© 2024, Plainsong, Vol. 37

Department of English & TheatreArts, University of Jamestown, Jamestown, North Dakota; copyright reverts to authors, artists, and photographers on publication, and any reprinting or reproduction may be exercised only with their permission.

Plainsong, a non-profit journal funded by the University of Jamestown, published by the University Department of English & Theatre Arts, includes work of students, faculty, staff, alumni of the University of Jamestown, and creators from around the country.

EDITORIALBOARD

Department of English

Sean Flory, Ph.D., Chair

Mark Brown, Ph.D.

Danielle Clapham, Ph.D.

Aaron Cloyd, Ph.D., Editor

STUDENT EDITORS

Rachel Roehrich

Kirsten Vander Kooi

LAYOUT

Rachel Roehrich

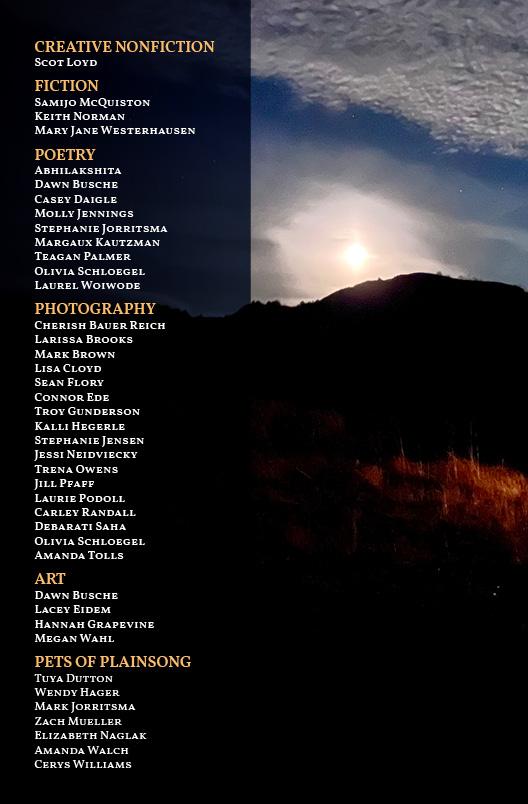

COVER PHOTOGRAPH

“Tabernacle”

Mark Brown

COVER DESIGN

Donna Schmitz

PRINTING & BINDING

Range Printing, Brainerd, MN

For almost forty years, Plainsong has represented the creative and artistic voices of students, faculty, staff, and alumni of the University of Jamestown. Starting with last year’s issue, the magazine also became a place where artists and authors throughout the Northern Great Plains region could publish their various creative works.

Positioned as such, Plainsong hopes to further the long-established commitment to the arts on campus as well as UJ’s relationship to communities beyond campus.

This year, this broadened vision of the magazine led to the publication of several UJ-affiliated authors and artists alongside an interview with the newly-appointed North Dakota Poet Laureate, Dr. Denise Lajimodiere. Dr. Lajimodiere succeeded Larry Woiwode and became the state’s first Native American to hold the position. We were honored to interview Dr. Lajimodiere and hear more about her poetry and advocacy for Native American rights.

This past winter provided an additional point of connection between campus and community. Throughout the magazine, you’ll find various pictures from an ice storm that moved through the region at the end of December, 2023. While the storm caused extensive power outages and treacherous travel conditions, the ice also created remarkable sunsets and a radically-changed landscape, and our hope in publishing these images is to document and remember these events.

Within the past year, these relationships also stretched around the globe to Chandigarh, India and Chandigarh University. In August 2023, the University of Jamestown and Chandigarh University created a partnership that will allow both institutions to expand their international vision for education. As a result of this relationship, CU students will be able to complete their final two years of education at UJ and graduate with a degree from both institutions. While the first exchange of students won’t occur until fall semester, 2024, Plainsong is pleased to provide a space for this international vision, and, in this issue, we’re delighted to publish the poetry of Abhilakshita and the photography of Debarati Saha.

This magazine, and these relationships, are only possible through the support of the University of Jamestown, and, in particular, with the assistance of the English department and university administration. Thank you.

As with last year’s issue, Plainsong once again reflects the attentive insight and careful organization of Rachel Roehrich, and this year, we are thankful to also have the support of Kirsten Vander Kooi. This publication would be greatly diminished without their efforts.

Finally, thank you to everyone who shared their creative adventures with us. We are honored to be a part of your endeavors and hope to hear from you again next year.

Lajimodiere

Lajimodiere

Author Interview with ND Poet Laureate, Dr. Lajimodiere

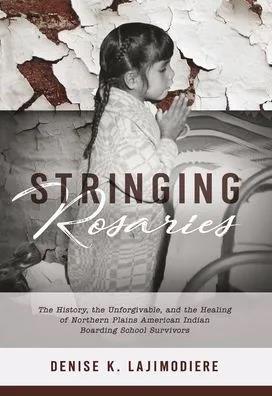

In April of 2023, Dr. Denise Lajimodiere became the first Ojibwe woman to be named North Dakota Poet Laureate. She is an enrolled Citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Belcourt, North Dakota. Earning a Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctorate degrees from the University of North Dakota, she was involved in education as an elementary teacher, principal, and professor for forty-four years. She has published four books of poetry: Thunderbird, Dragonfly Dance, Bitter Tears, and His Feathers Were Chains. She has also published a children’s book entitled “Josie Dances.” As a nationally recognized expert on American Indian boarding schools, she has written about the atrocities experienced by survivors in Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgiveable, and

the Healing of North American Indian Boarding School Survivors.

In September of 2023, Plainsong staff sat down with Dr. Lajimodiere to ask about her work with boarding schools, her writing experiences, her plans as Poet Laureate, and her traditions that she is passing down to her grandchildren.

Plainsong

Dr. Lajimodiere, thank you for taking time to talk with us today. It’s good to meet you.

Lajimodiere

It’s good to meet you, too.

Plainsong

In your 2019 award-winning book, Stringing Rosaries, you write about the atrocities of boarding schools. Can you say more about that?

Lajimodiere

I was one of the founders of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalitions, and I’ve been with them since 2011, trying to get information to Congress about the boarding school era.

But it took sort of a perfect storm of events.

With the boarding schools, there’s been an explosion of information because the media is paying attention.

Kamloops [British Columbia] happened in June two years ago, about the unmarked graves at the residential school there, which became international news. Deb

Halland had just gotten in her position [as Secretary of the interior]. The Boarding School Healing Coalition was in their position, and then my book Stringing Rosaries. And now Elizabeth Warren and Secretary Halland have introduced the Truth and Healing Act in Congress to investigate the boarding school era.

Plainsong

How did you go about finding your voice?

If you want to write a poem, read a hundred other people’s poems

Lajimodiere

In 1969, when I was in creative writing classes at my high school, there were no Native poets. So I actually sort of tried to quit writing, but when you’re a writer you can’t really quit writing. So I kept taking classes, but I didn’t really know what I was doing. It’s only in the past twenty years or so that we started

seeing Native poets. I picked up Louise Erdrich’s book Love Medicine. She was Native, she was female, and she was from my tribe. That just blew my mind. So that’s when I started writing. So we are writing our story. We’re telling our story from a Native point of view.

In about 2005, I was at the University of North Dakota and working on my dissertation, and I thought, “This is driving me nuts. I’m going to sneak over to the English Department and see if they won’t let me into their classes.” Larry Woiwode let me in. He told me we would know sestinas and villanelles, and I was a hippie back in the 1970s, and they said we’re just going to do free verse. I said I’ll just write free verse, and he said the most remarkable thing that never left me. He said, “Well, in order to break the rules, you have to know the rules.” So I took his classes and started writing sestinas, villanelles, and sonnets, and I found that some things that I wanted to say only would fit into a form poem.

Plainsong

We know people on campus and in our community are writers, but they’re kind of closeted writers. They don’t want to share their work. What advice would you offer to new writers?

Lajimodiere

If you want to write a poem, read a hundred other people’s poems. So it’s just read, read, read.

Writing takes skill. But it also takes writing, writing, writing, and revising, revising, revising.

How do you start writing? Butt in chair.

Plainsong

What are your goals during your two-year stint as poet laureate?

Lajimodiere

I work with the North Dakota Council of the Arts, and I do four presentations throughout the year, but I also want to apply for a grant in January. In high school, I didn’t have mentors, so I want to take that money and go to all the reservations and work for a week, two weeks, or whatever with students to develop poems. But because residential schools took away our languages, we don’t know our

tribal languages, so I’d like to hire interpreters for each of the tribes to interpret the students’ poems into their tribal language and then publish them in an anthology. Otherwise, it’s just spreading the joy of writing and reading poetry throughout North Dakota.

Plainsong

One of your poems “Tawkwaymenahnah” is about the tradition of picking chokecherries. What other traditions do you pass down to your grandchildren?

Lajimodiere

I have my grandma’s rocks [for grinding chokecherries] and I need to find that base rock because I have a granddaughter staying with me right now and I’m considered an elder and I want to teach her the traditions of our ceremonies. I’m taking her to our ceremonies and handing down our stories. At the

powwows, my granddaughter likes the frybread and the frybread tacos. And I have a lot of wild rice that my friends in Minnesota and Wisconsin and Michigan send me. They’re also maple sugaring, so I have a friend that gave me a gallon of maple sugar, which I’ll spread out with all my relatives and cousins and friends here on the reservation. So I keep some of these traditions alive.

Otherwise, it’s just spreading the joy of writing and reading poetry throughout North Dakota.

Plainsong

Thank you, again, for meeting with us. It was lovely to spend time with you.

Lajimodiere

Alright, thank you all. Have a good day.

Author Interview – Dr. Lajimodiere

Lajimodiere’s Selected Works

Fields of Stone

Kaleb North liked the sound of the tripping shutter on his camera. He knew the digital camera's electronics generated the sound, not the shutter creating an opening across the front of the film. The programmed noise occurred when the software took in the image data from the sensor and still sounded like it was taking a picture.

North peered through the viewfinder, placed the rock in front of him in the lower right third of the frame, and pushed the shutter. He moved the camera enough to move the rock to the other side of the frame and heard the sound of the shutter again.

It was a very basic picture with the texture of stone, grass and a sapling tree, creating a contrast he liked.

“Kaleb, did you see this?”

He stepped over to where Kate Sayler stood, letting the camera rest on the strap around his neck.

The couple stood on a small hill and looked down the slope. Stretching below their feet a tossed rubble of rocks formed a rough rectangle. The center was open, with the green grasses of spring poking through the dry mat of old vegetation.

Close to one end, a cluster of ox-eyed daisies showed buds but no color.

The rocks below them gave the impression of collapse as if a low wall had been reduced to piles of stones. None were larger than 8- or 10inches across although all looked similar to the bigger rocks that still scattered across the hilltop.

“What was this?” Kate asked. “It had to be something?”

Caleb started snapping pictures of the stones. He thought best when he looked through the viewfinder.

“I don’t know,” he finally said. “Too small to be a barn. If it were a house or shed, there would have to be an opening for a door. There would be a gap in the stone piles.”

Kate stepped downhill to the nearest corner of the enclosure and looked at the stones. She saw that years of blowing dust had accumulated between the lower levels of rock in the rubble. The spring grasses, weeds, and wildflowers sprouted through the soil and rocks.

“Somebody worked hard at this,” she said. Kaleb nodded. There looked to be about 50 stones for every yard of the walls. The little enclosure was about 10 by 15 feet with a uniform pile of rocks all the way around.

He snapped a picture of the rusted metal of an old shovel mixed with the fallen rocks near the north end.

“Don’t know what it was, but it does make for some nice pictures,” Kaleb settled down, finding plants to snap with the rocks as the backdrop.

Kate just nodded and pulled her sketch pad out of her bag. She eyed the daisy buds that just hinted at color and beauty. Both lost in their thoughts, they explored the rock ruin. It was what they did. Kate and Kaleb tried to get together every couple of weeks, with the time together mostly dedicated to photography and art.

Kate looked up from her sketch pad and over at Kaleb. She was always amazed that the two people who found the beauty of desolate and wild pieces of prairie attractive found each other.

Kaleb glanced over the top of his camera at Kate. She was beautiful when she was wrapped up in the scene before her. Hell, she was beautiful all the time, he thought.

They didn’t give the question of who built the stone wall or why any thought, Instead they enjoyed the day.

Toby Samson walked with care. He carried a bucket of eggs and orders to walk to the general store in Fried and have Mr. Carson apply the value of the eggs to the Samson account.

Then, if Carson would allow it, he was supposed to charge a tin of baking powder to the account and bring it home. It was a big transaction for the 10-year-old boy, but his father and older brothers were shocking the wheat field for harvest, and his mother was busy cooking for the crew.

Toby was the only member of the homestead family that could be spared.

Mama Samson wouldn’t have splurged on the new product but had heard it would be a simpler way to make pancakes than her old sourdough starter.

Little Toby didn’t care about the efficiencies of his morning pancakes. He just had to make sure he walked the 3 miles from the Samson homestead to the little railroad town of Fried without cracking even one egg.

He hardly raised his eyes from the ground immediately in front of him out of fear he’d trip his bare feet on a rock or root.

That was why he was just 20 feet away when he noticed Sally Crawford working intently on the ground of a small hill. Next to her stood a bony horse hitched to a stone boat.

Sally, Old Lady Crawford as Toby knew her, was using an iron pry bar to work a rock about the size of a medium watermelon onto the ground-level surface of the stone boat.

Toby carefully set the eggs down and watched Sally lead the horse a few feet and pry loose another rock, this one just a bit larger, and slide it onto the stone boat.

For a minute, Toby concentrated on the horse. The animal looked like it would fall over at any step. Still, it strode forward when Sally gave a gentle tug on the lead rope.

Toby counted only about a dozen rocks on the stone boat but the woman started the horse towards the tar paper shanty on the side of the next hill. The horse struggled dragging the flat-bottomed stone boat across the uneven ground. Twice, Sally let it stop and catch its breath.

Toby trailed along with his eyes wide in wonder. He was only 30 feet behind the woman and horse, but they never seemed to notice.

She stopped the horse so the stone boat was next to about 10 feet of a stonewall. She struggled to pick up a rock off the stone boat and set it on top of other rocks. Each rock fit on top of others building the wall higher with some stretches nearly waist-high on the woman.

Sally shook each rock she placed to make sure it was solid before turning back to the stone boat.

When she placed the last rock, she unhooked the horse, and Toby watched her lead it to a water tank next to a hand pump by the shanty. Then she drank from the same tank and led the horse back to the stone boat, and the pair went back down the hill looking for more rocks.

Toby picked up his eggs and headed north. It was still a mile to Fried and that baking powder his mother wanted.

An hour later, with the eggs delivered successfully and the can of baking powder tucked into his shirt, he walked past Old Lady Crawford’s place. She and the horse were struggling up a hill on their way to the wall.

She even grabbed the trace chains and pulled to help the horse reach the peak before they rested. The lady batted flies around the horse’s eyes while its head sagged to catch its breath.

Toby saw from the next hill the lady and horse working towards the wall where she’d added rocks earlier.

“It doesn’t look like she accomplished much,” Toby thought.

Sally saw Toby out of the corner of her eye but didn’t acknowledge his presence. She’d ignored him earlier when he’d traveled by with the eggs.

She didn’t usually ignore her neighbors or even their children. A chance for conversation came to seldom to waste when you lived on a homestead.

But now, she didn’t want to explain what she was doing.

Instead, she kept loading the rocks on the stone boat and building the wall.

A days work usually completed about a foot or two of the wall.

Three more days and it would be done, she thought. She glanced at the horse as that thought went through her mind.

“Maybe four or five days,” she said as she patted the beast on the neck and said a silent prayer the animal would survive that long.

The project was getting harder with every day. She’d used up all the rocks that were a size she could handle located close to the wall. The horse and drug the rock-loaded stone boat a quarter mile for each trip now.

Sally started the day in the dark with just a hint of a pink sunrise in the east when she harnessed the horse. They took a break for a couple of hours in the middle of the day and then got a couple more loads in the evening.

On the third day, the horse started favoring its off-front leg. She now pulled on the tugs all the time rather than just when going uphill.

On the fourth day, she brought the final load to the wall late in the morning. She pulled off the harness and turned the horse loose. The animal stood slumped next to the tar paper shanty.

Sally stood up straight after lifting the last rock into place.

To anyone casually looking, the wall enclosed a rectangle of prairie grass dried to amber by fall winds.

But Sally knew it held much more.

She set the shovel and pry bar on the interior side of the wall and then swung her legs across. She removed her sunbonnet as she stepped to the east end of the enclosure.

At her feet were three crosses the wind and roving livestock and wildlife had knocked down.

She set up the one on the farthest left and used the shovel to pound it a little deeper into the earth.

“Oh, Mary,” she said, addressing her daughter’s grave.

At the right-hand grave, she set up the cross of William and said a prayer for her only son.

The cross in the middle was the crudest of the three made by Sally’s hands after her husband died. She didn’t pound it into the soil for fear it would break.

Instead, she leaned it against the stone wall, Then stepped back and wept.

All three had been taken by the grippe that spring. First Mary, then William. Her husband had been coughing when he made William’s cross and died three days later.

She’d done the best she could but knew the grave was shallow and the cross crude.

Sally sat with her back against the stone wall through the afternoon. The prayers and the tears alternated for the family taken from her.

She went to the shanty at sunset and packed together a burlap bag of the things she owned. It amounted to a few clothes and some cooking utensils. She didn’t know what would be useful when she moved to Jamestown.

In July, her sister and her husband had come out to visit. She’d told Sally she could get a job at the Gladstone Hotel cleaning rooms or waiting tables.

Sally told her she had a couple of things to do before she moved to town.

She rose at dawn of her final morning at the shanty. The horse was nowhere to be seen, but she planned on turning it loose anyway. She hoped it would survive but doubted it would make it through the winter.

She walked a last time to the rock wall. And gazed in at the crosses. The rocks would protect them from wind and livestock that knocked them over previously.

Then she thought of one final thing. She grabbed the shovel that leaned against the shanty wall and strode up the hill behind the homestead.

There, not in bloom but still recognizable from their leaves, grew wild daisy. Her husband had treated the wildflowers on the hill as his personal garden and brought her blooms for the shanty at the end of every spring day.

Now she dug up three of the plants, digging deep to get as much root as possible, and carried them to the graves. She dug the daisies in as best she could and then left the shovel.

Sally crawled over the stone wall one last time and picked up her burlap bag. She’d done the best she could to protect everything she loved.

Robins’ Eggs

I hold my dreams like robins’ eggs careful, a child trying not to crush the magic as I shelter them from wind, protect them from rocks, and never bother asking what is growing inside.

I am too small to question miracles, so I await hatching.

Waiting for Momma

Threads

I love that beauty reminds you of me the spaces I live in, in your memory like held breath, in velvet and silken scraps, and delicate, fraying threads holding together garments, seams you never had the heart to rip out and fix the ones made for you to hold, gently...

You remember the way you held me when I was just a little pattern piece fragile, half-translucent in your hands. And you remember the little things, the first button I found on the ground, the excitement of new elastic.

You remember the things that were ours, the fabric dye we spent weeks choosing, forgotten too long while we watched the sky out the attic window. You remember the painful, growing things, my finger-pricks and frustration tears. The times your sure hands took over, and my stitches became more even as I copied you. You remember the uncertain things, hours and hours in front of bolts of fabric trying on lives like I had forever to choose… And you remember the things of history stories weaved between the threads we’d sew and memories you’d never be able to tell me about when you ran out of words, and we watched the sky instead. You remember wordless things, like this little dress, wrapped in tissue, with a note and a bow the one I gave you when I was young, even though I wanted to wear it.

With its mismatched pieces, and fraying thread, and the button I found at the park one day, it reminds you, and you hold it, gently…

I spend a lot of time sewing now, I guess I finally found the patience. I weave my threads across evenings and time, and I long to be there with you, back in my childhood home, by the attic window dropping stitches as we watch the sun set.

I’ve Known the Lilacs for so Long

Materials: gouache, acrylic paint, house paint, Posca markers, and colored pencils

The Hungry Heart

Storm Warning

It brewed slowly

While you ignored The impending signs.

When it breaks Exploding across You like the Wrath of a Fury

You will be dumb.

Winter Morning

Gray skies, below brown fields

Patched with snow, silent

Beneath a howling wind. Pellets

Of snow sting my face and cling to My eyelashes. Between the harsh Sky and bleak ground, a layer

Of pure air thrums, cleansed

By the snow. It carries my breath

Off in a cloud and, as I inhale, my Nose burns. The wind beats on My face, tempting me to fly.

I still, eyes closed, arms

Outstretched, leaning into the Wind, and feel weightless.

Breath streaming back across my Upturned face releases me heavenward.

Debride

The blue sky blooms wide over me, myself, and torn open deer hide as blood red stains me elbows high and the doe's fly-specked still eyes dully shine their dry message that her death mirrors mine.

Selfish or selfless, it's muddled to become self-less, in that the self is ground to red paste in the dappled light of copper scented days, and with each one I awake with a new face to find myself in the wood as a killer, a sinner, a badge of horror to shed my skin for more.

Perhaps I'd have no problem in the find, if I'd ever really tried, but the seeking seems to make my belly, yellow and wide, turn tail, runaway, getaway, hide, and now, armpit deep in deer insides, wearing her guts as garters, holding her heart up next to mine: I seek and I might find that which is gone from me, but in others seems to so easily reside.

Here, thumbs through foreign lungs, her dead flesh flinches, shows me shades of a smile. I offer limp bodied apologies and lame excuses for even in all the violence I have yet to find its uses and, as always, I'm left with nothing while she stands, wobbly like a fawn and runs just far enough to feel safe, even if it's never far enough, could never be far enough.

In her eyes, she knows, we are still hungry, still hunting, still alive, after all.

Frosty Buffalo

I'm Fine, and You?

This urge calls to me; long and loud, lovely and lonely. It sings to me out from underneath soft and painted lips and whistles up and over rows of sharp and pointed teeth. It tells me of impending doom, sure and swift defeat, and laughs rich and deep when my grip slips upon my beliefs.

"Tear a way away from this place, now, today, chew your foot off at the ankle, break through the bars on your cage: get up, get in your car, and drive. This time, what is new will be kind, you will thrive in lonely and it will be grateful for you to arrive."

It curls an arm around me when I'm cold, gives me cautious warnings when I consider being bold, gives me the power to read others' minds just to fill my friends' heads with thoughts they wouldn't think, paralyzes my speech and leaves fingerprints like bruises dipped in indelible ink on everything I do.

I wish I could just say the things I want, but the urge has me by my throat, so I use my hands. To help you move or to feel your head, I use them to put up your shower curtain or hang up a poster above your bed, I check the brakes and stay up late thinking up all kinds of things I should have said.

The urge to run away never seems to do so.

A Star in Another Sky

Our ship slips through space, flashing silver like fish flesh in the light of stars then swimming again from sight. How strange how far we’ve come yet I still tell time by a never seen sun, and when I speak of space, death becomes birth, I do it in that dying tongue, the language of Earth.

We are firstborn, between two worlds; our parents’ hopes and horrors, the Earth and another, the space between seconds, the vacuum between each other.

Our parents seek what they cannot find: they have showed us their cities and their skies, all the old open spaces, of another kind, and they have given us all their ghosts, gifted us a haunted, enchanted childhood, but, now, our children are young, or coming, and we must ask ourselves, will we raise them on legends, and sorrow that seeps into every smile?

To be without a history is to be sent scrambling without handholds forward into the future, is to be unmoored, untethered to others, but can a legacy be a cruelty? How can we stop missing that which we’ve never known? Our parents soaked in sorrow, they ran rivers at their mouths, but we cannot repair it

even as we see it in ourselves: we orbit mourning.

On a starship, tears are wastewater, so we close our eyes, hang our heads, and hold on. We will hold our parents as we hold our children, as we want to be held, and as we listen to the engines hum we will try to find something to build on. Spinning toward another world, we seek to heal from our history, together.

Rural America

Materials: acrylic paint on canvas

I Paint a Picture

To draw lines out of a face

With wildflowers in October breeze

My hands drip paint

Green for eyes consumed

So consumed, almost free; Golden, for mischief

When you know there is trouble you want it to be

And black, danger

Nearing something Feral.

Night covers me

Blue, like ivy

Deeper than an emotion not long awakened

And I, paint a picture Of heaven

With wildflowers

An effort to tame this moment

The fleeting grace

In full bloom.

A childlike triumph, If I must But then I must not won’t do justice

Won’t freeze time

And I’ll carry the curse a blessing for the naïve to see you wither, in time to see this beauty turn to nothing.

I Have Been Many People

I have been many people, Twenty and twelve at once

A mother to a mother

And a child, to a child.

I grew up, watching love turn people blind

Picking pieces up from the floor

Of a heart shaped frame.

I wiped people clean of tears, of blood and of shame.

I was young one day, maybe once

When I laughed till my stomach hurt.

Older since, I haven’t ached so much in months

I keep washing myself but it stays like a stain

I am born every day, every day feels like a year, in vain

It was yesterday, only yesterday

When I first felt fear.

Now I lull myself to sleep

Dreaming of a childhood that was Never mine to bear

Growing old, it clings to my bones

The loss of innocence haunts me like an old home.

A home that keeps falling apart Only to rebuild every morning

And I am afraid, of wasting a life

Under a roof of mourning.

Blossoming

Materials: embroidery floss stitched into an old photograph

Between Christmas Day and a New Year

Reflective; an “awkward pause,” in which we are met with lingering effects of the likely emotional mix from family dinners - whether given, chosen, or found.

I wonder if others, like me, take down the paper fridge calendar early as if to say, these days are left unwritten.

While we may go through the motions, there’s a certain lack of rhythm.

It’s unsettling maybe It’s freedom too

A liminal space in which loose threads hang on house plants, bows scattered to be saved hopefully not thrown away.

Two sleepy dogs stare at the front door, the sound of ice turned slush drops on the roof and each time they rise alert. They pause and sit and focus.

We walk back to the couch and rest again.

The Thunder’s Roll

In the season of the rain, I come.

I can sing among the showers, to rejoice in the meadows of flowers. I utter my song; my heart knows joy. I am not faint before the thunder’s roll. I can withstand the lightning strike, to receive the wisdom in its might. I cry and cry not out within its pain.

I stand on the wave of the storm.

I praise its strength and homing. Stand up, the dawn is coming, And I hear my own soft laughter.

Running Into the Sunset

Winter’s Eyes

In My Father’s House

Ambivalence embraces me as I fumble around the attic of a strange house that is now mine. I engage a necessary task. I feel nothing. A thin, black Moleskine is cold in my hand; it’s worn cover cracked from years that are lost to me. Left in the corner of my father’s attic, under a stack of The Sunday Times, it valiantly endured the seasons for perhaps a decade or more. The words “First Guaranty Bank: Carthage, Tennessee” fading from its cover, it is shrouded among cobwebs and dust bunnies, biding its time until this moment of revelation. Perhaps a forgotten piece of marketing tchotchke taking up residence with the other misfits in this attic? Misfits, like me.

My father has only been dead a week and just one day in the ground. I’m the sole survivor of the Bostwick estate, such as it is. My name is Richard; I go by Dick, as I have never been one for formalities. My mother Virginia proceeded my father in death: lung cancer, as she picked up smoking when it was fashionable, a habit she shared with me. I am their only child, as their passion cooled not long after I was born. They stayed together for tax purposes or stubborn pride; I suppose. It’s hard to tell. Maybe both? My father lived on for another decade, wedded to his predictable routines, including golf on most Saturdays and the newspaper crossword on Sundays. His weekdays were passed by watching cable news, drinking an occasional cheap beer and little to no emotion, at least not of the productive varieties, habits he shared with me.

His long career as a mail carrier provided some middleclass luxury in our lives, with some security in retirement, but mostly it was all aspirational a charade to impress others who were never really paying attention. My father died alone. Just as I imagine I will. The Moleskine’s pages are empty, except for a drawing near the back where someone had crudely sketched out the floor plan of my parent’s home. By most standards the house was nice, a late design of the last century with the ever-present hint of upper middle-class ambition. They purchased the house shortly after I left home. I was seventeen. The incessant fighting finally got to me: theirs, mine, all the above.

I never spoke to my father or mother again, as it seemed pointless. They didn’t intend to change neither did I. Father did send me a scribbled message when mother died, “Richard, your mother is dead.” It was

signed, “James.” Not “Jim” or “Daddy,” just the formal, emotionless way my father would always speak. Distance was par for the course in my family. After I left, I wandered around from place to place, one dead end job after another, failed marriages, and complicated relationships, including with my own kids. Then one day, out of the blue, I get this call. I share my father’s last name, now I own his house. But for all practical purposes, I’m a stranger, a stranger who now owns a strange house. The key was given to me by a town attorney. Apparently, he and my father had been golfing buddies. “This is all he left; there are some taxes you’ll have to pay.” I suspect the attorney was expecting more from me, but I had nothing to give. I nodded and said, “Thank you.” I took the key from him and drove to the address, opened the door, and immediately walked up the narrow staircase to the second floor.

I was purposefully looking for the attic, in hopes that something useful of my childhood may have survived. In our former home, I would often hide in the attic to escape my parent’s fighting. I accessed the attic via the scuttle hole by pulling the string and unfolding the ladder. I climbed up into the attic that was filled miscellaneous boxes, broken furniture, and scattered remnants of my childhood. That’s when the collection of newspapers caught my eye. One of the few happy memories my father and I shared was a Sunday tradition that involved those newspapers. He would hide behind the news of the week, and dutifully fill out his crossword puzzle, but the Sunday funnies were always mine to read. On occasion, time was well wasted pressing silly putty onto the contoured lines and comical expressions of Garfield, Snoopy, or Beetle Bailey, and then peeling it off to reveal a perfect imprint.

That memory lived now under that stack of perfectly preserved newspapers; it was also where the black Moleskine caught my attention. I would have laid it aside, had I not come across the mysterious sketch of the floor plan. It intrigued me, as each room had a randomly assigned number. There was a number one written in the attic, a number two in the upstairs bathroom, three in the master bedroom, four in the kitchen, and ended with five in the living room. Perhaps a discarded remodel plan? Exiting the attic, I stepped into the upstairs bathroom. I stood at the sink picking up the bar of Irish Spring soap to wash my hands. That scent always made me think of my father, even if I was reluctant to do so. As I lathered the bar in my hands, I was suddenly five years old again,

standing on my toes to reach the sink. “Anything that is worth doing is worth doing well!” he would say as he took my hands and put them together with the soap and washed my hands between his. I recalled my father’s touch, remembering the strength and gentleness of his hands, and for the first time I felt my father’s familiar presence lingering in this strange house.

I stepped out of the bathroom and turned into the master bedroom. On the nightstand was the only family picture from my childhood. I was ten; mom had purchased a ticket from a local church group for an Olan Mills portrait. I wore an orange sweater that made my neck itch, my father was in his blue suit with a wide red necktie, and mom wore her lavender dress with yellow sunflowers. The picture was as awkward as the events that led to it. Mother had announced at dinner that we had to get dressed to go to the church for the ten-dollar package she had purchased. The First Baptist Church of Carthage. We only attended as a family on special occasions, and now apparently to have our picture taken. We were sitting in front of the television eating meatloaf, watching Peter Jennings, when mom made this surprise announcement. “What the hell, woman?” my father exclaimed. Strangely, I don’t remember that it was a huge fight, certainly not like those that came before it, and not like those that would follow. It was as if he acquiesced to mother’s desire in a strange dispensation of peace that was preceded by only one profanity. Strange the things I remember, and what I choose to forget.

I was the only one smiling in the picture, I put the picture down and walked out of the room. I headed back downstairs to the kitchen. The appliances were dated but seemed to be in working condition. I opened the refrigerator. A carton of eggs, a few Michelob beers, various condiments and sauces and some left-over pizza populated the otherwise empty shelves. Seeing the beers prompted me to remember my first one. I was twelve, and my parents had screamed at each other for hours. When the fighting subsided, I came downstairs. I opened the refrigerator, grabbed one of the many Michelob beers and popped the top. It was bitter and heavy, a drink unlike any other I had tasted, I forced myself to finish it out of curiosity if nothing else. The ensuing buzz was more imagined than real, but I strangely felt older, even though I was still several months shy of a whisker. Afterwards, I returned to my bedroom

determined that my first beer wouldn’t be my last. The next morning, I was awakened by my father’s booming voice; “The next time you decide to steal one of beers, you’d better leave me a buck to cover my loss! Punk ass kid.” Apparently, he always knew exactly how many beers he had on hand. The thought shocked me back into reality. My father was dead. My mother was dead. Only I remained. I walked out of the kitchen and slumped down into my father’s favorite chair.

It was the only piece of surviving furniture from our previous home now present in this new one. It was the chair where he died. His lawyer golfing buddy had found him there when he didn’t make his tee time. The chair was worn, still holding the shape of my father’s torso, I turned on the lamp beside his chair. I sat there remembering many dark moments in a new light. My father carefully tended to the particulars of his life absent mother and absent me. He managed a life ordered by the mundane, and still found a way to enjoy golf on Saturdays, crosswords on Sundays, and by the care exhibited in the minutiae of his last moments deliver a key to his estranged prodigal son. My father’s intentionality made this strange home into a familiar space. My ambivalence suddenly and violently turned to grief. I wept for the first time in years.

A torrent of remorse opened up like a fire hose. “Daddy!” I screamed, “I hate you!" No. Daddy, I love you. Confused bellows of grief gave way to the clarity of love. This man wasn’t my father, distant, removed, and dead; he was my daddy, present and alive in this house, in my heart. Eventually, the tears relented, and I attempted to compose myself by reclining in the chair. As I reflected on the unreconciled years and the long journey, I had just made in only a few steps, it occurred to me that I had unintentionally followed the path of the numbers. The numbers randomly assigned to the rooms in that strange black Moleskine I found in the corner of the attic. Was it the power of suggestion, or had my father ordered my steps from the grave? When was that Moleskine placed there? Who placed it there? As I sat there staring at the lifeless television screen, I thought about what must have occupied my father’s thoughts in those last moments. He missed me.

I instinctively reached for the remote that I knew my father would predictably keep in the side of his chair. The remote was there, as was a sealed envelope to my surprise, a nondescript white envelope that simply

read in my father’s distinctive handwriting, “To my son.” The tears I sought to repress returned.

I composed myself long enough to open and read, “To my son, I hope it is you. For all the wrong, for all the lost time, I’m sorry. Your mother wanted you to have this. She loved you. -Love, Dad.”

Attached to his note by a single paperclip was a deposit slip from a decade earlier. It was from First Guaranty Bank for $20,000, my share of a life insurance policy my mother had left me.

I resolved to make better decisions; I was determined to reach out to my children and make the effort to heal the hurts. I closed the door behind me a richer man, and it had nothing to do with the money.

Mark Brown

That Untravelled World

Rain

i would like to sit outside in the rain let the drops of cloud slowly soak through my clothes be refreshed by the earth

i would like to wash away all of my woes baptized again by mother nature the cool patter of water on my face slows my heart rate and allows me to breathe again

the rustle of leaves soothes my mind and brings peace

i would like to sit outside in the rain

A New Seed Emerges

Stargazing

My sister and I snuck out of bed

To dance in the midnight air

We twirled until we were dizzy

And flopped on the grass

To look at the stars

That’s when I realized

That the stars like to look back

So I let them look at me

Just a little longer

We sat in his truck bed

In that open field

Claiming to be star gazing

But our eyes were closed

And our lips locked

And the stars gazed at us instead

Promising to keep our secret

And let us stay there

Just a little longer

I hold my little infant close

As she finally drifts to sleep

My constellations illuminate her face

With an angelic glow

And I let them kiss her with their light

I know I should put her in her crib

And try to get some rest

But the stars want to view her

Just a little longer

I have come into the night once more

To say goodbye to my old friends

It took some time to get here

For my bones are weak

And muscles sore

It is almost time to join them

My mind whispers to itself

But I want to gaze up at them

Just a little longer

I look at the blue and green globe

Admiring the beautiful creation

And the creatures in it

I see their lives

And hold their secrets

But the sun is slowly rising

And moon calmly eclipsing

But I remain to gaze down

Just a little longer

AClematis in Winter

One Samhain Night

Everything smells like magic, and magic smells like decaying grass, campfire smoke, and cinnamon. The wind blows the leaves around like tiny dancers pirouetting, twirling, and leaping to the tune of their swan song. There’s a manic fizzle to the air that keeps me right on the edge of contentment and despair. One false step, one wrong breath, and over I’ll go to be swept up or drug down, so I fling out my arms and step ever so lightly.

A fuzzy face rubs against my leg, and I reach down to stroke the aging salt and pepper fur. My gaze drifts from the window down to those brown eyes that sparkle even through those milky irises. My wise old friend, I often wonder what I have done that makes me so deserving of your love and endless patience. In my eyes, I fall short in every category, but you stick by my side always and without complaint. In my heart, I know the gods got it wrong. Dogs should be in charge, and we should be the pets. The world would be a much kinder place if Bo-dog were in charge.

Puck comes in and nudges my other hand. I laugh and tell him he’s right. I have two hands, so why would I not pet two goofy mutts? I’m sure it’s my age, but at moments like this, I look at their faces and think about how, of all the moments in my life, these are perfect and will never be regretted. This is time I spend wisely.

“Sami,” Andy’s voice calls from the kitchen, “how long do I stir this gravy?”

“Just keep going,” I say. “I’ll be there in a minute.” I rub their heads one more time and go back to lighting the candles. I’d spent an hour ironing the festively orange and black tablecloth this morning and did my best to arrange my decorative plastic pumpkins in my dollar store candy bowl to make the centerpiece. Every surface had been dusted and cleaned twice for good measure. I want everything to be just right. I want you to be proud of me.

After a final sweep of the room, I return to the kitchen to relieve my grateful husband and continue my preparations. Dinner needs to be on time. It can’t be late. You hate it when things run late.

It’s been a year since I’ve seen your face, heard your voice, or felt the comfort that comes from knowing you are here in the same room as

me. There’s a pep in my step as I call out to Andy to set the table. I’ve made all your favorite foods and a few extra treats that you’ll pretend you don’t like but you’ll eat them. You always do.

Bo is lying in the corner of the kitchen now, watching me cook contentedly. Poor dog has gotten a bit pudgy in his old age, but at nearly a hundred years old, I find it hard to deny him anything. I slip him a piece of meat, and he smiles at me with his goofy-semi-toothless grin. I pat his head and return to loading the serving dishes.

“It smells wonderful,” Andy says, wrapping his arms around me from behind. “He’ll love it.” The weight of his arms calms me, and I relax into him for the briefest moment before I break free, pass him a serving dish with mashed potatoes, and follow behind him, carrying a plate of roast beef in one hand and the gravy boat in the other.

The dining room is glowing with the candles and jack-o’-lanterns I’d lit before. Everything is perfect, or as close as that gets for me. I pour water into our three glasses and take my seat to the right of the head of the table.

Andy sits down beside me, and I start to feel the anxiety and worry that had plagued me on and off all day. I don’t know what I’ll do if you don’t show up. I’ve worked so hard, you have to come, don’t you?

“Sami, breathe,” Andy says and grabs my hand. “He’ll be here.” I inhale deeply and shake my head bravely, willing myself to trust in those words. Bo meanders in and takes his place on his bed so that he can watch the goings on, and Puck loyally lays down next to his friend.

I hear the bells first, those sweet, tingling notes that ring out every time the door is opened. The door creaks ever so slightly as it shuts. My heart is railing against my chest, beating against my skin, begging to break free, to fly. Each step is like a hundred years or the blink of an eye. Time seems to be disjointed, speeding up and crawling to a near stop at random.

You look just like I remember you, but your hair is all white now, and there are a few more wrinkles around your eyes, but you look happy. Some people smile with their teeth, some with their lips, and some with their eyes, but you… you always smile with your whole being. It’s an emotion that radiates with the warmth of the summer sun, and I let it wash over me. I know in an instant that whatever happens, I’ll be ok. I

suddenly remember to breathe, and all of that anxiety drains from me, evaporating in your comforting light.

“I have so much to tell you,” I say as you sit across from me, and Andy dishes you up a plate. “What do you think of the house? I know it’s a bit of a fixer-upper, but we’re working on it little by little. And look, did you see I’ve got great-grandpa’s buffet in just the right place? Bo isn’t looking too shabby for an old man, huh? The vet says he’s got a tumor, but I’m sure you know that…”

I ramble on and on, hardly letting Andy get a word in. I want to tell you, I need to tell you everything that’s been happening, everything that’s changed, and it’s nothing you don’t know, but it’s different because you’re here, because I’m here telling you now. Every small thing feels like the biggest news, and one story bleeds into the next endlessly as the meal progresses.

I’ve missed you so much. How has it been so long, and yet now, it’s like no time has passed. I push soul cakes onto your plate, and you shake your head at first, but you eat them. I knew you would. You love raisins.

I know you’re done eating when you slouch a little in your chair and put your hand on your stomach. You always do that when you’re full. There is comfort in every familiar movement, even as you push away from the table to look at Bo. He tries to stand so that he can come to you, but he falls over. That happens sometimes now; the arthritis has gotten pretty bad. I get up and run to help him, but you beat me there.

It makes me happy to see the two of you together again. I remember when I bought him for you. You didn’t know if you were ready for another dog, but we drove 3 hours one way just to look and see if there’d be the right friend for you there.

I can still see how green the fields were that foggy May afternoon. Kaitie is with us as we walk towards an old decaying barn. The air is wet and heavy with the scent of alfalfa and sheep. Hidden in the tall grass is a litter of black and white border collie puppies. They’re all excited to see us. Kaitie and I kneel down to play with all the little expectant faces, but you hang back a bit, watching instead of getting in the middle of the fray.

“What do you think?” I ask you, holding up one squirming puppy for you to see.

“I don’t know yet,” you say. That’s when one of the puppies leaves the others to sit in front of you to look up at you with the biggest puppy smile I’d ever seen. You reached down, picked him up, and said, “Hello there, Bo-dog.” And that was it.

I proudly paid the farmer for the dog. It was the first time in my life I’d been able to buy you something other than a cheap bobble, and it felt amazing like I was a real grown-up and not just playing make-believe.

I watch as you pet the old man’s head. He’s so happy to see you. I kneel too, and look at you. I can feel the rivers running down my eyes. “I knew you would come, Daddy. I knew you would,” I manage to choke out.

You look at me, but I can’t look back anymore. I close my eyes tight, and I feel your hand on my cheek. “It’s going to be okay, Sami-o,” your voice says. I try to hold on, but I know that you’re here to help me let go. What feels like a gust of wind rips through the room, and when I open my eyes again, the candles are all blown out, and you’re gone, you’re both gone.

Bo’s head is heavy and lifeless in my lap. Puck is whining and nosing his friend, begging him to wake up. I feel Andy walk past me to comfort our boy. I want to help, but I can’t just yet. My heart feels sharp, jagged, raw, like barbed wire in my chest.

The bells on the door jingle lightly, and I’m on my feet running after you. I have to stop you, you can’t go, you can’t leave me again. I rip open the door and run into the middle of the dark street.

I can see you walking away from me, “Daddy, please,” I manage to whisper. You turn back, and Bo runs up to me. He looks better than he has in years. I know he’s well again; he doesn’t hurt anymore, and I know I’m selfish.

“I was so worried when you left us,” I tell you. “I didn’t think Bo understood. I’m glad you came to get him. I’m glad he’s not alone. I love you both.”

You smile, and I feel Andy’s hand on my back. I reach down and grasp his free hand. I know I’m squeezing way too hard, but he doesn’t say a word. Bo is running back to you, and when he reaches you, you turn your back to me, and I watch as you disappear into the darkness.

It’s a night for love, it’s a night for pain, and it’s a night for ghosts. I hurt because I love, and that is an agony worth facing again and again. If

my heart weren’t broken, I would have experienced nothing worth remembering, I remind myself as I breathe in shakily.

“Come on, honey,” Andy says. “We need to pull up the welcome mat.” Welcome mats are tricky things. They’re an open invitation to whatever is out there, and there’s a lot that I wouldn’t welcome in my home. Ours comes out once a year, and it very specifically invites friends and family only. We’ve had our visitor, so it’s time to roll it up.

When Samhain comes around again, when the veil between worlds is at its thinnest, we’ll roll out our mat, and I’ll set you a plate and make your favorite foods. We’ll put out a bowl for Bo and invite you both back into our lives and our home. We’ll tell your stories, update you on everything happening here, introduce you to new family members, and enjoy your presence while we may. This is how I keep you alive. This is how I hold you in my heart when I can no longer reach out for your hand.

After the Ice

Separating Wheat from Chaff

Rudy picked up his axe and headed towards the barn. His Hereford cattle were waiting, watching him walk slowly through the deep snow.Arthur, his cat, who had followed him out of the house, walked carefully in his tracks. The sun was just coming up, turning the sky a watery blue. Rudy opened the barn door to let Arthur in and then let himself through the gate into the cow lot. He trudged through the deep snow, sliding on the ice where the snow had thawed and frozen again. He arrived at the round wooden water tank. It had a cover made out of foot wide boards, fitted together with tongue and groove construction. The boards ended about two feet from the edge, leaving a gap for the cows to drink. The cows couldn’t drink because the temperature overnight had been fifteen degrees below zero, and the exposed water had frozen into thick ice. Rudy swung his axe overhead and let it come down; as ice splinters flew he closed his eyes. He opened them and swung repeatedly, soon he had made a hole big enough so that the cows could see the water bubbling out and they started pushing each other trying to drink. Rudy moved out of their way and let himself back out of the gate.

Breathing hard, he leaned against the barn for a few moments, catching his breath and then moved on to the pump jack. It was a windless day, which was heartening with the cold temperatures, but it meant that he couldn’t use the windmill. He had straw piled around the well to keep it from freezing. He grabbed the cold pump handle and started pumping. Good, it hadn’t frozen, and water started spurting out of the end of the long spout that ran through the fence and into the water tank.

Rudy was used to hard work and responsibility; he was sixty-three years old. He had been living on this farm since he was born in 1912 in a sod house, to German immigrant parents. His parents had only lived in North Dakota for a few years before his birth. He was the first child born to them, and every two years another baby arrived until there were ten children. By the time the fourth baby had arrived, his father had built a new wood house. It wasn’t a big house, having two bedrooms with slanting ceilings on the second floor and a kitchen, a small parlor and a

bedroom on the first, but it seemed huge compared to the two-room sod house.

Rudy’s father died when Rudy was seventeen and running the farm became his duty. His siblings grew up, got married, and moved out. His mother moved in with her oldest daughter and then it was just Rudy living on the farm.

After filling the water tank, Rudy moved into the barn to feed his team of horses. The black Percherons munched the oats that he dumped into the feed boxes in their stalls. When they finished eating, he dragged down the harness that was hanging conveniently on a hook by their stalls. They stood quietly as he harnessed them. They were old horses and used to the routine.

“Hup King, hup June”, Rudy said, and they moved out of the barn and over to the hayrack, which was on sled runners for the winter.

“Back, back.”

The team backed up and Rudy soon had them hooked to the hayrack. They moved quietly over the snow, the team’s clumping hooves the only discernible sound. Rudy pulled his horses up next to a stack of hay. He jumped onto the stack and began forking hay into the rack until it was full. Then they went back to the lot where the cows were and Rudy pitched off the hay in piles, for the cows to eat, while the horses kept moving slowly forward. Rudy repeated this chore three times to feed the cows. Then he unhitched the team, put them back in their stalls, and pitched some hay from the haymow into the horses’mangers.

The year was 1975. Rudy’s outdated method of farming was a thing of the past, for everyone but Rudy. He had one tractor, a 1951 “H” International that he used to cut and stack his hay. His neighbors, including his brother Alvin who lived on a farm five miles away, all had big modern equipment and made their hay using swathers, or mowers and rakes, and big round balers.

Rudy finished his chores in the barn, by cleaning out the horse stalls and hauling the manure and straw out to the manure pile with a wheelbarrow. The sun was starting to go down, on another frigid February evening. The dying sun left streaks of brilliant pink and blue across the sky. Rudy was a man who appreciated nature and usually noticed such things. His remote farm had a large shelterbelt of trees that his father had planted and was home to abundant wildlife.

“ComeArthur,” Rudy said to the cat, who had been napping in the horses’manger and they returned to the house in the dying light. Coming into the kitchen, felt temporarily warm after the cold outside air. Rudy added coal to the big stove in the center of the kitchen, which was the only source of heat in the house. In one corner was a pump on a washstand that pumped water from the cistern under the house. The water wasn’t good for drinking, but at least he could wash his dishes and clothes with it. Not that Rudy washed clothes often. He wore the same set of overalls for a month, over the same faded red flannel shirt, long underwear, and thick wool socks.

It was Saturday bath night, so Rudy filled his metal tub by dipping the warm water out of the reservoir in the stove.After his bath he put on his second set of overalls, flannel shirt and underwear, and put his dirty clothes in the bath water to soak. While the clothes soaked, he added more coal to the stove and pulled his cast iron pan from the back of the stove. He dropped a piece of side pork in it and when the fat melted, started slicing potatoes into the pan. He butchered a pig every fall when it got cold enough to store the meat in the attic. He ate potatoes that were from his big summer garden, and pork at almost every meal. He bought some cans of vegetables and fruit to add a little variety to his sparse meals. When his pork ran out, he’d shoot a deer or a partridge. He never bothered to get a hunting license. He felt that God had put those animals on the earth for his use and there was no need to involve the government in it.

When his food had finished frying, Rudy scooped a generous helping onto a chipped plate forArthur, and dumped the rest onto a plate on the washstand. He stood eating his food, not really noticing the taste and then rinsed his plate in a metal washbasin into which he had added some warm water from the stove reservoir. He dipped a cup of cold water out of a bucket, and had a long drink. Before he went to bed, he’d make a final trip to the outhouse.

Although there was no running water in the house, he did have electricity. Rudy had it installed in the late fifties in both the house and the barn. He was glad that he didn’t have to clean the smoky chimneys of the kerosene lanterns anymore. Rudy walked into the parlor and pulled the string on the single bulb hanging in the center of the room and bright light glared suddenly into the almost bare room. He sat in the ladder

backed wooden chair and shook out the newspaper. For a break during his long day of choring, Rudy had walked across the slough to get his mail. In the summertime, it was a two-mile trip, but in the winter, he could cross the frozen slough, which shortened his walk by a mile.

Rudy thought back to when his farming career had begun. On a day like any other winter morning, ten-year-old Rudy was eating his breakfast, before leaving for school.

“Rudy,” his father said, “You’ve had enough schooling now, and you’re big enough to be a help to me. You stay home today, and we’ll clean the manure out of the lean-to.”

Rudy wanted to protest. He didn’t particularly like school, but he liked to read, and he knew what lay ahead of him at home. Just endless days of work. His parents believed hard work would get you to heaven just as fast as good works. But arguing with his German father was something that Rudy wouldn’t even consider doing. His mother didn’t say anything either, so from that day on Rudy stayed home when his sisters left for school. His sisters and brothers all graduated from the eighth grade in their country school, but Rudy’s formal education had ended that day.

Rudy had a subscription to the local newspaper because he liked to read the paper, but also because it was usually the only thing in his mailbox. He found it hard to walk the long distance for the mail to be greeted with an empty mailbox. When it was cold his face stung from the sharp wind, and the walk seemed even longer. If the weather was stormy the mailman wouldn’t come at all and save his paper for the next day. Still he appreciated the mailman, because he was often Rudy’s only contact with another human on a winter’s day. Rudy would time his walk to get to the mailbox at 10:00 a.m. about the time the mailman usually arrived. If Rudy couldn’t meet the mailman at the mailbox he would be sure to build up the fire in his stove so that the mailman would see the smoke coming out of the chimney and know that he was alive and well. Or at least still living. Rudy didn’t have a telephone and knew that the mailman would inform his brother if he thought something was wrong.

Rudy finished reading the paper and turned to the crossword puzzle. He had gotten good at doing the puzzle, except when the questions had to do with pop culture, or history. His sister-in-law Ella Jean had given him a crossword puzzle dictionary for Christmas one year, which helped him

out. Rudy didn’t own a TV, and though he had a radio he usually only put it on to hear the weather forecast, so most of what he knew of the world came from his newspaper.

“Well,Arthur, I think it’s time we hit the sack.” He stood up and tucked the newspaper with the completed puzzle into the stove. Rudy banked up the coal in the stove, turned out the lights, shucked off his clothes down to his long underwear, and crawled under the pile of wool quilts on his narrow bed.Arthur jumped up and settled against him and the day ended for Rudy.

The day might have ended but Rudy’s night had just begun. He woke up in the dark, judging it to be about 3:00 a.m. He rolled over and looked at the luminescent hands on his wind-up clock. Yup, 3:10. He never set the alarm on the clock, but relied on waking up when he needed to. Now he pulled his overalls and socks back on, went to the kitchen, took his coveralls off the hook where they hung near the stove, and shrugged into them. He slipped on his work boots and went out into the cold air.

Rudy’s cows were bred to calve in February, and he had a heifer that was due any day. He walked out to the barn, switched on the single light bulb, and peered into the pen. The heifer was standing in the middle of the dim pen twitching her tail.

“Ah, Bess,” he said “Is it tonight you’re finally going to have that calf?”All his cows had names, but he was the only one who knew that. When he was telling cow stories toAlvin he’d never use their names. But it helped him to refer to them by name in his mind, and he often did so out loud, when it was just he and the cows. His cows were used to his voice and it seemed to calm them when he talked to them in his soothing tone.

“Looks like it’ll be awhile.”

While Rudy waited for some feet to appear, he pitched manure into the wheelbarrow. Might as well be doing something while he was waiting, and the physical activity kept him warm.After an hour, a water bag appeared and then a half hour after that two feet protruded from the back of the young cow. “Bess, Bess, those look like some awfully big feet.”

The heifer was lying in the middle of the pen, thankfully not up against the wall. Rudy got his obstetrical chain from a hook, and carefully looped it around both feet. The hooves were the right side up,

which was a good sign. Upside down hooves meant a backward calf and one that had to be delivered quickly before it drowned in the amniotic fluid. Moving slowly Rudy got his calf puller, the one modern convenience that he was happy to own. He hooked the cable to the chain and started cranking on the handle every time the heifer pushed. It was slow going and Rudy was soon sweating inside his coveralls. Inch, by inch he cranked the calf out. The head popped out, but then the calf was stuck with its shoulders still inside the cow. He moved the puller around trying to work the calf free. The exhausted heifer was no longer pushing. Rudy kept on cranking the handle until at last the calf slid out. He switched the chains to the back feet of the calf and struggled to lift the calf up so that the fluids could drain out of its lungs. It was a big bull calf. He let the calf back down and dragged it around to the front of the cow.

“There you go, Bess. Get doing your job.” The cow sniffed at the calf feebly and finally started licking it. She would need to do a good job of licking the calf so that it would dry and its ears wouldn’t freeze and fall off.

“Let’s see if you can get up.” He dragged the calf out of reach of the cow and she staggered to her feet to follow. “Good girl,” he said.

Rudy picked up the chains and took them back to the house to clean them. He washed up and then crawled back into bed for a couple of hours before he’d get up again, to make sure that the new calf had nursed and then start the day’s chores.

When the snow had all melted and the ground warmed, Rudy did his spring planting at his usual slow pace using his small tractor and ancient drill. When he finally finished it was time to start haying. He sharpened his mower sickle on the foot powered grinding stone that his father had had, and went to cutting hay. Rudy made haystacks in the old-fashioned way; carefully building the hay into a tall stack that he hoped would shed water.

“Rudy you need to move out of the last century,”Alvin said, “but your haystacks are a work of art.”

After harvest was over it was time to sell his calves. Rudy never looked forward to calf selling time, even though it was his biggest source of income. He grew attached to the calves and found it hard to load them to take them to the sale barn.

Rudy already had the calves sorted from the cows and waiting in the barn to be loaded. The cows and calves were all bawling. It was deafening in the barn as Rudy guidedAlvin as he backed his trailer to the barn door, and they loaded the first load. “Want to ride along?”Alvin shouted.

“Nah,” said Rudy.

It would be a tough three days listening to the cows bawl for their missing calves, then they’d forget the calves had ever existed and things would be back to normal.

He kept his money in a coffee can in his washstand. With the money Rudy received from selling his wheat, and his calf check all of the cash wouldn’t fit into his coffee can anymore. Rudy crammed it into his tackle box. He didn't have any banking accounts, and he had never received a social security number.Aneighbor woman delivered him when he was born and no birth certificate existed.Alvin insisted that he had to apply for one, but Rudy preferred not to. The government had no business keeping track of him anyway. With no social security number, Rudy had never seen a need to pay taxes and the government hadn’t figured out yet that he wasn’t.

Deer hunting season opened and the usually quiet road was filled with traffic.Aclub cab pickup turned off the main road and drove down Rudy’s long driveway. There was a line of tall dried grass down the center of the road that scraped the bottom of the pickup. Rudy stood in the yard watching while they drove up. Rudy didn't like hunters. They were loud and intrusive and tended to leave a trail of spent shells, pop cans and chip bags behind them.

“Boy, isn’t he a relic,” one of the men said to his two companions before rolling down his window.

“Hi,” the man said, “I’m Bill Anderson from Minneapolis.Aguy down the road told me all this land back here belongs to you."

"Yep," said Rudy.

I want to buy it for hunting. My friends will be in on the deal and then we can come and hunt here every fall. This house would make a nice hunting cabin. We could put in some bunks and a heating system,” said Bill, looking around at the house. He noticed the metal tackle box on the washstand. “Is there good fishing around here too?”

Rudy said nothing.

“Sure there is,”Alvin finally answered. “There’s usually a bunch of campers set up over on Barnes Lake in the summer. There’s good fishing there, it’s just a few miles to the east.”

“We could bring the whole family and come up a couple times in the summertime too.”

“Rudy,Alvin said, “Just think what you could do with all that money. Even after you pay the taxes,” (Alvin carefully left out paying back taxes), “you’ll still have enough money to last the rest of your life. You’re sixty-three years old. You wouldn’t have to work anymore. You could get one of those retirement apartments in town.You could buy a TV, play cards with your neighbors. You’d never have to haul coal or pitch manure or thresh grain again. They even have ‘Meals on Wheels.’ You wouldn’t have to cook.”

“I don’t think I even remember how to play cards,” said Rudy.

“Rudy, at least think about it,” pleadedAlvin. “You’d be set for life.”

“Nah,” said Rudy, “I don’t think so.” The men left.

Rudy watched them drive away. He put on his coveralls. He buckled the flaps on his fur-lined cap and pulled on his chopper mitts.

“ComeArthur.” Rudy stepped outside into the glacial air and picked up his axe.

Butterflies

Have you ever thought of drawing butterflies?

Drawing them on your arms, your legs, your sides

Perhaps you should

I never once thought of butterflies

Never thought of what they could do

What they could be

But now I know

They are wonderful

I wanted to throw myself from a great height

I wanted to fly before I died

I wanted to hurt

But I never hurt enough along

Then I was told of butterflies

I was given a pen and told to draw butterflies all over myself

To draw them on my thighs, my waist, my arms

I hesitated

Afterall what is the point

Why would I care about some bug

But I did it

I took that pen and drew butterflies all over my body

Then I was told to name them

To name every butterfly after someone I cared for

To name them after friends, family, pets

It was silly and made no sense

But I already had the butterflies

So why not?

I named them

I wrote the names of friends

Of my family and my pets

I named every one of those butterflies after someone special

Then I was told why

Think of the butterflies as an extension of what they are named after

And if you hurt before they fade

You killed the butterfly

And not just one butterfly you killed them all

If you hurt they die

Draw butterflies

Please

Draw them all over your body

Use pen, marker, paint

Draw butterflies

Using all colors of the world on your skin

But don’t use silver

Don’t hurt

Because no matter what anyone ever says

No matter what you reflection thinks

You matter

Maybe not to them but you matter to someone

You may think that you don’t but you do

If not to your family then to your friends

If not to them then to your pets

You matter, no matter what you think

No matter what anyone ever says

You do matter

I’m begging

Don’t hurt

Don’t suffer

Don’t hate yourself

Don’t die

Please, draw a butterfly

Yellow Flower

WinterTrees