The University of Georgia is located on the ancestral lands of the Muscogee and Cherokee Nations. I want to honor indigenous communities whose histories have been marked by displacement, colonization, and ongoing oppression. I also recognize that descendants of these and other North American tribes continue to live and work on this land, and acknowledge the enduring legacy of colonization, genocide, and oppression on indigenous lives today.

Our nation's culture, economy, and society are built on the legacies of transatlantic trafficking, chattel slavery, segregation, and the Jim Crow dehumanization of Black people. I want to also recognize the contributions of immigrant and indigenous labor voluntary, forced, trafficked, or undocumented—that have built our country and continue to power our workforce. To honor these contributions and the resilience of oppressed communities, I am committed to challenging labor inequities and dismantling oppressive systems every day.

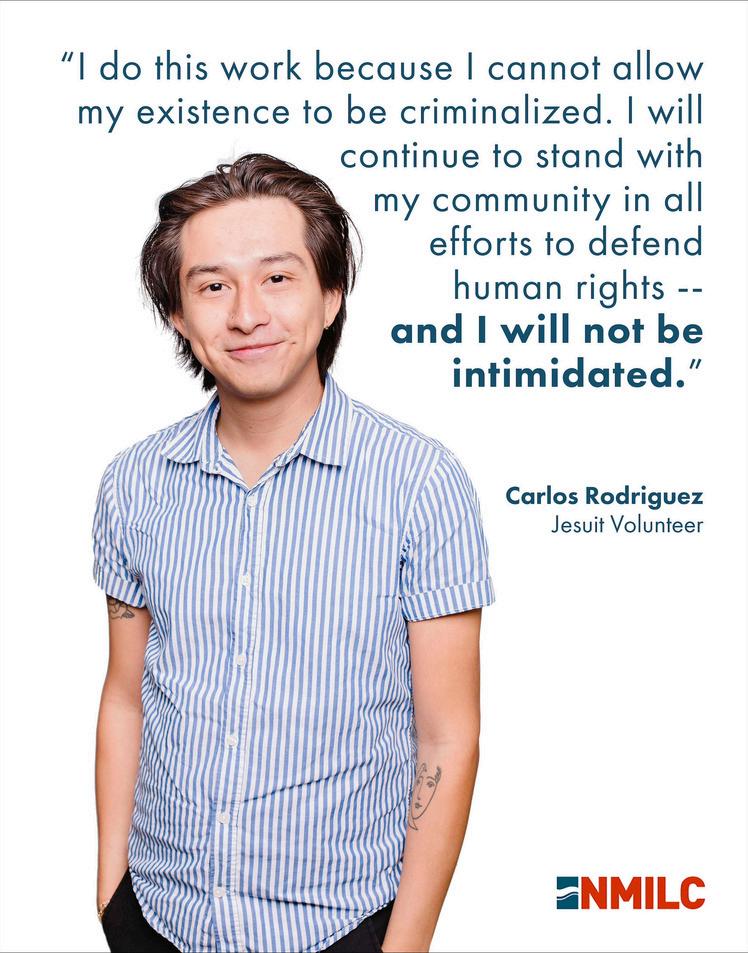

Carlos Rodriguez is a dedicated leader, educator, and advocate for social justice whose journey reflects a profound commitment to community engagement and transformative change. He earned a B.A. in Public Affairs from Seattle University, where he also served as Student Body President and passionately championed causes such as immigration and affordable housing policy. Furthering his academic pursuits, Carlos obtained an M.Ed. in Higher Education from Merrimack College, blending his academic insights with his real-world experiences as a former legal assistant.

His personal narrative as an undocumented immigrant, marked by the bold act of wearing a “scarlet U” to destigmatize undocumented status, underscores his relentless drive to empower marginalized communities. Carlos's service record is profound, having volunteered with the Jesuit Volunteer Corps for two years first in San Antonio, TX, where he specialized in antitrafficking and immigration legal aid, and then in Albuquerque, NM, assisting with asylum and detention legal matters inside immigration prisons. Currently, he serves as a Residence Hall Director at the University of Georgia, contributes to research at the Publicly Engaged Action and Research Lab, and lends his expertise with the Carnegie Elective Classification for Community Engagement, continuing to inspire change and advocate for a more just society.

In this session, participants will...

EXPLORE the specific challenges and stressors that undocumented individuals face in higher education and how these impact their overall well-being.

LEARN how joy can be used as a powerful form of resistance against systemic barriers, discrimination, and marginalization.

DEVELOP strategies for fostering positive and healthy environments that support the long-term well-being and success of undocumented students and staff.

An undocumented immigrant is a non-citizen residing in the U.S. without legal immigration status. This includes individuals who entered legally but overstayed, those who entered without inspection, and all immigrants who reside in the United States without legal status

Entered Without Inspection (also known as “EWI”)

Have or Previously Had DACA Vulnerable Immigrants Are Currently in the Process of Legalizing

Entered with Legal Status but Overstayed

Legal and Insitutional

Some public colleges and universities ban undocumented students from enrolling.limited scholarships

Varying state laws create uncertainty about rights and available opportunities.

Cultural

Lack of representation in higher education

Pressure to hide their undocumented status

Difficulty finding culturally competent resources

Campus Climate

Varying policies across institutions regarding undocumented student support

Lack of institutional knowledge and trained staff

Exclusionary admissions policies in certain states

Financial

Ineligibility for federal financial aid

Limited access to scholarships and in-state tuition

High cost of attending college without financial support

Psychological and Social

Fear of deportation and legal uncertainty

Isolation and lack of peer/community support

Mental health struggles due to chronic stress

Fear and Isolation

Students may avoid applying due to concerns about exposing their immigration status.

Students may feel disconnected from peers and hesitant to share their status

Access to Social Capital

Difficulty networking due to work restrictions

Limited mentorship opportunities

Lack of guidance on career pathways

AFrameworkforResistance&Empowerment

UndocuJoy is the act of celebrating life and identity despite systemic barriers. It reframes undocumented narratives from survival to thriving, centering joy as a powerful form of resistance.

Rooted in community, storytelling, and shared experiences

Provides emotional and psychological nourishment in oppressive spaces

Encourages undocumented individuals to embrace their full identities without fear

ALivedExperience-BasedPraxis

UndocuKnowledge is the pedagogy and practice that emerges from the lived experiences of undocumented individuals. It recognizes their unique wisdom and contributions to academia and advocacy.

Developed from the realities of being undocumented or formerly undocumented

A form of knowledge production that challenges traditional academic frameworks

Encourages institutions to value and integrate undocumented perspectives

UndocuJoy and UndocuKnowledge are deeply interconnected frameworks that empower undocumented individuals by shifting narratives from survival to thriving. UndocuJoy fosters emotional resilience and resistance, allowing undocumented individuals to reclaim their narratives through joy, storytelling, and community. UndocuKnowledge builds on these lived experiences, transforming them into pedagogical tools and institutional advocacy that challenge exclusionary structures in higher education.

Joy becomes a source of knowledge, and knowledge becomes a tool for liberation—together, they create sustainable empowerment for undocumented individuals in academia and beyond. By centering joy as resistance and lived experience as expertise, these frameworks work together to dismantle systemic barriers and create inclusive, affirming spaces in higher education.

Communityand Storytelling

UndocuJoy

Resistanceand Thriving

Emotional Nourishment

LivedExperience Praxis

UndocuKnowledge

Institutional Recognition

The term Juan Crow describes a system of laws, social norms, and institutional policies that marginalize and oppress undocumented immigrants, particularly in the United States. Coined by journalist Roberto Lovato, Juan Crow draws parallels to Jim Crow laws, which enforced racial segregation and disenfranchisement against Black Americans. Similarly, Juan Crow policies aim to exclude, control, and exploit undocumented immigrants through legal, economic, and social restrictions.

Juan Crow policies create systemic barriers that marginalize undocumented individuals, limiting their access to education, employment, healthcare, and legal protections. These policies foster economic exploitation, social exclusion, and psychological distress by instilling fear, restricting opportunities, and criminalizing immigration status. The long-term effects extend beyond individuals, impacting entire families and communities by reinforcing cycles of poverty and disenfranchisement. However, through resistance frameworks like UndocuJoy and UndocuKnowledge, undocumented communities reclaim their narratives, build resilience, and advocate for systemic change, challenging the oppressive structures that Juan Crow upholds.

While Juan Crow is a useful concept for understanding systemic oppression against undocumented immigrants, a more inclusive framework would need to address how race, legal status, and other intersecting identities shape different immigrant experiences. Broadening the discussion to include Black, Indigenous, and API immigrant struggles would provide a more holistic and intersectional approach to analyzing immigration injustice.

Safeand Inclusive Spaces

By implementing intentional policies and support structures, colleges and universities can create more inclusive, affirming, and empowering environments for undocumented students.

Creating dedicated resource centers or designated staff positions can provide undocumented students with critical support, mentorship, and advocacy. These spaces should offer confidential advising, peer mentorship, and community-building programs to help students navigate academic and personal challenges. Additionally, institutions should train faculty and staff on best practices for working with undocumented students, ensuring that confidentiality and cultural competency are prioritized.

TailoredHealth Services

Financialand Academic Support

Undocumented students often experience chronic stress, anxiety, and trauma due to immigration-related uncertainties. Colleges should offer counseling services with professionals trained in immigration-related mental health concerns and facilitate support groups where students can connect with peers facing similar challenges. In addition, wellness workshops and stressreduction programs tailored to undocumented students can help address their unique psychological needs and provide coping strategies.

Financial barriers are one of the greatest obstacles undocumented students face. Institutions should develop scholarships and emergency funds that do not require proof of legal status, ensuring students have access to financial aid. Academic policies should also be flexible, allowing undocumented students to take reduced course loads or access alternative funding sources without penalty. Advisors should receive training on guiding undocumented students through academic and career planning, particularly in navigating postgraduate opportunities.

Commuinty Buildingand Engagement

To create a more inclusive campus climate, institutions should celebrate and amplify the voices of undocumented students through programming, storytelling, and academic initiatives. Hosting events such as Undocumented Student Week of Action can increase awareness and foster solidarity across campus. Faculty can also play a role by integrating immigrant justice issues into curricula and recognizing undocumented scholars' contributions to research, teaching, and community engagement.

Inclusive Insititutional Policy Advocacy

Institutions must actively work to remove systemic barriers that prevent undocumented students from fully participating in higher education. This includes advocating for in-state tuition policies, ensuring undocumented students are not excluded from state financial aid, and eliminating unnecessary Social Security number requirements in applications. Schools can also partner with immigrant advocacy organizations to provide legal workshops, Know Your Rights training, and DACA renewal assistance to support students in navigating their legal options.

Supporting undocumented students requires more than symbolic gestures it demands concrete policies, financial investment, and a commitment to dismantling systemic barriers. By implementing these strategies, institutions can move beyond performative allyship

A“A” Number: An eight-digit number (or nine digits if the first number is a zero) beginning with the letter "A" that the DHS gives to some non-citizens (Note that Executive Office for Immigration Review now requires all A Numbers to be submitted as nine-digit numbers If the client’s A Number only has eight digits, add a “0” to the beginning of the number.)

Accompanied Minor: A child who has no lawful immigration status in the U.S., is younger than 18 years old, and is traveling with a lawfully admissible adult

Adjustment of Status: A process by which a non-citizen in the United States becomes a lawful permanent resident without having to leave the US

Asylum: A legal status granted to a person who has suffered harm or who fears harm because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

Asylee: A person who has been granted asylum in the US Immediately after obtaining asylum, asylees are authorized to work in the US, and one year later, an asylee can apply for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status Five years after being granted LPR status as a former asylee, the person can apply for citizenship.

Asylum Seeker: A person seeking asylum or refuge in the country in which they currently reside due to persecution faced in their native country Often people who apply for asylum at an airport or other point of entry into the United States are detained The difference between refugees and asylum seekers is that asylum seekers are physically present in the United States or at a U.S b d d ki i i i i h United States, while re nt in the U.S.

Change of Status: A change of status is when a non-citizen changes from one type or immigration status to a different form of immigration status

Child: An unmarried person under 21 years of age who is:

• A legitimated child.

• A stepchild.

• A child legitimated under the law of the child's residence or domicile or under the law of the father's residence or domicile.

• An illegitimate child

• A child adopted while under the age of 16

• A child who is an orphan

There is a significant amount of case law interpreting these categories

Citizen (USC): Any person born in the 50 United States, Guam, Puerto Rico, or the U.S. Virgin Islands, or a person who has naturalized to become a U.S. citizen. Some people born abroad are also citizens if their parents were citizens

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA): A form of temporary relief from deportation announced by the Obama Administration in July 2012 for certain young immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children and educated here. DACA grantees are eligible for work authorization.

DACAmented: An undocumented individual who meets requirements for Deferred Action for early Childhood Arrivals

DREAMER: An immigrant youth who qualifies for the Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act Dreamers are also frequently referred to as “DACA recipients”, though the latter specifically refers to Dreamers who have applied for and received DACA status.

Employment Authorization Document (EAD): The I-688 card (Green Card) that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issues to a person granted permission to work in the US The EAD is a plastic, wallet-sized card An EAD may be granted by DHS to many types of non-citizens and allows them to work legally in the U.S. for the period the EAD is valid. EADs can be regularly renewed in most cases.

Green Card: See Lawful Permanent Resident

I-94 card: A small white paper card issued by the DHS to most non-citizens who do not have Green Cards upon entry to the US It is usually stapled to a page of the non- citizen's passport The DHS may also issue I-94 cards in other circumstances The I-94 card usually states the date by which the noncitizen’s authorized stay in the US expires

Immigrant: A person who has the intention to reside permanently in the United States.

Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR): USCIS Form I-551 issued to non-citizens granted permanent residence It is also referred to as a Lawful Permanent Residency Card or Green Card. An LPR has been lawfully admitted to the U.S. for permanent residence. An immigrant can become a permanent resident in several different ways. Some individuals are sponsored by a family member or employer in the U.S. Other individuals may become LPRs through refugee or asylee status or other humanitarian programs Other individuals become LPRs following a grant of a U-Visa as a victim of a violent crime or a T-Visa as a victim of trafficking LPRs have essentially the same rights and obligations as US citizens with the exceptions of voting and holding certain public offices and civil service positions. However, LPRs can be detained or deported for certain offenses, including misdemeanors punishable by one or more years in jail. After five years (three years if obtained through marriage to a U.S. citizen), an LPR can apply for U.S. citizenship.

Migrant: A person who leaves their country of origin to seek temporary or permanent residence in another country

Mixed Immigration Status: An individual who is a US citizen or legal resident in the U.S., but other family members are not.

National of the United States: A citizen of the United States or a person who, although not a citizen of the US, owes permanent allegiance to the US Citizens of the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and the Territory of Guam are considered citizens of the United States American Samoa and Swains Island are “outlying possessions” of the United States, and their citizens are considered U.S. nationals and should be treated the same as citizens when determining residence for tuition purposes.

Non-Immigrant: A person admitted to the US for a temporary period and for a specific purpose

Notice of Action (Form I-797C): USCIS will send Form I-797C, Notice of Action, to an applicant/petitioner in order to communicate information related to notices of receipt, rejection, transfer, re-open, and appointment (fingerprint, biometric capture, interview, rescheduled).

OOut of Status: A former visa holder who violates their visa status by not following the visa requirement, staying longer than the expiration date of the visa and/or I-94, attaining age 21 (aging out), or engaging in activities not permitted for the visa.

Parolee: A non-citizen to whom the Attorney General has granted a temporary stay for humanitarian or public interest purposes and who can be detained at any time.

Parolee status usually expires after one year and is renewable at the U.S. government’s discretion

Refugee: A person who is granted permission to enter the US legally because of harm or feared harm due to his/her race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group Unlike an asylum applicant, a refugee must meet this definition while outside of the United States and enters the U.S. with refugee status. One year after arriving in the U.S., a refugee can apply to become a lawful permanent resident (LPR), and after five more years, can apply for U.S. citizenship.

Resident: A person who satisfies the requirements for residency for tuition purposes

Student: A person applying for admission, admitted to, or enrolled in an institution of higher education.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS): A status allowing residence and employment authorization to the nationals of foreign states for a period of not less than 6 months or more than 18 months, when such state (or states) has been appropriately designated by the Attorney General because of extraordinary and temporary conditions in such state (or states)

Undocumented Immigrant: A non-citizen who is residing in the US without legal immigration status Undocumented persons include those who originally entered the US legally for a temporary stay and overstayed or worked without DHS permission, and those who entered without inspection

USCIS: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services is the bureau within DHS that administers applications for immigration benefits such as visas, adjustment of status, and naturalization. The USCIS Asylum Officer Corps makes decisions on affirmative asylum claims

Aguilar.C.(2018).UndocumentedCriticalTheoryinEducation.CulturalStudies-CriticalMethodologies, 19(3),149-163.

Borg,N A (2024) “WorkoftheHeart”:LivedExperiencesofUndocumentedStudentResourceCenter Professionals(Doctoraldissertation,BostonCollege)

Blow,D (2024) ImmigrantDayofResiliencePostcard UnitedWeDream https://unitedwedream.org/immigrant-day-of-resilience/ Calderon,E.(n.d.).Undocujoy:AFormerUndocumentedGirlExperiencingJoy.Blog. https://undocujoy.home.blog

Dinh,T.(2024). ImmigrantDayofResiliencePostcard.UnitedWeDream. https://unitedwedream.org/immigrant-day-of-resilience/ ImmigrantsRising(2023).DefiningUndocumented.Immigrants Risinghttps://immigrantsrisingorg/resource/defining-undocumented/ CornejoVillavicencio,K (2020) TheundocumentedAmericans Firstedition OneWorld Lovato,R (2008) JuanCrowinGeorgia TheNation https://wwwthenationcom/article/archive/juan-crow-georgia/ Love,B.L.(2019). Wewanttodomorethantosurvive:Abolitionistteachingandthepursuitof educationalfreedom.BeaconPress.

Martinez,R.(2024).Partyingaspolitical.Illegalized:UndocumentedYouthMovementsintheUnited States,132.UniversityofArizonaPress.

Mignolo,W.(2000).ThemanyFacesofCosmo-polis.BorderThinkingandCriticalCosmopolitanism. PublicCulture.DukeUniversityPress.

Patton,L D,Renn,K A,Guido,F M,&Quaye,S J (2016) Studentdevelopmentincollege:Theory, research,andpractice(3rded) Jossey-Bass/Wiley

Peña,Z (nd) TeachingWhileUndocumented RethinkingSchools https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/teaching-while-undocumented/ Reyes,Y.(2017).UndocuJoy:AloveLettertoMyUndocumentedPeople.DefineAmerican.[Youtube video].https://youtu.be/O6BR352wuPY?si=yOOohBlJWf5ZOimS Rodriguez,F.(2012).StopJuanCrow.https://favianna.com/artworks/stop-juan-crow Rosas,K.(2020).RadicalAcquisitions:CarvingSpacesforQueerUndocumentedArtistsattheHood Museum.HoodMuseumofArt.

Santa-Ramirez,S,Hall,KA (2023) UndocuJoyasresistance:BeyondGloomandDoom Narrativesof UndocumentedCollegians JournalofCollegeStudentDevelopment JohnHopkinsUniversityPress

Salgado,J (2015) JulioSalgadoArt https://wwwjuliosalgadoartcom

Salgado,J.(2022).JulioSalgadoArt.https://www.juliosalgadoart.com

Shelton,L.J.(2018).“WhoBelongs”:ACriticalRaceTheoryandLatinoCriticalTheoryAnalysisofthe UnitedStatesImmigrationClimateforUndocumentedLatinxCollegeStudents.JournalofCritical ThoughandPraxis.IowaStateUniversity.

Tichavakunda,A.A.(2021).Blackjoyonwhitecampuses:Exploringblackstudents’recreationand celebrationatahistoricallywhiteinstitution.TheReviewofHigherEducation,44,297-324.

Williams,BM,&McCloud,l (2023) “JustBreathe”:BlackWomenfacultynegotiatingjoyandhopein academia TheVermontConnection,44(1),237-250

I extend my deepest gratitude to undocumented students, activists, and community leaders - mi familia - whose resilience, joy, and advocacy continue to push for systemic change. Your perseverance and commitment to a better future inspire this work.

I also acknowledge the educators, allies, and institutions working to create inclusive spaces where undocumented students feel valued and supported. Through policy, advocacy, and direct action, you help UndocuJoy flourish.

I recognize the Indigenous communities on whose land our institutions exist, reminding us that borders are colonial constructs and that many undocumented individuals have ancestral ties to these lands long before modern immigration policies.

We must also honor those who have lost their lives at the hands of migration, ICE, immigration jails, and customs and border patrol. Their names, stories, and dreams should never be forgotten. May we carry their memory forward as we fight for a world where no one is criminalized for seeking safety and belonging.

Que descansen en poder.