THE RETURN OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG

PART FOUR OF A FOUR PART SERIES

As our centennial celebration of Louis Armstrong’s arrival in Chicago ramps up this summer, we offer you a four part series on jazz starting pre-Louis through his profound impact on the art. No story on the Louis in Chicago could be complete without discussing the role of Lil Hardin Armstrong. A gifted and talented pianist and writer, she married Louis in Chicago and helped him develop into an international superstar.

By Howard Mandel

By Howard Mandel

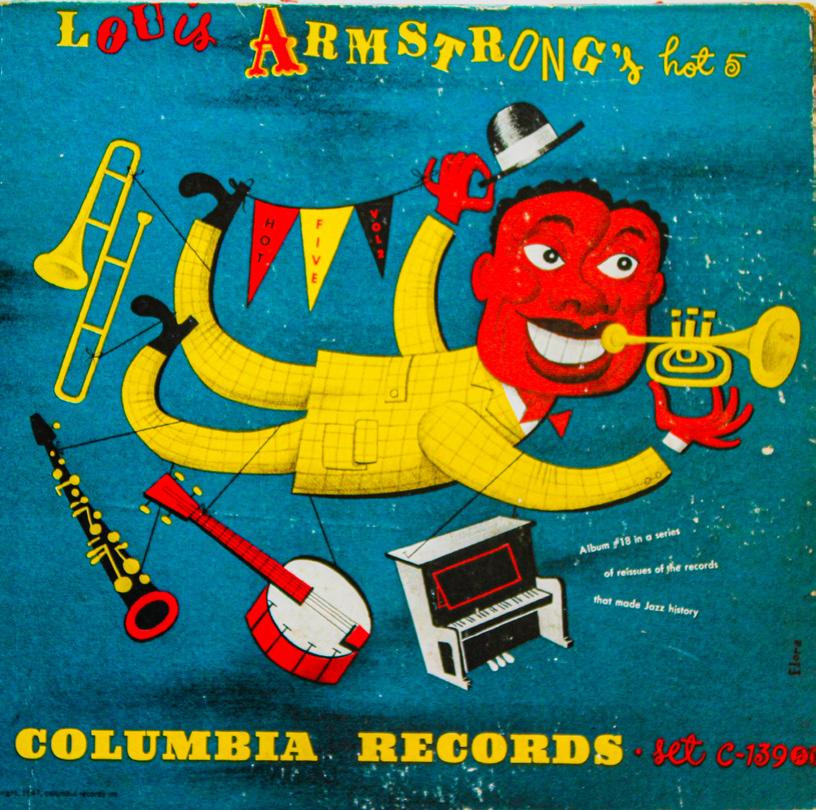

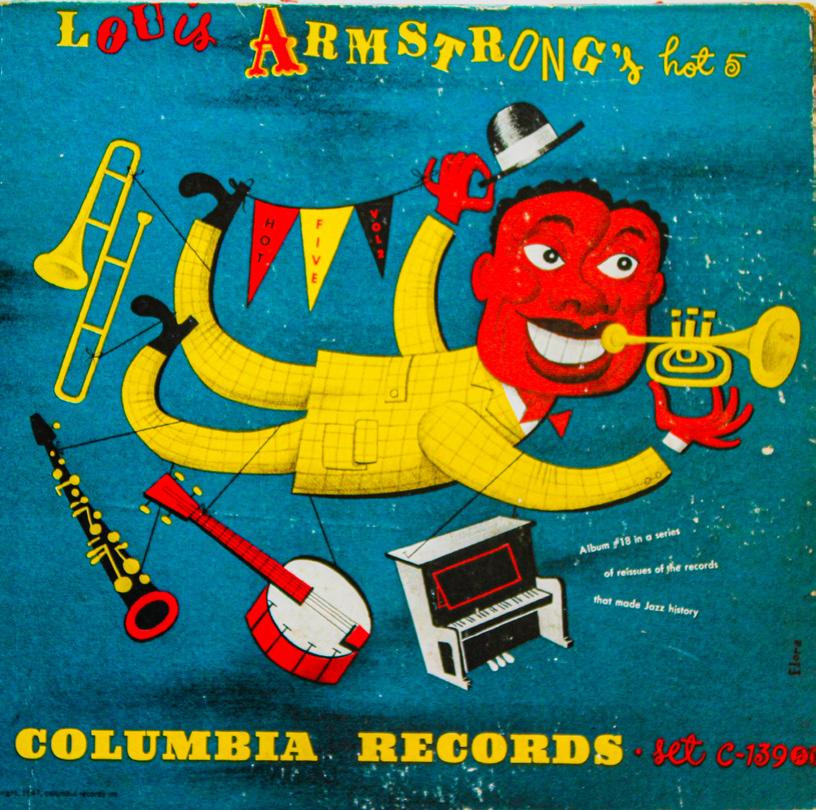

When Louis Armstrong returned to Chicago in 1925 after his influential but less-than-a-year stint in New York City with Fletcher Henderson, Lil Hardin had plans for him. She intended him to be a well-paid star and recording artist. Louis was not happy with her billing him as “the World’s Greatest Trumpet Player,”

but the reactions of audiences, the loy alty of the players originally from New Orleans with whom he worked, and the interests of other, younger musicians in what he was doing stilled his concerns. So, upon re-establishing himself in the Windy City he solidified his ensemble and doubled down on his unique, per sonal direction for new music. With

trombonist Kid Ory, clarinetist Johnny Dodds, banjo-player Johnny St. Cyr and Lil on piano, Louis recorded 24 sides in the next 12 months, including imper ishable songs like “Cornet Chop Suey,” demonstrating his virtuosity, wit, swing and warmth; “Potato Head Blues,” refin ing the stop-time format Jelly Roll Mor ton had used for “breaks”; the erotically

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO NOVEMBER 2022 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued on page 2

Earl Hines (piano) and Louis Armstrong (trumpet) at a 1948 jam session in Rome. They're joined by Jack Teagarden (trombone) and a host of local artists.

suggestive “Hot Like This,” and “Heebie Jeebies,” the first on which Armstrong improvised a vocal part (inspiring the wordless style to be known as “scat singing”).

In 1927 the Hot Five recorded Lil Har din’s composition “Struttin’ with Some Barbeque,” among eight more pieces. Following the template of Johnny Dodd’s Octet, they became the Hot Seven with the addition of drummer Warren “Baby” Dodds (Johnny’s brother) and tuba play er Pete Briggs, and as such (with John Thomas subbing for Kid Ory), waxed another 21 tracks. Arm strong reduced the group to five members again in ’28, having re placed Lil -- from whom he’d sepa rated; both were involved with oth er lovers – with pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines. However, she continued to write and arrange for the band.

Hines, a 21-year-old prodigy born and raised near Pittsburgh, met Armstrong, three years his senior, play ing pool at the Black Musicians’ Union, which had offices at 39th and State Street. The two men shared interests in expanding their instruments’ possibili ties (or at least showing what they could do.) They became friends and the sort of collaborators who enrich each others’ efforts. Their Hot Seven sessions pro duced two songs in particular regarded as timeless examples of jazz excellence: “West End Blues” and the brilliant duet “Weather Bird.”

Armstrong was astonished by Hines’ “trumpet style,” which emphasized mel ody lines by playing them in right hand octaves (that is, two pitches the same, simultaneously,12 steps apart). Hines had superior technique, and an unusual grasp of time – as did Armstrong. Their collaboration is interpreted as putting a capstone on the first decade of recorded jazz. Although both their careers contin ued for decades, the music in their future left the old ways behind.

Armstrong had changed jazz immea surably since the day he’d joined King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. His example set a standard really for all improvising soloists, and his groups showed how an individual’s sounds could better support and interact cohesively, across an ar ray of feelings (all, by the way, inflected

ers, including Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, who would be responsible for jazz’s next generational reformation. By1929, Louis Armstrong had enjoyed exposure to several notable pianists -besides Lil Hardin, Fletcher Henderson and “Fatha Hines,” the early composer/ promoter/bandleader Clarence Williams (with whom Armstrong met and recorded with his one true New Orleans-born peer, clarinetist and saxophonist Sidney Bechet).

In New City he scored a break through in the Black-cast “Hot Chocoalates” revue, coming on stage from the pitband to shine in his singing and playing of “Ain’t Misbehavin’”. The recording became his best seller.

with the blues). Rhythms became more distinct (thanks in large part to Baby Dodds, who essentially codified the makeup of the modern drum kit, adapt ing New Orleans marching band snares, bass and cymbals for one person to play) and gained the revolutionary loose momentum known as “swing.”

As for Hines, he should also be cel ebrated as a stalwart of Chicago’s 20th century culture. On December 28, 1928 (according to Wikipedia, his 25th birth day), he opened at the Grand Terrace Ballroom, a venue belonging to then gangster Al Capone, with his own band – an orchestra that in time grew to com prise more than two dozen musicians, playing multiple shows nightly, for 12 years. Throughout the Great Depression, Hines’ orchestra -- a hard-driving big band with sophisticated arrangements and solid repertoire -- was frequently broadcast coast-to-coast, advancing new styles while serving as a proving ground or finishing school for up ‘n’ com

Louis Armstrong had an unusual voice, for sure – both raspy and syrupy, his precise diction as sa tiric as his exaggerated drawl –that was just right for the times. His voice, like the man himself, was not something artfully pre tentious, but rather realistic and recog nizable by people across many social strata. Remember: He had recorded with Bessie Smith, Empress of the Blues, as well as “classic blues” singers Sippi Wal lace and Adelaide Hall; befriended song writer Hoagy Carmichael and had a big fan in Bing Crosby. His personality was bountiful, as big as his smile, busting out all over, hard to limit to the horn. Holly wood called, and touring – he would be in such demand and energized enough to do as many as 300 shows a year. So, Louis Armstrong left Chicago, but Chi cago never left Louis Armstrong.

Louis Armstrong: The Complete Hot Fives and Sevens Recordings are available as a CD box set from Columbia Legacy, com plete with informative liner notes, rare photos and recordings Armstrong made with other groups during this time period. A single CD of highlights is also available.

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 2 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued from page 1, Louis Armstrong

IN MEMORIAM

RUBÉN P. ALVAREZ,

For over 30 years, Rubén P. Alvarez’s shared the knowledge he embodied on the cultural aspects of his heritage and Latin Jazz with numerous students and the many teachers with whom he worked. He believed that understand ing music was a key, important and necessary element in the rhythm of life and the development of the human spirit. He understood that through mu sic, all are connected by a higher prin ciple that transcended our differences. Rubén P. Alvarez served as a faculty member of the Jazz Institute’s Jazz Links Master Residency Artist and Pro fessional Staff Development Program for over a decade.

We were very fortunate to have had such a dedicated and skilled Latin percussionist, drum set artist, com poser, and music educator in our midst. Rubén made sure that every moment of his life was fulfilled with the things he held most dear. His lifelong work included: being a 13th Annual Latin Grammy nominee for his work on the Chuchito Valdés CD, “Made in Chicago”. His musical theatre credits included being percussionist and mu sical consultant for the Goodman The atre Production, Crowns, the Broadway Chicago productions of The Lion King, and On your Feet. His performance and recording credits included: blues artists, John Mayall and Junior Wells, rock artists Dave Mason and Dennis De Young, and jazz artists Arturo San doval, Ramsey Lewis, Patricia Barber, Dave Valentín, Slide Hampton, and Roy Hargrove, the Chicago-based 2010 Grammy and Latin Grammy nominees Sones De Mexico Ensemble, pop-diva Jennifer Hudson and the “Queen of Soul” Aretha Franklin. Rubén was also a member of Chévere De Chicago and led the Raices Profundas Latin Jazz En semble.

At the University level, Rubén taught

NOVEMBER 20, 1951 – SEPTEMBER 25, 2022

drum set and Latin percussion, and di rected Latin music ensembles at Roos evelt University, Columbia College Chi cago, and Prairie State College.

Rubén’s commitment to serving the jazz and music education communi ties, involved his serving as a founding member and on the Board of Direc tors for The Jazz Education Network, the Board of Governors of the Chicago Chapter of the Recording Academy, Vice President of the Illinois Chapter of the Percussive Arts Society, and the Board of the World Percussion Com

mittee of the Percussive Arts Society. In 2018 Rubén received the Educator of the Year Award at the “Celebrate the Power” Jazz Appreciation Month event hosted by the Jazz Institute’s Education Committee. As we sway to a funky Cuban Cha Cha (as he would note) or clap our hands to an upbeat drum rhythm -We will think of him! As he now rightfully takes his seat amongst the Ancestors - His dedication, sincerity, musicality, sense of humor, and love of humanity will for ever be missed - but never forgotten.

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 3 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

Rubén P. Alvarez

KELLY SILL’S MUSICALITY, INTENSITY, AND SINCERITY CELEBRATED

By Corey Hall

Kelly Sill at The Jazz Showcase

For fifty-two seconds, even silence stood still after Wayne Shorter’s “Infant Eyes” ended. This song, played from a CD brought by Jeff Stitely, had just flowed through the speakers at the Jazz Showcase in the drummer’s attempt to establish healing, meditative moments for “Kelly Sill: A Celebration of Life.” Sill, whose bass, pedagogy, and personal ity inspired, intimidated, and intrigued many during his four decades on Chi cago’s jazz scene, died on September 28 at age seventy. “Infant Eyes,” Stitely noted, had been cited by Sill as a per fect composition and personal favorite. Stitely, the celebration’s host, spoke, even when pain caused his voice to rise to resist breaking apart. Before him,

mounted on an easel, stood a blackand-white photograph of Sill, hands carefully clutching his instrument, staring into the camera through everpresent spectacles, shoulder-length hair combed and cascading just right. Complementing this photograph were roses intertwined with a replica bass.

Sill, born in Fargo, North Dakota, on March 2, 1952, possessed prodigious recording and live experience credits with John Campbell, Jackie McLean, Anita O’Day, Mose Allison, and goo gobs more.

Before yielding the microphone to the celebration’s featured celebrants – Art Davis, Naomi Sill, Mark Sonksen, Brad

Goode, and John Lawler – Stitely ad dressed the remorse he and other peo ple present were experiencing about not having contacted Sill as his health eroded.

“The person you were in his life, and he was in our lives, is really what it’s about, not something we didn’t do,” he said. “Let’s have this be a sacred place of forgiveness for those thoughts and those of you having those thoughts.”

Trumpeter Art Davis – whose friend ship with Sill began fifty-two years ago at U. of I-Champaign – admired Sill’s tastes, which included everyone in Miles’ late ‘60s quintet, to Rach maninoff, to saxophonist Scott Hamil

PAGE 4

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO

JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO

ton. Davis also recalled what Sill said about his life’s purpose.

“He said, ‘I came here’ – and I now know he meant this planet, this plane of existence – ‘to help people,’ ” Da vis recalled. “And I thought, ‘Wow. He didn’t say, ‘I came here to be a bass player, a great musician or composer.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, Kel. That’s probably the most important thing you’ve done.’

”Naomi Sill, -- “Kel” and Kelly (Brand’s) daughter -- discussed her dad’s sen sitivity, spirituality, and ever-present support. Naomi recalled sitting with her parents outside their home, playing frisbee, and getting destroyed by Da vis in Scrabble. She also remembered the deep discussions she had with her father about how the communications between mind and body were so im portant.

“My dad taught me that it was okay to feel anything and everything,” Naomi said. “He told me that was the reason we were alive. We want to give love. We want to receive love.

“He taught me to not even think bad thoughts about other human beings,” she continued, “because our thoughts matter. Our thoughts could manifest, and I thought that was really powerful.”

Mark Sonksen, trusted by Sill to per form maintenance on his axes, remem bered how his friend since the early 1990s said that playing music made life beautiful and worth living. Sonksen also recalled Sill’s response to a listener who, after a performance, said he loved music and wished he had kept playing.

“Without missing a beat, Kelly simply looked at him, smiled, and said, ‘No you don’t. If you really wanted to play, you would have played,’” Sonksen stated. “That’s the Kel we all know and loved… and now he’s with the ancestors.”

Trumpeter Brad Goode recalled pre senting his concept for an ensemble that would play original, unorthodox arrangements. Would Sill participate? “Brad, you have called the right person, and I will make this work,” Goode re called being told. Sill would then play in Goode’s ensembles for the next twen ty-five years.

Goode’s Kelly story detailed what hap pened after the sessions for That’s Right, his 2018 album. Sill’s enthusiasm about the music led him to demand involvement in its post-production. “I need to be there mixing with you,” Sill said, “and you really need to have me there.” Then, two days later, Sill called Goode at his home in Colorado and repeated his request. He added that purchasing a plane ticket for him to attend would be a good idea. Goode responded as requested.

On day one, Goode and the engineer heard Sill say, “This sounds really good.” Other than those five syllables, stated intermittently, Sill stayed silent. On day two, Sill emerged from his shell when the playback for “A Sense of Fair ness,” his composition, happened.

“He said to the engineer, ‘Let me hear that bass solo again,’” Goode recalled. Sill listened and then repeated his re quest. “Then Kelly said, ‘Just play that one lick!’ Then Kelly looked at me and said, ‘I can’t play that! Play it again!’ That was Kelly’s contribution to the mix.”

Sill, the guru, was also celebrated by mentee, bassist John Lawler. Before Lawler bombed an audition in 2010 at DePaul University, he had been told by Sill in his campus office to write down his number and remain in touch. After Lawler’s failures were confirmed, he connected with Sill and began weekly lessons.

“You never took the bass out of the

case at his house,” Lawler said. “He would always be sitting down at the piano talking music. It was really about your understanding of what you were hearing and whether or not you were grasping it.”

Sill’s intensity about humor never fad ed, Lawler continued. “Even when he was going to the darkest places in his life, he would call me up to tell a joke just so that he knew he could tell that joke.

“Know that Kelly would tell you this,” Lawler said. “Don’t lose your sense of humor, because it is the one defining human characteristic that will set you above and beyond everyone else.”

When Stitely returned to conclude the celebration’s spoken set, he expressed regret that a death had to happen for these stories to be told. “We should have had this party with Kelly,” he said. He then shared something that Sill told him while they discussed their motiva tions for playing music. “He said, ‘I play for the music that’s in the moment. Then I play for God, and then I play for the people in the room. Myself is last.’ That really made me think.”

Stitely then yielded the stage to two ensembles led by Goode, saxophonist Geof Bradfield, and pianist Dennis Lux ion. The ensembles performed two Sill originals: “Naomi” and “Ironic Line.” For the jam session that followed, led by saxophonist Eric Schneider, Stitely let everyone know Kelly’s Rules of Con duct for such sessions. The first?

“Three horn players on the stage, max!” he began, as the attendees in the packed venue laughed, in remem brance or regret. And the second? “When a tune is called, if you’re not sure of the melody and start playing it…you’re out! All of Kelly’s particles are going to come here, reform, and give you the stink eye!”

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 5 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

LINDA MAY HAN OH EXAMINES THE SUBSTANCE, SUSTAINABILITY, AND SACREDNESS OF LIFE

By Corey Hall

Return to your past. Now, isolate your present, or conjure your future and en vision a child’s eyes opening to view everything new that day may deliver. And then…

Journey to a place where infinite spac es further your awareness, causing you to see/seize that moment where you accept your in clusion into this just realized reality, one inherently and forever larger than you…

These totally imagined, total ly true visions form the foun dation for “Aventurine,” the title track to Linda May Han Oh’s fifth album. Oh – whose quartet, alto saxophonist Greg Ward, pianist Fabian Almazan, and drummer Eric Doob performed at the 2022 Chicago Jazz Festival – re cently dialogued with the JazzGram about Aventurine, the creation and the object.

lusion,” another jazz and string quartet adventure, to be her catalyst.

“What I tried to do was have these in terjecting moments of somewhat re petitive sections with strings interject ing with Matt, the soloist,” said Oh, who also described her song as an optical

“With ‘Deepsea Dancers,’ ” Oh ex plained, “I tried to capture one long string of melody in one tonality with some other colors added, like a little brushstroke.”

While challenging, Oh’s arrangements are logical and differ from traditional ways that song and solo structures exist, said Greg Ward. “Deepsea Dancers,” he added, has a novel and complex approach.

“The soloist improvises on top of the melody, while ev eryone else continues play ing that melody,” Ward said. “That soloist goes one time through, and the next person picks up where the previous one left off, so there is a dia logue happening. It’s like a continuous solo. The idea is to communicate an entire story, or a complete solo, in side the ensemble together.”

Linda May Han

“A lot of pieces on Aventu rine were a slow burn over the past 10 years of reshaping and re working these compositions,” said the Malaysia-born bassist/vocalist. “It was staggered in a sense that each piece was from a slightly different era. It sym bolized an evolution within my past.”

By definition, aventurine is “an opaque, brown glass containing fine, gold-col ored particles” (dictionary.com). Said Oh: “It is usually green, sometimes yellow, and sometimes other shades. What sets it apart is that people often confuse it with jade. What also sets it apart is this thing called aventures cence, which has this sparkly, shim mering quality, and that’s definitely something I tried to capture with the strings, particularly on the title track.”

Aventurine’s personnel includes a jazz quartet, with Ward, pianist Matt Mitchell, and drummer Ches Smith, augmented on select tracks by a string quartet and Invenio, a five-member choir.

When uniting both quartets on “Lilac Chaser,” Oh allowed the enjoyment she received from pianist Andrew Hill’s “Il

illusion. “It was almost like a question and answer. I wanted something quirky and left of center.”

For “Rest Your Weary Head (Part One and Part Two),” Invenio’s presence is added for color and atmosphere.

“Part one is a strange sort of lullaby that came to me when my niece, Lia, was just born. She was crying, and I was trying to lull her to sleep,” Oh re called. “The second part is more of a trance, with the repetitive minimalism and the push and pull between the choir and the band.”

Oh also discussed “Deepsea Dancers,” which first appeared on her previous recording, Walk Against Wind. This song honors Izumi Uchida, her former manager, who suffered a fatal brain aneurysm. Thanks to Uchida’s encour agement, Oh started exploring Asian music and collaborating with Korean and Japanese musicians. A trip to Bei jing, where she learned about Chinese melodies and storytelling, also helped.

Ward also enjoyed blow ing his musical brains out on Oh’s arrangement of Bird’s “Au Pri vave.” “When you listen to it, it’s hard to tell that that’s actually the tune,” he said. “It was that tune, though, very much slowed down. It was a very fun arrangement to play.”

Oh and her quartet will return to Chi cago for a hit at the Logan Center on April 15, 2023. The quartet will be play ing music from Oh’s The Glass Hours, her next album. This will be her third release on Biophilia Records, owned by Fabian Almazan, her husband. Biophil ia, she explained, is guided by sustain ability and environmental awareness.

“We don’t sell CDs, because we don’t want to sell anything with plastic in it,” she said. “Instead, we have FSC-certi fied paper bifolios, and you still get 24 panels of artwork and liner notes. And all the inks are vegetable-based.”

When discussing The Glass Hours, Oh explained it like this: “It is a collection of works about the fragility of time and life, and what we choose to do with the hours we have together.”

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 6 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM PARKER

Interviewed by Wanjiku Kairu

William Parker is a bassist, improviser, composer, writer, and educator from New York City, heralded by The Village Voice as, “the most consistently brilliant free jazz bassist of all time.”

In addition to recording over 150 al bums, he has published six books and taught and mentored hundreds of young musicians and artists.

Mr. Parker performed at the 2022 Chi cago Jazz Festival and our Wanjiku Kai ru had the great pleasure of interview ing a few days before his performance. Here is a transcript of that interview.

Wanjiku Kairu: Hey, I'm Wanjiku Kairu with the Chicago Jazz Festival and the Jazz Institute of Chicago, and today we're talking with William Parker. Wil

liam, how are you doing today?

William Parker: I'm doing great, great, great. It's a little hot here in New York, but I'm doing great. Beautiful morning. And every day is, when you can see the sky and the sunshine, and hear, and fil ter this music that's going through you is a great day. And wonderful people.

Wanjiku Kairu: Oh, that's beautiful. Yeah. I know you're out in New York. It must be great over there. We have a lot of artists coming in from New York this year.

William Parker: Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

Wanjiku Kairu: So tell us about the work that you're performing. What has

been your inspiration for your perfor mance?

William Parker: Well, what we're do ing is a suite of several pieces, some new and some older pieces. And the inspiration is about what's gone. Peo ple like Fred Anderson who ran The Velvet Lounge, we have a piece for him called What You Got For Me To day. And because every time I visited Fred, I would come in from New York and he'd be down practicing. And I'd always tell him stories. I'm like a sto ryteller. And so, I'd tell Fred what was going on with his worthy constituent Kalaparusa, Maurice McIntyre, or what the guys from Chicago were doing in New York that he didn't know about. So he'd always say... So that's like a

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 7 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued on page 8

“ALWAYS DRAMA GROWING UP IN NEW YORK. AND I GUESS THAT HAS PUT IN A LITTLE PUSH IN THE MUSIC AND THE CREATIVITY, IS TO HAVE THIS DRAMA INVOLVED.”

William Parker

rousing boom piece. And then we're doing a piece called Wood Flute Song, which is dedicated to Don Sherry, a guy I played with 1975. We did a week at the Five Spot. And I knew him since like '74 and just a great musician, trum pet player. And he'd always have some wood flutes, introduced me to the in strument the Ducengoney from Molly. And probably, an exponent to bring ing the idea of world music, which is basically music from around the world. So that piece is going to be included. Then, we're doing a piece called Huey's Sunset, which is in seven four, which deals with my fictional character, Huey Jackson, who was an embodiment of hope for little kids. He lives in the Bronx where I was born, and he's actually me actually, and he wanted to be a poet. But everybody was telling him, "Huey, you got to work for the post office. You got to get a real job." And Huey would say, "No, I want to be a poet." And so we eventually saw that little Huey cre ated music orchestra to bring this idea of hope to all the little kids who live in the projects in the projects, in the Bronx. So we'll be doing that and some other pieces with organ. Mr. Cooper Moore playing organ. Drake, who lives in Chicago, trap drums, raw brown alto sax, and James Brandon Lewis Turner saxophone.

Wanjiku Kairu: Awesome. It sounds like you have a great mix of perform ers today. Now, you're from the Bronx. How has New York influenced... How has that New York influence played a hand in your development as an artist?

William Parker: Well, it's hard to say. When you are born in New York and you're in the middle of it, in the middle of the fire, you don't notice the flames. So people always say New York has this energy, and to me it's just New York. But I can imagine someone com ing from a small town, and coming to New York, and seeing all the buildings, and seeing these people, and all the hustle and bustle. So that energy is in you. And we are right in the urban cha os and drama. There's always drama. It

was always drama growing up in New York. And I guess that has put in a little push in the music and the creativity, is to have this drama involved. So it's been great. And then we travel, and luckily we're able to travel, around the world now and play music. It's great.

Wanjiku Kairu: Nice. That's awesome. New York is one of the most coura geous cities out there. I'm originally from New Jersey.

William Parker: Oh, okay.

Wanjiku Kairu: Yeah. I'm so excited to see all these different influences come into play. That'll be really great. So you have such a full career. You've accom plished so much. You've received the Doris Duke Performing Arts Award and the Village Voice has called you the most consistently brilliant free jazz basest of all time. What has been your greatest achievement so far?

William Parker: My greatest achieve ment is every day when I wake up and can play music, is my greatest achieve ment. And meet wonderful people like you and others, and the gentleman sit ting in my kitchen. The achievement is to be alive and to be able to play, and to continue to get into the middle of your imagination. Creativity, imagination, imagination, into activation. And you activate and then you create. You're able to create and things come through you. So I think... And you never know what's going to happen, who's the next person to walk through the door or you'll meet in the street. That's why you have to stay open to all possibilities. You never know.

Wanjiku Kairu: So you seem like a man of the elements. What is your fa vorite weather to create music in? I'm sure you've never gotten that question before.

William Parker: I've never gotten that question. When I was a kid, I used to like the rainy days because I would sit in the house and listen to Randy Weston.

And listen to one track called Portrait of Vivian, his mother, and I had listen to one track over and over again. And somehow again that activated the cre ativity in me to look out into the clouds, look out into the rain, hear the dripping of water on the leaves. So rain symbols, rain drums, or the idea give you visions like, okay, let's tie a drum set to a tree. And then have the wind blow through the drum set and have the leaves be the brushes. So all this stuff came to me when I was a kid. Or tie a saxo phone up to a tree and have it the wind blow through it. And I was convinced that if the wind blew through it, it would not sound like Charlie Parker. It would sound a little different.

Wanjiku Kairu: Yeah. Nice, nice. That's so funny. For me, when it rains, I always think it's such an emotional cleanser for me because for me, if it's raining outside then I don't have any room to be sad because it's already raining out there. So I have no choice to but to be having a good time. All right, so is there anyone that you are really excited to check out this weekend?

William Parker: Well, we arrive on the second. And we get out there, I'm not even sure the schedule. So I would've liked to, I think Henry Threadgill is playing on the first. I would've liked to check him out. But we're going to still be in New York on the first. But Carmen Lundy plays before us, I believe. And Miguel Zenon plays, so I like to check out as much music as I can check out because in New York you're too busy being in New York sometimes to hear music. But on the road, you meet people at the airport and it's good to check out and listen to people when it's not a memorial. See musicians gather when someone dies. And so let's gath er when something is being born, like some music.

Wanjiku Kairu: Nice. That's awesome. It's been so great speaking with you to day.

William Parker: Thank you.

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 8 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued from page 7, William Parker

THE 4TH ANNUAL JAZZ IN THE CHI

Registration is open for The Jazz in the Chi/Regional Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Festival!

Jazz bands from Chicago region and beyond are welcome! The 2022 festi val was limited to CPS schools due to pandemic-related protocols, but we are happy to invite all schools participate again!

The annual festival returns to Whitney Young High School on February 18, 2023. Jazz bands from elementary, mid

dle and high schools may apply, how ever only high school big bands can perform before and receive clinics from adjudicators representing Essentially Ellington provided by Jazz at Lincoln Center. All other ensembles will receive post-performance clinics lead by excel lent local jazz artist and educators. Jazz in the Chi is more than the perfor mances and clinics. Band directors will enjoy a special luncheon with the Es sentially Ellington clinicians while stu dents witness a special performance with a guest artist. All participants can

LET FREEDOM SWING RETURNS

The Jazz Institute of Chicago is happy to partner with Jazz at Lincoln Center to bring forth another year of Let Freedom Swing. This program provides a series free jazz concerts at Chicago elemen tary schools to expose young students to jazz, artists and the legacy of the music contextualized within our shared culture and history.

Born during the pandemic as a way to bring jazz to the schools in their outdoor spaces, the program now features in door or outdoor shows as weather per mits (indoors during Chicago winters for sure!). In the 2022-2023 school year, Let Freedom Swing is planning 60 perfor mances at schools around the city with high minority populations and in low-

take part in a vendor fair with repre sentatives from colleges, universities, arts organizations and local music mer chants. Jam sessions, opportunities to observe jazz bands perform and more make for a great day of networking with other jazz lovers and learners.

Registration for The Jazz in the Chi/Re gional Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Festival is open until Decem ber 12th, 2022. Don’t miss out! Find out more at: jazzinchicago.org/educationprograms.

Jazz Links Jam Sessions are back at the Jazz Showcase! Thanks to everyone who came out and made the first jam session of the season in October a suc cess! The jams at the Jazz Showcase provide a great environment for young

musicians to learn and improve their jazz chops, lead by our house band of performer/educators.

The next jam session is Wednesday, No vember 9th 2022 and they will continue

income areas. The performances are not open to the public, though if they take place outside in the school yard, anyone nearby can hear them. JIC looks forward, however, to this expanded season of the program; inspiring tomorrow’s artists and jazz fans at a school near you!

on the second Wednesdays of each month through spring 2023. Come out again and support live jazz and our young players!

JAZZ IN CHICAGO EDUCATION CORNER PAGE 9 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

JAM ON!

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 10 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 11 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

The JazzGram is a monthly newsletter published by the Jazz Institute of Chicago for its members. The Jazzgram represents the views of the authors, and unless so designated, does not reflect official policy of the Jazz Institute. We welcome news and articles with differing opinions.

Design: YoojDesign

Correspondents: Diane Chandler-Marshall, Aaron Cohen, Corey Hall, Ayana Contreras, Howard Mandel, Rahsaan Clark Morris, Neil Tesser.

Board of Directors: President: David Helverson

Vice Presidents: Timuel Black In Memoriam, David Bloomberg, Warren Chapman, William Norris, Keyonn Pope, Kent Rich mond, DV Williams.

Secretary: Howard Mandel

Treasurer: Brian Myerholtz

Emeritus Director: Joseph B. Glossberg

Executive Director: Heather Ireland Robinson

Board Members: Miguel de la Cerna, Rajiv Halim, Jarrard Har ris, Chiquita Jones, Greg Kelley, Bill King, Jason Koransky, Terry Martin, Ted Oppenheimer, Bethany Pickens, Mike Reed, Judith E. Stein, Neil Tesser, Darryl Wilson.

Staff: Scott Anderson, Diane Chandler-Marshall, John FosterBrooks, Maggy Fouche, Darius Hampton, Mashaune Hardy, Raymond A. Thomas.

Founded in 1969, the Jazz Institute of Chicago, a not-for-profit corporation, promotes and nurtures jazz in Chicago by provid ing jazz education, developing and supporting musicians, building Chicago audiences and fostering a thriving jazz scene.

410 S. Michigan Ave., Suite 500, Chicago IL 60605 | 312-4271676 • Fax: 312-427-1684 • JazzInChicago.org

The Jazz Institute of Chicago is supported in part by The Alphawood Foundation | The Francis Beidler Foundation | The Chicago Community Trust | A CityArts grant from the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events | Crown Family Philanthropies | Cultural Treasures | The Philip Darling Foundation | The Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation | Dan Epstein Family Foundation | The Illinois Arts Council Agency | Lloyd A. Fry Foundation | The MacArthur Fund for Arts and Culture at Prince | The National Endowment for the Arts | The Oppenheimer Family Foundation | The Polk Bros. Foundation | The Benjamin Rosenthal Foundation | Walder Foundation

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 12 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

CREDITS NOVEMBER 2022 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

By Howard Mandel

By Howard Mandel