it.

There were very, very few musicians as versatile as Bucky Pizzarelli was, and maybe none who are or were so modest about it. Bucky had no “side.” He was a warm and gentle man, and a great teacher, formally and informally.

For an informal example, Daryl Sherman told me that when she was making an album for Arbors (whose founder, Mat Domber, was a great Bucky fan), they had finished a run through of one of the songs, and Bucky took her aside and said, “Don’t shoot your wad on the first chorus.” Sage advice! Incidentally, the label is kept alive and well by Mat’s widow Rachel (see stories on pages 12 and 13).

We can be sure Bucky gave plenty of that advice to his son John, who is following in his footsteps with a song in his heart, and to John’s brother, Martin, who plucks a mean bass. I don’t know if sister Mary still plays guitar, but I remember hearing her years ago.

So there’s a living legacy, in addition to the treasure trove of records we can hear Bucky on, not a sour note in the lot. When he was on the scene everything was in tune. We are blessed he was with us for so long!

14 May / June 2020

May / June 2020 15

OTHER VIEWS

By Joe Lang

In these difficult days, music is one of the things that helps take your mind off of the pressures of the day. The steady flow of new albums is at times overwhelming to assess and decide which ones to hip you to this time out. Anyway, here are some tasty choices for you to consider.

Passion Flower: The Music of Billy Strayhorn (Sunnyside – SSC-4114) is an elegant musical examination of 14 Strayhorn gems by pianist JOHN DI MARTINO, assisted by tenor saxophonist Eric Alexander, bassist Boris Kozlov and drummer Lewis Nash. Di Martino has been incorporating Strayhorn material into his repertoire throughout his years as a premier jazz pianist and accompanist. Strayhorn was a melodist supreme, producing a raft of memorable tunes like “Lush Life,” “Chelsea Bridge,” “Daydream,” “Passion Flower,” “Take the ‘A’ Train,” “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing” and “Lotus Blossom,” all of which are included on this album. Alexander is a strong presence with his fluid playing and singular improvisational acumen. It is always a plus to have the kind of steady and swinging rhythmic support provided by Kozlov and Nash. A nice bonus is a knowing reading of “Lush Life” by vocalist Raul Midón. Strayhorn’s music is always a joy to experience, and this collection of his music is among the best to come along. (johndimartino.com)

There was only one ERROLL GARNER. He had a sound and style that was as individual as individual could be. That’s My Kick (Mack Avenue – 1163) and Up in Erroll’s Room (Mack Avenue – 1164) are the latest in the Octave Remastered Series of reissues of classic Garner albums from the 1960s and 1970s. The first of these titles finds Garner in his normal trio setting with congas added. Half of the 12 titles are Garner originals, with the others including standards like “The Shadow of Your Smile,” “Autumn Leaves,” “Blue Moon” and “More.” No matter how familiar the tune may be, Garner makes it a new experience. The other album has the same instrumentation with a brass section added for four tracks. The program has 11 songs, two Garner originals, and nine standards and jazz tunes. The tracks with the brass added are “Watermelon Man,” “The Coffee Song,” “Got a Lot of Livin’ to Do” and “I Got Rhythm. Listening to Garner and his infectious playing has almost a hypnotic effect. He is full of surprises, and you cannot wait to hear how he will resolve what

often seems like a trip to nowheresville. This series has made a lot of valuable listening pleasures once again widely available. (mackavenue.com)

The JEFF HAMILTON TRIO has had many incarnations over the last 30 or so years. On Catch Me If You Can (Capri – 74163) he has a long-time associate, pianist Tamir Hendelman and newcomer bassist Jon Hamar on board. They sound like they have been playing steadily for the entire 30 years. Hamilton is a drummer who is equally at home driving a big band or exhibiting his incredible musicianship and sensitivity in a trio setting. Hendelman has been equally acclaimed as a leader, sideman or accompanist for singers. Hamar is a rock steady timekeeper, and sparkles when given solo space. Together they are three minds working as one. The program is a mix of the familiar, “Make Me Rainbows,” “Bijou” and “Moonray;” some nifty jazz tunes, “Helen’s Song” by George Cables, “Lapinha,” a staple of the Sergio Mendes catalog, “Big Dipper by Thad Jones and “The Pond,” written by one of Hamilton’s mentors, John Von Ohlen; plus two originals by Hamar and one by Hendelman. These gentlemen are given plenty of opportunity to show their versatility, and they shine at any tempo. (www. caprirecords.com)

The swinging twins, PETER AND WILL ANDERSON, keep pouring out marvelous music, whether in concert or in a studio as

on their latest album, Featuring Jimmy Cobb (Outside In Music -2003). For this gathering of the multi-reed playing Andersons with pianist Jeb Patton, bassist David Wong and drummer Jimmy Cobb, they have selected a 10-song program that mixes four pop and jazz standards, “Autumn in New York,” “Someday My Prince Will Come,” “Jeannine” and “Polka Dots and Moonbeams” with three originals by each of the Andersons. The four gentlemen from the younger generation, the Andersons, Patton and Wong, have all developed into front line players, and they are driven by the greatness of the venerable jazz giant one Jimmy Cobb. This is a collection of mainstream jazz at its finest. The strength and versatility of the Andersons as musicians is matched by their talent for composing tunes that immediately catch your ear, and are likely to be picked up by other players. If you need some uplifting, the music presented here is the perfect prescription. (peterandwillanderson. com)

For the title track of his latest recording, Denver-based tenor saxophonist KEITH OXMAN has chosen Two Cigarettes in the Dark (Capri – 74161), a 1934 tune by Lew Pollack and Paul Francis Webster, one not heard very often these days. It illustrates his wide range of familiarity with the Great American Songbook, reinforced by others like “I’ve Never Been in Love Before,” “Everything Happens to Me” and “Crazy He Calls Me.” He is also hip to jazz tunes like Hank Mobley’s “Bossa for Baby” and Johnny Griffin’s “Sweet Sucker.” On these six selections, Oxman is joined on the front line by tenor master Houston Person. The rhythm section, also from the Denver area, is a sparkling one comprising Jeff Jenkins on piano, Ken Walker on bass and Paul Romaine on drums. The quartet minus Person addresses three Oxman originals and one by Jenkins. Annette Murrell provides impressive vocalizing on “Everything Happens to Me” and “Crazy He Calls Me.” Oxman and his cohorts have produced a

continued on page 18

16 May / June 2020

May / June 2020 17

OTHER VIEWS continued from page 16

winner with Two Cigarettes in the Dark. (www.caprirecords.com)

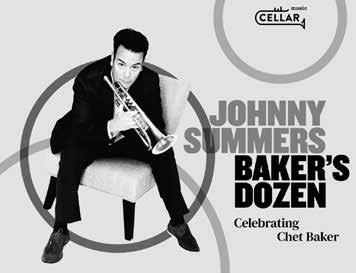

There is a wealth of recorded jazz, which has been lying dormant, that has been discovered and brought out of the shadows to excite jazz enthusiasts. Various labels have been releasing some of these hidden treasures, among them Reel to Reel Records, an undertaking of Cory Weeds, owner of the Cellar Live label. His latest, co-produced by Zev Feldman, who has been involved in several projects for Reel to Reel and Resonance Records, is Ow! Johnny Griffin & Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Live at the Penthouse (Reel to Reel – 003). The two tenor masters were recorded in1962 with a rhythm section of Horace Parlan on piano, Buddy Catlett on bass and Art Taylor on drums at The Penthouse in Seattle for broadcast on a local radio station, KINGFM. The pairing of Griffin and Davis started at Birdland in 1960, but only lasted a few years. This live set is a fine example of the excitement that was generated when these cats met, horns in hand. The eight selections include “Blues Up and Down,”

JAZZ TRIVIA

“Ow!,” “Bahia,” “Blue Lou,” “Second Balcony Jump,” “How Am I to Know,” “Sophisticated Lady” and “Tickle Toe,” bookended by their theme, “Intermission Riff.” The extensive liner notes add to the enjoyment to be derived from this package. (cellarlive.com)

JOHN SNEIDER is probably familiar to most listeners as the trumpet player with vocalist Curtis Stigers. On The Scrapper (Cellar Music – 72619) Sneider proves to be a fine leader and front line player with support from Joel Frahm on tenor sax, Larry Goldings on Hammond B3 organ, John Hart on guitar and Andy Watson on drums. Sneider provides three originals, and Goldings two to a nine-song program that also includes two rarities from Duke Ellington, “Pyramid” and “On a Turquoise Cloud,” the Miles Davis classic, “Solar,” with wordless vocal accompaniment by Andy Bey, and “Dinosaur Eggs,” an original by David Sneider, John Sneider’s son, who also contributes some nifty trumpet work on the track. On the title track, it is immediately clear that this group will provide much excitement. The pairing of Sneider and Frahm with backing from the organ trio works perfectly. Sneider plays

Records that could go viral

By O. Howie Ponder

crisp lines, Frahm is consistently inventive, and the supporting trio provides a rhythmic bed for them to shine. Goldings and Hart are also impressive soloists, while Watson is an unobtrusive but steady presence on the drums. This is Sneider’s first album as a leader in 20 years. Let us hope that there will be another one within a much shorter time frame. (cellarlive.com)

Recently, guitarist Doug MacDonald has released several superb albums. His most recent is Mid Century Modern (dmacmusic -17) by THE COCHELLA VALLEY TRIO, MacDonald on guitar, Larry Holloway on piano and Tim Pleasant on drums. They have frequently played together in Palm Springs, located in the Cochella Valley, and MacDonald feels that this environment helps to create a special vibe that is reflected in their playing. Listening to their efforts on this album, whatever effect the location has, it certainly has resulted in a most appealing recording. There are six standards, “My Shining Hour,” “What’s New,” “Give Me the Simple Life,” “Stranger in Paradise,” “I Hadn’t Anyone Till You” and “The Way You Look Tonight;” a jazz classic, Dizzy Gillespie’s “Woody ‘n You;” and four

continued on page 39

If you’re missing live jazz - who among us isn’t? - during this coronavirus shutdown, here’s a quiz about the 2020 Grammy winners in the five jazz categories that might prompt you to buy a CD or some vinyl or stream the music to help keep the beat going until normalcy returns. (This was written in late March, after a week and a half of isolation mandates in New Jersey and New York.)

1. Nominated for Grammys nine times between 1996 and 2018, the 49-year-old pianist finally won this year’s prize for Best Instrumental Album. His Art of the Trio series, 2002’s Largo, and Love Sublime, a duet set with classical singer Renee Fleming, were among his best-known early-career albums.

2. The bassist and singer was just 25 when she won a Grammy as Best New Artist in 2010. She won twice for a 2012 album (Best Vocal Album, Best Arrangement). Her 2020 winner hit #1 on the Billboard jazz chart. She’s taught at Berklee and is currently on the Harvard faculty.

3. The New York-based trumpeter, now 63, is a longtime member of Eddie Palmieri’s explosive Afro-Caribbean ensembles, and the two shared a Best Latin Jazz Grammy in 2007 for Simpatico. In 2020, the Best Large Ensemble award was all his.

4. The Latin Jazz Grammy winner is a 78-year-old pianist and composer who is as busy as ever, as detailed in a JazzTimes cover story in January. It’s his 25th Grammy, and he’s been nominated for more than 60. His first came in 1976 for the Return to Forever record No Mystery.

5. Best Improvised Solo honors went to a trumpeter who hit the big time in 1967 playing in the jazz-rock band Blood, Sweat and Tears. From 1975-82, he teamed with his tenor saxophonist brother; their band earned seven Grammy nominations for six albums. The brothers also founded the Greenwich Village club Seventh Avenue South.

answers on page 38

18 May / June 2020

May / June 2020 19

RISING STARS

The Bright Future of Jazz

By Sanford Josephson

Three members of the New Jersey Youth Symphony Jazz Orchestra and Charles Mingus Combo won Outstanding Soloist awards at the 12th annual Charles Mingus Festival & High School Competition held February 14-17 at The New School of Jazz and at the Jazz Standard in New York City.

Jersey Jazz recently caught up with all three to talk about their love of jazz and their plans for the future.

Twelve-year-old Ben Collins-Siegel, a student at Maplewood Middle School, started playing piano at the age of four. After taking private lessons for five years from Zev Babbit, his father’s music teacher, Collins-Siegel began participating in Montclair’s Jazz House Kids program, also taking lessons from pianists Oscar Perez, Radam Schwartz, and Bob Himmelberger.

Drummer Koleby Royston, a junior at Piscataway High School, grew up in a musical family. His mother is jazz pianist Shamie Royston; his father is drummer Rudy Royston; and his aunt (Shamie’s sister) is alto saxophonist Tia Fuller. “My mom,” he said, “used to tell me stories about how she’d be conducting high school marching and jazz bands while I was still in the womb, so I’ve literally been around music my entire life.” During the summer between seventh and eighth grade, he attended a Jazz House Kids workshop, “and that was when I really decided to get involved in jazz drumming.”

Ryoma Takenaga, a 15-year-old sophomore at the Academy for Information Technology in Scotch Plains, began playing upright bass at age 9 and “started focusing on jazz around the same age. Some of my most important teachers were Jose Rodriguez, who taught me the rudiments of upright bass, and Ed Palermo, who introduced me to the endless creativity that jazz has to offer.”

Takenaga was inspired by “the important role the bass plays in a jazz band. The bassist is responsible for solidifying the groove, keeping time, and creating harmony at the same time.” His jazz hero is Christian McBride. “The way he plays the bass, and the groove he sets for the band continues to fascinate me,” Takenaga said. “I have been fortunate enough to personally meet him and talk to him on several occasions . . . Everything from his soloing style to his large and full sound had made an impression on me. Something about his playing style makes you want to tap your foot or move in your seat when you listen to him, and I aspire to become like that one day.”

Royston has a long list of drumming idols including Elvin Jones, Philly Joe Jones, Brian Blade, Jeff “Tain” Watts, Corey Fonville, Jerome Jennings, and Mark Whitfield, Jr. Blade, he said, “is probably one of the best drummers in terms of feel I’ve ever heard. Mark Whitfield Jr.’s creativity is insane. It’s amazing how he comes up with such creative ideas on the spot. Corey Fonville’s control is out of this world. I was actually fortunate enough to get a couple of lessons from Jerome Jennings last summer. The way he thinks of drums is so profound. When he explains his thought process, it is almost as if he was painting a picture. Every touch, stroke, and rhythm that he plays has some sort of meaning.”

20 May / June 2020 JerseyJazz

Ryoma Takenaga, 3 years ago, with

For Collins-Siegel, it’s two legends and one current pianist: Oscar Peterson, Red Garland, and Christian Sands. “My favorite part about Oscar Peterson,” he pointed out, “is the way he accompanied singers. For example, on the album, Ella and Louis (Verve: 1956), he doesn’t play too much to take away from the singing. Also, he knows the type of chords to play to fit the mood of the song. For Red Garland, it’s how he comps. For example, on ‘Billy Boy’, the chords he plays are super interesting. And if you listen to him solo on something like ‘Straight No Chaser’, he does melodic lines for about the first five choruses. Then, he goes straight to big chords. For Christian Sands, it’s the way he puts the rhythm in his left hand and plays melodic lines in his right hand.”

All three student musicians played with the JTole Jazz Orchestra at the first annual Roselle Park Jazz Festival, created last July by alto saxophonist Julius Tolentino, who is Director of the New Jersey Youth Symphony Jazz Orchestra and Jazz Director at Newark Academy in Livingston. Royston described Tolentino as, “one of the most influential people in my life when helping me improve my skills as a drummer and as a musician. Mr. Tolentino’s passion for the music and knowledge of its history is what really affected me . . . He knows the language, vocabulary, styles, and sounds of not just his own instrument, but all the common jazz instruments. He allows his students to gain their own voice using the vocabulary he has taught them.” At the Roselle Park festival, Royston and Takenaga were featured during the band’s performance of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Night in Tunisia”.

At the festival, Collins-Siegel launched the band’s first number, Thad Jones’ “Counter Block”, with a stride piano solo. “Mr. T.,” he said, “has always pushed me to do things even when I thought they were beyond my ability. He has shown me that I am capable of playing more challenging music than I believed was possible.” Takenaga had “an amazing time” at the festival. “The audience was awesome, and everyone seemed to be engulfed in the music. Getting to play with [guitarist] Dave Stryker was a remarkable experience.”

What does the future hold for these three awardwinning musicians? “If I were offered the opportunity to become a full-time jazz musician,” Takenaga said, “I would gladly take it, but that is not my first option. While I’m not exactly sure what I am going to do for college, I am currently planning on focusing on the computer sciences.” Collins-Siegel plans to continue with music but is also interested in pursuing a career in science. Royston, however, does want to become a full-time jazz musician. “The reality,” he acknowledged, “is that doing gigs and nothing else probably won’t provide a substantial amount of money, so I want to get into writing as well. Some of the trademark colleges that I have been looking at that provide great instruction for both playing and writing are the New School, Berklee College of Music, and the Peabody Institute.”

Finally, what do these young musicians think is the key to attracting more younger audiences to jazz? “I think the best way to attract younger audiences to jazz music,” said Royston, “is to simply educate young people about how hip-hop music -- and any music for that matter-- embodies jazz. What I mean by this is that everything is not straight ahead anymore. You have musicians like Robert Glasper, Terrace Martin, Snarky Puppy, and Terence Blanchard who are taking aspects of jazz and sort of integrating them with hip-hop, funk, and R&B. Of course, this has been done many times in the past, but I think it will have an especially profound impact on young people today, since it is more closely related to the hip-hop pop-culture music everyone is exposed to.”

The key, added Takenaga, “is showing that jazz is not a complicated art form. Many people are intimidated because it is completely different from all other types of music and can sound difficult, complicated, or even crazy at times. I believe kids should be exposed to all different types of jazz . . . If the music gets them to tap their foot, or even start dancing, then you are on the right path!” Collins-Siegel agreed. “A lot of kids aren’t exposed to jazz music, so they don’t even realize they would like it,” he said. “Bringing them to concerts will allow them to discover how exciting jazz music can be.”

In addition to the Soloist awards, the NJYSJO and Charles Mingus Combo won Best Trombone Section and the Mingus Spirit Award at the Mingus Festival. The New Jersey Youth Symphony was founded in 1979 and is a program of the New Providence-based Wharton Institute for the Performing Arts, which serves more than 1,500 students of all ages and abilities. The Jazz Orchestra was formed last year.

May / June 2020 21 JerseyJazz

From left: Ben Collins-Siegel, Ryoma Takenaga, and Koleby Royston.

Photo courtesy of Wharton Arts

with his musical hero, Christian McBride.

Photo by Elinor Takenaga.

A Jersey Jazz Interview with Ingrid Jensen

By Schaen Fox

Trumpeter Ingrid Jensen is part of Artemis, an all female septet founded in 2018 by pianist Renee Rosnes. The group played at the Newport Jazz Festival in 2018, drawing raves from Rolling Stone Magazine, which described its set as playing “like an expertly crafted mixtape, moving from a knotty version of Thelonius Monk’s ‘Brilliant Corners’ to a surprisingly dramatic arrangement of the Beatles’ ‘Fool on the Hill’.”

In November 2019, Artemis signed with Blue Note Records for an album to be released in 2020 and on December 7 performed at Carnegie Hall. The other five members of the band are: tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana, clarinetist Anat Cohen, drummer Allison Miller, vocalist Cecile McLorin Salvant, and bassist Noriko Ueda.

JJ: Who came up with the name, Artemis?

IJ: I did. My husband and I found it. We were looking for Greek goddesses and powerful women. (The Greek Goddess Artemis was regarded as a patron of girls and young women).

JJ: What were some of the highlights of 2019:

IJ: Well, recording for Blue Note with Artemis was super exciting. I closed out the year by playing Carnegie Hall with Artemis. That was a beautiful gig: full house and two standing ovations.

JJ: Is there anything you wish to talk about?