LIVINGLIBERTY USING SEIU ’S TAC T IC S AG A INS T I T [ 4 ] UNION FEEL INGS VS. H A RD FAC T S [ 6 ] ONE-T IME SEIU RECRUI T ER HEL P S IP ’S OP T OU T [ 10 ]

A PUBLICATION OF THE FREEDOM FOUNDATION | APRIL 2017

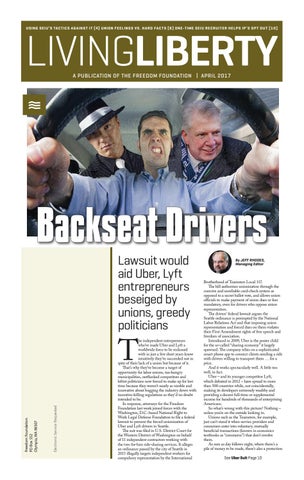

Backseat Drivers Lawsuit would aid Uber, Lyft entrepreneurs beseiged by unions, greedy politicians

Electronic Service Requested

Freedom Foundation PO Box 552 Olympia, WA 98507

T

he independent entrepreneurs who’ve made Uber and Lyft a worldwide force to be reckoned with in just a few short years know intuitively they’ve succeeded not in spite of their lack of a union but because of it. That’s why they’ve become a target of opportunity for labor unions, tax-hungry municipalities, outflanked competitors and leftist politicians now forced to make up for lost time because they weren’t nearly as nimble and innovative about bogging the industry down with incentive-killing regulations as they’d no doubt intended to be. In response, attorneys for the Freedom Foundation last week joined forces with the Washington, D.C.-based National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation to file a federal lawsuit to prevent the forced unionization of Uber and Lyft drivers in Seattle. The suit was filed in U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington on behalf of 11 independent contractors working with the two for-hire ride-sharing services. It alleges an ordinance passed by the city of Seattle in 2015 illegally targets independent workers for compulsory representation by the International

By JEFF RHODES, Managing Editor

Brotherhood of Teamsters Local 117. The bill authorizes unionization through the coercive and unreliable card-check system as opposed to a secret ballot vote, and allows union officials to make payment of union dues or fees mandatory, even for drivers who oppose union representation. The drivers’ federal lawsuit argues the Seattle ordinance is preempted by the National Labor Relations Act and that imposing union representation and forced dues on them violates their First Amendment rights of free speech and freedom of association. Introduced in 2009, Uber is the poster child for the so-called “sharing economy” it largely spawned. The company relies on a sophisticated smart phone app to connect clients needing a ride with drivers willing to transport them … for a price. And it works spectacularly well. A little too well, in fact. Uber – and its younger competitor Lyft, which debuted in 2012 – have spread to more than 500 countries while, not coincidentally, making its developers extremely wealthy and providing a decent full-time or supplemental income for hundreds of thousands of enterprising Americans. So what’s wrong with this picture? Nothing – unless you’re on the outside looking in. Unions such as the Teamsters, for example, just can’t stand it when service providers and consumers enter into voluntary, mutually beneficial transactions (known in economics textbooks as “commerce”) that don’t involve them. As sure as day follows night, where there’s a pile of money to be made, there’s also a protection See Uber Suit Page 10