Editors: Malebona Precious Matsoso, Usuf Chikte, Lindiwe Makubalo, Yogan Pillay, Robert (Bob) Fryatt

ISBN: 978-0-6397-2368-6 (print) ISBN: 978-0-6397-2369-3 (e-book)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Subject to any applicable licensing terms and conditions in the case of electronically supplied publications, a person may engage in fair dealing with a copy of this publication for his or her personal or private use, or his or her research or private study. See Section 12(1)(a) of the Copyright Act 98 of 1978.

Typeset in ITC Galliard Std 10.5pt

Printed in South Africa by Trackstar Trading 111 (PTY) LTD

The author and the publisher believe on the strength of due diligence exercised that this work does not contain any material that is the subject of copyright held by another person. In the alternative, they believe that any protected pre-existing material that may be comprised in it has been used with appropriate authority

Chapter 8: Health Emergencies, AMR and Covid-19 Response.......................................... Introduction

Global context in the preparedness and response to health emergencies circa 2012-2015 ... South African preparedness and response to health emergencies 2015-2020

Organisation of responses to COVID-19

Emerging lessons in public health emergency preparedness and response, 2015-2020

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 9: Non-communicable Diseases

Introduction

Key policy and guideline changes

Challenges experienced during the past 5 years

Risk factors for NCDs

Impact of COVID (good and bad) on NCDs

The New National Strategic Plan (NSP) for NCDs

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 10: Mental Health

Introduction

Recent crises in SA mental health

Service organisation

Human resources in the mental health professions

Recent research developments for improved mental health systems

Conclusion and way forward

Chapter 11: Occupational Health and Safety ....................................................................

The world of work in South Africa – Governance, Legislation and Policy Occupational Epidemiology ............................................................................................. Occupational Health Services (Prevention, Promotion, Care, Rehabilitation)

Human resources and Professional Societies

Challenges facing South Africa

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 12: Infrastructure

Introduction

Description of the status-quo

Broad Overview of Infrastructure Challenges in the Health Sector

Other Issues that affect Infrastructure Provision and Efficacy

Reforms by the Government to Resolve Challenges and the extent of Success

Factors that may affect Infrastructure in the Future

Conclusions and Recommendations

Chapter 13: Quality of Care

Introduction

Governance and leadership of quality

Revolutionising quality of care

Private Sector Quality

Measurement of quality Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 14: Legislative framework and the right to health 2015-2020

The Relationship Between Law and the Right to Health The Legal Framework and how it has Changed between 2015 and 2020 A Case Study: What Covid-19 Teaches us about the NHI

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 15: Governance, Leadership and Management

The relationships and interfaces of health system governance

Governance at the frontline

Leadership and management practice

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 16: Information and Indicators for Accountability

Introduction

Background to Information and Indicators for Accountability

Innovations and reforms, 2015–2020

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 17: Human Resources for Health

Introduction

National Strategy on Human Resources for Health in South Africa

Status of the Health Workforce

Moving HRH towards the Centre of Health Systems: Needs, dilemmas and strategies

National HRH Strategic Planning: 2020- 2030

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 18: Health financing

Introduction

National health insurance (NHI)

Trends in health spending and budgets

Health Market Inquiry

Standardising benefit package and options

Public sector cost pressures

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 19: Global and Regional Health

Introduction

Global Health Landscape

South Africa’s Role in the Multilateral System for Global Health

South Africa and Health Diplomacy

Specific Initiatives of Regional Importance

Conclusions and way forward

Chapter 20: Looking to the future

Index

Table of contents 269 269 269 272 281 285 291 291 292 295 311 312 320 320 322 325 333 338 338 339 344 347 354 356 361 361 362 368 379 381

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the extreme vulnerability of our national health systems. It has shown once more that investing in health care is key to economic prosperity and to progress in human development. As much as COVID-19 has exposed our weaknesses, it has also brought our strengths to the fore.

There has been unprecedented collaboration between countries and a massive show of solidarity with vulnerable communities and societies. The COVID-19 pandemic has made governments, policy-makers and health practitioners realise that to achieve and sustain Universal Health Coverage we must be prepared to respond quickly in tackling pandemics. The book is timely, as it comes at a stage when we are taking stock of the efforts we have made in the past to make our health system more resilient – some with great effect, and some less so. This publication covers a five-year period dating back from 2015. It reflects major successes but also many remaining challenges with regard to South Africa’s health system. It follows the first publication which covered the period 2009 to 2014.

The health system in South Africa remains divided and maintains its two-tier status more than 25 years into democracy. During 2019, the Lancet Commission released a report on quality of health care in South Africa, with detailed diagnosis, and recommendations to improve the quality of health care in the country and made a case that increase in coverage will not be sufficient to improve health outcomes. The Health Market Inquiry also released its final recommendations, citing many challenges in the private health sector, and market failure.

The policy reforms that ensued over the last decade involved the production of a green paper and white paper, which served as a prelude to the production of the National Health Insurance Bill. This aims to fulfil our constitutional obligation to protect the right to health care for all. It followed a far and wide consultative process through public hearings across all provinces. The public participation included submissions from various stakeholders and ordinary members of the public.

As some commentators have noted, implementation will not be easy, but the National Health Insurance will become a reality and we are committed to ensuring that our people receive quality health care and are not discriminated against based on lack of affordability.

South Africa still has the largest HIV epidemic in the world, with 8 million people living with HIV. South Africa is also still burdened by tuberculosis and accounts for 3% of cases worldwide. While we have made great progress in tackling HIV and TB – focusing on prevention, testing and treatment – we have fallen behind in reaching our 90/90/90 treatment targets and we will be focusing and quickening our pace to meet the 2025 treatment targets.

South Africa has also worked across partner institutions in the continent to tackle obstacles together. For example, we are working with the World Health Organization on the establishment of an mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub in South Africa that will use a hub-and-spoke model to transfer a comprehensive technology package and provide appropriate training to selected manufacturers in other African and low- and middle-income countries. Africa has the ability, the scientists and the industries to provide the vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics needed to manage the African health challenges. We cannot continue being consumers of medical countermeasures for diseases produced at high prices that are not affordable to the continent.

Over the next five years, the Department has set the target to increase life expectancy to at least 66.6 years, and to 70 years by 2030. Additionally, it aims to progressively achieve Universal Health Coverage, and financial risk protection for all citizens seeking health care, through application of the principles of social solidarity, cross-subsidisation, and equity. These targets are consistent with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals to which South Africa subscribes, and Vision 2030, described by the National Development Plan, that was adopted by government in 2012.

A stronger health system, and improved quality of care will be fundamental to achieve these impacts. The Department’s Strategic Plan 2020/21–2024/25 is firmly grounded in strengthening the health system. The plan lays out our strategies to each of the outcomes geared to strengthen the health system, improve quality of care, and respond to the quadruple burden of disease in South Africa. We will join hands with our Provincial Departments of Health and partners to achieve these outcomes. We will also collaborate with other government departments to reduce the impact of social determinants of health, and forge strong partnerships with social partners to improve community participation to ensure that the health system is responsive to their needs.

The analysis and recommendations that have come from this huge effort, involving so many commentators, experts, managers and policy-makers will surely assist us on the road to achieving the country’s ambitious goals.

Dr Joe Phaahla, Minister of HealthMalebona Precious Matsoso

Director of the Health Regulatory Science Platform, Wits Health Consortium and previously Director-General of the South African National Department of Health, and served on the WHO Executive Board for a three-year term, acting both as Vice-Chairperson and as Chair. Co-chair Intergovernmental Negotiating Body for the WHO convention on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

Previously published over 80 journals, articles, book chapters, reports and guidelines on pharmaceuticals, and on South African health policy. Co-editor of The South Africa Health Reforms 2009–2014: Moving towards UHC (Juta, 2015); Co-author of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (WHO, 2021). Peer-reviewed journal articles include High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution (Lancet, 2018), COVID-19: how a virus is turning the world upside down (BMJ, 2020).

Lindiwe Makubalo

Assistant Regional Director, World Health

Organization Africa Regional Office. Dr Makubalo has served on numerous scientific and advisory boards, bodies and groups such as the South African Medicines Control Council, national ethics councils, several data systems boards, expert group on Oncocerciasis Control, Strategic advisory group on malaria eradication, and as African representative on the UNITAID Board. Most recently she held a diplomatic role as Minister, Health Expert for the South African Government to the United Nations in Geneva where she participated and led development of important policy and resolutions such as the NCD indicators monitoring and Ebola resolutions as chair, along with other important activities to strengthen global policy for SDGs and health emergencies.

Emeritus Professor in Health Systems and Public Health. The former Head of the Department of Global Health in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences has been a dental practitioner and an academic during a long and very illustrious career, and served on various professional and educational bodies for many years as well. At Stellenbosch University, which he joined in 1996 as head of the Department of Community Dentistry, he has consistently tried to address such inequalities in health care. He became Associate Dean of the Faculty in 2000 and Executive Head of the Department of Interdisciplinary Health Sciences in 2006. Chikte has played a key role in helping to advance this process of transformation, both as an academic, a Senator and a member of the University Council.

Country Director and Extraordinary Professor, Department of Global Health, Stellenbosch University, and previously Deputy Director-General: National Department of Health. Over 100 peer-review journal articles on all aspects of public health and over 40 other publications, including book chapters and public articles. This includes co-author of the book Mental Health Policy Issues for South Africa (MASA, Cape Town, 1997), Textbook of International Health, 3rd ed.

(Oxford University Press. NY, 2009), Textbook of Global Health, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press. NY, 2017). Recent peer-reviewed articles include lead author of Health benefit packages: moving from aspiration to action for improved access to quality SRHR through UHC reforms (Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020), Towards an AIDS-free generation by 2030: how are South African children, adolescents, caregivers and health care workers coping with HIV? (South African Journal of Psychology. 2021) and co-author of The impact of implementing the 2016 WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience on perinatal deaths: an interrupted time-series analysis in Mpumalanga province, South Africa (BMJ Glob Health. 2020).

Vice President Health Systems and Policy and Global Project Director of the USAID Local Health System Sustainability Project, Abt Associates, MD 20852, USA. Has published over 40 peer-reviewed publications, chapters, editorials, and articles on topics covering health policy, health financing, health systems, HIV and TB; co-editor of The South Africa Health Reforms 2009–2014: Moving towards UHC (Juta, 2015); co-editor of Special Series Experiences in Promoting Health Finance and Governance Reforms (Health System Reform, 2018). Author of chapter on Primary health care and international development assistance in ‘International perspectives to primary care research’ (CRC Press 2015). Recent peer-reviewed articles include lead author of: editorial Tuberculosis control in South East Asia: vignettes from China, Cambodia and Myanmar (Health Policy and Planning, 2017); Commentary Financing health systems to achieve the health Sustainable Development Goals. (Lancet Global Health, 2017); Article Health sector governance: should we be investing more? (BMJ Global Health, 2017).

Professor Gill Walt, Emeritus Professor of International Health Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Professor Craig Househam, Previously Head of Department, Western Cape Department of Health.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) South Africa Office

Wits Health Consortium (Pty) Limited (WHC), wholly owned by the University of the Witwatersrand

Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (South Africa), Government of UK

Board of Healthcare Funders

Andy Gray, BPharm, MSc(Pharm), FPS, FFIP, Senior Lecturer Division of Pharmacology, Discipline of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Annibale Cois, MEng, MPH, PhD, Researcher Department of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

Ashraf Kagee, PhD, MPH, Professor of Psychology Stellenbosch University

Barry Kistnasamy, Mmed Comm Health, Compensation Commissioner National Department of Health

Beth Englebrecht, MbChB, MFam Med, DHA, DCH

Emeritus Head of Health, Western Cape Government; Adjunct Assistant Professor, UCT School of Public Health, UCT, School of Public Health

Boitumelo Mashilo, MCom (Economics of Trade and Investment) Head: Infrastructure Advisory Services, Government Technical Advisory Center

Candy Day, BSc Pharm, MMedSci (Clinical Pharmacology), Technical Specialist Health Systems Trust

Carmen Sue Christian, PhD, Senior Lecturer Department of Economics, EMS Faculty, University of the Western Cape

Crick Lund, MSocSci (Clin Psych), PhD, Professor of Global Mental Health King’s College London and University of Cape Town

Dudu Shiba, Bcur, MPH, Deputy Director: Mental Health and Substance Abuse National Department of Health

Dumisani Hompashe, PhD (Economics), Senior Lecturer Department of Economics, Faculty of Management & Commerce, University of Fort Hare

Eric Buch, MBBCh, MSc(Med), FFCH(CM)(SA), DTM&H, DOH, Professor, Health Policy and Management, School of Health Systems and Public Health, University of Pretoria and The Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA), Cape Town

Gaurang Tanna, BSc, BSc (hons) Computer Science, MPH Senior Program Officer, TB, South Africa, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

Gertrude Mngola, BPharm, MPH, Health Products Grant Specialist South African National AIDS Council

Giovanni Perez, Chief Director, Cape Metro Western Cape Government: Health and Wellness

Gladys Bogoshi, BSc Physiotherapy, MSc Physiotherapy( Neurology), MPH, CEO Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital

Helen Schneider, MBChB, MMed, PhD, Professor School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape

Jabulani Mndebele, Chief Director, District Health Service KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health

Jonatan Daven, BSc (Development Studies), MSc (International Relations) MSc (Public Health), Director: Health, National Treasury, GoSA

Kamy Chetty, MD, Masters (Urban and Regional Planning), Chief Executive Officer, National Health Laboratory Service

Keith Cloete, MBCHB(UCT), DCH(SA), DHM(UCT), Head of Department Western Cape Government: Health

Kerrigan Mcarthy, MBBCh, DTM&H, FCPath (Micro), MPhil (Theology), PhD (Pub lic Health), Pathologist, Centre for Vaccines and Immunology, National Institute for Communicable Disease

Kholekile Malindi, PhD, Lecturer Department of Economics, Stellenbosch University

Kwanele Asante, BA, LLB, MSc, Law and Policy Advisor South African Non-Communicable Disease Alliance

Laura Angeletti-du Toit, PhD Eng. La Sapienza, Rome, Italy, SACAP Pr Arch., Italian Engineering Council Pr Building Eng. Western Cape Government Health and Wellness

Leslie London, MB ChB, DOH, M Med (PHM), MD, Professor of Public Health Medicine, University of Cape Town

Lilian Dudley, PhD, FFPHM, MSc, MBChB, Emeritus Assoc Professor in Health Systems and Public Health, University of Stellenbosch, Dept of Global Health

Lindi Makubalo, Assistant Regional Director, World Health Organization

Lucy Gilson, BA (Hons), MA, PhD, Professor, Health Policy and Systems School of Public Health, University of Cape Town and Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Lungiswa Nkonki, PhD, Senior Lecturer, Department of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

Marc Mendelson, PhD, MBBS, Professor, Infectious Diseases Groote Schuur Hospital, University of Cape Town

Mark Blecher, PhD, M.Med, MPhil, MBBCH, Chief Director: Health and Social Development, National Treasury, GoSA

Marumo Maake, MM Public Policy BTech: Finance and Accounting Chief Director: Public Sector Remuneration Analysis and Forecasting, National Treasury, GoSA

Melvyn Freeman, MA (Clin Psych), Extraordinary Professor Department of Psychology. University of Stellenbosch

Mohamed Jeebhay, MBChB DOH MPhil (Epi) MPH (Occ Med) PhD FCPHM (Occ Med) SA, Professor and Head of Occupational Medicine School of Public Health, University of Cape Town

Muzimkhulu Zungu, MBChB, Mmed Comm Health, FCPHM, DOMH Head of Workplace HIV TB, National Institute for Occupational Health

Nikhil Khanna, BA (Economics), MPP

Programme Manager: Sustainable Health Financing, Clinton Health Access Initiative, South Africa

Nombulelo Magula, PGDip, MBA, MSc, B. Social Science Hons WHO COVID-19 Emergency Response Consultant and Public Health World Health Organization, South Africa

Noxolo Madela, MSSc, Budget Analyst: Health, National Treasury, GoSA

Nwabisa Daniels, Bcom Hons (Economics), Analyst: Capital Project Appraisals Government Technical Advisory Center

Olga Perovic, MD, DTM&H, FCPath (Micro), MMED (Micro) Principal Pathologist, National Institute for Communicable Disease, a division of NHLS

Pamela Naidoo, PhD, CEO; Extraordinary Professor SU Heart & Stroke Foundation SA; Stellenbosch University

Patrick Moonasar, DrPH, Director Malaria and Vector-Borne Diseases Zoonotic Diseases, National Department of Health

Peter Barron, Honorary Professor, School of public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

Precious Matsoso, BPharm, PDHM, LLM, Honorary Lecturer, Department of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, Director of the Health Regulatory Science Platform, Wits Health Consortium, University of the Witwatersrand

Rajen N Naidoo, MBChB; DOH; MPH (Occ Med); PhD Professor and Head of Discipline: Occupational and Environmental Health School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Rajesh Patel, MBChB, FCFP, MPH, Head: Health System Strengthening Board of Healthcare Funders

Ramphelane Morewane, B Dent Ther, B Tech, PG Dip, Msc, Chief Director, National Department of Health

Raveen Naidoo, BTEMC, MSc Cardiology, MSc Emergency Medicine Director: EMS & Disaster Medicine, National Department of Health

Rene English, MBCHB, MMed, FCPHM(SA), PhD , Director: EMS & Disaster Medicine, National Department of Health

Rita Thom, MBChB (UCT); DCH (CMSA); FFPsych (CMSA); PhD (Wits) Visiting Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of the Witwatersrand

Ritika Tiwari, PhD, PGDM, BSc (Hons), Postdoctoral Fellow, Division of Health Systems and Public Health, Department of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

Robert (Bob) Fryatt, MBBS, MD, MOH, MRCP (UK), FFPH, Vice President Health Systems and Policy, Abt Associates, Abt Associates

Robyn Hayes Badenhorst, MBA expected completion 2024. UP Logistics. Project Management. Head: Group Strategy, Wits Health Consortium

Ronelle Burger, PhD (Economics), Professor, Economics Department, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, Stellenbosch University

Russell Rensburg, BCom Finance and Economics, Director Rural Health Advocacy Project

Sandhya Singh, M(Com Path), Director: Non-Communicable Diseases Department of Health

Sasha Stevenson, BA, BA (Hons), LLB, LLM, Head of the Health Rights Programme, SECTION27

Shabir Banoo, BPharm, PhD, Chief Technical Specialist: Pharmaceutical Policy and Pro grammes, Right to Care; Department of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

Shoni Mulibana, BPharm, MPharm, MPH, Manager: Pharmaceutical Services Programmes, Right to Care

Shrikant Peters, BA (PPE), MBChB, MMed (Public Health), FCPHM Manager: Medical Services, Public Health Medicine Specialist Groote Schuur Hospital, Western Cape Department of Health Department of Public Health & Family Medicine, University of Cape Town

Sifiso Phakhati, Bcur(I ET A), Advanced Psychiatric Nursing Former Director: Mental Health and Substance Abuse, National Department of Health

Siphiwe Mndaweni, BA, MSc, MBChB, Diploma in Health Systems Management and Executive Leadership, Chief Executive Officer, Office of Health Standards Compliance

Spo M Kgalamono, MBCHB, DOH, FCPHM (Occ Med), MMed (Occupational Medicine), DPH, Executive Director, National Institute for Occupational Health

Steve Letsike, Executive Director, Access Chapter 2 and Chairperson of the Commonwealth Equality Network

Sue Putter, DipPharm, MPharm, MPA, Deputy Chief of Party and Senior Health System Strengthening Specialist, USAID Global Health Supply Chain - Technical Assistance Programme

Sumaiyah Docrat, BSc (Hons) MPH (Health Economics) PhD, Global Health Specialist: Health Economics, Systems and Policy, Independent Scholar

Tamlyn Roman, PhD, Programme Manager, Clinton Health Access Initiative, South Africa

Terence Carter, MBCHB(Natal), DCH(SA), DHM(UCT), Technical Assistant, Clinton Health Access Initiative, South Africa

Theodosia Adom, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

Thulani Clifford Masilela, Master of Arts (MA), Clinical Psychology; Postgraduate Diploma in Health Management, Outcomes Facilitator (Senior Sector Specialist) for Health, Department of Planning Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME), Presidency, Republic of South Africa

Thulani Matsebula, BA, MSc, Senior Economist: Health, World Bank, Southern Africa

Thulile Zondi, BNUR, MPH, Chief Director, Health Information, Research, Monitoring & Evaluation, National Department of Health

Tsakani Furumele, BSc (Medical Laboratory Science), MSc (Zoology), MPH (Epidemiology and Biostatistics), Director: Communicable Disease Control, National Department of Health

Usuf Chikte, PhD, Emeritus Professor in Health Systems and Public Health Department of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University

Vishal Brijlal, BCom Economics, Former Advisor on Health Financing (NDoH) and Senior Director, Clinton Health Access Initiative, South Africa

Wezile Chita, MPH, PhD, Assistant Dean, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand

Yogan Pillay, PhD, Country Director and Extraordinary Professor Clinton Health Access Initiative, South Africa. Department of Global Health, Stellenbosch University

AfCFTA African Continental Free Trade Area

AGSA Auditor-General of South Africa

AMR Antimicrobial Resistance

AMS Antimicrobial Stewardship

ART Antiretroviral Therapy

ARV Antiretroviral

CCMDD Centralised Chronic Medicine Dispensing and Distribution

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CHAI Clinton Health Access Initiative

CHW Community Health Worker

CMS Council for Medical Schemes

COPC Community-Oriented Primary Care

COVAX COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access

CSG Child Support Grant

CSOs Civil Society Organisations

CUPS Contracting Units for Primary Health Care

CVD Cardiovascular Disease

DBE Department of Basic Education

DCST District Clinical Specialist Team

DDM District Development Model

DEL Department of Employment and Labour

DHIS District Health Information System

DHS District Health System

DM Diabetes Mellitus

DMRE Department of Mineral Resources and Energy

DO District Office

DRG Diagnosis-Related Group

DR-TB Drug-Resistant TB

EML Essential Medicines List

EMS Emergency Medical Services

EMT Emergency Medical Team

EOC Emergency Operating Centres

ESMS Electronic Stock Management Systems

EtD Evidence-to-Decision

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GERMS-SA Group for Enteric, Respiratory and Meningeal Disease Surveillance in South Africa

GFATM Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

GHS General Household Survey

GLASS Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System

GMP Good Manufacturing Practice

GP General Practitioner

HDI Human Development Index

HE Health Establishment

HIS Health Information System

HMI Health Market Inquiry

HOD Head of Department

HPCSA Health Professions Council of South Africa

HPL Health Promotion Levy

HPRS Health Patient Registration System

HRH Human Resources for Health

HTA Health Technology Assessment

ICRM Ideal Clinic Realisation and Maintenance

ICESCR International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

IHI Institute for Health Improvement

IHR International Health Regulations

ILO International Labor Organization

iMMR Institutional Maternal Mortality Ratio

IMR Infant Mortality Rate

IMS Incident Management System

IMT Incident Management Team

IP Intellectual Property

IPC Infection Prevention and Control

IPCHS Integrated People-Centred Health Service

IUSS Infrastructure Unit Support Systems

IVDs In Vitro Diagnostics

JEE Joint External Evaluation

LE Life Expectancy

MAC Ministerial Advisory Committee

MAC-AMR Ministerial Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance

MCC Medicines Control Council

MCH Maternal and Child Health

MDGs Millennium Development Goals

MEC Member of the Executive Council

MNORT Multisectoral National Outbreak Response Team

MNS Mental, Neurological and Substance Use

MPTTT Medical Products Technical Task Team

MRC Medical Research Council

MRU Monitoring and Response Unit

NAPHISA National Public Health Institute of South Africa

NATHOC National Health Operations Centre

NATJOC National Joint Operations Centre

NATJOINTS National Joint Operational and Intelligence Structure

NCCC National COVID-19 Command and Control Council

NCD Non-Communicable Disease

NCR National Cancer Registry

NCS National Core Standards

NDMC National Disaster Management Centre

NDoH National Department of Health

NDP National Development Plan

NEMLC National Essential Medicines List Committee

NGO Non-governmental Organisation

NHA National Health Accounts

NHC National Health Council

NHC-Tech National Health Council Technical Committee

NHI National Health Insurance

NHLS National Health Laboratory Services

NIAMM National Infrastructure Asset Maintenance Management

NICD National Institute of Communicable Diseases

NIOH National Institute for Occupational Health

NMRAs National Medicines Regulatory Authorities

NQIP National Quality Improvement Plan

NRAs National Regulatory Authorities

NSC National Surveillance Centre

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OHS Occupational Health Services

OHSC Office of Health Standards Compliance

OSD Occupation Specific Dispensation

PDoH Provincial Department of Health

PEPFAR

The United States President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief

PFMA Public Finance Management Act

PHC Primary Health Care

PHDC The Western Cape Provincial Health Data Centre

PLHIV People Living With HIV/Aids

PMB Prescribed Minimum Benefit

PPE Personal Protective Equipment

PSDP Public Sector Dependent Population

PUPs Pick-up Points

SAHPRA South African Health Products Regulatory Authority

SAM Severe Acute Malnutrition

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

SDH Social Determinants of Health

SECEDH Social, Economic, Commercial and Environmental Determinants of Health

SOP Standard Operating Procedure

SSP Stop Stockouts Project

STGs Standard Treatment Guidelines

STIs Sexually Transmitted Infections

SVS Stock Visibility System

TAC Treatment Action Campaign

TB Tuberculosis

U5MR Under-Five Mortality Rate

UHC Universal Health Coverage

UMIC Upper-Middle-Income Country

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

VUCA Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity

WBOT Ward-Based Outreach Team

WBPHCOT Ward-Based Primary Health Care Outreach Team

WISN Workload Indicators of Staffing Need

WoGA Whole of Government Approach

WoSA Whole of Society Approach

Figure 2.1 Figure 2.2 Figure 2.3 Figure 2.4 Figure 2.5

Figure 2.6 Figure 2.7 Figure 2.8 Figure 2.9

Figure 2.10 Figure 2.11 Figure 2.12 Figure 2.13

Figure 2.14 Figure 3.1 Figure 3.2 Figure 3.3 Figure 3.4

Figure 4.1 Figure 4.2 Figure 4.3 Figure 4.4 Figure 5.1

Figure 5.2 Figure 5.3 Figure 4.4 Figure 5.5 Figure 5.6

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.8 Figure 7.1

Population age structure by single years, 2020

Population distribution by race, 2020

Life expectancy at birth: South Africa 2002–2021

Number of natural and unnatural deaths: South Africa 2000–2020

Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) and Under-5 Mortality Rate (U5MR): South Africa 2002–2020

Proportion of children under five years born with low birth weight: South Africa 2015–2018, by province

Proportion of children under five years with severe acute malnutrition: South Africa 2015–2018, by province

Number of maternal deaths by underlying cause: South Africa 1997–2017

Prevalence of bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB among adults 15 years and older: South Africa 2018, by sex and by age group

Incidence of TB: South Africa 2000–2020

HIV Prevalence: South Africa 2017, by sex and age group

HIV Incidence: South Africa 2017, by sex and age group

Persons suffering from chronic health conditions: South Africa 2015 and 2019, by sex

Proportion of ever-partnered women aged 18 and older who have experienced physical, sexual or emotional violence committed by any partner in the past 12 months: South Africa 2017, by province

Schema of social determinants of health framework

Real Gross Domestic Product 2015–2020, annual percentage change

Health care expenditure 2015–16 to 2019–20 3G/4G LTE/5G population coverage and smartphone penetration in South Africa from 2015 to 2020

Primary health care components

Per capita expenditure on PHC and percentage of total health expenditure on PHC, 2010/11 to 2019/20 2019/20 PHC utilisation rates and average annual change between 2015/16 and 2019/20 by province

Ten elements of Cape Town Metro COPC

Incidence, new and relapse TB cases notified, HIV-positive TB incidence

TB care cascade, South Africa, 2018

Number of new and relapse notified TB cases per year, 2016–2020

Changes in HIV new infections, deaths and incidence/ prevalence ratio in South Africa 2010 to 2019

HIV testing and treatment cascade 2019, South Africa, with gaps to the three 90s targets

HIV tests done by month, in public health facilities, between March and December 2019 and 2020

Maternal mortality in public sector institutions, South Africa 2005 to 2019

National couple year protection rate

Proportion of provincial health expenditure by programme 2004/5 – 2019/20

Figure 8.1a

Figure 8.1b

Figure 8.2

Figure 9.1 Figure 9.2 Figure 9.3 Figure 9.4 Figure 9.5 Figure 9.6

Figure 11.1a-b.

Figure 11.2 Figure 11.3

Figure 12.1 Figure 12.2

Figure 12.3 Figure 12.4 Figure 12.5 Figure 12.6 Figure 13.1 Figure 13.2 Figure 13.3 Figure 13.4

Figure 13.5

Figure 13.6 Figure 13.7

Figure 15.1

Figure 16.1 Figure 16.2 Figure 18.1

Figure 18.2 Figure 18.3

Figure 18.4

Figure 18.5 Figure 18.6

Figure 18.7 Figure 18.8

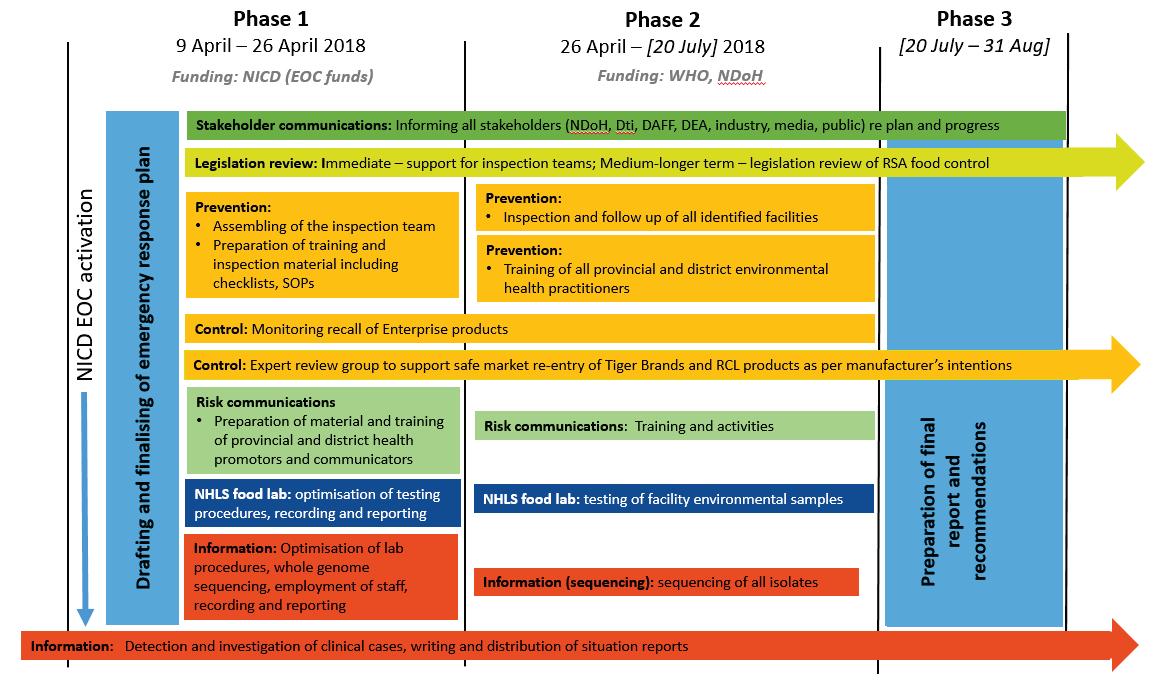

Structure and functions of joint WHO-RSA listeriosis incident management team

Phase 1, 2 and 3 of the listeriosis public health emergency response plan to halt the listeriosis outbreak and prevent future outbreaks National and provincial structures supporting SARS-CoV-2 responses as of October 2021 The emergency operations centre

Percentage of deaths from various causes of mortality

Mortality from NCDs in South Africa

WHO’s best buys

Trends in selected NCD risk factors

What are South Africans eating?

Percentage of comorbidities among in-hospital COVID-19 deaths, by age group, South Africa

Pulmonary tuberculosis in Black miners and silicosis in Black South African gold miners at autopsy (1975–2019)

Injuries reported in mines for the five-year period (2014–2018)

Injuries reported among women in the mining industry (2001–2019)

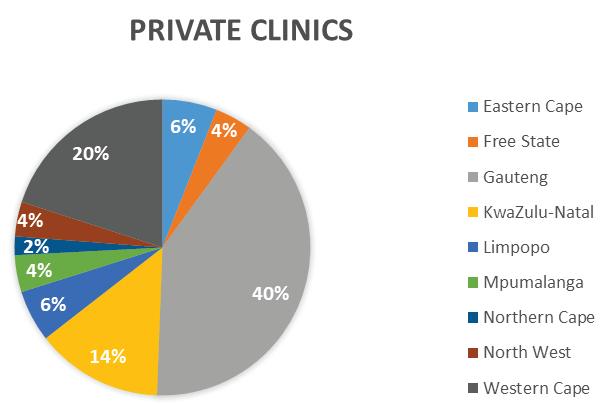

Provincial spread of private health care facilities in 2020

Type of health care facilities consulted first by households in 2015 and 2020

State of health infrastructure

Cumulative number of facilities that achieved an Ideal Clinic status

Compliance of health facilities with NCS infrastructure requirements

IUSS users by country and sessions between 2018 and 2020

Conceptual framework for a high-quality South African health system

Proposed National Strategic Framework

The OHSC value chain

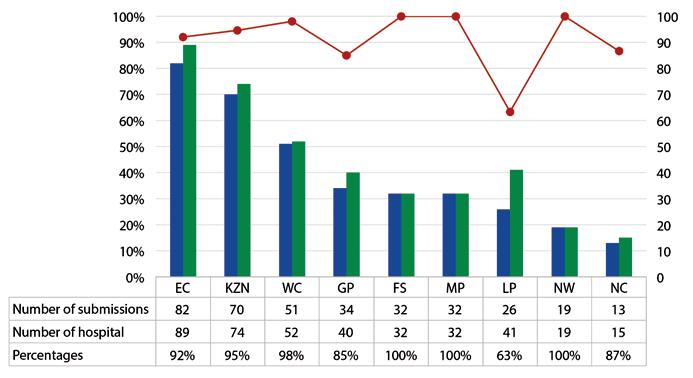

Annual returns submissions by hospitals in South Africa’s provinces in 2019/20

The total number of annual inspections by the OHSC per financial year

PDSA Model for Improvement

Themba hospital percentage of patients triaged within 10 minutes of arrival within the maternity admission room

The dominant relationships of everyday governance practice within the South African health system (2015–2020)

Health system accountability relationships Medicine shortages reported by patients

Provincial health spending as a percentage of budgets, 2015/16 to 2020/21

Government health spending as percentage of GDP and as percentage of total government expenditure

Health financing indicators and life expectancy compared to other UMICs, 2017

The Africa Scorecard on Domestic Financing for Health, 2017, UMIC countries

Percentage deviation from the national public health spending per capita (uninsured)

Private medical scheme expenditure by factor of provision, 2009–2019

Main budget balance, Budget 2021

Provincial health budgets, 2000/01 – 2023/24

Table 2.1

Table 3.1

Table 3.2

Table 4.1 Table 4.2 Table 5.1 Table 5.2

Table 5.3 Table 5.4 Table 5.5

Table 6.1 Table 8.1

Table 8.2 Table 8.3

The 10 leading underlying natural causes of death per age groups in South Africa

South Africa’s HDI trends (based on consistent time series data and new goalposts)

List of the key actions in South Africa within the first 14 days (March 5–19) of COVID-19

Core strategic and operational levers for PHC

Operational levers addressed

Key TB indicators in South Africa 2015 to 2020

Key HIV indicators from 2015 to 2022, South Africa (Thembisa Model)

The three 90s, South Africa, 2015 to 2022

Maternal and Child Mortality 2015 to 2020

Deliveries and terminations in adolescent girls aged 10–19 in the public sector, South Africa 2017/18 to 2021/22

Medicines availability data sources

Core capacities required to implement IHR, and South African scores during the JEE process, 2017

Significant communicable disease events and health emergencies, 2015–2020

Strategic framework and activities to preserve effectiveness of antimicrobials, improve use of antibiotics and strengthen effective management of antibiotic resistant organisms according to the National AMR Strategy Framework

Table 9.1 Table 9.2

Table 9.3 Table 11.1 Table 11.2 Table 11.3

Table 11.4

Table 11.5 Table 11.6 Table 11.7 Table 12.1 Table 12.2 Table 12.3 Table 15.1

Table 17.1 Table 17.2 Table 17.3

Goals and targets in the 2013–2017 NCD Strategic Plan

Most frequently reported cancers (National Cancer Registry: 2015–2018)

Guiding principles for the implementation of the NSP

Legislation on Occupational Health and Safety

Legislation on Occupational Health and Safety for specific sectors

Occupational diseases reported to the Compensation Fund for the non-mining sector in South Africa, 2016/17–2019/20

Occupational diseases per commodity reported in annual medical reports by South African mines (2018 and 2019)

Occupational diseases reported and certified for the mining sector of South Africa (2019–2020)

Public sector health worker COVID-19 disease data per province (March 2020–mid August 2021)

Societies of the different OSH professionals

Provincial spread of public health care facilities

Bed capacity rate per 1 0 dependent population

Waiting times per level of care

Strengthening governance through new approaches to managing meetings

Available data sources for HRH planning in South Africa

HRH studies undertaken in South Africa

2019 Public sector health workforce – Inter-provincial variation in staffing ratios per 100 0 public sector population

Table 17.4

Table 17.5

Table 18.1 Table 18.2 Table 18.3 Table 18.4

Table 18.5 Table 18.6

Table 18.7 Table 18.8 Table 18.9 Table 18.10

Table 18.11 Table 18.12

Medical Specialists in South Africa (gender break up) in 2019

Demographics of sub-specialists who were successful in colleges of medicine examinations in South Africa

Progress with NHI

Consolidated health spending (public and private sectors)

Provincial health budgets

Key health financing indicators in upper-middle-income countries, 2018

PHC expenditure per capita in highest and lowest districts (real 2019/20 prices)

Accruals and payables not recognised (unpaid accounts), 2015/16 – 2019/20

PDoH compensation of employees’ expenditure, 2015/16 – 2023/24

Trends in health personnel numbers in public sector

Distribution of critical skills per 100 0 uninsured population

Goods and services spending per capita (uninsured), 2015/16 – 2023/24

Medico-legal claims contingent liability, 2015/16 – 2020/21

Summary of health allocations for COVID-19 in the 2020 special adjustments budget

In the first book covering South Africa’s health reforms between 2009 and 2014, we noted that initiatives in South Africa on universal coverage started in the 1920s. The book reviewed the five-year period to 2014 which coincided with the end of the timeframe of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and concluded that progress had been made in several key areas, but that many challenges remained.

It was also a phase of transition from MDGs to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). During this period progress was made in improvement in health outcomes as reflected by significant increases in life expectancy, as well as reduced maternal and child mortality. The country has the largest HIV epidemic in the world with the largest antiviral treatment programme. The period covered in the first book showed a decline in new infections, and was associated with life expectancy at birth increasing. The establishment of the Office of Health Standards Compliance provided for a systematic, independent monitoring mechanism and recommendations for redress where services failed to meet required standards. There had been progress in improving the availability of essential medicines through price reduction and increased availability of life-saving antiretroviral and other medicines. The country had seen improvements in the collection, analysis and use of information and in rolling out reforms across districts and hospitals. On the health workforce, progress had been made in developing certain specialist cadres, increasing production of health workers (doctors) and formalising the policies on community health workers as essential members of the team for primary health care level. The National Department of Health had rolled out frontline service reforms to improve primary health care services and strengthen community participation through ward-based outreach teams (WBOTs).

The authors also noted the many challenges still facing the country in 2014. The country still faced unprecedented challenges in getting over five million people on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and keeping them adherent, and of improving tuberculosis (TB) prevention and control programmes to the point of successfully treating at least 85% of all TB patients diagnosed. There were also

Malebona Precious Matsoso, Usuf Chikte, Lindiwe Makubalo, Yogan Pillay, Robert (Bob) Fryattmany challenges remaining to improve reproductive, maternal and child health and in mobilising a larger workforce, including improving access to general practitioners and in improving the functioning of WBOTs. Progress, however, was described as being slow on improving leadership and management competencies. Many more challenges were identified – around hospital management, further improvement in the provision of quality services, giving greater voice to communities, intersectoral action and the slow pace of reforms related to the implementation of National Health Insurance (NHI). The authors called for increased efforts to document, monitor and evaluate interventions to improve future planning and implementation.

Objectives of this book: Since the first book was completed, the SDGs (2015–2030) were launched. This second edition aims to document key events and initiatives between 2015 and 2020 and consider the future challenges and implications for the different institutions, practitioners and agencies involved in improving the health of people living in South Africa. The book will be a first-hand account of the ongoing story on the transformation of health and health policy in South Africa. As before, we have brought together, for each chapter, a mix of policy-makers and implementers to work with academics and researchers. This approach seeks to strengthen the links between research, evidence and policy and improve the role of science in implementation.

Intended readership: There is considerable attention on South Africa given the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the COVID-19 response, and South Africa’s growing role in global and regional health. The aim is for the book to be used by all major schools of public health that study global health, and in academic centres that host courses and conduct research on comparative social policies.

Structure: The content and structure of each chapter will start with the challenges facing South Africa in 2015; then provide a description of the initiatives that were underway or that were initiated to improve the situation between 2015 and 2020. There will be some analysis of how well these initiatives progressed, with some examples of successes and descriptions of challenges or remaining problems. There will then be a summary of the overall progress by 2020, with the authors providing some recommendations or reflections going forward.

Key themes: Four main themes run throughout the book. These are:

Health Reform: The book is about health reforms in South Africa between 2015 and 2020 – we are not looking simply for a description of the important issues in each chapter, but whether reforms took place or not. Our definition of reform is a traditional one from the World Health Organization (WHO): ‘Health sector reform deals with fundamental change of processes in policies and institutional arrangements of the health sector, usually guided by the government’.

Gender: We see this as important for all chapters, as gender inequality and discrimination faced by women and girls puts their health and well-being as well as that of their families at risk. The United Nations refers to gender as ‘the social attributes and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between women and men and girls and boys’.

Equity: We will highlight the trends on health equity during this period. Again, taken from the WHO: ‘Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically. Health inequities entail a failure to avoid or overcome inequalities that infringe on fairness and human rights norms’.

Community engagement: We see this as an important ingredient of success for health reforms. The WHO has defined community engagement as ‘a process of developing relationships that enable stakeholders to work together to address health-related issues and promote well-being to achieve positive health impact and outcomes’.

Intersectoral collaboration: We see intersectoral collaboration as a key action government should adopt both to address broader determinants of health and to improve the effectiveness of health programmes. This was at the core of the declaration on primary health care in the Alma-Ata Declaration and in the more recent Almaty Declaration.

Chapter 2: (Demographic and Health Trends: 2015–2020.) The chapter provides a summary on the recent demographic trends in South Africa, including latest data on the various aspects of equity, determinants of health, health status and access to services that are critical to improving health and well-being.

Chapter 3: (Social, Economic and Environmental Determinants.) The chapter focuses on the main challenges facing South Africa in this period, in particular the macroeconomic situation, poverty, income inequality and unemployment, education and social security, nutrition and hunger, built environment, and safety and security. There is then a commentary on the lessons learned from the coordinated and intersectoral actions developed in response to COVID-19, including what the intersectoral structures achieved at national, provincial and local level, using examples that applied a social determinants of health lens. Finally, the chapter considers the role of technology and regulation, ending with some recommendations for the future.

Chapter 4: (Primary Health Care.) The chapter describes the key contextual factors impacting PHC, and then describes the national programmes and interventions on PHC active in the five-year period. These include Ward-Based Primary Health Care Outreach Teams (WBPHCOTs), District Clinical Specialist Teams (DCSTs), Ideal Clinic Realisation and Maintenance, Centralised Chronic Medicines Dispensing and Distribution Programme (CCMDDP), PHC e-health programme, and private sector contracting. The authors then summarise the main PHC performance indicators, covering financing, health workforce and PHC utilisation, and provide case studies of promising bottom-up health system strengthening, including Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) in Tshwane, sub-district models (KwaZulu-Natal sub-district management model, and the 3-feet model in Limpopo and Mpumalanga) and the social accountability model of Ritshidze Community-Led Monitoring of PHC. The chapter ends with a summary of remaining challenges, and conclusions on the way forward.

Chapter 5: (National Health Programmes.) In this chapter there is a focus on three health issues which are used to illustrate the successes and failures of the health system’s response between 2015 and 2020. These are HIV/AIDS, TB, and maternal and child health. The review is complemented by two case studies. The first is the Western Cape Department of Health’s response to TB using lessons learnt from the COVID-19 response and incorporating a wholeof-society approach. The second illustrates gender issues in relation to access to health services and human rights.

Chapter 6: (Accelerating Access to Medicines and Health Technologies.) The chapter focuses on three key areas of national policy and implementation, namely: the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) and re-engineering the regulatory framework for health products; Scaling differentiated service delivery models for chronic medicines; and Antimicrobial Resistance – Policy solutions for effective governance.

Chapter 7: (Hospital Services.) The chapter provides an update on relevant national legislation and polices, including the role of hospitals envisioned under the NHI. It then goes on to assess in more detail the increased governance responsibilities at hospital level in the context of the NHI purchaser/provider split and the different roles that will be played by provincial and district management. The chapter then explores the need for adherence to the King 4 governance principles, covering ethical organisational culture and the Protocol on Corporate Governance in the Public Sector. Sections then focus on community engagement and accountability and strengthening financial and supply chain management, and decentralisation of management through functional business units. The chapter discusses progress with hospital governance and policy and patient-centred care and clinical governance.

Chapter 8: COVID-19 and Emergencies. In this chapter, we evaluate why disaster risk reduction and preparedness foster health system resilience. We reflect on the global context and review South African preparedness efforts, drawing extensively from South Africa’s participation in, and findings and outcomes of the joint external evaluation of adherence to the International Health Regulations 2005. We identify health emergencies that took place from 2015–2020 and discuss in some depth two South African health emergencies that unfolded over this time. We reflect on health system responses to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic over 2020, illustrating how these drew on experience gained by stakeholders in earlier South African emergencies. Finally, we offer pointers to support strengthening South Africa’s emergency preparedness and response over the next five years.

Chapter 9: (Non-communicable Diseases.) The chapter provides an overview of the rise in the non-communicable disease (NCD) burden in South Africa, and the main drivers of this major epidemic. The chapter provides a detailed analysis of some of the main NCDs in the country – coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, cancer and asthma – with details of the trends in recent years and the key initiatives in the five-year period aimed at improving prevention, cure and rehabilitation. Conclusions include recommendations on the way forward.

Chapter 10: (Mental Health.) In this chapter we highlight the various successes in the mental health sector for the period 2015–2020, but also raise areas of concern that require urgent attention. The chapter embraces a dimensional approach to mental health, i.e. that mental health exists on a continuum from severe disability to well-being. The chapter covers five areas, starting with two recent crises in South African mental health, namely, the Life Esidimeni trag edy and the COVID-19 pandemic. The second section addresses service organisation. We highlight the importance of making optimal use of scarce resources and bring into focus the need for a comprehensive approach to service provision, including mental health promotion and prevention.

Chapter 11: (Occupational Health.) The chapter provides an outline of progress in the world of work in South Africa and the governance, legislation and policy on occupational health and safety, including the health systems response. The chapter covers the demography of work and a summary of the epidemiology of occupational injuries and disease, and the progress with occupational health services, including relevant human resources and professional societies. The remaining challenges facing South Africa are described with recommendations for the future.

Chapter 12: (Infrastructure.) The chapter provides an overview of the health infrastructure needs of the country, taking into consideration the health needs, and what is available through the public and private sectors. The chapter then reviews progress with various national initiatives aimed at responding to current challenges including the Ideal Clinic Realisation and Maintenance, the Office of Health Standards Compliance, Infrastructure Unit Support Systems, Draft 10-Year Health Infrastructure Plan, the Accelerated Health Infrastructure Roll-Out Programme, Framework for Infrastructure Delivery and Procurement Management, Draft Maintenance Strategy and the National Infrastructure Asset Maintenance Management. We review the achievements and remaining challenges for each, before looking at non-infrastructure-related challenges such as from the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

Chapter 13: (Quality.) This chapter reviews developments in the quality of health care in South Africa since 2015. We highlight important policy developments, and several initiatives in the public and private sectors to improve the quality of care. We also describe the key findings and recommendations of the 2019 South African Lancet National Commission report, ‘Confronting the right to ethical and accountable quality health care in South Africa’, and discuss barriers and opportunities for achieving a high-quality health system in South Africa post COVID-19.

Chapter 14: (Legislative Framework and Right to Health.) The chapter provides a summary on the relationship between law and the right to health, explaining why law matters and a human rights approach to health. It then covers the legal framework and how it has changed between 2015 and 2020, covering legislation, policy and regulations, intellectual property policy, notifiable conditions regulations, emergency medical services regulations, control of sugar, tobacco and alcohol products, and legal advocacy and legal processes. A review is provided of the Life Esidimeni crisis, when law and policy is implemented badly, and the Health Market Inquiry. A review of the key litigation includes emergency medical treatment, physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, and medical negligence claims. A case study covers ‘What COVID-19 teaches us about the NHI’ and the chapter ends with conclusions on the way forward.

Chapter 15: (Governance, Management and Leadership.) Following a brief overview of the governance, leadership and management successes and challenges in the past, we clarify the governance and leadership concepts that underpin the chapter and describe the key governance interfaces and relationships within the South African health system. We then examine the experience of frontline (district-level) governance and subsequently focus on provincial and national levels – considering how they support or constrain frontline governance in the multi-level public health system. We then summarise the critical issues of leadership and management highlighted in earlier sections and close by drawing out key conclusions for the future about the action needed to strengthen governance, leadership and management.

Chapter 16: (Information, Indicators and Systems.) This chapter describes and evaluates advances in the availability of accurate and timely local health information in South Africa between 2015 and 2020 against the backdrop of calls for more community participation, improved health system responsiveness to communi ty needs and priorities, and enhanced provider accountability. The chapter deals with both the public and the private health sectors, although most routine data sources predominantly cover public sector provision of health care services.

Chapter 17: (Human Resources.) The chapter reviews the previous national Human Resources for Health (HRH) strategy, launched in 2011, and reviews progress with implementation, and the likely implications for HRH of future reforms, in particular the NHI Bill. The chapter then reviews the problems related to inadequate HRH data for planning and monitoring progress, with comparisons to other countries. The implications for formalisation of community health workers are considered, as well as progress in strengthening leadership across the health system. A summary of the recently completed HRH strategy is provided and some of the main challenges outlined, including dealing with the implications of the COVID-19 crisis.

Chapter 18: (Health Financing.) This chapter examines trends, problems, challenges and progress in a selection of public and private financing domains. In general, despite some progress on the policy front, inadequate progress was made on the sector’s key reform, namely NHI, and the chapter attempts to explore why this is the case. In addition, the policy focus on NHI detracted focus from several other areas including medical scheme reform, which despite the Health Market Inquiry, made limited progress. At the end of the period, a large health security crisis emerged in the form of COVID-19, which had major implications for sectoral funding. Budget allocations were initially positive to counter the pandemic in 2020/21, but then increasingly negative from 2021/22 as the effect of prolonged lockdowns on the economy worked its way through to public sector revenue and spending. Final conclusions include that the proposed NHI model in the NHI Bill may require some re-evaluation of aspects of the model to get the NHI reforms back on track.

Chapter 19: (Global and Regional Health.) The chapter provides an overview of the global and regional health architecture and the main actors and institutions that are linked to South Africa. An update is given on the main initiatives that have been undertaken of importance for South Africa, and their relative success. The chapter then reviews the role of international actors and donors in South Africa, and the role of South Africa in supporting other countries in the region. The current challenges, including cooperation during the COVID-19 crisis are reviewed with lessons and conclusions drawn out for the future.

Chapter 20: (The way forward.) The editors led the preparation of this final chapter, which takes the conclusions and recommendations made by the different teams in preparing the chapters and puts them into this final section. This chapter therefore identifies a series of operational and strategic opportunities for the country policy-makers, managers, academics, private sector and civil society to champion over the next few years.

Tracking key demographic and health status trends over time provides insights into progress made towards reducing longstanding unfair health differences. Health is commonly defined as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’,1 and in economic terms it refers to the ability of people to thrive. What determines the realisation of good health however is multifactorial and complex. Importantly, the attainment of good health outcomes cannot be achieved exclusively through the efforts of the health sector. One’s genetic predisposition, along with a range of political, social, economic and environmental factors all influence health and well-being. This includes factors such as the geographic and political contexts within which one lives.

This chapter updates the one from the previous publication, covering the 2009–2014 period. It provides an overview of the main demographic and health trends in the country. It also highlights areas in which progress has been made as well as the challenges that remain, and concludes with a focus on how the country can improve the monitoring of the health status of South Africans in terms of equity.

South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world. The inequality in South Africa is rooted in the apartheid era. South Africa has a Gini coefficient of 63.0.2 Key drivers of inequality in South Africa are income, race, gender, geographic location and household composition.3,4 Labour and investment income are the greatest drivers of inequality. In recent years however, social grants have been shown to decrease inequality, as have remittances.3, 5

Rene English, Annibale Cois, Gaurang Tanna, Candy Day, Thuli ZondiExamining health trends through an equity lens requires the application of a moral dimension or judgement when analysing the differences in health across population strata (health inequalities). The judgement considers how much these differences are (1) avoidable (i.e. not the result of biology and genetics but rather consequences of how the society distributes resources and opportunities), and (2) unfair and unjust where factors such as wealth, power or social standing and not need drives unequal distribution of resources.6, 7

In South Africa, various studies have directly or indirectly measured health equity, and produced indicators of health inequality.4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The studies have largely adopted cross-sectional methods to measure health status.13 The analysis of health inequality has also been based on comparisons of health outcomes across population strata defined in geographical, socio-economic or demographic terms accompanied by a composite index.9, 12, 14, 15 While explicit recall of the moral judgement that underlies the definition of health inequity is not absent in the cited literature, in most cases the unfair and unjust nature of socio-economic disparities (after adjustment for biological determinants such as gender and age) is implicit in the approach.

The equity analyses carried out in the South African population have been mostly based on self-reported data from population surveys 9, 10, 12, 15, 13, 14 and sometimes on local epidemiological surveillance sites, and reflects the general weakness of routinely collected aggregate health data and health information systems in providing indicators disaggregated by population strata. This is a problem common in countries with limited resources and often hinders the possibility of measuring inequalities and inequities by using the most suitable indicators from a theoretical point of view requiring the choice of alternative measures as proxies. A case in point is the difficulty in monitoring geographical inequalities in the progress towards universal health coverage in South Africa.16 The District Health Barometer has however made use of socio-economic status by geographic areas as a crude measure of inequity that can be used with aggregate routine data.17

Knowledge of the limitations of existing data collection systems and the implications thereof are however important to highlight here as these are to be considered when reviewing and discussing the health data presented in this chapter where possible. In the following sections, we will accompany our description of the demographic and health trends between 2015 and 2020 with equity considerations. We will do this by presenting and commenting on selected geographic, demographic and socio-economic patterns observed in the data and on how these patterns differ from those that we would expect from an equity perspective.

South Africa’s population was just under 60 million during 2020.18 Over the period under review (2015–2020), the population increased by 8.5%.18 In 2020, females (51.1%) outnumbered males, and 80.8% were classified as African, followed by Coloured (8.8%), White (7.8%) and Indian/Asian (2.6%). In general, urbanisation is increasing.18 More than half the population live in three prov inces, and two-thirds (66.7%) live in urban areas.19 Gauteng, the economic hub, remains the most populous province (at over 15 million people) despite be ing the smallest in size, followed by KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) (19.3% of the total population) and the Western Cape (WC) at 11.7%.18 The remaining primarily rural provinces have much smaller population sizes, with the Northern Cape (NC) estimated to comprise 2.2% of the population.

Internal migration patterns reveal population movements from rural to more urbanised provinces between 2015 and 2020. Internal migration was positive for Gauteng (13.4%), WC (9.9%) and NW (8.9%), but almost negligible for MP and NC and negative for the remaining provinces.18 A positive influx of migrants from outside of South Africa was observed for all provinces between 2016 and 2021. Gauteng province and the WC received the greatest influx of migrants (internal and external), while the EC, LP and KZN had a negative total for migration. The population shifts have implications for resource allocation and health care provision, access and usage and have impacts beyond health to other sectors.

Births are the main driver of population growth in South Africa. The total fertility rate peaked in 2008 at 2.66 and is progressively declining, dropping to 2.33 in 2020.18 Fertility varies across provinces. In 2020, fertility was highest in the rural provinces, namely LP (2.90) and MP (2.85) and lowest in the urban provinces of WC (2.01) and GP (1.90).18

Trends also show that South Africa’s population is growing older as the fertility rate declines overall.18 The rate of annual growth among the elderly (60 years and older) rose from 1.09% in 2002/2003 to 2.99% in 2015/2016 and remained relatively static at 2.97% in 2019/2020. In 2020, 28.6% of the population were aged 0–14 years, with most residing in KZN (21.8%) and GP (21.4%), with the 25–54-years age bracket comprising the largest population proportion (42.5%).18 The median age is also increasing from 23 years in 2002 to 27 years in 2020 (Figure 2.1). The youth (15–34 years) have increased by 4.2 million between 2002 and 2020. The economically active age group (15–64 years) represents 63.5% of the total population.18 Child and old age dependency ratios show a decrease since 2002. In 2020 Statistics South Africa reported that the population under 15 was lowest in WC (27%) and highest in rural provinces, with LP being the highest at 39%. This suggests a greater economic burden on the working-age population in these provinces. Importantly, population profiles also differ according to population group, with higher dependency ratios amongst Africans and Coloureds (Figure 2.2).18

South Africa has observed declines in overall mortality, and mortality among infants, children and women. However, these gains have all reversed over the last year due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The overall health status of the South African population has improved since 2007 and this trend continued between 2015 and 2020. Life expectancy (LE) has increased and was at an all-time high in South Africa during 2020.

The LE at birth increased between 2015 and 2020, from 60.2 to 62.5 years for males and from 64.3 to 68.5 years for females.18 The increase in LE over the past decade has largely been driven by decreasing child and young adult mortality rates attributable to the scale-up of various health programmes, including the South African antiretroviral treatment programme.20 21

Since early 2020, South Africa was however ravaged by SARS-CoV-2 infections which reversed the LE gains (See chapter on Emergencies and COVID-19). Mid-year estimates for 2021 released by Statistics South Africa estimate the impact of the pandemic on mortality since early 2020.22 The LE for males declined from 62.4 in 2020 to 59.3 in 2021, and for females the decline was from 68.4 to 64.6 years (see Figure 2.3). These declines in LE and increases in mortality reflect the ‘cumulative burden of the crisis’ when compared to recent trends. Excess deaths are defined as the total number of all-cause deaths observed during a crisis that occurs in excess of levels observed under normal conditions, and provides information on the impact of the pandemic in terms of deaths reported due to confirmed COVID-19 infections.22 23 Higher mortality was observed amongst older people and groups with comorbidities, as reflected in the age-mortality profiles.

In South Africa, causes of deaths are recorded on death notification forms completed by medical practitioners and other role players within the health system. These deaths are further categorised as natural or unnatural. Profiles of deaths in South Africa confirm that the country is faced with a quadruple burden of disease and is currently experiencing an epidemiological transition. The trends suggest an ongoing shift towards non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as the predominant cause of death, whereas communicable diseases drive infant and child mortality. Most of these causes are avoidable and have their root causes within an array of social and economic determinants of health.

A steady rise in NCDs as a cause of death has been observed since the late 2000s.24 As of 2018, just under 60% of total deaths were attributable to NCDs compared to 55.5% in 2015. Just over 10% of the population died due to injuries (e.g. homicide, accidents and suicide). A marginal upward trend is observed for the past two years. Non-communicable diseases are the primary broad cause of death amongst adult males aged 30–50 years and women aged 25–39 years, whereas the percentage of deaths due to injuries is high amongst males in the 5–9 years and 15–19 years groups, and peaks at about 65% for those aged 20–24 years.

Tuberculosis (TB) still ranks as the leading natural cause of death in 2018, followed by diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease and other forms of heart diseases. HIV ranked fifth overall. Amongst males, TB, HIV and other forms of heart disease, DM and influenza and pneumonia are the primary underlying causes of death. For females, the primary causes are DM, cardiovascular heart disease, hypertensive disease and other forms of heart disease and HIV. For males, trends in underlying causes of death (per cause) have remained static for all causes except for TB, other forms of heart disease, influenza and pneumonia, where increases were noted. For women, increasing trends were noted for TB, other forms of heart disease, and influenza and pneumonia.

The 10 leading underlying natural causes of death for broad age groups (2018) reveal important information for policy-makers (Table 2.1). When exploring the underlying immediate, or contributing causes of death in 2018, TB, DM, cardiovascular disease, other forms of heart disease, HIV, hypertensive disorders, influenza and pneumonia, chronic lower respiratory disease and malignant neoplasms of digestive disorders were ranked amongst the top 10 (descending order). Non-natural causes of death in 2018 (n=54 163) were primarily due to external causes of accidental injury (68.3%), followed by assault (14.5%) and transport accidents (11.4%). The number of unnatural deaths among the 15–59-year-olds showed a constant increase over time, which is of great concern.23

Ages 1–14

Influenza and pneumonia

Intestinal infectious disease TB

Other forms of heart disease

Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes Ages 15–44 TB HIV

Other viral diseases

Other forms of heart disease

Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes Ages 45–64 years TB DM HIV

Cardiovascular Disease

Other forms of heart disease Ages 65+ DM

Cardiovascular Disease

Hypertensive Disease

Other forms of heart disease Ischaemic Heart Disease

Indicators measuring child mortality are good indicators of a population’s health,25 and neonatal mortality is said to reflect the strength of a country’s health system.26 High death rates amongst children reflect policy failures at multiple levels and have broader societal and public health impacts. Overall, infant mortality rates (IMRs) and under-five mortality rates (U5MRs) in South Africa continue to decline. In South Africa, most women access public sector health facilities during the antenatal period and when giving birth. The indicators presented here reflect mortality rates as measured within public sector health facilities.

The early neonatal death in-facility rate, namely infants of 0–7 days who died during their stay, has decreased between 2017/18 and 2019/20 from 10.2 to 9.6 per 1 000 live births, respectively. Similar reductions are reflected for overall in-facility neonatal mortality (infants 0–28 days who died during their stay in-facility per 1 000 live births) and stillbirth rates. Disaggregation by province however reveals inter-provincial differences with poorer outcomes observed in the more rural provinces. The early neonatal death in-facility rate was highest in the NC (13.1 per 1 000 live births) and lowest in the WC (6.5), with increasing rates observed within three predominantly rural provinces (LP, NC and NW). Stillbirth rates were highest in the NC (24) and lowest in the WC (16.5). Neonatal death rates are highest in the FS (15.6) and NC (15.5), and lowest in the WC (8.2). Increasing trends are noted in the FS, LP, NC and NW provinces.

Infant mortality rates (deaths under one-year per 1 000 live births) and U5MRs have significantly improved over the five-year period. The IMR was estimated to be at 28 per 1 000 live births in 2015, compared to 21 in 2020 (according to the Rapid Mortality Surveillance report 2019/2020) and 23.6 in 2020 (according to Statistics South Africa). The U5MR was 39 per 1 000 live births in 2015, compared to 28 per 1 000 live births in 2020 (according to the Rapid Mortality Surveillance report 2019/20 ) and 34.1 in 2020 (according to Statistics South Africa).28

Low birth weight is defined as weight at birth less than 2 500g. The proportions were calculated from the sum of live births under 2 500g divided by the total sum of live births in a facility. Nationally, there was a decrease in the percentage of children with low birth weight between the years 2014 and 2015 (13.1% to 12.9%). Thereafter, there was a steady increase from 12.9% in 2015 to 13.5% in 2017, then a decrease to 12.9% in 2018 reverting back to 2015 levels. The figure below reflects the provincial trends. Northern Cape has consistently recorded the highest percentages of children with low birth weight for all the years. Provinces that have experienced an increase in the proportions of live births under 2 500g over the 2014–2019 period are EC (13.6% to 14.0%) and FS (13.6% to 13.9%).

Malnutrition is a leading cause of death amongst children in South Africa and has significant longstanding effects on those who survive and generations to come. Nationally, proportions of children under five years with Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) decreased slightly from 3.6% in 2016 to 2.1% in 2017, and then increased slightly from 2.1% in 2017 to 2.2% in 2018. In 2018, NC, FS and NW had the highest proportion of SAM incidences of 6%, 5% and 4.6%, respectively, while EC, GP and MP had the lowest proportions at 0.7%, 1.6% and 1.7%, respectively. In 2019, the General Household Survey reported that severe food inadequacy was highest in the NC (12.2%) and the NW (11.4%) provinces – higher than the national value of 6.3%.29 It is very likely that the levels of SAM will have been massively worsened by the COVID-19 crisis.