UTAH’S MIGHTY FIVE

A deep dive into Southern Utah’s thrilling landscapes, including Devils Garden in Arches National Park. PAGE 16

PHOTO BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

A deep dive into Southern Utah’s thrilling landscapes, including Devils Garden in Arches National Park. PAGE 16

PHOTO BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

Grand Teton National Park offers 250 miles of trails, but its best day hike might be Cascade Canyon to Lake Solitude. Reaching the lake is no cake walk — it requires a ferry ride and seven miles of brutal uphill hiking — but an easier trail would draw crowds and warrant a name change. As it stands, just a handful of hikers make this trek each day, and they’re rewarded with grand views of the Tetons.

PHOTO BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

IN 2023, husband and wife Jason Clark and Kristine McGowan set off on a 18-month road trip around the U.S. and Canada, visiting 49 national parks, 25 MLB ballparks and 67 cities. They divided their journey into three segments: the west, the south, and the north. This magazine covers Part I, the west leg of The Big Trip.

CALIFORNIA

Home

Pinnacles National Park

Monterey

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park

East Bay

San Francisco

Point Reyes National Seashore

Sacramento

Mammoth Lakes

NEVADA

Great Basin National Park

COLORADO

Grand Junction

Black Canyon of the Gunnisson

National Park

Dinosaur National Monument

WYOMING

Grand Teton National Park

Yellowstone National Park

MONTANA

Glacier National Park

ALBERTA

Waterton Lakes National Park

Banff National Park

Jasper National Park

BRITISH COLUMBIA

Vancouver

WASHINGTON

North Cascades National Park

Seattle

San Juan Islands

Olympic National Park

Mt. Rainier National Park

IDAHO

Boise

Sawtooth National Forest

Craters of the Moon

6

HOME Where it Started

Kristine has an idea that launches five years of planning, saving and preparing for The Big Trip.

8

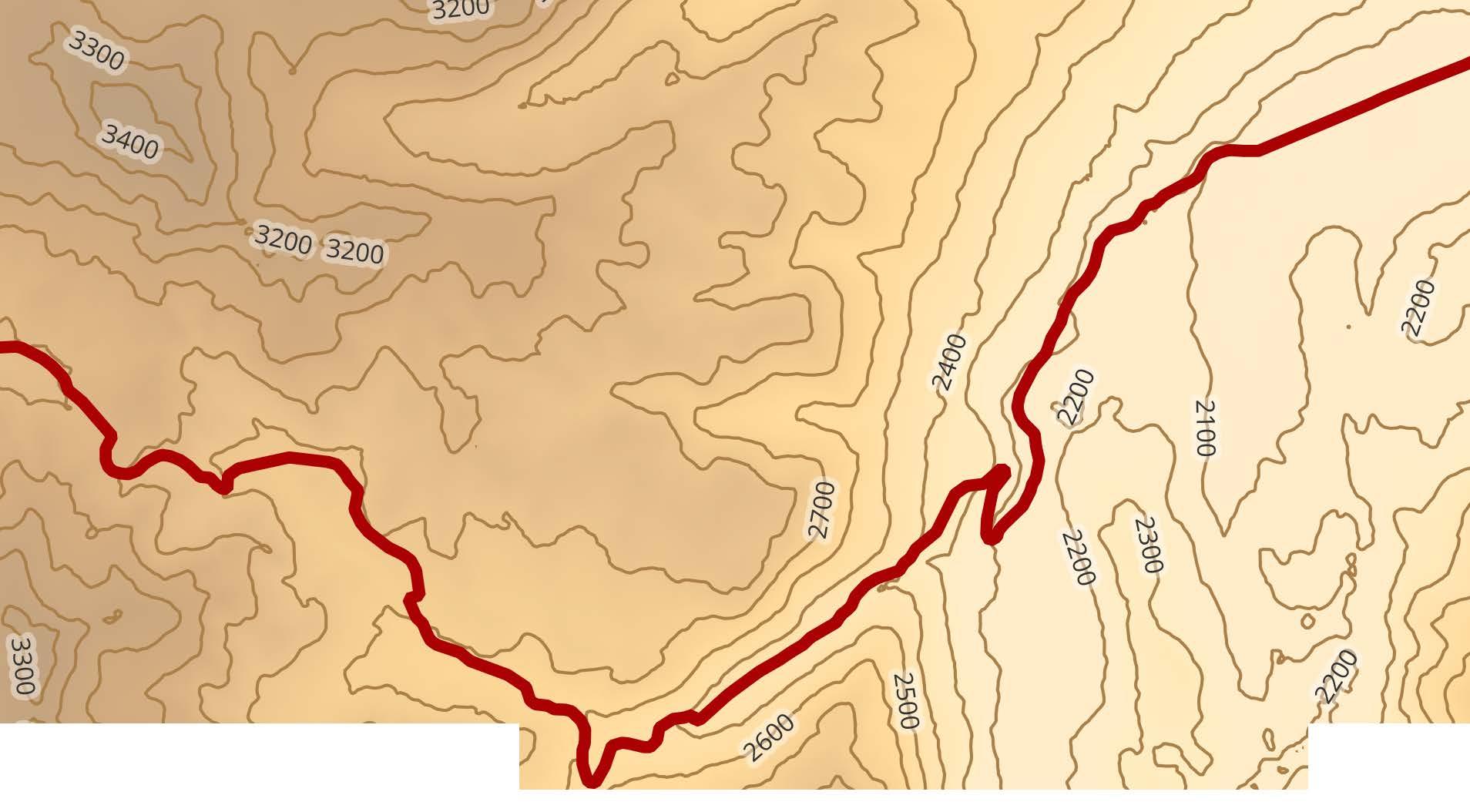

SONORA PASS An Early Test

We take our rig up the steepest highway in the United States — completely by accident.

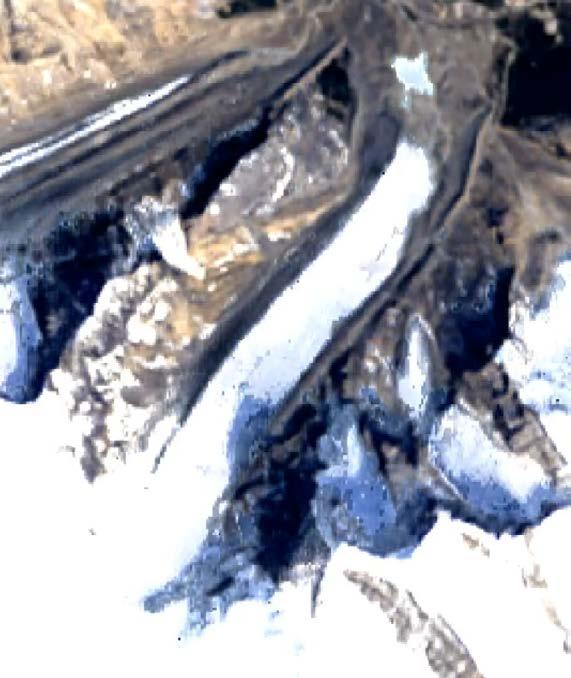

JASPER NATIONAL PARK Climate Change Up Close

The world’s most-visited glacier provides a bleak reminder that it’s on track to disappear entirely. 10

SAWTOOTH NATIONAL FOREST Septem-brrrrr

A couple Californians get a dose of reality in Idaho, where freezing temperatures arrive unexpectedly.

14 BEND, ORE. Nearing Shutdown

A potential government shutdown threatens to disrupt our remaining stops in national parks. 15

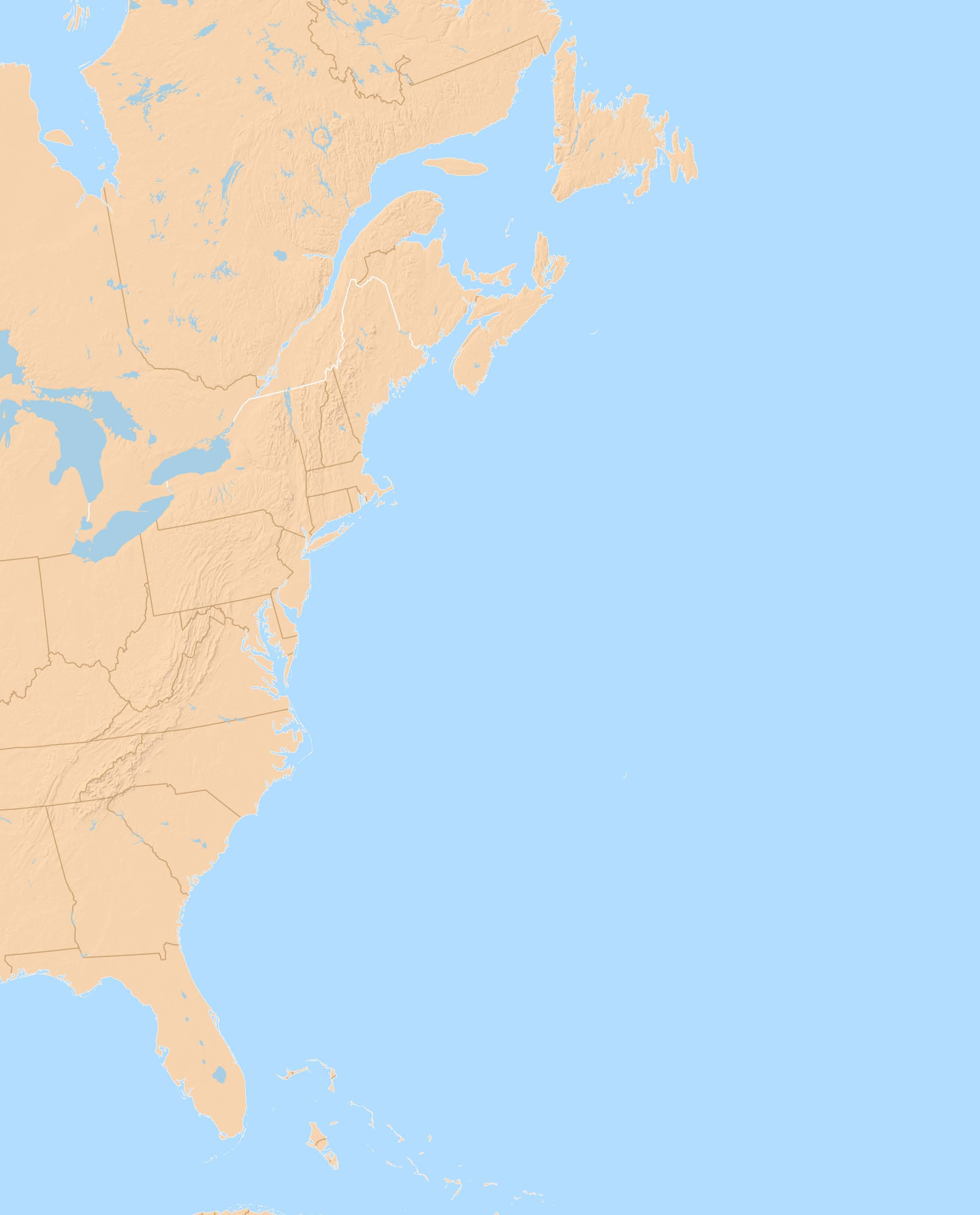

UTAH The Gems of Southern Utah

Five national parks on the Colorado Plateau take center stage in the final month of Part I. 16

National Monument

OREGON

Bend

CALIFORNIA

Redwood National and State Parks

Lassen Volcanic National Park

South Lake Tahoe

Yosemite National Park

Sequoia National Park

NEVADA

Valley of Fire State Park

UTAH

St. George

Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park

Kanab

ARIZONA

Grand Canyon National Park

UTAH

Zion National Park

Canyonlands National Park

Arches National Park

Capitol Reef National Park

Bryce Canyon National Park

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Kristine McGowan

BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

In 2018, just three months into our engagement, I stumbled across an article that would impact nearly every decision my husband and I would make over the next five years.

It was clickbait, one of those promotional pieces that companies put out to show how much their customers love their product. It was published by a bank, though I can’t remember which one. I don’t even know how I found the article. I just remember

lying in bed next to Jason, reading this story on my phone and holding my breath.

The story was about a married couple in their early 30s. They’d saved up enough money to take a year off and travel; they called it a “pretirement.” For a year, they lived out of their backpacks and carry-ons while flying all around Europe. For a year, they didn’t have a permanent address. For a year, they saw more countries and cities than I’d seen for all my 25 years.

My first thought: I want to do this. My second: There’s no way he’ll go for it.

Between my husband and me, I’m the bigger dreamer. My fantasies fall somewhere between just beyond practical and utterly hopeless. Growing up, I wanted to be a bestselling author who used her books and her wealth to make the world a better place (because JK Rowling’s such a fine example these days). Jason, on the other hand, wanted to become a sports writer. His feet were solidly on the ground while mine were trying to walk on water.

So, when I showed him the story, I had his inevitable response queued up in my head: This is cool, but we can’t afford it. We can’t quit our jobs. We can’t take that risk.

As you might have guessed, that’s not what he said.

Instead, he turned to me and said, “Oh my God. We could totally do this.”

I’d never loved him more.

Steve has towed a lot in his young life. Despite being a lovingly named 2022 Ford F-150, he’s already towed our trailer more than 50,000 miles since we hit the road full-time in July 2023.

In all our towing, Steve has never struggled. We’ve never had a problem towing over mountains, along interstates, and through triple-digit heat. Steve is only a half-ton truck, but he has always seemed more than capable of doing the job.

Except, that is, for when we came to Sonora Pass.

For those who aren’t familiar — as we weren’t until we drove up to it — Sonora Pass is another name for a section of Highway 108. It meanders over the Sierra Nevada mountains north of Tioga Pass, the famous road that cuts through Yosemite. We came

to Sonora Pass in July 2023, just a few weeks into our new life on the road, while we were making our way from the Bay Area to Mammoth Lakes.

Typically, we don’t notice the moment a highway turns into a mountain pass. Sure, the scenery and elevation change, but we can’t always pinpoint the exact spot where the transition happens.

Sonora Pass, however, called it out with a big yellow sign:

SONORA PASS AHEAD

STEEP & WINDING GRADE

TRAVEL TRAILERS NOT ADVISED

Jason and I had the same reaction: Wait, what?

By and large, we use Apple Maps and Google Maps for navigation, neither of which takes towing into account. So this sign

was a surprise to us. We pulled over immediately, into the last turnaround available before the pass.

Two other vehicles, a Class-C RV and a truck pulling a fifthwheel, were parked in the turnaround. They were facing in the direction opposite from which we’d come. Maybe they’d driven over the pass, we thought. So Jason walked over and asked how it was.

The driver of the Class-C RV told us it was fine. There weren’t any concerningly tight turns; he’d just pulled over because his brakes were “giving him trouble.” The driver of the truck and fifth-wheel wasn’t around, so

we didn’t get a chance to talk to them, but we felt reassured by the RV driver. So Jason hopped back into Steve, and we steered ourselves toward the pass. About 10 minutes later, we realized we never should have been concerned about the turns.

The real bitch in this situation was the grade. Pretty quickly, Sonora Pass kicks off with a 20% grade — and it keeps going and going and going. Steve had never towed at such an incline before and certainly not for so long. Add in the 95-degree heat, and we realized

13% 15% 26%

Utah Route 143 Parowan to Panguitch, Utah

Texas FM Road 170 Candelaria to

Butte, Texas

California Route 108 Sonora Pass, Calif.

we could be digging ourselves into some deep shit.

We went slow, mostly because we had no choice. We couldn’t turn around, and our speed dipped as low as 12 miles per hour. Our eyes stayed glued to the temperature gauges on Steve’s dashboard, which seemed to be climbing at the same pace that we were.

My heart leaped into my throat at times. I don’t do well in vehicles on unlevel terrain. When we’re parking our truck on the side of a road, I have a habit of screeching, “Oh my God, we’re gonna roll” as soon as one side of the truck lifts higher than the other. More than once, Jason has ordered me to get out of the truck so he can finish parking.

All that said, we weren’t the only ones struggling on Sonora Pass that day. Nearly everyone else was too, towing or not. (We were not the only ones towing a trailer, despite the big yellow

sign.) After we got through the worst of the climb, we pulled over and parked on relatively level ground to give Steve a chance to cool down (and my heartrate a chance to slow down). His temperature gauges hadn’t stretched into the red yet, but we weren’t comfortable with pressing on regardless. We popped the hood and, when it seemed safe to do so, we put on work gloves and slowly — slowly — unscrewed the coolant reservoir’s cap to relieve the heat and pressure that had built up inside.

Not long after that, a minivan pulled over behind us. The driver got out and asked if we were OK, and after we said yes and asked if he was OK, he told us his rental car wasn’t handling the climb well either. It needed a chance to cool down, too. Clear-

ly, despite our crawling pace, we weren’t holding anyone up.

We all stood around for about 20 minutes, relaxing into the ease of small conversation and reassuring each other that the worst was over. The minivan driver was from Perth, Australia, and he was heading to Lake Tahoe, where his daughter — waiting in the van — would compete in the Tahoe 200 Endurance Run. We told him about our favorite pancake place in Tahoe, Heidi’s Pancake House, and all three of us ragged about how awful LAX is.

He probably doesn’t realize it, but this Aussie from Perth helped us enormously that day. Our short conversation had a sense of camaraderie weaved through

it — something that said, “Yeah, we probably shouldn’t be here, we all made dumb decisions today, but we’re out here now, so we’ll help each other out and make the best of it.”

When the Aussie decided to move on, he left us with a cheery, “Hope we all make it!” By that point, I was certain we would. We could do this. Steve could do this.

We did make it. We got to Mammoth safely. Once again, Steve had proved himself capable.

And Aussie, if you’re reading this—we hope you had some good pancakes in Tahoe.

Wildfire smoke and shrinking glaciers make for a bleak combination in the Rockies.

BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

On our sixth day in Canada in August 2023, we set out for the southernmost tip of Jasper National Park to see one of its biggest attractions: Athabasca Glacier.

Athabasca is a 2.5-square-mile “toe” extending from Canada’s Columbia Icefield, the largest ice field in the Rocky Mountains. If you’ve been lucky enough to see a glacier — or, better yet, walk on one — you know it’s a transformative experience. I’ll never forget the glacier calving we witnessed in Alaska’s Kenai Fjords National Park in 2021; I can still hear the ice crashing into the ocean, the thunder of it rattling my bones.

But every glacier experience comes with a somber undertone. These icy behemoths are disappearing. As wondrous as they are, they’re also a stark warning that our world is changing much faster than we’d like to believe.

That’s what our morning at Athabasca felt like — a warning. Or, really, several warnings rolled into a single moment.

Along the pathway leading up to the glacier, colorful signs traced the ice’s retreat over the years. We saw how far the glacier had extended in 1884, 1902, and 1935; at the 1992 sign, the year we were born, we still couldn’t see the foot of the glacier. We had to climb over the next rise and walk a couple hundred yards more.

That would have made the experience sobering enough, but two other things hung over our heads

that day. For one, by the time we reached the glacier, we couldn’t see much of it — because it was shrouded in smoke. At the time, summer 2023 was shaping up to be Canada’s worst wildfire season on record, and smoke had been following us for days. It blanketed Athabasca’s tongue-like shape on the morning of our visit. Had I not known better, I would have wondered if the Columbia Icefield was working its way through a thousand packs of Marlboros.

For another, while inhaling smoke at the foot of the glacier, we had home on our minds. Tropical Storm Hilary — cooked up by both natural and human-caused factors — was barreling toward our families in Southern California, the first such storm to make landfall in our home state in 84 years. Fortunately, the storm wouldn’t hit our families as hard as we’d feared, but squinting through the haze shrouding Athabasca, I still felt my gut twisting.

A melting glacier. Raging wildfires. A surprise tropical storm. It felt like the planet was screaming. It’s not lost on me that we’re contributing to climate change by embarking on The Big Trip. Assuming we successfully complete our route, we’ll have driven about 80,000 miles by November 2024. That’s a lot driving, and a lot of emissions. Especially when you consider how many of those miles involve towing.

I don’t have a justification for that. I can’t say, “But we’re making up for it by doing this.” Sure, our truck’s hybrid engine produces

ATHABASCA GLACIER is estimated to have lost half of its volume since 1900 and is receding at an average rate of 16 feet per year.

fewer emissions during the average drive but not while we’re towing. We intend to look into carbon offsets, but there’s no question that offsetting one’s carbon footprint pales in comparison to reducing emissions in the first place.

That said, in one very small way, I think our visit to Athabasca was a step in the right direction. Before The Big Trip, it was easy to ignore my impact on the environment. I had so many distractions to hold my attention elsewhere: work, my commute, buying groceries, washing dishes, etc. I had almost no sense of how much water I used each day or how much trash I tossed into the dumpster. I only thought about my emissions on hot, stuffy days, when smog collected in the air and turned the horizon into a murky brown haze.

It’s different now. Now, because we boondock so often, we have to ration our water and keep an ongoing mental log of how much we use. We pack out our garbage. And every day, we see how our emissions are reshaping the natural world, breaking down delicate ecosystems. We can’t ignore our impact anymore.

At Athabasca, one of the informational signs presented visitors with a question: What can you do about climate change?

It’s about time I found out.

MAIN PHOTO

Athabasca Glacier is blanketed in wildfire smoke in August 2023.

Photo by Kristine McGowan

It’s late September in Idaho. Temperatures have been mild. And yet, we wake up to find our water gear...

Winter is coming, and we need to check the forecast more often.

BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

On our first morning in Stanley, Idaho, in September 2023, I rolled out of bed to do the first I do every morning, whether we’re living in a trailer or not: I went to the bathroom to pee.

The peeing part went fine, thank you for asking. But when I turned on the sink in our trailer’s bathroom to wash my hands, nothing happened. No water came out. I couldn’t even hear it running through the pipes.

“What the hell?” I grumbled. We had a water hookup in Stanley, which is rare — for us, anyway. We’re almost always boondocking; in fact, I can count the number of times we’ve had hookups on one hand. Boondocking is cheaper, but every once in a while, we relish having hookups. They’re supposed to make things easy.

Grousing, I stomped over to the front door and shoved on my sandals. Someone must have shut off our water hookup, I thought. Maybe this was a prank, though I didn’t get the joke. I just wanted to wash my hands, but no. The world was out to get me.

I trudged to the spigot outside, reached for the handle, and turned it — only to find that it wouldn’t turn any farther; the spigot was already on. That’s when I noticed the gauge on our water pressure regulator.

For the non-RVers out there: We have a water pressure regulator to protect our trailer’s pipes. Water pressure varies from campground to campground, so when we have hookups, we use our regulator to ensure

The low temperature in Stanley, Idaho, was colder than the low temperatures at our most recent stops in Seattle and Boise, and much lower than what we were used to in Long Beach.

ABOVE

A not-frozen pond in Sawtooth National Forest

that water enters the trailer at a safe pressure, usually around 40 psi. This morning, though, the gauge on the regulator didn’t show 40 psi. The needle had spun all the way around — to 120 psi.

I turned off the spigot and tried to remove the regulator, but it wouldn’t budge. I tried to remove the filter attached to the regulator. Then I noticed that the filter’s blue plastic shell had cracked all the way around.

It was frozen. The regulator, the filter, the hose running into our trailer — the water inside it all had frozen overnight.

It was September 24. The day before had been relatively warm, a classic early-autumn day where the sun gently bakes your skin, like it’s pressing a warm loaf of bread to your face. It never crossed our minds that temperatures might drop overnight. But drop they did. Our weather app showed that outside temperatures had dived to 25 degrees Fahrenheit. No wonder our gear had turned into popsicles.

Fortunately, the trailer’s pipes were fine. Our furnace had spared them from the same fate. Our cracked filter couldn’t be saved, but the rest of our water gear thawed throughout the day, no worse for wear. Our hose even gifted us with dozens of cylindrical ice cubes.

It gifted me with a realization, too. Jason and I are from Southern California, the land of traffic and tourist-packed beaches that sees just two seasons a year: summer and lesswarm summer. This incident with our water gear made me realize: For the first time in our lives, Jason and I would experience all four seasons within a year.

That was both a gift and a lesson. We learned to pay better attention to the forecast after that night in Idaho. Going deeper into autumn and eventually winter, we made sure to drain and pack up our water gear at night. Unless we wanted ice cubes in the morning, that is.

A looming government shutdown — and the potential closure of national parks — threatens our plans.

BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

We did a lot of planning before we hit the road in July 2023. We mapped out our route; we selected our rig after extensive research into trucks and travel trailers; and we made sure we had enough savings to cover not only 18 months of life on the road but also several months of life after the road, when we’d search for jobs and a new home (without wheels).

Despite all that, there was something we didn’t plan for: Congress’ inability to negotiate a spending bill that would keep the U.S. government open.

Silly us. How did we not see that coming?

In any other year, a government shutdown wouldn’t impact our lives much, not even when I was working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory before we hit the road. JPL enjoys the complicated position of being funded by federal dollars but managed by a private institution, so they can keep employees working, to an extent, during a government shutdown.

But in 2023? Well. A shutdown threatened pretty much all our plans.

If you follow politics, you know the headaches a shutdown can bring, particularly to our national parks. Previous shutdowns have either shuttered the parks, costing nearby communities hundreds of millions of dollars in lost visitor revenue, or left them open but largely unsu-

pervised, resulting in serious damage to our public lands.

Both approaches were terrible, each one a testament to the embarrassing state of our country’s political discourse. And days before government funding was set to expire in 2023, the Department of the Interior announced what it would do if a shutdown happened: close the parks.

Which meant meant bad news for us. Throughout our Big Trip, we weren’t just visiting national parks, after all — we were living in them.

It was the end of September. We’d just made our way through Washington and Idaho, and we’d stopped in Bend, Ore., to spend a few days in one of our favorite mountain towns. Except now, rather than enjoying the crisp fall weather and Bend’s myriad trails, we were devising a backup plan for ourselves in case a shutdown began on October 1.

We looked at our upcoming route — and our stomachs hurt.

If the government shut down, we would skip some of our favorite spots in California: Redwoods, Lassen, Sequoia, Kings Canyon. To top it off, we would lose our five-day campsite reservation in Yosemite.

If you’ve ever tried to get a Yosemite campsite, you know how gutting this would be.

But we couldn’t do anything about it. Unless Congress got its act together, we’d have to go somewhere else.

That’s when we found a bit of hope in our route: Utah.

In previous shutdowns, Utah’s state legislature funded the state’s national parks to keep them open — and this time around, it planned to do the same. Most campgrounds in Utah’s parks were also operating on a first-come, firstserve basis at the time, meaning campers didn’t need to reserve campsites in advance.

We were planning to head to Utah in November anyway. If the government shut down, we could just head there a little early. And if the government reopened while we were in Utah, we could loop back to California afterwards to visit the places we’d missed, although we’d have to accept that our Yosemite reservation couldn’t be saved.

Fortunately, none of that came to be necessary: Congress did get its act together and passed a spending bill just in time to avert a shutdown. But this emotional rollercoaster packed with loud-mouthed politicians had taught us a lesson by the time the ride ended.

No matter how much planning we do, we can’t control everything. Bad weather, accidents, illness — and, it turns out, inept legislators — all could derail our plans. So we’d have to be flexible, ready to think on our feet at a moment’s notice.

We’d keep this lesson in mind in 2024, a year during which we would do even more traveling. Congress’ budgetary shenanigans are neverending, so we knew another shutdown could be breathing down our necks in the coming months.

We weren’t out of the woods yet — but if Congress’ incompetence threatened kick us out of those woods again, we would be ready.

A typical government shutdown may have little impact on JPL, but Congress’ ineptitude can still inflict damage on the Lab. While a spending bill passed in time to salvage our travel plans, the bill only funded the government through November 17, 2023, and Congress would fail to finalize a comprehensive federal budget until March 2024. As a result of that failure, JPL laid off 530 employees and 40 contractors on February 6, 2024. Our nearly derailed road trip pales in comparison. My heart goes out to my former colleagues.

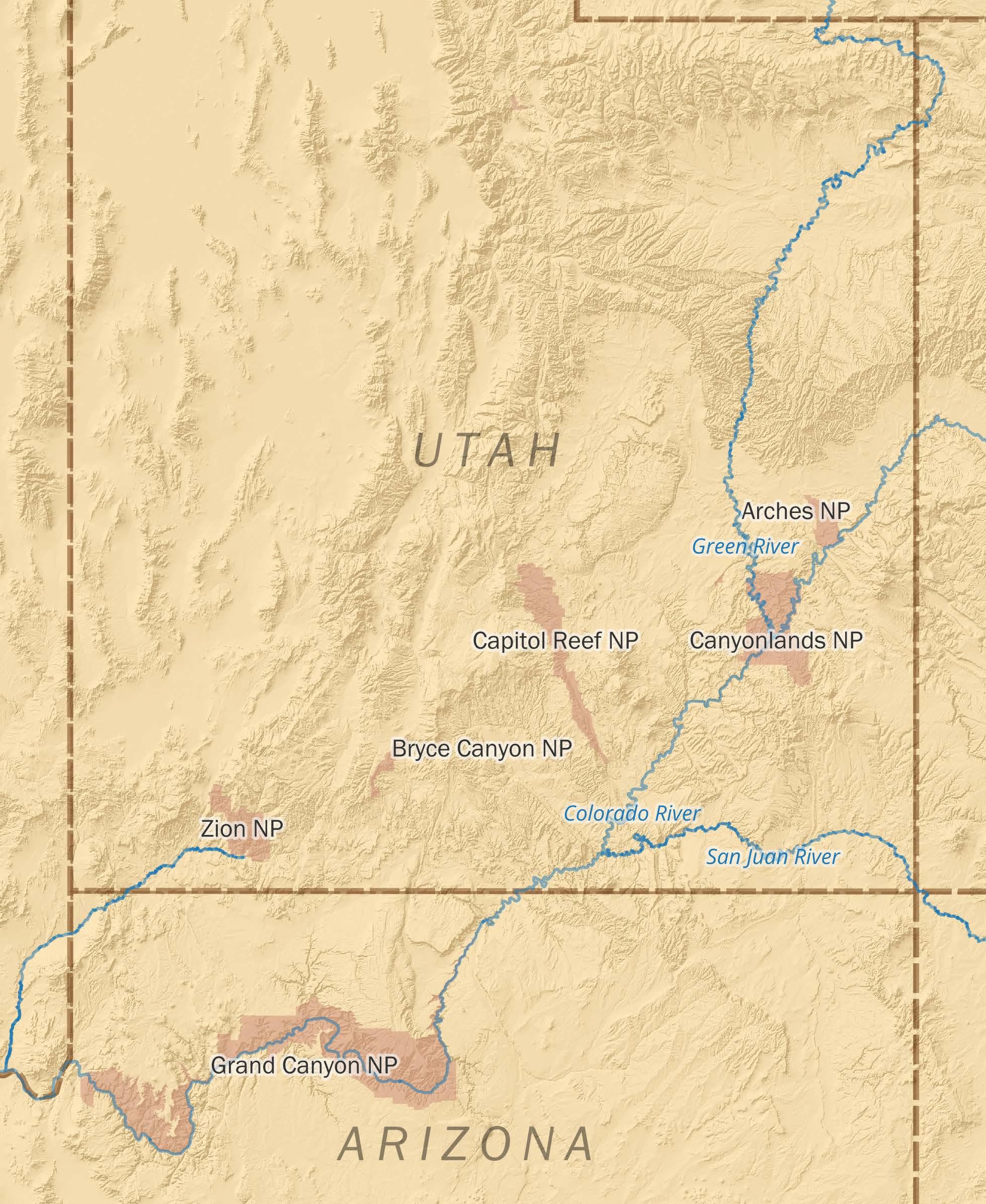

Utah’s national parks offer some of the best adventures in the west.

BY KRISTINE McGOWAN

Utah might just be my favorite state.

One could argue — and I do — that its parks rival the crown jewels of the National Park System, even Yosemite and Yellowstone. (Don’t come at me until you’ve read this whole story, okay?) Each one offers big adventure among unique geological features that, frankly, make my brain implode. They’re incredible to behold, but when I also consider the natural forces that worked together to form these vast canyons, stunning arches, and sandstone cathedrals? They’re mindboggling.

We’d already visited all five of Utah’s national parks, known as Utah’s Mighty Five, before we headed to the state in November 2023. So this time, we wanted to dig deeper. We wanted to do everything we hadn’t managed to do before, because we didn’t have either the time or the equipment, or we’d just shown up at the wrong time of year.

Here’s what we did in each park that autumn, in the order in which we did them. If these adventures aren’t on your bucket list yet, trust me — you need to add them now.

This hike has been at the top of our to-do list for years. We’d never done it before because we didn’t have the time or, more importantly, the experience. Because this hike doesn’t take you on a trail. It takes you up a river — or really, into it.

You can hike the Narrows in one of two routes: as a 16-mile through-hike from Chamberlain’s Ranch or as a 10-mile, out-andback hike from the Temple of Sinawava. Both take you through the narrowest section of Zion Canyon, where thousand-foot walls tower over both sides of the river. But the out-and-back hike doesn’t require a wilderness permit, so we opted for that.

As you might imagine, this trek requires more preparation than your average day hike. Before we headed out, we checked the Virgin River’s flow rate and temperature (both are conveniently provided by Zion Outfitter, just outside the park). On the day of our hike, the flow rate hovered somewhere around 80 cubic feet per second (anything over 70 cf/s is considered challenging to walk in), while the water’s temperature was a toasty 46 degrees Fahrenheit. So we rented dry bibs, canyoneering boots, neoprene socks and hiking sticks from Zion Outfitter to keep us warm and upright while wading through waist-deep water.

We didn’t do the full 10 miles — we never even planned to, given how cold the water was — but we managed to cover about 4 miles. By the end of the day, those 4 miles became some of our favorite we’ve ever hiked.

HIKING DEVILS GARDEN

Of all the times we’ve been to Utah, about 90% of our visits were in winter. So every time we’d visited Arches, the park was buried under snow.

And let me tell you — the Devils Garden trail is impossible to follow when it’s buried under snow. We tried, and we gave up less than a mile in.

That said, without snow, this trail had all the elements of an awesome hike for us: rock-scrambling; route-finding; nooks and crannies we could crawl into; narrow rock walls with steep drops on either side of us; and countless scenic points, featuring eight arches and sweeping desert views.

If you like trails that make you feel like a kid again, Devils Garden is for you.

RIGHT

Delicate Arch in Arches National Park sits a few miles east of Devils Garden.

FAR RIGHT

Druid Arch hides deep within The Needles district of Canyonlands National Park.

The great thing about visiting Utah during winter? The parks look absolutely gorgeous in snow.

The not-so-great thing? After a storm rolls through, it can take hours to plow the roads, and the park(s) stay closed the whole time.

That happened to us not once but twice during our visits to Canyonlands. As a result, before this trip, we’d hardly seen anything in the park’s most popular region, the Island in the Sky district. Which meant we had never even considered trekking out to The Needles district, nearly 80 miles southwest of Moab.

This time around, we headed out that way — and we ended up on a hike that took us to an arch even more mind-blowing than anything we’d seen in Arches National Park.

Like the Narrows, this 11-mile hike requires some preparation, and like Devils Garden, it also requires some route-finding and rock-scrambling. But it has the bonus of winding through one of the most remote regions in Canyonlands, granting you plenty of room to breathe and wander.

Now, Druid Arch is yet another of our favorite hikes. Do you sense theme here?

Something that’s always been off-limits to us on our travels? 4x4 roads.

Before The Big Trip, our trusty Toyota Corolla took us on plenty of trips around the country, but our adventures usually stopped where the pavement ended. Fortunately, our Corolla gets to enjoy a quiet semi-retirement back home now that we have a more powerful vehicle propelling us on The Big Trip: Steve, our trusty Ford F-150 with four-wheel drive.

Thanks to Steve, we explored parts of Canyonlands’ 100-mile White Rim Road, which snakes below the Island in the Sky mesa and takes you to otherwise inaccessible areas of the park. This was our first 4x4 experience in Steve, and — oh man. Let’s just say we’ll search for roads like this everywhere we go.

DRIVING THE CATHEDRAL VALLEY LOOP

After Canyonlands, it didn’t take us long to find another 4x4 road. Gotta love Utah.

Cathedral Valley is home to the most unique parts of Capitol Reef. To see it, you can drive the 58-mile, 4x4 Cathedral Valley Loop, but as always, you have to go prepared. The loop begins and ends at Highway 24, and one entry/exit point requires you to ford the Fremont River. If your vehicle can’t handle the crossing, you’ll have to start the loop from the other entry point and either handle this drive as a 100-mile, out-and-back excursion or simply skip parts of the loop.

When we drove up to the river, the water was about a foot deep. It would have made our Corolla tremble, but Steve was up to the challenge.

And the payoff was huge. The loop took us right up to Cathedral Valley’s sandstone formations, which stand hundreds of feet tall with sides that resemble fluted walls and pinnacles sprouting from their tops. It’s no wonder how this place got its name. I couldn’t believe we’d come to Capitol Reef before without ever setting foot here.

Again — thank you, Steve.

HIKING BRISTLECONE LOOP

All right. I have to admit here: By the time we got to Bryce, we were pooped. I mean, just look at everything else in this list. Altogether, our time in Utah involved back-to-back-to-back days of hiking and driving, not to mention many other miles of adventure that we haven’t listed here.

Fortunately, our remaining to-do-list item in Bryce was a small one: hiking the 1-mile Bristlecone Loop. It took us through an area of the park we’d never seen before, because again, snow has a tendency to close roads out here.

As nice as the hike was, we still felt drawn to other areas of the park, namely the trails we’d hiked on every other visit just because we loved them. So we set out on the Queens Garden and Navajo Loop. As tired as we were, we couldn’t bring ourselves to skip this loop.

I mean, just look at that photo. How could we not?