FALL 2025 LIFESTYLE IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES

The Brown Trout Paradox

Ranching Resources: From Beavers to Smart Collars

John Colter: Montana’s Legendary Mountain Man Saratoga, Wyoming’s Healing Waters

The Brown Trout Paradox

Ranching Resources: From Beavers to Smart Collars

John Colter: Montana’s Legendary Mountain Man Saratoga, Wyoming’s Healing Waters

We create timeless houses. You create priceless legacies.

"...You know the deal. Horses and cattle may be how the West was won, but death and taxes is how we're gonna lose it."

Network "Yellowstone": Season 4, Episode 2 IRS Estate Taxes Take 40% of Every Dollar of a Couple's Net Worth in Excess of the Estate Tax Exemption Limit.

HOPE IS NOT A STRATEGY

Let us show you how to cover large estate tax liability exposure with:

• No out-of-pocket insurance premiums

• No out-of-pocket interest expense for premium financing

• Eliminate premium finance payments already in place

Only $100 in consideration. Over $5 billion in transactions since 2009 helping high net worth families create tax-free capital to cover estate taxes or provide funding for buy/sell agreements to preserve their family wealth legacies.

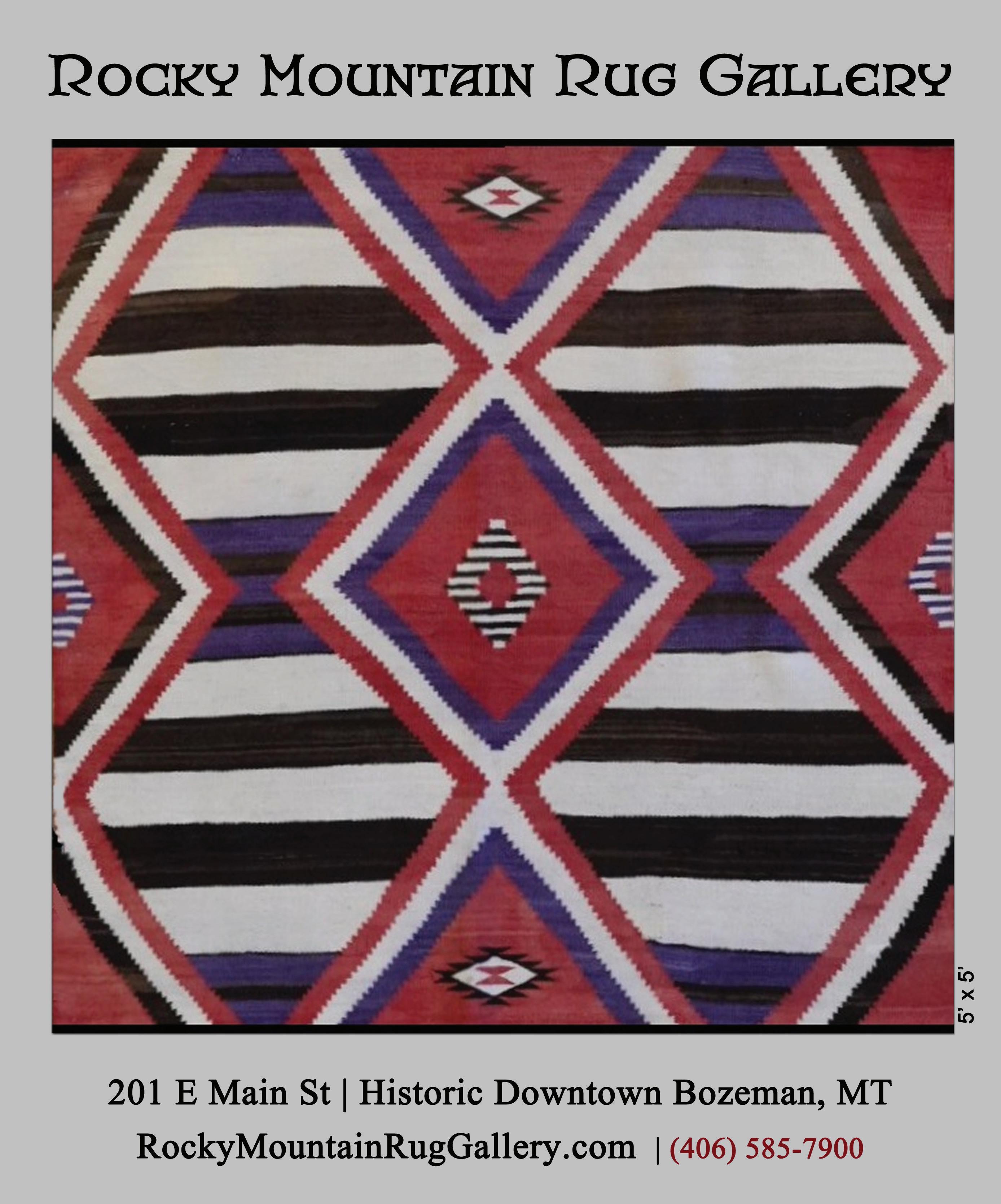

whether you’re just starting to explore your options or ready to proceed with buying or selling –we will come to you.

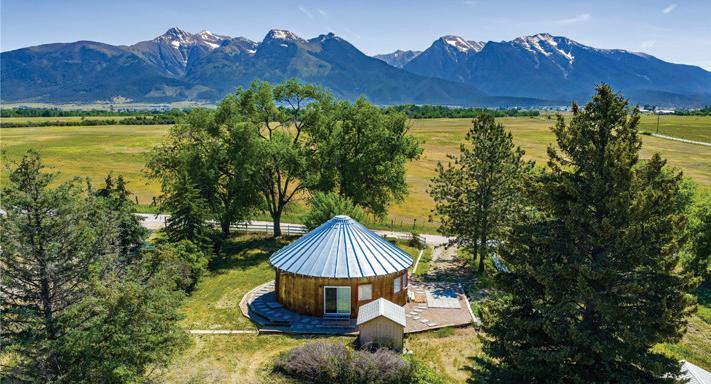

bozeman, mt | 163± deeded acres

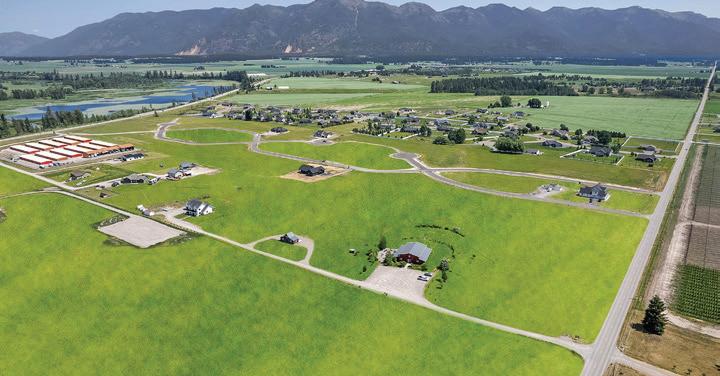

choteau, mt | 2,541± deeded acres offered at $10,400,000

96 THE BROWN TROUT PARADOX

Angling icon, invasive menace, or both?

Written by E. Donnall Thomas Jr.

Photography by Jakob Burleson

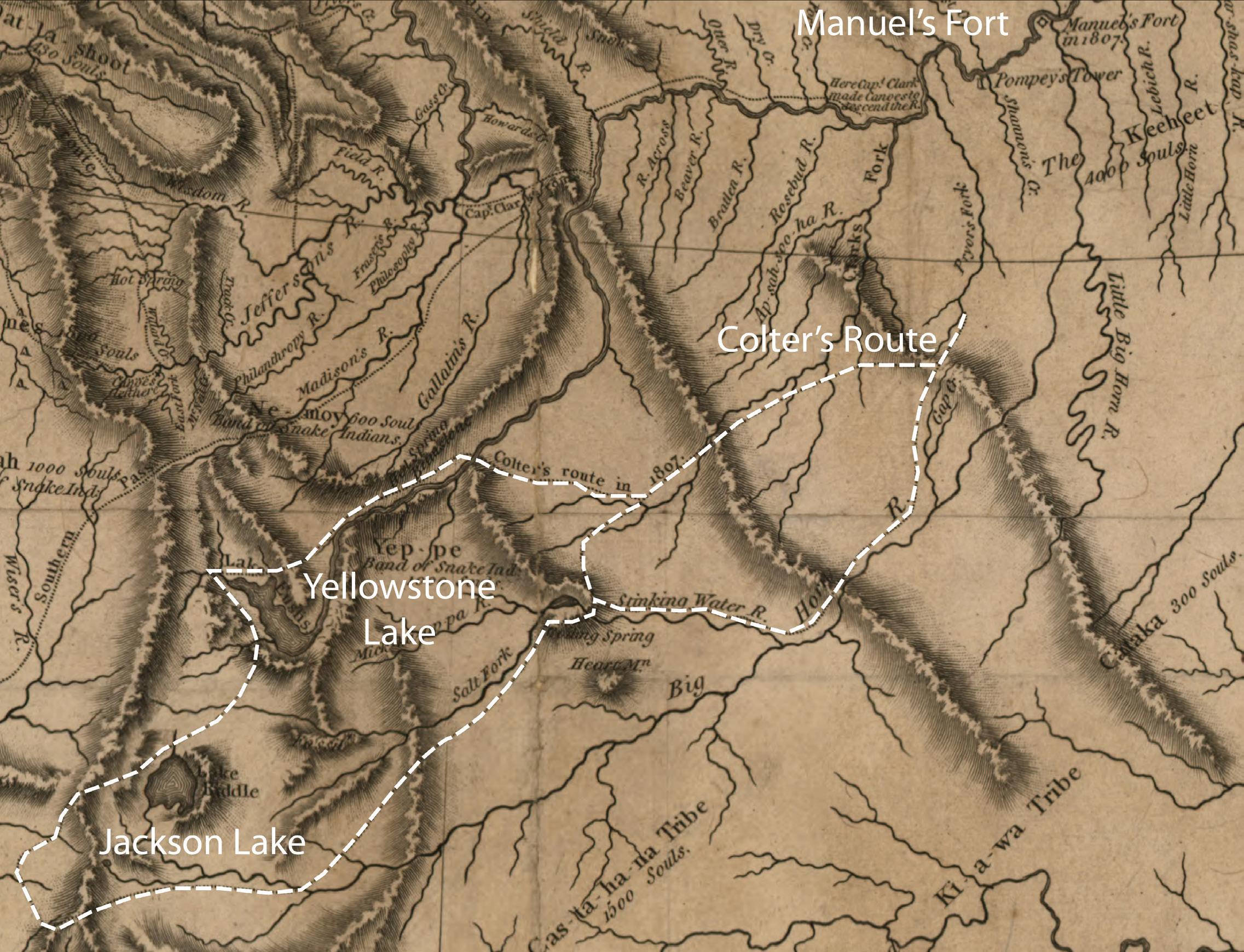

104 THE EXPLOITS OF JOHN COLTER

Montana’s legendary mountain man

Written by Douglas A. Schmittou

112 WEST WING

Making a difference for a desert bird

Written by Kris Millgate

120 EXCURSION: MONTANA’S INLAND SEA

Bounty under the Big Sky

Written by E. Donnall Thomas Jr.

134 SOAKING IN SARATOGA

The timeless treasure of healing waters

Written by David Zoby

Photography by Natalie Behring

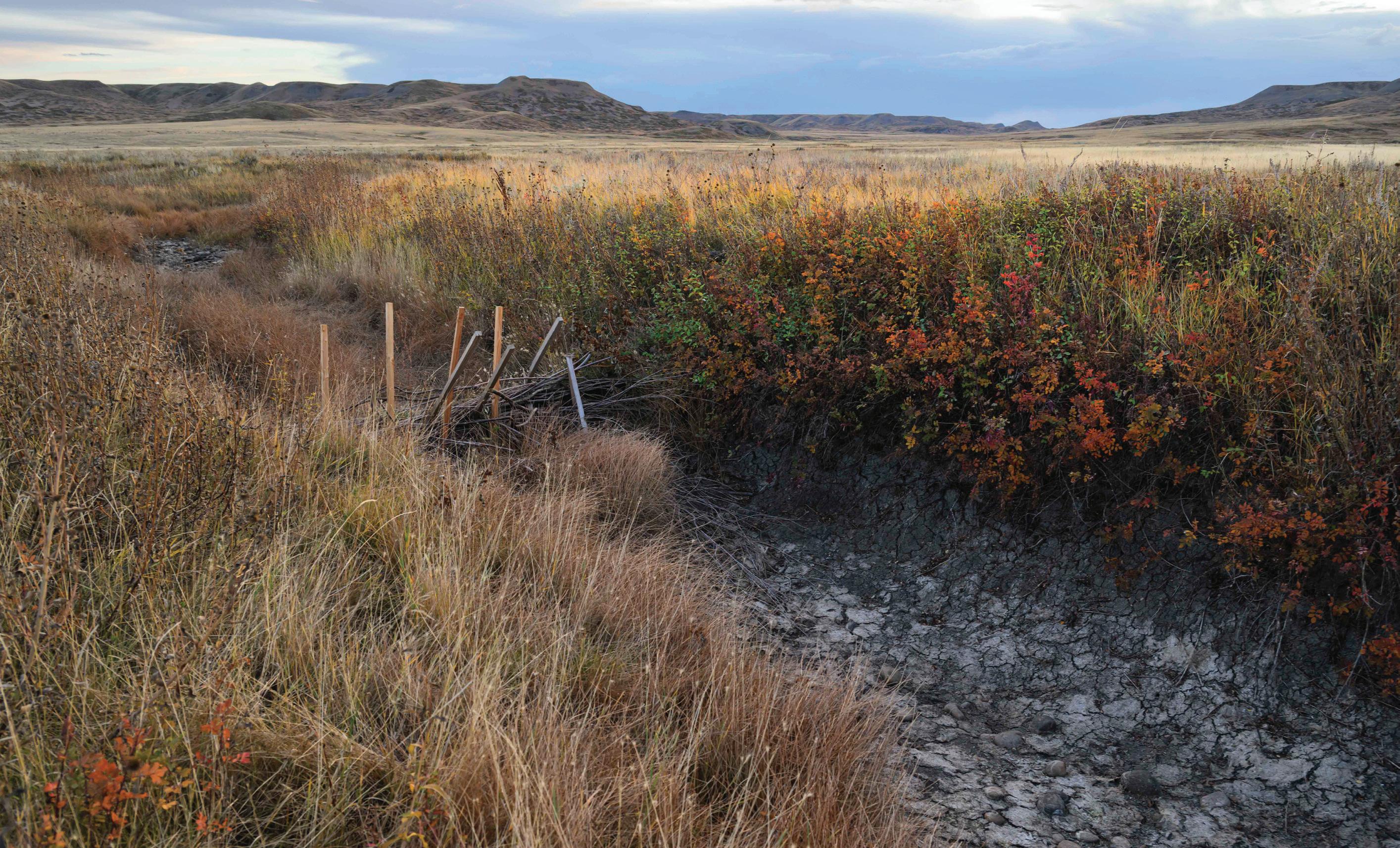

144 FROM BEAVERS TO SMART COLLARS

Montana’s dryland farmers and ranchers tap into traditional and hi-tech resources to thrive

Written by Andrew McKean

42 Dining Out

Simple Wonder: At Bodhi Farms’ Field Kitchen Restaurant in Bozeman, Montana, everything is local and local is everything

Written by Carter Walker

Photography by Lynn Donaldson

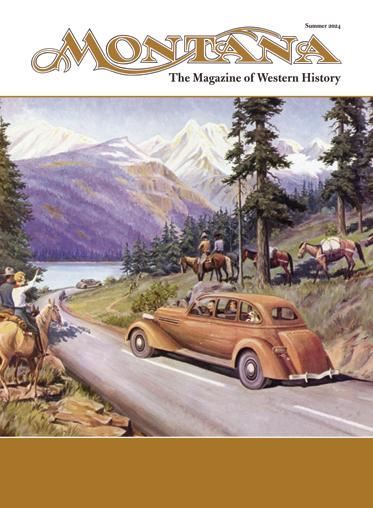

50 History

A Horse of Mystery: Ogden the Westerner’s $1.6-million upset

Written by Catharine Melin-Moser

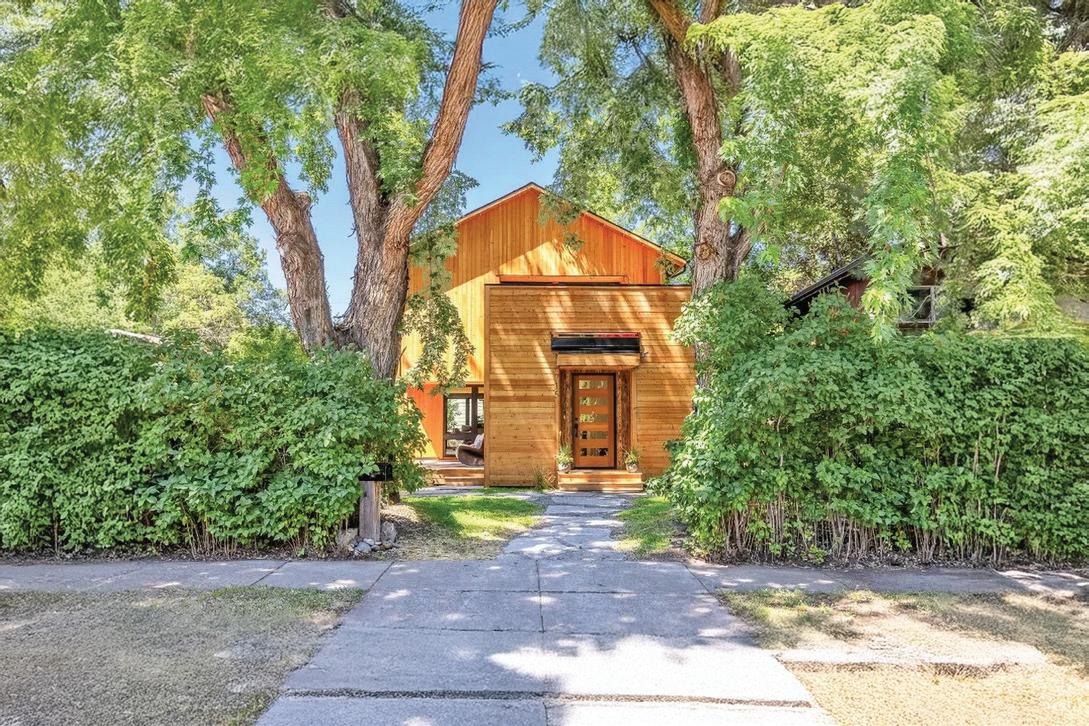

60 Western Design

Montana Panorama: Poised on a ridgeline above Bozeman, a home inspired by mid-century modern style celebrates 360-degree views of the Gallatin Valley

Written by Norman Kolpas

Photography by Whitney Kamman

68 Outside

An Active Participant: Cultivating connection with the natural world

Written by Douglas Wadle

Illustration by Bob White

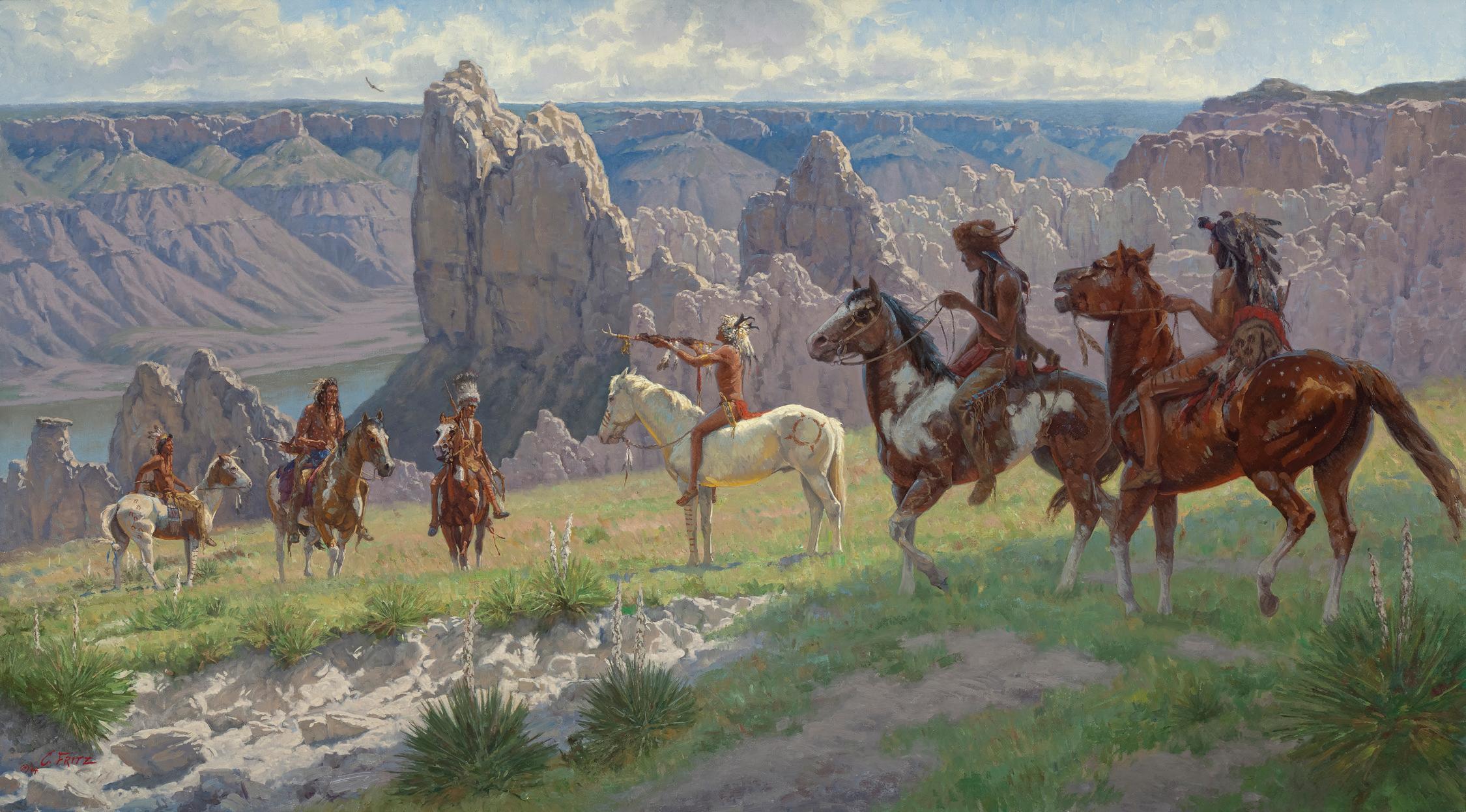

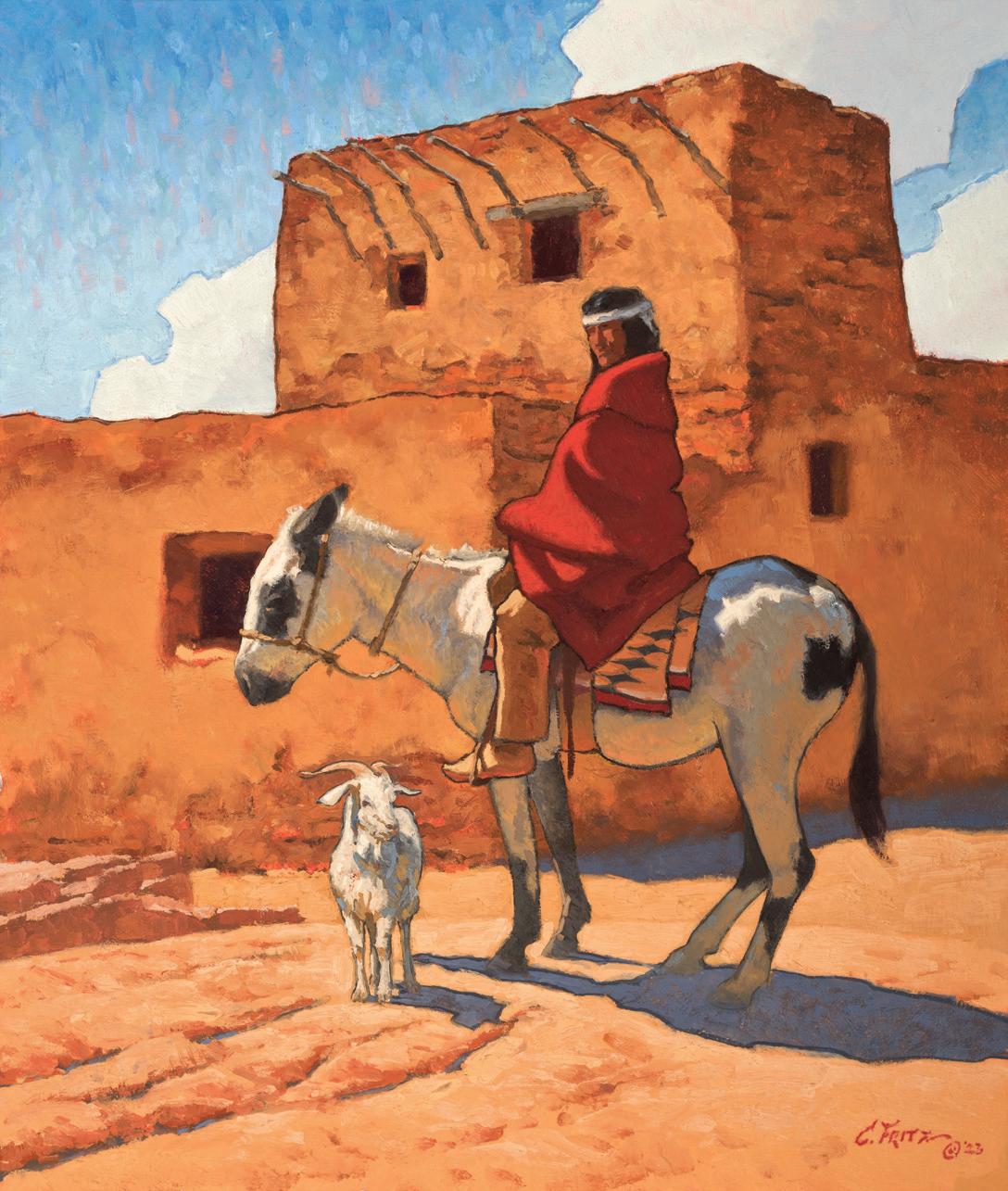

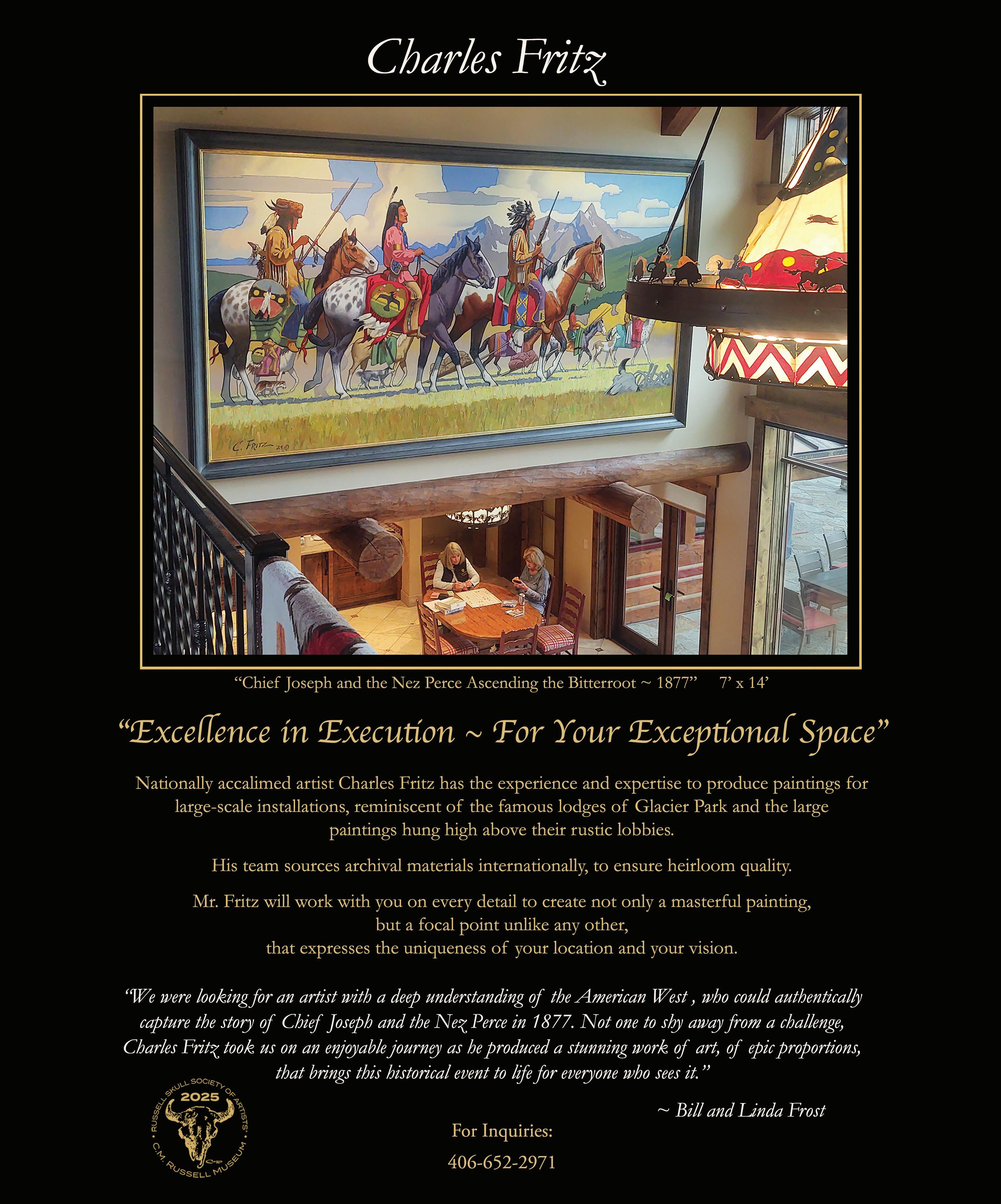

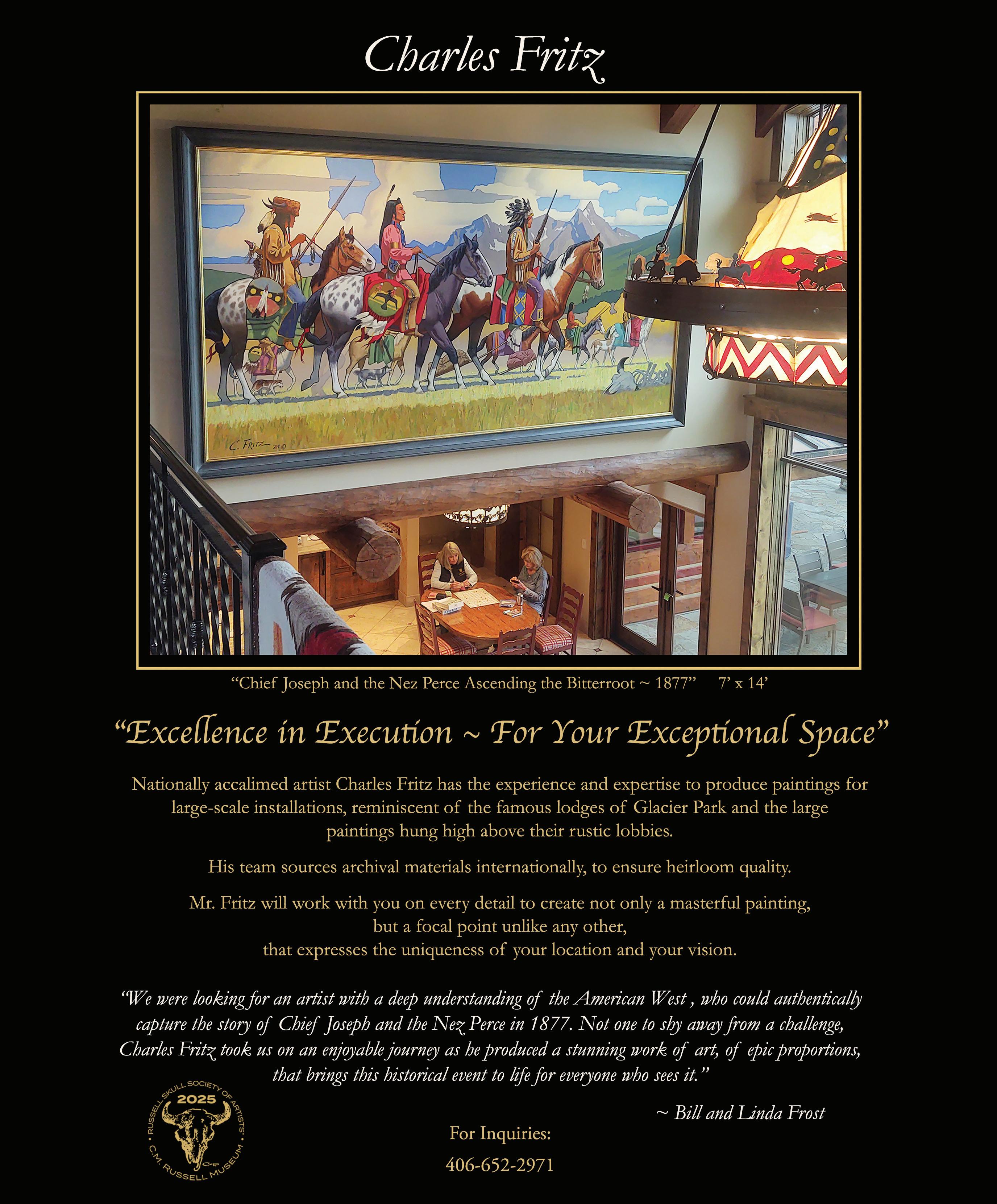

76 Artist of the West

A Quintessential Painter: Artist Charles Fritz captures Montana moments in time

Written by Halina Loft

84 Local Knowlesge

An Evolution of Art and Craft: Will Hutchinson’s knives seamlessly marry form and function

Written by Melissa Mylchreest

Photography by Nick VanHorn

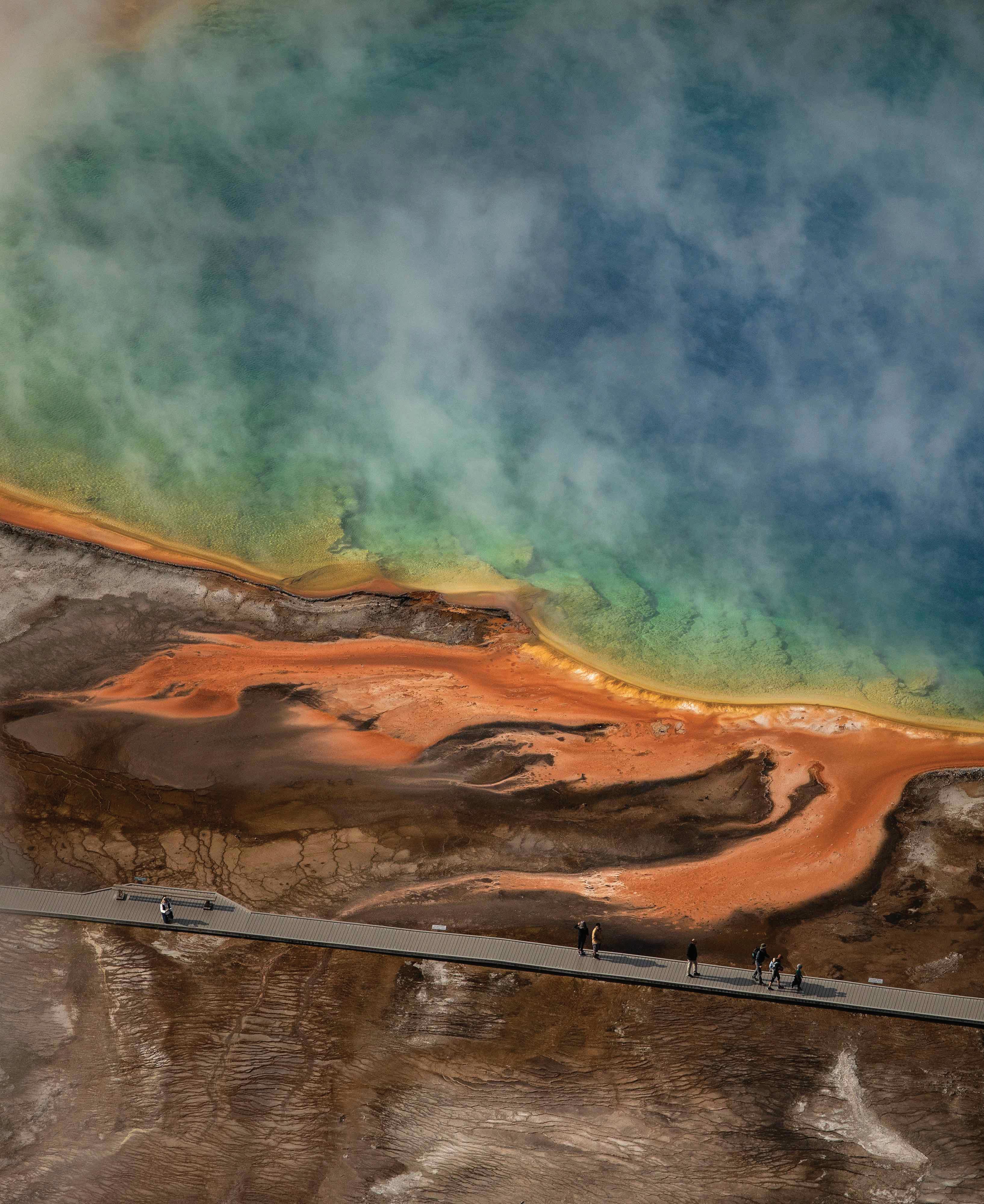

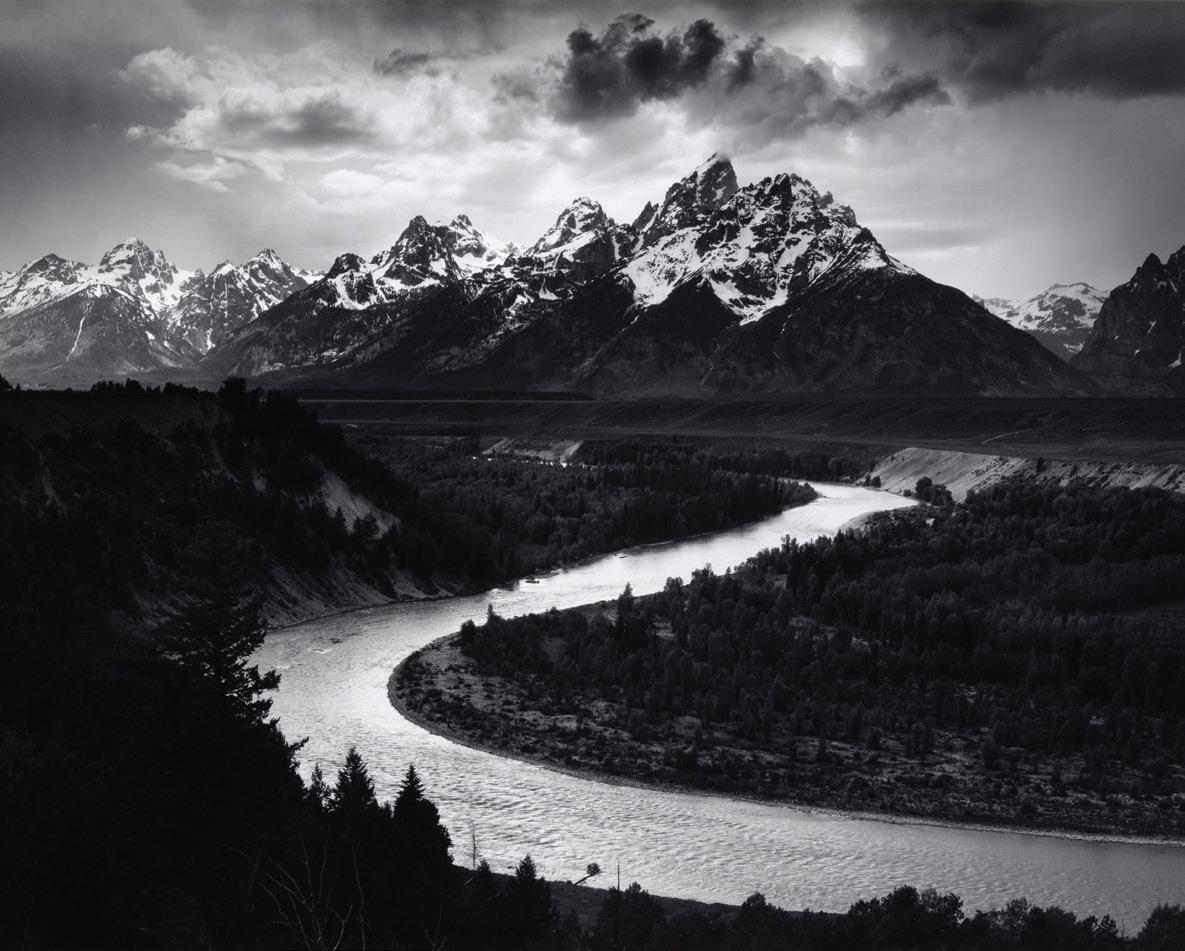

90 Images of the West

Letting Off Steam: Autumn in Yellowstone National Park

Written & Photographed by Carol Polich

160 Back 40

Sentrees

Written by John Kelly

26 From the Editor

Round Up

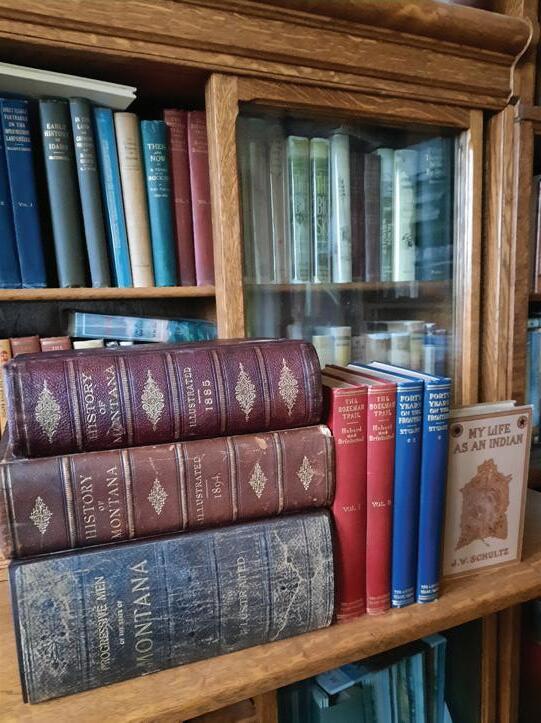

Reading the West

Contributors 158 Advertising Index

FROM TOP: From “Dining Out,” photo by Lynn Donaldson; from “Western Design,” photo by Whitney Kamman; from “Artist of the West,” painting by Charles Fritz

Volume XXXII, Number 5

Josh Warren publisher | advertising director

Jessianne Castle editor-in-chief

Jessica Bayramian Byerly associate editor

Jeanine Miller art director

Elaine Leonardi Dixon advertising design

Christine Rogel copy editor

Jared D. Swanson advertising

Stephanie Randall advertising

Owen Raisch office manager | accounting | advertising

field editors

Rick Bass, Marc Beaudin, John Clayton, Michele Corriel, Seabring Davis, Jeff Erickson, Chase Reynolds Ewald, Andrew McKean, Melissa Mylchreest, E. Donnall Thomas Jr., Carter Walker

field photographers

Lynn Donaldson, Gibeon Photography, Audrey Hall, John Juracek, Whitney Kamman, Heidi A. Long, Melanie Maganias, Jeff Moore, Karl Neumann, Janie Osborne, Ryan Turner

artists / illustrators

Jesse Greenwood, Carol Ann Morris, Bob White

BIG SKY JOURNAL, LLC

Jared D. Swanson CEO

subscriptions : 800-417-3314

www.bigskyjournal.com e-mail: bsj@bigskyjournal.com

P.O. Box 1069 Bozeman, MT 59771 tel 406-586-2712 fax 406-586-2986

Printed in the U.S.A. © 2025 by Big Sky Journal, LLC

Our passion is helping travelers discover new adventures.

As Big Sky’s largest locally owned vacation rental company, we help thousands of travelers every year experience big-time adventure with a small-town touch. Featuring a wide selection of high-end properties and the most personalized service in the area, we ensure each guest experience is free of hassle and full of memories. Give us a call or visit our website today and discover a better way to vacation.

406-995-2299

info@twopines.com

twopines.com

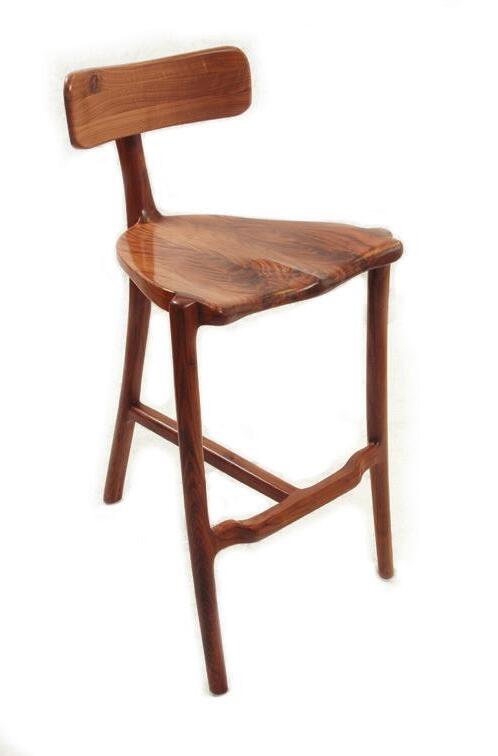

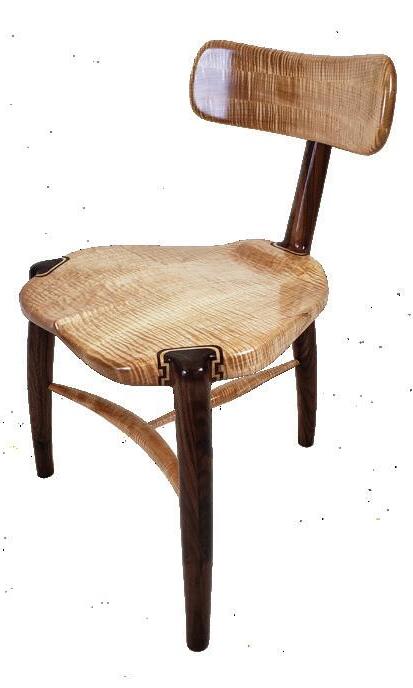

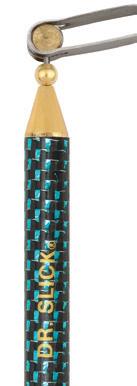

WATCH THE DOVETAIL STORY

| JESSIANNE CASTLE

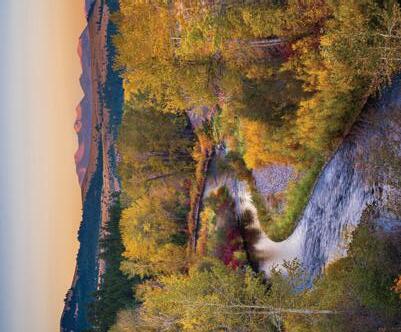

MY HOME OPENS broadly to the south with an oversized glass door leading to a covered patio from which a panorama unfolds. Beginning in the east, a distant ridgeline traces the division of our valley from a nearby chain of lakes while foreground hills sprawl to the west, abutting a set of peaks that are trumped by a retired lookout tower. Our horse pasture rolls through these foothills; a seasonal creek and pond are nestled at the lowest point, and a wave of green-hued forest emerges as the hills rise, swelling to a crescendo where land meets sky.

Lodgepole pine dominate the view, curtsying their branched skirts in moss and emerald tones. Among them stand the larch. These towering giants send archaic limbs outward as whirls and burls interrupt their corrugated auburn skins. Their foliage, once the tender green of spring, slowly fades as mornings dawn increasingly cooler, as summer fades to fall.

By October, the larch needles have become ocher, punctuated by the shadows of still evergreen pines. Beautiful in their form and presence, the larch are one of the season’s gifts. Beyond their glory, the trees are a signal of the coming cold. Soon, needles will fall to the frozen ground; the trees will slumber, their petrified limbs still and stark amid the snow.

As the trees and vegetation respond to the region’s weather patterns, so too do its inhabitants. Animals lean into their migrations, some caching and consuming more food. For humans, it’s a time of turning inward: we seek the warmth of the fire, sip drinks to comfort the heart. The stories herein recognize this shift in routine, celebrating those small moments of pause.

During this season of change, may we be reminded of the cycles of time. This moment lingers for but a short while.

MONTANA

LOLO RANCH LOLO,

1,981± acres just south of Missoula. A mix of timber, foothills, irrigated meadows and pasture. A 5,000±-square foot owner’s residence and adjacent to public land. Existing infrastructure for shared ranch lifestyle community development.

$24,000,000

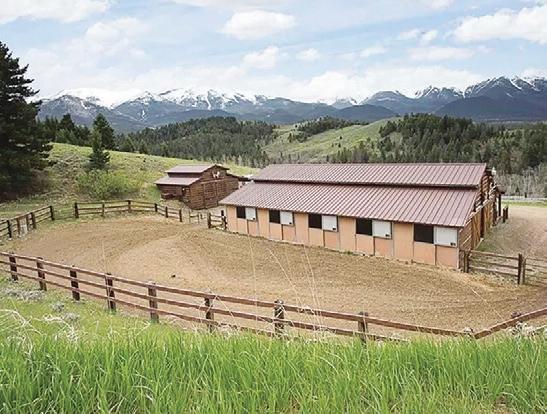

THE FORT RANCH ON THE YELLOWSTONE BIG TIMBER, MONTANA

Magical 141± acre Yellowstone River ranch retreat with custom home and guest apartment overlooking the river toward snowcapped peaks. A superb horse property with irrigated meadows, barn, and outdoor riding arena.

$6,200,000

MUDDY CREEK RANCH

WILSALL, MONTANA

Beautiful and water-rich 2,217± acre mountain valley ranch north of Livingston and Bozeman. Productive working ranch with abundant wildlife in a highly soughtafter community. Also offered as separate 814± and 1,404± acre units.

REDCUED TO $15,000,000

CREEK HOMESTEAD

WILSALL, MONTANA

116± acres in the scenic Shields River Valley with mountain views, restored Victorian home, barn with loft apartment, ponds, springs, and abundant wildlife. Ideal equestrian setup with proximity to Bozeman and Livingston.

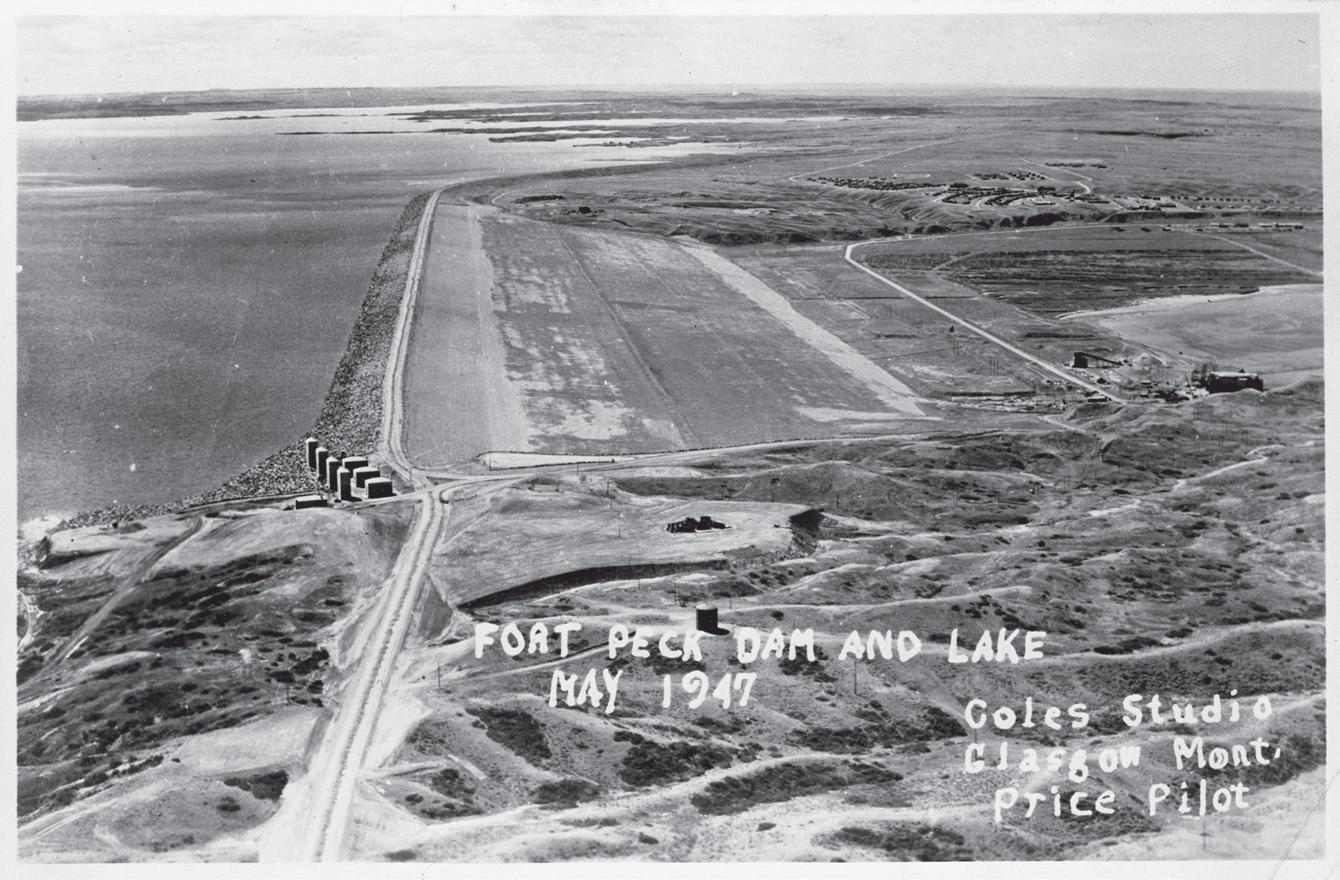

$3,900,000

Set in the shadows of the Bitterroot Mountains lies a near-perfect 155± acre assemblage of irrigated pasture and forested hillsides with a complete set of operational and residential improvements minutes from Darby.

$7,950,000

TRINITY RANCH

ABSAROKEE, MONTANA

158± acre property with 1,500± feet of Stillwater River frontage and Beartooth Mountain views. Less than ten minutes upstream of Columbus, the property includes a 1,500± square foot main home, outbuildings, and irrigated hay ground.

REDUCED TO $3,490,000

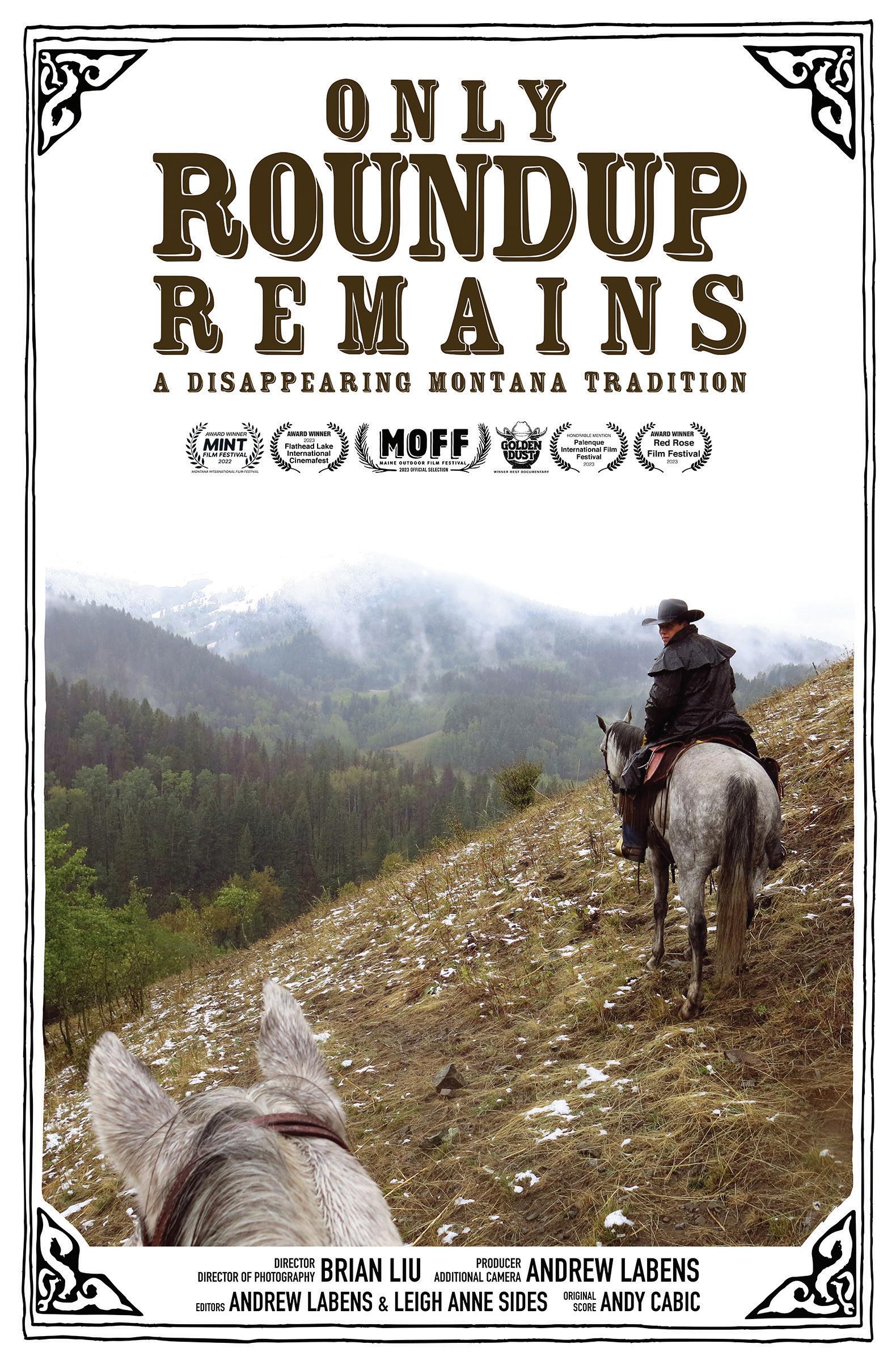

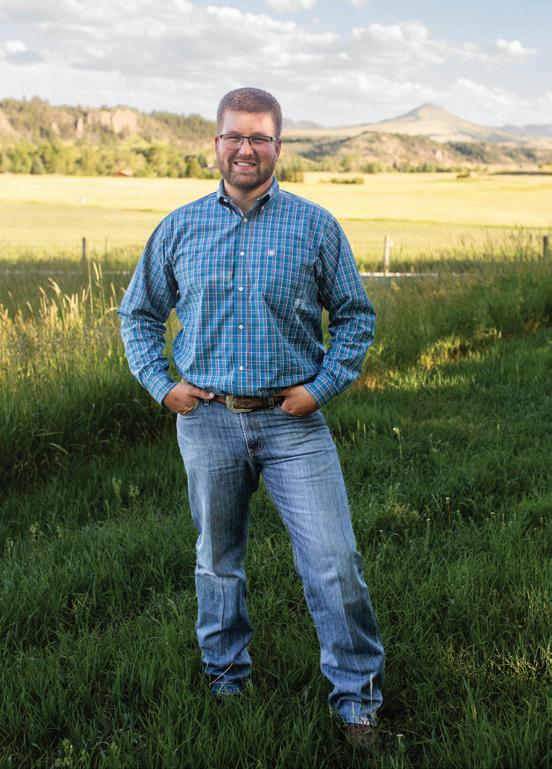

Documentary provides a glimpse into a family’s ranching lifestyle

WRITTEN BY BSJ STAFF

EACH AUTUMN, AS cooler weather brings color to leaves and deposits dustings of snow in the mountains, a group of cowboys heads into central Montana’s Highwood Mountains on horseback to gather the area ranchers’ cows and bring them home. After spending the summer turned out, grazing on mountain grasses, the cows, their calves, and the bulls are returned to the ranches’ pastures where they’ll brave the region’s cold.

“The Highwood Cattle Roundup has been happening exactly this same way since 1912, with a small group of regional cowboys passing the torch from generation to generation,” says director Brian Liu, who worked with producer Andrew Labens to create a film that memorializes this Western tradition. Only Roundup Remains provides an intimate glimpse into the lifestyle of a generational ranching family through the perspective of an aging father, his two sons, and their extended family.

For much of his childhood, Labens, who partly grew up in Montana, heard mystical stories and legends of the roundup from his cowboy neighbors, which eventually sparked the idea to document this disappearing tradition.

Now available to stream on Amazon Prime, the film is an award recipient from the Montana International Film Festival, Flathead Lake International Cinemafest, New West Film Fest, and DC Independent Film Festival, among others.

Montana 250th Commission celebrates the nation’s upcoming 250th birthday

WRITTEN BY BSJ STAFF

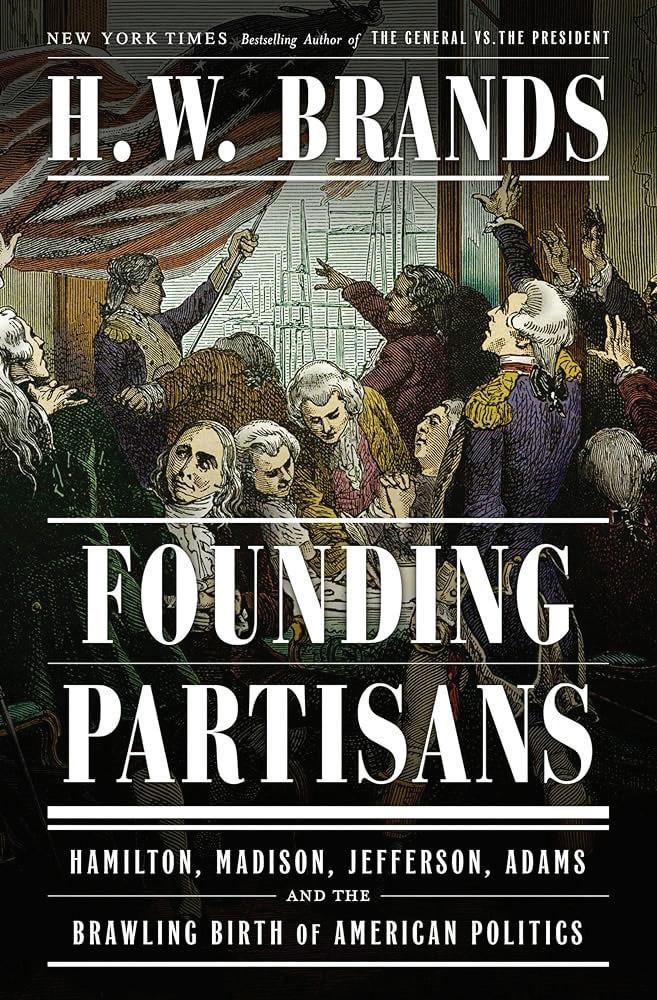

THE MONTANA 250TH Commission, created in 2023 to coordinate statewide efforts to commemorate the United States’ semiquincentennial, recently launched Montana Reads: The Treasure State’s Book Club, a monthly online book discussion group that will cover topics related to United States, Montana, and Indigenous history. Each month, a member of the Montana 250th Commission will lead a presentation and discussion on a selected book that explores aspects of our shared history, from the Founding Fathers to Montana statesmen and stateswomen, cultural traditions to amazing innovations. Montanans are encouraged to participate and, when possible, read the book in advance.

After an inaugural kickoff featuring author Stephen Fried and his book on groundbreaking physi-

cian Dr. Benjamin Rush and a subsequent discussion on Garrett Graff’s The Only Plane in the Sky: An Oral History of 9/11, the commission is slated to host historians Marc Johnson and H.W. Brands this fall. On October 9, participants can join a discussion of Johnson’s Mansfield and Dirksen: Bipartisan Giants of the Senate, and on November 13, Montana Reads will review Brands’ Founding Partisans: Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, Adams, and the Brawling Birth of American Politics

All Montana Reads events will be held on Zoom on the second Thursday of each month, from 6:30 to 7:30 p.m. To register for events, visit mths. mt.gov/education/index1. For more information, email laura.marsh@mt.gov.

WRITTEN BY BSJ STAFF

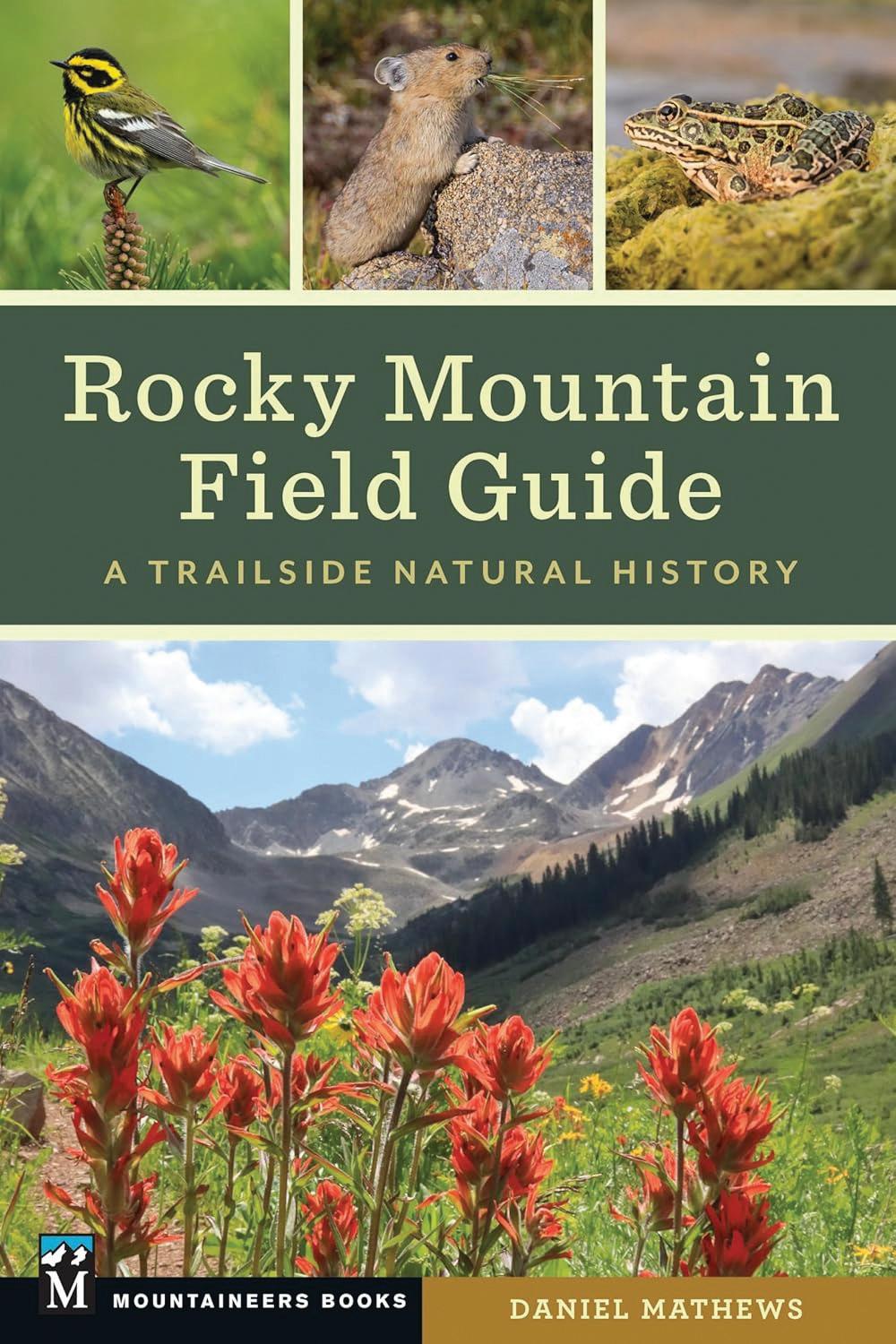

WRITTEN BY DANIEL MATHEWS

In Rocky Mountain Field Guide: A Trailside Natural History, naturalist and writer Daniel Mathews offers a comprehensive guide to the farranging flora, fauna, topography, and habitats that define the Rockies, from Glacier National Park in Montana to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico. A portable essential for hikers, campers, or fellow naturalists, Mathews’ book provides welcome insight into the region’s natural history that’s immersive, accessible, and enjoyable to read.

$32.95 | 576 pages | October 2024 Mountaineers Books

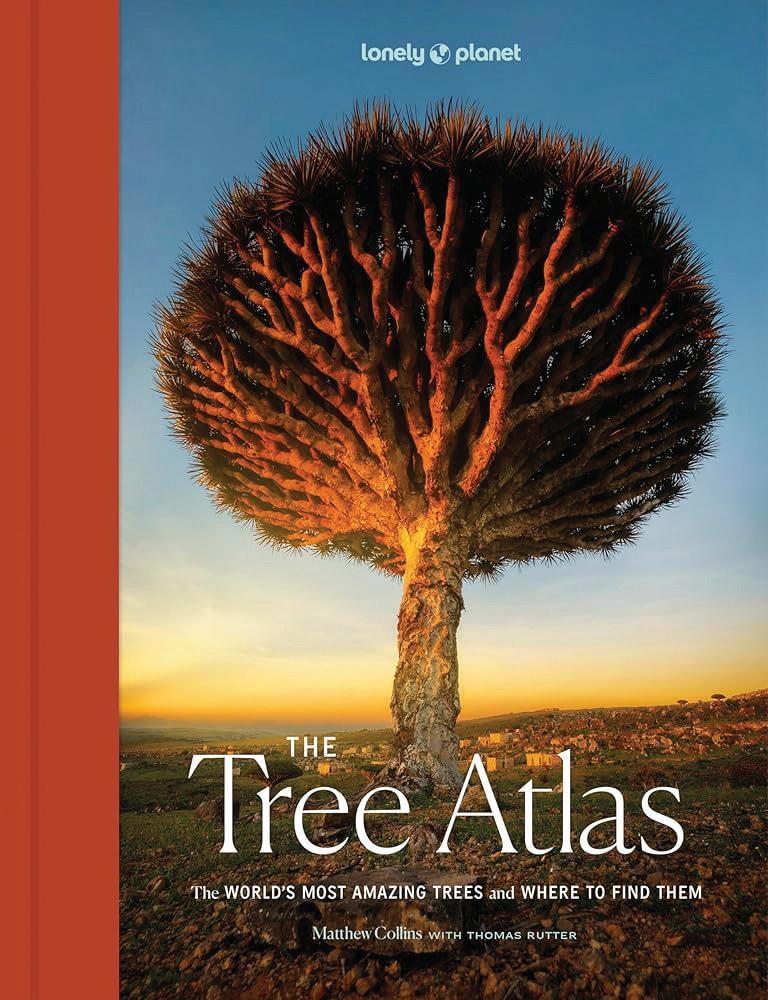

WRITTEN BY MATTHEW COLLINS WITH THOMAS RUTTER

A beautiful gift for dendrophiles (tree lovers) of every age, The Tree Atlas presents 50 of the world’s most spectacular specimens. This collectible tome incorporates stunning photography, unique illustrations by Holly Exley, and insightful sidebars by London Garden Museum’s head gardener, Matthew Collins, and professional gardener and writer Thomas Rutter. The book also offers practical advice about when and where to see the featured varietals, how to identify them in the wild, and why they hold such an important place in the health of ecosystems spanning the globe.

$50 | 240 pages | October 2024 Lonely Planet

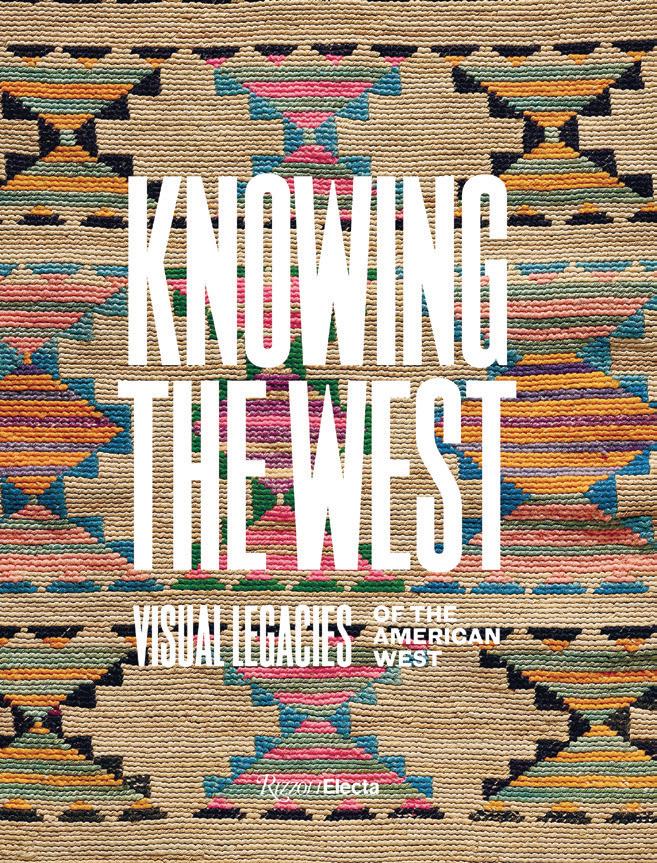

EDITED BY MINDY N. BESAW AND JAMI C. POWELL

Knowing the West: Visual Legacies of the American West , a comprehensive survey of art and culture from the late 18th to early 20th centuries, strikes an insightful visual and verbal dialogue between diverse perspectives, challenging readers to consider the impact of history and place on artistic expression. Highlighting 35 distinct Native American nations, featuring more than 120 works in a variety of mediums from Native and nonNative artists, and offering supporting texts from leading scholars, Knowing the Wes t provides an intriguing new Native-centered exploration of Western art history.

$75 | 288 pages | September 2024

Rizzoli Electa

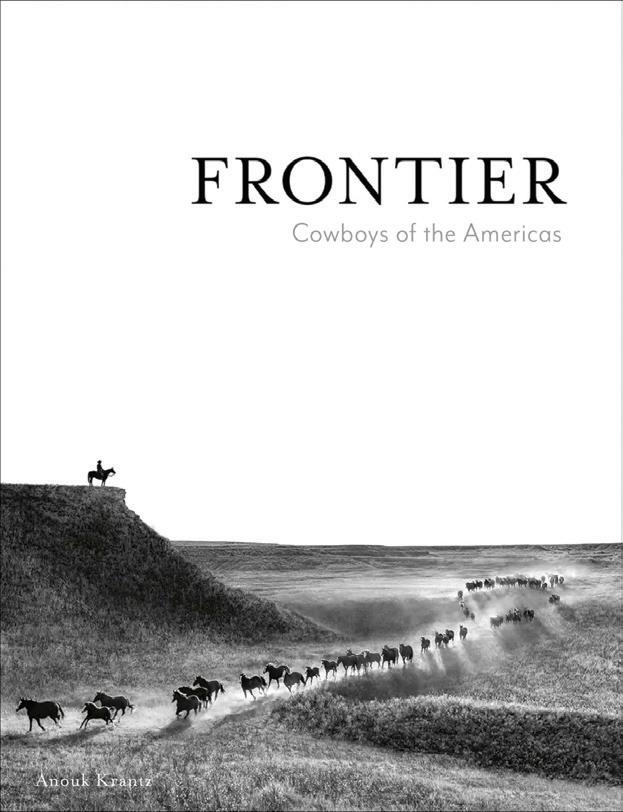

WRITTEN BY ANOUK MASSON KRANTZ WITH FORWORD BY BERNIE TAUPIN

In her first work spanning both American continents, Anouk Masson Krantz captures intimate portraits of North American cowboys, Central American vaqueros, South American gauchos, and the expansive landscapes they call home. In a compilation of new largescale black-and-white photographs, she chronicles her time spent at ranches and rodeos across North and South America, augmenting an already remarkable body of work — including Ranchland (2022) and American Cowboys (2021), among others — with a rare and stunning glimpse into the timeless resilience of modern working cowboys.

“There’s an honesty and integrity in these images that parlays all the elements of what it means to exist outside the boundaries of conformity and confinement,” says English lyricist and visual artist Bernie Taupin, who wrote the book’s forward. He adds that the book is “a true testament to the men and women who are the anvil on which America’s backbone was forged.”

$85 | 360 pages | November 2024 | The Images Publishing Group

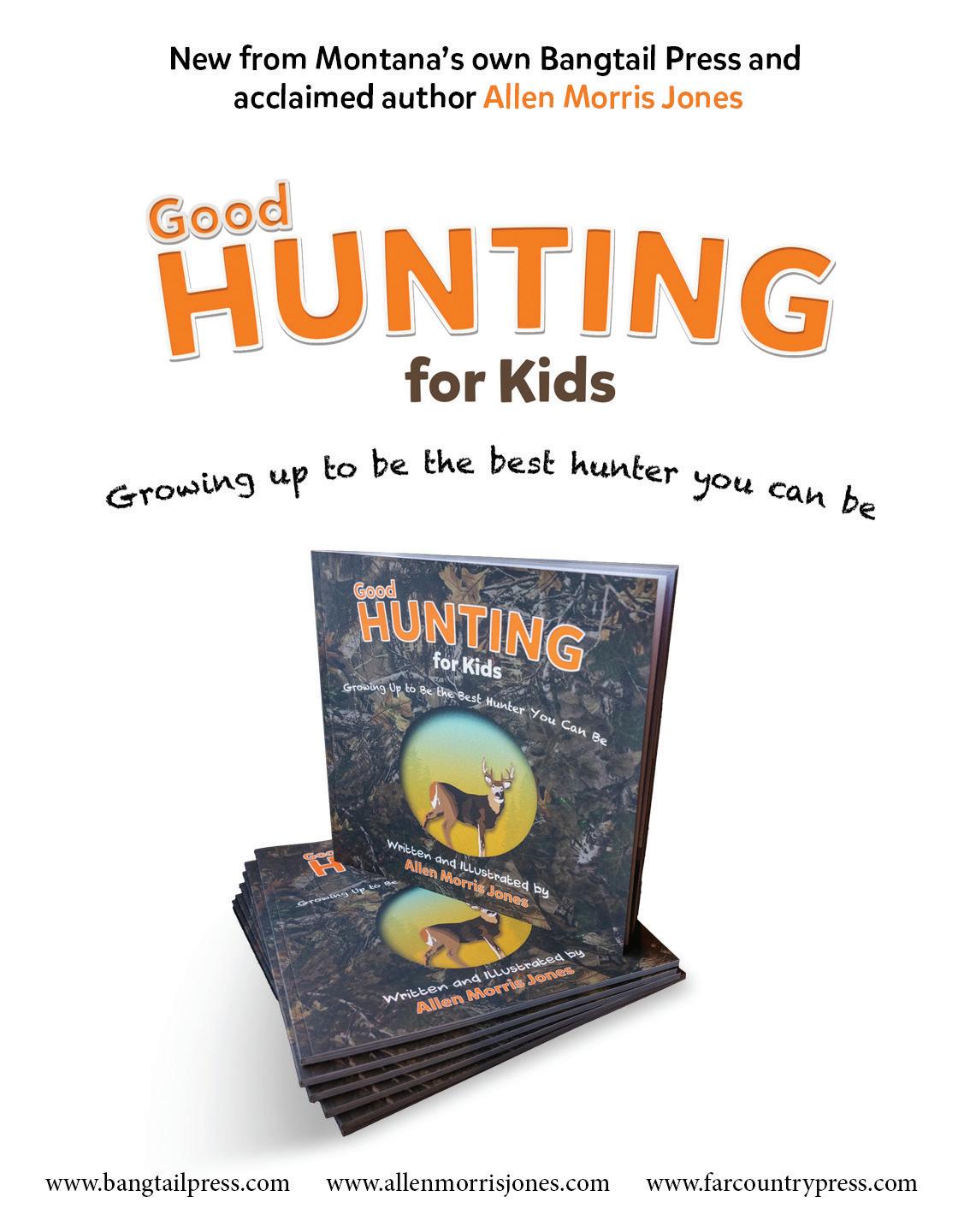

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY ALLEN

MORRIS JONES

Bozeman, Montana author and poet Allen Morris Jones adds another children’s book to his repository with Good Hunting for Kids: Growing Up to Be the Best Hunter You Can Be. Jones explains core principles of hunting, identifies safe hunting practices, and describes a variety of birds and animals hunted in the Northern Rockies. As a celebration of the sport — which teaches patience, stamina, how nature works, and where your food comes from, to name a few — this children’s book explores what it truly means to be a good hunter.

$14.95 | 48 pages | December 2024 | Bangtail Press

WRITTEN BY JESSICA BAYRAMIAN BYERLY

IN A WORLD where outdoor adventuring often feels intimidating, Shyanne Orvis is redefining the narrative one cast at a time. As a guide, conservationist, and passionate advocate for women in fly fishing, Orvis has built a reputation defined not just by her skill on the water but also by her unassuming authenticity and commitment to building community. Whether she’s navigating rapids or sharing her story, she brings a fresh, inclusive perspective to a traditionally male-dominated space, offering the invitation to adventure not just for some, but for all.

Here, Orvis describes the formative power of nature, the metamorphosis inherent in motherhood, and the empowerment that becomes possible when we seek out what lights us up and share it, perpetually, with the world.

BIG SKY JOURNAL: You have a deeply personal connection to fly fishing and the outdoors. How did early experiences shape your journey in a career defined by that connection? What have been the greatest challenges and rewards in following your passion?

SHYANNE ORVIS: I spent the entirety of my summers as a kid either on a fishing boat trolling for salmon and steelhead or at the end of a dock with a Barbie rod in one hand and a leech in the other. I found comfort in those early mornings on the water in northern Michigan: When everything else seemed like chaos during my childhood, fishing was the one constant. It gave me a connection to the water and the outdoors, and as I got older, I found so much purpose in picking up fishing again.

I spontaneously moved to Colorado at 18 and was immediately immersed in the world of fly fishing. It wasn’t like the fishing I had known as a little girl, and while I had a little exposure to it in Michigan, targeting

trout on the fly in the mountains was a vastly different experience. After sight fishing a brown trout on the upper Roaring Fork River, I was hooked. Over the following years, I learned as much as I could by spending every free moment on the river. At the time, I had no idea what my future had in store, but I knew I wanted fly fishing to be an essential part of it. Eleven years later, and I feel that I’ve just scratched the surface of the potential opportunities within this space.

Guiding is a critical stepping stone in my story. While catching fish is an important part of the experience, the trips I offer provide so much more than that. Guiding has allowed me to connect with people all over the world, to hear their stories and learn from them. It’s allowed me to share meaningful, unique experiences with them while giving them space on the river to reconnect with themselves and nature.

As I reflect on my journey, I now understand that there will always be challenges for anyone seeking success in their chosen field. Just as in life, those challenges can make or break you — it’s how you decide to navigate the hurdles that ultimately shapes who you are and how you move through the world.

BSJ: As a strong advocate for women in fly fishing, how have you seen the industry react to women’s presence over the years? Are you see -

ing numbers increase or decrease, and is continued work necessary toward cultivating inclusivity for all?

ORVIS: In the past decade, I’ve seen tremendous growth in female angling. There’s definitely been a positive shift in recent years, and it’s truly been so inspiring to watch as more women step into guiding positions, host travel operations, and open fly shops and lodges. I think we have a long way to go, but I’m in awe watching women pave their own path in this industry. It gives me hope that we’re moving in the right direction.

BSJ: What does a perfect day on the water look like for you?

ORVIS: I’d like to think I try to find beauty in every river outing. There’s no “perfect” day on the water because every experience is so vastly different and rewarding in its own way. Whether it’s a hard day on the river and a few tough lessons that come with it, or a great day of guiding and connecting with new people, or perhaps hiking into the backcountry with my 3-year-old, it’s all equally fulfilling. There’s beauty in all of the moments, and finding balance between parenting, my career as a guide, and personal time on the water continues to fill my cup.

BSJ: What prompted the writing of your children’s book, To the River We Go, and what are your hopes for its impact?

ORVIS: Writing To the River We Go was kind of a spontaneous decision. I was inspired by a 12-hour road trip during which I sat in the backseat with my 7-month-old, attempting to entertain him in any way I could. While scouring the internet for children’s books on fly fishing, I found that all the ones I liked were geared toward older kids. I wanted something that shared the entire process of gearing up for the river, and selfishly, I wanted to include key terms so that my son would later be able to point out things like waders and fly rods. At 18 months old, he was doing exactly that. He could name various fly patterns and all the gear, and when we spent time on the river, he understood the process of it all. I hope that this book helps foster curiosity for exploration and the outdoors. If we want to preserve and protect our resources, it starts with the next generation caring about them.

BSJ: How did motherhood change your relationship with nature, and what lessons learned from fishing, the outdoors, and a life defined by both are you most focused on teaching your young son?

ORVIS: Motherhood completely changed my perspective on everything. It transformed the way I view fly fishing. While I’ll never say no to targeting big fish, I’ve found it to be less of a priority since becoming a mother. Now, it’s more about the

journey on the river. Including my son in my adventures has forced me to slow down, appreciate my surroundings, and look at everything from his perspective. Most of our outings aren’t exactly productive fishing. Instead, we spend our time flipping over rocks and identifying bugs. We spot fish, and he excitedly casts the fly rod to the point of tangles. The less pressure I put on the actual fishing, the more he seems to light up about it, and the days when we do catch fish — whether he’s got the rod in hand or he’s in a kid carrier on my back — are beyond rewarding. I can only hope these little outings become core memories for him, that they shape the way he views the outdoors, and that as he gets older, nature provides him with the same solitude and comfort I’ve found.

BSJ: What advice would you give to someone looking to carve out their own path in the outdoor industry?

ORVIS: If I could give any advice to those pursuing a career in the outdoor industry, it would be to let your heart lead the way. Whatever it is that you’re feeling called to pursue, believe in it so wholeheartedly that nothing can deter you from success. And if you haven’t found it yet, search for the very thing that lights you up, and build your entire life around it. I’ve found that most outdoor industries are small, niche communities, and it takes time for folks who have been around for a long time to appreciate new ideas. Keep showing up, find people who believe in you, and be the change you wish to see.

WRITTEN BY BSJ STAFF

MONTANA FISH, WILDLIFE & Parks (MT FWP) biologists are collecting wings from hunter-harvested mountain grouse, including dusky/blue, spruce, and ruffed, across Region 3, which encompasses the southwest portion of the state. The biologists will use the wings to identify birds by species and determine whether they are juveniles or adults in efforts to monitor overall juvenile recruitment across the populations.

Wing collection barrels are located at the MT FWP Region 3 headquarters in Bozeman, Townsend-area field office, Livingston-area field office, Helena-area resource office, Butte-area resource office, and Dillon-area field office. The latter two are also collecting sage grouse, sharp-tailed grouse, and Hungarian partridge wings.

Hunters are invited to place one wing from each bird harvested within Region 3 throughout the mountain grouse hunting season, which runs September 1, 2025, to January 1, 2026. Wings can also be turned in to area wildlife staff or game wardens.

For more information, contact Bozeman-based wildlife biologist Claire Gower at cgower@mt.gov or (406) 624-1663.

422

424

Cayuse Cabin. 4-br, 4-ba log home at Stock Farm is well-suited for a lg group with its separate living spaces. Each includes 2 br, a private kitchen, & 2 ba. The common area, great room, is perfect for gatherings. Plenty of privacy, Sapphire & Bitterroot Mountain views. Furnished & close to the members-only clubhouse.

MLS 30054927

$3,150,000

Experience the ultimate Montana lifestyle with this exceptional, established 50acre legacy ranch! The Fred Burr Canyon Ranch offers a 6,448 square foot home, 2 guest cabins, private ponds, barns, and easy recreation access.

MLS 30009952

$4,790,000

Stunning 5-bedroom home built with thoughtful, strategic craftsmanship. 7,800+ square feet with panoramic views. Convenient to the Stock Farm Golf & Sporting Community and Hamilton Golf Course! Bring all offers.

MLS 30016145

$2,950,000

Stunning 4 bedrooms, 4.5 bath home with a stable/ barn/shop and fenced pasture on 5.36 acres in the lovely Arrow Hill community. The large primary suite features a private sitting area and luxurious spa bath!

MLS 30051384

$2,250,000

This Rocky Mountain log home at Stock Farm Golf & Sporting Club isn’t just a home, it’s a lifestyle! 4 bedrooms, 4 baths, 3,094+/square feet. Incredible log and stone accents throughout. Stock Farm membership not included with purchase.

MLS 30051378

$3,100,000

Well-maintained ranch property. Amazing views, creek, and horse ready! Nice 3 bedroom, 4 bath home near the Calf Creek Elk Ranch and countless outdoor recreation opportunities.

MLS 30050833

$2,250,000

Discover your own slice of Montana paradise with this lovely 5.083 acre parcel located alogn the pristine waters of the Bitterroot River. 20 gpm well, power, and a new septic permit is in place! Close to town and amenities.

MLS 30039161

$549,000

Beautiful mountain home with incredible views! This 3 bedrooms, 5 baths, 4,252 SF home offers 2 additional bonus rooms, a detached guest house, & large shop on 30.94 acres.

MLS 30051777

$2,980,000

CARTER WALKER

Bodhi

Field Kitchen Restaurant in Bozeman, Montana, everything is local and local is everything

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LYNN DONALDSON

THIS HAS NEVER happened to me at a restaurant before. I’m seated at a picnic table. Before me, rows of vegetables and herbs unfurl themselves, pushing into the green foothills of the Gallatin Range. The light is golden and coming in slantwise between steel-gray storm clouds. Behind me, a creek tumbles over itself, making its own music. There is hickory smoke from the hand-built stove and the smell of meat on a fire. And right here at the table, Tia, who is our server for the night, points at the colorful Hippie Board she’s just set down and tells us what she harvested that day: “the grilled lettuce, the cucumbers, those shishito peppers, and the beans,” she says, delighted. “Oh, and all the herbs, that dill, and those beautiful little flowers. We love edible flowers here.”

I take a sip from the Mason jar she’s set before me — a spicy margarita with bitters made onsite from jalapeños grown within my sight range — and feel grateful for this cool night, for the friends around our table, and the way that even now, even here, we can still find a way to celebrate the simple wonder of things that grow and the beauty that can attend every encounter with the natural world.

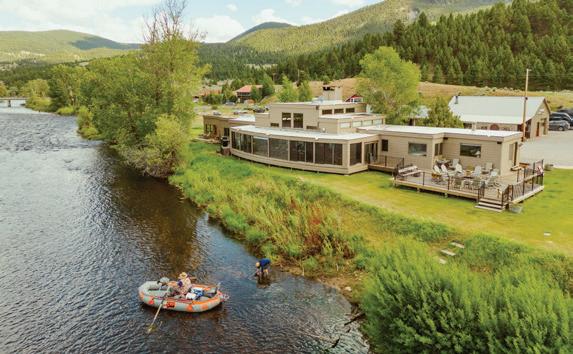

The Field Kitchen Restaurant is the truest manifestation possible of a farm-to-table restaurant, and is a part of Bodhi Farms, a boutique eco-resort just south of Bozeman, Montana, along

Cottonwood Creek. Founded, owned, and managed by Tanya and Rayner Smith — natives of Austin, Texas and longtime residents of Gallatin Valley — Bodhi Farms offers accommodations in nine Nordic tipis; spa and wellness amenities, including yoga taught by Tanya; a range of year-round outdoor activities and adventures; private and community events, including a kids’ summer camp that makes me want to raise my daughters all over again; an organic permaculture farm; and their unmatched wild-game farm-to-table restaurant.

When I ask, gobsmacked, how they do it all, Rayner doesn’t miss a beat. When you’re doing

what you love, he says, “it doesn’t feel like work.”

He describes how he and Tanya have always worked together, as “couplepreneurs,” and that this is the most fun they’ve ever had. They are gardeners and hunters, he says. They love to entertain and cook out. They believe in wellness practices, such as yoga. “This place is just a reflection of the things we get excited about,” Rayner says.

Everything Tia sets down on our table is easy to get excited about. Between the four of us, we order the aforementioned Hippie Board, with its array of fresh veggies and whipped tofu tahini; gardenfresh gazpacho; bison sliders with blue cheese and

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

These gentle Kunekune pigs — Larry, Curly, and Moe — are not only adorable inhabitants of Bodhi Farms, but they serve the important ecological functions of enhancing soil health, promoting biodiversity, and controlling invasive species. • Farmer Addy oversees the self-governed organic farm, growing vegetables, annual and perennial herbs and flowers, trees, bushes, and shrubs. Here, she’s harvesting cucumbers.

• Addy holds a basket of freshly harvested red-leaf head lettuce, kale, Swiss chard, and cucumbers.

• Chef Mark McMann works outside at the Field Kitchen’s wood-fired oven.

bacon-onion jam; beet salad with local goat cheese and steak; wood-roasted pheasant wreathed in flowers and herbs; garden pasta served in a giant cast-iron skillet; and the nightly special, a bavette steak with fingerling potatoes, Greek-style beans, and a chimichurri that could only come from a garden.

Chef Mark McMann briefly leaves his post at the outdoor kitchen to show me around the property. He points out the spotted Kunekune piglets and new trees that will someday become a walkable, edible forest. We walk past the chickens and, of course, the gardens. He starts each day by practicing gratitude, and lets me in on it as he extolls the Bodhi Farms’ staff by name — from the farm team to the hospitality, kitchen, and culinary crews — describing how it feels to work in such a place, with a hand-built outdoor kitchen surrounded by farmland, animals, and people he obviously adores. “Together, these elements create an environment where appreciation isn’t just practiced, it’s lived every day,” he says. I assure him we could taste it in his dishes.

What surprises me a little is when I ask McMann how he wants the dining experience at the Field Kitchen to differ from the other high-end restaurants where he’s been a chef, most recently The Montage in Big Sky. “I don’t want it to differ at all,” he says. “The goal is the same everywhere: Everyone deserves good food, good drinks, and good hospitality. It’s quite simple. No one leaves unhappy. No one leaves hungry.”

By Bodhi Farms’ Field Kitchen Restaurant

Squash croquettes fulfill all the comfort needs of fall — warm, savory, and a celebration of the season’s harvest. Pictured on page 42.

2 cups butternut and/or acorn squash

1 cup breadcrumbs

3 eggs

1 tablespoon garlic powder

1 tablespoon onion powder

1 tablespoon pumpkin-spice seasoning

Salt to taste

Pepper to taste

2 ounces chevre goat cheese

For coating: all-purpose flour, 5 eggs beaten, Italian breadcrumbs

For topping: Herb aioli (recipe below), microgreens, minced parsley

Preheat a fryer to 375°F and preheat an oven to 400°.

Cut raw squash in half and discard the seeds. Roast halves in the oven on a baking sheet until cooked, approximately 45 minutes.

Once cooked, allow to cool. Peel the skin off and place the flesh in a large bowl. Add breadcrumbs, eggs, garlic powder, onion powder, pumpkin-spice seasoning, salt, and pepper. Mix together with your hands.

Divide the goat cheese into three equal-sized balls and set aside. Take the squash mixture and divide it into three portions. Wrap each portion around a goat-cheese ball, forming a baseball-sized ball with the goat cheese in the center. Place the formed balls on a sheet tray and set aside.

Next to the fryer, set up three bowls and add the flour to one,

beaten eggs to another, and Italian breadcrumbs to the last.

With gloves on, designate a dry and wet hand. Take a squash ball and roll it in the flour with your dry hand, then move it to the egg mixture and coat it with your wet hand. Transfer to the breadcrumb bowl and coat with the dry hand. Once coated, transfer the ball to the fry basket and repeat with the remaining portions. Once all three balls are coated in the mixture, fry them until golden brown.

Apply a schmear of herb aioli to a small board and place the cooked croquettes on top. Add a small dollop of additional herb aioli, microgreens, and parsley to the top of each croquette, and serve.

HERB AIOLI

MAKES 1 QUART

1 cup mayonnaise

1 small garlic clove, finely minced or grated

2 tablespoons fresh parsley, finely chopped

2 tablespoons fresh basil, finely chopped

1 teaspoon lemon juice (or more to taste)

Salt to taste

Black pepper to taste

In a small bowl, combine the mayonnaise, garlic, parsley, and basil. Stir in the lemon juice and season with salt and black pepper to taste. Blend thoroughly until smooth. Cover and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes to let the flavors develop.

By the time the sun has set and we are standing around Bodhi’s nightly fire, where people can cook s’mores or warm themselves against the night chill as we are doing, it’s clear that McMann is batting a thousand when it comes to his goal.

There are challenges, of course, with cooking and serving outside, especially in Montana, but the Smiths and McMann don’t seem phased in the least. For starters, their nightly closing requires a stricter food security policy than most restaurants, as bears and other wildlife frequent the canyon. And the weather can wreak havoc without much warning. “We can’t control it,” McMann says, explaining that sometimes the front-of-house team has to move guests under cover in minutes due to rain or wind. Another challenge, Rayner adds, is that — because of the ground they have to cover between the gardens, outdoor kitchen, and indoor kitchen — staff members have to “love getting their steps in.” Still, no one is complaining. “Working outside all summer makes my NYC chef friends very jealous,” McMann admits.

AN IMMERSIVE EXHIBITION OCTOBER 3 - JANUARY 18

3 - JANUARY 18

AN IMMERSIVE EXHIBITION

AN IMMERSIVE EXHIBITION OCTOBER 3

AN IMMERSIVE EXHIBITION

AN IMMERSIVE EXHIBITION

OCTOBER 3

OCTOBER 3

OCTOBER 3

Scan

Scan to learn more.

Scan to learn more.

Scan to learn more.

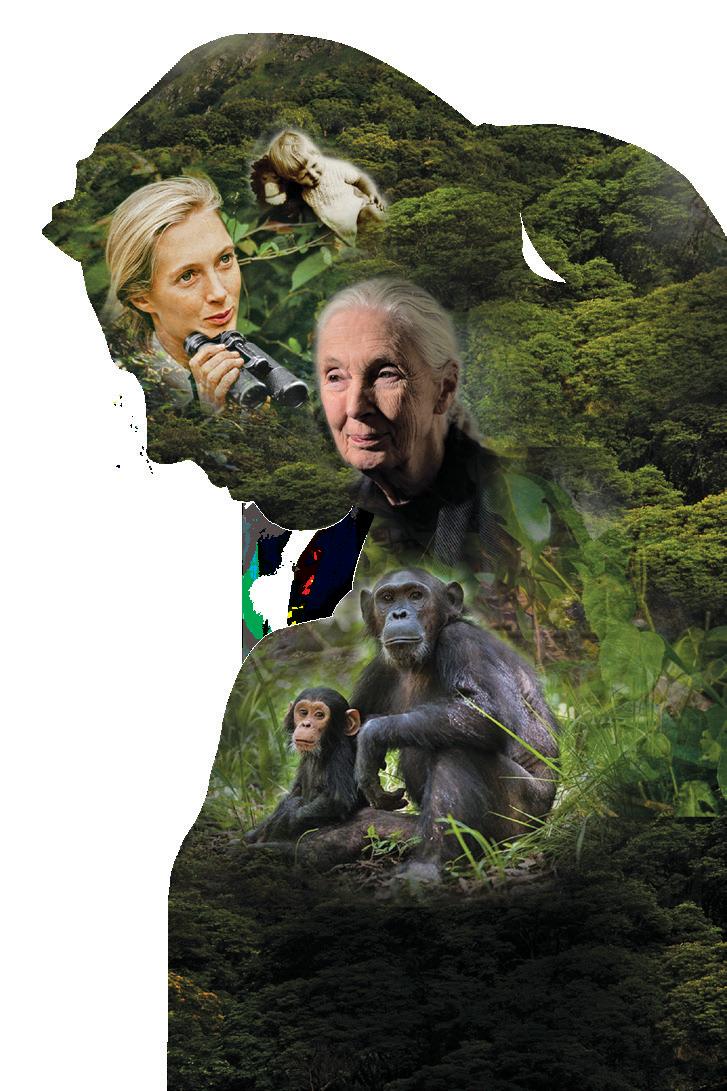

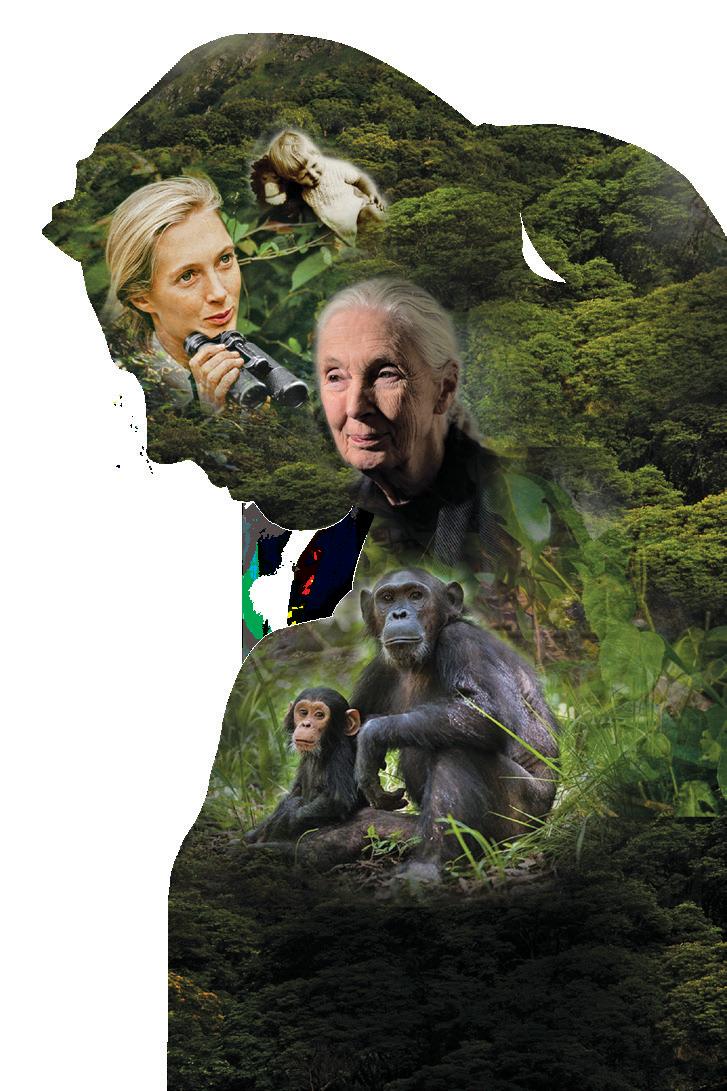

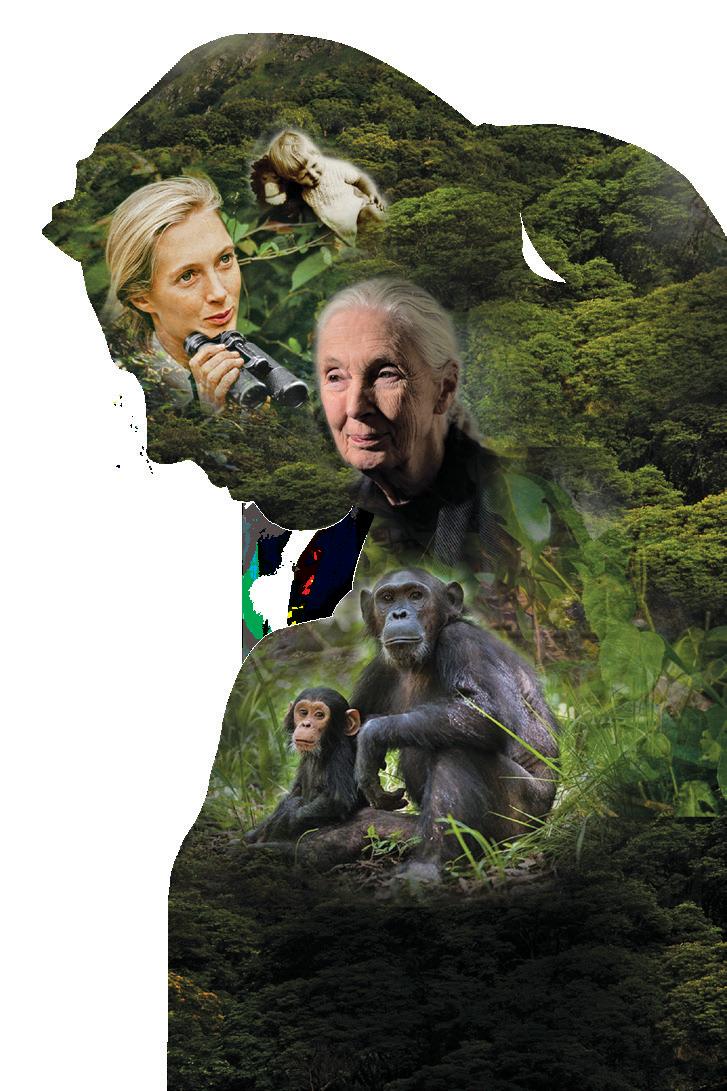

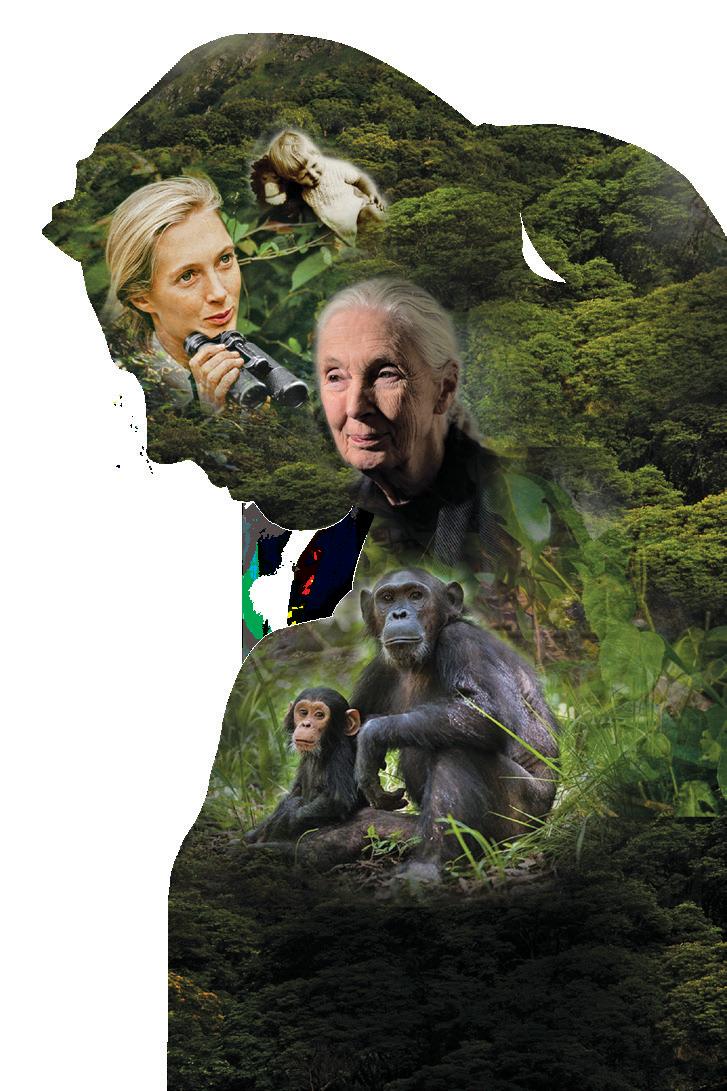

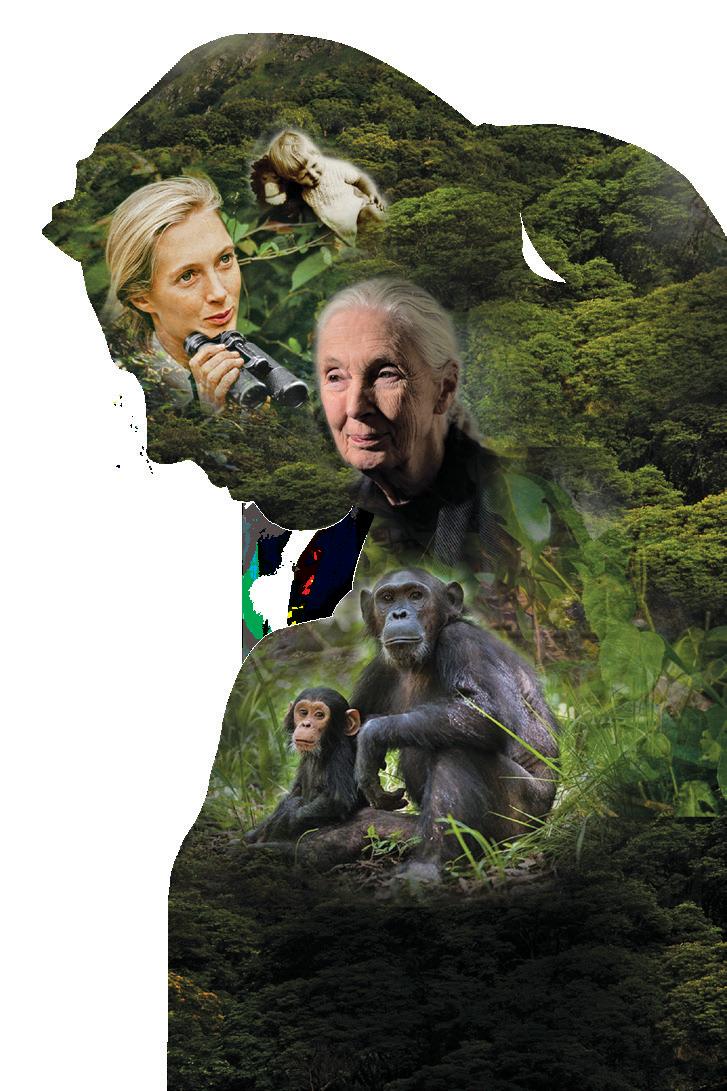

Step into the world of Dr. Jane Goodall, from her early research in Gombe to her current work as a UN Messenger of Peace. This transportive, multimedia exhibition inspires you to follow her lead and discover how you can make a positive impact.

Step into the world of Dr. Jane Goodall, from her early research in Gombe to her current work as a UN Messenger of Peace. This transportive, multimedia exhibition inspires you to follow her lead and discover how you can make a positive impact.

Step into the world of Dr. Jane Goodall, from her early research in Gombe to her current work as a UN Messenger of Peace. This transportive, multimedia exhibition inspires you to follow her lead and discover how you can make a positive impact.

An exhibition organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society in partnership with the Jane Goodall Institute.

Step into the world of Dr. Jane Goodall, from her early research in Gombe to her current work as a UN Messenger of Peace. This transportive, multimedia exhibition inspires you to follow her lead and discover how you can make a positive impact.

An exhibition organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society in partnership with the Jane Goodall Institute.

Step into the world of Dr. Jane Goodall, from her early research in Gombe to her current work as a UN Messenger of Peace. This transportive, multimedia exhibition inspires you to follow her lead and discover how you can make a positive impact.

An exhibition organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society in partnership with the Jane Goodall Institute.

Step into the world of Dr. Jane Goodall, from her early research in Gombe to her current work as a UN Messenger of Peace. This transportive, multimedia exhibition inspires you to follow her lead and discover how you can make a positive impact.

An exhibition organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society in partnership with the Jane Goodall Institute.

An exhibition organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society in partnership with the Jane Goodall Institute.

An exhibition organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society in partnership with the Jane Goodall Institute.

Lead Sponsor: Susan Sakmar Signature Sponsor: Chris McCloud & Stephanie Dickson

Lead Sponsor: Susan Sakmar

Lead Sponsor: Susan Sakmar Signature

Lead Sponsor: Susan Sakmar Signature Sponsor: Chris McCloud & Stephanie Dickson

Lead Sponsor: Susan Sakmar Signature Sponsor: Chris McCloud & Stephanie Dickson

Chris McCloud & Stephanie Dickson

When summer is over, and those warm October days we are so often spoiled by in the Gallatin Valley are gone, Bodhi Farms moves the Field Kitchen into a dining tipi and serves dinner on Thursdays,

Fridays, and Saturdays through winter. It’s a totally different experience, Rayner says, but a more intimate one, and one that can feel more in sync with our circadian rhythm as humans. “It’s slower.

The seatings are a lot smaller, and the chefs love it. They get to spend even more time with each plate,” he says. And it’s not hard to imagine this crew making the most of their extraordinary setting, still growing and utilizing herbs, microgreens, root vegetables, and wild game. “We keep a fire burning every meal of the year,” Rayner says. “Summer’s easy. Summer’s great,” he says. “It’s hard to mess that up.” But winter is cozy, he says.

For her part, Tanya is keen to focus on the guests’ experience of being at Bodhi Farms. “When you’re completely surrounded by nature,” she says, “your nervous system slows down before you even arrive at your experience,” whether that be dining, yoga, or one of the many

activities offered to guests at the farm. “We have specifically designed the layout of the farm so our guests walk through the gardens to get to the dining table, walk along the creek to get their massage, and see an array of rare birds as they walk to the sauna,” she says.

After we’ve had the last bite of carrot cake in big wooden Adirondack chairs by the fire, and the first stars of the night burn pinholes through the darkening sky, we wander back down the trail, listening to the creek, savoring the glow from the yellow cutleaf coneflowers that line its banks, and feel our hearts beat slow and full.

Carter Walker is the author of several guidebooks, including two upcoming editions of Moon Montana & Wyoming (November 2025) and Moon Yellowstone to Glacier National Park Road Trip (May 2026). She spends a lot of time on the road between Montana’s Horseshoe Hills and the Yaak Valley.

Photographer Lynn Donaldson shoots regularly for National Geographic, National Geographic Traveler, Travel & Leisure, Sunset , and The New York Times . The founder and editor of the Montana food and travel blog The Last Best Plates, Donaldson lives outside of Livingston, Montana with her husband and three children.

Sara specializes in destination wedding planning services for those planning from outside Montana. From Glacier Country to the stunning Paradise Valley near Livingston, and many places in between.

@Weddingsbysaramt

HISTORY | CATHARINE MELIN-MOSER

Ogden the Westerner’s $1.6-million upset

Editor’s Note: This column is adapted from When Montana Outraced the East: The Reign of Western Thoroughbreds, 1886-1900 by Catharine Melin-Moser (University of Oklahoma Press, April 2025).

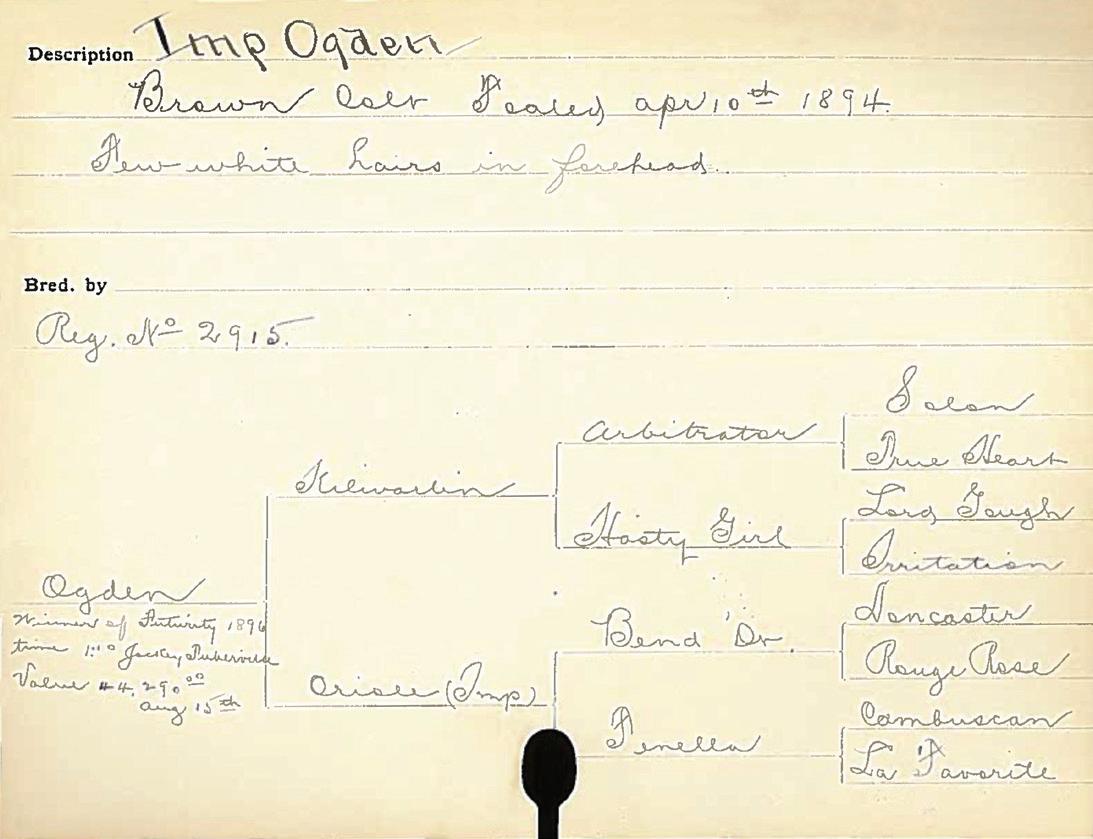

NINETEENTH-CENTURY MONTANA FOLKLORE tells of a beautiful chestnut-colored Thoroughbred mare named Oriole. On April 10, 1894, the heavily pregnant mare traveled west by train. At a siding at Ogden, Utah, the locomotive paused expressly for her comfort. The steam engine idled while Oriole lay inside the stockcar and gave birth to a brown colt. The tale was passed from one Montanan to the next. In the 20th century, an unidentified horse-racing historian dusted off the truth. It’s almost painful to have to deny

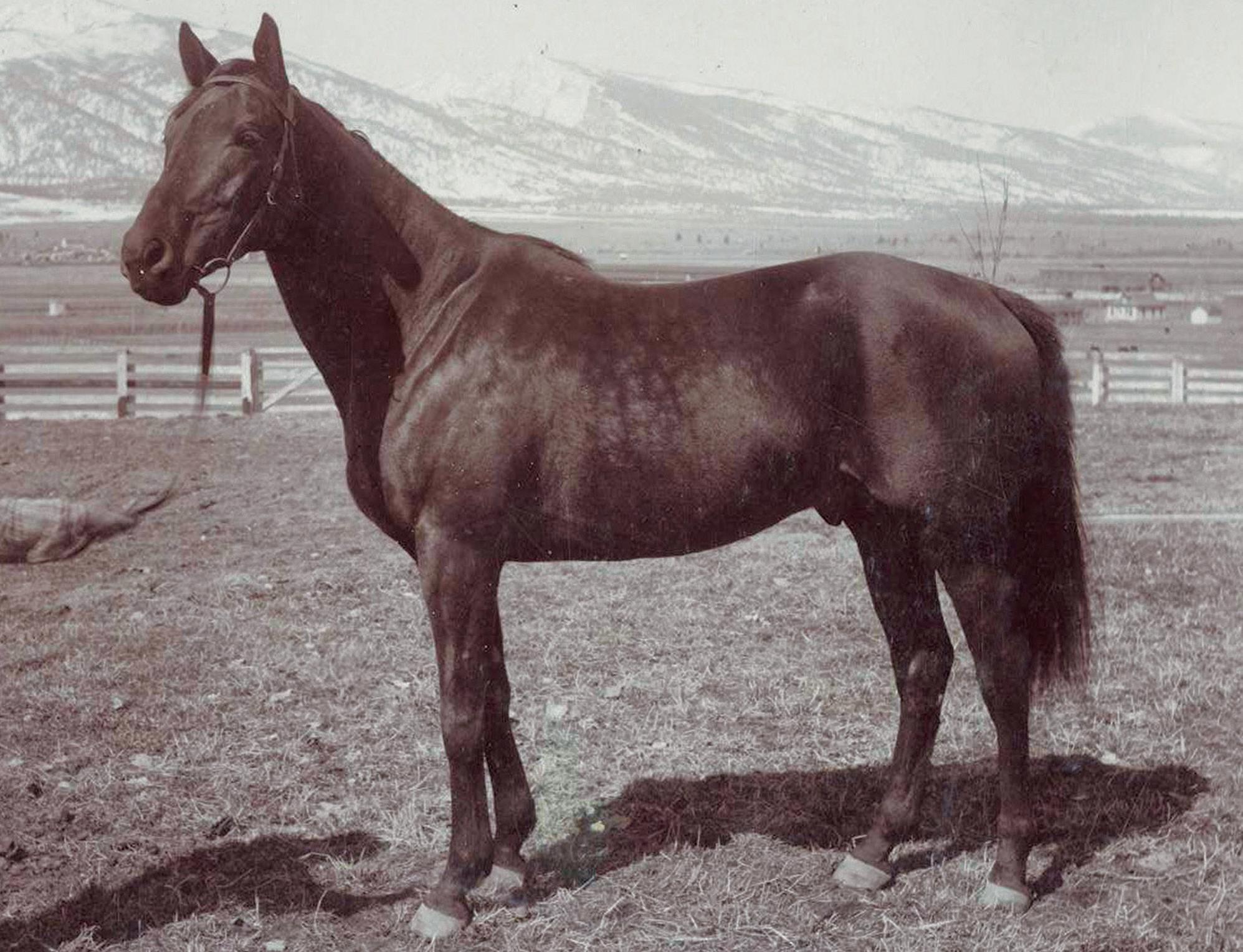

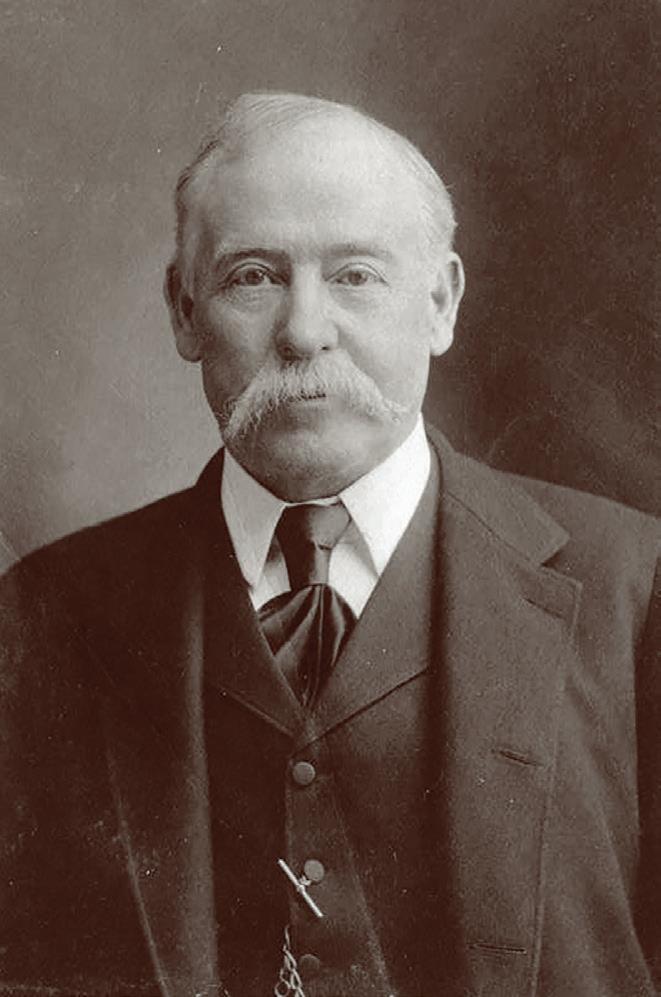

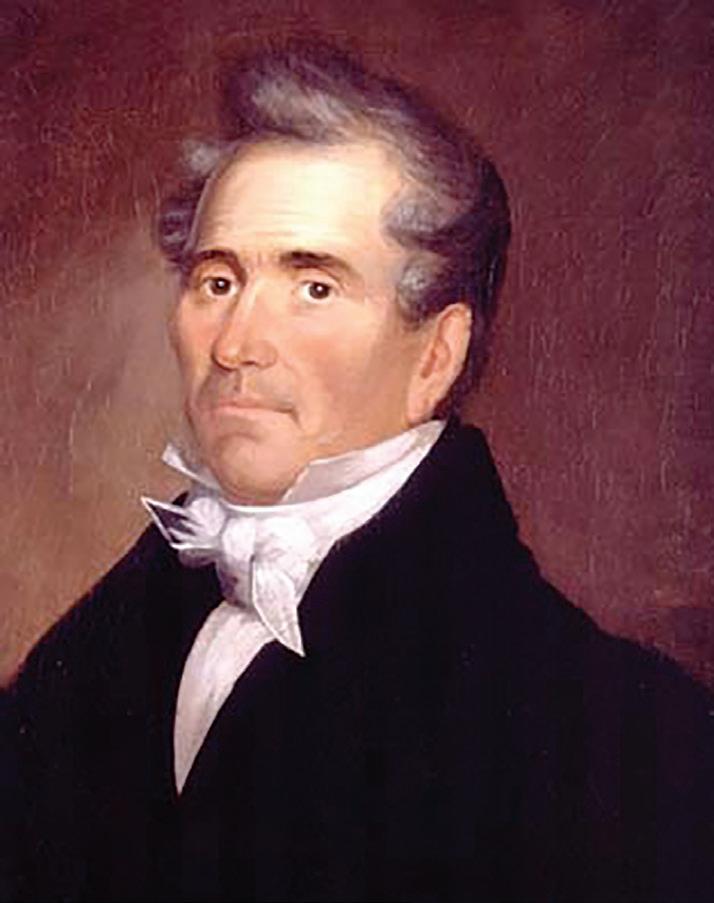

FROM TOP : Ogden is pictured here at the Bitter Root Stock Farm. The date of the photo is unknown. • Unwavering in his belief that Montana could grow superior Thoroughbred horses, Marcus Daly audaciously stated: “When you read in the papers of a few years hence that the winner of the Futurity or the Realization were bred by Marcus Daly of Montana, do not be surprised, as the dry, bracing air and rich grasses of Montana are sure to give the youngsters plenty of lung power, with the constitution and conformation, backed by good breeding, to compete with the horses bred anywhere on the face of the globe.”

the myth of Oriole delightfully steeped in American West romanticism, but there was no locomotive or pause or stockcar, and the place she foaled, well, that’s off by a hemisphere: It is England where Oriole foaled her colt, in the coziness of an Englishman’s estate, in April 1894. She and her colt soon sailed for New York, having been purchased by Marcus Daly, an American copper-mining magnate.

They rode in a stockcar to their new home, the Bitter Root Stock Farm near Hamilton, Montana. The colt was named Ogden, and as one observer said, “a good big little horse … compact, muscular, with good bone … good feet and legs, clean hocks.” Striking black points and a black mane and tail accentuated his brown coat perfectly.

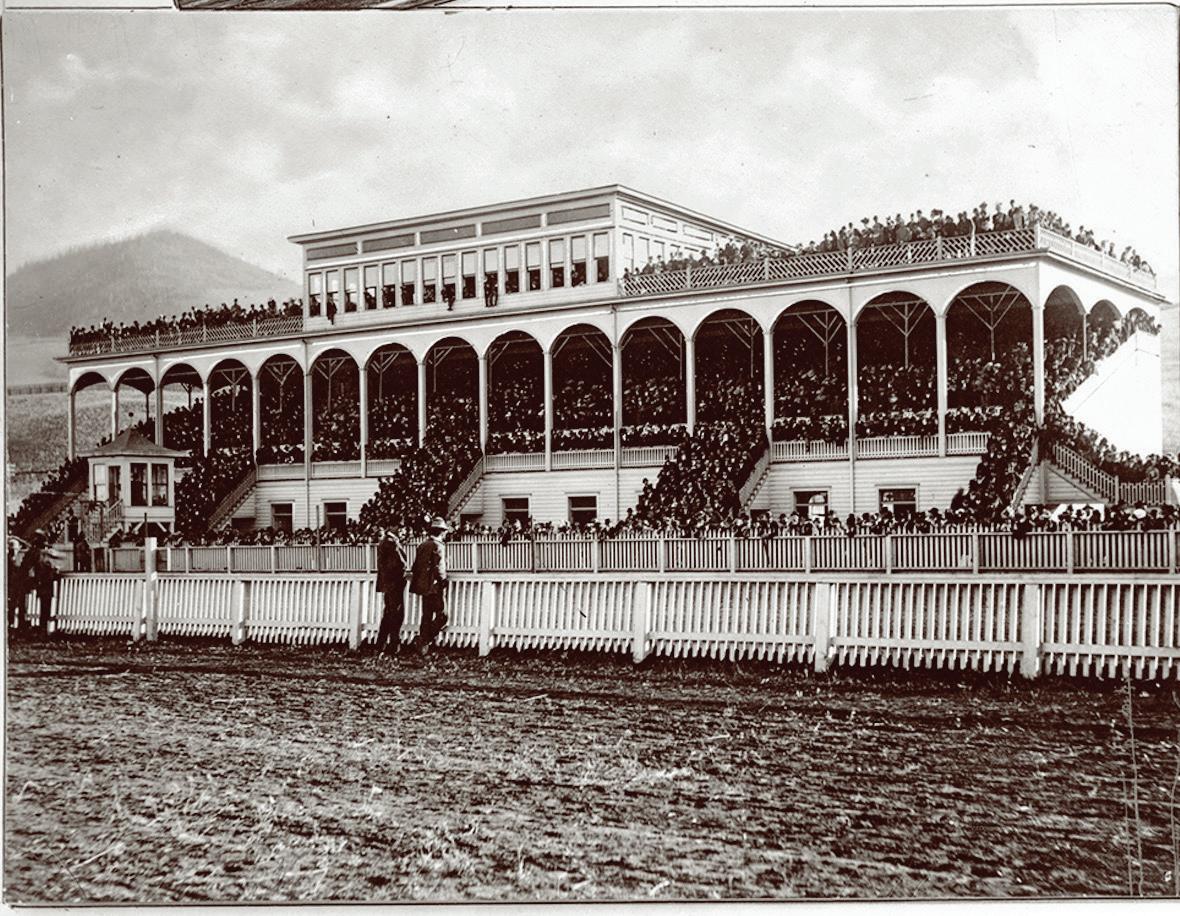

Marcus Daly was so rich he could afford two divisions of his Riverside racing stable. He employed Johnny Campbell as trainer for the Thoroughbreds that raced under the Western division. In Anaconda on July 9, 1896, the Anaconda Driving Park was abuzz with smelter men and miners, gamblers, merchants, millionaires, colorfully dressed ladies, brothel keepers and their girls, cowboys, farmers, and politicians, all bumping up against one another in the grandstand, paddock, and betting shed.

Moments before the second horse race started, jockey Frank Duffy clutched a fistful of coarse black mane in one hand, reins in the other, and hung on. Ogden bolted into his powerful stride and won his race by a length.

the

the

Daly’s racing colors, alternately silver,

and green. • This betting frenzy took place prior to the 1894 Brooklyn Handicap at Gravesend Racetrack in Brooklyn, New York. Methods for betting at 19th-century racetracks were predominantly by auction pool or bookmaker. If choosing the auction pool, an auctioneer on his stand put up for auction every horse entered in the race. Bettors bid on the horse they liked. The highest bidder “won” the horse, and after every horse had been auctioned, the winning bids were placed into a winner-takes-all pool box. The bettor who purchased the winning horse won the pool, with the auctioneer retaining a percentage. At bookmaking stands, the bookmaker shouted the odds he offered. An assistant at his elbow recorded bets as fast as bets were made, and a second assistant accepted and counted the paper bills handed over.

Meanwhile, trainer Matthew Byrnes was in New York where he was racing the Eastern division Thoroughbreds. The topflight two-year-olds he had selected for Eastern racing had flopped, and Daly was determined to win one of the most prestigious fixtures on the New York calendar, the Futurity, set for August 15. The winner’s purse of $43,940, roughly the equivalent of $1.6 million in today’s dollars, was the richest a two-year-old could win in America in 1896.

It was late July, and Daly and Byrnes scrambled to make a fresh draft by plucking Western division colts.

Johnny Campbell repeatedly urged Daly to pluck Ogden. Daly refused, as he had great confidence in Byrnes, who judged Ogden to be too immature for Eastern racing. Campbell, desperate, turned to Hugh Wilson, one of the few men who held sway with his boss. The trainer got straight to the point: “Try and persuade Mr. Daly to let me take Ogden East to run in the Futurity. I know this is a great colt, the best I ever saddled.”

The next morning at the West Side Racing Association track in Butte, Campbell loaded Ogden with 125 pounds of tack and jockey and put him to the business of a seven-furlong workout. The colt needed only 48 seconds. Witnessing that, Wilson went looking for Daly. The boss gave in, and Campbell’s smile “could almost be heard,” Wilson said. Campbell told Wilson, “Have a bet on this colt when he starts in the big race. He will win as sure as he starts.”

Eastern turf writers covering the Futurity grumbled loudly when Ogden dropped into their laps virtually overnight with some kid jockey, Frank “Doc” Tuberville. Pre-race odds for the unknown Western horse were quoted as much as 150-1. On Futurity Day at Sheepshead Bay racetrack, the course was dry and fast under a bright-blue sky. Mingling with the crowd was the small coterie of Montana miners who had seen Ogden race in Montana. They were certain he’d win the six-furlong Futurity. As they entered the betting shed, they made a startling discovery: Ogden and stablemate Scottish Chieftain were coupled in the betting. They threw a fit. They wanted Ogden straight, no mixing him up with the other horse. Their protests, pointless, impelled each miner to state defiantly, “I’ll bet a hundred on Ogden ,” when registering his bet. By post time, 6-1 odds on the Ogden-Scottish Chieftain ticket were attributable to Scottish Chieftain’s popularity. The Futurity favorite, Ornament at 9-5, and seven more high-voltage two-year-olds stood ready at the post. The starter’s flag whirled. Ogden and Ornament sprang ahead of the field. Volumes of moist, sea-level oxygen poured into Ogden’s lungs, powering

his gliding muscles, as he slipped slightly ahead of Ornament. Jockey Tod Sloan astride Ornament struck his whip and lifted his spur. The colt’s lightning-quick strides began to reel in Ogden. The crowd jumped and screamed for Ornament, and they readied for a dramatic duel until the unthinkable — Ornament bobbled mid-stride! They shrieked and wailed, and Sloan worked fast to regain control of his mount. Doc Tuberville, not wanting to risk anything to chance, touched his colt once with whip and spur. Ogden wheeled past the finish, crossing the wire more than a length ahead of Ornament. The perfect ride in the time of 1:10 was the fastest six furlongs in Sheepshead Bay history.

Tuberville trotted Ogden back to the judges’ stand where he dismounted and handlers led Ogden away. Thousands in disbelief murmured, “Who is this Ogden? Who is this boy Tuberville?” Jubilant Montana miners struck up a “war dance” on the lawn, and a New York Time s reporter on the scene began writing, “The wild Western fashion had taken possession of them. They threw their hats into the air, yelled at the top of their voices, and gave an exhibition of just how very excited men can become over such a thing as a horse race.” The miners kept rollicking, and the writer enthused, “The friends of Ogden danced and cheered and halloed [sic] and hurrahed as no similar coterie of men has ever before done at Sheepshead Bay.”

The New York Journal headline of the next morning exclaimed, “Ogden the Westerner, First. Futurity’s Great Prize Taken by a Horse of Mystery Ridden by a Boy of Mystery.” The Journal’s overnight sleuthing had demystified some of the mystery. “Ogden is just a plain-looking brown horse, coming out of that nowhere of the West, Montana.

Tuberville is just a little earnest-faced, brown-eyed, thin-lipped, soft-voiced person, also from out of the nowhere. But he is a dare-devil horseman, and he has ridden the winner of the Futurity.” Newspapers on Ogden’s home turf told of celebrations throwing Montana towns into “the wildest time ever.”

Ogden’s blistering Futurity performance inferred greatness, but disappointing losses would later outnumber memorable victories. He tallied 15 wins in 28 starts, with career earnings totaling $59,970. Greener pastures were in the stud. The last man to own Ogden, John E. Madden of Lexington, Kentucky, selectively bred the stallion to exquisite broodmares. A lengthy run on the American winning-sires list illustrates Ogden’s legacy as a sire: runner-up in 1908 and 1913, third in 1915 and 1916, and fourth in 1914.

Upon the death of his favorite Thoroughbreds, Madden buried them in a peaceful corner of his farm, Hamburg Place. When Ogden passed on New Year’s Eve of 1923, a new grave appeared in the shimmering bluegrass.

Catharine Melin-Moser’s articles about horse racing, Western history, and the outdoors appear in numerous journals and magazines. She writes from her home in the Judith Mountains of central Montana. Her book, When Montana Outraced the East: The Reign of Western Thoroughbreds, 1886-1900 , was released in April 2025.

Poised on a ridgeline above Bozeman, a home inspired by mid-century modern style celebrates 360-degree views of the Gallatin Valley

PHOTOGRAPHY BY WHITNEY KAMMAN

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION — that time-honored but repetitious maxim defining an ideal parcel of real estate — found perfect proof when a couple with an already established home in Bigfork, Montana went looking for a place in Bozeman, where their two grown daughters live. “Our real estate agent had been trying to show us this piece of property forever,” recalls the husband. “But he’d told me it was just pastures, and I’d wanted somewhere with mature trees. Once I got to the top of the hill and looked around, though, I said, ‘We’re buying this!’ From the views, I could not imagine a better situated place.”

Though less than a 10-minute drive from the heart of town, the 27-acre parcel offered incomparable vistas. To the east and south, those pastures the agent had mentioned did indeed appear, gently rolling away toward distant scenes of the Gallatin Range. Gradually sweeping westward, the wraparound panoramic view took in the Spanish Peaks and then the city of Bozeman below. And if all that was not majestic enough, the property’s northern prospect was the most magnificent of all, gazing directly toward the Bridger Mountains, with Baldy’s 8,914-foot summit perfectly centered, complete with its more-than-a-century-old limestone rock “M” honoring Montana State University. “I said to my wife, ‘This is awesome! It’s exactly what we want, even though it doesn’t have a tree on it.’”

WITH THE LOCATION secured, the couple’s next challenge was deciding on a style for their new home. He preferred a more rustic Western look, like their place in Bigfork. But with this second home, she says, it was her turn to determine the style. When they first met with architect Jeff Lusin, principal and owner of the Bozeman-based firm 45 Architecture & Interiors, who’d come highly recommended by one of their daughters, the wife brought along photos she’d liked in a magazine article on a new mid-century modern-style home overlooking Washington’s Puget Sound. “And,” she continues, “Jeff said, ‘That’s really funny. I worked on that house in one of my first jobs in architecture with the firm that built it.’ So, once we’d met with him, we didn’t interview anyone else for the job. He and his colleagues could clearly execute what we wanted.”

The team at 45 — which, says Lusin, “takes its name from the latitude through Bozeman, because we were founded in 2014 as a community-centered architecture firm” — designed the 5,100-square-foot single-story home with an eye toward the wife’s preferred look, composed of unornamented, simple rectilinear forms; generous windows in every direction to glorify the wraparound views; and broad eaves to provide ample shade on sunny days and shelter from rain and snow.

At the same time, notes Tanner Skelton, 45’s director of residential design and lead designer on the project, they also paid respect to the Mountain West setting by incorporating one particular regional material: local fieldstone known as Montana moss rock, which they power washed to remove some of the rustic patina suggested by its name. The result, says Skelton, “is a delicate balance of glass, steel, and wood, with stone walls that anchor the building at one end.”

Before the eloquent structure could rise, however, the team faced one unexpected challenge. The ideal, level site on the property from which to take in those all-encompassing views turned out to contain 27 feet of unstable soil that wouldn’t support a home. “A soil engineer would not have been comfortable setting a foundation on that,” says Andy Rowe, principal at Alpenglow Custom Builders in Bozeman, the contractor who led a team of some 80 people in all aspects of the home’s startto-finish construction. So, the first step in bringing everyone’s vision to reality involved drilling 133 holes deep into the subsoil and then filling them with compacted granite to provide a secure base necessary for the structure.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Easy-care handmade cement tiles from Cement Tile Shop cover the mudroom and laundry floor. • Custom cherry media cabinets and a cherry-paneled reading nook flank the Montana moss rock fireplace. The painting, Lady and the Fox, is by Montana artist Mika Collins. MFGR Designs in Bozeman made the custom coffee table with an Oregon black walnut slab top and powder-coated steel base. • The infinity white quartzite’s veins on the island top (made up of two book-matched pieces), wall counter, and stove backsplash echo the mountain contours on view.

From the early stages, when plans were still being finalized, another key player joined the team: interior designer Jessica Herbst, owner and founder of Bozeman’s Thistle & Twine Studios. “I like to work closely not only with the clients but also with the architect and the contractor, so that I can incorporate all of their visions into the designs,” she says. The primary goals Herbst established through this initial process were based on her understanding that “the clients love a home that feels lived in. So, they needed to have durable finishes or ones that, if they got scratches, only developed more character. And, though they like higher-end things, they wanted it all to feel casual.”

To help Herbst develop options within those guidelines, the clients sent her a wide selection of inspirational images they gathered from magazines, Pinterest, Google searches, and other sources. She sums up the overall look as “simple, minimal, light, and open, with clean lines and nothing to distract from the incredible 360-degree views of the whole valley.”

ALL OF THOSE goals — from the clients, architecture firm, interior designer, and contractor alike — come together harmoniously in the great room, which makes up approximately one-third of the total indoor space. It encompasses a living area with the largest

fireplace Lusin, Skelton, and their team have ever designed; a spacious dining area; and a kitchen generously equipped for an extended family that loves to cook and eat together, all flanked by energy-efficient windows rising to the top of a ceiling 15 feet tall on the north-facing side and 11 feet on the south. Herbst, working closely with her clients, furnished the living space with oversized, comfortable, easy-care seating with low profiles for unobstructed views of the vistas on display.

With the same view-maximizing goal in mind, the main kitchen space was designed without wall cabinets, an absence made up for by the ample storage to the left of the stove wall and by a walk-in pantry that also keeps the refrigerator, a second oven, and a microwave all conveniently close yet out of view. “We had to think out of the box on that one,” says Herbst. Such efficiencies of space also allowed all the more room for an enormous 11-by-6-foot island with a 2-foot overhang at one end — requiring the support of a 3/8-inch-thick steel plate beneath the entire quartzite top — that accommodates casual dining or visiting while food is being prepared. “And the daughters often just hop onto that countertop and talk with their mom while she’s cooking,” adds Herbst.

That kind of casual, communal air is exactly what the clients hoped to achieve in this home. “What we wanted to create was a home that feels immediately comfortable when we have family or friends over,” says the woman of the house. Though the views may be breathtaking, “there is nothing intimidating about our home.”

A similarly gracious spirit extends to comfortable accommodations that the couple offers to guests in a wing separated by both the garage and a woodshop for the husband. At the end of a long hallway — with one wall displaying framed art and the other punctuated by a series of seven tall, west-facing windows — are two private guest bedrooms, each with its own en-

suite bath, as well as a shared outdoor deck that takes in the southerly view. “Visitors feel very welcomed,” says Lusin, “but they have their own space. You could stay there for multiple days and not feel like you’re impinging on their everyday life.”

The home’s primary suite, meanwhile, feels even more sequestered. It occupies the westernmost end of the L-shaped floor plan, hidden away on the other side of the great room’s fireplace wall and buffered from that communal area by a large walk-in closet and a spacious, spa-style bath featuring dual vanities, a deep soaking tub for her, and a custom walk-in marble shower enclosure for him, complete with an overhead rain showerhead.

Comfort and serenity reign in the couple’s bedroom. Although not overly large, it offers enough space for a king-sized bed and a comfortable armchair and ottoman. The chamber’s most important features, however, are the window walls on three sides — north, south, and west — that make it feel like a private viewing station for the vistas in each direction, and a private deck that extends from its west-facing wall in the direction of downtown Bozeman. “During the fall,” says the wife, “if we’re sitting outside in the evening on our private deck, we can even hear the announcers from the stadium at Montana State University, and that’s maybe 5 miles away.”

From glorious views to relaxed living to a comfortably welcoming design, the couple’s original vision of an ideal home in a spectacular Bozeman setting has been fully realized. And that even extends to one criterion the husband set when their search began: mature trees, which had been nonnegotiable until the moment he saw their views. “At last count,” he says with a chuckle, “we’ve planted 75 aspen trees on the property.”

From his base in Marin County, California, Norman Kolpas writes about art, architecture, travel, dining, and other lifestyle topics for magazines, including Western Art & Architecture and Southwest Art . He’s a graduate of Yale University and the author of more than 40 books, the latest of which being Foie Gras: A Global History. Kolpas teaches in The Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension, which named him Outstanding Instructor in Creative Writing.

Whitney Kamman is an architectural photographer based out of Bozeman, Montana. Her love for architecture came naturally growing up with an architect father and interior designer mother. Kamman’s work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest, Robb Report , and Mountain Living , among others.

Blue Ribbon Builders has proven itself as the premier custom homebuilder, for decades, in Big Sky, Montana, and surrounding areas. Whether the scope is a custom dream home or an extensive remodel, Blue Ribbon Builders has the knowledge and resources to design and construct the most complex and ambitious projects.

406.995.4579

•Expo Hall, over 70,000 sq. ft. of wall-to-wall exhibitors featuring the finest guides and outfitters from North America and wherever mountain game hunting is found, plus the best in gear for all outdoor adventures, artwork, gift items, and more.

•$15,000 in Floor Credit drawings for all attendees

•Sheep Show® Mega Raffle

•Entertaining and inspiring nightly receptions, socials, banquets & auctions

•<1Club & <1Club hunt giveaways and beer reception

•RAM Awards and Ladies Luncheons

•Life Member Breakfast and sheep hunt giveaway

•Horse Packing Competition & Backpack Races

•Free Seminars from industry experts and the latest films

•Sheep Show Sporting Clays shoot

•TOUGHSHEEP workout and sheep hunt drawing

•Youth Wildlife Conservation Experience

•More ways to win a sheep hunt than anywhere on the planet!

WADLE

ILLUSTRATION BY

BOB WHITE

IN THE PREDAWN black, I trek up to a saddle off Emigrant Peak’s west flank, nestling into a small thicket of young Douglas fir to watch the day arrive. My back leans against an old rampike, a once-grand whitebark, stripped and bald, but still standing strong. Woodpecker nest holes pierce its bare midriff, and small, punched-out beetle holes dot its nether regions. Gray curls rise from the thermos of coffee steaming in the cold darkness with each unscrewing of the lid. The September dawn, when it comes, rolls up from the Absaroka Mountains in broad Rothko-esque bands of indigo, caramel, rust, and saffron, accenting the few aspen and cottonwood leaves that still cling to their branches. I put away the coffee and bring out the binoculars.

Emigrant Peak stands up so proudly from Paradise Valley that it appears larger than life. I lived under its gaze for many years before I realized it was not the highest peak in the range. Nonetheless, its vast corrugations of ridgelines and gullies hide some very remote country. A few years ago, a friend and I hiked for many hours up and down these ridgelines in a pilgrimage to an old Cold War-era B-47 that slammed into one of them during a training mission on July 23, 1962. We tracked its spilled wreckage across and down two valleys, in awe that this scale of devastation could be hidden amid the mountain’s massive folds.

The impact site still scars the mountainside. Burnt trees wield shards of metal fuselage and wing, embedded like knives in their sides. The last thing we found was the landing gear, two valleys over, and a mile away.

This morning, I am hunting elk. There is no shortage of their spoor — numerous tracks, compressed beds, and waist-high rubs — but I don’t see anything to suggest they are still in the area. I follow a game trail off to the south, moving deliberately and mindfully, step by purposeful step, nose to the wind, eyes scanning for a leg, an antler, a twitching ear.

THE FIRST TIME I hunted was with my uncle. A Vietnam vet, his outdoorsmanship was regarded with awe by the family. It got him through the war, where, against all odds, he and one other survivor from his Marine platoon found their way back home through a treacherous jungle. After the war, he took to the woods and became a bow hunter. In the mountains of Colorado, he offered to let me come along. I must have been around 11 or 12 years old. It was cold out, and my mother had bundled me up in a big puffy coat and slick moon boots. As we walked through the woods, the swing of my arms announced our presence with an embarrassing “swish, swish, swish.” Needless to say, we didn’t see many animals that day. And though it must have driven my uncle crazy, he never said a word about it. As we camped that night, an entire herd of elk stampeded right past our tent, a boulder in the middle of their flowing stream. I remember lying in my sleeping bag, listening to — feeling — the power of hundreds of hooves rumbling past. I worried they might run us right over.

I didn’t hunt for many years after that. I became preoccupied with sports and school activities, and wasn’t sure of hunting’s place in a modern society. As I grew older, though, I became more distressed about where our food comes from. The industrial food complex — with its feed lots and hormone-stimulated, antibioticdoped animals — concerned me greatly. Eventually recognizing that wild game was as organic and free-ranging as I could get, I began to hunt again.

The first day I ever went elk hunting was a prime example of beginner’s luck. As I sat next to a creek in the Crazy Mountains, I heard a splash behind me. There, not 40 yards off, was a 4-by-4 bull elk, hind legs still in the creek and unimaginably large. Shaking with adrenaline, I had to lie down and rest the rifle on my pack to steady it. The next year, I spied another big bull following a small creek upstream. I scrambled up to the ridge, ran to get ahead of him, and dropped back down to the creek to await his arrival. I was there when he rounded a bend just 25 yards away.

I found my way back to archery hunting the next season. My uncle made me a recurve bow and some wooden arrows. I loved the simplicity of archery. I was drawn to its philosophical, historical, and spiritual overtones. I discovered the pure joy that came with being close to these majestic creatures. One morning, I sat in a lush

green meadow with a small herd of elk, breathing in their fragrant odor and listening to their chirping dialogue. I never took a shot that day but rather sat watching for hours, transfixed, until they moved on. I realized that the process of hunting — the connection it engenders with the natural world — could be even more meaningful than its end result.

Which was a good thing, because I failed to shoot anything else for the next three years.

Back on Emigrant Peak, I follow a game path across a high meadow into a draw. As the morning develops, a bouquet of dead leaves hangs in the air, tall grasses trace circles in a light breeze, and the dead bones of lupine and balsamroot rattle gently against one another. Climbing up the fall line of a north-facing slope dark with lodgepoles, the vague form of a mule deer comes into focus, filtering through the shadows above. Then another, and another.

Ducking behind a tree, I head downwind in an attempt to circle around behind them. I slink carefully along a welltrodden game trail leading around a bend where I’ll be out of sight. Suddenly, the quiet of the hillside is shattered by a clattering of hooves coming from around the bend.

Damn! I think. I must’ve spooked them. Instead, a young doe, ears pinned back, barrels right toward me. I recently read a study that suggested that cats can display over 300 facial expressions. I would have never thought a deer’s face could do the same, but I’m telling you this doe had a look of abject horror in her eyes. Stunned, I step back off the trail because, otherwise, she might run right over me. She doesn’t even look at me as I feel her breeze rush past. It’s all in slow motion. I want to reach out and caress her heaving flanks, but then she is gone.

Another skittering of stones comes from the same direction, and I step back again, fully expecting another deer to come racing past. This time, a massive dog comes bounding around the bend in great big strides. Who the hell’s dog is that?! Realization dawns slowly: Simultaneously powerful and supple, steel cables wrapped in fur, this is no domesticated dog — it’s a wolf!

He’s 20 yards and closing fast. I intensely want to watch him race past, too, to feel his power as I had the deer’s. But a niggling inner voice prods: If he’s that close to me, could he just decide to take the easier prey? Single-mindedly pursuing his quarry and oblivious to my presence, he rapidly closes the ground between him and the deer. And me. There is no time to draw an arrow. There is no time to think of the bear spray holstered at my side. But there is also, somehow, a peaceful lack of urgency or even fear.

Heeding the instinct for self-preservation, I raise my arms and yell “Hey!” And then I watch, in awe, as the beast, seemingly frozen midbound like Wile E. Coyote, turns himself completely around. By the time he hits the ground

a mere 10 yards away, he is already facing away from me. In the most athletic move I’ve ever seen, he ricochets off the ground in the opposite direction, and is gone.

Witnessing something I was not supposed to, I’m left standing in the silent forest, dumbfounded. Not a squirrel chitters, the chickadees have gone mute, and the deer is long gone. Like a misty dream melting into the trees, the world slowly comes back to life. A vibrant sense of aliveness envelops me, but also a wondrously humbling appreciation of my own insignificance. The Japanese call this feeling mono no aware, a joyful compassion for the fact that we are all — the mountain, the deer, the wolf, all of us — nothing but ephemeral patterns destined to eventually fade. If not this minute, then the next.

I’m left to wonder if it all really happened. But I easily find the wolf’s softball-sized tracks deeply compressed in the forest’s duff. The earth always remembers. And I recall my own memories — of the elk flowing around my uncle’s tent, of their back-and-forth chirping and musky perfumery, and of the wolf, still frozen midair in my mind’s eye. My fondest memories, it seems, have nothing to do with killing but everything to do with a curious and undistracted engagement with the world.

These days, we possess the technology to kill quite easily. Not that this outcome doesn’t have benefits, but hunting is about the process.

It is developing a relationship with the animals we seek, understanding the ecology and biology at work, and transcending our own myopic ambitions. Our ancestors evolved as hunters: They were participants in nature, not mere transient spectators. Modern humanity may be able to exist separately from nature — to be appeased by the occasional grand vista or scenic drive through a national park — but it would be an impoverished existence, for we are still possessed by our ancestors’ spirits, still yearning to be a part of the natural world.

Douglas Wadle is an internal medicine physician and a science and nature writer. He is the author of Einstein’s Violin: The Love Affair Between Science, Music, and History’s Most Creative Thinkers . He lives with his wife, Kristin, in Livingston, Montana.

Bob White is an artist and author whose work expresses a misspent youth. Instead of doing his homework, his nose was constantly in the outdoor books and sporting magazines of the day. Consequently, he has wandered between Alaska and Patagonia for over three decades as an itinerant fishing guide looking for gainful employment. He now paints and writes for a living; which is to say, he’s still searching.

Artist Charles Fritz captures Montana moments in time

WHEN CHARLES FRITZ moved to Montana in the 1980s, he ran into a problem. Up until then, the Iowa-born artist had carved out a niche for himself in the watercolor market, painting sporting still lifes: wooden decoys, hanging mallards, shotguns. “But when I came out to Montana, I got interested in landscape painting pretty quickly,” says Fritz. “And I found that watercolors could not communicate the landscape the way I wanted to.”

Part of the problem was practical: Plein air watercolor painting in Montana is a battle against the ultra-dry climate of the Northern Rockies, Fritz explains, where “the paint just dries so quickly” that it’s hard to control on the page. The other problem was emotional. “I think, then, and still now, I’m searching to capture colors as realistically as I can.” And the colors of Montana, he discovered, are simply too vivid for watercolor.

So he turned back to oils, a medium he hadn’t touched since childhood. “I found that oil works really well for representing the nuances of the Montana landscape, capturing the true colors but also suggesting texture, light, and depth. Oil can convey how this

landscape makes you feel.” It’s a testament to the power of this region — though Fritz still keeps a soft spot for watercolors. “I’d like to take them back up again, see where they get me.”

Switching to oils proved to be the right move. In the years that followed, Fritz made a name for himself in the Western art scene. His bright, lively oil paintings capture moments that feel surreal, but are commonplace in Montana: the saturated oranges and blues of a mountain sunrise, the brilliant white of fresh December snow, the yellow glow of clouds at sunset.

“Charles Fritz is your quintessential painter,” says Curtis Tierney, owner of Tierney Fine Art in Bozeman, Montana, which features Fritz’s work in its collection. “His artistic process represents the purest and most focused form of what it means to be an artist, starting with his unique observations of the natural world from the field. Fritz next creates a vision that is refined through studies, either drawings or small oil sketches. His technical skills and craftsmanship, gained through years of experience, are then used to create the finished painting. It’s Charlie’s dedication to make every painting his personal best that so impresses me, that toil and effort on each work.”

FRITZ GREW UP on the rolling plains of Iowa, in the heart of the Midwest. His father was an art teacher, “so there were always creative things going on around the house, all the time,” says Fritz. He sold his first painting in seventh grade, a copy of an Outdoor Life magazine cover. “My parents said I learned to read with Outdoor Life ,” he recalls with a smile.

The artwork he copied was by Bob Kuhn, an illustrator who would later rise to prominence as one of the country’s foremost wildlife painters.

Years later, Fritz’s path crossed with Kuhn’s again. “I ended up visiting him at his home in Tucson,” Fritz recalls. “I brought along my scrapbook from childhood, full of clippings I’d studied as a boy. A lot of them were his paintings, so that was kind of full circle.”

Although Fritz went on to study education and history at Iowa State University, art was never far away. He filled sketchbooks with penand-ink drawings and watercolors throughout his college years. After graduating, he and a friend set off on bicycles across Europe, traveling for months through a string of countries and absorbing centuries of mosaics, paintings, and museum collections. The trip left him exhilarated. “But when I came back to the States, I was broke. I needed a job.” He took a teaching position in Boone, Iowa. “I’d teach during the day but continue to make art at night.”

That routine lasted about a year and a half. “That’s all it took for me to leave teaching and pursue a career in painting full-time,” he says.

At first, Fritz leaned into his roots. “It was the Midwest, so the art market was all Ducks Unlimited — very waterfowl focused.”

His move to Montana marked a turning point. “I’d just always wanted to get out here,” Fritz explains. When he arrived in Billings, he quickly immersed himself in the local art scene. Established artist Hal Diteman became an early mentor. Fritz spent a year going to Diteman’s studio daily to learn and hone his craft. “That experience served as a real springboard for the rest of my career,” says Fritz, who also joined a critique group of fellow young artists in the city. “We were all striving to improve and get better, and we all encouraged each other.”

This was the period when Fritz switched to oils. The transition wasn’t seamless, but he stuck with it. “I’ll tell you something, my friend Hal Diteman once told me: ‘If oil painting were easy, there’d be more good ones,’” Fritz shares with a laugh.

In the years that followed, Fritz became known as an oil painter of the American West. This identity made him the perfect candidate for the once-in-a-lifetime project he undertook in the late 1990s, his Lewis and Clark collection. The idea began with a single commission. An art collector asked Fritz to paint a scene described in Meriwether Lewis’ journal, the moment the Corps of Discovery reached the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers.

The Poetry of Thick Paint

Summer Passage was painted with palette knives in rhythmic strokes that create a sense of movement and energy. Painted from a series of field studies, the technique captures the essence of nature in rough-hewn, complimentary colors.

Summer Passage oil on canvas, 30” x 30”

bradteare.com

instagram: @bradteare phone: 435.232.1863

The project stirred something in Fritz. “There had been no artist on the expedition when it actually happened,” he explains. “And as a history buff, I’d always been interested in it.” With the bicentennial of the journey approaching, Fritz saw an opportunity; he would retrace the Corps’ route himself, using Lewis’ journals as his guide, and paint the expedition as though he had been its artist. “I thought, man, I could have been the artist on that expedition, so why not be that artist now? ”

Over several years, Fritz created 100 paintings for the project, each one rooted in Lewis’ meticulous notes. “The experience taught me a lot about the value of that expedition, and the success of it,” Fritz says. “They traveled over 8,000 miles out and back, and only lost one person. That’s incredibly impressive. They found a way to survive in the harshest conditions.”

THESE DAYS, FRITZ opts to stay closer to home, working primarily from Montana and the Southwest. But he continues to pursue projects that challenge him creatively. One such project was a recent, private commission of an expansive Western scene, completed for a home in western Montana. Spanning an impressive 7 by 14 feet, the artwork depicts Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce during their 1877 flight and trek up the Bitterroot Valley. The work is a masterpiece of engineering, involving custom stretcher bars from New York, canvas from an 8-foot loom in Italy, an angled frame to ensure viewers can see the painting clearly despite its spot high on a wall, and about a dozen installers to help with the job.

But first and foremost, the painting is a masterpiece of color, light, and form. The work has traces of minimalism — in the shape of the clouds or the contrast of light as it hits the landscape —