HEMPower|

Exploring hemp fibre composites in construction

Exploring hemp fibre composites in construction

The aim of this project was to understand how the crafting of sustainable materials like hemp can be advanced using digital technologies. In order to do so, the use and timeline of hemp fibres in construction is studied in contrast with the ways other types of fibres are used. The understanding from this tradition study is then utilised as a starting point to digitally model more efficient methods of using hemp. The need of the hour is for architecture to shift to a circular economy, using sustainable materials and move towards a symbiocene. In doing so, hemp would be one of the key building materials of the future. The study details out all information regarding hemp from source to construction and the learnings from the hands-on experience with the material.

Chapter 1: TIMELINE

- Artefact

- Introduction

- Reading the artefact

- Timeline summaries

- Synthesis and conclusions

- Close-ups

Chapter 2: MAPPING

- Adobe bricks with natural fibre reinforcements

- Fibre Reinforced Concrete with synthetic fibres

- Hempcrete

Chapter 3: WORKSHOP REPORT

- Aims

- Framing

- Mould Making

- Mixing and Tamping

- Drying

- Assembly

- Digital tools

- Issues with translation

- Scaling and Future Potential

Chapter 4: FUTURE SPECULATIONS

-HEMPower

Chapter 5: APPENDIX

- References

- Process images

- Joinery

- Workshops

- Manifesto

Mapping hemp in construction against other fibres

- ARTEFACT

- INTRODUCTION

- READING THE ARTEFACT

- TIMELINE SUMMARIES

- SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSION

- CLOSE-UPS

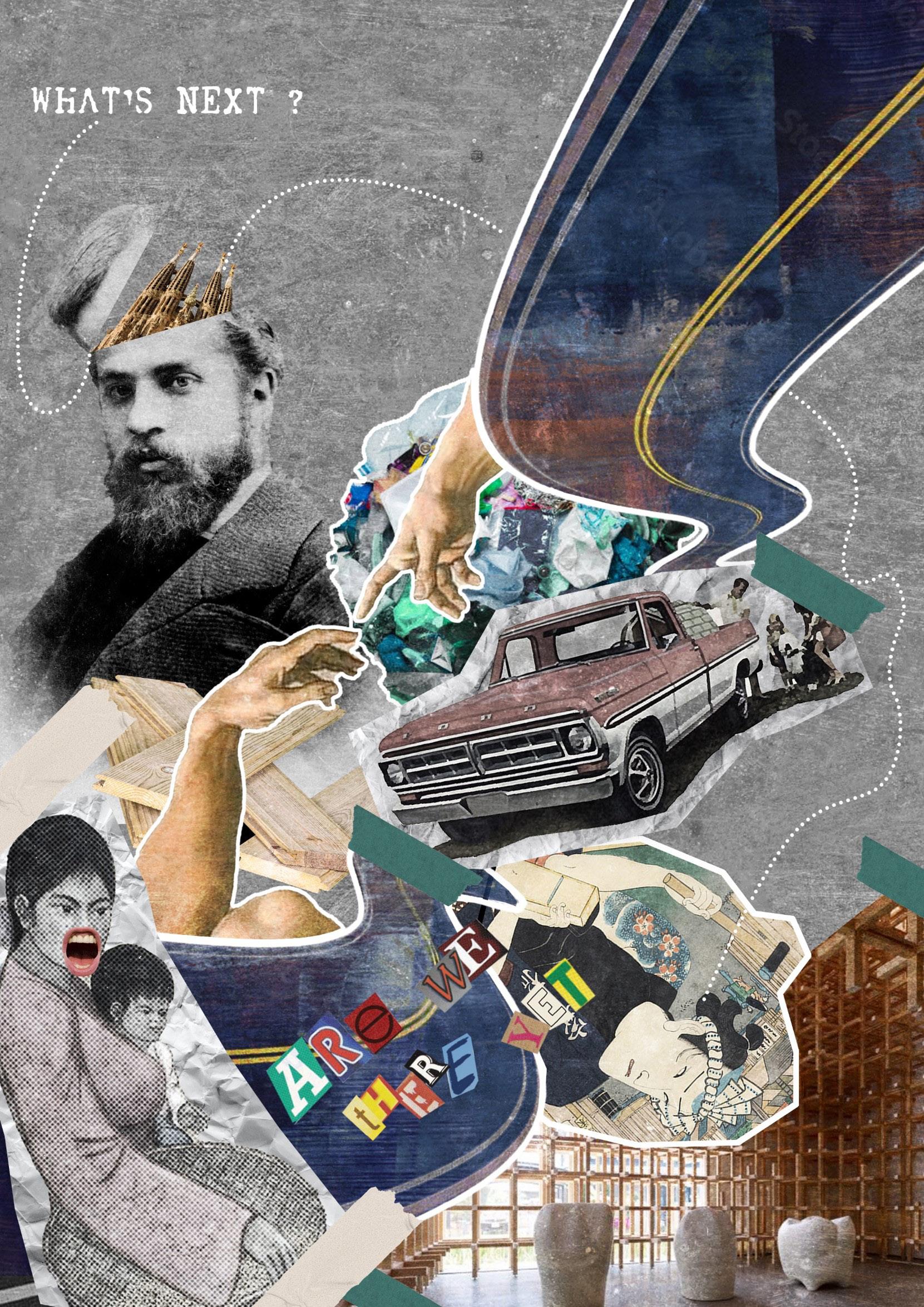

The artefact hung up in the studio is a representation of the timeline, mapping cases as well as the future speculation. It is not meant to be immediately legible but to be viewed as an artefact that invokes the same feeling of working with fibres hands-on. It is suspended in space with fibres’. In essence, it becomes what it depicts.

The central painted region along with the red threads represent the timeline of fibre , especially hemp useage in construction. It is created in such a fashion that a continuing timeline is represented by threads handing from the piece and any unknown areas of mapping have been removed and replaced with just threads flowing across. The symbols and knots which are sewn on top represent the points of interest along the timeline along with the writing in the centre.

The black threads overlaid on top represent the mapping scenarios happening through the timelinefibre as a reinforcement in adobe bricks, use of synthetic fibres in concrete and hempcrete use. The brown thread running along the side represents the density of use along different time intervals.

The threads that hang out of the timeline reach towards a hempcrete brick cast during the workshop. This in itself acts as the speculation for the future, illustrating the dominance of sustainable materials crafted through digital tools.

The timeline is hung up from the ceiling and it flows towards the hempcrete brick kept on the floor, the entire installation forms the artefact. The threads holding the timeline suspended act as extensions of the timeline itself.

The central point of the knot in each case lies on the timeline and represents the event. The concentric dashed rings around the knot represent the impact it had on other processes in the field. The whole mapping has been divided into 3 types of impact points: The smallest one representing events that are key happenings in the timeline but which did not affect any other timelines, the medium impact points which represent events that affected only related fields or activities and the large impact points which changed major aspects of the timline.

The green threads which are stitched in an organic form represent the events that had an impact on the climate and aspects of sustainablity. This can include invention of new materials that had drastically different carbon footprints or events that led to change in service consumption patterns like the industrial revolution. The length of the thread in each direction represnts the amount of time each of these events had an impact on new happenings along the field in the timeline.

Discovery of cotton and its initial use in Mexico, Peru and Pakistan areas in 3500 BC - cotton discovery opened up possibilities in a variety of different fields, creating a large imapct on the events that followed

Asbestos was banned in 17 countries in 2003 and this was an important step which pushed research into the use of synthetic and natural fibres as reinforcement in concrete instead of asbestos

The French used Hempcrete in 1980s to repair the old wattle and daub buildings since it had good thermal properties. This step pushed more people to re-look at hempcrete in construction and especially study the environmental benefits.

The discovery of the diseases associated with Asbestos mining was done fairly early compared to when it was banned later. This discovery created waves and research continued in this area for quite a long time until the hypothesis that it was carcinogenic was proven.

Along the timeline, there are circular or rectangular pieces of cloth with information stitched onto the article. The circular patches represent the technical advancements or details and the rectangular patches serve to provide definitions and information regarding the timeline.

Straw or thatch house detail as it was constructed in the historic times- the drawing shows the internal support structure as well as how it was covered with thatch.

The image shows the adobe bricks with natural fibres as a block. The arrowns around the block represent the idea that the earth was compressed to form the shape of the brick seen.

The legislative events that resulted in a world wide impact have been marked on to the timeline. They are both temporal and spatial since they represent which country is involved and to which extent.

The central dot expresses the event and the dots on each country’s location represents the percentage of countries from that continent that are involved in the legislature.

Hemp was legalised in many countires by the year 2019, the representation of this is shown on the timeline. Almost the whole of Europe, Asia and Australia had legalised hemp again.

Asbestos was banned in 17 countries and as seen, most of them were from Europe. America has still not banned asbestos even in the present day.

Asbestos was used since ancient times since it was one of the natural fibres which did not catch fire. Alexander used to make armours out of this material and many empires used to soak asbestos cloth in oil before bombing the enemy. Different cultures have also used asbestos to wrap dead bodies before cremation. But the use of asbestos was not extreme in the construction field until the Industrial Revolution. The movement pushed the use of asbestos and the insurgence of asbestos concrete happened. The mining of asbestos increased drastically and by the 2000s its use had peaked all around the world. But people were starting to notice the issue with the material that its mining had carcinogenic effects. Once the proof for the negative health effects of asbestos came out, many countires banned its useage thus its use gradually declines, although even to this day, it is not banned in US which was one of the largest consumers of asbestos during its peak.

Straw was used in ancient construction as it was easily available and was a good roofing and wall material. In fact in some cases, it was mixed with mud plaster for flooring as well. But the use of straw bales for structural purposes was discovered by the north americans during 1950s when they constructed a house from straw bales. In 2013, legislation was introduced regarding the use of straw bales. The straw bale code gave details on how to construct and the limitations to be kept in mind while constructing straw bale structures. In fact, this legislation also controlled the building using hemp to some extent since there was not official document for hemp construction. Currently straw is being seen as a very good alternative of additive in cement since it increases the mechanical strength in concrete. It depends on the cellulose level of the fibre but jute, barley and millet straws are being used in such mixes already and they have been holding up under pressure simulations.

Hemp was used in the making of ropes and ship sails before it was used in construction. Intitally in construction it was used in a similar way to other natural fibres as a reinforcement in adobe or earth works. But later in 6th century, the french used hemp lime in mortar to construct a stone bridge called Merovingian bridge. During this time, hemp was also being used in construction in Japan and china and other asian countries. In the UK, growing hemp was considered very beneficial and there were laws that 1/4 acre of every 60 acres of farmland will be cultivated with hemp. But once the legislation on hemp changed, and cannibis was made illegal in may countries, the hemp useage declined severely. After years of back and forth, hemp was legalised again in 1993 and after that its use was picked up again. The french used hemp to repair old timber structures because they had good thermal properties. UK was using hemp in commercial buildings and there was also progess in the method of construction, like, hemp clad panels used in the M&S store . The most recent 2022 Olympic sled and lug courses shelter also utilised hempcrete. It was also displayed among the 2023 biennale materials in London. In the future, there is all possibility that it could be used as a structural element and become a major part of construction.

The attempt to find synthetic fibres was done in 1664 but it only succeeded later with the discovery of nylon and rayon in the textile industry. Around this time, the Industrial Revolution was also happening and there was a push towards exploration in this area. As the use of asbestos declined and there was a need for a substitute, synthetic fibres were very quickly picked upon for this role. Thus fibre reinforced concrete was coined and it became a very important part of construction even until today. This is because the synthetic fibres were useful in dealing with the stress cracks in the compression zone of concrete. Initially carbon fibre was very popular along with plastics but after the war the buzz around carbon fibre declined but glass fibre was picked up in its place. The usage of glass fribes in construction keeps growing even today. Currently the research in the field is looking at hybrid fibre reinforcement which would help combat cracks at different setting conditions of concrete.

Once all the different timelines are meshed together, one can speculate on these ideas: The natural fibres have been in use since ancient times. Even hemp as a natural fibre was used by communities around the world since hundreds of years. But events like the industrial revolution accelerated the growth of materials like concrete and additives used in concrete like asbestos but led to decline in the use of other natural fibres. But once the issues with asbestos use were brought into the forefront, research was pushed to identify synthetic fibre alternatives to use as reinforcement in concrete. But once the ideas behind sustainability and green buildings were brought into the forefront, the focus was shifted to see if natural fibres can be as good a substitute as carbon or glass fibres in construction. This opened up opportunities for materials like hemp and hempcrete to be used in construction in mainstream buildings.

Another important factor in the timeline that affected hempcrete use was the legislation behind it. At one point, the hemp use declines to such a drastic extent because of cannibis being illegal in many countires. But its useage is picked up again after it was legalised in UK and other countires. The research on the environmental benefits of hemp accelerated the built prototypes in the field and in the current times, it is one of the trending materials in architectural research. The progression at this pace would lead to hempcrete becoming one of the main construction materials in the industry in the future along with other sustainable alternatives.

Process mapping for scenarios illustrated on the timeline

ADOBE BRICKS REINFORCED WITH NATURAL FIBRES

FIBRE REINFORCED CONCRETE WITH SYNTHETIC FIBRES

HEMPCRETE

Six earth samples collected from the Qingtai site in China in 2018 revealed the use of adobe bricks reinforced with plant fibres stacked with the use of adobe mortar with a coating material applied on the interior and exterior surfaces. The bricks were 48cm long, 28cm wide and around 15-20cm in thickness. They were dense and showed an uneven distribution of the fibres. (Wenjing Hu et al., 2022)

The most common method of construction in the present times with adobe blocks is to run a steel rebar as support from within the brick, continuing through the stack above. The rebar can be run through the block either by drilling a hole or by using half adobe bricks to form a space in the centre, later filled by adobe or cement mortar.

As shown by the graph, the addition of the fibres to the adobe bricks increases its performance in both compression and flexture. The amount of increase in the mechanical properties depends on the type of fibre used; as evident by the fact that banana fibres increase the strength by 65-75% whereas the hibiscus fibres only increase by around 20-15%. MOULDING

Concrete develops cracks because of the lack of toughness or shrinkage. Or sometimes when there are expansion cracks, the reinforcement inside is exposed to the outisde elements and it leads to the rusting of the reinfrcement. These cracks also reduce the stiffness and load bearing capacity of the concrete element. ( C.Zhou et al., 2023)

In order to counter this, there are additives added to the concrete mixture. One of the most commonly identified and used one is the addition of fibres in the concrete mix. There are different types of synthetic fibres used in construction like steel fibres, glass fibres, plastic fibres, etc.,and each of them behave slightly differently with the concrete. The most recent research in the field is on the use of hybrid fibres in concrete in order to counter effectively the cracking at all stages. The same is explored .

Steel fibres are the most studied additives for concrete and research on this material dates back to 1908. Of them, the profiled steel fibre and the coarse steel fibres are the most commonly used because of their superior performance enhancement. The studies of previous examples which have used steel fibres have shown that in terms of the fibre orientation, when the angle of steel fibres in the UHPC mesh is 20-45 degrees, the drawing performance is the best and this orientation of steel fibres can be controlled by adjusting the rheological parameters. (C.Zhou et al., 2023)

The macro fibres used in concrete may not have the most effective bonding with the material when looked at a smaller scale. The use of whiskers or nano-fibres eliminates this problem since it creates a rough surface at the micro-level which will bond better with the concrete and hence it improves the macroscopic fibre pull-out friction. This methof of using whiskers along with another fibre is explored best in the hybrid fibre applications of FRC.

Source: Whiskers action to increase the friction between larger macro-fibres and the substrate

C.Zhou et al., 2023

Hempcrete is made by mixing hemp hurds which are the by-products of the hemp plant with lime or a similar binder and water. It creates a mixture where the lime binder coats all the fibre pieces and once set creates a strong and durable material which is also fire resistant, insulating and carbon negative. The mapping follows the most typical method of hempcrete construction that is followed in the present day as well as shows the alternative available.

When mixed with lime, it is known as hempcrete but lime is not the only binder possible for hemp. The following table compares the properties of hemp when it is combined with different binders to make blocks.

Source: Hazri Mohd Ali, Oxford Brookes University

The hurd is the woody core of the hemp plant, and makes up about 60– 70% of the volume of the stalk, the other 30– 40% being the fiber content. Whether the hemp is being grown for fiber or for seed, the hurd is generally considered a byproduct. “The results from chemical analysis show that hemp hurds contain 44.0% alpha-cellulose, 25.0% hemicellulose, and 23.0% lignin as major components, along with 4.0% extractives (oil, proteins, amino acids, pectin) and 1.2% ash.

Source: Environmental impacts of hemp hurds C.Magwood, 2016

Lime has a long history of use in buildings around the world dating back several thousand years, most commonly as the binder in mortar and plaster. Although not nearly as popular a material as it once was (largely displaced by Portland cement), it is still available, and there are standards in place for most codes to cover its use in mortar and plaster. No standards or common specifications exist for the use of lime in hempcrete.

Source: Environmental impacts of lime binder C.Magwood, 2016

A wood frame of some sort is a key element in hempcrete wall systems. Wood framing is also the most common option for roof framing if hempcrete is being used as roof insulation.

Source: Environmental impacts of wood framing C.Magwood, 2016

The exterior of a hempcrete wall can be finished with a wide variety of siding. Each of these is applied to create a ventilated rain screen. This type of siding installation provides a great deal of resilience for a building by adding a durable and weatherresistant siding over an air space that both prevents water from reaching the wall core and provides an opportunity for drying if the wall core experiences high humidity or wetting. The lifespan of the siding is improved by the presence of the air space behind, and when the siding eventually needs replacing, the job does not affect the integrity of the wall core. Board or sheet-style siding comes in many forms, including vertical and horizontal varieties of wood siding, wood shingles, metal sheets and shingles, and composite planks and panels. All of these are fastened to the wall using vertical or vertical and horizontal wood strapping, with the vertical strapping creating the air channel between the face of the wall core and the back side of the siding.

- AIMS

- FRAMING

- MOULD MAKING

- MIXING AND TAMPING

- DRYING

- ASSEMBLY

- DIGITAL TOOLS

- ISSUES WITH TRANSLATION

- SCALING AND FUTURE POTENTIAL

Although the geometry of the mould worked perfectly well due to the application of digital tools like CNC machine, the minute gaps between the pieces of the mould caused water to leak out of the cast hempcrete bricks during drying, making them brittle and fragile. This issue could be because a circular CNC bit was used which creates an uneven edge while breaking off from the stock. The sanding of the pieces by hand might have created uneven angles, thereby causing gaps in the mould; later filled in by a sealant.

The first learning from the mixing process involved the shape of the container hempcrete was mixed in. An attempt was made to mix hempcrete in a longer container but it turned out to be uneven; the layers inside not being mixed well enough. The most ideal container to mix hempcrete would be on the ground directly or on a raft which is broader and gives enough surface area for effective mixing.

The first casting of hempcrete was done by compressing it by hand; the bricks were not compressed enough and ended up forming major cracks after drying.

Since the mould used for hempcrete at the farm was angled, a rectangluar tamper could only compress the upper layers but would hit the mould once someone tries to compress the lower layers. Hence it was necessary to make a tamper in the shape of an angled hexagon which can fit in easily with the angles of the mould and thus result in better compression. The use of the hydraulic press however applies more then necessary pressure, resulting in water loss from the mixture and poor compression overall.

The cast hempcrete bricks can be removed form their moulds in the span of 2-3 hours from casting but in order to dry on their own, it takes around 2-3 weeks. Two batches of hempcrete were tested where one was left to dry naturally for two weeks and the other batch was dried inside a kiln at 105 degree celcius for 12 hours. Although both bricks dried to the same degree, the boning to the lime was much better in the naturally dried brick whereas the brick from the kiln crumbled under pressure.

The strength of hempcrete comes from the setting and bonding of the lime used in the mixture to the hemp hurds, as the water slowly evaporates. The hastening of this process will result in quick drying of lime where it does not bind with the hemp fibres, thus creating fissures and ultimately resulting in the brick crumbling under slight force.

During the assembly of the kiln-dried hempcrete bricks, the group felt that a smaller size of hemp hurd used in the bricks would have resulted in more precise geometry of the bricks as well as a stronger brick. Since hempcrete is a light material, the interesting speculation here was to consider scaling up the brick to such an extent that the size of the hemp hurd is no longer an issue along the edge, thus resulting in fairly sharp geometric bricks made from hemp.

Although the bricks were assembled as per the 3D model, gaps were formed in the assembly because of the brittle quality of the kiln dried bricks and the lack of pressure applied for packing. This resulted in gaps between the brick and frame, which ultimately led to the collapse of the wall, even though a temporary fix was attempted by packing the gaps with crumbled hempcrete from the bricks.

A multitude of digital modelling methods and tools for the physical realisation of the models were used through the process of making the assembly at the wall. It resulted in a variety of moulds and frames modelled precisely to impart the strict geomtry of the topological interlocking solids to an organic and fibrous material like hempcrete.

The moulds used to cast the hempcrete were created by using CNC cutting. The major learning from the process happened when there was a power failure in the middle of CNC-ing the frame. The re-caliberated model was not completely aligned to the initial model and hence the resulting moulds were slightly uneven and needed to be sanded manually in order to fit together.

An alternative to using dowels to vary the depth of tetratehdon resting on the mould was to use acrylic triangluar sections offset form the cut edge of the tetrahedron at the plane of resting. A laser cutting machine worked best for making these elements since it was fast and extremely precise.

The tetrahedra used in the process of casting were modelled on Rhino and 3D printed with a PLA filament. Two types of tetrahedra were made- one which was hollow on the inside which broke with tamping pressure and kiln temperature and the other one with tubular supports inside which manifested on the outside as the holes for inserting the dowels; the second type of piece was much more sturdy and also withstood the temperature of the kiln during drying

Undercuts with CNC cutting:

The simplest solution for mould making was to create the entire piece as a single mould but due to the geometry having under-cuts, the CNC cutter was not able to mill the element as a whole. Hence the mould was broken down into two parts- a triangular mould with tetrahedron resting at the corners- thus pushing the dynamic aspect of the mould.

Issues with the circular drill bit of the CNC machine:

Since the CNC machine uses a circular drill bit, the cutting at the edge was not even and it also left a curved edge on the inside when the moulds were milled- especially visible in the plaster cast bricks which were used in a smaller scale model of the same assembly.

Pattern meshing with Grasshopper:

The use of the variable mould resulted in the creation of different sized bricks. It was speculated here that this difference in the size of the bricks could result in a very interesting pattern of bricks which can be used on the facade of the structure.

The problem with a random meshing tool on grasshopper was that it created inconsistent gaps between the brick pattern- without respecting the ideology behind the topological interlocking blocks, thus resulting in failure of the concept in reality.

Melting of the 3D printed tetrahedra:

Although 3D printing the tetrahedron saved time in the process of casting the hempcrete bricks, when they were put into the kiln during drying, they warped, melted and lost their shape, thus the following bricks made using the same tetrahedra had warped faces. Some of the pieces also broke under the tamping pressure.

With a precise excution of the frame and proper drying of the hempcrete bricks, there is a possibility that one can span longer bays using hempcrete bricks without internal supports required. It would also allow one to have openings and facade patterns as required, whilst being a load-bearing wall.

HEMPower EXPLORING THE STRUCTURAL PROSPECTS OF HEMP-BASED COMPOSITES

The study of the timeline artefact which maps the use of hemp fibres in construction in contrast to the other natural fibres reveals that Hemp is one of the natural fibres which has been in use since ancient times. Even just in the field of construction, for example, Hemp lime mortar was used by the French way back in 6th century AD to hold the stone masonry of the abutments of Merovingian bridge and also during the Roman era since it helped to reinforce the mortar ( refer timeline p1011, refer mapping p48, Building with hempcrete: Build Environmentally, Arch20) In the form of Hempcrete however, its use can be traced back to 1980s in France where it was used to improve the thermal performance in the old timber-framed wattle and daub buildings which were deteriorating (refer timeline pg10-11) Essentially, hempcrete is a composite of a bio-fibre- hemp hurds or hemp shiv with a mineral binder like lime, mixed with water in such a way that the lime binder coats all the fibres of the hemp (Magwood, 2016 p3)

This paper HEMPower’ is written in conjunction with the manifesto Constructing Symbiocene: Materiality of Coexistence’ following a period of hands-on experimentation with hempcrete at Grymdyke Farm, Princes Risborough (refer p80-81 for manifesto) as a speculation of the future use of hempcrete in construction. The manifesto refers to the creation of a circular economy, a system where the lifecycle of products is extended through sharing, reusing and recycling materials (Circular economy: definition, importance and benefits, European Parliament), to push the idea of the Symbiocene ( Albrecht, 2016: p13). Hemp hurds used to prepare Hempcrete are considered agricultural by-products of the Hemp crop which has comparatively large yields all around the world and hence, promoting the use of hempcrete would utilise the large amounts of waste generated during large scale production of hemp (Magwood, 2016 p7)

“Plant-based biomaterial, hempcrete is a lightweight material with high density that can be grown in fewer site areas with low requirements of pesticides. It is fire resistant, robust, works as a CO2 sink, can be recyclable, has a high capacity for energy-efficient use, is non-toxic, and lacks protein content which makes it resistant to insects hence, hempcrete is both environmentally friendly and construction friendly building material ” Yadav.M ,Saini.A., 2022, p2028

The life cycle analysis of a building made of Hempcrete in New Zealand in 2014 was used as data by Hana Bedliva and Nigel Isaacs (2014, p86) to show that the material is less energy intensive and has negative greenhouse gas emissions. These properties of hempcrete, tested and documented, put it at the forefront in a discussion of circular economy. It was even one of the materials in focus at the London Design Biennale 2023 (2023, Parametric Architecture) Although one can understand by the timeline that Hemp production decreased with the laws against cannabis, by 2019 most of the countries had again legalised hemp production for construction and accelerated by the sustainable building materials research, hempcrete is now one of the major natural fibre composites contested for environmentally responsible construction.

Although the material has many desirable properties, Hempcrete has a very poor mechanical performance and hence cannot be used as a load-bearing element in any construction ( M.Yadav, A.Saini., 2022, p2027) The most commonly used method of construction involves a stud framing in timber within the hempcrete walls, a method effective for fairly simple geometric structures. (Magwood, 2016 p39) The use of interlocking blocks instead of panels not only reduces the thermal performance but it also requires the use of a supporting structure running within. JustBioFibre Structural Solutions created an interlocking precast hempcrete block with an integrated biocomposite structural frame within; the closest attempt at creating an interlocking mechanism for hempcrete structures that can withstand loads (2018).

Referring back to the manifesto, this paper argues that 3D geometric modelling of hempcrete blocks can yield the structural strength lacking in the material whilst still respecting the traditional processes of casting hempcrete, thus enabling the use of hempcrete for more complex structures and facade patterns.

The exploration at the Grymsdyke farm was based on the properties of Topological Interlocking Solids- A system derived from Abeille’s ‘Voûte plate’ drawings of a flat vault in 1699, where platonic solids like the tetrahedron, cubes, octahedra, etc ( Dyskin et al., 2001) tessellate with the possibility of forming a hexagonal intersection at the midplane of truncation, thus pushing against each other and preventing movement in the vertical axis, as long as they are held together by tensional edge constraints ( F.Lecci, C.Mazzoli, et al., 2020, p7 ). Since it is difficult to achieve minute details in the casting of hempcrete blocks, the method of interlocking between two blocks was based on the geometry and the friction rather than complex joinery. An attempt made at the workshop to cut and saw a cast hempcrete block proved it to be a difficult task with little precision guaranteed. Hence, the speculation was made that interlocking blocks of hempcrete which hold against each other due to geometry could be achieved by retaining the traditional craft of casting hempcrete in moulds and tamping it when the mould or formwork itself was modified and optimised to create the complex geometries. Thus crafting the mould digitally would allow for a variable formwork within which a variety of hempcrete block sizes could be cast- opening up the possibilities for facade design variations depending on the meshing patterns of the blocks within a given frame.

Grimshaw architects along with University of East London’s Master of Architecture and Sustainability Research Institute (SRI) developed the first Sugarcrete-Sugarcrete slab using bagasse or sugarcane fibres, in a process very similar to the casting of hempcrete. The experiment resulted in a 5 blocks x 5 blocks slab structure made of Sugarcrete and held together by post tensioned wires at the periphery without any mortar which could easily hold the weight of 8 people on it. The Sugarcrete slab provides proof of the theoretical concept explored with the topological interlocking solids. It also expands the scope of exploration with different shaped moulds, more complex geometries and patterned variations in interlocking hempcrete block panels.

But the idea of using the topological interlocking solids is only one of the ways of exploring how to impart the structural strength to hempcrete. The most recent experimentation in the field has been done by BC Architects and Studies- where they constructed a self-bearing hempcrete vault prototype by layering hemplime of different mixes and densities to increase the compressive strength of the material. The mould was successfully removed on 29th November in 2023, validating the idea behind the project and creating scope for further speculation based on the composition of hempcrete mixes. The compilation of the research and experimentation in the field of hempcrete allows one to realise the argument put forth by this essay- that the future of building with the material would involve the construction of high-rise structures as well as complex organic forms, with applications ranging from the creation of patterned facades which control the microclimate conditions of the building to shells of hempcrete which can withstand the external loads without any internal supports.

Both the above mentioned methods of constructing with hempcrete have their own advantages and disadvantages. With the use of the Topological interlocking geometries, the hempcrete mixture can be kept consistent in terms of its composition and multiple blocks can be cast in a small amount of time with a larger number of moulds and a bigger batch of hempcrete mix. It is also possible to mesh and fit the geometry onto a curved wall surface (O. Tessmann, 2012, p203) which implies that more complex organic forms should be possible with hempcrete. It also allows for the creation of ventilation gaps and facade patterns depending on how the platonic solids forming the tessellations are truncated. But it affects the thermal properties of the panel since it may create thermal bridges and the geometry can lower the bending stiffness of the overall panel/ structure since it is broken down into smaller structural elements (F.Lecci et al., 2020, p8). The hempcrete shell structure with the different composition mixes works well in insulation and in load-bearing scenarios but it poses the issue of consistency which is especially harder to achieve with hempcrete. Depending on the tamping and the drying times in between layers, there might arise issues of bonding between layers and cracks within the shell structure.

The strength of a body made of a fragile material is inversely proportional to its size (F.Lecci et al., 2020, p8) and any cracks in a solid hempcrete shell would lead to a total failure of the structure. And both methods have issues with the consistency of tamping pressure and drying times for the cast hempcrete.

By virtue of the case studies and tacit experimentations described above, one can gauge the direction of development in the field of hempcrete construction. An interesting consideration here would be the fusion of the different technological ideas which have been applied in the construction of self-bearing hempcrete structures. Digital technology of the future would allow us to determine the exact proportions of hemp, lime and water in a batch of hempcrete mix. This information could then be extended and used to create a constant set of densities and composition mixes which would always produce the desired kind of block after drying. In fact, to arrive at which ratio of the three constituents works best, one can run a simulation test on a 3D model of the sample created with the traditional technologies and then change the input parameters to achieve the most effective mix. The parameters for such a model could be input after testing samples on different loadtesting machinery. The digital tools may also allow for a quicker drying process of the hempcrete- an attempt was made at the farm to dry the blocks in a kiln which resulted in faster drying but brittle hempcrete blocks- extending such a test would allow the discovery of optimum temperature and drying times for the various hempcrete mixes. We should then be able to tessellate the blocks from the highest to lowest density, thus optimising the strength of each individual panel and saving on materials in the process. Such a method would arise in the future which combines the experiments of both the topological intersecting geometries and varying the layer compositions. Hempcrete has already been proven to be a good material for insulation and panelling, and thus in the future, the focus would be on integrating it as a load-bearing member as well.

Since hemp can be grown in any climate, is easily available in large quantities and is associated with multiple sustainable features, many countries would implement hempcrete constructions if it was more efficient and organised.

“In the variety of buildings that we have had the opportunity to build with rammed earth in the area of Los Cabos, this bond exists between human and construction; however, the bond that is created when applying the hempcrete is undoubtedly much closer owed to the fact that it gets done almost entirely without any auxiliary tools to apply it beside your hands.”

A10 studio, Hempcrete workshop by BC Architects, 2019

Applying and tamping hempcrete is a very tacit process where one is connected to both the material and the years of craft associated with the construction. Going into the future, digital technology will be able to impart precision and efficiency to such a process without necessarily disposing of the traditional methods. It will be able to optimise the mould geometry, the composition mix and give information regarding the tamping pressure and drying times but would leave the space for one to carry out the process of casting similar to how it has been done for hundreds of years.

1. Walker,R.,Pavia,S.,andMitchell,R,(2014)‘Mechanicalpropertiesanddurabilityofhemp-limeconcretes’,ConstructionandBuildingMaterials,61,pp340-348.

2. Lupu, M. et. Al (2022) ‘Hempcrete - modern solutions for green buildings’, Materials Science and Engineering, 1242, pp 1-8.

3. Yadav, M. and Saini, A. (2022) ‘Opportunities & challenges of hempcrete as a building material for construction: An overview’, Materials Today: Proceedings, 65

4. Walker, R., Pavia, S. and Mitchell, R. (2014). Mechanical properties and durability of hemp-lime concretes. Construction and Building Materials, [online] 61, pp.340–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.02.065.

5. www.greenspec.co.uk. (n.d.). Hemcrete @ M&S Cheshire Oaks. [online] Available at: https://www.greenspec.co.uk/building-design/hemcrete-atms-cheshire-oaks/.

6. Lupu, Marius Lucian & Isopescu, Dorina & Baciu, Ioana-Roxana & Maxineasa, Sebastian & Pruna, L & Gheorghiu, R. (2022). Hempcrete - modern solutions for green buildings. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 1242. 012021. 10.1088/1757-899X/1242/1/012021.

7. Neubauer, L.W. (1955). Adobe construction methods: using adobe brick or rammed earth (monolithic construction) for homes. [online] The Open Library. Berkeley]: University of California, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station and Extension Service. Available at: https:// openlibrary.org/books/OL25397543M/Adobe_construction_methods [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

8. Yadav, M. and Saini, A. (2022). Opportunities & challenges of hempcrete as a building material for construction: An overview. Materials Today: Proceedings, 65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.05.576.

9. www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Amazing Lego-Style HEMP BLOCKS Make Building a House Quick, Easy & Sustainable. [online] Available at: https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=eqLXXjvQXgI.

10. Hu, W., Liu, X., Fang, S., Chen, X., Gu, W., & Wei, Q. (2022). Research on the building materials of adobe house in the Neolithic period at the Qingtai site, China. Archaeometry, 64(6), 1411–1425.

11. Ramakrishnan, S., Loganayagan, S., Kowshika, G., Ramprakash, C. and Aruneshwaran, M. (2021). Adobe blocks reinforced with natural fibres: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings, 45, pp.6493–6499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.377.

12. www.abebooks.co.uk. (n.d.). Adobe Construction Methods: Using Adobe Brick or Rammed Earth (monolithic Construction) for Homes; M19: 9781014322234 - AbeBooks. [online] Available at: https://www.abebooks.co.uk/9781014322234/Adobe-Construction-Methods-UsingBrick-1014322235/plp [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

13. Zhao, C., Wang, Z., Zhu, Z., Guo, Q., Wu, X. and Zhao, R. (2023). Research on different types of fiber reinforced concrete in recent years: An overview. Construction and Building Materials, 365, p.130075. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.130075.

14. Ischenko, A. and Borisova, A. (2020). Application of fiber-reinforced concrete in high-rise construction. E3S Web of Conferences, 164, p.02005. doi:https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016402005.

15. Mark, Evernden & Mottram, James. (2012). A case for houses in the UK to be constructed of fibre reinforced polymer components. Proceedings of the ICE - Construction Materials. 165. 10.1680/coma.2012.165.1.3.

16. Magwood, C. (2016) Essential hempcrete construction the complete step-by-step guide. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society (Sustainable building essentials). Available at: INSERT-MISSING-URL (Accessed: December 18, 2023).

17. enviBUILD (Conference) (9th 2014 Brno, Czech Republic) (2014) Envibuild 2014 : selected, peer reviewed papers from the 9th international envibuild 2014 conference, september 18-19, 2014, brno, czech republic. Edited by Kalousek Miloš and Čekon Miroslav. Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications (Advanced materials research, volume 1041). Available at: INSERT-MISSING-URL (Accessed: December 18, 2023).

18. McLean, W. and Silver, P. (2021) Environmental design sourcebook innovative ideas for a sustainable built environment. London: RIBA Publishing. doi: 10.4324/9781003189046.

19. Tessmann, Oliver. (2012). Topological interlocking assemblies. Digital Physicality: Proceedings of ECAADe 2012. 211-219.

20. Dogan, R. (2023). A closer look at the London Design Biennale 2023. [online] Parametric Architecture. Available at: https://parametric-architecture. com/a-closer-look-at-the-london-design-biennale-2023/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

21. Center for Humans and Nature. (2016). Exiting the Anthropocene and Entering the Symbiocene. [online] Available at: https://humansandnature. org/exiting-the-anthropocene-and-entering-the-symbiocene/.

22. Anon, (n.d.). Symbiocene – PLP Labs. [online] Available at: https://plplabs.com/symbiocene/.

23. European Parliament (2015). Circular economy: definition, importance and benefits News European Parliament. [online] www.europarl.europa. eu. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/economy/20151201STO05603/circular-economy-definition-importance-andbenefits#:~:text=The%20circular%20economy%20is%20a.

24. bc-as.org. (n.d.). Studies bc-as. [online] Available at: https://bc-as.org/studies [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

25. Zuo, J. (n.d.). HEMP IN CONSTRUCTION --A new sustainable natural building material. [online] Available at: https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/ object/uuid:a10845b1-594f-4e1a-b7c1-1be659ccc88e/datastream/OBJ4/download.

26. Anon, (n.d.). Building with Hempcrete – a10studio. [online] Available at: https://www.a10studio.net/building-hempcrete/.

27. T, M. (2023). Unearthing the Ancient Wonders of Hemp in Construction. [online] Big Chief Hemp. Available at: https://www.bigchiefhemp.co.uk/ unearthing-the-ancient-wonders-of-hemp-in-construction/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

28. Dezeen. (2023). Nine buildings constructed using hemp that show the biomaterial’s potential. [online] Available at: https://www.dezeen. com/2023/01/06/hemp-hempcrete-buildings-architecture/.

29. Anon, (n.d.). Product Specifications | Just BioFiber. [online] Available at: https://justbiofiber.com/products/product_specifications/.

30. Lecci, F., Mazzoli, C., Bartolomei, C. and Gulli, R. (2020). Design of Flat Vaults with Topological Interlocking Solids. Nexus Network Journal. doi:https:// doi.org/10.1007/s00004-020-00541-w.

31. University of East London. (n.d.). Sugarcrete. [online] Available at: https://uel.ac.uk/sugarcrete.

32. Peacock, A. (2023). Grimshaw and UEL develop sugarcane-waste construction blocks. [online] Dezeen. Available at: https://www.dezeen. com/2023/05/04/sugarcrete-slab-university-of-east-london-grimshaw-sugarcane-biowaste/.

33. grimshaw.global. (n.d.). StackPath. [online] Available at: https://grimshaw.global/news/articles/sugarcrete-revealed/.

34. rapidtransition.org. (n.d.). A fast plant for rapid shifts in construction – how the ancient supercrop Hemp can help build low carbon homes. [online] Available at: https://rapidtransition.org/stories/a-fast-plant-for-rapid-shifts-in-construction-how-the-ancient-supercrop-hemp-can-helpbuild-low-carbon-homes/#:~:text=Hempcrete%20was%20first%20developed%20in.

35. ArchDaily. (2020). Hemp Concrete: From Roman Bridges to a Possible Material of the Future. [online] Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/944429/hemp-concrete-from-roman-bridges-to-a-possible-material-of-the-future.

36. Kavanagh, S.-J. (n.d.). Hemp Concrete: The Past, Present and Future of Construction. [online] BDAA. Available at: https://bdaa.com.au/hempconcrete-the-past-present-and-future-of-construction/.

37. Doha2O (2021). Building with Hempcrete: Build Environmentally-Arch2O.com. [online] Available at: https://www.arch2o.com/building-withhempcrete-build-environmentally-arch2o/.

38. www.linkedin.com. (n.d.). History of Reinforced Concrete and Types of Reinforced Concrete. [online] Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/ pulse/history-reinforced-concrete-types-renovation-interior/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

39. www.constructionext.com. (n.d.). History of Fibers in Construction Materials. [online] Available at: https://www.constructionext.com/concretemasonry/history-of-fibers-in-construction-materials [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

40. Concrete Technology Weblog. (2008). Historic development of Fibre Reinforced Concrete. [online] Available at: https://caementitium.wordpress. com/2008/01/24/historic-development-of-fibre-reinforced-concrete/.

41. www.technicaltextile.net (n.d.). History of fibre development - Free Textile Industry Articles - Fibre2fashion.com. [online] www.technicaltextile. net. Available at: https://www.technicaltextile.net/articles/history-of-fibre-development-2442.

42. Anon, (2021). Fibres For Construction Materials | Fibre Manufacturers. [online] Available at: https://goonveanfibres.com/news-insights/news/ how-fibres-can-improve-the-construction-process/#:~:text=Natural%20fibres%20used%20in%20construction [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

43. Majid Ali (2012). Natural fibres as construction materials. Journal of Civil Engineering and Construction Technology, 3(3). doi:https://doi. org/10.5897/jcect11.100.

44. President, P.S.V., Consultant, G.A.V.B. and Advisory, G. (n.d.). Global Research and Analytics Firm. [online] www.aranca.com. Available at: https:// www.aranca.com/knowledge-library/articles/business-research/carbon-fiber-as-construction-material.

45. Akter, Elma & Shoag, Md. (2021). Study of fibers application in construction materials.

46. Construction, B. (2023). Flax: A fibre of the future for construction? [online] Bouygues Construction’s blog. Available at: https://www.bouyguesconstruction.com/blog/en/lin-fibre-construction/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

47. vicky (2019). Fiber as a Construction Material and its Types. [online] Civil Engineering Notes. Available at: https://civilengineeringnotes.com/fiberconstruction-material/.

48. King, D. (2013). The History of Asbestos - Importing, Exporting & Worldwide Use. [online] Mesothelioma Center - Vital Services for Cancer Patients & Families. Available at: https://www.asbestos.com/asbestos/history/.

49. Utilities One. (n.d.). The Future of Fiber Construction in Architecture and Design. [online] Available at: https://utilitiesone.com/the-future-of-fiberconstruction-in-architecture-and-design.

50. Labib, W.A. (2022). Plant-based fibres in cement composites: A conceptual framework. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics, 17, p.155892502210789. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/15589250221078922.

51. www.designingbuildings.co.uk. (n.d.). Carbon fibre. [online] Available at: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Carbon_ fibre#:~:text=Historical%20Timeline%20of%20Carbon%20fibres [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

52. Polser (n.d.). Fiberglass and its Use in Construction. [online] polser.com. Available at: https://polser.com/en/frp/fiberglass-and-its-use-inconstruction.

53. Hummingbird Bike Ltd. (n.d.). The Rich History of Flax Plant Manufacturing. [online] Available at: https://hummingbirdbike.com/blogs/magazine/ history-of-flax-plant-manufacturing [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

54. Baley, C., Bourmaud, A. and Davies, P. (2021). Eighty years of composites reinforced by flax fibres: A historical review. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, [online] 144, p.106333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2021.106333.

55. Creative Dundee. (n.d.). Flax. [online] Available at: https://creativedundee.com/flax/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

56. Yorktown, M.A.P.O.B. 210 and Us, V. 23690 P. 757-898-3400 C. (n.d.). Flax Production in the Seventeenth Century - Historic Jamestowne Part of Colonial National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service). [online] www.nps.gov. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/ flax-production-in-the-seventeenth-century.htm.

57. Ali Brown Weaving. (n.d.). The history of flax. [online] Available at: https://www.alibrown.nz/the-history-of-flax/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

58. Brzyski, P., Barnat-Hunek, D., Suchorab, Z. and Łagód, G. (2017). Composite Materials Based on Hemp and Flax for Low-Energy Buildings. Materials, 10(5), p.510. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10050510.

59. Fabrique (n.d.). Where past meets the future: Flax and hemp to accelerate toward our circular city. [online] AMS. Available at: https://www.amsinstitute.org/news/flax-and-hemp-to-accelerate-toward-our-future-circular-city/.

60. Wright, F. (2022). The short straw: bio-based construction. [online] Architectural Review. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/ the-short-straw?gclid=CjwKCAiAg9urBhB_EiwAgw88mUFvtFCNSXcaPNpKJuV_EUCnMhDGDSNbfTUFR05oWfCMw3Qxuq9KmxoCf0UQAvD_BwE [Accessed 18 Dec. 2023].

61. Wilson, A. (1995). Straw: The Next Great Building Material? [online] BuildingGreen. Available at: https://www.buildinggreen.com/feature/strawnext-great-building-material.

62. Ltd, N.M.P. (n.d.). Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete An Overview. [online] www.nbmcw.com. Available at: https://www.nbmcw.com/ product-technology/construction-chemicals-waterproofing/concrete-admixtures/pfrc.html.

63. Goonvean Fibres. (2021). Fibres For Construction Materials | Fibre Manufacturers. [online] Available at: https://goonveanfibres.com/news-insights/ news/how-fibres-can-improve-the-construction-process/.

64. Bendahane, K., Belkheir, M., Mokaddem, A., Doumi, B. and Boutaous, A. (2023). Date and doum palm natural fibers as renewable resource for improving interface damage of cement composites materials. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 12(1). doi:https://doi. org/10.1186/s43088-023-00374-9.

Information from the digital miro board with all the research was converted into written panels which could be arranged into a timeline, revealing connections and any missing data in the initial research

Exploration of the graphical representation of the information collected for the timeline- creating symbols for representing each element represented in the first timeline artefact | Graphic prototype of the artefact

In relation to learning about bamboo joinery, Ricardo Rosa presented his PHd Research project and machine which was used to cut bamboo into precise fishmouth joints- reducing manual effort and increasing precision. One could understand the importance of the iterative process and tacit learning when working with material like bamboo- which is difficult to manipulate digitally because of the inconsistency in the size availability and strength.

Images collected form the visit to Ercol Furniture factory in Princes Risborough to see the process of making wood furniture from source to finished product:

1- View of factory with wood sourced from around the world | 2- CNC machines for cutting parts of chair and other furniture | 3- Cut pieces of wood which are stacked for assembly | 4- Steam bending of wood woth machines | 5- Wood-working station at the workshop area | 6- Drying areas | 7- Machine for easy jig assembly 8- Detail of stool with anthropology and comfort in mind

Entering into the Symbiocene, the waste generated in nature is not dormant, it nurtures architecture and architectural material libraries. The material both begins and ends with nature and remains in harmony in-between. Architecture need not be exclusive; waste from other industries can feed material in architecture and upon decomposition such matter can nurture the surrounding.

Both craft and the material can be sustainable only when they are locally rooted

Architecture should mainly depend on material that is abundant in its context, to the craft and culture surrounding it. The realization of sumbiotecture would critically depend on reducing the inbound and outbound transfer of material from its context and in increasing the dependency on local craft, and its techniques passed on by experienced ancestors.

Any newly introduced atypical material would depend on typical crafting methodologies adapted to its material properties to create novel joinery techniques. Past craft feeds and evolves into the future design.

Choice of the material will dictate the design process, the detail can be inspired but will always be manipulated by the properties of material chosen. It is avant-garde but also in harmony with the natural precedent.

All design is inspired by and is in tandem with nature but it can never possibly emulate it to the last minute detail. This is true even with reference to a precedent building or detail. Even in sumbiotecture, architecture is seen in collaboration with nature but never as a replacement to the natural.