BEACH

PAINTINGS OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JEFFREY CARR

Frank Galuszka

(Opposite

[Detail ]) Conversation on Moonlight Beach

An Introduction to PAINTINGS OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

I grew up in Southern California, where I now reside. The California landscape’s colors, smells, and textures made me an artist. I was always conscious of the sea. Even if you can’t see the ocean, you know it is there. Where I grew up, in the yellow-colored hills inland, the sky and clouds reflected the distant sea. I attended high school in La Jolla, where the ocean was always present. I would walk down after class to Windansea Beach or the Cove in La Jolla to watch the waves. Body surfers ruled the beach, and dogs with colored handkerchiefs played frisbee with dark-tanned beach kids. My first girlfriend and I made out on the beach to the sounds of surf.

In California, you drive to the beach as you must drive everywhere. At first, roads and freeways dominate your visual experience. You see the dashboard and windshield, the horizontal greys of asphalt and concrete, the shapes of cars, the light on buildings and roadways, and road signs. Then, the glimpse of the distant sea, an aquamarine smudge on the horizon. The sky dominates everything and is rarely pure blue. It is grey, dusty violet, or pink with clouds. The sky contrasts with the blue-gray asphalt and the distant emerald hint of the ocean.

The beach is hidden behind houses, grey-green trees, shops, off-white concrete, signage, and other cars. In Southern California, the sight of the ocean is a valuable commodity and is guarded by houses, hedges, walkways, and palmtrees. When you can make your way through all the visual distractions, the sight of the ocean bursts upon you like a breaking wave. When the beach appears, you see a vast expanse of sand with a slowly expanding ribbon of waves and water. People. Swimsuits. Dogs. Hats. Tents.

The beach is a state of mind. It is supremely sensual. It is changeable and mercurial. It is a boundary, a door, a transitional space between the earth of convention, clothes, and humanity and another world of space, boundlessness, and water. We view the sky, ocean, sand, rocks, and waves. We smell salt and brine, hear seabirds, see waves, and feel the wind. The beach is yellow sand, striped towels, red, white, and brown bodies, bright colored hats, swimsuits, blacks, greens, tans, whites, and blues. You see picnics, sandals, dogs, tanned humanity, and surfboards.

(Opposite [Detail ]) La Jolla Cove with Palmtrees

The beach is about gazing. It is a space of beauty. From the beach, you stare off into the world of the sea. The sea is a watery space bounded by a horizon and sky. It is endless shades of blue and blue-green and the changeable pinks, greys, and whites of clouds, sky, and surf.

You walk along the beach while gazing at the shapes, colors, and textures of people, ocean, sand, sky, and horizon. You experience the sensations of heat, smells, bird noises, sunlight, red shoulders, hot and cold, soft voices, wind, and sand. You are aware of the feel of your body.

You walk along the cliffs, looking down at the sand and ocean. Then you go down the walkways past grass, families having picnics, volleyball courts, and palmtrees. You take off your sandals and walk through the hot sand to the hardpack near the waves. People sprawled everywhere. Kids are digging holes. People in bathing suits. Moms and children. Old folks. Teenagers lying in groups. Folding tables and tents. Dark, angular bodies and beach umbrellas. Puffy clouds. Thin rolls of surf. Bellies. Sunburn. Flat blue sky. Seagulls. The eyes are constantly shifting and moving. You look at the pebbles to the seafoam to a sandpiper, the lifeguard station to a distant red bikini, a child digging to middle-aged strollers to sunglasses to towels to brown legs to hats to suntanned girls to cliffs and back out to the sea again, always thin and ribbon-like soft gray blue and green, dominated by moving shapes of waves and surf.

Artists have depicted the sea as moods: calm, majestic, mysterious, exotic, changeable, stormy, or dangerous. Because we have so much of it, the ocean shore has always fascinated American artists. Winslow Homer painted the violent seas of Maine, portraits of vast sprays of water erupting from dark brown rocks. Edward Hopper painted silent white yachts against blue oceans and distant lighthouses. Edwin Dickinson painted the infinitely subtle grays of Provincetown. Richard Diebenkorn, the great painter of the California seaside, painted elegant abstracted landscapes of Ocean Park, rectangles of pale lilac and ultramarine blue against dusty orange triangles and beige stripes of shopping mall whites and ochre hills.

My love for this beach world permeates my paintings. After a long career teaching and painting on the East Coast and Midwest, I returned to this landscape late in life. It is what the art critic Robert Hughes called “The Landscape of Pleasure.” It is the joy of spectatorship. I was never a surfer or a beach bum. I was always looking and taking it in. Now, I look at it as a painter but also a lover. The beach contains no irony. It is not about reflection or soul searching. It is about pleasure, pure and simple. It is an ideal world of sensations. That is the world I celebrate in my paintings.

Jeffrey Carr(Opposite [Detail ]) Ocean at Del Mar

(Overleaf [Detail ]) Argument at Moonlight Beach

Philosophy underlies these paintings and holds them together. In his work, there is so much that is manifest, so available to be seen, that what is underneath may not be apprehended, though it is not out of reach. Jeffrey Carr makes paintings that fulfill and delight both him and us. His philosophy is not explicit because he doesn’t mean to sell it to us through his paintings. A spirit finds form in his work. In his view, everything is imbued with spirit, vitality, playfulness, and joy. Seeing no contest between pleasure and order, desire, and ease, his work descends most directly from Matisse’s groundbreaking 1904 work Luxe, Calme et Volupté, which in turn is inspired by Baudelaire’s Symbolist poem L’invitation au Voyage and its lines:

There, all is order and beauty, Luxury, peace, and pleasure.

While Matisse forges an alliance between Postimpressionism and Symbolism, with reverence for the light of one and the sovereignty of imagination of the other, it is through synthetic form, a built defensible style, that he holds these together in the artistic pre-psychoanalytic explorations of mind that hadn’t yet funneled narrowly into surrealism, and, with Matisse, would diverge from the powerful influence of Munch to aim at visually structuring happiness, rather than anxiety and pain. An artist can admire and be influenced by another artist without imitating them. Carr reflects on the findings of Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté, without imitating the master, except that he chose the same site, the seaside, as the theater for his paintings.

Carr observes and invents seamlessly, as it is hard to determine where one ends and the other begins. The phenomena of the natural world exist in his work intermingled with invention, and the invention is provisional – it is play. That he can unite the characters and behaviors of people-as-figures with often lavish abstract conceits of arrangement so effortlessly is more than I can understand or explain, but he does this.

Who are these people who populate his paintings? There is no sense of artificial drama. There are no villains or particular saints among them. Their behaviors are depicted, and yet all of them are also seen through their actions to the underlying quality that they share, that all people share. They even share a part of this, or some of this, with the sky, the surf, and the beach. A young woman is angry with her boyfriend, but that, and the argument between them, is contextualized as a superficial incident in the eternal life of both of them. And we know this is so as we look at the painting.

Frank Galuszka

La Jolla Cove with Palmtrees • 24 by 30" • 2022

La Jolla Cove with Palmtrees • 24 by 30" • 2022

The low light is pure and beautiful. The palms nearest us are bluish, as shadow deprives them of the golden low light that richly saturates the world beyond. We want to go to that light. The light tenderly, as if lovingly, colors the sky. The far ocean vista becomes sharp and brilliant. In the middle-ground shadow are a pair of headlights that stand in for the sun that we know is out there at our destination, but cannot yet see.

Frank Galuszka Ocean at Del Mar • 24 by 30" • 2022

OCEAN AT DEL MAR

Ocean at Del Mar • 24 by 30" • 2022

OCEAN AT DEL MAR

The light of day is full of obscure promises. In its new moment, it is a shock of blue and white. This is the first chapter of the joy of life. The modern West Coast philosophy is embodied here and now, this eternal freshness, this Riviera.

The brilliant blue identity of this painting is emphasized by the restrained and careful placement of other primaries, the bent double yellow line that angles to a “stop,” and the cool unlit red tail lights on the right, counterbalanced by the single spot of sizzling vermilion on the left.

In this painting, the viewer is the driver, and the driver is joyfully and expectantly heading for the beach. The command to stop applies to the oncoming lane and not to him. He’ll be leaving behind the parked cars on his right. He is going where the walking figures on the left are going.

We are going to the beach with Charlotte. She is our companion and guide.

Her violet hat gives the color of this painting its full identity. The curve of the top of her hat is echoed by the dark hollow in the unfurling wave ahead. This painting reminds me of Matisse’s love for the beach. The violet color of Charlotte’s hat and her face turned toward us in the foreground, together with the palms and the long view to the horizon, reminds me of Bonnard’s painting, The Palm.

To those poor souls who dwell in Night, But does a Human Form Display

To those who dwell in Realms of day.

William BlakeIn Jeffrey Carr’s paintings, the idyllic becomes indistinguishable from the commonplace. You could say the idyllic becomes mistaken for the commonplace. The Arcadian idylls of Puvis de Chavannes and Poussin come down to American earth in Carr’s paintings. Matisse and Bonnard created idylls, and Picasso also created them in his own way.

For America, David Park and Bob Thompson, too. The Bay Area painters celebrated the California sun. Of them, Diebenkorn was the most significant. But as to the sybaritic, he held back. He painted the Golden State with reservations. Stopping short of exaltation, checking hedonism with a resistant toughness of mind, a refusal of seduction, a refusal to forgo the expressionistic anxiety that was the spirit of his time, creating a tension between the times and the place.

Even today, the challenge for the contemporary painter is how to move past superficiality and the trivial when faced with abundance, beauty, and pleasure. Is resistance to this a kind of cowardice? A lapse into intellectual pride? The question is, how to see into the pleasure of living without yielding to feel-good clichés on one hand or soulless analysis on the other.

Jeffrey Carr’s story of the beach is a human story. It is the story of people having left their ordinary and often workaday lives in a search not only for relief but happiness. And on Carr’s beaches, people find that happiness. A sense of well-being permeates throughout.

When approaching the figure, some painters are stymied from the start by political self-consciousness, from the difficulty of the task of representation, from the concern of revealing too much, and a retreat from psychological disclosure. Jeffrey Carr suffers from none of these problems.

Some figure painters approach the body as a problem. When it comes to the figure it is a struggle to get things right. As a complex three-dimensional object in space, the technical issues crowd out expression.

As a technical problem, the body is a complex object that requires adequate description. Artists may seek refuge in expertise, expertise in anatomy especially. What too often results is an admired but ultimately lifeless realism, in which the body is more or less a widget among widgets in the universe.

Carr is mindful of something beyond the body and beyond the personality. He is asking, without drawing too much attention to it, what does it mean to be a human being? He is not painting an answer or even clarifying the question. He is looking deeply into it without the expectation of finding an end, a stopping point. He opens a human space in his paintings. Further, he sees into the human being, into the human space within a world that has much in common with it.

What permeates the ocean and the sky permeates us. Floating on the top of our being are appearances and behaviors. Humans exist in a spiritual ecosystem that includes all elements of reality. By painting in such a way, Carr makes this ecosystem feel apprehended but not analyzed, not turned by analysis into an object like any other. Everything in his paintings is alive in a shared reality. This reality is beneficent and repudiates the toxins in our world of theory, certainty, ambition, and power. Paradise is here, as Jacob Boehme declared. Jeffrey Carr says the same: Paradise is here. It surrounds us. It is right in front of your eyes.

Frank Galuszka Surfers at Torrey Pines Beach

Surfers at Torrey Pines Beach

One little girl is looking at another. The taller girl is caught mid-stride, her foot lifted above its shadow. She carries, it seems, a sandal or flipflop in each hand, maybe swinging them as she walks. The smaller girl is younger and admires the taller, older girl, who only has eyes for a procession of surfers.

The world of adults is concealed. A standing woman, perhaps the mother of one of the girls or maybe just on her way to the surf, is burdened with the things of adulthood. Maybe she has paused to talk with another person her age. We can’t tell. Their world doesn’t matter. Only the little girls and the surfers count in a world that belongs to the young.

Mickey Mouse looks our way. His meaningless iconic gaze contrasts with the vitality of the gazes of real people: the two girls, the two surfers whose faces we can see, perhaps the man standing up the steps of the lifeguard station, also young, taking in the whole scene, and more, with his long view and the relaxed stretch of his body.

The clustering of forms on the left side, the single surfer ending his ride, and the light of the painting shared between sunshine and shade. The woman’s face is concealed, and whatever hijinx or simple task behind the blue umbrella tantalizingly conceals itself from us.

Bathers at Torrey Pines Beach • 32 by 38" • 2023

Bathers at Torrey Pines Beach • 32 by 38" • 2023

The empty middle. The diagonal composition. The green surfboard that looks like it already belongs to the sea. The blue towel around the foreground girl recollects the drapery of Titian’s castaway Ariadne; the family group that she seems to be a straggler from, its determined mother who you can tell works hard for a living, the mellow knife of green ocean, the descending diagonal edge of cloud perpendicular to the stairway.

Above the beach, the observing guard is like a guardian or protector and an angel looking down on human toil and folly. This painting is about going. It is about destination. And again, it is about promise, about the wonderful time to be had somewhere up ahead, somewhere between here and the hill peninsula that marks the farthest point before the beach is no more.

The bottom of the tipped-over stanchion at the bottom of the stairs of the lifeguard stand, a boy’s foot perhaps resting on the tipped-over cone, the eloquent geometry of the lifeguard stand itself, its ladder, its railing. The white strap on the mother’s shoulder is at an angle to her body but perpendicular to the white waves near the horizon it points to.

Each detail is a pleasure to consider. For instance, the small figure of the man in shadowed red or maroon trunks, his back turned to us, far, far to the left, seen through a triangle formed by the side, the platform, and the support of the lifeguard stand. These are paintings you can look at forever, discovering such details, drawn by allures, mysteries, emotion, and painterly intelligence. There is a love of the world in these paintings, including the things of the painter’s craft, the paints, the brushes, and the color itself.

Blue Umbrella at Laguna Beach • 28 by 34" • 2022

Blue Umbrella at Laguna Beach • 28 by 34" • 2022

The simple yellowish finial of the blue umbrella is an outpost, a tentative colony of yellow in a world of blue. Alone, as a lonely yellow, in all that blue, the cerulean sky, the ocean, the dual blues of the umbrella itself. The finial is echoed in the topknot of the standing woman’s hair and, further down, by the blue hat of the sitting woman facing left.

Boardwalk at Laguna Beach • 28 by 34" • 2022

Boardwalk at Laguna Beach • 28 by 34" • 2022

Another painting about light and about blue. Without being obvious about it, the blue umbrella on the left visually converses with the ocean. Its stripes reiterate the waves. Both space and two-dimensional pressure are created by the figure standing between the umbrella and the ocean.

Notice the atmospheric perspective created between the umbrella and the figure by way of color, from brilliant pure blue to the neutralized color of the figure’s skirt. See how many beach chairs and objects are blue and how many different blues there are. Also, the perspective of the boardwalk planks continues on toward the horizon through the cunning placement of a beach towel on the sand and how the violet fabric with white dots that is laid upon it stops the perspective from moving too swiftly and artificially from planks to towel toward the horizon. The violet is the right choice not to interrupt the flow too much to make a connection between planks and towels.

Pink Umbrella at Laguna Beach • 28 by 34" • 2022

Pink Umbrella at Laguna Beach • 28 by 34" • 2022

Tent canopies converge toward the blue-topped tent. Bands of color rise from bottom to top: sand, surf, ocean, fog layer, cerulean sky, through a jumble of side-to-side interference.

The pink umbrella would be a commanding destination if not for the crisp, bright shape of red trunks exiting the framing edge of the painting on the left.

Figures weave through from the right, and figures create a network of glances between us and the sea.

PINK UMBRELLA AT LAGUNA BEACH Conversation on Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

Conversation on Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

They are friends who have just encountered each other by chance at the beach. The foreground figures are having a conversation. The girl on the right and the (perhaps) boy and girl on her left. The unseen words that are spoken pass parallel to the picture plane and, even though invisible, are a key part of the composition of this painting. As much as the visible words of the angel Gabriel in Simone Martini’s early Renaissance annunciation are a part of its composition.

In the middle ground are some figures that are also positioned to reaffirm the picture plane, one positioned with a hand to his bent head behind the invisible conversation and the other positioned far to the left of the picture beside a bent-over companion. The two young men are linked compositionally and reiterate the foreground group, contrasted to it as they don’t seem to know one another. Further back, there is a man looking toward the viewer. He is gesturing with his arms, and behind him, a succession of figures is positioned so as to bring us deeper into the picture space from parallel station to station.

I count nineteen figures in this composition. The light is faceted over the bodies of the nearer figures, most starkly in the lean belly of the girl on the left who holds one hand up as she unselfconsciously plays with her hair. She is the one speaking. Her impudent, deftly painted navel calls to mind bathers in the paintings of David Park.

Of the two conversants on the left, one is talking at this moment; the other is now listening. In how they are painted, how they are represented, these are a softer pair than the solitary girl who stands in a striding position on the right, and whose body is distinctly firm and muscular, and her head, flattened, and in shadow, more anonymous than her body, a cipher, so that this particular figure doesn’t dominate the painting too much, as the sun pays so much attention to her body. The sunlight carves her buttocks with a cooled but admiring analysis that reminds us of Euan Uglow.

Note the placement of green and the additional distinction of profile with the braid, enhancing her individuality as an extroverted character. Her personality is so strong that it takes two characters to hold up the other side of the conversation in this encounter.

Paddleball at Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

Paddleball at Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

As the invisible conversation joins figures in communication in the painting Conversation on Moonlight Beach, the ball being paddled, seen, or unseen connects the attention of the players and their lines of sight in the imagined arc of its travel. The foreground provides a still life that stretches from side to side, its colors communicating with bathing suits and paddles. At first glance, these are the places we are meant to look.

In these paintings, bright artificial colors are accented and distinguished, separately classed, from the colors of the natural world. With the exception of blue. The artificial and the natural meet in the figures, where clothing, particularly bathing suits, are made to coexist, sometimes alarmingly, with flesh. This makes the figure the focus of unity between the natural and artificial and says something about the unique position of being human between nature and culture.

But in these paintings, a special status is reserved for the color blue. The sky and ocean are blue, but so are many of the umbrellas, tents, and towels. Sometimes, on the horizon, there is an elision of the artificial into the natural, a visual fusion, where the blue of an umbrella edge might be mistaken for the blue of the sky. A color can have a symbolic meaning as well as descriptive and formal value. It is through blue in these paintings that one realm, or one quality of reality, opens to another.

Circle of Friends at Moonlight Beach • 28 by 34" • 2021

Circle of Friends at Moonlight Beach • 28 by 34" • 2021

Mise en scene. The circle of friends might be a reference to the circling dancers in Matisse’s Joy of Life and Dance paintings, if only unconsciously. The linking energies of people in this heterarchy are something special, and the axis of the circle, the center of its energy, is palpable but intangible.

These paintings always have the impression of a strong but hidden unity. Compositions are firm. There are matters of form and time. The momentary, a gesture, or an effect of light, plays against the enduring, the beach, the rocks, and the ocean. The artist has created dialogs in time within the timeless reticence of each painting.

Party at Ocean Beach II • 28 by 34" • 2023

Party at Ocean Beach II • 28 by 34" • 2023

You can hear them talking. Pastel canopies overlooking the luminous ocean, standing around a cooler, the beach now very yellow in the changing, lowering light, strong yet understated horizontals, the jetty and the green towel spread across the beach, the long grey-green horizon. Shots of red. A triangle.

Eight Kids Playing at Moonlight Beach

Eight Kids Playing at Moonlight Beach

The title is a challenge. Find the eight kids. Digging in the sand, building things. Skittering off in pink. Dealing with a big red bucket. At the center, a vertical figure, looking down, in a rare formal sober black tank suit (is she from New York?), the world revolves around her. A reverse view from the surf looking inwards to the eroded stony terraces, the light shifting from left to right, the shadowed right side redeemed from fading away entirely in space by the multicolored umbrella from Santa Cruz Cove.

Santa Cruz Cove at Ocean Beach • 32 by 38" • 2023

Santa Cruz Cove at Ocean Beach • 32 by 38" • 2023

Stripes and rocks.

Looking down on the figures on the beach from above. Stripes as theme and variation from left to right: green and white, blue and white, yellow and white, more blue and white, a dark red or maroon and white, ending at the right side edge with sizzling yellow and orange, and sitting on it an iconic sculptural fertility goddess, brown, near-nude, in a thong. In the surf and on the water’s edge, scampering skinny kids. Three men lined up on a rock. A system of interlocking vignettes circling around the axis of a multicolored umbrella.

SANTA CRUZ COVE AT OCEAN BEACH Three Hats on Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

Three Hats on Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

The light is mellowing into late afternoon. Such beautiful light. Especially where haze has subtly slipped in, diffracting, making light in the shadows of the distance, bright colors act as anchors, including a broken diagonal of quenching green.

Kids at Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

Kids at Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

Grey light. Cooling off. Picnic table, volleyball nets, trash cans, and recycling.

Surfer’s Walkup at Moonlight Beach • 22 by 28" • 2020

Surfer’s Walkup at Moonlight Beach • 22 by 28" • 2020

A landscape. Powerful light and shadows on worn cliffs contrast with the pale skin of a woman in a white hat, enthroned as it were, in her beach chair, the reflected light of the beach washing the shadows from her pale legs, now become nearly lavender where the shade should be, luminous in the empire of light.

People alone and together. Play, meditation, sunbathing. Architecture. Plant life. Generous growth. Scenes within scenes.

Charlotte calls to someone. The artfully preserved “negative space” between her finger, nose, lip, and hand is marvelously and solidly painted. A brushstroke of beach-colored paint traces her hat, and a stroke of shadowy sand color traces its brim.

Both separate her in space from the distance and assert her foregrounding. Nearing the level of the horizon, detail and clarity dwindle behind her in stages. Yellow dominates the left side of the painting; blue dominates the right side. A yellow surfboard against the blue on the right compensates for a blue umbrella against the yellow on the left.

Charlotte has been our guide through this world. We follow her. The orange strap across her back is essential to her authority and this composition.

Orange Hat at Laguna Beach • 22 by 30" • 2022

Orange Hat at Laguna Beach • 22 by 30" • 2022

Under the bright orange hat, his face is in shadow. He gazes somewhere with serious attention. Above, the shape of the hat is confirmed by an orange umbrella.

Leading with her chin, she stands bolt-straight, her cap and tilted head defiant. Straight himself, he leans forward, making his case. His argument won’t work. She is immovable. A channel filled with water divides them.

Paddleball at Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

Paddleball at Moonlight Beach • 24 by 30" • 2021

The red ball hangs in the air, the green paddle that has smacked it beneath it. Some fresh scruffy painting on the two figures on the left. On the cluster of objects beside them are the two blue chairs, with ambiguous pink and yellow things. Atmospheric perspective dims the colors on the right.

As we go back in space, the cliffs and sky turn grey, indistinct. One walking man, singled out by the light, tacks the right side of the painting and affirms something about space and distance that transfers to the paddle ballers so that we can appreciate more strongly exactly the dimension of space between them. The shadows slant toward the sea.

Crowds at Torrey Pines Beach • 32 by 38" • 2023

Crowds at Torrey Pines Beach • 32 by 38" • 2023

A Painter’s Note:

FIGURES IN A LANDSCAPE

A painting of a group of figures enjoying themselves in a rural or pastoral setting is called a Fête Galante. It’s a term from art history for paintings that depict elegant couples enjoying themselves in beautiful gardens. The idea goes back to the Renaissance painters and beyond them to classical antiquity. The painting, Crowds at Torrey Pines Beach, is a contemporary Fête Galante. What is it that gives us joy by being on the beach in the sun, together with our friends and each other? We love the chance to take off some or all of our clothes, play, and observe each other bathing, setting up a picnic, or digging in the sand under a bright blue sky. The artist observes and records our pleasure at being with each other at the beach.

Jeffrey Carr

A Painter’s Note:

COMBINING THE FIGURE WITH ARCHITECTURE

Composing paintings creates all kinds of challenges for an artist. How do you combine the irregular, organic shapes of people with the regular, geometric shapes of buildings? Another challenge is relating different sizes; buildings are big, and people are relatively small. How do you make it work together? One way is to put people inside the buildings: the figure in the interior. Another is to make the buildings a similar size to the people. You see this in early Renaissance paintings. An even better solution is to make the people in front and the buildings smaller in the distance, the way a classical painter might make a group of shepherds in front of a distant Greek temple. If you are painting a beach in Southern California, you can put a group of figures in the foreground with a background of suburban houses!

A girl striding against the incoming surf. The many colors of the light on the water. The fluorescent bikini is an early work. The painterly scrambles of color around the two figures on the right reveal the corrections of the struggle to get things right. This solidifies the forms, locking them into the painted space while giving them room to breathe. It is here that the integrity of the painting is made known.

(Above) Blue Umbrella at Mission Beach • 28 by 34" • 2023

(Above) Blue Umbrella at Mission Beach • 28 by 34" • 2023

The shadows in the depressions on the beach have deepened in tone. Whatever the day has been is moving on. The color of the beach shifts from left to right, giving a sense of richness to the light. Every shadow is full of life. Look at the masterful scramble of blue and grey paint, creating the beach shaded up front in the middle of the painting by the umbrella. The late-day glare on the ocean. White.

The day, for some, begins to slip into memory. A man, with his head tilted downward, considers some private thoughts. A woman on the right picks up a towel, resigned to going home. The low sun illuminates the transparent plastic of the orange bucket and shines through the reddish mesh on the back of a beach chair.

Stone Lantern Late Afternoon • 24 by 30" • 2021

STONE LANTERN LATE AFTERNOON

Stone Lantern Late Afternoon • 24 by 30" • 2021

STONE LANTERN LATE AFTERNOON

The beach is gone. We are at home. The colors of the day’s end are becoming lush, saturated. Even the fence is full of color, red on its left side; blue on its right. All the people are gone. This is a moment not so much of recollection but of meditation. The stone lantern suggests a moment of peace and contemplation. The flowering pruned tree speaks of enduring life. It speaks of tomorrow. Sunlight slices brilliantly through the shadows.

Dusk Over Point Loma • 24 by 30" • 2020

Dusk Over Point Loma • 24 by 30" • 2020

Someone must be pouring drinks or starting dinner in the house. The day is remembered. The rooftop is blue. Flickers of yellow and blue leaves. Deepening shadows.

Sunset Over Lemon Grove • 24 by 30" • 2020

Sunset Over Lemon Grove • 24 by 30" • 2020

Light shines through some skylights from below. As the day’s sky moves from beauty to beauty at sunset, it is fulfilled as color saturates into deepest richness. With a red corona, the last of the sun gleams through the tree. The rooftops’ pitch to support our eyes, adoring its splendor.

Sunset Over Pacific Beach • 24 by 30" • 2023

Sunset Over Pacific Beach • 24 by 30" • 2023

Here is the sun, reddening the sky as the colors descend through a robust and tawny rainbow. Orange, red, yellow, pink, violet, blue, green, and, toward the bottom, yellow again. The red flower is a counterpart to the sun.

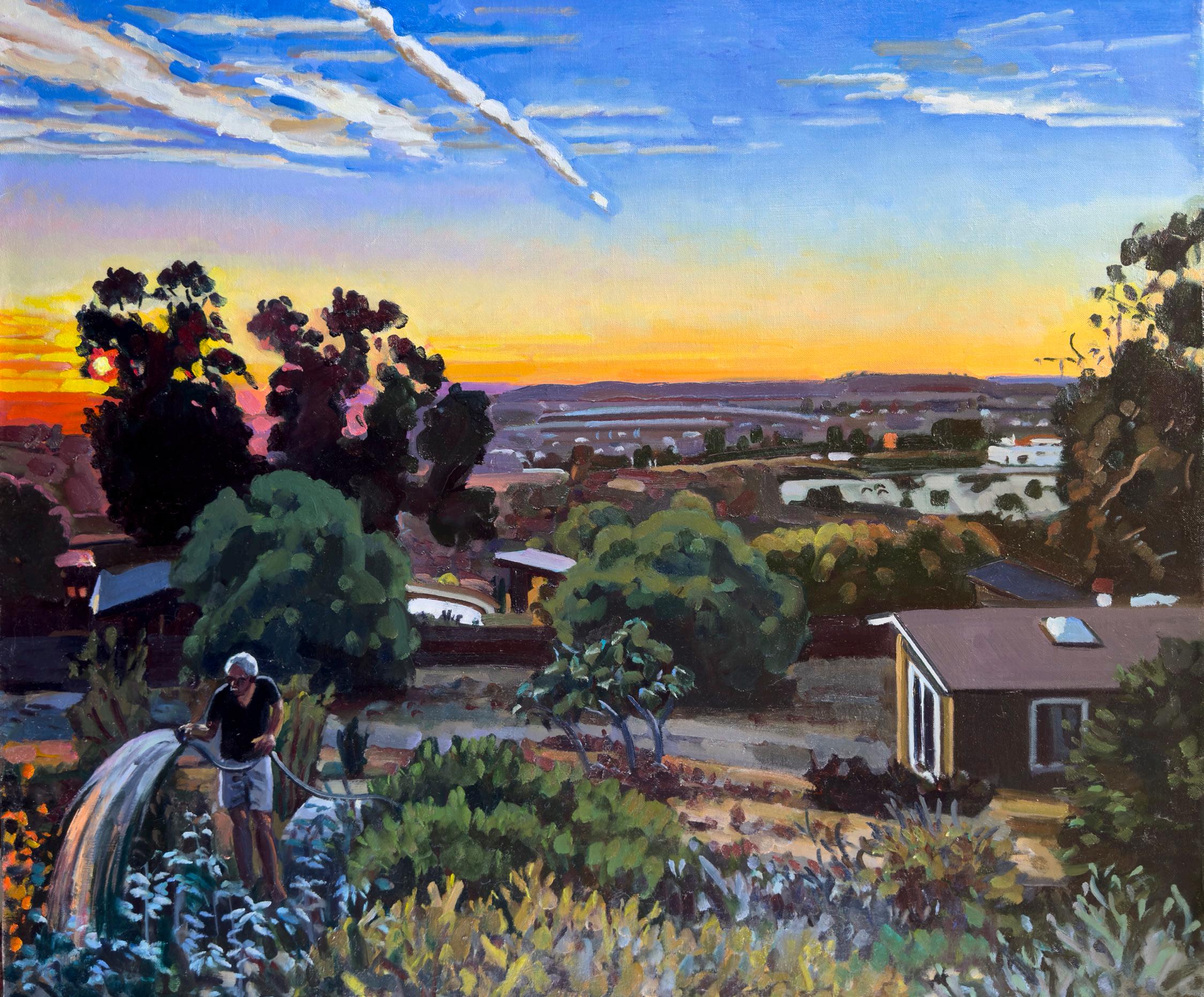

Self Portrait at Sunset • 32 by 38" • 2022

Self Portrait at Sunset • 32 by 38" • 2022

A self-portrait that captures the stance and posture of the artist as an incidental figure in a grand view, the top of his head illuminated, is echoed in shape by a tree behind it and the arc of the water from the hose. A portrait of the artist not as a painter but as a gardener tending to the plants that are his companions under the sky in the world. The sun is a witness.

Nightscape over Point Loma • 24 by 30" • 2020

Nightscape over Point Loma • 24 by 30" • 2020

The sun may have left us, but it remains through its surrogate, a brilliant city light shining through the trees. The grey-blue sky is new again, mirrored on the roof of the house below. The backyard of the house below is lit; the light comes through the slats of the fence and bleaches the color of plants near the door to the palest green while the trees that stand against the new night are deepest blue, nearly black, in their shadows.

Jeffrey Carr is an artist and educator with a long career teaching at numerous art schools and universities. He was the Dean of the School of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, PA., from 2003 to 2015, and was the Chair of the Department of Art and Art History at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

He has been the subject of one-person exhibitions in New York, New Haven, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Indianapolis, St. Louis, San Diego, and Montecastello, Italy, and has been a visiting speaker or panel participant at over a dozen art schools and universities. He has published a number of interviews and articles on contemporary artists.

Since his retirement to San Diego, he has returned to an early love of painting the landscapes of Southern California and to smaller-scale figure painting.

Originally from La Jolla, California, he graduated from the University of California at Santa Cruz, attended the New York Studio School, and received his M.F.A. in painting from the Yale University School of Art.

“I create my paintings in a small studio in Spring Valley, California, on a property I grew up on. From my house, I see wonderful views of the southern California landscape. There’s a hint of the ocean and the desert where I live, and there’s light unlike any other; sometimes pale yellow, sometimes russet, sometimes slate grey. I paint an ideal; my experience of being alive to the presence within a place.”

Website: Jeffreycarrart.com.

Inquiries: Jeffreycarrart@gmail.com

Painter Frank Galuszka has had solo exhibitions and group exhibitions at important venues all over the world. He is a Professor of Art at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he teaches painting and drawing. He also taught at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia from 1974 until 1995 and at a number of other art schools and universities including Vermont College, the Studio School in New York, and the Aegean School of Fine Art in Greece. He lives and paints in Santa Cruz, California.

Galuszka is a noted writer on art. Of his own philosophy of painting, he writes:

“I am interested in style, especially its psychological significance. I regard style, in the practice of painting as enacted by a professional painter – by that, meaning a painter who works out of continuous daily practice – as something which emerges unconsciously out of the altered state of consciousness – or trance – to which the artist submits in the course of the practice.

While planning, ideas, and theory may set the stage for an artwork or attend its postmortem, the process from which style emerges is a special state in which attention is focused, narrowed, filtered, and distorted in a way that resembles, in turns, autism, paranoia, meditative states and ‘split personality.’ The afterglow of the experience can resemble mania or mystical experience.”

Website: frankgaluszka.com

(Front Cover [Detail ]) Surfers at Torrey Pines Beach

(Back Cover [Detail ]) Santa Cruz Cove at Ocean Beach

© 2023 Jeffrey Carr

Design: Terry Peterson