A DIAMOND IN THE ROUGH

PART TWO OF A THREE PART SERIES

As our centennial celebration of Louis Armstrong’s arrival in Chicago ramps up this summer, we offer you a three part series on jazz starting pre-Louis through his profound impact on the art. No story on the Louis in Chicago could be complete without discussing the role of Lil Hardin Armstrong. A gifted and talented pianist and writer, she married Louis in Chicago and helped him develop into an international superstar. present suite that honors his roots and relatives

LOUIS ARRIVES IN CHICAGO

By Kent Richmond & Howard Mandel

The progenitors of New Orleans cornet playing, who established the brass instrument as the lead voice in what we now know as jazz, start with legendary Buddy Bolden and include well-documented Bunk Johnson, Emmanuel Perez and Freddie Keppard. They were all con-

temporaries and influences on Joseph Nathan Oliver, born in 1881. Oliver used what he had learned from those fathers of the music to jumpstart his career as an instrumentalist with a band, just as Louis Armstrong would launch himself a few years later in Chicago based on the mentorship of King Oliver.

Armstrong, born August 4, 1901, had lived

with his grandmother, mother and sister in the hardscrabble New Orleans neighborhood called The Battlefield. He was only six when he found work collecting rags and bones and delivering coal while playing a tin horn off the back of a wagon for the Karnofsky family, Lithuanian Jews who treated him well, even advancing him funds to buy a $5 pawn shop cornet. That purchase, and the infamous New

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO JULY 2022 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued on page 2

Fate Marable’s Orchestra aboard Streckfus Steamers’ steamboat the “”S.S. Capitol””, New Orleans, Louisiana: Louis Armstrong, cornet; Johnny St. Cyr, banjo; David Jones, sax; Norman Mason, sax; Norman Brashear, trombone; Baby Dodds, drums; Boyd Atkins, violin. Circa-1920. (Louisiana State Museum)

Year’s Even shooting-into-the air incident of 1914 which landed him in the Colored Waif’s Home where he came to play horn in band and parades, were pivotal events precipitating Louis Armstrong’s subsequent artistry, career and fame.

The Streckfus Steamboat Line was the first to hire a band to popular music during its pleasure trips on the Mississippi River from New Orleans to St. Louis and occasionally as far north as St. Paul. That band was directed by Fate Marable, a taskmaster who hired New Orleans musicians such as Pops Foster, Johnny Dodds, Herman “Baby” Dodds, Johnny St. Cyr and, eventually, Louis Armstrong. Musicians were paid $50 a week plus room and board, and a $5 a week bonus if they stayed on for the whole excursion.

Captain John Streckfus, owner of the Line’s S.S. Sydney and S.S. Capitol, was a fiddler who would occasionally sit in. At rehearsals he would take out his watch and time the beats per minute to make certain that the music was danceable.

The Black players were instructed not to speak to the white passengers unless spoken to first. This job is among Armstrong’s earliest experiences with a white “high society.” It has been claimed that both Bix Beiderbecke and Jack Teagarden first heard Armstrong’s clarion horn lofting over the Mississippi waters from the passing steamboat.

Back home, teenage Louis had caught the attention of trombonist Kid Ory – with whom Joe Oliver played. When Oliver had left the Crescent City for Chicago in 1918, Armstrong took his place in Ory’s band, and maintained correspondence with the man he referred to as “Papa Joe.”

Oliver had done well in Chicago – his appearance with the White Sox Booster Band in 1920, after the team disgrace of the Black Sox scandal, was certainly intended to give a positive charge to the baseballers’ image. But he was professionally restless. He took his Creole Jazz Band, including pianist Lil Hardin, to San Francisco in 1920. The players were un-

easy with local attitudes towards Blacks there, and drifted back to Chicago. Oliver went down to Los Angeles, but Hardin was among the defectors, quitting, going home, resuming her gig as house pianist at the Dreamland Ballroom.

On January 17, 1920, the 18th Amendment banning sales of alcoholic beverages -passed by the U.S. Congress over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto -- went into effect. Much has been made of Chicago’s fervent rebuke of Prohibition, for instance through its establishment and patronage of speakeasies. Gambling and prostitution as well as booze were featured attraction in these joints, with police and officials paid to look the other way.

However, it was unpractical for large clubs featuring dynamic music which could be heard by any passersby to operate “underground.” So venues like the Royal Gardens, Sunset Cafe and Burt Kelly’s Stables were set-up bars (also known as bottle clubs, perhaps giving rise to the term BYOB).

A patron would buy a soft drink to discretely spike from a flask carried in their coat jacket or purse, so if police raided a club would not be criminally liable or closed.

Of course, Chicago’s Roaring ‘20s was the era of Al Capone and competing gangs. Mob-owned clubs were commonplace, and Capone himself was a primary sponsor of the growth and popularity of jazz. Many of his places were “Black and Tan” clubs, where integrated audiences were welcomed. As long as money could be made from cover charges and drink sales, the bosses were happy.

Musicians from New Orleans were no

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 2 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued from page 1, Louis Armstrong

Joseph ‘King’ Oliver’s band; l to r: Charlie Jackson(bass sax), Clifford ‘Snag’ Jones (dr); (trumpet), William ‘Buster’ Bailey (cl,sax), Joe Oliver (cornet), Alvin ‘Zue’ Robertson (tb), Lil Hardin Armstrong (p), Louis Armstrong (ct), Rudy Jackson (cl,sax)

strangers from dealing with gangsters, and many actually liked working for the mob. The gigs were steady, the pay was good and they were treated with relative respect. In early 1922 Oliver returned to Chicago from out west to take up residency with his ensemble -- the Dodds brothers on clarinet and drums, respectively; banjoist St. Cyr; Honoré Dutrey, trombone; Bill Johnson, bass; Bertha Gonzales, piano – at the Royal Gardens, rechristened as Lincoln Gardens.

Oliver was not a smoker or a drinker, but he enjoyed sugar sandwiches chased with sugar water - which exacerbated a gum condition, making it painful for him to play his cornet. As his condition worsened, he sought to remedy the situation by calling on his protégé Louis Armstrong to join him in Chicago, to play second cornet and fill in when King was ill.

Although initially hesitant to leave New Orleans, Armstrong wrote in his autobiography Satchmo: My Life In New Orleans (published in 1954) “I made up my mind just that quick nothing could change it, Joe my idol had sent for me.” He took the Illinois Central’s City of New Orleans train north, sustained by a fish sandwich his mama had made him since Blacks weren’t served in the dining cars. He arrived at the 12th Street Station at Roosevelt Road and Michigan Avenue. He was distressed Oliver wasn’t there to meet him, but the King had arranged for a porter to put Armstrong in a cab and direct it to the Lincoln Gardens where the Creole Jazz Band was performing that night.

Arriving at the club, Louis stayed in the back to watch the band finish its set. He was impressed with the fine suits guys he’d known from his days with Fate Marable were wearing. He sat in with them during the next set, after which, King Oliver took Louis to a boarding house at 3412 S. Wabash Avenue, near his own place at 31st and State.

The next day 21-year-old Louis showed up at the Gardens wearing a patched second-hand suit that he hoped that no one would notice. After that night’s show, Oliver took Armstrong to the Dreamland, to persuade Lil Hardin to rejoin his group.

Upon their introduction, Armstrong was smitten with Hardin, who was pretty, petite, stylish, educated and confident -- everything that he was not. Her first impression was that a country bumpkin weighing over 200 pounds probably should not be called “Little Louis.”

“I was very disappointed,” she remembered years later. “I didn’t like anything about him. I didn’t like the way he dressed, I didn’t like the way he talked. I just didn’t like him. I was very disappointed.” However, she agreed to rejoin Oliver’s ensemble. Unknown to Armstrong, she got more money than he did.

Hardin was more interested in financial aspects of the music business than artistic ones. Her piano style was rhythmically-oriented rather than ambitiously virtuosic, but she wrote several songs for the group and most of its arrangements. Lil was not the soul of the band, but its brains. And King Oliver was arguably the best cornetist in the land, the Creole Jazz Band the most popular and innovative such troupe anywhere.

Oliver’s contributions to early jazz cannot be overstated. He heard his band as a single instrument, but allowed the individuals to improvise, decorating and embellishing a song’s melody. He pioneered using plumber’s plungers, derby hats and doorknobs as mute. And he introduced, at least to recording, the format of a two horn-front line (trombone then principally added “tailgate” comments, clarinet untethered obligati). “Dippermouth Blues” is a classic example of Oliver’s use of a mute and collaboration with Armstrong.

As second cornet, Louis fashioned free harmonic lines and counterpoints around over and under Papa Joe’s lead. If Joe was feeling poorly, he would signal Louis to take over.. “From Satchmo: “It was my ambition to play as he did. I still think that if it had not been for Joe Oliver, jazz would not be what it is today. He was a creator in his own right.”

In April 1923 King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band was invited to a recording session at Gennett Records’ studio in Richmond, Indiana. The eight-piece band -- cornetists Oliver and Armstrong; clarinetist

Dodds and his brother Baby on percussion; trombonist Dutrey; bassist Johnson; banjoist St. Cyr and pianist Hardin -- was apprehensive because the area was a known stronghold of the Klu Klux Klan. Fortunately, the studio was near the train station.

In a small room, positioned around the horn of a gramophone, they cut mechanical recordings, the unmediated sound in the studio moving a needle into wax from which metal plates would be cast for duplication, of 12 songs on April 5 and 6. The Gennett studio was so close to the RR tracks that the recording engineers had to pay close attention to the train schedules. Because of the powerful nature of his playing, Armstrong was asked to stand 15 feet away from the gramophone. His first recorded solo is on “Chimes Blues.” Among the other sides besides “Dippermouth” were “Alligator Hop,” “Weather Bird Blues” and “Zulu Ball.”

Later that year, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band recorded for the Okeh, Columbia and Paramount labels. Their 78 rpm discs shellac discs, priced at around 75 cents (roughly $12 in 2022) were originally sold as “race records,” meant for the presumed Black market that had asserted itself with the breakout success of “Crazy Blues,” by Mamie Smith with her Jazz Hounds in 1921. That presumption was a mistake, because from the first a significant portion of the audiences for Black music was white. The recordings survive today, in historical reissues, some with contemporary technology employed to improve the original sound quality.

Eventually King Oliver confided to Lil Hardin that Louis Armstrong was a much better cornetist than he himself was. She began to view Louis as a diamond in the rough. She coached him on his speech and mannerisms, convinced him to throw away his secondhand clothes and buy new ones. He wore bangs when he first came to Chicago, which she hated – she got him to cut them. She helped him lose weight. To the surprise of their bandmates, the pianist and cornetist were spending more time together.

Could romance be in the air?

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 3 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

BILL MCFARLAND & THE CHICAGO HORNS DISCUSS AND DEMONSTRATE LIFE IN MUSIC

By Corey Hall

Music so moved the eight-year-old child that he looked behind the radio, hoping to see little people producing all those sounds…

Insubordination from one saxophonist in the high school band meant that the clarinetist, comfortable with his axe, had to take the expelled ensemble member’s place…

And in the kitchen, with doors open wide, a drummer sat behind his kit and played. A child who lived nearby in this Ida B. Wells housing complex, listened every day, eventually signing up to play drums at Dyett Middle School. When told to play trumpet instead – as there were too many drummers – he wanted to quit, until his dad encouraged him to give the horn a chance…

These stories about one’s introduction to music – from trombonist Bill McFarland, saxophonist Hank Ford, and

trumpeter Kenny Anderson, in that solo order – were shared at a recent discussion hosted by the South Side Jazz Coalition (SSJC) and held at Tolton Catholic Academy, 7120 S. Calumet. This event celebrated the trio, better known as Bill McFarland and the Chicago Horns. Since 1990, this ensemble, made a sextet by various players in the rhythm section, has released three albums, and enjoyed lengthy stays at Andy’s and the now-defunct Jazz Bulls, among other hangs.

Moderated by bassist and educator Chuck Webb, the discussion covered first paid performances, Chicago’s music scene, and many more notes in between. “We still have some jazz icons here in Chicago,” Webb said to the attendees that filled the auditorium, “and we want to honor them while they’re still here with us.”

When discussing first gigs, Anderson

recalled his experiences at a lounge on 39th and Indiana in the ‘70s. “I wasn’t even supposed to be there, as I was just 17 years old,” said Anderson, whose recording/touring credits include the Ohio Players, Freddie Ruiz, and Willie Kent. “We played, and these people were coming up throwing money at us! That was it for me; I was stuck!”

Ford’s first hits, also in the ‘70s, happened at a blues club, but someone had to be in a certain condition first. “I would sit my horn out back in a wheelbarrow,” said Ford, whose resume includes Sugar Blue, Bonnie Lee, and the Winans. “And when my mom fell asleep, I would climb out the window, grab my horn, get on the bus, and go down to 1300 South Wabash.”

After recalling his first paid gig at a lounge in Lake Meadows – with a jazz ensemble that included pianist Ari Brown – McFarland discussed record-

PAGE 4

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO

JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO

(left to right), Kenny Anderson, Hank Ford, and Bill McFarland.

ing in the late ‘60s with singer Alvin Cash.

“We did a tune called, ‘Keep On Dancing, Baby,’” recalled McFarland, whose credits include Son Seal, Fenton Robinson, and Otis Clay. “I did the horn arrangements, and that song made it to number ten on the WVON charts.”

Before asking about the perceived/realistic divisions between Chicago’s South- and North-side-based musicians, Webb talked about musicians’ union 10-208. “The Black musicians had to create their own subdivision of the Federation of Musicians, so that’s why the musicians’ union in Chicago is called 10-208,” he explained. “It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that these two came together.” This led Webb to ask, “Do you feel that, once you get past downtown, the vibe changes?”

“There is always a dividing line,” McFarland responded, before acknowledging an effective solution: the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. “They created their own work, their own music, their own concerts and recordings,” said McFarland, adding that he participated briefly with the AACM. “That was the model we had to follow if you wanted to prove yourself on your own.”

Then, when asked how the once active jazz club scene on the South side could be revived, Anderson praised the SSJC’s efforts, which have included performances at the nearby St. Moses the Black Parish. McFarland also praised saxophonist Ernest Dawkins, who has presented the Englewood Jazz Festival for more than 20 years. “Dawk,” in partnership with the Jazz Institute of Chicago, recently staged “Blacker Than Black,” a tribute to the late JIC board member Timuel Black. Attracting young people to this music, all agreed, is also necessary.Webb’s

final questions were about the best advice each had given and received. When addressing the latter, McFarland shared what the late trombonist and Jazz Crusader Wayne Henderson told him: “ ‘Get in the books.’” Prompted by Webb to explain what that meant, McFarland added: “Hit the musical

Cobb to the stage, and started the hit. And, as appreciated by their followers, the sextet played “Harold the Great,” McFarland’s tribute to Chicago’s first Black mayor. Weeks after this performance, McFarland, in a discussion with the JazzGram, shared memories about this composition, which came to him on Thanksgiving Eve, 1987.

“I was walking home from work, really depressed about the news of Harold’s passing,” he recalled. “As the snow crunched under my feet, I heard, ‘Ba-bump-ka-chink-achink-bang-bang.’ That rhythm came into my mind, and it reminded me of a forest of people in movement, in unison.”

Then, in McFarland’s mind, the bass line began: “Bump-booday-day-day-day-day-daybump!” followed by a melody.

“I then felt like this was a gift bestowed to me by the Creator,” he said.

exercises together to become more proficient. If you want to play, you gotta have it in your head. If you don’t know it, you can’t play it.”

Ford’s advice: “Practice. That’s all I can say. Without practice, it’s nothing.” Surviving as a professional musician, Anderson responded, is only possible if you love all that such a lifestyle brings. “This ain’t no joke. I know about the blood, guts, sweat, and tears of being broke,” he said. “I know what it took to get to this point, and when I see somebody taking it for granted, it pisses me off.

“But,” he continued, “if I play Lotto tomorrow and win $400 million, I’d still play my horn.”

Once the discussion ended, the gents grabbed their horns, welcomed keyboardist Kirk Brown, bassist Yosef Ben Israel, and drummer Kwame Steve

Upon arriving home, McFarland got his trombone and wrote the music playing in his mind onto manuscript paper. He then described what key this creation would be played in, (F-minor), finished it, and prepared to present it to his band, known then as the McFarland/ Ford quintet. “Harold the Great” appears on two albums by the Chicago Horns and one by the late trumpeter Malachi Thompson’s Africa Brass. It debuted in early 1988 at Wise Fools on Lincoln Avenue.

“When people book this band, they always say, ‘We want to hear ‘Harold the Great.’ It’s an honor to get these requests,” he said. “That song represents the determination Harold had in his political career, and it represents what he meant to me as an accomplished, caring man.”

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 5 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

THE SHADOW LINE

by Rafael Alvarez

Memphis, awash in blues from the moment hollers emerged due south of the Bluff City about the time of the Civil War, was busy with dreams of 12-bar fame last month, [may 2022]. It was the week of the International Blues Challenge and Beale Street was thick with the ghosts of legends, tourists in search of a rockin’ good time and hopeful musicians from around the world.

But only the most knowledgeable (perhaps a few professors at the Scheidt School of Music) were hip to the Chickasaw Syncopators and how this long-

ago student orchestra once navigated the music of the Mississippi River from Memphis to New Orleans and back again.

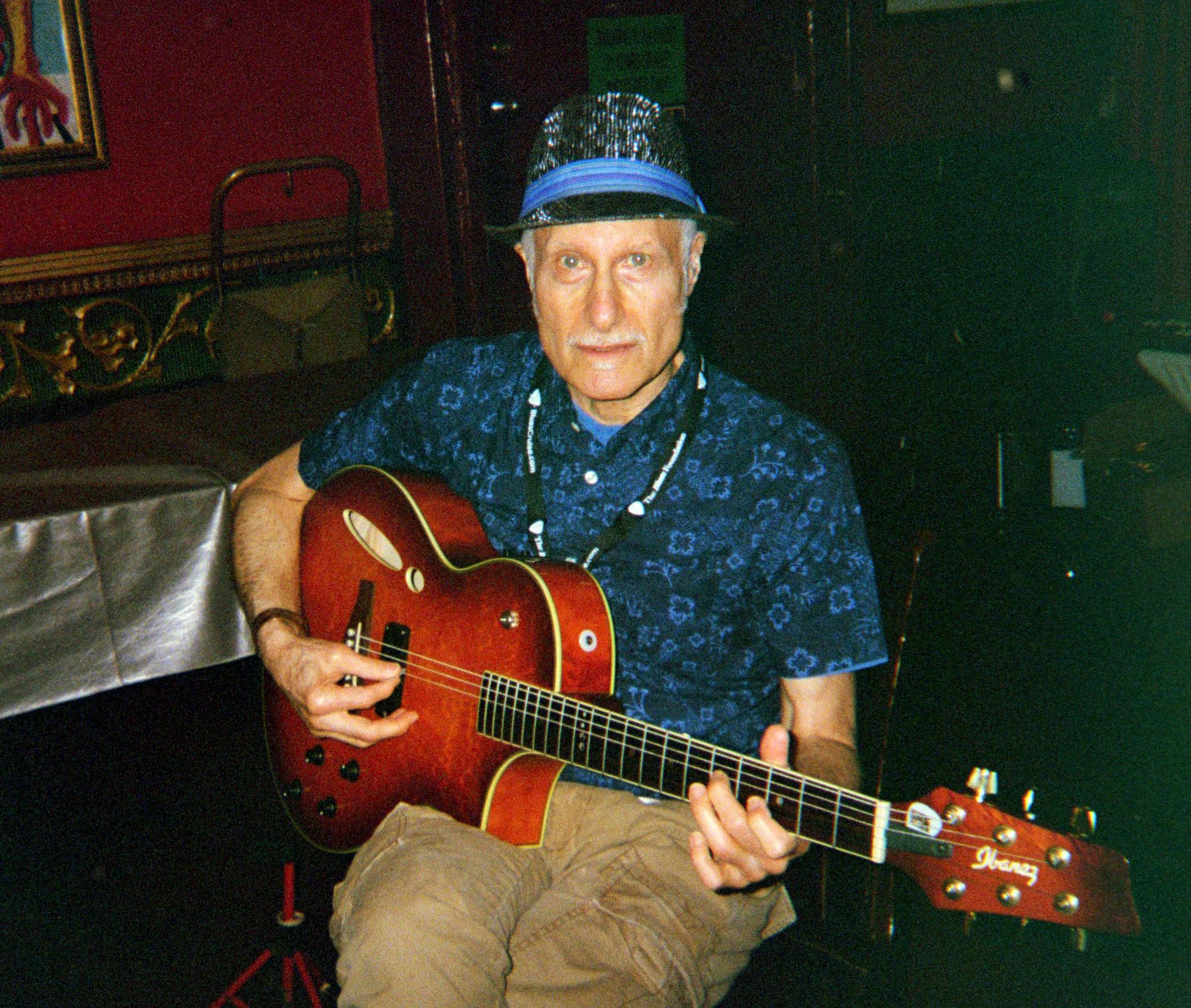

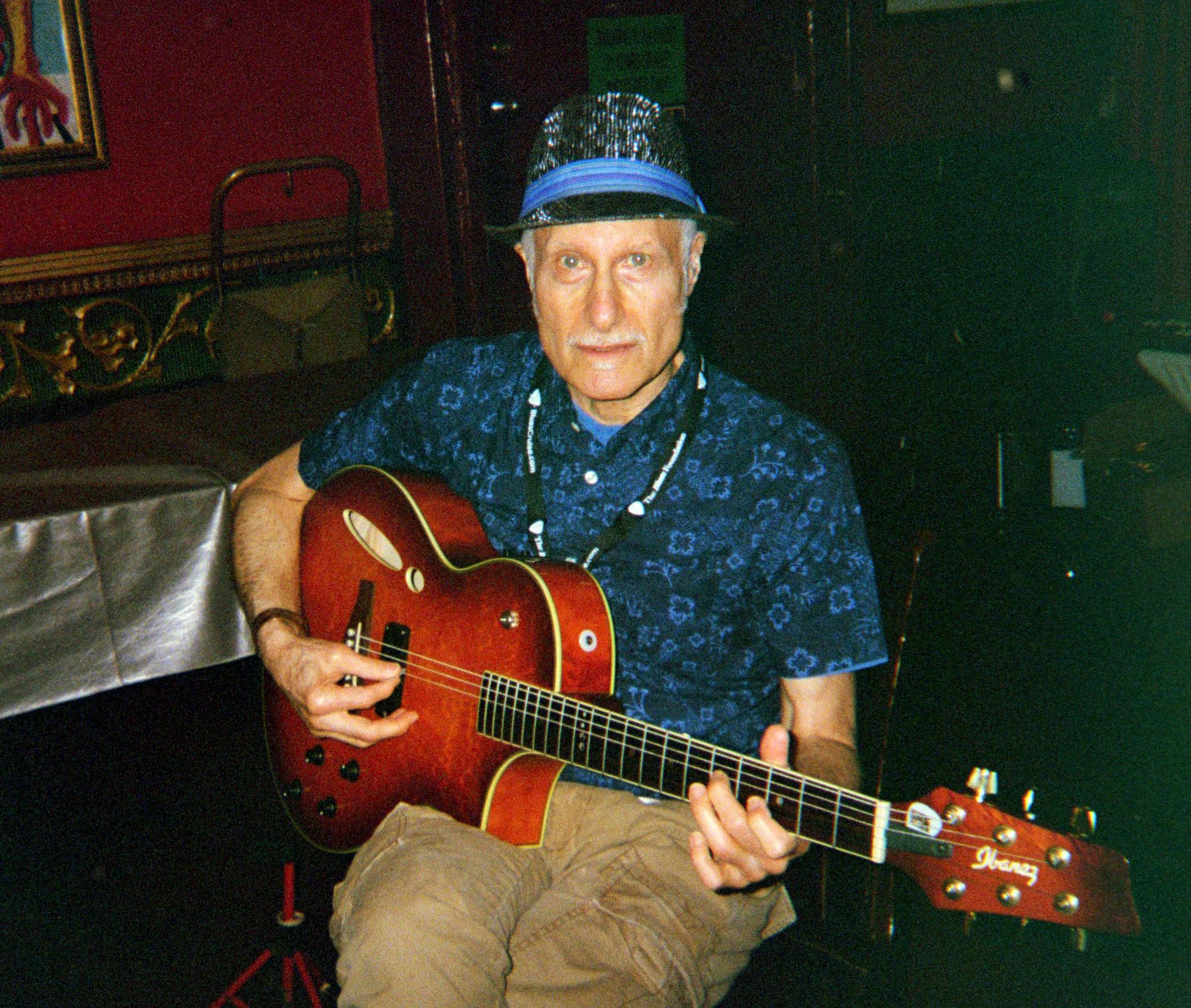

How to classify – with the specificity of taxonomy -- each stop along the way? “Categorizing music is done for commercial reasons more than for anything else,” said Robert Ross, 73, a lifelong grinder on blues guitar and vocals who made it past the first round of the Blues Challenge but not the finals. “The human brain loves to label everything. If we’re gonna play that game, yes there is

a fine line between blues and jazz, but it seems damn arbitrary to me.”

The great Tom Waits once said that a good song is like a heavily pregnant insect: cut it open to find a hundred other songs waiting to take flight. In doing so, you kill the bug that lays the golden songs.

Continued Ross, donning surgical gloves, “Musicians would define blues as any music that uses 3 chords [I, IV, V] and one of three scales -- minor pentatonic, major pentatonic, or mix-

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 6 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued on page 7

Robert Ross, Beale street, Memphis

olydian scale. Usually 12 bars in length but it is also found as 8, 16, and even 24. Many old blues have structures that are not divisible by four – all kinds of crazy variations. But only nerds are interested in the complexities of these distinctions, right?”

Nerds, writers, academics, and everyone else who wishes they could thrill a crowd with music, the only religion, according to Frank Zappa, that “delivers the goods.”

I began learning how much I didn’t know the hard way when, as a young newspaper reporter in 1981, I interviewed Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown (1924-2005) at a gig in Baltimore.

Louisiana-born, Brown was a singer and multi-instrumentalist proficient on guitar, violin, viola, mandolin, harmonica, and drums. Though strongly identified with the blues, he disdained purity (if, like truth, it even exists) while recording everything from “Frankie and Johnny” to “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” and Delaney & Bonnies 1971 hit “Never Ending Song of Love for You.”

In his first set at No Fish Today (a fabled Crabtown venue soon-to-be destroyed by arson), Brown played Texas Swing, Tex-Mex, old-school country, and jazz in addition to some R&B in the style of Johnny “Guitar” Watson. During the break, he bitched me out so vociferously that a guy in his band said, “Come on, Gate, leave the kid alone.”

I had made the mistake of asking Brown why he hadn’t played more “real” blues. I was 23, as ignorant about AfricanAmerican music as I was passionate. He shot back, “All that Mississippi Delta stuff and the Chicago stuff is just a bunch of old ignorant Negroes feeling sorry for themselves. I won’t do that downer stuff.”

That long, embarrassing moment in the woodshed was on my mind in Memphis as I listened to a young man from Belfast named Dom Martin, just a guy and a guitar. Martin’s work is powerful; his voice sweet and raw as called for, original songs grounded in a life – gratefully abandoned -- of booze and drugs and violence which he did not expect to survive.

It was Martin’s guitar work – on display in his 2019 debut album Spain to Italy -- that took me back to the question at hand: Where is that elusive line and is it worth the effort to locate it?

Starting with a near-silent, whisper over the strings, Martin worked himself into a near-spastic whirl one might hear from a gitano in a Moroccan café. And then, somehow, the Irishman brought it back to the States, where the arc of our music bends backward toward the Delta and forward to whatever some kid is just now figuring out at the Chicago High School for the Arts.

“The development of harmony slowly separated jazz from blues,” said Jacques “Jack” Titley of the Wacky Jugs from Brittany, France, winners of “best band” honors in Memphis. “One was dedicated to keeping a sense of wild roots in the music and the other took it to the next level of sophistication. It just doesn’t happen with a snap of the finger.”

And then, with a candor so often absent in these discussions, the singer and mandolin man added, “We felt it during our trip between Memphis and New Orleans. But to be honest, I really don’t know.” As Robert Ross observed, “damn arbitrary.”

He has played behind Big Maybelle, Big Mama Thornton and Victoria Spivey and once busked for change in the City of Lights metro before trading a pint of his blood for a few francs and – by chance that same night -- backed-up pianist Champion Jack Dupree (19101992) in a Parisian tavern. He remembers his grandmother singing “Swinging on a Star” when he was a kid in Brooklyn and the Dodgers still played at Ebbets Field.

“It’s a funny old tune,” said Ross of the Bing Crosby movie number released by Decca in 1944 and long, if seldom played, in his repertoire. “I got interested in doing it after hearing Dave Van Ronk do it at Folk City one night. It cracked me up hearing that gruff voice singing it instead of Der Bingle’s croon.”

And thus, a jazz standard that began as a pop tune written by Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke migrated toward

the blues of a New Yorker with an ear for anything that might fit into his act. Anything at all if it can be strained through the sifter of American music. Two of the hottest names in 21st century blues are guitarists Christone “Kingfish” Ingram of Clarksdale, Mississippi and Samantha Fish, a native of Kansas City, Missouri, two historic hotbeds of American music. Fish once sat-in with Kingfish and said remembers it as thrilling and, and because of Ingram’s Hendrixlike virtuosity, intimidating.

“Growing up in Kansas City, of course I listened to Count Basie and Charlie Parker,” said Fish, who, despite sharing a keen musical ear with such greats claims she is unable “to touch” jazz onstage. “My favorite musicians will dip their toe in [blues and jazz] and mix it together. In the jazz world there are a lot more artists who straddle that line.”

Still, said Ross, “I have a broader view than most of what blues is, but if you’re going to categorize things there has to be limits.”

If so, no one told Jimmie Lunceford (1902-1947), a Roaring 20s saxophone player and football coach at Manassas High School in Memphis. Lunceford transformed the school band into the Chickasaw Syncopators (later the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra) and the toured the nation from the Cotton Club to West Virginia with a swaggering jazz both hot and swinging.

Jazz? Blues? The shadow line between? Take it from the other king from Memphis.

“As for my band,” B.B. King once said, “My mentors were Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, [and] Jimmie Lunceford…”

Rafael Alvarez is a former newspaperman who has written about the blues since interviewing Muddy Waters in 1978. In September, Cornell University Press will release his biography Don’t Count Me Out: A Baltimore Dope Fiend’s Miraculous Recovery. Alvarez can be reached via orlo.leini@gmail.com

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 7 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

continued from page 6, The Shadow Line

JIC EVENTS & SPECIAL OFFERS

“Fresh Fest” NextGenJazz Emerging Artists Project Navy Pier, 600 E Grand Ave. Join us for the closing performance of Fresh Fest for the Chicago Youth Music & Performance Showcase.

Friday and Saturday, July 15 & 16

Jazz City: Chicago Latin Jazz Festival 2022 Humboldt Park Fieldhouse, 1440 N. Humboldt Dr. Roy McGrath's Menjunje Ensemble James Sanders’ Conjunto

Luiz Ewerling & AMADA

Victor Garcia’s Tribute to Tito Rodríguez

CLUBS

Andy’s http://www.andysjazzclub.com/ 11 E. Hubbard/312-642-6805

Show times: 5pm & 7pm/ 9:30pm & 11:30pm

Every Sunday: Andy Brown Quartet (6PM & 8:15PM), Late Night Concert Series w/ Emma Dayhuff’s Phoenix Ensemble (10:30PM)

Every Monday (except the 4th): Clark Sommers Lens (6PM & 8:15PM)

Every Tuesday: Mario Abney Effect (6PM & 8:15PM)

Every Wednesday: Jeremy Cunningham’s Happenstance (6PM & 8:15PM), Late Night Concert Series w/ Joel Baer Trio

Every Thursday: Micah Collier’s Alectet (6PM & 8:15PM), Late Night Concert Series w/ Keri Johnsrud (10:30PM)

July 1 & 2: Petra’s Recession Seven (6PM & 8:15PM), Late Night Concert Series w/ Aaron Shapiro (10:30PM)

July 8 & 9: Christopher McBride & The Whole Proof (6PM & 8:15), Late Night Concert Series w/ Ken Shiokawa (10:30PM)

July 15 & 16: Isaiah Spencer Organ Group (6PM & 8:15PM), Late Night Concert Series w/ Micah Collier (10:30PM)

July 22 & 23: Isaiah Collier & The Chosen Few (6PM & 8:15PM), Late Night Concert Series w/ Keri Johnsrud (10:30PM)

July 29 & 30: Charles Heath (6PM & 8:15PM)

Cafe Mustache

http://cafemustache.com/ 2313 N Milwaukee Ave./ 773-687-9063

Live music Tuesdays-Sundays

Constellation

3111 N. Western/ www.constellation-chicago.com Show times and cover charges vary. Most shows 18 and over. July 15 (8:30PM): Jeff Parker & The New Breed - In Person Event

July 23 (8:30PM): Moore/Shead Duo with Edward Wilkerson & Tatsu Aoki - Virtual & In Person Event - Livestream Link: https://youtu.be/rKPkrFu4X-U

July 29 (8:30PM): Andrew Trim: RETROREFLECTOR, McCombs & Rumback - Virtual & In Person Event - Livestream Link: https://youtu.be/YD1HHG7U8-4 July 30 (8:30PM): Cunningham/Laurenzi/BryanA Better Ghost Album Release - Virtual & In Person Event - Livestream Link: https://youtu.be/hjhP3HRXV8k

Elastic ARTS

elasticarts.org/ 2830 N. Milwaukee/773-772-3616/elasticarts.org

July 7 (8:30PM): James Singleton’s Malabar & Meridian Trio

July 11 (8PM): Lara Driscoll Trio & Kabir Dalawari Sextet

July 14 (8:30PM): Tim Daisy Birthday Trios - 3x3

July 18 (8PM): Third Shore Collective & James Davis’ Beveled

July 21 (8:30PM): Klemens/Kirshner Duo & Quartet

July 25 (8PM): Devin Drobka Trio & Mai Sugimoto Quartet

July 28 (8:30PM): Dessus-Dessous & Mad Myth Science

July 29 (8:30PM): Elastro Series: Montgomery/Turner, Sabbagh/Negre/Brock, Daniel Wyche

Experimental Sound Studio ess.org 5925 N Ravenswood/773-998-1069

Fitzgerald’s 6615 Roosevelt, Berwyn/708-788-2118

Wednesday SideBar Sessions Sponsored by WDCB 90.9 Chicago’s Jazz Station, 8pm, $10 suggested Donation

July 9 (11AM): Jazz Brunch on the Patio: Groove Witness July 10 (6PM): Shout Section Big Band

July 13: Chris Greene Quartet (7PM on the Patio), Jarod Bufe Quartet (8:30PM at the Sidebar) July 16 (12PM on the Patio): Alyssa Allgood

Fulton Street Collective/ Jazz Record Art Collective 1821 W. Hubbard/ 773-852-2481. fultonstreetcollective.com/ jazzrecordartcollective.com $10 suggested donation/ $5 with valid student ID. All ages. Cash only. All Livestream Events can be found at: https://www.youtube.com/fultonstreetcollective

EVENTS CALENDAR PAGE 8 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

Green Mill

4802 N. Broadway/773-878-5552

SUNDAYS (8PM): Soul Message

MONDAYS (8PM) *except the 4th of July: Joel Paterson & Friends

TUESDAYS: (8PM) Chicago Cellar Boys

WEDNESDAYS: (8PM) Alfonso Ponticelli

THURSDAYS: Andy Brown (5PM), Alan Gresik’s Swing Orchestra (8PM)

FRIDAYS: Chris Foreman (5PM)

SATURDAYS: Paper Machete (3PM)

July 1,2 (8PM): Isaiah Collier & The Chosen Few

July 8,9 (8PM): Hinda Hiffman & Soul Message Record Release Party

July 15,16 (8PM): Fareed Haque w/ Bobby Watson

July 30 (8PM): Jason Wayne Sneed & Friends

Hungry Brain

2319 W Belmont Ave/773-935-2118

Every Thursday (9PM): Greg Ward Residency

July 1 (8PM): Erwin Helfer

July 3 (9PM): Hunter Diamond, James Singleton, Mike Reed

July 9 (9PM): Chris Morrissey

July 15 (9PM): The Joel Paterson Trio with Beau Sample and Alex Hall

July 22 (9PM): Herbsaint

Jazz Showcase

806 S. Plymouth Ct./312-360-0234

Two sets at 8pm & 10pm & *Sunday matinee at 4pm. Visit www.jazzshowcase.com for weekday JIC member discounts!

JIC member card required.

Every Monday (except the 4th) (5PM): Chicago Jazz Orchestra w/ special guests

July 1,2 (8PM & 10PM), 3 (4PM & 8PM): Saxophonist Greg Ward II

July 5 (8PM & 10PM): Christian Dillingham

July 6 (8PM): Bob Lark

July 7-9 (8PM & 10PM), 10 (4PM & 8PM): Bobby Lewis Quintet

July 12 (8PM): WDCB 90.9FM

July 13 (7PM): Chicago Human Rhythm Project

July 14-16 (8PM & 10PM), 17 (4PM & 8PM): Ryan Cohan

July 19 (8PM & 10PM): Metropolitan Jazz Octet w/ Dee Alexander

July 20 (8PM & 10PM): Saxophonist Jarrard Harris

July 21-23 (8PM &10PM), 24 (4PM & 8PM): Shawn Maxwell Quartet

July 26 (8PM & 10PM): Steve Schneck Quartet

July 27 (8PM & 10PM): Julia Danielle Quintet

July 28-30 (8PM & 10PM), 31 (4PM & 8PM): Chris Greene Quartet

Le Piano 6970 N Glenwood Ave/773-209-7631

TUESDAYS: (7PM) Cabaret “The Daryl & Ester Show”

EVERY OTHER WEDNESDAYS SERIES: (7PM) Brazilian Latin Jazz"Rio Bamba" Luiz Ewerling

EVERY OTHER WEDNESDAYS SERIES: (7PM) Le Piano Jazz Jam Session

THURSDAYS: (7PM) Derek Duleba Organ Trio

FRIDAYS: Chad Willets Quartet (7PM) Afterglow Late Show (11PM)

SATURDAYS: Chad Willets Quartet (7PM), "Afterglow Set" with Petra van Nuis/Dennis Luxion Duo (11PM)

SUNDAYS (7PM): The Velvet Torch Series

Whistler

2421 N. Milwaukee, Logan Square/773-227-3530

July 6 (9PM): Relax Attack Jazz Series Presents Chicago X Nola: Diamond/Singleton/Peake

July 13 (9PM): Relax Attack Jazz Series: Twin Talk

July 20 (9PM): Relax Attack Jazz Series: The John McNamara Trio July 22 (7PM): Brian Citro

Winter’s Jazz Club 465 N. McClurg Court (on the promenade) Ph: 312.344.1270 www.wintersjazzclub.com info@wintersjazzclub.com

SET TIMES

Tuesday - Saturday 7:30 & 9:30PM Sunday 5:30 & 7:30 PM

ALL ENTRANTS REQUIRED TO PROVIDE PROOF OF BEING FULLY VACCINATED

July 1 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Pharez Whitted Quintet

July 2 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Denise Thimes Quintet - An Evening of Ballads & Blues July 3 (5:30PM & 7:30PM): Bosman Twins Quintet - Celebrating Red, White, and Chicago Blues!

July 6 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Chris White QuartetThe Latin Side of Vince Guaraldi

July 7 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Rosenberg, Rodgers, Heath Trio

July 8 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Tim Fitzgerald Trio w/ Abby RiccardsThe Music of Aretha Franklin & Ray Charles

July 9 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Christy Bennett's Fumée

July 10 (5:30PM & 7:30PM): Bruce Henry QuartetA Journey Through Jazz: From Congo Square to Harlem

July 13 & 27 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Soul Message Band w/ Hinda Hoffman

July 14 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Elaine Dame Quartet

July 15 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Alfonso Ponticelli Trio

July 16 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Johnny O'Neal Trio

July 17 (5:30PM & 7:30PM): Chris Madsen Quartet w/ Alyssa AllgoodJohn Lennon & Paul McCartney

July 20 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Paul Marinaro Quartet - A Birthday Bash!

July 21 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Ryan Cohan Trio

July 22 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Michael Hackett/Tim Coffman Sextet feat. Sharel Cassity - Album Release Party

July 23 (7:30PM & 9:30PM): Marques Carroll Quintet - Debut!

July 24 (5:30PM & 7:30PM): Spider Saloff Quartet - SpeakeasySongs from Prohibition: Berlin, Waller, Porter and more!

July 28 (7:30 & 9:30PM): Jeremy Kahn Trio w/ Leslie Beukelman

July 29 (7:30 & 9:30PM): Chicago Cellar Boys

July 30 (7:30 & 9:30PM): Tammy McCann Quartet

July 31 (5:30 & 9:30PM): Henry Johnson Quartet w/ Scott Burns

EVENTS CALENDAR PAGE 9 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 10 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

ALUMNI ON THE KIEWIT-WANG MENTORSHIP AWARD

on what you can work on and how to improve yourself and everything so it’s a really educating experience as well as, like, an audition.”

Miliano took lessons with saxophonist Geof Bradfield because he’s “a really influential person around Chicago. He’s always playing around in all these places. Mr. Bradfield also teaches at NIU. He just really knows what he’s doing. He knows the music.”

On a Saturday in June, a group of aspiring young jazz performers audition for the opportunity to take free private lessons with their chosen professional artist.

Auditions for the annual Kiewit-Wang Mentorship Award were held at the Logan Center for the Arts on campus of the University of Chicago on June 18th. The Jazz Institute of Chicago opened applications in March and received them from students in 9th through 11th grade from across the metro. Candidates audition for the chance to be awarded ten lessons with a local jazz musician of their choice, covered by the Jazz Institute of Chicago.

The finalists from 2021 are Leo Milano, a saxophonist from the Chicago High School for the Arts, and Brandon Harper, a pianist from Lincoln Park High School. They seem to have had a superior experience throughout the entire process.

About the audition process, Milano says “you get to choose most of the material and then you play it with some of the best musicians in Chicago… and then you get feedback from those musicians

The audition requires playing two musical selections: one which the auditionee chooses between two options given prior to the audition and another which the auditionee chooses and announces at the audition. The auditionees get to play with a small ensemble formed of the adjudicators themselves.

Speaking of how he felt after the audition, Harper said “I was a little hesitant… or I was a little doubtful that I was going to get it because I’m kind of a perfectionist when it comes to music where if I hear one mistake I think it’s kind of a big difference… I thought when I was auditioning I made a lot of mistakes.”

Local artists Miguel de la Cerna, Marlene Rosenberg and Ernie Adams were the judges who selected Harper and Milano for the award.

Harper says he found out he had been selected about a week after the audition. “I was surprised at first ‘cause I’m always doubtful of like… of how well I play.”

For Milano, the second time was the charm. “I felt pretty great because I auditioned before… now this year I auditioned again like a second time and I got it and it just, you know, felt really good, ‘cause it showed kind of like I made some progress.”

LET’S JAM AGAIN SOON!

The final Jazz Links Jam Session for the 2021-2022 season took place on May 11 at the Jazz Showcase. The culmination of our return to live jam sessions had a great turnout. It featured young musicians from the Ravinia Jazz Scholars

program whom we invited for a final blowout. Thanks to everyone who came out to this and the other jam sessions this season, building momentum and enthusiasm for live jazz and supporting young players.

“We would work on a lot of, um, we’d work on taking tunes through all 12 keys… and different types of patterns to work on. More rhythm concepts and concepts of time. Working on really getting that time feel down… just making a nice sense of time a lot better.” In his lessons with Geof Bradfield, Milano says he was given “a whole different way to mix it up and keep your brain challenged and fresh make newer pathways faster.”

Harper chose to take lessons with Richard Johnson, but he had met and worked with him previously. “While I was in Ravinia working with Ernie Adams I heard Mr. Johnson playing. I think I heard Mr. Johnson while I was leaving a concert… I heard him soloing and that instant I was like ‘hey, I really want to work with this guy’ he’ll probably give me a lot of great ideas and give me something to work on.”

“I think, studying with Mr. Johnson, he knew exactly what I needed to work on in order to be a better musician and improve more and also expanding my knowledge on the history of jazz with the amount of stuff that Mr. Johnson has recommended me to listen to”

The 2022 Kiewit-Wang finalists can look forward to similar accelerated growth as Harper and Milano.

Looking back on his experience as a Kiewit-Wang awardee, Milano sums it up. “It was an honor to receive this award and I strongly encourage everyone to apply for it because it’s really worth it.”

Look out for Jazz Links Jam Sessions to return in the fall on the second Wednesday of each month!

JAZZ IN CHICAGO EDUCATION CORNER PAGE 11 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

Heather Ireland Robinson, Executive Director and Diane Chandler Marshall, Education Director with 2021-2022 Kiewit Wang Awardees Leo Milano and Brandon Harper, at the Pritzker Pavilion for Chicago In Tune 2021.

Photo by James Foster.

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 12 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 13 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG 2022 IS THE YEAR OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG! EXCITING CONCERTS, DISCUSSIONS, SHOWINGS THROUGHOUT THE YEAR

The JazzGram is a monthly newsletter published by the Jazz Institute of Chicago for its members. The Jazzgram represents the views of the authors, and unless so designated, does not reflect official policy of the Jazz Institute. We welcome news and articles with differing opinions.

Design: YoojDesign

Correspondents: Diane Chandler-Marshall, Aaron Cohen, Corey Hall, Ayana Contreras, Howard Mandel, Rahsaan Clark Morris, Neil Tesser.

Board of Directors: President: David Helverson

Vice Presidents: Timuel Black In Memoriam, David Bloomberg, Warren Chapman, William Norris, Keyonn Pope, Kent Richmond, DV Williams.

Secretary: Howard Mandel

Treasurer: Brian Myerholtz

Emeritus Director: Joseph B. Glossberg

Executive Director: Heather Ireland Robinson

Board Members: Miguel de la Cerna, Rajiv Halim, Jarrard Harris, Chiquita Jones, Greg Kelley, Bill King, Jason Koransky, Terry Martin, Ted Oppenheimer, Bethany Pickens, Mike Reed, Judith E. Stein, Neil Tesser, Darryl Wilson.

Staff: Scott Anderson, Diane Chandler-Marshall, John FosterBrooks, Maggy Fouche, Darius Hampton, Mashaune Hardy, Raymond A. Thomas.

Founded in 1969, the Jazz Institute of Chicago, a not-for-profit corporation, promotes and nurtures jazz in Chicago by providing jazz education, developing and supporting musicians, building Chicago audiences and fostering a thriving jazz scene.

410 S. Michigan Ave., Suite 500, Chicago IL 60605 | 312-4271676 • Fax: 312-427-1684 • JazzInChicago.org

The Jazz Institute of Chicago is supported in part by The Alphawood Foundation | The Francis Beidler Foundation | The Chicago Community Trust | A CityArts grant from the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events | Crown Family Philanthropies | Cultural Treasures | The Philip Darling Foundation | The Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation | Dan Epstein Family Foundation | The Illinois Arts Council Agency | Lloyd A. Fry Foundation | The MacArthur Fund for Arts and Culture at Prince | The National Endowment for the Arts | The Oppenheimer Family Foundation | The Polk Bros. Foundation | The Benjamin Rosenthal Foundation | Walder Foundation

PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO PAGE 14 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

CREDITS

2022 JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG

JULY